Michael May's Blog, page 159

July 30, 2014

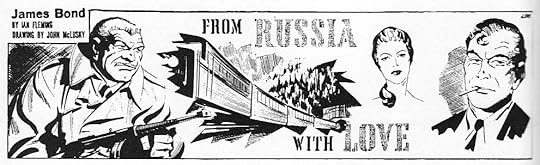

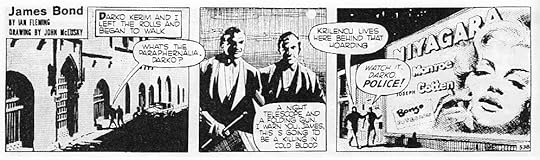

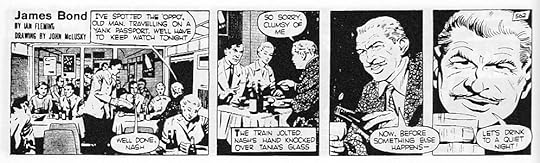

"From Russia with Love": The Comic Strip

It would be heresy (and not even true) to say that the comic strip version of From Russia with Love is better than Fleming's novel, but it does fix the problems I had with the first half of the book. Scenes of the Soviets planning Bond's fall are intercut with scenes of Bond in London that Fleming alludes to in the novel, but never shows. The strip also shows Kerim's initial meeting with Tatiana as it happens in relation to other events instead of Bond's only hearing about it later. This all front loads the story with more action than the novel has and works really well.

In fact, the whole adaptation is one of the best in the comic strip series so far. My only nitpicks are a couple of character designs: Red Grant looks old and out of shape and Kerim Bey distractingly resembles Clark Gable. Oh yeah, and Kronsteen is accidentally referred to as Klonsteen a couple of times. But if any of Fleming's novels could use a faster paced, slimmed down adaptation, it's From Russia with Love. The strip focuses the right amount of attention on the good parts while breezing through the dull ones.

There's of course not nearly as much tension in Bond's being stabbed with a poison shoe-knife at the end, because newspaper readers only had to wait until the next day for the resolution instead of the whole year that book readers endured. That can't be helped though and Bond's falling unconscious after being stabbed is a perfectly good if not unusual cliffhanger for that day's strip.

Published on July 30, 2014 04:00

July 29, 2014

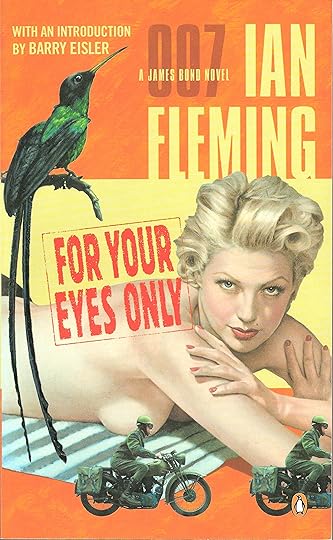

For Your Eyes Only | "For Your Eyes Only"

The final story (chronologically) in For Your Eyes Only is the one that gives the collection its name. It's also the only one that made its debut in the collected volume, not having been published anywhere else previously.

The final story (chronologically) in For Your Eyes Only is the one that gives the collection its name. It's also the only one that made its debut in the collected volume, not having been published anywhere else previously.Fans of the film For Your Eyes Only will recognize the story of a young woman who goes looking for revenge against the man who killed her parents. In the film it's Malina Havelock with her crossbow, but in Fleming's story she's Judy Havelock and prefers a traditional bow.

Bond is involved because M was a close friend of the Havelocks and even served as best man at their wedding. There are shades of Moonraker here as M uncomfortably navigates the ethical dilemma of using a government agent in what could be construed as a personal vendetta, especially since the Havelock mission involves outright assassination instead of just beating a cheater at cards. There's a wonderful scene though where M is absolutely stuck and puts Bond in the unfair predicament of making the decision. Bond gallantly suggests that assassination is the logical, impersonal response to a foreign agent who murders British citizens on British soil. Easily the best relationship in the entire Bond series is the one between Bond and his boss. It's very much a relationship between father and son, though with plenty of Stiff Upper Lip to keep it from getting sappy.

In the course of their conversation, the topic of Bond's toughness comes up. Bond truly does have to sacrifice something when he volunteers to kill the Havelocks' murderer. He's not used to those kinds of decisions and he stammers quite a bit as he tries to support M in such unfamiliar territory. Bond says that he's able to withstand all kinds of hardship "if I have to and I think it's right, sir." He realizes that's a weak answer and continues, even more lamely, "I mean ... if the cause is - er - sort of just, sir." In the end, I got the feeling that Bond volunteers not because he's 100% convinced it's the right thing to do, but because he's 100% convinced that that's what M wants. It's a beautiful act of selflessness, though one I could easily see the Bond of Live and Let Die doing as easily as the post-Dr No Bond.

In the course of their conversation, the topic of Bond's toughness comes up. Bond truly does have to sacrifice something when he volunteers to kill the Havelocks' murderer. He's not used to those kinds of decisions and he stammers quite a bit as he tries to support M in such unfamiliar territory. Bond says that he's able to withstand all kinds of hardship "if I have to and I think it's right, sir." He realizes that's a weak answer and continues, even more lamely, "I mean ... if the cause is - er - sort of just, sir." In the end, I got the feeling that Bond volunteers not because he's 100% convinced it's the right thing to do, but because he's 100% convinced that that's what M wants. It's a beautiful act of selflessness, though one I could easily see the Bond of Live and Let Die doing as easily as the post-Dr No Bond.Sadly, Bond's relationship with Judy isn't as great. That's an understatement; Judy is a tragedy of a character along the lines of Pussy Galore. She spends most of the story as an amazingly strong and independent woman, but completely melts by the end. With Pussy, it was Bond's manliness that changed her, but with Judy it's just the natural, womanly reaction (according to Fleming) to having killed someone. Bond keeps telling her throughout the story that murder is "man's work" and the end of the story reinforces that notion as she sobs in his arms and lets him make a woman out of her. Gag.

Published on July 29, 2014 04:00

July 28, 2014

For Your Eyes Only | "From a View to a Kill"

"From a View to a Kill" was first printed in the Daily Express a few months after Goldfinger came out, making it the earliest of the For Your Eyes Only stories to be published. It starts well with the dramatic murder of a NATO motorcycle courier and Bond's being called in to help investigate.

"From a View to a Kill" was first printed in the Daily Express a few months after Goldfinger came out, making it the earliest of the For Your Eyes Only stories to be published. It starts well with the dramatic murder of a NATO motorcycle courier and Bond's being called in to help investigate.Bond's involvement is purely political. NATO command already isn't happy with the security risk of Britain's having it's own offices outside of the main headquarters, so M sends them 007 as a way of showing that Britain is involved and taking the matter seriously. Bond was nearby anyway, relaxing in Paris after a failed mission to help a defector come over from Hungary.

I had a hard time connecting to the investigation itself. Bond's a capable detective, but in the end he solves the thing with intuition and being the only person to suspect a previously unnoticed lead, which is a tactic that M specifically instructed Bond to take. I'm not saying that Bond merely stumbles across the right clues, just that his investigative techniques aren't especially compelling. And I'm not sure how I feel about the rather outlandish revelation of who's behind the murder. On the one hand, it's more fantastical than its lead-up prepared me for. On the other hand, it's kind of cool and a taste of things to come in the Bond series.

The meaning of the title isn't explicit in the story, but one theory is that it's a hunting reference. "D'ye Ken John Peel?" was a popular song in the nineteenth century about a fox hunter and one version includes the line, "From a find to a check, from a check to a view, from a view to a kill in the morning." In other words, first you see the prey, then you kill it. It's not one of Fleming's stronger titles, but at least it makes me hear Duran Duran in my head when I read it.

There's one bit of character development for Bond in the story, though it's from a small throwaway line about Bond's drinking preferences. Fleming writes that Bond dislikes Pernod "because its liquorice taste reminded him of his childhood." He gives no more detail than that, but it's the first hint that Bond's childhood wasn't completely happy and full of golf and fancy tea parties. A curious piece of the puzzle as we try to reconstruct Bond's early life as Fleming imagined it.

Published on July 28, 2014 04:00

July 25, 2014

For Your Eyes Only | "The Hildebrand Rarity"

"The Hildebrand Rarity" was published in Playboy just a month before For Your Eyes Only came out. In it, Bond is in the Seychelles Islands (northeast of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean), having just finished a security check for the British Navy. Most of the stories in For Your Eyes Only occur while Bond's hanging out after some routine mission ("Risico" and "For Your Eyes Only" being the exceptions) and this time Bond has a few days to kill before a ship arrives to take him home.

"The Hildebrand Rarity" was published in Playboy just a month before For Your Eyes Only came out. In it, Bond is in the Seychelles Islands (northeast of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean), having just finished a security check for the British Navy. Most of the stories in For Your Eyes Only occur while Bond's hanging out after some routine mission ("Risico" and "For Your Eyes Only" being the exceptions) and this time Bond has a few days to kill before a ship arrives to take him home.We already know from Live and Let Die that Bond's an accomplished diver, and that's how he's spending his time on his break. When a buddy of his on the islands gets an opportunity to help an American philanthropist track down a rare fish - the Hildebrand Rarity - for the Smithsonian, the buddy recommends that Bond come along too. (Side note for Creature from the Black Lagoon fans: the plan is to use Rotenone to catch the fish.) Unfortunately, the wealthy Milton Krest is a first class jerk who insults his guests and uses his charitable foundation to write off pleasure expenses. Most heinous though, he has a habit of beating his wife Elizabeth with a stingray tail when she displeases him.

Bond connects with Elizabeth, partly because she's British, but mostly because she seriously needs a friend. This is what I love most about "The Hildebrand Rarity" and one of the reasons it's my favorite in the collection. Elizabeth is beautiful, but there's not the usual sexual tension between her and Bond. I mean there is tension there, but it comes from knowing how Bond usually interacts with beautiful women and from knowing that Milton Krest is a dangerous man to offend. If Bond acts as he usually does, life on Krest's yacht is probably going to become deadly.

But that's not what happens and Bond simply befriends the woman. Her nervousness and unsuccessfully concealed desperation touch Bond and turn him into a listening ear for her. He becomes an oasis of comfort and normality in the life of fear that she's leading, which is a really odd role for him to take. But he wears it well and it's another great example of the post-Dr No Bond at work.

Published on July 25, 2014 04:00

July 24, 2014

For Your Eyes Only | "Quantum of Solace"

Originally published in Cosmopolitan a couple of months after Goldfinger, "Quantum of Solace" is the one short story in For Your Eyes Only not based on a plot outline for CBS's scrapped Bond series. Instead, Fleming wrote it as an homage to W Somerset Maugham (Of Human Bondage, Ashenden: The British Agent, The Razor's Edge), one of Fleming's favorite authors. According to the British Empire website, Maugham enjoyed writing about "the remote locations of the quietly magnificent yet decaying British Empire" and the people who worked and lived there. He was a master at juxtaposing "realistic depictions of the boredom and drudgery" of plantation life or civil service with "the desire and trappings of what [British citizens who lived in those places] would regard as civilisation."

Originally published in Cosmopolitan a couple of months after Goldfinger, "Quantum of Solace" is the one short story in For Your Eyes Only not based on a plot outline for CBS's scrapped Bond series. Instead, Fleming wrote it as an homage to W Somerset Maugham (Of Human Bondage, Ashenden: The British Agent, The Razor's Edge), one of Fleming's favorite authors. According to the British Empire website, Maugham enjoyed writing about "the remote locations of the quietly magnificent yet decaying British Empire" and the people who worked and lived there. He was a master at juxtaposing "realistic depictions of the boredom and drudgery" of plantation life or civil service with "the desire and trappings of what [British citizens who lived in those places] would regard as civilisation."Fleming evokes all of that in "Quantum of Solace". It's an odd Bond story in that Bond is only there to serve as an audience as the British Governor of the Bahamas relates the story of Philip and Rhoda Masters, a tragic couple who lived on the island earlier. "Quantum of Solace" opens after a dull dinner party where Bond and the Governor are the last remaining attendees. The two men have nothing in common with each other and each is completely uncomfortable. Bond is in the area after blowing up a boat full of contraband weapons. He's bored by the Governor, a lifelong civil servant who values quiet and routine. Desperate to get the conversation going somewhere interesting, Bond makes an intentionally offensive comment about wanting to marry an airline hostess if anyone at all. The Governor refuses the bait, but is reminded about the Masterses because Rhoda was an airline hostess when Philip met her.

The bulk of "Quantum of Solace" is the Masterses' story, a tragedy of betrayal brought on by the boredom and drudgery that Rhoda feels towards life in the Bahamas. She wants the trappings of a proper British life, but can't get them out in the colonies, so she acts out, hurting her husband enormously. The story's title refers to a theory of the Governor's: that bad marriages can endure if each member can offer the tiniest amount of comfort to the other. Rhoda was unable to do that and in the end it damaged her as much as Philip.

It's a powerful story of heartbreak, not a rousing Bond adventure, but that's the point it's trying to make. I have to spoil it to talk about it adequately, but Bond ultimately learns that Rhoda was in fact a very dull woman he'd sat next to during dinner. He realizes that he misjudged her and that what he's always thought of as an adventuresome life has been empty of the emotion and meaning - however tragic - that filled hers. For that reason, it's an important story in Bond's character development, second so far only to Dr No. Bond continues to be confronted by his own self-absorption and to grow from those experiences.

Published on July 24, 2014 04:00

July 23, 2014

For Your Eyes Only | "Risico"

As we move into some of Fleming's short stories about James Bond, I need to talk a bit about chronology. There are three ways I could integrate the short stories with Bond's longer adventures: I could write about them in the order in which they were originally published by magazines and newspapers, I could write about them in the order in which they were collected in book form, or I could write about them as they happened within the chronology of Bond's career.

As we move into some of Fleming's short stories about James Bond, I need to talk a bit about chronology. There are three ways I could integrate the short stories with Bond's longer adventures: I could write about them in the order in which they were originally published by magazines and newspapers, I could write about them in the order in which they were collected in book form, or I could write about them as they happened within the chronology of Bond's career.So far, I've been tackling this project in publication order and there's been no conflict because Fleming wrote and published the novels in the same order that they occur in Bond's life. With the short stories though it gets more complicated, especially when we get into the stories collected in Octopussy and The Living Daylights, which were published after Fleming's death and clearly take place earlier in Bond's career rather than after the dramatic events that closed Fleming's series.

Because I'm interested in Bond as a fictional character and how Fleming developed him, I'm going to write about the short stories as they happened to Bond. But that's going to be an anomaly in this project. After Fleming's death, a consistent chronology of Bond's life becomes impossible. So while I'll include the non-Fleming books in the project, I'm not going to pretend that they're about the same character. That'll free me to just take them in publishing order and transition to thinking about James Bond as a phenomenon instead of a character.

There are a couple of major chronologies that put Fleming's stories in order of when they took place in Bond's life. The one I like best is John Griswold's from

Ian Fleming's James Bond: Annotations and Chronologies for Ian Fleming's James Bond Stories

. Griswold uses the publication order of the novels and then fits the short stories into that. It's nice and simple as opposed to the other major chronology which rearranges some of the novels.

There are a couple of major chronologies that put Fleming's stories in order of when they took place in Bond's life. The one I like best is John Griswold's from

Ian Fleming's James Bond: Annotations and Chronologies for Ian Fleming's James Bond Stories

. Griswold uses the publication order of the novels and then fits the short stories into that. It's nice and simple as opposed to the other major chronology which rearranges some of the novels.Both chronologies agree though that "Risico," the fourth out of the five stories collected in For Your Eyes Only, takes place earliest; soon after Goldfinger. That's because M mentions the Mexican assignment that Bond was musing about at the beginning of Goldfinger as happening "earlier this year."

It comes up again in "Risico" (named after the way a character mispronounces the word "risk") because the short story has Bond on another drug case. This time he's tasked with shutting down the flow of heroin into England from Italy. I don't want to say too much about the plot, because it's a twist-ending kind of short story, but if you've seen the movie For Your Eyes Only, you're familiar with the characters of Kristatos, Colombo, and Lisl Baum (renamed Lisl von Schlaf in the film) and their relationships with Bond and each other.

Fleming developed the story for a Bond TV show that never made it to the air. CBS had been happy with the results of the "Casino Royale" episode of Climax! and wanted more, so Fleming wrote some plot outlines. After CBS dropped the idea, he worked the outlines into four of the short stories collected in For Your Eyes Only. The fifth is the one we'll talk about tomorrow, but "Risico" was the last of them published, debuting in the Daily Express newspaper simultaneously with the publication of the whole For Your Eyes Only collection.

Published on July 23, 2014 04:00

July 22, 2014

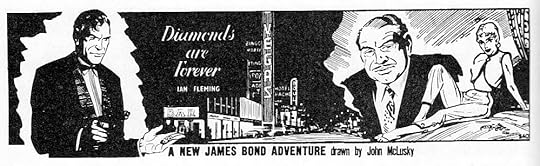

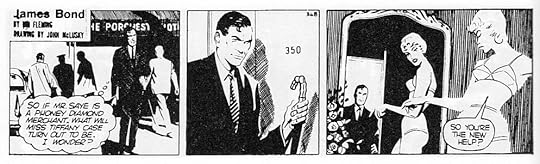

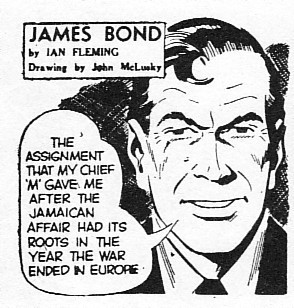

"Diamonds Are Forever": The Comic Strip

By "Diamonds Are Forever," the quality of the James Bond strip has stabilized into mediocre. Artist John McLusky has moments of greatness where he's put a lot of thought into a composition or is clearly having fun with a particular panel, but he's inconsistent. There are just as many examples of his work looking rushed and unfinished.

For his part, writer Henry Gammidge continues presenting Bond as a stock adventure hero. I love that he occasionally takes a panel to describe what Bond's eating or to portray some other detail from the book that's insignificant to the plot, but even though Bond's narrating the strip, Gammidge offers no look into what makes Bond tick as a character. He doesn't even present Fleming's take on Bond, much less offer any insight of his own.

This is especially problematic in Bond's relationship with Tiffany Case. That's a complicated relationship in the novel, with Bond needing to use Tiffany, but highly reluctant to hurt her. When he finally confesses that he's falling in love with her, Fleming's already convinced me that that's true. And the same is true of Case's feelings about Bond. None of that is present in the comic strip though, so we just have Bond and Case running around together and then suddenly being in love at the end. The story hasn't earned that revelation.

It's also unearned when Bond grows impatient in his undercover role as a lackey for the mob. Unlike the languid pace of the novel, the strip is so brisk that it's hard to believe that Bond is bored. So when he disobeys the mob's instructions to him about not gambling in their facility, it's nothing more than an act of petulance. With nothing motivating it, it just feels like Bond does it unnaturally in order to keep the plot moving.

That kind of rushing also weakens the power of the telegram the mob gets from England blowing Bond's cover. There's no mention of how the London branch of the mob knows that Bond isn't actually Peter Franks; it just says that Bond's a fake and should be killed. Gammidge doesn't seem interested in actually adapting the story to comic strip form; just translating it as efficiently as possible to hit all the scenes. Thanks to McLusky, that translation is sometimes beautifully done, but not always.

There are other problems too that have nothing to do with the story. Like for instance when Felix refers to his previous career in the FBI instead of the CIA. Or the numerous instances of word balloons being placed oddly so that the eye reads them out of order. The lettering is a problem that stays with the strip at least into "From Russia With Love."

There's too much Fleming in the James Bond strip and I like too much of McLusky's work to let me hate it or lose interest. I'm always curious to see how McLusky is going to interpret a character or setting. But I also don't love or especially recommend the strip. It captures the stories, but not the soul of Fleming's work. And its creators don't offer enough of their own to replace that missing spirit and make the strip great.

Published on July 22, 2014 04:00

July 21, 2014

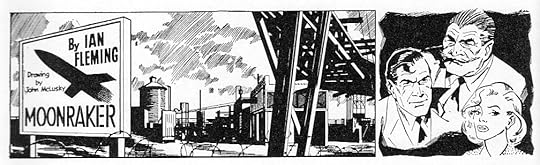

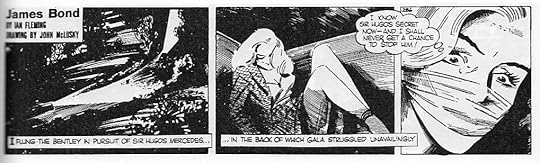

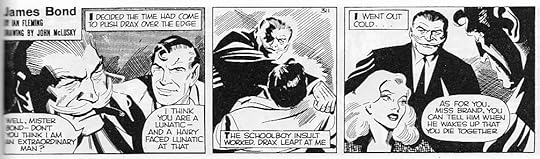

"Moonraker": The Comic Strip

With their adaptation of Moonraker, Henry Gammidge and John McLusky depart even further from the tone of Ian Fleming. Now Bond isn't just narrating in caption boxes, he's drawn talking directly to the reader. As I said when I wrote about the Live and Let Die adaptation, it's no good comparing the strip to Fleming's style. The author was absolutely right to be concerned that the comics would dumb down his stories and it's best that I just accept it.

It's still interesting though to see what changes Gammidge made to Fleming's plot, because we do get a couple in "Moonraker." The whole day-in-the-life-of-Bond opening is gone, so we don't get to meet Bond's secretary or even read mention of the spy's home life and personal habits. Instead, with no explanation as to why, Bond begins the story by relating the public history of Hugo Drax.

It's still interesting though to see what changes Gammidge made to Fleming's plot, because we do get a couple in "Moonraker." The whole day-in-the-life-of-Bond opening is gone, so we don't get to meet Bond's secretary or even read mention of the spy's home life and personal habits. Instead, with no explanation as to why, Bond begins the story by relating the public history of Hugo Drax.After that, Bond's first in-story appearance is sitting in M's office and being told that Drax cheats at cards. Readers of the novel understand why that's important, but the comic doesn't really say and the mission comes across as embarassingly petty, especially without the benefit of M's own involvement. There's no mention of personal favors and M isn't even revealed to be a member at Drax's club. He doesn't go to Blades with Bond, but sends the agent out to investigate on his own as if this were any other assignment.

Once the card game begins between Bond and Drax though, the rest of the story plays out like it does in the novel, though severely abridged. We never do get an explanation of why the Secret Service is involved in a murder investigation on British soil, and there's no mention of the mystery of Drax's mustachioed men.

McLusky has a lot of fun with Drax's appearance though, including his comical moustache. And he draws a gorgeous Gala Brand, though she's blonde for some reason. He's still working on those facial expressions and I've started to notice that his Bond has a perpetual smirk. I kind of like it, but it's not much like the super dark Bond of these early novels. He's more of a children's adventure hero, but that really fits the tone that Gammidge seems to be going for.

Published on July 21, 2014 04:00

July 18, 2014

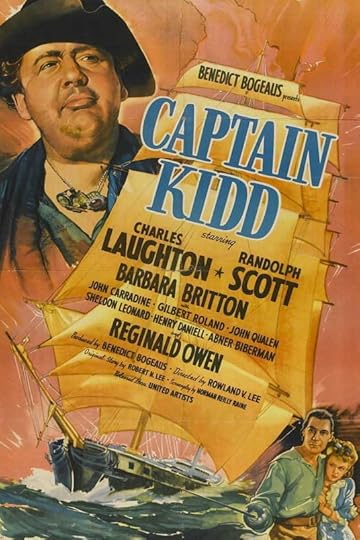

Captain Kidd (1945)

Who's In It: Charles Laughton (Mutiny on the Bounty, The Hunchback of Notre Dame), Randolph Scott (Ride Lonesome, Ride the High Country), Barbara Britton (The Revlon Girl), John Carradine (The House of Dracula, Billy the Kid vs. Dracula), and Reginald Owen (A Christmas Carol).

What's It About: History walks the plank in this version where the pirate William Kidd (Laughton) pretends to go straight in order to escort a British treasure ship back to England. But his plans are complicated not only by the mutual treachery between him and his men (including Carradine), but also by the arrival of a mysterious gunner (Scott) with secret motives of his own.

How It Is: Whenever villains are described in literature as "toadlike," Charles Laughton is the man I think of. Paunchy and blubbery, Laughton isn't a traditional pirate captain, but he's perfect for this role. His Captain Kidd is a scheming, slippery devil who makes up in betrayal what he lacks in brawn.

Pitted against him is Randolph Scott, the straight-shooting Western star who's traded in his six-shooters for a rapier. At first, Scott feels bland as Master Gunner Adam Mercy, but he becomes a great juxtaposition to Kidd. He's not exactly dashing, but he is handsome and honorable and an effective straight man to Laughton's wickedly humorous performance. Scott makes Laughton that much more fun in comparison.

Carradine, on the other hand, serves to give Laughton's Kidd some genuine menace. Carradine exudes danger and deadliness, so seeing him evenly matched and genuinely threatened by Kidd was a constant reminder to take Kidd seriously, even if I was laughing at him.

Rounding out the cast are Barbara Britton and Reginald Owen. Britton plays a noble woman traveling on the treasure ship that Kidd is escorting, but she doesn't have much to do other than raise the stakes for Scott. Owen (most famous to me for playing Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1938 Christmas Carol) is much more fun as a servant hired by Kidd for the doomed task of helping the salty captain appear respectable in polite society. Once everyone's on the same ship, Owen's character is an amusing wild card, since he's a good-hearted fellow, but also has a decent working relationship with the captain.

Captain Kidd isn't a classic of the pirate genre by any means, but Laughton's performance is a joy to watch and there's enough double-crossing and swashbuckling to make the rest of it worthwhile.

Rating: Four out of five hidden caves with buried treasure.

Published on July 18, 2014 04:00

July 17, 2014

Goldfinger by Ian Fleming

I'll save my full commentary about the movie Goldfinger until we get there, but Fleming's novel is a lot like it in more than just plot and characters. Both versions mark a significant shift in tone for their series. I'd forgotten that was true for the novel as well as the film.

I'll save my full commentary about the movie Goldfinger until we get there, but Fleming's novel is a lot like it in more than just plot and characters. Both versions mark a significant shift in tone for their series. I'd forgotten that was true for the novel as well as the film.Fleming introduces the idea right away. The book opens with Bond in Miami, waiting on a connecting flight after a particularly hairy and violent mission in Mexico. Most of the first chapter is Bond's sitting in an airport lounge, brooding about the assignment over his double bourbon. That's not at all unusual for the Bond we've come to know over the series so far, but Fleming throws in a twist at the end of the chapter and has Bond thinking to himself, "Cut it out. Stop being so damned morbid. All this is just a reaction from a dirty assignment. You're stale, tired of having to be tough. You want a change." And that's exactly what Bond - and his readers - get.

As if on cue, an American millionaire named Du Pont approaches Bond and recognizes him from their time together in Casino Royale. He and his wife sat next to Bond at the baccarat game against Le Chiffre and Du Pont wonders if Bond might be available to help him out with another situation involving cards. Du Pont is being swindled at Canasta by a man named Goldfinger and wants Bond to help him get back at the cheater. Bond's already facing an overnight layover anyway, so he accepts.

I don't want to recap the whole plot, but if you've seen the film you know that M has a case waiting for Bond involving Goldfinger when Bond returns to London. It's even more a coincidence in the novel than in the film, but Fleming makes it work by giving the book such a light tone that a big, opening coincidence isn't as jarring as it would have been in a more serious story.

I don't want to recap the whole plot, but if you've seen the film you know that M has a case waiting for Bond involving Goldfinger when Bond returns to London. It's even more a coincidence in the novel than in the film, but Fleming makes it work by giving the book such a light tone that a big, opening coincidence isn't as jarring as it would have been in a more serious story.Several things work to give Goldfinger a breezier feel than the previous novels. For one thing, like in the movie, the gadgets have been cranked up a couple of notches. When Bond tries to get closer to Goldfinger by posing as a bored playboy in search of direction, he requisitions a sporty Aston Martin DB III from Q-branch to drive instead of his own, classy Bentley. It comes tricked out too, though not with oil slicks and ejector seats. It's gadgets are more realistic: reinforced bumpers, secret compartments, a radio pick-up for his homing device, that kind of thing. Bond also makes good use of shoes with knives that come out when he detaches the heels.

And of course, the bad guys get some gadgets too, particularly Oddjob's famous, steel-rimmed bowler. For that matter, Oddjob himself livens up the book. He's an awesome henchman - the best in the series so far - with more personality than the film version, though he doesn't speak any more than the movie Oddjob does. The literary Oddjob isn't just a hulking brute, he's a martial artist and a master with the bow and arrow as well as his lethal hat.

Even so, Oddjob isn't as great a villain as his boss. Auric Goldfinger is Bond's best villain so far too, in part because Fleming gives him and Bond so much time together. As Bond keeps inserting himself into Goldfinger's business, they have many opportunities to talk and get on each other's nerves. The dialogue between the two of them is the best part of the novel. Goldfinger is an amazing criminal mind, but he's so delightfully arrogant about it that it's a blast watching Bond try to poke holes in his bluster.

Even so, Oddjob isn't as great a villain as his boss. Auric Goldfinger is Bond's best villain so far too, in part because Fleming gives him and Bond so much time together. As Bond keeps inserting himself into Goldfinger's business, they have many opportunities to talk and get on each other's nerves. The dialogue between the two of them is the best part of the novel. Goldfinger is an amazing criminal mind, but he's so delightfully arrogant about it that it's a blast watching Bond try to poke holes in his bluster.My favorite line in the book is Bond's response when Goldfinger brags that if Oddjob used the appropriate blow on any one of seven spots on Bond's body, the spy would die instantly. "That's interesting," Bond deadpans. "I only know five ways of killing Oddjob with one blow." There are lots of lines like that and what we're seeing in Goldfinger is the introduction of the quipping James Bond that the films are so known for.

This easier attitude shows up in Bond's relationships with women too. He's been described as a womanizer in the series, but we've never actually seen him just hook up for its own sake without spending a lot of time with a woman. When he meets Goldfinger's secretary, Jill Masterton, Bond fixes it so that Goldfinger has to let Jill accompany Bond on his train ride from Miami to New York. He doesn't realize yet how deadly Goldfinger is, so he and Jill spend the trip having sex and it's obvious that the relationship isn't any more than that to either of them.

Pussy Galore is usually thought of as the "Bond girl" from Goldfinger, but the novel really doesn't have a single, romantic interest for the spy. He meets Jill's sister Tilly in France while she's pursuing Goldfinger (Bond doesn't find out until much later about Jill's death by gold paint) and she sticks around a lot longer than she does in the film, but she's a lesbian and not at all interested in Bond. For that matter, Pussy is too, which should have ended Bond's sexual activity in the book right there, but unfortunately, it doesn't.

Pussy Galore is usually thought of as the "Bond girl" from Goldfinger, but the novel really doesn't have a single, romantic interest for the spy. He meets Jill's sister Tilly in France while she's pursuing Goldfinger (Bond doesn't find out until much later about Jill's death by gold paint) and she sticks around a lot longer than she does in the film, but she's a lesbian and not at all interested in Bond. For that matter, Pussy is too, which should have ended Bond's sexual activity in the book right there, but unfortunately, it doesn't.The novel's huge weakness is Fleming's attitude towards lesbians, which is a product of its time, but still inaccurate and awful to modern readers. Bond leaves Tilly alone once he learns her preference, but Fleming can't let the book end without Bond having a reward for a job well done, so he has Pussy become heterosexual at the last minute. Pussy had been flirting with Bond for a while, so I hoped I'd be able to read her as bi and be done with it, but Fleming makes it very clear that this isn't the case. She explicitly tells Bond that she only liked women because she'd never met a real man before and that her lesbianism was the direct result of being molested as a child. She makes a complete personality change from being an awesome, wise-cracking scoundrel to being all fluttery and girlish with her new hero. I wish that was all of it, but there's also an earlier scene in which Bond thinks about Tilly and expresses his extremely dated thoughts on homosexuality and gender identity in general.

Back to more positive things though, when Bond learns about Jill's death, he's deeply hurt by it. One of the advantages that the books have over film is getting to spend so much time in Bond's head. In the movies, women Bond sleeps with often end up dead and it usually seems like he doesn't care that much. That's not the case in Goldfinger and it's a nice continuation of the less selfish Bond we started to see in Dr No. Even though Bond's hook up with Jill had no attachments, he still liked her and it devastates him that Goldfinger murdered her because of something Bond did. His relationship with Tilly is also surprisingly gentle and protective once he realizes that romance is off the menu.

Back to more positive things though, when Bond learns about Jill's death, he's deeply hurt by it. One of the advantages that the books have over film is getting to spend so much time in Bond's head. In the movies, women Bond sleeps with often end up dead and it usually seems like he doesn't care that much. That's not the case in Goldfinger and it's a nice continuation of the less selfish Bond we started to see in Dr No. Even though Bond's hook up with Jill had no attachments, he still liked her and it devastates him that Goldfinger murdered her because of something Bond did. His relationship with Tilly is also surprisingly gentle and protective once he realizes that romance is off the menu.Another example of Bond's developing attitude towards women is some delirious thoughts he has when waking up after thinking he and Tilly were about to be killed. This is before he knows Tilly's a lesbian, so he wonders about Heaven and whether Tilly is with him and how awkward it'll be if Vesper is there too. It's kind of a silly scene, but it's also important because it shows that - at least subconsciously - Bond is still concerned about what Vesper might think. He still feels some loyalty to her, which means that he appears to have forgiven her a little. It's been a gradual change, but this is a different Bond from the dark, extremely angry person at the end of Casino Royale and the beginning of Live and Let Die.

One last thing, because I'm still trying to track Fleming's mentions of Bond's childhood and where Bond's being an orphan was introduced. The famous scene in which Bond and Goldfinger play golf takes place at a club near Goldfinger's English home, which happens to be the club where Bond learned to play as a teenager. Fleming doesn't explicitly say that Bond grew up near there, but does state that Bond played there "two rounds a day every day of the week." Like with the childhood teas he remembered attending in Diamonds Are Forever, Bond appears to have had a privileged youth, which is hard to reconcile with the angry orphan of the Pierce Brosnan and Daniel Craig films.

Published on July 17, 2014 04:00