Michael May's Blog, page 160

July 16, 2014

Poseidon (2006)

Who's In It: Josh Lucas (Hulk), Kurt Russell (The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China), Jacinda Barrett (Zero Hour), Richard Dreyfuss (Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind), Emmy Rossum (The Day After Tomorrow), and Mía Maestro (Alias)

What's It About: A rogue wave flips over an ocean liner, forcing passengers to make their way up towards the former bottom of the ship where they hope to find rescue.

How It Is: Surprisingly good. When Poseidon hit movie theaters, I couldn't have been more disinterested. My childhood dislike of the original Poseidon Adventure combined with my disaster movie fatigue (which went back to the late '90s after Twister, Volcano, Armageddon, Titanic, etc., etc.) to keep me far away. But having revisited the 1972 Poseidon Adventure and enjoyed it, and having not seen a recent disaster movie in a very long time, the timing was right for me to watch Poseidon with an open mind.

Frankly, watching it so closely after the 2005 Hallmark mini-series also helped. That version was so padded out, so cheaply made, and adapted the original's characters in such unflattering ways that I was impressed when Poseidon didn't make those same mistakes. It's a low bar to step over, but Poseidon does it and delivers some good stuff in the process.

My hopes for the movie rose during the first few seconds of the credits when I was reminded that the director is Wolfgang Petersen. I haven't loved all of Petersen's films, but I have soft spots for Outbreak and Air Force One and there's no denying that he's a capable filmmaker. I was expecting Poseidon to be directed by someone like Roland Emmerich, so I relaxed quite a bit when I saw Petersen's name.

And I relaxed some more when I saw the long, continuous, opening shot of the ocean liner as the camera flies around the outside of the impressive ship, occasionally picking up glimpses of Josh Lucas running on deck. There's a lot of money on screen there, which is a huge relief after the crude simulator-quality animation of the Hallmark mini-series.

The pace of the story is faster than any previous version, starting out on New Year's Eve and letting viewers learn about characters mostly during the disaster rather than through an abundance of buildup and back story. There are some brief introductions before the wave hits, but there are also less characters than in earlier versions, so it doesn't feel tedious.

Speaking of the characters, they aren't nearly as fascinating as those from the original, but Poseidon still has some nice moments with them. Unlike the Hallmark version, Poseidon doesn't use any names from 1972, but there are still some analogues to the originals. Josh Lucas doesn't play a priest, but he is a guy who values strength and a professional gambler used to surviving alone and by his wits. That worldview is challenged though when he finds himself feeling protective of a single mother (Barrett) and her son (Jimmy Bennett, who played young Jim Kirk in the 2009 Star Trek reboot).

Richard Dreyfuss' character is the most interesting. He's a gay man who's just been dumped and is heartbroken to the point of considering suicide. He's actually on deck and climbing over the rail when he sees the enormous wave rushing towards the ship, which immediately kicks his will to live into gear and sends him rushing inside to warn the other passengers. That will is still strong later when he joins the group of hopeful escapees and does something heinous to another person in order to save himself. And the guilt of that action then pushes him into protecting a terrified woman (Maestro) even when doing so puts himself in jeopardy. The film doesn't pull everything out of Dreyfuss' character arc that it could, but the arc is still there and it's a good one, even if Red Buttons' similar, but more honorable character was more touching in '72.

The group of characters that didn't work for me was Kurt Russell, Emmy Rossum, and Mike Vogel (Cloverfield). Russell is Rossum's father, while Vogel is the boyfriend to whom she's secretly engaged. There's a bunch of stuff about when they're going to tell Russell about the engagement and Russell is trying to be the threatening dad, but is mostly just ticking the other two off. All of which comes to a head during the disaster a la Armageddon (or Transformers: Age of Extinction) and yadda yadda yadda. It's great seeing Russell be all tough and actiony during the disaster, but his family's drama is pretty lame.

What saves Russell's character and the others though is that there aren't a lot of obvious parallels to the '72 version. Dreyfuss and Buttons come closest, with Lucas and Hackman being a distant second, but their individual stories are so different that it's not really worth comparing them. That's true of the rest of the movie as well. There are a lot of set pieces from '72 that get repeated exactly in the Hallmark version, but only one or two make it into Poseidon. One that comes to mind is when the group leaves the ballroom against the advice of an authority figure, but even then there's no big confrontation where everyone has to make a decision. The captain (Andre Braugher from Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer and Brooklyn Nine-Nine) encourages everyone to stay and wait for rescue, but doesn't try to force it and there's zero drama when the main characters sneak off on their own.

That sounds like criticism - and I admit I was disappointed - but it's indicative of something that is actually a strength of the film. It constantly finds its own way to do things, making it a reimagining of the '72 story rather than a remake. I have no idea which version is more faithful to Paul Gallico's novel or how the book affects the decisions made by Irwin Allen and Wolfgang Petersen, but Poseidon is different enough that it works as almost a whole new story that just uses the same concept. Taken that way, it's better than most other modern disaster films and has enough going for it (like an escape plan with an actual hope for survival at the end) that I like it quite a bit.

Rating: Four out of five dashing gamblers

Published on July 16, 2014 04:00

July 14, 2014

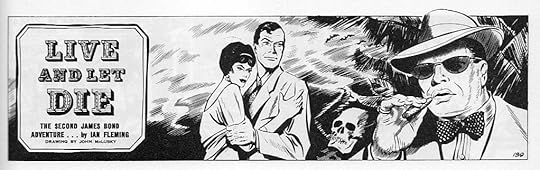

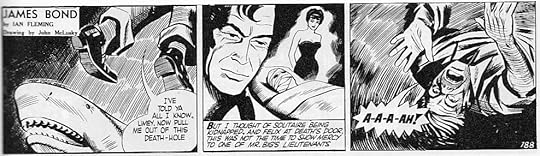

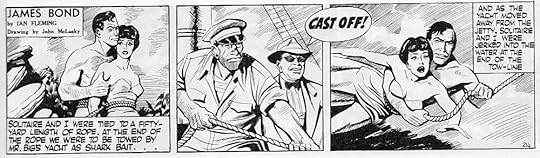

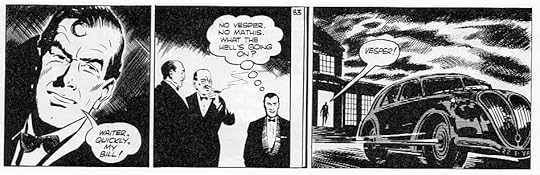

"Live and Let Die": The Comic Strip

Writer Anthony Hern had toned down parts of Casino Royale for the Daily Express' comic strip adaptation, but he kept all the story beats and the general tone of Fleming's novel. He was replaced on the strip in December 1958 though starting with the adaptation of Live and Let Die. His successor was Henry Gammidge, who made a couple of immediate changes to distance the strip from Fleming even more.

Most startling is the use of first person narration by Bond. I don't know if it was inspired by writers like Raymond Chandler, but if so, it's a sad imitation. Gammidge's captions read like a children's book and there's no effort to explain why Bond's telling this story or to whom.

Another major difference between Hern's adaptation and Gammidge's is the length. The "Live and Let Die" strip is a little over 60% the length of "Casino Royale" and it feels rushed in comparison. Without "Casino Royale" to hold it up against though, I'm not sure I would've noticed. Gammidge is certainly more economical than Hern was, but he still hits all the major plot points of Fleming's book without cutting scenes. He even manages to acknowledge Bond's nervousness during his rough flight to Jamaica.

John McLusky's art maintains the strengths and weaknesses it had in "Casino Royale." He's still not awesome at facial expressions, but his Solitaire is slightly more emotive than Vesper was. His action scenes are still dynamic though, his compositions are eye-catching, and he continues to pull me into the story with detailed representations of the fashions, architecture, and vehicles of the '50s.

With its exciting art and fast-paced story, I imagine that "Live and Let Die" was able to appeal to newspaper readers who'd never read the book. To me, it feels less like reading Fleming than "Casino Royale" did, but I'm not so sure that's a drawback. As much as I dislike Bond's narration, it forces me to consider the strip on its own terms instead of just comparing it to Fleming. It was created after the adventure strip boom of the '30s and '40s, but it's as much heir to those comics as it is an adaptation of Fleming's work. I certainly wouldn't hold it up next to Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff in terms of quality, but as an amalgamation of those guys and Fleming, I think it's at least interesting. As I continue reading it, I'm going to try to keep that in mind and judge it as it's own thing rather than how closely it follows Fleming.

Published on July 14, 2014 04:00

July 11, 2014

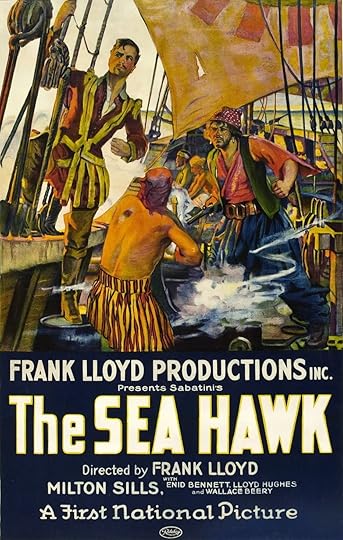

The Sea Hawk (1924)

Who's in it: Milton Sills (The Sea Tiger, The Sea Wolf), Enid Bennett (1922 Robin Hood), Lloyd Hughes (1925 The Lost World), and Wallace Beery (1922 Robin Hood, 1925 The Lost World)

What's it about: A former English privateer (Sills) is framed for murder and sold into slavery at sea, but rises to become a captain in the Barbary corsairs.

How it is: I haven't read Rafael Sabatini's novel yet, but I'm familiar with other work of his and this feels like a faithful adaptation of something he would write. The heroic Sir Oliver Tressilian tries to do the right thing by his half-brother (the ridiculously good-looking Hughes) who makes the mistake of killing a man in a duel without witnesses. But Sir Oliver is rewarded for his trouble by being suspected of the murder himself and the cowardly brother not only lets Sir Oliver take the fall; he also sells Sir Oliver to an unscrupulous captain (Beery) and starts making time with Sir Oliver's girl (Bennett).

I don't usually describe women as "somebody's girl," but Lady Rosamund Godolphin doesn't have enough will or personality to be her own person. She's completely wishy-washy, has no faith in Sir Oliver, and is really nothing more than a plot device for various characters to scheme and fight over. It's unbelievable that Sir Oliver goes to such effort to win her back.

But he does, and through a series of events at sea, he finds himself freed by Muslim corsairs and made a captain. True to Sabatini, lots of characters come and go, bringing sub-plots and intrigue with them. That gives The Sea Hawk an epic feel, which also reminds me of Sabatini.

There's much more good about the film than bad. The actors are quite convincing, even Bennett, considering what she's got to work with. I quite liked the complicated relationship between the brothers, too. Young Lionel doesn't start off evil, but he's driven to evil deeds by circumstances and weakness of character. All the antagonists in The Sea Hawk have believable motives. And I especially enjoy Wallace Beery's Captain Jasper Leigh, a scoundrel who quickly finds himself in a plot over his head and clings to Sir Oliver for dear life.

Using corsairs as the pirates is a good move too. I usually enjoy the liberty and style of Western pirates more than the structure and uniformity of the Barbary corsairs as presented here, but so many pirate films focus on the Caribbean that The Sea Hawk is a nice change of pace.

Rating: Four out of five English dogs.

Published on July 11, 2014 04:00

July 9, 2014

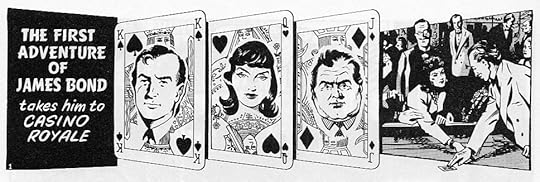

"Casino Royale": The Comic Strip

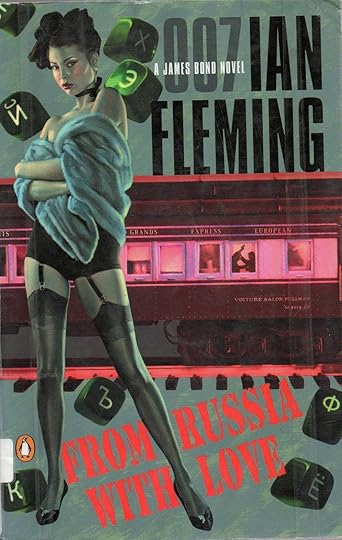

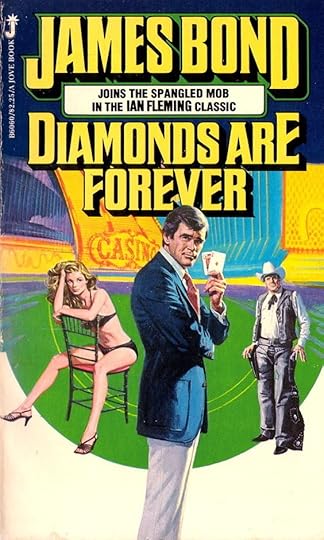

Around the time that From Russia with Love was published, the British Daily Express newspaper contacted Ian Fleming about adapting the novels into comic strip form. They already had a relationship with Fleming from serializing Diamonds Are Forever in the paper and were going to do the same thing with From Russia with Love. Based on that experience, they were confident that a comics version would be a hit.

Fleming was skeptical though. He was afraid that the strips would dumb down a series that he already thought was fairly low brow and that he might be tempted to then let the quality drop even further until he and the strips were speeding each other faster and faster down the drain. Always eager to see Bond reach a wider audience though, Fleming ultimately relented and the first strip, an adaptation of Casino Royale, was published shortly after the novel Dr No.

Adapted by the same guy who'd edited Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia with Love for serialization in the paper, the Casino Royale strip is - as Fleming predicted - a toned down version of the story. It gives up the novel's cold-open-and-flashbacks narrative structure in favor of a straightforward approach (even introducing Vesper to Bond in London before the mission officially begins) and some of the violence is reduced. For instance, Bond's famous last line is changed to simply, "She's dead." Another major example is the torture sequence, where Bond is naked and Le Chiffre is using a carpet beater, but the art strongly implies that Le Chiffre is using it on Bond's head.

For all that though, the strip is remarkably faithful to Fleming's story. It matches the plot beat for beat and it's cool to see artist John McLusky interpret the characters. Bond looks just how Fleming describes him, complete with the scar on his right eye and his black comma of hair. Vesper is tall and lovely and reminds me of a slightly arrogant Audrey Hepburn. Mathis is older and dumpier than I imagine him, but it's a fair interpretation. Felix isn't as handsome as I want him to be either, but I get the hayseed approach that McLusky's going for. Moneypenny doesn't show up in the strip, but M does and it's cool that McLusky keeps Bond's boss in perpetual shadow. That might get annoying as the strip continues - especially in Moonraker - but for now it's a justifiable choice. The one design that doesn't work is the SMERSH assassin who saves Bond's life. He not only wears a ridiculous mask, but he's got a sad-sack look that's even less intimidating.

The main weakness of McLusky's though is that he has a difficult time with facial expressions. This is a big problem for Vesper, who's supposed to be hysterical at times, but none of the characters have a wide range.

Still, McClusky brings the story to life with lifelike representations not only of the characters, but the world around them. From architecture to clothing and cars, the strip puts the story in an historically accurate setting that pulled me into it all over again. Whatever Fleming's reservations, that makes it worthwhile as a companion to the novel.

Published on July 09, 2014 04:00

July 7, 2014

Dr No by Ian Fleming

When I wrote about From Russia with Love, I repeated the common myth that Ian Fleming was growing tired of the Bond series by then and wanted to kill off his main character. Turns out, that's not entirely accurate. Fleming was certainly experimenting when he wrote From Russia with Love, but not out of desperate boredom. He was simply interested in improving the series and was willing to take risks to do so.

When I wrote about From Russia with Love, I repeated the common myth that Ian Fleming was growing tired of the Bond series by then and wanted to kill off his main character. Turns out, that's not entirely accurate. Fleming was certainly experimenting when he wrote From Russia with Love, but not out of desperate boredom. He was simply interested in improving the series and was willing to take risks to do so.Part of the myth of Bond's death is that Raymond Chandler is the one who talked Fleming out of making it permanent. But according to one Bond FAQ, Chandler's advice to Fleming was simply to criticize Diamonds Are Forever (I agree that it's a weak book) and suggest that Fleming could do better. Fleming took that to heart and From Russia with Love was the result. But there's other evidence - also dating back to Diamonds Are Forever - that implies Fleming always intended for Bond to live beyond From Russia with Love.

Shortly after Diamonds Are Forever was published, Fleming received a now-famous letter from a fan named Geoffrey Boothroyd who was also a gun expert. Boothroyd criticized Bond's use of the .25 Beretta as inappropriate and recommended the Walther PPK as a superior choice. Fleming also took this advice to heart, but was already too far into writing From Russia with Love to make the change for that book, so he replied to Boothroyd that he'd include that idea in the next one, which turned out to be Dr No. Apparently, the intention was never to leave Bond dead after From Russia with Love, but simply to end on a cliffhanger and get readers buzzing for the next installment. The myth could be the result of people getting Fleming confused with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who did grow tired of Sherlock Holmes and killed him off before later changing his mind.

As Dr No opens, Bond is still recuperating from Rosa Klebb's poison and M is nervous about sending 007 back into action. He discusses the agent's shelf life with the neurologist who's been watching over Bond's recovery and we get some insight to M's thoughts on pain in general and how much he expects his agents to be able to take. He doesn't want to coddle Bond and risk softening him up, but M is also aware that Bond's been through a rough time and doesn't need to be thrown up against another threat like SMERSH right away. Instead, M has a gravy assignment in mind for Bond; what M calls a "holiday in the sun."

Before we get into the mission, Fleming throws a little world-building into this section of the book. He finally uses the term "license to kill" in reference to the Double O privilege and he also reveals that Bond's best friend in the Service is M's Chief of Staff. I'm not sure what "best friend" means exactly in this context, because we've never seen Bond and the CoS hanging out, so maybe he's just the person who Bond feels the most camaraderie with at work. Bond doesn't seem like the kind of guy to have close friends.

The most famous bit of world-building in Dr No of course is the introduction of the Walther PPK, keeping Fleming's promise to Boothroyd. What's more, he names the armorer after Boothroyd and has the character repeat the fan's comments to M. Bond has to trade in his familiar Beretta for the gun that will become his trademark. As far as I remember, that's the last appearance of Boothroyd in the novels, but the films will make more of him.

Once Bond's outfitted, M reveals the cake-walk mission he has in mind. Strangways, the eye-patched agent stationed in Jamaica whom Bond worked with in Live and Let Die has gone missing with his secretary. Everyone - including M - believes the two of them ran off together, so Bond is just supposed to verify that and tie up loose ends.

Of course, the case is much more complicated than that and Bond quickly figures that out as soon as he starts looking into Strangways' most recent investigation. When a couple of attempts are made on Bond's life, he knows he's on the right track and follows his queries to an island called Crab Key and it's enigmatic owner, Dr. Julius No. Bond teams up again with Quarrel - also from Live and Let Die - and fans of the movie will be very familiar with the rest of the plot.

Of course, the case is much more complicated than that and Bond quickly figures that out as soon as he starts looking into Strangways' most recent investigation. When a couple of attempts are made on Bond's life, he knows he's on the right track and follows his queries to an island called Crab Key and it's enigmatic owner, Dr. Julius No. Bond teams up again with Quarrel - also from Live and Let Die - and fans of the movie will be very familiar with the rest of the plot.During all of this, Fleming brings up again a couple of elements that have become recurring features of Bond's world: the "Bond, James Bond" introduction and his preference for martinis that are "shaken, not stirred." This is at least the third novel in which each of those has appeared, so I probably won't mention them again. By the time the movies get started, they're standard aspects of the character.

If Fleming was experimenting in From Russia with Love, he's gone back to a traditional form of storytelling in Dr No. In fact, the narrative structure of Dr No is more straightforward than all the other Bond novels so far except for Diamonds Are Forever. But where Diamonds Are Forever is my least favorite of the series so far, Dr No is nipping at the heels of Casino Royale for my top spot. It's an extremely pulpy book, from it's fantastic attempts on Bond's life to the revelation of its Fu Manchu-inspired villain with his island hideout and wonderfully elaborate death traps.

It also has the same casual racism that permeated the pulps - and the previous Bond novels - but isn't as horrifying as, for instance, what shows up in Live and Let Die and Diamonds Are Forever. Unlike those books, it was easy for me to filter that out of Dr No as I read. As an example, when Dr. No monologues to Bond at the end - another pulpy element that works better in this setting than it did in the more serious From Russia with Love - he says that it's because Bond will appreciate the story more than No's men would. No calls his men "apes," which could be an ugly reference to the African part of their heritage, but I (choose to?) believe that it's a non-racial insult about their education. I might be reinterpreting to make the book more palatable for myself, but my point is that it's possible to do that with Dr No, where it isn't with the explicit and aggressive racism of Live and Let Die and Diamonds Are Forever.

It also has the same casual racism that permeated the pulps - and the previous Bond novels - but isn't as horrifying as, for instance, what shows up in Live and Let Die and Diamonds Are Forever. Unlike those books, it was easy for me to filter that out of Dr No as I read. As an example, when Dr. No monologues to Bond at the end - another pulpy element that works better in this setting than it did in the more serious From Russia with Love - he says that it's because Bond will appreciate the story more than No's men would. No calls his men "apes," which could be an ugly reference to the African part of their heritage, but I (choose to?) believe that it's a non-racial insult about their education. I might be reinterpreting to make the book more palatable for myself, but my point is that it's possible to do that with Dr No, where it isn't with the explicit and aggressive racism of Live and Let Die and Diamonds Are Forever.I'm aware that I'm heaping higher praise on Dr No basically because it's less ambitious than From Russia with Love. It sets a lower bar for itself and then easily clears it, so maybe I'm not being fair. But as much as I love Fleming's willingness to experiment, that's not what I go to the Bond books for. It's possibly a sad comment about me as a reader, but I prefer that Fleming write excellent books in a traditional style than try to transcend the genre and fail. I can appreciate From Russia with Love, but I adore Dr No.

Not that Dr No simply retreads old territory. The Bond series has never been this pulpy before, so that itself is an experiment. More than that though, Fleming does something exciting and important with Bond's character, especially once he meets Honey Rider.

I think I've said before that I've been imagining Daniel Craig as Bond as I've been reading these again, but that's getting increasingly difficult to do and it comes to a head in Dr No. Even back in Casino Royale, I pointed out how weird it would be to have Craig fantasize about erupting from the ocean in a shower of spray for Vesper to see. That's way too romantic for Craig, even though his Bond falls for Vesper as hard as the literary Bond does. The thing is that as dark a character as Fleming's Bond is, Craig's is darker. The literary Bond has some true moments of light-heartedness, like the way he interacts with Quarrel and Dr. Pleydell-Smith in Dr No. When he's alone and in danger, he's as dark as they come. But when he's hanging out with the right people, he has a light sense of humor that shows through. Craig's Bond has a sense of humor, but it's always cold and ironic. The more I read, the more I think Timothy Dalton nailed that balance better than any other actor.

I think I've said before that I've been imagining Daniel Craig as Bond as I've been reading these again, but that's getting increasingly difficult to do and it comes to a head in Dr No. Even back in Casino Royale, I pointed out how weird it would be to have Craig fantasize about erupting from the ocean in a shower of spray for Vesper to see. That's way too romantic for Craig, even though his Bond falls for Vesper as hard as the literary Bond does. The thing is that as dark a character as Fleming's Bond is, Craig's is darker. The literary Bond has some true moments of light-heartedness, like the way he interacts with Quarrel and Dr. Pleydell-Smith in Dr No. When he's alone and in danger, he's as dark as they come. But when he's hanging out with the right people, he has a light sense of humor that shows through. Craig's Bond has a sense of humor, but it's always cold and ironic. The more I read, the more I think Timothy Dalton nailed that balance better than any other actor.Craig's Bond also wouldn't be as gentle with Honey Rider as Bond is in the novel. When she's introduced, Honey is a wild child; an example of the noble savage stereotype. She's been living on her own for years, surrounded by nature and animals. The little experience she's had with civilization hasn't been pleasant, so she's mostly avoided people until circumstances throw her together with Bond and Quarrel on the island.

Bond is instinctively protective of her. She's 20 (I kept imagining Saoirse Ronan in the role, but that's not perfect casting) and he's pushing 40, so one might be forgiven for expecting him to feel paternalistic towards her, but that would be prudish and unrealistic. The literary Bond isn't as bad as Roger Moore's version, but he's still highly sexual and a womanizer and he quickly decides that the very hot Miss Rider is a grown enough woman to allow himself some romantic thoughts about her. Especially since she makes no effort to hide that she's having the same thoughts about him.

But she's such an innocent that I kept wondering how much of a woman she really is. Her relationship with Bond is almost like a devoted pet at first and I think there's an interesting, if uncomfortable comparison to be made to Ulysse and Nova in Pierre Boulle's Planet of the Apes or Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid in that movie. It's great that Honey's innocent loyalty brings out an intensely protective side of Bond, but how able is she to know what's going on if the relationship becomes sexual? Would he be taking advantage of her? Fleming leaves that question unanswered for quite a while.

But she's such an innocent that I kept wondering how much of a woman she really is. Her relationship with Bond is almost like a devoted pet at first and I think there's an interesting, if uncomfortable comparison to be made to Ulysse and Nova in Pierre Boulle's Planet of the Apes or Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid in that movie. It's great that Honey's innocent loyalty brings out an intensely protective side of Bond, but how able is she to know what's going on if the relationship becomes sexual? Would he be taking advantage of her? Fleming leaves that question unanswered for quite a while.But he does get around to answering it in a marvelous way. As the novel progresses and the danger increases, Honey reveals herself to not be so helplessly innocent after all. For starters, she tells Bond a story (repeated in the movie) about taking revenge on a man who raped her as a kid. It's not using rape as an origin story, but it does show that she has agency in taking care of herself and always has. That doesn't change on Crab Key either. Unlike in the movie, she rescues herself from Dr. No's clutches, using her own knowledge and wits and strength. When Ursula Andress tells Sean Connery that she knows lots of things he doesn't, my response is "yeah yeah sure sure." It sounds like childish bragging to me and the movie never provides a reason to think otherwise. The literary Honey on the other hand, proves her claim to be true.

Fleming awesomely puts to rest my fears about Honey's being more pet than consenting adult, which does wonderful things for Bond's character. He feels protective of her, not like you would a favorite dog, but as a human being who proves herself again and again to be capable of protecting herself. In other words, she pulls him out of the selfishness that's defined his relationships with women since Casino Royale and before.

Though they do eventually have sex, it's not until the end of the book (after the last sentence, actually) and it's entirely on Honey's initiative. Bond wants it too, naturally, but she plans it, pushes for it, and makes it happen.

And as the novel ends, Bond has committed to helping Honey enter society in a way that offers him no reward. He's not leaving his job for her, but even that doesn't feel selfish. It's as if he knows he'd be bad for her and he wants nothing bad for her. He's going to provide what financial support he can to get her set up in a life that will bring her happiness, and he makes sure that she has continued support in the form of Pleydell-Smith and his wife (both of whom I adore). After that, he's going to leave her alone and not ruin things for her. It's an amazing act of conditionless love and I didn't think him capable of it.

And as the novel ends, Bond has committed to helping Honey enter society in a way that offers him no reward. He's not leaving his job for her, but even that doesn't feel selfish. It's as if he knows he'd be bad for her and he wants nothing bad for her. He's going to provide what financial support he can to get her set up in a life that will bring her happiness, and he makes sure that she has continued support in the form of Pleydell-Smith and his wife (both of whom I adore). After that, he's going to leave her alone and not ruin things for her. It's an amazing act of conditionless love and I didn't think him capable of it.But Bond is changing. Fleming shows it with Honey, but he also shows it as Bond thinks back over the case and the deaths it brought. He wonders where Dr. No's soul would go. "Had it been a bad soul or just a mad one?" Then he thinks about Quarrel:

"He remembered the soft ways of the big body, the innocence in the grey, horizon-seeking eyes, the simple lusts and desires, the reverence for superstitions and instincts, the childish faults, the loyalty and even love that Quarrel had given him - the warmth, there was only one word for it, of the man."Bond decides that a man like Quarrel can't have ended up in the same place as a man like No. Bond's job and perception of the world makes it tough to think in terms of good and evil - especially since Casino Royale - so he thinks in terms of warmth and cold. Quarrel was warm; No was cold. And which, Bond wonders, is he?

That remains to be seen, but I love where he seems to be headed.

Published on July 07, 2014 04:00

July 2, 2014

Monster Island (2004)

Who’s In It: Carmen Electra (Aerobic Striptease), Mary Elizabeth Winstead (Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, The Thing), and Adam West (Batman)

What It’s About: A high school senior wins an MTV party for his class with Carmen Electra on a tropical island, but discovers the hard way that the island is crawling with giant insects and piranha people.

How It Is: Awful. And yet amazing.

Look, it’s a Carmen Electra vehicle and on the DVD cover she gets top billing with Nick Carter, who’s barely in the movie, so you know who the target audience is. Also, there are MTV VJs playing themselves. This movie shouldn’t work at all and for the first third, it really doesn’t. The main character (Daniel Letterle) is a sulky dude named Josh who’s just lost his girlfriend Maddy (Winstead) because she wants to be with someone who's interested in the world and has some purpose to his life. Letterie’s performance is as uninspired as his character, but maybe that’s what he’s going for. Either way, I didn’t care about Josh and quickly found myself hoping he’d connect with Carmen Electra so that he’d leave poor Maddy alone.

That wish is granted when Josh meets Carmen and bonds with her over Radiohead and the Ramones, but Maddy may not actually want Josh to leave her alone. Even though she’s already got a new, superboyfriend (who of course turns out to be a prick, but we only know that at this point because we’ve seen a high school movie before), she shows signs of jealousy over Josh’s new interest in Carmen. I was not willing to sit through an hour and a half of this, especially if it was going to stop every once in a while for Carmen to sing songs like the soul-crushingly insipid “Jungle Fever.”

The only thing that kept me going was knowing that Adam West was going to show up at some point as a character named Dr. Harryhausen. The set up might be all wrong, but I had a feeling that the movie’s heart was in the right place. And I was right.

When Carmen is abducted onstage by a giant, winged ant, Josh puts together some friends and MTV employees to go rescue her. That leads into the last two-thirds of the movie, in which Carmen’s presence is replaced by lots of great creatures: mostly giant insects and arachnids, but also a piranha man and a weird fungus-creature invented by the kindly, but probably nuts Dr. Harryhausen. None of the creatures are CGI; they’re all practical effects whether life-size models or stop-motion animation. So while the movie has the cheesy look of the Land of the Lost TV series, it also has the look that someone poured a lot of love into it.

Making it even more awesome is Maddy’s finding a mystic necklace that turns her into some kind of butt-kicking deity. The romantic plot between her and Josh never rises above the usual tropes, but the longer the movie runs, the less time it spends on that anyway. It’s a goofy film, but a lot of fun and way better than it sets out to be.

Rating: Four out of five teenage warrior goddesses.

Published on July 02, 2014 04:00

July 1, 2014

The Poseidon Adventure (2005)

Who's In It: Adam Baldwin (Firefly, Chuck), Rutger Hauer (Bladerunner, The Hitcher), Steve Guttenberg (Police Academy), C Thomas Howell (Red Dawn, The Hitcher), and Alex Kingston (Doctor Who)

What It’s About: Terrorist activity flips over an ocean liner, forcing passengers to make their way up towards the former bottom of the ship where they hope to find rescue.

How It Is: As much as I liked the original Poseidon Adventure, I don’t think that remaking it into a three-hour miniseries is necessarily a doomed proposition. Making the disaster the result of terrorism is a valid way to update the plot and while the original didn’t need more pre-disaster time with its characters, I imagine that there’s a way to do that without hurting the overall story. It’s just too bad that Hallmark/NBC didn’t figure out what that was.

I haven’t read the novel that the original was based on, so I don’t know how much of Hallmark’s version is a new adaptation of the book and how much is a remake of the earlier film. There are a few characters and set pieces that are the same in both movies, but that doesn’t tell me anything. I’m going to refer to it as a remake, but that may or may not be accurate, depending on how you define it. But wherever you come down on that, the 2005 version is sadly a shadow of the 1972 one.

The characters are an easy way to compare the two. A priest still acts as one of the leaders of the escape group, but instead of Gene Hackman’s unorthodox minister to the strong, Rutger Hauer’s character is written as a conventional, if surprisingly actiony clergyman. Hauer does an excellent job with the role and there are moments that remind me of the emotional depth of his work in Bladerunner, so it’s not a bad character by any means. He’s just not written as provocatively as Hackman’s version.

Another example is the pair of unaccompanied minors from the original. In 2005, they’re very much accompanied by bickering parents who have scheduled the cruise as part of marriage therapy. When Mom (soap star Alexa Hamilton) turns the voyage into a working trip, Dad (Guttenberg) retaliates by having an affair with the ship’s unbelievably forward massage therapist (Nathalie Boltt from Doomsday and District 9). In the original, there’s a great dynamic between the kids as they try to take care of each other, but the miniseries turns their story into a tired drama about an affair.

The miniseries almost finds a way to give that plot life by having Guttenberg and Boltt’s characters in bed when the disaster strikes, so that they have to travel together to find Guttenberg’s family. There’s some great awkwardness in that situation and it ramps up even more once they find the family and everyone has to figure out what to do now that they’re forced to survive together. Unfortunately, all that tension is let off earlier than I wanted when one of the members of the triangle conveniently dies.

Deaths are a problem in the miniseries. Where the deaths in the ’72 version all felt random and real, too many in ’05 feel like they’re just tying up plot threads. I won’t spoil anything by mentioning specific examples, but in spite of the extra time we get with these characters, their lives feel cheaper in the miniseries.

The worst thing the remake does to one of the original characters concerns the purser who encourages passengers to stay in the ballroom and wait for rescue. In ’72, he’s well-meaning, but misguided, and there’s believable tension as people have to make the choice between the ballroom and venturing into unknown territory with Gene Hackman. The miniseries removes all ambiguity about that decision though. The purser doesn’t just have an obnoxious personality, he’s a bona fide villain who’s been stealing painkillers from the ship’s doctor and is now hoarding them from injured people while stridently insisting on being in charge. He’s a ridiculous, moustache twirling cartoon of a character.

One character that actually improves in the remake though is Adam Baldwin’s Mike Rogo (played in ’72 by Ernest Borgnine). Instead of a cop, he’s a sea marshal who’s directly responsible for the safety of the passengers and crew. The miniseries goes too far by piling an offscreen, troubled marriage onto him in addition to his immediate problems, but Baldwin’s great as the glowering authority figure, especially when he’s playing against Hauer’s more gentle leadership.

As long as I’m mentioning Hauer again, the miniseries’ biggest crime is putting him in the same movie with C Thomas Howell (who plays the ship’s doctor) and never allowing them to revisit their chemistry from The Hitcher. I fantasized about some kind of cheesy acknowledgment between their two characters, but I would’ve been thrilled with just a meaningful scene featuring them. They barely interact at all.

Other than the characters, the miniseries’ biggest problem is trying to fill time with an outside rescue mission. The ’72 film kept a lot of tension by leaving the characters in the dark about whether or not there actually was rescue for them if they made it to their destination. The ’05 miniseries shows every step of that operation. But I don’t miss that extra tension as much as I just resent being pulled away from the main action to watch people in control rooms talk about how they’re trying to get a SEAL team to the Poseidon before it goes under.

It helps that one of the main coordinators of the rescue is Alex Kingston, but her character is as frustrating as she is fun to watch. As the miniseries ends and everyone is celebrating the rescue of the survivors, she can’t participate because she’s too upset over the thousands who weren’t saved. That’s a valid thing to be distressed about, but it’s also a weird, anticlimactic moment when she’s completely unappreciative of the very thing the rest of the story has been about: the survival of this small group of people. Because the story has been so distracted with easy villains and plot-ordained deaths, it hasn’t spent enough time representing the human tragedy that should have permeated the entire story. So it tacks this on at the end as a sloppy reminder.

Rating: Two out of five Father Battys.

Published on July 01, 2014 04:00

June 30, 2014

From Russia With Love by Ian Fleming

Major SPOILERS BELOW for the novel From Russia With Love.

Major SPOILERS BELOW for the novel From Russia With Love.I’m confused about how much time has passed between Moonraker and From Russia With Love. That’s a weird problem to have, I know, because it doesn’t matter in the grand scheme, but Fleming is so specific about it and his dates don’t match up. At the end of Moonraker, M says he’s sending Bond away for a month until the heat blows over, and Bond decides he’s going to France. Then, as Diamonds Are Forever opens, Bond says that he’s only been back from France for two weeks. But in From Russia With Love, the Soviets discuss Bond’s recent career and date Diamonds as “last year” and Moonraker as three years ago.

The obvious answer is that Fleming simply forgot that he’d placed Diamonds so close to Moonraker. He said at the beginning of Moonraker that typically Bond has only one or two big, dangerous cases a year – and of course the novels were being published once a year – so that’s probably what Fleming was thinking as he wrote Russia. That’s not very satisfying, so my own No-Prize theory is that the France trip mentioned in Diamonds isn’t actually the same as the one at the end of Moonraker. Fleming obviously intended them to be, but if we say they aren’t, then those adventures can be a year apart and we’re back on track again.

The timeline isn’t the only problem the Soviets cause in From Russia With Love. The biggest one sadly isn’t their plans for Bond, but how much of the novel they take over. Stephen King is famous for dedicating pages and pages of background to minor characters, but Fleming did it first. Every contributor to the Soviets’ plan gets at least a paragraph of personal history and most of them a page or two. Red Grant the assassin gets multiple chapters. If I was reading the series a book per year as they were released, this wouldn’t be that big a problem. I might still have been a little put out, but I could perhaps admire the risk Fleming took more than I do now. Marathoning a book a week, I want to keep moving and I had a hard time slogging through the first half of Russia before Bond shows up.

There are some interesting tidbits in the Soviet chapters though. As they discuss and scheme, Fleming reveals that René Mathis from Casino Royale is now the head of France’s Deuxième Bureau. He also adds some further explanation of Bond’s Double O number. After I speculated during Diamonds about the limits of Bond’s license to kill, Snell of the awesome Slay, Monstrobot of the Deep blog (who’s reviewed the Bond films on a separate, equally awesome blog called

I Expect You to Die

) offered that Bond’s hesitation about killing Hugo Drax in cold blood may have been about murdering an English citizen on English soil, especially when Bond didn’t have official jurisdiction, but was being allowed the courtesy to investigate because of a technicality. That matches up with something the Soviets say in Diamonds, which is that the Double O signifies an agent who has killed and is privileged to kill “on active service.” That last criteria is probably obvious, but it’s also very important and it’s arguable that Bond wasn’t on official, active duty in the Moonraker case. Or that he at least had reason not to think of it that way.

There are some interesting tidbits in the Soviet chapters though. As they discuss and scheme, Fleming reveals that René Mathis from Casino Royale is now the head of France’s Deuxième Bureau. He also adds some further explanation of Bond’s Double O number. After I speculated during Diamonds about the limits of Bond’s license to kill, Snell of the awesome Slay, Monstrobot of the Deep blog (who’s reviewed the Bond films on a separate, equally awesome blog called

I Expect You to Die

) offered that Bond’s hesitation about killing Hugo Drax in cold blood may have been about murdering an English citizen on English soil, especially when Bond didn’t have official jurisdiction, but was being allowed the courtesy to investigate because of a technicality. That matches up with something the Soviets say in Diamonds, which is that the Double O signifies an agent who has killed and is privileged to kill “on active service.” That last criteria is probably obvious, but it’s also very important and it’s arguable that Bond wasn’t on official, active duty in the Moonraker case. Or that he at least had reason not to think of it that way.Speaking of killing in cold blood, when Bond does finally show up in From Russia With Love, he muses at one point that he’s never done that. That directly contradicts something Bond said in Casino Royale though when he told Mathis how he got his Double O number. The first time he ever killed a person was through a window from three hundred yards away. He’d lain in wait for days, had an accomplice, and he describes it to Mathis as nice and clean, with no personal contact. Either he’s lying to Mathis in Casino Royale or he’s lying to himself in From Russia With Love and both are completely implausible. Like the timeline, it’s another example of Fleming’s forgetting details from earlier books. Which isn’t that big a deal, but it’s useful to keep in mind that I’m taking the series much more seriously than he did. He was always a bit self-deprecating about the books when he talked about them, so I’m not even insulting him by saying that.

There’s something else that’s bothering me, though it’s not yet a contradiction. I’m still tracking the origin of Bond’s status as an orphan and Russia complicates that a little when Bond remembers skiing trips he took when he was seventeen. Fleming doesn’t explicitly mention Bond’s parents, but the memories are fond ones and imply that Bond’s teenage years were a good, pleasant time for him. It’s not feeling like Bond’s the damaged orphan that the Craig movies make him out to be, so I’m curious about where that came from.

Meanwhile, the Soviets’ plan in Russia is to strike a powerful blow against the West’s intelligence community. It’s not born of a personal grudge against Bond as in the movie, but from professional necessity. Soviet espionage has suffered some important defeats and they need a win. So they come up with a plan to humiliate and murder a top, Western spy. The public at large may never know the importance of the killing, but the intelligence community will. After much discussion, the Soviets choose England as their target and Bond – thanks to his involvement in the Le Chiffre, Mr. Big, and Moonraker cases – as their victim. Since the Soviet action will be the assassination of a spy, SMERSH is chosen to carry it out.

Meanwhile, the Soviets’ plan in Russia is to strike a powerful blow against the West’s intelligence community. It’s not born of a personal grudge against Bond as in the movie, but from professional necessity. Soviet espionage has suffered some important defeats and they need a win. So they come up with a plan to humiliate and murder a top, Western spy. The public at large may never know the importance of the killing, but the intelligence community will. After much discussion, the Soviets choose England as their target and Bond – thanks to his involvement in the Le Chiffre, Mr. Big, and Moonraker cases – as their victim. Since the Soviet action will be the assassination of a spy, SMERSH is chosen to carry it out.The plan is almost exactly what it is in the film except that there’s no SPECTRE pulling everyone’s strings behind the scenes. It’s a SMERSH operation through and through with a decoding machine as the bait to bring Bond to Istanbul. In the film, the machine is called the Lektor, but that’s because it’s the Spektor in the novel and it would have been a bit much to have the device and the criminal organization using the same name. It does go to show Fleming’s like of that word though, including using a Western ghost town called Spectreville as a major location in Diamonds.

Another carryover from Diamonds is Tiffany Case. She doesn’t actually appear in Russia, but her shadow is there, at least at the beginning. Fleming lets us know that she and Bond lived together for several months and were even talking about marriage, but they’ve recently broken up and Case is moving back to the US with her new fiancé. That’s interesting on a couple of levels.

First, Bond specifically mentioned in Diamonds that marriage was off the table for him. That changed at some point, at least to the extent that he was willing to discuss it with her, even if only to keep her happy. I’m sorry Fleming doesn’t go into more detail about that, because I’m way more curious about it than in the life story of Rosa Klebb’s boss, but I don’t imagine that Bond was ever serious about marrying Tiffany. I’m sure he was in love with her and imagine that he wanted to keep her around, but marrying her would mean a drastic career change and there’s no indication that he ever sincerely considered that.

First, Bond specifically mentioned in Diamonds that marriage was off the table for him. That changed at some point, at least to the extent that he was willing to discuss it with her, even if only to keep her happy. I’m sorry Fleming doesn’t go into more detail about that, because I’m way more curious about it than in the life story of Rosa Klebb’s boss, but I don’t imagine that Bond was ever serious about marrying Tiffany. I’m sure he was in love with her and imagine that he wanted to keep her around, but marrying her would mean a drastic career change and there’s no indication that he ever sincerely considered that.The other interesting thing about Tiffany’s engagement to another man is that this is second time in two relationships that that’s happened to Bond. His relationship with Gala Brand was over before it got started because she was already engaged. Now Tiffany has moved on into marriage without him. The implication is that Bond is in a state of arrested development as women pass him by and leave him behind.

It’s a romantic notion to think of Bond’s trouble as stemming from Vesper and her betrayal, but that can’t be it. Casino Royale makes it really clear what a selfish bastard Bond is before he becomes deeply involved with her. His relationship with her was serious – and seriously screwed up – but I don’t believe it scarred him to the point that it sabotaged his future relationships. It’s his selfishness that’s doing that. Or – if we’re being charitable – his dedication to his country.

I’ll come back to Bond’s dedication in a minute, but before we leave the topic of his relationships, we should talk briefly about Tatiana Romanova. Fleming’s description of her has me casting Olga Kurylenko in my head, though Kurylenko’s Camille in Quantum of Solace is a way better character than Tatiana, who apparently decides to betray her mission and defect to England after one night with James Bond. Bond seems to really like her, but there’s no surprise or honor in that. She’s drop dead beautiful and completely committed to him, at first as part of her cover, but quickly for real. There’s no true relationship there and Bond is never sure if he can trust her, not that his lack of trust is ever a hindrance. In the film, there’s at least some lip service paid to whose side Tatiana’s really on, but Fleming isn’t that interested outside of Bond’s wondering about it occasionally.

I’ll come back to Bond’s dedication in a minute, but before we leave the topic of his relationships, we should talk briefly about Tatiana Romanova. Fleming’s description of her has me casting Olga Kurylenko in my head, though Kurylenko’s Camille in Quantum of Solace is a way better character than Tatiana, who apparently decides to betray her mission and defect to England after one night with James Bond. Bond seems to really like her, but there’s no surprise or honor in that. She’s drop dead beautiful and completely committed to him, at first as part of her cover, but quickly for real. There’s no true relationship there and Bond is never sure if he can trust her, not that his lack of trust is ever a hindrance. In the film, there’s at least some lip service paid to whose side Tatiana’s really on, but Fleming isn’t that interested outside of Bond’s wondering about it occasionally.(I guess one more thing about Bond and women and that’s that there’s more flirting with his secretary Lil in Russia. It’s become quite the recurring shtick really and Moneypenny is only kind and friendly to him. Moneypenny is Bond’s boss’ secretary and that’s very much how the relationship feels right now. Bond likes her, but she also represents M’s power and authority in a way that seems to keep their relationship professional.)

So, back to Bond’s dedication and this whole blunt instrument thing I keep talking about. From Russia With Love is more of a spy story than the last two or three Bond novels were. In every book so far since Casino Royale, Bond pretty much knows who the villain is before he ever starts his mission. That makes the blunt instrument approach effective and it’s believable that Bond develops it as a favorite tactic. He just goes in and stirs stuff up until the bad guy makes a mistake. In Russia though, Bond isn’t even sure there is a villain for most of the book. He wonders about it, but the plot’s masterminds are hidden from him until the very end. So the blunt instrument approach is never really an option for him.

That said though, he still thinks about it. One of the things he admires about Kerim Bey, the Secret Service’s top man in Turkey, is that Kerim isn’t secretive about his activities. Kerim does that partly to distract enemies from his actual secret agents, and Bond mentions to M that “the public agent often does better than the man who has to spend a lot of time and energy keeping under cover.” Later in the book, Bond’s getting as impatient with the pace of the novel as I was. After a few chapters of just tagging along on Kerim’s side adventures in Istanbul, Bond acknowledges that he’s feeling ineffective. “I’ve got absolutely nowhere with my main job,” he says. “M will be getting pretty impatient.” That made two of us, but from a less meta perspective it’s a good example of Bond’s need to get in there and do something.

That said though, he still thinks about it. One of the things he admires about Kerim Bey, the Secret Service’s top man in Turkey, is that Kerim isn’t secretive about his activities. Kerim does that partly to distract enemies from his actual secret agents, and Bond mentions to M that “the public agent often does better than the man who has to spend a lot of time and energy keeping under cover.” Later in the book, Bond’s getting as impatient with the pace of the novel as I was. After a few chapters of just tagging along on Kerim’s side adventures in Istanbul, Bond acknowledges that he’s feeling ineffective. “I’ve got absolutely nowhere with my main job,” he says. “M will be getting pretty impatient.” That made two of us, but from a less meta perspective it’s a good example of Bond’s need to get in there and do something.That’s made extremely evident toward the end of the book when Bond figures out that there’s more to this thing than just Tatiana wanting to defect. He has the opportunity to leave the Orient Express and make a safer way home with the girl and the Spektor, but chooses not to. Part of that is that he’s enjoying Tatiana’s company (to put it politely), but he also admits to himself that he simply wants to see the plot through. Yet another example of Bond’s offering meta commentary on the experience of reading From Russia With Love.

Bond’s pointing out his dissatisfaction with the plot could be a suggestion that Fleming himself was growing impatient in writing it. The novel is such a departure structurally that it feels like Fleming is experimenting, perhaps to keep himself interested. He was rather famously dissatisfied with the series at this point, so a lot of Russia feels like he’s trying something new.

Bond’s pointing out his dissatisfaction with the plot could be a suggestion that Fleming himself was growing impatient in writing it. The novel is such a departure structurally that it feels like Fleming is experimenting, perhaps to keep himself interested. He was rather famously dissatisfied with the series at this point, so a lot of Russia feels like he’s trying something new. He’s dramatically increased the number of gadgets, for one thing, though most of them are simply disguised guns. Kerim has a cane gun, Grant has a book gun, and Klebb has a telephone gun (in addition to poisoned knitting needles and her famous shoe knife). Bond doesn’t usually get gadgets in the series, but the movie’s attaché case is right out of the book. Not that Bond was all that hip on it. He mocked Q-Branch for assigning it to him (setting the tone for the film Bond’s relationship with Q), though he comes around late in the story when the case proves extremely useful.

Perhaps another sign that Fleming was growing tired of these stories is the horrible monologue Grant gives to Bond just before trying to kill him. Bond has no other way of finding out who’s behind the Spektor scheme, so Fleming has Grant simply spill all the beans – including naming the leaders of SMERSH and where to find them – because “it’ll give me an extra kick telling the famous Mister Bond of the Secret Service what a bloody fool he is.”

Of course, the most obvious example of Fleming’s weariness with Bond is that he kills the character at the end. He does it in a way that’s reversible in case of a change of heart, but when Klebb uses that poisoned shoe knife at the end, it’s much more effective in the novel than it is in the movie. Bond wraps up the adventure, captures the head of the organization he’s been fighting since the first book, and then falls to the floor dying. Nice and neat.

Of course, the most obvious example of Fleming’s weariness with Bond is that he kills the character at the end. He does it in a way that’s reversible in case of a change of heart, but when Klebb uses that poisoned shoe knife at the end, it’s much more effective in the novel than it is in the movie. Bond wraps up the adventure, captures the head of the organization he’s been fighting since the first book, and then falls to the floor dying. Nice and neat.It’s almost inevitable and perfect. What better, more believable way for Bond to die than at the hands of a dangerous enemy he’s just neutralized? With all of his running headlong into danger, it’s almost the kind of ending I’d imagine he wants for himself.

But something happens earlier in the book that challenges that idea. When he gets the attaché case from Q-Branch, there’s a cyanide pill in it, which Bond immediately flushes down the toilet. He doesn’t just leave it there with a conviction that he’ll never use it; he makes it so that he no longer even has the choice of using it. Bond isn’t afraid of taking immense pain, but he does seem to be afraid to die. Fleming reveals that a couple of times in the series, especially when Bond is flying through bad weather. And that makes Bond a better hero. He’ll sacrifice comfort for his country, but he doesn’t have a death wish. He wants to live, and I’m glad that he does.

Published on June 30, 2014 04:00

June 25, 2014

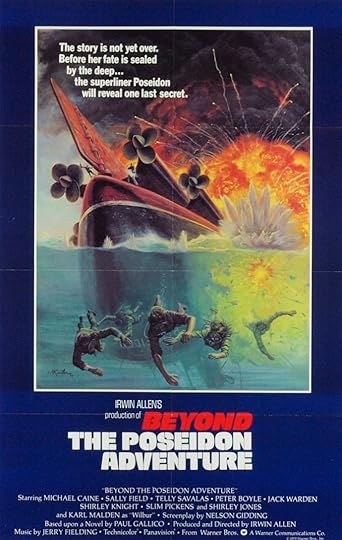

Beyond the Poseidon Adventure (1979)

Who's In It: Michael Caine (Batman Begins), Sally Field (The Amazing Spider-Man), and Telly Savalas (On Her Majesty's Secret Service)

What It's About: The morning after the Poseidon disaster, the broke captain (Caine) of a cargo tug discovers the wreckage and takes his crew (Field and Karl Malden) aboard to look for salvage. At exactly the same time, a wealthy doctor (Savalas) also goes aboard, claiming he wants to assist survivors. But is that really his goal or does he have something more sinister in mind?

How It Is: Once Caine and his crew get into the ship and their entrance route is cut off by shifting debris, there's a lot about Beyond the Poseidon Adventure that's a straight repeat of the first film. You've got the brave, headstrong dude (Caine replacing Gene Hackman) leading a group through the unstable, waterlogged vessel, and it doesn't stay the three of them for long. They collect survivors along the way, increasing the size of their party beyond that of the first movie, but including some of the same tropes. Instead of Ernest Borgnine's grouchy cop, we've got Peter Boyle's (Young Frankenstein) grumpy sergeant. And Jack Warden's (All the President's Men) blind man slows the group down as opposed to Shelley Winter's overweight woman.

But these are superficial similarities and they work (in Warden's case) or don't (in Boyle's) about as well as their counterparts did in the original. There's just enough similarity to make me feel it was worth coming back for more, but lots of difference to make it a new experience.

For one thing, Beyond really focuses on the adventure part of Poseidon Adventure. The original was exciting, but it's strength was the human drama. The sequel is all about action, from the treasure-hunting motives of its lead characters to the mysterious mission of whatever Savalas is really up to. It's not just humans against disaster; it's humans against disaster and other humans.

And they're quite likable humans too. I can take or leave Malden's performance, but Caine and Field are as charming as ever and make a wonderful team. I also got a kick out of the interactions between Boyle and Warden (who played best friends in While You Were Sleeping). Shirley Jones (The Partridge Family) plays a nurse and Mark Harmon (Summer School) is a young man who rescues Boyle's daughter (Angela Cartwright from Lost in Space) and is resented by her father for it.

Meanwhile, Telly Savalas is essentially reprising his role as Blofeld and Beyond could easily be as much a sequel to On Her Majesty's Secret Service as it is to The Poseidon Adventure. It's certainly a better OHMSS sequel than Diamonds Are Forever.

Rating: Four out of five Alfred/Aunt May team-ups.

Published on June 25, 2014 04:00

June 23, 2014

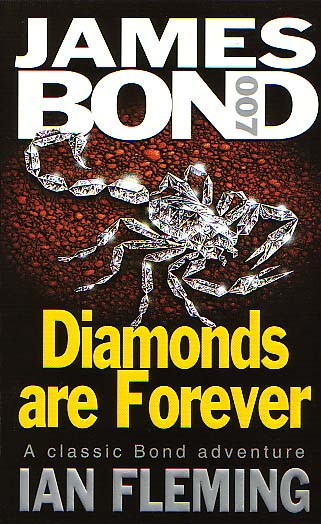

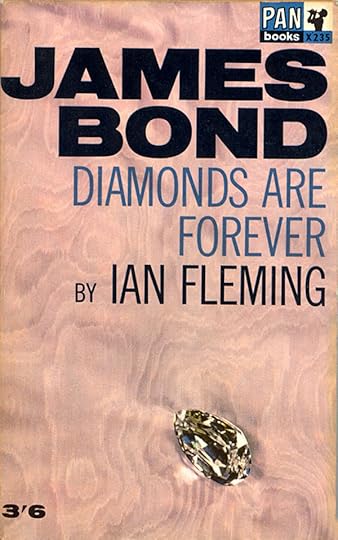

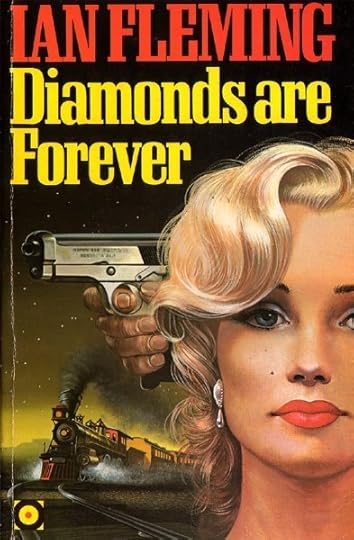

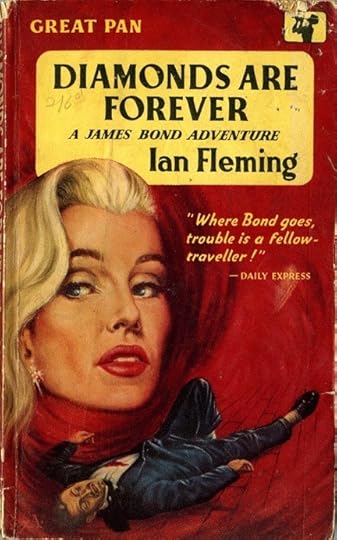

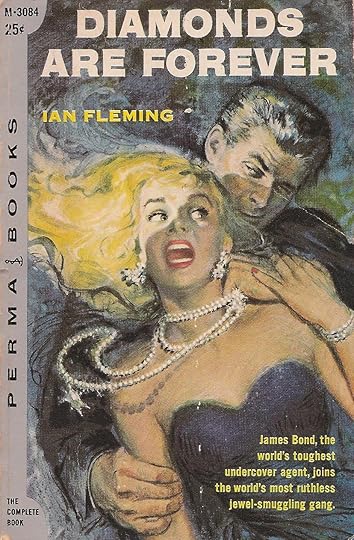

Diamonds Are Forever by Ian Fleming

With three of the Bond novels behind me – four counting this one – I feel like I almost know what I’m doing, so I’m going to try a new format. For one thing, in order for me to stay on target and wrap this project up in eighteen months, I’ve got to read faster, so no more breaking novels into multiple posts.

With three of the Bond novels behind me – four counting this one – I feel like I almost know what I’m doing, so I’m going to try a new format. For one thing, in order for me to stay on target and wrap this project up in eighteen months, I’ve got to read faster, so no more breaking novels into multiple posts.But also, I’ve kind of figured out what themes I want to focus on, so I’m going to try out a standardized structure to see if that keeps me organized. I’ll briefly summarize the plot and any interesting details from Fleming’s life that may have contributed to it, then talk about Bond’s character development in terms of his tactics, psychology, and relationships. Finally, I’ll mention any building that Fleming does of Bond’s world and offer closing thoughts on the book as a whole.

Mission Briefing

Two weeks after the Moonraker affair, M asks Bond to investigate a diamond smuggling pipeline that’s threatening Britain’s control over the world’s diamond markets. Bond’s job is to ascertain the extent of the operation so that it can be shut down. To do this, he replaces an arrested smuggler named Peter Franks and meets Franks’ contact, a woman called Tiffany Case who gives him diamonds to sneak into the United States.

If you’re familiar with the movie version, you can see that it follows the book’s plot for a while. I’ll get into major differences when I cover the movie, but one, small change that’s interesting to point out is the way Bond smuggles the diamonds into the US. In the film, he uses a dead body in a coffin, but in the novel Case asks him about his hobbies and personalizes the smuggling method to him. He tells her he likes to golf (already mentioned in Moonraker), so she rigs some trick golf balls to hide the diamonds in. She even lets him pick his favorite brand: Dunlop 65s, which – if memory serves – comes up again in Goldfinger.

If you’re familiar with the movie version, you can see that it follows the book’s plot for a while. I’ll get into major differences when I cover the movie, but one, small change that’s interesting to point out is the way Bond smuggles the diamonds into the US. In the film, he uses a dead body in a coffin, but in the novel Case asks him about his hobbies and personalizes the smuggling method to him. He tells her he likes to golf (already mentioned in Moonraker), so she rigs some trick golf balls to hide the diamonds in. She even lets him pick his favorite brand: Dunlop 65s, which – if memory serves – comes up again in Goldfinger.A Blunt Instrument

Bond’s learned from the Moonraker case that lack of subtlety has its rewards. In Diamonds Are Forever, it starts innocently enough when he drops the Peter Franks identity at first chance. He tells Case that Franks is just an alias; his real name is James Bond. That becomes kind of a joke in the films when everyone knows who Bond is, but the literary Bond doesn’t have that problem and it makes a kind of sense that he prefers to be called by his real name and so avoid slipping up and forgetting to answer to the fake one. It’s an indicator though that he doesn’t really have patience for true undercover work, which becomes even more obvious as the novel progresses.

The longer Bond stays on the case, the less patience he has with it. He bristles at playing a lackey looking for a job with the Spang brothers, the gangsters who run the smuggling ring. He’s bored with his role and bored with the mob and even bored with their style of gambling. Bond loves to gamble, but when his mission leads him to Las Vegas he finds it cheap and dull (which has probably formed my own opinion of American casinos since this novel was my first exposure to them as a kid). Eventually, he decides to take matters into his own hands.

“The truth of the matter, Bond decided over coffee, was that he felt homesick for his real identity. He shrugged his shoulders. To hell with the Spangs and the hood-ridden town of Las Vegas. He looked at his watch. It was just ten o’clock. He lit a cigarette and got to his feet and walked slowly across the room and out into the Casino.That’s the very definition of the blunt instrument and Bond now seems to have reached a place where he can’t even function any other way. At least not on this assignment. He makes a moderate effort to force the pace in a way that still allows him to maintain his cover, but at that point maintaining cover is a secondary consideration. I’m not going to go so far as say that Bond is a bad spy, but he’s becoming a very particular kind of spy.

“There were two ways of playing the rest of the game, by lying low and waiting for something to happen – or by forcing the pace so that something had to happen.”

That his scheme pays off and leads him to a meeting with the head of the gang presumably only reinforces the effectiveness of this new method of uncovering and defeating bad guys.

“Oh, James!”

“Oh, James!”The literary Tiffany Case isn’t much like the way Jill St John plays her in the film. Both versions are tough cookies, but St John’s is playful. The literary Case has a strong aura of sadness and loneliness around her and I found myself imaging her as Scarlett Johansson, whose voice and appearance exactly matches Fleming’s description.

When Bond meets her in her apartment, she’s listening to a collection of French songs and she lets him control the phonograph while she goes to put on some clothes. As a callback to Casino Royale, he skips “La Vie en Rose” because it has memories for him. Fleming isn’t explicit about it in Diamonds, but that piece was playing during one of Bond’s dinners with Vesper. It’s a lovely detail that puts Bond in the right emotional state for his relationship with Case.

Right away, Bond’s relationship with Case is very different from the ones he had with Solitaire and Gala Brand. He saw Solitaire as an object. She was a prize to be won; a reward for completing his mission. He might have been tempted to think of Brand the same way, but she was too much his equal. He wanted to sleep with her and she was attracted to him, but she was also engaged to someone else and never seriously considered getting involved with Bond. After being hurt so deeply by Vesper, Bond used Solitaire as a rebound girl, while Brand brought him back to reality and made him see that not all women can be thought of as objects.

His relationship with Case is interesting because it’s much deeper than what he had with the previous two women. In many ways, it’s a lot like what he had with Vesper. Case is tough and can take care of herself, so there’s a little Gala Brand in her, but she also has a lot of vulnerability. She’s been on her own and looking out for herself her whole life, but Fleming quickly peels some of that toughness away and reveals that she likes Bond and is a little flustered by him. At first, I was concerned that Fleming was going to have Bond “tame” her, but that’s not where the relationship goes.

His relationship with Case is interesting because it’s much deeper than what he had with the previous two women. In many ways, it’s a lot like what he had with Vesper. Case is tough and can take care of herself, so there’s a little Gala Brand in her, but she also has a lot of vulnerability. She’s been on her own and looking out for herself her whole life, but Fleming quickly peels some of that toughness away and reveals that she likes Bond and is a little flustered by him. At first, I was concerned that Fleming was going to have Bond “tame” her, but that’s not where the relationship goes.Bond genuinely likes her. For one thing, she’s totally his type with her unpainted nails (Fleming mentions that detail a couple of times), but he immediately feels conflicted about how to treat her. He needs to use her to get information about the pipeline, but he desperately wants to avoid hurting her. For her part, she seems just as conflicted; attracted to him even though she believes he’s as much a thug as the other men in her life.

By the end of the novel, Bond admits to himself that he’s “very near to being in love” with her. But as they travel back to London on the Queen Elizabeth and have a chance to interact without the pressures of trying to stay alive, it becomes clear that Bond’s all wrong for her. Case wants out of her dangerous life. She wants to settle down and have a normal relationship, but Bond readily confesses that settled life isn’t for him. Maybe when he retires, but not right now. His job still comes first.

Which is as it should be. He may have genuine feelings for her, but that doesn’t mean that the timing is right or that things will work out for them. By the end of the novel, she’s living at his place until she gets on her feet, but it’s obvious to me that that’s not going to last a long time. He was the right man to get her out of the mob, but the wrong man to be with once that’s done. Diamonds Are Forever shows us a lovely beginning to a doomed relationship.

Which is as it should be. He may have genuine feelings for her, but that doesn’t mean that the timing is right or that things will work out for them. By the end of the novel, she’s living at his place until she gets on her feet, but it’s obvious to me that that’s not going to last a long time. He was the right man to get her out of the mob, but the wrong man to be with once that’s done. Diamonds Are Forever shows us a lovely beginning to a doomed relationship.The World-Building Is Not Enough

Bond’s secretary Lil reappears after her introduction in Moonraker and he flirts with her briefly before heading up to see M. In contrast, his interaction with Moneypenny is limited to a smile into her “warm brown eyes.” I’m still curious to see if things liven up with Moneypenny in the books before the Dr. No movie. Could the Bond/Moneypenny relationship in the films be more inspired by Bond and Lil?

Vallance from Scotland Yard is also back from Moonraker, though there’s no mention of Gala Brand. Bond’s obviously over her, though that was never in question.

Felix Leiter shows up by complete coincidence. After his tragic injuries in Live and Let Die, he’s now disabled with a prosthetic leg and a hook for a hand. He’s out of the CIA and is working for the Pinkerton detective agency, investigating a different angle of the diamond smuggling case. I couldn’t be too frustrated with the coincidence though, because Felix is such a charming character and I loved his buoyancy even after losing his limbs and his job.

Casino Royale revealed that Bond’s favorite drink is shaken with ice to make it cold, but it’s in Diamonds Are Forever that the famous “shaken, not stirred” instruction makes its first appearance. Bond’s on a date with Case and that’s how he instructs the waiter to make their Martinis.

Casino Royale revealed that Bond’s favorite drink is shaken with ice to make it cold, but it’s in Diamonds Are Forever that the famous “shaken, not stirred” instruction makes its first appearance. Bond’s on a date with Case and that’s how he instructs the waiter to make their Martinis.When Bond learns that he’s going to be playing blackjack as part of his cover, he remembers playing that as a kid at childhood parties. Bond’s status as an orphan has become well-known in the Daniel Craig movies, but there’s no hint of that yet in the novels and the image of Bond’s parents taking him to playroom tea parties was a surprising one, even though Skyfall indicates that its version of Bond wasn’t super young when they died. I’m curious to see where the orphan idea makes its appearance.

I’m still trying to figure out the limitations of Bond’s license to kill (though that term hasn’t come up yet in the novels). In Live and Let Die, Mr. Big suggested that Bond’s a government assassin, which is more or less a license to kill, but only in situations when specifically ordered to do so. In Moonraker, Bond muses that he can’t just kill Hugo Drax without risking hanging for the crime, so clearly there are limits, even though Bond racks up quite the body count in Live and Let Die without any consequences. Diamonds Are Forever has Felix ask Bond if he’s “still got that double O number that means you’re allowed to kill” and Bond affirms that he does. That’s pretty much the license to kill idea right there without actually coining the term and it makes sense. Bond’s not just an assassin; he’s got a lot of liberty when it comes to killing people in the line of duty. But as Moonraker points out, there are limits. One of which apparently is bumping off wealthy industrialists/public heroes just because you think they might be up to something.

One of Bond’s allies in Las Vegas notices that two of the Spang’s thugs are from Detroit; part of the Purple Mob. If memory serves, that’s another element that pops up again in Goldfinger.

One of Bond’s allies in Las Vegas notices that two of the Spang’s thugs are from Detroit; part of the Purple Mob. If memory serves, that’s another element that pops up again in Goldfinger.Any Last Words, Mr. Bond?

Diamonds Are Forever is fun to read as an American, because it’s set in such familiar territory, but it’s a deeply flawed book. One of Fleming’s major goals in it is to make American gangsters appear to be formidable villains, but he goes about it all wrong. He starts off strongly enough by showing that M has as much concern about the mob as he does for SMERSH or any other foreign power, but Fleming’s love of goofy names works against this. You don’t see many Soviet assassins named “Shady” Tree or “Tingaling” Bell, even in Bond novels. Fleming probably thought he was safe in the tradition of Baby Face Nelson and Machine Gun Kelly, but his gangster nicknames are so cutesy that it’s tough to take these mugs seriously.

Their own men don’t take them that seriously either. When Felix blackmails a jockey into throwing a crooked horse race, there’s no sense that the jockey is all that concerned about what’ll happen when he does. He seems practically eager to betray his bosses, which nicely lets Felix off the hook for the consequences, but doesn’t make the mob seem as scary as M claimed they are. In fact, no one in the novel seems to take the mob as seriously as everyone says they should. When the jockey does throw the race, the mob only sends its goons to wound him. It’s in a dramatic, pretty horrible way, but it’s hard to imagine gangsters from The Godfather or Goodfellas stopping there when the jockey’s screwed up an expensive, long-term plan.

That’s the real problem I had with Diamonds Are Forever: that it doesn’t hold up at all next to modern stories about the ruthlessness and cruelty of the mafia. Then again, it doesn’t hold up next to Live and Let Die either. Mr. Big’s organization felt infinitely larger and stronger than the Spang Brothers’ almost adorably tiny operation. Counting Bond and Case, there are nine people in the entire outfit and as much as he says otherwise, Fleming doesn’t really think they’re all that threatening either.

That’s the real problem I had with Diamonds Are Forever: that it doesn’t hold up at all next to modern stories about the ruthlessness and cruelty of the mafia. Then again, it doesn’t hold up next to Live and Let Die either. Mr. Big’s organization felt infinitely larger and stronger than the Spang Brothers’ almost adorably tiny operation. Counting Bond and Case, there are nine people in the entire outfit and as much as he says otherwise, Fleming doesn’t really think they’re all that threatening either. He apparently did some research on the mob by talking to a captain in the Los Angeles Police Department, but he’s filled his fictional version with so much color that their unnecessarily elaborate payoff system feels stupid and ridiculous. Instead of simply paying Bond his $5,000 for smuggling the diamonds, they give him $1,000 and make him pretend to earn the rest in crooked gambling schemes that require him to travel first to Saratoga Springs for the horse race and when that fails to Las Vegas for the casinos. This is supposed to cover the fact that he’s being paid by them, but they’re taking care of his air travel and hotel expenses, so any competent investigation would see right through that.