Michael May's Blog, page 158

August 13, 2014

Octopussy and The Living Daylights | "007 in New York"

Though James Bond had a long relationship with the Daily Express, Ian Fleming had an even longer one with rival newspaper the Sunday Times. I've already mentioned how "The Living Daylights" was first published in the Times and how that affected the Express' Bond comic strip, but Fleming went back with the Sunday Times a long way. After Fleming left military intelligence in 1945, he became the Foreign Manager of the group that owned the Times, overseeing their global network of correspondents. He quit his full time gig with the paper in '59, but continued writing articles for them. That's where "007 in New York" has its origins.

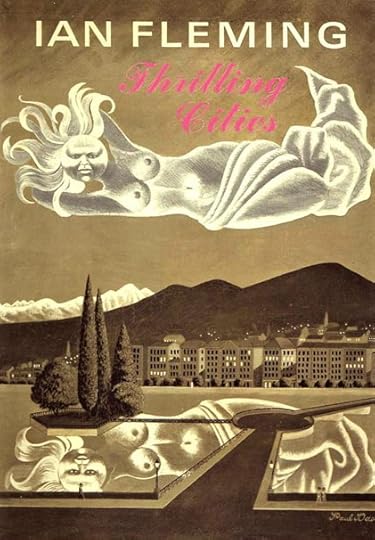

Though James Bond had a long relationship with the Daily Express, Ian Fleming had an even longer one with rival newspaper the Sunday Times. I've already mentioned how "The Living Daylights" was first published in the Times and how that affected the Express' Bond comic strip, but Fleming went back with the Sunday Times a long way. After Fleming left military intelligence in 1945, he became the Foreign Manager of the group that owned the Times, overseeing their global network of correspondents. He quit his full time gig with the paper in '59, but continued writing articles for them. That's where "007 in New York" has its origins.It was also in '59 that the Times' features editor offered Fleming a five-week, all-expenses-paid trip around the world as fodder for a series of travel articles. Fleming didn't think he'd be good at it and was resistant at first, but changed his mind when he realized he could use the experience as material for Bond. The series ran in the first months of 1960 and was then collected into a book called Thrilling Cities.

Sadly, Fleming had become tired and cranky towards the end of the tour and that was reflected in the tone of his article on New York City (though he's very up front in the essay about that being the case). When Thrilling Cities was looked at for publication in the US, publishers there asked Fleming if he could rework the article to be less scathing, but he refused. In order to balance out his negative article though, he included in the US edition a piece that he'd had published in the New York Herald Tribune the year before. The original title of the article was "Agent 007 in New York," but that was shortened for Thrilling Cities to just "007 in New York".

About the story's inclusion, Fleming wrote, "By way of a postscript I might say I am well aware these grim feelings I’ve expressed for New York may shock or depress some of my readers. In fact, I would be disappointed if this were not the case. In deference to these readers, I here submit the record of another visitor to the city, a friend of mine with the dull name of James Bond, whose tastes and responses are not always my own and whose recent minor adventure in New York (his profession is a rather odd one) may prove more cheerful in the reading."

In keeping with the travelogue tone of the other essays, "007 in New York" is mostly just Bond's musing on the city as he's being driven to his hotel from the airport. Fleming mentions a mission having to do with Bond's telling a former Secret Service agent (who also happens to be a past lover) that her new boyfriend works for the KGB. We get none of that conversation except for a couple of final, unexpectedly funny sentences at the end, because it's not the purpose of the piece. The article is simply to entertain and to tell readers how to make awesome scrambled eggs. It does those both very well.

Published on August 13, 2014 04:00

August 12, 2014

Octopussy and The Living Daylights | "The Property of a Lady"

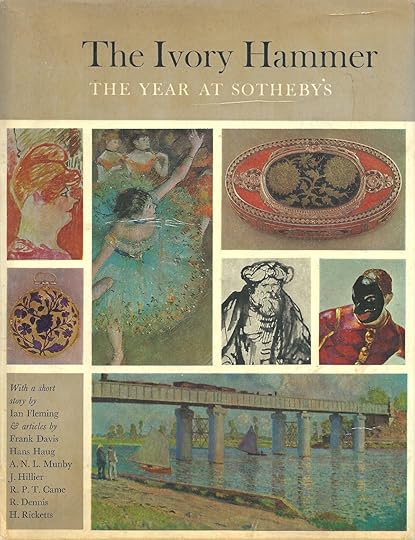

In 1963, English auction house Sotheby's commissioned Fleming to write a short story for their annual journal, The Ivory Hammer. The result was "The Property of a Lady," with Bond attending a Sotheby's auction for a Fabergé egg. The egg was sent by the Soviets as payment to a known double agent in MI6, so Bond suspects that the woman's KGB contact in London will be present at the auction to help drive up the price. Bond's job is identify this contact so that he can later be deported, throwing a kink in the Soviets' activities in Britain.

In 1963, English auction house Sotheby's commissioned Fleming to write a short story for their annual journal, The Ivory Hammer. The result was "The Property of a Lady," with Bond attending a Sotheby's auction for a Fabergé egg. The egg was sent by the Soviets as payment to a known double agent in MI6, so Bond suspects that the woman's KGB contact in London will be present at the auction to help drive up the price. Bond's job is identify this contact so that he can later be deported, throwing a kink in the Soviets' activities in Britain.It's no surprise that a writer who makes card games and golf sound exciting can do the same thing for a jewelry auction, so there's nothing wrong with the build up and tension in the story. But "The Property of a Lady" doesn't hold together logically super well. Why exactly is the KGB contact risking exposure when the egg will fetch a very nice price without his interference? It seems unnecessarily greedy, especially on behalf of a double agent who's conceivably doing her job out of patriotism. Fleming kind of fumbles the ending too. All the drama is in the auction scene, but once Bond identifies his target, there's nothing else to keep me interested and it feels like Fleming knows it. He agreed that "The Property of a Lady" wasn't great work and reportedly refused payment for it. A couple of decades later though, the major elements of the story found their way into the movie Octopussy, which did a better job of building a compelling story around the idea.

There's not any character development for Bond in the story, but a couple of important characters do show up. Ronald Vallance of Scotland Yard reappears after his introduction in Moonraker and also contributing to Bond's work in Diamonds Are Forever and "Risico." He's mentioned as Sir Ronald Vallance in this story, which I think is new, so congratulations to him on that.

The other major character is Mary Goodnight. This isn't her true introduction to the series, but since I'm reading stories in the order of Bond's experience and not in the order that Fleming wrote them, it's the first time she's showing up for me. She's the new secretary in the Double-O section, replacing Lil, and it's tough to get a handle on her from just this story. Presumably she gets a better introduction in On Her Majesty's Secret Service, her true first appearance. In "The Property of a Lady" though, I missed Lil and it feels like Bond does too, though he doesn't mention her. He seems to think Goodnight is hot, but he doesn't flirt with her and doesn't even seem to respect or like her. Fleming does specifically mention that Bond's already in a bad mood about something else though, so maybe I shouldn't read much into that. Look forward to getting to know her better in OHMSS, because she becomes a major player in Bond's life in the last Fleming novels.

Published on August 12, 2014 04:00

August 11, 2014

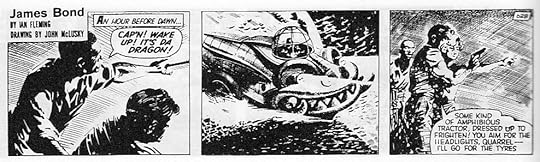

Octopussy and The Living Daylights | "The Living Daylights"

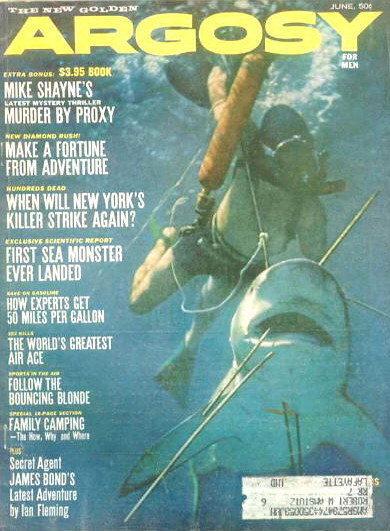

"The Living Daylights" was first published in 1962 as part of a color supplement for The Sunday Times. The Times was a rival to the Daily Express, which had been serializing and adapting Bond stories for about six years by that point, so the Express was naturally upset. In fact, "The Living Daylights" created a big rift between Fleming and the Express to the point that the Bond strip was abruptly ended part way through the adaptation of Thunderball. More about that on Thursday, though. "The Living Daylights" was also published in the United States a few months later in Argosy magazine.

"The Living Daylights" was first published in 1962 as part of a color supplement for The Sunday Times. The Times was a rival to the Daily Express, which had been serializing and adapting Bond stories for about six years by that point, so the Express was naturally upset. In fact, "The Living Daylights" created a big rift between Fleming and the Express to the point that the Bond strip was abruptly ended part way through the adaptation of Thunderball. More about that on Thursday, though. "The Living Daylights" was also published in the United States a few months later in Argosy magazine.I have a lot of praise to gush on the movie The Living Daylights, which I'll do at the proper time, but one of the things I love about it as that it adapts its short story pretty faithfully, but with a twist that propels the rest of the movie. In the short story, Bond is called to Berlin to assassinate the person who has in turn been assigned to assassinate someone escaping to the West. In the short story, the escapee is a returning double agent instead of a defector, but Bond is still supervised by a tiresome liaison and still changes his shot when he discovers that his target is a woman. And not just any woman, but a cellist he's been watching and fantasizing about as she's come and go from a nearby building over a few days.

One of my favorite lines in the movie version is when Bond lashes back at his annoying supervisor by exclaiming that the worst that can happen is that M will fire Bond, but that Bond would "thank him for it." I've always associated that with Bond's attitude at the end of Casino Royale, but re-reading "The Living Daylights" reminds me that it's yet another element right out of the short story. Bond is uncharacteristically sulky in this story and grumbles a couple of times about not minding if he gets kicked out of the Double-O section.

The best explanation that I have for that is that Bond is changing as a person. He's become less and less selfish since Dr No and has apparently become a happier person for it. Certainly his sense of humor has improved in Goldfinger and Thunderball. There's even a bit in "The Living Daylights" where he acknowledges to someone that the Bentley is a "selfish car." That kind of awareness is remarkable and important. It shows that while Bond still loves his car, he's also a little embarrassed about what it says about his past self. He sees that past selfishness and is able to comment on it, which I don't think he would've been able to do in the early books.

As Bond continues to change, it makes sense that he's becoming less patient with the uglier aspects of his job. His current mission is outright, cold-blooded assassination. He's never been super fond of that (as we saw in From Russia with Love), but it seems to be really getting at him now. The only time he's seemed okay with it was in "For Your Eyes Only," but that was more about his compassion for M than about willingly taking another person's life. My theory about Bond's attitude in "The Living Daylights" is that the assignment has got him especially down and is creating a bad attitude about his job and life in general. If it pops up again over the next few assignments, I'll adjust that theory, but it works for now.

One last thing that bothers me (not about Fleming's writing, but about Bond's mindset) is that Domino doesn't come up at all. From a storytelling perspective, I don't actually expect her to, but from a fannish, continuity-exploring perspective, I wish that there was more fallout from that relationship than just Bond's fantasizing about a pretty cellist. I fantasized myself about Bond and Domino's forming a mature relationship, so it hurts a little that she's just disappeared over the last couple of stories. There may be good, extratextual reasons for that (McClory?), but again, I'm just talking about continuity. Something apparently happened between Bond and Domino to sour things and I want some closure. I don't expect Fleming's next full novel, The Spy Who Loved Me to explain it, but I wish it would. And if not, I'm perfectly willing to come up with something on my own.

[Argosy cover found at Galactic Central]

Published on August 11, 2014 04:00

August 8, 2014

Octopussy and The Living Daylights | "Octopussy"

The short story “Octopussy” was written late in 1962, but wasn’t published until 1965, after Fleming’s death. It was serialized in the Daily Express, which had also published “From a View to a Kill,” “Risico,” the James Bond comic strip, and had serialized both Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia with Love.

The short story “Octopussy” was written late in 1962, but wasn’t published until 1965, after Fleming’s death. It was serialized in the Daily Express, which had also published “From a View to a Kill,” “Risico,” the James Bond comic strip, and had serialized both Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia with Love. Fans of the movie Octopussy will remember that Maude Adams’ character is friendly towards Bond because he had once allowed her proud, but criminal father the choice of suicide instead of the humiliation of a public trial. The short story is the account of that confrontation and choice.

“Octopussy” sometimes gets compared to “Quantum of Solace” in that Bond’s participation in the story is basically a bookend to the actual tale. But unlike “Quantum of Solace,” where Bond is simply being told the story as a way to pass time, he’s the catalyst for “Octopussy.” His investigation of a decade-old murder has led him to Dexter Smythe and Bond already has all the evidence he needs to put the old man away. As the movie Octopussy says, Bond does offer Smythe a week to get his affairs in order before he’s arrested, which Smythe believes is an opportunity to kill himself. I won’t spoil the ending, but let’s just say that it’s not as clean and simple as the way Maud Adams tells it.

Whatever Smythe’s final fate, it is pretty clear that Bond intends to let Smythe commit suicide as an alternative to spending his final days in prison. Which is an enormous kindness on Bond’s part considering Bond’s personal investment in the case. The reason Bond requested the investigation when it happened across his desk is that he had a personal relationship with Smythe’s victim. Bond reveals that the dead man was not only the person who taught Bond to ski as a teenager, but was also a surrogate father at a time when Bond really needed one. He offers no more detail than that, but it’s a major clue in the mystery of Bond’s childhood.

I’m reading the short stories in the order that they take place in Bond’s career, not in the order that Fleming wrote them, so it’s possible that Fleming confirms Bond’s being an orphan in one of the last novels. But chronologically, “Octopussy” is the first indication that Bond may have lost his parents and it seems to indicate that he was a teenager when it happened.

Published on August 08, 2014 04:00

August 7, 2014

"For Your Eyes Only": The Comic Strip

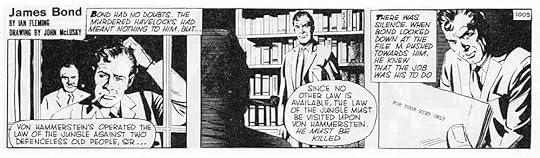

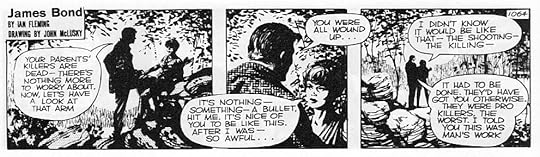

Like the other short story adaptations, the "For Your Eyes Only" strip leaves very little out. But what it does trim down actually improves the story.

When I wrote about Fleming's version, I pointed out that Bond seems a little nervous about pronouncing a death sentence on someone. That's usually M's job, but M is too close to the case, so Bond helpfully and compassionately takes that responsibility from his boss. That's very explicit in the short story, but in the comic strip, the conversation is abridged so that Bond isn't quite so on the hook. He endorses the mission, but he's not forced to make the call about whether the mission will even exist.

That takes out my favorite moment in Fleming's version, but it also allows a different reading of the entire story; a reading that fixes my least favorite part of Fleming's version. Since this is just another mission for Bond (albeit one with a personal angle for M), it offers some insight on Bond's attitude about assassination assignments. We'll talk more about this when we get to Fleming's "The Living Daylights," a story all about Bond's attitude towards assassination, but there are several moments in the "For Your Eyes Only" strip that reveal Bond's distaste for these kinds of jobs.

In Fleming's version of "For Your Eyes Only," Bond keeps telling Judy Havelock that assassination is "man's work" and it kills me that she accepts that by the end. But I let my distaste for Fleming's gender politics take over my reading and the comic strip version allows a different take. Bond expresses himself in a sexist way, but what lies beneath that is that he's protecting Judy from an action that he himself finds repellant. It's his job to sometimes assassinate people in cold blood, but he's growing less and less tolerant of that part of his duties. Again, we'll see this very clearly in "The Living Daylights."

So when Judy breaks down at the end of "For Your Eyes Only," she's not admitting that Bond was right about her being fragile because she's a woman. She's simply admitting that he was right about how horrible murder is. I'm curious to reread the end of Fleming's version and see if that reading makes sense there, but I suspect that it does. I'm betting that it's just buried more deeply, so I'm grateful to the strip for uncovering it.

Published on August 07, 2014 04:00

August 6, 2014

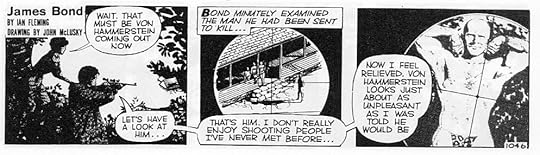

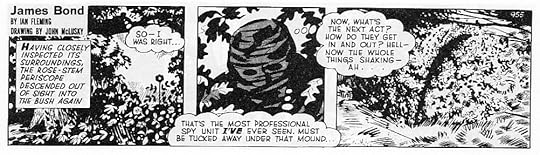

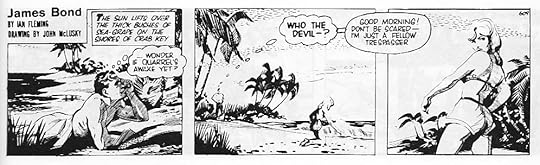

"From a View to a Kill": The Comic Strip

"From a View to a Kill" is another example of Fleming's short stories being well-suited for adaptation as comic strips. Henry Gammidge and John McLusky leave nothing out except for some of Bond's interior monologues. Because of that, Bond's introduction to Mary Ann Russell isn't nearly as sexy in the strip as Fleming writes it, but otherwise it's a fine adaptation of a rather mediocre story.

In fact, the way McLusky draws Bond's camouflage mask like the Unknown Soldier and his depiction of the entrance to the bad guys' lair are actually improvements on what I imagined while reading Fleming's version.

Published on August 06, 2014 04:00

August 5, 2014

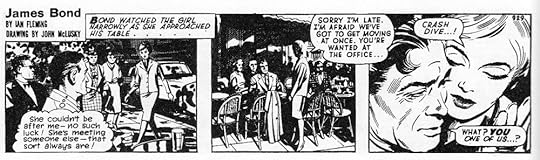

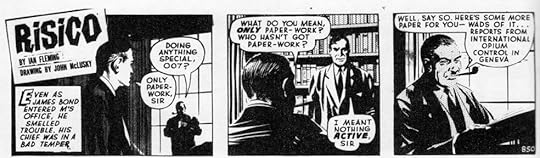

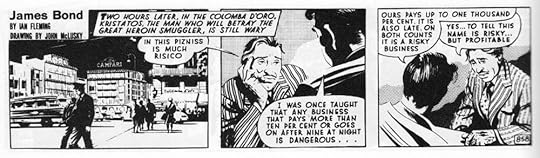

"Risico": The Comic Strip

Starting with the "From Russia with Love" strip, there's an upturn in the quality of the Bond comics and the series excels even more at adapting Fleming's short stories. The length of the "Risico" strip isn't much shorter proportionally than those adapting full length novels, so Henry Gammidge is able to take his time and build scenes instead of rushing through them. Reading the comic strip "Risico" is a lot like reading the prose "Risico," only with pictures.

And the pictures are pretty great. John McLusky has really found his stride and the art looks totally relaxed and confident. His Kristatos has a laid back, slimy quality that makes me smile and Bond looks a lot tougher and more serious than the smirking character in some of the earlier adaptations. Lisl Baum feels like a real person as opposed to some of the pinups McLusky was using for previous women.

"Risico" is so good that it represents a strip I'd look forward to reading even if it wasn't about one of my favorite literary characters. It's not only an excellent adaptation; it has enough great qualities to stand as its own thing. It has a mature feel to it, like it's not dumbing down the story, and that even extends to some of the language. Gammidge lets Bond say "hell" quite a bit, which isn't indicative of quality, but does seem like he and/or his editors are willing for this not to be seen as a kids strip.

Published on August 05, 2014 04:00

August 4, 2014

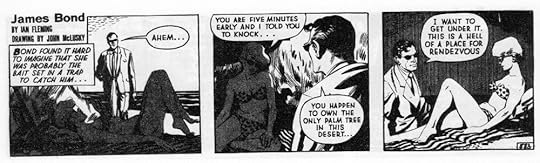

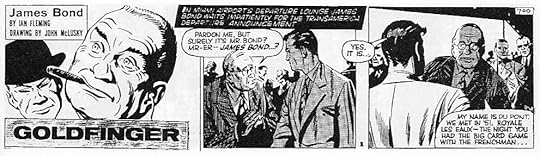

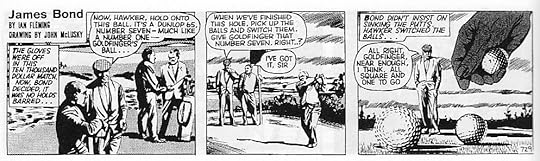

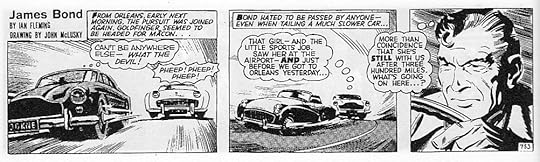

"Goldfinger": The Comic Strip

Henry Gammidge is back writing the James Bond strip with the "Goldfinger" adaptation, but he's in superior form. Like Peter O'Donnell in "Dr No," Gammidge has dropped the first person narration and it helps the strip a lot. He also takes his time with the story and it never feels rushed. Some scenes are shortened (the golf game, for example), but the cuts are usually good ones. In fact, there are some scenes (like Goldfinger's explaining the Fort Knox job to the gangsters) that could have been shortened even more, but I'd rather have them longer and be able to skim than to have the strip zoom through them too quickly.

There are some interesting cuts made for content, some of which I understand, but not all. I get why there's no mention of Tilly or Pussy's sexual orientation; that might be a conversation that parents in the '50s didn't want to have with their kids over the morning paper. I also understand why Goldfinger simply tells Oddjob to "remove" an offensive cat instead of offering it to the henchman as a meal. But I'm not clear why there's no mention at all of how Jill Masterton died.

Maybe it's because it would be difficult to suggest gold paint in a black-and-white strip, but a simple caption of text could have made that clear. I know the moment is iconic in part because of the film that didn't exist yet, so I want to cut the strip some slack. But it's difficult to read the adaptation and not feel that the loss of gold-covered Jill has left a huge hole in the story.

Those are all minor complaints next to most of Gammidge's other adaptations though. And though Gammidge isn't able to give the same amount of humor to Bond and Goldfinger's verbal war that Fleming does, that seems like an unreasonable expectation in the first place. All considered, "Goldfinger" is one of the best adaptations in the series so far.

Published on August 04, 2014 04:00

August 1, 2014

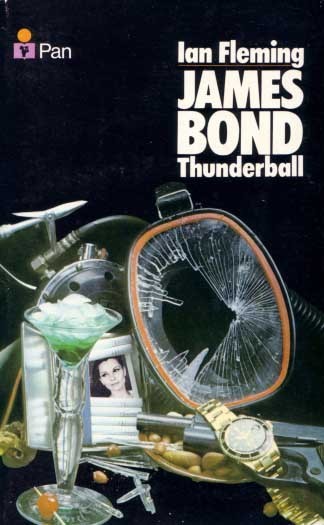

Thunderball by Ian Fleming

The creation of Thunderball is notoriously complicated. If most of For Your Eyes Only was the result of Fleming’s trying to bring Bond back to television, Thunderball was the result of his trying to get a film made. In late 1958, he teamed up with a few people including Irish writer/director Kevin McClory, hoping to create a Bond movie. Fleming and McClory weren’t the only people involved, but they were the two who ended up in court, so I’ll focus on them. Not that I’m going to spend much time on that drama, but it’s important to see how the book developed.

The creation of Thunderball is notoriously complicated. If most of For Your Eyes Only was the result of Fleming’s trying to bring Bond back to television, Thunderball was the result of his trying to get a film made. In late 1958, he teamed up with a few people including Irish writer/director Kevin McClory, hoping to create a Bond movie. Fleming and McClory weren’t the only people involved, but they were the two who ended up in court, so I’ll focus on them. Not that I’m going to spend much time on that drama, but it’s important to see how the book developed.According to Wikipedia, Fleming’s confidence in the potential movie fluctuated throughout its development, in part because one of McClory’s other movies bombed at the box office around that same time. So Fleming was more involved at some times and less at others, but between him and the other writers, close to a dozen different treatments, outlines, and scripts were created with lots of different titles. It’s impossible to verify who created what exactly, especially when it comes to the story’s most famous contributions to Bond lore: Ernst Stavro Blofeld and SPECTRE. Though the courts gave those elements to McClory for years, there’s a strong case to be made for Fleming’s contributing to them, especially since Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia with Love clearly show that he had a fondness for the word “spectre.”

Regardless of who contributed how much and which parts, Fleming was certainly on ethically shaky ground when he turned the collaboration into a novel with just his name on it. Once McClory got wind of that, he petitioned the courts to stop publication. That was denied, but the courts left the door open for McClory to pursue later action, starting a long, bitter feud between him and Fleming (as well as future caretakers of Bond’s adventures).

None of that would be important if Thunderball were a lousy or even mediocre book, but it’s not. It’s one of the best in the series and it’s worth wondering how much is due to Fleming’s evolving voice and how much is outside influences. It’s also futile to wonder about that, which is the frustrating thing, but from the direction that the Bond series had already been headed in, it’s safe to say that Fleming plays a major role in making Thunderball the masterpiece that it is.

None of that would be important if Thunderball were a lousy or even mediocre book, but it’s not. It’s one of the best in the series and it’s worth wondering how much is due to Fleming’s evolving voice and how much is outside influences. It’s also futile to wonder about that, which is the frustrating thing, but from the direction that the Bond series had already been headed in, it’s safe to say that Fleming plays a major role in making Thunderball the masterpiece that it is.A large part of that is because of Fleming's sense of humor. He was always a charming, funny man as made evident in a letter to cover artist Richard Chopping where he wrote, "The title of the book will be Thunderball. It is immensely long, immensely dull and only your jacket can save it!" That humor is what made Goldfinger great and it's back in this book, starting with the bit about Bond's being sent to Shrublands to get healthy. Fleming reveals that Bond smokes 60 cigarettes and drinks a half bottle of 60-70 proof alcohol every day, but the real reason Bond goes to the resort is because M's on a health kick. It's played for laughs with Bond's not wanting to go and Moneypenny's joking about M having a new bee in his bonnet. According to her, M gets interested in the latest fads a lot, whether it's this or exercise programs or dream analysis. It seems out of character for M, which makes me wonder if that's something another writer came up with, but it could just be Fleming's trying to lighten things up further.

Another new, out of character element is that Moneypenny explicitly has a crush on Bond. That's never been brought up before, but out of nowhere she and Bond are flirting and carrying on like they do in the movies. It's jarring, but it's still funny, as are M's whims and Bond's attitude before and after Shrublands. Before he goes in, he gripes like a sulking teenager, but once he comes out he's completely insufferable as he becomes a stuffy workhorse in the office and won't shut up about things like the benefits of proper chewing. Some of it had me literally laughing out loud.

We get some minor character development during this stuff, too. As much as Bond drinks, he's apparently not an alcoholic, because he gives up liquor for quite a while without any apparent effort. Fleming also reveals that Bond doesn't have as much of a car fetish as Casino Royale implied. That book called Bond's Bentley his "only real hobby" and talked about a neighborhood mechanic who fusses over the car, but Thunderball clarifies that Bond doesn't pamper the vehicle and even parks it outside in front of his flat instead of in a garage.

We get some minor character development during this stuff, too. As much as Bond drinks, he's apparently not an alcoholic, because he gives up liquor for quite a while without any apparent effort. Fleming also reveals that Bond doesn't have as much of a car fetish as Casino Royale implied. That book called Bond's Bentley his "only real hobby" and talked about a neighborhood mechanic who fusses over the car, but Thunderball clarifies that Bond doesn't pamper the vehicle and even parks it outside in front of his flat instead of in a garage.One element of Thunderball that I suspect had some non-Fleming involvement is its mystery plot. Apparently, McClory and his cohorts came up with the idea for hijacking a bomber with its nuclear cargo, so I wonder if they didn't also suggest how the case might be resolved. It's very different from Bond's previous investigations. I've written a lot about his "blunt instrument" approach and even though it was less of a conscious tactic in Doctor No and Goldfinger, Bond still wound up getting himself captured in both of those novels and then beating the villains from inside their own organizations through sheer resourcefulness and toughness. That never happens in Thunderball, which is pretty much a straight procedural with actual detective work.

To be fair, there's an extraordinary amount of hunch-playing in solving the mystery. Unlike the movie version, the literary Bond goes to the Bahamas on a hunch of M's. Bond thinks he's wasting his time, but of course takes the assignment seriously and works whatever angles he can find. Some of those are based on hunches he comes up with on the scene, and some are hunches of Felix Leiter who - thanks to the seriousness of the nuclear threat - has been drafted back into the CIA and assigned to work with Bond. These hunches all pay off, naturally, but it never feels like the characters are simply intuiting where the plot wants them to go. Instead, it feels like they're investigating the heck out of their corner of the mission and come up with leads based on solid evidence and intuition.

I guess this is a good place to talk about SPECTRE and Blofeld. Though there is a strong case for Fleming's creating those elements, it seems like a big coincidence that with all this writing help he suddenly and unceremoniously jettisons SMERSH as the series' major bad guys. SMERSH was a real organization that operated in the final years of WWII, but it only lasted three years and dissolved in 1946, well before the time period of the Bond novels. According to Thunderball, Fleming's SMERSH dissolved in 1958, which would have been shortly before the events of Goldfinger. That doesn't make sense though, since Goldfinger was said to be a major source of SMERSH funds, but maybe Goldfinger actually takes place in '58 (instead of 1959, when it was published) and the seizing of Goldfinger's bullion is what led to the ultimate destruction of the organization.

I guess this is a good place to talk about SPECTRE and Blofeld. Though there is a strong case for Fleming's creating those elements, it seems like a big coincidence that with all this writing help he suddenly and unceremoniously jettisons SMERSH as the series' major bad guys. SMERSH was a real organization that operated in the final years of WWII, but it only lasted three years and dissolved in 1946, well before the time period of the Bond novels. According to Thunderball, Fleming's SMERSH dissolved in 1958, which would have been shortly before the events of Goldfinger. That doesn't make sense though, since Goldfinger was said to be a major source of SMERSH funds, but maybe Goldfinger actually takes place in '58 (instead of 1959, when it was published) and the seizing of Goldfinger's bullion is what led to the ultimate destruction of the organization.At any rate, SMERSH no longer exists and some of its top members have now joined SPECTRE. As Fleming introduces Blofeld, he also gives some logic to a couple of elements that aren't explained really well in the films. First of all, the numbering system for SPECTRE's leaders is rotating and designed to confuse anyone trying to figure out the group's structure. For instance, during the events of Thunderball, Largo is Number One and Blofeld is actually Number Two (though he's still very much in charge). Another thing Fleming explains is Blofeld's device of pretending he's going to kill one underling before surprisingly murdering someone else. The films love to repeat that trick until it becomes a joke, but it has a very specific purpose in the novel. Blofeld is a careful, fastidious man and doesn't like unnecessary drama, so he puts his real victim off guard with a distracting, false victim. (Incidentally, I've decided that Alfred Molina would make an awesome Blofeld as written in Thunderball.)

One of my favorite things about Thunderball though is Domino Vitali. I suspect this is all Fleming, partly because of the care he takes in bringing her to life, but partly because of what she represents in the development of Bond's relationship with women. At the beginning of Thunderball, Bond is all fun and games with Shrubland's Patricia Fearing. He likes her, but like Jill Masteron in Goldfinger, it's just sex for both of them. (Incidentally, the literary Bond isn't as creepy as the movie Bond in this story. Instead of blackmailing Pat into sex, he takes the blame for his "accident" on the traction machine; and the infamous mink glove belongs to her, not him.)

One of my favorite things about Thunderball though is Domino Vitali. I suspect this is all Fleming, partly because of the care he takes in bringing her to life, but partly because of what she represents in the development of Bond's relationship with women. At the beginning of Thunderball, Bond is all fun and games with Shrubland's Patricia Fearing. He likes her, but like Jill Masteron in Goldfinger, it's just sex for both of them. (Incidentally, the literary Bond isn't as creepy as the movie Bond in this story. Instead of blackmailing Pat into sex, he takes the blame for his "accident" on the traction machine; and the infamous mink glove belongs to her, not him.)In Nassau though, he befriends Domino and we see the other side of Bond. He manipulates a meeting with her because she's a possible way to get close to Largo, whom Bond vaguely suspects as being a possible lead in his case. But he's quickly smitten with her, as was I. She's a wonderful character: confident and sexy; not afraid of danger. And unlike Pussy Galore or Judy Havelock, she stays that way until the end.

There's a little Liz Krest in her too, since she's the kept woman of an uncaring millionaire, and Bond plays much the same role with Domino that he did with Liz. With Domino, there's a flirtation right from the start (and it's a charming, funny, and dead sexy one), but there's also a lot of kindness on Bond's part. Enough so that I briefly wondered if that weren't just part of his game, but I decided it's not. We've never seen him take that approach before and the early Bond was written as mostly just getting by on his looks. There's a lovely scene in Thunderball though where Bond listens patiently and even encourages Domino as she tells him a fairy tale that she made up as a child about the artwork on the package of Player cigarettes. As tough as she is, he's gentle with her and when he eventually tells her that he loves her, I believe him. I think this could be his first, real, healthy relationship and I'm going to be sad to move on to the rest of the series without her.

Speaking of moving on and leaving characters behind, I feel like Fleming missed an opportunity by having Bond operate in the Bahamas and not meet the governor from "Quantum of Solace" again. Bond interacts with underlings instead and it's fun to think that the governor may be purposely avoiding Bond after their awkward dinner the year before. But it would've been even more fun to continue that relationship and let the governor see that his story has appeared to have a lasting impact on the womanizing secret agent.

Published on August 01, 2014 04:00

July 31, 2014

"Dr No": The Comic Strip

For the "Dr No" adaptation, the Daily Express had writer Peter O'Donnell fill in for Henry Gammidge. O'Donnell would go on to create the Modesty Blaise strip three years later, but he's already doing interesting things with his time on Bond. For starters, he drops the first person narration that Gammidge introduced and relies more on dialogue and short captions to tell the story.

As with the other strips though, "Dr No" jumps into the action as quickly as possible. Bond's convalescence after being stabbed with a poison shoe-knife was a one-panel epilogue in "From Russia with Love," so by "Dr No" he's ready to go. M doesn't explicitly refer to the Jamaica mission as a holiday, but Bond still sees it as a cake assignment and is grumpy about it.

That's just lip service to the book though, because the strip dives so quickly into the plot of "Dr No" that it doesn't feel like an easy assignment at all. There's more lip service paid to everyone's thinking that the two Jamaican agents ran off together, but really everyone knows that the agents were looking into Dr No and it's taken for granted that Bond will start his investigation there.

I've avoided naming the missing agents so far, because the strip does too for a good while. That's weird, because Strangways appeared in the strip version of "Live and Let Die," so it's not like O'Donnell is trying to fix a continuity issue, but maybe he wasn't aware of how the earlier story had used Strangways. Whatever the case, O'Donnell ignores the fact that Bond has a previous relationship with the missing agent, even when characters start referring to him as Strangways later in the story.

Once Bond's in Jamaica, the strip adapts the book closely, though Honey Rider is a bit more of a scaredy cat than she is in the novel. She still ends up rescuing herself though and O'Donnell plays a nice trick by intercutting between her being tied up on the rocky beach and Bond's navigating No's obstacle course. Whenever we see Honey, she's frantically worried and wondering to herself about how Bond is doing. If you don't know the story, you might think that she's hoping he'll free himself and rescue her, but she's actually just legitimately concerned for him. She's going to be fine. That's more clever and artful than I'm used to seeing from Gammidge.

It's great to see the end of the book brought to life accurately. I'm so used to the film version that those images are the ones I've always imagined when thinking about the story. But John McLusky's Dr No is perfect and I love that the obstacle course ends the way it's supposed to: with a giant squid fight. That's not a surprise considering how faithful the other strips have all been, but it's especially welcome with this story. McLusky draws some mean tentacles and a way cooler dragonmobile than the movie comes up with.

Published on July 31, 2014 04:00