Michael May's Blog, page 117

April 6, 2016

Happy Tenth Anniversary, Adventureblog

I don't usually celebrate blogiversaries, but ten years feels momentous enough to mention. Ten years ago today, I thought that I needed a better web presence than the crappy site I'd made for myself and Blogger seemed cheap and easy, so I started this thing. I wasn't sure what I was going to call it (and went through a couple of names before settling on this one) and I wasn't sure how it would be any different from my LiveJournal, which was a thing people used to do. Ten years later, I'm still experimenting and tweaking as I go, but I'm thankful to have a corner of the Internet that's all mine and that people seem to appreciate. Thanks to everyone for reading!

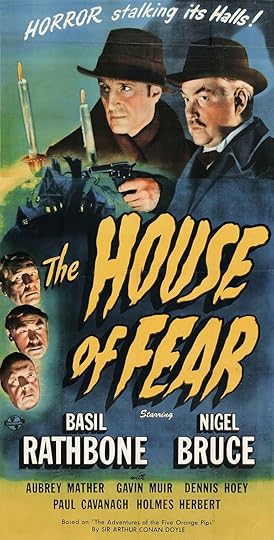

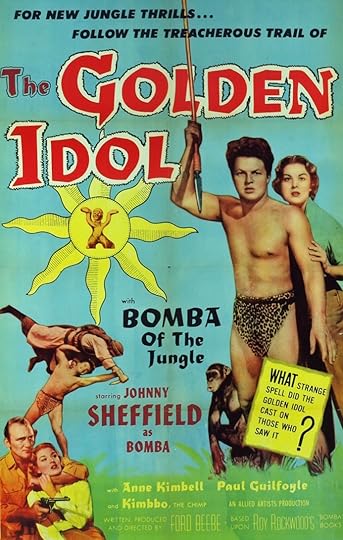

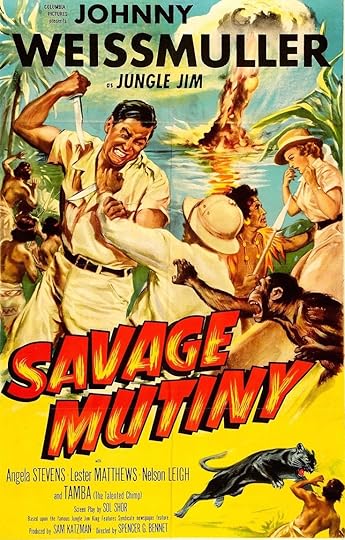

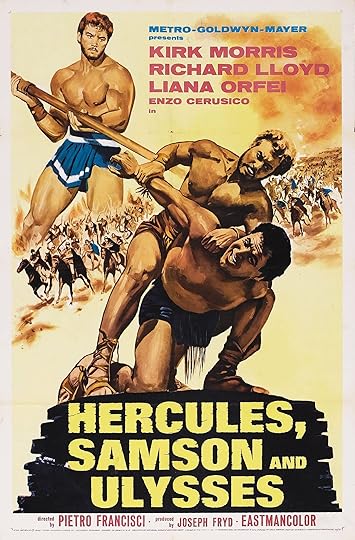

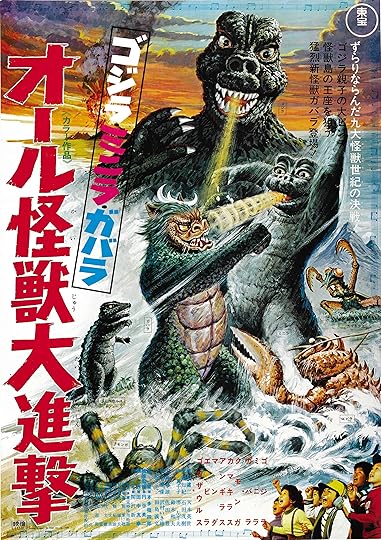

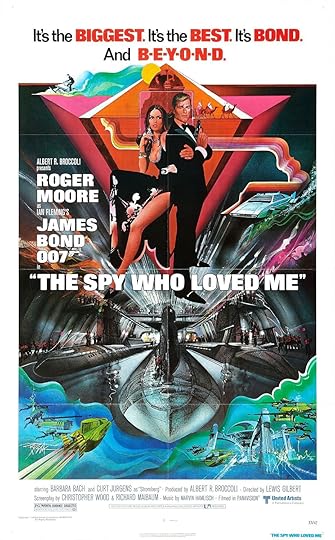

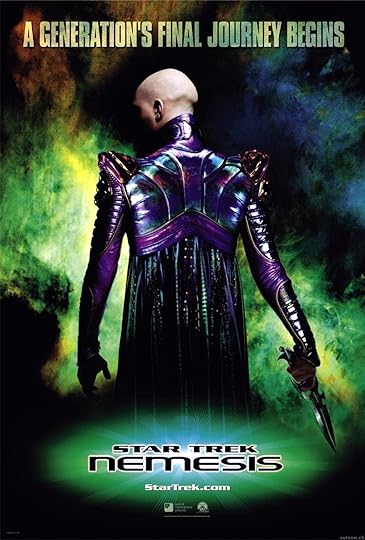

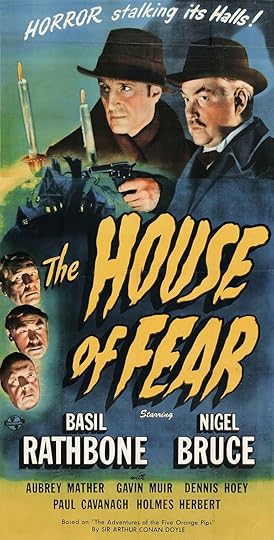

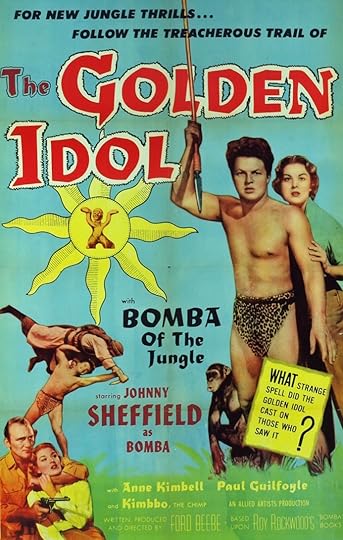

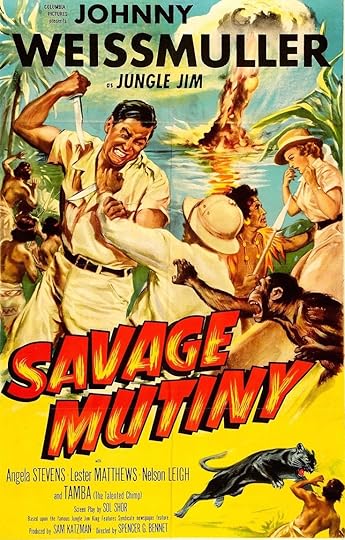

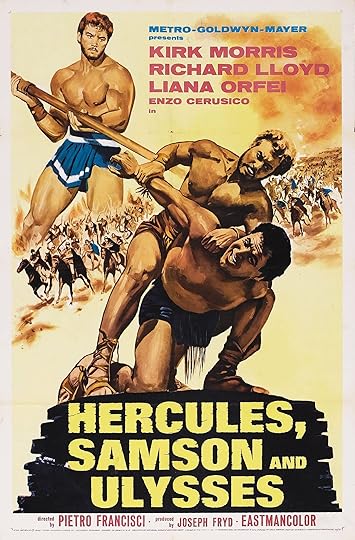

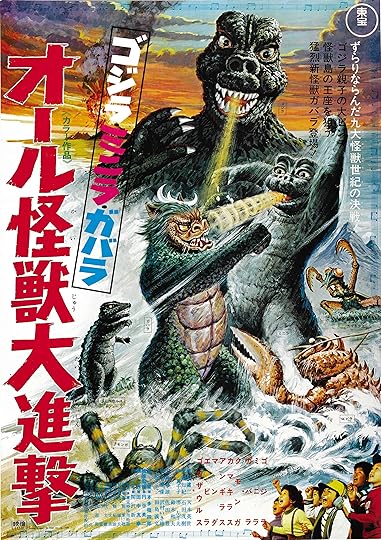

In celebration, here are posters for ten movies that were the tenth in their series. Please enjoy and make sure to grab some cake before you leave.

Pirate cake by Jen Benson at Craftsy.

In celebration, here are posters for ten movies that were the tenth in their series. Please enjoy and make sure to grab some cake before you leave.

Pirate cake by Jen Benson at Craftsy.

Published on April 06, 2016 10:00

April 5, 2016

British History in Film | 1066 and The Pillars of the Earth

I started this British History in Film project that I was just going to write about in the 7 Days in May feature, but it could make a fun feature in itself, so... spin-off! In last week's 7 Days in May, I wrote about King Arthur (2004) and The Vikings (1958). It's kind of appropriate to keep them separate since both are only historical in the loosest possible sense.

With this post, we're kicking off movies that we can actually put some dates to, because they include actual, historical events and people. Not that historical accuracy is going to be a requirement here. This is purely for fun.

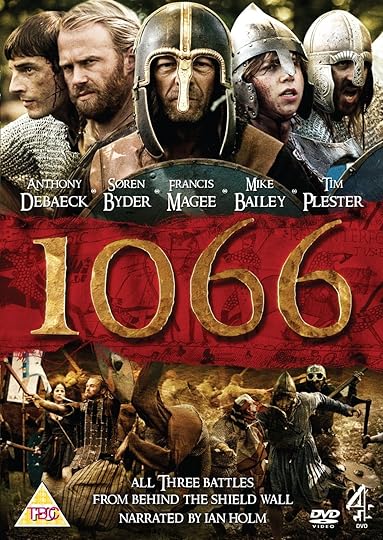

1066: The Battle for Middle Earth (2011)

First up is this documentary-style mini-series about the Viking and Norman invasions of Britain that led to the Battle of Hastings. It's pretty good and takes an unusual approach in focusing on the common soldiers rather than their leaders.

As the title suggests, it draws a lot of parallels with Tolkien's novels, staring with its being narrated by Bilbo Baggins himself, Ian Holm. Some of the connections feel unnecessary, like continually calling the Normans "orcs," but others - for instance, the reminder that England's defenders were mostly humble farmers from the shire - have a bigger impact. What the series never does though is actually mention Tolkien or explain why it's making these connections with his books, so it feels a bit pointless and mercenary overall.

The acting is fair and I ended up caring about the characters I was supposed to. The series also makes lovely use of the beautiful forests of England as the setting for these battles. It wasn't quite the narrative style I was looking for, but it ended up being a cool way to experience the story and learn some history.

The Pillars of the Earth (2010)

1066 covered the invasion of England by the Normans from France, led by William the Conqueror. I couldn't find any movies about his son, William II, but his grandson Henry is king when Ken Follett's The Pillars of the Earth kicks off. The mini-series opens with the sinking of the White Ship in 1120, which killed Henry's heir and sent England into a crisis over who was going to succeed.

The conflict around that is the backdrop to another story about the building of a fictional cathedral. The crown and the church and a couple of noble families all struggle for power with the cathedral project often being used as a bargaining chip. I'm gonna call it Game of Thrones Lite, but I don't mean it to be insulting. Pillars is playing in that same arena and is slightly less graphic, but it's also its own thing and totally captivating. My whole family was drawn in by these characters and the drama between them.

It's got a great cast, too, with Ian McShane as a wicked and ambitious clergyman and Matthew Macfadyen as the equally ambitious, but more noble priest trying to get the cathedral built. Rufus Sewell plays the builder in charge of the project and Eddie Redmayne is his apprentice, who also has a secret with important implications to the succession crisis. Donald Sutherland plays a noble who supports the underdog in the dispute, and Hayley Atwell is his daughter, though her role becomes much more important than just that.

I highly recommend the mini-series if you haven't seen it, so I won't spoil it (or 862-year-old history) by saying who wins the crown, but next week we'll pick up with a movie about the reign of that ruler.

Published on April 05, 2016 04:00

April 4, 2016

7 Days in May | Batman v Superman, more Buster Keaton, and gothic romance

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016)

I'd strongly considered skipping this in the theaters, but my movie buddy (and fellow Mystery Movie Night podcast host) Dave helped me remember that we see bad movies all the time. So, with the idea in mind that I was treating BvS no differently than an Uwe Boll movie, off we went.

And it was better than I expected, though that's a really low bar. It's built on the very shaky foundation of Man of Steel, which notoriously presented a brooding, selfish Superman. Because of that, the citizens of Superman's world can apparently react to him in only one of two ways: a god to be worshipped or a monster to be destroyed. One character pays lip service to a third option - that he's just a man doing the best he can - but that's not really explored.

In order to get the fight of the title in, Batman is forced to see Superman as a monster, but in an unconvincing way that makes Batman seem pretty dumb. So most of the movie is a bunch of people acting shallowly or stupidly. Lex has an interesting point of view - that Superman is a god and therefore must be destroyed - but Lex is so clearly insane that it's hard to take him seriously either. He's basically the Joker Lite.

Without anyone to care about, there are no stakes and most of the film is pretty dull. That changes somewhat once Lex's plan finally becomes active though. There's suddenly something to lose (in a contrived and cliché way, but still) and some of the action scenes are pretty cool, if not particularly thrilling. I even like where the relationship between the main characters ends up. It's just boring to watch them get there.

Affleck makes a fine Batman and I'm interested in seeing a solo film with him as long as Snyder and Goyer aren't creating it. Almost as interested as I am in the Wonder Woman film. BvS only teases what the character will be like, but so far so good. I'm hopeful about her and Aquaman's movies, but will need convincing about the Flash and Cyborg.

The Son of Tarzan (1920)

The first Tarzan serial starts off strong as it presents Tarzan, Jane, and their son living as the Greystones (ugh) in England, then works on getting Jack separated from his parents and off to Africa. Once he hits the jungle though, the story becomes repetitive for many, many chapters, with the same two or three people continually escaping from and getting recaptured by the same two or three other people. It picks up slightly at the end when Tarzan finally also returns to Africa and some new things start to happen. But even then a lot of the characters are still going through their usual and repetitive paces.

The print I watched was pretty murky, but the action would be hard to follow even on a clearer print, because the editing is super choppy.

On the positive side, it looks like the actor who played the adult Korak had a nice rapport with the elephant who played Tantor. Those characters made a great team and there seems to be some actual chemistry between them as they roam through the jungle together.

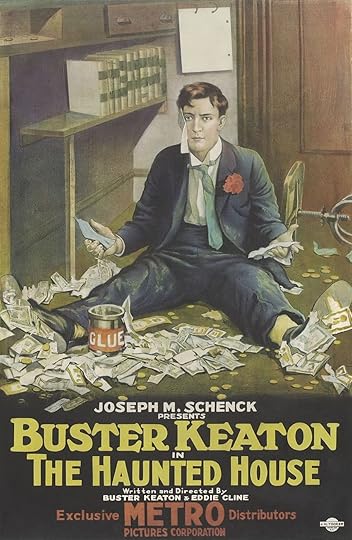

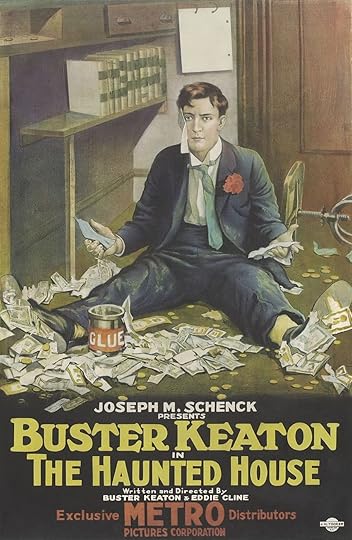

The Haunted House (1921)

Basically a harbinger of Scooby Doo with Buster Keaton (on the run after being framed for a bank robbery) and the cast of Faust simultaneously try to hideout in a house that's haunted by a gang of counterfeiters. Some great gags as usual, but also some truly spooky imagery.

Hard Luck (1921)

All over the place without much story to tie it together. Opens with down-on-his-luck Buster Keaton trying to kill himself in various ways, then turns to a brief adventure of his getting hired to hunt an armadillo, but that quickly becomes a fishing gag that finally leads to escapades at a country club.

There's about three minutes of missing footage, so that might explain some of the disjointedness, but as entertaining as Keaton films always are to me, this isn't one that I'll revisit a lot.

The Haunted Castle (1921)

No relation to The Haunted House. I watched this because someone described it to me as a gothic romance, but the building this takes place in is neither haunted (unless we're talking about the metaphorical sense) nor a castle. The Troubled Mansion doesn't have the same ring to it, I guess.

It isn't a horror picture at all, but a murder mystery that takes place a few years after the commission of the crime. Director FW Murnau's style isn't as developed as it would become in Nosferatu the following year, so except for some awesome black makeup around the lead actress' eyes, it's not even that visually interesting. Fortunately, it's only an hour long. I didn't enjoy it much.

The High Sign (1921)

Cute and very funny short in which Buster Keaton fakes his credentials to work at a shooting gallery. His alleged marksmanship gets him offered jobs to simultaneously murder and protect a millionaire and his daughter. One of my favorite Keaton films.

The Goat (1921)

Hilarious comedy-of-errors about Keaton's being mistaken for an escaped criminal. Lots of slapstick chases with some ingenious surprises.

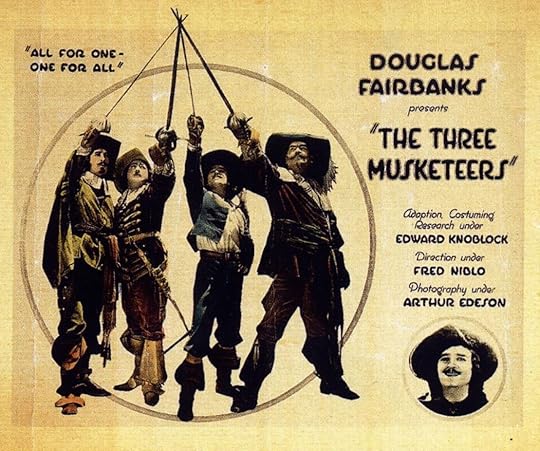

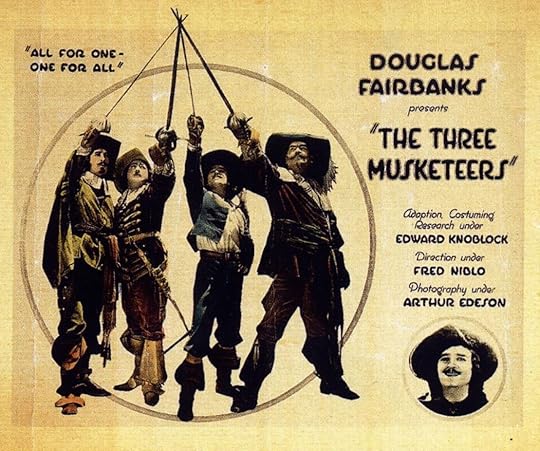

The Three Musketeers (1921)

Excellent adaptation that doesn't try to cover up the intricacies of Dumas' plot. Milady de Winter's role is simplified by ignoring her backstory, but there's still lots of maneuvering and intrigue to go with the swashbuckling. And Douglas Fairbanks is tops when it comes to swashbuckling, of course. His D'Artagnan can be annoying, but that's as Dumas wrote him.

The Play House (1921)

Sometimes, silent films can lead to some uncomfortable places, like this Keaton short that includes a minstrel show and the star in blackface. That's a quick bit though and the rest of the film is a lot of fun. It starts with a fantasy sequence in which Keaton plays every performer in a vaudeville show plus the entire audience, then goes into shenanigans behind the scenes of the real thing. A big highlight is when he accidentally frees a trained ape and has to perform as its substitute in the act.

The Boat (1921)

Sybil Seely is back! I love her team-ups with Keaton. This one has them as a couple who - with their two young children - attempt to launch a homemade boat. I prefer The Navigator when it comes to nautical Keaton, but still plenty of laughs here. And did I mention Sybil Seely is in it?

The Sheik (1921)

I've always wanted to see this Rudolph Valentino classic, but I didn't finish it. Agnes Ayres plays a spoiled bigot, but she doesn't deserve to be kidnapped and held indefinitely by Valentino's even more unpleasant character. Once they began to inexplicably fall in love, I checked out.

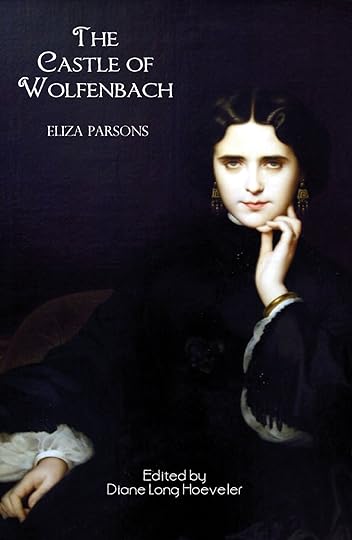

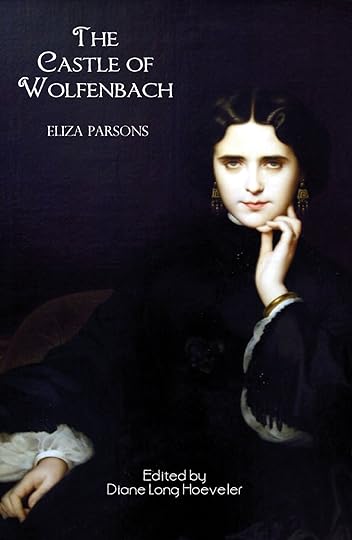

The Castle of Wolfenbach: A German Story by Eliza Parsons

On to some reading, I'm a fan of gothic romances and seeing Crimson Peak last year got me in the mood to read some. I love Castle of Otranto, Frankenstein, and Dracula, though I had a hard time getting through The Mysteries of Udolpho. Jane Austen may have called them "horrid novels," but I have a fondness for the twisty, coincidence-filled plots about guileless maidens and the wicked counts who try to control them.

Castle of Wolfenbach is a good one. It's full of the problems these kinds of books have: everyone is one-dimensional and there are so many counts and countesses that I literally lost track of them all. But as an oasis from more complicated literature, I enjoy the absolute goodness of the heroes in Wolfenbach and seeing the villains get their comeuppance.

Also, in addition to haunted rooms and secret passages, this one's got pirates.

The Octopi and the Ocean by Dan R James

This graphic novel has a cool idea to make humans pawns in the war between the octopi and the sharks. And James' whimsically surreal art makes it even more fun. It can be hard to decipher in places, especially toward the end where the story takes a creepy, darker turn, but it's a great concept and I love looking at it.

The Odyssey (All-Action Classics #3) by Homer, Tim Mucci, Ben Caldwell, and Emanuel Tenderini

The Odyssey isn't one of my favorite stories (Homer's classic is more episodic than I like), but if I'm going to read it, Ben Caldwell's All-Action Classics version is how I want it.

The All-Action series is excellent. It emphasizes the best parts of any book, but in a way that flows beautifully as a story and retains the spirit of the original work. There have been many attempts to adapt classic literature for kids - or just for people who don't think they like classic literature - but All-Action Classics is the best. Caldwell's art is exciting and fun to look at and he's working with writers like Tim Mucci who deeply understand the source material and what makes it great.

I'd strongly considered skipping this in the theaters, but my movie buddy (and fellow Mystery Movie Night podcast host) Dave helped me remember that we see bad movies all the time. So, with the idea in mind that I was treating BvS no differently than an Uwe Boll movie, off we went.

And it was better than I expected, though that's a really low bar. It's built on the very shaky foundation of Man of Steel, which notoriously presented a brooding, selfish Superman. Because of that, the citizens of Superman's world can apparently react to him in only one of two ways: a god to be worshipped or a monster to be destroyed. One character pays lip service to a third option - that he's just a man doing the best he can - but that's not really explored.

In order to get the fight of the title in, Batman is forced to see Superman as a monster, but in an unconvincing way that makes Batman seem pretty dumb. So most of the movie is a bunch of people acting shallowly or stupidly. Lex has an interesting point of view - that Superman is a god and therefore must be destroyed - but Lex is so clearly insane that it's hard to take him seriously either. He's basically the Joker Lite.

Without anyone to care about, there are no stakes and most of the film is pretty dull. That changes somewhat once Lex's plan finally becomes active though. There's suddenly something to lose (in a contrived and cliché way, but still) and some of the action scenes are pretty cool, if not particularly thrilling. I even like where the relationship between the main characters ends up. It's just boring to watch them get there.

Affleck makes a fine Batman and I'm interested in seeing a solo film with him as long as Snyder and Goyer aren't creating it. Almost as interested as I am in the Wonder Woman film. BvS only teases what the character will be like, but so far so good. I'm hopeful about her and Aquaman's movies, but will need convincing about the Flash and Cyborg.

The Son of Tarzan (1920)

The first Tarzan serial starts off strong as it presents Tarzan, Jane, and their son living as the Greystones (ugh) in England, then works on getting Jack separated from his parents and off to Africa. Once he hits the jungle though, the story becomes repetitive for many, many chapters, with the same two or three people continually escaping from and getting recaptured by the same two or three other people. It picks up slightly at the end when Tarzan finally also returns to Africa and some new things start to happen. But even then a lot of the characters are still going through their usual and repetitive paces.

The print I watched was pretty murky, but the action would be hard to follow even on a clearer print, because the editing is super choppy.

On the positive side, it looks like the actor who played the adult Korak had a nice rapport with the elephant who played Tantor. Those characters made a great team and there seems to be some actual chemistry between them as they roam through the jungle together.

The Haunted House (1921)

Basically a harbinger of Scooby Doo with Buster Keaton (on the run after being framed for a bank robbery) and the cast of Faust simultaneously try to hideout in a house that's haunted by a gang of counterfeiters. Some great gags as usual, but also some truly spooky imagery.

Hard Luck (1921)

All over the place without much story to tie it together. Opens with down-on-his-luck Buster Keaton trying to kill himself in various ways, then turns to a brief adventure of his getting hired to hunt an armadillo, but that quickly becomes a fishing gag that finally leads to escapades at a country club.

There's about three minutes of missing footage, so that might explain some of the disjointedness, but as entertaining as Keaton films always are to me, this isn't one that I'll revisit a lot.

The Haunted Castle (1921)

No relation to The Haunted House. I watched this because someone described it to me as a gothic romance, but the building this takes place in is neither haunted (unless we're talking about the metaphorical sense) nor a castle. The Troubled Mansion doesn't have the same ring to it, I guess.

It isn't a horror picture at all, but a murder mystery that takes place a few years after the commission of the crime. Director FW Murnau's style isn't as developed as it would become in Nosferatu the following year, so except for some awesome black makeup around the lead actress' eyes, it's not even that visually interesting. Fortunately, it's only an hour long. I didn't enjoy it much.

The High Sign (1921)

Cute and very funny short in which Buster Keaton fakes his credentials to work at a shooting gallery. His alleged marksmanship gets him offered jobs to simultaneously murder and protect a millionaire and his daughter. One of my favorite Keaton films.

The Goat (1921)

Hilarious comedy-of-errors about Keaton's being mistaken for an escaped criminal. Lots of slapstick chases with some ingenious surprises.

The Three Musketeers (1921)

Excellent adaptation that doesn't try to cover up the intricacies of Dumas' plot. Milady de Winter's role is simplified by ignoring her backstory, but there's still lots of maneuvering and intrigue to go with the swashbuckling. And Douglas Fairbanks is tops when it comes to swashbuckling, of course. His D'Artagnan can be annoying, but that's as Dumas wrote him.

The Play House (1921)

Sometimes, silent films can lead to some uncomfortable places, like this Keaton short that includes a minstrel show and the star in blackface. That's a quick bit though and the rest of the film is a lot of fun. It starts with a fantasy sequence in which Keaton plays every performer in a vaudeville show plus the entire audience, then goes into shenanigans behind the scenes of the real thing. A big highlight is when he accidentally frees a trained ape and has to perform as its substitute in the act.

The Boat (1921)

Sybil Seely is back! I love her team-ups with Keaton. This one has them as a couple who - with their two young children - attempt to launch a homemade boat. I prefer The Navigator when it comes to nautical Keaton, but still plenty of laughs here. And did I mention Sybil Seely is in it?

The Sheik (1921)

I've always wanted to see this Rudolph Valentino classic, but I didn't finish it. Agnes Ayres plays a spoiled bigot, but she doesn't deserve to be kidnapped and held indefinitely by Valentino's even more unpleasant character. Once they began to inexplicably fall in love, I checked out.

The Castle of Wolfenbach: A German Story by Eliza Parsons

On to some reading, I'm a fan of gothic romances and seeing Crimson Peak last year got me in the mood to read some. I love Castle of Otranto, Frankenstein, and Dracula, though I had a hard time getting through The Mysteries of Udolpho. Jane Austen may have called them "horrid novels," but I have a fondness for the twisty, coincidence-filled plots about guileless maidens and the wicked counts who try to control them.

Castle of Wolfenbach is a good one. It's full of the problems these kinds of books have: everyone is one-dimensional and there are so many counts and countesses that I literally lost track of them all. But as an oasis from more complicated literature, I enjoy the absolute goodness of the heroes in Wolfenbach and seeing the villains get their comeuppance.

Also, in addition to haunted rooms and secret passages, this one's got pirates.

The Octopi and the Ocean by Dan R James

This graphic novel has a cool idea to make humans pawns in the war between the octopi and the sharks. And James' whimsically surreal art makes it even more fun. It can be hard to decipher in places, especially toward the end where the story takes a creepy, darker turn, but it's a great concept and I love looking at it.

The Odyssey (All-Action Classics #3) by Homer, Tim Mucci, Ben Caldwell, and Emanuel Tenderini

The Odyssey isn't one of my favorite stories (Homer's classic is more episodic than I like), but if I'm going to read it, Ben Caldwell's All-Action Classics version is how I want it.

The All-Action series is excellent. It emphasizes the best parts of any book, but in a way that flows beautifully as a story and retains the spirit of the original work. There have been many attempts to adapt classic literature for kids - or just for people who don't think they like classic literature - but All-Action Classics is the best. Caldwell's art is exciting and fun to look at and he's working with writers like Tim Mucci who deeply understand the source material and what makes it great.

Published on April 04, 2016 04:00

March 28, 2016

7 Days in May | Pee Wee's Big Cloverfield

So here's what I watched last week:

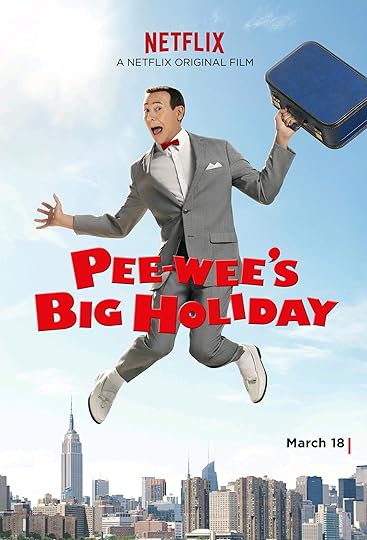

Pee Wee's Big Holiday (2016)

Nothing will ever top Pee Wee's Big Adventure, but Big Holiday is super funny and sweet. Makes me want to re-watch Big Top Pee Wee to see where that one went wrong. I don't remember much about Big Top other than being disappointed, but there's no such problem with Holiday. Although I also doubt I'll watch it over and over again the way I do Adventure.

10 Cloverfield Lane (2016)

Not the Cloverfield sequel I'd wanted, but an excellent thriller-with-a-twist nonetheless. Mary Elizabeth Winstead is a great, relatable hero and John Goodman does an excellent job keeping her and viewers on our toes. John Gallagher Jr is also compelling as the third major character and I had a good time trying to decide whether he or Goodman (or neither of them) was a villain.

The Peanuts Movie (2015)

Probably the last word on these characters, at least as far as I'm concerned. As sweet and funny as any of the classic shows, with a great balance of classic bits and new material. And what's so great about the new stuff is that it moves the kids' story forward and lets them learn something great about themselves. Just lovely and charming.

Top Secret! (1984)

Some of the jokes no longer hold up, but most of them still do and are just as funny after dozens of viewings. The music is also fun, as is the cast with Val Kilmer and Michael Gough (long before Batman Forever), Jim Carter in the complete opposite of his Downton Abbey role, and a cameo by Peter Cushing.

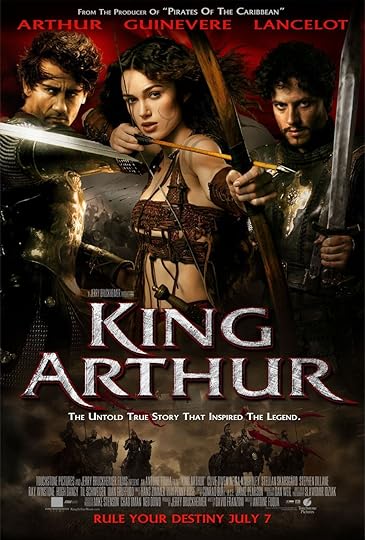

King Arthur (2004)

For the longest time, I've wanted to work my way through British history as portrayed in the movies. I finally started that with King Arthur, so obviously accuracy isn't a factor in this project. It's just that I generally like this movie and it 's one of the few I know of that cover the Roman occupation, the Celts, and the Saxon invasion.

Even though I like King Arthur, the premise does feel cynical. It's basically Braveheart with brand recognition. But even though it's derivative and only nominally an Arthurian film, it's gorgeously shot and has an amazing cast. I never feel like I'm watching a King Arthur movie, but I don't care. As a fictionalized account of Rome's last days in Britain, it's fun and compelling.

The Vikings (1958)

Pretty standard mid-'50s "historical" adventure, but it covers the Saxon period before the Norman invasion, which is rare. It has three things worth mentioning:

1. It's not sure what it wants to do with Kirk Douglas. He's clearly the villain for the entire movie, but I think the film wants to redeem him a little at the end. He never really changes though; he just hesitates at a crucial moment. The movie seems to want me to feel something other than simple victory when he dies, but it does nothing to help me do that.

2. The location of the Viking village is gorgeous. I could look at that place all day. I wish more of the movie was set there.

3. Tony Curtis is absolutely dreamy in a beard.

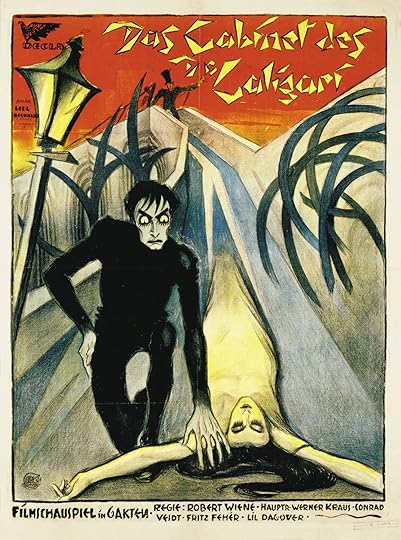

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Like last week, I'm continuing to work my way through a bunch of silent films. Some of them are new to me, but a lot of them are re-watches like Dr. Caligari. I've grown less satisfied with the twist ending on this one the more I see it, but I never get enough of looking at the movie. Just beautiful.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920)

Not my favorite adaptation of the story, but a good one. I wrote plenty about it already.

One Week (1920)

This short is one of my favorite Buster Keaton films of any length. It's got a great concept to build gags around (putting up a prefab house) and makes full use of the opportunities. Sybil Seely is super cute and a great partner for Keaton, bringing her own athleticism and comedy to the team.

The Saphead (1920)

Buster Keaton's first feature-length film is good, but not typical of his stuff. It's a pretty standard romantic comedy most of the way. It makes great use of Keaton's deadpan, sad sack persona to endear me to his clueless, insanely wealthy character. I root for him and Beulah Booker's character to overcome the obstacles to their being together, which are mostly thrown in the way by other people.

As straightforward as most of the movie is, the climax finally gives Keaton the chance to go nuts with his awesome physical comedy, so it's even good on that level. There's just not enough of it to be completely satisfying.

Convict 13 (1920)

One of the things I both admire and am frustrated by in Keaton shorts is the way he leads into the premise. Convict 13 is built around Keaton's being mistakenly imprisoned, with all the gags that take place in that setting. But there's a long explanation for how he got there, featuring golf jokes. The golf jokes are funny and pay off at the end, so I don't dislike them; it's just that - especially on re-watches - I'm impatient to get to the prison stuff that I consider the meat of the film. I've probably been over-influenced by Looney Tunes cartoons that cut to the chase right away.

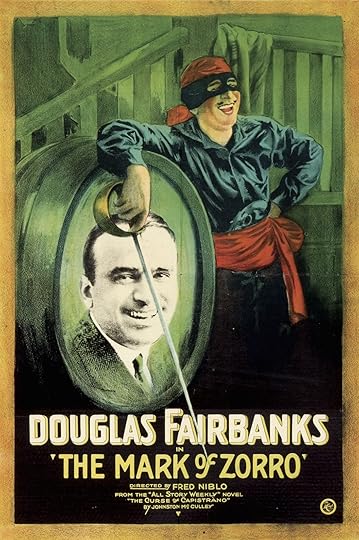

The Mark of Zorro (1920)

A splendid version of the Zorro story. Douglas Fairbanks isn't as handsome as some of his swashbuckling successors, but he makes up for that with sheer athletic ability and a ton of charm. His stunts in the climax are nothing short of early parkour.

He's also the model for what Christopher Reeve did with Superman/Clark Kent. He makes it believable that no one connects Don Diego with Zorro, because he plays them as two totally separate characters: sheepishly slouching as Diego, while full of life as the hero. I also love the touch of Diego's constantly amusing himself with shadow figures and little handkerchief tricks, then nerdishly trying to share them with the uninterested people around him. Great performance in a great movie.

Neighbors (1920)

Another of Keaton's best. Simple plot (star-crossed lovers in a New York tenement), super funny, and with some amazing stunts.

The Scarecrow (1920)

Like Convict 13, the story takes a while to get going. Before getting to the main plot about Keaton's rivalry with his roommate over a young woman, The Scarecrow indulges in lots of gags about the multi-functional gadgets of Keaton and his pal's one-room house. Then there's a bit about Keaton's being chased by a dog he thinks has rabies (actually it's just eaten a cream pie). But eventually feelings for Sybil Seely's character (so glad to see her return from One Week) reveal themselves and Keaton goes on the run from his roommate and Seely's father. Every bit of it is funny stuff, so I don't mind the meandering plot. It's just not as focused as my most favorite Keaton films.

On to some stuff I've been reading/listening to:

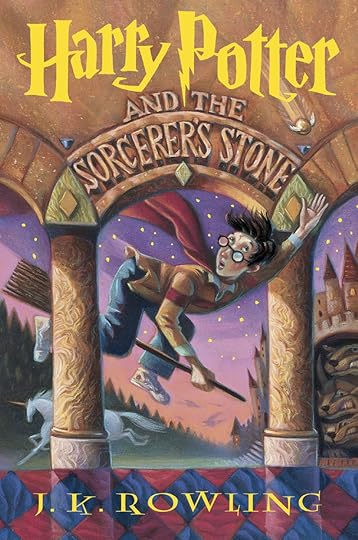

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone by JK Rowling

I discovered Harry Potter through the movies and by the time I did, I decided to discover that world through cinema first and then come back later and pick up the books. I finally read the first one on vacation a few years ago, but never found time to do the rest. Now that the audiobooks are available on Audible, I'm planning to listen to the whole series this year.

Philosopher's/Sorcerer's Stone is as magical as I remember from the first time reading it. Rowling has a wonderful imagination and a great sense of humor. It's a joy to attend Hogwart's alongside her characters. Some of the mystery-solving relies more heavily on coincidences than I'd like, but that's easy to forgive in a book about and for pre-teens. Especially since the characters' motivations and relationships are already so sophisticated. I'm eager to get on to brand new territory with Chamber of Secrets.

Long John Silver comics by Xavier Dorison and Mathieu Lauffray

This is a series of four comics albums and they're great. The first volume, Lady Vivian Hastings, is gorgeous. And it's an excellent sequel to Treasure Island. Lauffray's artwork is incredibly detailed and immersive. Dorison's plot introduces a fascinating character, Lady Hastings, who is as different from Jim Hawkins as can be. Delightfully wicked, cunning, and courageous, she's a worthy foil for Silver and the perfect person to bring him into a new treasure-seeking venture. And Silver himself is as charmingly crafty as ever. (I went into more detail about this one a couple of years ago.)

A lot of stories set at sea bore me with the same old tales of storms and doldrums and complaining crews, but Neptune, the second installment, avoids that by filling the time with politics and scheming. It's the same tactic that Stevenson used in Treasure Island, but to very different results. Stevenson's adventure story has its moments of darkness, but this is a scarier version with rougher stakes.

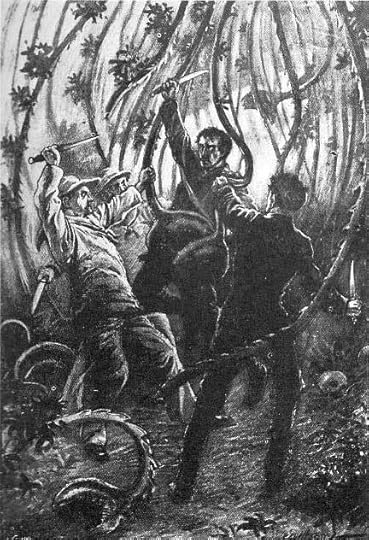

In part three, The Emerald Maze, the pirate adventure becomes more psychological thriller and Heart of Darkness. The crew of treasure-seekers heads upriver into the jungle in search of a lost, gold-filled city, and doubts arise in some of them about the wisdom of the venture.

Finally, the whole thing wraps up in Guyanacapac. I always worry about how well these things are going to end, but Dorison and Laufray do a nice job with a conclusion that's both epic and emotionally satisfying. They have pirates fighting Aztecs with shades of Lovecraft looming over it all. They also offer a great read on the character of Long John Silver and what drives him. Great series of books. Highly recommended.

Published on March 28, 2016 04:00

March 25, 2016

You Will Believe a Man Can Podcast

I'm spending more time podcasting lately, so it's a shame that I'm so lousy when it comes to telling people about it. Here's some stuff I've been up to the last few weeks. I've included links in the descriptions, but everything's also available on iTunes.

On the most recent Starmageddon episode we talked about Star Wars 8 director Rian Johnson, whom I'm a big fan of thanks to Looper and The Brothers Bloom and Dan likes for his episodes of Breaking Bad. We also geeked out about Bryan Fuller's coming on board the new Star Trek TV series and how that's going to be a tough show to dismiss by people upset about CBS All Access. Finally, we also had a great discussion about the idea of canon, especially as the term is used in the Star Wars universe. Is it a useful concept or just a marketing tool?

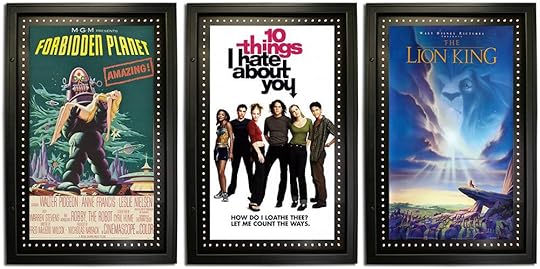

Early this month, the Mystery Movie Night gang got together again for our second episode. Sadly, my brother Mark couldn't join us for this one, but Erik Johnson led the rest of us in a discussion about classic '50s scifi, '90s teen comedy, and a Disney "masterpiece." Is Forbidden Planet as good as it is influential? Is 10 Things I Hate About You a worthy heir to the John Hughes legacy? Does The Lion King live up to its reputation as a Disney classic? And what do all of these movies have in common? Plus: Our favorite Disney animated features!

We're adding a new feature to Dragonfly Ripple called "Riplets," basically mini-episodes that fall outside the format of the regular show. Our first one features Carlin and Annaliese checking out ALT*Con Florida 2016, their local sci-fi and gaming convention. It's a companion piece to Carlin's Nerd Lunch "Extra Helping" which has him and Annaliese live at the show, conducting interviews. The Riplet is their follow-up chat after the show, focused on Annaliese's thoughts about the experience.

Early this week, Pax and I dropped another episode of our Western podcast, Hell Bent for Letterbox. In this one, we talk about Kurt Russell's other Western from last year, Bone Tomahawk. But not before we mention other Western things we've been up to like The Covered Wagon (1923), Hang ‘Em High (1968), and the comics Django/Zorro and Manifest Destiny.

And then finally (for now), Carlin and I got to appear as guests on Pax's other podcast (with co-hosts Jaime Hood and Shawn Robare), Cult Film Club. Jaime wasn't able to be on this one, but Carlin and I filled in as best we could, helping Shawn and Pax mark the opening of Batman v Superman with a discussion of Superman IV: The Quest for Peace. It's a great conversation about a movie that - messed up as it is in many places - is still one of my favorite Superman films.

Published on March 25, 2016 20:23

March 23, 2016

The Top of the World: The Fiction of Ian Cameron [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

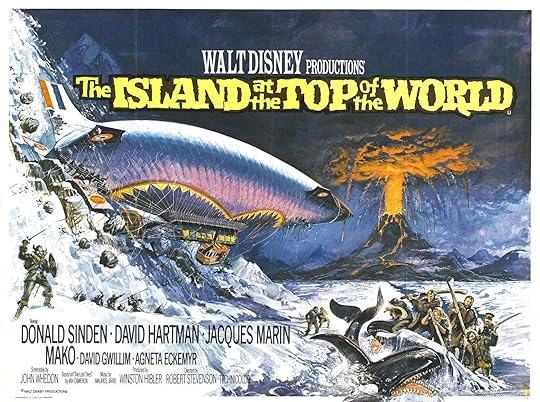

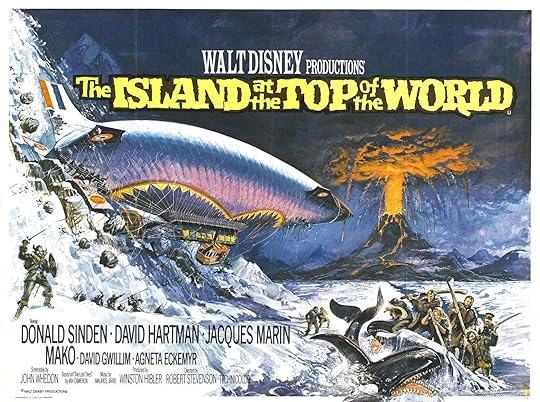

A bad movie can scar the reputation of a good book for many years. One such is The Lost Ones (1960), better known as Island at the Top of the World by Ian Cameron. Forget the Disney movie, forget David Hartman, forget the dirigible. Island is a great adventure book. This is a bold statement when you consider the last true classics of this genre date back to H Rider Haggard and Edgar Rice Burroughs. The true adventure novel has long since disappeared. Or has it?

A bad movie can scar the reputation of a good book for many years. One such is The Lost Ones (1960), better known as Island at the Top of the World by Ian Cameron. Forget the Disney movie, forget David Hartman, forget the dirigible. Island is a great adventure book. This is a bold statement when you consider the last true classics of this genre date back to H Rider Haggard and Edgar Rice Burroughs. The true adventure novel has long since disappeared. Or has it?

Cameron's book is a real treat. Well-paced, a page-turner, and not much like the silly Disney movie. It is the most fun you can have for so cheap a price too. Go to any used book store and you'll find a dozen copies in the cheapie bin. Unjustly forgotten. Island, like so many other books used by Hollywood, suffered from quick-buck merchandising. The 1974 cover features the movie poster and looks like a bad movie tie-in. People have forgotten the original along with the movie.

The basic storyline involves a group of rescuers in search of a pilot, the son of the expedition's leader, who has disappeared in the Arctic, into a place where the native Inuit will not go. The rescue party ventures to this mysterious volcanic island, but not in an airship. (That idea was stolen from Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan at the Earth's Core (1929) where a dirigible enters the fantastic land of Pellucidar through a polar opening.) Cameron's original team travel by ship and then on dog-sleds.

The strange land they find is populated by a mixed race: half Norwegian Viking, half Inuit. The rescuers flee a power-crazy shaman only to become trapped in the whale's graveyard, the original goal of the lost son. There they find him with the help of his future bride, Freyja, a local girl. The party's escape is slowed by a swarm of killer whales who guard the sea in a scene that may be controversial but very exciting. The book never indulges in gross unbelievability since the author knows he needs a delicate touch to win our willing suspension of disbelief. Like Jules Verne before him, Cameron blends facts with the imaginary in a delicate net that draws you in.

The strange land they find is populated by a mixed race: half Norwegian Viking, half Inuit. The rescuers flee a power-crazy shaman only to become trapped in the whale's graveyard, the original goal of the lost son. There they find him with the help of his future bride, Freyja, a local girl. The party's escape is slowed by a swarm of killer whales who guard the sea in a scene that may be controversial but very exciting. The book never indulges in gross unbelievability since the author knows he needs a delicate touch to win our willing suspension of disbelief. Like Jules Verne before him, Cameron blends facts with the imaginary in a delicate net that draws you in.

Ian Cameron was a bit of a mystery since the name is a pseudonym. The author is actually Donald Gordon Payne, an English writer who had his first hit with Walkabout (1959) as James Vance Marshall. He wrote other books, but none under his real name. The Lost Ones was the first of three novels he would pen between 1960 and 1976 in a Jules Verne mode.

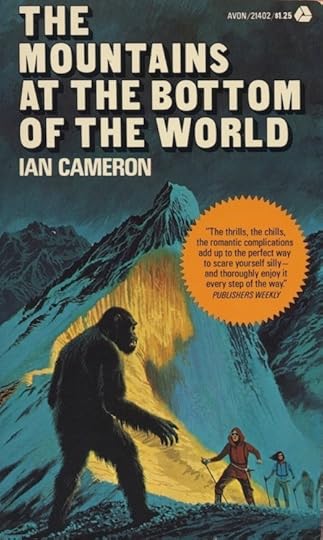

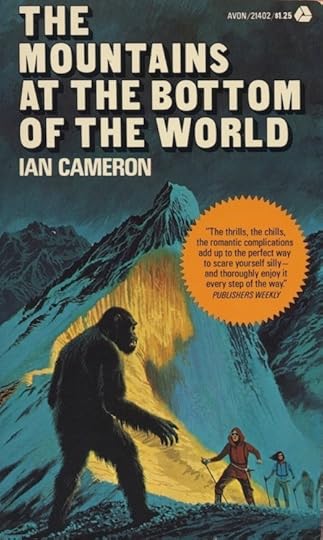

The second book was titled The Mountains at the Bottom of the World (1972), an obvious connection to the Disney movie, but was later released as Devil Country. This novel has a team of explorers going to the Andes to dispute a border between countries, but find a race of sasquatch-like creatures who are the survivors of a prehistoric race. The journey is difficult, as the Andes are some of the toughest mountains in the world, but the cavemen are worse, being man-eaters. The captives are held prisoner for a while, the cavemen saving them to be eaten later. Cameron does some of his best writing in this book, but the plotting sadly is very familiar to anyone who has read The Lost Ones. Despite this, and yet more volcanic escapes and chases, the story never lags and the characters are enjoyable.

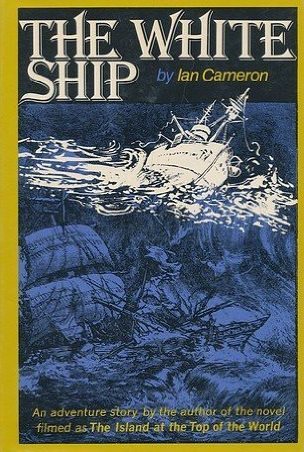

The last of the trio is The White Ship (1976), which takes place on Candlemas Island in the South Sandwich Islands, probably the most remote and dangerous place in the world. A scientist gets hooked into a trip to the Antarctic by a strange but beautiful woman. She suffers from mediumistic spells in which she spouts archaic Spanish and has visions of gold-colored seals. The expedition suffers bad luck from the beginning when their helicopter crashes, killing half the crew and stranding them on the island for the winter.

The last of the trio is The White Ship (1976), which takes place on Candlemas Island in the South Sandwich Islands, probably the most remote and dangerous place in the world. A scientist gets hooked into a trip to the Antarctic by a strange but beautiful woman. She suffers from mediumistic spells in which she spouts archaic Spanish and has visions of gold-colored seals. The expedition suffers bad luck from the beginning when their helicopter crashes, killing half the crew and stranding them on the island for the winter.

We get to experience a number of fantastic scenes involving volcanoes (again!) as well as a giant squid, a snow petrel that is somehow linked to the mystery of the San Delmar (a Spanish ship that foundered on the island in 1820), and the ghost of a dead girl. In the end you find out what happened and how Susan exorcises her spirits. The plot is not as active as the preceding novels, for the scientists are stranded on an island, but Cameron does work in plenty of fumaroles and 1970s-style interest in the supernatural. Of his three books, I think it is the most grounded in reality, but consequently the least interesting. It was "Ian Cameron's" last Vernian adventure novel. Payne continued to write military novels and non-fiction under this name.

Was Ian Cameron the last of the old-style adventure writers, mixing fact and fancy in a restrained blend that skirted the edge of unbelievably? I think not. The three novels by Michael Crichton: Congo (1980) Sphere (1987), and Jurassic Park (1990) effectively spring-boarded from three classic adventure novels by HR Haggard, Jules Verne, and A Conan Doyle. Crichton doesn't rewrite them so much as take inspiration from them, mix in plenty of present-day technology, and see what happens. It's a much hipper way of doing what Cameron did and they all ended up as movies that didn't ruin the author. In the case of Jurassic Park, a movie franchise that is still going today. And Crichton is not the last either, with good writers like James Rollins taking us all over the world for daring-do in Subterranean (1999), Excavation (2000), Deep Fathom (2001), Amazonia (2002), Ice Hunt (2003) and the Sigma Force franchise. Adventure is not dead, merely the best-selling genre it was back in H. R. Haggard's day..

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

A bad movie can scar the reputation of a good book for many years. One such is The Lost Ones (1960), better known as Island at the Top of the World by Ian Cameron. Forget the Disney movie, forget David Hartman, forget the dirigible. Island is a great adventure book. This is a bold statement when you consider the last true classics of this genre date back to H Rider Haggard and Edgar Rice Burroughs. The true adventure novel has long since disappeared. Or has it?

A bad movie can scar the reputation of a good book for many years. One such is The Lost Ones (1960), better known as Island at the Top of the World by Ian Cameron. Forget the Disney movie, forget David Hartman, forget the dirigible. Island is a great adventure book. This is a bold statement when you consider the last true classics of this genre date back to H Rider Haggard and Edgar Rice Burroughs. The true adventure novel has long since disappeared. Or has it?Cameron's book is a real treat. Well-paced, a page-turner, and not much like the silly Disney movie. It is the most fun you can have for so cheap a price too. Go to any used book store and you'll find a dozen copies in the cheapie bin. Unjustly forgotten. Island, like so many other books used by Hollywood, suffered from quick-buck merchandising. The 1974 cover features the movie poster and looks like a bad movie tie-in. People have forgotten the original along with the movie.

The basic storyline involves a group of rescuers in search of a pilot, the son of the expedition's leader, who has disappeared in the Arctic, into a place where the native Inuit will not go. The rescue party ventures to this mysterious volcanic island, but not in an airship. (That idea was stolen from Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan at the Earth's Core (1929) where a dirigible enters the fantastic land of Pellucidar through a polar opening.) Cameron's original team travel by ship and then on dog-sleds.

The strange land they find is populated by a mixed race: half Norwegian Viking, half Inuit. The rescuers flee a power-crazy shaman only to become trapped in the whale's graveyard, the original goal of the lost son. There they find him with the help of his future bride, Freyja, a local girl. The party's escape is slowed by a swarm of killer whales who guard the sea in a scene that may be controversial but very exciting. The book never indulges in gross unbelievability since the author knows he needs a delicate touch to win our willing suspension of disbelief. Like Jules Verne before him, Cameron blends facts with the imaginary in a delicate net that draws you in.

The strange land they find is populated by a mixed race: half Norwegian Viking, half Inuit. The rescuers flee a power-crazy shaman only to become trapped in the whale's graveyard, the original goal of the lost son. There they find him with the help of his future bride, Freyja, a local girl. The party's escape is slowed by a swarm of killer whales who guard the sea in a scene that may be controversial but very exciting. The book never indulges in gross unbelievability since the author knows he needs a delicate touch to win our willing suspension of disbelief. Like Jules Verne before him, Cameron blends facts with the imaginary in a delicate net that draws you in.Ian Cameron was a bit of a mystery since the name is a pseudonym. The author is actually Donald Gordon Payne, an English writer who had his first hit with Walkabout (1959) as James Vance Marshall. He wrote other books, but none under his real name. The Lost Ones was the first of three novels he would pen between 1960 and 1976 in a Jules Verne mode.

The second book was titled The Mountains at the Bottom of the World (1972), an obvious connection to the Disney movie, but was later released as Devil Country. This novel has a team of explorers going to the Andes to dispute a border between countries, but find a race of sasquatch-like creatures who are the survivors of a prehistoric race. The journey is difficult, as the Andes are some of the toughest mountains in the world, but the cavemen are worse, being man-eaters. The captives are held prisoner for a while, the cavemen saving them to be eaten later. Cameron does some of his best writing in this book, but the plotting sadly is very familiar to anyone who has read The Lost Ones. Despite this, and yet more volcanic escapes and chases, the story never lags and the characters are enjoyable.

The last of the trio is The White Ship (1976), which takes place on Candlemas Island in the South Sandwich Islands, probably the most remote and dangerous place in the world. A scientist gets hooked into a trip to the Antarctic by a strange but beautiful woman. She suffers from mediumistic spells in which she spouts archaic Spanish and has visions of gold-colored seals. The expedition suffers bad luck from the beginning when their helicopter crashes, killing half the crew and stranding them on the island for the winter.

The last of the trio is The White Ship (1976), which takes place on Candlemas Island in the South Sandwich Islands, probably the most remote and dangerous place in the world. A scientist gets hooked into a trip to the Antarctic by a strange but beautiful woman. She suffers from mediumistic spells in which she spouts archaic Spanish and has visions of gold-colored seals. The expedition suffers bad luck from the beginning when their helicopter crashes, killing half the crew and stranding them on the island for the winter.We get to experience a number of fantastic scenes involving volcanoes (again!) as well as a giant squid, a snow petrel that is somehow linked to the mystery of the San Delmar (a Spanish ship that foundered on the island in 1820), and the ghost of a dead girl. In the end you find out what happened and how Susan exorcises her spirits. The plot is not as active as the preceding novels, for the scientists are stranded on an island, but Cameron does work in plenty of fumaroles and 1970s-style interest in the supernatural. Of his three books, I think it is the most grounded in reality, but consequently the least interesting. It was "Ian Cameron's" last Vernian adventure novel. Payne continued to write military novels and non-fiction under this name.

Was Ian Cameron the last of the old-style adventure writers, mixing fact and fancy in a restrained blend that skirted the edge of unbelievably? I think not. The three novels by Michael Crichton: Congo (1980) Sphere (1987), and Jurassic Park (1990) effectively spring-boarded from three classic adventure novels by HR Haggard, Jules Verne, and A Conan Doyle. Crichton doesn't rewrite them so much as take inspiration from them, mix in plenty of present-day technology, and see what happens. It's a much hipper way of doing what Cameron did and they all ended up as movies that didn't ruin the author. In the case of Jurassic Park, a movie franchise that is still going today. And Crichton is not the last either, with good writers like James Rollins taking us all over the world for daring-do in Subterranean (1999), Excavation (2000), Deep Fathom (2001), Amazonia (2002), Ice Hunt (2003) and the Sigma Force franchise. Adventure is not dead, merely the best-selling genre it was back in H. R. Haggard's day..

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on March 23, 2016 04:00

March 21, 2016

7 Days in May | Tarzan of the Apes and other silent films

I've been slacking off big time on blogging lately, so in the interest of getting back on track and having something here, how about a quick rundown of stuff I've been watching and reading lately? I'm on a silent movie kick, so let's start with what's been on my TV:

What the Daisy Said (1910)

This is a short DW Griffith movie. I've been curious about Griffith and talk about one of his other films below, but I didn't watch this one for him. It was included on the DVD for Mary Pickford's Daddy-Long-Legs that I'll also talk about below. Like Daddy-Long-Legs, Daisy stars Pickford, this time as one of two sisters who fall in love with a Romani man.

The movie seems to be trying to make a point about love, but I'm not entirely sure what it is. The daisy of the title is the "he loves me, he loves me not" flower, which seems to represent romantic destiny. The sisters try either to circumvent or second-guess their destinies by visiting a Romani fortune teller, but events punish them for that. So is the movie just about accepting fate? Because that's pretty lousy, but I haven't really found Griffith's other movies (I've seen Birth of a Nation, the first part of Intolerance, and Broken Blossoms) to be especially profound either.

I do like the movie though just for the beauty of its locations. Griffith shoots the action on some sets, but there are a couple of recurring locations - a flower field and a waterfall - that I loved returning to.

Dante’s Inferno (1911)

As plotless as the poem it's based on, but impressive. Basically a series of dioramas that are tied together with intertitles describing the action. They're faithfully and inventively adapted though and use the art of Gustav Doré for inspiration. And in my print, the whole thing is accompanied by a beautiful, haunting soundtrack by Tangerine Dream.

Tarzan of the Apes (1918)

My opinion hasn't really changed since I wrote this review.

Carmen (1918)

I never know how to feel about Carmen. I like her as a character, but I hate what she does to Navarro. I want to say that it's totally on him that he betrays everything he thinks he stands for in order to be with her, but she so clearly wants to manipulate and change him that she needs to be on the hook with him.

I watched the 1921 version with English title cards, renamed Gypsy Blood. I don't know if it's a strict translation or if the titles have been tweaked, but it really does play up the Roma angle more than the other silent version I've seen, Cecil B DeMille's from 1915. It even tries to give it a spooky, "gotcha" ending.

Daddy-Long-Legs (1919)

I wanted to see a Mary Pickford film just because she sounds like such a remarkable woman who was able to write her own ticket in Hollywood. She was a powerful figure in the movie business and co-founded both the United Artists studio and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Daddy-Long-Legs is a cute, but precious comedy in which Pickford plays an orphan girl. The first part of the movie focuses on her growing up in a cruel asylum, but able to keep her own spirits up as well as encourage the other kids. Eventually though, she gets word that an anonymous benefactor is going to support her through college. Not knowing his real name and only getting a brief glimpse of his shadow one day at the orphanage, Judy (Pickford) refers to him as Daddy-Long-Legs.

The movie becomes a romance once she goes to college. She meets a couple of men: the brother of one of her roommates and the uncle of the other. Both fall in love with her, but she's more drawn to the uncle, in spite of their age differences. Daddy-Long-Legs also seems to have an opinion about her love life and manipulates events from afar to drive her towards the uncle.

The revelation of Daddy-Long-Leg's identity is predictable and creepy, but that's not my only problem with the movie. Pickford is cute and funny as an actor, but Judy is overly adorable. The shenanigans she gets into at the orphanage feel like manufactured gags rather than honest examples of a girl making the best out of a tough situation. I didn't trust that director Marshall Neilan was playing fair with me, so I watched at an emotional distance instead of letting myself get involved. In contrast, Alfonso Cuarón's similarly themed A Little Princess was just as manipulative, but skillful enough that I didn't mind its yanking me around by my feelings.

Broken Blossoms, or The Yellow Man and the Girl (1919)

I don't remember exactly how this wound up on my Watch List. I'm guessing I put it there shortly after watching The Birth of a Nation and getting curious about DW Griffith and Lillian Gish's other collaborations. I tried Intolerance at some point and got bored with the heavy-handed moralizing in Griffith's attempt to counterpoint the horrible racism of Birth of a Nation. Unable to handle three hours of that, I probably wrote down Broken Blossoms as an alternative.

As the subtitle reveals, the movie still suffers from casual racism. It's not the aggressive sickness of Birth of a Nation though. In fact, a major purpose of Broken Blossoms is to fight against the Yellow Peril fears that were so prominent at the time. There are plenty of issues - from having white people play the major Chinese characters to the repeated, offhand use of a particular ethnic slur - but like Intolerance, the film's clear goal is to challenge prejudices and encourage kindness.

Also like Intolerance, it does this in a really blatant, melodramatic way. But at least there's a strong, central story and a focus on characters. It's not one that I'll re-watch, but its heart is in the right place and Gish's performance as a tortured victim of child abuse is remarkable and harrowing.

Now for a couple of graphic novels I've read recently:

Violenzia And Other Deadly Amusementsby Richard Sala

I'm a big fan of Richard Sala and Violenzia is more of what I love: cute girls and hapless boys trying to survive in a deadly world of madmen and monsters.

As usual, Sala suggests a deeper story than what's on the page with lots of references to mysterious characters and plots that will never be explained. Violenzia herself is an unknowable riddle and that's just the way I like it. With Sala, it's all about the story I'm reading right now. The rest of it is for me to imagine.

Baba Yaga's Assistantby Marika McCoola and Emily Carroll

Lovely drawings. I had a hard time figuring out how to take the story, but it works well enough as a contemporary fairy tale. There are suggestions that it's trying to subvert the genre, but it follows fairy tale logic so much - with its coincidences and thin motivations - that it never actually rises above the genre to comment on it. But maybe that's not what it's trying to do.

Published on March 21, 2016 04:00

March 7, 2016

Anne of Green Horrors [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

I suppose it's a national disgrace to admit you haven't read Lucy Maud Montgomery when you are a Canuck. (My mother was a big fan, but didn't pass it on to me.) If there is any room for forgiveness, it's that LMG was an Atlantic Canadian, while I am a true-born Westerner. (I have this odd theory that Ontario and onward doesn't really exist. You simply fall off the edge of Manitoba.)

I suppose it's a national disgrace to admit you haven't read Lucy Maud Montgomery when you are a Canuck. (My mother was a big fan, but didn't pass it on to me.) If there is any room for forgiveness, it's that LMG was an Atlantic Canadian, while I am a true-born Westerner. (I have this odd theory that Ontario and onward doesn't really exist. You simply fall off the edge of Manitoba.)

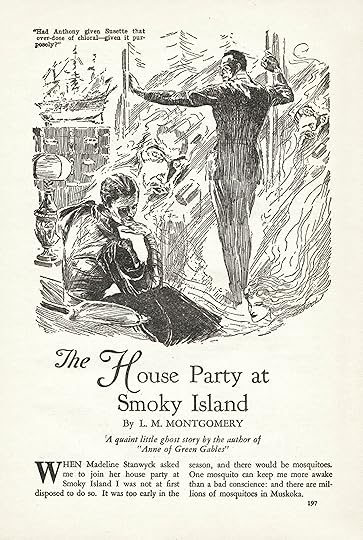

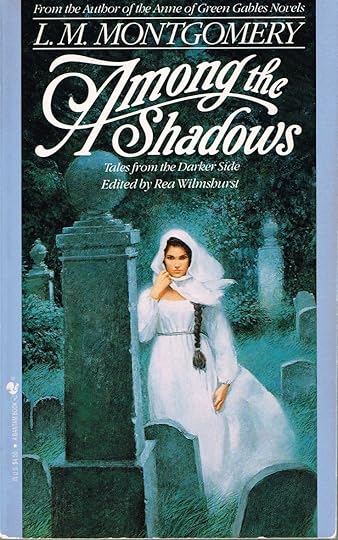

Imagine my surprise when I stumbled onto Weird Tales, August 1935, with its Doctor Satan cover, and hiding amongst the Paul Ernst, Seabury Quinn and Clark Ashton Smith is a little story called "The House Party at Smoky Island" by LM Montgomery. It turns out that LMG wrote quite a few of these "horror" stories, enough to fill a book, Among the Shadows: Tales from the Darker Side (1990), nineteen tales in all. But only one appeared in the Unique Magazine.

I read "House Party" in one sitting, finding it oddly compelling. Montgomery's style is so different from the typical Weirdies, with 1920s party fever that I haven't seen since I read Lord Peter Wimsey. Montgomery spends the first third of the story getting us caught up on all the gossip. The plot follows the narrator and his sister who invite a group of friends out to the wilds for a week of woodsy fun. Amongst the invites are Anthony Armstrong and his wife, Brenda, who have suffered marital difficulty because Anthony's first wife, Suzette Wilder died under mysterious circumstance, leaving him a large sum of money. Brenda has been distant for she suspects her husband a murderer. Nobody wants to talk about it, but the tension is evident.

Unfortunately for the partiers, it rains the entire time. Things between Anthony and Brenda don't improve and he finally leaves, perhaps for good. After a short discussion on the reality of ghosts, the party falls to telling ghost stories. The Judge tells a story about a house haunted by a child's voice; Dick tells a story about a dead dog who avenges his master; Consuelo tells a gruesome yarn about a ghost who came to the wedding of her lover; Ted speaks of a house with mysterious footfalls; and even Aunt Alma gets in on the action with a story about "a white lady with a cold hand," dressed in the style of the 1870s. One of the "pretty little things" is horrified, not at the undead, but of someone's dressing in crinoline. Brenda Andrews joins the party at this point.

Unfortunately for the partiers, it rains the entire time. Things between Anthony and Brenda don't improve and he finally leaves, perhaps for good. After a short discussion on the reality of ghosts, the party falls to telling ghost stories. The Judge tells a story about a house haunted by a child's voice; Dick tells a story about a dead dog who avenges his master; Consuelo tells a gruesome yarn about a ghost who came to the wedding of her lover; Ted speaks of a house with mysterious footfalls; and even Aunt Alma gets in on the action with a story about "a white lady with a cold hand," dressed in the style of the 1870s. One of the "pretty little things" is horrified, not at the undead, but of someone's dressing in crinoline. Brenda Andrews joins the party at this point.

Finally, Christine is invited to tell a story, though the narrator can't recall Christine's last name. She tells the story that everybody has been avoiding: that of Aunt Elizabeth Wilder, who left her money to Suzette, Anthony's first wife. Christine explains that Suzette was dying of a wasting illness, and began to hate her husband. She planned to write him out of the will at the end. Only Christine's intervention, a lethal overdose, stopped that from happening. Christine had loved Anthony from afar for a long time, though he never knew it. At this confession, Christine disappears, a ghost herself. Suddenly the narrator realizes he has never known or seen Christine before. Anthony appears, back from the rain, and Brenda runs to him, begging forgiveness. All is well again in the Armstrong household.

The finale is nothing special in ghost story terms. The old chestnut about one of the party being a spirit dates back to antiquity, though it never stopped Algernon Blackwood from using it again and again. The spectral elements fade at the end, returning to Montgomery's real forte: jolly tales of love and romance. What might have become a chilling tale of Poesque nightmare, veers back towards Edwardian geniality. And why not? This is a holiday outing, after all.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

I suppose it's a national disgrace to admit you haven't read Lucy Maud Montgomery when you are a Canuck. (My mother was a big fan, but didn't pass it on to me.) If there is any room for forgiveness, it's that LMG was an Atlantic Canadian, while I am a true-born Westerner. (I have this odd theory that Ontario and onward doesn't really exist. You simply fall off the edge of Manitoba.)

I suppose it's a national disgrace to admit you haven't read Lucy Maud Montgomery when you are a Canuck. (My mother was a big fan, but didn't pass it on to me.) If there is any room for forgiveness, it's that LMG was an Atlantic Canadian, while I am a true-born Westerner. (I have this odd theory that Ontario and onward doesn't really exist. You simply fall off the edge of Manitoba.)Imagine my surprise when I stumbled onto Weird Tales, August 1935, with its Doctor Satan cover, and hiding amongst the Paul Ernst, Seabury Quinn and Clark Ashton Smith is a little story called "The House Party at Smoky Island" by LM Montgomery. It turns out that LMG wrote quite a few of these "horror" stories, enough to fill a book, Among the Shadows: Tales from the Darker Side (1990), nineteen tales in all. But only one appeared in the Unique Magazine.

I read "House Party" in one sitting, finding it oddly compelling. Montgomery's style is so different from the typical Weirdies, with 1920s party fever that I haven't seen since I read Lord Peter Wimsey. Montgomery spends the first third of the story getting us caught up on all the gossip. The plot follows the narrator and his sister who invite a group of friends out to the wilds for a week of woodsy fun. Amongst the invites are Anthony Armstrong and his wife, Brenda, who have suffered marital difficulty because Anthony's first wife, Suzette Wilder died under mysterious circumstance, leaving him a large sum of money. Brenda has been distant for she suspects her husband a murderer. Nobody wants to talk about it, but the tension is evident.

Unfortunately for the partiers, it rains the entire time. Things between Anthony and Brenda don't improve and he finally leaves, perhaps for good. After a short discussion on the reality of ghosts, the party falls to telling ghost stories. The Judge tells a story about a house haunted by a child's voice; Dick tells a story about a dead dog who avenges his master; Consuelo tells a gruesome yarn about a ghost who came to the wedding of her lover; Ted speaks of a house with mysterious footfalls; and even Aunt Alma gets in on the action with a story about "a white lady with a cold hand," dressed in the style of the 1870s. One of the "pretty little things" is horrified, not at the undead, but of someone's dressing in crinoline. Brenda Andrews joins the party at this point.

Unfortunately for the partiers, it rains the entire time. Things between Anthony and Brenda don't improve and he finally leaves, perhaps for good. After a short discussion on the reality of ghosts, the party falls to telling ghost stories. The Judge tells a story about a house haunted by a child's voice; Dick tells a story about a dead dog who avenges his master; Consuelo tells a gruesome yarn about a ghost who came to the wedding of her lover; Ted speaks of a house with mysterious footfalls; and even Aunt Alma gets in on the action with a story about "a white lady with a cold hand," dressed in the style of the 1870s. One of the "pretty little things" is horrified, not at the undead, but of someone's dressing in crinoline. Brenda Andrews joins the party at this point.Finally, Christine is invited to tell a story, though the narrator can't recall Christine's last name. She tells the story that everybody has been avoiding: that of Aunt Elizabeth Wilder, who left her money to Suzette, Anthony's first wife. Christine explains that Suzette was dying of a wasting illness, and began to hate her husband. She planned to write him out of the will at the end. Only Christine's intervention, a lethal overdose, stopped that from happening. Christine had loved Anthony from afar for a long time, though he never knew it. At this confession, Christine disappears, a ghost herself. Suddenly the narrator realizes he has never known or seen Christine before. Anthony appears, back from the rain, and Brenda runs to him, begging forgiveness. All is well again in the Armstrong household.

The finale is nothing special in ghost story terms. The old chestnut about one of the party being a spirit dates back to antiquity, though it never stopped Algernon Blackwood from using it again and again. The spectral elements fade at the end, returning to Montgomery's real forte: jolly tales of love and romance. What might have become a chilling tale of Poesque nightmare, veers back towards Edwardian geniality. And why not? This is a holiday outing, after all.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on March 07, 2016 16:00

February 15, 2016

Plant Monsters: The Stories [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

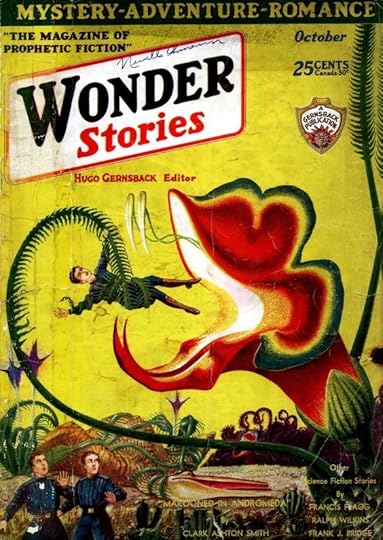

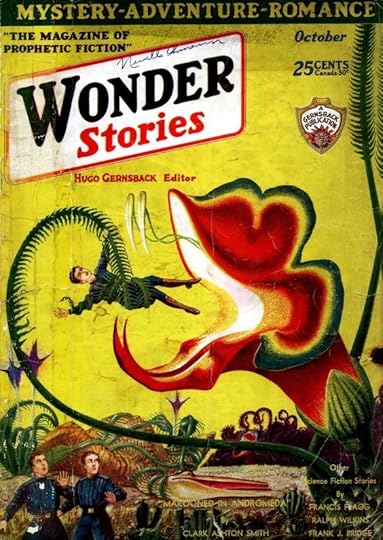

The first stories of killer plants were written by two Americans. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote "Rappacini's Daughter" in 1844 and showed us that a father's wish to protect his daughter's virtue can become almost pathological. Rappacini infuses the girl with plant poison, making her the precursor of Batman's Poison Ivy. The second story was twenty-five years later and written by the mother of the American family story, Lousia May Alcott, who penned Little Women (1868). Her story has the Gothic title of "Lost in a Pyramid, or the Mummy's Curse" and is the first real killer flower story. Seeds from a mummy's treasure grow into a large blossomed plant. When worn, the flower sucks the vitality from the wearer.

The first stories of killer plants were written by two Americans. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote "Rappacini's Daughter" in 1844 and showed us that a father's wish to protect his daughter's virtue can become almost pathological. Rappacini infuses the girl with plant poison, making her the precursor of Batman's Poison Ivy. The second story was twenty-five years later and written by the mother of the American family story, Lousia May Alcott, who penned Little Women (1868). Her story has the Gothic title of "Lost in a Pyramid, or the Mummy's Curse" and is the first real killer flower story. Seeds from a mummy's treasure grow into a large blossomed plant. When worn, the flower sucks the vitality from the wearer.

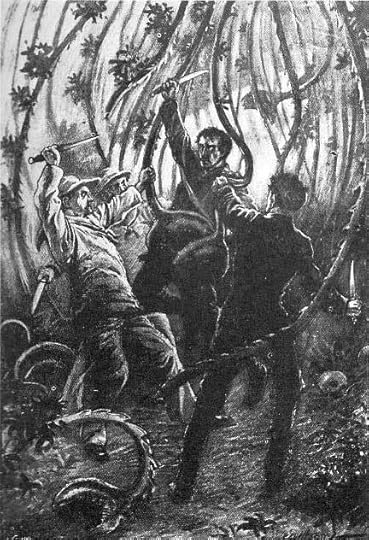

The idea of plant monsters really caught fire in the 1870s after botanical discoveries of large drosera and other flesh-eating plants were found and reported in the illustrated newspapers. These lead to fake reports which then lead to the storytellers of the day creating the first man-eating tree stories. These include A Conan Doyle, Julian Hawthorne, Phil Robinson, Grant Allen, and many lesser known writers. HG Wells reinvigorated the idea in 1894 with his blood-sucking orchid tale, "The Flowering of the Strange Orchid." I always used to think Wells invented the idea, but he comes to the part twenty years late. It was Frank Aubrey's The Devil-Tree of El Dorado (1896) that scores a hit in novel form. The Victorians would go on writing about killer plants all the way into the pulp era.

Weird Tales and the other pulps explored the idea with varying amounts of innovation. The Unique Magazine featured twenty-three killer plants (that I have discovered so far. I am sure there are others), beginning with "The Devil Plant" by Lyle Wilson Holden (May 1923) to Donald Wandrei's "Strange Harvest" (May 1953). May is significant, for I noticed, especially with the comics, that plant monsters tended to appear in that month as if the allergy season drove the concept of hostile plant life. Amongst the Weirdies to pen a plant story are Clark Ashton Smith (7), Edmond Hamilton (3), David H Keller (3), Howard Wandrei (2), Jack Snow, A Merritt, Seabury Quinn, Carl Jacobi, and Mary Elizabeth Counselman. The genres range from science fiction to horror. Clark Ashton Smith's "The Seed From the Sepulchre" and Jack Snow's "Seed" would be imitated (knowingly or unknowingly) in Scott Smith's bestseller The Ruins (2008). For this is another thing I have noticed, plant monster stories haven't really changed much, even after a hundred and forty years.

Weird Tales and the other pulps explored the idea with varying amounts of innovation. The Unique Magazine featured twenty-three killer plants (that I have discovered so far. I am sure there are others), beginning with "The Devil Plant" by Lyle Wilson Holden (May 1923) to Donald Wandrei's "Strange Harvest" (May 1953). May is significant, for I noticed, especially with the comics, that plant monsters tended to appear in that month as if the allergy season drove the concept of hostile plant life. Amongst the Weirdies to pen a plant story are Clark Ashton Smith (7), Edmond Hamilton (3), David H Keller (3), Howard Wandrei (2), Jack Snow, A Merritt, Seabury Quinn, Carl Jacobi, and Mary Elizabeth Counselman. The genres range from science fiction to horror. Clark Ashton Smith's "The Seed From the Sepulchre" and Jack Snow's "Seed" would be imitated (knowingly or unknowingly) in Scott Smith's bestseller The Ruins (2008). For this is another thing I have noticed, plant monster stories haven't really changed much, even after a hundred and forty years.

More modern times saw one story in particular pull the plant trope in a new direction. This was John Wyndham's blockbuster, The Day of the Triffids (1951). Unlike most plant monsters, Wyndham's triffids are not found in a jungle (or come from space as in the 1962 film), but are created specifically by men. Wyndham uses their nastiness (as well as the blinding of humanity) to comment on human ills (a la the Cold War). Other novels that explore plant monsters in a new way include Brian W Aldiss's fantasy Hothouse (1962), in which all the characters and setting are plants. Others like Susan Cooper's Mandrake (1962) and Frank Herbert's The Green Brain (1966) would predate James Lovelock's 1970s Gaia Theory, in which the entire Earth as a living organism fights back against humankind.

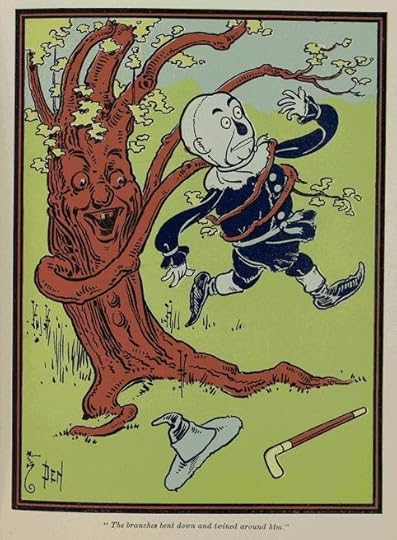

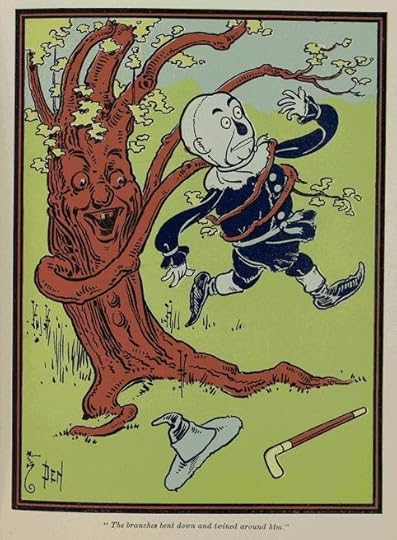

Fantasy has always featured supernatural trees in the form of dryads, sylphs, and mandrakes. L Frank Baum had fighting trees in The Wizard of Oz (1901), though they were reduced to talking trees in the film. JRR Tolkien would write about Old Man Willow and Treebeard the Ent in The Lord of the Rings (1954-56), while his friend, CS Lewis would use (to a much lesser degree) similar creations in his Narnia books (1950-55). Sword-and-sorcery of the 1970s would offer up new versions of the killer tree for the barbarians Conan and Brak to fight. And in most recent years, JK Rowling gave us the Whomping Willow of the Harry Potter series.

Fantasy has always featured supernatural trees in the form of dryads, sylphs, and mandrakes. L Frank Baum had fighting trees in The Wizard of Oz (1901), though they were reduced to talking trees in the film. JRR Tolkien would write about Old Man Willow and Treebeard the Ent in The Lord of the Rings (1954-56), while his friend, CS Lewis would use (to a much lesser degree) similar creations in his Narnia books (1950-55). Sword-and-sorcery of the 1970s would offer up new versions of the killer tree for the barbarians Conan and Brak to fight. And in most recent years, JK Rowling gave us the Whomping Willow of the Harry Potter series.

Modern horror hasn't lagged behind. While chasing Stephen King and Jaws-sized success, some less talented authors would write 1980s horror novels featuring killer vines, none worthy of particular mention. More interesting were the anthologies of older stories such as Vic Ghidalia's The Nightmare Garden (1976) and Carlos Cassaba's The Roots of Evil (1976). Many modern horror writers have created single, short exertions into plant monsterdom including Kit Reed, David Campton, Brian Lumely, and Jeff Strand. More often though, as from the very beginning, the majority of such tales were written by less well-known or even obscure writers who produced few or no other stories.

Scott Smith surprised the world of publishing with his novel The Ruins in 2006. While I gritted my teeth and held my tongue when mundanes thrilled to "the novelty," I can't say anything against Smith's book. He wrote it in a style that elevates it above mere pulp. While the flesh-eating vines are not new, his prose has a dreamy quality to it that lulls the reader into a sense of quiet before the monsters are unleashed. I heard the film version criticized as "just another 'let's watch a group of twenty-somethings get eaten' film" and I can understand this. The film lacks Smith's dreamy prose quality, though its CGI plants are quite frightening.

I haven't gone into a lot of TV or movies here, and no comics at all (for the comics always followed, never setting trends), because there simply isn't room. The only video productions that had anything really new to add were the Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), especially the musical version in 1986. "Feed me, Seymour!" the bulbous Audrey II cries, and in that moment, as the large-toothed mouth hovers over the insignificant Seymour Krelboyne, the final version of the plant monster has arrived at last. For every twelve-year-old kid who bought a Venus Flytrap to feed flies to, for every hunter lost in the bush, feeling like the forest was his living antagonist, for every allergy sufferer (I feel your pain!), here is the image of plant as hostile. We forget that they too are living, moving, evolving, struggling organisms. And it takes the occasional plant monster to remind us every so often. Has the final plant monster story been written? I hardly think so. Like dandelions springing up on your lawn, the plant monster isn't going anywhere soon. Check out the database at gwthomas.org.

I haven't gone into a lot of TV or movies here, and no comics at all (for the comics always followed, never setting trends), because there simply isn't room. The only video productions that had anything really new to add were the Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), especially the musical version in 1986. "Feed me, Seymour!" the bulbous Audrey II cries, and in that moment, as the large-toothed mouth hovers over the insignificant Seymour Krelboyne, the final version of the plant monster has arrived at last. For every twelve-year-old kid who bought a Venus Flytrap to feed flies to, for every hunter lost in the bush, feeling like the forest was his living antagonist, for every allergy sufferer (I feel your pain!), here is the image of plant as hostile. We forget that they too are living, moving, evolving, struggling organisms. And it takes the occasional plant monster to remind us every so often. Has the final plant monster story been written? I hardly think so. Like dandelions springing up on your lawn, the plant monster isn't going anywhere soon. Check out the database at gwthomas.org.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

The first stories of killer plants were written by two Americans. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote "Rappacini's Daughter" in 1844 and showed us that a father's wish to protect his daughter's virtue can become almost pathological. Rappacini infuses the girl with plant poison, making her the precursor of Batman's Poison Ivy. The second story was twenty-five years later and written by the mother of the American family story, Lousia May Alcott, who penned Little Women (1868). Her story has the Gothic title of "Lost in a Pyramid, or the Mummy's Curse" and is the first real killer flower story. Seeds from a mummy's treasure grow into a large blossomed plant. When worn, the flower sucks the vitality from the wearer.