Michael May's Blog, page 121

December 15, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Jim Carrey (2009)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Robert Zemeckis' Christmas Carol also skips dinner. It goes straight from Cratchit's sliding adventure to Scrooge's arrival at home. I suppose it's a comparison between the joyful frivolity of the sliders (though everything looks gloomy in this movie so far) and the silent solitude of Scrooge's walk. Like in a couple of other versions we've looked at, there are no other people on the streets in Scrooge's part of town.

His house is a large mansion that stands tall and lonely, separated from the world by a large, brick wall. The ponderous, black, iron gate sounds like prison when Scrooge closes it behind himself. I don't imagine that Scrooge shares this building even with business offices. The whole point of the place is to show how cut off and isolated he is.

Published on December 15, 2015 04:00

December 14, 2015

Espers in Space: Edmond Hamilton's Legion of Lazarus [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

The 1950s was an odd time for Science Fiction. After decades of robots and space travel and time machines and external battles, the struggles went inward. Whether you called them psionics, or espers, or any other version of telepaths, SF became about men who fought with their minds. (The other big theme in the 1950s was flying saucers.)

The 1950s was an odd time for Science Fiction. After decades of robots and space travel and time machines and external battles, the struggles went inward. Whether you called them psionics, or espers, or any other version of telepaths, SF became about men who fought with their minds. (The other big theme in the 1950s was flying saucers.)

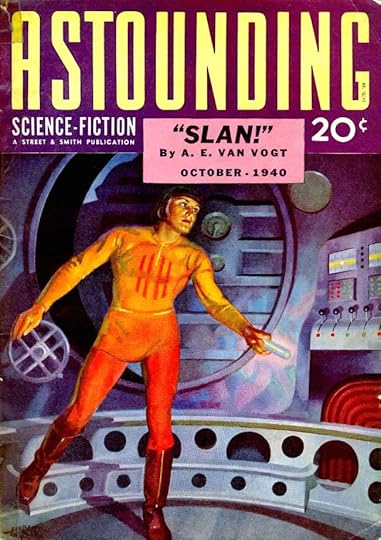

The most powerful editor in SF was John W Campbell and he lead the charge on Psionics, publishing AE van Vogt's Slan in 1946, and even writing non-fiction articles on mental powers. Astounding became the focal point for psi-fiction as well as other unusual ideas like the Dean Drive. (Life even imitated art as L Ron Hubbard sold a mental SF idea to the masses as a new Science called Dianetics (Astounding, May 1950) and later as a religion that survives today as Scientology.) Readers had become obsessed with the idea of using their minds to do fantastic things.

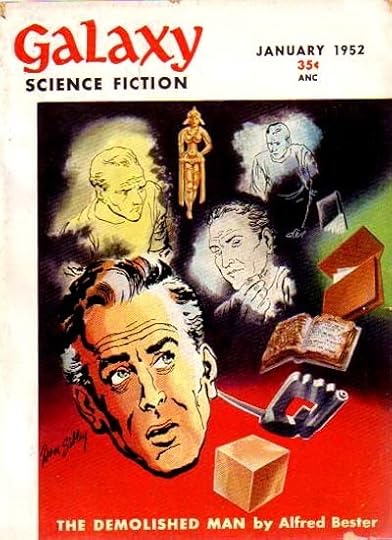

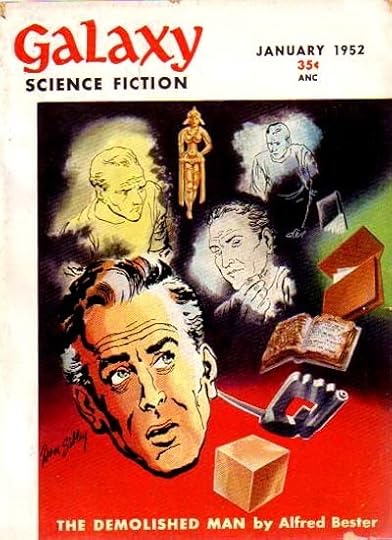

The classic 1950s psi novel is usually identified as The Demolished Man (1952) by Alfred Bester. Bester wrote the serial for HL Gold at Galaxy, not Campbell. Many decades later Michael J Straczynski honored Bester's contribution by giving his leader of the Psi Police on Babylon 5 the name "Bester" (played by Walter Koenig of Star Trek fame).

The classic 1950s psi novel is usually identified as The Demolished Man (1952) by Alfred Bester. Bester wrote the serial for HL Gold at Galaxy, not Campbell. Many decades later Michael J Straczynski honored Bester's contribution by giving his leader of the Psi Police on Babylon 5 the name "Bester" (played by Walter Koenig of Star Trek fame).

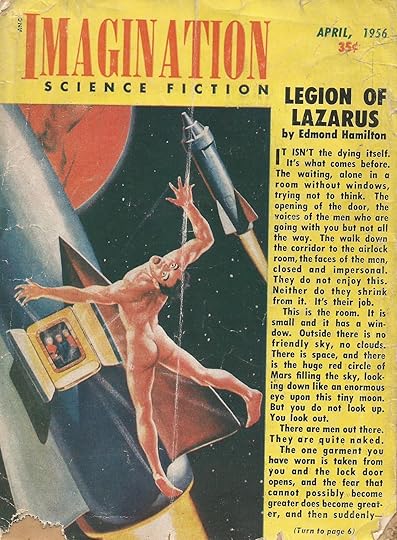

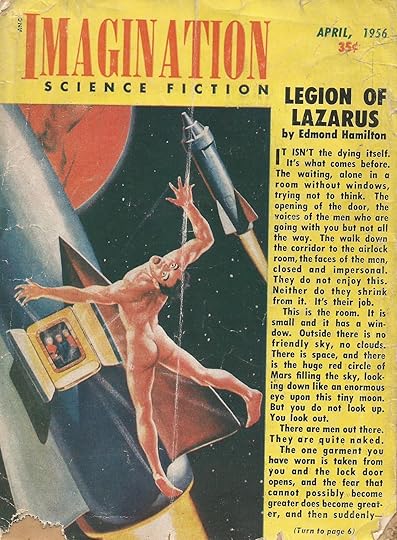

But Astounding and Galaxy weren't the only magazines using espers. One of my favorite esper tales was written by Edmond Hamilton for Imagination in April 1956, entitled "The Legion of Lazarus." This 21,000 word novella was written for Ray Palmer (the editor that virtually invented the UFO craze) and its appearance in Imagination was not considered a prestigious event. Hamilton's reputation had lost much of its shine by 1956. He spent most of his time writing Batman and Superman comics for DC. Before that he had written the juvenile series Captain Future for Mort Weisinger (who would later go into comics at DC as well). When Hamilton did write SF in the 1950s he was doing some of his very best work (largely unappreciated) in novellas for Palmer. "The Legion of Lazarus" belongs to this part of his career.

The short novel begins with the idea of a humane penalty for murderers. Rather than kill them, they are put in suspended animation for fifty years. The only problem is this process changes them into espers. Hyrst wakes from his wrongful conviction to find himself in the middle of a power struggle, with Lazarites (his word for espers) in the thick of things. The crime for which Hyrst was put to sleep involved a mining operation on Titan. There, one of his colleagues named MacDonald had stumbled upon a cosmic treasure, a lump of Titanite, a power source so precious it would make him fabulously rich. MacDonald is murdered, the Titanite disappears, and Hyrst is convicted of his death.

The short novel begins with the idea of a humane penalty for murderers. Rather than kill them, they are put in suspended animation for fifty years. The only problem is this process changes them into espers. Hyrst wakes from his wrongful conviction to find himself in the middle of a power struggle, with Lazarites (his word for espers) in the thick of things. The crime for which Hyrst was put to sleep involved a mining operation on Titan. There, one of his colleagues named MacDonald had stumbled upon a cosmic treasure, a lump of Titanite, a power source so precious it would make him fabulously rich. MacDonald is murdered, the Titanite disappears, and Hyrst is convicted of his death.

The plot follows Hyrst's joining the Lazarites, defying Mr Bellaver, the grandson of the rich man who engineered his arrest, and the creation of an intergalactic spaceship. The Lazarites want the Titanite to power their ship to freedom while Bellaver and his goons want only riches. Both sides want Hyrst to tell them where he hid the Titanite, but Hyrst is innocent. All Hyrst wants is the man who killed MacDonald and to clear his name. The final product is a fast-moving tale (with a chase through the asteroids right out of a Star Wars movie!) with ESP and a mystery and a puzzle to solve. Only Edmond Hamilton could write an esper tale that was also first class space opera. (The Demolished Man author, Alfred Bester attempted this type of adventure-oriented SF in The Stars My Destination, but he lacks Hamilton's verve. I found that novel tedious by comparison, it being based on Alexandre Dumas's The Count of Monte Cristo.)

And that's why "The Legion of Lazarus" is my favorite ESP tale, at least up to 1956. It's not dull. The regular Astounding tale reads like one of Campbell's non-fiction articles. The Galaxy stories, like The Demolished Man, are better, but still focused on sociology or humor first. Only a magazine like Imagination, which had no illusions about winning any Hugo Awards, could have published "The Legion of Lazarus." Ray Palmer wanted excitement as well as ideas.

And that's why "The Legion of Lazarus" is my favorite ESP tale, at least up to 1956. It's not dull. The regular Astounding tale reads like one of Campbell's non-fiction articles. The Galaxy stories, like The Demolished Man, are better, but still focused on sociology or humor first. Only a magazine like Imagination, which had no illusions about winning any Hugo Awards, could have published "The Legion of Lazarus." Ray Palmer wanted excitement as well as ideas.

ESP stories after the 1950s have their own later classics. Robert Silverberg's Dying Inside (1973) or George RR Martin's Dying of the Light (1977) both emphasize the cost of having a gift and the price the protagonist has to pay for the ability. Any idea of a fast-paced ESP tale would have to wait for the movies, in cheesy series like Scanners. Perhaps a better legacy is Star Trek: Nemesis (2002) and the character of Viceroy played by Ron Perlman, an Esper who uses his gift to do harm. Here is a film that Hamilton might have seen a glimmer of "The Legion of Lazarus" in.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

The 1950s was an odd time for Science Fiction. After decades of robots and space travel and time machines and external battles, the struggles went inward. Whether you called them psionics, or espers, or any other version of telepaths, SF became about men who fought with their minds. (The other big theme in the 1950s was flying saucers.)

The 1950s was an odd time for Science Fiction. After decades of robots and space travel and time machines and external battles, the struggles went inward. Whether you called them psionics, or espers, or any other version of telepaths, SF became about men who fought with their minds. (The other big theme in the 1950s was flying saucers.)The most powerful editor in SF was John W Campbell and he lead the charge on Psionics, publishing AE van Vogt's Slan in 1946, and even writing non-fiction articles on mental powers. Astounding became the focal point for psi-fiction as well as other unusual ideas like the Dean Drive. (Life even imitated art as L Ron Hubbard sold a mental SF idea to the masses as a new Science called Dianetics (Astounding, May 1950) and later as a religion that survives today as Scientology.) Readers had become obsessed with the idea of using their minds to do fantastic things.

The classic 1950s psi novel is usually identified as The Demolished Man (1952) by Alfred Bester. Bester wrote the serial for HL Gold at Galaxy, not Campbell. Many decades later Michael J Straczynski honored Bester's contribution by giving his leader of the Psi Police on Babylon 5 the name "Bester" (played by Walter Koenig of Star Trek fame).

The classic 1950s psi novel is usually identified as The Demolished Man (1952) by Alfred Bester. Bester wrote the serial for HL Gold at Galaxy, not Campbell. Many decades later Michael J Straczynski honored Bester's contribution by giving his leader of the Psi Police on Babylon 5 the name "Bester" (played by Walter Koenig of Star Trek fame).But Astounding and Galaxy weren't the only magazines using espers. One of my favorite esper tales was written by Edmond Hamilton for Imagination in April 1956, entitled "The Legion of Lazarus." This 21,000 word novella was written for Ray Palmer (the editor that virtually invented the UFO craze) and its appearance in Imagination was not considered a prestigious event. Hamilton's reputation had lost much of its shine by 1956. He spent most of his time writing Batman and Superman comics for DC. Before that he had written the juvenile series Captain Future for Mort Weisinger (who would later go into comics at DC as well). When Hamilton did write SF in the 1950s he was doing some of his very best work (largely unappreciated) in novellas for Palmer. "The Legion of Lazarus" belongs to this part of his career.

The short novel begins with the idea of a humane penalty for murderers. Rather than kill them, they are put in suspended animation for fifty years. The only problem is this process changes them into espers. Hyrst wakes from his wrongful conviction to find himself in the middle of a power struggle, with Lazarites (his word for espers) in the thick of things. The crime for which Hyrst was put to sleep involved a mining operation on Titan. There, one of his colleagues named MacDonald had stumbled upon a cosmic treasure, a lump of Titanite, a power source so precious it would make him fabulously rich. MacDonald is murdered, the Titanite disappears, and Hyrst is convicted of his death.

The short novel begins with the idea of a humane penalty for murderers. Rather than kill them, they are put in suspended animation for fifty years. The only problem is this process changes them into espers. Hyrst wakes from his wrongful conviction to find himself in the middle of a power struggle, with Lazarites (his word for espers) in the thick of things. The crime for which Hyrst was put to sleep involved a mining operation on Titan. There, one of his colleagues named MacDonald had stumbled upon a cosmic treasure, a lump of Titanite, a power source so precious it would make him fabulously rich. MacDonald is murdered, the Titanite disappears, and Hyrst is convicted of his death.The plot follows Hyrst's joining the Lazarites, defying Mr Bellaver, the grandson of the rich man who engineered his arrest, and the creation of an intergalactic spaceship. The Lazarites want the Titanite to power their ship to freedom while Bellaver and his goons want only riches. Both sides want Hyrst to tell them where he hid the Titanite, but Hyrst is innocent. All Hyrst wants is the man who killed MacDonald and to clear his name. The final product is a fast-moving tale (with a chase through the asteroids right out of a Star Wars movie!) with ESP and a mystery and a puzzle to solve. Only Edmond Hamilton could write an esper tale that was also first class space opera. (The Demolished Man author, Alfred Bester attempted this type of adventure-oriented SF in The Stars My Destination, but he lacks Hamilton's verve. I found that novel tedious by comparison, it being based on Alexandre Dumas's The Count of Monte Cristo.)

And that's why "The Legion of Lazarus" is my favorite ESP tale, at least up to 1956. It's not dull. The regular Astounding tale reads like one of Campbell's non-fiction articles. The Galaxy stories, like The Demolished Man, are better, but still focused on sociology or humor first. Only a magazine like Imagination, which had no illusions about winning any Hugo Awards, could have published "The Legion of Lazarus." Ray Palmer wanted excitement as well as ideas.

And that's why "The Legion of Lazarus" is my favorite ESP tale, at least up to 1956. It's not dull. The regular Astounding tale reads like one of Campbell's non-fiction articles. The Galaxy stories, like The Demolished Man, are better, but still focused on sociology or humor first. Only a magazine like Imagination, which had no illusions about winning any Hugo Awards, could have published "The Legion of Lazarus." Ray Palmer wanted excitement as well as ideas.ESP stories after the 1950s have their own later classics. Robert Silverberg's Dying Inside (1973) or George RR Martin's Dying of the Light (1977) both emphasize the cost of having a gift and the price the protagonist has to pay for the ability. Any idea of a fast-paced ESP tale would have to wait for the movies, in cheesy series like Scanners. Perhaps a better legacy is Star Trek: Nemesis (2002) and the character of Viceroy played by Ron Perlman, an Esper who uses his gift to do harm. Here is a film that Hamilton might have seen a glimmer of "The Legion of Lazarus" in.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on December 14, 2015 16:00

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Scrooge McDuck (1983)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Mickey's Christmas Carol all but eliminates this scene, but still brings in the melancholy aspect nicely. Cratchit goes home and leaves Scrooge alone at his desk until a slow dissolve brings a clock chiming nine o'clock. That's when Scrooge finally leaves the office, but the streets are empty now. Everyone is home and Scrooge only has the sound of a mournful oboe in the score to keep him company. He doesn't stop for dinner and the streets are still abandoned when he gets home.

His house is right on the sidewalk and well lit by a street lamp. Quite the opposite of the withdrawn location that Dickens described. As we'll see on Christmas morning, it gets a lot of activity in front of it during the day. None of that matters right now though. The fresh heaped snow, the gloomy lighting, and the music all make Scrooge and his house plenty sad and lonely.

Published on December 14, 2015 04:00

December 13, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Walter Matthau (1978)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

After Cratchit leaves the office, Scrooge sticks around to put away the day's earnings. Shaking the container of coins, he thinks it sounds a little light and vows to dock Cratchit for anything that's missing. Tom Bosley's Humbug, who's also stayed behind, gets irritated at this and launches into the show's title song.

The show uses "The Stingiest Man in Town" the way The Muppet Christmas Carol uses "Scrooge" earlier in its storyline. As Scrooge makes his way through the city, townspeople (and animals) sing about what a horrible person he is. And it's reinforced by scenes of his acting out his greediness, cheating and tricking street vendors into giving him free stuff. He does stop in a tavern for dinner, but his newspaper is taken from a trashcan and he stiffs his server on the tip. It's not all that melancholy, but remember that this Scrooge isn't especially sad. He's just mean and wrong.

Here are the lyrics and you can watch the video below:

How can anybody be so stingy?

So stingy, so stingy?

How could anybody be so stingy?

He's the stingiest man in town.

Old Scrooge is such a stingy man

The tightest man since time began.

Oh, he's so tight, so tight I say

He wouldn't give a bride away.

It hurts him so to pay one cent,

He wouldn't pay a compliment,

He uses lightning bugs at night,

To save the cash he'd pay for light!

How can anybody be so stingy?

So stingy, so stingy?

How could anybody be so stingy?

He's the stingiest man in town.

When he goes by the children hiss.

No other man is tight as this.

One day he skinned an alley cat

To make himself a winter hat.

He has a house that's very tall,

With flowered paper in the hall.

And for his mother's funeral,

He cut the flowers off the wall.

How can anybody be so stingy?

So stingy, so stingy?

How could anybody be so stingy?

He's the stingiest man in town.

And when his hearse goes rolling by.

No man alive is gonna cry.

But you can bet his ghost will curse,

Because he's paying for the hearse.

And when it's time for him to go,

His soul will travel down below,

And when he gets there you can tell,

Because you'll hear old Satan yell...

How can anybody be so stingy?

So stingy, so stingy?

How could anybody be so stingy?

He's the stingiest man in town.

The Rankin-Bass cartoon is adapted from a live-action musical special that had aired in 1956 on the NBC anthology show The Alcoa Hour. It starred Basil Rathbone as Scrooge and I just watched it for the first time last year. It's good, but I'm too far into this project to want to try to squeeze it in and catch it up to the other versions. Still, for fun, here's the original version of the song. As you can see, it takes a mocking tone towards Scrooge instead of the righteous indignation of the cartoon.

Back to the cartoon, the scene ends with Scrooge's arrival at home. It doesn't bear much resemblance to the one Dickens describes. It's pretty much just a dark townhouse on a block of similar townhouses. There's a little iron fence around a small yard in front, but nothing about it feels secluded.

The scene does turn spooky though as Humbug narrates, saying that "there was something strange about that night" and suggesting that it was supernaturally dark. He paraphrases Dickens' line about the Genius of the Weather sitting in mournful meditation on the threshold, but changes the personification to Death, foreshadowing the ghostly events that are about to take place.

Published on December 13, 2015 04:00

December 10, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Alastair Sim (1971)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Richard Williams' animated version also skips dinner, but uses Scrooge's journey home to sneak in some Michael Redgrave narration that Dickens had placed earlier in the story. Specifically, it's the bit about blind men's dogs that would cross the street instead of bringing their masters into Scrooge's vicinity. Williams shows us one such encounter, but the rest of the walk home is done impressionistically in only a couple of shots.

In the first, there's a sketched out street - very grim and murky - with the small, lone figure of Scrooge walking in the background. The second shot has a more distinct Scrooge walking through an empty background that represents fog, with only a hazy spot of light to suggest a window or a lantern. The film goes straight from this nondescript background to Scrooge's door, so there are no details about what Scrooge's house looks like, but the melancholy of Scrooge's situation is very clear.

Published on December 10, 2015 04:00

December 8, 2015

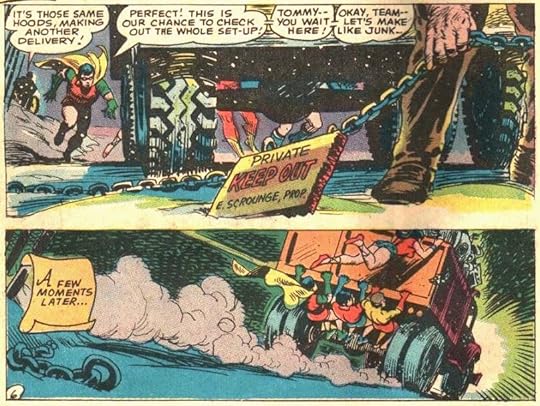

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Teen Titans #13 (1968)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

I covered way too much of this version in the first year of the project, so it's still waiting for us to catch up. Next year we'll have some new stuff to say about it, but in the meantime, here's the Teen Titans investigating the goings on at Scrounge's junkyard.

Published on December 08, 2015 16:00

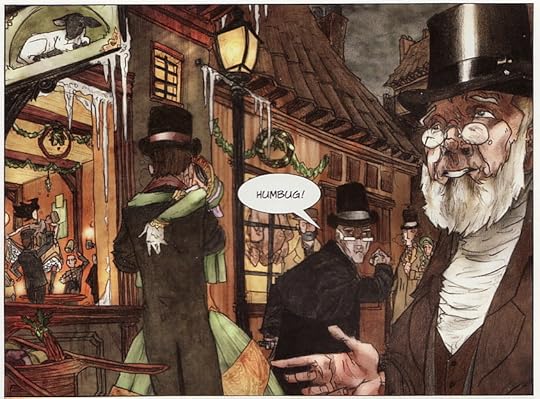

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Graphic Classics, Volume 19: Christmas Classics (2010)

Alex Burrows and Micah Farritor's version is sort of the opposite of the old Classics Illustrated version. Classics Illustrated relies heavily on text, so the drawings serve more like illustrations than true, comics storytelling. I guess that's fair considering the name of the comic. But Burrows and Farritor take the opposite approach, letting the drawings do a lot of the work.

Take this year's scene for instance. It cuts out the dinner part and just follows Scrooge home, but there's no caption to give us the history of his house or who else does or doesn't live there. And honestly, the story doesn't need it. That stuff is flavor, but Burrows and Farritor are challenged with adapting the tale in very few pages and I like their choice of focusing on the mood and the major story beats instead of Dickens' details.

Like Classics Illustrated though, Graphic Classics uses the scene to remind us how Scrooge feels about Christmas. Farritor draws a lovely panel in which Scrooge is surrounded by Christmas celebrants shopping, partying, and smooching in the road, surrounded by holly and greenery. Christmas is in full force, but Scrooge is having none of it. He's raising one arm as if to strike someone who isn't there and he's frowning as he says, "Humbug." He's not sneering about it though like he was in the office. Possibly that's because no one's paying any attention to him now. Scrooge's hatred of Christmas is genuine, but he might play it up more when he knows he can get a rise out of someone.

The only other panel between Scrooge's office and the supernatural door-knocker has Scrooge standing on the front steps of his place. He's about to go in and we get a quick, closely cropped look at the house. It's colored in a dreary brown and there are mud puddles on the ground and dangerous-looking icicles hanging all over the place. It looks plenty lonely and spooky without a single word of text.

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Published on December 08, 2015 04:00

December 5, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Campfire’s A Christmas Carol (2010)

Scott McCullar and Naresh Kumar condense our scene into a single panel. There's no mention of dinner, but the word "melancholy" is kept to describe Scrooge's walk home.

The description of the house is bare, too, saying only that Scrooge lives in the building alone. There's nothing about Marley and the text implies that Scrooge has the whole place to himself. Neither of those are bad things, though. So many adaptations suggest that Scrooge owns the whole building that I'm comfortable with that.

It's a little hard to decipher the depth of the yard in Kumar's drawing. We're quite close to that lantern and the wall behind it also looks near. But the gate on the left looks farther back and I can't tell how close it is to the house. I do like the lines suggesting sleet and wind though and Anil CK's colors are nice, putting Scrooge back in the cold, removed from the soft lantern light.

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Published on December 05, 2015 04:00

December 4, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | A Christmas Carol: The Graphic Novel (2008)

Sean Michael Wilson and Mike Collins' version uses four panels to show us this scene. The first has Scrooge in the tavern, which - in spite of the caption box that tells us it's melancholy - has a warm, homey glow to it. The patrons are dour enough though, silently staring into their drinks with hats pulled down to conceal their eyes in shadow. In the background, separated from the others, Scrooge quietly accepts a plate from the tavern keeper.

The next two panels show Scrooge on his way home and we get a look at his house, mostly dark and forbidding except for that warm lantern glow that colorist James Offredi keeps including. It's a nice effect; it just doesn't fit the tone the story needs right there. I love Collins' work and especially David Roach's inks in these two panels. Scrooge is dramatic against the backgrounds and I get a great sense of Scrooge's solitude and the spookiness of the scene. I also like how Collins surrounds the house with other architecture. It feels much more claustrophobic than the Marvel version.

The final panel, with a caption about how Scrooge's chambers formerly belonging to Marley (but no mention of the rented offices), has Scrooge at the front door with the famous knocker, foreshadowing what's about to happen.

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Published on December 04, 2015 04:00

December 3, 2015

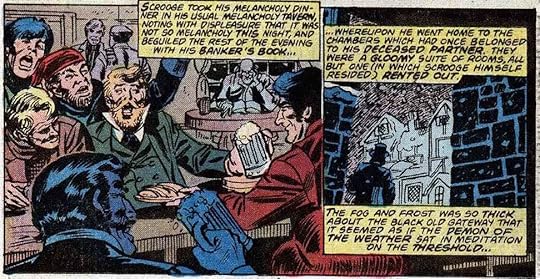

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Marvel Classic Comics #36 (1978)

Marvel's version makes a bold choice and has the tavern being not melancholy at all. On the surface, this seems like an obvious fix of Dickens' text. Of course there would be Christmas celebrants at a gathering place. But places have character just like people do and this being Scrooge's "usual melancholy tavern," I expect that part of the reason he frequents there is that there's something about the place that discourages festivity. There's an interesting story behind why the place wouldn't be celebrating Christmas; Dickens just isn't telling us what it is.

But Marvel's not wrong for giving a different take. There's also a deeper story behind why this group of merrymakers chose to invade this particular tavern; Marvel just isn't telling us what it is. But it adds some fun irony to the word "usual" and highlights how withdrawn and pathetic Scrooge is as he sulks and reads in the background. Coloring him a cold blue helps with this, too.

Like Classics Illustrated, Marvel also mentions that Scrooge's home used to belong to Marley. It adds the detail that the other rooms in the house have been rented out, but omits the part about their being offices.

The art does a nice job of communicating the dreariness and seclusion of the place. It's colored in the same cold blue that Scrooge was in the previous panel. The dark, looming gateway in the foreground creates space between it and the distant house. It's a more open space than I imagine when I read Dickens though and gives the impression of a once luxurious mansion. I've always pictured the house being at the end of a long alley and closely surrounded by other buildings. But I don't want to read too much into this one, small panel. It's hard to tell much about the house and its grounds from the angle of the drawing.

Published on December 03, 2015 04:00