Michael May's Blog, page 120

December 25, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Patrick Stewart (1999)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Merry Christmas, everyone!

The TNT version of this scene is anti-climactic for this year's study, because it's just Scrooge walking the final steps to his front door. And the set is even similar to the one from The Muppet Christmas Carol, with Scrooge's entering from a small alley that widens into a courtyard with several buildings around. It's a great set up, it's just not new. Nor is anything else about the shot. It's very functional, only meant to lead into next year's scene.

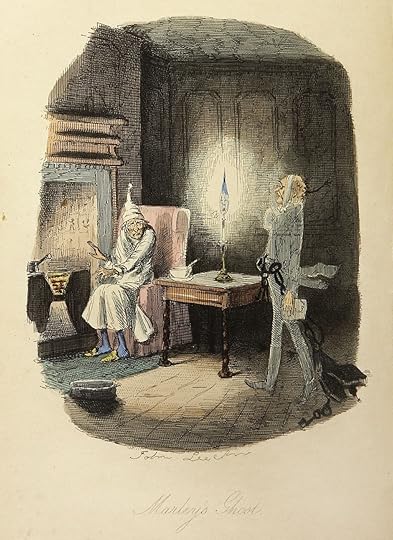

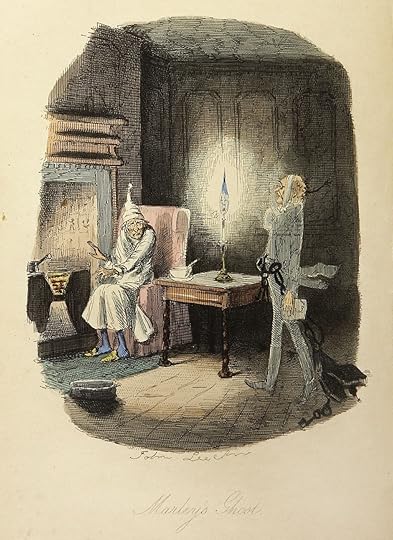

Thanks for joining me! I know this year's scene was light, but as I said in the comments to an early entry, I was happy for an easy one after all the time I spent on Bond this year. And next year's should be quite in depth as we finally visit with Marley's Ghost.

I'm going to take next week off except for at least one guest post by GW Thomas. Gotta get rested up for January's big countdown of 2015 movies. See you next year!

Published on December 25, 2015 04:00

December 24, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Michael Caine (1992)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

The Muppets reduce our scene to a single shot of the courtyard outside Scrooge's house. Gonzo and Rizzo pull up in a carriage and Gonzo narrates as Scrooge enters from a narrow alley and goes to his door. Gonzo differs from Dickens slightly, mixing the author's description of the house with earlier stuff about Marley's (or in this case, the Marleys') existential state.

"Scrooge lived in chambers which had once belonged to his old business partners Jacob and Robert Marley. The building was a dismal heap of brick on a dark street. Now, once again I must ask you to remember that the Marleys were dead and decaying in their graves. That one thing you must remember, or nothing that follows will seem wondrous."

Nothing new there, but Gonzo does it in a hushed tone (something that Rizzo comments on) to add to the spookiness and build suspense for what's about to happen.

Published on December 24, 2015 16:00

Ghosts at Christmas: Dickens to Davies [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

Charles Dickens gets the credit for the idea of a ghost story at Christmas. We all know Scrooge, whether it's Alastair Sim, Bill Murray, Patrick Stewart, or Fred Flintstone. The only problem is that Dickens didn't invent it. I would even go so far as to say he tried to hi-jack the idea and turn it to his own purposes: making money and instruction. I could be wrong. But Dickens wouldn't be the first person to realize that Christmas is a cash cow.

Charles Dickens gets the credit for the idea of a ghost story at Christmas. We all know Scrooge, whether it's Alastair Sim, Bill Murray, Patrick Stewart, or Fred Flintstone. The only problem is that Dickens didn't invent it. I would even go so far as to say he tried to hi-jack the idea and turn it to his own purposes: making money and instruction. I could be wrong. But Dickens wouldn't be the first person to realize that Christmas is a cash cow.

The telling of a winter's tale, a gory or fantastic story around a merry fire in the depths of the dark, cold season, is as old at least as Shakespeare. He couldn't have written the play The Winter's Tale (1623) if it had not existed. By it's very title, we know the story will not be realistic and offer a happy ending. But old Willy didn't invent it either. The tradition goes back into time wherever there were people living in northern climes and had some form of forced inactivity imposed on them. The last remnants of this tradition in North America is the campfire tale that is so often featured in movies, just before the madman starts cutting up teenagers.

So it's been around awhile. The Christmas version is usually told by a grandmother or a trusted nurse, the tale having a homely feel, but a cold shiver as its ultimate goal. It should be no surprise that Elizabeth Gaskell wrote "The Old Nurse's Tale"(1852), one of my favorite Christmas tales. The author of Cranford (1851) was doing what many women Victorian writers did, penning a ghost story for Christmas (and some holiday cash). Many of these stories were published by Mr. Dickens in his Christmas numbers of Household Words and All the Year Round. In this way Dickens did contribute to the popularity of Christmas ghosts over and beyond Tiny Tim and Jacob Marley. Fortunately for us, these tales take after Dickens' "The Signal-Man"(1866) more than A Christmas Carol (1843). For this was Dickens' other fault besides wanting to sell a lot of copies of a magazine (a sin I understand only too well): his ghosts tend to be lessons or morals dressed up in chains. A Christmas Carol rises above the lecturing because it is so entertaining and it has creepy ghosts. Other Dickens' Christmas stories such as "The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain" (1848), "Baron Koeldwethout's Apparation" (1838), "A Child's Dream of a Star" (1850), and "The Last Words of the Old Year" (1851) are all heavy on message and light on supernatural thrills.

So it's been around awhile. The Christmas version is usually told by a grandmother or a trusted nurse, the tale having a homely feel, but a cold shiver as its ultimate goal. It should be no surprise that Elizabeth Gaskell wrote "The Old Nurse's Tale"(1852), one of my favorite Christmas tales. The author of Cranford (1851) was doing what many women Victorian writers did, penning a ghost story for Christmas (and some holiday cash). Many of these stories were published by Mr. Dickens in his Christmas numbers of Household Words and All the Year Round. In this way Dickens did contribute to the popularity of Christmas ghosts over and beyond Tiny Tim and Jacob Marley. Fortunately for us, these tales take after Dickens' "The Signal-Man"(1866) more than A Christmas Carol (1843). For this was Dickens' other fault besides wanting to sell a lot of copies of a magazine (a sin I understand only too well): his ghosts tend to be lessons or morals dressed up in chains. A Christmas Carol rises above the lecturing because it is so entertaining and it has creepy ghosts. Other Dickens' Christmas stories such as "The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain" (1848), "Baron Koeldwethout's Apparation" (1838), "A Child's Dream of a Star" (1850), and "The Last Words of the Old Year" (1851) are all heavy on message and light on supernatural thrills.

Dickens was the promoter of Christmas and ghosts, but fortunately the man they all turned to for inspiration was J Sheridan Le Fanu. Le Fanu's many ghost stories set the holiday scribes on the right path. "Madam Crowl's Ghost," "The Child Who Went With the Fairies," "The White Cat of Drumgunniol," "Sir Dominick's Bargain," "The Vision of Tom Chuff," and "Stories of Lough Guir" all appeared in Dickens' All the Year Round, usually around December. Others appeared in Le Fanu's Dublin University Magazine. Le Fanu, despite seeing himself as a serious historical novelist, is largely remembered for these and other ghost and mystery stories. The Irish writer drew upon the tales of his country for inspiration, and why not? The winter tale is related to "Marchen" or fairy tales, both being part of the oral tradition of storytelling.

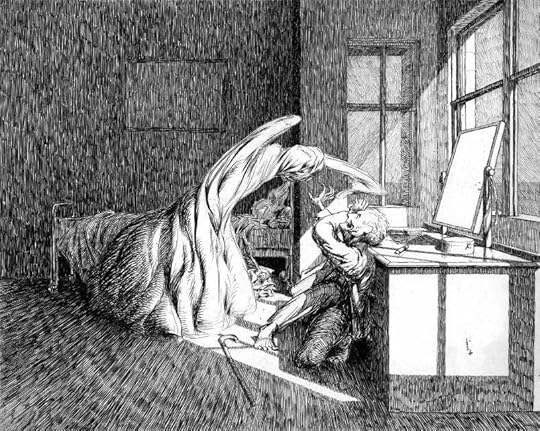

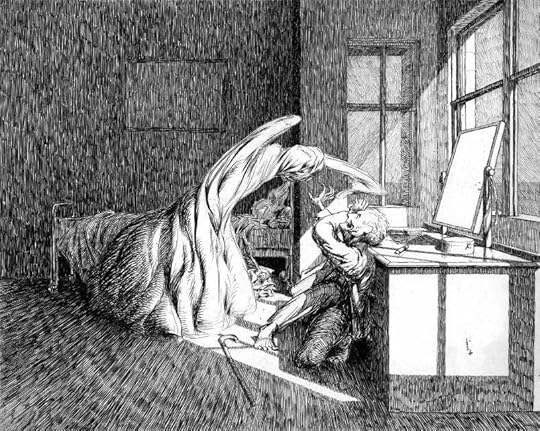

The greatest ghost story writer of them all (my opinion, but many would agree) was Le Fanu's disciple, MR James. The Cambridge and Eton don wrote an annual Christmas story and shared it with students and friends. These yearly treats were much looked forward to and there was even a little prestige in being including in such a reading. The thirty-three stories that James produced over the decades are sterling examples of what a ghost story can and should do. Classics like "Casting the Runes," "Count Magnus," "The Ash Tree," "Canon Alberic's Scrapbook," and "Lost Hearts" all begin quietly, usually about an amateur antiquarian on a holiday, but end with a glimpse into the cold netherworlds that lurk near by. James' ghosts are never fun, kind, or even well-defined. They are truly terrible, half-glimpsed, and cruel. How Christmasy!

The greatest ghost story writer of them all (my opinion, but many would agree) was Le Fanu's disciple, MR James. The Cambridge and Eton don wrote an annual Christmas story and shared it with students and friends. These yearly treats were much looked forward to and there was even a little prestige in being including in such a reading. The thirty-three stories that James produced over the decades are sterling examples of what a ghost story can and should do. Classics like "Casting the Runes," "Count Magnus," "The Ash Tree," "Canon Alberic's Scrapbook," and "Lost Hearts" all begin quietly, usually about an amateur antiquarian on a holiday, but end with a glimpse into the cold netherworlds that lurk near by. James' ghosts are never fun, kind, or even well-defined. They are truly terrible, half-glimpsed, and cruel. How Christmasy!

"Christmasy?" you ask. Yes, of course. The shiver that goes down your spine after a truly effective ghost story is not so much different than the feeling of outré joy that the story of Jesus's birth inspires in Christians. In a way, the whole purpose of the Christmas ghost story is to jump-start your sense of the impossible, a faculty that becomes atrophied after months of going to work, enduring the hum-drum tedium that is life. Here is a small dose of Something Greater. Dickens tried in several stories to create this jump-start from a happy place. He fails. James and his wicked spirits never do.

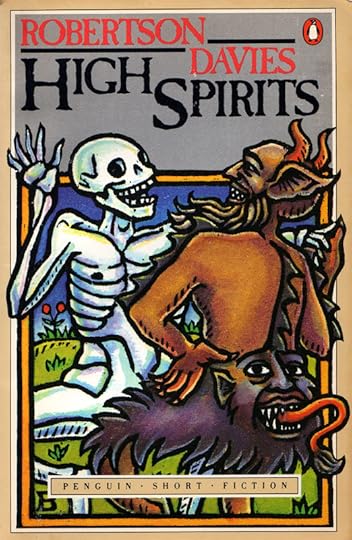

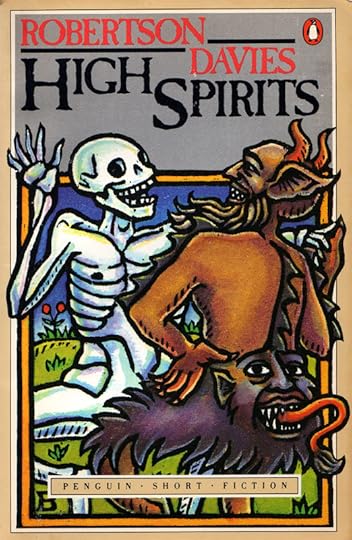

I understand that the idea of a scary story at Christmas is hard to understand today. I live in Canada, perhaps the most realistic country in the world. We get White Christmases, but not ghostly ones. Robertson Davies, the Canadian author, defined it as "the rational rickets." We are so depleted of fantastic imagination, we think men chasing a small black dot around on ice is fun. (Beer helps.) Despite this, Davies wrote his own book of Canadian Christmas ghosts called High Spirits (1982). It is surprising that the deft wordsmith does not reach for the black depths of MR James (who inspired Davies to tell an annual tale for the enjoyment of his college buddies), but Davies' ghosts are enchanting and humorous. As the title implies, jocularity is the key. Ghosts like "The Ghost Who Vanished By Degrees," the grad student who never received his Masters and PhD and the only way Davies can lay him to rest is to give him more and more degrees. The titles are suggestive: "The Ugly Spectre of Sexism," "The Refuge of Insulted Saints," "The Xerox in the Lost Room," and "Dickens Digested." Davies' ghosts take after the stories of J Kendrick Bangs' "Told After Supper" (1891). If you can't quite manage horrific ghosts this Yuletide, I would suggest Davies or Bangs.

I understand that the idea of a scary story at Christmas is hard to understand today. I live in Canada, perhaps the most realistic country in the world. We get White Christmases, but not ghostly ones. Robertson Davies, the Canadian author, defined it as "the rational rickets." We are so depleted of fantastic imagination, we think men chasing a small black dot around on ice is fun. (Beer helps.) Despite this, Davies wrote his own book of Canadian Christmas ghosts called High Spirits (1982). It is surprising that the deft wordsmith does not reach for the black depths of MR James (who inspired Davies to tell an annual tale for the enjoyment of his college buddies), but Davies' ghosts are enchanting and humorous. As the title implies, jocularity is the key. Ghosts like "The Ghost Who Vanished By Degrees," the grad student who never received his Masters and PhD and the only way Davies can lay him to rest is to give him more and more degrees. The titles are suggestive: "The Ugly Spectre of Sexism," "The Refuge of Insulted Saints," "The Xerox in the Lost Room," and "Dickens Digested." Davies' ghosts take after the stories of J Kendrick Bangs' "Told After Supper" (1891). If you can't quite manage horrific ghosts this Yuletide, I would suggest Davies or Bangs.

Me? I'll stick to the harder stuff. Perhaps a little Algernon Blackwood, who used to read his stories at Christmas on the BBC. Feeling Victorian? Then there is no better place to go than the Gaslight website. Like a mix of Radio and print? Then the Amalgamated Brotherhood of Spooks will do.

One last suggestion: if you'd like a taste of MR James, try Mark Gatiss's BBC TV version of "The Tractate Middoth" and his documentary about James. And if you catch the mood, there is a collection of MR James BBC shows.

Happy holidays and enjoy the ghosts!

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Charles Dickens gets the credit for the idea of a ghost story at Christmas. We all know Scrooge, whether it's Alastair Sim, Bill Murray, Patrick Stewart, or Fred Flintstone. The only problem is that Dickens didn't invent it. I would even go so far as to say he tried to hi-jack the idea and turn it to his own purposes: making money and instruction. I could be wrong. But Dickens wouldn't be the first person to realize that Christmas is a cash cow.

Charles Dickens gets the credit for the idea of a ghost story at Christmas. We all know Scrooge, whether it's Alastair Sim, Bill Murray, Patrick Stewart, or Fred Flintstone. The only problem is that Dickens didn't invent it. I would even go so far as to say he tried to hi-jack the idea and turn it to his own purposes: making money and instruction. I could be wrong. But Dickens wouldn't be the first person to realize that Christmas is a cash cow.The telling of a winter's tale, a gory or fantastic story around a merry fire in the depths of the dark, cold season, is as old at least as Shakespeare. He couldn't have written the play The Winter's Tale (1623) if it had not existed. By it's very title, we know the story will not be realistic and offer a happy ending. But old Willy didn't invent it either. The tradition goes back into time wherever there were people living in northern climes and had some form of forced inactivity imposed on them. The last remnants of this tradition in North America is the campfire tale that is so often featured in movies, just before the madman starts cutting up teenagers.

So it's been around awhile. The Christmas version is usually told by a grandmother or a trusted nurse, the tale having a homely feel, but a cold shiver as its ultimate goal. It should be no surprise that Elizabeth Gaskell wrote "The Old Nurse's Tale"(1852), one of my favorite Christmas tales. The author of Cranford (1851) was doing what many women Victorian writers did, penning a ghost story for Christmas (and some holiday cash). Many of these stories were published by Mr. Dickens in his Christmas numbers of Household Words and All the Year Round. In this way Dickens did contribute to the popularity of Christmas ghosts over and beyond Tiny Tim and Jacob Marley. Fortunately for us, these tales take after Dickens' "The Signal-Man"(1866) more than A Christmas Carol (1843). For this was Dickens' other fault besides wanting to sell a lot of copies of a magazine (a sin I understand only too well): his ghosts tend to be lessons or morals dressed up in chains. A Christmas Carol rises above the lecturing because it is so entertaining and it has creepy ghosts. Other Dickens' Christmas stories such as "The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain" (1848), "Baron Koeldwethout's Apparation" (1838), "A Child's Dream of a Star" (1850), and "The Last Words of the Old Year" (1851) are all heavy on message and light on supernatural thrills.

So it's been around awhile. The Christmas version is usually told by a grandmother or a trusted nurse, the tale having a homely feel, but a cold shiver as its ultimate goal. It should be no surprise that Elizabeth Gaskell wrote "The Old Nurse's Tale"(1852), one of my favorite Christmas tales. The author of Cranford (1851) was doing what many women Victorian writers did, penning a ghost story for Christmas (and some holiday cash). Many of these stories were published by Mr. Dickens in his Christmas numbers of Household Words and All the Year Round. In this way Dickens did contribute to the popularity of Christmas ghosts over and beyond Tiny Tim and Jacob Marley. Fortunately for us, these tales take after Dickens' "The Signal-Man"(1866) more than A Christmas Carol (1843). For this was Dickens' other fault besides wanting to sell a lot of copies of a magazine (a sin I understand only too well): his ghosts tend to be lessons or morals dressed up in chains. A Christmas Carol rises above the lecturing because it is so entertaining and it has creepy ghosts. Other Dickens' Christmas stories such as "The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain" (1848), "Baron Koeldwethout's Apparation" (1838), "A Child's Dream of a Star" (1850), and "The Last Words of the Old Year" (1851) are all heavy on message and light on supernatural thrills.Dickens was the promoter of Christmas and ghosts, but fortunately the man they all turned to for inspiration was J Sheridan Le Fanu. Le Fanu's many ghost stories set the holiday scribes on the right path. "Madam Crowl's Ghost," "The Child Who Went With the Fairies," "The White Cat of Drumgunniol," "Sir Dominick's Bargain," "The Vision of Tom Chuff," and "Stories of Lough Guir" all appeared in Dickens' All the Year Round, usually around December. Others appeared in Le Fanu's Dublin University Magazine. Le Fanu, despite seeing himself as a serious historical novelist, is largely remembered for these and other ghost and mystery stories. The Irish writer drew upon the tales of his country for inspiration, and why not? The winter tale is related to "Marchen" or fairy tales, both being part of the oral tradition of storytelling.

The greatest ghost story writer of them all (my opinion, but many would agree) was Le Fanu's disciple, MR James. The Cambridge and Eton don wrote an annual Christmas story and shared it with students and friends. These yearly treats were much looked forward to and there was even a little prestige in being including in such a reading. The thirty-three stories that James produced over the decades are sterling examples of what a ghost story can and should do. Classics like "Casting the Runes," "Count Magnus," "The Ash Tree," "Canon Alberic's Scrapbook," and "Lost Hearts" all begin quietly, usually about an amateur antiquarian on a holiday, but end with a glimpse into the cold netherworlds that lurk near by. James' ghosts are never fun, kind, or even well-defined. They are truly terrible, half-glimpsed, and cruel. How Christmasy!

The greatest ghost story writer of them all (my opinion, but many would agree) was Le Fanu's disciple, MR James. The Cambridge and Eton don wrote an annual Christmas story and shared it with students and friends. These yearly treats were much looked forward to and there was even a little prestige in being including in such a reading. The thirty-three stories that James produced over the decades are sterling examples of what a ghost story can and should do. Classics like "Casting the Runes," "Count Magnus," "The Ash Tree," "Canon Alberic's Scrapbook," and "Lost Hearts" all begin quietly, usually about an amateur antiquarian on a holiday, but end with a glimpse into the cold netherworlds that lurk near by. James' ghosts are never fun, kind, or even well-defined. They are truly terrible, half-glimpsed, and cruel. How Christmasy!"Christmasy?" you ask. Yes, of course. The shiver that goes down your spine after a truly effective ghost story is not so much different than the feeling of outré joy that the story of Jesus's birth inspires in Christians. In a way, the whole purpose of the Christmas ghost story is to jump-start your sense of the impossible, a faculty that becomes atrophied after months of going to work, enduring the hum-drum tedium that is life. Here is a small dose of Something Greater. Dickens tried in several stories to create this jump-start from a happy place. He fails. James and his wicked spirits never do.

I understand that the idea of a scary story at Christmas is hard to understand today. I live in Canada, perhaps the most realistic country in the world. We get White Christmases, but not ghostly ones. Robertson Davies, the Canadian author, defined it as "the rational rickets." We are so depleted of fantastic imagination, we think men chasing a small black dot around on ice is fun. (Beer helps.) Despite this, Davies wrote his own book of Canadian Christmas ghosts called High Spirits (1982). It is surprising that the deft wordsmith does not reach for the black depths of MR James (who inspired Davies to tell an annual tale for the enjoyment of his college buddies), but Davies' ghosts are enchanting and humorous. As the title implies, jocularity is the key. Ghosts like "The Ghost Who Vanished By Degrees," the grad student who never received his Masters and PhD and the only way Davies can lay him to rest is to give him more and more degrees. The titles are suggestive: "The Ugly Spectre of Sexism," "The Refuge of Insulted Saints," "The Xerox in the Lost Room," and "Dickens Digested." Davies' ghosts take after the stories of J Kendrick Bangs' "Told After Supper" (1891). If you can't quite manage horrific ghosts this Yuletide, I would suggest Davies or Bangs.

I understand that the idea of a scary story at Christmas is hard to understand today. I live in Canada, perhaps the most realistic country in the world. We get White Christmases, but not ghostly ones. Robertson Davies, the Canadian author, defined it as "the rational rickets." We are so depleted of fantastic imagination, we think men chasing a small black dot around on ice is fun. (Beer helps.) Despite this, Davies wrote his own book of Canadian Christmas ghosts called High Spirits (1982). It is surprising that the deft wordsmith does not reach for the black depths of MR James (who inspired Davies to tell an annual tale for the enjoyment of his college buddies), but Davies' ghosts are enchanting and humorous. As the title implies, jocularity is the key. Ghosts like "The Ghost Who Vanished By Degrees," the grad student who never received his Masters and PhD and the only way Davies can lay him to rest is to give him more and more degrees. The titles are suggestive: "The Ugly Spectre of Sexism," "The Refuge of Insulted Saints," "The Xerox in the Lost Room," and "Dickens Digested." Davies' ghosts take after the stories of J Kendrick Bangs' "Told After Supper" (1891). If you can't quite manage horrific ghosts this Yuletide, I would suggest Davies or Bangs.Me? I'll stick to the harder stuff. Perhaps a little Algernon Blackwood, who used to read his stories at Christmas on the BBC. Feeling Victorian? Then there is no better place to go than the Gaslight website. Like a mix of Radio and print? Then the Amalgamated Brotherhood of Spooks will do.

One last suggestion: if you'd like a taste of MR James, try Mark Gatiss's BBC TV version of "The Tractate Middoth" and his documentary about James. And if you catch the mood, there is a collection of MR James BBC shows.

Happy holidays and enjoy the ghosts!

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on December 24, 2015 04:00

December 23, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | George C Scott (1984)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Director Clive Donner's version cuts abruptly from the merriment in front of the Exchange where the band is playing and kids are sliding on ice. As Cratchit and Tiny Tim head home from that happy scene, Scrooge has a downright spooky walk towards his house.

The sun has gone down and the fog is rolling in, but that's not the worst of it. Donner goes full out chilling - foreshadowing what's going to happen at Scrooge's door - by having a hearse roll by and a disembodied voice call Scrooge's name before the hearse disappears into the fog. The disappearance is a nice effect, by the way. It looks like the hearse vanishes supernaturally and if you watch the scene closely, that's clearly what it's doing. But it's replaced by so much fog that if you were in Scrooge's shoes, you wouldn't be sure that it hadn't just been obscured by the natural mist.

None of this is in Dickens, so we have to speculate about what's going on there. The voice calling Scrooge's name sounds like Marley, so Marley must be starting to cross through the veil between his world and ours. He's working up to it. First we get a voice, then we'll get his face on the knocker, and then we'll get the whole ghost. But why the hearse? It could be a vision of Scrooge's future or simply a generic reminder of mortality. I'd love to hear other theories in the comments.

Because of the long, scary walk to Scrooge's house, it does feel withdrawn. In fact, Scrooge's gate is off a grungy-looking alley that's lined with ladders and barrels and a cart. There's no indication that he shares his building with office space, but he's certainly living next door to some. And skipping ahead to Christmas morning, there won't be any traffic to speak of in that alley either. This version does a great job communicating a house that's hiding from the rest of London.

Published on December 23, 2015 04:00

December 22, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Albert Finney (1970)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Because of how the musical Scrooge reorganizes the scenes, Scrooge's journey home includes the charitable solicitors for a short bit. This is an annoying interpretation of those characters and their clueless dogging of Scrooge through the streets launches him into a song about how much he hates people.

Scavengers and sycophants and flatterers and fools.

Pharisees and parasites and hypocrites and ghouls.

Calculating swindlers, prevaricating frauds,

Perpetrating evil as they roam the earth in hordes

Feeding on their fellow men; reaping rich rewards,

Contaminating everything they see.

Corrupting honest men... like me.

I hate people! I hate people!

People are despicable creatures.

Loathsome, inexplicable creatures.

Good-for-nothing, kickable creatures.

I hate people! I abhor them!

When I see the indolent classes

Sitting on their indolent asses;

Gulping ale from indolent glasses,

I hate people!

I detest them! I deplore them!

Fools who have no money spend it;

Get in debt then try to end it;

Beg me on their knees befriend them

Knowing I have cash to lend them.

Soft-hearted me! Hard-working me!

Clean-living, thrifty, and kind as can be!

Situations like this are of interest to me.

I hate people! I loathe people!

I despise and abominate people!

Life is full of cretinous wretches

Earning what their sweatiness fetches,

Empty minds whose pettiness stretches

Further than I can see.

Little wonder... I hate people

And I don't care if they hate me!

There are cuts in the video above where Scrooge interrupts the song to collect money from various vendors. If they can't pay - and none of them can - he offers to sell them a week's extension or else they forfeit their businesses and assets to him. Instead of hitting a tavern for his meal, he also extorts a meager supper from the vendors.

This activity draws the attention of the caroling kids whom Scrooge drove away from his office earlier in the movie, so his song segues into their sarcastically titled "Father Christmas."

Father Christmas!

Father Christmas!

He's the meanest man

In the whole wide world,

In the whole wide world

You can feel it.

He's a miser.

He's a skinflint.

He's a stingy lout.

Leave your stocking out

For your Christmas gift

And he'll steal it

It's a shame.

He's a villain.

What a game

For a villain to play

On Christmas Day.

After Christmas,

Father Christmas

Will be just as mean as he's ever been

And I'm here to say,

We should all send Father Christmas

On his merry Christmas way.

Father Christmas!

Father Christmas!

He’s the rottenest man

In the universe

And there’s no one worse.

You can tell it.

He’s a rascal.

He’s a bandit.

He’s a crafty one.

Leave your door undone;

He’ll move in your house

And sell it

It’s a crime.

It’s a scandal.

What a game

For a vandal to play

On Christmas day.

If you distrust

Father Christmas,

It’s as well to know

That I told you so,

‘Cause I’m here to say,

We should all send Father Christmas

Father Christmas, Father Christmas

Father Christmas, Father Christmas

On his merry Christmas way.

Their song done, the boys let Scrooge go and he ends up on a lonely street that the set designers have done a lovely job of making look hidden away from the rest of the city.

Published on December 22, 2015 04:00

December 21, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Fredric March (1954)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Shower of Stars' adaptation cuts this scene down to almost nothing. After spending a little time with Scrooge's closing up the office, it follows him into the streets, nervously clutching his cashbox. He hasn't even turned the corner before the scene dissolves to the interior of his house. Not only is there no dinner scene, but there's also no exterior shot of his home or - as we'll talk more about next year - even a door-knocker.

Published on December 21, 2015 04:00

December 19, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Alastair Sim (1951)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

The 1951 Scrooge is famous for adding to Dickens' story, but it stays pretty trim in this scene. Cutting away from Cratchit's positively bouncing as he wraps up to leave the office, the movie follows Scrooge into the street. People bustle all around him. They're not really all that merry (no one's wishing anyone "Merry Christmas," for instance); they're just busy. Scrooge moves silently and determinedly through them and there's a funny bit where a blind guy (conveniently labeled with a sign around his neck) is pulled out of Scrooge's way by his dog.

Scrooge's tavern doesn't feel especially melancholy. There are people in the street outside, so it's not in an isolated part of town. And more important, there are people in the restaurant, eating and talking and smiling. The conversations are all quiet, so it's not a raucous place, but it's clear that Scrooge - sitting by himself with a partition between him and the others - is the melancholy element.

The interactions between Scrooge and the server have been silent in the last couple of versions, but it's different this time. In Matthau, Hicks, and Owen's adaptations, the focus is on how stingy Scrooge is. Matthau tips his server with a dirty spoon, Hicks scowls at his as if he expects to be cheated on the change, and Owen actually bites into a coin from his change to make sure it's good. There's none of that with Sim.

Instead, his Scrooge asks the server for more bread and is told that there isn't any extra. Scrooge pouts disappointedly and then barks, "No more bread!" as if it's his decision. That's a perfect fit with the way Sim has been playing the character. His Scrooge isn't mean and miserly for the sake of being mean and miserly. He's simply got a very small worldview and is irritated, but also continually disappointed whenever it's challenged. He feels entitled to some things. And some of them, like people paying their loans back on time, aren't so unreasonable. But he also feels entitled not to be imposed on for charity and not to be robbed of a day's work by his clerk. These are understandable viewpoints, but they're very selfish and petty. And he reacts to the inconvenience the same way he reacts to getting no extra bread, like it's a personal attack. Every aggravation is further proof that the world hates him and that he's right for despising it. Every day is a bad day for Ebenezer Scrooge.

After dinner, Scrooge heads home. There's no gate or yard in this version; sort of like Scrooge McDuck's house in Mickey's Christmas Carol, his front door is right on the sidewalk. I don't remember that we ever get a look at Scrooge's street during the daytime in this version, but it's a wide street and I imagine that it gets a fair amount of traffic. His house isn't really tucked out of the way at all, but it does feel lonely this time of night with snow everywhere and no one else around.

Published on December 19, 2015 04:00

December 18, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Reginald Owen (1938)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Like I mentioned last year, the 1938 Christmas Carol follows Bob Cratchit outside, but it's not to watch him slide with the boys. Instead, he gets caught up in a snowball fight and soon begins teaching the lads his technique for a perfect snowball. The kids' lookout lets them know that there's a fellow coming with a top hat, so Cratchit sees an opportunity to continue the boys' education in proper throwing. Unfortunately, he lets fly and knocks the man's hat off before realizing that it's Scrooge himself. Apparently the boss didn't stick around too long at the office.

Scrooge looks positively shocked that Cratchit would behave this way. I've always read that as simple indignation, but after measuring up Scrooge last year, I now either detect or imagine some actual hurt in his expression. My working theory is that Owen's Scrooge sort of sees some promise in Cratchit, but is constantly disappointed by the man's choices. This insult is one step too far and - in a shocking move for those familiar with the story - Scrooge fires Cratchit right there. I used to think he's just being mean, but now I believe Scrooge is acting out of distress. He feels betrayed and responds in his typically nasty way.

The movie continues to follow Cratchit, who's despondent at first, but quickly recovers his Christmas cheer. He's just been paid (minus what Scrooge charged him for the ruined top hat) and it's fun to watch him go on a Christmas shopping spree, collecting the food for tomorrow's feast. Over and over again he announces to a vendor that he's willing to spend x amount, but then increases it in keeping with the celebration. I don't know if he blows his whole payday, but he doesn't seem to care if he does. He's determined that whatever happens on December 26th, this is going to be an awesome Christmas.

This version follows Cratchit all the way home and we get to meet his family earlier than in most adaptations. (Of course, we've already met Peter and Tiny Tim in the first scene.) He doesn't tell anyone that he was sacked; he's intent on their enjoying the holiday without letting Scrooge ruin it.

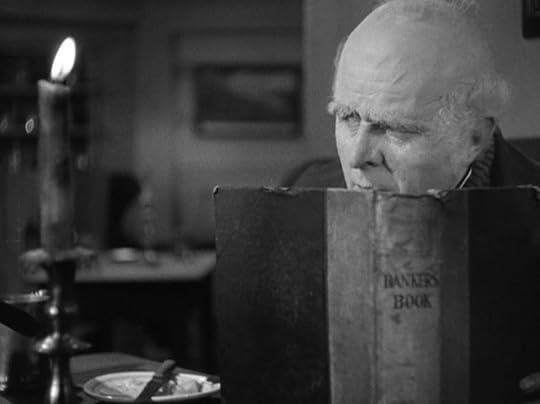

The film then dissolves into Scrooge's lonely dinner at the tavern where he's reading a banker's book. Like in the Seymour Hicks version, this one communicates melancholy by having Scrooge be the only patron in the place. Curiously, he leaves the banker's book on the table when he leaves, as if it belongs to the tavern. Maybe I misunderstood what a banker's book is (my annotated Christmas Carol and Google don't elaborate) or maybe it's a mistake of the movie, but it's interesting to think of it as possibly not Scrooge's own accounting records, but some sort of publication circulated by the finance industry. Perhaps Scrooge doesn't own a copy himself, but comes to this tavern to read theirs. It's a weird theory and doesn't seem likely, but it's the best I have.

After dinner, Scrooge makes his way home. The streets aren't as empty as in some of the other versions we've looked at so far, but they're lonelier near Scrooge's house. This version has the big gate, but a small yard. Still, the large, old house looks plenty withdrawn and desolate.

Published on December 18, 2015 04:00

December 17, 2015

His Usual Melancholy Tavern | Seymour Hicks (1935)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Director Henry Edwards' Scrooge does a lot with our scene this year and it's one of the reasons I wanted to keep it separate instead of rolling into another one. The movie picks up a lot of things that Dickens had earlier in the story and presents them in the time between Scrooge's leaving the office and arriving home. There's Cratchit's joining the neighborhood boys for a slide on the ice, but we also check in on other Christmas celebrants. Fred comes home with loads of packages while Cratchit makes it safely to his place with the holiday bird and sprig of greenery. The music is cheery and all the dreariness of the earlier outdoor scene is gone. Christmas is finally in full force.

There's an especially lovely bit at the Lord Mayor's house, making this one of the few versions to adapt that part of Dickens' text. It's not exactly as written, but we get to see all the preparations for a luxurious feast as guests arrive and the wine-tasters, bakers, and various chefs go about their business. In a beautiful representation of Dickens' primary theme, we also see a crowd of street people looking hungrily in through the window at the bustling kitchen. And it's gratifying when one of the chefs brings over a plate of unusable food to distribute to them. Later, when the Lord Mayor leads his guests in a toast and a chorus of "God Save the Queen," those outside the mansion sing just as faithfully and loudly. Politics aside, it's a touching example of camaraderie and national pride.

All this joy is contrasted with Scrooge as he "Humbugs" his way past well-wishers and enters his tavern. It is quite melancholy, since he's the only patron. The landlord is actually sleeping at a table until Scrooge enters and wakes him up with a rap of his cane on another piece of furniture. After a solitary meal, Scrooge makes his lonely walk home and we get this version's account of the blind man's dog that doesn't like the old miser.

It's tough to figure at what point Scrooge arrives at his house. The scene has him walking through a couple of sets to get there and when he goes through a large gate just before a cut to his front door, I can't tell if that's the gate to his house or just another part of London. If it's his house though, it's impressive. Either way, by having Scrooge go through so many empty sets, the movie does a nice job of expressing how isolated and out of the way his place is.

It also finds a clever way to reveal that Scrooge isn't the original owner of the place. On the front door is a sign with Marley and Scrooge's names on it and - just like the one at the office - Marley's is scratched out. I guess that implies that Marley and Scrooge were housemates, rather than Scrooge's inheriting it from his partner, but it's cool that the sign is right under the infamous knocker that's about to call Marley's existential status into question.

Published on December 17, 2015 04:00

December 16, 2015

Ian Fleming’s Seven Deadlier Sins: Self-Righteousness

No Dickens today, because we would have been covering Thomas Edison's silent version and he skips right over this year's scene even more than most adaptations.

Instead, I'd like to point you towards the Literary 007 blog where they're doing a series on Ian Fleming's idea of the Seven Deadlier Sins. These are evils that Fleming felt were more worthy of punishment than the traditional list. The proprietor of the site asked if I'd like to write an entry and I eagerly snatched up Self-Righteousness. I hope you'll go read as I speculate on Fleming's relationship with the sin, point out examples of it from the novels, and explain why I agree with Fleming that it's an especially odious offense.

Published on December 16, 2015 04:00