Michael May's Blog, page 115

May 13, 2016

Hellbent for Letterbox: God is not responsible for the podcast you choose

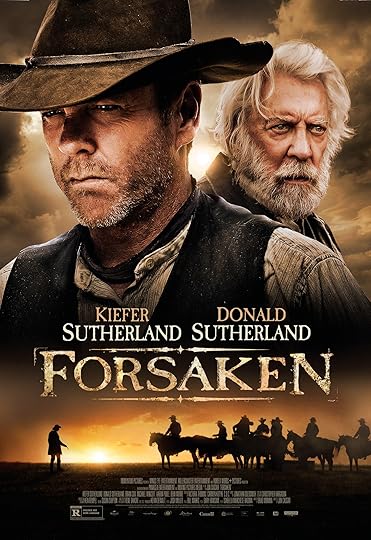

On the latest Hellbent for Letterbox, Pax and I discuss Forsaken starring Kiefer and Donald Sutherland, Demi Moore, Brian Cox, and Michael Wincott. We're pretty free with the spoilers, so I recommend watching the movie before listening to the show, but we both loved it and recommend watching it anyway.

We also briefly touched on the concept of contemporary Westerns (movies like Brokeback Mountain and No Country for Old Men) and whether or not those scratch the Western itch for us.

Published on May 13, 2016 18:00

May 12, 2016

British History in Film | King John (1984)

Shakespeare's King John isn't one of his most popular plays, but I've always been interested in seeing it as a sort of sequel to the Robin Hood legend. There aren't too many versions available for home viewing, but the 1984 BBC production directed by David Giles and starring Leonard Rossiter is a fine production.

I'm no Shakespeare scholar - or even a super knowledgeable fan - but I wonder about why King John isn't more widely regarded. It has some great speeches and iconic scenes and Giles' version is especially well-performed. Rossiter is fantastic as the selfish, sometimes cowardly John, but George Costigand steals the show as the king's intelligent and humorous bastard nephew, son of the late King Richard. There's also some great casting for a couple of English noblemen, starting with Robert Brown, who was M in the '80s Bond movies.

John Castle is another cool actor who plays a noble. I wouldn't have known him before this project, but he was King John's brother Geoffrey in The Lion in Winter. Geoffrey's dead by the time King John takes place, but his presence is still very much felt. In Lion in Winter, Geoffrey's claim to the throne wasn't supported by either of his parents, but he did have the new king of France (played then by young Timothy Dalton) as an ally. In King John, King Philip is much older, but still supports Geoffrey's family. In fact, the play's drama is kicked off by Philip's insistence that Geoffrey's son is the rightful ruler of England.

There are some speeches that go long in the middle, but I'll sit through those for lopped-off heads and people falling off of castle walls. Sadly, I couldn't find a movie about John's son, Henry III, so next time we'll skip ahead to grandson Edward.

Published on May 12, 2016 18:00

May 11, 2016

Wait Here While I Describe the Eldritch Horror: Weird Tales Radio? [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

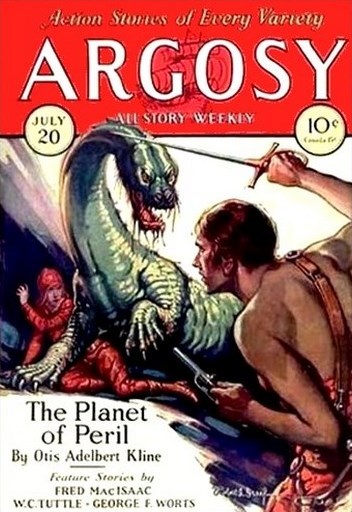

You learn the strangest things when you read "The Eyrie," the old letter column in Weird Tales. Like that a boyish Julius Schwartz was a big Robert E Howard fan back in 1933. Or that the readership was split 50-50 over the interplanetary fiction of Otis Adelbert Kline. Or that Weird Tales tried to spawn its own radio show. "A radio show?" you ask.

You learn the strangest things when you read "The Eyrie," the old letter column in Weird Tales. Like that a boyish Julius Schwartz was a big Robert E Howard fan back in 1933. Or that the readership was split 50-50 over the interplanetary fiction of Otis Adelbert Kline. Or that Weird Tales tried to spawn its own radio show. "A radio show?" you ask.

This should be no surprise as many of the pulps either had radio counterparts or even started as radio shows. The classic example of this is The Shadow, which began with Orson Welles as the mysterious voice and narrator. This, in turn, spawned the pulp adventures of Lamont Cranston that went on to become Street & Smith's best selling magazine. Usually, it worked the other way around. Pulp characters such as Tarzan, the Saint, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and Zorro began as magazine characters, then got radio and eventually film counterparts.

One of the popular formats was the anthology show, with programs such as Suspense, Escape, Lights Out! and X-Minus One. Whether mysteries, horror or science fiction, the audience expected a new tale each week in a manner we have come to think of as The Twilight Zone format. Though Rod Serling certainly borrowed the idea from radio. The anthology shows often took their material from magazines, allowing the publications to plug their content. X-Minus One partnered with Galaxy and Astounding. Suspense tried it the other way, spawning a short-lived magazine edited by Leslie Charteris in 1946. Why should Weird Tales be any different?

The recordings are very rare and there isn't much solid information. Was it a show or just a proposed show that never caught on? The promotional flyer says that the producers planned to do 52 episodes. The company that did the recordings was Hollywood Radio Attractions (4376 Sunset Drive, Hollywood, CA.) Actors included William Farnum, Jason Robards Sr, Richard Carle, Viola Dana, Richard Tucker, and Priscilla Dean. All the episodes were adapted by Oliver Drake and produced by Irving Fogel .

The recordings are very rare and there isn't much solid information. Was it a show or just a proposed show that never caught on? The promotional flyer says that the producers planned to do 52 episodes. The company that did the recordings was Hollywood Radio Attractions (4376 Sunset Drive, Hollywood, CA.) Actors included William Farnum, Jason Robards Sr, Richard Carle, Viola Dana, Richard Tucker, and Priscilla Dean. All the episodes were adapted by Oliver Drake and produced by Irving Fogel .

There were three initial episodes done on a demo record. These were recorded in two lengths, as half-hour programs or they could be played in two 15-minute shows. Some radio stations were not part of the larger networks and could determine their own content. Shows like the Weird Tales programs or the earliest adventures of Tarzan could be played as station managers saw fit. There is some evidence that the Weird Tales shows played at midnight on certain local stations.

The three episodes that were recorded for sure were:

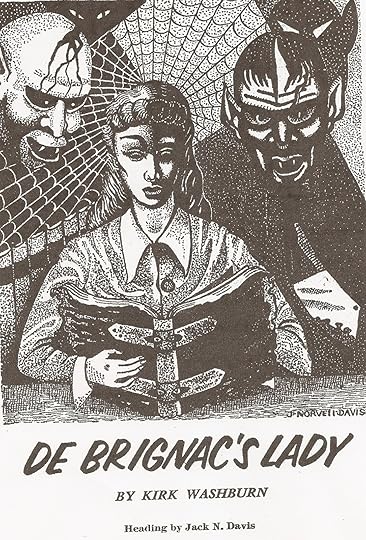

1. "The Living Dead" by Kirk Mashburn (based on "De Brignac's Lady," February 1933). I haven't been able to locate this piece, but in The Monster With a Thousand Faces: Guises of the Vampire in Myth and Literature (1989), author Brian J Frost writes of this story: "Of the latter was captained: 'A story of baby vampires: infant marauders belonging to the Undead!' It's just as ludicrous as it sounds..." Weird Tales featured many vampire and werewolf stories, so this is a natural subject matter. Why they picked Mashburn when they could have gone with Greye LaSpina, H Warner Munn, or Seabury Quinn, I have no idea? I do know that Carl Jacobi's much better vampire tale, "Revelations in Black" was one of the proposed 52 stories.

2. "The Curse of Nagana" by Hugh B Cave (original title "The Ghoul Gallery." June 1932) is the story of Doctor Briggs who goes to the haunted mansion of Lord Ramsey, along with his beautiful fiancée, Lady Ravenal. In the best gothic tradition, the lords of Ramsey have been killed in the upper galleries of the house by a strangling phantom. The villain proves to be a vengeful ghost in the form of a painting. Cave's style is typical of his Shudder Pulp stories with the setting and psychic doctor character harkening back to the English ghost writers. (Not everyone agrees with me on that. In "The Eyrie," reader Harold Dunbar of Chatham, Massachusetts wrote: "...This author has a fine rolling style and a depth which few writers of weird fiction can rival...")

2. "The Curse of Nagana" by Hugh B Cave (original title "The Ghoul Gallery." June 1932) is the story of Doctor Briggs who goes to the haunted mansion of Lord Ramsey, along with his beautiful fiancée, Lady Ravenal. In the best gothic tradition, the lords of Ramsey have been killed in the upper galleries of the house by a strangling phantom. The villain proves to be a vengeful ghost in the form of a painting. Cave's style is typical of his Shudder Pulp stories with the setting and psychic doctor character harkening back to the English ghost writers. (Not everyone agrees with me on that. In "The Eyrie," reader Harold Dunbar of Chatham, Massachusetts wrote: "...This author has a fine rolling style and a depth which few writers of weird fiction can rival...")

Fortunately, thanks to Rand's Esoteric OTR , we can listen to a portion of this show and see how the original material was treated. The story's original cast of four is expanded to include a maid (cannon fodder), but more importantly the character of Nagana, a stranger from the Orient who turns out to be the villain of the piece instead of a real ghost. The final scene in the gallery is the same but instead of finding the coffin of Sir Ravenel, the doorway behind the painting leads to the roof where Nagana plans to sacrifice Sir Guy, having hypnotized him. All this is narrated by Parker, the butler who acts as the doctor's side-kick. What Hugh B Cave thought of this I'm not sure, replacing his admittedly well-worn ideas for different well-worn ideas.

3. "Three From the Tomb" by Edmond Hamilton (February 1932) is a typical what-if story from that author. Hamilton wrote many interesting SF tales by asking that question. What if humans all reverted to cavemen ("World Atavism" in Amazing Stories, August 1930)? What if a man evolved centuries into the future ("The Man Who Evolved" in Wonder Stories, April 1931)? What if everyone fell asleep at the same time ("When the World Slept" in Weird Tales, July 1936)? And on and on...

I suppose the company presenting the first shows would not want to confuse potential consumers with too wide a genre selection, so they selected one of Hamilton's stories with a more morbid angle. In the original story, we follow reporter Jerry Farley and county detective Peter Todd as they unravel the mystery of how Dr. Charles Curtlin resurrects three rich men who had been dead for six months. Todd interviews each man, asking him if he remembers being threatened by unknown parties before their deaths. Each answered that he did. The final solution to the mystery is presented at the moment Dr. Curtlin reveals his final specimen, before he will supposedly destroy the resurrection ray machine and his notes. Todd knows the whole thing is a con and proves it by admitting that none of the dead had ever been threatened at all. Curtlin is a famed plastic surgeon and created false millionaires so he could control their money. This kind of fake science fiction tale would prove more popular in magazines like The Saint with stories by Cleve Cartmill, or in the tales of Ed Hoch in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, though the tradition runs back to Ann Radcliffe and her explained away horrors.

I suppose the company presenting the first shows would not want to confuse potential consumers with too wide a genre selection, so they selected one of Hamilton's stories with a more morbid angle. In the original story, we follow reporter Jerry Farley and county detective Peter Todd as they unravel the mystery of how Dr. Charles Curtlin resurrects three rich men who had been dead for six months. Todd interviews each man, asking him if he remembers being threatened by unknown parties before their deaths. Each answered that he did. The final solution to the mystery is presented at the moment Dr. Curtlin reveals his final specimen, before he will supposedly destroy the resurrection ray machine and his notes. Todd knows the whole thing is a con and proves it by admitting that none of the dead had ever been threatened at all. Curtlin is a famed plastic surgeon and created false millionaires so he could control their money. This kind of fake science fiction tale would prove more popular in magazines like The Saint with stories by Cleve Cartmill, or in the tales of Ed Hoch in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, though the tradition runs back to Ann Radcliffe and her explained away horrors.

A business letter dated February 14, 1933 - included in Lost in the Rentharpian Hills: Spanning the Decades with Carl Jacobi (1985) - written by Farnsworth Wright to Carl Jacobi states that any money the radio broadcasts might make would be given to the authors as Weird Tales was not using the show to make money, but to increase sales of the magazine. The fact that the personal correspondence between WT authors don't include lengthy discussions of radio income suggests that the radio show never took off. This is too bad for several reasons. First off, writers like HP Lovecraft could have used that dough. But more for us today, I would love to have heard a radio dramatization of Jules de Grandin, filled with exclamations of “Sacré nom d’un fromage vert!” Now there's an acting job only an old-time radio star could pull off.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

You learn the strangest things when you read "The Eyrie," the old letter column in Weird Tales. Like that a boyish Julius Schwartz was a big Robert E Howard fan back in 1933. Or that the readership was split 50-50 over the interplanetary fiction of Otis Adelbert Kline. Or that Weird Tales tried to spawn its own radio show. "A radio show?" you ask.

You learn the strangest things when you read "The Eyrie," the old letter column in Weird Tales. Like that a boyish Julius Schwartz was a big Robert E Howard fan back in 1933. Or that the readership was split 50-50 over the interplanetary fiction of Otis Adelbert Kline. Or that Weird Tales tried to spawn its own radio show. "A radio show?" you ask.This should be no surprise as many of the pulps either had radio counterparts or even started as radio shows. The classic example of this is The Shadow, which began with Orson Welles as the mysterious voice and narrator. This, in turn, spawned the pulp adventures of Lamont Cranston that went on to become Street & Smith's best selling magazine. Usually, it worked the other way around. Pulp characters such as Tarzan, the Saint, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and Zorro began as magazine characters, then got radio and eventually film counterparts.

One of the popular formats was the anthology show, with programs such as Suspense, Escape, Lights Out! and X-Minus One. Whether mysteries, horror or science fiction, the audience expected a new tale each week in a manner we have come to think of as The Twilight Zone format. Though Rod Serling certainly borrowed the idea from radio. The anthology shows often took their material from magazines, allowing the publications to plug their content. X-Minus One partnered with Galaxy and Astounding. Suspense tried it the other way, spawning a short-lived magazine edited by Leslie Charteris in 1946. Why should Weird Tales be any different?

The recordings are very rare and there isn't much solid information. Was it a show or just a proposed show that never caught on? The promotional flyer says that the producers planned to do 52 episodes. The company that did the recordings was Hollywood Radio Attractions (4376 Sunset Drive, Hollywood, CA.) Actors included William Farnum, Jason Robards Sr, Richard Carle, Viola Dana, Richard Tucker, and Priscilla Dean. All the episodes were adapted by Oliver Drake and produced by Irving Fogel .

The recordings are very rare and there isn't much solid information. Was it a show or just a proposed show that never caught on? The promotional flyer says that the producers planned to do 52 episodes. The company that did the recordings was Hollywood Radio Attractions (4376 Sunset Drive, Hollywood, CA.) Actors included William Farnum, Jason Robards Sr, Richard Carle, Viola Dana, Richard Tucker, and Priscilla Dean. All the episodes were adapted by Oliver Drake and produced by Irving Fogel .There were three initial episodes done on a demo record. These were recorded in two lengths, as half-hour programs or they could be played in two 15-minute shows. Some radio stations were not part of the larger networks and could determine their own content. Shows like the Weird Tales programs or the earliest adventures of Tarzan could be played as station managers saw fit. There is some evidence that the Weird Tales shows played at midnight on certain local stations.

The three episodes that were recorded for sure were:

1. "The Living Dead" by Kirk Mashburn (based on "De Brignac's Lady," February 1933). I haven't been able to locate this piece, but in The Monster With a Thousand Faces: Guises of the Vampire in Myth and Literature (1989), author Brian J Frost writes of this story: "Of the latter was captained: 'A story of baby vampires: infant marauders belonging to the Undead!' It's just as ludicrous as it sounds..." Weird Tales featured many vampire and werewolf stories, so this is a natural subject matter. Why they picked Mashburn when they could have gone with Greye LaSpina, H Warner Munn, or Seabury Quinn, I have no idea? I do know that Carl Jacobi's much better vampire tale, "Revelations in Black" was one of the proposed 52 stories.

2. "The Curse of Nagana" by Hugh B Cave (original title "The Ghoul Gallery." June 1932) is the story of Doctor Briggs who goes to the haunted mansion of Lord Ramsey, along with his beautiful fiancée, Lady Ravenal. In the best gothic tradition, the lords of Ramsey have been killed in the upper galleries of the house by a strangling phantom. The villain proves to be a vengeful ghost in the form of a painting. Cave's style is typical of his Shudder Pulp stories with the setting and psychic doctor character harkening back to the English ghost writers. (Not everyone agrees with me on that. In "The Eyrie," reader Harold Dunbar of Chatham, Massachusetts wrote: "...This author has a fine rolling style and a depth which few writers of weird fiction can rival...")

2. "The Curse of Nagana" by Hugh B Cave (original title "The Ghoul Gallery." June 1932) is the story of Doctor Briggs who goes to the haunted mansion of Lord Ramsey, along with his beautiful fiancée, Lady Ravenal. In the best gothic tradition, the lords of Ramsey have been killed in the upper galleries of the house by a strangling phantom. The villain proves to be a vengeful ghost in the form of a painting. Cave's style is typical of his Shudder Pulp stories with the setting and psychic doctor character harkening back to the English ghost writers. (Not everyone agrees with me on that. In "The Eyrie," reader Harold Dunbar of Chatham, Massachusetts wrote: "...This author has a fine rolling style and a depth which few writers of weird fiction can rival...")Fortunately, thanks to Rand's Esoteric OTR , we can listen to a portion of this show and see how the original material was treated. The story's original cast of four is expanded to include a maid (cannon fodder), but more importantly the character of Nagana, a stranger from the Orient who turns out to be the villain of the piece instead of a real ghost. The final scene in the gallery is the same but instead of finding the coffin of Sir Ravenel, the doorway behind the painting leads to the roof where Nagana plans to sacrifice Sir Guy, having hypnotized him. All this is narrated by Parker, the butler who acts as the doctor's side-kick. What Hugh B Cave thought of this I'm not sure, replacing his admittedly well-worn ideas for different well-worn ideas.

3. "Three From the Tomb" by Edmond Hamilton (February 1932) is a typical what-if story from that author. Hamilton wrote many interesting SF tales by asking that question. What if humans all reverted to cavemen ("World Atavism" in Amazing Stories, August 1930)? What if a man evolved centuries into the future ("The Man Who Evolved" in Wonder Stories, April 1931)? What if everyone fell asleep at the same time ("When the World Slept" in Weird Tales, July 1936)? And on and on...

I suppose the company presenting the first shows would not want to confuse potential consumers with too wide a genre selection, so they selected one of Hamilton's stories with a more morbid angle. In the original story, we follow reporter Jerry Farley and county detective Peter Todd as they unravel the mystery of how Dr. Charles Curtlin resurrects three rich men who had been dead for six months. Todd interviews each man, asking him if he remembers being threatened by unknown parties before their deaths. Each answered that he did. The final solution to the mystery is presented at the moment Dr. Curtlin reveals his final specimen, before he will supposedly destroy the resurrection ray machine and his notes. Todd knows the whole thing is a con and proves it by admitting that none of the dead had ever been threatened at all. Curtlin is a famed plastic surgeon and created false millionaires so he could control their money. This kind of fake science fiction tale would prove more popular in magazines like The Saint with stories by Cleve Cartmill, or in the tales of Ed Hoch in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, though the tradition runs back to Ann Radcliffe and her explained away horrors.

I suppose the company presenting the first shows would not want to confuse potential consumers with too wide a genre selection, so they selected one of Hamilton's stories with a more morbid angle. In the original story, we follow reporter Jerry Farley and county detective Peter Todd as they unravel the mystery of how Dr. Charles Curtlin resurrects three rich men who had been dead for six months. Todd interviews each man, asking him if he remembers being threatened by unknown parties before their deaths. Each answered that he did. The final solution to the mystery is presented at the moment Dr. Curtlin reveals his final specimen, before he will supposedly destroy the resurrection ray machine and his notes. Todd knows the whole thing is a con and proves it by admitting that none of the dead had ever been threatened at all. Curtlin is a famed plastic surgeon and created false millionaires so he could control their money. This kind of fake science fiction tale would prove more popular in magazines like The Saint with stories by Cleve Cartmill, or in the tales of Ed Hoch in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, though the tradition runs back to Ann Radcliffe and her explained away horrors.A business letter dated February 14, 1933 - included in Lost in the Rentharpian Hills: Spanning the Decades with Carl Jacobi (1985) - written by Farnsworth Wright to Carl Jacobi states that any money the radio broadcasts might make would be given to the authors as Weird Tales was not using the show to make money, but to increase sales of the magazine. The fact that the personal correspondence between WT authors don't include lengthy discussions of radio income suggests that the radio show never took off. This is too bad for several reasons. First off, writers like HP Lovecraft could have used that dough. But more for us today, I would love to have heard a radio dramatization of Jules de Grandin, filled with exclamations of “Sacré nom d’un fromage vert!” Now there's an acting job only an old-time radio star could pull off.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on May 11, 2016 04:00

May 9, 2016

The Year in Movies: 1926

The Black Pirate (1926)

Douglas Fairbanks plays a nobleman who pretends to be a pirate in order to take down the buccaneers responsible for his father's death. There's a love story too of course when they capture a ship with a princess aboard. And naturally our hero comes into conflict with the previous leader of the pirate gang, who also has an interest in the princess.

A lot of the elements are predictable, but there are complications to keep it interesting. And that's in addition to the amazingly athletic swashbuckling that Fairbanks is so excellent at. My print doesn't have a real score, but just some generic orchestral music, so that's my only complaint. One of the first pirate movies is also one of the best.

The Bat (1926)

I'm really fond of the 1959 version starring Vincent Price and Agnes Moorehead, so I wanted to see this one adapting the same play. Now I need to see the Price one again to compare, because I think I may actually like this one even better. The plot's basically the same - a killer called The Bat terrorizes a bunch of people in a mansion that may have a lot of money hidden in it somewhere - but the '26 version surprised me with how gorgeous it is. The sets are huge and extravagant, the shots are dark and stylish, and the Bat's costume is amazing: basically a trench-coated man who wears an elaborate bat mask with huge, fur-covered ears and a working mouth.

My only issue with the film was the soundtrack on the print I watched. I rented it from Amazon where the score is relentlessly dull trance music that kept putting me to sleep. It's atmospheric, but doesn't go well with the movie's many comedic moments. I was captivated by the story and the look of the film, so I persevered, but finally muted the sound and listened to some Sisters of Mercy while I watched. It still didn't fit perfectly, but at least it wasn't boring.

It’s the Old Army Game (1926)

So that's me smitten with Louise Brooks then.

I wanted to check out some Brooks movies and started with this one because it's the earliest that I have access to. I'm also familiar enough with WC Fields to know that I generally like him, so that made it a safe introduction, too.

There's a loose plot about Fields' character getting involved with a land scheme (the movie's title refers to con games), but mostly it's a series of unrelated gags that go on longer than they should. Like when Fields takes his family out for a picnic and has it on the lawn of some rich guy's house. The running joke about the animosity between Fields and his young nephew is especially tiring. The actor playing the nephew was 11, but the character sleeps in a crib and rides in a baby carriage part of the time, so I don't know how old he's supposed to be.

The frustrations are all worth it whenever Brooks shows up though. She's beautiful and charming and absolutely captivating every time she's on screen. Looking forward to seeing some of her other films.

Battling Butler (1926)

A really early version of the tropey romantic comedy formula where a misunderstanding or lie snowballs and threatens to break up our couple if the secret gets out. And rather than having a grown-up conversation about it, the lead character perpetuates the lie, breaking the other person's heart and requiring a big gesture to set things right.

Because it's Buster Keaton, it still works for me, but it relies more on the situation for laughs than on Keaton's physicality. In fact, Keaton's playing a wimp, so his athleticism is intentionally de-emphasized.

The General (1926)

This one's probably the first Buster Keaton movie I ever saw. It's a great introduction because it's essentially a feature-length chase scene. (I've heard it compared to Mad Max: Fury Road, which is kind of appropriate.) There's some introductory stuff to set the stakes, but even that's very funny and once we get to the train chases, it's just gag after gag after gag. And they all work.

A potential drawback for modern viewers is that Keaton's playing a loyal Confederate in the Civil War. The movie isn't overtly political and the reasons for the war are never mentioned, but The General makes a strange companion piece to The Keeping Room , which also depicts the Union Army as the bad guys. I certainly don't want that to be the only - or even primary - way we talk about the Civil War, but I do think it's valuable and necessary to remember that there were multiple perspectives on that conflict.

Douglas Fairbanks plays a nobleman who pretends to be a pirate in order to take down the buccaneers responsible for his father's death. There's a love story too of course when they capture a ship with a princess aboard. And naturally our hero comes into conflict with the previous leader of the pirate gang, who also has an interest in the princess.

A lot of the elements are predictable, but there are complications to keep it interesting. And that's in addition to the amazingly athletic swashbuckling that Fairbanks is so excellent at. My print doesn't have a real score, but just some generic orchestral music, so that's my only complaint. One of the first pirate movies is also one of the best.

The Bat (1926)

I'm really fond of the 1959 version starring Vincent Price and Agnes Moorehead, so I wanted to see this one adapting the same play. Now I need to see the Price one again to compare, because I think I may actually like this one even better. The plot's basically the same - a killer called The Bat terrorizes a bunch of people in a mansion that may have a lot of money hidden in it somewhere - but the '26 version surprised me with how gorgeous it is. The sets are huge and extravagant, the shots are dark and stylish, and the Bat's costume is amazing: basically a trench-coated man who wears an elaborate bat mask with huge, fur-covered ears and a working mouth.

My only issue with the film was the soundtrack on the print I watched. I rented it from Amazon where the score is relentlessly dull trance music that kept putting me to sleep. It's atmospheric, but doesn't go well with the movie's many comedic moments. I was captivated by the story and the look of the film, so I persevered, but finally muted the sound and listened to some Sisters of Mercy while I watched. It still didn't fit perfectly, but at least it wasn't boring.

It’s the Old Army Game (1926)

So that's me smitten with Louise Brooks then.

I wanted to check out some Brooks movies and started with this one because it's the earliest that I have access to. I'm also familiar enough with WC Fields to know that I generally like him, so that made it a safe introduction, too.

There's a loose plot about Fields' character getting involved with a land scheme (the movie's title refers to con games), but mostly it's a series of unrelated gags that go on longer than they should. Like when Fields takes his family out for a picnic and has it on the lawn of some rich guy's house. The running joke about the animosity between Fields and his young nephew is especially tiring. The actor playing the nephew was 11, but the character sleeps in a crib and rides in a baby carriage part of the time, so I don't know how old he's supposed to be.

The frustrations are all worth it whenever Brooks shows up though. She's beautiful and charming and absolutely captivating every time she's on screen. Looking forward to seeing some of her other films.

Battling Butler (1926)

A really early version of the tropey romantic comedy formula where a misunderstanding or lie snowballs and threatens to break up our couple if the secret gets out. And rather than having a grown-up conversation about it, the lead character perpetuates the lie, breaking the other person's heart and requiring a big gesture to set things right.

Because it's Buster Keaton, it still works for me, but it relies more on the situation for laughs than on Keaton's physicality. In fact, Keaton's playing a wimp, so his athleticism is intentionally de-emphasized.

The General (1926)

This one's probably the first Buster Keaton movie I ever saw. It's a great introduction because it's essentially a feature-length chase scene. (I've heard it compared to Mad Max: Fury Road, which is kind of appropriate.) There's some introductory stuff to set the stakes, but even that's very funny and once we get to the train chases, it's just gag after gag after gag. And they all work.

A potential drawback for modern viewers is that Keaton's playing a loyal Confederate in the Civil War. The movie isn't overtly political and the reasons for the war are never mentioned, but The General makes a strange companion piece to The Keeping Room , which also depicts the Union Army as the bad guys. I certainly don't want that to be the only - or even primary - way we talk about the Civil War, but I do think it's valuable and necessary to remember that there were multiple perspectives on that conflict.

Published on May 09, 2016 04:00

May 6, 2016

Panels and Pizza with Adam Vermillion (and me)

The Twin Cities area has a fantastic comics community from its excellent shops and enthusiastic fans to its vibrant creators and great local conventions. Podcaster Adam Vermillion celebrates that community every week by getting together with a local creator to have some pizza and talk some comics on his Panels and Pizza podcast. It's a fun format and I'm super happy that he invited me to join him for the latest episode.

We talk about Kill All Monsters, of course, but also Alpha Flight and why Bronze Age comics are awesome. I pitch my dream Marvel writing gig and we also get into podcasting in general and the pizza we enjoyed. It was a great time and I think that comes through in the episode. Thanks again to Adam for having me on!

Published on May 06, 2016 04:00

May 5, 2016

British History in Film | Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) and Robin Hood (2010)

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)

This one gets laughed at quite a bit, but I love it, even with its American Robin Hood. That has a lot to do with Alan Rickman, of course, though his Sheriff crosses from merely ambitiously evil into some truly creepy and despicable territory. That's the script and not Rickman's performance, but it does keep me from wholeheartedly enjoying that character.

I also love Michael Kamen's score and even the cheesy Brian Adams song, "(Everything I Do) I Do It For You." It's the one Brian Adams song I've ever liked, but I like it without reservation. Probably because of it's association with this movie.

On top of all that are some great set pieces. There's plenty not to like, too, but over all it's the big budget, spectacular Robin Hood that I wanted and it still holds up.

Robin Hood (2010)

It's barely a Robin Hood movie, but I still enjoy it as simply a medieval adventure. Ridley Scott is always visually exciting and I'm a huge fan of most of the cast from Russell Crowe and Cate Blanchett to Max von Sydow, Mark Strong, Oscar Isaac, Mark Addy, Matthew Macfadyen, Kevin Durand, and Léa Seydoux. I even really like William Hurt in it and that's not something I can usually say about his movies. Also, the music is great, thanks to musician/actor (and appropriately named) Alan Doyle as the minstrel Allan A'Dayle.

Something interesting that Scott's movie does is place the action after the death of King Richard. Prince John is now King John, but no less spoiled and oppressive. Next week, we'll check in on him again during his later reign via Shakespeare.

This one gets laughed at quite a bit, but I love it, even with its American Robin Hood. That has a lot to do with Alan Rickman, of course, though his Sheriff crosses from merely ambitiously evil into some truly creepy and despicable territory. That's the script and not Rickman's performance, but it does keep me from wholeheartedly enjoying that character.

I also love Michael Kamen's score and even the cheesy Brian Adams song, "(Everything I Do) I Do It For You." It's the one Brian Adams song I've ever liked, but I like it without reservation. Probably because of it's association with this movie.

On top of all that are some great set pieces. There's plenty not to like, too, but over all it's the big budget, spectacular Robin Hood that I wanted and it still holds up.

Robin Hood (2010)

It's barely a Robin Hood movie, but I still enjoy it as simply a medieval adventure. Ridley Scott is always visually exciting and I'm a huge fan of most of the cast from Russell Crowe and Cate Blanchett to Max von Sydow, Mark Strong, Oscar Isaac, Mark Addy, Matthew Macfadyen, Kevin Durand, and Léa Seydoux. I even really like William Hurt in it and that's not something I can usually say about his movies. Also, the music is great, thanks to musician/actor (and appropriately named) Alan Doyle as the minstrel Allan A'Dayle.

Something interesting that Scott's movie does is place the action after the death of King Richard. Prince John is now King John, but no less spoiled and oppressive. Next week, we'll check in on him again during his later reign via Shakespeare.

Published on May 05, 2016 18:00

May 4, 2016

The Radio Man: Questions and Answers [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

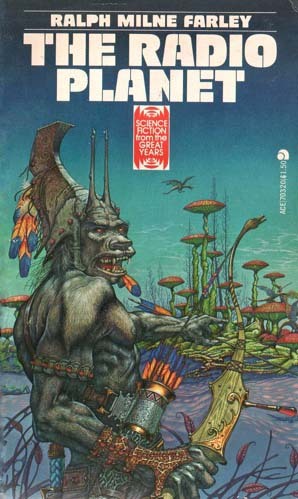

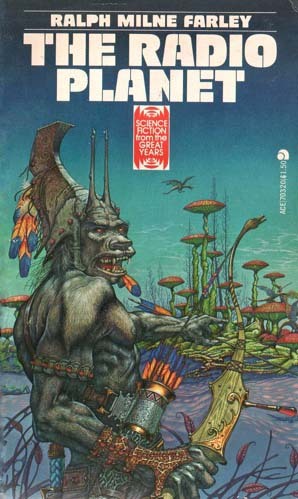

Edgar Rice Burroughs was a master of the jungle and interplanetary adventure. It is only natural he should have imitators. The most famous (or perhaps obvious) was Otis Adelbert Kline. But before Kline wrote of his imaginary Venus, another writer staked that territory with a long-running saga called The Radio Series. That writer was Ralph Milne Farley, pseudonym of Roger Sherman Hoar (1887-1963). Hoar has sparked many questions for me ever since I first encountered him in the old Ace paperbacks, The Radio Beasts and The Radio Planet (1964). The first novel begins with a recap of what was obviously a preceding story not included in those books. The questions begin... where was the first story?

Edgar Rice Burroughs was a master of the jungle and interplanetary adventure. It is only natural he should have imitators. The most famous (or perhaps obvious) was Otis Adelbert Kline. But before Kline wrote of his imaginary Venus, another writer staked that territory with a long-running saga called The Radio Series. That writer was Ralph Milne Farley, pseudonym of Roger Sherman Hoar (1887-1963). Hoar has sparked many questions for me ever since I first encountered him in the old Ace paperbacks, The Radio Beasts and The Radio Planet (1964). The first novel begins with a recap of what was obviously a preceding story not included in those books. The questions begin... where was the first story?

The second question was why the pseudonym? Why was "Ralph Milne Farley" better than "Roger Sherman Hoar". Both have the same ring of the Victorian novelist to it. Hoar was a member of a family of well-respected lawyers and politicians. He was a state senator in Massachusetts as well as Assistant Attorney General, and the inventor of a guided missile system used in WWII. His relative, Roger Sherman, was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. I can only conclude that he might have been trying to protect that well-respected name from being tarnished by such an activity as writing for the "soft magazines," as pulps were known then.

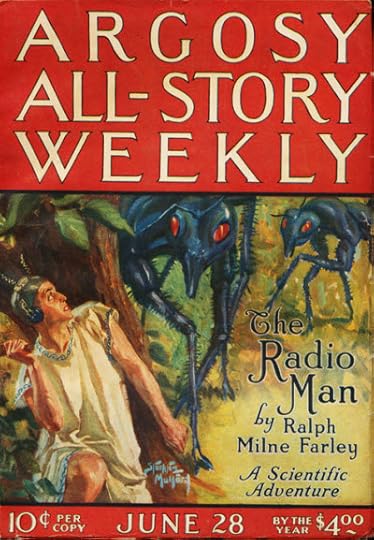

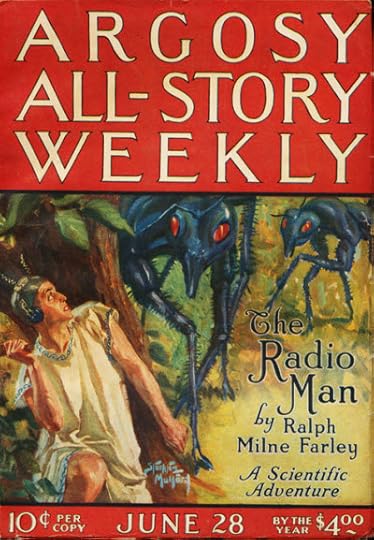

Delving deeper, I came up with many more points. First off, why is it the "Radio Series"? The stories originally appeared in Argosy/All-Story, June 28-July 19, 1924. 1924 was an important year for radio as a public medium. The invention goes back into the 1890s, but the first public broadcasts began in 1924 (January 5: the BBC broadcasts a church sermon; January 15: the BBC does the world's first radio drama, Danger; February 12: the first commercially-sponsored program, the Eveready Hour airs). Farley, seeing the writing on the wall, decides he will use radio technology to send his hero into the universe. (William Gibson would do a similar job for the Internet with Neuromancer in 1984.)

The next question I had revolved around an event in my own life. Back in the early 2000s I had a successful book-selling operation through eBay. One of my customers was the granddaughter of Roger Sherman Hoar, trying to find copies of his work. I must suppose that the old lawyers of the family had not thought Ralph's work worthy of notice, and allowed the copyrights to lapse. (An odd thing for lawyers to do, but not those that find old science fiction stories silly.) Why had the family lost track of this part of their history?

The next question I had revolved around an event in my own life. Back in the early 2000s I had a successful book-selling operation through eBay. One of my customers was the granddaughter of Roger Sherman Hoar, trying to find copies of his work. I must suppose that the old lawyers of the family had not thought Ralph's work worthy of notice, and allowed the copyrights to lapse. (An odd thing for lawyers to do, but not those that find old science fiction stories silly.) Why had the family lost track of this part of their history?

Another question I had was: what did Edgar Rice Burroughs think of this series? It turns out that Farley became a friend of Burroughs. (Irwin Porges makes no mention of him in Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Man Who Created Tarzan (1975), but according to Den Valdron's excellent overview of the series, Farley was "actually a close friend of Edgar Rice Burroughs." Through the Milwaukee Fictioneers he also knew Ray Palmer, Robert Bloch and Stanley G Weinbaum (with whom he collaborated). Unlike many pulp slaves, Hoar wrote out of interest and did not need the money. This explains some of the diversity of his work, appearing in Weird Tales as often as Argosy.

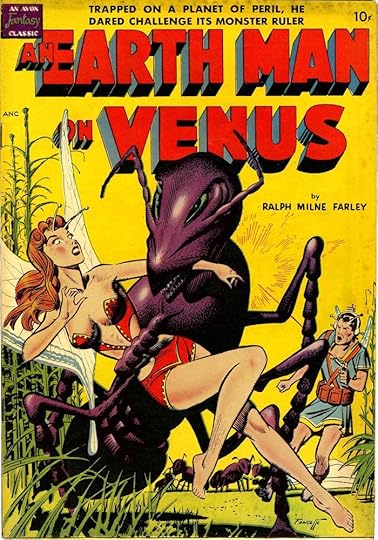

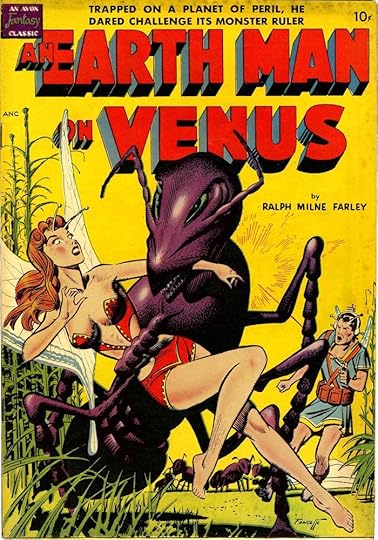

Lastly, I came across a comic book adaptation of the first tale, done by Wally Wood for Avon Fantasy (1951). Actually, I found the reprinted version in Strange Planets #11 (1963). (Ralph's only other comic book appearance is a three-page text reprint, "Abductor Minimi Digit," reprinted in Witches Tales Volume 3 Number 4 (August 1971), originally in Weird Tales, January 1932.) How did the story come to be adapted? Farley was still alive in 1951 and his reaction to the piece may have been interesting. Wood's work is not his best, but even poorly executed Wally Wood is better than most.

But lets go to the beginning and look at the Radio saga. The series features Myles Cabot (did John Norman's Tarl Cabot come from Farley?), a radio inventor and operator who has an accident with his radio equipment that transports him John Carter of Mars-style to the distant planet of Venus. Venus is inhabited by giant insects who war with each other. Cabot falls in with the ants, only to find the humans of Venus are their slaves. Joining the Cupians (humans), Cabot shows them how to use gun powder and frees them. He of course wins the princess, too.

But lets go to the beginning and look at the Radio saga. The series features Myles Cabot (did John Norman's Tarl Cabot come from Farley?), a radio inventor and operator who has an accident with his radio equipment that transports him John Carter of Mars-style to the distant planet of Venus. Venus is inhabited by giant insects who war with each other. Cabot falls in with the ants, only to find the humans of Venus are their slaves. Joining the Cupians (humans), Cabot shows them how to use gun powder and frees them. He of course wins the princess, too.

The first segment, "The Radio Man" appeared in Argosy/All-Story in 1924. (This novel and some of the sequels were reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries and Famous Novels.) For some reason this story was never used by ACE Books in the 1960s, despite being the perfect size for inclusion. This feeling of incompleteness made me (and perhaps other readers) reluctant to start the series for many years. The truth may be the story was not available as it had appeared in hard cover in 1948 and at rival paperback publishing Avon in 1950.

The next two volumes comprise what most people consider the bulk of the series in paperback. The Radio Beasts ( March 21-April 11, 1925) and The Radio Planet (June 26-July 31, 1926) continue the Burroughsian-style story with all the fannish love that we would not see again until Lin Carter wrote his Jandar of Callisto books and the Green Star series, both in 1972.

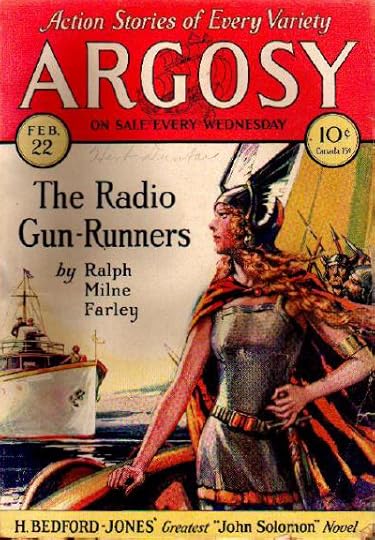

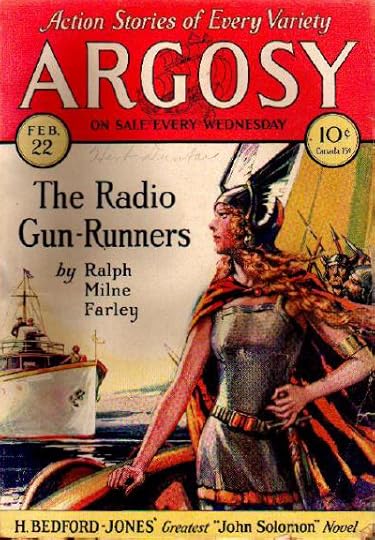

More adventures came later, not in novel length, but as short stories and novellas with The Radio Flyers (May 11-June 8, 1928), The Radio Gun-Runners (February 22 - March 29, 1930), and The Radio Menace (June 7- July 12, 1930). The stories also moved away from giant insects and moved onto earthly invasion by the Whoomangs, animals controlled by intelligent slugs. None of these stories were reprinted by ACE, though they would have made great doubles. Perhaps the sales of Beasts and Planet had been poor (not surprisingly).

More adventures came later, not in novel length, but as short stories and novellas with The Radio Flyers (May 11-June 8, 1928), The Radio Gun-Runners (February 22 - March 29, 1930), and The Radio Menace (June 7- July 12, 1930). The stories also moved away from giant insects and moved onto earthly invasion by the Whoomangs, animals controlled by intelligent slugs. None of these stories were reprinted by ACE, though they would have made great doubles. Perhaps the sales of Beasts and Planet had been poor (not surprisingly).

Farley wrote more full-length novels including The Radio War (July 2- July 30, 1932). Its missing first chapter was printed in Fantasy Magazine (February 1934). The Golden City (May 13-June 17, 1933) was oddly not named "Radio City," while Farley's name had become so associated with the word "Radio" it was attached to stories that weren't part of the series, such as The Radio Pirates in Argosy All-Story, August 1-August 22, 1931.

Getting long-in-the-tooth, the Burroughs clone was resurrected for Ray Palmer with The Radio Man Returns (1939) in Amazing Stories, June 1939. Farley was instrumental in Palmer's becoming editor of the magazine, so Palmer would have been pleased to return the favor. But this wasn't the last attempt for the denizens of Mars come to Venus. The Radio-Minds of Mars (1955) would appear in Spaceway (June 1955), then be reprinted in three issues of a new Spaceway magazine in January -September/October 1969, six years after Hoar's death.

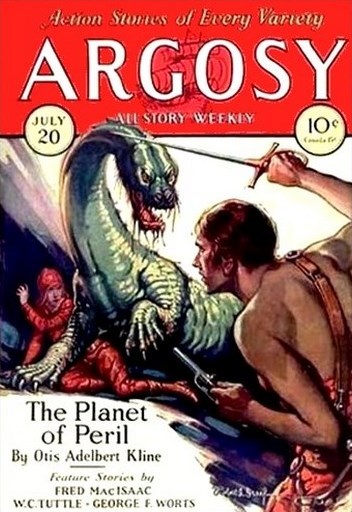

Though not the longest running series in SF (that title probably goes to Neil R Jones' Zoromes), the Radio Series is an interesting specimen of Argosy's desire to replicate Edgar Rice Burroughs' success (both interplanetary as well as jungle). They would do this slowly over time, first with Farley, then Kline, (they actually rejected Kline's first novel, The Planet of Peril, until 1929, because they had already purchased The Radio Man), JU Guisy, Charles B Stilson, and others. As Sam Moskowitz points out in his Under the Moons of Mars (1970), this stems from the rough handling that ERB received by Thomas Metcalf over The Outlaw of Torn and The Return of Tarzan:

Though not the longest running series in SF (that title probably goes to Neil R Jones' Zoromes), the Radio Series is an interesting specimen of Argosy's desire to replicate Edgar Rice Burroughs' success (both interplanetary as well as jungle). They would do this slowly over time, first with Farley, then Kline, (they actually rejected Kline's first novel, The Planet of Peril, until 1929, because they had already purchased The Radio Man), JU Guisy, Charles B Stilson, and others. As Sam Moskowitz points out in his Under the Moons of Mars (1970), this stems from the rough handling that ERB received by Thomas Metcalf over The Outlaw of Torn and The Return of Tarzan:

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Edgar Rice Burroughs was a master of the jungle and interplanetary adventure. It is only natural he should have imitators. The most famous (or perhaps obvious) was Otis Adelbert Kline. But before Kline wrote of his imaginary Venus, another writer staked that territory with a long-running saga called The Radio Series. That writer was Ralph Milne Farley, pseudonym of Roger Sherman Hoar (1887-1963). Hoar has sparked many questions for me ever since I first encountered him in the old Ace paperbacks, The Radio Beasts and The Radio Planet (1964). The first novel begins with a recap of what was obviously a preceding story not included in those books. The questions begin... where was the first story?

Edgar Rice Burroughs was a master of the jungle and interplanetary adventure. It is only natural he should have imitators. The most famous (or perhaps obvious) was Otis Adelbert Kline. But before Kline wrote of his imaginary Venus, another writer staked that territory with a long-running saga called The Radio Series. That writer was Ralph Milne Farley, pseudonym of Roger Sherman Hoar (1887-1963). Hoar has sparked many questions for me ever since I first encountered him in the old Ace paperbacks, The Radio Beasts and The Radio Planet (1964). The first novel begins with a recap of what was obviously a preceding story not included in those books. The questions begin... where was the first story?The second question was why the pseudonym? Why was "Ralph Milne Farley" better than "Roger Sherman Hoar". Both have the same ring of the Victorian novelist to it. Hoar was a member of a family of well-respected lawyers and politicians. He was a state senator in Massachusetts as well as Assistant Attorney General, and the inventor of a guided missile system used in WWII. His relative, Roger Sherman, was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. I can only conclude that he might have been trying to protect that well-respected name from being tarnished by such an activity as writing for the "soft magazines," as pulps were known then.

Delving deeper, I came up with many more points. First off, why is it the "Radio Series"? The stories originally appeared in Argosy/All-Story, June 28-July 19, 1924. 1924 was an important year for radio as a public medium. The invention goes back into the 1890s, but the first public broadcasts began in 1924 (January 5: the BBC broadcasts a church sermon; January 15: the BBC does the world's first radio drama, Danger; February 12: the first commercially-sponsored program, the Eveready Hour airs). Farley, seeing the writing on the wall, decides he will use radio technology to send his hero into the universe. (William Gibson would do a similar job for the Internet with Neuromancer in 1984.)

The next question I had revolved around an event in my own life. Back in the early 2000s I had a successful book-selling operation through eBay. One of my customers was the granddaughter of Roger Sherman Hoar, trying to find copies of his work. I must suppose that the old lawyers of the family had not thought Ralph's work worthy of notice, and allowed the copyrights to lapse. (An odd thing for lawyers to do, but not those that find old science fiction stories silly.) Why had the family lost track of this part of their history?

The next question I had revolved around an event in my own life. Back in the early 2000s I had a successful book-selling operation through eBay. One of my customers was the granddaughter of Roger Sherman Hoar, trying to find copies of his work. I must suppose that the old lawyers of the family had not thought Ralph's work worthy of notice, and allowed the copyrights to lapse. (An odd thing for lawyers to do, but not those that find old science fiction stories silly.) Why had the family lost track of this part of their history?Another question I had was: what did Edgar Rice Burroughs think of this series? It turns out that Farley became a friend of Burroughs. (Irwin Porges makes no mention of him in Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Man Who Created Tarzan (1975), but according to Den Valdron's excellent overview of the series, Farley was "actually a close friend of Edgar Rice Burroughs." Through the Milwaukee Fictioneers he also knew Ray Palmer, Robert Bloch and Stanley G Weinbaum (with whom he collaborated). Unlike many pulp slaves, Hoar wrote out of interest and did not need the money. This explains some of the diversity of his work, appearing in Weird Tales as often as Argosy.

Lastly, I came across a comic book adaptation of the first tale, done by Wally Wood for Avon Fantasy (1951). Actually, I found the reprinted version in Strange Planets #11 (1963). (Ralph's only other comic book appearance is a three-page text reprint, "Abductor Minimi Digit," reprinted in Witches Tales Volume 3 Number 4 (August 1971), originally in Weird Tales, January 1932.) How did the story come to be adapted? Farley was still alive in 1951 and his reaction to the piece may have been interesting. Wood's work is not his best, but even poorly executed Wally Wood is better than most.

But lets go to the beginning and look at the Radio saga. The series features Myles Cabot (did John Norman's Tarl Cabot come from Farley?), a radio inventor and operator who has an accident with his radio equipment that transports him John Carter of Mars-style to the distant planet of Venus. Venus is inhabited by giant insects who war with each other. Cabot falls in with the ants, only to find the humans of Venus are their slaves. Joining the Cupians (humans), Cabot shows them how to use gun powder and frees them. He of course wins the princess, too.

But lets go to the beginning and look at the Radio saga. The series features Myles Cabot (did John Norman's Tarl Cabot come from Farley?), a radio inventor and operator who has an accident with his radio equipment that transports him John Carter of Mars-style to the distant planet of Venus. Venus is inhabited by giant insects who war with each other. Cabot falls in with the ants, only to find the humans of Venus are their slaves. Joining the Cupians (humans), Cabot shows them how to use gun powder and frees them. He of course wins the princess, too.The first segment, "The Radio Man" appeared in Argosy/All-Story in 1924. (This novel and some of the sequels were reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries and Famous Novels.) For some reason this story was never used by ACE Books in the 1960s, despite being the perfect size for inclusion. This feeling of incompleteness made me (and perhaps other readers) reluctant to start the series for many years. The truth may be the story was not available as it had appeared in hard cover in 1948 and at rival paperback publishing Avon in 1950.

The next two volumes comprise what most people consider the bulk of the series in paperback. The Radio Beasts ( March 21-April 11, 1925) and The Radio Planet (June 26-July 31, 1926) continue the Burroughsian-style story with all the fannish love that we would not see again until Lin Carter wrote his Jandar of Callisto books and the Green Star series, both in 1972.

More adventures came later, not in novel length, but as short stories and novellas with The Radio Flyers (May 11-June 8, 1928), The Radio Gun-Runners (February 22 - March 29, 1930), and The Radio Menace (June 7- July 12, 1930). The stories also moved away from giant insects and moved onto earthly invasion by the Whoomangs, animals controlled by intelligent slugs. None of these stories were reprinted by ACE, though they would have made great doubles. Perhaps the sales of Beasts and Planet had been poor (not surprisingly).

More adventures came later, not in novel length, but as short stories and novellas with The Radio Flyers (May 11-June 8, 1928), The Radio Gun-Runners (February 22 - March 29, 1930), and The Radio Menace (June 7- July 12, 1930). The stories also moved away from giant insects and moved onto earthly invasion by the Whoomangs, animals controlled by intelligent slugs. None of these stories were reprinted by ACE, though they would have made great doubles. Perhaps the sales of Beasts and Planet had been poor (not surprisingly).Farley wrote more full-length novels including The Radio War (July 2- July 30, 1932). Its missing first chapter was printed in Fantasy Magazine (February 1934). The Golden City (May 13-June 17, 1933) was oddly not named "Radio City," while Farley's name had become so associated with the word "Radio" it was attached to stories that weren't part of the series, such as The Radio Pirates in Argosy All-Story, August 1-August 22, 1931.

Getting long-in-the-tooth, the Burroughs clone was resurrected for Ray Palmer with The Radio Man Returns (1939) in Amazing Stories, June 1939. Farley was instrumental in Palmer's becoming editor of the magazine, so Palmer would have been pleased to return the favor. But this wasn't the last attempt for the denizens of Mars come to Venus. The Radio-Minds of Mars (1955) would appear in Spaceway (June 1955), then be reprinted in three issues of a new Spaceway magazine in January -September/October 1969, six years after Hoar's death.

Though not the longest running series in SF (that title probably goes to Neil R Jones' Zoromes), the Radio Series is an interesting specimen of Argosy's desire to replicate Edgar Rice Burroughs' success (both interplanetary as well as jungle). They would do this slowly over time, first with Farley, then Kline, (they actually rejected Kline's first novel, The Planet of Peril, until 1929, because they had already purchased The Radio Man), JU Guisy, Charles B Stilson, and others. As Sam Moskowitz points out in his Under the Moons of Mars (1970), this stems from the rough handling that ERB received by Thomas Metcalf over The Outlaw of Torn and The Return of Tarzan:

Though not the longest running series in SF (that title probably goes to Neil R Jones' Zoromes), the Radio Series is an interesting specimen of Argosy's desire to replicate Edgar Rice Burroughs' success (both interplanetary as well as jungle). They would do this slowly over time, first with Farley, then Kline, (they actually rejected Kline's first novel, The Planet of Peril, until 1929, because they had already purchased The Radio Man), JU Guisy, Charles B Stilson, and others. As Sam Moskowitz points out in his Under the Moons of Mars (1970), this stems from the rough handling that ERB received by Thomas Metcalf over The Outlaw of Torn and The Return of Tarzan:Now it was Metcalf's turn to worry. The success of The All-Story Magazine depended upon Burroughs, and the maintenance of his own job depended on the continuance of The All-Story Magazine. It was evident that he was already out of his depth. He was handling a once-in-a-lifetime circulation booster like Burroughs with far less finesse than he exercised upon the scores of run-of-the-mill hacks that were grinding out an endless series of eminently forgettable stories for the new breed of pulps that were digesting millions upon millions of words per year.Munsey had a Burroughs exclusive and lost it by not realizing what they had in old Ed Burroughs. If they couldn't guarantee his work, they would try and duplicate it. But is Ralph Milne Farley a fair duplicate of ERB? This of course is a matter of opinion, but are any of the imitators close to Burroughs? I would say Farley was better than Kline, but certainly no better than most ERB wannabes. Even the Fritz Leiber and Joe R Lansdales fall short, perhaps not because they aren't good writers, but because they simply aren't ERB. Ralph Milne Farley may have been the first to try out of fannish love for Burroughs work, but in the end he is one of many reliable also-rans.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on May 04, 2016 18:00

May 2, 2016

The Year in Movies: 1925

Since most of my 7 Days in May posts have been around the massive silent movie kick I'm on lately, I'm weeding out the extra stuff and am just going to concentrate on sharing the silents. I think that makes a better post than a miscellaneous hodge podge of stuff. And since I've been working my way through the silents chronologically, it makes sense to re-title this The Year in Movies. Here are the movies from 1925 that I've recently checked out (or rewatched).

Seven Chances (1925)

This Buster Keaton feature starts off as a romantic comedy in which Keaton's character needs to get married by a certain time in order to inherit seven million dollars. The jokes in that part are all about his proposing to various women at his country club and getting turned down, hilariously.

Then one of his buddies hits on the idea of putting out an ad that attracts probably about a hundred women. At that point, it becomes a chase movie as they run Keaton through the streets and across the countryside. And it's a brilliant, funny chase, too (way better than the one in Cops), especially when the rock slide starts.

There are some racist gags that I wish weren't in there, but generally it's one of Keaton's stronger movies.

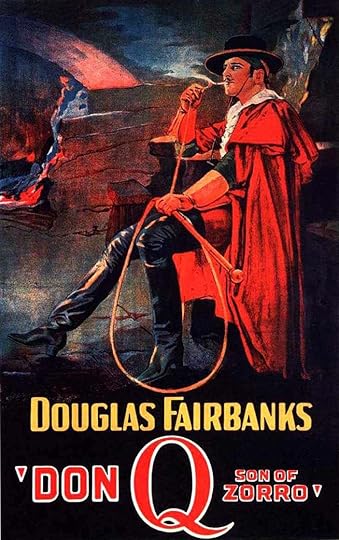

Don Q: Son of Zorro (1925)

Put it on the list of sequels that are better than the original. Fairbanks' Mark of Zorro is amazing and fun, but Don Q goes to another level with a more intricate plot, a great group of characters, and even better actors to play them. I cared a lot about the people in this story, despairing and cheering right alongside them.

I'm glad I don't have to choose between Douglas Fairbanks and Buster Keaton for whose athleticism I admire more. I've said before that Fairbanks may not be as handsome as some of the swashbucklers who followed him, but he rules them all in terms of energy and sheer physical impressiveness. He's the definition of swashbuckler, always full of life and joy - even in the darkest moments - and never willing to walk or climb when a leap will get him there faster.

The Lost World (1925)

I really thought I'd seen this before, but didn't recall it as I was watching and think I would have. It's about half-faithful to the Arthur Conan Doyle story it's adapting with Wallace Beery (whom I know as King Richard from Douglas Fairbanks' Robin Hood) as a great Professor Challenger. He's physically imposing with a perpetual, angry brood on his face most of the time. The other actors are great as well, but the real stars are the makeup and special effects.

Bull Montana is legitimately frightening in his ape-man makeup by Cecil Holland, and legendary effects artist Willis O'Brien (who'd go on to supervise the visual effects for King Kong) worked on the charming stop-motion dinosaurs. The dinosaurs are so great that I'm glad the movie modified the end of the story by having a brontosaurus rampage through London (another foreshadow of King Kong).

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

Seen this one a million times, but the sets and costumes are still spectacular and it's creepy in all the right places. Chaney is magnificent; equal parts evil and pathetic. Christine is flighty and pretty dumb, but her shenanigans just add to my enjoyment.

The Unholy Three (1925)

It may star Lon Chaney and be directed by Tod Browning, but The Unholy Three is no horror movie. It's a crime story, just with the twist that the trio of criminals in the title met in a sideshow act. Chaney plays Professor Echo, a ventriloquist who teams up with a little person and a strong man to pull elaborate burglaries, using a pet store as a front.

Complicating the situation is Echo's girlfriend, Rosie, an official member of the gang who's spending more time than Echo likes with Hector, the pet store clerk whom Echo's keeping around as a possible fall guy if things go wrong.

There's a lot that has to be overlooked to enjoy the movie. The way ventriloquism and courtrooms work, for instance. But there's a great, emotional core that keeps it interesting and makes it worthwhile. When allegiances shift - and boy do they - it always feels natural and because of who the characters are. Now I'm curious to see the 1930 remake that brought back Chaney and the three-foot Harry Earles with sound.

Go West (1925)

A very sweet story about the relationship between a friendless man and a brown-eyed cow. I love Buster Keaton's usual romantic shenanigans, but Go West is a refreshing change of pace. Though there is a woman, of course, and that story is sweetly told, too.

Wolf Blood (1925)

Wolf Blood (Wolfblood?) has even less to do with werewolves than the infamous She-Wolf of London, because that one at least starts its misdirection early on. Wolfblood spends most of its time creating drama between rival lumber operations and setting up romance between its lead characters. The lycanthrope element is tossed in towards the end as a romantic foil more than anything else.

But at least it has a pretty great character in Edith Ford, a flapper who also owns one of the lumber companies. In fact, if the movie had just been about her trying to decide between her surgeon fiancé and the handsome foreman of her company, I would have liked the movie better. Like She-Wolf, my biggest problem is its trying to squeeze in a supernatural plot and being half-hearted about it.

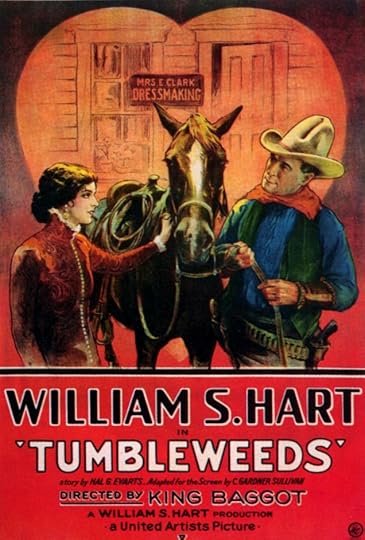

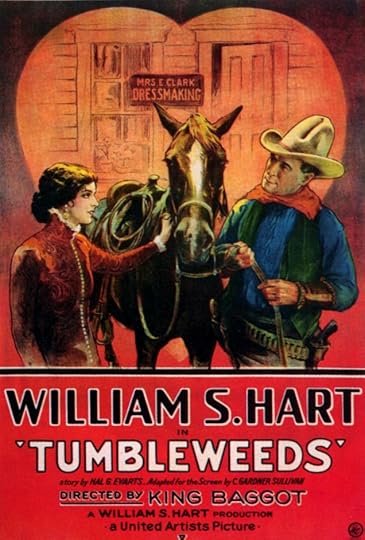

Tumbleweeds (1925)

A cool silent film covering the same events as the finale of Far and Away, which I have fond memories of and need to watch again.

Tumbleweeds makes a nice companion piece to The Covered Wagon, which also has people in covered wagons looking for a place to settle down. But in Covered Wagon they're opening up the frontier in the 1840s, while Tumbleweeds has them filling it in 50 years later.

I'd never seen a William S Hart movie before and I can see now why he was a big Western star. He's got a kind face, but a tough attitude. I doubt I'll track down his other movies, but I liked him in this.

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)

Like with the two Ten Commandments movies, I've always wanted to see the original Ben-Hur. Now that I have, I'm pretty sure I like it better than the Charlton Heston version. It's been a long time since I've seen Heston's, but I'm not a huge fan of him anyway and Ramon Novarro is extremely handsome and appealing as the title character.

I can see why William Wyler's remaking it was a good idea with new technology (and am curious to see how Timur Bekmambetov will do it again this year), but Fred Niblo totally got it right the first time. It wraps up too neatly and conveniently for me, but it's got all the spectacle and it's well-acted.

Seven Chances (1925)

This Buster Keaton feature starts off as a romantic comedy in which Keaton's character needs to get married by a certain time in order to inherit seven million dollars. The jokes in that part are all about his proposing to various women at his country club and getting turned down, hilariously.

Then one of his buddies hits on the idea of putting out an ad that attracts probably about a hundred women. At that point, it becomes a chase movie as they run Keaton through the streets and across the countryside. And it's a brilliant, funny chase, too (way better than the one in Cops), especially when the rock slide starts.

There are some racist gags that I wish weren't in there, but generally it's one of Keaton's stronger movies.

Don Q: Son of Zorro (1925)

Put it on the list of sequels that are better than the original. Fairbanks' Mark of Zorro is amazing and fun, but Don Q goes to another level with a more intricate plot, a great group of characters, and even better actors to play them. I cared a lot about the people in this story, despairing and cheering right alongside them.

I'm glad I don't have to choose between Douglas Fairbanks and Buster Keaton for whose athleticism I admire more. I've said before that Fairbanks may not be as handsome as some of the swashbucklers who followed him, but he rules them all in terms of energy and sheer physical impressiveness. He's the definition of swashbuckler, always full of life and joy - even in the darkest moments - and never willing to walk or climb when a leap will get him there faster.

The Lost World (1925)

I really thought I'd seen this before, but didn't recall it as I was watching and think I would have. It's about half-faithful to the Arthur Conan Doyle story it's adapting with Wallace Beery (whom I know as King Richard from Douglas Fairbanks' Robin Hood) as a great Professor Challenger. He's physically imposing with a perpetual, angry brood on his face most of the time. The other actors are great as well, but the real stars are the makeup and special effects.

Bull Montana is legitimately frightening in his ape-man makeup by Cecil Holland, and legendary effects artist Willis O'Brien (who'd go on to supervise the visual effects for King Kong) worked on the charming stop-motion dinosaurs. The dinosaurs are so great that I'm glad the movie modified the end of the story by having a brontosaurus rampage through London (another foreshadow of King Kong).

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

Seen this one a million times, but the sets and costumes are still spectacular and it's creepy in all the right places. Chaney is magnificent; equal parts evil and pathetic. Christine is flighty and pretty dumb, but her shenanigans just add to my enjoyment.

The Unholy Three (1925)

It may star Lon Chaney and be directed by Tod Browning, but The Unholy Three is no horror movie. It's a crime story, just with the twist that the trio of criminals in the title met in a sideshow act. Chaney plays Professor Echo, a ventriloquist who teams up with a little person and a strong man to pull elaborate burglaries, using a pet store as a front.

Complicating the situation is Echo's girlfriend, Rosie, an official member of the gang who's spending more time than Echo likes with Hector, the pet store clerk whom Echo's keeping around as a possible fall guy if things go wrong.

There's a lot that has to be overlooked to enjoy the movie. The way ventriloquism and courtrooms work, for instance. But there's a great, emotional core that keeps it interesting and makes it worthwhile. When allegiances shift - and boy do they - it always feels natural and because of who the characters are. Now I'm curious to see the 1930 remake that brought back Chaney and the three-foot Harry Earles with sound.

Go West (1925)

A very sweet story about the relationship between a friendless man and a brown-eyed cow. I love Buster Keaton's usual romantic shenanigans, but Go West is a refreshing change of pace. Though there is a woman, of course, and that story is sweetly told, too.

Wolf Blood (1925)

Wolf Blood (Wolfblood?) has even less to do with werewolves than the infamous She-Wolf of London, because that one at least starts its misdirection early on. Wolfblood spends most of its time creating drama between rival lumber operations and setting up romance between its lead characters. The lycanthrope element is tossed in towards the end as a romantic foil more than anything else.

But at least it has a pretty great character in Edith Ford, a flapper who also owns one of the lumber companies. In fact, if the movie had just been about her trying to decide between her surgeon fiancé and the handsome foreman of her company, I would have liked the movie better. Like She-Wolf, my biggest problem is its trying to squeeze in a supernatural plot and being half-hearted about it.

Tumbleweeds (1925)

A cool silent film covering the same events as the finale of Far and Away, which I have fond memories of and need to watch again.

Tumbleweeds makes a nice companion piece to The Covered Wagon, which also has people in covered wagons looking for a place to settle down. But in Covered Wagon they're opening up the frontier in the 1840s, while Tumbleweeds has them filling it in 50 years later.

I'd never seen a William S Hart movie before and I can see now why he was a big Western star. He's got a kind face, but a tough attitude. I doubt I'll track down his other movies, but I liked him in this.

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)

Like with the two Ten Commandments movies, I've always wanted to see the original Ben-Hur. Now that I have, I'm pretty sure I like it better than the Charlton Heston version. It's been a long time since I've seen Heston's, but I'm not a huge fan of him anyway and Ramon Novarro is extremely handsome and appealing as the title character.

I can see why William Wyler's remaking it was a good idea with new technology (and am curious to see how Timur Bekmambetov will do it again this year), but Fred Niblo totally got it right the first time. It wraps up too neatly and conveniently for me, but it's got all the spectacle and it's well-acted.

Published on May 02, 2016 18:00

April 30, 2016

See It. Hear It. Feel It. Podcast It.

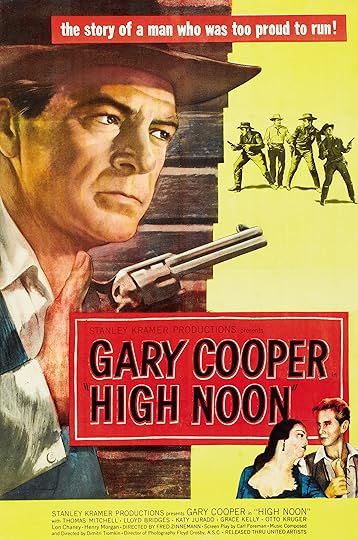

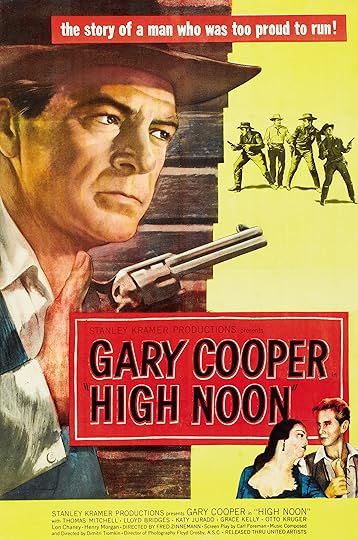

Hellbent for Letterbox: High Noon

This was a busy week of podcasting. On Monday, a new episode of Hellbent for Letterbox came out in which Pax and I talk about the Gary Cooper classic, High Noon. But though it may be a classic, we had some big issues with it.

Then we followed that up later in the week with a supplemental episode (we call 'em "Hitching Posts") about a couple of movies that were inspired by High Noon. Sean Connery's Outland is a scifi film with a Western feel that pays homage to High Noon, and then there's the TV movie sequel, High Noon, Part II: The Return of Will Kane starring Lee Majors, Pernell Roberts, and David Carradine. Guess which one we liked more.

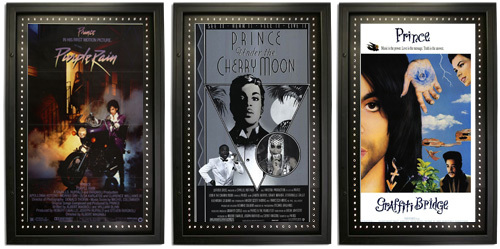

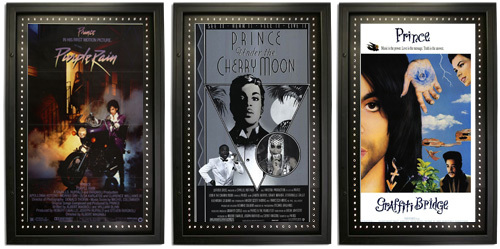

Mystery Movie Night: Purple Rain, Under the Cherry Moon, and Graffiti Bridge

The death of Prince put the Mystery Movie Night crew in the mood to watch his movies and talk about them, so we did. Sadly, Erik wasn't able to join us for this one, but he was there in spirit and we had a great discussion about our respect for Prince and the merits and flaws of his films.

Starmageddon, Episode 30

And finally, the latest episode of Starmageddon rolled out in which we talk about the Rogue One trailer, the trailer for Adam Nimoy's For the Love of Spock documentary, and rumors about the setting and format of the new Star Trek TV series. Are we excited? Uneasy? Only one way to find out.

This was a busy week of podcasting. On Monday, a new episode of Hellbent for Letterbox came out in which Pax and I talk about the Gary Cooper classic, High Noon. But though it may be a classic, we had some big issues with it.

Then we followed that up later in the week with a supplemental episode (we call 'em "Hitching Posts") about a couple of movies that were inspired by High Noon. Sean Connery's Outland is a scifi film with a Western feel that pays homage to High Noon, and then there's the TV movie sequel, High Noon, Part II: The Return of Will Kane starring Lee Majors, Pernell Roberts, and David Carradine. Guess which one we liked more.

Mystery Movie Night: Purple Rain, Under the Cherry Moon, and Graffiti Bridge

The death of Prince put the Mystery Movie Night crew in the mood to watch his movies and talk about them, so we did. Sadly, Erik wasn't able to join us for this one, but he was there in spirit and we had a great discussion about our respect for Prince and the merits and flaws of his films.

Starmageddon, Episode 30

And finally, the latest episode of Starmageddon rolled out in which we talk about the Rogue One trailer, the trailer for Adam Nimoy's For the Love of Spock documentary, and rumors about the setting and format of the new Star Trek TV series. Are we excited? Uneasy? Only one way to find out.

Published on April 30, 2016 07:25

April 27, 2016

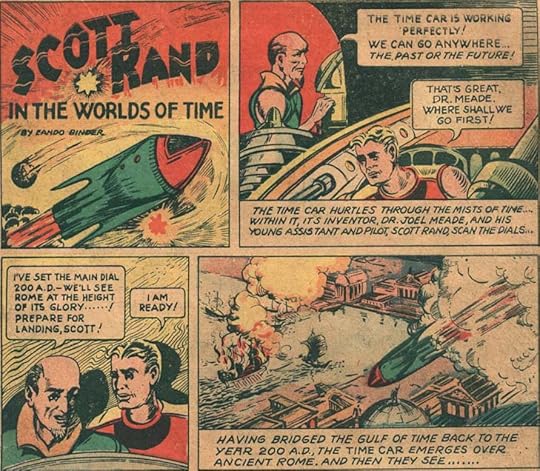

Scott Rand in the World of Time [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

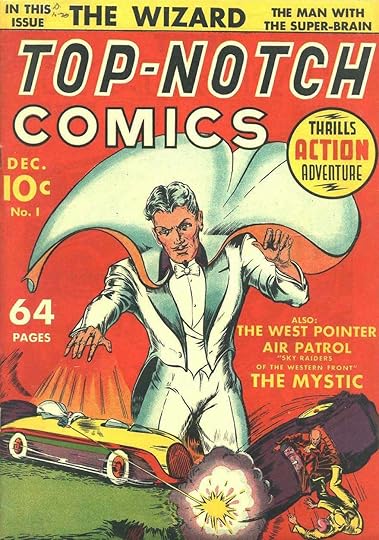

Comics in the late 1930s and early 1940s were a mixed bag. Having spectacular names, promising great entertainment inside, they were generally collections of stock types from the newspaper comic strips, movies, and radio. Each title had to have its Mandrake knock-off, a jungle lord or lady, a Western hero, a naval hero, etc. Amongst these types was the space hero, usually dressed in a one-piece with a fin on the hood. Sporting a ray gun, he rescued space maidens and thwarted the all-too Asian-looking Martians.

Comics in the late 1930s and early 1940s were a mixed bag. Having spectacular names, promising great entertainment inside, they were generally collections of stock types from the newspaper comic strips, movies, and radio. Each title had to have its Mandrake knock-off, a jungle lord or lady, a Western hero, a naval hero, etc. Amongst these types was the space hero, usually dressed in a one-piece with a fin on the hood. Sporting a ray gun, he rescued space maidens and thwarted the all-too Asian-looking Martians.

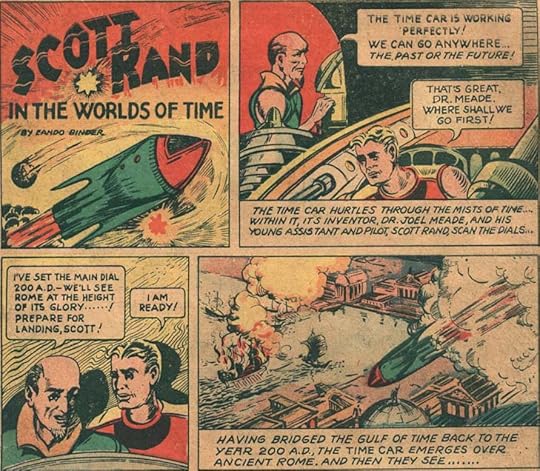

Most of the early science fiction comics are just plain bad. Minor versions of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, they are sadly dated today. It's easy to see why SF historians have written them off as largely irrelevant. Still, they are a weak reflection of what science fiction was in the early pulp years. One comic that I find fascinating in this regard is "Scott Rand and the World of Time" by Otto Binder (writing under the Eando Binder pseudonym) with artwork by his older brother, Jack. The three segments that comprise this masterpiece of silliness appeared in Top-Notch Comics #1-3 (December1939-February 1940).

What makes this particular comic interesting is the timing. Jack Binder had previously written and drawn (as Max Plastid) the "Zarnak" comic for Thrilling Wonder Stories in 1936. After that stint, he drew comics for the Harry A Chesler shop, which "Scott Rand" was produced for. This group of creators wrote and drew comics, then sold them to packagers such as MJL who produced Top-Notch Comics. In many ways, Scott Rand's adventures were a continuation of Zarnak's, featuring similar ships and costumes in color.

Also at the same time, Otto Binder was creating science fiction history at Amazing Stories with his tales of Adam Link, the robot ("I, Robot" had appeared in January of 1939). Goofy by today's post-Asimovian standards, these stories were an important watershed for robot characters. So why was Otto Binder writing script for Harry Chesler? In 1939, there were only three solid and reliable SF magazines: Amazing Stories, Astounding Science Fiction, and Thrilling Wonder Stories. More pulps were on the way, but it was almost impossible to write SF full-time. Otto had to have more markets, and instead of writing Westerns he turned to the pulp's little brother, comics. He would leave Chesler in 1941 to become the top writer of Captain Marvel at Fawcett and later work for DC on the Superman line. Jack Binder left Chesler as well in 1940 to work for Fawcett, Lev Gleason, and Timely, where he worked on the original Daredevil. He would create his own comic shop in 1942 until his retirement.