Janine Robinson's Blog, page 24

July 22, 2013

English Teachers Don’t Always Get It Write

At our local public high school, the English teachers assign juniors to write college application essays at the end of the year–one for the Common App and one for the UCs. It’s a great idea. For many students, this may be the only time they get any guidance on how to write these essays. (I don’t how many other high schools even have students work on college application essays as part of their English curriculum.)

There’s only one problem. Many English teachers don’t know how to write–and can actually give advice that could lead to inferior essays. I’ve seen many students’ rough drafts in recent years, and some of the worst ones received A’s. That scares me. These students believed their essays were perfect, ready to send in with their applications. And these were the same students–with the highest GPAs, test scores and endless extracurriculars–applying to the most competitive schools where essays matter most.

It’s not their fault. Or their well-meaning teacher’s. The problem is that English teachers are mainly trained to understand literature and teach the mechanics of writing. They certainly know strong writing when they read it, and can analyze the meaning and highlight various literary devices. But many of them do not write themselves, at least not with the goal of getting others to read their writing for a single purpose, such as selling, informing or entertainment. (like professional writers, including authors, journalists, advertising/marketing/pr writers, etc.).

I don’t mean to insult English teachers. (My dad was an English professor and I’m a certified high school English teacher.) There are some teachers who can write and are talented at teaching writing. But not many. At least not certain types of writing. Most are best at academic writing, which is formal, dense and not always easy or inviting to read. You want the opposite in a college application essay.

An English teacher could certainly help you edit your essay to catch grammatical, spelling or syntax errors. But I would be aware that some teachers could steer you wrong when it comes to picking unique topics and how to write your essay. One student at a recent workshop shared a terrific “out-of-the-box” topic idea, and told us that her English teacher advised her against using it. That’s so sad!

I believe English teachers (and college counselors and parents) need to spend more time–and have support from their districts and administrators–learning what makes a powerful narrative essay, and find resources to help direct students on how to write them. They also need to be given the permission and time to have their students practice this type of creative writing long before college application essays are due. I love that students in English classes are required to read great literature. But instead of writing academic essays about the literature, why aren’t they taught how to write their own “literature” and stories?

It seems to me that if most students’ education is aimed at helping land them in a great college or university, that more energy should be spent on teaching them this style of writing. I can’t say if it’s right or wrong how much emphasis is put on these essays, but the current reality is that they often make all the difference in who gets in or not.

I also think public schools especially should teach this type of writing to keep a level playing field. Most private college admissions counselors now understand that narrative essays are the ticket, and the savvy ones advise and assist their students to write slice-of-life essays. It’s only fair that all students have access to this knowledge and advice.

I have written a guide that is intended to help students learn how to write a narrative style essay, called Escape Essay Hell! I’m happy to send any teacher, counselor or librarian who works for a public school a free copy of my ebook guide, as well as any college counselors who work with low-income students who don’t have access to writing assistance. Just email me at Janine@EssayHell.com.

Here are some other helpful resources on learning what makes great writing and how to do it yourself (all available on Amazon):

Ready to write your own narrative essay? Check out my Jumpstart Guide to help you get started.

July 18, 2013

Grab Your Readers with An Anecdote

College Application Essays

How to Write An Anecdote About Almost Anything

Before one of my college application essay writing workshops yesterday, I skimmed over some of the rough drafts the students had written last semester for their English classes. The writing was solid, the ideas strong. Yet the essays were all on the dull side.

If only someone had taught these kids how to use anecdotes, I thought. Often, you can pull an anecdote ( a mini true story) out of what you’ve already written and instantly transform it into an engaging read. And it can be a very everyday, simple event or moment.

I tried to think if anything of interest happened during our workshop to use as an example. In general, it was pretty uneventful, even (ahem) a bit boring. Then I remembered: The cat fell off the bookcase while I was talking. It had fallen asleep and slipped off. We all had a good laugh. So something did happen. Now, how would I write that as an anecdote? Is it possible to take such a mundane event like that and turn it into a mini-story? Let’s see.

How to Write An Anecdote

The trick to anecdotes is to gather some details. Start with the 5ws–who, what, when, where and why. Myself, five students and a cat. A writing workshop. One recent morning. In a house on a bookshelf. It fell off because it went to sleep and slid off.

Next, gather the sensory details to try to re-create the scene or setting. What did we see, hear, smell, feel, touch or sense? I didn’t see it fall since it was lying behind me. I heard a soft thud. I heard the students’ exclamation of surprise. I felt surprised. I didn’t touch or smell anything.

Now put these together. I find it helps to start by the “where” and then put yourself into the picture as well. Standing by the window? Sitting on the grass? Where were you when this event happened–for point of view. Remember, I was sitting in front of the cat. My students watched it happen.

Here’s how I would write an anecdote about this moment. It took me a couple attempts. I wrote it out, then took out words I didn’t need or want, moved sentences around, shortened some sentences, added a phrase to another. I read it aloud each time. I tried to vary sentence lengths between short and long, sticking more with the shorter sentences. I tried to think of this little moment visually–what it would have looked like as a piece of video. I tried to start as close to the peak of the action as possible and still have the event make sense with some background.

I had been talking for nearly an hour straight. My five writing students, all seated around a large table in front of me, were starting to fidget. Suddenly, I heard a soft thump and a commotion behind me. The students also jumped up in unison.

“What the heck?” I said as I craned my neck behind me.

Everyone started laughing. The 16-year-old black cat, Sammy, had fallen asleep on the bookshelf behind us and gradually slipped over the edge until he abruptly dropped to the floor. As the students laughed, we all watched Sammy shake his head a couple times, stunned from the impact, trying to shake off the rude awakening. Then he padded into the next room as though nothing had happened.

I couldn’t help but think later how it took a sleeping cat to wake everyone up.

I know this isn’t great writing or the most compelling anecdote you’ve ever read. But notice how it’s easy to read and keeps you moving forward. Why? Because something happened, and you want to know why and what happens next.

I also want you to see how to take the most simple event or moment and turn it into an engaging anecdote, simply by relating the details of what happened in a direct manner. There were countless other ways to describe this same moment, and that’s the beauty of an anecdote. It’s all in the telling, what details you share and what you want to emphasize.

If you want to practice your narrative writing skills, try crafting a couple anecdotes out of everyday incidents in your life. They don’t need to me super exciting or impressive. Just think of something that happened, say, when you were at the beach, or at the bookstore, or at the yogurt shop. Describe a brief interaction you had with someone in line with you, or an exchange between a mother and child. These take a little practice. But anecdotes are one of the most powerful writing techniques you can learn. And they are solid gold when it comes to writing your college admissions essay!

July 13, 2013

#YOLO and The 2013-14 Essay Supplements

Students must write one core college admissions essay if they are applying to a college or colleges that use The Common Application. But most schools also require additional essays, called supplements. The supp prompts for this year are starting to trickle out, and the trend so far is toward questions that are quirky and try to get students to think out of the box.

Even if these prompts seem lighter in nature, these are just as important as your core essay. Your supplemental essays might have a more offbeat or creative style or topic, but remember that many of your points should still be thoughtful and serious.

Tufts University is getting some attention for one of their new supplements. Among a handful of prompts students can choose from, one asks them to write about YOLO–or the idea that You Only Live Once. Both Gawker and the Huffington Post just wrote columns about Tuft’s unusual supplement prompts, which also include Quakers, nerds and the Red Sox.

YOLO is an age-old concept that dates back to the Roman idea of Carpe diem, or Seize the Day. Recently, a hip hop band named Drake popularized it with “The Motto” song, and #YOLO was a popular hashtag for a while.

The bottom line with this YOLO prompt is: When do you “go for” what you want, and when do you wait? Even though this question has a fun-loving feel, it is asking a relatively heavy question about your values, priorities and goals. Like most good essay prompts, it’s trying to get you to write about how you feel and think, and what you care about and why.

If you choose to respond to this provocative question–and other similar college essay supplements–here are a couple tips:

1. You will need to define YOLO in your own words, but make sure you don’t spend your entire essay (or even the majority of it) simply defining what it means. This essays demands you describe what it mean TO YOU!

2. The idea that You Only Live Once implies that if something means a lot to you, that you should go for it and not wait–at least not wait too long. Another way to think about it is to ask yourself: If you happened to die tomorrow, is there anything you would regret not having done? How do you decide what to “go for” in your life?

3. This essay prompt is basically asking you to ponder what you value and to weigh your goals–both in the near and distant future. It also is trying to get you to share how you make decisions when deciding how to pursue happiness in your life.

4. If you wanted to write a narrative style essay, I would suggest that you think of an example of a difficult decision that you had to make–and then go into how you figured it out. In your introduction, describe what you wanted in the form of an anecdote–which relates a moment in time. You could talk about how you walked into the tattoo parlor with your friend, and how you looked at the images you were thinking of getting, and how you thought of the pros and cons of this difficult decision. Or how you stood at the edge of a cliff, locked in a bungie-jump harness and debated whether to take the plunge. The idea is that you capture the reader by putting them at the most intense moment, and then go back and walk them through the steps you took to get there and make the decision to “go for it” or not–and include your logic and motivation.

5. The key to writing a strong YOLO essay for Tufts University (and ALL essays) is to give it focus. Don’t just talk about how you go for things in general in life, but pick one strong example of “a time” when you made one of these decisions, and then reflect upon that. The readers want to know how you make these decisions, not just a recounting of all the times you have made them.

Here’s the complete YOLO prompt:

The ancient Romans started it when they coined the phrase “Carpe diem.” Jonathan Larson proclaimed “No day but today!” and most recently, Drake explained You Only Live Once (YOLO). Have you ever seized the day? Lived like there was no tomorrow? Or perhaps you plan to shout YOLO while jumping into something in the future. What does #YOLO mean to you?

If you need more help writing a narrative college application essay, check out my new short guide, Escape Essay Hell!

June 26, 2013

Open Up: How to Connect with Emotion and Pathos

One of the best ways to connect with your reader in your college application essay is through emotion. In my new book, Escape Essay Hell!, I share writing techniques and devices you can use to bring pathos to your essay, and forge a bond with your reader. With these suggestions, I’m assuming you already have an introduction–probably an anecdote or mini-story–for your narrative essay, and have moved on to explain what it meant to you.

If you have an essay that starts by using an example of a mini-story, or relating “a time” something happened or you experienced, you must then interpret that story for the reader. While analyzing, explaining and reflecting on what you learned, these suggestions might help you make it more heartfelt, earnest and meaningful.

Here’s an excerpt from Chapter Six of Escape Essay Hell!: A Step-By-Step Guide to Writing Standout College Application Essays:

Open Up About Yourself

When you reveal your inner thoughts and feelings, this helps the reader empathize with you—and makes you feel real and human. Showing vulnerability and authenticity takes a lot of courage. For college essays, that’s good stuff—since it sets you apart from the crowd, forges a deeper connection with the reader and shows the maturity to be introspective and open about yourself.

Show Some Emotion

Once you told your anecdote, and then put it in context with some background (It all started…), you can pick up the story line to show us what happened next. If you started by describing a problem, now is the time to let us know how it all made you feel.

This is how we relate to your pain and understand why we should care about you and your problem. You don’t need to overdo this part; just a quick sentence or two and we will get the idea. Think back to how you were feeling at the lowest point.

In the sample anecdote about the student thrown into a busy restaurant kitchen, he might have said, “I knew I was over my head.” Or “I started feeling dizzy and almost bolted out the door.”

Other ways to let the reader in on your emotional reaction to the problem: “I thought my world was over.” “I thought my parents would kill me.” “I felt like pulling the covers over my head and staying in bed for the rest of my life.” “I felt trapped, as though I had no where to turn.” “I never thought I would figure it out.”

Include Dialogue

If you didn’t include any dialogue—quoting yourself or someone else—in your anecdote, you might consider dropping in a line or two when you background your story. You can use it to add drama to your story, such as a snippet from a key player in the story, or even quote yourself.

Describing your inner dialogue or thoughts, or even those of others in the story, is one of the best ways to give your essay that “narrative” style and tone. Usually you only need a few words, or a short line or two. Dialogue makes the essay read more like a novel or short story (fiction!), even though it’s true.

If it was something you thought, just let the reader know that. Example: “You are never going to reach the top of that mountain,” I thought to myself while looking up the steep cliff. Example: “Why do I always chicken out at the last minute?” I asked myself.

HOT TIP: Another trick to writing dialogue is to try to compress it. Once you write a couple sentences, or a quick exchange between yourself and someone else, try cutting it down. Usually, you can get the point across with fewer words than you think, and they end up snappier sounding, too.

If you are using dialogue–say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.

John Steinbeck

END OF ESCAPE ESSAY HELL! EXCERPT

If you would like more help writing your college application essay, consider buying Escape Essay Hell!, which helps you find a unique topic, and then steps you through the narrative writing process using storytelling writing techniques.

June 24, 2013

Go Green with Your College Application Essays: Recycle!

If you are applying to multiple colleges this fall, you will need to write multiple essays for the different applications. The Common Application helps you consolidate many of your applications and only requires one main essay. But if you are applying to public universities and private schools that don’t use the Common App., you will need to write additional core essays.

Also, the Common App. is not requiring a supplemental essay this year, so chances are individual Common App. schools will be requiring more supplemental essays.

So how do you find topics for so many essays? One approach is to get organized and recycle some of your best ideas, topics and even essays. It’s completely acceptable to use the same essay for various applications, as long as the essay answers the prompt. (You can’t get in trouble for copying your own work.) Of course, you don’t want to flaunt that you are recycling some of your essays for different schools.

In previous years, students who were applying to the University of California schools and colleges on The Common Application often used one of their two essays for the UC application for the main Common Application essay. The Common Application used to have one of its prompts as “Topic of Choice,” so it was easy to use one of the UC essays for that prompt.

Sorry to say, but that’s no longer possible. The Common App. removed the “Topic of Choice” option this year, and came up with five new prompts. However, there’s still a strong chance that your main Common App essay could work for one of the two UC prompts (and prompts for other applications). You might need to change your essays a little to make sure they clearly address the prompts, but several prompts overlap. Here are a couple strategies for recycling essays among the UC and Common App prompts:

A. If you answered Prompt 1 of the Common App, you most likely could use that to answer Prompt 2 of the UC application. Both prompts essentially are asking you to write what’s called a Personal Statement, which is a narrative style essay that uses a story or example to show the reader fundamental qualities about yourself. (If you answer any of the other four Common App. prompts using a story about a “personal quality, talent, accomplishment or experience,” check to see if it might work for UC Prompt 2 as well.)

Here’s the Common App Prompt 1: Some students have a background or story that is so central to their identity that they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.

Here’s UC Prompt 2: Tell us about a personal quality, talent, accomplishment, contribution or experience that is important to you. What about this quality or accomplishment makes you proud and how does it relate to the person you are?

B. If you answered Prompt 4 for the Common Application, which asks about a place where you are “perfectly content,” you probably could use that to answer Prompt 1 of the UC application, which asks you to tell about your world. Both prompts are trying to get you to relate a literal or figurative place that has special meaning to you, and most likely shaped who you are.

If you decide to recycle essays, it’s imperative that you read the prompts closely and make sure the essay answers the questions. If it doesn’t, make some changes so that it does. You should be able to use this approach in writing many of your supplemental essays, since many will ask for similar topics–such as writing about your extracurricular activities or why you chose a certain school.

Don’t Get Burned!

You must be extra vigilant, however, about re-using your own essays. One of my students from a couple years ago got burned when he accidentally left in the name of one college in an essay that he sent to another one saying why he selected that school. You can imagine how much damage that could do. It’s like telling your boyfriend or girlfriend how much you like them but accidentally call them the wrong name. Ouch!!

Recycling essays is a way to be efficient in your college applications, but you need to make sure each individual essay matches up with each individual prompt. You can’t be too careful with this!

CBS Digs Essay Hell’s Topic Tips!

College Application Essays

Tips for Finding Topics That CBS Finds Worth Repeating

A couple days ago, Lynn O’Shaughnessy, a journalist who covers college admissions issues for CBS, featured this blog in her column for MoneyWatch. How cool is that? She shared one of my previous posts that try to help guide students toward finding college application essay topics that don’t fall into the common traps, such as being cliche, too controversial or just plain dull.

These topic “no-nos” do not mean it’s impossible to write about topics that have been written before or are sensational in nature, but it’s a good idea to understand that they can be more challenging to pull off and not backfire on you. Like anything, it’s not what you write about, but what you have to say about it that matters. Some topics are simply more loaded than others.

Here’s the article from Lynn’s MoneyWatch column for CBS:

By LYNN O’SHAUGHNESSY | MONEYWATCH | June 21, 2013, 8:12 AM

10 topics to avoid in a college admission essay

(MoneyWatch) For students who are applying for college, one of the scariest parts of the admission process is writing the dreaded essay.

A common mistake that students make when tackling their college essays is to pick the wrong topics. It’s a huge turn off, for instance, when applicants write about their sports exploits or their pets. I asked Janine Robinson, who is the creator of a wonderful website called Essay Hell and the author of an excellent ebook entitled “Escape Essay Hell,” to identify those essay topics that teenagers should absolutely avoid.

Here are Robinson’s college essay no-no’s:

1. Listing accomplishments. You might be the most amazing person on the planet, but nobody wants a recitation of the wonderful things you’ve done, the people you’ve encountered and the places you’ve visited.

2. Sports. Do you know how many millions of teens have written about scoring the winning goal, basket or run? You definitely don’t want to write about your winning team. And nobody wants to read about your losing team, either.

3. Sharing how lucky you are. If you are one of the lucky teenagers who has grown up in an affluent household, with all the perks that goes with it, no need to share that with college admission officials. “The last thing anyone wants to read about is your ski trip to Aspen or your hot oil massage at a fancy resort,” Robinson observed.

4. Writing an “un-essay.” Many students, particularly some of the brightest ones, have a negative reaction to the strictures of the admission essay. In response, Robinson says, “They want to write in stream-of-consciousness or be sarcastic, and I totally understand this reaction. However, you must remember your goal with these essays — to get accepted! Save the radical expression for after you get into college.”

5. Inflammatory topics. It’s unwise to write about politics or religion, two of the most polarizing topics. Avoid any topics that make people angry.

6. Illegal activity. Do not write about drug use, drinking and driving, arrests or jail time. Also leave your sexual activities out of the frame. Even if you have abandoned your reckless ways, don’t bring it up.

7. Do-good experiences. Schools do not want to hear about your church or school trip to another country or region to help the disadvantaged. You may be able to write about a trip like this only if you focus on a specific experience within the broader trip.

8. The most important thing or person in my life. This topic is too broad and too loaded, whether you want to write about God, your mom or best friend. These essays are usually painfully boring.

9. Death, divorce, tragedies. The problem with these topics is not that they are depressing, but that such powerful topics can be challenging to write about. Absolutely no pet stories — admission officers hate them.

10. Humor. A story within a college essay can be amusing, but don’t try to make the entire essay funny.

Lynn O’Shaughnessy is a best-selling author, consultant and speaker on issues that parents with college-bound teenagers face. She explains how families can make college more affordable through her website TheCollegeSolution.com, her financial workbook, Shrinking the Cost of College and the new second edition of her Amazon best-selling book, The College Solution: A Guide for Everyone Looking for the Right School at the Right Price.

MoneyWatch columnist Lynn O’Shaughnessy

OTHER HELPFUL LINKS FROM LYNN:

5 tips for writing a winning college essay

5 myths about getting in and paying for college

10 great opening lines from Stanford admission essays

June 20, 2013

Become a Storyteller in Under Five Minutes

Writer Tommy Tomlinson via his Twitter profile

College Application Essays

A Mini-Lesson from a Storytelling Pro

I found this brilliant little example of how to understand what makes up a good story today in a column written by the talented sportswriter and journalist named Tommy Tomlinson. If you are writing your college application essay, and want to use the narrative style to tell a “slice of life” story or use an anecdote, this mini-lesson can help you a lot. In his column, Tomlinson used a movie as an example of his story, but his storytelling lesson works perfectly for narrative essays as well. Take five minutes–or less–and you will be able to find and tell your own stories. Tomlinson wrote:

“…here’s where I tell you everything you need to know about storytelling in five minutes.

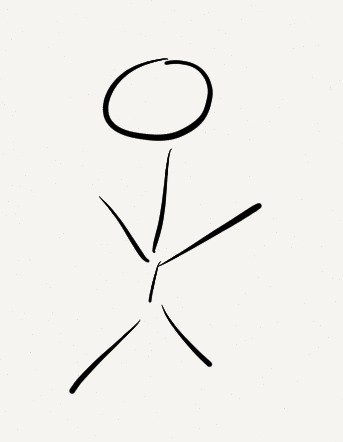

First, I’m gonna draw three objects.

This is a sympathetic character. It’s probably someone you like, but at the very least it’s someone you’re emotionally invested in. You care what happens to this person. (In your college application essays, this person is almost always you–unless you are writing your essay about someone else.)

This is a hurdle. It’s an obstacle of some kind — could be a bad guy, could be a physical challenge, could be some sort of internal emotional demon. (In my Essay Hell blog, I call these “problems.” Same thing.)

And this is the pot of gold — some kind of goal, some kind of reward, physical or emotional or whatever. (It can be as simple as dealing with your problem.)

A story is the journey of this character you care about (yourself), confronting and dealing with this obstacle, to reach this pot of gold.

In addition to these three pictures, you need to answer two questions:

1. What’s the story about?

2. What’s it REALLY about?

Here’s what I mean. What the story’s about is literally what happens in the narrative — who this character is, what goal he or she is trying to reach, what obstacle is in the way. The unique set of facts.

What the story’s REALLY about is a way of saying, what’s the point? What’s the universal meaning that someone should draw from this story? What’s the lesson? (What did you learn in the process of dealing with your problem?)

Think about the first Rocky movie. What’s it about? It’s about a no-name boxer in Philly (sympathetic character) who gets a chance to fight the champ (obstacle) and goes the distance (pot of gold).

He doesn’t win the fight — they saved that for Rocky II. The goal isn’t always the ultimate prize. Sometimes the goal is completing the journey. Proving you can go the distance is a worthy goal in itself.

But what’s the movie REALLY about? In a larger sense, the obstacle is not Apollo Creed. The obstacle is Rocky’s own self-doubt. The goal is making something of himself, not just out of pride but so he can prove himself to Paulie and feel worthy of Adrian’s love.

Why is that second layer of meaning important? Because not everybody is a professional boxer. But all of us have doubted ourselves and had other people doubt us. All of us have had the universal feeling of knowing that going the distance is a victory in itself.

That’s what makes stories matter: when you read or watch or hear a story about a total stranger, in a completely different world, and you recognize that story as your own.

Stories connect us as human beings. In fact, they’re part of what MAKES us human beings.”

Hope this helped you start to think about your own stories. If you want a fast and simple guide to finding and telling your own “slice of life” story for your college application essay, consider my book, Escape Essay Hell!.

June 18, 2013

Burned in Essay Hell

Image by Jim Cooke Via Gawker

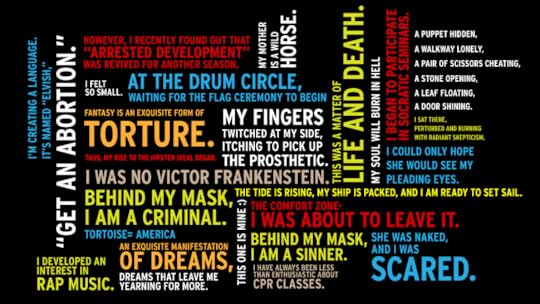

I don’t know how I missed this. In April, a batch of nearly 70 college application essays written by the incoming class of 2017 at Columbia University were made public. It was quite the scandal. Many of the students who shared their essays among their peers, not expecting they would be shared with the world, felt they were being mocked and ridiculed. Some bloggers did have a grand time poking fun of their topics and language.

The exposed Google folder is no longer available, but you can still read various blog posts that quote from some of the essays. I actually liked many of the topics and snippets of writing (in the Wordle image above). It showed the vast range of subjects you can write about and various approaches. To me, they can help spark ideas for your own essays, and see how you are not alone in your struggle to dig deep into your self and recent past for meaningful stories to share with strangers who will decide your future.

Here’s what J.K. Trotter wrote about the uproar on The Atlantic Wire:

As embarrassing as these people might feel, none of the essays were that bad, and they all worked. Judging from the ones I quickly read, most were very standard college application essays. There were a few pearls, too. One essay (which, like the others, disappeared) adeptly discussed queer activism in Lebanon. The more eyeroll-worthy ones, like the “hipsterdom” essay highlighted by IvyGate, seemed all the more honest for being so ridiculous and un-self-aware.

Here’s what Leah Beckmann wrote about the essays on Gawker. She had some fun plucking out various lines and suggesting you could have a killer essay if you just strung them together (below in blue font). Haha. She also copied in full two of the essays she liked the best. What I like is how you see some of the language, imagination and ideas they used. I’m impressed. Really. See what you think:

Not everyone can get into an Ivy league, but wouldn’t it be great if everyone could? We have culled several of the best lines from all 70 essays to create The. ULTIMATE. College. Essay. If you simply follow this format and copy and paste your favorite lines, you are 100% guaranteed to get into Columbia next year. For everyone who wishes “they were taught to love by a city of dancers,” here’s how it’s done:

Hook Em: It’s all about that attention-grabbing first line. And adverbs.

“’Get an abortion.’”

“All week as I looked at the Drum Circle, waiting for the Flag Ceremony to begin.”

“The comfort zone— I was about to leave it.”

“This was a matter of life and death.”

“This one is mine

”

”“My fingers twitched at my side, itching to pick up the prosthetic.”

“She was naked, and I was scared.”

What makes you YOU:

How do you see yourself? Show us how the world should see you.

“Who else’s identity can really be constructed by the calculus of fragmented memories? Not mine!”

“’You’re such a hipster.’ It’s a phrase heard everyday in school hallways across America, and its usage often operates as a conundrum that obscures teenagers’ perceptions of themselves and who they want to be.”

“A puppet hidden, a walkway lonely, a pair of scissors cheating, a stone opening, a leaf floating, a door shining.”

“I was no Victor Frankenstein.”

“I love experimenting new things [sic], exploring new places, and assisting those in need.”

“I have always been less than enthusiastic about CPR classes.”

“I am an individual free to create my own path and blaze a trail.”

“Despite the years that had passed, the intimacy of the memories flooded me, bringing with them a mix of emotions from anxiety to panic. Through blogging and subsequent interactions, I came to embrace my flawed nature, and I inspired others to do the same.”

“Behind my mask, I am a criminal. Behind my mask, I am a sinner. My soul will burn in hell, as the Bible—and my father—says. Behind this mask is who I really am.”

Set the Scene: Remember, god is in the details. What did your cheeks do? They burned. What is your mother? A wild horse. How is your skepticism? Radiant.

“The setting uproots itself. I muse on a field trip bus and write in an anonymous notebook. I’m creating a language. It’s named ‘Elvish,’ and it’s based on Latin: the ephemeral warrior with the Roman lover.”

“In the temperate winter of my tenth grade year, I developed an interest in rap music.”

“The summer air was sweet and caring as we sat there, drank some rootbeer and pondered the cosmos.”

“I sat there, perturbed and burning with radiant skepticism.”

“Time skips to a blues rhythm.”

“Here, Dali and Chagall are gods. Frusciante’s music fills the air as I walk down the promenade. Actors are playing out scenes from my life.”

“I could only hope she would see my pleading eyes.”

“My cheeks burned.”

“My heart pounds violently against my chest, pushing against the smooth blue fabric of my dress. I can practically see the silverware quivering, shaking, and as I realize that the adrenaline rush I am feeling is causing my hands to tremble, too, I feel someone seize my arm. Vamos a bailar! Let’s dance!”

“I feel tingly as my prom date and I stand up together and move to the center of the room. But this time, they aren’t shivers of fear.”

“I stand engulfed in curtained darkness. Around me, shadowy figures shift anxiously, like caged animals searching for an escape.”

“The haggard piece of cloth, worn at the edges but still strong at its core, looked at me desperately and clung to me determinedly.”

“She [my mother] is a wild horse, as erratic as she is gregarious.”

“An exquisite manifestation of dreams, dreams that leave me yearning for more.”

“Not because the sun blazed torridly on my brow and the sultry air hung on my neck like a noose, but disoriented because of the sight before my eyes— stables.”

“The summer air was sweet and caring as we sat there, drank some rootbeer and pondered the cosmos. And so we talked. We talked about women, and how awful they are, and how fantastic they are, and how awful they are. Out of nowhere, I began to cry and in the most gentle and angelic voice I heard Alex say something I found quite alien: ‘crying is okay, buddy.’ So I cried like a girl and I cried for everything I was losing.”

What Did You Do to Impress: You are a snowflake. You are Gaia. You are all that is good. Don’t be shy when it comes to describing your goals, your achievements, your Beanie Babies.

“Thus, my rise to the hipster ideal began. Throughout my middle school years, this natural instinct of mine manifested itself in many different ways: jeans tucked into knee-high socks, anything from punk to Harlem renaissance jazz bellowing from my headphones, Palahniuk novels peeking out of my backpack.”

“I began to participate in Socratic seminars.”

“But as time went on and the songs filed under the ‘Rap’ genre on my iTunes grew in number, I pinpointed exactly where my general discomfort had started: Rap, as a genre and as an attitude, has little-to-no place for women.”

“When I told Sally that over the summer I was going to Africa to help teach children English, she was horrified, fearing the worst.”

“In the summer of my junior year I stunned my family by insisting on going, instead of our staples of France, Italy and Switzerland, to St. Petersburg, where most of the Russian Royalty had lived.”

“Almost a month had passed and we only had a handful of Beanie Babies to show for all the work I put into this project. And yet, despite all my efforts, only four members responded to my pleas for Beanie Baby donations.”

“As I glanced around, tightly clutching my brand-spanking-new lacrosse stick, an awful epiphany struck me: I had enrolled in an all-boys lacrosse camp.”

“Ironically, I tried hard to use this garment to broadcast my individuality; I went through phases wearing a skullcap bedecked in everything from Pokemon characters to the cast ofSeinfeld.”

What You Learned: Your journey is over. What have you gleaned?

“Such is the problem with my infatuation with ‘Arrested Development,’ which, despite critical acclaim and a loyal fanbase (case in point: me), was cancelled after three seasons. So ‘Arrested Development’ is the epitome of all things—good, bad, or ironic—coming to inevitable conclusions. However, I recently found out that ‘Arrested Development’ was revived for another season. Some things aren’t over yet.”

“After qualifying for and going to Nationals, I realize that getting there is 90% want and 10% skill. I love knowing that if I try the hardest I will win.”

“The journey of Taekwondo is analogous to the journey of life.”

“Tortoise= AmericaHare= BanksRegulators= RegulatorsTape-makers= Rating agenciesSub-ground= Sub-prime loansBleachers= Housing marketPrize= BailoutIntricate system of tunnels= Derivative markets”

Conclusion: End it. And end it HUGE.

“I wake up every morning to be nicer, faster, stronger, smarter, and better. I wake up every morning to win.”

“The revelations and inspirations I acquired from my internship have only just begun snowballing.”

“One who seeks to identify himself and be identified by others as a ‘hipster’ undoubtably strives to conform to the ‘hipster’ construct; he tries to fit himself inside an inflexible ‘hipster’ box.”

“After all, what am I but the things I’ve done?”

“The tide is rising, my ship is packed, and I am ready to set sail.”

“Moving forward, I cannot wait to meet new friends, hear about their families, and discuss everything from our latest travels.”

“However, I recently found out that “Arrested Development” was revived for another season. Some things aren’t over yet.”

Betsy Morias, a Columbia alumnist who writes for The New Yorker, tweeted this piece of wisdom at the time: “In truth, the humiliation should be shared among all of us who have ever written a Columbia admissions essay.”

Or any college application essay. With these essays, we are asked to put ourselves out there, share our thoughts and opinions, get deep. And we all do our best–because they matter. Once they are done, submitted and we are into our dream school, most of us hope we never have to think about them again. And if for some reason they surface again in our future, we hope to be mature enough to enjoy a laugh on ourselves.

June 17, 2013

No Tuxedo Talk! How to Find Your College App. Essay Voice

College Application Essays

Write Like You Talk

The voice and tone of narrative essays usually is “looser” or more “casual” than the typical academic essay. To do that, however, you often have to break the rules. Bend them gently and stay consistent. But if it sounds right, go for it!

The best tip for striking a more familiar tone with your college application essay: Write like you talk!

Harry Bauld, who wrote what I think is the best book on how to write college application essays–On Writing the College Application Essay–advises students to stick with an informal voice. He likens this voice to “a sweater, comfortable shoes. The voice is direct and unadorned.” Stay away, he says, from language that is too formal, which he dubs, “tuxedo talk.”

This stiff type of writing is used by people who want to sound smart and important; most popular among scholars (including English teachers!), lawyers and other professionals who want to sound like they know their stuff even when they don’t. It’s a dead giveaway that you are trying to impress–something you don’t want to reveal in these essays, even if that’s one of your goals.

Bauld said: “Work toward the informal. It is the most flexible voice, one that can be serious or light. On top of that bass line, you can play variations–just as you do with rhythm.”

When you write informally, you often need to break some of the rules of formal English. Here are some that are okay to break, but don’t overdo it!

Use phrases or sentence fragments. Do this mainly for emphasis. Example: “I was shocked. Stunned. I couldn’t even talk. Not a word.”

End a sentence with a preposition. Again, stick with what would sound normal in conversation. “What do you want to talk about.” Instead of, “About what do you want to talk?”

Start a sentence with “And” or “But.” Again, use this for emphasis. Don’t over do it! “He ate the hamburger. And then he devoured three more.”

Throw in onomatopoeia. Remember those words that sound like what they are? Bang. Whack. Whoosh. Zip. Boom.

Use dialect or slang. Only use these if they are true to the speaker you are quoting. If you are quoting a surfer, it sounds appropriate if they say, “The waves were so awesome!” If they are from the Deep South, they can say, “Ya’ll.”

Contractions are fine. Again, trust whether it sounds OK within the larger context of your essay. “I didn’t want to go there.” Instead of, “I did not want to go there.”

Split those infinitives. It’s just not a big deal. “To boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Remember, these are only rules to break if they help create your voice, tone or make a point. Above all, writing casually does not mean you forget about grammar, spelling, punctuation, and all the ways you make your writing clean and accurate. You can only bend rules when you know the rules and stick to the important ones. (Otherwise, you just sound like a dumby.)

Also, after you write your rough draft, go back and read it again. Ask yourself: Would I really say that or am I trying to sound smart? If it sounds formal and pretentious at all, try to say it in a more direct and casual way.

For help finding a unique topic and crafting a narrative essay, check out my short, handy new book, Escape Essay Hell!: A Step-By-Step Guide to Writing Standout College Application Essays.

June 15, 2013

What Do Admissions Officers Really Really Want?

College Application Essays

Hot Writing Tips from The Other Side!

If you haven’t noticed, I have a lot of opinions about what makes a great college application essay. But who am I? I’ve never been an admissions officer, so how do I know what they like and want? I thought it was time to ask a real live, breathing admissions officer who reads thousands of these essays–and uses them to decide who’s in or who’s out.

To find a great source, I went back to when I started tutoring students on these essays, and my very first client–my daughter. When Cassidy was an incoming high school senior during the summer of 2008, I helped with her essays. We had read the guide on finding terrific small liberal arts schools that are off the radar, called 40 Colleges That Change Lives, and she ended up going to one from that book, called Hendrix College in Arkansas.

Cassidy just graduated this spring, and her small college was every bit as wonderful both academically and socially as the book described (Five years in a row Hendrix has been on the “Most Up and Coming Schools” list for U.S. News & World Report). I decided to ask their admissions officers how they select students using these essays.

Insider Tips From the Director of Admissions at Hendrix College

Their gracious Director of Admissions, Fred Baker, who reads every Hendrix essay–about 2000 a year–told me some things I knew, some things I was happy to hear, and a few things I wish I had known earlier. (Hendrix uses The Common Application) Fred said:

1. One of the best ways to write an interesting essay is to tell a story. One of Fred’s most memorable involved a student who wrote about a service trip to Houston. But the student didn’t just describe the entire trip. Instead, he focused on one moment while making brown bag lunches for a group of underprivileged residents. He described glancing over at another volunteer, and then watching him reach down, take off his own shoes and hand them to one of the patrons. Then the student went onto explain the impact that humble, generous moment had on him. This example supports the idea of using narrative-style essays. There’s a reason Fred never forgot that essay.

2. These essays matter more than you might think. “The essay that seems small potatoes in August can potentially have big bearing later,” Fred said. Not only do the admissions officers use them to decide who gets in or not to Hendrix, but the English professors read them to help determine placement in various writing courses. They also are read by the scholarship committee to determine who gets merit scholarship money. That can be thousands of dollars!

3. He remembers kids from their essays, and often tells them this when they finally meet in person. This is huge! It’s crucial that these essays put a face on a student’s application. Fred said it was impressive how the student often matched the spirit of their essay. “The ones that are my favorites are the ones that you can really get a sense of who the writer is. The essay can be a way for that application to come to life…You get a little taste of the students’ personality, maybe they are spunky or passionate or idealisitic; it’s any number of things, where a little bit of their essence comes through. Those are the most memorable.”

4. It’s important to catch his attention right away in the essay. “Like anything, a newspaper article, novel, whatever, if they don’t grab you pretty early on, you sort of lost that opening round. Good writing pops, you think, ‘Wow this kid’s a gifted writer,’ with a great sense of humor, or wonderfully serious, and not hammed up.”

5. Unique topics are greatly appreciated. “We get a kabillion ‘I tore my ACL (knee muscle)”, but to that student it was significant, the hurt, sitting out while watching teammates, the grueling rehab. But many essays just aren’t poignant.” Other over-used topics were mission trips and Harry Potter.

Final tip from Fred: ”Be you. You don’t have to focus on some massive global issue or why college ‘blank’ and I are a good fit. Tell a detailed story that is you in a nutshell or an example of what you are passionate about.”

A big thanks to Fred, and Hendrix College, for being so generous with his time and earnest advice

to help students have their best chance at writing great college application essays!

Now we know what admissions officers like and want, how do you actually write one of these memorable essays? If you want a step-by-step guide on how to find unique topics and craft essays using a narrative writing style, check out my new ebook, Escape Essay Hell!.