Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 34

October 31, 2016

20 free horror games you should play on Halloween

There is no short supply of free horror games. Hell, the rise of reaction videos in recent years has actually brought a surge of them. People have raced to to make a videogame that’ll scare the pants off their favorite YouTubers so they can watch. But that’s also a problem: a lot of these small, free horror games go for the cheapest thrill to achieve their goal. Yes, the jump scare.

It is with that in mind that the 20 free horror games below have been selected. We prefer creep outs, an intense sense of dread, the kind of horror that lurks as you tuck yourself into bed. We want a scare that’ll last longer than two seconds. That said, there are a couple of jump scares even among these picks—it’s hard to avoid completely—but they are at least tasteful and used sparingly.

Right then, it’s Halloween, you’re ready to be scared, and we have 20 horror games that you can play right now without spending a penny. Turn off the lights, make sure the house is silent, and then begin …

The Uncle Who Works For Nintendo (Michael Lutz)

Michael Lutz’s The Uncle Who Works for Nintendo mines a rich vein of folkloric horror. It feels like something you’d hear around a campfire; that urban legend quality is built into its DNA. Released just as Gamergate began to froth and wail its abyssal song, Lutz’s game finds terror in an unreal schism carved into the safety of its characters’ domestic lives; one heralded by good old Nintendo. Dig the careful use of sound to amplify spooks.

Compositions (Nuprahtor)

Nuprahtor might be the closest to an artist that horror games have got. His early series of compositions are singular and sublime. Each of them seems to have been designed around a perfect moment of terror, as if he started with a painting and then worked out the steps leading up to its arrangement, with the player at the center. Unexplained, subtle, and short, each of the compositions manage to be haunting in their own unique ways. No one else has created horror games quite as pristine as this.

The House Abandon (No Code)

Designed by No Code, a studio led by Alien: Isolation (2014) UI artist Jon McKellan, The House Abandon is a text adventure played within a chunky old PC. The same feel for awful obsolete tech that characterized Alien: Isolation forms the backbone of this brief creep-out, which has fun fucking with you in clever ways. One tip: check the kitchen!

Cyberqueen (Porpentine)

Porpentine’s Cyberqueen is an unparalleled exercise in vomitous biopunk, the prize corpse flower in the decadent garden of Twine body horror. It’s got all the linguistic feats of strength that characterized her other text-based game Howling Dogs (2012), but marshaled in service of a scalpel-sharp, needle-focused homage to System Shock (1994), H.R. Giger, and the wonderful fragility of the flesh. You will die, repeatedly, thrall to a malevolent, sadistic artificial intelligence. One anonymous Tumblr user told Porpentine “so I played Cyberqueen and was sort of really aroused.” There is something distinctly mistress/servant about the tortures heaped upon your character, though fair warning: proper consent is not exactly part of the scenario.

Lakeview Cabin (Roope Tamminen)

Comedy is often paired with horror. But not in videogames. At least, not successfully. That’s what makes Lakeview Cabin (2013) remarkable. Ripping the slasher-horror model of Friday the 13th (1980) almost wholesale, it gives you some time to hang out at a picturesque lakeside, going swimming, running around naked, and hacking at tree trunks. It’s silly for the sake of it, refreshingly open in its playfulness. Then some ditch-faced shit lurks out of the lake and cuts out your insides. That’s when the game begins proper: on the second try, it’s time to lay some traps, or you could just enjoy the little time you have left before the horrors come.

PuniTy (Farhan Qureshi)

Look familiar? Yes, this is the Silent Hills teaser P.T. (2014) recreated by an eager fan, more or less. You walk up its corridor, around the corner, and past the bathroom of soon-to-come sickening horrors. But not everything is as you remember it from Hideo Kojima and Guillermo del Toro’s original. The creator of PuniTy has added some new surprises in with the expected ones. It’s up to you to happen across them. Get your hands at the ready to cover your eyes.

Imscared: A Pixelated Nightmare (Ivan Zanotti)

Before P.T. injected a desperate need for photorealistic domestic horror spaces into videogames, there was Imscared (2012). Unashamed of its gigantic pixels, it embraced them, using their muddiness as a way to create 3D spaces that, when cast in a dim light, seemed to move at the edges of your sight. The pixels are a big part of what makes the initial experience of the game work, as something haunts your periphery, but the game should also be commended for its after-party. When you’re finished with the game and close it down, you’ll quickly find out that it’s not quite finished with you.

1916 Der Unbekannte Krieg (DADIU Student Team)

If you were to find out what 1916 Der Unbekannte Krieg (2011) was about before playing it you would think it ridiculous and probably scuttle off. It’s for the best that you only know that it plays on the horrors of World War I, then. In fact, it takes place in the trenches, where the floor is a bog and a thick gas hangs around your knees. You probably have shellshock. Yeah, that would explain what happens. Put it this way, the instantaneous death of going ‘over the top’ will soon seem like salvation.

Hide (Andrew Shouldice)

Hide (2011) has the same framework as that one viral Slender Man game, but puts a bit more thought into it. A word to sum it up would be “exhausting.” In the chill of a snowy night, you search for five notes while something stalks you. It has you tapping to sprint, your character breathing heavily, hardly able to get far without needing to slow down and catch their breath. And so when the shit hits the fan you can only crouch in a corner and hide, praying that it hasn’t seen you.

One Late Night (Black Curtain Studio)

It takes a long time for One Late Night (2013) to literally throw a ghoul at you. And it’s all the better for it. Taking place in a surprisingly confident replication of an office, it’s patient with you, as if going “Does this scare you? No? OK, how about this?!” At first, it’s eerie enough being alone in the office. Then a message appears on your monitor saying “I see you …” And then starts the paranoia. Before long you’re reading notes left by co-workers who have been through the same shit. A chair is flung through the air. Something’s in the bathroom. More and more paranormal signs show up while you desperately try to convince yourself that it’s an office prank. Sorry, but it’s not.

Deep Sleep (Scriptwelder)

Taking place inside someone’s lucid dream, Deep Sleep (2012) is one of the creepiest point-and-click adventure games ever made. The words “Wake up” whispered through a phone are particularly chilling. But that’s only the start, as you venture further into this dark dreamscape, you’ll be chased through corridors by odd figures designed only to hurt you. But the direct terrors are secondary to the supreme concoction of the game’s eeriness, driven by a clever use of sound and a confidence in your own mind to project fear onto its pixels.

Yume Nikki (Kikiyama)

Yume Nikki came out of fucking nowhere in 2004. We still don’t really know who made this thing—next to nothing is known about designer Kikiyama. Yume Nikki exists in a void, a warped black crystal of broken dream spaces and surrealist logic that persists in confounding and startling the hell out of anyone who plays it. You can make shut-in protagonist Madotsuki try to leave her apartment, but she’ll just shake her head and refuse. But you can always go deeper into her dreams, digging through absurd ugly jumbles of RPGMaker level design and abrupt jump scares, meaningless goals and unusable objects, killable NPCs and indelible visions.

My Father’s Long Long Legs (Michael Lutz)

Situated somewhere between illustrator Emily Carroll and manga artist Junji Ito, Lutz’s second entry on this list is a horribly clear-eyed portrait of madness. The patriarch of your family has become obsessed with digging in the basement; what he’s digging for, and why, are answers you should uncover yourself. Again (or first; this comes before The Uncle Who Works for Nintendo) Lutz employs sound effects to eerie effect, and the game’s climax makes Emily Carroll-esque use of web-specific effects like scrolling and mouse movement. Maybe that sounds dry; I promise you it’s not.

Lisa The First (Austin Jorgensen)

Everything in Lisa The First (2012) is filthy. Puke and bile covers the walls. Trash is thrown about in disarray. Press Z at a toilet and Lisa will barf into it. This is filth horror at its most vile. At the heart of it is Lisa’s gross and abusive father. He reoccurs across the landscape of her mind as she descends into madness. Ropes and bile bound her as she tries to escape the room her father locks her into. But in the end it’s no use. Creator Austin Jorgensen uses a combo of textural sludge and disturbing music to manufacture the horror tone in Lisa The First, which is something he transfers to the 2014 sequel, Lisa The Painful.

Power Drill Massacre (Puppet Combo)

There are way too many free horror games that involve walking around a maze with a flashlight while some dick with a knife stalks you. Many of them are bad. Few are worth even a flake of your skin. But Power Drill Massacre is different. Well, not really, not exactly—it has a grindhouse aesthetic, that’s about it. But there’s something about the expressionless mask of its killer and the ferocity of his attacks that scares the living shit out of most who play it. Like, properly. Not the standard YouTube scream—it’s a game capable of a genuine and sudden fright. Knowing that it’s coming on subsequent playthroughs puts your heart in your throat. It’s a thrill that not many horror games are able to reach. And it’s one that shouldn’t exist within this tired horror game mold. Yet it does.

Knossu (Jonathan Whiting)

Buildings can be scary. Imagine if you walked out of a tunnel into an open plaza, and upon turning around, the tunnel you just emerged from had disappeared. Or, you walked along a lengthy, empty road for an hour, nothing but terraced houses at your side, but when turning around to look back at the corridor behind you there was a huge concrete wall at the tip of your nose. Where the fuck did that come from?! It’s this kind of architecture horror that Knossu (2015) thrives on. You will get lost in its labyrinth, not for its complexity, but for its many illusions.

Tonight You Die (Duende Games)

A brutalist horrorscape seen at night. That’s where Tonight You Die (2015) takes you. Do as you wish: stay perfectly still, explore its multi-storey car park, circle the urban glossary. It doesn’t really matter what you do. You will die anyway. Knowing that may take away the terror, but when it steadily comes for you, like a noise gnawing inside your head, you will probably find yourself jumping at nothing, cursing your limited vision. It’s coming …

Bad Dream: Series (Desert Fox)

Ever wandered around town at the dead hour of 2AM? There’s a disquieting silence that comes with it—like something beating noiselessly against your ears. The dilapidated, black-and-yellow empty towns of the Bad Dream series embody that entire experience. They seem to exist in a Silent Hill-like dimension where, years ago, a series of depraved pranksters set up traps for you to prod. And that’s one of the best aspects of the series: time and again, the games draw attention to your body presence in a format that typically forgoes it (the point-and-click adventure). The series uses the distance you put between yourself and the games as a chance to bring you right in and strike at horror. The fingers of your cursor will be suddenly snipped by a pair of scissors—proper “oh shit” moments.

SCP — Containment Breach (Undertow Games)

Yes, it does have a dirty-rag of a Teletubby chasing you around, but give it a break. The central blink mechanics of SCP — Containment Breach are actually put to great use. At one point you need to time your blinks so that a deadly statue that moves at high speed when not in your sight doesn’t get you. But later on in the game, this blink mechanic is inverted, as another deadly creature will kill you if you look at its face—that’s when you’ll want to shut your eyes and move around blindly. What’s principally horror stodge actually proves to be thoughtfully designed and lends itself to prolonged bouts of terror.

Her Pound of Flesh (Liz England)

Like Porpentine’s work and Tom McHenry’s gonzo Horse Master, Liz England’s Her Pound of Flesh is a heartfelt, disgusting piece of work. I don’t have the space here to try to dissect why Twine has attracted so many emotive body horror games: I can only suggest you play them all. Her Pound of Flesh is about heartache, in the end, but heartache filtered through a gloriously grotesque prose sensibility.

The post 20 free horror games you should play on Halloween appeared first on Kill Screen.

“Cuba’s first indie game” wants to be much more than that

Videogames haven’t been kind to Cuba. In 1996, A-10 Cuba! had players decimating Cuban military defenses from an aircraft; the following year saw GoldenEye 007 on the Nintendo 64 depict Cuba as a hostile jungle full of source-less bullets; it didn’t even let up in 2010, with the arrival of Call of Duty: Black Ops, which had players hunt down Fidel Castro during the Bay of Pigs Invasion and fail due to his deception.

This is no surprise given that a lot of videogames are made by the United States and its allies. Since the Cold War and the rise of Castro, relations between Cuba and the capitalist countries have been hairy—in reality and in videogames, Cuba has been associated with mistrust, aggression, and the Red Scare. This is slowly, steadily changing, helped along by Barack Obama restoring diplomatic relations with Cuba’s president Raúl Castro on July 20th, 2015; the ties severed since 1961 restored once again even if in limited form due to the trade embargo.

“The people are optimistic for the future”

Since then, Cuba’s economy has been able to breathe a littler easier, which has allowed for the growth of national trades and industries over the past year. One of those is Cuban videogames, which , but they are spreading to the point that there’s now a team who claim to be making “the first Cuban indie game.” It’s a 2D platformer called Savior about a bunch of characters who discover that they exist inside a videogame.

While the claim that Savior is the first independent game to come out of Cuba could be tested, it has not yet been disproven. So, for now, the team making Savior are using it to catch some attention. But Josuhe H. Pagliery, the game’s designer, would rather it wasn’t this way. “[I want to make] a game that is actually good, not just interesting because it’s the ‘first Cuban game’!” he told me. “I want Savior [to] be a great game, that also happens to be made in Cuba. That’s our dream anyway!”

Pagliery and his team’s ambition here is understandable—as with most artists, they want to be recognized for their talent more than their circumstances. But the Cuban identity of Savior might be worth holding onto beyond its claim to fame. I asked Pagliery if there was anything about his game that was specifically Cuban, that could have only been manufactured by a Cuban team, and it resonated.

“It’s funny, because when I started to conceptualize Savior, I had a lot of philosophical and artistic questions but nothing really related to the always colorful Cuban reality,” Pagliery said. “But at some point in the process of development I discovered that from one point of view, the game is almost a direct reflection of this very unique and weird moment that we Cubans are experienc[ing] in our country right now.”

“almost all games in Cuba are pirated copies”

He then quoted a line from his game’s description that he saw as particularly pertinent: “the Great God is no more and the world of Little God, for better or worse, is changing forever…” The Great God could be interpreted as the US and its constriction of Cuba over the past 50 years, which is now dissipating. The Little God is perhaps Cuba itself then, which had for so long been strangled, and now finds itself in a looser grip. “The people are optimistic for the future, but uncertain what that future will look like,” Pagliery wrote on the game’s Indiegogo page. It’s a line that could equally describe both the community in his game’s fiction and the Cuban population at large.

Pagliery notes that this moment in Cuban history is more than a reconnection with the US. The country is learning to connect to the rest of the world too. With the economy changing, the internet has begun to spread across Cuba proper, albeit it’s only available in certain Wi-Fi hotspots—it’s “very slow,” according to Pagliery, “one of the slowest in the world.” Its spread should hopefully lead to an interconnected network of people interested in making games around Cuba, but Pagliery reckons that’s still a ways off: “I assume there are others like myself working on their own videogame projects, but aside from the educational titles and low-quality games made by the Cuban government, I don’t see anything significant out there.”

Sharing ideas among like-minded others might be a distant dream in Cuba, then, but as international trade opens back up with the country, there might at least be a chance to find inspiration in new videogames. “Right now almost all games in Cuba are pirated copies, but for the majority of Cuban gamers, it’s simply impossible to play any of the most recent videogames,” Pagliery told me. The current way to get hold of videogames is through the “illegal but tolerated” Paquete Semanal, which is described as “an offline internet in the form of a weekly hard drive that customers pay to have delivered directly to their door.”

Pagliery has managed to play the Souls series recently but other Cubans don’t have the same privilege. And so, maybe, as new videogames start to enter the country through legal means, and with the greater spread and accessibility of the internet, more of the population will be encouraged to get into making their own games. Right now, Pagliery finds the present situation “surreal,” especially the fact that he is now in the US so he can run a crowdfunding project for the videogame he is making—you can’t currently host a crowdfunding campaign from Cuba. “Even this interview for almost unreal for me,” he said. “Many ordinary things that people in the rest of world take for granted for us are exceptional ones.”

The plan is to get Savior finished for 2018. It’ll be digitally distributed around the world and released for free in Cuba. You can support the game over on Indiegogo.

The post “Cuba’s first indie game” wants to be much more than that appeared first on Kill Screen.

A theatrical game about the difficult art of conversation

A Ghost in the Static doesn’t tell you anything. All you know is that you’re a figurine constructed out of some sort of wire and are left to explore a dark, mysterious room. Then you encounter another character in the room with you, and that’s when something unique happens.

Much of A Ghost in the Static focuses on narrative development through dialogue. What’s interesting about it is that you control both sides of the conversation—kinda like you do in Kentucky Route Zero. This allows for a number of different paths in each conversation. Some exchanges might be about the planet that’s visible within the dark room, while another conversation hinged on the same exchange could have the character talking about love.

they all ultimately lead to a mysterious ending

There are dialogue paths that make far more sense than others, and it’s easy to craft a completely incoherent conversation. For example, multiple interactions could easily begin with the word “hello” as a response to a question. It doesn’t seem to matter much whether or not these conversations make sense as they all ultimately lead to a mysterious ending. However, it is possible to unlock different dialogue options. As you talk to yourself, a transcript of that dialogue appears on screen, which is saved at the end of each interaction to help you avoid repetition.

A Ghost in the Static began as a university project, and it was created by Maggese, a pair of students interested in creating meaningful narrative experiences. They said of A Ghost in the Static: “Its aesthetics are inspired by contemporary architecture and stage design, the theme of the dialogues are inspired by Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris.”

True to its inspirations, the game’s characters have a certain architectural look to them, and the lighting in the dark room is indeed reminiscent of a theatrical stage. Knowing that Solaris also has influence helps to bring the game’s cyclical, conversational form into focus, given that the novel explores human memory and the trouble with humans communicating with non-human species.

Many games by Maggese are offered online as free downloads, and A Ghost in the Static is available through itch.io at a price of your choosing. A Ghost in the Static is also currently on Steam Greenlight in the interest of reaching a larger audience.

Learn more about Maggese here , and find a link to download A Ghost in the Static here .

The post A theatrical game about the difficult art of conversation appeared first on Kill Screen.

Horror comedy in videogames isn’t given enough credit

He recently passed away, but in his 90 years on earth Herschell Gordon Lewis claims that he had been approached on two occasions to direct a snuff film. The idea didn’t amuse him. During an interview with Alexandra West from Diabolique Magazine, he said such a thing wasn’t “worthy of a thought.”

“I regard that as too far back in organized society,” said Lewis in his genuinely golden voice, which narrates some of his films. He expressed that even seeing bodies on the evening news was tested his sensibilities. To Herschell Gordon Lewis, death did not appear entertaining. It would be an uncontroversial statement coming from anyone who isn’t better known as the “Godfather of Gore.”

straddling the comic and the tragic with gore

The Lewis filmography is made of especially mindless meanders through bloody murder. Blood Feast (1963), not Lewis’ first picture but considered the first “splatter film,” is an hour of a history buff murdering women and disemboweling them as part of an Egyptian ritual, leaving them in a blank stare in hollow rooms and slathered in red paint.

The Wizard of Gore (1970) is 95 minutes of Montag the Magnificent chewing the scenery and gutting victims, sawing them in half or drilling holes in their abdomen, fiddling in their guts in half-second handfuls like a prospector sifting for gold. The killings don’t merely happen out of maliciousness, but moreover because the film doesn’t seem to have any idea where else to go. An original ending involving a goat carcass was ditched due to an electrical fire that got them kicked out of the location. Instead it turns out the entire film was a dream.

Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964) is a very literal interpretation of “the south will rise again.” Again around 90 minutes long, wild hillbilly ghosts chase city kids while the city kids run around trying not to get gored. The apex of the film, if there is one, is that the southern ghosts are very intent on dropping a boulder on at least one of them.

I won’t pretend that Lewis made good films, but he made debauch, entertaining ones. They were important ones too, along with Jack Hill and Russ Meyer, crystallizing what it looked like to abandon good taste as the American film production code was losing its grip on Hollywood. Since that era, filmmakers, successfully and unsuccessfully, sincere and insincerely, have tried to replicate that moment. The careers of John Waters, Tobe Hooper, Rob Zombie, Peter Jackson, Eli Roth, Lloyd Kaufman, and even Quentin Tarantino wouldn’t have the magnetic north to their compass otherwise.

irony is the only difference between the comic and the tragic

Lewis’ films are the patient zero of horror comedies. More disturbed than scary. Funny despite a dearth of jokes. Horror comedies are a huge chunk of the cinema, and top lists of the genre include dozens of the type: Evil Dead (1981), Creepshow (1982), Shaun of the Dead (2004), An American Werewolf in London (1981), Fright Night (1986). The comic and the tragic seem hopelessly intertwined, and there’s nothing new about wondering if there’s even a line separating the two as much as a point when you stop screaming and start laughing.

It’s a dated analogy, but Umberto Eco illustrated the rift by saying that a Chinese cannibal is not funny, unless the cannibal is using chopsticks, in which case it is funny, unless you are Chinese. To modernize that definition to something a little more tasteful by comparison, I would nominate The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), where Southern degenerates deep fry their victims and serve pieces along the highway. Hooper would return to that theorem with The Funhouse (1981): teenagers being killed by a mutant isn’t funny, but it is ironic that it’s happening in a dark ride meant to give thrillseekers goosebumps.

For videogames, the tradition of straddling the comic and the tragic with gore is rooted just as it has been for film. Mortal Kombat scared parents witless in the early ‘90s, the “Fatalities” where spines are ripped out by throat were usually the focal point of such controversies. But the same finishing blows included getting a smooch from Kitana so nice the opponent exploded, or Liu Kang dropping an arcade cabinet on someone, and were quickly complimented by “Friendships” and “Babalities,” where players could opt to exchange gifts or turn each other into toddlers respectively.

It’s worth mentioning that the hearings overseen by Joseph Lieberman that led to the ESRB rating system were also fixated on Night Trap (1992), a game better remembered for its teen pop theme than any dismemberment.

gore has become more interesting than the shock value

But those are just the origins. How games play with gore has become more interesting than the shock value, and players and creators are subject to how flexible this hyperviolence can resonate. Similar blood effects from Dead Rising’s (2006) slapstick zombie adventure can be seen in Shadow of the Colossus (2005) in a deeper hue. In the latter case, the image creates a haunting sense of regret, even if the black substance sprays like your thumb is on the hose.

The rule of thumb seems to be that irony is the only difference between the comic and the tragic, but even that can be used to rubberband the audience. It’s harder to say where in the nauseating Hotline Miami series the massacre comes off as humorous, compared to other killing spree games like Postal (1997), but both the horror and hilarity of your actions seem to occupy the same memory. In fact, the sheer enjoyment of your destruction only adds to the horror, like all it takes to become the monster is a subversive presentation. I expect some similar thrills when the player-versus-player Friday the 13th game launches next year, and that chord appears to be getting a perhaps less effective workout in Suda51’s upcoming Let It Die.

Herschell Gordon Lewis had perilously few pretenses about his directorial work. While he never fully retired as a filmmaker, he spent the large interims in advertising, a field he supposedly earned respect in. He claims he used those skills to get his films into theaters, and the original trailers have him and surrogates directly address the audience. It’s hard not to smile that his official site, which is dedicated to writing copy, refers to him as “The Godfather of Direct Marketing and Gore.” He made movies to put butts in seats, and in doing so crafted a legacy, while also opening up a conundrum about entertainment. It’s easy to say when something horrific becomes funny, because by that point you’re drenched in it. The alternative—a horror that didn’t entertain—didn’t amuse Lewis, not one bit.

The post Horror comedy in videogames isn’t given enough credit appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 28, 2016

Gravity Rush 2 will have you fight huge, living cities

“Holy shit!”

That’s the correct reaction to finding out that Gravity Rush 2 will have city-sized enemies. In fact, they actually are cities—the screenshot above is of a Ghost City, which “eats entire buildings, reconstructing them as limbs as it fights.” That is the coolest shit.

This info comes from a bunch of new Gravity Rush 2 screenshots that PlayStation uploaded to its Facebook account yesterday. Among them, it’s revealed that Kat, the game’s gravity-defying heroine, will return to the city of the first game and have a bunch of new alternate costumes. But the biggest news is that friggin’ Ghost City. All hail the city that walks, literally, and eats up the edifices that surround its knees.

Look, I kinda love the Gravity Rush series on principle: these are games that emphasize and have a love for architecture. The first game’s city of Hekseville combined signatures and sensibilities from Tokyo and Paris, it being produced by a Japanese team led by Keiichiro Toyama, who was fascinated by French sci-fi comics from the ’70s as a kid. Among them is Moebius (real name: Jean Giraud) and his graphic novel The Long Tomorrow (1975), which depicted a gargantuan city with an immense verticality, busy with vehicles that flew around the chasms between the towering skyscrapers.

the city should feel more alive …

That sense of height can be felt throughout Gravity Rush (2012), as Kat is able to fly high into the sky and suddenly drop, freefalling past the strata of living spaces carved into the floating city. You can run along the vertical faces of buildings, fly far away to get a grander view of the whole city, or zoom right in to get accustomed with the anxiety of the population. The city and its various divisions were characters in their own right. Gravity Rush 2 is only expanding on that sense of scale and culture, this time taking more influence from South America, which should give certain areas more color and energy. In other words, the city should feel more alive …

To find out that the game is leaning further into this commitment to having a huge, living city by making some of its enemies actual living cities just feels right. On top of that, I’m enjoying the idea that Kat is also able to repurpose architecture to use it as a weapon too. “Using the Stasis Field while in Jupiter Style allows Kat to create a giant Debris Ball,” reads one of the new screenshots, showing Kat hoisting a ball of junk in the air, ready to fire off like a huge cannonball. Fighting a giant, walking city with concrete and rusted metal may not be very effective, but I will do it anyway.

Gravity Rush 2 is due out for PlayStation 4 on January 20th 2017.

The post Gravity Rush 2 will have you fight huge, living cities appeared first on Kill Screen.

Dark Train is a mystery made of paper worth unfolding

Paperash Studio has done everything creative you can do with paper, except put words on it. The studio’s textless adventure, Dark Train, is made entirely out of papercraft and code—a carefully folded world of bats and belfries, soccer fields and sleazy hotels. Its title flirts with the idea of being a long-lost piece of ’90s cinema directed by Alex Proyas (responsible for The Crow and Dark City), and to be fair, that’s not a bad analogy.

While the camera sticks like cement to the titular train, it is but a vessel for your viewpoint as it moves through the city; a city erected in black, a city with industry and families packed tight together, a city not unlike the sprawl of London. It is a place in permanent smog, where the architecture unites like a bed of nails, an oppressive state enforced by robotic animals. You play as one of them, a mechanical squid, chained to the train as it sits on its tracks, tasked with starting it up and maintaining its journey.

we’d break free from this moving prison

How you might go about completing that task has an answer you can only poke at with your pointy-tipped head. Dark Train‘s complete lack of tutorial or any kind of obvious guidance parallels its stern environments. An implicit get to work or fuck off attitude. Getting the train’s wheels rolling is but the first test in a series: do you have the patience and curiosity to figure everything out on your own? If not, the game will wear thin very quickly, and you will probably leave it behind. I was nearly part of that despondent population, as after I got the train moving I couldn’t find what else to do.

It was at this time that I was drawn to let the squid’s chain drag across the passing ground, sparks from the friction grazing her face, until the momentum suddenly, violently pulled her down, dragging her body helplessly across the concrete. I thought she’d die, I thought that’s how we’d break free from this moving prison—where we were trapped by my incompetence—but she’s a robot, and can take a beating. Escape isn’t so easy.

As that option didn’t work out I found the resolve to commit to learning the game’s subtle lexicon, and it’s worth the effort. It’s rare these days for a game to truly prove perplexing, for it to feel like videogames did to me as a toddler, when their visual cues and cultural references didn’t make any sense, like they were broadcast by an alien frequency that I had somehow tapped into. Dark Train puckers up tight when you arrive, but you can steadily grease its stiff gears, and over time you should find that you can work the dark engine with considerable ease.

While part of Dark Train is upholding this mastery over what Paperash delightfully refer to as an “unpredictable railroad tamagotchi,” this is only the bedrock of its appeal. In fact, as with any kind of resource management / babysitting, taking care of the train is about as dull as the game gets. What you’ll stick around for is the discovery of pocket worlds inside the train’s carriages. These are small universes framed by a metal container. You head inside and find whole forests, a church and graveyard, and most remarkable, a whole other city. Far from magic, these tiny dimensions seem totally possible in the world of Dark Train, a trick of the technology—it is your first cue to pursue the game’s story, to unravel the narrative that whizzes past you like the city in the background, barely giving you time to chart its contours.

And so you give chase: putting out fires in passing buildings, conducting electricity to light up a community, changing the hands of a beaten-up clock. You solve puzzle after puzzle, never knowing exactly what you’re doing or what you’ve achieved, but incrementally the fragments begin to take shape, and you start to connect the dots. Dark Train‘s mode of storytelling might be the most shrouded I’ve seen in a while. It’s what gives it an allure as the game slowly sheds a little more light for you on its dark world.

You can purchase Dark Train on Steam and find out more on its website.

The post Dark Train is a mystery made of paper worth unfolding appeared first on Kill Screen.

Let the kids flip water bottles, they need it

It begins with the blankie. Mother isn’t able to comfort you all day every day, and your developing brain is rapidly attuning to that fact. But you also aren’t able to comfort yourself, not yet, not entirely; the feelings are too strong, language and notions of cause-and-effect relationships too nascent. And so the blankie.

It is, by all accounts, an ordinary blankie. But in your tiny hands it possesses a special power, one that until now has been the exclusive purview of your mother, which is the power to comfort. Of course, even your young and elastic mind can appreciate that this blanket is not really your mother, and that it’s not really alive. Yet it’s not not alive, because you have given it life. When you’re scared, the blankie soothes you. When it’s accidentally left behind at a restaurant, you go into conniptions. The blankie grants safety—hence the phrase “security blanket”—but even more important is the source of that safety: by imbuing a mundane object with humanity, you have built a bridge between the outer world, where your mother lives, and the inner world where you alone reside. This is what psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott recognized when he identified the blankie as one instantiation of a much broader phenomenon that he called “transitional objects.”

you have built a bridge between the outer world

Early transitional objects, be they blankets or teddy bears or imaginary friends, are private. They hold great power in the eyes of their creators but appear ordinary to everyone else. These objects often take on primary emotional functions: they calm when scared, soothe when upset. As time goes on, however, we begin to share our transitional objects, and their purposes become more varied and nuanced.

Consider the following: Two children are in a park, running around. One picks up a small stick and says to the other, “I am an evil wizard. This is my magic wand and I cast a freeze spell on you.” Without missing a beat, the second child stops motionless in her tracks.

How do we understand such an extraordinary turn of events, which in fact is the kind of typical play behavior anyone who spends time with children will see on a daily basis? The stick is not a magic wand, it’s a stick. But one child has decided to bring it to life and, in turn, grant her the ability to control others. Even more remarkably, the second child chooses to see what the first child sees, and allows herself to be controlled. They are sharing a transitional object, but between what and what are they transitioning?

play is the activity that rests at the core of human socialization and creativity

In infancy, the blanket serves to move the child from being comforted by the mother to being comforted by the self. The children in the park, on the other hand, are transitioning deeper existential notions into their conception of self, trying on powerful feelings for size within a safe and temporary playspace. Together they can explore what it’s like to be strong and weak, sadistic and kind, good and evil. Most likely after a few minutes, the roles will switch: the first child will hand the stick to the second and say, “Okay, you be the evil wizard now.”

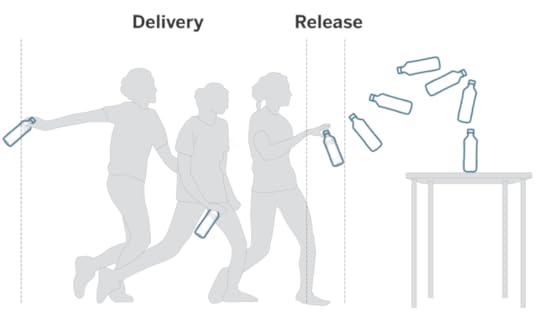

Our capacity to animate the inanimate is, according to Winnicott, one of the foundations of play, and play is the activity that rests at the core of human socialization and creativity. The use of objects to safely explore overwhelming aspects of living is relevant throughout the lifespan, and can help us to understand why play remains important to us into and throughout adulthood, even as the nature of play can take on subtler or more unexpected forms. We explore with issues of aggression and mastery through trying to make a ball go through a hoop. We view the world through one another’s eyes by debating what a bronze sculpture “means.” And sometimes, as reported by The New York Times, six million teenagers start flipping plastic water bottles and going absolutely berserk.

The Times piece presents this “craze” predominantly as an annoyance for parents, something they do not understand. Here is the transitional object at work, the animus that only some can see. To the average grown-up, it’s just a water bottle: it crinkles when their child grabs it, sloshes as it’s tossed in the air, and clunks as it lands (hopefully) right-side up on the table. In short order this sound loop becomes extremely irritating because, to the parents, it is meaningless: crinkle-slosh-clunk over and over for no reason, like a form of torture.

the deepest human drive – the drive to play together

Play is wholly a matter of perception: for it to work, participants must agree that they all see the same thing. If someone breaks the illusion, transitional objects lose their vitality and play is spoiled. Say you were to go up to those kids in the park and shout, “Hey stupid, that’s just a stick!” In effect, you would be forcing them to either justify their version of reality, creating a split between your subjectivity and their own, or abandon the object entirely and quit their game. (Note: please don’t yell at children.) While younger kids are likely to become overwhelmed under such pressure, adolescents are at a developmental stage marked by the transition from childhood to adulthood, and so rebellion against the perceptions of authority figures can be regarded as most welcome. The baby thinks, “This blanket has some of my parents in it” and feels safe; the teen thinks, “This water bottle has none of my parents in it” and feels liberated.

The virality of social media has upended any notions of playspace that Winnicott might have predicted in his mid-20th century heyday: one high schooler bottle-flipping in North Carolina can energize peers the world over. “It makes you feel accomplished,” said a teen named Alex in the Times piece, which (pardon the pun) holds water: notions of accomplishment and success are exactly what we would expect a 17-year-old on the precipice of social and legal independence to project onto a transitional object.

But flipping bottles also, I would imagine, makes Alex feel connected. He may be doing so alone at his kitchen table, but on some level he knows countless others are doing the same thing at the same time, near and far. His water bottle is just one instantiation of the communal water bottle being flipped, which makes him part of a monumental play experience that links him to his peers, and sets him in juxtaposition to his mom who just doesn’t get it.

The “craze” is so-called by adults, because they don’t understand and see the pastime as mindless. But there’s nothing crazed about it. In fact, bottle-flipping teens are demonstrating to all of us the unique powers of the transitional object: its capacity to defy time and space, and transform even the most ordinary thing into an expression of one of the deepest human drives, the drive to play together.

The post Let the kids flip water bottles, they need it appeared first on Kill Screen.

One game creator’s way to overcome depression? Make an uplifting game

The blinds are drawn. The room is dark and quiet. It’s past noon, and you’re still in bed. Your eyes are fixated on the carpet, bland and beige. The walls are white and bare, the furniture is hard and stiff. What is supposed to be a safe and comfortable space feels more like a prison—you are trapped. You haven’t showered yet, and your stomach reminds you that it needs attention. Your body is screaming at you to get up. Get out of bed. There’s work to be done. But moving is a chore. The signals that travelled to your brain are met with static. You remain curled in the fetal position, choosing instead to drown your conscious with re-runs of The Office on Netflix. As the upbeat piano of the theme song plays, you feel nothing.

///

It can be incredibly difficult to pursue creative endeavors when depression gets in the way of productivity. Ciara, who creates pixel/voxel art and “tiny games” details the struggle in a recent Patreon post. She’s been developing a game called Voxel Bakery and posts updates frequently to her Patreon page. But her most recent post details the struggle of working while depression and anxiety are at play.

“tricks me into thinking everything I do is worthless”

“I’ve been spinning my wheels big time with 3D game development. And a host of other pesky and depressing minor health problems hit me all at once,” Ciara wrote. “Not to mention, of course, depression and anxiety, which tricks me into thinking everything I do is worthless.” However, in response, Ciara’s solution is to start development on a game called Picky Pumpkins.

You’ll play as LaLa, a “youngun tasked with collecting pumpkins from your grandmother’s community garden so she can make her award winning pumpkin pies!” Ciara’s drive to continue creating in order to combat the lows of mental health with such a cute and positive game premise is wonderful. Hopefully her persistence inspires others to continue against the odds too.

To see Ciara’s Patreon post on Picky Pumpkins and learn more about her work, click here.

The post One game creator’s way to overcome depression? Make an uplifting game appeared first on Kill Screen.

NYU Game Center’s new scholarship targets women game designers

Famously, the videogame space can be an unpleasant place for women. From professional game designers to the most casual game players, women have repeatedly encountered a two-fold problem when exploring the world of videogames: our experiences are continuously ignored (often accused of being “fakes”) and suffering a slew of personal attacks.

Last week, the NYU Game Center, the Game Design program within the Tisch School of the Arts, announced the Barlovento Scholarship for Women in Games. It’s aimed at women who wish to pursue a graduate degree in game design. The scholarship is funded by the Barlovento Foundation, whose founder, Vanessa Briceño, graduated from the Center in 2015 with an MFA in game design.

“It is vital that we send the message that women are welcome”

Beginning in Fall 2017, all female-identifying applicants to the Center’s MFA program will be automatically considered for the scholarship, which will grant full tuition for three MFA students over the next six years. Briceño views this as just one part of the Barlovento Foundation’s mission to open doors for women and girls interested in game-making and coding.

Image via Girls Make Games

“Our goal with the Scholarship is to encourage women to pursue game design as a career and to see the industry as expanding and inviting,” said Briceño, who is currently working as an independent game researcher and writer based out of Houston, TX. “It is vital that we send the message that women are welcome and needed as diverse voices and creators within the gaming industry.”

Frank Lantz, chair of the Game Center, has expressed his full support: “The game industry, and technology in general, can be a hostile, unwelcoming place for women. We want to do everything we can to overcome this problem. We want to send the message that women’s voices are needed in game design. We need their perspective, their creativity, their passion, and their energy.”

For more information about the Barlovento Scholarship and the NYU Game Center, go here.

///

Header image via NYU Game Center

The post NYU Game Center’s new scholarship targets women game designers appeared first on Kill Screen.

Japanese artist creates music with obsolete technology

A lot of newer music has been deemed inane and ridiculous for sounding like broken technology. Dubstep’s sound, for example, has been compared to the sound of hitting a metal pole with a chainsaw, the sound of robots dying, the sound of a root canal. According to Wendy’s: “Dubstep sounds like a broken Frosty machine.”

Dubstep sounds like a broken Frosty machine.

— Wendy's (@Wendys) March 6, 2012

However, artist Ei Wada embraces the sounds of the old and broken with music that repurposes obsolete fans, TVs, and radios by turning them into instruments. Wada’s work with such technology tends to combine unique sounds with striking visuals. In 2014, he did an installation featuring helium balloons attached to six magnetic tapes with different voice pitches recorded on each as part of his membership in the Open Reel Ensemble, a group that performs with vintage open reel tape recorders. Wada has said before that some of his work with tape recorders is more like an art installation than a musical performance.

effectively turning the TVs into percussion

Wada’s use of TVs as audio-visual instruments came to him by accident, unlike his participation in the Open Reel Ensemble. After plugging a sound cable into a composite video connector port and seeing the sound on the screen as an image, Wada began pairing tube televisions with PC-controlled video decks at different pitches, effectively turning the TVs into percussion. Wada has taken this project, called Braun Tube Jazz Band, to a number of different cities and venues.

The unique sound, combined with Wada’s clear passion and joy when performing, make it easy to see why he’s been successful, having won the Excellence Award in the Arts Division of the 13th Media Arts Festival of the Agency for Cultural Affairs in Japan. Originally from Japan, Wada has brought his music to people all over the world, visiting places like Australia, Spain, Germany, and Switzerland.

Learn more about Ei Wada and his music here.

The post Japanese artist creates music with obsolete technology appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers