Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 32

November 3, 2016

Thing-in-Itself brings Kant’s philosophical expression to videogames

Videogames and philosophy are hardly strangers. Look to BioShock‘s (2007) exploration of Objectivism, the Determinism of The Stanley Parable (2013), and The Talos Principle (2015) with its toying of Functionalism and Behaviorism (and many other philosophies). The interactive nature of videogames, along with their basis in manipulating systems and limitless virtual spaces, allow for them to serve as ideal capsules to teach players the doctrines of a philosophy.

For the most part this is done implicitly—without prior knowledge, the player probably won’t realize that they have in fact been exposed to the concepts belonging to a certain philosophy. Rather than taking the Portal (2007) approach to education and assigning a test lab for each lesson with clearly explained rules and end goals, philosophical videogames tend to build their school of thought into the narrative, weaving ideas into their worlds and often having the player make choices that have ulterior consequences.

it’s successful as a short, interactive introduction to the idea

Example: When faced with the choice of two doors to enter in The Stanley Parable, the narrator says that you take the left door, an instruction you can choose to follow or deny. Both choices are fine—there’s no right and wrong—because one of the lessons of The Stanley Parable and Determinism is that every choice you make has already been decided for you. The decisions you make are inevitable due to a number of social and logical factors that lead up to each moment in your life; free will is an illusion. But for as proud and self-referential as The Stanley Parable is, it never actually stops to say, “Oh, this is the concept of Determinism, by the way.”

Arseniy Klishin and Laura Gray, known collectively as Party for Introverts, have ignored this trick with their upcoming debut game. It’s an interactive short story informed by Immanuel Kant’s expression “thing-in-itself” called … Thing-in-Itself. So much for subtlety. It also opens up with a couple in bed talking about Kant’s philosophy and how it can be applied to life. But while the game takes this direct approach to tackling a philosophical concept and proves somewhat simplistic and obvious as a result of that, I think there’s plenty of value in it still—it’s successful as a short, interactive introduction to the idea of “thing-in-itself.”

To briefly explain, “thing-in-itself” is the idea that any object has an existence independent of the human mind’s perception of it (Kant called the reality devoid of human perception the noumenon, while phenomenon is the observed and perceived world we’re used to). Ultimately, this means that we cannot understand the true nature of anything else in the world—we are limited to our own senses and intellect. Thing-in-Itself, the game, actually explains this well at its beginning, even if the context for its discussion—a couple in bed after attending a party—is a little implausible.

It then goes on to illustrate how our state of mind can alter objects through perception. A bottle of whiskey, for instance, is first seen as a new taste introduced to the man in the relationship, to being “earthy shit” once they break up, and then turns into an icon for his forlorn state once his anger dissipates and he starts to miss his former partner. It’s simple and the depression episode is becoming somewhat overdone in narrative games now, but it does the job at least. And, in fact, by the end, when every object in the guy’s room is turned into a number, I think the game comes back round to its strengths.

In any case, I’ve only been able to play a beta version of Thing-in-Itself, so I’ll reserve my full judgement. And I always appreciate the effort to inject a videogame with a philosophical concept no matter how it turns out.

Thing-in-Itself is due to come out for PC in January 2017. You can vote for it on Steam Greenlight and find out more about it on its website.

The post Thing-in-Itself brings Kant’s philosophical expression to videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

Look out for a boardgame about organizing protests

I work, live, and study in Washington, D.C.—undoubtedly one of the world’s most political cities. Here reside the highest stratum of politicians, lobbyists, and corporate cash-mongers. Here, too, live the downtrodden, the marginalized—systematically oppressed people of varying color, socioeconomic status, and gender identity who the government promised to uplift, but, in effect, did quite the opposite. It only takes one stroll through Georgetown to understand how economically and racially segregated this city is.

Washington is the world’s welcome mat to the United States: a city that is supposed to encompass all that America loves and strives for. And it does precisely that, if you never stray further than the National Mall or Embassy Row. Venture beyond these sights, onto a college campus or a historically black neighborhood, and you’ll feel just how desperate the need for change is. D.C. is assuredly a melting pot, but—like many other places in the country—it’s one that’s boiling over. Fast.

It isn’t a day in D.C. without a protest (or four). Sooner or later, all of these protests sputter out. Cops shut us down, people lose their voices. Lack of organization is usually the biggest culprit. Many young students like myself come to D.C. with the hopes of honing their activism, and making real strides towards change either systematically (through lobbying and legislature) or asystematically (protests, sit-ins, etc.). Unfortunately, there’s no class on “Activism 101.” There’s no textbook or counselor to help you build, coordinate, and strengthen a movement you’re passionate about. But thankfully, there will soon be a game about it.

there’s no class on “Activism 101″

Rise Up, a boardgame by the Chicago-based Toolbox for Education and Social Action (TESA), is a game in which everyone wins, loses, and grows together: not unlike any other social movement. Your opponent is vaguely titled “The System,” and your “movement” can be whatever you like: it can either be based in reality (like stopping an oil pipeline) or fictional (like fighting for dragon rights). But “the System” is hard at work too, maneuvering to crush your movement through tactics like setting up surveillance, making arrests, or causing infighting. With your team, the aim is to spread your influence to 10 “locations” around the board: college campuses, workplaces, neighborhoods, etc., while “the System” actively tries to trip you up at each turn.

One of the more impressive things about Rise Up is that it comes with a children’s version too: a simplified, non-threatening way of encouraging young people to channel their passion effectively into practice. The tools to successfully bring about social change are desperately lacking at every age level: even in the Anthropology department at my university, we struggle with strategizing and getting ideas beyond the “ivory tower.”

The game is impossible to beat without teamwork. Brian Van Slyke, cofounder of TESL, said this about the cooperation mechanic:

“What we really want people to take away from the game, is that just like Rise Up, movement building is a cooperative process. It’s a cooperative game, so the game is playing against you. It really requires people working together to beat the system.”

Since moving to Washington three years ago, I’ve attended a number of protests revolving around feminism and racial justice. Black Lives Matter protests consistently had the biggest turnouts and the highest energy. They are impossible to ignore. Even for those who stand idly by, their day has been interrupted by the very real assertion that black bodies are being disproportionately persecuted by authorities. There are those bystanders, and some who take video too, but these triumphant marches through the streets of D.C. often end with larger crowds than they began with.

Many people, of all backgrounds and colors, are mesmerized and welcomed in by the indomitable presence of Black Lives Matter. Many are eager and willing to uplift each other via social justice. But, like most budding activists, we aren’t sure what to do after the fact. Organization and consistency are key issues in activism—logistical strains on top of physically and emotionally taxing work. Rise Up is a game that aims to provide an uplifting model, without a hint of cynicism, through which to test and retest tactics for activism. If it’s used as intended, in committed educational settings, it could dramatically change the ways we bring about social change.

You can find out more about Rise Up and support it over on Kickstarter.

The post Look out for a boardgame about organizing protests appeared first on Kill Screen.

A game about keeping a plant alive while trapped inside your house

Last October, South Carolina made headlines when a thousand-year rainfall put much of the state underwater—that is, the chances of that amount of rain falling in a given year are 1-in-1,000. The storm drove residents from their homes onto dangerously flooded roads, leaving others trapped and in need of rescue.

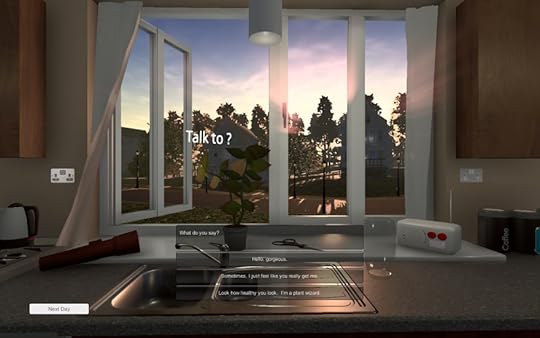

Water Me, created as part of Indie Grits 2016’s Waterlines project, is a response to this historic flooding. Atmospheric and contemplative, the game explores the experience of being stranded in your house, cut off from the outside world by the encroaching storm, with only your potted plant for company. Your objective is to keep this plant alive.

Your morale withers along with it

Featuring real broadcasts from the South Carolina public news radio before and during the flood, Water Me takes place over the course of a week. Given the option of watering your plant and proceeding quickly to the next day or lingering over details, the player can fight the tedium of waiting out the storm by watching the water levels rise; listening to music or the news; providing your ailing plant with some artificial sunlight in the form of a flashlight beam; pruning its leaves; and, most illuminatingly, talking to it.

As the storm rages outside your open window, your tap water becomes contaminated and your plant, deprived of sustenance, begins to wither. Your morale withers along with it, turning your dialogue options from cheerful (“Look how healthy you look. I am a plant wizard.”) to guttural (“Fuck.”). Is it even possible to keep your plant, which you are asked to name at the start of the game, alive? That’s something you’ll have to find out.

Try to help your leafy friend survive the storm in Water Me here.

The post A game about keeping a plant alive while trapped inside your house appeared first on Kill Screen.

Sara is Missing is some good text-message horror

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Sara is Missing (Windows, Mac, iOS)

BY MONSOON LAB

Films like Unfriended and the recent Blair Witch have tried to bring the found footage genre into the digital age with varying success. But the attempt seems much more at home in Sara is Missing, a free game by Monsoon Lab. In it, you come upon a phone with an Intelligent Recognitive Iconolatry System (I.R.I.S.) that takes you through its owner’s last known whereabouts and moments. Best played on an Android device (but available otherwise), Sara is Missing takes the familiarity of your phone’s home screen and turns it into something alien and horrifying. With a mystery that unfolds with incredible pacing and broken text message speak, the game compels you to keep clicking through Sara’s life even while your heart screams, “delete, delete, delete!”

Perfect for: Milennials, iOS systems, anyone with a phone

Playtime: 10 minutes

The post Sara is Missing is some good text-message horror appeared first on Kill Screen.

Civilization VI is more game than drama

Before Civilization VI’s official release date, those with access to the unreleased version of the game were treated not to the ‘official’ theme on the game’s title screen, but with what would prove to be the theme music for the American civilization. The piece is a combination of two very different, very American pieces of music: the opening is lifted straight from Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man.” The rest is an orchestral arrangement of “Hard Times Come Again No More,” a 19th-century parlour song by Stephen Foster—the man who wrote mainstays like “Camptown Races,” and “Oh, Susanna.”

The first is a brass-based commission that stemmed from America’s entry into World War Two, and was meant to invoke, in some way, the democratic spirit and the seriousness and dignity inherent to each man and woman. The second is more whimsical, while the tune is more comforting and folksy. Despite the song’s subject matter—a reminder that sorrow is just around the corner—it is still comfortingly small, reminiscent of Foster’s other works, which are now mainstay nursery rhymes. In a word, the second component of the American civilization’s theme is a certain kind of levity.

nothing sours a mood more than realizing your conquest has cost literal millions of lives

The theme encapsulates two binary poles that the various versions of Civilization have tried to navigate over the years. On the one hand, the series carries itself with a seriousness due to trying to capture the scope of human history and the weight of our species’ works; on the other hand, it is merely a game, and has never permitted itself to be taken too seriously—think of, in Civilization IV (2005), hearing Leonard Nemoy ‘quote’ the satellite Sputnik by saying “Beep. Beep. Beep.” The videogame has to be light, after all: nothing sours a mood by realizing that your conquest of a city has cost literal millions of lives. But, at the same time, Civilization has never been so light as to lose its reverential attitude. The “in joke” of Gandhi as a nuclear sociopath is a regular feature of the Civilization series, but the game nevertheless pays tribute to Indian culture and heritage with Varos, Stepwells, and a religious mechanic that recognizes the country’s diversity of faith.

What’s changed with the latest incarnation is that it seems to be pursuing levity over awe. Take, for example, the quotations that accompany each scientific discovery. These epigraphs have been a feature of Civilization since IV, but they’re never been so uninspiring. You can contrast the tone of that for the writing technology in Civilization V (2010)—John Milton: “He who destroys a good book kills reason itself”—with that in VI—Mark Twain: “Writing is easy. All you have to do is cross out the wrong words”—and not feel as though there is something emotionally flat about the tech tree’s connotations. I mean, the sanitation technology quotes Life of Brian (1979)—“Apart from the sanitation, the medicine, education, wine, public order, roads, the freshwater system and public health … what have the Romans ever done for us?” It’s cute, but it’s not emotionally moving in the way the series has always tried to be.

This kind of levity or humor extends throughout the entire game: using the workers to repair a pillaged farm has them cartoonishly jump around, furiously rattling their hammers as they fix things. The caricatures of various world leaders vary from Gaston-like Gilgamesh to roly-poly Qin Shi Huang. Indeed, fan reaction after the reveal of a simply corpulent Teddy Roosevelt led to Firaxis dialing back the hyperbolic nature of his caricature. This exaggerated quality even extends to the AI: in an attempt at differentiation and distinction, computer-controlled civilizations now have specific agendas. Montezuma wants to have the most luxury resources, while Qin Shi Huang dislikes those who have more wonders than him. What this leads to is hyperbolic, Saturday-morning-cartoon-villain overreactions: Huang declared war on me when I had a single Wonder more than he did, and spent the rest of the game stewing in utter resentment and incessant denouncements.

The city district system fits neatly into the game’s marriage of its native sense of levity with this sense of exaggeration—of growing larger and more pronounced, for what is a sequel but more of the same? Cities, once limited to a single tile stuffed with improvements and buildings, now have expanded outwards. Different districts—from entertainment to industrial to scientific—are designatable, and provide loci for the buildings that would earlier have hidden in the single-tile city, adding to your ability to produce science, culture, or provide other bonuses. This, of course, leads to bizarre cities where people living downtown have to travel past a farm to go to the opera or to the bank. But it works well with VI’s heightened sense of exaggeration. As no city can do everything at once, each city becomes a hyper-focused machine of culture, gold, production, and so on. Wonders now demand individual tiles, often with incredibly specific requirements: the Pyramids, for example, require a flat desert tile. In the same vein, the civilizations themselves are broken down into further discrete specializations and bonuses: there’s the leader bonus, the civ bonus, the unique building or district, and the unique unit. Numbers and bonuses pile upon bonuses and numbers until the player is given a Civilization that wears its game-ness on its sleeve.

levity over awe

In part, this is because this version of Civilization feels like the ‘most’ Civilization: the normal pattern of the series is to release a new, pared-down version, and then embellish the videogame over a series of expansions. Instead, Civilization VI carries forward almost all of the mechanics from V: spies, trading routes, religion, ideologies, the hexagonal map, and so on. As a result, the game is just as strong as its previous incarnation, while nevertheless finding ways to expand upon this experience. The Settlers-of-Catan-ification of Civilization is in keeping with the mechanical strengths of the series: the player has always crafted these expanses of mines, mills, and farms; now she can add libraries and museums to her quiltwork.

But there’s a sense in which this emphasis on function at the expense of form strikes the wrong note. Another new addition is the casus belli system, which lets you declare Holy Wars, wars of expansion, and colonial wars for a lower warmonger penalty—these are mechanical elements, named for the sake of flavor. But the seriousness of these names and their weight is wholly absent when Philip II of Spain dramatically overreacts to the player’s declaration, when cities are disappeared at the click of a button, and when any damage your farm or mines suffer is instantly repaired with a frenzy of Looney Tunes-like work. In earlier games, declarations of war would come with their own serious soundtrack because war is serious. In Civilization VI, the medley of “Fanfare for the Common Man”/“Hard Times Come Again No More” keeps playing. The game carries on as before.

More than ever, Civilization is torn in two directions: lightness and weight, exaggeration and appreciation, play and purpose, mere game and serious awe. The opening cinematic has always described human destiny as a teleological journey into the stars—but here I research poetry and learn, upon researching poetry, that “Poets have been mysteriously silent on the subject of cheese.” Yet Civilization VI still works as a Civilization game. The suburbanization, the cartoonish aesthetic, and the “one more turn” addictiveness are still recognizable parts of the core experience people keep coming back for. It is still a full, massive, joyous videogame, even if I have to squint to find the joy beneath mere wit—but the two extremes are now growing wider and wider apart. How long before the fabric of the game snaps under the strain?

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Civilization VI is more game than drama appeared first on Kill Screen.

November 2, 2016

Keyboard Sports wants you to find joy in using keyboards again

Keyboard Sports turned my Spacebar into a couch and that is so darn delightful. Thank you for that, Keyboard Sports.

I’ve never really seen my keyboard as anything other than a set of lettered keys before. I barely look at it as I jam my fingers into it every day, typing up my thoughts, but now it has regained my attention—it’s like my imagination from childhood has been reawakened. Now I see that my keyboard can have its own geography: each key could be a building as part of a city, or a single tree in a forest. With the right mindset, a keyboard could be the topography for almost anything, and Keyboard Sports is a game that wants you to see that.

“You will almost feel like a kid who has discovered the keyboard for the first time, and this is important to us because it looks like the keyboard is slowly disappearing and the next generation might grow up without one—and who wants that?” said Tim Garbos, one of the game’s designers.

gaining CTRL of the self, and entering the inner SPACE

It has you control a little yellow person as they complete a number of challenges by using your entire keyboard to guide them around the screen. All you do is press a key on your keyboard and the character will run to its corresponding location on the screen. Keyboard Sports gets plenty of mileage out of this set up, including its own version of Frogger (1981), a take on the twin-stick shooter, and a platformer that turns some keys into lava and others into safe ground.

It’s also memorable for the narrative details that inform each challenge. You follow the guidance of Master QWERTY on a quest to find your Inner Key. Mostly, this involves drinking special T (tea), learning to ENTER and ESC his home, gaining CTRL of the self, and entering the inner SPACE. Like I said, Keyboard Sports gets a lot out of using the keyboard as its central conceit, weaving a humorous, playful tale of transcendence full of appropriate puns to accompany the tasks it assigns you. I kinda love that it opens up by dismantling the demands of traditional sports, too—your character runs across a racetrack, crashing through the hurdles, as you mash your keys trying to work out what to do.

Keyboard Sports has been made as part of Humble Originals, which is a program to fun small games by Humble Bundle, and is therefore exclusive to them. As such, if you want to play Keyboard Sports, you should sign up to receive the November lineup of the Humble Bundle Monthly for $12—you only have until November 4th to do that. However, the creators of Keyboard Sports also plan to release an extended version to other platforms in 2017 (Humble Bundle Monthly subscribers will get that version at no extra cost). So if you miss out now I guess it’s not the end of the world.

Find out more about Keyboard Sports on its website.

The post Keyboard Sports wants you to find joy in using keyboards again appeared first on Kill Screen.

Inquisitor is a hypertext engine that puts spatiality first

“I think games are uniquely suited to doing interesting things with spatiality, it doesn’t matter what form this takes—pure audio, pure text, pure 2D, pure 3D, or any combination of these, games are just really good at spaces.”

These are the words of Orihaus, a game maker who has made some of the interesting 3D spaces I’ve visited in recent years. Mostly, they are pitch-black alienscapes that writhe with elegant onyx architecture and an outright ominous aura. Games like the “dark striptease” of Obsolete (2012), the “constructivist megastructures” of Aeon, and the “virtual memory palace” of Xaxi (2013). But more recently, Orihaus has turned his attention towards interactive text, and it’s here that he’s expanding on his expression of virtual space in new, much vaster ways.

create impossible and paradoxical worlds

For his game To Burn in Memory (2015), which has you explore a city that never existed, Orihaus created his own interactive fiction engine called Inquisitor, which is “built around putting spaces at the core of hypertext work.” More specifically, Orihaus describes it as being a hybrid of Twine and Paradise—the former is perhaps the most accessible spatial hypertext game engine out there, the latter is more complex, built to create multiplayer worlds of text where players can create and become any object they wish. “The main thing I’ve taken from them is the non-linear world structure/navigation from Paradise, and the ease of use for larger projects from Twine,” he said.

Orihaus also noted that, due to Paradise’s influence, it’s possible for users to create impossible and paradoxical worlds, and also ones that are able to constantly reconfigure themselves so that a text-based roguelike is completely plausible with Inquisitor. This probably sounds a little confusing, and trying to explain how it all works can exacerbate that, which is something that Orihaus is currently tackling as he puts together a tutorial for Inquisitor. I gave the tutorial a go (in its unfinished state) and found it simple enough—once you grasp that a word can contain an entire world inside of it (made of other words and links)—with planets, cities, districts, buildings, whatever you wish—the basics fall into place pretty quickly.

What might be more surprising for people interested in making interactive fiction is that Inquisitor has no editor, “but that’s no issue since the worlds are just plain-text files and don’t require the user to write any code,” Orihaus said. The main tenet that development on Inquisitor follows is that it should allow for game makers to sit down and write with ease on any platform they wish. This is something Orihaus is trying to improve over Twine, whose little input windows he found awkward when working on large projects: “Honestly, I just wrote the engine to read the scripts raw, those I was writing to be converted to Twine.”

This is something he keeps in mind when adding new features, such as the “salience-based dialogue system” he’s currently working on implementing. The term for this type of dialogue system was coined by interactive fiction author Emily Short, which she describes as “narratives that pick a bit of content out of a large pool depending on which content element is judged to be most applicable at the moment.” While Orihaus was figuring out how to fit this kind of system into Inquisitor, he saw the diagram that Short drew below, and realized that it looked a lot like how his engine lays out world structure.

“And so taking a leaf from Paradise’s book, my implementation so far is to just have a miniature world inside a character’s head that you can navigate through dialogue options, keeping track of a bunch of basic tags that a writer can define (If ‘annoyance’ is too great they will just tell you to get lost or block off certain areas, but if ‘intimidation’ is higher then [they can] override that, for example),” Orihaus said.

He also has plans for a dynamic music system like those found in the later Myst games, “where you have a collection of individual ambient channels that fade in and out based on a number of variables.” But before that all that, Orihaus said that ease of use suggestions from other writers planning to to use the engine are his main priority. “Half the reason I’m putting the engine out there is that I love writers like Porpentine, and if this encourages even one new writer like her to express herself then it’s all worth it,” he said.

Currently, Orihaus is making a game called The Silver Masque using Inquisitor. You can get Inquisitor for yourself on Github. Check out the work-in-progress tutorial here. And follow Orihaus on Twitter for updates.

The post Inquisitor is a hypertext engine that puts spatiality first appeared first on Kill Screen.

Thatgamecompany teases new multiplayer game “about giving” for 2017

Thatgamecompany has teased its next game after Journey (2012) with an image and the promise of its arrival in 2017. It’s also been confirmed that, unlike thatgamecompany’s previous three games—flOw (2006), Flower (2009), and Journey—it will not be exclusive to PlayStation platforms.

The teases came yesterday on the studio’s Twitter account and a blog post. The first was an image of a lit candle about to light another one, with the words “a game about giving” accompanying it, as well as a link to a new Twitter account specifically for this new game, @thatnextgame. That account’s profile description also tells us that it will be a multiplayer game available on multiple platforms, and has a score by thatgamecompany’s audio director Vincent Diamante—that’s not the same composer of Journey‘s score; that was Austin Wintory, if you’re wondering.

a magical-looking square arch made of stone

The second image was a silhouette of four children holding hands while seemingly skipping along. The third and final image seems to either be concept art or a screenshot showing a magical-looking square arch made of stone, with a glowing shape on it. There’s also a strewn path of stones leading up to it, and a big emphasis of the image is the blue sky and clouds, at the top of which is another glowing shape that seems to have some line of communication with the square arch.

That’s all the details on this next game from thatgamecompany for now. It should probably be noted that while this is the same studio that created Journey it is not quite the same team. Jenova Chen, the director at the studio remains, but producer Robin Hunicke left to work at Funomena on Wattam, designer Chris Bell departed to work on What Remains of Edith Finch with Giant Sparrow, and lead artist Matt Nava formed the studio Giant Squid and released Abzû earlier this year.

Look out for more details on thatgamecompany’s next game on its website and Twitter account.

The post Thatgamecompany teases new multiplayer game “about giving” for 2017 appeared first on Kill Screen.

There’s a good reason you don’t know much about survival horror game Routine

It’s been four years since first-person, survival-horror-in-space game Routine first pinged on my radar, and I barely know more about it now than I did then. This isn’t due to negligence on my part—Lunar Software, the team making it, have been very stringent on what info they put out into the wild.

This hasn’t changed with the latest update on the game’s progress: specifically, a trailer and the reveal that it should be out in March 2017. There’s little in this new trailer that we haven’t seen before, including an abandoned lunar base, the handheld scanner-cum-gun, and a nasty man-robot stomping on our face.

“People probably don’t know what to quite expect from the game”

What does make this new footage different is that we now live in a post-Alien Isolation (2014) world, and many people commenting on YouTube have saw fit to compare the two games. They’re not wrong to—both take place in a space base where some shit has gone down (people are either dead or missing), they both have a 1970s tech aesthetic, and in each there is something terrible stalking the player.

It is with this in mind that I decided to ask designer Aaron Foster how he would explain Routine differs from Alien Isolation. He actually gave a better answer than I was expecting. “There are a lot of differences with Routine but I would say that the most obvious one is that we are a completely different IP and with that comes the unknown,” Foster began.

“People probably don’t know what to quite expect from the game as we’ve tried very hard to be as vague and spoiler free as possible with all the stuff we put out. We could go bloody crazy and start throwing supernatural elements in there and people may not expect or question it (if done well) because it would be part of the world we have created.”

And it’s true. Like I said, I’m not sure what to expect from Routine other than to be dominated by my new robot-daddy. It’s why another of one of my questions was desperately asking about Routine‘s themes, making the comparison to SOMA (2015), which used the survival horror format to explore ideas of consciousness in humans and machines. I thought Routine might go a similar path, but nope, Foster denied that outright: “We don’t have a super strong philosophical story like SOMA, its not something we ever planned for with Routine.”

The most I could get out of him was to explain how the death system in the game works. I dunno about you, but I don’t expect a game like Routine to have “permadeath,” but it does. I guess that’s proper survival horror—Foster said he wanted to engineer a way for players to have a “fear of actually losing something.”

“the act of playing through again shouldn’t be too painful”

To alleviate your worst fears, the game does have an autosave system, so you can leave the game at any time and come back to the same spot. But if you die then you have to start again from scratch. “We are still tinkering with one or two elements of permadeath as we want to make sure there is never a cheap death,” Foster said.

“We know it is really important for us to balance as we know it can be frustrating to a lot of people, but Routine isn’t completely linear either and with multiple endings the act of playing through again shouldn’t be too painful.”

After getting this answer from Foster, my biggest hope for the game is that it does something clever with this repetitious format—it’s called Routine after all. But honestly I don’t know what to expect, really, and that’s kinda rare for a game these days. There’s something to admire in Lunar Software’s laconic approach.

You can find out more about Routine on its website.

The post There’s a good reason you don’t know much about survival horror game Routine appeared first on Kill Screen.

Ladykiller in a Bind dares to ask “what are you into?”

You lie on your bed, idly, unsure of what is keeping you up. It’s something that wants to stay hidden, just out of sight of your mind’s eye, a shadow ducking out of your periphery—the flash of a sly smirk as it flits around your room. While the thing on your mind dodges investigation, your hands nervously fiddle with your skirt, anxious to make your brain comply with what you want it to do. Your gaze wanders from your legs to your laptop a few inches away. You had just been on it, in a virtual world, only 20 minutes ago, playing a game…

Then it hits you. All at once, like an ass being smacked with a cane—you realize what was on your mind while you idled, wasting time, on your bed sheets. Of all things, a videogame. Or, more specifically, a character in a videogame, which is an even bigger rarity. So few videogame characters can even be considered “characters” in the literary sense, barely occupying your mind while on screen, let alone in the real world. But the person on your mind, the crush that had been evading your inner gaze, is so unshakably human that you find yourself giggling like she’s Leonardo Dicaprio circa 1997.

“Princess.” You say her name, and it feels so right on your tongue. “Princess.” Like home, the smell of apples and pine trees. “Princess.” You close your eyes, only to see a long sweep of fiery red hair.

Your eyes open: the hair is gone, the taste of her name evaporates, the scent of home turns acidic. All you’re left with is the distinct embarrassment of realizing you’ve been crushing on an anime character. But it feels like more than that. The most delicious part is that it feels like the love you share with yourself—like flirting with your reflection in the mirror. You don’t want Princess; you are Princess, and what she brings out in you. You don’t love her for being a fantasy. You love her for seeing you, for making you see yourself.

///

Ladykiller in a Bind is a game about labels. Every time a character is introduced, the player has the option to call them one of two pre-scripted nicknames, or create their own. All the pre-scripted nicknames harken back to a romantic fantasy or “type” of kink—this is an erotic visual novel, after all. Christine Love and the Love Conquers All team set out to explore a story of lesbian cross-dressing and BDSM-infused social manipulation. You play as “The Beast,” AKA “The Hero,” who decides to take over her twin brother’s identity during his senior class cruise—only to proceed to fuck every one of his classmates.

The summary of Ladykiller in a Bind should already give a sense for how central labels are to its story. Just look at the game’s main page, where you’ll find a summary of each character beside a chart indicating their pension for “crossdressing,” “lies,” “fashion,” “status,” “social class,” “sluttiness,” and “height.” If it were a weaker game, Ladykiller in a Bind would very easily get lost in the cross-hair of these labels, as an apparent representative for entire communities ranging from LGBTQ to BDSM. Luckily, the game navigates players beyond the terms, rules, and play of sexual orientation, to instead anchor them in what lies behind the words: a human being.

You spend your days on the cruise interacting with various characters, participating in a “game” that reduces popularity to points (basically if social media was IRL). Before picking each scene, you are given all the information you might need about how the interaction might affect your score—potential points, versus potential suspicions raised about your true identity.

the pre-scripted nicknames harken back to a romantic fantasy

But as night falls over the ship, your options reduce to only two polarizing romantic relationships: a partner with whom you play the dominant, and another where you are the submissive. As dominant, you turn a red-haired computer geek running the technology behind the game into your pet. She’s all sweetness and zero sluttiness, but boy do you make her question those two core characteristics. “The Hacker,” AKA “The Stalker,” has been crushing on you for a very long time and, lucky for her, you’re the type who likes to watch an overexcited submissive squirm and plead for you. One night with The Hacker awards you three votes—that is, if you’re a player who cares about winning the game. Other players can opt into a different route, foregoing the potential points in order to play with the dominant character. “The Princess,” (AKA “The Beauty” to your Beast), on the other hand, is a sadistic ruler who luxuriates in the tears of the victims she leaves tied up and wanting. She loves hearing you lose control, until you submit to every form of physical torture she desires just to earn her touch. Being the plaything of an all-powerful Princess has its perks, too, like how she can wave away people’s suspicions about you with a simple text message, giving you a clean slate in the morning.

Yet, for every sexual victory Ladykiller in a Bind pulls over you, it has a corresponding medicine to feed you. The opening screen coldly declares that, “All power exchange must be negotiated: That is to say, there’s nothing more important than clearly communicating your desire and limits in advance, without either party feeling uncomfortable or pressured.” Which is a very boring, unfeeling way of telling you about the game’s most incredible accomplishments. Ladykiller is a game with the guts to stare you straight in the eye, a small smirk playing on the corner of its lips, to ask plainly: what do you like? It recontextualizes the word consent, which is so rarely discussed outside the question of its devastating violation. Because consent is sexy in Ladykiller in a Bind, and not in that faux, campaign slogan kind of way.

In the two central relationships between The Hacker and The Princess, every word exchanged is about desires and limits; and it’s hot. The most titillating parts show nothing more and nothing less than two people consenting, telling each other what they want with an unwavering honesty and understanding. It’s a real shame, because the game does such a good job of tackling consent from a sideways angle—only to greet players with a loading screen with the game’s most boring and ineffective sentences. Most conversations about consent treat it like a ticking time bomb, with the words “negotiated” and “party” inspiring the desire to put on a business suit rather than undress and lay yourself bare. But rather than treat consent like a ginger, precarious hassle, Ladykiller shows it for what it truly is: good sex.

At its best, the game gives players agency and rules and lets them find themselves within those constraints. Devoid of expectations from its audiences (and constituents), Ladykiller gives itself over to you, all nakedness and beauty. But at its worst, it’s a game about consent, feminism, and LGBTQ issues, playing lip service to concepts that others have already turned into a mindless chant inside your head. On rare occasions, it reaches for the soapbox in a way that undermines its implicit lessons. “This doesn’t have to follow some stupid script where we start making out and end with penetrative sex as a forgone conclusion,” you say to The Hacker, following the script with foregone conclusions that you were given. Because the first thing that springs to your mouth in the middle of a heated bedroom encounter would, of course, be the dictionary definition of consensual sex.

the national anthem for sluts everywhere

For the most part, Ladykiller in a Bind dares to be unapologetically itself rather than a game made for any one set of people. You may be tempted, like me, to dismiss the game as simply, “not for you,” because you are either cis or not into BDSM. That assumption in itself warrants serious introspection, and Ladykiller isn’t shy about helping you confront it. The game oozes a magnetic confidence, from its sound design to its narrative tone—which is at once playful and intelligent. The game’s sheer existence as the story of a sex-crazed girl who loves manipulating people is enough to make it the national anthem for sluts everywhere. Like Amazon’s recent BBC expat, Fleabag, it brings visibility to the oft fetishized yet hardly ever genuinely explored story of a woman who thinks she can fuck away all her problems. Sex isn’t so much what makes the protagonist sexy, but rather what’s most terrifying and beastly about her—and also so very human.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Ladykiller in a Bind dares to ask “what are you into?” appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers