Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 36

October 26, 2016

DUSK is the grubby circus act a ’90s-style shooter should be

DUSK is an intentional throwback. It’s a game that deliberately, lovingly evokes the running, gunning, and no-reload bullet-dispensing of ‘90s shooters like Quake (1996), Blood (1997), and DOOM (1993). As with most exercises in nostalgia, it’s also pretty off-putting at first. Why make another Quake when right this instant Quake is available to play, as good as it ever was? Why roll around in the past when the future is always so much more exciting?

But give DUSK a chance and it makes an argument for itself. In the first moments of its preview version, a trio of burly, flannel-clad guys with burlap sacks over their heads and chainsaws in their meaty paws advance on the player. A disembodied voice croaks “kill the intruder” and a dim, dungeon-like room becomes a gladiator ring where the player—a voiceless, faceless pair of nasty sharp sickles—speeds around the arena like a trapped race car, showing off just how fast and bent on murder she really is. The look is standard: a flat, filthy lo-fi revival of early 3D. And the sound effects are a bit too dry to bring the necessary moisture that enlivens such a nasty setting. But the rhythm of the fight prevails.

Moments later, free of an initial set of hallways, that same character has become an ever-expanding collection of guns who zips around the borders of a cornfield and the exterior of an old farmhouse, or loads into the industrial maze of an endless “horde” mode, slaughtering to the tempo of the 16th-note ride cymbals propelling a delightful butt-rock backing track. The player is an acrobatic killer and her arsenal is strong. Gas-masked soldiers do little barrel rolls as they die, eager to ham up their expiration for the player’s benefit. Each enemy emits little clouds of pixelated red paint when an attack hits home. Everything about the game is familiar enough to conjure the past, but DUSK has a distinct enough personality that it approaches its own identity all the same.

flips the guns around like a show-off drummer twirling sticks

And the guns are pretty good, if not quite right yet. DUSK’s pistol is a pea shooter whose fire patters instead of bangs. But once you pick up a second pistol, Chow Yun-fat-ing the enemies with twice the bullets, that same patter double-times into a satisfyingly insistent, regular beat against enemy bodies. The double-barreled shotgun blast is tinny when a full-bodied explosion is called for, but, surprisingly, switching to its single barreled little sister amps the bass, properly coupling the flinging backward of almost-corpses with the sonic oomph the movement deserves. A grenade launcher barfs projectiles from its jaws like a steel cat spitting hot iron hairballs, though the enemies blow apart with a surprising lack of aural ceremony (the ungrateful jerks).

A few of the current weapons—the crossbow and that double barreled shotgun in particular—feel like they need a bit more time in the oven, but DUSK is on the right track. It knows that a nostalgia shooter shouldn’t have a reload button, but is unique enough to understand that the player will press the “R” key anyway and rewards her with a little animation where the characters flips the guns around like a show-off drummer twirling sticks between fills. It’s a small touch, but hopefully indicative of DUSK’s direction. The seemingly minor details of a shooter so obviously obsessed with the act of shooting make all the difference.

If DUSK makes release with enough of these touches studded throughout, it’ll be something more than a recreation—and a reason to play its brand of old-shooter instead of the many ‘90s games to which it owes so much.

You can find out more about DUSK on its Steam page. It’s due out in 2017.

The post DUSK is the grubby circus act a ’90s-style shooter should be appeared first on Kill Screen.

You can finally get your paws on Night in the Woods this January

I’ve spent many months thinking about what my New Year’s Resolution will be as we transition into 2017, and I’ve decided: I’ll live life more like a cat. I’ll prowl human legs, mewling for tuna, and scratch leather sofas to prime my claws. But, mostly, I’ll chill out and do a whole lot more sleeping. This ambition of mine has just been made much easier with the news that, after three years of work, Night in the Woods is coming out on January 10th 2017 for Windows, Mac, Linux, and PlayStation 4.

In it, you play as Mae Borowksi as she returns home to Possum Springs, looking to “resume her previous life of aimless hanging out and petty crimes.” Mae is a cat. But not in the Catlateral Damage sense—in which you wreck shit from the perspective of an enraged house cat—rather, Mae is much more human; a typical post-teen, small-town resident in search of a path in life. Her friends are similarly anthropomorphic (a bear, a fox, a croc), but they’re more grown up than when she left Possum Springs, so in the game we’ll see her trying to get used to that.

“strange things start to happen”

As you might gather, Night in the Woods focuses on dialogue and storytelling than most other things. This is something that can be gleaned by playing Lost Constellation, made by the same team and presented last year as a “folktale from the world of Night in the Woods.” Sure, Night in the Woods will have “jumping between buildings, feeding rats, and smashing lightbulbs behind the convenience store,” but it’s a game that wants to be identified more for the thoughts it provokes than the verbs it uses.

But that’s not all. The title, Night in the Woods, refers to a stranger conspiracy that’ll unravel as the game does. We’re told that “strange things start to happen,” a tease that culminates in there being something to discover in the woods. So while life and melancholy brushes up against Mae’s fur, she and her friends will also be faced with the prospective of the supernatural—whether in their imagination or not—as they chase their curiosities between the trees.

At least, that seems to be one version of the game’s events. The news released today adds that you have some choice as to how you have Mae spend her time in Possum Springs, and that determines what things she ends up doing and who she meets. You’ll have to play through the game more than once to see everything.

That should be enough intrigue for now. A new trailer for Night in the Woods is apparently on its way between now and the game’s arrival, so look out for that. I just have one more question: why does that owl in the announcement image above have antlers?

You can find out more about Night in the Woods over on its website.

The post You can finally get your paws on Night in the Woods this January appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Japanese folktales that inspired Miyamori

Last summer, we stumbled across Miyamori, a lovely folktale-infused videogame about Japanese mythology in the Tōhoku countryside. The game follows a Japanese woman named Suzume as she attempts to find her missing brother. Joined by the shrine guardian fox Izuna—who is looking for her partner Gedo—the game follows Suzume and Izuna’s journey through the countryside to find their missing halves.

Since then, Miyamori has been seen in action for the first time to due to the arrival of its debut trailer, released earlier this month. Hence, it seems as good a time as any to talk to Joshua Hurd, one of the game’s creators, to find out more about his work’s inspirations.

“each story is a brief vignette of some strange event”

“[T]here’s a lot of ground to cover here, but there is one theme common to many Japanese folktales—liminality,” Hurd told me. “By that I mean a threshold between two spaces. That might be the boundary between the human and spirit worlds, or it could be the brief time between sunset and nightfall. It could even be a mysterious outsider figure. In any case, the unique position between two worlds can be a powerful force of change, but it can also be dangerous.”

Hurd also feels a deep connection to works such as The Legends of Tono (1910) and the poetry of Miyazawa Kenji. While these stories deal with massively different themes, Hurd decided to bring these influences together to create a fantastical countryside for players to explore.

“What I love about The Legends of Tono is that each story is a brief vignette of some strange event,” he said. “You can read it one way, as pure fiction, or you can try and fill in the backstory of what might have actually happened to inspire the story. To me that’s the interesting part, knowing that someone, somewhere, witnessed something completely bizarre and inexplicable and then let their imagination run wild to try and make sense of it.”

Kenji’s poetry, meanwhile, mirrors Miyamori’s focus on Japan’s northern countryside. Referencing such children’s stories as The Night of Taneyamagahara and The Restaurant of Many Orders, Hurd argues that Kenji’s work inspired the game’s atmosphere. “I know Suzume would be a fan of his stories,” he said.

With Miyamori is still a ways off, the plan is to get a playable build out in the spring. Hurd said he can’t wait to hear what stories and experiences players will share once they get their hands on the game. “Folktales aren’t meant to be handed down as a matter of fact—to stay alive they need a community that’s engaged with reinterpreting their meaning,” he said. And in its own way, Miyamori is looking to do just that.

You can find out more about Miyamori on its website.

The post The Japanese folktales that inspired Miyamori appeared first on Kill Screen.

Nicky Case’s newest game looks at how media shapes us

Two years ago, game designer Nicky Case was trying to process the events in Ferguson. Inspired by an image showing how camera framing can alter how a story is perceived, Case went about creating a game playing upon these notions. Though the initial post about the game went viral, Case admits they couldn’t find a way to extend the idea further and subsequently dropped it altogether.

Then, the summer of 2016 happened. From the shootings in Orlando and Dallas to Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, the summer was wrought with one tragedy after another. At around the same time, Case was working with PBS Frontline as a Knight-Mozilla OpenNews fellow (an initiative implanting technologists within news organizations). While trying to cope with the frustrations and anxieties brought on by the summer’s events, Case started thinking about the role of media and the game they abandoned years before.

After seeing the effects of media coverage on the political landscape (like the continued coverage of Trump), Case saw the media as part of a self-fulfilling loop fueling polarization. “The media right now pays attention to what happens quickly rather than what happens slowly. [But] quick things tends to be really bad while good things happen slowly,” explained Case. “If we only show conflict, that’s what we’ll get.”

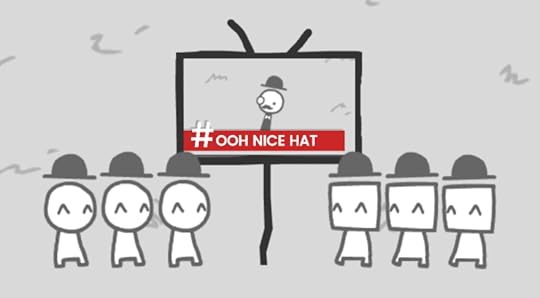

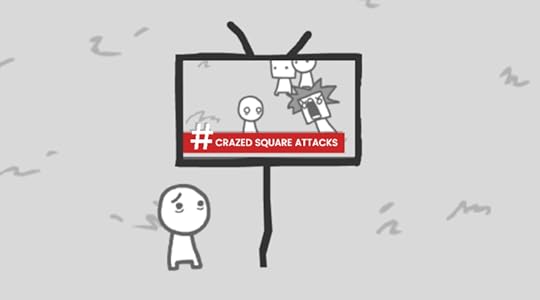

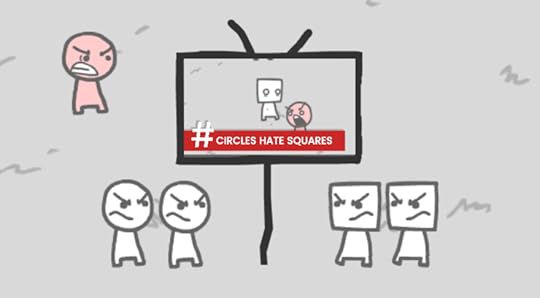

Case explores this with their latest game, We Become What We Behold. Acting as a sort of newsroom simulator, the game begins with an empty TV screen with folks milling around it. Playing as a photographer, you try to capture interesting scenes whether it be of folks with hats or a couple in love. Whatever you choose to capture becomes the headline (shown on the TV screen) which then influences what people do (i.e. taking a photo of that cool guy with a hat begets a hat trend). The beauty of the game though lies in the way it lulls you into thinking you’ve got it all figured out. But as soon as you get comfortable, the headlines start influencing things beyond the latest fashion trend, namely people’s opinions of each other.

For Case, the seeds of polarization begins here: “Even if everyone in the beginning starts out okay (with only a few wackos), by constantly focusing on what is the extreme rather than what’s normal, you shift what is normal to the extreme. [That’s] one important mechanism that drives political polarization. [You have] these echo chambers where the most extreme members are disproportionately represented. Then, over time, society splits.”

“It’s not just the newscaster’s fault, it’s also us”

As in a lot of Case’s previous works, We Become What We Behold distills a part of the human condition within a systems perspective showing its flaws, quirks, and uncomfortable truths. At one point, in a very meta way, while you might have an inkling where the story will go, it’s hard to stop because as Case points out, “everyone wants to watch a train wreck (but nobody wants to watch a train get repaired).” The game may start out as a seemingly inconsequential and humorous newsroom simulator, but it quickly morphs into a game that jars you into considering how we shape the media and how it shapes us.

Case is quick to emphasize though that they didn’t want to place the blame squarely on the media for negatively influencing us. “It’s not just the newscaster’s fault, it’s also us (the audience). If you try to take a picture of the peaceful protestors, you can do that, but no one is going to watch it and it’s our fault,” said Case. “I didn’t want to just blame one side [which tends to be the case] with a linear cause and effect model …With a loop, the cause becomes the effect and the effect becomes the cause.”

We Become What We Behold is free to play on itch.io .

The post Nicky Case’s newest game looks at how media shapes us appeared first on Kill Screen.

Playing with the Trickster

“They are the lords of in-between. A trickster does not live near the hearth; he does not live in the halls of justice, the soldier’s tent, the shaman’s hut, the monastery. He passes through each of these when there is a moment of silence, and he enlivens each with mischief, but he is not their guiding spirit. He is the spirit of the doorway leading out, and of the crossroad at the edge of town.” – Lewis Hyde

///

Adam Jensen is a serious man. He has no time to spare; a helicopter is waiting for him as we speak. So what does he think he’s doing, breaking into a bank in Prague, causing all sorts of mischief and mayhem, for no other reason than his own personal amusement?

Or, rather, my amusement. Infiltrating and unravelling the many security layers of that building, becoming the ghost in the puzzle-box machine, may be the most enjoyable experience I had while playing Deus Ex: Mankind Divided. And yet, this diversion also had a disruptive quality. I turned Adam Jensen against himself, and his bleak world of oppression and conspiracies. For a few hours, the body of that brooding cyber-soldier was hacked and usurped by a mischievous trickster spirit that delighted in turning this dystopian cyberpunk world into his personal playground.

Robbing the bank blind is not a turning against the game’s design, however; after all, its creators provide you with both the means and the opportunity to perform this act of transgression. But the motive is provided by the player alone, and this is where a kind of unwitting subversion takes hold. This motive to use the tools at one’s disposal not just to overcome obstacles and progress, but to create entertaining and surprising situations, is always present in Mankind Divided. But the bank is an unabashed monument to that kind of self-indulgent urge, and embracing it with matching shamelessness will break the illusion of this virtual world and reveal its artificiality. Depending on your outlook, this disenchantment might seem like a threatening loss of order, or a liberating invigoration.

In his book Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art (1998), cultural critic Lewis Hyde re-examines one of the most persistently fascinating figures of our archetypal imagination: the trickster. They have many faces, many guises: Hermes, Loki, Coyote, Krishna, Eshu … it goes on. Based on close readings of trickster stories from around the world, Hyde describes a shifty figure of the doorway and the road, nestling in the margins and boundaries of communities, muddling distinctions through transgressions and mischief. The trickster is a deeply ambiguous figure. Driven by hunger, they’re both foolish prey falling for the poisoned meat, and a masterful setter of traps, a manipulator. Shameless, the trickster lies for their own profit and speaks forbidden truths by breaking taboos. After the trickster has come and gone, having slipped through pores in the boundaries erected to protect order, what was perceived as natural, eternal, and sacred before now seems arbitrary, contradictory, disenchanted.

a threatening loss of order, or a liberating invigoration

The trickster isn’t merely a destroyer, then, but also a creator and culture hero. Their mischief can be dangerous, but it’s also essential to the health of social systems. If the status quo has become sterile and inflexible, the trickster’s antics oil its joints, make it fertile and limber again. They have their own brand of transgressive creativity that embraces the accidental, the peripheral, the noise—rather than the signal—and thereby leads to truly new things that would have been unimaginable in a self-contained, self-perpetuating system that is able only to draw from itself. Hyde is especially interested in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, which recounts the mischief of baby Hermes and his path from the margins to Mount Olympus. Hermes sneaks out of his mother’s cave, creates the first lyre out of a tortoise, then steals Apollo’s cattle and brazenly lies to Apollo when confronted. He is brought before Zeus for his transgressions, but instead of being judged, he charms and sings his way into a world order that previously excluded him, and his intrusion first unravels and then rearranges this order.

Hyde also looks for aspects of the trickster outside of myths—for their mischievous creativity at work in the world around us. He sees it, for example, in the compositions of John Cage that embrace accident and noise, in the writings of Maxine Hong Kingston whose ‘shameless’ speaking breaks taboos, or the struggles of the “free slave” Frederick Douglass who exposed the self-contradictions in a racist system. At the same time, Hyde worries about the modern, post-polytheistic world’s lack of trickster figures. He asks: “What remains? What are the modern forms by which order deals with its own exclusions? Where is the dirt-work of democratic mass society? Where has trickster’s spirit settled?”

Of all the places the trickster’s spirit may settle, videogames seem to me the most intriguing. Here’s a chance not merely to tell or be told about a trickster’s exploits, not merely to perform or witness their brand of creativity, but to enter an embodied trickster figure, and play with the rules of a system through this body. The mere act of adopting a new face, of inhabiting an avatar, is deeply suggestive of the trickster: the player casually slips out of her own skin, seamlessly entering a new guise. She transgresses and upsets the boundaries delineated by screen and interface: between the real and the virtual, the physical and the imaginary, the self and the other.

There’s one type of game that seems especially relevant here: the stealth game. Even a cursory glance at the bodies these games ask us to slip on reveals their closeness to the shifty, ambiguous trickster. Snake, aka Big Boss, from the Metal Gear Solid series is a mercenary, operating in-between nations and ideologies, fighting for his own interests. Agent 47 from Hitman is an instrument of murder as much as he is a human being. Corvo from Dishonored (2012) is traitor and loyalist at the same time. And Adam Jensen is a double agent in the latest part of the Deus Ex series, negotiating in a space between Interpol and a hacker collective. All of them have to break the rules of the systems they inhabit or break into, to slip through barriers, ideally through subterfuge and deception rather than brute force. All of them are essentially amoral figures: rarely unambiguously evil, but always at least toying with the dark grey areas of ethical conduct.

The trickster, according to Hyde, is a creature interacting with actual or metaphorical traps: setting, breaking, subverting, or falling into them. Blinded by hunger or lust, the naïve trickster is unable to recognize the danger. Similarly, the stealth game tantalizes and beckons the player with goals, rewards, opportunities, ready to spring the trap set by the designers and the procedures of the program. It’s the most obvious pathway in Deus Ex; an assassination target walking right in front of you in Hitman; an elite soldier just asking to be abducted in Metal Gear Solid V (2015). The naïve player will jump at the poisoned ‘opportunity’ as soon as it presents itself.

The trickster is a paradox

But the trickster may learn from previous mistakes. And the experienced stealth player will refuse the urge for immediate gratification in the knowledge that the eventual reward will be the more satisfying. She’ll study the traps carefully, and knowing their mechanisms, she’ll be able to get at the ‘meat’ without springing the trap. Or even better, she may subvert it, turn it against the trappers. Adam Jensen can hack security systems so they’ll target his enemies. Snake may spring an enemy’s trap with a decoy, allowing him to sneak past or flank distracted guards. Of course, setting and manipulating traps is a tricky business, and just as the guard’s traps may turn against them, the unwary player may easily fall into her own pit: Agent 47, lurking in some broom closet, waiting for his victim to appear, only to realize too late that some embarrassing mistake’s been made and there’s nowhere to go, nowhere to hide. Snake tripping over his own sleeping gas mine in a moment of humiliating slap-stick idiocy, ruining a carefully laid-out plan. The trickster is a paradox living on the boundaries between opposites. They are both hunter and hunted, the ingenious manipulator and the bumbling fool, the monster lurking in the shadows and the scared child hiding in the closet.

In some ways, Hyde points out, the trickster is the most foolish being of them all, since they have “no way of [their] own,” no instinctual response to a problem. Doom Guy’s way is to shoot whatever moves in front of his gun. Super Mario’s way is to jump over obstacles. What is the way of Snake, of Agent 47? They have easily definable goals, but how do they get there? ‘Sneaking’ doesn’t exhaust it at all, as it often encompasses a plethora of possible actions and strategies. The way of the one with no way, it turns out, is to have countless ways. Agent 47 doesn’t have an M.O. In fact, the challenge system of this year’s Hitman is all about exploring dozens and dozens of potential murder strategies rather than perfecting a single one. By having many ways, the trickster circumvents what Hyde calls the “trap of instinct.” It’s hard to catch a being whose moves cannot be predicted. Even their appearances are fluent: Snake is a master of camouflage and tactical cardboard box deployment, Corvo can slip into any living thing he sees, and Agent 47 blends into any crowd simply by dressing smartly. After all, the trickster “can encrypt [their] own image, distort it, cover it up” and is “known for changing [their] skin.” Conversely, the trickster exploits this trap of instinct to get what they want. How easy it would be to trick Mario or Doom Guy with their single-minded ways. Put some encouraging coins over a wide abyss and the plumber falls to his death. Steal away the ammunition in a Doom level and the space marine will be at his wit’s end. A stealth player’s opponents follow predictable rules and are prone to fall into traps of instinct.

There’s a powerful kind of creativity to the trickster’s hijinks, Hyde suggests, and by extension to the player’s actions. If conventional creativity is seen as a process that reveals what is orderly and essential in the world, then the trickster’s creativity reveals the noise and accidents of the cosmos. The trickster improvises: their plans and actions are as fluent as themselves, and they embrace contingency, incorporating it into their work. Stealth games are simulations first and foremost, and therefore highly emergent. The player may easily predict the behavior of a single guard, but emergent complexity will still take her by surprise. Such systems are proficient at creating ‘accidents’, i.e. unexpected situations that neither player nor designer could have planned or foreseen, through the interaction of their many moving parts. Whether the player gets caught in the chaotic interaction between guards and swarms of murderous rats in Dishonored, or is flushed out of her hiding place by the unexpected arrival of a truck in Metal Gear Solid V, emergent systems will always create surprises. These accidents will disrupt the player’s plans, but they may also provide opportunities to seize, gaps to slip through. Another result of emergent complexity are frequent glitches, which range from the grenade-enabled wall climbing of the original Deus Ex, to brainwashing enemies into becoming your buddies in Dishonored, to taking your horse along for a ride in Metal Gear Solid V. Glitches also highlight how the creative player can exploit opportunities that lie outside a game’s design proper, using hiccups in physics or AI simulation to create their own amusement or advantages. The player who recognizes the ‘meaning’ of the accidental and works with it behaves like a trickster. Whenever a player reloads the game since her plan didn’t work out as intended, she tries to restrain trickster creativity.

the relationship between the serious and the frivolous

Acts of trickster creativity are always disruptive within the system they are performed. This is equally true of a player’s misbehavior in stealth games. Metal Gear Solid V has been criticized for its silliness, which clashes with the game’s serious topics of war, child soldiers, and genocide. It’s a valid point, but it also neatly illustrates the game’s disruptions. Every time the player hides under a cardboard box or fulton-extracts a sheep in a war zone, she’s effectively challenging how we think about the relationship between the serious and the frivolous in the first place. Playful silliness and horrors exist side by side. Something similar is true for Mankind Divided, where the player’s transgressions—breaking into apartments, robbing the bank—seem at odds with its themes of oppression. But whereas these disruptions lead to a flawed-but-interesting provocation in Metal Gear Solid V, they merely undermine the whole fiction of its world in Mankind Divided.

Dishonored tries to ‘tame’ trickster creativity by distinguishing between what Hyde calls the wild vs. the domesticated trickster—the former destroying the status quo, the latter restoring it at the end. If the player kills too many people, chaos rises and the game world becomes apocalyptic. But the distinction between wild and domesticated is subverted as soon as the player starts to consciously play with the chaos system, e.g. by starting to sneak through a high chaos world without harming anyone.

Hitman dispenses with the flimsy moral choices of these other games. You don’t get to choose whether to murder your target, only how you do it. Agent 47 isn’t at all interested in questions of right and wrong; he is perhaps the most amoral among stealth protagonists. As a result, Hitman confuses our moral compass, and replaces it with a completely different code of conduct: the ethos of the contract killer. The ‘good’ killer, as is reflected in the rating system, murders only their targets, doesn’t make a mess, leaves quickly and undiscovered. But even this subversion will be subverted in turn, because the player is enabled and even encouraged by the game to cause havoc and kill her targets in inefficient, ridiculous manners, thereby breaking the contract killer’s rules. Killing a man via exploding golf ball and calmly standing in the middle of the unfolding chaos is a similar thrill as hijacking a tank in Metal Gear Solid V and waltzing right through what was supposed to be a stealth mission. These are gleefully self-indulgent acts that transgress the cardinal mandate of the stealth genre itself: Be Subtle. That these games allow for such rule breaking is sometimes seen as a concession to mainstream tastes, but I’d argue that it is really a concession to the trickster spirit. The rules are there to be broken.

Still, these games seem to consider some of their boundaries sacrosanct, not to be transgressed. Seemingly being anxious about the trickster they themselves invited, they impose structures on the player designed to keep the more troubling aspects of the trickster in check. I’m specifically talking about goals, motives, and framing stories. Metal Gear Solid V and Dishonored use revenge stories to justify their players’ behavior. In Mankind Divided, the player fights conspiracies and terrorism. Even Hitman, despite its amorality, often pits Agent 47 against people who are markedly more evil than he is. No matter how much you transgress, these games tell the player, you are always already justified.

Of course, the trickster can never really be bound, but the damage is already done: by trying to tame them, these games hamstring themselves and their potential to say something meaningful about the world, its communities, and the conceptual boundaries they use to make sense of it. Hyde writes that, instead of futilely attempting to restrict the trickster, “it would be better to learn to play with [them], better especially to develop styles (cultural, spiritual, artistic) that allow some commerce with accident, and some acceptance of the changes contingency will always engender.” As said before, videogames are a strong contender for cultivating these styles of negotiating with trickster creativity. Unfortunately, modern mainstream stealth games seem hesitant to go the full distance. I’d love to see future stealth games that embrace the trickster spirit and their players’ transgressive creativity more fully, that challenge our seemingly natural understanding of creative works or the world more coherently.

The post Playing with the Trickster appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 25, 2016

Framed 2 will bring more comic-panel shuffling to videogames

Acclaimed noir puzzle game Framed was touted for its ingenuity, taking elements of comic-book panel design and implementing them into its videogame format. Much of the story, then, existed outside of Framed‘s panels, allowing players to fill in the blanks. Lead designer Joshua Boggs attributes this idea to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics (1993): “The level of detail and investigation [McCloud] does in Understanding Comics was absolutely pivotal for Framed, and still is to this day.”

Announced last week, Framed 2 will be released in early 2017, acting as a prequel to the first game. Panel switching is an important element in Framed 2, too, but it won’t be exactly the same. “For Framed 2, we’ve taken a clearer and more deliberate approach to framing the narrative,” Boggs said. Art director Ollie Browne continued: “The learning process of the first game allowed us to really stretch ourselves without worrying that we would run into difficult technical or design problems like we often did with the first game.”

Much of the story existed outside of Framed’s panels

Framed was first designed using scraps of paper to figure out the actual puzzles. In Framed 2, Loveshack took this to another level: the team designed almost the entire game on paper, first, before actually getting started on the technical side. “This way, we could play the entire game as a ‘mock-up’ and make adjustments before committing to the content and starting very time-consuming animation, art, and music creation,” Browne said.

Those attending the Melbourne International Games weeks activities set for October 31 through November 6 will be able to experience Framed 2′s new location and new story a bit early.

Loveshack Entertainment’s Framed 2 is slated for early 2014. See the Loveshack Entertainment website for more information.

The post Framed 2 will bring more comic-panel shuffling to videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

Videogames could do a lot more with the Venetian mask

It was December 31, 1958. In Rapture, the underwater city in BioShock (2007), the most affluent residents gathered at a masquerade ball in the Kashmir Restaurant for a night of dinner and dance. However, a sudden explosion marked the end of the celebration—and the beginning of a ceaseless civil war.

People started abusing a wonder drug known as ADAM out of fear and desperation which, in exchange for superhuman abilities, caused severe disfigurement. To hide their facial deformities, the denizens of Rapture decided that they would not be seen without the Venetian masks from the New Year’s Eve party.

///

The Venetian masks in BioShock are symbolic of Rapture’s descent into depravity. But they are also a throwback to the origin of the Venetian mask, which is steeped in excessiveness—caused and compounded by its promise of anonymity. A particularly notorious instance was when Elizabeth Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston, dressed up as a bare-breasted Greek goddess, Iphigenia, in a 1749 masked ball. Even though other guests weren’t exactly modestly dressed, this still caused one guest to exclaim, “…ye high priest might easily inspect ye entrails of ye victim.” As if in defiance, Elizabeth also released an inordinate amount of gas, farting and belching while gorging on mountains of food.

They served a simple yet desirable purpose

These masks may be the most recognizable icons of masquerade balls today, but they didn’t always support this association, having only been introduced to Italy in the 16th century, while their usage can be traced a little further into the past. In the 15th century, masquerade balls were first held in Europe to celebrate the marriages and coronations of monarchs, as well as other royal processions. They were also characterized by exquisitely colorful masks and equally elaborate costumes, and were audacious and decadent affairs. Think less high society, more circus performance.

One notable ball is the tragic “Bal des Ardents” in 1393, organized by Isabeau of Bavaria, the Queen of France. To commemorate the marriage of her lady-in-waiting, Isabeau’s husband, King Charles VI, and five of his courtiers were dressed as wild men—shaggy mythical woodland beings with a humanoid shape—and wore masks, while linen costumes, soaked with resin and lined with flax, were sewn straight onto their bodies. They danced vulgarly to the discordant music of cymbals, rusty pots and pans, all in jolly good fun until Charles’s brother Louis, Duke of Orleans, drunkenly barged into the ball with a lit torch and accidentally set fire to a dancer’s leg. Like forest flames in summer, the fire ravaged the highly flammable dancers, causing the death of four courtiers.

William Hogarth [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

When the balls finally made their way to Venice, they started out as ballroom dances exclusive to the wealthy, but soon spread like wildfire (excuse the pun) among the bourgeois society. Their doors then swung open to anyone who could afford a ticket. They became almost synonymous with the Carnival of Venice—another festival which began in 1162 as a celebration of Venice’s victory against the Patriach of Aquileia, Ulrico di Treven—and with that, masquerade balls in Venice were even more celebrated for their Venetian masks.

With the advent of masquerade balls and the Carnival of Venice’s growing popularity, Venetian masks were propelled even more into the mainstream, although they were already in use as far back as 1268. Thanks to the valiant efforts of mischief makers, the Great Council of Venice had to decree a ban on throwing scented eggs while masked (which implies tossing eggs with your face exposed might have been legal). Nonetheless, by the 18th century, the masks were part of the daily dresses of many Venetians, and were often used outside of festivities. Nobles welcomed their foreign emissaries with a mask on, while married couples met for meals at inns, cafes, and hostels while masked.

It’s easy to see why Venetian masks were so popular. They served a simple yet desirable purpose—anonymity—and like present-day internet trolls, this allowed mayhems to fester, from sexual promiscuity to spikes in crime. This led to a country-wide ban of the masks outside of carnivals was enacted in 1797, following the demise of the Republic of Venice due to Napoleon’s conquest, which caused the masks to fall out of popularity. Gradually, even the carnivals faded into obscurity, and were banned by Mussolini in the 1930s. Only in 1979 did the Carnival of Venice make a triumphant return, courtesy of the Italian government, who wanted to encourage tourism and boost the country’s economy by showcasing the country’s rich Venetian culture.

///

The panoramic history of the Venetian mask and its festivities should be fertile ground for videogame narratives. But the setting has been curiously underexplored so far, save for an appearance in a few games such as BioShock and Assassin’s Creed II (2009). Even then, their realization inside these games feels skin deep—they serve as little more than set dressing. This is especially obvious in the case of Assassin’s Creed II, which required the assassin Ezio to eliminate one of his targets, the Venetian Doge Marco Barbarigo, in the midst of the Carnival of Venice. To my astonishment, he simply donned a laughable disguise—a full-faced Venetian mask known as the Bauta—to get away with his murder, despite still being dressed in the distinctive garb of the Assassin Order.

these masks require a level of proficiency

That is why, during my conversation with Ian Gregory, creative director and co-founder of the Singapore-based Witching Hour Studios, my interest was piqued when he talked about how Venice had left a mark on him, and how it influenced the distinctly Venetian setting found in the studio’s latest title, Masquerada: Songs and Shadows.

“I went on a backpacking trip right after the mandatory two-year national service [in Singapore], and one of the places I remembered distinctly and thoroughly enjoyed myself at was Venice,” he recalled. “While the masquerade masks were definitely an inspiration for the game, the picturesque look of Masquerada stemmed from an experience I had with some friends; we bought a bunch of wooden toy swords on sale, and engaged in a mock, drunken sword fight along the canals.”

This experience set the stage for the war-stricken but scenic city of Ombre, where Masquerada is set. The protagonist Cicero Gavar, who returns from exile to investigate the kidnapping of a diplomat, is outfitted with a magical Venetian mask—an article that many prominent characters in the game own as well. Referred to as Mascherines in the game, these allow anyone to conjure magic.

However, these masks require a level of proficiency to wield with deadly effect—a narrative flourish introduced by the studio’s lead writer, Nicholas Chan. “His writing added a layer of depth to Masquerada. For instance, mastering the magics and using the Mascherine with finesse required a keen understanding of media—fields that are related to the arts, such as drawing, singing, playing musical instruments, and dancing,” Gregory elaborated. This harkens back to masquerade balls and the Carnival of Venice, which have roots extending far into music and the arts; masquerade balls had long been renowned for their dances, while the modern Carnival of Venice is home to many baroque-styled masks and costumes. With a note of pride in his voice, Gregory remarked that Chan had masterfully brought these Venetian elements together, successfully weaving Masquerada’s narrative into a coherent whole.

Not everyone is privy to the use of the Mascherines though, as they are rare artefacts within the Masquerada universe; once their owners die, the masks will turn to dust—and there is no way to reverse this process. “Since no one in Masquerada knows how to craft a new mask, it becomes a constantly diminishing commodity that only the very rich can own,” Gregory said. He also pointed out that these masks are only offered to those in the highest echelon of society, because they hold the promise of an undying legacy—another scarce commodity in tremendous demand.

This idea of legacy, or the desire to be remembered even after death, is so sought after because of the city’s magical nature. Specifically, the society’s godlike ability to manipulate and bend the most rudimentary elements of nature—fire, water, earth, and air—to its liking has rendered any notion of religion or an afterlife unnecessary. “ When people pass away, there aren’t any records of their life and memories,” Gregory mused. However, when a mask owner dies, a song will be written for the deceased and kept in a room called the Hall of Songs. Those without a mask—well, they simply won’t have a legacy.”

There is no wrong way to wear a mask

The Venetian masks of centuries past possessed no such magical properties; they were simply mass-produced goods that were affordable and modestly decorated. Yet, they were significant because of their capacity to break down social classes. With their identities hidden, citizens from the various strata of society could mingle with one another freely without fear of prejudice. On the other hand, the Mascherines in Masquerada are a symbol of wealth and power. They might have been at the root of Ombre’s ongoing civil war, and are perhaps instrumental in widening the power gap between the rich and the subjugated.

These differences may seem antithetical, but one trait both masks share is their capacity to satisfy a deep need for control. The behavior of the Maskrunners in Masquerada exemplifies this: to fuel a rebel movement within the city, they take to stealing the Mascherines—relics they would never have the means to acquire otherwise—in order to wrestle back control and power to their faction. Likewise, the anonymity in wearing the Venetian masks during Venice’s earliest days emboldened its citizens, offering them the liberty to do as they please with little regards to the hierarchical structure of its society.

Unsurprisingly, the allure of anonymity that gave rise to the promiscuity and general state of debauchery in Venice soon spread to the rest of mainland Europe in the 18th century, as masquerade balls become more commonplace. It was during 1792 that Gustav III, the King of Sweden, was assassinated in one such masquerade ball. Much maligned for his enactment of the Union and Security Act in 1789, which allowed him to declare war and make peace without consulting his cabinet, he had many political enemies. One of them was nobleman Jacob Johan Anckarström, who shot him with a pistol while donned in a black mask. Gustav III soon died from his wounds.

Similarly, the prologue of Masquerada places the player in the shoes of Cyrus Gaver, who incidentally, is the younger brother of the protagonist Cicero and the leader of the Maskrunners. Like Anckarström, Cyrus is out for blood—specifically, the blood of Ombre’s ruler, Avestus Aliarme. He was heavily guarded, of course, and Cyrus and his crew had to fight past hordes of guards to get to him. These fights aren’t bloodbaths, however; on the contrary, they are flourished with splashes of color and the elegance of classical music, much like the courtly dances of masquerade balls.

Plus, a contentious issue that continues to plague both historians and the citizens of Ombre was the origin of their masks, and how they came to be of use. Aside from the eggs-tossing legislation in Venetian history, little was known of how Venetian masks came to be before this incident. Did the first Venetian to put on a mask become a subject of ridicule from the rest of the city? In the same vein, how were the Mascherines created in Masquerada? Eventually, both the Mascherines and real-life Venetian masks dwindled in numbers; the former due to the deaths of mask owners, and the latter due to a ban by the killjoy Mussolini.

///

The use of masks in videogames—not just Venetian—has seen widespread adoption, each carrying their own interpretation. “That’s the beauty of masks, because they are very symbolic items. There is no wrong way to wear a mask; it can either be used to hide one’s identity, or conversely, be used as an expression of identity,” said Gregory.

In the case of the Mascherines, we have a meticulously decorated facade that is unique to every character. Even when masked, telling them apart is a simple and obvious task. For instance, Cicero’s mask is an intricately designed blue and red one with gold trimmings, whereas a companion has one with a predominantly blue color palette. Conversely, the myriad animal masks in Dennaton Games’s Hotline Miami (2012) conceal protagonist and mass murderer Jacket’s identity—his true identity and name may never be known to anyone except the game’s creators.

As a game with a distinct Venetian backdrop, Masquerada—and its masks—have added a new chapter to the maturing field of modern videogames. Countless reinterpretations of medieval and World War II themes abound, but Masquerada offers a captivating and unique experience that is grounded in Venetian culture. Just like how Assassin’s Creed revived interest in European history, perhaps Masquerada can do the same.

The post Videogames could do a lot more with the Venetian mask appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen is looking for a new Editorial Director

Yesterday, Kill Screen‘s Editorial Director, Clayton Purdom, announced his departure in the only way he knows how. We’re sad to see him go. But that does mean we’re now looking to fill that gap he has left behind.

In short, we’re looking for someone who can steer the ship of all of Kill Screen‘s editorial properties going forward. Come make us awesome! That includes our print magazine, the Kill Screen website, and its sister sites, Versions and The Meta. They’ll also help to direct the events related to those three websites as well as any other creative projects the team dives towards. Another point on the list is working with the Director of Business Development to shape out the editorial business and make sure it continues to grow.

This is a full-time position, ideal for someone who lives in Los Angeles or is willing to relocate (but we are open to a remote worker too). Kill Screen is also interested in working with and hiring women, LGBTQ people, people of color, people with disabilities, and people with nontraditional educational backgrounds.

You can look up the full scope of what being an Editorial Director for us entails over on the Submittable post for the position.

///

Header image: The Chess Players by Lucas van Leyden, via Wikimedia

The post Kill Screen is looking for a new Editorial Director appeared first on Kill Screen.

Karma. Incarnation 1 doesn’t hold back on the psychedelia

In AuraLab’s Karma. Incarnation 1, I’m controlling Pip. Or rather, I’m directing Pip along his journey. Pip is a worm-like creature, but he wasn’t always that way. Once upon a time, he was merely a lost soul. After his lover gets captured by an elusive Unknown Evil, Pip ventures off alone into a surreal world to get her back. But then he’s reincarnated accidentally as a worm, not a dragon as originally planned. And now here we are, Pip and I, bargaining with a dancing creature to trade a flower lei for the snowflake-encrusted light bulb I need that’s hanging on his gold chain.

Meshes the vibrancy of psychedelia with the dreamlike nature of surrealism

This is familiar point-and-click adventure fare. Solving puzzles, navigating dialogue with characters (or in this case, animated wordless thought bubbles), and clicking my way through an environment. Except in Karma. Incarnation 1, the art style takes a turn for the bizarre. Meshing the vibrancy of psychedelia with the dreamlike nature of the 1920s art movement that birthed Salvador Dalí, Karma. Incarnation 1 implements an unmatched visual style that seamlessly couples the best of psychedelia and surrealism. The game’s backgrounds remain stationary, often eerie works of art in their own right. But Pip is lucked with the ability to see the world around him in a new light, to see the unseen. Or, rather, with a new hue of vibrant color.

Karma. Incarnation 1 is not merely an exercise in excellent art design. It also wrestles with the complexity of morality—where Pip can interact with the other creatures he comes across in a positive way, or in an inherently evil way. How Pip interacts with others changes both the outcome of the game and his own appearance. Unfortunately, the game doesn’t give many cues as to what’s the right way to act (which may be closer to actual nefarious morality). But at the very least, I think I’ve been playing Pip as a Kind Worm Boy. Or, I hope I am.

Surrealism, as I once wrote when describing the upcoming game Figment, is the “illogical illustration of one’s dreams.” The well-known art movement of the 1920s was home to famous artists like Max Ernst, Giorgio de Chirico, and Dalí, of course. Fittingly, the dreamlike world in Karma. Incarnation 1 is as illogical as can get. None of the creature’s in Pips bizarro land speak any language. All interactions are resigned to incoherent gibberish, with illustrated animations to show the impossible words they’re spewing out. It makes the morality kerfuffles—or karma, I guess—increasingly harder to navigate. But in the end, perhaps that’s the point.

Karma. Incarnation 1 is available for PC and Mac for $8.99 .

The post Karma. Incarnation 1 doesn’t hold back on the psychedelia appeared first on Kill Screen.

El Hijo could be the spaghetti-western of your dreams

A man in black, little more than an extension of the flat shadow of the umbrella he carries, rides across an open desert. On his saddle sits a naked boy—a wide brimmed hat his only protection against the burning sun. The pair stop at a post, a marker, and the man places the boy on the sand. “You are seven today. You are a man now,” he tells his son. “Bury your first toy and the portrait of your mother.”

This is how Alejandro’s Jodorowsky’s infamous surrealist western, El Topo (1970) begins. This moment of becoming prefaces a spiritual journey for both son and father, a journey into a unnerving and dreamlike world of violence and bizarre religious imagery. El Hijo, a newly announced game from German developer Honig Studios, takes this beginning as its impetus, but its journey is something entirely different.

Like the nameless boy of El Topo, the titular son of El Hijo is forced to bury his first toy in an unforgiving desert. Then, left by his outlaw father at a remote monastery, he is to be raised by a sect of ancient monks. But bored by this pious life, he sets out to escape and recover his lost toy, on a path that will lead him first to the desert, then to the town beyond, towards a confrontation with his father.

It’s a story that seems set to refocus the spiritual quest of El Topo on the innocent son, not the murderous father. In doing so, El Hijo appears to be a Bildungsroman, a coming-of-age story that tracks a young character’s becoming. We might think of the spiritual journey of Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha (1922), or perhaps the escape from ritual to a wild landscape of creatures as depicted in Mervyn Peake’s Boy in Darkness (1956).

looks to carry the romantic atmosphere of Sergio Leone’s spaghetti-westerns

Taking the form of a stealth adventure, El Hijo will be split into three chapters, as the son escapes from the monastery, crosses the desert, and tracks his father to a dust-swept town. And unlike El Topo it will be entirely non-violent. Instead of takedowns and silent murder, this will be stealth marked with the naive and romantic mischief of childhood. Distraction, pranks, and trickery is what will allow the player to distract the monks, outlaws, and creatures of the desert.

In that sense El Hijo doesn’t just draw for the spiritual fantasies of Jodorowsky. Set in a mythical American West, it also looks to carry the romantic atmosphere of Sergio Leone’s spaghetti-westerns. While those were violent films, they also showed a love of slapstick, grotesque characters, and a preoccupation with trickery, from juggling hats with bullets, to scenes entirely played out with pipes, cigarillos, and strange ways of lighting matches.

Yet, beyond this rich patchwork of influences, it’s the striking look of the game that has me the most excited about El Hijo. Though I’ve only seen early art, the play of light and shadow along with the screenprint texture and limited palettes suggests the influence of Saul Bass and his influential title sequences. When combined with statues and shadows that bring to mind The Good the Bad and the Ugly’s (1966) beautifully shot monastery, you have a game that looks more like a classic bit of cinematic poster design than a piece of interactive art.

It’s still early days for El Hijo, with a potential release in summer 2017, but Honig Studios’s awareness of the genre it’s stepping into and its visual sophistication suggests good things for a dreamlike spaghetti-western with a long journey ahead of it.

Find out more about El Hijo on its website.

The post El Hijo could be the spaghetti-western of your dreams appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers