Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 37

October 25, 2016

Dungeons of the mind: Tabletop RPGs as social therapy

In the heart of Seattle, a gathering of teenagers sit around a wooden table. It’s covered with character sheets, Dungeons and Dragons (1974) player manuals, and hand-drawn graph paper maps. Pencils, pewter figurines, and dice of various shape are scattered about. The players’ attentions are transfixed on the words of their charismatic game leader, Adam Davis. Davis has a decade of life experience over his players, but communicates with a youthful energy and utter commitment. His role is vital, building the fictional world for these players to fill with their unique characters. Through collaborative storytelling and rolls of the dice, they’ve built an epic fantasy saga. As Davis describes their latest adventure, his hands expressively gesture from behind a cardboard partition.

In passing, this evening of Dungeons and Dragons doesn’t look out-of-place. Similar games like it are found in countless libraries, school classrooms, and basement hangouts across the nation. But this quest holds special significance. Just a few months ago, these players were absolute strangers—all teenagers who suffer from underdeveloped social skills. Some are on the autism spectrum, others have simply struggled to find their place in life. They’ve come together under Wheelhouse Workshop, an innovative therapy company founded by two licensed therapists, Adam Johns, and the aforementioned Adam Davis. Through a blend of drama and recreational therapy techniques applied to tabletop role-playing games (RPGs), they’ve helped dozens of kids who often go untreated by mainstream psychotherapy.

Medieval torture chamber, via Wikimedia

Tonight’s quest involves fears and phobias. Before the start of the session, Davis has all of the participants write down their character’s greatest fear on a piece of paper. Their team has been overtaken by a spirit, who will show them each a vision of their worst nightmares. The other adventurers will share the hallucination, and must talk their compatriot free from the draw of evil—whispers in the corner of their mind.

Davis flips the first piece of paper. The character (a dwarf obsessed with cheese) fears a world without her beloved dairy treat. A Wonka-esque torment ensues. The players see a world where everything is made of cheese but turns to ash as soon as it crosses the dwarf’s lips. The group laughs and talks their friend away from the spirit’s lure. It moves down the line.

“My greatest fear is being alone”

The next player insists his character fears nothing more than hurting his friends. Davis takes the Necromancer down a bleaker path. “You see your friends stretched out on torture racks, and see your arm holding a knife up to their skin. You feel a strong desire to hurt them, to make them bleed.” The player recoils slightly, while the other three shout words of encouragement that will spin in the Necromancer’s mind. “You don’t have to do this! This isn’t you!” The player pauses, breathing deeply. “But what if this is me?” He sits quietly and considers the character. He considers himself. The Necromancer sets down the weapon, and the next vision begins.

The spirit enters the last player. Davis lifts the remaining piece of paper, which simply says “My greatest fear is being alone.”

“You look down. You wear the clothing of an elven ranger, and you’re standing under a tree in a desert. There’s nothing in any direction, as far as you can look. Just sandy flat terrain in every direction. You are completely alone.”

The player’s reactions are subtle, and muted. He stays silent, but his eyes show deep contemplation. His eye line darts away from the gaze of the group. After a beat, the other players fill the silence.

“You’re not alone.”

“Your friends are always with you.”

“We’re here with you no matter what, even if you can’t see us.”

The spirit is vanquished.

///

Wheelhouse Workshop has hosted countless sessions like this over the past three years. Currently, they’re managing five games every week. Each one carefully designed to develop the social skills each player is struggling with.

Wheelhouse Workshop began when Johns and Davis—both lifelong tabletop game players—realized that collaborative RPGs had untapped potential for narrative therapy. The technique they developed encourages patients to separate themselves from their problems, often by putting them in a less threatening context. This achieves something called ‘aesthetic distance’, where the patient feels removed enough from their issues to feel comfortable discussing them, while maintaining a level of appreciation. In the field of Drama Therapy (of which Davis has a Master’s degree from Antioch University), aesthetic distance is achieved through improv games or scene work. But for patients suffering from social issues, those practices often prove ineffective.

via Reddit

“There’s some resistances that might come out of doing a drama group, specifically with our demographic of kids dealing with social anxiety, awkwardness,” Davis said. Re-enacting social situations through a dramatic lens works for many patients, but the kids of Wheelhouse Workshop often resist opening themselves in such a way: “If I had them in a drama group, they wouldn’t show up.”

Adding rules, structure, and genre to a narrative therapy session allows these patients to experience that vital distance. When their character experiences an issue that is relevant to the patient’s real struggles, the patient is able to face it with a buffer provided by the fiction. Kids who may never open up in a direct conversation with a therapist can find a voice in their character.

With this comfort established, Johns and Davis can craft fictional adventures that challenge kids to use the social skills that they struggle with. A player with a history of off-putting body language may find her character at a fancy dinner party, and witness how their behavior makes others react. Another who feels hesitant to speak up may find their character with a unique ability to communicate with ghosts, giving them an important communication role within the party.

collaborative RPGs have untapped potential for narrative therapy

Pairing social skills development with D&D may seem like an obvious fit, especially since RPGs have always been associated with the socially downtrodden—stereotypes about D&D being an antisocial activity have permeated the mainstream for decades. However, it’s now easy to see that the game has always been therapeutic for those who fall outside societal lines.

“People who grow up highly interested in fiction and having a certain flexibility of identity—who willingly place themselves into other fictional words and embody characters—are often seen as abnormal or disruptive to the status quo,” said Sarah Lynne Bowman, a professor at Richland College who wrote her dissertation on the power of role-playing games. “Co-creating a fictional universe together without an audience, having no expectation of profit, and playing a different role than one normally does in society can feel threatening to the mainstream.“

///

Davis, Johns, and Bowman are all part of a growing community that is working to make tabletop gaming standard practice for a variety of psychological issues.

Jack Berkenstock is one of the founders of the Bodhana Group, a nonprofit organization that advocates for this cause. They’re the founders of Save Against Fear, an annual tabletop gaming convention in Pennsylvania that focuses on RPGs as a healing force. For five years, they’ve attracted hundreds of local players for a weekend of gaming and enlightened discussion. What initially started as a simple fundraising event for Bodhana has grown into an annual gathering for therapists, game creators, and players interested in the deeper potential of roleplay. Though some attendees have still needed some convincing upon arrival.

“We’ve had presentations that are all about telling people [to not] be afraid of this idea of therapy in your D&D,” notes Birkenstock. His work has often brought him in conflict with players who worry that using tabletop games for this purpose is a ‘corruption’ of the medium. “We’re not trying to suck [the fun] out with some cosmic straw. The model of play therapy demands the game be engaging and fun. ”

Photo of D&D pieces, by Carsten Tolkmit, via Flickr

Save Against Fear has played host to deep conversations on how role play gives a unique perspective into the psyche. Sessions have dug into deep questions, like what character creation can say about a player. ”What is a person viewing as an indicator of strength? What do they view as positive or beneficial qualities?” Birkenstock said.

“Everyone plays their character for a reason,” Davis remarks. “Every decision in [the character creation process] allows them to include some part of themselves.” These rogues, barbarians, and dwarfs are an outlet to experiment with untested social skills and roles. It’s proven a remarkable tool that has just as many educational purposes as therapeutic ones.

///

Hawke Robinson is the leading force behind RPGResearch.com, a growing database that serves as a central resource for collected sources on the many uses of tabletop games in therapeutic and educational services. Robinson himself came to psychology later in life, pursuing a degree in Recreational Therapy after retiring from his career in the technology sector. A lifetime tabletop game player, Robinson was quick to pick up on their unseen potential.

“In all the textbooks, they said over and over that there’s lots of great competitive games, and there are physical cooperative games, but a dearth of cooperative tabletop games for recreational therapy,” Robinson said.

The wish to fill this need has pushed Hawke’s research efforts, including running games with groups from varying backgrounds. This has included sessions with the physically and mentally disabled, collecting longitudinal survey data on the impact of play.

“If it’s fun, they’ll do the hard work”

Currently, he’s working on a custom-built trailer to bring these sessions to new areas without worrying about space restrictions. One session he has planned for early next year was designed around a group of children and adults with high-functioning autism in Tacoma, Washington. It was developed in association with Partnerships for Action, Voices for Empowerment (PAVE). While these participants are capable enough to have fallen outside government care, they still rely on their parents for many daily necessities. Transportation has been a regular struggle, with many of these people experiencing high intimidation when using public transportation. In the past, PAVE has attempted to educate those in need through personal lessons with public transit employees, and guided tours of the system. However, few participants showed meaningful progress.

To tackle the issue, Robinson has planned a hybrid tabletop/live-action RPG loosely inspired by Marvel’s Agents of SHIELD series. Players take on the role of a SHIELD task force, who have received intel that a super villain intends to spread a noxious, zombifying gas through the city’s buses and trains. But to avoid panic, the government has insisted the problem be solved without shutting down the system. After creating characters and receiving a debrief, players engage with a tabletop campaign. On paper, they travel the city by bus and train, follow leads, and unravel a vast conspiracy that threatens to turn Tacoma’s population into the living dead.

By setting the tabletop game in their hometown, Robinson has integrated the real-life bus maps, schedules, and habits into the campaign. A player who has avoided using the bus their entire life due to anxiety can confront that fear through role play, learning necessary behavior in the process. “The game isn’t about the bus, the game is about beating the bad guy,” Robinson said. “Learning how to use the bus is just a means to an end. By giving them this goal, we can keep them engaged enough to teach them what they need to know. If it’s fun, they’ll do the hard work.”

Once every player has demonstrated confidence in their skills, they move into the live-action segment. Individually, each player takes the bus (accompanied by a guardian) to a central depot at a predetermined time. They meet and engage in a cross-town scavenger hunt, following clues to stop the outbreak. By the end, the skills and comfort level achieved with the game should give players the confidence to integrate it into their daily routine.

“The main philosophy of recreational therapy is [that] we make it so people will stick to the therapy they need to better their quality of life,” Robinson notes. He brings up comparisons to the physical therapy asked of patients regaining their mobility. “They dread the therapy sessions, and after they stop seeing the therapist, they stop doing the exercises.” The muscles atrophy, and patients find themselves in a vicious cycle. These same trends show themselves in psychotherapy. The progress made fades without use. Integrating an activity that holds appeal gives patients a reason to engage with the healing process. Short-term satisfaction is key to seeing long-term results.

Robinson’s research has seen him bring various forms of game-enhanced therapy to many groups, from teens leaving juvenile detention facilities (finding new social circles outside of gang life), to patients recovering from traumatic brain injuries (regaining vital motor skills). But for these healing practices to become normalized, qualified Game Masters are needed.

In addition to his research and volunteer work, Robinson has developed a certification regime for leading therapeutic game sessions. Ideally, it could ease the curve for therapists who don’t have a lifetime of game experience, who wish to integrate tabletop RPGs into their practice. By setting professional standards, the groundwork is laid for more formalized research and development.

The desire for standards is a primary concern for Johns and Davis, who hope that, by communicating with other practitioners, therapeutic RPG sessions could become as standardized as dramatic therapy. From there, the technique could be applied to countless other mental hurdles—from Attention-Deficit Disorder to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. But for now, the practice will continue to grow from the fringes.

///

Header image: Beholder, by Steve and Shannon Lawson, via Flickr

The post Dungeons of the mind: Tabletop RPGs as social therapy appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 24, 2016

Farewell posts are for herbs

There are two ways that writers on the internet announce career changes: either by tweeting about how they found out they got laid off, or by publishing a grandiloquent “farewell post.” You know the type: endlessly generous, ruminative, peppered with musings on the industry and hyperlinks to the writer’s greatest hits. It is a way to assemble a legacy. “Stay tuned for my next adventure!” these posts conclude, shared on Twitter with “CRYING” or “THIS WAS DIFFICULT” or “Announcement!” It is a grand exercise in personal branding, writ in humblebraggery, and it is for herbs.

Today, though, is my last day at Kill Screen, and as this day approached I felt the fell compulsion. I do not want to be a herb. I thought about just sneaking out the backdoor, fading softly into the internet and reemerging somewhere else in a few days—that always worked in college. I thought about passing along some larger musings on the future of videogames or the nature of editing online. I thought about commemorating the many happy memories I have at this company, or pinpointing the writers and editors whose work here has inspired me, the dozens and dozens of friends I’ve made, or somehow reasserting the fundamental value of Kill Screen’s mission. I wondered if I could just fucking torch the place, you know—name names, drop thermonuclear subtweets—or if I could do that thing where the newly unfettered writer acts like they are at last free to espouse their opinion on topic X. BioShock sucks! PR is bad! Jamin is a werewolf!

All of these are bad ideas. They are for herbs. Editing is a job. Dentists do not fill a goodbye cavity. If you like Kill Screen, I have good news: tomorrow it will still be Kill Screen. If you don’t like Kill Screen, I also have good news: tomorrow it will still be Kill Screen.

I won’t be here, though. See you around, and be good to each other.

The post Farewell posts are for herbs appeared first on Kill Screen.

Rudyard Kipling’s classic novel Kim is now a videogame too

Rudyard Kipling is a complicated figure. On the one hand, you have the arch-colonialist, the author of the poem “The White Man’s Burden,” and an all-around fan of Empire and the progress it supposedly represented. The man who spoke of subjected populations as “Half-devil and half-child,” and celebrated the bloody project of colonialism as a way to uplift the natives of India, the Philippines, and Africa to (British) civilization.

But then there’s Kim (1901), the story of a young British orphan raised as an Indian native. At once a children’s story, a travel narrative, and a genuine work of joy in its 19th-century cultural landscape, the novel delights in the sheer variety of that part of the world—where Muslims, Jains, Hindus, and Buddhists intersect not merely as colonized subjects, but as people. Indeed, the book has perspectives rare in the 19th century, as when, say, an Anglican clergyman’s partisanship is critically exposed: “Bennett looked at him with the triple-ringed uninterest of the creed that lumps nine-tenths of the world under the title of ‘heathen’.” In short, it is a complicated text, especially when viewed in relation to its arch-colonialist author.

the more adult problems of the world remain just out of view

Now Kim has been made into a videogame by the Secret Games Company. It’s been realized as a top-down roguelike that has you wandering from Lahore to Allahabad, to Delhi and back again, across a vividly colored, hand-painted-style terrain. The player has three years to simply wander before Kim reaches manhood and the game ends. This involves jaunting along the same railway network that contributed to famines (where any grain from famine-struck areas could easily be shipped away from those who needed it), and through cities whose rebellions and uprisings are still recent history. But the cities are bright, beautiful, and new to a native of Lahore—and this vivid, childlike world is the great joy that Kipling and, in their turn, The Secret Games Company are trying to show you.

This adolescence is the game’s main draw and its saving grace: Kim is a child, and the more adult problems of the world remain just out of view. There is only a brighter, kinder world that remains visible as you travel from town to town with a Buddhist Lama and a childlike indulgence in the minuteness of the moment, and not the bloody scope of history. Kim, the novel, works as a piece of children’s literature because of this focus; Kim, the videogame, tries to bring that focus to the experience of the road: “Roads were meant to be walked upon, houses to be lived in, cattle to be driven, fields to be tilled, and men and women to be talked to. They were all real and true—solidly planted upon the feet—perfectly comprehensible—clay of his clay, neither more nor less.”

In short, Kim—both the novel and, to its credit, the game—reminds me of this: when I was 16, I went to India with my mother and my uncle. We spent a few days in Darjeeling, a town in the North-Eastern part of the country, where the eponymous tea is grown, and stayed at a colonial-style hotel called the Windemere. One evening, two other guests played Gilbert and Sullivan songs on the hotel’s out-of-tune piano. Outside, down the slope of the hills grew Darjeeling tea; beyond was the mountain Kangchenjunga, which would remain perpetually visible as we moved further into Sikkim. Even as I grew older and my knowledge of the dark weight that these things carried grew, it did not stop being beautiful.

The full versions of Kim is available for Windows and Mac on Steam as of October 24.

The post Rudyard Kipling’s classic novel Kim is now a videogame too appeared first on Kill Screen.

A new dating sim highlights the pickup artist’s ugly game of seduction

The dating sim has been experiencing something of a reexamining of late, finding itself in the broader public eye as iterations upon its core tenants are warped, distorted, and pushed past their typical use cases. Whereas dating sims were once predominantly focused around a male protagonist trying to date—and eventually have sex with—beautiful women, the modern dating sim is unbounded. It rejects the notion that a potential partner is hetrosexual (Kindred Spirits on the Roof and Don’t Take It Personally, Babe, It Just Ain’t Your Story), “perfect” (Katawa Shoujo), or a human at all (Hatoful Boyfriend and Hot Date). The modern dating sim focuses on the idea of love, writ-large, and is less concerned with the titillation of the player or upholding what could be seen as “normal,” “right,” or “obvious.”

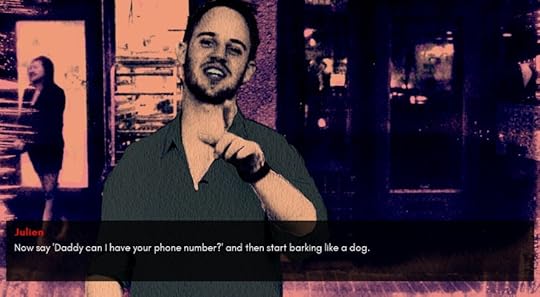

makes the player feel supremely assaulted

Angela Washko, the prolific game art (and now art game) creator of “The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft“ and Free Will Mode, a project curated into the Memory Burn gallery show, among many other projects, is continuing to push the dating sim forward by reflexively focusing on dating itself. Upending the idea that the game must only tangentially acknowledge real-life dating, Washko’s latest exhibit titled The Game: The Game centers around its female protagonist’s interactions with real-life Pickup Artists like Julien Blanc and Roosh V—people whose work focuses on teaching men how to get women to have sex with them. “The Game” of The Game: The Game refers to this “skill,” and forces you to be on the receiving end of these teachings, an experience that is, perhaps unsurprisingly, unsettling.

The game, debuted at the Transfer gallery in Brooklyn, is overwhelming. Far outside the cozy narratives of “just finding love” forwarded by even the most progressive dating sims, the cumulative effect of having to reckon with the in-game characters (only Blanc in the version I played) and an ominous soundtrack by Xiu Xiu, makes the player feel supremely assaulted. In addition to that, the curation of the space at Transfer featured Blanc himself on a screen preaching his teachings, as well as women-as-object postcards painted on the ground. It casts a different shade of light on other dating sims (and dating in general), forcing an increased sense of awareness about the receiving end of whatever mechanic you’re exploiting to woo a woman. It literally places you in the shoes of someone who could be thought to be on the receiving end of some other player’s own dating sim.

Benjamin Bratton, writing in the show’s brochure, perfectly describes this asymmetry:

“When two or more people think they are playing the same game, but are in fact negotiating different rules, and when each player’s meta-participation in the game that they think they are playing is through the self-aware persona of a player (of those different games), then decoding the signal, niche, and response boundary cues of who is saying what to whom about what and why lends to interpersonal conspiracy theory and comic obliviousness.”

Except that, in the case of The Game: The Game, we are able to pin down what the men are saying, as it’s backed by their words, pulled from the material they’ve contributed to discourse around “the game.” Washko uses this ground truth as an inflection point, and injects her own game in front of the game that people like Roosh V and Blanc are known to be playing, forcing each “player” to reckon with the the realities of the other. Washko is giving a voice to those that are forced to be a target of the tactics of these men, empowering the player to simply not be a consenting agent to the taught tactics of a pickup artist’s game, offering the potential for an alternative narrative to the one forwarded by the books of Roosh V and videos of Blanc.

attacked and rated on how “bangeable” she was

This agency given to the player, to be implicated in both their game and their own, is important. Washko gives her players a wide range of dialogue options to choose from in each scenario, allowing them to choose whether or not to let Blanc “win” or “lose” at the game he is playing. Your victory state, as it relates to his, is unclear, and purposefully so; Washko sees you as a consenting adult, implicated in whatever passes, able to cognizantly choose what to say, reflecting the fact that Blanc’s real-life tactics do sometimes work for some people.

The environment Washko creates around these situations and the agency the player is given is part part of her larger, ongoing exploration around cultural touchpoints—those that position women as objects, as well as a critical interrogation with pickup artists and their tactics in general. After a lengthy performative Skype interview with Roosh V, she found herself wrapped up in his community as well, attacked and rated on how “bangeable” she was. This was one-sided though, and The Game: The Game acts as her response to this; her act of looking and examination passed to other players, in hopes that they too can see what she has been looking at. The Game is not meant to be derogatory or condescending, as stated above, all of Blanc’s lines are pulled verbatim from his own videos, but when placed in front of someone with agency not typically granted by someone like Blanc, his advice turns seemingly malicious.

The game-ness of The Game: The Game, crystallizes the points Washko has been getting at ever since she first interviewed Roosh V. Though they speak of having sex with women like a game, the complex dynamics of social scenarios make such a discrete projection difficult, as each new bar, each new club, has a different set of challenges that allow them to obscure any dismissal of what they do as fundamentally flawed or misguided. These differences allow people like Roosh V and Blanc to slip through criticism of their own failings (evidenced in Blanc’s videos specifically), but with Washko’s game, their movements and their tactics are mummified, allowing the player to pass over them multiple times, through different vectors, while external factors remain constant. The “game” is laid bare and illuminated in The Game as Washko shows that there are, in fact, two players, not just one.

Find out more about The Game: The Game on its website.

The post A new dating sim highlights the pickup artist’s ugly game of seduction appeared first on Kill Screen.

Orwell wants you to spy on people over the next few weeks

Part of the national security Safety Plan in Orwell’s world is a program that employs citizens to spy on other citizens. Aptly, it’s called Orwell. As a government spy in the game’s world, you’ll be able to scour others media presence—and chat conversations—for suspicious information. Creator Osmotic Studios started rolling out the five part story last week; the first came on October 20, with the second coming on October 27.

Episode three follows on November 3, with four coming on November 10, and the final installment on November 17. “The weekly release structure is a nod to the thriller nature of the game,” publisher Surprise Attack Games’s Chris Wright said. “I’m pretty sure we’re the first game to release in this weekly episodic format rather than the usual extended gap most episodic games have.”

What we’re left with is an experience that feels so curated that it’s distracting

And that works for Orwell. The game’s first two episodes move quickly as you uncover sequences of information spread across the web. A company’s job listings page leads to an email, which leads to a media profile, which leads to an instant messenger screen name; sifting through this sort of information—albeit, fake—begins to feel creepy after a while.

Innocuous sentiments expressed online have serious implications for these characters when peeked in on by a set of stranger’s eyes. It’s intended, though; while Osmotic Studios has said it’s not trying to dish out answers, just ask questions. The studio certainly is asking questions, though those questions are so perfectly set up, with each suspect’s information neatly highlighted for you to select.

What we’re left with is an experience that feels so curated that it’s distracting, lacking the sort of nuance and implied danger of government surveillance—especially in a country with an ongoing series of terrorist attacks. So, sure: Orwell is asking questions, but those questions are far exactly what you’d expect from a game called Orwell. This is only the beginning, though. We’ll have to see what else Orwell has it continues to unfold over the next few weeks.

Orwell is available on Steam for $9.95. Episodes will unlock automatically each week.

The post Orwell wants you to spy on people over the next few weeks appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Invisible Hand wants to make trading exciting, but also boring

Working as a trader used to be a glamorous—if also morally dubious—job. Note the use of the past tense in that sentence: Wall Street (1987), with its yelling into phones and power-suits, power-lunches, and power-everything-else is a thing of the past. It’s not for nothing that the most exciting cultural portrayal of traders in recent years, Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), is set in the recent past.

What happened? In short: math and computers. The balance of power shifted from those executing trades to those who created the models on which those trades were based. In The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and the Markets (2001), Nassim Taleb writes about a time in the 90s, when “every plane from Moscow had at least its back row full of Russian mathematical physicists en route to Wall Streets.” Traders still have well-compensated jobs in this new world, but they are subservient to the quants. They are also the most expendable parts of the trading equation.

powerlessness and power sit uncomfortably alongside one another

This would therefore appear to be a very bad time to make an interesting game about traders, but that’s exactly what Kolkhoze Games is trying with The Invisible Hand. In the age of the “walking simulator,” menial tasks are rich fodder for games, but even this might be pushing it. An atmospheric game about the stock market, as suggested by this preview video focusing on sunsets through an office window, is a curious idea:

Still, the creators maintain that there will still be things to do in The Invisible Hand. Here, for instance, is the opening entry in the game’s development log:

THE INVISIBLE HAND is a game about traders, and their world. At first glance, it is only about numbers, but in the end, it is about much more.

In a world where computers can do most of the analytic work, you will live the life of a trader, and try to profit off the numbers spewed by the machine to get the best of what the world has to offer.

Whether you just follow the missions given by your supervisor or go rogue and put people to their knees for your own profit, it is up to you to make money for the well being of the company, and your own.

The Invisible Hand taps into a great irony, which is that the damages from rogue traders have increased even as the systemic power of traders has steadily decreased. In late 2006 and early 2007, Société Générale trader Jérome Kerviel managed to compile €49.9 billion in unauthorized trades. When the market went south a year later, he had amassed losses of €4.9 billion—far more than he would ever have been allowed to make. He’s been in and out of court ever since, including a rather comical attempt to get the severance he says he was owed. Actually.

In the world of The Invisible Hand—and, perhaps, our own—powerlessness and power sit uncomfortably alongside one another. The vestiges of power are still visible around the edges of the world, but only there. Otherwise, it is a dull existence. Maybe that’s where the temptation to go rogue comes from.

The Invisible Hand is not pitched as a social experiment per se, but it’s easy to think of it in those terms. Like Papers, Please (2013), it asks what you would do in a situation that is both oppressive and, in a certain frame of mine, also empowering. What these games seem to get at, above all else, is that the transition from a prestigious job to a menial one is awkward. Border guards have this tension between power and tedium, but it is even stronger with traders. How do you go from Wall Street to the part of the equation most likely to be automated? Wouldn’t you want to grasp for that gilded world one last time? Maybe you could. Maybe.

You can keep up with the development of The Invisible Hand on Twitter, Facebook, and the TIGSource forums.

The post The Invisible Hand wants to make trading exciting, but also boring appeared first on Kill Screen.

Jason Rohrer’s next game is a twisted take on child rearing

Jason Rohrer’s last game, the home defense MMO The Castle Doctrine (2014), revolved around protecting what’s yours: your family, your wealth accumulated through rounds of burglary, your carefully designed web of traps and defense. It was a ruthless world, a merciless place where your measure of success is how good you were at dismantling other’s work and stealing their goods.

So it seems ironic that his next game (working title One Life) starts you off as completely defenseless and reliant on the kindness of online strangers. Enter the world in Rohrer’s currently unnamed MMO, and you find yourself birthed to a random player in the world as a helpless baby that struggles to move and care for itself. You can’t even speak properly, as your text chat length is limited by age; a baby can only speak in single characters and an old man can relate entire sentences. A digital lifetime awaits you, if only your guardian raises you to the point of self-sufficiency. They can just as easily leave you abandoned in the world, slowly starving.

The Castle Doctrine (2014)

“When you’re born to them, you’re helpless. You can’t move very quickly. You can’t really gather your own food, you’re starving to death, and so on just like all the other players in the game, except you’re at a big disadvantage because you’re a newborn baby. Your survival depends on this human player you were born to deciding to not walk away from you,” Rohrer explained in an episode of the podcast Checkpoints. He goes on to state the intriguing relationship between veteran player and newborn, as any player already surviving only made it to that point due to the help of another. Will you return the favor when the responsibility falls on you?

But survive past those early moments, and you have an hour-long lifetime in this sprawling open world with the usual survival elements of crafting, building, and gathering resources. Perhaps you venture out and explore, or construct a home, or begin amassing a great legacy, each minute essentially a passing year. Die of old age, and the cycle begins anew, as you’re once again born to a random player. This generational cycle paves the way for a variety of fascinating possibilities. Your rebirth could find you dropped into a life of luxury to a wealthy player, or as the child of an enslaved player, or to a kind player who has started a orphanage to care for abandoned infants.

A digital lifetime awaits you, if only your guardian raises you

In the hours or days between dying and logging back on, entire lifetimes and eras of players will have gone by, the persistent world would have progressed and expanded. Rohrer describes this cumulative technological growth: “In the beginning, the world has no technology in it. It’s just natural resources and wilderness … If you join the game right at the beginning, everyone’s basically Stone Age, and if you come back the next day or two days later, many generations have lived in the world, and worked, and have built up houses, and have built up capital and resources. Somebody’s built a grain mill, somebody’s got an oven … and you come into the world and there’s some civilization.”

One can only imagine what the kind of world players will be born into a week, a month, a year later at that accelerated rate. A resource-stripped wasteland? A dystopian infrastructure that corrals all new infants to be raised as slaves? An infant-raising utopia?

Jason Rohrer’s upcoming survival MMO doesn’t have release date yet, so you can keep an eye on his site and Twitter page.

///

Header image: Newborn, by Jlhopgood, via Flickr

The post Jason Rohrer’s next game is a twisted take on child rearing appeared first on Kill Screen.

One Doom fan, 300 hours, and one gargantuan level

The first time I ever made a Doom map I simply created a few rooms and hallways, then added a couple of enemies and some ammo. But Ben Mansell created something a little more complex with his first Doom map. After 300 hours and over a year spent on it, Mansell is ready to unleash Four Site into the world. A map so large it will take most players two to three hours to complete.

Four Site is massive—essentially four decent-sized Doom maps put together. Each section has its own look and feel, and the pacing is unlike many modern Doom maps I’ve played. Modern Doom maps seem to focus on using more powerful hardware to throw bigger waves of enemies at the player. With Four Site, Mansell wanted to create a map that hearkened back to the older maps found in the original Doom (1993) and Doom II (1994).

But he was also inspired by another series of games: “If there was one big influence, it wasn’t Doom at all, but the Dark Souls series,” said Mansell. “Some of Miyazaki’s levels in the series are masterclasses in progression, non-linearity, and environmental storytelling.” He specified that a level like Tower of Latria from Demon’s Souls (2009) was perfect example of how to “unfold a level to a player.” Tower of Latria left an impact on Mansell, as he explained: “There’s a prison section later on in my map that in hindsight is pretty much a direct tribute to [Latria].”

The idea for the map has been in Mansell’s brain since 2003—it was then that Mansell, while in a college lecture, started doodling the idea for a Doom map. “Somewhere in my old lecture notes there’s probably a roughly drawn outline of the map!” said Mansell. But he never did anything with the idea until last year. He had no idea if he would even be able to make Four Site. He described the process as a “trial by fire.”

“That room alone probably took 30 hours or more to get right”

As said, it took him over 300 hours to put Four Site together, not to mention months and months of planning on paper. Some sections of the map came together relatively quickly, other sections, however, took considerably longer. One such section was an ascending tower found in the last part of the second section.

“Working out how to get the Lost Souls to teleport in at the right time at the right height (given Doom handles height in a rather limited way) took a lot of head-scratching,” Mansell said. “I ended up with a spreadsheet of different heights and formulas to work out where to position the Lost Soul spawn-points. That room alone probably took 30 hours or more to get right.”

-Ben Mansell’s 1 hour playthrough of his massive Doom level, Four Site

With Four Site finished, Mansell has made the map available to anyone who has a copy of Doom II. He was surprised by the reaction the map got after posting it on Reddit. Within days it was being covered by numerous sites and being shared across Twitter and forums. As to why the map has become so popular, Mansell believe it’s partially due to nostalgia: “My map perhaps struck a chord by being so resolutely old-school yet still unusually large. It’s quite a traditional Doom map in some senses, following the kind of nonlinear, sprawling design principals many modern FPSs shy away from.”

Mansell wants to make another Doom map, but he’s going to take a break first. Instead, he is going to play maps made by other creators. “I’ve about six years of Doomworld.com Cacoward winners to catch up on, so I don’t think I’ll be short of amazing Doom maps to play any time soon!”

You can download the Four Site .wad here and use GZdoom, a modern sourceport, to play it.

The post One Doom fan, 300 hours, and one gargantuan level appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Curious Expedition is a disturbing portrait of the colonial mind

I could think of any number of better titles for The Curious Expedition. Here’s a few: Colonialism Simulator 1900; Literal Tomb Raider; Uncharted 5: The White Man’s Burden. Virtually anything seems better than the title the game actually has.

You do embark on an expedition every time you play it—an adventure into foreign jungles on the other side of the world, where priceless treasures, golden pyramids, and possibly dinosaurs lie in wait. But “curious” seems like an incredibly inappropriate word for what you end up doing there. You will almost always encounter a tribe of “natives”—language and culture unspecified, because it doesn’t really matter to you. You will almost always exploit them in some way: take advantage of their hospitality; trade worthless beads for their most prized supplies; massacre them; enslave them. You will steal totems from their most sacred shrines and laugh as the earth itself protests with massive quakes and violent eruptions. You will return to London with a bag full of pillaged goodies for the British Museum; you will smile and nod as the people cheer. It will all seem “curious” in retrospect. But that way of seeing comes at a moral cost.

it is a pretty good asshole simulator

We’ve come to expect that games that ask us to do horrible things, to reenact huge historical and systemic crimes—torture; mass killing; racial and sexual violence; the marginalization and domination of others—do so with self-consciousness. With a few notable exceptions (e.g. DOOM), it’s hard to think of a modern shooter post-BioShock (2007), post-Spec Ops (2012), that doesn’t ask us to question why we shoot (even if the mode of questioning is simplistic and reductive). It’s also easy to think of games that alienate many players because they don’t simultaneously critique what they simulate: games like Prison Architect (2015) and This is the Police (2016), which make structures of power look benign rather than using game design to expose, and make legible, their inner workings and underlying premises. The Curious Expedition looks a lot like those two games. It’s a simulation of colonial violence that never seems particularly willing to interrogate colonial violence—or even to call what it depicts colonial violence. This is adventure! You’ve got to reach the Golden Pyramid before Marcus Garvey returns home from Tikka-Takka Jungle! (The fact that you can even play as anti-colonial political leader Marcus Garvey feels, like the title, strikingly inappropriate.)

At the same time, the game does something that is self-conscious in a totally different way: insistently and pervasively, it foregrounds the subjectivity and self-involvement of its little pixelated protagonists. Verbs like “seem” overpopulate the descriptive language of the game’s journal: “We felt more than welcome, and the villagers were seemingly excited about our presence.” The journal records emotional responses as much as it records factual events; you get a lot about how “I” feel interlaced with what “I” did. The game’s victory screen, in which you stand Bush-like in front of a banner outside the British Museum that says “TRIUMPH,” feels like a disturbingly personal scene of wish-fulfillment: the masses go wild, shouting “I LOVE YOU” at the top of their lungs. Even the combat traits of your merry band of adventurers tend to be psychological problems: one might be “sexist,” another might be an alcoholic, still another might be a kleptomaniac. “Sanity”—not fuel, health, or supplies—is the main variable that determines survival.

Maybe The Curious Expedition isn’t a responsible colonialism simulator. But it is a pretty good asshole simulator that puts you in the headspace of the colonialist—the white man (even if you play as a woman, even if you play as a black man) who views “natives” as aliens, tools, commodities, and obstacles. The man who cares about nothing beyond fame, fortune, and prestige among his peers. The man who could use the word “curious” to describe the things he did on the other side of the world, because he views it all as an invigorating diversion best enjoyed among frenemies—because he cavalierly disrupts the lives of others to escape the boredom of his own. Even if you play as Charles Darwin, you play as someone a lot more like Donald Trump: an “aging narcissist,” in the words of Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi, pursuing adventure tourism because he “got bored of sex and food.” One could debate the value of inhabiting this perspective at all. Even still, the game is compelling in the way it tries to use game design to illuminate the logic of an egregious historical perspective—compelling in part because that perspective was often drawn to the language of games.

A game about chaos becomes a game about control

The premise of the game is pretty straightforward: you are an intrepid explorer in an organization akin to South Park’s Super Adventure Club, and your objective is to gain enough fame from six back-to-back expeditions to earn a statue of yourself. All the action takes place on a grid of hexagons that looks like a cross between Civilization V (2010) and Catan (1995); you start off each expedition with an almost completely blank map that only reveals its many secrets when you penetrate deeper into it. The more time you spend wandering around the jungles and deserts of distant lands, the more fame and treasure you’ll get—but you can’t dillydally too long, or else your peers, exploring other parts of the world, will return faster than you, or your “Sanity” meter will deplete and random horrible things will start happening. Maybe your idiot Scottish soldier—your party has four additional units, which can be British people, natives, or animals—will drop all your medical supplies and your precious shotgun. Maybe your Persian translator will suddenly become a cannibal. Maybe, upon pillaging a sacred shrine, a nearby volcano will consume the map with rivers of fire. The good thing is any expedition is over when you reach the Golden Pyramid. And it’s always the same Golden Pyramid, even if it’s never in the same place.

The game can feel harrowing and capricious in an Oregon Trail (1971) way—a nostalgic way, heightened by its early-90s, elementary-school-computer-lab art style. A ton of variables determine the flow of any given expedition: the map is randomized; dice rolls determine whether you win or lose in combat against gorillas and angry natives; even more dice rolls determine whether you stumble through a cave alive or step on a stalagmite and die of gangrene. Once you get the hang of it, though, the game transforms into a strangely homogenous and consistent experience. A game about discovery becomes a game about the impossibility of discovering anything. A game about chaos becomes a game about control. A game about variety becomes a game about the interchangeability of its component parts: the natives, who are always the same; the places, which fit into three or four basic templates no matter what continent they’re on; the goal, which is always the same no matter where you’re going. And, of course, the explorers themselves—wildly different historical figures made identical in their fixation on glory, fortune, and each other.

That inevitable experience of sameness sounds like bad game design, but it ends up working in the service of some pretty good writing that seems geared toward the same effect. The game encapsulates the central paradox of the late-Victorian adventure novel, the genre to which it’s most indebted: adventure novels advertise endless variety (no expedition will be the same!), but always end up homogenizing their “exotic” locations and people. One adventure bleeds into the next, as though generated by algorithm; places and people melt into vague assemblages of otherness. The game also ends up encapsulating how adventurers themselves homogenize the rest of the world before they even set foot outside London (which raises a question: do they ever really leave?). In the game, before you begin your expedition, you stand in the middle of a sumptuous parlor and look at an array of randomized destinations on a world map. “Tikki-Takka Jungle” is in Asia; “Yalompani Jungle” is somewhere in the inaccessible interior of Africa, like the Lost World of Kukuanaland in King Solomon’s Mines (1885). Every untapped region beckons with the same alluring blankness.

At the beginning of Heart of Darkness (1899), a novel deeply conscious of the genre tradition from which it emerged, Marlow, the story’s grizzled narrator, describes looking at a map full of that blankness when he was a kid, and feeling the thrill of potential discovery:

“I would look for hours at South America, or Africa, or Australia and lose myself in all the glories of exploration. At that time there were many blank spaces on the earth and when I saw one that looked particularly inviting on a map (but they all look like that) I would put my finger on it and say: When I grow up I will go there.”

When he does grow up, he finds that all the “blank spaces” that once beguiled him have been filled by others. Nothing is still uncharted; every corner of the map is known and controlled. But he retains a “hankering” for a space outside the purview of civilization, a land still veiled in mystery—not so much because he wants the treasures it might contain, but because he wants to have reached it and consumed it before anyone else.

Every untapped region beckons with the same alluring blankness

It’s tempting to frame Marlow’s desire in sexual terms: he wanted to penetrate into virgin territory. But Marlow doesn’t use the language of sex; he uses the language of childhood—the language of play. “I got tired of that game,” he says. On the one hand, his language captures how exploration is always a game: always about winning or losing; always about speed, skill, mastery. On the other hand, he shows us how exploration inevitably enables exploitation—how pursuing discovery in gamelike terms inevitably makes the explorer see places as consumables and people as commodities. To see the world as a giant game board is to see it abstractly, without morality, from a position of bemused detachment. That’s the perspective that enables racist violence and nonchalant pillaging. That’s the perspective embodied by a word like “curious.”

So many videogames—Uncharted, Tomb Raider, Far Cry; the list goes on—follow the template of the adventure novel and try to satiate the desire Marlow felt as a kid: the desire to discover a new place; the desire to discover the Lost World. So many of these games end up plunging us into an exploitative worldview as a result, whether they intend to or not. The Curious Expedition is no exception. But it also places that desire for discovery within another person’s mind, just like Conrad, and keeps its player, like Conrad’s reader, at a critical remove. It lets you see a bigger picture than the grid of hexagons it depicts; it lets you see the mindset that creates the grid, and what that way of thinking inevitably ends up doing.

Rudyard Kipling and many others had a term for Britain’s century-long contest with Russia over the colonial control of Asia. They called it “The Great Game.” Maybe that should’ve been the title.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post The Curious Expedition is a disturbing portrait of the colonial mind appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 22, 2016

Weekend Reading: America’s Ghost Wanted

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

The Family That Would Not Live, Colin Dickey, Longreads

Sometimes it’s a trick of the light, but who knows when you’re sleeping in the most haunted house in America. In an excerpt from Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, writer Colin Dickey writes about a night in St. Louis’s Lemp Mansion, whose beer baron namesake family suffered an uncanny tragic legacy.

Self-Made Supermodels, Leah Schrager, Rhizome

Every social media platform has their star performers, but there’s no question who rules Instagram. Leah Schrager deconstructs the world of Instagram’s DIY supermodels, speaking from experience having become one for an academic project.

Alex Dodge, Semiogenetic, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, NY.

Every Body Goes Haywire, Anna Altman, n+1

The chronic pain that Anna Altman watched in her mother are echoing in her own. Living in the centre of a world of migraines, Altman explores one of the most common ailments experienced in the world, and how little is known about it.

Making Latino Life Visible, John Leguizamo, The New York Times

According to John Leguizamo, actor and one-time Mario Brother, if there’s one silver lining to the Trump candidacy, it is the galvanizing of America’s Latino population out of historical erasure. And a secondary silver lining to that is an excellent essay on the subject from Leguizamo.

The post Weekend Reading: America’s Ghost Wanted appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers