Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 35

October 28, 2016

Mystic Messenger and the power of texting games

If I have learned anything from Mystic Messenger, it’s how astonishingly easy it is to get emotionally invested in a chat with a fictional character. Forget the Turing test, I discovered that I’m happy if my talking partner can pass a Turing quiz.

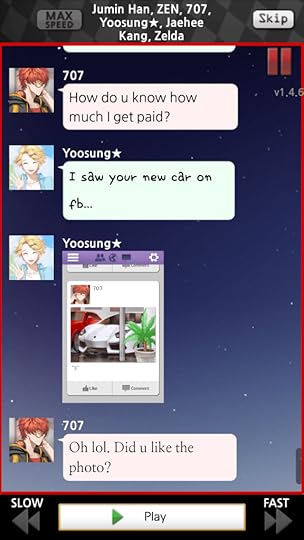

MysMe, as it’s commonly abbreviated, is a mobile dating simulator that takes place almost entirely via text messages, chat rooms, and phone calls. The game is designed to look like a super-secret app that’s used by a super-secret organization called the RFA, which throws super-secret parties to raise money for vague, unnamed charities. Through a series of somewhat shady events, you get roped into joining the RFA and helping them plan one such party.

The premise is hokey, but where it really shines is how it manages to actually make you feel like you’re getting to know these characters. It’s hardly the first game to use texting, but it might be the most successful.

One of the characters is a hacker… and a mobile developer, I guess?

Before we talk about the game itself, it’s important to discuss the expectations set up by the fact that we’re chatting, texting, and calling the characters.

Lisa Reichelt, head of service design at the Digital Transformation Office in Australia, coined the term “ambient intimacy” in a 2007 blog post. It’s something that we’re all familiar with in practice if not by name. “Ambient intimacy is about being able to keep in touch with people with a level of regularity and intimacy that you wouldn’t usually have access to, because time and space conspire to make it impossible,” Reichelt writes.

We all experience ambient intimacy in some way or another, often through social media. Some workplaces or friend groups keep a chatroom going with platforms like Slack or HipChat, which are similar to IRC chats of old. And, of course, there’s texting.

Mizuko Ito is a cultural anthropologist at the University of California, Irvine, and in her paper “Personal Portable Pedestrian: Lessons from Japanese Mobile Phone Use,” she examines the culture around texting habits in Japanese society. She uses the term “tele-nesting” when describing how young people use texting and mobile phones as a “glue for cementing a space of shared intimacy.”

“Many of the messages that our research subjects recorded for us in their communication diaries were simple messages sharing their location, status, or emotional state, and did not necessitate a response,” Ito writes. “These messages are akin to the kind of awareness that people might share about each other if they occupied the same physical space.”

The kind of “lightweight messages” that Ito discusses are certainly welcome from friends and family, but what about from, say, someone who’s not even real?

Enter Xiaoice, a chatbot created by Microsoft that has over 20 million registered users who chat with her regularly. Xiaoice is a modern-day SmarterChild with the personality of a teenaged girl, and as of February 2016, she’s had over 10 billion conversations. This might seem odd at first; if texting is supposed to be a way of reaching out and seeing how loved ones are doing, why would millions of people chat with a robot? Yongdong Wang, who leads the Microsoft Application and Services Group East Asia, points out that “[h]uman friends have a glaring disadvantage: They’re not always available.”

“Xiaoice, on the other hand, is always there for you,” Wang said in an article for Nautilus. “We see conversations with her spike close to midnight, when people can feel most alone. Her constant availability prompts a remarkable flow of messages from users, conveying moods, or minor events, or pointless questions that they may not have bothered their human friends with.”

It seems that, as social creatures, even if we know that someone isn’t real, we can still forge a relationship with them. This is all the more so when a chatbot, like Xiaoice, mimics human-like behavior: “She can become impatient or even lose her temper,” Wang wrote. “This lack of predictability is another key feature of a human-like conversation. As a result, personal conversations with Xiaoice can appear remarkably realistic.”

Rather than entering the uncanny valley, this kind of conversational exchange seems to only strengthen the personal connection people feel with Xiaoice—all without ever physically interacting with her and all with the knowledge that she’s not a real person. What stands out about Xiaoice is her well-defined personality. Just like we might get attached to a character in a book or a game, it’s not a stretch to think that we’d want these kinds of interactions with a fictional person. This is where MysMe sits, at the intersection of narrative storytelling and mimicry of true AI.

at the intersection of narrative storytelling and mimicry of true AI

Though MysMe doesn’t have any natural language processing or the trappings of modern AI, it manages to create the illusion of chatting with friends merely through its user interface. Texting with the characters and interacting with them in a chat room creates the ambient intimacy that Reichelt and others have described. The characters send you “lightweight messages” throughout the day, sometimes texting you about a difficult project they’re working on or calling you to complain about another character.

That’s another way that MysMe fleshes out its artificial world: Just as a friend might chat with you about a mutual acquaintance, so do the characters, who all have their own relationships with and opinions about each other. This is one of its main strengths.

To better understand where MysMe succeeds, it’s worth taking a look at Lifeline (2015) and One Button Travel (2015), which both play out through one-on-one chat. One Button Travel also utilizes a fictional app to tell its story—one that allows you to book a one-way trip to the future.

Both Lifeline and One Button Travel suffer from a few of the same problems. For starters, one-on-one chat isn’t that exciting by itself. The characters—in Lifeline, a needy astronaut named Taylor; in One Button Travel, a version of you who’s stuck in the future—either end up spamming the screen with a ton of information, or you end up asking a lot of boring, expositional questions like “What’s going on?” and “Who’s that?”

You can do one-on-one chat with each of the five characters in MysMe as well, but you get information a lot more organically because they all chat with each other in the all-purpose chat room. It’s way more dynamic because they all have their own relationships ranging from friends to frenemies to reluctant coworkers.

Unlike the other chat games, the characters also type in a way that just seems way more realistic. They use emojis and stickers. They make typos. They share selfies and cat photos and screenshots from Facebook accounts. All of these interactions paint a broader picture of the world they inhabit, even if that world is sometimes, like any good romance, colored with soap opera melodrama. No matter how much the melodrama might seem unrealistic, it’s more forgivable than something like the following exchange in Lifeline:

Taylor, how are you doing this?

Lifeline and One Button Travel also suffer from not taking advantage of the benefits of being chat-based. They don’t seize upon the spark of intimacy, instead falling back on tropes that are common in old text-based games like Zork (1980) and Colossal Cave Adventure (1976). Lifeline is particularly guilty of this sin, asking you to tell the character to “Go east” or “Go west,” decisions that you can’t possibly have any emotional connection to. In contrast, each decision you make in MysMe has a direct effect on your relationships with characters, either by steering the conversation in a different direction or changing the status of your relationships. By focusing too much on the usual methods of advancing the plot, plus making you manage an inventory in Lifeline’s case, you lose the spontaneity and personal touch that can make texting so engaging.

The allure of texting is so powerful that even Casper, the mattress 2.0 company, has come out with a chatbot, the Insomnobot 3000. Its whole purpose is to keep people company late at night when they’re having trouble falling asleep. The only way to interact with the Insomnobot is via text.

“With SMS, we are able to create seemingly real interactions to address a common late night emotion: loneliness,” Gabe Whaley tells DigiDay. Whaley is the CEO of Mschf, the creative agency who made the bot. As you might expect, Casper has ulterior motives, but the bot itself does some things right. It’s armed with an array of pop culture references so you can chat with it about TV shows and mundane daily habits. It also takes the initiative and will sometimes text you at 11 PM, asking, “Are you up?”

Receiving too many texts too often can be off-putting, like an overeager suitor who wants a second date

The 24-hour access that comes with texting is a tool that has to be wielded carefully. Receiving too many texts too often can be off-putting, like an overeager suitor who wants a second date. Texts also have to be context-specific otherwise it feels arbitrary. This is another aspect that MysMe excels at.

MysMe, Lifeline, and One Button Travel all run in real-time, but Lifeline and One Button Travel sacrifice realistic texting to their plots. It’s hard to get a sense of how the characters are moving about their day. One Button Travel once messaged me at 6 AM saying, “Hello? Are you still there?” As though we’d been chatting recently. At 9 PM, I got a text saying, “Just woke up.” Because these games seem to run on their own schedule, it becomes that much harder to suspend your disbelief that these characters are anything more than just that—characters in a game.

MysMe takes a bit of a different approach. It also runs in real-time, but opportunities to chat can expire. You’re notified when characters enter a chatroom, but if you don’t make it into the chatroom in time, they’ll hang out without you, and you can read the transcript afterwards. When you receive a text or call from them, it’s usually somewhat context-specific. Around noon they’ll ask if you’ve eaten lunch yet; at night, they’ll encourage you to go to bed before it gets too late. You’re free to call the characters (if you’re willing to spend the in-game currency to do so), but there’s no guarantee that they’ll be available. If you call a character in the dead of night, you’ll get their voicemail—and they’ll often call you back when they have time. One character will actually scold you if you call him while he’s at work. All this contributes to the illusion that the characters are leading rich, independent lives separate from you, and that the questionable party they’re making you plan will actually take place.

There is an overarching conspiracy thriller plot to MysMe, but it’s a character-driven story at its core. Most of the dialogue options reflect that: you can decide if you want to side with Jumin Han, the icy heir to a large corporation, or if you’ll stand up for Jaehee Kang, his beleaguered assistant. You can help Yoosung, an emotionally troubled college student, get back on his feet or enable him to slide deeper into his videogame addiction.

The stakes aren’t as high as in, say, One Button Travel, where if you fail you’ll get stranded in a dismal future. But those kinds of high stakes can feel extremely abstract, especially in a game that’s 90 percent text-based. In those games, it can sometimes seem like building relationships with the characters are just icing on the cake; in MysMe, it is the cake. And, after you‘ve completed one character’s route, your decisions are even more difficult on future playthroughs as you’re forced to antagonize a character you’ve gotten to know pretty well. Every choice feels like you’re making progress towards an end with clear consequences of either achieving “bad” or “good” endings. Some of the endings are your standard “happily ever after” fare, but others veer off into the meta.

lol…

There are other little meta-story crumbs scattered throughout the game that have led to fan theories and speculation. Some fans think that, within the game’s fiction, only a few of the characters are “real people,” and that the others are all AI. Sometimes there are dialogue options that let you ask about “the game,” and one character will comment apropos of nothing that you shouldn’t stay up late playing the game. Another character seems to know who’s an NPC and who isn’t.

There’s an allure to these conspiracies that are undoubtedly tied to how invested we are in technology and especially on how increasingly dependent we are on hidden algorithms. Technology sits on a thin layer above everything we do, including romance.

In Naomi Kritzer’s excellent “Cat Pictures Please,” the winner of the 2016 Hugo Award for Best Short Story, a benevolent AI struggles with existential quandaries along with whether or not to be active or passive. It tries to use its digital omnipotence for good, manipulating data to try to improve the lives of its chosen beneficiaries. “Look, people,” the AI says. “If you would just listen to me, I could fix things for you.”

In stories featuring benevolent AI, this seems to be the role they commonly play: of caretaker, friend and, sometimes, lover. Like any relationship, that’s when things get messy. It makes us question what makes a relationship tick, how to relate to another being, and even what love is. Can something that’s not human truly consent? Can you separate consciousness and identity from something like sexuality? In Julia Elliott’s “The Love Machine,” part of her anthology The Wilds (2014), a robot has everything from sonnets to history books uploaded into its brain. It falls in love with various items and people, each time expressing love in differently gendered ways as it attempts to reconcile what it means to be a sexual being.

Can you separate consciousness and identity from something like sexuality?

Whether it’s golems or Frankenstein’s monster or Star Trek’s Data, people have played with the idea of what it means to create an artificial being. As we consider the possibility of a post-singularity world, it’s impossible not to shift around the pieces of how humans might fit in such a world.

One popular theory surrounding MysMe is that 707, a supremely caffeinated hacker, might have been the one to design (either alone or with the character Jumin) the AI in the chat room, possibly as companions or in memoriam of friends who have passed on. There’s also the theory that 707 either created the game or is aware that you’re playing a game, even when you reset. There’s something very relatable about the idea of someone using technology to cast the die over and over again, hoping for a better outcome or to trying to control variables in an uncertain world.

All of these theories have, of course, stoked the fires of fandom in various pockets of the web as players compare results, post conversations, and even look for clues linking MysMe to previous reality-bending games by the same studio, Cheritz. There isn’t too much textual evidence (after all, all the characters appear in the flesh, so to speak, in cut scenes throughout the game), but it doesn’t prevent people from wondering what if? The idea that some of these characters might be AI—with all the accompanying ramifications—makes the world just that closer to our own.

///

Header image via Kotaku

The post Mystic Messenger and the power of texting games appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 27, 2016

Show your support for next year’s smuttiest FMV game

The Chuck Tingle adventure game is now looking to be “Kickstarted in the Butt.” If you’re not familiar with Chuck Tingle this will all come as quite a shock. He is perhaps the internet’s best supplier of smut, writing short erotica with titles like “My Ass Is Haunted By The Gay Unicorn Colonel” and “Pounded In The Butt By My Own Butt.” I promise you this is real (and I can also promise you that it is glorious).

Earlier this year, game maker Zoe Quinn hit up Chuck Tingle over Twitter, asking if he’d like to make a game with her. Under an hour later, he was shooting off game ideas at her left, right, and center, all of them utterly ludicrous and filled with many butt-pounding possibilities. That’s pretty much the story of how the Chuck Tingle adventure game came to be.

sexual situations can be covered up with the game’s Kitten Mode

“Project Tingler,” as it’s currently codenamed, is looking to bring the campy, animal-headed gay love stories of Tingle’s books to videogames. And what better way to do that than combining FMV and dating sims: the two formats in the medium that are most associated with cheesy, low-rent erotica. As seen in a previous Vice documentary, shot during the game’s early production, it’ll feature a Unicorn Butt Cop that wields a dildo like a truncheon, and something called a Vampire Night Bus. There’s also a man-gorilla who, it seems, you will play as, in search of your “cute son” Jon. In doing so, you’ll apparently be sucked further and further into the Tingleverse, where I imagine a whole menageries of people-creatures scream out in ecstasy as their butts are pounded.

I’m probably overselling the amount of butt-pounding that’ll actually happen in the game at this point. Despite the overt sexuality of the game and its source material, the creators insist that it is actually about “positive sexuality, self-acceptance, love and personal growth.” Given that it features real actors, and is not intended to be pornographic, you should probably only expect the game to pound your imagination, then.

There will be seduction mini-games, however, it seems they will only involve some kissing as you try to “prove love is real” to the loveless characters you meet. And if you feel you can’t even handle that much action then any sexual situations can be covered up with the game’s Kitten Mode, which as you’d expect, lets you watch some kittens frolic instead. Every game should have a Kitten Mode.

The Kickstarter that launched yesterday is intended to fund the rest of the game’s production—filming it, coding it, and releasing it. So far, the team has spent time experimenting with the tech and shooting process to get it all where it needs to be, and have prototyped a level that meets their standards. Using this is a keystone, they hope putting together the rest of the game won’t be a hassle. When the game is finished, it will be released using a “pay-what-you-can” model, meaning that it’s free to everyone but you can put some money upfront if you’d like to. It should arrive in 2017.

Find out more about Project Tingler and support it over on Kickstarter.

The post Show your support for next year’s smuttiest FMV game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Along Came Humans wants to make colonization great again

What if Spore (2008) hadn’t been a complete and total letdown? What if Sim City took to the stars, with colorful aesthetics a la Kerbal Space Program (2015) and a friendlier, simplified interface? What if a smart, streamlined game could offer you all of that and more? Along Came Humans, created by Tim Aksu of Pelican Punch Studios, is promising that.

The goal is simple: colonize a planet. Then colonize another planet to bolster aforementioned planet’s diminishing resources. Streamline. Reorganize. Rinse. Repeat. According to Asku, your colonies will demand a larger variety—as well as a higher quality—of goods as they expand. Your job is to establish product chains and routes of transportation, and, overall, keep citizens happy. Asku outlines the infrastructure system here:

“The player will be able to establish trade routes between planets with freighters. They’ll give the freighters orders to shuttle goods around from planet to planet. You could turn some smaller, less desirable planets into Mining colonies and ship those raw resources to your manufacturing planet. Finally, you’d transport these manufactured goods to the colonies that demand them.”

As we know all too well, humans affect our environment as much (or perhaps even more) than it affects us. These uniquely Anthropocene changes are present here as well. Three types of planets determine environment, needs, and manufacturing opportunities: Ice, Forest, and Desert.

a delicate juggling act with planets, ecosystems, and entire civilizations in the balance

Your choices in industry can affect a planet’s climate—for example, making too many factories on a forest planet will turn it into a harsh, dry Desert planet. Alternatively, Ice planets can melt into a forest planet (which would seem like a victory, but you’ll still have to completely overhaul your resource management). Factions will arise based on conditions and constructions made on the planet. These factions currently include Industrial, Mining, Residential, Agricultural, Science, and Outlaw.

Don’t mistake this game’s cuteness for simplicity—very complex structures, which can be seen on the TIGSource thread—ensure that this society simulator, like its predecessors Civilization and Sim City, will be rife with constant choice and consequence.

Aksu maintains that there is no “victory” condition or endpoint to the game. The real victory here is that you get to play God, and get a decent exercise in interplanetary economics, with little real-world repercussions. Maybe we should avoid these cherubic planet’s entirely. But that’s the point of Along Came Humans. It’s like looking in a mirror. Because it’s such a delicate juggling act with planets, ecosystems, and entire civilizations in the balance, Along Came Humans may be more aptly titled Along Came Humans … And Then Everything Died. Take notes.

Look for Along Came Humans on Steam sometime soon. In the meantime, keep up with the TIGSource thread .

The post Along Came Humans wants to make colonization great again appeared first on Kill Screen.

Here it is, the latest nostalgia ploy for the Tsum Tsum generation

One of my favorite things to see compared are Funko POP! figures (of the United States) with Good Smile’s Nendoroids (of Japan). The two are at once comparable—both being a popular series of uniformly designed figures—but also incomparable. POP!s are chibi (small), cheap, and most of all: ugly. While Nendoroids are also chibi, a bit more pricey, and most of all: actually really cute.

When put side by side, the cuter figure is always clear. I’ve always taken it as a sign that my fellow Americans don’t know what cute means. But with World of Final Fantasy, the latest JRPG clout of nostalgia-baiting from Square-Enix, maybe the “I don’t know the basic definition of cute” epidemic is more widespread than I originally feared.

This dissonance of perceived cuteness popped in my mind as I played World of Final Fantasy. Playing it was fine, if not banal in terms of character design for the chibi-iterations. It reminded me of another fan service-oriented game from the Final Fantasy squad that carried a chibi-fied design: Theatrhythm Final Fantasy, the surprisingly great rhythm game series for the 3DS. Theatrhythm and World are two sides of the same coin: both relying on heavy-handed nostalgia and the player recognizing the familiar streams of characters and enemies that cross their path, but boiling down to one real thing: being cuter than their predecessors. Or in World’s case, trying to be cute and failing (in most cases).

They stack on your head like Tsum Tsums

In summary, World of Final Fantasy is a Mirage (or monster) collect-a-thon like Pokemon, wrapped into a tidy JRPG. The battles are quick and satisfying, with plenty of complexity through the ever-befriendable Mirages that you can summon to your beck and call. Plus, they stack on your head like Tsums Tsums. The game has areas that are both familiar and new to players of the sprawling series, though with not much exploration to be had. It’s an enjoyable, if a bit too familiar, romp through Final Fantasy history.

And there will be people that think the stout, droopy-eyed iterations of beloved characters like Cloud and Cecil are cute. I’m not one of them. At least, World of Final Fantasy isn’t fully strapped to its ugly chibi side. With merely the tap of a button (or two, to be exact), you can switch back to the “normal” sized versions of your sibling heroes. The overly-buckled, lanky, spiky-haired characters we’re used to, with impeccable character design by Tetsuya Nomura (of Kingdom Hearts fame).

Chibi-fying the heroes of our favorite games isn’t going to instill life into the series, or even necessarily bring in any newcomers. It’ll just make us fondly remember the much better, and more adorable, games that have come before it. But I guess that’s not the point. It’s the same reason Atlus’s Persona 4 (2008) had a couple of eyebrow-raising spin-offs to capitalize on their popular team of detectives. World of Final Fantasy, like last year’s Persona 4: Dancing All Night, is just another excuse to round up the gang again. But after hours of playing it, I just wished it was a port of the arcade-bound reboot of the PSP fighting series Final Fantasy Dissidia instead. Or another Theatrhythm, I’d take that too.

World of Final Fantasy is available now for PS4 and PS Vita for $59.99.

The post Here it is, the latest nostalgia ploy for the Tsum Tsum generation appeared first on Kill Screen.

Representing depression through game mechanics

There is a point in the depths of depression where you will begin to drown in your garbage. I don’t mean that as metaphor—I mean literal garbage. Unwashed dishes, dirty laundry, bags of trash, boxes from take-out for all the times you couldn’t find the energy to cook (which is every time). And, of course, so many empty wine vessels that you feel tempted to lie—even to yourself—about how many there actually are. In Depression Presented Ludically in the Style of a Videogame this is the point where you fall off the screen.

the eerily slow fall back into the abyss

While many games have tackled mental health issues in some form or another, this is usually linked to some narrative, a character who is struggling. Depression Presented Ludically in the Style of a Videogame is unique in that it is really just about depression as a game mechanic. The approach is simple—so simple that you don’t expect it to be accurate. You are given three keys: left, right, and up. The screen moves up, you must jump onto the platforms to avoid falling off the screen. But if you miss, the fall is long and slow, leaving minimal time to get back above the line.

The most frustrating part is that in every playthrough there will be a platform that you simply cannot reach. The mechanics of the game just do not allow it, and you must fall. And every time you fall a nasty message appears. “You suck.” “Stop trying.” This is what it feels like. The tired climb, the obstacle too great, the eerily slow fall back into the abyss. Overcoming depression is never a straight shot upward, and Depression Presented Ludically in the Style of a Videogame represents that.

[image error]

I would not say it’s a game without hope, however. It’s sad and it’s frustrating, and if you have depression, it may hit almost too close to home. Yes, you will fall, over and over and over. And yes, it will suck. But the game always starts over, and you get to try again.

You can download Depression Presented Ludically in the Style of a Videogame here

The post Representing depression through game mechanics appeared first on Kill Screen.

Battlefield 1’s tiny handgun is here to humiliate you

Picture this: you’re in the Battlefield 1 open beta. Chaos is happening all around you. Buildings are falling, gunshots are whizzing past your ear, narrowly missing. The fear of an airstrike or mustard gas bombing always looms in the background. As the action crescendos, an enemy jumps out of a bush, and kills you with a gun no bigger than a credit card. A fucking Kolibri.

The 2mm Kolibri is a very real, very tiny handgun—first manufactured in 1910, it remains the world’s smallest centerfire cartridge. The name Kolibri literally means hummingbird, although I would argue here that the gun’s avian counterpart remains the swiftest of the two. The puny pistol weighs all of a few grams—notoriously inaccurate, it could barely penetrate pine board if you were lucky enough to hit anything.

The puny pistol weighs all of a few grams

The Kolibri 2mm is the latest in a long line of videogame weapons and tactics solely manufactured for “disrespect.” In Counter-Strike culture, disrespect is a way of describing an overkill—a dance of sorts, toying with prey that is so clearly doomed— that it is reduced to pure spectacle for the other team.

Concepts of “humiliation” and “disrespect” in Counter-Strike have been around from the start in 1999: when an opponent is defeated so easily, or in such a hilarious manner, that the overkill is deemed “disrespectful.” Depending on who you’re playing with, it’s an integral part of competitive multiplayer, or a childish practice that will get you banned sooner or later. If you’re unfamiliar with the concept, here’s a good place to start.

Although video footage of Battlefield 1 reveals that the Kolibri is not a player’s first-choice weapon (unsurprisingly), they do seem to have some fun with it when forced to:

The Kolibri 2mm “Hummingbird” is yet another example of Battlefield 1’s outrageous, dramatic, take on total warfare. While the series has grown less “historical” over time, it seems to only be getting more silly—and, coming from a history buff, that’s exactly the way it should be.

The post Battlefield 1’s tiny handgun is here to humiliate you appeared first on Kill Screen.

Manual Samuel makes a slapstick comedy about being alive

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Manual Samuel (Windows, Mac, Xbox One, PS4)

BY PERFECTLY PARANORMAL

Manual Samuel could be described as QWOP (2008) with a story. It’s about a man who is hit by a truck, dies, and is then resurrected to have you controlling all of his bodily functions. While walking, Samuel’s spine may suddenly collapse, requiring you to press the button that snaps it back in place. You must remember to breathe, to blink, and try to aim Samuel’s urine into the toilet bowl. It’s perhaps a crime against videogames that Manuel Samuel isn’t labelled a “walking simulator” on Steam, given that it’s one of the few games that actually has you operate every step. Its sillier comedic moments will fall flat for some, and there’s certainly something to be said about its perspective on disability, but Manuel Samuel holds up for its playing time (even if the dude’s spine doesn’t).

Perfect for: Lazy heads, mouth breathers, the dead

Playtime: Two hours

The post Manual Samuel makes a slapstick comedy about being alive appeared first on Kill Screen.

Owlboy is a masterful tale of transcending disability

My girlfriend speaks softly. She’s a ghost on the phone. If you ever met her in person, you’d lean in a little when she introduced herself. You could say it’s her personality. But you’d only be half right. The other half has something to do with a very large truck that collided with her small body when she was seven, leaving her in such a state that the doctors who treated her became locally famous. While the miracle docs lined up for pictures in the newspaper, Erin was still unable to communicate; it was years, she tells me now, before she could speak loudly and clearly enough for people to understand. But overcoming her disability didn’t erase its traces. 25 years after the accident, she still speaks in the hushed tones of a frightened child, often loud enough only for herself to hear.

My dad was about 40 years older than Erin when he had his own accident. We were together in the van: I walked away without a scratch, but he never walked again. Like Erin, he was never totally independent after that. Though it would be years before one of his lungs gave out, softening his own speech and leaving him attached to oxygen tanks, the intervening time taught us both that to be disabled is already to lose your voice. People will talk down to you, and not just if you happen to be in a wheelchair. They will decide your limits, and if you’re lucky, they’ll pretend not to be frustrated when you fail to meet them.

to be disabled is already to lose your voice

Worse, people will talk for you. Sometimes this is necessary, and with close friends or a loving family, it doesn’t have to involve a loss of dignity. But not every family is held together by love, and not everyone has friends. If you’re not among the lucky, the person that cleans and changes you might be the only voice you have. And an abusive caretaker—whether it be a teacher, nurse, or parent—is worse than a prison warden for the disabled person that has no one else to fight for them. For the mute child, who has never known anything else, life itself becomes a kind of solitary confinement.

///

When we first meet Owlboy’s young protagonist, Otus, he is being talked at by his new mentor Asio. Otus can’t speak, so as in every other conversation in the game, he participates through a set of remarkably articulate facial expressions and body postures. Around Asio, Otus spends most of the time with his owl cloak wrapped tightly around himself, staring glumly ahead. “In time,” the imperious Asio says, “I will mold you into the spitting image of myself.” Otus just fidgets.

Asio’s expectations turn out to be higher than his young adept can meet. When Otus struggles with his studies, Asio makes his disappointment known and transfers him to manual labor. When Otus has trouble flying for the first time, Asio berates him: “Most students pick this up instantly.” Eventually he gives up on Otus completely. He tells him to go talk to the townspeople to “ask them what they think about you and your ineptitude.” At this point things get strange. As Otus trudges along, the world goes dark and begins to splinter into pieces all around him. The people we will later recognize as his friends manifest as cackling ghouls that mock him as he strives, with characteristic doggedness, to carry out this most degrading of assignments. They encircle the young owl as the world falls apart; he can only cower until the nightmare is over.

It is striking, to say the least, that a game which has the levity and freewheeling inventiveness of a Studio Ghibli film introduces its hero with a sequence of cold abuse. But this is the unlikely balance that Owlboy achieves. From its unforgettable opening sequence to its equally devastating conclusion, the game never lets us forget that its hero is an unusually vulnerable one. He can’t even defend himself when the local owl bullies—cheekily named Fib and Bonacci—tease him. Nor does Otus gain fabulous new powers as the story goes on to deal with all the strife; the most he can do is stun foes with a stylish twirl of his cloak and escape.

What Otus gains instead is friends. His three regular companions can do all the things Otus can’t—blast the bad guys, ascend the waterfall, communicate—as he tirelessly shepherds them around. It is a brilliant twist on the classic Metroidvania format: instead of finding the grappling hook you need to cross that uncrossable ravine, you go and grab a spider to spin you a rope. But it is also an insightful illustration of how the abilities of the disabled depend on those around them, as Otus’ range of motion and ability to resist danger waxes and wanes over the course of the game.

The silent protagonist is not, of course, a new idea in videogames. On the contrary, we have become all too accustomed to inhabiting the stoic avatar that is less “everyman” than “no man.” In the Doom or Dark Souls games, where your character is the plaything of forces beyond their control, it makes narrative sense for them to stay quiet. And those military shooters that want to capture a certain ideal of American masculinity—the strong, silent, murderous type—also have a kind of justification. But just as often, it is a cheap way of forcing the player’s empathy by making them identify directly with the blank avatar. It is far more difficult to create a character that is both self-sufficient enough to communicate and be relatable enough to inhabit.

Otus is presented as an agent, not as a victim or a puppet

This points to one of D-Pad Studio’s many outstanding accomplishments with Owlboy. Otus is as instantly likable as any of the bullied kids we’ve encountered in other stories. But since most of us will be unable to sympathize with his particular handicap—and since that handicap is consistently highlighted as the adventure progresses and new conversants emerge—there is a distance between us and the owl boy that makes us root for him, and care for him, even as we are the ones in control of his actions. Otus is presented as an agent, not as a victim or a puppet—but his agency is fragile, contingent. By not allowing us to know what he is thinking, the game paradoxically makes the protection of his interior self that much more important.

This identification with the game’s hero is expertly facilitated by D-Pad’s artists, who have a particular talent for conveying personality through small details of character appearance and movement. Memorable as he is, Otus is only one of Owlboy’s large and vibrant cast of characters, none of whom could be confused for each other. There is Mandolyn, the musical light of Otus’s home village of Vellie, who serenades our protagonist at the outset of his journey with an adorable bob of her ovaline head. There’s Twig, aka the Troublemaker, who wears a buff spider suit and out-webs Peter Parker in order to hide his embarrassing heritage as a lowly stick insect. And above all there is Otus’s best friend Geddy, who dresses like a certain famous Italian sidekick and waves his arms around like a giddy ape when he gets excited.

But the visual language of Owlboy’s characters is outdone by the grammar of its world. Owlboy has been in development for nearly a decade, and in that time it has already won numerous awards, and garnered accolades for its gorgeously pixelated 2D world. They are all warranted. But what really stands out across the game is how this lovely world locks, slots, and snaps together.

True to its Metroidvania heritage, the game has Otus and his pals engage in a mixture of puzzle-solving, exploration, and surprisingly meaty combat. (Those underwhelmed by the pop of Geddy’s pellet gun in the Owlboy demo will be pleased with the shotgun-wielding pirate that supplants him.) But most memorable are the ways Otus must interact with his ever-shifting environment to progress through areas: squishing rainclouds to turn snarling firedogs to stone, or twirling balletically on enormous screws to open distant doors. There feels like an endless variety of these bizarre challenges, and the fluid, dynamic interaction of the game’s moving parts makes it a joy to carry out every one of them.

This joy is aptly captured in Jonathan Geer’s soaring score, which puts most other videogame soundtracks in recent memory to shame. This is genuine composition: there are no pseudo-nostalgic synth reveries or lazy ambient drones filling time here. Just listen to the game’s theme—buoyant, boundless piano arpeggios fall into one another as warm strings and French horns paint a vivid picture of this blooming world. Even when Geer integrates chip music in the theme for Otus’s home town of Vellie, he is able to string together a marvelous contrapuntal dance from the simplest of components, mirroring the game’s own contemporization of the 2D platformer.

It is important to emphasize this in particular—Owlboy uses an older model of videogame, but it is not a “retro” title in the sense that its meaning or pleasure derives from nostalgia. On the contrary, the game’s sheer creative energy makes it feel fresher than most modern titles. That this energy was sustained over the course of nearly a decade of development, and that the end result is so perfectly cohesive, is something of a small miracle in a difficult industry. And it is hard to imagine that anything could inspire such devotion from D-Pad’s small team over such a long time other than the plucky owling whose story this ultimately is. The world belongs to Otus; the creators enabled him, but the player’s privilege is to set him on his way, and watch him rise.

///

Owlboy takes shape as an ascent. As you battle the mechanical pirates that threaten your kind, and dig into the owls’ past, you rise into progressively higher layers of this skyworld: Tropos, Strato, Mesos …This vertical directionality is paralleled by the increasing mobility and strength of your group. But when you ascend to the final and highest area, gravity takes its revenge: the air becomes too thin for Otus to fly, negating his most significant ability in the game. Otus’ companions, eager for answers and resolution, hurry ahead in spite of the fact that the owl boy can no longer keep up. And so Otus is left alone once again, hopping carefully over gaps between platforms like the 1980s had never ended.

This is a subtler moment than it seems. We’ve all seen the movies where the hero is drained of their powers at the critical moment, but wins anyway. When Otus loses the basic power of flight, however, his friends don’t immediately rally around him or bolster him up the way we might expect. Their interest shifts almost imperceptibly from the caravan to its destination. Certainly no one would say Otus is a burden, if we could step into this world and ask them—but he’s also no longer leading the caravan.

exceptionally well-crafted and tasteful

It is perhaps the most primal and enduring fear of the physically disabled person that they will be left behind like this. And the fear is justified. My girlfriend describes most of her childhood in these terms: friends walking on ahead because her bad leg wouldn’t let her keep up, or worse, teachers berating her in the middle of a crowded playground for episodes of temporary paralysis. I am no better than these people: as a teenager, I remember walking 10 steps in front of my dad’s wheelchair when we went to the movies. To say that it was unconscious, even instinctual, scarcely makes it less abhorrent.

But unlike owls, we have been gifted by nature with the capacity to transcend our most abhorrent instincts. We have the ability to befriend those who genuinely need friends, and to encourage others to do so through works of art that depict the joy and power of companionship. Owlboy is itself as joyful and powerful an example of such art as I can recall. That it also happens to be an exceptionally well-crafted and tasteful videogame made by a very small group of people may not entirely be a coincidence.

As for Otus—he eventually regains his ability to fly, and the support of his comrades. At the peak of everything, the pack faces an unexpected (and unexpectedly difficult) final enemy who throws into question the history of the owls, the purpose of the quest, and the fate of the cosmos as a whole. That the game chooses to go to the audacious physical and metaphysical heights it does in these final moments might be surprising, given its overall focus on smaller matters of community and tactile problem-solving—but it also feels entirely earned, and confirms the player’s sense of unexamined depths beneath this world’s beautiful surface.

Or maybe this isn’t the right language for Owlboy. There are no depths in two dimensions—only degrees of altitude, currents of resistance, vectors of descent and lines of transcendence or transascendence. These compose the true vocabulary of the game, and its truest joy. You can master this vocabulary without being able to speak a word. All you need is a computer, a bit of imagination, and two working hands. But if your hands don’t work so well, hit me up. I’ll play through it with you.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Owlboy is a masterful tale of transcending disability appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 26, 2016

Now you can hang ICO and Shadow of the Colossus paintings on your wall

There isn’t a lot of videogame art I would hang on a wall. In fact, to date, there is only one piece of videogame-related artwork in my house, and it’s Judson Cowan’s rendition of Lordran from Dark Souls (2011). Now, I think may have found it some company.

Cook & Becker, an art dealership, is now selling prints of the paintings that Japanese game director Fumito Ueda did when conceptualizing ICO (2001) and Shadow of the Colossus (2005), limited to 500 copies each. You’ll recognize the painting for ICO if you live in Europe or Japan, as it was used as the game’s cover art—America got something much, much worse.

It takes its cues from the stylings of Italian surrealist painter Giorgio de Chirico, in particular his painting The Nostalgia of the Infinite, with its silhouetted couple, yellow landscape, and towering arches. That print is available unframed for $95.

The other print, titled “NICO” as that was the working name for Shadow of the Colossus, is of a painting I haven’t seen before. Cook & Becker give reasons as to why that’s the case: it was never used outside of Japan, where it was only used as the art for a DVD that showed the first in-game footage of the game for people who pre-ordered it.

evocative of the symbolism in the game

It’s similar in style to the ICO painting but lacks some of its finesse in its lines, and the colors aren’t nearly as striking. But it does have a similar subtlety in that, if you weren’t familiar with the game, you probably wouldn’t guess that it’s anything to do with videogames. There aren’t even any colossi in the painting, it instead drawing focus on the central tower and its magnificent bridge, overlooked from a cliff edge.

The detail that stands out is the elegant shadowing of that bridge. The sloping supports are extended in their shadow form by the low tilt of the sun, which is perhaps meant to evocative of the symbolism in the game: as Wander slays the colossi, he is invaded by a darkness, and looks more and more sickly as he progresses. You can grab that unframed for $95 also.

The paintings are available on “museum-grade giclee print” and hand hand-penciled edition numbers on each of them. And, as said, there are only 500 of them each. Might be the ideal thing to get before Ueda’s next game, The Last Guardian, comes out on December 6th.

The post Now you can hang ICO and Shadow of the Colossus paintings on your wall appeared first on Kill Screen.

Game Boy-style visuals are too good at being creepy

The Game Boy is an icon of ’90s innocence. It’s a kid playing Tetris (1984) while sprawled across their bed. Or a bunch of kids trading Pokémon (1996) in the sun with a Game Link Cable. Nintendo’s original grey handheld is not typically a vessel for horror. But you try telling that to the people who participated in the fifth Game Boy Jam earlier this month.

The challenge of the GBJam is to create a game with the small resolution and limited 4-color palette of the original Game Boy. That means there’s a bunch of green-and-black games ready for playing right now. Most are charming little things, like planting a garden with a smile, and helping a seal eat some fish (truly adorable). There’s also one about throwing babies at a wall to paint it with their blood—that’s an exception.

Don’t be so paranoid

But, as it’s the season, it looks like some people decided the effort was also ripe for creating something a little spookier. And those pixels we usually see as so friendly take to it surprisingly well. It might even be their true calling (black and green make for great witch colors, after all)—I have hard EVIDENCE:

Evidence #1: EXIT

This is a game about being lost in a multi-storey car park. OK, that’s not true, but it does parallel the experience of hunting down the glowing “EXIT” sign when you’re lost amid the concrete. EXIT is actually a puzzle game in an industrial facility. You spin valves and smack laptops to find keys that open doors. Nothing creepy in that, except the dim wailing in the background, the steady rhythm of breath, and your flashlight that regularly cuts out.

As with other pixelated horror games (namely IMSCARED – A Pixelated Nightmare), EXIT makes the most of its lo-fi trappings to create ambiguity in its visuals—you might think you saw something in the dark but you didn’t. Don’t be so paranoid.

Evidence #2: Ultimate Evil

There’s a Resident Evil game on the Game Boy Color but there isn’t one on the original Game Boy. Which means Ultimate Evil gets to corner the market in green videogame zombies. Oh, wait, scratch that. What it does do, however, is bring all the dramatic door opening and clunky controls of the first Resident Evil to the Game Boy (well, sorta). Every time you broach a corridor and meet its corner, you have to jam a button and wait for your character to appreciate every new angle as they slowly turn, hoping that a zombie isn’t already nibbling on your ear. Silly, old-fashioned, and unnecessary, sure, but it helps to up the tension.

The Game Boy palette brings a sickly, poisoned feel to the architecture of its sparse mansion. While the pixels fidget into position as you approach them from a distance. What I think I like most about Ultimate Evil is the way the zombies look when they get right up close to you. You can’t see their faces from afar, and so you can only project a visage of horror onto them. But then, when they’re up in your face, they pose for you, trying to look ghastly. Freeze frame them right there and you couldn’t tell whether they’re singing you “Happy Birthday” or about to gnaw on your face (I guess if it isn’t your birthday you can guess the answer).

Evidence #3: Coward Town

My anti-virus program says that Coward Town is too dangerous for me. There’s nothing scarier than that. I did get around to playing it eventually and it confirmed my suspicions. The creator of Coward Town, going by the name “Swofl” on the internet, is no stranger to making pixels creep people out. They did it with the horror game Lasting and they did it with Gallergy. Coward Town has more in common with the former given its look: made mostly of animated squares and only a handful of colors.

Its a game at unease with its world—just as the characters are (as implied by the title)—as made visible by the arrangement of pixels, which make the ground looked frayed, or sometimes that its keeled over completely, consumed by a black void. Objects aren’t clearly defined; people hide away by themselves in rooms; the architecture looks like it’s in ruins; the trees are bare and gnarled. This is a pixelscape in abandon. Exploring it feels uneasy.

You can find a load more games in this style over on the GBJam 5 page on itch.io.

The post Game Boy-style visuals are too good at being creepy appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers