Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 33

November 1, 2016

Drone Tone lets you summon dark, witchy sounds

Conor McCann has made lots of wonderful digital toys recently. Black Gold was one of them—a game that let you ruminate on life while sipping cold beer with a friend under the stars. The Echo Initiative was another, which had you keep a lost satellite company as it drifted forever through space. There’s also the reel of playful interactions that McCann made for the Pippin Bar ‘GAME IDEA’ Game Jam, the unimposing frolic that is a few ideas in no particular order.

Now McCann has released a small commercial project called Drone Tone for Halloween. It’s an “ominous sound toy,” meaning that it fits in with everything else that McCann has made this year. The idea is to arrange circles onto points around a shape—with each point having its own distinct sound—in order to create a creepy soundscape. You can control which sounds play but not how often they chime in.

summoning spirits or something darker using this sound machine

Part of me wishes that I could have total control over how these sounds collaborate. But another part of me enjoys the fiction it implies. It seems no accident that some of the shapes appear like a witch’s hex, as if you’re performing a ritual, summoning spirits or something darker using this sound machine. That the sounds seem to decide when to chime gives them a sense of life; as if they’re callings from the other side of the spirit realm or something. The trailer, as you can watch below, feeds into this idea.

Once you’re satisfied or at least finished playing with a certain shape and its sounds, you can hit a button so that another shape warps into view, bringing with it a new set of sounds. The range of sounds on offer should be ample for you to create the sense of dread you’d want from Drone Tone. There’s a decent mix of pulse hits, industrial wails, and low rumbles, and their default bpm is plenty slow enough for the job.

I could easily imagine some of the arrangements I came up with ramping up the tension during a game of hide and seek between killer and victim in a horror movie. Drone Tone seems especially good at invoking slow movements made of terror—Freddy Krueger dragging his razors across the metal sheets of an abandoned factory type shit. If you want to tap into your darker side then it’s a surefire way of doing that.

You can purchase Drone Tone over on itch.io for Windows and Mac. It’s also available for iOS on the App Store and for Android on Google Play.

The post Drone Tone lets you summon dark, witchy sounds appeared first on Kill Screen.

Help fund your own terrible death in Agony’s bloody vision of hell

It’s been a while since I’ve seen a warning label at the beginning of a videogame trailer. “WARNING: This trailer contains violent footage and flashing images that some may find disturbing.” That’s how the Kickstarter trailers for Agony open up, before each of them start smashing heads open with fists—one is two minutes long, the other 16 minutes long, select your poison.

That’s the kind of warning I mostly associate with Resident Evil 2 (1998). That game came out a tender age for me, eight years old, when I wasn’t allowed to play horror games and therefore grew an obsession with imagining what horrendous things my parents were hiding from me. Given any opportunity to stare at the back of a box for a horror film or game, I’d read the summary over many times, and press my eyeballs against the tiny images so I could lock it all into my brain.

a man-headed baby is smashed to death with a rock

Some of the same tics from that time come back to me when watching Agony‘s trailers—eager to know what the heck is going on in its twisted depiction of Hell, but not able to see the full vision. The latest trailers creep slowly across structures made of bone and sinew, carpets of skulls, lined with bodies both dead and dying, past ritualistic chambers throbbing with gore and electricity, through tunnels where a man-headed baby is smashed to death with a rock.

All of this is some properly horrendous shit and I am really into it. Madmind Studios, the people making Agony, show that they’re not holding much back. See the pregnant women cut open, their dead children still hanging from their cords like some kind of gross Christmas tree decoration. It’s not that I go hunting this stuff down to satisfy some deranged bloodlust (although I guess that’s a part of it for all of us), it’s that I believe if you’re going to do Hell, you should go all out. Agony seems to be doing that.

Now that videogames are long past the days of Jack Thompson’s censorship campaign, they’re getting more confident with depravity and how to contextualize it—you know, so it’s not gratuitous or plain offensive. It’s still too early to truly celebrate Agony’s depiction of terror and suffering in Hell for this, but it’s a vision that promises a flesh and blood world that is perhaps more realized than any other in the medium. That’s enough for now.

It’s also for that reason it’s a bit of a shame to see the player’s objectives punched out in text at the top of the screen, rather than trusting them to work things out by reading the environment. But there’s time for that to change still. It seems that, should Madmind get the $66,666 to fund the rest of Agony‘s development, it’ll arrive sometime next year.

You can find out more about Agony and fund it over on Kickstarter.

The post Help fund your own terrible death in Agony’s bloody vision of hell appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Endless Forest’s playful online world could get a remake

Tale of Tales is looking to remake the very first videogame they made as a collective—comprised of married couple Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn. They’re trying to raise €40,000 on Indiegogo in order to update the dated technology that runs the original version of the game so that it may live on for another decade.

The game is called The Endless Forest (2005), which is an online multiplayer game without any clear goals, and where each player is represented by peculiar deer with a human face inside a peaceful forest. Most notably, communication between players is limited to gestures (there’s no chat), and the playfulness and meaningful connections this creates between them actually inspired the multiplayer component of Journey (2012).

“We don’t want to hide it anymore”

There’s also a system that Tale of Tales calls “Abiogenesis,” which allows them to essentially play god, able to alter the world in both mundane and magical ways: they can introduce rain to the forest, make giant flowers explode, turn everyone into frogs, make statues float, and so on. There are also special events that can be arranged through this system, the players invited to a certain location at a certain time to witness … something. It’s this part of the the game that Tale of Tales considers “a living work of art, a sort of ongoing digital theater,” but unfortunately the current technology behind the game can struggle to keep up with so many players in one place. Hence the call for a remake and the funds to enable it to happen.

“The Endless Forest has been our creative cornerstone and we want to take it further. We don’t want to hide it anymore out of fear that the technology wouldn’t be able to handle an increased amount of players,” wrote Tale of Tales. “And we want to add all the ideas that we have come up with together with the players over the years.”

This move may come as a bit of a surprise if you’re at all familiar with Tale of Tales. Back in June 2015, the studio actually said they were done making videogames. This came after their last game, Sunset (2015), failed to push the kind of sales they needed it to. “There’s barely enough income to keep our company going while we look for ways to raise the funds to pay back our debts,” it read in the announcement. Instead of videogames, Tale of Tales committed to the adjacent of world of virtual reality, bringing the magnificence of Christian art and architecture to the format with Cathedral in the Clouds.

While Tale of Tales isn’t making a videogame, but remaking one, it’s good to see that they haven’t abandoned the medium entirely. They’re looking to keep The Endless Forest‘s remake free still, like the original, but if you do throw some money at it right now you can get 3D models of the deers (ideal for 3D printing, apparently), and upgrade your username to Legendary status.

You can find out more about The Endless Forest and support it over on Indiegogo. You can download and play the original game here.

The post The Endless Forest’s playful online world could get a remake appeared first on Kill Screen.

The technology behind Kubo and the Two Strings

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

A frightened woman crosses a storm-swept sea in a tiny canoe as black strands of windblown hair hit her face. Rain pours down her kimono as her fingers clutch a three-stringed Japanese shamisen. A massive wave looms over her canoe, impressing on the viewer how small and human she looks. The woman strums the shamisen, conjuring a magic flame that cuts clean through the wave.

The opening scene in the stop-motion film Kubo and the Two Strings — created by animation studio Laika and released in August — demonstrates what is possible when creators combine puppeteering with 3D printing and computer-generated imagery (CGI) to transport viewers into a surreal fantasy world.

Kubo and the Two Strings follows a young boy — Kubo — on his quest to find a magical suit of armor worn by his late father. The armor is the only thing that can help him defeat a vengeful spirit from the past. The story comes to life thanks to incredibly detailed visuals that are possible because of Laika’s ability to fuse state-of-the-art technologies with 120-year-old stop-motion filmmaking techniques.

Kubo and the Two Strings demonstrates what is possible when creators combine puppeteering with 3D printing and computer-generated imagery

“In our 10 years, we’ve learned not only are we filmmakers, we’re engineers, city planners, electricians and adventurers,” said Travis Knight, president and CEO of Hillsboro, Oregon-based Laika. “We’re a passionate group of artists who believe that the smallest details help tell the bigger story,” he said.

Laika’s artistic skills and maker-movement determination netted them three consecutive Best Animated Feature Film Oscar nominations for Coraline (2009), ParaNorman (2012) and The Boxtrolls (2014). While the only other stop-motion film to win an Oscar was Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (2005), Kubo and the Two Strings is a strong contender for the 2017 animation Oscar.

To create a stop-motion film, dolls or puppets and objects must be physically moved in small increments between individually photographed frames. This creates the illusion of movement when the photographs are strung together in a sequence. The technique dates back to the late-1800s. Stop-motion animation has since evolved into the age of digital computer animation while maintaining much of its genesis.

Laika leveraged a range of digital technologies to bring its latest stop-motion film to life. Digital compositing, for example, helped blend practical and CG elements together. Fully digital water and sky effects, and computer-generated extras — scanned from real-world models — fill out crowd scenes. Handcrafted puppets made of plastic or clay can now be created with the help of 3D modeling and 3D printers. CGI has become increasingly affordable and can more easily augment physical set designs.

According to Maija Burnett, director of CalArts’ character animation program, the advent of CGI and 3D printing is precisely what has kept stop-motion alive. Not only has it encouraged filmmakers to get more creative with props and sets, she said, it also gives the creators the ability to animate characters and objects more precisely.

“It allows studios like Laika to create films that, for lack of a better word, can ‘compete’ with films produced by the likes of Disney, Pixar, and DreamWorks — while still maintaining and promoting the craft of stop motion,” Burnett said. By adapting technologies and developing new skillsets, Laika is taking stop-motion filmmaking into the digital age, according to Brian McLean, director of rapid prototyping.

Laika is taking stop-motion filmmaking into the digital age

“I was the technical guy bringing this cutting-edge 3D printing technology into this hundred-year-old art form of stop motion,” said McLean, who joined Laika to help make Coraline in 2009 and was in charge of spearheading the film’s revolutionary use of 3D printing for facial animation. Not everyone was on board with moving into the Digital Age right away.

The new technologies caused anxiety among animators and puppeteers because they saw how the advent of CGI replaced many stage jobs in the early 2000s. McLean eventually convinced colleagues that 3D printing wasn’t a threat. Instead, it was a way to keep stop-motion relevant in the digital age and push its storytelling methods forward.

Tackling Challenges with Trusted Tricks and New Technology

According to McLean, one of the biggest misconceptions is that digital effects make stop-motion “easier” to do. On the contrary, one of the most difficult aspects of the film, especially in its opening sequence, was blending the real world objects naturally with the CGI elements into a cohesive world.

“When practical effects are impossible or don’t give us the final performance that we want, only then do we look at CGI, and even then, the effects are always rooted in the physical,” said McLean, describing how Laika augments traditional craft with new technology. It’s impossible to capture real-life fluids like water with stop-motion, for example, since animators can’t position and reposition liquids as they would a puppet in between shots. Laika’s digital animation team set to making the impossible possible, turning to puppeteering techniques for inspiration.

“The water is actually based off the art department photographing black garbage bags with a grid structure underneath them to make it look like it was actual, physical and frame-by-frame controlled water,” McLean explained.

The Future of Stop Motion Storytelling

Stop-motion animation fans have a growing list of favorites, from The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) and Chicken Run (2000) to Anomalisa (2015). New technologies helped stop-motion to not only survive but thrive. The rise of cloud computing, including services like Amazon Web Services, is instrumental in giving animators access to enormous amounts of computing power to render their creations.

New technologies helped stop-motion to not only survive but thrive

For Kubo, Laika had to find a way to realize character designs with detail far finer than the animators had ever worked with before. With the help of Stratasys’ new Connex3 printer, they brought characters like Monkey, with her intricate snow-covered fur, and the centipede-like Moon Beast, their first fully 3D-printed character, to life.

3D Printing Moves Stop Motion into the Future

Kubo isn’t the only recent movie that focused on the latest tech. Duke Johnson, co-director of Anomalisa, also found 3D printing to be the only possible method for his quieter, more subtle stop-motion film. Anomalisa is an adaptation of co-director Charlie Kaufman’s abstract stage play, where the actors sat in chairs and delivered their lines, leaving the rest up to the audience’s imagination. Stop-motion wasn’t a natural fit necessarily, but Johnson and his team weren’t intimidated.

“Since the play’s story wasn’t previously visualized, we thought that opened it up to adding our own twist to it,” Johnson explained. That twist is that the protagonist sees everyone in the world as the same plain white guy puppet with the same voice, until he meets one woman who quite literally stands out from the crowd.

Johnson said that doing justice to the actors’ “incredible, nuanced performances” led the film naturally to 3D printing. They tried other options, like clay, but found that 3D printing the puppets’ faces allowed for the most facial movement. Similarly, Laika used 3D printing to refine Kubo’s facial performances, too. While the titular protagonist in their first movie, Coraline, had 200,000 possible facial expressions, the character Kubo has almost 50 million.

Stop Motion for the Masses

Even as advanced 3D printers become the norm in stop-motion, McLean believes tech can also make stop motion more accessible to amateurs. “You don’t need to have huge fancy expensive cameras or 3D printers,” he said. iPhone apps like Morphi, for example, enable anyone to 3D-scan objects for printing. Even the Stop-Motion Camera app makes it easy to shoot frame-by-frame animation.

“If somebody wants to be an animator,” McLean said, “I recommend they sit and bring something to life — not just make it move, but give it personality. Give it character.” Stop motion requires time, focus and dedication. It takes diligence and ingenuity. According to McLean, each of Laika’s animators work 40 hours a week to produce just four seconds of amazing footage.

Advancements in computing technologies mean tools like 3D printing, CGI, and cloud rendering are increasingly more affordable, accessible and capable. With these tools and what’s to come, anyone pioneering the century-old craft of stop-motion storytelling is just scratching the surface.

The post The technology behind Kubo and the Two Strings appeared first on Kill Screen.

From Darkness, an interactive documentary about African refugees

The keyword for the Austrian art group goldextra is “experience.” The group presented its online multiplayer game Frontiers with a sentence that fed this idea: “Don’t just watch, experience the news yourself.” Frontiers had virtual recreations of spaces in the Sahara, southern Spain, and Rotterdam so that players could get familiar with the environments that formed the refugee’s journey. The virtuality of the videogame format acts as a surrogate experience for the player—the second-best thing to actually going to these locations and speaking to the people there firsthand.

Goldextra’s latest game dives further into this idea. Called From Darkness, it’s an interactive documentary about the displacement of Africans. You play as a mother searching for her lost daughter who was a reporter based around Nairobi. It is there, in Kenya’s busy capital, that you first travel, but soon end up exploring surrounding villages and slum cities as the mother is compelled to discover the stories the media doesn’t cover—those told by street children, NGO workers, and refugees.

certain African events are strikingly under-reported

What’s striking about the environments in From Darkness is how they are constructed through collage: goldextra traveled to Kenya and Uganda for research, gathering over 60 hours of video footage, interviews, and sound that is used alongside photos and news reports to create the walls of its virtual spaces. “We wanted to recreate our research experience as a first-person player experience,” Tobias Hammerle of goldextra told me. You walk around these spaces, triggering interviews to play, talking to looping GIFs of villagers, steadily piecing together a picture of the place.

All the information is almost overwhelming with so many personal stories being told. This seems to be intentional, as near the game’s end the mother has something of a breakdown—the voices and pictures from throughout the documentary all appear at once, overlaying each other as a tremendous cacophony. In this moment she is frustrated that there are so many important and touching stories in Kenya and Uganda that aren’t told by reporters like her daughter and aims to do something about it herself.

The point that goldextra seems to be making with From Darkness is that there are a lot of stories to be told about Africa but a lot of them aren’t given any time by the international media. “When it comes to the African continent, there is a common narrative: crisis, wars and catastrophes,” Hammerle said. “Stories like these get multiplied in the echo chambers of modern media, and then dominate the image we have of Africans themselves: as either victims or perpetrators.”

Hammerle and the rest of the goldextra team were eager to avoid falling into what they call the journalist’s “trap,” by which they are seduced to tell only the most horrific stories to appeal to their audiences. Goldextra’s tactic was to give a voice to the people they met around Kenya and Uganda when they traveled over there in 2012, letting what they said shape the game’s narrative, rather than trying to confirm what they thought they already knew about these local populations.

“isn’t it surprising that we don’t hear much about conflicts like these”

It’s also why Hammerle commits to the idea that From Darkness is an “experience” rather than an “educational” game. The difference being that an experience lets the player come up with their own conclusions from what they’re presented, whereas an educational game might try to push specific lessons about its subject on to the player. The latter is also, arguably, what the media unavoidably ends up doing when it reports on these regions. That is if they bother to report on them at all—one problem that Hammerle is particularly passionate about is how certain African events are strikingly under-reported.

“Ask your friends, for instance, to tell you which war they think led to the most casualties after the Second World War,” he said. “I bet only few would know the correct answer: It was the Congo war, which caused up to seven million deaths in little more than five years. Now isn’t it surprising that we don’t hear much about conflicts like these? I personally think there is a need for some counter strategies against this blatant media silence when it comes to certain topics, not to mention the problematic interdependencies with the West.”

Hammerle and the rest of goldextra hopes that From Darkness will help players to want to find out more about the stories, big and large, that exist in Africa. An interactive documentary can help give more insight into the continent and its people, but Hammerle encourages players to travel there for themselves, to discover new stories and to give them a voice if they can.

You can find out more about From Darkness and download it over on its website.

The post From Darkness, an interactive documentary about African refugees appeared first on Kill Screen.

The ghost of Churchill; or, how to make a wargame

“The cards I throw away are not worthy of observation or I should not discard them. It is the cards I play on which you should concentrate your attention.” – Winston Churchill, 1912, during a bridge game on the Admiralty yacht Enchantress

///

Churchill: The Man

Churchill has been on my mind a lot lately.

It’s hard not to be wowed by the man, his tenacity, his military tactics, his signature three-piece suits. When obstacles arise in my research or when I bump into my wargaming ex-boyfriend, I think to myself What would Churchill do?

I’m not the first American to be fascinated by Churchill, and I certainly won’t be the last. Take it from Mark Herman, who named an entire tabletop game after him:

“I decided to call the game Churchill as it was his voice that gave me the keenest insight into the mind of a world leader at war. Roosevelt and Stalin were the other players in this drama, but they had not left an equivalent written legacy, so it was always Churchill’s voice I heard as I worked through the design.”

Still, I’ve found that however much I might admire the man, it’s hard to take a consistently Churchillian approach in life. Not all social and scholarly barriers can be broken down with a top hat. We can’t all be bold and brave and British, hard as we may try.

What would Churchill do?

I have learned this lesson slowly but surely in the past 18 months while studying Guantánamo and trying to make a game documenting the power struggle in the war courts and the detention facility. It’s a dark world to probe. One respected British legal mind, Lord Steyn, went so far as to call it a “legal black hole.” As a researcher and a civilian, I’ve found that it can be a bit of a swampland. You have to be a bit militant to make sense out of anything happening at Guantánamo, or GiTMO as it’s often called. You have to try to find your inner Churchill.

Things unravel. Partnerships fall apart. For many moons I, a researcher of war, dated a wargamer, someone who could speak about counterinsurgency and chalcogenides and Sherry Turkle all in the same breath. I saw in him a collaborator, a partner in crime and in creativity. We talked about GiTMO, the events and episodes that defined the place, the people, and the policies. I even started to toy with putting a prototype wargame together. In the aftermath, when we ceased being a we, instead of continuing to build my dream wargame, I thought of the 70 episodes of our relationship, moments in time, when certain words had been uttered, when certain cards had been played. I looked at my life, my proverbial deck; bafflement turned into more bafflement, until clarity came.

Churchill : The (Policy) Game

Wargames can be downright Tolstoyan. You can end up in some form of cognitive Siberia if you don’t make an effort to understand the rules. There are so many components. In the wargaming world, some people go gaga over the stickers. Others get their kicks out of cutting counters. Me, I went for the cards.

I grew to love event cards, so much so that I’d often burrow into a deck from a random wargame whenever I wanted an escape from my M.A. thesis on Guantánamo. There was something intangibly magical about them. The cards empowered—made me forget all those hours in middle school that I’d lost trying to draw timelines out perfectly. Maybe it helped that my boyfriend couldn’t always handle the deck. He had mastered so many elements of wargaming, but shuffling wasn’t his forté. It was liberating to have a skill in a world that was so foreign. The idea that history could be jumbled and reassembled gave me this giddy feeling.

this attempt to boil a segment of their nation’s history down

Event cards helped me become comfortable with wargame design. The first deck I really loved and explored belonged to A Distant Plain (2013), a wargame about contemporary Afghanistan. I considered how my Afghan friends would critique the narrative put forth in the deck and the board. What would they think of this attempt to boil a segment of their nation’s history down? Omission, deletion, marginalization, and exclusion—these are issues that always bubbled up in my mind as I shuffled through the deck.

I had mentored a group of Afghan women writers, many of whom were based in Kabul, and I always wondered, if they had been taught wargame design, how might their deck have differed? Instead of having a card devoted to “Koran Burning,” would they have given a card to mark the murder of Farkhunda Malikzada, an Afghan woman falsely accused of burning a Qur’an? As wargame designers Volko Ruhnke and Brian Train crafted their A Distant Plain (2013), which cards had been edited out?

Photo by author of two event cards from A Distant Plain (2013)

In MIT Press’s Zones of Control, wargamer Jeremy Antley explains that “taken together, the board and event cards create a materialistic, skeletal frame upon which the player-driven construction of narrative can attach and mold itself.” I guess what I loved about the strategy and wargames I played is that for each conflict modelled I could imagine different military outcomes. I could build different skeletons. Sitting at a table in Northampton, Massachusetts, I could be the architect of different political realities in a region that mattered to me.

My love for event cards grew, and shortly after playing A Distant Plain, I stumbled across Churchill (2015). Before I get too far into the world of Churchill, I should highlight that its Board Game Geek profile warns that it “is NOT a wargame, but a political conflict of cooperation and competition,” although it did win the 2015 award for Golden Geek Best Wargame. Churchill is distinct from wargames in that it is played as a series of conferences. The rulebook explains that “during a conference you represent one of the Big Three—Churchill, Roosevelt, or Stalin—and your staff (seven staff cards each, per conference) where you nominate, advance, and debate issues.” Churchill, too, consists of event cards, and as in A Distant Plain, they gave me the chance to delve into narrative-building. Again, I pondered what events hadn’t made it into the deck. What episodes in history had Mark Herman left out?

Screenshot of Churchill (2015) conference cards scattered.

Churchill: The Quote That Was Not His

Early August, as I continued with my own research on the U.S. military, I returned to this question of how we might break the history of Guantánamo down into individual episodes. If someone wanted to model Guantánamo, what 50 or 60 moments would make it into the deck? What episodes in the detention facility caused power to shift between detainees, journalists, guards, and lawyers? Tentatively I thought about what source material I might consult to get a comprehensive picture of what detainees, guards, lawyers, and journalists experience.

To get a better sense of what guards at GiTMO witness, I decided that I would do a full and exhaustive reading of @JTFGTMO—all the tweets that had been written for and by members of the military stationed in the segment of Guantánamo responsible for the oversight of detainees. And it was at this moment that Churchill unexpectedly reared his head:

Tweet initially posted on @JTFGTMO, archived on the Wayback Machine

You might chuckle at this quote. I know that I did. I read it out loud to my co-workers at the Harvard Law Library Innovation Lab. This is indeed the man who thought that Nazi leaders should be “shot to death … without reference to higher authority.” I got so psyched about this trace of Churchill that I started tweeting at @JTFGTMO, complimenting them on the motivational quotes. There were others—by Ralph Waldo Emerson, George W. Bush, and Rosalynn Carter, but they all seemed to fall flat in comparison.

Photo taken by the author in October 2016 in front of the Little Cupcake Bakeshop in Brooklyn

Ultimately, the @JTFGTMO Twitter feed offered insight into individual moments of history at GiTMO that weren’t on my radar. But, later in August, something funny happened. Tweets began disappearing from the feed. They went from having 1097 tweets on August 2, 2016 to 901 on August 24, 2016, to 716 on September 7, 2016. Entire months gone—poof. Among the casualties of deleted tweets was my Churchill quote.

Updated screenshot of @JTFGTMO Twitter feed, showing that April 2016 is gone.

Frustrated, I did some digging. There’s another twist here. According to Churchill by Himself: The Definitive Collection of Quotations (2008), the quote can’t even be attributed to Churchill. He never said it. The takeaway: misinformation is a menace. There are still other lessons I learned during my excursion into @JTFGTMO.

I became so unnerved by this whole affair that I wrote the Joint Task Force—Guantanamo. I wanted to know what happened. Why did they delete the tweets? I hesitantly reached out to the Joint Task Force’s media team. Would they answer me honestly? By retweeting their tweets had I triggered the erasure of a military narrative that I sought to preserve? I received the following response from Joint Task Force Public Affairs Officer U.S. Navy Capt. John Filostrat: “The motivational tweets were removed because they had no relevance to JTF-GTMO operations.” I couldn’t help but chuckle. I wondered what Churchill would say about his deletion from the public record.

Photo of the wargame room, where the author collects maps and diagrams of GiTMO and its discontents

Today, my GiTMO wargame is not yet a prototype. I’m still figuring out what sorts of skeletons I’d want to let players build. I’m still tweaking, reflecting on repatriation and resettlement, pondering narratives, shuffling my cards, but at the very least I am starting to scratch at the surface of my inner Churchill.

It was Churchill, after all, who said in 1901 that “war is a game with a good deal of chance in it, and, from the little I have seen of it, I should say that nothing in war ever goes right except occasionally by accident.” I suppose the same could be said of love too.

///

Header image: Sir Winston Churchill from the United States Library of Congress

The post The ghost of Churchill; or, how to make a wargame appeared first on Kill Screen.

The greatest technical feats in No Man’s Sky

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

A veteran explorer, low on supplies, lands on an uncharted alien planet with a cyan ocean and ruby-red grass. Enormous, dinosaur-like creatures with horns graze nearby, but at least there doesn’t appear to be any acid rain, unlike the last place. After some scavenging, the explorer hops back onto her spaceship to tackle another one of the 18 quintillion planets ahead.

The space exploration game No Man’s Sky, released in August 2016, is already famous for its singularly beautiful digital world. But it’s also an unprecedented technical marvel, one that marries artistic ambition and creative programming. These five crazy technical achievements show why No Man’s Sky is in a gaming category all its own.

No Man’s Sky marries artistic ambition and creative programming

A Single Equation Birthed the Game’s Entire Universe

Typically, game designers use a technique known as procedural generation to create new, randomized environments every time the game is played, similar to how worlds are built in Minecraft. Titouan Millet, creator of abstract exploration game Mu Cartographer, described the appeal of this technique as “the magic feeling of creating art from lines of code and mathematics.” But No Man’s Sky used procedural generation differently. Instead of handcrafting each world, the small development team at Hello Games taught a computer how to create a seemingly infinite variety of different planets.

Simply put, rather than creating an experience that’s changing endlessly, No Man’s Sky used the technique to create a single experience that feels endless. To achieve this, the game’s equation combined a single “seed” value that’s 64 digits in length with 1,400 lines of code outlining the many planetary categories. “The cool thing is that every planet has a single number, a random seed, that defines everything about that planet. A single random seed generates every blade of grass, tree, flower, creature,” explained creator Sean Murray on the game’s blog.

The algorithm builds trillions of different planets by picking and choosing from a variety of characteristics (like fauna, animals, colors, topographies) as if it were assembling a dish at a salad bar: The ingredients need to be complementary, not random, regardless of the combination.

It Would Take 585 Billion Years to Explore Everything

Theoretically, it would take any object traveling at the speed of light 100,000 years to traverse the entire Milky Way galaxy. Meanwhile, Sean Murray calculated that, if a player discovered a planet every second while playing No Man’s Sky, it would still take 585 billion years to see it all. Finding where No Man’s Sky ends would require players to be immortal.

It Has Real Solar Systems

To replicate real-world laws of nature, Murray said most games cheat. “The physics of every other game — it’s faked. When you’re on a planet, you’re surrounded by a skybox — a cube that someone has painted stars or clouds onto,” Murray explained to The Atlantic. “If there is a day-to-night cycle, it happens because they are slowly transitioning between a series of different boxes.”

Instead, No Man’s Sky’s suns, moons, stars and planets obey strict laws of astrophysics just like earth. When a planet changes from night to day, it’s not because of a two-dimensional skybox. It’s because of the planet’s trajectory around the sun. The designers did such a good job replicating the enormity of space that they even had to invent a probe to help them keep track of everything efficiently. But how close does it come to replicating the actual universe?

No Man’s Sky’s suns, moons, stars and planets obey strict laws of astrophysics just like earth

“There are two things I think are important to get right when you’re recreating a planetary system for a game: scale and diversity,” said astrophysicist Lucianne Walkowicz. Hello Games’ endless universe is certainly huge and diverse, but the programmers did cut a few corners for aesthetic and gameplay reasons. For example, their moons orbit closer to their planets than Newtonian physics allows.

A Trillion Planets Without a Single Load Screen

To achieve a feeling of seamless, never-ending exploration, No Man’s Sky renders enough of the universe around the player to ensure an uninterrupted vista while flying around in the ship. Touching down and leaving planets is just as seamless, with a short animation shooting the player right back into the clouds. Even inventory management happens in real-time, so players rarely get taken out of the moment-to-moment action.

Math Created the Soundtrack

British rock band 65daysofstatic faced a unique challenge when scoring No Man’s Sky: How do you write music for a near-infinite experience? “What would normally become a kind of refining process, sculpting a single song out of a bunch of different noises, instead became a kind of cataloging process,” said guitarist Paul Wolinski.

Similar to how the game populates its planets by pulling objects and animals from a given category, all the potential variations of a bassline, drum beat and guitar lead were placed into what Wolinski called “pools of audio.” From there, an intelligent bundle of code arranges the music based on what’s happening in the game at that moment.

Wolinski called this approach “generative music.” Borrowing from the concept of procedural generation, it uses computer logic to tailor the music to the circumstances onscreen in a smooth, unnoticeable way. It’s like having a conductor in the cockpit with the player, matching the orchestra to every move they make.

If developers continue to evolve No Man’s Sky, it could become a true technology wonder and source for endless joy. Players who better understand the algorithms that make it tick could be in for exponential amounts of fun for years to come.

The post The greatest technical feats in No Man’s Sky appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 31, 2016

Netflix’s new horror movie is what you should be watching for Halloween

There are a lot of horror movies on Netflix. 99% of them are awful*. So it makes sense, in terms of Netflix’s long-term plans to provide half of its own content, that they would want to remedy this situation themselves. Better curation? Okay, yes, but in lieu of that we have I Am The Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, a new movie starring Ruth Wilson (Luther, The Affair) from director Oz Perkins. It’s curation-via-creation; creating the content you wish to see in the world. And to be honest, the faith placed in Perkins as an auteur is heartening for what it says about Netflix in general. Or it’s a total anomaly. Let’s hope it’s not that.

Perkins’s first film, The Blackcoat’s Daughter (originally titled February), was a sedate, soft-focus horror movie in a thoroughly modern tradition: see also everything from Darling to It Follows to When Animals Dream; the list goes on. Placid cinematography; vaguely retro styling; quiet takes on genre tropes.

this is a rigorously minimal movie

The Blackcoat’s Daughter features a twist so low-key that I completely missed it the first time around; Perkins may well be angling for someone to call him a “master of minimalism;” I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House is his job application. This is a rigorously minimal movie; it is studiously staid, all careful soundscapes, morbid voiceover, and engrossing spectral whispers. There are maybe two jump scares, one of which is the film’s effective climax.

And contrary to nearly the entire slate of Netflix originals, I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House is not a readymade crowdpleaser. It’s not a franchise entry like Luke Cage or Jessica Jones; it’s not a nostalgia ploy like Stranger Things; it’s not a total mess like The Fall. It’s not something that you can just hit “play” on and easily soak in. It’s weird; it’s spiny; it’s creepy; it’s fucking slow.

Perkins’s style, down to the way he’s directing Wilson—effectively the movie’s only actress—is mannered and manicured, resulting in a sort of suffocating chill. Call it Eurohorror via Wes Anderson; all the slow-burn pleasures of Jean Rollin rendered with sharp aesthetic rigor.

What I’m telling you is that I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House is a rare beauty: a beguiling wisp of a ghost story somehow funded by the biggest streaming platform on the planet, told in smears of bleak poetic voiceover and curlicues of narrative sense. I can’t guarantee you’ll like it, but hell—you’ve got Netflix, right?

*The exception being Hellraiser. I’m on Twitter if you disagree.

The post Netflix’s new horror movie is what you should be watching for Halloween appeared first on Kill Screen.

Making a survival horror game without all the clichés

Narayana Walters, a computer science student at Appalachian State University, is fed up with seeing the same old designs in horror and survival games. But rather than sticking to moaning about it, Walters is doing the admirable thing of making his own: a non-linear, open-world survival horror game called and thus.

While it may be a little much to call and thus a reinvention of the survival horror template it does strike you at first glance. From what he has outlined on the game’s TIGSource thread so far, there are no zombies, no guns, none of the usual sights that might immediately turn you off the game if you, like Walters, can’t stand any more clichés.

Instead, Walters leads the way with a swaying GIF set in a wintry forest, crows stilling motionless on the branches, a carcass stripped to the bone and half-buried in the snow below them. It’s a menacing little snapshot of the game with smacks of Simogo’s first-person horror adventure Year Walk (2013) about it (you should play that if you haven’t already, by the way).

“something bad is about to happen”

In fact, the comparison to Year Walk could go a little further, as and thus will also be played from the first-person perspective. Walker also writes in the TIGSource thread that the game will focus on “mystery and the supernatural to invoke ‘scariness’ rather than gory, obvious monsters.”

Year Walk did something similar as it took directly from Swedish folklore, inhabiting its own forest with peculiar and frightening creatures, most memorably, the Brook Horse, Mylings, and the Night Raven. In fact, and thus seems to almost have its own version of a mystical raven, as seen in the GIF below. “When the harbinger appears something bad is about to happen,” writes Walker alongside it.

The only other aspect of and thus that Walker has shared so far is the dungeons. You will apparently come across a few dungeons as you explore the forest, and while they can be avoided, at some point you will have to head inside one. The one that Walker outlines is pitch black, and so you have to navigate it using tiny lights, trying to piece together a code that you enter into a terminal to escape.

Sound plays a huge part in this dungeon. The fragments of code you’re after have a distinct noise that you’ll be able to follow in order to find them, and so does the terminal. However, you’re not alone in that dungeon, and so you’ll also be able to hear the sound of the creature stalking you. If you hear it get close to you, you’re able to outrun it by sprinting, but this introduces more problems as your character will breathe heavy and that muffles the other sounds.

The design of this dungeon follows the two simple survival rules that Walker is applying to his game: “If it looks dangerous, it is. If it’s dangerous, run away/hide.”

Look out for updates on and thus over on its TIGSource thread. You can find out more about Walker on his website.

The post Making a survival horror game without all the clichés appeared first on Kill Screen.

All hail the ultimate videogame devil

“Dull” reads the game’s judgement, punched across the top-right corner of the screen in a disappointed font. Dante throws his shoulder, thrusting his blade into the marionette a second time.

“Cool!”

Later, once Dante has become a proper daddy’s boy, he’ll impress the game he’s trapped inside to the highest tier of its letter-based rating system. Devil May Cry (2001) is a game in pursuit of being “Stylish!”

As a theater of aesthetics, Devil May Cry cares little for anything else. The stage is an ancient castle dressed up to the nines: Gothic arches, cobwebbed corners, eerie portraits, phantom doorways. The actors are a half-devil man with silver hair and a big red overcoat, a woman in a corset and high heels, and a grotesque demon king that dresses himself up as a marble statue of a god. Dialogue includes such treats as “Woah, slow down, babe,” in response to a woman unexpectedly riding a motorbike through the doors of a shop, and, when that same woman is seemingly killed, the painfully cheesy yelp of “I should have been the one to fill your dark soul with light!”—delivered with a dramatic tossing back of the head on that last word.

Oh, and the leather. There’s enough black leather here to turn the castle’s grand entrance hall into a dry-wipe sex dungeon.

he’s an exquisite atlas of devil concepts

The stories behind Devil May Cry support the idea that it was made as a careful patchwork of Christian iconography and late medieval architecture. Director Hideki Kamiya sent a crew out to Europe for 11 days to photograph Gothic statues, stonework, and pavements to use as textures. But, as with everything else in the game, it got spun through Kamiya’s perverted pastiche; rather than a faithful imitation it became a histrionic entertainment. It’s telling that Devil May Cry’s theme of “coolness”—read: stylish exaggeration—was deemed too much for it to be an entry in the camp-as-hell Resident Evil series, as was originally planned.

One of the most enjoyable parts of Devil May Cry’s all-consuming aestheticism is seeing what hideous, grouchy-mouthed beast will come prowling out of the underworld to battle Dante next. By the time you’ve seen an oversized griffin with a beak like an exploded anus and a decomposed, five-limbed “living toxin” that throws giant eyeballs at you, you might think you’ve seen it all.

But no. It’s in its latter stages, when Dante pushes through the pulsing tissue of the underworld, that Devil May Cry reaches the peak of its aesthetic efforts. This is embodied by the game’s antagonist and final boss, Mundus, who, through his behavior, appearance, and name, serves as a blender for various underworld mythologies. He’s not just the devil, he’s an exquisite atlas of devil concepts as seen throughout history.

First, the name: Mundus. It’s derived from a ditch in Roman theology that contained an entrance to the underworld, the mundus Cereris. The stone that covered this supernatural pit was removed three times a year so that the dead could feast on the harvest in commune with the living—not quite the demonic takeover of the world depicted in Devil May Cry. As if to confirm this origin, Mundus is also identified as Pluto twice in the game, after the Roman god of the underworld.

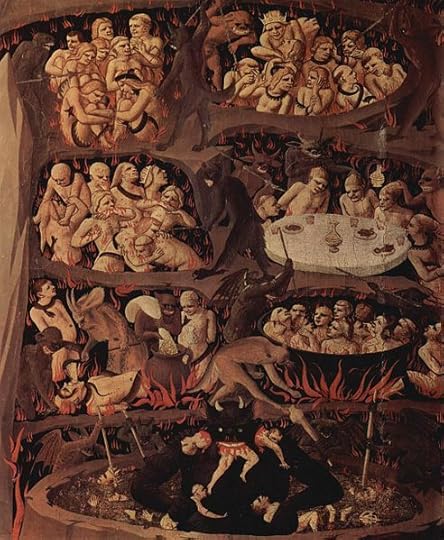

Next up on this Hell Edition of videogame bingo is Mundus’s appearance. For that we turn to the Christian Bible and the downfall of Lucifer. There are two important aspects of Mundus’s design to consider: 1) his angelic statue form contains three eyes, and 2) his true form is a festering mess of eyeballs and hands, a bulbous pile of rancid demon goo. This aligns him with Lucifer, the fallen angel, who it is said left God’s hand in a perfect state. It’s this that led to Lucifer’s big problem. He was so impressed with his own beauty, intelligence, and power that he fancied the honor and glory reserved for God for himself. He became corrupted by pride and, having been granted free will, decided to rebel against his creator—this was the origin of sin, predating the incident in the Garden of Eden. For this, God banished Lucifer from heaven and destined him to spend a millennium in a pit, after which he would be thrown into the lake of fire. It was also at this point that Lucifer’s name was changed to Satan, or “adversary.” Popular art from across history also depicts his banished form in a changed state (the Bible implies this, but is vague on the details).

“Hell” detail with Satan depicted at the bottom, from The Last Judgement, by Fra Angelico, 1425-1430, via Wikimedia Commons

No longer an angel, Satan has been drawn as everything from a foul goat-like figure to the tragic human hero of Paradise Lost (1667). One of the most outstanding renditions of Satan, however, is described in Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy (1320). He’s said to have his legs encased in ice, to be as ugly as he was once beautiful, and to have three faces—a perversion of the Holy Trinity—each perpetually chewing on one of the ultimate sinners. All of this is reflected in Mundus, whose three eyes could be a reference to Satan’s three faces, but especially the infliction of ugliness on a once beautiful being, as seen once Mundus breaks out of his statue form that depicts his younger self. Mundus even experiences the same descent as Lucifer, as his statue is first seen sat at the top of Devil May Cry’s castle, but after suffering defeat in battle to Dante—losing his angelic wings in the process—Mundus appears as a writhing mass of living tissue in the castle’s sewers.

The frequent appearance of mirrors and mirror images throughout the game are Mundus’s way of attacking Dante with appeals to his vanity. Mirrors appear in a number of forms in the game—including as a whole Mirror World—and each time trigger a conflict. The most potent of these is an actual mirror, from which Dante’s long lost and corrupted twin brother Vergil steps out from to combat him. While Vergil takes the form of the “Black Angel” Nelo Angelo, the battle is first implied through Dante’s living mirror image as a fight against himself—the narcissist metaphor made real. It’s what Mundus and Lucifer saw in the mirror that led to their downfall; the reflection of the self is what led to the creation of the devil. It’s no coincidence that satanic imagery is often a ‘mirror image’ of Christian idolatry; the inverted cross, inverted pentacle (representing earth), Hell versus Heaven, and a devotion to the moon in opposition to the sun worship of primitive religions. To the devil, perhaps the most evil and powerful weapon is self-destruction, and through mirrors, Mundus finds a way to wield it against Dante.

an eternity wandering the endless sea of the underworld

Both of the remaining underworld myths wrapped up in Mundus play out through his behavior, specifically the weapons he uses to combat Dante before the final fight (besides mirrors). The first is Nightmare, which is described in the game as a “bio-weapon created by the Dark Emperor,” aka Mundus. Dante battles it three times in total, it first appearing in the cathedral as a “strong surge of evil coming from [a] puddle of water.” After Dante stares into that puddle, Nightmare bubbles out of it in its invulnerable “gel-form.” The game is very sterile in its descriptions of Nightmare, which is among the grossest living shit in the game, it being a liquid that contains the corpses of those it’s killed, all steaming piles of bones and sickly black glop. It recalls the River Styx of Greek mythology—the river that forms the boundary between the underworld and Earth, and which is often depicted with the dead reaching out of it. Just to stack up the disturbing imagery, once Nightmare’s restraining tools are activated (moving it into its vulnerable state), it encases itself in hard armor like the alien, biomechanical creatures H. R. Giger drew in his Necronomicon (1977).

While being gross and temporarily invulnerable should be deadly enough, Nightmare’s greatest attack is being able to absorb its foes into some unknown inner plane where their trauma is turned into physical enemies. It’s a form of attack that, similar to how Dante is assaulted by himself in the castle’s mirrors, is metaphorically psychological, but in the action of the game means you have to face the bosses you previously slain. Which, to put it lightly, is a royal pain in the ass, essentially meaning any encounter with Nightmare has the potential to have several sub-bosses to defeat at its middle. It’s also within this inner Nightmare realm that you encounter the Sargasso, a lower class of demon named after the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic Ocean, referred to as the “sea without shores.” The significance of these floating, chattering skulls is that they confirm Nightmare’s connection with Styx, as the in-game descriptions inform us that they feast on lost wanderers, condemning the spirits of their victims to an eternity wandering the endless sea of the underworld.

The last of Mundus’s psychosomatic tactics against Dante is the most successful. This comes in his mimicry of the temptations of the Demon King Mara from ancient Buddhist scripture. The demon Mara (meaning “destruction”) is said to have schemed against Siddhartha Gautama while he reached enlightenment to become the Buddha. Mara’s first method was to arrange his most beautiful daughters and have them try to seduce Gautama while in meditation. While Mundus in Devil May Cry doesn’t have any daughters, he does create a puppet woman named Trish under his control, and gives her the face of Dante’s deceased mother. Trish is the person who arrives at Dante’s demon-fighting agency and asks him to come to Mallet Island to stop Mundus from invading Earth. It’s a guise, of course, but Dante falls for it as he sees his deceased mother in Trish’s face.

Mundus’s reason for luring Dante to the island and its castle is so that he can throw his demon generals at the one person who might stop him from taking over the human world. Mara is said to have used a similar tactic against Gautama, forming vast armies of monsters to battle him, yet Gautama sat untouched, as does Dante by the game’s end. Marta and Mundus also sling the same insult at their respective targets as a final attempt to thwart them. Marta tells Gautama that a mortal cannot claim the seat of enlightenment and so it rightfully belongs to him, a supposedly superior being. In Devil May Cry, this is translated to Mundus mocking Dante’s human heritage, saying that it has “spoiled” the devil blood he inherited as the son of the legendary dark knight Sparda, who previously defeated Mundus and sealed him in the underworld.

truly one of the most excessive devil beasts contrived

In response to this insult, Gautama had the earth itself talk in his defense. Of course, Devil May Cry can’t be so humble, instead having Dante’s eyes glow red with devil energy to deflect the lasers Mundus zaps at him, before they both tear off into a pocket dimension for a showdown that dwarfs any conflict in the Bible. Gautama’s victory led to Buddhism, while Dante was succeeded by Bayonetta (2010)—Kamiya and his team’s derivative creation that traded “coolness” for “sexiness.” It starred an amnesiac witch who walks on gun stilettos in a skin-tight suit made of her hair, which she also uses to summon demons (rendering her naked) to fight against the angels of the game’s extravagant version of Paradiso. All the campy melodrama of Devil May Cry is spun tenfold in Bayonetta, but it doesn’t quite have a single figure so rich with historical pastiche as Mundus. He’s truly one of the most excessive devil beasts contrived in a work of fiction. The devil four-in-one, for all your demonic needs.

It seems right that Bayonetta, probably Kamiya’s most theatrical character of all, should have the final word on his wild, eclectic approach to remixing those holiest and unholiest of the metaphysical realms. “Heaven and Hell can tear each other to pieces for all I care. I’ve got my own problems to worry about.”

The post All hail the ultimate videogame devil appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers