Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 30

November 9, 2016

Accurate Coastlines evokes the difficult task of map making

Clément Duquesne has made a bunch of impressive games and digital toys using procedural generation, but one of his latest is particularly striking. Called Accurate Coastlines, it lets you scroll your mousewheel to zoom infinitely inwards on the shores of an unspecified island.

You can target your cursor at any part of the island to zoom in on it, but doing so anywhere but the coastlines prove fruitless—the game works by contrasting the yellow of the land against the blue of the surrounding sea. This draws you to an endless pursuit of minutia; to see how tiny and detailed the island’s contours can be. With this, Accurate Coastlines feels like a riff on similar web toys like Scale of the Universe and Zoom Quilt. It’s something you play with to help a couple of idle minutes pass by quicker. But it also, implicitly, invites deeper thinking.

evokes the inevitable inaccuracy of map making

We’re at a point in time where we’re used to seeing scale maps of countries used to visually demonstrate news stories. Most recently, the US presidential election coverage used a map of America to show how the majority of each state voted. It’s a map used to ultimately demonstrate divide, with the red and blues representing the two major opposing parties steadily being filled in as the votes came in.

I’m also reminded while playing with Accurate Coastlines that right-leaning politicians this year in both the US and the UK have put an emphasis on borders and building walls to keep out immigrants. They spoke in broad terms about erecting physical dividers between countries, which begs the question of where exactly they would build these walls—along what lines would they lay the bricks? Accurate Coastlines almost feels like it’s poking fun at that idea, as if it acts as demonstration of how granular you can get with demarcations. Which grains of dirt belong in America and which in Mexico, Mr. Trump?

Accurate Coastlines is a pleasing web toy that you can play without thought. But it’s also one that seems evokes the inevitable inaccuracy of map making, and the important distinctions and omissions we make when drawing up borders.

You can play Accurate Coastlines in your browser over on itch.io.

The post Accurate Coastlines evokes the difficult task of map making appeared first on Kill Screen.

Surprise yourself by learning an alien language in Sethian

Sethian is a game that positions you as an archaeologist of the future tasked with learning an alien language. You do this so you can investigate the disappearances of people on the planet Sethian—where the language originates. Learning a whole other language might sound pretty imposing, but the creator of Sethian, Grant Kuning, has done a pretty bang-up job of making the game fairly accessible.

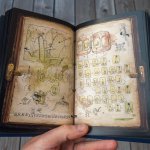

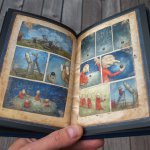

You sit in front of an alien computer, able to ask it questions to help with your study, starting with only the basics of the language as picked up by previous archaeologists. This is provided to you through the hand-written notes and the dictionary inside of a journal. The journal comprises over 100 pages in total, but these are unlocked steadily rather than overwhelming you en masse so that you steadily pick up on what each of the linguistic symbols mean.

It’s enough for you to enter the first few basic questions—”What are you?” and “Where is this place?”—but after that you’ll have to start experimenting with combinations of symbols to form sentences by yourself. When it gets to that point you should find yourself surprisingly up to the challenge. You’ll be able to investigate several topics of interest at a time, slowly piecing together the Sethian culture, as well as the language as you interrogate its speakers.

a complex system of symbols to represent the meanings of words

Kuning decided to make Sethian after studying Chinese for three years (and teaching English over in China). The similarities between the fictitious language in Sethian and Chinese are that they both use a complex system of symbols to represent the meanings of words. This differs to, say, the English language, which uses an alphabet to write down pronunciation rather than meaning in its written form. Kuning’s language also borrows from other forms such as American sign language.

Kuning explains that the Sethian language in the game “uses a series of 100 unique symbols to represent each of the language’s 100 roots.” Each one of these roots represents a word by itself but they can also be combined to form new words. This is true in other languages, too, as Kuning demonstrates: “you know what a foot is, you know what a ball is, and together they make a new word, football, Here’s another: ‘no’ + ‘where’ = ‘nowhere’. Now here’s an example in Chinese: 酒 means alcohol, and 杯 means cup, but a 酒杯 is a wine glass. This kind of thing is actually even more common in Chinese than it is in English.”

As to the symbols themselves, Kuning took directly from ancient geometry, inspired by the messages drawn up by Carl Sagan for the Pioneer spacecrafts. Sagan’s goal was to provide a message that could be understood by intelligent alien life by using mathematical and scientific information. And so the Sethian language follows the same approach, comprised of basic shapes, lines, and dots.

If you are turned off by learning an another language as it seems hard then you should give Sethian a go. It might prove easier than you think, not just because it comes with a tutorial, but also due to its limited scope. As Kuning explains, Sethian hasn’t developed any of the strange quirks and irregularities of real languages, evolved through generations of speakers. Nor do you need to worry about being able to sound it out vocally as the game is text only. “By making something up, I can create a language that plays by all its own rules, and keep those rules short and sweet,” Kuning said.

You can purchase Sethian on Steam and itch.io. Find out more about it on its website.

The post Surprise yourself by learning an alien language in Sethian appeared first on Kill Screen.

Escape into a new game’s dreamy cassette tape worlds with these GIFs

If you’re being overwhelmed by all the presidential election noise today you might be looking for a temporary escape to another world. Small Radios Big Televisions should prove an adequate host.

Out for Windows and PlayStation 4 as of yesterday, Small Radios Big Televisions doesn’t have just one world for you to explore, but several. Inside its depopulated factories you’ll come across cassette tapes that act as plastic gateways into these dreamy realms—each labelled with a single descriptive word like “ROAD” and “COAST.” Upon finding them, you watch as they’re slotted into the tape player, the reel unwinding to the glitchy chorus of data bending: scanlines wobbles across the screen, electric fuzz dances along textures, then you’re warped to another place.

scenes and sounds looping meditatively

You can hang out at the singular scenes contained in each tape for as long as you like, taking in the woozy music, daydreaming into oblivion. The game is conducive to being used in this way, its scenes and sounds looping meditatively, it allowing you to play with just one hand on the mouse, pulling at the tops of springy trees for no real purpose. But eventually you’ll have to snap out of it and do what you went there for, and that is to find the gems hidden inside each world—and sometimes that requires you to corrupt the tape. With those, you can unlock doors to new passageways into the factories, to new tapes, new worlds.

You can read more about how the game plays out here. But if you need instant chill right now then perhaps the GIFs below will help you out.

You can purchase Small Radios Big Televisions on Steam and PlayStation 4. Find out more on its website.

The post Escape into a new game’s dreamy cassette tape worlds with these GIFs appeared first on Kill Screen.

Solve a murder mystery designed by middle school girls

You know that uncomfortable feeling of being outdone by someone much younger than you? If you’re not familiar, prepare to get acquainted with it: meet Interfectorem, a visual novel made by a team of four girls aged 11-15 years old.

Interfectorem tells the story of 16-year-old Alis, whose seven-year-old sister, Sali, is brutally murdered after the mysterious disappearance of their parents the year before. Sheriff-in-training Alis swears to track down her sister’s killer and wreak well-deserved vengeance. Helping the girls out on the project was director and programmer Andrew Dang, artist Reimena Yee, and musician Jon Peros.

A smart blend of horror and humor

Interfectorem’s impressive young designers were participants in a Girls Make Games camp in San Francisco, CA. As I recently discussed, the world of videogames can be a difficult place for women and girls. Girls Make Games is determined to address that gender disparity. With help from their growing list of partners (including Google Play, Double Fine, and the Computer History Museum in Mountain View), Girls Make Games runs global summer camps, workshops, and game jams designed to inspire young women in middle and high school to become engineers, designers, and creators.

Their flagship program, a three-week game development summer camp run in 15 US cities, culminates in a ‘Demo Day’ competition in the Bay Area between the top five development teams. The winning team receives a yearlong mentorship and the chance to have their game professionally produced and published through Girls Make Game’s parent educational company, LearnDistrict.

In July 2015, the four girls brought Interfectorem to the second annual Demo Day at the Computer History Museum, where it won the Grand Prize. A smart blend of horror and humor (“think Nancy Drew meets Shaun of the Dead”), Interfectorem went on to raise over $12,000 on Kickstarter.

Will you be able to solve Sali’s murder? Play Interfectorem here to find out.

The post Solve a murder mystery designed by middle school girls appeared first on Kill Screen.

I miss the summers in Japan: How videogames overcome language barriers

I sat cross legged in front of the TV and watched as Alex carefully removed the Super Nintendo from its dusty, neglected box. Our grandfather hardly used it, preferring to play Shogi on his computer instead of the console. Also stored away were a pile of games with labels we couldn’t read. The Japanese characters were printed in bold intimidating letters, with no illustrations to help guide our interpretation of what the cartridge held. He fished around for a second before grabbing the Super Mario World (1990) cartridge, blowing into it. It was a very familiar ritual, repeated during our yearly trips to see family in Japan.

My brothers and I had been playing games in Japan since we were eight. We played Super Mario World every single time we visited. As he switched the console on, the menu appeared and he came to join me on the floor. His hands seemed too large for the small controller, looking lanky and awkward. The unfamiliar kanji of Super Mario World took over the screen, a glaring reminder that neither of us could read the letters of our own heritage. Unphased, he pressed start.

///

Although there is no physical structure barring you from interacting with someone who doesn’t speak your language, trying to communicate with a language barrier is difficult. Before the conception of Google Translate to provide on-the-fly if questionable translations, one would have to pantomime or play an awkward game of charades in order to communicate an idea effectively. Trying to overcome a language barrier is getting a little easier with the accessibility of the internet. There are YouTube videos, mobile language apps, and services that pair you with a native speaker who can help you practice your skills. It’s become less intimidating to climb that figurative wall.

there will always be things lost in translation

That being said, there are still a number of problems with these tools. Google Translate is only satisfactory at providing common phrases that are absolutely essential to surviving in a foreign country. For example, you’ll be able to find English speakers in Tokyo because it’s a big city with a lot of tourists. You can get by without knowing how to say “where’s the bathroom?” in Japanese. If you travel to more rural areas, it’s likely that you won’t have the same experience. Knowing how to say “といれ わ どこ です か?” is pretty important. I didn’t go into Google Translate for that. I knew what I wanted to ask and typed it out in Japanese. But if I didn’t have this knowledge, and wanted to ask “where’s the bathroom?” and pasted it into Google Translate, this is what I am presented with: “バスルームにはどこですか?”. You’ll note that this is not the same as what I had typed. Google takes a long-winded way to ask where the bathroom is—a simple phrase that doesn’t require all of those extra characters. As an added bonus, Google also incorrectly translates “bathroom” as “Basurūmu”. It should be “toire”. Because in Japanese, you don’t really say “bathroom”, you say “toilet”. Is that confusing? Yes.

This demonstrates how there are not always direct translations from English to another language. Translators run into this problem all the time—an idea that may take an English speaker two sentences to convey might take a Japanese speaker closer to 10 sentences, perhaps due to sentence length or the speed at which they’re talking. This is why, when you watch an interview with a Japanese game creator accompanied by their English translator, you might wonder if something seems “off”. It’s because of that obstacle of structure. It’s hard to take something and translate it on the spot, trying to pick and choose the right words to communicate, as well as provide alternatives to words that have no direct translation. Even with the best translator, there will always be things lost in translation. Language is tricky like that.

///

We all put on our shoes one by one by the genkan (玄関) while Oba-chan stood behind us with watchful eyes. “Be respectful when you go over to Sunaga-san’s house,” she told us. We nodded before piling out of the door and running across the street toward our neighbor Yuka’s house. She was older, but had known us since we were small. Her family was fond of us and also possessed a Super Nintendo. They had more games, and always told us we were welcome to use it.

When my brothers and I would spend the entire summer in Japan, we would take that offer seriously. I reached up to the buzzer and pressed it, listening to the soft humming noise that escaped the speaker. “Yes?” A familiar voice chimed in response, and Sunaga-san opened the window by the front door. “Come inside!” We took off our shoes by the genkan and ran straight over to the living room, where Yuka had set up the Super Nintendo for us. She was at school. Sunaga-san ushered me over to the kitchen while Jacob and Alex scrambled for the controllers. “You can have all of these treats,” she said, motioning toward a pile of chocolate and crackers. I understood her clearly.

My Japanese was very good as a child. It was rude to deny offerings of food, and so I accepted the gesture before joining my brothers in front of the TV. They were playing Puyo Puyo Tsu (1994). We stuffed rice crackers into our mouths while passing the controller after each loss, taking turns watching cutscenes and wondering what the characters were saying. The small text ran across the screen, its meaning lost upon us as we huddled together and jabbed our tiny fingers at each combo we could score.

///

There are activities that go beyond language barriers, requiring no common tongue in order to be understood by both parties. Everyone around the globe shares the same action to show that they’re choking (what you might call the “universal choking” sign)—by placing their hands up to their neck and looking distressed. That transfer of information is instant and innate. I don’t need to know Japanese in order to run up and provide the Heimlich maneuver. Arguably more terrifying than choking is the language of dance (especially if you have two left feet like me). Dance: where the movement of your hips and the positioning of your feet say more than words ever could. Dancing can be calculated and beautiful or impromptu and clumsy. But everyone can understand each other during this activity without having to open their mouth once.

Games have been used to facilitate conversation

Just as there is the language of movement, there is also the language of play. The act of playing a game with someone you can’t communicate with verbally creates a conversation that takes on a different form. There’s an implied understanding of what is going on. There will be a winner and a loser. The process from A to B can be completed without uttering a single word. A game that has embodied this well would be chess. Chess has been around for 1500 years, originating in India and spreading to Southern Europe. It’s when chess arrived in Europe that the modern developments we see in the game happened. The pieces were changed, tournaments became a thing, and people began establishing chess theory. After being picked up by Buddhist pilgrims and traders on the Silk Road, it spread to the countries of East Asia. Of course, there are variants of chess such as Xiangqi and Shogi (from China and Japan, respectively). Without even sharing the same language, people have picked up the game and made it their own or carried it back to their country to share.

The act of playing traditional chess has provided what videogames are accomplishing today. It’s bridging the language barrier gap in its own small way by providing an experience that is hard to replicate. When Oba-chan and Oji-chan came to visit my family in America many years ago, we still owned a GameCube. Although they had no idea what I was playing, they would watch me as I picked crops in Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life (2003). They would laugh when I would walk up and brush my cow and angered it, causing it to moo furiously at me. They never asked questions, but simply watched and enjoyed. We were sharing a moment.

Games have been used to facilitate conversation and interactions between two people who don’t share a common tongue, or who may have a rudimentary grasp of the language and can’t understand a conversation to its fullest. Growing up playing games in rural Japan with my brothers has taught me this. It helped shape my understanding of how people create connections with each other, even if they may not fully comprehend what one another is saying.

Games were so important to the relationships that I crafted as a child during the hot summer days. I may not have always understood what the neighborhood kids were saying, but I didn’t need to know everything in order to have a Jirachi transferred over to my Game Boy Advance through a game link cable. I may not have understood what my cousin said to me and my brothers, but we didn’t need to know in order to unleash an onslaught of Beyblades toward an unsuspecting group of ants. My brothers and I would play Yu-Gi-Oh with the boy who lived behind our grandparents, even though all of our Japanese was rusty.

As I’ve grown into an adult who has continued to play games, I’ve come to realize that I would not have such a deep-rooted love for my second language if not for the summer of 2002. That was when, for me, games and language really intersected, when everyday was filled with nothing but speaking Japanese 24/7 and playing Yu-Gi-Oh or Clock Tower across the street. That summer couldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for my mom taking the time and effort to teach the three of us her language. Since then, my mom has stopped talking to me in Japanese, because as I grew up I would automatically respond to her in English. She just stopped. And I’m trying to get it back. I feel like I lost a connection not only to my mom but also to one of my most treasured memories. And so I look at videogames as both having achieved in helping me to appreciate Japanese but also instilling in me the feeling of guilt for not keeping up my study of it. I hate that I can’t read difficult Kanji yet, even after a year of practicing. I’m frustrated that I couldn’t translate everything that Hideo Kojima said during the Tokyo Games Expo. Maybe guilt isn’t the right word, but it’s games that are making me want to try to get it back—what I’ve lost is a way to communicate with another country, another people, my own mother. Sharing a controller with someone is symbolic of that pursuit, as while it won’t necessarily teach you another language, the way it overcomes language barriers is a start.

///

I was proud of myself. Although Oba-chan worried incessantly and walked me to the bus station in our rural part of Chiba, I had managed to board a bus that would take me to the local mall that had an arcade center. It was a familiar location, but my mom was not here with me. I had actually been alone in Japan for a few days. If I needed her to help me with a translation, she wouldn’t be able to provide me with one. I was on my own. I sat on the bus, staring out at the rice fields next to me as they slowly became tall buildings. My Japanese was good, I told myself. I would manage.

After I reached my destination I went to the third floor of the mall, remembering the routine that had been repeated many times throughout the year. It felt strange coming here without my brothers. Jacob and Alex would usually haggle with me for more Yen so that they could continue to play games. We could rely on each other for translations—but they were not here. I walked into the arcade and was greeted by rows and rows of claw machines, dance pads, rhythm games, and gashapon stations. They were all brightly lit and music emanated from every corner. I had my eyes set on a claw machine stuffed with miniature Shiba keychains. As I walked up to the machine, I noticed something—I had no idea how to use this one. It was different. I’d never seen how to use this one before. It wasn’t as simple as inserting 100 yen and moving the claw. I stood in front of the machine for a few minutes, staring at the instructions in front of me that I could not read.

As if reading my mind, a girl came up to me and motioned toward the machine. I stepped aside, and she smiled. I watched as she played the game, taking in her technique. She tried the game a few times without winning anything before stepping away and offering me the last play. She said something to me in Japanese. Embarrassed, I responded: “あ!あの, ありがとう!すみません.” (“Oh! Um, thank you! Excuse me.”) I gave her the first Shiba that I ended up winning from that machine.

The post I miss the summers in Japan: How videogames overcome language barriers appeared first on Kill Screen.

November 8, 2016

What if game difficulty came from controllers rather than software?

In the case of digital games, the software acts as the variable, it changing to provide more difficulty as the player progresses. The controller and its input systems never change.

This may be an obvious bit of analysis but it’s the observation that forms the basis of a project by Swiss multimedia designer Mylène Dreyer. Called Incontroller, it inverts the typical set-up of digital games as outlined above—rather than the software changing, the physical controller changes to provide increased challenge.

the challenge of the game comes from its hardware

The idea in Incontroller is to control a ball along a meandering track made of sharp corners. You do this with four arrow keys that correspond to the movement direction of the ball—standard stuff. However, the track that the ball travels along doesn’t alter in any of the game’s levels, instead, the arrow keys start to dance around and make it harder be used.

As you’ll see in the video below, in level 1, the arrow keys are still and remain in place, but by the time you get to level 6 they’re moving further apart from each other and becoming taller. Hence, the challenge of the game comes from its hardware rather than the software, as is typical.

Dreyer made Incontroller back in February 2016 as part of her course in Media and Interaction Design at École cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL).

h/t Creative Applications Network

The post What if game difficulty came from controllers rather than software? appeared first on Kill Screen.

Prepare your cat butts for a live-action Neko Atsume movie

Neko Atsume (2014), the beloved cat game for smartphones, is being turned into a live-action movie. Meow indeed. That means it’ll feature real cats—proper little fluffballs that deserve all the strokes—so perhaps it stands a chance at being the best videogame-to-movie adaptation (not that it would take much).

AMG Entertainment are the people doing the world this favor, however, they only announced the movie for Japanese audiences for the time being. That said, the game was only available in Japan at first, before its popularity transcended language barriers and sent us all into a cat-feeding frenzy. The movie will be titled Neko Atsume no Ie (House of Neko Atsume) and has a proper story line and everything (that has been handily translated by Siliconera).

I’ve got to see what live-action Tubbs looks like

It follows an award-winning author called Katsu Sakumoto who moves to a quieter part of Japan to help overcome his severe writer’s block. One day, in his new lodgings, he sees a cat and attempts to make friends with it, but the cat rejects his invitation. “The thought that even cats would desert Katsu made things more depressing for the writer,” reads the description, according to Siliconera‘s translation.

However, one night, Sakumoto decides to leave some food out at the corner of the garden. Come morning, the food has gone, prompting Sakumoto to continue leaving food out in order to get friendly with the cat. Given that, in the game, you leave food and toys out to attract a range of different cats (including ones that wear costumes) to your house, you can probably have a good guess as to where the film goes from there.

But if you are able to get to a Japanese theater in 2017 then you won’t need to guess—you can watch the film for yourself. Hopefully global demand for the movie will mean it comes to other parts of the world. I hope so—I’ve got to see what live-action Tubbs looks like. Though, it should probably be noted, this isn’t the first time Neko Atsume has collided with real-life cats: last year there was an 11-hour livestream of “Real-Life Neko Atsume” for Google’s Games Week. Even if, somehow, the movie turns out bad, at least we still have that.

Neko Atsume no Ie is coming to Japanese theaters in 2017. Find out more on its website.

The post Prepare your cat butts for a live-action Neko Atsume movie appeared first on Kill Screen.

A new studio where people who don’t like videogames make videogames

Montreal-based programmer Brie Code has set up a new studio called Tru Luv Media that aims to make videogames with the help of people who don’t like videogames. The reason being that she wants her friends and people like them to care about games. These are people for who videogames do not resonate at all, mostly because they draw from the same cultural references time and again, use the same design principles, and are primarily made for people who already play videogames—there’s nothing there for anyone else.

Code herself has worked on games for a number of years at Ubisoft Montreal, including Company of Heroes (2006), some Assassin’s Creed titles, and most recently was the lead programmer on Child of Light (2014). Now she’s breaking away from this past. Writing on gameindustry.biz, Code explains that it was speaking to one of her friends who doesn’t like games that brought her to realize that her ideas had been bad. “I realized that I was stuck,” she writes. “This is what happens when everyone is the same as each other. We make boring things.” Code points to the dominance of white men in the videogame work force (who already like videogames the way they are) and how this lack of diversity leads to an echo chamber of ideas.

“It must help them understand their lives more”

Code explains that she set out on this path a few years ago when her friends acquired tablets and started asking about videogames. She saw it was an opportunity to introduce them to her favorite medium but it didn’t work out. One of her friends couldn’t finish Journey (2012) as there is a snake in it that could kill her character, and “she is deeply uninterested in being attacked in a game.” Code’s own game, Child of Light, also didn’t appeal to her friends as the play space wasn’t “deep” enough and the control scheme wasn’t accessible for someone who didn’t play games already.

However, that same friend who couldn’t play Journey did also play the epic fantasy-RPG Skyrim (2011), and while the dragons and combat didn’t appeal at all, that friend did fine that she cared for the non-player character Lydia. “When Kristina gets home from a long day, she doesn’t want to battle it out in a game or get frustrated in a game,” explains Code. “She wants to experiment with who she is in a social context of characters whom she cares about and who care about her.”

Once Lydia died in the game, Code’s friend stopped playing Skyrim, but it was a starting point: someone who didn’t like games found something they enjoyed in a game. Code sees in this a chance for videogames to appeal to more people if only they were listened to and videogames were shaped after what these people are after. “It’s not enough to remove the things that my friends don’t like and think they will like video games,” Code writes. “The experience must be based in things that they care about, in problems they have in life. It must help them understand their lives more.”

This is what Code is looking to achieve with Tru Luv Media—to make videogames for people who don’t like them, and to do it by having them help out in their creation.

You can read Code’s full article over on gamesindustry.biz. Look out for updates from Tru Luv Media on its website.

The post A new studio where people who don’t like videogames make videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

Videogame protagonists can have Asperger syndrome too

Chirag Chopra, the founder of New Delhi-based game studio Lucid Labs, got interested in finding out more about Asperger syndrome after watching a few movies about it, including Fly Away (2011) and A Brilliant Young Mind (2014). After doing research into the subject, Chopra decided that he wanted to make a game with a protagonist who has Asperger syndrome in order to, like those films, show that people with it lead lives like everyone else.

This is true in many cases: Asperger syndrome isn’t an illness or disease, it means that a person sees and experiences the world slightly differently to other people, which becomes a crucial part of their identity as it sticks with them for life. While Asperger syndrome does fall onto the autism spectrum, it only means that some individuals will need a little more support in some areas, whether that be in processing language or in specific learning scenarios.

people with Asperger’s aren’t any less capable

It also tends to be the case that a person with Asperger syndrome has either average or above average intelligence. Chopra wants to show this “smart side to the world and bust a few myths around the whole disorder.” In the game, a point-and-click adventure titled That Little Star, you’ll play as a 12-year-old boy who has been diagnosed with mild Asperger’s called Edward. The plot kicks off after Edward witnesses the death of someone close, which triggers him to investigate into the truth of the matter while dealing with his social anxieties. The effects of Asperger’s syndrome show up in the game during conversations when Edward tries to remain calm but the anxiety of the situation can lead him to do actions that oppose what he actually wanted to do.

Chopra told me that he chose to have Edward investigate a death (or potential “murder”) to show that he and other people with Asperger’s aren’t any less capable of dealing with such scenarios. “I think the more we try and form a barrier between normal human beings and Aspies, the worse it gets and doesn’t help them in any way,” Chopra said. “I strongly believe every Aspie has single or multiple things they are really good at and if they get good support, there’s no stopping them even with all the taboos and nonsense surrounding the whole Asperger’s syndrome.”

That Little Star will be the second game that Chopra and his team at Lucid Labs have weaved a story based in real-life scenarios into a videogame format. The team’s previous game, Stay, Mum, is a puzzle game for mobile about a young boy who deals with his mom’s absence as she works tirelessly to support the family. The player helps the boy play with building blocks, stacking them up to form different shapes that fuel his imagination.

That Little Star is coming to PC in mid-2017. You can look out for updates on the game on the Lucid Labs website.

The post Videogame protagonists can have Asperger syndrome too appeared first on Kill Screen.

November 7, 2016

Samorost 3’s physical version brings the game’s world closer to you

It’s only right that sci-fi point-and-clicker Samorost 3 gets a physical version. It’s a game that emphasizes tactility through its biological textures: from the gnarled knots of a planet made of tree bark to the soft sprigs of moss on one of its greener planets. The “Samorost 3 Cosmic Box” addresses this absence by giving you things you can hold in your hand alongside your purchase of the game.

Available now for $50, the Cosmic Box’s cloth-covered box has been partly hand-made (the rest handled by machines) in the Czech Republic. This is where the game’s creators at Amanita Design live, and also where they photographed insects, fungus, and plants found in local lush forests to use as the textures in the games. The aim of the Cosmic Box seems to be to bring the source of the game’s inspirations close to you.

sketches of creatures and objects that made it into the final game

To that end, it contains a cloth-covered book with two storybooks and a walkthrough inside. There’s also an art book included with black-and-white sketches of creatures and objects that made it into the final game. You can have a look at those books below.

The Samorost 3 soundtrack by Floex is also included in the Cosmic Box but only on a CD. If you want it on vinyl then you will have to make a separate $25 purchase. It includes two LP 180 gram audiophile vinyls, six art prints based on Samorost 3 by Adolf Lachman (which look real good), and a FLAC version of the album you can download.

If you want to hear a little bit of the soundtrack (and you really should) then you can head over to Floex’s online store for a quick preview.

If you haven’t played Samorost 3 yet then you should get on that. It’s a mostly wordless adventure about a space gnome who happens across a magical flute and sets out to find where it came from. It leads the gnome to several planets, each with their own woodland theme, where he helps out the locals and pulls off a bit of mischief to get by.

Oh, and if you do buy the Cosmic Box then you get Samorost 2 (2005) as a bonus so you can see how Amanita Design’s techniques and imagination have progressed in the decade between it and Samorost 3.

You can purchase the Samorost 3 Cosmic Box on the Amanita Design store. The vinyl version of the soundtrack is also available on the Amanita Design store. Find out more about Samorost 3 on its website.

The post Samorost 3’s physical version brings the game’s world closer to you appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers