Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 31

November 7, 2016

Save the colors of Quur’s painterly world from disappearing

The students that made Quur say it’s a game about the impact of violence. But it’s not full of blood sloshing around the dirty concrete of some decrepit virtual city. Quur has the look of a game so innocent that you’d think it doesn’t even know what violence is outside of a kid stealing its lunch money. It’s a pretty little thing but don’t discredit it for its looks.

Sure, Quur doesn’t have the dynamism of say, Dishonored (2012) and Undertale (2015)—which also offer the choice of violence and non-violence, and change their worlds in huge ways depending on the approach you take—but it has merits in its illustration. As you might guess with only a single glance at Quur, where it excels is in the visual department. It presents a world and ecosystem that literally thrives on a magical liquid called Color. Fair warning: you’ll probably want to go on a vacation to an impossibly happy place after playing it.

look like the result of a melted jellybean

In Quur, waterfalls are made of foam and bright orange, spilling into rivers that fork across the landscape as if the result of a disaster at a paint factory. No wonder the creatures and foliage are enticed to drink up the liquid—it looks like a substance made of rainbow drops and pure sugar. In turn, this liquid has had a vivid effect on the appearance of the world’s lush vegetation and timid creatures. Leaves, shoots, and skin look like the result of a melted jellybean.

Where Quur starts getting into its little spiel on violence is through the creature you play: some lithe, inky being that is able to manipulate Color. They can suck it up from the rivers and puddles and have it orbit their body, ready to use in any way they wish. But Quur offers only a few options with its button scheme: you can punch with Color, throw it as a projectile, or raise it like spikes from the ground to scare off nearby intruders.

With these at your disposal, it’s up to you whether to weaponize Color or not, turning it against the creatures that thrive on it. If you do, and you kill them outright, each animal and the surrounding area will be drained of its color so it becomes pure white. It’s saddening to see, especially as the game doesn’t prompt you to attack the animals in any way, meaning the arrival at that decision is all your own doing (prepare some inward thinking and reflection, you monster). The behavior of the animals also helps to weigh down on the guilt: the smaller creatures back off and growl like a nervous dog if you get close, while the bigger ones bark in warning and will attack first if you don’t back off. They want to be left alone.

Quur has a simple message at its heart, then: work with rather than against the world. It’s an eco-friendly videogame made in pretty colors. Perhaps some will find its metaphor a little too obvious, practically a cliché, and I wouldn’t disagree, but it’s still great to look at—almost like a painting turned into a game.

You can download Quur for free over on itch.io.

The post Save the colors of Quur’s painterly world from disappearing appeared first on Kill Screen.

The influence of Blame! on videogame architecture is rising

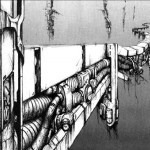

Blame! (1998) is getting everywhere these days. The dark, vast architectural spaces of Tsutomu Nihei’s manga series seem to be steadily rising in popularity, like sentient tower blocks growing stories at a time, casting a deeper and deeper shadow over popular culture. Next year it’ll likely hit the mainstream as an anime film adaptation is coming to Netflix. But perhaps Blame!‘s best utilization isn’t in film but in videogames. There are number of game makers who seem to think so.

claustrophobic urban details

One of those is Aloft Studios, who revealed last week that they’re working on a game called Megastructure on the TIGSource forums. It’s said to be an environmental exploration game that mostly relies on the player’s interpretation of its spaces to make sense of the story. But this isn’t a case of reading graffiti written on the walls or investigating a corpse in someone’s overturned office (you know, the usual); the structures to be explored are kept vague, and are said to be “of vast but unknown dimensions and scope, consisting of many layers of accretional industrial systems layed upon one another in an organic fashion over a vast number of years.”

It’s the same technique that Nihei used in Blame!, committing almost totally to the language of space: Blame! is largely wordless, and so the reader must spend their time piecing together the story through an interpretation of the claustrophobic urban details of “The City,” the symbols hidden within the structures, and the spaces between the panels.

Within this, Nihei presents a huge biopolis—a living city—that stretches out for millions of miles and is endlessly being built upon. It is an urban organism that questions our humanist assumptions of architecture, as “The City” doesn’t seem to exist in servitude of humanity, but supports what David Gissen calls “subnature.” Gissen uses this term to refer to entities like smoke, gas, dust, debris, puddles, mud, insects, and weeds—those that traditionally threaten the constitution of architecture—but in terms of Blame! it can be used to refer to the immensity of the city’s architecture and spaces, its many depopulated zones, and the post-humans that dwell within.

left to navigate the circuitous trenches

This same idea of architecture against humanity is described by Aloft Studios when talking about Megastructure. “The environments themselves tend toward the monochromatic (principally through lighting), and have a quality of paradoxical detail and ‘sameness’ simultaneously, which is a kind of mild sensory deprivation,” reads the description. “There is also a tendency for the player to experience long stretches of time in transit through spaces of great scale, rather than engaged in action-oriented tasks.”

The studio acknowledges that this unconventional approach to game design can also be seen in NaissanceE (2014). It is a game that has the player explore a “primitive mysterious structure,” huge in scale, and seemingly devoid of human life. It is a place brought sustained and populated by machines, by light and shadow, and that seems unfriendly towards the player merely by way of the vast layout of the place, which includes infinite staircases and a negligence for proper passageways.

Aloft Studios also acknowledges other similar projects, such as Hiversaires (2013), a point-and-click game by Aliceffekt, the prototype game called ABANDON that never amounted to anything, and another game currently in the works described by its creator as “walking simulator about climbing gray stairs surrounded by gray walls surrounded by gray structures in gray rooms stretching for gray kilometers.” What all these works have in common is that their creators have been inspired by Blame! and looked to transpose its design approach to a videogame. The appeal is obvious: rather than trying to nake 3D sense of Nihei’s spaces as a reader, make the spaces actually 3D and put the player at the center, marooned, left to navigate the circuitous trenches and and sprawling urban ecology by themselves.

You can look for updates on Megastructure over on the TIGSource forums.

The post The influence of Blame! on videogame architecture is rising appeared first on Kill Screen.

Ekko’s pretty spaces will let you explore the butterfly effect

Rob Milus isn’t saying much, but it’s enough. He’s working on a game called Ekko with fellow game maker Peter Dijkstra, one that he’s only showed glimpses of on Twitter—abstract shapes floating across a space lit by a distant sun. I wanted to find out more, a lot more, but he only responded with a few sentences and a finger raised to his lips. “Shhhh.”

Of what Milus told me and that I can share with you, it is that Ekko started off as an interest in the theory of the butterfly effect: “how a small change in one place can evolve and cascade into something much more vast later on,” in his words. Ekko is Milus’s way of creating a format to explore that theory, having players interact with abstract structures and environments in order to discover hidden relationships between various elements. It’s due to this process of discovery that Milus won’t share much about Ekko before it’s finished and out into the world—to do much more would be to go against the point of the game.

Little electronic blips chime in when the player unites shapes

Rather than playing a character in Ekko, players will have an omnipresent role, experiencing its strange ecosystem from a distanced view. From there, players have the ability to influence and mold the space while piecing together small fragments into powerful structures. This might be drawing a line between floating triangles to connect them—Milus showed me this example, and when the triangles were connected, they were sucked into a single point as if it were a black hole to then become a single hexagon.

“As you build up a symphony of these structures, you can use them to set off vast explosive chain-reactions,” Milus said. “Each environment contains different hazards and which forces you to rethink your approach as you make your way through the world.”

Milus and Dijkstra also worked with sound designer Martin Kvale on Ekko. He’s provided suitably spacey soundscapes where strings swell and warm notes float across the ether. All of which seems geared towards coaxing the player into a state of chill and deep contemplation as they play the game. Little electronic blips chime in when the player unites shapes—as satisfying as seeing a tick in a school workbook. But there are also more violent sounds, such as lightning crashes and sand blasts during storms that replace the gentler horizons at some point. In these scenes, those pleasant blips become the hard sounds of shapes colliding at high speed—wet thwacks rather than a pleasing duh-link.

Sound is obviously highly important to Ekko as it is tasked with not only helping to guide the player in their exploratory gestures, but giving a sense of greater life beyond the screen; a world for the sun to shine upon, for the storms to rage across. Milus said that Ekko is still in early production as they’re testing out things with its design still, but from what I’ve seen and heard, it is already a confident project with plenty of intrigue to boot.

Follow Rob Milus on Twitter and check out Ekko’s website for updates on the game. Ekko will be launch for Windows and Mac but will also come to iOS.

The post Ekko’s pretty spaces will let you explore the butterfly effect appeared first on Kill Screen.

Upcoming industrial-age simulator has cities with a personality

When I was a kid, my best friend and I used to spend hours playing various Tycoon games. I remember how excited she was to get the Zoo Tycoon Complete Collection (2003) for her birthday and how we stayed up all night crafting the perfect zoo. This was one of my first experiences with videogames, but also one of my first lessons in playing with capitalism. Inspired by games like Transport Tycoon (1994), Project Automata seeks to kindle that nostalgia and revitalize the genre of industrial simulations.

specific personalities and unique behaviors that change quickly

In Project Automata, you start out with limited resources and a small shop in the golden age of industrial expansion (more specifically, the early 20th century). From there, you’ll need to build mines, farms, and other establishments to gather resources in order to grow.

An aspect of the game emphasized by the game’s creator on its Kickstarter page is the dynamic and advanced AI system. Not only are there the individual characters like your personal assistant and city officials, but there are also the cities themselves, which each have specific personalities and unique behaviors that change quickly and sometimes unpredictably. For example, an influx of young residents could lead to a higher demand for beer, which affects the economy of the town, which will eventually have an effect on you as someone controlling various resources.

Additionally, some towns might be less receptive to things like noise pollution than others. Ground pollution makes a difference too, as the environment responds accordingly to the waste that your industry produces. The creators of Project Automata seem to be taking care into ensuring every little system is affected by the way you choose to build your empire.

Project Automata also lets you choose between collaboration and competition. In multiplayer, you and your friends can work together to build an empire, or you can undermine each other to get ahead. Alternatively, there is a story-driven single player campaign, which provides you with unique scenarios and obstacles to overcome.

Despite failing to meet their funding goals on Kickstarter, developers at Dapper Penguins Studios are still working hard to get Project Automata released as soon as possible.

You can visit the game’s website to download the demo, read updates, and learn more about the game.

The post Upcoming industrial-age simulator has cities with a personality appeared first on Kill Screen.

November 4, 2016

Emporium, an upcoming videogame vignette about suicide

I was expecting Tom Kitchen to be reserved when talking about his upcoming vignette game Emporium. He’s shown plenty of images on the game’s TIGSource thread but not said a lot when it comes to what it’s about, leaving me to believe he wanted to keep it secretive. So I was taken aback when he came straight out with, “overall the belly of Emporium is a conversation about suicide.”

He goes on to tell me that you’ll play a young boy around the age of 12, who speaks with a much older man, both of them victims of suicide at the titular emporium. The game takes place in what is essentially limbo—the place between life and death—where the two characters, unaware of their passing, relive the same conversation over and over. You’ll be able to explore this conversation through dialogue branches.

“I’m keen to look at the parallels between youth and old age, and how much or little your sense of self progresses as you age,” Kitchen told me. “Things are at their clearest when pushed to extremes, so a conversation between a kid and an old man, both at the end of their tether, seemed interesting to me.”

What first struck me about Emporium is its isolated scenes and sharp virtual architecture. Kitchen has constructed a number of vignette spaces—the front of the emporium, a stairwell, a caravan—shrouded in darkness, sometimes with a dead body positioned within them. His skills in visual arts stem from his background in fine art printmaking, which he studied at university, going on to become a screen-printer and illustrator (you can see some of his work here).

“Things are at their clearest when pushed to extremes”

Kitchen only got into making videogames a couple of years ago—leaving his former screen-printing job for the pursuit—which he says is due to the tools to do so becoming more accessible, teaming up with a programmer friend to form Blind Sky Studios. Since then, they’ve gone on to make a four games, including two we’ve covered before: Adam (2015) and Mandagon. Emporium is Kitchen’s first solo game though, which started out a couple months ago as a way to “get more savvy with code, learn 3D modelling and animation.” What was meant to be a two-week project grew as it became more solidified in Kitchen’s head.

Pilot Cinema, King’s Lynn, Norfolk. Image source

He started out with the image of Pilot Cinema above, which was built in 1938 in King’s Lynn, Norfolk, the tiny town where Kitchen attended college. The building was abandoned when Kitchen first saw it for himself, and it was demolished in the summer of 2014, but he attributes it with getting him into 1930s modernist architecture—”lots of aggressive and proud cubes,” is his description. He saw it as a good way to start out 3D modelling as the cubes should be easy enough to place and align. He also took inspiration from constructivism, including the architect Iakov Chernikhov, particularly for his color palettes.

Above, you can see how Kitchen gradually built up the first scene of the game, the outside of the emporium. “I guess it gives a sense of how I block out the scene with basic cubes and geometry, then play with lighting and where to include detail to build it all up,” he said. “I’m working with blender and Unity plus some Unity add-ons to put the whole thing together.”

You can see some of the other scenes in the screenshots below. Kitchen is hoping to be finished working on Emporium soon. He’s working with Richard Jackson, who’s providing the soundtrack with a focus on the solo cello.

You can track development on Emporium on the TIGSource forums. See more of Kitchen’s work on his website and check out his other games here.

The post Emporium, an upcoming videogame vignette about suicide appeared first on Kill Screen.

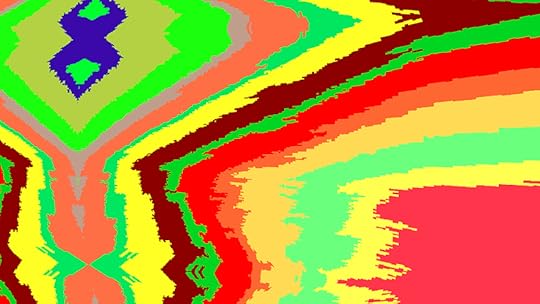

Barnaque’s next game is about the burden of being hopeful

Barnaque is one of the most interesting freeware game studios to have emerged in the past few years. Comprised of the Montreal-based duo David Martin and Émeric Morin, Barnaque has made games that are often described as “batshit crazy” and “psychedelic,” mostly because the pair want to mess with players through game form, art, and mechanics. “What we’ve been trying to do since the beginning of Barnaque is to mess with people’s expectations by establishing patterns and breaking them,” the pair told me over email. “Infini is our strongest attempt at this.”

Infini is the pair’s next game and it will be their first commercial one at that. It’s about Hope—personified as a sickly-looking man—stuck in and trying to escape Infinity. In terms of form, it’s a puzzle platformer in which Hope constantly falls down the same screen due to the game’s use of wraparound, or screen wrap. That means when Hope falls to the bottom of the screen he appears again at the top, the same goes with the left and right sides of the screen.

“the burden of being endlessly hopeful”

You have to navigate between insta-death walls using the screen wrap to reach the exit in each single-screen level. Later on, you’re given the ability to control the camera zoom, steadily revealing more of the level—but there’s a danger of revealing too much and condemning Hope to death if you’re not careful. It’s much easier to understand the concept yourself rather than read an explanation so I’d advise downloading the early Infini prototype on itch.io.

If you’ve played Barnaque’s previous games then you may see Infini‘s structure as a little less experimental than the studio’s established tastes. This is true: Barnaque is looking to “present a game that looks traditional and arcady” at first. Part of this is Barnaque’s concessions to the game’s commercial status. They want to be able to survive making games if they can and they think the more traditional structure will help to reach more players. The other part of this is that they’re hoping to bend that rigid structure in a perhaps more jarring way than their previous games.

While Barnaque is being understandably coy about how this experimental part of the game may play out, they did give some details on how the story will unfold. Infini‘s story will be told across the levels themselves and within self-contained sequences. The former will be in the form of conversations while the latter are short animated interactive scenes such as the section with Memory in the cemetery in the early prototype. You’ll also collect poems inside the levels which will then by read by Poetry, the dog—there’s an example of that here.

“All our games so far take place in the same narrative multiverse inhabited by personified concepts,” Barnaque said. “Infini is set some time after Nulle Part and will feature characters from some of our freeware games. The larger goal of Barnaque is to reveal in a chaotic, puzzle-like way parts of this larger narrative, with different tones and varying degrees of seriousness.” What this means, then, if you haven’t played Barnaque’s previous games—especially 900, Carte, Tombe, Vaiselle Croche, Ouragan, and Nulle Part—you should probably go and do that.

I had to ask about the potential, obvious metaphor of Infini too. My question: is this a game about hopelessness?

“Partly, yes, but it also is about the apparent invincibility of Hope, and the burden of being endlessly hopeful,” Barnaque said. “Placing Hope in Infinity also serves to illustrate the smallness and fragility of a human concept inside an incredibly large and unknown universe.”

You can download the Infini prototype over on itch.io.

The post Barnaque’s next game is about the burden of being hopeful appeared first on Kill Screen.

Find your favorite room amid the chaos of The Catacombs of Solaris

A strategy to use when exploring ruins in Dungeons & Dragons is to hug the wall. Have the beefiest party member (preferably a halfling barbarian) lead the way—not necessary, but a warrior knows how to survive. When presented with the option to turn either left or right, pick the latter. Always. The party will always find their way out eventually, even if it takes two hours.

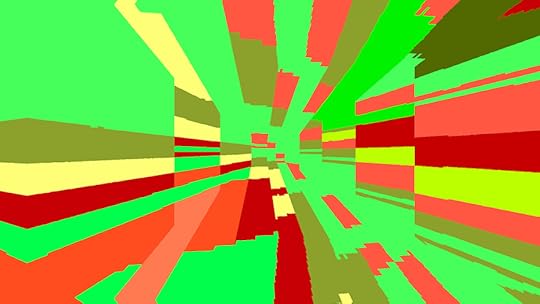

With this in mind, I travelled through the ever-changing environment of The Catacombs of Solaris. It’s a “mind-bending” first-person exploration game created by Ian MacLarty in which the goal is to “find your favourite room in the catacombs.” Taking the D&D approach, I took every right turn presented to me. Although there is no exiting the catacombs, I pictured myself as though I were a guest in a museum dedicated solely to the works of a Jackson Pollock who threw cans of pixelated bits and bytes instead of paint.

Movement was a little disorienting at first. The arrow keys are used to look around as if turning your head, and if there was a room that seemed appealing, it would change shape as you approached. The colors and patterns of the surrounding walls looked as though they were shrinking as I walked towards them.

everything was abstract

The experience was vaguely that of a funhouse attraction that featured mirrors that would bend and warp your figure. Each room had a distinct style. Some looked like TV static. Others looked like marble. But for the most part, everything was abstract. Since there was no music in the catacombs, I was free to create whatever experience I wanted based on the soundtrack I was listening to.

After a little while I was able to find my favorite room. It looked like I placed a kaleidoscope over my eyes and spun around until I became dizzy. Then I turned to the right and began walking once again. The game only asks that you do the same.

To play The Catacombs of Solaris click here .

The post Find your favorite room amid the chaos of The Catacombs of Solaris appeared first on Kill Screen.

Mafia III is a postcard tour of the American South

Tell about the South. What’s it like there. What do they do there. Why do they live there. Why do they live at all.

—William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom! (1936)

One of the currents running through Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, and indeed the Southern literary tradition at large, is the difficulty of telling about the South. In the quote above, Quentin Compson relates a story from his home in Yoknapatwpha County, Mississippi to his Harvard roommate Shreve. As Quentin attempts to untangle a web of hearsay, gossip, legend, and myth, he ruminates on his tired apostleship about “Southernness” as if it can be explained through a complex body of literatures—much less a dorm room conversation. Talking about the South is, more often than not, an exercise in frustration because it is such a loaded symbolic place with a guilt-ridden and complicated history.

This is why I approached Mafia III with a sort of cautious optimism. As a native Mississippian, I’ve often thought of the American South as a place neglected by videogames. Sure, The Walking Dead Season 1 (2012) and Season 2 (2014) offer some good Southern gothic horror, touching on themes of race and place only tangentially in an post-apocalyptic South. Kentucky Route Zero (2013-16), too, takes the player on a tour through the mythic South in a way that draws from the works of Flannery O’Connor or the Appalachian fiction of Cormac McCarthy.

But Mafia III’s New Orleans-style setting (New Bordeaux in the game) and Dixieland crime story potentially offered a digital South from a perspective I hadn’t yet seen. Lincoln Clay, an African American Vietnam veteran, has returned to his home in New Bordeaux only to have his friends and family murdered by the Italian mob for whom they worked. Lincoln recovers, then starts carving his way across the city and claiming turf to weaken the mafia leader Sal Marcano. It’s a revenge tale as direct and simple as they come, but its Southern setting was promising enough to engage with the region’s history and the legacy of its literary giants. Even its narrative structure of a story told in flashbacks and documentary-style interviews show something of a Faulknerian approach to the slippery concept of truth amid rumor in Southern fiction.

All that unique setup steadily erodes, however, when Mafia III settles into a routine that reveals it is not a game about the South but, rather, just a game that takes place there. My first clue was the music. As soon as I got in a car, I fiddled with the radio stations hoping to find some New Orleans jazz. The closest I came across was John Lee Hooker playing his muddy Mississippi delta blues—no Kid Ory, no Professor Longhair, not even a bit of Dr. John. The radio scrambled out a collection of Motown hits and some rock n’ roll anyone could identify as “authentic” for its 1968 time period, but the flavor, the sense of place, wasn’t there.

a guilt-ridden and complicated history

This feeling sank in deeper as New Bordeaux began to look like every other digital open-world city I’ve visited. For every street that approximated a real-world counterpart like Canal or Bourbon, I found something in the city that felt off. The people lacked uniqueness, or the accents did not vary enough. I walked Lincoln around the French Ward, the game’s version of French Quarter, and found it not all that distinct from other digital cities I’ve visited. It doesn’t help that Lincoln never seems to appreciate New Bordeaux as his home rather than a series of sections to conquer, and, consequently, all the trappings of New Orleans serve as set dressing for his war of righteous anger and revenge.

The truth is Mafia III could have been set anywhere because it’s not about the South or even the racial tensions of 1968. Mafia III uses this time and place as guilt-free context for some contemporary catharsis. While there are certainly problems in using the Civil Rights-era South as shorthand for a racist time and place, Mafia III’s deplorable gangsters are so cartoonishly bigoted that the taking of the city can becomes an exercise in guiltless glee. Few videogames can match Mafia III’s grindhouse exploitation thrill of driving a truck decorated with a painted Confederate flag into an upper-class garden party and unloading several clips into members of the Southern Union, the game’s version of the KKK.

The scripted sequences in the game, too, show some understanding of the South’s unique potential for videogame storytelling. A shootout on a riverboat, for instance, spills out into the swamp and ends with the public display of a political influencer’s corpse hanging from the game’s version of the equestrian Andrew Jackson statue in Jackson Square. In another mission, Lincoln blasts his way through a theme park haunted house built from racist depictions of Haitian people complete with zombies and what I assume are rougarou (werewolves from Cajun folklore)—a cheap, vulgar monetization of black and Cajun cultures for white entertainment. Even the sitdowns with Lincoln and his lieutenants take place in an old plantation to mark a shift in racial power for the city. In these moments, the game uses those symbols we associate only with the South to dismantle their established narratives of white supremacy.

it’s not about the South

Unfortunately, between these clever pieces of Southern-fried righteous anger with the rote trappings of modern open-world games, Lincoln accepts missions to disrupt Marcano’s control over the city from stock characters that are met and forgotten in a way that seems at odds with the Southern setting. In killing his way up the mafia tower, Lincoln never comes across as more than a tourist in his own city, going through the motions of every other open-world protagonist: drive to a place, assassinate the gangster, interrogate the snitch, smash or steal the target. Lather, rinse, repeat. Even though Lincoln’s goal is the destruction of New Bordeaux’s Dixie Mafia rather than climbing through its ranks, any sort of pretense of profundity in his revenge-porn rampage gets lost in the numbing patterns of open-world tedium.

Ultimately, Mafia III is a game that’s held back by its conventional anchors. It wants to be game about the South but remains content to use its setting rarely as little more than a local color curiosity. It proposes a radical representation of race but falls prey to the conventional chores of open-world banality. Though it initially seems eager to “Tell about the South,” Mafia III does not have the patience or interest to do so. Its violence and exploitation-style racial politics, however, make the trip to New Bordeaux worth effort—as long as the person heading down South isn’t looking for anything more than a sightseeing tour.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Mafia III is a postcard tour of the American South appeared first on Kill Screen.

November 3, 2016

Take in the sights of Trackless’s surreal sci-fi world

You might not have heard of Aubrey Serr but it’s possible you’re familiar with some of his work. For the past eight years, he’s been a designer over at Wolfire Games, mostly working on the still unfinished Overgrowth—the game with the ninja bunnies—but also helped contribute to the studio’s 7DFPS entry Receiver (2012), which tried and succeeded to install more true-to-life complexity to gun handling in videogames.

Now Serr has given all that up and decided to form his own studio, 12 East Games, and set out to work on a game called Trackless. It’s a game that’ll give you a phone and a destination and let you set out on an ambient journey into the mountains to face a series of trials. More specifically, you play a Seeker in the distant future in search of an artifact simply called The Object, hoping to reveal “the truth behind this monolith.”

there’s already a love for detail on display

Other than walking around, the main interaction in Trackless seems like it’s related to the phone you carry around. You use it to interact with the world, its objects, and the characters using its text input (this is where the inspiration from classic 1980 text adventure Zork shows itself). You’ll also face challenges that apparently make use of your understanding of language. Plus, through exploration and solving puzzles, you’re able to earn currency, which in turn lets you buy updates for your phone and acquire superpowers. You also use the currency to buy your way into new areas.

Admittedly, that’s not a lot to judge the game on, it painting quite a vague picture of it overall. However, there is a trailer (above) and some screenshots that should help along with the process of garnering interest in Trackless—they certainly helped me. What’s intrigued me the most is its world, which Serr says in that trailer is a “strange future inspired by real places and ideas.” There’s not much in the way of clues as to what these places might be, but the screenshots show a pre-production version of a small industrial village in the desert—and I think I see what appears to be some classic Red Rock Canyon iconography populating the backgrounds.

Most strikingly, especially for a game that in its current state is mostly made of blurry textures and scratchy ink drawings (which I hope remain in the finished version), there’s already a love for detail on display. Look at the lights in the library, which have bulbs carried on the backs of small men, as if in homage to Sisyphus. And the electric wires, pipelines, and speaker systems that seem to have been connected to a power station in the background, and from there properly embedded into the environment as if water and electricity needed to actually coarse through them.

There’s a proper sense of cohesion in all these details, as if a magnifying glass has been held up to plans of this settlement when the nib of the pen was committed to the paper. But Serr and his team also show that they can do scale too, pulling the camera back to capture a truly alien horizon, where a dark sun is getting ready to nest into a misty, mountainous terrain. It feels bold, surreal, and belongs to a tradition of sci-fi art that outlasts the generation it was produced in. And that mood is set to be matched by the music, which is being composed by Makeup and Vanity Set, the people behind the glossy synths of Brigador.

Anyway, it’s too early to say anything about Trackless beyond it looking promising. It’s currently on Fig, where $20,000 is being raised to fund the game’s production. You can secure yourself a copy for when it comes out early next year.

You can support Trackless on Fig and find out more about it on its website.

The post Take in the sights of Trackless’s surreal sci-fi world appeared first on Kill Screen.

Night Call will bring you stylish French noir from the back of a taxi

Night Call‘s shade of noir-infused drama seems to be one part Drive (2011) and two parts Taxi Driver (1976). Upcoming for PC, iOS, and Android, Night Call will have you playing as a Parisian taxi driver who hopes to find the killer who has orchestrated a number of recent murders around the city. But you don’t do this in the usual videogame way—shootouts in industrial wastelands, chasing a black figure across a rooftop—the whole game takes place inside your taxi.

the game uses a real city map for you to drive around

Monkey Moon and BlackMuffin Studio, the two French studios collaborating to make Night Call, explain that in your role as night-time taxi driver, the people you pick up sometimes talk to you as they would a priest or, at least, a friend. They’ll speak what’s on their mind and confess to things they perhaps wouldn’t otherwise if you weren’t a transitory entity in their life. It is the information that you can acquire in these moments of dialogue that’ll help you to track down the killer—a goal the taxi driver is motivated towards as the victims were all previous customers, and he was the last person to see the latest victim alive.

While this may sound part-and-parcel for a videogame mystery, even if it is dialogue- rather than action-based, what makes it a little different is that the passengers who appear in the back seat of your taxi, and they order they arrive, isn’t scripted. It’s all randomized. This means you have to be attentive to each person’s thoughts and reactions at all times, open to the idea that not everything you hear and see will be a lead—”Some of them know things about the killer, others pretend to know things, and some just need to talk to someone,” tease the game’s creators. You’re not tasked with simply following a trail of neatly-arranged breadcrumbs laid by the game’s creators, but more actively trying find the signal amid the noise.

On top of that, Night Call also “aims to show the city of Paris like it is in reality,” not the cliché of the city of love, but what the game’s creators describe as a “gigantic city, always in movement, and full of very different people.” Hence the game uses a real city map for you to drive around—40.5 mi² in total apparently—which will demand you use the clues you collect to guide your investigation into the murders, looking for certain locations and specific people that might lead you closer to finding out the identity of the killer.

You can find out more about Night Call on its website. No release window has been given for it yet.

The post Night Call will bring you stylish French noir from the back of a taxi appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers