Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 141

April 1, 2016

Tokyo 42 takes cyberpunk fiction to its prettiest city yet

Tokyo 42 is cyberpunk in all but look. Its future vision of Japan’s bustling capital city has none of the dead skies and drug-addled misery of William Gibson’s Chiba City, nor the clustered smokestacks and commercial traffic of Blade Runner‘s (1982) Los Angeles. Yet, it’s a game that has you running through the Tokyo population as an assassin—in both single player and multiplayer modes—popping off targets with grenades and sniper rifles, able to change your skin (presumably a cyborg ability) to blend back in with the crowds. The brief description of the game’s story also tells us that you’ll “uncover a dark conspiracy that will affect everyone.” This is all very cyberpunk.

tutti-frutti high-rises and pleasantly traditional Japanese temples

Perhaps the visuals fall in line with a more modern type of cyberpunk, then, one that is informed by today’s reality more than the fictional predictions of it helmed from the 1980s. While the tutti-frutti high-rises and pleasantly traditional Japanese temples are seemingly at odds with the underlying dark themes of Tokyo 42, there’s something familiar about this clean-cut friendliness. If cyberpunk informs us to mistrust corporations, especially those with the most power over people, then we must look to the likes of Apple, Google, and Facebook. These are companies that collect our information to use it and sell it to the highest bidder, that push out new technology with a higher price tag each year, somehow convincing us that we need to replace the older shit we bought only months ago.

If we are living in a cyberpunk dystopia these days—and there are those that argue that we do—then we have to acknowledge that it doesn’t share the dated vision of electronic wires criss-crossing overhead and people using hacking devices that belong to the VHS era. Sure, we have the smog and the skyscrapers plastered in adverts, and there are plenty of drugs and addictive chemicals doing the rounds, and the homeless do indeed line the streets. But, for the most part, the dark heart of the would-be corporate villains of today isn’t reflected in the make-up of our cities so much as it is hidden behind the polished veneer of them. The Silicon Valley giants that rule the world today do so by purporting to be our friend. They want us to “be connected,” to “be discovered,” (as the Facebook slogan goes) and to use their software to do so—but connected to who? They say it’s to our social friends but it’s more than likely to other corporations that will pay a high price for our personal info.

The Jetsons-style bubble cars that fly by Tokyo 42‘s boldly colored and neatly arranged architecture smacks of the optimism of 1950s futurism. But underneath all that is conspiracy and corruption, beating away like the dark heart of a serial killer who wears a fake smile as they mingle with the rest of the population. All that aside, it also makes for a city that has a similarly immediate visual appeal as Monument Valley (2014), viewed as it is from an isometric perspective as per its inspiration in the 1993 cyberpunk game Syndicate. Oh, you can also be a cat, as if you needed any more reason to be interested in this game.

Tokyo 42 is due out in 2017. You can find out more about it on its website.

Nintendo is interested in VR. Just not how you think.

This is a preview of an article you can read on our new website dedicated to virtual reality, Versions.

///

In 1990, the word “Nintendo” was the generic trademark for videogames. A quarter-century later and Nintendo is now just one voice among many in a chorus that too often sounds like a single note of varying volumes. To survive so long, Nintendo have had to play an exotic chord or two, pushing in directions beyond what is expected. Their most recent key change, the Wii U, never caught on with the mainstream public; rumors point to production ceasing after only four years on the market. Today, a new kind of virtual reality is the expected response to our stagnant screens, an answer to the stultifying format of another box and another controller. Every other major platform holder with a stake in this industry—Sony, Microsoft, Valve, and VR prime mover Oculus/Facebook—is bringing some form of virtual or augmented reality to market this year. At first blush, Nintendo appears to be sitting this song out. But look more closely and realize that Nintendo, long before Oculus CEO Palmer Luckey was born, has always endeavored to virtually enhance our reality.

“When you think about what virtual reality is,” famed developer and long-time Nintendo guru Shigeru Miyamoto said at E3 2014, “that’s in direct contrast with what it is we’re trying to achieve.” VR attempts to recreate a place that’s entirely unreal to inhabit. Nintendo looks at the real thing in front of you and asks how to imbue that with something special. Sometimes it’s a controller that, for the first time, makes you feel the action on-screen. Sometimes it’s a watch that’s really a game-playing device. Sometimes it’s a game-playing device that’s really a camera. Satoru Iwata used to say that Nintendo’s goal is to “surprise and delight” their players. But they never do this by sheer force of power; they do this by hiding in the background and pulling levers no one else sees.

Engare, a videogame about the mathematical beauty of Islamic art

Iranian game maker Mahdi Bahrami is the kind of person who answers a question with more questions. I don’t think he can stop himself. “What will happen if I add a short line to one of the tiles in a mosque?” he asks me. “If we take into account the tiling rules of the mosque, what would the whole wall look like after we add the line? What if we change the rules? What would the mosque ceiling look like?” I don’t know. But for Bahrami, that’s entirely the point—his upcoming puzzle game Engare is about exploring this unknown space and finding the answer.

Engare started out life as a question posed by Bahrami’s high school geometry teacher. This teacher asked the class what shape would be traced by a point attached to a ball if the ball was rolled across a surface (it’d probably be a series of loops). Years later, this same question essentially serves as the concept for Engare, except it asks you to experiment with more than just a ball, becoming more complex as you progress. Each level gives you an incomplete pattern and you have to figure out how to, well, complete it. To do this, you attach a point to one of the objects in the level and then, when you press play, hope that the point’s movement upon that object draws the shape you’re after. If it doesn’t, you rewind, move the point somewhere else, and so on—you can see an early prototype of the game in action here.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that Bahrami’s first love is mathematics. The second is programming. This shows effusively in Engare: a game about using a computer simulation to visualize the answers to mathematical problems. However, the game is also shaped by his native culture, with the patterns that you draw coming to form as beautiful pieces of Islamic art. The leap from the bare bones prototype to it becoming a game about creating art was a small one, given that Islamic art is steeped in mathematical knowledge. That Islamic art bares its mathematical systems so openly and elegantly is something that Bahrami loves. He contrasts it to a lot of figurative art in which you don’t see many mathematical systems at play: “I’m not saying the human body is not an interesting subject. But a human sculpture, for example, doesn’t show us all those interesting systems that form the human body. When we make a game about a guy jumping on platforms, normally we won’t get a lot of interesting answers about the human body.”

Engare is closer to the expressive creativity of a drawing tool

The visual flair of Islamic art also helps to further ensure that Engare doesn’t ever feel “dry.” Yes, it’s a game about math, but there are no dull equations to solve. Yet, the same ideas that those equations belong to are approached in Engare, just from a different angle and one that Bahrami reckons can also evoke emotions. “There are geometrical shapes that make us feel happy, patterns that make someone nervous/hypnotized, the tiling of a ceiling can make someone feel lonely” he says. In fact, Engare is closer to the expressive creativity of a drawing tool than the cold numbers of an abacus. This is why, when Bahrami was showing the game to a graphic designer friend of his, he was encouraged to take the puzzles out and let the player explore the art of drawing shapes with the game’s tools freely. Bahrami fully dived into this and has since created a separate drawing tool (among other software) based on Engare that people can use to create original art.

Interestingly, while the connection between the swirling lines of Engare and Islamic artwork and architecture was too strong for Bahrami to turn down, it seems he had some doubts about committing to it. The reason being that Engare is, in fact, Bahrami’s second game based on his cultural heritage. His first was Farsh (2012), a puzzle game that had you rolling out Persian carpets in such a way as to create paths across the levels. As fascinated and appreciative of it as he may be, Bahrami is looking to avoid being pigeonholed as the guy who makes games about Islamic art. Hence his next game after Engare avoids it altogether. Called Tandis, it’s inspired by Celtic shapes, and is a wild and unpredictable experiment in topographical transformation—we had a chance to find out more about it at GDC.

As to Engare, Bahrami is hoping to get it out for PC and mobile this summer. At the moment he’s working on finalizing the iOS version.

You can look out for updates to Engare’s progress over on its new website.

Take a look at Rollovski, the adorable Simogo game that never was

Recently made available for free over on their blog, Simogo’s Rollovski is adorable, clever, and unfortunately, only four levels long. The game, an unreleased prototype, stars a round, limbless detective of the same name, following him on his journey to infiltrate a strange hotel made up entirely of circular rooms. Along the way, players must avoid capture from spotlights and, like in the Sonic the Hedgehog series, build up enough speed to roll around the environment’s many loops. Unfortunately, like its ball-shaped main character, it was never quite able to get off the ground.

Rollovski‘s story begins in 2012, when shortly after releasing their iOS puzzle game Beat Sneak Bandit, Simogo began working on two prototypes. One would become their moody 2013 horror game Year Walk, while the other went through a number of iterations before being built. Concepts included ideas called The Great Ziorawski Acrobats, Common Sense Police, and My Triangle Friend, but the team eventually settled on Rollovski as their final choice, hoping to use it as a chance to work with the Nintendo 3DS.

As such, the prototype was built around two of the 3DS’ most prominent features: the stereoscopic screen, and the circle pad. With the stereoscopic screen, Simogo hoped to set the game across different layers of depth, having players jump from foreground to background across their journey. For the circle pad, meanwhile, they took inspiration from their previous title Bumpy Road (2011), using it to control the game’s environment rather than Rollovski himself. By moving the circle pad in their direction of choice, players could tilt the circular rooms around Rollovski, rolling him around with a 1:1 level of control.

adorable, clever, and unfortunately, only four levels long

Although Rollovski never made it past the prototyping phase, Simogo has now released the prototype for free on PC and Mac. Though it’s not quite a 3DS circle pad, players can control the game using either a keyboard or an Xbox 360 controller. Additionally, Simogo has released two 3D-capable screenshots which players can view on compatible devices. Finally, an excuse to actually use the 3D on my 3DS.

Because of its focus on bite-sized puzzles, colorful presentation, and portability, the team saw Rollovski as a sequel of sorts to Beat Sneak Bandit, which featured a similar design philosophy. Since then, Simogo has moved on to larger, more introspective narrative experiments like Year Walk and Device 6 (2013), but Rollovski is a delightful peek at the direction they might have taken if they had continued the more upbeat style they had developed with Bumpy Road and Beat Sneak Bandit.

You can learn more about Rollovski over on Simogo’s blog.

The Furry takeover of media

It wasn’t until I was halfway through the Korean visual novel Dandelion – wishes brought to you – (2012), when I had already spent hours trying to get in the pants of a guy who had previously been a black cat, that I began to wonder if I was actually a Furry.

Jisoo, the object of my affection in Dandelion, is not anthropomorphic in the traditional sense; rather, he is either in black cat form or, when under the influence of magic, a human body. Even in his human form, however, he retains his black cat ears, his love of food and napping, and his hatred of water. His default, normal form thus appears to be his cat form, and yet, upon reaching the “good” ending and winning his love, he is transformed into a full human. At a moment when the celebratory ending music blasts and the player should feel fulfilled by their prize—seriously, the stats-raising system is hard—I felt deflated.

I missed his cat ears.

///

A trend has seemingly emerged in visual novels, both in Asia and North America, involving the use of animals as love interests. Visual novels are nothing new; they’ve been around since at least 1994. But visual novels featuring animal romances have seemingly only just begun to surface, with most cropping up in the past five years.

VISUAL NOVELS FEATURING ANIMAL ROMANCES HAVE SEEMINGLY ONLY JUST BEGUN TO SURFACE

In these visual novels, the main character’s pets—either through magic or a dark curse of some kind—transform into humans, often retaining their animal personalities, memories, and traits. They can communicate and reason like humans, the visual novels usually explain, but their animal form, for obvious reasons, makes it difficult for the animals to connect to people—that’s where their human forms come in. These kinds of visual novels appear to be growing in popularity, filling a niche that apparently needed to be filled. We’re talking the Furry niche.

A Furry (a term coined back in 1980) is generally someone who shares some level of interest in or affinity for anthropomorphic characters. And no, that interest does not have to be sexual in nature; the Furry community has unfairly gotten a pretty bad reputation over the years, being painted as deviants in fursuits and ”proponents” of the infamous Rule 34. The stereotype is far from the truth: the sexuality of a Furry, like any other person, is a broad, broad spectrum ranging from the innocuous to the maybe not-so-innocuous.

Zootopia image via Vimeo.

Other forms of media have embraced the Furry theme, in all its subtle variances, far before visual novels. Sure, on one side of the spectrum is Space Jam’s (1997) Lola Bunny, whose exaggerated sexuality, uh, jump-started puberty for many of the movie’s young viewers, leading to things like a Facebook group dedicated to the “sexual tension between Michael Jordan and Lola Bunny.” But these sexualized, not-so-innocuous forms of Furrydom are seemingly few and far between.

Examples of the more prevalent innocent “Furryish” themes include Disney’s 1986 animated film The Great Mouse Detective, whose main character Basil’s dulcet voice and charm made his viewers (which may or may not include myself) forget he was a mouse. And it would be remiss to forget the weirdly hot fox Robin Hood from the eponymous 70s Disney film, one of the first big anthropomorphic animated films that continues to inspire animal-loving filmmakers. Such inspired films include the new Disney animated film Zootopia, whose production team has actively called on the Furry community to represent the world of Zootopia itself by appearing at movie viewings in full Furry costume—it’s one of the first public acknowledgements that Furries are a big percentage of anthropomorphic film consumers. But, in line with the movie’s theme of embracing diversity and inclusivity, it’s an unprecedented move that’s also an intelligent one.

VISUAL NOVELS WITH ANIMAL LOVE INTERESTS FORCE THEIR AUDIENCE TO QUESTION THEIR OWN SEXUALITY

Over in Japan, in Studio Ghibli’s movie, The Cat Returns (2002), the protagonist Haru admits to having a “little crush” on Baron, her savior throughout the narrative. Baron politely acknowledges her feelings, and ultimately, nothing comes out of her admission partially because Baron is a cat—a suit-wearing, British-accented talking cat, but a cat nonetheless. But by then, even the viewer has likely formed some level of admiration for the chivalric Baron. This potential romance between a human and an anthropomorphic cat did not deter viewers; there was no public push-back against the “weirdness” of a girl and a humanoid cat in love. Hell, The Cat Returns was the highest-grossing film in Japan when it was released.

However, visual novels present a much bigger issue in that they call upon their readers to actively engage in romance with an anthropomorphic character, as opposed to films whose viewers are just complicit, passive consumers. Visual novels with animal love interests force their audience to question their own sexuality, their potential affinity for anthropomorphism, and to inevitably bring up the larger question of what it means to be a human. So where does one draw the line between what is “human enough” to romance and what creeps into Furry territory?

To even come close to an answer, one needs to know what exactly constitutes anthropomorphism. If anthropomorphism is defined as applying human characteristics to a nonhuman entity, is an animal trapped in a human body “anthropomorphized”? At least in the case of Jisoo (my lovely black cat-man-boyfriend), arguably, he is anthropomorphic: at his very core, he is a cat that, for the near entirety of the game, is trapped in about 99 percent of a human body. His personality as a cat is not altered by physical form; his cat identity still exists, but has merely been given human bodily characteristics. When you romance Jisoo, you’re not romancing a human—you are, regardless of the form of his body, romancing a cat with some human traits. And that makes you sound like some degree of Furry.

In the case of Hustle Cat, a visual novel recently (and quickly) funded through Kickstarter, you date humans that are cursed and transform into cats whenever they leave the cat cafe, the setting for the game. Here, the romanceable characters are not necessarily anthropomorphic because, at their core, they are truly human. At the same time, the “romancing” scenes still occur regardless of what body the love interest is in. One scene includes the main character blushing upon carrying one of the love interests in cat form, as though carrying the love interest in cat form was a romantic act or a suggestive bodily intrusion.

THE WIDESPREAD NORMALIZATION OF THE VARIOUS DEGREES OF FURRINESS

Most visual novels featuring animals as love interests relatively follow the same narrative thread as Dandelion, differing only in the kinds of animals you can date. Forbidden Romance: My Secret Pets (2015) and Animal Boyfriend: Paws & Tails (2012) both also feature another main character whose pets transform overnight into an attractive reverse-harem of her own. Though human, the romanceable pets-turned-humans keep some of their animal characteristics, like rabbit ears or hooked noses purposefully resembling bird beaks. And if cats, rabbits, and birds are not exotic enough for your tastes, try playing Beastmaster and Prince -Flower & Snow-, produced by Idea Factory, developers of arguably one of the most famous visual novels of all, Hakuoki (2010). In Beastmaster, which takes place in an A Thousand and One Nights-type setting, you can romance a goddamn lion or a duck for some reason while simultaneously trying to break the curse that traps those love interests in animal bodies.

That the visual novel giant Idea Factory is jumping on the animal-romance train is significant, and signals the permeance of this particular romantic theme in visual novels. Even Hatoful Boyfriend (2011), a visual novel about dating eccentric talking pigeons, currently has a 9/10 user rating on Steam and a cult following that resulted in an HD remake, comics, and plush toys. With developers located as far-flung as North America, Japan, and South Korea creating visual novels featuring romanceable pets-turned-human, perhaps the Furrydom can no longer be treated as an underground culture defined by its unique fetish. Instead, perhaps the growth of these games signals the widespread normalization of the various degrees of Furriness.

The popularity of the theme makes sense. The romanceable pets-as-humans theme in visual novels is in line with recent studies which have shown that anthropomorphized characters more effectively trigger feelings of empathy than an entirely human character, allowing visual novel players to more quickly and naturally form an attachment to those characters. One study conducted back in 2007 tested the potential relationship between perceived human-likeness and levels of attraction toward a character, and concluded that “the safest combination for a character designer seems to be a clearly non human appearance with the ability to emote like a character.” Likely, the effectiveness of anthropomorphic characters to effectively facilitate feelings of love in players is what visual novel developers are capitalizing on: making attractive mostly-human characters, but adorned with adorable cat ears and a tail, which more likely guarantees the player’s love and money. And by giving the animal love interests the ability to fully transform into humans at some point in time, actively blurring the line between human and animal, visual novel developers are allowing their players to act upon their romantic attachment without either the visual novel being deemed to target Furries, or the player being labeled as “Furry.” After all, the word carries quite a stigma. Just ask Tony the Tiger.

Maybe we, as humans, anthropomorphize non-human beings as a reflection of our own arrogance because, in our minds, loveable beings must have human traits. But these visual novels suggest another reason for the popularity of animals as love interests in visual novels: the desire to connect to and actively engage with creatures beyond ourselves using our own agency and decision-making process, and without judgment from either other consumers or the love interests themselves.

ANTHROPOMORPHIZED CHARACTERS MORE EFFECTIVELY TRIGGER FEELINGS OF EMPATHY THAN AN ENTIRELY HUMAN CHARACTER

We love to love animals. Pets make us happy, unconditionally; anthropomorphism allows humans to rationalize a pet’s or character’s actions and accept them as a social companion despite them being a nonhuman entity. The popularity of animals as love interests in visual novels likely means a growing consumer base, which also likely means a growing acceptance of and desire for this kind of narrative theme. By romancing these anthropomorphic characters, we are given the unconditional love of a pet, but with all the perks of dating a human.

March 31, 2016

Death’s Gambit finds the humor in its deadly medieval world

Death’s Gambit, the upcoming medieval action game from developer White Rabbit, likes to wear its influences on its sleeve. Like the recently released Salt & Sanctuary, it’s part Dark Souls (2011) and part Castlevania, sending players into a brutish world that could not yell “here be dragons” any louder. And yet, according to the latest post on the game’s development log, it also seems to have a tongue-in-cheek sense of humor amid all the danger.

The post itself is short, simply reminding players that the game is still alive and letting them know that they can expect a new trailer soon. With it, though, comes a series of new gifs mostly focused on the game’s shields. There’s one that lights up dark areas, and another with a parry that swats foes away like Jason Smith stopping a slam dunk. My favorite, though, might be the turtle shield, which instantly transforms the game’s stoic protagonist into a child hiding under their covers to escape from monsters.

Its official function is to block attacks from both sides, as the player cowers underneath a literal turtle shell while using it, but its effect is to give the game some tongue-in-cheek levity befitting its publisher, Adult Swim. Like Metal Gear Solid’s trademark cardboard box, it manages to find the humor in an otherwise serious world, and I couldn’t be more on board with it.

Death’s Gambit will be at PAX East later this April. You can find more information over on the game’s devlog.

Grind through creamy, dreamy skatescapes

I have a lot of memories with the Tony Hawk games. The Tony Hawk series, perhaps most notably Tony Hawk’s Underground (2003), represented a scrape-and-bruise-free foray into youthful anarchy. Tony Hawk’s skateboard games were the anti-sport for kids like me that didn’t have any sports of their own to partake in. As it was hard for me to find enjoyment in cars driving in circles like my mom and her boyfriend often did, I stuck to watching skate videos, thumbing through Thrasher, and becoming the Deltron 3030 bumpin’-virtual pro skater I always knew I could be.

An homage to the skate spots Mendoza himself has visited in his country of Nicaragua

For freelance 3D artist and game developer Juan José Mendoza, a similar personal sentiment is peddled into his upcoming skateboarding game The Creamy Dreamy Skate Adventure. Though the game is not borne of a retrospective tinge of nostalgia, it exists as an homage to the skate spots Mendoza himself has visited in his country of Nicaragua. The Creamy Dreamy Skate Adventure is effectively a home for Mendoza, and a peek into Nicaraguan skate culture for the other countries spaced far, far away.

Real life doesn’t exist within the pearly pastel hued filter that Mendoza’s crafted for his game, but it doesn’t have to be starkly accurate in its depiction of real Nicaragua sites. Mendoza’s visions of his home country shine through its effervescent color scheme, and balance the rough realities of skateboarding with the game’s soft, welcoming appearance. Right now, the game exists only as an alpha, with Mendoza promising to create “more cute girls” as playable characters, finish levels, write a story mode, and overhaul the graphics for its eventual full release.

The game has another charming, unexpected-for-a-skating-game aspect: the player is a girl. She has a bright pink board, carries a cute bunny-eared backpack, and wears a skirt plastered with the face of a certain attitude-stricken Sanrio character. In spite of the girl’s delightfully adorable appearance, she’s ready to grind and kickflip her way into a combo glory, just as the boys in Tony Hawk before her.

You can download the alpha for The Creamy Dreamy Skate Adventure on itch.io for free , and follow Mendoza’s development via his Twitter .

Imaginary skyscrapers belong in a videogame

An architecture journal announces a competition to design hypothetical skyscrapers. Anyone can enter. 489 teams do. What could possibly go wrong? Here, then, are the 3 winners and 21 honorable mentions from eVolo’s 2016 Skyscraper Competition. One might even argue that it’s a glowing success.

Sure, the winner of this skyscraper competition, Yitan Sun and Jianshi Wu’s “New York Horizon” is actually a subterranean structure, but who among us could possibly get hung up on such ontological pedantry?

try to say it doesn’t feel videogamey

And sure, “New York Horizon” would create new and exciting public spaces by dropping Central Park below street level thereby making it all but impossible to just walk right in, but just think about the extra square footage (80 times more than the Empire State Building) and rock climbing opportunities! Oh, and whatever you do, don’t think of what’ll happen when sea levels rise. So much not to think about.

What’s a skyscraper anyhow? If your architectural sensibilities have been weaned on city- or tower-building games like the upcoming Block’hood, you might just say it’s a stack of things—boxes that perform discrete functions—and call it a day. That rhetorical shrug, it should be noted, is basically a Bjarke Ingels pitch: Here are all these functions that have been stacked in an interesting manner, and maybe twisted a bit.

Up to a point, this truism is…well…true. All buildings are, in a sense, stacks of things that eventually take on some larger form. Therein lies the appeal of Lego architecture, or its Minecraft (2011) equivalent, or even the venerable city-building game; there is meaning and beauty in artful stacking. There is, moreover, more to architecture than this stacking metaphor, which is why videogame architecture isn’t exactly the real world.

And yet, look at this and try to say it doesn’t feel videogamey:

new renderings from Eliot Spitzer’s Wburg development look like the worst map in a bad FPS https://t.co/iUiGQcYyj0 pic.twitter.com/keEvPTyS8a

— Brendan O'Connor (@_grendan) March 29, 2016

Look at Soomin Kim and Seo-Hyun Oh’s honorable mention “Sustainable Skyscraper Enclosure” and try to say it isn’t Norman Foster’s Gherkin if it existed in Final Fantasy:

Look at Paolo Venturella and Cosimo Scotucci’s honorable mention “Global Cooling Skyscraper” and try not to notice that it could be drawn from Simon Stålenhag’s Tales from the Loop:

A skyscraper is just a stack of things, so let’s just call it a day.

Revisiting the gloriously weird games of Australia’s golden age

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

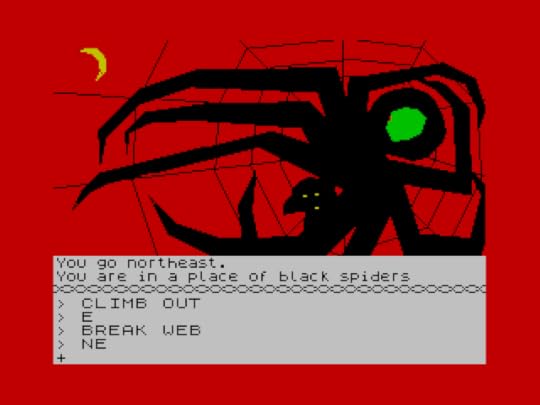

The Play It Again project preserves Australian games from the 1980s, one of the most creative and bizarre times for designers in the country. A collaboration between several universities and museum partners, the Play it Again project seeks to digitally preserve—and in the process, reintroduce—Australia’s illustrious videogame history. By making these great Australian games more widely accessible, the project reminds audiences of just how big a hand the country had in shaping game design during the era of power-suits and synthesizers.

“We want to save Australia’s important screen history, and we want to remind Australians that we had a very early games development industry, and it produced some extraordinary games in the 1980s,” said Helen Stuckey, who works in tandem with Flinders University leader Melanie Salwell on the project. “They were pioneering games,” Stuckey said about Australian developers of that time. “We have The Way of the Exploding Fist (1985) and The Hobbit (1982). The Hobbit was one of the earliest licensed games that we’re aware of. The book was even packaged with it. Exploding Fist was one of the earliest fighting simulations for the home computer.”

The Hobbit was a huge commercial success, too, as the first million-copy seller on the ZX Spectrum, and was also ported across nine other platforms. The game’s design even proved to be a precursor to key elements of modern day open world games like BioWare’s Dragon Age, Mass Effect, and Baldur’s Gate series. Hobbit designer and programmer Veronika Megler created a highly complex system of interactions where non-playable characters would ‘play’ the game alongside the player based on different sets of behaviors. So, for example, the player could ask a character like Thorin to “Go into the goblin’s cave and get me the ring.” But Thorin may or may not feel inclined to listen, depending on how the player had treated him. If the player had tried to attack Thorin, for example, the request may not have gone over well.

“All kinds of things could happen in the world that couldn’t be imagined,” Stuckey said, explaining the brilliance of this system. “Gandalf could go off and get killed by a warg, because both the warg and Gandalf had behaviors in the game.” Dynamic relationships with non-playable character are now a pillar of most open world games. But at the time, The Hobbit perfected and popularized the concept. But Megler’s success begs the question: Where have all these legendary Australian developers gone?

“We want to save Australia’s important screen history”

“Australia is not particularly good at the moment at supporting mature, very experienced game developers,” Stuckey sighed. “Some of them have had to leave just [to find] work.” She points to well known creators like Matthew Hall as one of the few designers who remains active in the country today. Hall worked at KlickTock, Mighty Games, and most recently was part of the small team behind the hugely popular mobile game Crossy Road (2014). Back in the ‘80s, he was a prolific home-coder, and contributed to Play it Again with some of his earliest work from primary school created on the Commodore 64. He also added a listing of a text adventure created on his school MicroBee called Jewels of Sancara Island.

“We put that up [on the Play It Again website] as the listing he had printed on his school’s dot matrix printer. Allan Laughton from the MicroBee Software Preservation Project found it and OCR’d [short for Optical Character Recognition, which converts printed text into machine-encoded text] the listing, tidied up the code a bit, got the audio working. And you can actually now play Matthew Hall’s Jewels of Sancara Island, written when he was, I think, 9 years old or something.” Of all the Aussie developers that pop up across Play It Again’s catalog, one name pops up more than most: Beam Software. At the end of the 1980s, the prolific Australian studio Beam Software became one of the first companies outside Japan to get a license to develop for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES).

“That completely changed the studio,” Stuckey explained. Prior to this, Beam Software had been making their name with games inspired by the great loves of various staff members: Designer Paul Kidd compulsively devoured the comic book Usagi Yojimbo (1984-present), so he helped turn it into a game: Samurai Warrior: The Battles of Usagi Yojimbo (1988). Programmer Gregg Barnett was not averse to sporty fisticuffs, and so created The Way of the Exploding Fist and Rock n’ Wrestle (1985). The former would go on to win Game of the Year at the 1985 Golden Joystick Awards, and it wasn’t long before Nintendo came calling. “Gregg tells these hilarious stories about when they got the NES license,” Stuckey said, laughing. “They’d just get calls from all kinds of people.”

A pizza company from America requested they make a game about the character on their pizza box, while a sultana company wanted a game about belly dancing. None other than Axl Rose himself reached out to create a Guns N’ Roses game starring Axl as the Antichrist. Beam Software even received requests from Madonna’s representatives. “But then I think her Sex book came out and her management was like, ‘Oh no, we can’t do it,’” said Stuckey. The 1980s was truly one of the oddest and greatest times to be an Australian game developer. The Play It Again project hopes to port their extensive catalog of memories to browsers sometime next year. Hopefully, easier access to Australia’s rich gaming history will help preserve these masterpieces for years to come.

The adventure game you don’t want to miss

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Samorost 3 (PC, Mac)

AMANITA DESIGN

Music, nature, and animation come together as one in Samorost 3. Yes, perhaps more so than in many other videogames. Your cursor doesn’t just point-and-click, it ruffles bushes, causes alarm to sleeping birds, and picks mushrooms. It’s your entry into a tangible universe, split across several planets and moons, all of it woven together by photographs, wood sounds, and hand-animated dream sequences. Your direct task is to help a space gnome return a flute that dropped from the sky to its origin. But, implicitly, your task is to explore the knots and hidey-holes of this bug-infested fairy tale. You conduct singing lizards, operate organ-like watering machines, and fight a three-headed mechanical creature of legend. With Samorost 3, a game made in the Czech Republic, we see the continuation of the “tactile art” of animation greats like Jan Švankmajer and Hermína Týrlová. It’s an adventure game of cultural importance not to be missed.

Perfect for: Nature lovers, John Muir, foragers

Playtime: Four hours

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers