Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 137

April 12, 2016

Quantum Break is better TV than videogame

In Remedy Entertainment’s Max Payne (2001) and Alan Wake (2010), the player can approach television sets and watch short, surprisingly detailed videos. In Max Payne, these include soapy melodrama Lords and Ladies and the paranoiac, Lynch-riffing Address Unknown. Alan Wake sticks to a Twilight Zone-inspired anthology series called Night Springs. These TV shows are worth mentioning as a reminder that Remedy has never been shy about recognizing its influences. As such, Max Payne is a blend of Hong Kong cinema gunplay and conspiracy-laden noir. While Alan Wake is a Stephen King thriller filtered through the lens of Twin Peaks and The Twilight Zone. Both games are played straight—they intentionally lean into the campier side of their inspirations without ever attempting to mock them. The in-game televisions are a loving acknowledgement of the stories the developer enjoys and a clear signal to the audience that the story they’re watching is an intentional send-up of established genres.

In Quantum Break, Remedy’s most recent work, the player can guide protagonist Jack Joyce (portrayed by X-Men actor Shawn Ashmore) to a TV within the first few minutes of the game. Though the plot starts with Jack rushing to meet his brother for the demonstration of a revolutionary new technology, time can still be taken to stand around in front of a set and watch a video. The player expects more of these as the game goes on, but, instead, Remedy largely forgoes the constraints of these short videos for something bigger: live-action, full-length episodes of its very own science-fiction drama series.

multi-colored ribbons of exploded fireworks hang suspended in mid-air

Quantum Break is not so much a tribute to pulp sci-fi—it’s an embodiment. After his brother’s time machine malfunctions, Jack finds himself imbued with superpowers. His exposure to time-manipulating “chronon particles” gives Jack the ability to freeze the world around him, speed from place to place, and create pockets in space where nothing moves. The accident that gives Jack his powers also sets the end of the world into motion—a calamity dubbed The End of Time in which everything in existence simply stops. In attempting to avert this catastrophe, Jack is opposed by former friend Paul Serene (Game of Thrones’ Aidan Gillen), the founder of Monarch Solutions, a mega corporation with a vested interest in the shape the oncoming apocalypse will take.

That a brief summary of Quantum Break’s plot is necessarily convoluted should provide some idea of how the game itself unfolds. Just as Max Payne and Alan Wake couched themselves in crime and paranormal thriller conventions, Remedy’s latest owes a profound debt to the twisting plotlines and fantastic technology of the time travel genre.

Though initially off-putting, the game’s eagerness to explain the pseudo-science behind its various super devices, and the straight face with which it approaches the dramatic potential of time loops, becomes endearing. As Jack, the player spends much of her time shooting through groups of enemy soldiers across a series of competent, but unexceptional gun battles. It’s only in the handful of moments when the world freezes—time “stutters,” Jack able to move while everyone and everything else remains motionless—that Quantum Break exploits the design potential of its sci-fi conceits. There’s the impressive tableau of a party where multi-colored ribbons of exploded fireworks hang suspended in mid-air, and a scene where Jack attempts to escape a collapsing tanker, its steel guts having turned a great concrete dry dock into a several story-tall labyrinth. Otherwise, the game’s sense of character comes when control is wrested away for Quantum Break’s serialized TV show—four 20-minute episodes that run between the game’s playable acts.

In these episodes, a script that often falls flat in the rest of the game comes to life through fast-paced, ultra-corny scenes. Free of the technobabble that bogs down the computer-generated cinematics and fills the far too lengthy and frequent text logs, Quantum Break’s television segments are given no mandate but entertainment. The cast seems game for all of it and their performances—especially The Wire’s Lance Reddick’s portrayal of the dispassionately evil Martin Hatch—introduce a level of distinctly human enjoyment to the story, one that’s lacking from the exactingly detailed motion captures used in the rest of the game.

only the richest and best-connected may be able to survive

While the interactive core of Quantum Break is a serviceable ode to pulp science-fiction, the episodes are a reminder of what makes the genre enjoyable beyond metaphysical thought exercises: the ridiculousness. Much of this is the by-product of the glint in the cast’s eyes as they gnaw on Quantum Break’s glossary of terms (the “Lifeboat Protocol;” the “Chronon Field Regulator”). The rest comes from the low-rent charm of the episodes’ visuals. Take, for instance, the outfits worn by Monarch Solutions’ goons become cosplay writ large in live action, the same, sleek yellow-and-white design worn by the enemies in-game turning cartoonish next to actors in ordinary wardrobe.

This isn’t to suggest that the game is without substance. Remedy understands that, no matter how ridiculous its premise, proper genre fiction can use its immediate appeal as a Trojan horse for broader commentary. Quantum Break is eager to point out the ways in which the link between wealth and technology (especially in a corporate context) will become increasingly evident in the future. It makes a thriller out of the idea that, should super-advanced technology bring about a calamity, only the richest and best-connected may be able to survive the disasters they’ve caused. It isn’t much, but the connection between this message and our ongoing inability to implement government policies that mitigate the destruction of our natural world adds welcome depth.

Yet, despite the success it finds in both evoking and making good use of its genre trappings, Quantum Break is too uneven to fully capitalize on its strengths. Its TV episodes energize the plot only to see it grind to a halt with slabs of expository emails and notes. Its use of time manipulation creates fantastic visual effects and environmental navigation challenges in some sequences, before relegating them to power-ups meant to add flair to drab gun battles in others. In its previous work, the television sets that dotted Remedy’s games were extensions of already well-established tones. Quantum Break, in enlarging their length and complexity, turns them into a crutch that’s forced to support a game that can’t consistently match their appeal.

April 11, 2016

New study outlines gender inequality in movie dialogue

When film critics discuss the limited types of roles available to women, it can be tempting to try to debunk their arguments by listing counter-examples. “What about Ellen Ripley?” one might say. “What about Furiosa?” Unfortunately, a few well-written roles cannot make up for an overwhelming systemic disparity. The difficulty with this type of counter-argument is that it assumes an all-or-nothing mindset, as if feminists are claiming there are no positive roles for women at all. Rather, feminist critiques often focus on disproportionate lack of opportunity, something that becomes clear in Polygraph’s latest study of how dialogue is distributed among genders in movies, which seeks to back up these oftentimes anecdotal and theoretical arguments with cold, hard data.

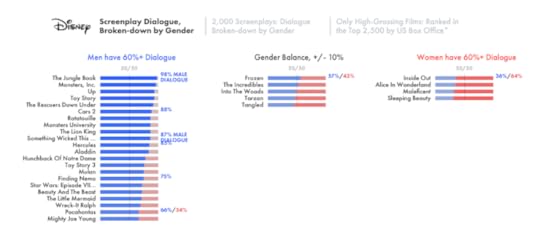

Culled from 2000 screenplays, the study maps movie dialogue across IMDB actor listings, creating a breakdown of which percentage of lines are spoken by men and which are spoken by women. The idea for the project was born out of the response to Polygraph’s previous study on the Bechdel Test, which simply requires films to have two named female characters who speak to each other about something other than a man, as the group hoped that looking at dialogue as a whole would allow them to address questions that the Bechdel Test does not. For instance, the study also breaks down dialogue by age, allowing readers to compare the differences male and female actors experience as they get older.

The results seem to support the feminist rhetoric

The results seem to support the feminist rhetoric Polygraph was seeking to interrogate, as out of 2000 films, only 321 had dialogue that was equally shared among men and women. Meanwhile, 1208 films had dialogue that was 60-90% male, 304 films had dialogue that was greater than 90% male, 165 films had dialogue that was 60-90% female, and only 8 films had dialogue that was greater than 90% female. Even films that are targeted at a female audience, such as Disney Princess movies and romantic comedies, had dialogue that was majority male. Meanwhile, the data reads that men tend to be offered more roles as they get older, whereas women are offered fewer.

That said, the researchers do recognize that their research methodology has room for error. For example, the study only takes into account characters with over 100 words of dialogue, meaning that films like Schindler’s List may be characterized as having entirely male dialogue, when they are in fact closer to having 99.5% male dialogue. Additionally, the study cannot take into account differences between a script and a final film, meaning that while Polygraph still stands behind the general direction of their study, individual films may have errors.

Still, Polygraph claims that the study is “arguably the largest undertaking of script analysis, ever,” and even if it’s “still not perfect…we’re now in a much better place than ‘you know…women are never love-interests when they’re older than 40. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯’”

Hyperactive shooter DESYNC is made to resemble synesthesia

Beginning in the 20th century, modern design started being dominated by the saying “form follows function.” The idea was that when creating a building, car, or piece of software, pragmatism should come first, and style should be secondary. In Adult Swim’s upcoming game DESYNC, however, style is the function.

Taking inspiration from classic shooters like Quake (1996) and Unreal Tournament (1999), DESYNC is a deliberately unrealistic shooter set in a colorful neon world resembling the computer reality of the Tron films. Enemies are abstract collections of polygons and vectors, and players dual-wield guns and swords while jumping dozens of feet into the air and sprinting faster than Usain Bolt. This is all set to a dope electronic soundtrack, and the result is a Daft Punk-inspired fever dream that looks like a scene kid’s Christmas list. Most interesting, however, is how the game hopes to utilize this sensory overload to teach its players how to shoot good.

“A linchpin of all of Desync‘s design is creating synesthesia,” write the game’s developers in a recent entry over on their devlog. “This is most clearly reflected in the art-style.” They explain that because Desync is built to support a wide number of playstyles, it has an “overabundance of mechanics.” However, with its simple, clean world, the developers hope to help introduce players to its complexity not through plain text or extended tutorials, but through “a-ha moments” discovered naturally during play. “Desync has been built upon the idea of supplying simplicity/minimalism inside a shell of complexity,” they explain. “We’ve wanted everything in Desync to be somewhat abstract, hidden behind a layer of understanding that can only come through interacting with and even caring about the game’s systems.”

“A linchpin of all of Desync‘s design is creating synesthesia”

For instance, attacks in the games aren’t described using full sentences, instead simply listing the guns, enemy types, and traps involved to give players a clue as to what to do. Then, when they puzzle out how to make the attack work, the hope is that it will stick with them better than if the game had simply told them outright. “We only begrudgingly use human language at all,” write the developers. “Had the game been simpler, we’d create an alien language of glyphs, animations and icons to describe actions in the game,” similar to the recently released Hyper Light Drifter.

The result is a game that harkens back to the ‘80s, not just in its kitschy retro-VR look, but in its insistence that players just figure it out. As games have moved into 3D and become more complicated, tutorials and extended text teaching players how to play the game have only become more prevalent. This can be seen in the boot camp sessions at the beginning of many Call of Duty games, or in how the opening hours of Zelda games tend to be spent in a closed-off safe zone getting accustomed to how to play. With a touch of style and a good push out of the nest, though, DESYNC argues that even with all their complexity, modern games aren’t that much harder to understand than racing a light cycle in an ‘80s arcade cabinet.

DeSync is scheduled to release sometime in 2016. You can keep up with its development over on its devlog.

Hacker combines one of the best Sonic games with arguably the worst one

For the uninitiated, there are two things that Sonic the Hedgehog loves above all else: running really fast and collecting rings. The latter is such an integral part of the anthropomorphic blue hedgehog’s life that without just one, by simply touching him, he’ll die. This love affair is the primary subject of a new take on the original Sonic the Hedgehog (1991).

Using a process called ROM hacking, allowing for the alteration of a game’s graphics, levels, musics and, in this case, dialogue, hacker Victor “VAdaPEGA” Araújo has combined Sonic the Hedgehog with the game Sonic Boom: Rise of Lyric (2014). The former of which is one of the most influential and famous videogames of all time, successfully cementing Sonic as a cultural icon. The latter of which is notorious for being extremely bad and one of the worst selling games in the series’ 25 year history. The amalgamation of the two, appropriately named Sonic the Hedgehog Boom (2016), is something of a vinegar-flavored cake.

Araújo told me he got involved with ROM hacking in 2010 as a way to pass time during school, creating a couple of “awful” Mario hacks. “When I moved onto the Sonic hacks,” he explained, “things got a lot easier since everything has in-depth documentation of how to change practically anything, practically anyone can take it and turn it into their own Sonic hack.”

The biggest addition to Sonic the Hedgehog in Araújo’s ROM hack is dialogue ripped straight from Rise of Lyric, largely about collecting rings. As Sonic runs through each level, he shouts quips such as “It’s like they’re drawn to me!” And “You can never have too many rings!” Which, for Sonic, is probably true. Uploaded by the YouTube channel Razor & Zenon, a channel dedicated to hacked Sonic games, Araújo’s video is a 30-minute walkthrough of the entirety of Sonic the Hedgehog Boom. It’s fairly humorous, and largely maddening, listening to Sonic talk about rings ad nauseam.

“It’s like they’re drawn to me!”

Araújo explained there is a large community around Sonic hacks. Two communities he frequents are Sonic Retro and Sonic Stuff Research Group. “There are projects in the community with really impressive achievements, so please check them out,” he said.

Never expecting his hacks to receive this much attention, Araújo doesn’t have a lot of his work easily accessible for any interested. But a few videos can be found at his personal YouTube channel, including more Sonic hacks, as well as hacks of games such as The Binding of Isaac (2011) and Mario 64 (1996).

An upcoming shooter doesn’t let you aim your guns

Seraph is a shooter in which you don’t aim. It’s set to hit Steam Early Access this month and PlayStation 4 at a later date. But if you don’t want to wait until then to find out how it works, here, it’s simple: it’s a 2D sidescrolling shooter that aims and fires your guns for you, leaving you to focus on skillfully dodging enemy attacks with increasingly flashy, acrobatic moves.

“The idea came from my love of the movies The Matrix (1999) and Equilibrium (2002). I wanted to deliver a gaming experience that truly delivered on how awesome these films looked and auto-aim seemed like a good way to achieve this.” Daniel Leaver, Seraph’s designer, told me.

cartwheeling through crowds like a court jester

Turns out that Seraph also doesn’t come short on the videogame influences either, with John Woo’s Stranglehold (2007), WET (2009), Max Payne (2001) and Devil May Cry (2001) all being cited by Leaver. He points out one major difference, though, and that is Seraph being played entirely in 2D. “This removes yet another barrier to a fun and accessible action game experience that 3D control schemes can often complicate,” he says.

Seraph also features a leveling system that ratchets up the difficulty as you play to ensure that you can jump right into the action, but will always be challenged by increasingly complex levels. Other RPG-borrowed elements typically found in modern action games such as a skill tree and upgrade system are also confirmed as features. They should help you tweak your character as you progress to better tailor them to your preferred approach to hostility: cartwheeling through crowds like a court jester or hanging back to make the most of your guns’ range. Levels are also procedurally generated ensuring you will have plenty of time to get your Quake (1996) sans mouse control fix.

On Seraph’s design mentality, Leaver said he was guided by the idea that it’s meant to be “as entertaining to watch as to play.” This manifests in the form of features built into the game specifically with Twitch streamers in mind. Viewers of Seraph streams will be able to vote on what level the streamer will play next as well as give them positive or negative bonuses leaving you to the mercy of the Twitch chat.

Seraph is coming to Steam Early Access later this month. You can find more info on its website.

Sam Hinkie, the man who failed to understand the game design of the NBA

True to form, Sam Hinkie was not wrong when he wrote “the NBA can be a league of desperation” in a letter to the Philadelphia 76ers’ equity partners last week. Hinkie, having quit his position with that letter, is now the former president and general manager of the 76ers. And more importantly, he made a career out of not being wrong.

Hinkie was not wrong in noting that the design of the league offered scant rewards for mediocrity; a team on the margins of the playoffs can easily become trapped in that unsatisfying range. Hinkie was not wrong to observe that the league consistently rewards its worst teams with high draft picks. Nor, for that matter, was he wrong in calculating that such picks are the most reliable way to acquire a transcendental player. Hinkie wasn’t even wrong in noting that there’s an arbitrage opportunity in taking on the stupid money contracts handed out by other teams.

There is, however, a crucial difference between not being wrong and actually being right. That is as good a place as any to start analyzing the legacy of Sam Hinkie and what came to be known as The Process, a three-year reign of terror during which the 76ers won a league worst 19.4 per cent of their games. (Over the same period the next-worst team, the Los Angeles Lakers, won 26.6 per cent of their games.)

So why didn’t The Process work? It didn’t help that Hinkie turned his collection of draft picks into a series of tall men who were broken to varying degrees or, in the case of Dario Saric, yet to enter the country. It also didn’t help that the 76ers were unable to convert their futility into a number one draft pick. But those setbacks were just the cherries on the fetid sundae that was The Process; Sam Hinkie’s real problem was a failure to understand the game design of the NBA.

When he wrote about The Process in late 2014, Kill Screen supremo Jamin Warren (who, full disclosure, pays my bills) likened it to the strategy employed by Chinese, South Korean, and Indonesian badminton players at the 2012 Olympics, all of whom calculated that throwing games would place them on the easier side of the draw. In hindsight, the salient part of this parallel is that these teams were thrown out of the tournament. Sports leagues, it turns out, have a limited tolerance for deliberate losing as a strategy. In soccer, the Premier League has previously fined teams for fielding supposedly noncompetitive squads. In the NBA, the Stepien Rule prevents teams from trading first round picks in consecutive years. It is named for former Cleveland Cavaliers owner Ted Stepien, a man who by almost all accounts needed to be saved from himself. The rule, however, is a signal that not all strategies are actually on the table when it comes to sports leagues. Indeed, NBA commissioner Adam Silver tried (and failed) to pass reforms last year that would have ruled out many of Hinkie’s shenanigans.

a failure to understand the game design of the NBA

Hinkie did not, however, escape the long arm of the league. Longtime NBA executive Jerry Colangelo was appointed as his superior in December. “Multiple sources said the league office helped bring the pairing of [Sixers owner Josh] Harris and Colangelo together in Philadelphia,” The Washington Post reported at the time. The story continued: “If there was any possibility that this long-term experiment of tanking for picks could continue past this season, those thoughts ended Monday.” Colangelo’s son, Bryan, will now replace Hinkie in Philadelphia.

What made Hinkie think that he could avoid the fates of Stepien or the Olympic badminton players? The Process, above all else, was a calculated bet that the public and league would both accept that not all forms of losing are created equal. Ted Stepien may have been an idiot, sure, but Sam Hinkie, the theory went, was a genius. To an extent, it worked. A fair number—though definitely not all—fans bought into The Process. The hashtag #INHINKIEWETRUST became a genuine expression of faith and a site of vicious satire. The Process was many things—a theory of how basketball works, a strategy—but it was primarily a rhetorical strategy to make Hinkie seem different from Stepien or the Olympic badminton players.

That is why Hinkie, on the rare occasions he expressed himself, sounded like an airport bookstore who had achieved sentience and been placed in charge of a basketball franchise. The 13-page letter announcing his resignation/ouster did little to dispel this operation. Amid a flurry of LSAT words and some others that may not actually be words, Hinkie managed to cite prominent thinkfluencers such as Atul Gawande, Elon Musk, and Warren Buffet. The general thesis of the piece, insofar as it has one, is that old Apple slogan: Think Different. As with that other, more modern tech mantra, disruptive innovation (also cited in the Hinkie letter), Think Different is one of those aphorisms that hardly guarantees success yet is difficult to refute. How can you be sure that disruption isn’t actually working? How can you be sure The Process wasn’t going to work? In most cases, these things don’t work, but the logical formulation makes it harder to call the speaker’s bluff.

Hinkie ran the Sixers like a man who took Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,00-hour rule more literally than the man who came up with it. If these players could just face enough adversity, if they could just get in their 10,000 hours, maybe, just maybe… It is here that one ought pause to note that Gladwell’s favorite basketball figure, Vivek Ranadivé, currently presides over a Sacramento Kings team that only rivals the Sixers in its dysfunction. The thing about these pop-psychology and management theory ideas that Hinkie never seemed to understand is that they were still probabilistic. Most disruption is just disruption. Most people, even given 10,000 hours, will still not be good basketball players. There are things you can do to improve your odds, but The Process’ ontological conclusion turned probabilistic thinking into an article of faith.

this… is what basketball must look like to him

Here’s what I know about Sam Hinkie, the former Stanford MBA, management consultant, and Sixers GM: His team was unrelentingly awful. He wouldn’t really dispute this point. Maybe they’ll get better at some point in the future—and maybe Hinkie will deserve some credit for that—but the last three years have been very, very bad.

Here’s what else I know: There’s a game called Soccer Manager that I’ve been playing for the better part of six years now. You play as the front office of a soccer team, buying and selling players. Through a quirk of game design, Soccer Manager offers some easy opportunities for arbitrage. You can buy players at their minimum asking price and, so long as they don’t get worse, you are guaranteed a profit in a few months when you resell them. In that respect, you can collect players like assets and move them around until you are eventually wealthy and your team is stocked with good players. You never actually play the game of soccer in Soccer Manager; you just log in at 4:30 p.m. and check your scores. It’s an abstracted vision of sport, in which players are just assets and success depends on seeing little more than numbers on a spreadsheet. When logging in over the past few years, I’ve occasionally found myself thinking of Sam Hinkie. This, I’ve thought, is what basketball must look like to him. He was not wrong about many of the sport’s underlying structures, but he was not right about the latitude it allows managers or the human element that cannot be simulated away.

Another perfect marriage of cyberpunk and pixels

Cyberpunk worlds always seem to draw me in. Whether it’s the derelict planets visited by Spike Spiegel and his bounty hunting companions in the cult classic anime Cowboy Bebop (1997-98), or the replicant-laden world of the famed Blade Runner (1982), cyberpunk has always remained a static aesthetic in the media I’ve read, watched, and played. And freelance pixel artist Matt Frith’s bite-sized cyberpunk point-and-click adventure game Among Thorns is no exception.

The setting in Among Thorns is described on as “a world suffering with a technological plague, Cora Bry is recruited for a shady job.” So, essentially, a textbook example of any cyberpunk narrative. There’s the gloomy and rainy neon-accented city, and the stoic, brooding anti-hero. In the game, the player manages an inventory and talks to artificial characters, all animated in Frith’s distinct and stylish pixel art. Among Thorns is only the latest in a recent renaissance of the point-and-click adventure genre, specifically of the perpetually-cool cyberpunk variety.

The marriage of pixel art and cyberpunk has never felt out of place

The cyberpunk adventure genre was in part spearheaded by none other than Hideo Kojima (of Metal Gear Solid fame) with his early game Snatcher (1988)—it should come as no surprise that it’s a closely-leaning “homage” to Blade Runner. In more recent times, the pixel-y cyberpunk adventure genre has resurged. The Neo-San Francisco set Read Only Memories (2015) was a similar step into the cyberpunk adventure field as Among Thorns’ has done in its brief venture. Yet Read Only Memories wasn’t a lone wolf in the resurgence of the genre, because of a slew of upcoming releases, including Odd Tales’ hauntingly beautiful pixel platformer The Last Night. Joining The Last Night in cyberpunk goodness is the upcoming VA-11 HALL-A, which promises less of the adventuring bits, but replaces it with “bartending action,” and exists within a similar realm of neon-tinged, post-dystopian life.

The marriage of pixel art and cyberpunk has never felt out of place. Especially in modern times, where pixels are a stylistic relic of gaming’s past. In a similar sense with cyberpunk, architecture is often reminiscent of the grimiest of today’s cities, usually with a futuristic perk. Both pixel art and cyberpunk present throwbacks to the past in a bleak, yet noteworthy way. Frith’s marriage of cyberpunk and his well-regarded pixel art in Among Thorns is no exception.

Experience the technological plague in Among Thorns on itch.io here, and if you donate, there’s a higher chance for Frith to create a potential sequel – one that’s even longer.

Failure and rebirth in Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter

Star Trek’s cavalcade of hit-or-miss conceits includes a fair share of philosophical thought experiments, and chief among them is the “Kobayashi Maru.” This name refers to a wargame for Star Fleet military cadets used to evaluate how officers-in-training would react in an impossible-to-win scenario. The crew being examined receives a distress call from a fellow ship called the Kobayashi Maru, a wounded bird floating defenseless in the void, and upon reaching it two Klingon vessels emerge and attack. The captain must decide whether to leave the Kobayashi Maru to certain destruction or engage the firing ships, though the cadets are outmatched and guaranteed to be disintegrated as well. This situation is meant to appraise a leader’s character under the pressure of a battle that cannot be won.

Such a test can be a useful measure of one’s capacity for confronting overwhelming difficulty, but requisite failure doesn’t push videogame units. Which is why the Kobayashi Maru is an apt analogy for Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter (2002), an early Japanese role-playing game in the PlayStation 2’s lifespan, and the fifth Breath of Fire game overall. At release it was critically acclaimed, but proved to be so off-brand in almost every way that it was left to rot on the shelves by the public.

Dragon Quarter’s connections to the Breath of Fire universe and JRPG conventions are thin, but fibrous. Mostly, it hews away the built-up layers of what JPRGs were thought to be after more than a decade of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and many others. By the time Dragon Quarter came out, its peers were were more expansive than ever, encompassing entire planets with casts of playable characters that dwarf the average NFL player roster. They were proto-visual novels, broken up between cutscenes and grinding, which is essentially an in-game, unedited training montage played at half-speed, and that ultimately has no effect on the immediate apocalypse threatening the world. Dragon Quarter is skeletal by comparison, but the bones are robust, a titanium frame for the player to experience the narrative tension rather than merely spectating. This is accomplished by making encounters finite, with monsters always visible while you wander the map, susceptible to pre-fight traps and bait.

But each skirmish also presents a potential catastrophe that puts the player’s progress and invested time at stake. The meat of most JRPGs is the non-fatal random battles that task the player to puzzle out monster weaknesses and overall strategy; more akin to a series of hunts rather than regularly scheduled desperate struggles with survival constantly at stake. Dragon Quarter inverts this relationship, and while it isn’t quite impossible, it’s a nearly nonstop parade of grueling situations, acting as it were the definition of going two steps forward and one step back. By spotlighting what is usually a sideline slog meant for increasing stats and by having fixed enemy encounters, Dragon Quarter doubles down on the grind while stripping out its usual ancillary nature: a requisite trudge of rewarding toil, but with the delectable thrill of possible oblivion at every step.

This isn’t an empty narrative scare; Dragon Quarter really does want Ryu to fail

The main character is a grunt usually referred to as Ryu in an underground future-fantasy dystopia, whose best friend Bosch is swiftly revealed to be a sociopathic power-monger. Bosch can’t handle the competition after Ryu is possessed by a dragon spirit (another of the few links to the Breath of Fire series), blessed with incredible in-game power but cursed to die if that power is overused, as the constantly rising D-Counter reminds you. Ryu finds a young woman named Nina, genetically engineered as a living air filter who is doomed by this polluted underworld, who he vows to lead above ground. Society has crumbled, the environment is all but consumed, and Ryu is told constantly that he is without value and destined to flounder. This isn’t an empty narrative scare; Dragon Quarter really does want Ryu to fail. The player comes to understand this all too well due to the game only having one save slot, and only the occasional opportunity to save in that slot. While harsh, this restriction is an important part of the intended game experience. There is a kind of mid-game restart system that lets some stats and items be carried over into a new run. Doing so gives you a bit of an edge, and also unlocks extra cutscenes to further flesh out a compellingly honed narrative built on stylized cel-shaded visuals and tautly composed music. The sound design also respects and elegantly utilizes silence, all to reinforce the theme of karmic reincarnation. All this is to say that Dragon Quarter wants you to restart its journey halfway through. And so you are set-up to die and be reborn, it is practically required in this game. How you manage this inevitable collapse makes Dragon Quarter the Kobayashi Maru of JRPGs.

By removing the safety net of unlimited saves and transforming the “grind” from a necessary evil into a ludological metaphor for the player’s uphill battle to the surface, Dragon Quarter puts the player in the same viscerally anxious emotional state as the characters. You cannot over prepare. Battles are a calculated risk but to avoid fights only puts you out of practice for the inevitable bosses. Items are somewhat abundant, while your capacity to carry them is initially very limited. The game does away with almost all distractions: no stat trees or extensive weapon modifications or crafting; your party is only composed of three members (except for the first dungeon, spent with your frenemy Bosch); there’s pretty much only one narrative side mission, and an optional ant-themed mini-game at least provides some useful equipment when towns are few and far between. The strategy of most JRPGs up to this point consisted of fighting monsters to gain levels until your team’s statistics were larger than those you had to defeat. Sure, you often had to figure out which attacks to use against certain enemies, as if playing a variation of rock-paper-scissors, but once that’s done it was a case of rinse and repeat. Those facets remain in Dragon Quarter, but are boiled down to a rich broth that only leaves the tastiest flavors simmering.

Recently, Dark Souls (2011) instructed its players with brutal opacity and was commercially and critically lauded for it; its tagline might as well have been “die, die again, die better.” Others, like The Last of Us (2013), craft delicate experiences through the anxiety of dystopian near-futures. But even these games allow for quick restarts so that the player can succeed without a methodical approach to groups of enemies, instead of instantly re-plowing the beats of a stage a until a flow is established—it favors memorizing a pathway over developing the ability to navigate the pressures of a ticking clock and superior foes. More than 10 years ago, Dragon Quarter helped lay the foundation for enjoyable brutality, a spiritual predecessor requiring equal measures of patience and persistence.

Only Captain James T. Kirk has “won” the Kobayashi Maru simulation: by reprogramming the test, as he deemed it unfair and doesn’t believe in a no-win situation. You can cop Kirk’s moves in Dragon Quarter through emulation and save states. Doing so really does deflate the stakes of the game’s imposed stress, like walking a tightrope two inches off the ground: challenging but devoid of adrenaline. To really savor the Dragon Quarter experience, you must confront fallibility and smother up to the cold cuddle of oblivion.

April 9, 2016

Weekend Reading: Bring Me The Head of Rose Quartz

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

The Propaganda of Pantone: Colour and Subcultural Sublimation, LOKI

Color-matching company Pantone announced that the colors of 2016 are “Rose Quartz” and “Serenity,” hues you’ve likely encountered in recent history if you spend any considerable amount of time online or in a city. But the influence of Pantone and their declaration of the year’s colors shouldn’t overshadow the countercultures and ideologies that revived them in the first place. LOKI’s blog gives a breakdown of what Pantone is absorbing into their brand.

Violence Is A Very Sad Poetry: The Films Of Sam Peckinpah, Justine Smith, Roger Ebert

Wild Bunch (1969) and Straw Dogs (1971) director Sam Peckinpah made many a film, and many a violent one at that. But Peckinpah didn’t use violence for titillation, shock, and gruesomeness, as Justine Smith explores in her examination of the troubled worlds portrayed in Peckinpah’s work.

Photograph by Frédéric Noy

Photograph by Frédéric NoySmall But Supa Tough, David Bertrand, Hazlitt

Some of the wildest, craziest action films aren’t coming out of America, Japan, or Hong Kong, but Uganda, where Wakaliwood pumps out one breakneck thrillride after another on non-budgets and chugging hardware. David Bertrand explores the film scene born out of the blood of political turmoil and Rambo tapes, and how Uganda goes to the cinema.

The End of Firewatch, Duncan Fyfe, The Campo Santo Quarterly Review

While it won’t be the final word on Firewatch, its creators over at Campo Santo have something to say about the final words in the game. Elaborating on the intent of Henry’s hardest summer, and the frustration some players experienced with the climax, Duncan Fyfe explains how the greatest drama can occur off-screen.

///

Header image: Night Out, Lora Mathis

April 8, 2016

Using Twine games to preserve modern folk stories

Teviot Tales is a game that shares the stories of residents living in the Teviot Estate in Poplar, London. Developer and writer Hannah Nicklin spent six months at the estate, exploring the nearby area and conducting interviews with locals. Alongside the poetry and game design workshops she ran during her time there, she also held one for storytelling, where she invited and encouraged people to tell whatever stories they wished to tell.

There’s Terry, who speaks of his time spent with his best friend John back when he was 12-years old, as they smoked Weights and listened to Temperance Seven records; Margaret, who always puts her bag on the seat next to her while riding on the DLR so she can imagine her husband sitting with her; and also Anisha and Aklima, who reminisce about their friend who passed away the previous summer.

what a modern, multicultural version of that tradition might be

Nicklin believes Teviot Tales represents the beginnings of a new way in which games—and the tools used to make them—can not only help to share unique stories about our lives, but to also engage others in order to get a new and different perspective on how they live. “We used to talk about ourselves in folk songs and story, and I like to try and work with people to think about what a modern, multicultural version of that tradition might be—how we connect with others, to think about who we are, and who we might be, together,” she said.

Twine, and the resulting ‘Twine games’—such as Teviot Tales—continue to be wildly popular due to the many diverse subjects creators decide to tackle. The open-source tool allows just about anyone to make an interactive, dialogue-heavy game, provided they have the desire to do so. If you have a story you want to tell, it’s quite possible you can make and share it with the world thanks to Twine.

Teviot Tales is set to release on PoplarPeople on May 2, 2016. Prior to its release, on April 29th and 30th, there will be a free two day opening exhibition for the game at The Teviot Centre in Poplar, London. Attendees will be able to play the game early, as well as see some of the writing, game design and stories that were produced during the various workshops.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers