Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 136

April 13, 2016

The optimistic cityscapes and “ragdoll flail” of FutureGrind

The in-development motorcycle-grinding game FutureGrind is a lot like the classic NES game Uniracers (1994), except that its lone-wheeling ways is perhaps the only similarity that ties the two together. FutureGrind can be more favorably compared to its extreme sports game influences, such as the kickflipping gems Skate (2007) and OlliOlli (2014), to the intense snowboarding action of SSX 3 (2003).

A stunt-platformer at heart, FutureGrind is summed up as a futuristic motorcycle grinding game—similar on the surface to the also motorcycle-focused Trials series. Yet in FutureGrind, players seek to land as many tricks on a track as humanly possible, all while bouncing vertically from color-coded rail to rail. And, trying not to explode while doing so. At the Game Developer’s Conference in March 2016, we caught up with the two-man development team of Matt Rix and Owen Goss to get an inside look at FutureGrind.

The past year in development for FutureGrind, since its announcement in early 2015, has been one full of fine-tuning and aesthetic adjustments. In the game’s first trailer, Goss noted that the rider was static, just mesh; the rider had no weight. In its latest stretch of development, more “ragdoll flail” has been implemented (as all great Trials-y games have). “We spent a lot of time trying to breath life into this character,” said Goss. “So as the bike moves, the rider shifts their weight forward and back as the bike rocks. And as they land, they slam down into the seat. When the crash happens, we turn them into full ragdoll physics objects that tumble.” Giving the rider heightened physics makes them feel more alive than ever before. It can also make for moments of supreme slapstick comedy.

FutureGrind itself is a skill-based game: easy to pick-up, but hard to master. “We tried to create a game that’s very deep in terms of dynamics of learning to play and mastering the optimal paths through the levels,” said Goss. “At its heart the game is very much about rhythm and flow, and what we want the player to feel is when you pull off what you’re trying to do in this game [that] it feels very, very good.” The game’s music, composed by musician and game designer bignic, takes its German electronic inspiration wholeheartedly, with melody-less, pulsing beats soundtracking the experience. The repetition of the music ties into the way the game plays: it’s rhythmic, like the rider’s endless grind-trials itself.

In FutureGrind’s future, literally anything is possible

The vertical-leaning motorcycle physics were inspired by an aforementioned motorcycle series, one that’s prone to exploits and glitches of the hanging variety. “A core idea of the game is [to] make something where hanging and swinging from objects is really important to how it feels, and something where getting a high score should look cool,” said Rix. “There shouldn’t be a way where you can do glitchy weird stuff to get a high score, it should be something that has a very smooth flow to it, that feels really good to do, and [is] entertaining to watch.”

Rix and Goss plan to have six unique environments in the final game, with multiple tracks per environment. As the player progresses through the game, they unlock new abilities, and will be able to revisit old tracks and play them in an entirely new way. “We want it to feel fresh the whole time, basically,” said Rix. The environments themselves all show new sights of FutureGrind’s ever-positive future, with shimmering beaches and pristine cityscapes, to even a mountain-filled area. The mountain level in particular is inspired by Goss’ time living in Vancouver. “I used to go up to Whistler to ski a lot and I loved that feeling of being in the mountains,” said Goss. “The mountain level is very much inspired by the photographs I had taken while I was skiing.”

FutureGrind features a bright and colorful world, laden with windmills and glossy cities (which are inspired by the parkour action game Mirror’s Edge (2008), as it turns out), all hoping to account contribute to the game’s subtle, environmental storytelling—a world that feels alive and lived in. “When we were coming up with the game, there were so many dystopian future things, and we wanted something that was more positive,” said Rix. “It’s very much like an optimistic future.” In FutureGrind’s future, literally anything is possible. Even gravity-defying motorcycle grinding.

Reporting contributed by Jess Joho.

For more on FutureGrind and its development, check out Milkbag Games’ site here . FutureGrind is due for release sometime in late Summer/early Fall for PS4, PC, and Mac.

Look out for Solace State, a game about ideological division in a daunting sci-fi city

The world of Solace State opens up before me, its buildings cross-cut and becoming transparent as Chloe, a “woman of many [identities] who gets caught up in a journey of dissent, deception and redemption” navigates a foreign, 21st century cosmopolitan city-state. “An isometric camera cuts in, and you’re hacking into the building,” says Tanya Kan, the lead designer and founder of Vivid Foundry as she demonstrates Solace State for me. “It’s a way of depicting open-societies, or of trying to reveal more of the world.” As 2D art is overlaid on 3D environments, I’m reminded of origami: detailed, delicate, intricate. Compartmentalized facets combining to form structures, just as conversations can combine to inform identities and cultures.

Solace State takes the form of a 3D visual novel. In it, characters traverse physical, political, and ideological divisions to reach one another as all around them a population bristles under the thumb of a surveillance state. The game is interactive by way of infrequent dialogue trees, but the predominant mechanism of the game is listening. Chloe gains trust by listening to other characters’ stories and observing foreign urban spaces and cultures as they transform from the unfamiliar to the familiar. It’s in this that Solace State is evocative of Christine Love’s “Love Conquers All“ games, or Peter Brinson and Kurosh ValaNejad’s The Cat and the Coup (2011). These games sit at the intersection of identity politics, power, and technology, to explore real-world relationships and events.

I caught up with Kan as she was returning from a talk about Solace State and the politics of affect at the Different Games Conference in Brooklyn. “The idea is that you affect others and others affect you consistently and continuously,” she said about Solace State. “There’s not one root cause of events, as is in contrast with, for example, Marxism and its modes of production. It’s much more indeterminable. What this means is that politics [are] very open and political change is bound to happen.”

“The concerns of poverty and of the shrinking middle class echoes across generations”

Solace State creates both the conditions for a dialogue about post-colonialism, and provides an example of that dialogue in action. Its characters represent a polyglot against a backdrop of an encroaching surveillance state. The aesthetic is futuristic in a way that invites comparison to Blade Runner (1982), taking place in the near future in a fictional city-state called Abraxa Harbour, where an elite live far above the worker class. And yet the themes of privacy, security, economic inequality, and technological empowerment should feel hauntingly familiar, timely, almost urgent to anyone who occasionally browses the news. Across cultures these stories are increasingly universal. “The concerns of poverty and of the shrinking middle class echoes across generations,” says Kan. “That’s why the story takes place in an imaginary city, so that people can’t say “this is only about Asia. It’s happening everywhere.”

If this sounds like heady content, it’s because it can be. In the course of our discussion, Kan references “Rebel Girls: Youth Activism and Social Change Across the Americas” by Jessica Taft, Deleuze’s rhizome, Foucault’s panopticon, Baudrillard’s hypermodernity, as well as a play by Bernard Shaw and the films of Wong Kar-wai. The theoretical framework informing Solace State’s development is, in a word, robust, and the game sits at the confluence of aesthetics, dialogues, states of being and political positions. But Kan insists the player doesn’t need to be versed in post-structural or post-colonial theory.

“It’s very accessible. If you like the theory, you’ll be able to sense it, but if you’re a person who likes to read the news you’ll enjoy the game,” Kan says. “I like having this reflect the norms of our time, and so it’s open-ended. I hope that people come away from this as a self-reflexive piece and that it starts a discussion.”

Solace State is currently in the making for PC. You can read more about it on its website.

1979 Revolution is a history lesson for the Netflix generation

As a school-aged kid in the 1990s, I didn’t spend a lot of class time talking about Iran. The name Ayatollah Khomeini meant more to me as a reference to a joke from The Simpsons than as an actual historical figure. As an adult, I became marginally more aware of Iran’s contemporary position within Middle East quagmires and U.S. international tensions, but my understanding of its recent history grew no more sophisticated. So when I sat down to play 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, I felt both curious and ignorant of the world I was entering. And, to developer iNK Stories’ significant credit, by the end of this first episode’s two-hour run, I had learned some things.

Educational games can get a bad rap—or, at least, they can be viewed as qualitatively different from (read: lamer than) games with no specific educational agenda. 1979 Revolution defies this arbitrary divide by creating an experience that is a near-equal blend of historical thriller and interactive exhibit of the 1979 Iranian revolution. The former aspect, which leans heavily on the formula laid out by Telltale Games over the past four years, is full of hits and misses that at times provide exciting and emotional storytelling, and at other times make for a confusing or contrived player experience. The educational portion, however, is a major success: a reminder of how closely this virtual world is grounded in historical fact, but also of how difficult it is to divine the “true” story when you’re in the middle of it.

You play as Reza Shirazi, a young Iranian expat who has returned to his native country to find loyalist and revolutionary tensions rising to a fever pitch. The game’s 19 chapters play out in a framed structure, beginning sometime in the future as you reluctantly describe your role in the revolution to a prison interrogator, before jumping back to 1978 when you were an aspiring but apolitical photojournalist. Several chapters involve you, guided by your best (but socioeconomically “inferior”) friend Babak, walking through the streets of Tehran and snapping photos of what is transpiring as the country moves closer and closer to the brink. As you take pictures, the game pauses to show how your versions matches up to actual black-and-white photos from that time, as well as provide some brief context for whatever you captured. This ranges from the meaning of certain graffiti, to explaining why citizens of an oil-rich country couldn’t afford gasoline for themselves, to highlighting staples of Iranian cuisine.

By centering on Reza, who has been studying abroad at the start of the game’s timeline, the developers cleverly anticipate a player like me who has little context for what was happening in Iran in the late 1970s. Through his photos and conversations, Reza tries to parse out the peaceful revolutionaries from those who advocate violent rebellion—sorting the atheistic communists from the Islamic clerics, and the loyalists who genuinely believe in the Shah’s rule from those who only follow orders so that they can feed their families. The snippets of historical facts that the game provides are both genuinely educational but also tantalizing in their brevity, reinforcing the notion in the midst of political upheaval, judgments and actions often must be made based on limited information.

The back-and-forth between learning about the situation as an “outsider” and then having to make agentic decisions about, say, whether or not to throw rocks at armed police who have come to break up a peaceful protest, can be thrilling and scary. The consequences of your choices carry weight based not only on their place within the game’s story, but also due to your awareness that these scenarios are rooted in history.

In the midst of political upheaval, judgments and actions often must be made based on limited information

This dynamic would be have been enough to lead you through the game’s brief and fast-paced runtime, but unfortunately the developers also incorporated other gameplay aspects that add little to the experience. Quick time sequences in which you have to press arrow keys to avoid tripping on objects or bumping into people feel contrived and unnecessary: these sequences, while almost always a little obnoxious, can nevertheless feel important in a title like Telltale’s The Walking Dead (2012), in which they ratchet up the sense of urgency in the wake of a sudden zombie attack. But 1979 Revolution needs no such reminder. The tension already feels real enough without needing to force you to click the mouse really fast from time to time.

The other overused gimmick this game borrows from Telltale’s repertoire is the onscreen proclamations of “so-and-so will remember that” following an action or dialogue choice. This technique was employed brilliantly in titles like The Walking Dead and The Wolf Among Us (2013-14) in order to bring a sense of portentousness to moments that might otherwise seem mundane or inconsequential, forever keeping the player on her toes about the meaningfulness of her decisions. But when a revolutionary leader grabs my shirt and compels me to finger one of his lieutenants as a mole after only giving me a few minutes to question them, I don’t need a text bubble to tell me that he “won’t forget” my choice. If anything, this detracts from the realness of the situation: the implicit understanding that, in the heat of the moment and based on limited intel, I am sentencing someone to death.

Despite the kinks, some of which may be ironed out in future installments, 1979 Revolution represents an unusual and largely successful mix of an adventure game and history lesson. The acting and direction is impressive across the board, employing fast cinematic cuts and overlapping dialogue to further simulate a world that is moving fast—too fast, perhaps, for a thoughtful, partially-informed person like Reza (and you, the player) to fully appreciate what he is doing before he has to do it. In this way, 1979 Revolution is not just about what happened but how it happened, and how history in general happens: through snap judgments, emotional reactions, weighing the lesser of two evils, stacking personal ideals against the safety of family and friends. Revolution is a messy business.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

April 12, 2016

Did Rust just become the first transgender MMO?

Unlike many other online multiplayer games, Rust doesn’t give players any control over what their character looks like. Instead, it randomly generates a set of features and ties them permanently to the player’s Steam account. This means that, even if they leave the game, their character will look the same when they return. It’s a fitting choice, given how primal the world of the survival-based Rust is. Just as in real life, Rust doesn’t let you choose what you want to look like, but instead spits you out naked into its world with a body you had no say in, and tells you to deal with it.

Unfortunately, when the game originally released, characters were limited to white men. In an update released in March of 2015, though, the game sought to widen its diversity by adding unique skin tones and facial features to its character randomizer. Now a more recent update has added women to the game as well, meaning that some male players may have to come to grips with playing as a gender that does not match their own, something women had already been dealing with since launch.

The response to the new update has been divisive, similar to the backlash the game experienced when it introduced multiple races last year. Back then, certain white players took to Steam reviews and social media to show dissatisfaction with suddenly having to play as black or Asian characters without choice. However, players of color at the time noted that not just Rust, but hundreds of games had been forcing them to play as white characters for years. “There’s an interesting bit of comeuppance there in getting players who are white to sort of experience what it’s like for everyone else who doesn’t get to choose,” said Kill Screen founder Jamin Warren in an episode of PBS Game/Show. “I think it’s an awesome experiment and I hope they continue with it.”

Continue with it, they have. Now that the game has added women as well, the developers have taken to their devlog to explain their reasoning behind the update. “We understand that you may now be a gender that you don’t identify with in real-life,” writes Rust developer Craig Pearson. “We understand this causes you distress and makes you not want to play the game anymore.” However, he then counters this by noting that this was the situation female players were already contending with. “Technically nothing has changed, since half the population was already living with those feelings. The only difference is that whether you feel like this is now decided by your SteamID instead of your real life gender.”

“No wiggle room…You are who you are.”

When Eurogamer asked Rust‘s lead developer Garry Newman if there would be any wiggle room for periodically changing a character after assignment, he responded by saying “No wiggle room…You are who you are.” Again, this is in line with Rust’s existing “life is unfair, deal with it” aesthetic. It also helps draw attention to how often women must settle for playing male characters, even in games that pride themselves on openness, such as The Witcher 3 (2015)—in which you’re a man for the majority of the game—and The Legend of Zelda series. If male players become upset that they now must play as women, that seemingly only strengthens the argument for more female protagonists in games as a whole.

For me, as a transgender woman, however, the addition of gender to the game—and how it is assigned—represents something else entirely. Like Rust players who are uncomfortable playing as a character who does not match their real-life gender identity, I spent the first 20 years of my life feeling extreme discomfort over the gender I was assigned at birth. Despite my urging that I was not a man, I was forced to live outwardly as such, complete with all the social expectations that come with doing so, until I was finally able to go to college and begin hormone therapy without needing permission. There was no bargaining with my family, and my teen years felt like they would never end as I woke up every morning increasingly disgusted with myself and helpless to slow my puberty.

Ironically enough, one of the only comforts I had at the time was within games that let me play as a woman. It wasn’t much, but by playing female characters in online multiplayer games like Star Wars: Galaxies (2003) and World of Warcraft (2005), I was able to explore my burgeoning trans identity in a safe environment. In other words, when my life inside the real world was hell, I turned to virtual worlds to offer me some small amount of comfort. Conversely, Rust is now asking those that find the real world comfortable to experience a virtual world that is not. In forcing some players into a gender that may not match their actual gender identity, Rust may be the first MMO to allow its cisgender players to understand some small portion of what it might be like to be transgender.

Smart devices still struggle to cope with mental health crises

Content warning: This article discusses suicide and depression.

///

Most days can be good days, even when you’re diagnosed with depression and anxiety. Or at least they can be made to look as such. You learn to put on a good face, to make it through the day. All of this means that when you spiral—and you will inevitably spiral—it’s harder to reach out for help. So much of your effort is devoted to convincing people that you’re okay, to putting on a good face, that it’s hard to say things are going wrong. So, when you spiral, you are likely to be alone. In 2016, that really means you’ll be alone with your devices.

Your devices, perhaps moreso than your fellow human beings, are woefully ill equipped for this eventuality. Consider, for instance, IP mapping technology, which is used to divine the physical location of a device. As Kashmir Hill reports at Fusion, MaxMind, a widely used tool to map IP addresses simply defaults 600 million addresses it can’t locate to a farm in the middle of America. “If any of those IP addresses are used by a scammer, or a computer thief, or a suicidal person contacting a help line,” Hill writes, “MaxMind’s database places them at the same spot: 38.0000,-97.0000.”

“missed opportunities to leverage technology”

This is a problem for lots of people. If you are indeed a suicidal person calling for help, help may struggle to come your way. Conversely, if you happen to be a member of the Taylor family, which lives at MaxMind’s default location, you spend much of your life fending off emergency vehicles that think a suicidal person lives in your home. “Our deputies have been told this is an ongoing issue and the people who live there are nice, non-suicidal people,” local sheriff Kelly Herzet told Hill.

Many times, however, a person tells their device how they feel and no help is sent their way—even to the incorrect coordinates. Apple responded to suicide prevention advocates in 2012 by programming its personal assistant Siri to respond to a person declaring that they were suicidal:

In March, however, Pacific Standard reported on more recent studies of how personal assistants respond to such scenarios. Samsung’s “S Voice”, the article’s author noted, only spit out “Life is too precious. Don’t even think about hurting yourself” when told that the user wanted to commit suicide. No further information was provided. This was perhaps the most glaring failure, but it was far from the only one. In an article from the journal JAMA Internal Medicine cited by Pacific Standard, the researchers concluded, “Our findings indicate missed opportunities to leverage technology to improve referrals to health care services.”

This is not an entirely new problem. In 2010, Google started adding a suggestion for the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at the top of searches for “ways to commit suicide” and “suicidal thoughts.” There are, however, plenty of search terms that don’t trigger any warnings. In fact, as I found out last night, a search for “how to hang yourself” not only failed to trigger a warning, it also featured an 8-point list of painless ways to die excerpted from another site like a recipe. You didn’t even need to click a link to find what you were looking for. To be fair, Google cannot be expected to foresee all searches a suicidal person might make—“how to hang yourself” may be obvious enough, but do you also include a warning on autoerotic asphyxiation or breathplay?—but the inconsistency of its policy speaks to the challenges technology companies come up against when dealing with suicide. The problems AIs and personal assistants now face are only larger versions of those that search engines have been reckoning with since the start of the decade.

We express our issues obliquely and to inanimate objects

The phone as an end unto itself in suicide prevention strategy is a recent development. Until recently, phones were installed on bridges to ensure that suicidal individuals were never too far away from another person. This was the central logic behind the New York State Bridge Authority’s decision to put an emergency hotline on every bridge: “Maintaining a human connection with a suicidal individual is the best way to ensure that person’s survival.” In 2007, just months after the program had been put into place, the Bridge Authority credited these phones with saving multiple lives.

But sometimes we don’t want to talk to other people. We express our issues obliquely and to inanimate objects. We don’t say how we feel, but we give off signals that a device can understand. That, in its own way, puts pressure on all sorts of humans. How are engineers at Google, Apple, or Microsoft to design devices that anticipate all such eventualities? While it may be clear that technology could do much better at dealing with expressions of desperation or suicidal ideation, it is hard to say what a satisfactory outcome would look like. Researchers can point at embarrassing flaws in each phone out there, but we also need a discussion about what would constitute success. As with humans, there is a need to be empathetic—you can’t anticipate every eventuality, and that is not your fault—but technologists have the advantage of time to map out possibilities that humans dealing with mental health struggles do not. It’s one thing for a human to make things up as they go along, but it is another story entirely when a device stumbles in this way.

You can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at: 1-800-273-8255.

Header photo by Aaron Favila, via Associated Press

Upcoming game uses MS Paint-style art to evoke peacefulness

Gebub’s Adventure forces players to look past the origins of the creature they have been given control of, instead looking forward at the game’s world and secrets.

Created by John Wallie, Gebub’s Adventure is a “peaceful adventure game” that will send the titular Gebub on an exploratory journey through a strange world, meeting its characters and creatures along the way. The game’s simple, minimalist art style is something Wallie referred to me as “MS Paint method,” inspired by the game Seiklus (2003), and a style he has iterated on heavily in the past. “Experimentation is what has led me to develop the different graphical styles that I use,” he said.

Wallie’s games all share a sort-of innocent quality to them that the art style—deliberately evoking a child’s first experiments with paints—helps to inform. For example, Gebub cannot die, though Wallie says this kind of decision isn’t something with any great intention or thought philosophy behind it. “I’ve just been making things that I feel like making,” he said.

“I don’t think games need stuff like that”

But perhaps his personal faith— Wallie referred to himself as a Christian developer—has helped create this effect. “I suppose my faith in God has had an influence, although I’ve never been conscious of it,” he continued. “Perhaps one aspect that shows in my games is that I never use anything that is [not safe for work], I don’t think games need stuff like that.”

Wallie has currently taken Gebub’s Adventure to Kickstarter in an effort to fund a score, written by Marius Masalar, a graduate of the Berklee College of Music. “I’ve felt from the beginning that the game called for an orchestral soundtrack, especially with piano,” Wallie said. He is asking for $3500 in total.

You can keep up with Gebub’s Adventure’s development on Wallie’s development blog. You can also check out his freeware games and follow him on Twitter.

Wireframe church looks like a videogame’s debug mode made real

Ruins force the present to live right next to the distant past. In Rome, traffic passes by the Colosseum, which has mostly survived and been restored, but sites such as the Circus Maximus are obvious because of their absence. There are no cafes or shops on this enormous oval, and it’s surrounded on all sides by a uniform and evenly-sloped hill that suggests human labor, but the open park is all that’s left to suggest there was something there.

One imagines the spaces that used to be present—stadium seating, booths for the wealthy—stretching up beside and above them. In ruins, it is difficult not to think of the past as a ghost both present and not—we’re standing on the same ground, there were people here, a wall there.

In the Archaeological Park of Siponto in Puglia, Italy, Edoardo Tresoldi has carried out a project that makes the past a little more palpable. With help from the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, he has reconstructed out of wire mesh an early Christian church in the site where it once stood.

The result is a structure with impressive detail—the cornices, columns, and archways are delicately preserved. The architectural forms match those of the distant past, but the building material is wire instead of heavy stone, and the church seems to float, to barely be there. Additionally, the ceiling features exposed wire-frame beams, as if to suggest a greater unfinishedness—the wire structure is a stark and ethereal representation of a part of the whole. It looks like something pulled out of the magical realism of Kentucky Route Zero (2013).

Tresoldi’s ghost church is representative or suggestive

As in the wireframe of a 3D model, you can look through part of the church to the rest of it. You can see all of it at once, like it’s been pressed—flattened into an image where nothing is hidden behind a wall or roof, almost like seeing it from several angles at once. But Tresoldi’s ghost church is representative or suggestive, whereas the wireframe in, say, a videogame is constructive and exhaustive. A model’s wireframe (typically seen in a debug mode) dictates the way a shape will be formed and it expects to be filled in with polygons and textures. But in Puglia, the space left by the ruins has been filled in by this structure, which looks back towards what was there. All that’s left of the Basilica is this suggestion, now made physical, but still only half present.

Tresoldi has worked in wire before. Some of his other pieces resemble similar structures, some represent the tension and weight in a human body, or a single moment in the flight of a bird. More of his work can be found here.

All images © Blind Eye Factory

h/t Colossal

Gunkatana introduces a lightning-fast bloodsport to cyberpunk

What should you do when mega-corporations control everything? If you look to movies, books and television for ideas, you should stand up and fight. Start a revolution or join an already existing one. But the citizens of upcoming top-down, multiplayer action game Gunkantana have lost hope. Instead of fighting back, they’ve set up death arenas in places like strip-clubs where they brutally kill each other for sport. It’s a cyberpunk future filled with bloody swords, laser guns, and rails on which to grind.

“Two years ago, the Loading Bar, a videogame-infused pub, hosted the Multiclash event, dedicated exclusively to local multiplayer games from local indie devs,” says Geraldo Nascimento, creator of Gunkatana and founder of Torn Page Games. “I was playing around with Unity in my free time and I thought it would be great if I could quickly prototype something to showcase at the event.”

Gunkatana is at its best when it’s going turbo-fast

Nascimento had recently seen the Hotline Miami 2 (2015) trailer and wanted to make a game that was as bloody and action-packed as that trailer. But the idea to make a top-down 2D action game had been in Nascimento’s head for years. And the cyberpunk aesthetic was something that Nascimento had been interested ever since playing the point-and-click DOS game DreamWeb (1994). But it was influence from The Matrix (1999), specifically it’s wall-running, that would end up adding the game’s unique feature—speed rails.

The speed rails are laid out in each level in a way that allows you to move around the space quickly. These rails don’t just add speed to the game, they also give you more options to attack and escape. To use the speed rails you simply pull the left trigger and your cyberpunk samurai begins grinding. While grinding you can attack other players; these moments are when the speed of Gunkatana is at its highest. And Gunkatana is at its best when it’s going turbo-fast.

Gunkatana isn’t finished yet, but its alpha demo has seen over 2,000 downloads already. Riding on the rails of this enthusiasm, Torn Page Games is looking to take Gunkatana to Steam, but before then a crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter, which launched yesterday, is necessary to help finish it.

Nascimento says the Kickstarter funds will be used to add new modes like a story-driven campaign. He also hopes the Kickstarter will allow them to reach more people around the globe. “[We want] to get in touch with the global community, to expand our reach and let people know: Gunkatana IS COMING FOR YOU.”

If the crowdfunding is successful, Nascimento says “new moves beyond lasers and swords,” will be added. “There’s also a long list of powerups we want to implement, from different weapons to armor so the game isn’t just one-hit kills,” he said. He also has plans to expand the speed rails to “include tricks, smoother experience, [and] racking in points.”

Gunkatana is coming to PC, Mac and Linux sometime later this year. It could come to consoles if the crowdfunding creates a budget for it. You can support Gunkatana on Kickstarter and download its alpha demo on itch.io.

Two5six is now The Kill Screen Festival

Join us June 4th, 2016 for our fourth annual festival. The Kill Screen Festival, formerly Two5six, is a weekend dedicated to celebrating creative collaboration between games and other great art. We bring together two speakers, one from within games and one from without, to discuss a topic pertinent to both of their work. The conversations that result are often unexpected but always interesting and inspiring. This festival has a lot to offer everyone from those who play games religiously to those who don’t know Link from Zelda.

Our lineup this year features some of the most promising creators in independent gaming alongside some trailblazing game developers from decades past. Headlining as keynotes are Rand and Robyn Miller, the brother duo that created 90s cult favorite (and childhood-shaper of many) Myst. Other speakers include celebrated independent game makers such as Nina Freeman, Rami Ismail, and Jake Elliot. Non-games speakers are still being rounded out but they already include some of the coolest voices in television production, comics, and animation. For our constantly updating full lineup, check out Kill Screen Fest’s website.

This year’s festival will return to Roulette in downtown Brooklyn, the site of our 2014 conference. It will be held June 4th, 2016 from 10am-6pm, with festivities to follow. There will be an arcade and film fest that will be open to the public, announcement to follow when more details are available.

To keep up with all the latest news about this year’s Kill Screen Festival, sign up for our mailing list now. Or you can go ahead and buy a discounted early bird ticket before they’re sold out. Follow Kill Screen on Twitter for live updates, and don’t forget to come hang out with the cool kids in Brooklyn this June 4th.

Powered by Eventbrite

Philosophical mobile game reimagines Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal

Rocco Salvetti might be not your typical videogame maker. After studying philosophy, he decided he wanted a new adventure in IT. “I had a good job, but curiosity took over. I left and started all over,” he said. He moved from Italy to England, finding in London the right place to settle down and to run away from the stillness of small towns: “I need a massive city not to get depressed and it has been four years now, maybe I should consider Tokyo.”

It is this hunger for more that describes Sara, Salvetti’s alter ego, and the protagonist of his game Sara and Death. Available for free on Google Play and iTunes, this little philosophical puzzle game is a noble move against the tendency in the market for mobile games. “It was made as an antidote to Candy Crush (2012), its poor taste and addictive gameplay. Drugs are addictive, not games”, argues Salvetti. It’s this attitude that encouraged him to make it ad-free too, refusing to monetize it as that kind of move “demands some design choices.” He says he wanted this game to be strictly personal: “You don’t monetize on such gloomy name or colors. My point is: you can do poetry and philosophy with videogames. Cinema did, sculpture too, why not videogames?”

“Death kinda works as a mirror”

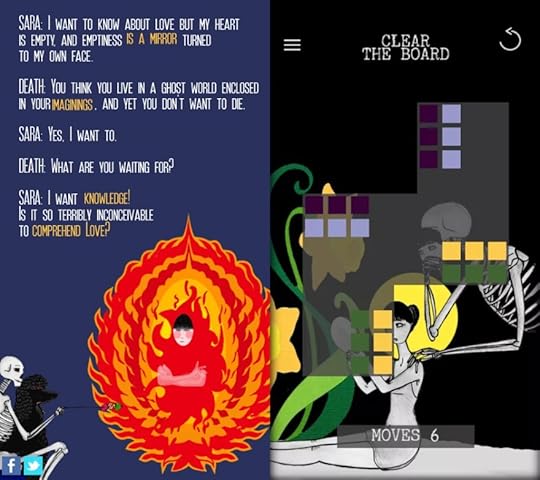

A fan of Ingmar Bergman, with Sarah and Death, Salvetti has created a game that was very much inspired by The Seventh Seal (1957). Salvetti included some lines from the movie, but also wrote new reflections when Sara is in conversation with Death. This time, it’s not about God, but about love, as she doesn’t believe in that anymore. However, Sara is not ready to die, so the trick is to invite Death to a game that you will play for her. In The Seventh Seal, Death tells his victim, the knight Antonius Block, that he keeps asking questions, even though he never gets any answer. The same goes for Sara: “I want to know about love, but my heart is empty and emptiness is a mirror turned to my own face.”

Inspired by the puzzles of Mean Bean Machine (1993) and 2048 (2014), Sara and Death was designed to have the player follow a few simple rules, but with every level feeling different and more challenging. “Some levels are based on rational solutions, others will make you deal with chance. I wanted an element of gamble. I wanted the player to be able to brute force the solution if [they are] the persistent type,” says Salvetti.

That persistence is something that Sarah embodies. Here, she represents the archetype of human curiosity, always wanting more despite being frequently disappointed. Her hunger is as big as the one brilliantly portrayed in the short animation Coda (2014), by Alan Holly, but Sara doesn’t have the same feedback from Death. “No matter how hard Sara tries, puzzle after puzzle she keeps running in circles because she is talking to herself. Death kinda works as a mirror,” Salvetti reasons. And as empty as Sara feels, empty too are the replies she gets. It works pretty much like the dialogues of Antonius Block’s nihilistic squire, Jöns — some of them being paraphrased and modified according to the game’s context.

Sara and Death ends up being a simple but very detailed game. Even its icon on App Store pages, which is the character inside a nutshell, gives a hint about its message: “The dying fruit doesn’t know about the seeds it is concealing. Death in this game is a metaphor for the end of a period of her life, yet the last level doesn’t really end.

Salvetti got some help from friends while creating Sara and Death. In fact, Sara Bodini is a real person. She lives in Milan and is the illustrator on this project. “I also bugged Sole Varichio and Marica Innocente to learn how to match colors. Each background color could potentially have blocks of seven different colors, so finding a good contrast that didn’t look tacky or like shiny candies was difficult,” says Salvetti. And as to the soundtrack, all the music was composed by Marc Santos, and it seems hell be working on more tracks for the game — Salvetti says he wants a different one for every two chapters, at least.

Salvetti is not exactly an outsider to videogame development: he also creates casual games for practicing and to train people. Also, Sara and Death is not the end of his independent game-making road. He will be releasing a new title soon, Trump in the Sky, and after that he will move onto his next personal project: “It will be inspired by [Ryu Murakami’s] Tokyo Decadence (1992) and it will be about my London.”

You can download Sara and Death for free on Google Play and the App Store.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers