Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 139

April 7, 2016

Play against yourself in #SelfieTennis, a new virtual reality game

Playing tennis against yourself, running back-and-forth between either side of the court, is an almost impossible pursuit. Luckily, for any lonely soul out there that may try soloing the ball-and-racket sport, it’s now been made a whole lot easier thanks to virtual reality. #SelfieTennis, the social media-ready commercial debut from VRUnicorns has been released via Valve’s Steam VR platform as a launch title for the HTC Vive headset. It is a game, nay, a virtual experience that uses the magic of VR to let you participate on both sides of a singles tennis match.

Actually, “match” isn’t the right word for the average game of #SelfieTennis. This is not a game of forty-loves and deuces. Scoring is defined by total number of volleys, resulting in an arcade-style high-score mentality rather than the competition of traditional tennis. It also results in a visually bonkers circumstance where every time the ball passes over the net you are teleported to the opposite side.

a virtual court is defined by its freedom

Nintendo’s Wii Sports (2006) realized tennis with tactile-to-visual feedback that proved surprisingly compelling, despite a total lack of control over your avatar’s legs. In #SelfieTennis, however, your whole body is the avatar—including your legs—and thanks to the room-scanning functionality of the Vive, not only do you navigate virtual 3D space, you navigate physical 3D space too. And what a delicious virtual space it is. Everything looks like soft candy—creamy or chewy. In the same way that sugar appeals to our taste buds, the immediacy of feedback within a virtual space should lure in our eyes, ears, and hands.

“Now, wait a minute,” you might be thinking. “Hasn’t single player tennis already been solved through the invention of squash?” Well, sure. But there is a significant difference between a physical court and the virtual court of #SelfieTennis, and it’s one that’s more important than the fact that you are competing against yourself: where a physical court is defined by hard and fast rules, a virtual court is defined by its freedom. Without rules, a tennis court is just some grass (or, heaven forbid, clay) and two weirdos swinging clubs on either side of a large net. Sometimes they hit a ball back-and-forth. But without the regulations of the game, well, either you get bored or, if you’re more imaginative, the possibilities multiply.

#SelfieTennis takes the three basic elements of tennis—the ball, the racket, the people—and invites you to do whatever the heck you want with them. Without the rules of the physical court, that club in your hand becomes a far more versatile and potentially violent device. In one promotional video, creator VRUnicorns recommends “how to get your aggression out of your system when you suck,” and our unseen player begins mercilessly beating down the tennis-headed people who have been cheerily observing the one-on-none matches. There are other, less violent options available to you, but you’ll have to explore those for yourself.

#SelfieTennis is now available to purchase on Steam VR.

An upcoming puzzle game tasks you with decoding classic literature

In the world of Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451, books have been outlawed and are burned en masse by the state, only kept in small collections by the occasional revolutionary. Instead of reading, the majority of people spend their free time in “entertainment parlors,” rooms lined with massive screens that constantly broadcast Dora the Explorer-style call-and-response programs meant to elicit the illusion of interactivity.

It’s a pointed premise, conceived during the early years of the television’s rise to prominence in the American household. It also reflects a constant theme in Bradbury’s work: that with advances in technology, culture tends to be forgotten. In Losswords, an upcoming puzzle game for iOS from The Metagame creators Local No. 12, it is the player’s duty to put that culture back together again.

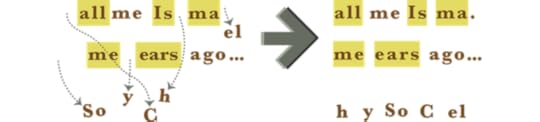

Losswords has the player take on the role of a literary outlaw. They’re part of a subculture that scrambles and unscrambles books to keep them out of the hands of a government that has banned them in favor of a society where the only legal media is videogames. This is done through a series of puzzles in which the player reads through passages from actual classic books and tries to find smaller words within the passage’s existing words, similar to decoding a Boggle grid.

For instance, if the passage contains the word “unlimited,” the player can highlight “limit” to add to their score. Find every word-within-the-words hidden in the passage, and you get to add that book to your profile’s library, where you can read a description of it as well as a small excerpt. At the same time, you’ll be generating a puzzle for another player to solve, in which they’ll try to put the passage back together again by placing the words you found back within their original, larger words.

I got a chance to play a demo of the game during a meeting with the creators over the weekend, and even if my actual skill with it—or lack thereof—had me questioning my writing talent, I saw the appeal fairly quickly. As I was playing, I felt the same feeling I do when solving a crossword or trying to plan a move in Scrabble. “How did no one think of this before?” I wondered. As novel as the game is, it plays with the same confidence as a hundred-year-old classic.

“What if we made a game for librarians?”

“We like to invent new forms of play,” Eric Zimmerman, one of the game’s designers, told me. “And we like the idea of using culture as our playing field.” This trend can be seen across Local No. 12’s previous work, which includes Backchatter, a Twitter game in which players have to guess which words they think people will tweet most during an event, as well as the aforementioned The Metagame, a card game that encourages players to debate aspects of pop culture, history, art, and of course, fast food hamburgers. “We really want to think about games as a form of culture alongside film, music, theater, and literature,” explained Eric.

The hope is that Losswords will act as a vehicle for literary discovery, as each of the books used to create the game’s puzzles are in the public domain and currently available for free through the archival website Project Gutenberg. “What we hope is that we spark people’s curiosity about a particular book,” Zimmerman told me. “And they end up going out and reading it.”

Despite the game’s setting, which seems to poke fun at videogames, the development team is actually made up entirely of professors who specialize in teaching game design. “We’re not just designers, but also design educators,” Zimmerman told me. “We play lots of different videogames.” With Losswords, the creators not only hope to help people who enjoy videogames find more reading material, but also help introduce videogames to people who might not usually play them. “What if we made a game for people who really like books?” asked designer Colleen Macklin. “What if we made a game for librarians?”

Local No. 12 is currently holding a Kickstarter campaign to complete development of Losswords. They hope to release it some time next year.

Optikammer will let you play with the 19th century’s weirdest toys

In 1878, famous industrialist Leland Stanford (yes, that Stanford) wanted the answer to a very important, deeply contested question: do all four of a horse’s hooves ever come off the ground when they gallop? So he did what all millionaires do and he spent money, commissioning the photographer Eadweard Muybridge to photograph a horse in motion.

The resulting series, known as Sallie Gardner at a Gallop, is perhaps one of the most famous early images and a precursor to the technology that would be used by the Lumière brothers in the 1890s to produce films. By taking 24 cameras and rigging them around a track, and creating a tripwire that would activate when the horse ran across it, Muybridge was able to capture 24 shots (in order) of the horse in motion and finding that yes, at some points, all four hooves are off the ground.

Optikammer is the story of weird and disparate research

Oddities such as this, and more, are the basis of Optikammer. A “playable poster” that showcases weird toys and artifacts from the 1800s, Optikammer seeks to bridge the gap between these interesting historical oddities and the ability to actually play with them.

If you found a Zoetrope (a “pre-film” animation device) from that era you wouldn’t really be able to play with it, to engage with it in the manner the the original creator intended. It’s fragile, an antique. Optikammer allows you to experience it in full motion, to bring the reality of the device to life in living color. These devices, so often intended for play but protected by glass are the given vibrancy and detail, even with their stuttered, time-specific animation.

Ultimately, Optikammer is the story of weird and disparate research, creators from around the world observing cartwheels through fence posts and bringing them together as an interactive exhibition. It gives life and color to these early prototypes, the precursors to everything from stop-motion animation to cat gifs.

Optikammer is coming in late 2016 for PC, Mac, Linux, Web. You can find out more on its website.

Short documentary details the creation of a “fine art videogame”

“What do you get when you take a painter with a penchant for the peculiar and a programmer fluent in pixels?”

That is the question posed by JJ Walker’s short documentary, Canvas+Code, which follows Ryan Ford and Brad Henderson, the painter and programmer that make up Globhammer. The documentary has been out for a few days now, and is currently available to watch on Vimeo. The seven-minute-long short film gives viewers a brief look at the duo, with both sharing small details about how they met, their respective thoughts on art and videogames, and just what, exactly, Globhammer means.

“When I said [Globhammer], I was just joking; for some reason I just loved the sound of it,” explains Ford in the documentary. “But there was something in the back of my head that was saying to me ‘you’re going to revisit this title.’ And then, of course, three or four years later, old friend Brad Henderson from college shows up at my door and is checking out my oil paintings, and he’s all excited like ‘hey man, I want to make videogames [out] of your paintings.'”

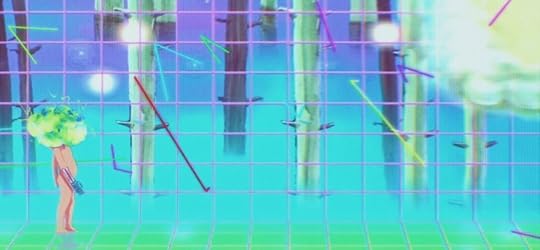

As for what Globhammer really is, the pair describes it as being a videogame-focused, artist collective that’s main focus is to create “a gaming experience that delivers the player into a fine art environment.” The visual and emotional experience of each potential player comes first, followed by the utilization of current technology to bring Ford and Henderson’s thoughts and ideas into the world. Their first game, SRC 1515, a platform-inspired side-scroller set in the medieval future, is the end result.

“it’s nice just being able to take those images and bring them to life digitally”

Ford says his primary inspirations for his art are 14th-16th century Sienese Italian paintings and Super Mario Bros (1985). Both of these influences can be seen towards the end of the film, which shows what’s presumed to be the earlier parts of the upcoming game. “He can just create these shapes and forms [from] his mind by just using a paintbrush or a pencil, and they have such a nice style and feel to them,” says Henderson. “I think he has an incredible imagination and it’s nice just being able to take those images and bring them to life digitally.”

SRC 1515 is designed to play in modern web browsers upon its release, and is at its best when played at 1080p. However, it doesn’t have a release date yet, leaving us with Canvas+Code and the game’s Kickstarter campaign from 2014 to provide more details about the game’s setting, protagonist Minerva, and the environments players can look forward to playing in.

Find out more about and watch Canvas+Code on its website.

Hyper Light Drifter cuts through the noise

Silence is difficult for most of us. It’s not just screens that prevent it, the ubiquity of entertainment and distraction, or the pace of modern life—though, that and more contributes to the difficulty of easing through the din. The chaff of life is a billowy recliner, keeping us cozy against the chaos in our minds. But there is something to gain in sitting in silence on a bare floor and using the low-cycle hum around you to pluck the signal from among scattered thoughts.

Hyper Light Drifter merges a sense of silence with what eventually becomes instinctive action. It’s a zen garden in an arena; a mostly ambient adventure game; a taut and nearly wordless journey that accentuates the top-down mystery of The Legend of Zelda (1986). It does this especially with its narrative and visual palette that evokes Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski’s use of color and lingering lens.

It is a game that wants to be contemplated extensively

You play as the eponymous Drifter, one of a few ronin wandering the ruins of one civilization while another is starting to fill in the void left behind. The story is primarily visual: as you meet locals they show you their tales through single-panel vignettes that detail the threats and travesties they’ve endured. As such, many of the beats are inferred. Where the drifter drifted in from is unclear, but he is constantly flashing back to an Akira (1988)-like explosion and a scene of menacing giants while intermittently coughing up fluorescent blood. It’s assumed you’re looking for a way to stop it all.

The stakes are large but the playable world is small and hushed, and to the game’s advantage—for the most part, you are left to explore at will with only a few barriers preventing entry to some spots meant for later. It’s a gnarled little knot of a place with four distinct sections spread evenly around a hub. It’s robust without being stretched thin, coiled tight like gray matter. This is why exploration never feels like busywork: repetition is minimized, the game instead encouraging you to be thorough so as to discover secrets that lead to a means to improve your moveset, but also to find vistas fit for for a brief moment of quietude that are impossible to stockpile. It is a game that wants to be contemplated extensively, for you to look and listen. And once an area has been charted you can dash back through, skeletons and corroded detritus whispering small stories as you pass, the only respite forced on you by cliffs arched with the mouldering corpses of golems, demanding that you utilize the “sit” button to take in the scenery.

Which isn’t to say that things don’t get busy: this isn’t a garden stroll made of pixels. To maintain equilibrium with the environmental exposition, Hyper Light Drifter offers tense and agile combat. The rhythms of the Batman Arkham series’ dance-battle flow are spliced with more traditional top-down sword-fighting and Mega Man Zero’s (2002) dashes; nimble zips across short distances that need to be metered for survival. Eventually you’ll cop a side arm, of which many varieties are offered through progress, and you can develop grenades as well as upgrades to these, your health, and your dash. Slash-mashing is the default tactic but it’s as uncivilized as splashing around in a koi pond. This game demands in battle what it offers in the more somber exploratory moments: clearing out the clamor of the mind in order to focus and strike clearly, especially when swarmed with enemies.

a regular tick that helps straighten out the otherwise violent cacophony

A pack of crystalline wolves that close in quickly should be dodged before countering. An army of shinobi frogs that can keep you from cinching the distance with a flurry of shurikens are best handled by singular sniping. Almost every enemy can take more than a few hits, from the vulture wizards and their strummed magic to the halberd-swinging footsoldiers, and they will all try to confound you with tumultuous ferocity. But you are capable of zeroing on your own signal and dashing around them like a spirograph—your agility helps with forgetting that failure will lead to a glitched-out demise. It’s a disparate but complementary orchestra of combat scenarios that can be tuned as necessary or desired, with the gun requiring swipes at enemies to recharge and the saber being just short enough to make close combat a calculated risk.

And by the time you get to the bigger bosses, you’d best be girded for an uproar that will almost certainly shatter your tranquility. They’re fast and savage, with health to spare, which makes the first few encounters with each wildly dispiriting. But these losses bring new intel on the patterns of their brutality, with telegraphs of what’s to come, teaching you what to anticipate rather than mindlessly dance around. It’s all discordantly quick, and that’s where the path of the sword comes into play—deduce their style and then dash in-and-out almost automatically, freeing all noisy thoughts in order to focus on pure action. Eventually, they will fall from a thousand whirring cuts. Combat is arduous but not cheap, a system thorough enough to offer several strategies without becoming overwhelming or a matter of rock-paper-scissors. You are as if a metronome, introducing a regular tick that helps straighten out the otherwise violent cacophony.

More so than anything else, the loom that weaves the fabric of Hyper Light Drifter is the sound. Early in each area, Disasterpeace’s music is slight and whispery, setting an ambience of exploration. This puts you in a meditative state that encourages you to poke around, to bathe in the rich glowing sunset and find those secrets. Doing so really taps into your exploratory impulses and the joys of dashing. As you hunt around, critters will interrupt, and the music adjusts accordingly. But the tracks never explicitly change: they shift, simmer, evolve, oscillate like the tide. Inching closer to the end of an area leads to a sonic throb but stops short of getting outright raucous, and even the boss fight tracks are tense but not intense. The soundtrack lulls and locks you in by avoiding the temptation to explicitly disrupt the established balance. Such sonority is practically radical in traditional adventure game space—this is not pendulous manipulation meant to keep the player swinging between extreme bipolarity, rather, it explores the nuance in a somewhat narrow spectrum and wrings nearly as much emotion from it.

Hyper Light Drifter plays with seconds of crisp silence and dramatic intervals like an opera. The visuals and atmospheric narrative lovingly conducts the eye through a neon-futurist aria that does occasionally feel maudlin, what with the frequent allusions to the proximity to death, but this is hardly unforgivable. Out of the void, Hyper Light Drifter meticulously crafts a post-apocalyptic samurai story, one that bends and folds the tenets of zen’s vivid ambience alongside the warrior path of bushido, something familiar yet fresh, quiet yet resonant.

April 6, 2016

Videogame takes competitive cooking shows to their wildest conclusion

The Chairman looks out over the assembled chefs in their whites and tall hats and announces that the secret ingredient is … meteors! Kitchen Stadium is now in space. It’s like the kind of dream you’d fall into after spending a late night huddled around a small TV in your bedroom watching Iron Chef. Except it’s multiplayer and coming soon to PC.

Iron Chef, in its wildest imaginings, never actually put chefs on ice-floes and demanded that they appease an ungracious audience. But then, Iron Chef is not Overcooked—the new couch co-op game for 1-4 players from Ghost Town Games. While reality television will have them make children’s food out of monkfish, Overcooked is willing to literally throw their cooks into the bowels of hell and demand a proper risotto. Possibly because they’re made of pixels rather than flesh, but there’s little that reality kings won’t do for ratings.

With reality cooking shows finding new ways to torment their captive CIA graduates, (episodes of Chopped have required contestants to cook while on a treadmill) it’s little wonder that videogames have taken the situation to its logical conclusion. Cook while moving between speeding trucks. Or in the middle of an earthquake. Or on a bucking pirate ship. Wait ’til the Food Network gets a load of this.

the real struggle of being a line-cook, now with optional friend murder

In case this all sounded too easy, Overcooked allows for the culinary masochist to control two characters on the same controller (or split the difference with a friend). Experience the real struggle of being a line-cook, now with optional friend murder. Finish quickly and correctly and you’ve found yourself to Michelin Star success. Fail and your customers will leave to find a new restaurant. In hell?

Overcooked will be available on PC and consoles soon. You can currently check it out on its website and over on Steam.

Bad Corgi lets you run wild as a mischievous dog

If you only know corgis as those cute dogs from the internet, Cowboy Bebop, or movies where someone visits Buckingham Palace, you might not know that the tail-less fuzzballs are actually bred for herding cattle. Having grown up with corgis as household pets, their herding instincts are often present, even in the absence of farm animals. When I’d attempt to slowly pull my car into the garage, there was typically a corgi blocking my path as if it wasn’t my turn to park. If I’d walk around the house barefoot, often one of the dogs would nip at my ankles to corral me toward a different room (perhaps one with treats in it). That’s animal instinct at work, and eventually you either concede to the corgis’ whims or you negotiate a truce (again, the treats).

Bad Corgi courts defiance and disorder above all else

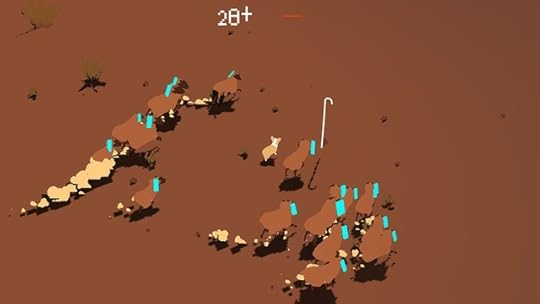

In Bad Corgi, a new app from artist Ian Cheng, you “embody” a corgi to help herd a flock of sheep. Well, perhaps “help” isn’t the right word. In your role as a bad corgi your goal is to do the opposite of maintaining a perfect herding formation—running amok among the livestock before entering into an uncontrollable fury that sends your perfection rating infinitely deep into negative figures. After one session it’s clear that Bad Corgi courts defiance and disorder above all else.

Interestingly, Bad Corgi is billed as a mindfulness app and sorted into the Health & Fitness category of Apple’s storefront. Cheng sees Bad Corgi as an experience that allows players to engage with our human instincts. those that don’t want us to be perfect but would prefer to misbehave. At a certain point in Bad Corgi, your corgi is so bad that it flashes the text “beyond control” in the middle of the screen as shrubs and sheep smolder and scatter in your corgi’s wake. There is a certain satisfaction in being a bad corgi, and even if it’s just a cute little scenario, there is a devilish glee to the endeavor that is somewhat cathartic.

Cheng is largely known for his simulations, composed of vast spaces occupied by various floating objects. These simulations act as test chambers wherein each object has its own relative entropy among other physical properties. There’s no “goal” in these simulations except to witness how the objects interact with one another in their live environments. Viewers relinquish control from the very start as the algorithm dictates what happens where.

Bad Corgi splits the difference between Cheng’s simulations and videogames, granting a certain amount of player interactivity, but never letting you be totally in control. I guess it turns out that not all corgis can be appeased with treats.

You can learn more about the design behind Bad Corgi on the Serpentine Galleries’ website, download it on the App Store, and follow Ian Cheng on Twitter.

Emoji Poetry is the literature class you never had

There’s an almost magical quality about tweets by Carrie Fisher, which probably half stems from the fact that I usually have no idea what she’s saying: her tweets are almost entirely in emoji, indiscernible like some new art form that I’m not cultured enough to understand. And with the rise of emojis changing the way we communicate for various mediums, I imagine that my confusion around their growing usage isn’t going to go anywhere.

In comes developer Arzamas OOO’s new smartphone app, Emoji Poetry, a literary game where you drag the “appropriate” emoji into the empty spaces of a popular English poem. As such, the game not only requires the player to have extensive knowledge of poems like Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ozymandias (or have access to Google), but also indirectly forces the player to understand the nuances of emoji and their ability to suggest words or meaning; the emoji here are all about interpretation and context.

the right emoji to fill in the blanks of the poem

The pool of poetry you can choose from is broad, ranging from the Renaissance era (think Milton) to the 20th century (think Yeats), and Arzamas OOO has done a pretty swell job picking high-class poets—the kind discussed in high-level English college classes. When the player thinks they’ve chosen the right emoji to fill in the blanks of the poem, the app will check your correct answers against the actual poem itself, and further point out which ones you got wrong. It’s a hard game, but proves strangely satisfying.

If you want more information about Emoji Poetry, check out the app’s iTunes page here.

Idolm@ster and the mechanics of depression

I don’t know precisely when it was I realized that I suffered from depression, but it certainly wasn’t from playing a videogame. Maybe it was from watching a red-haired, mecha-piloting girl mentally tear herself apart under the weight of her own expectations, and feeling a similar sense of despair in my own weighty ambitions that I failed. Maybe it was from re-reading the same fantasy novels about a particular boy wizard over and over again, feeling that the only escape I ever had from reality was in those books. Maybe it was from listening to early 2000s emo bands that obviously listened to a lot of The Smiths, and were the soundtrack to some of my most socially anxious years. Though most likely it was just the feeling of melancholy creeping up on the most unexpected of days, far beyond my teenage years, feelings I had earlier misguidedly ascribed to “just puberty.”

Depression is seldom implemented successfully into videogames. As a mental illness, it’s difficult to accurately emulate both for those who suffer from it and those who want to understand it better (not to mention being prone to trivialization if not handled with care and knowledge). Strangely, one of the most successful depictions of in-game depression comes from an unexpected, non-autobiographical place: the Japanese arcade title The Idolm@ster, which released in 2005.

Japan’s Idolm@ster is a bunch of different games wrapped into one tidy package: part raising simulator, part rhythm game, with bits of visual novel sprinkled in. You are a “Producer,” who, with dialogue and training, raise the “tension” meters of the roster of idols (Japanese pop stars). This tension in turn grooms them into fun-loving, do-it-all celebrities. That is, except for the quiet and somber Chihaya Kisaragi. Chihaya is an anomaly among the other girls—she’s a reluctant idol. She dances but hates practicing. She grows frustrated when prompted to change into a different outfit. She half-heartedly grins in the presence of her shadowy, omnipresent Producer, afraid to disappoint you at every turn. She’s asocial, and hardly hangs out with her peers or finds enjoyment in other hobbies (outside of listening to classical music). Instead, she focuses on singing, her only passion in the realm of her broadly defined career as an idol. In an earnest declaration, Chihaya believes that if she could no longer sing, she’d rather die. Singing keeps Chihaya alive. This is because Chihaya suffers from chronic depression, onset by witnessing the death of her younger brother as a child and her parents’ subsequent divorce. While Idolm@ster never takes the step to explicitly label Chihaya’s suffering as chronic depression, it doesn’t need to. The signs are all there.

In The Idolm@ster series, you group specific idols from the 765 Productions team together for training sessions. Where some members’ talents complement each other per song more than others, you, as the ever-vigilant Producer, must be flexible in the choices you make. Most girls are balanced in their skills, but Chihaya is different: her Visual and Dance stats are abysmal. Yet her Vocal stats are maxed out—exemplifying her stubbornness when it comes to being a self-proclaimed vocalist first, idol second. Her “tension” meter barely snails along, even at its best, and plunges dramatically if she doesn’t clear a song with a good score. If you fail to greet her, or don’t respond to her in a way she anticipates, you must idly watch as her self-esteem and desire to sing plummet. You try and try again, insensitively wanting her to do whatever you ask. Eventually her tension can drop to a low state indefinitely, as she sinks into a state of despair. Abstaining from her typical idol-activities, you become relegated to a bystander rather than someone actively sculpting Chihaya’s day. Your encouragements never befall any miraculous resolution. You become obsolete in this act, a mere witness to Chihaya’s battle with depression, unable to “save” her in any way. Idolm@ster fans have dubbed this series of events as the “Chihaya Spiral,” the rare permadeath of the rhythm game variety. This is Idolm@ster using Chihaya’s personal struggle with depression as an astoundingly accurate in-game function.

The “Chihaya Spiral” is the rare permadeath of the rhythm game variety

Idolm@ster isn’t the only game to implement depression into its core mechanics. Probably the most widely known game to emulate the illness is the 2013 text adventure Depression Quest, an interactive journey through (you guessed it) navigating life with depression. There are no happy routes or endings in Depression Quest, only the thoughts that plague your mind while trying desperately to maintain a semi-normal life. Depression Quest is not alone in its stark depiction of mental illness. There’s a plethora of other recent, likeminded “empathy” games (perhaps better regarded as interactive “tools”) seeking to help players both cope with and understand depression. There’s Macrodepression (2014), which explores the feeling of being trapped within the familiar prison of one’s own room. 2013’s Actual Sunlight (warning, spoiler:) follows the mundane day-to-day life of one man, ominously leading to his apparent suicide. The upcoming Healing Process: Tokyo aspires to simulate a Tokyo-based surgeon’s battle with regaining happiness, having lost his wife in a tragic accident.

While not namely focusing on depression, a game mechanic of grief is implemented to the 2013 adventure game Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons. Throughout the game, you are controlling two brothers: one using the left analog stick, the other using the right. During a climactic moment—spoiler alert!—one of the brothers dies, and you effectively lose half of your mobility as a result. Having played the game entirely to this point with the two characters, the loss of one half resonates powerfully in a way that wouldn’t have been the same if it were merely a story beat. You, the player, have lost your other half, and you feel it.

While these games seek to ease you into the experiences of the characters’ suffering, they differ from The Idolm@ster’s outsider perspective. Being Chihaya’s boss (the Producer), you hope to be perceived as Chihaya’s friend. Through the mechanics of not being able to shape Chihaya as you normally would with the other idols, her emotions are given more weight; she feels singular in her actions. In another raising sim/rhythm game like Project Diva F (2012), you can feed a Vocaloid, such as Hatsune Miku (another digital idol), a food they don’t like, and they simply pout in disgust. Whereas in Idolm@ster, Chihaya grows increasingly emotionally unstable at the turn of a conversation or after a bad training session or concert, and the reality of her ongoing interior suffering dawns on you, time and time again.

Idols beyond the digital world have long been a symbol of all things cute in Japan. They smile brightly, bend and twist into coy poses for photo ops. Their wholesome, adorable image is reinforced by their saccharine singing, dancing, and television appearances. Idols embody more than just being musicians: they’re the everygirl’s role model. The underdog who was able to make her dreams come true. Though in some cases, this outside sunny demeanor is just an elaborate facade, a mask to hide behind in hopes of building a marketable career.

Idols embody more than just being musicians: they’re the everygirl’s role model

Perhaps most notable of this complex professional existence is that of 1980s teen pop idol Yukiko Okada, who committed suicide when she was just 18 years old. Okada was young during her rise to fame, winning the top prize of a televised talent show in 1983, which propelled her into Japan-wide fame. Okada went on to sing jingles for commercials, top the Oricon charts (essentially Japan’s Billboard) and even star in a Japanese drama series—then she leapt from the seven-story Sun Music Agency building. Okada was not vocal prior to her death about her now-speculated struggle with depression, yet her suicide singlehandedly shattered the “perfection” that idols were seen as in the industry. Her shocking death was one of the first to shed light on the staggering trend of depression and suicide in Japan.

As a popular idol in the peak of the 80s “idol period,” Okada wasn’t given much room to be herself at all, and only existed to the public as the smiling teen dream her management sculpted her into being. Chihaya, like the other idols in Idolm@ster, is in contrast given a personality behind the idol facade, and given her own sense of agency in the behind-the-scenes nature of the game. She exists beyond the title of just being another interchangeable idol, as so many popular idol groups (such as the massive AKB48) are seen as today.

With Chihaya’s gameplay arch, Idolm@ster builds a new narrative, defying the depression recovery narrative that plagues many films and television shows of today. In the overwrought depression recovery narrative, victims can eventually “overcome” depression. Whether the “cure” is through medication, therapy, or just good ol’ epiphanies, it’s almost always followed with a shoulder shrug of the bout of depression merely being a mark of “past” suffering, never looking to the future. Idolm@ster looks to the future, the past, and the present of living with a mental illness. It doesn’t sugarcoat Chihaya’s disposition, it simply presents her pain as one part of an unbridled look at a human being. Chihaya’s depression, like all depression, is all encompassing.

Despite the existence of the Chihaya Spiral, it’s important to note that Chihaya isn’t perpetually in despair. When she succeeds, she still inches forward, her tension meter snails its way upward. She has her good days, just as she has her bad days. Chihaya is not solely her depression. She exists beyond her illness with the admiration and respect she feels deep down for her peers, for her late brother, for her craft. While the anime counterpart of Idolm@ster narrowly sidesteps the trope of “overcoming” her depression, Chihaya effectively channels the grief she feels for her late brother into her music, culminating as a powerful song. In the later, non-arcade Idolm@ster games, there’s no game-crushing Chihaya Spiral, though she does remain one of the harder idols to train to perfection. She’s relatable in the sense of the duality of her personality. She suffers, but she shines, just as I do and everyone else that suffers from a mental illness. It’s a clear example of the power of an interactive and playable medium, versus film or literature, and its ability to transport players into a situation they would not otherwise find themselves—or happen to live everyday. Depression will always be around for Chihaya, but in eventually opening up, she feels at least a little more free.

April 5, 2016

Lieve Oma, a poetic game about appreciating your grandma

Dedicated to grandmas everywhere, Lieve Oma (translated from the Dutch as “Dear Grandma”) is a game that speaks to the way we come to associate places in the world with the loved ones we once shared them with. Creator Florian Veltman has now released it on itch.io after having spent the past few months arranging the trees and rivers of the game’s forest to his liking—an act that he previously told me felt akin to grafting a portrait of his own grandma. “Not because of the ‘autumnal sunset colours’, but because despite what it may evoke on the surface, everything still seems very vibrant, warm, and pleasant,” Veltman said.

Looking under the surface to find warmth, it turns out, is a major theme of Lieve Oma. In it, you play a young girl who goes mushroom picking in an autumn forest with her grandma. The pair talk as they step over the early morning brushwood, the grandma asking the questions and picking out nature’s terrific sights, while the girl seems uneasy as she answers mostly with ellipsis. There’s something going on in this little girl’s life, and it becomes apparent that the grandma has taken her away from it all, to this serene and rejuvenating forest, to help her talk through it.

How the grandma gets to the truthful feelings that her granddaughter is trying to bury is subtle—she isn’t forceful, but patient and gentle, showing utmost love and care in her conversation. The game follows the grandma’s example in its approach to getting its story across to you. While the dialog is the most obvious storytelling device, there are many more for the eye to tease out; it’s a game brimming with small gestures. Everything from the difference in the pair’s walking animations—the grandma hunched over and slow, the girl much more springy—to the font inside their speech bubbles seems to have something to tell you.

Lieve Oma is full of moments like these

The use of the game’s camera is perhaps the most graceful of these storytelling tools. It starts out fixed just above the two characters, giving you a clear view of the forest surroundings in a way that encourages you to explore the path ahead, or to even leave the path and find mushrooms deeper among the trees. It seems to reflect not only the wanderlust of the granddaughter but her initial unwillingness to talk to her grandma—at this stage, she prefers to avoid answering the prying questions altogether, and so it seems fitting that she would want to run away from her grandma into the woods, alone. Later on, the camera subtly shifts to a higher, more distant perspective to give you an overhead view. From here, you cannot see what’s ahead so much, and so rather than explore you feel inclined to keep the girl closer to her grandma as she walks the dirt path through the denser parts of the forest. It seems like no great coincidence that it’s also during this section that the two start to break through the discomfort in their conversation and become emotionally and spiritually closer.

The walk through the forest with the grandma is broken up with scenes from the girl’s future (or, perhaps more accurately, her present), when she is old enough to drive. These wintry scenes, in which the girl walks alone through the same forest as she used to with her grandma, frames the autumn scenes as memories from the past—it’s as if she’s walking through the forest to make a physical connection back to that time, to remember it. At one point in the past, the grandma and the girl search for a blue heron they usually see stood in a river, but it’s not there. When revisiting this place with the older version of the girl, the blue heron is seen stood in the river, but the grandma isn’t there to acknowledge this. And so seeing it seems to take on a greater meaning, as if the young girl is carrying her grandma’s presence on in her absence; the sight of the blue heron acting as a metaphor for the connection they established in this forest years ago.

Lieve Oma is full of moments like these that evoke both sorrow for the times lost to the past and an appreciation that the connections made back then between the girl, the forest, and her grandmother happened at all.

You can purchase Lieve Oma over on itch.io.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers