Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 142

March 31, 2016

The loneliness of the professional gamer

If you haven’t heard of Jonathan Sutak, producer and director of The Foreigner, a new documentary about professional StarCraft II (2010), you can take solace in knowing that you’ve probably seen some of his work. Not, mind you, the two independent dramas—Up The River (2015), a romance, and Don’t Worry Baby (2015), a comedy—he’s produced; you haven’t seen those. What you have seen are the many trailers and TV spots he’s edited, for films as far afield as Everest (2015) and Kingsman: The Secret Service (2015). If not exactly a Hollywood insider, Sutak nevertheless approaches filmmaking from the perspective of someone who operates in the conventions of popular film. For this reason, Sutak bristles at the suggestion that The Foreigner is an ‘esports documentary.’ What it really is, in his words, is a ‘documentary about esports.’

Semantics? Perhaps. But, for Sutak at least, this distinction is significant. As he explains, it situates the director of a documentary in relation to its subject. Sutak insists that, despite being a ‘fan’ of esports, he has never been “part of the esports community . . . because [he] wanted to remain objective while documenting it.” The Foreigner, in other words, is the creation of a documentarian interested in esports, not an esports fan interested in documentaries. Whether or not you find it convincing, Sutak’s statement takes on particular importance at a moment when esports seems to be shedding its subcultural insularity. With esports popping up in more and more places—even démodé Yahoo! has launched an esports division—it’s worth questioning where and why the boundary Sutak alludes to is drawn. What is ‘in’, what is ‘out’? What does it even mean to be ‘in’ or ‘out’? What’s the difference between an esports documentary and a documentary about esports, and does that difference really matter?

What is ‘in’, what is ‘out’? What does it even mean to be ‘in’ or ‘out’?

As it turns out, The Foreigner, and its place in the surprisingly robust canon of esports documentaries, presents an ideal opportunity to ruminate on these questions. Conservatively, since 2000, directors both professional and amateur have produced over 70 esports documentaries of widely varying length and quality. Taken together, they exhibit a tremendous diversity of approaches, audiences, and attitudes. At a brief 22 minutes, The Foreigner is Sutak’s small contribution to this tradition. Yet it is, I propose, also among the most significant. That’s not to say that it’s either the ‘best’ or most ‘well-produced.’ Too often, we take quality and significance to be synonymous, a critical elision that can blind us to films whose importance is not immediately obvious.

Given its running time and that it was produced by someone best known for editing film trailers, The Foreigner might be dismissed out of hand on account of its lack of cinematic braggadocio, especially when compared to slick productions like Valve Corporation’s Dota 2 documentary, Free to Play (2013). But despite its brevity, The Foreigner provokes intense reflection on esports as a cultural phenomenon, as well as its histories, audiences, and place in culture at large. What’s more, The Foreigner is an object lesson in esports’ near-Oedipal obsession with being seen as ‘legitimate,’ the way that ‘real’ sports are. Freudian drama aside, what’s so crucial about The Foreigner is not simply that it confirms the importance of esports—hardly a radical claim in 2016. It’s that The Foreigner sheds light on the more challenging, but more rewarding, question of how and why esports has achieved its importance.

But it takes a long lens to see why. Though competitive videogame playing stretches back into the early 1970s—competitive Spacewar! (1962) was a counterculture favorite in the Bay Area—‘esports’ is a comparatively recent phenomenon. The term first appears in a 1999 press release announcing the ill-fated Online Gaming Association, an early (and naïve) attempt to establish a regulatory body for professional gaming. ‘Esports,’ in this sense, is distinct from the wider field of competitive gaming through the conscious emulation of professional sports, its institutions, and its conventions. As any baseball junkie will tell you, knowing the MLB rulebook isn’t even half of being a ‘baseball’ fan. ‘Baseball,’ the cultural entity, is simply incomplete without speculation over absurd contracts, shifting rivalries, jurisprudential misadventures in the off-season, franchise mythologies, and the pleasures/perils of increasingly outrageous stadium food. ‘Sports,’ in other words, is more than the sum of its games. It’s a culture, and should be analyzed as such.

So too with esports. If we really want to understand ‘esports’ as an institution, it’s therefore essential to consider all the practices and conventions that make up ‘esports’ beyond the rules of a particular game. Perhaps the surest sign of esports’ financial and cultural stability is the establishment of what might be called secondary industries. Massive prize pools and television broadcasts of esports have, in fact, been around since the mid 2000s: USA Networks began broadcasting professional Halo in 2006, while the 2005 Cyber Professional League boasted a $500,000 purse. What’s more telling about the esports of 2016 is the proliferation of esports production companies, online betting services, stat databases, strategy sites, and news outlets. ‘Homegrown’ versions of these have been around for at least a decade, but recent investments in esports by established companies with no prior interest in esports—including ESPN, The Score, Turner, etc.—are premised upon the stability and lasting success of esports.

‘Sports,’ in other words, is more than the sum of its games

Alongside and in relation to this story of spasmodic growth and contraction emerged the esports documentary. Tracing the history of these films, as it turns out, reveals a lot about the history of esports as a whole. As a general rule, esports documentaries have been released in three waves that correspond, roughly, with three moments of increasing visibility for esports: the mid 2000s, the early 2010s, and the present day. In 2005, for example, when esports began to connect with a wide audience outside of East Asia, National Geographic filmed a vaguely ethnographic documentary, StarCraft: World Cyber Games, at the titular tournament. Later that year, MTV profiled professional Super Smash Bros. Melee (2001) player Ken Hoang for its series True Life. In the early 2010s, as League of Legends (2009) and StarCraft II (2010) saw explosive growth in popularity (League viewership increased more than 700% between 2011 and 2012), a new cluster of documentaries were pushed out, many of which were funded by the up-and-coming crowdfunding platform of the time, Kickstarter. And, finally, since early 2015, many ‘mainstream’ outlets have been publishing a stream of documentaries ostensibly about the ‘sudden arrival’ of esports.

The Foreigner, which was officially released in 2015 but only recently became publicly available due to film award season schedules, belongs to the most recent wave of esports documentaries, but has its origins in that of the early 2010s. Sutak first conceived of what would eventually become The Foreigner when he noticed that YouTube videos of professional StarCraft II matches received hundreds of thousands of views within hours of being uploaded. Eager to get involved, but well-aware that playing competitively was out of the question, Sutak decided that he could put his talents as a filmmaker to use by documenting the growing Western scene. Such a film would capture a frenzied, nascent moment in the history of esports for future generations: “I felt I had a responsibility to frame [StarCraft II] in a compelling way—not just for the sake of art or entertainment, but as a historical document.”

Though Sutak originally envisioned making a feature-length documentary (a now-abandoned project called My Life for Aiur; its announcement is still visible on the popular StarCraft forum, TeamLiquid.net), he was ultimately dissuaded from doing so, in part, by the release of nearly a half-dozen longform documentaries about professional StarCraft II between 2011 and 2013. By and large, these documentaries, though well-intentioned, bear the telltale signs of projects with more directorial ambition than talent. The bloated Sons of StarCraft (2013) was meant to chronicle the career of the legendary casting duo, Nick ‘Tasteless’ Plott and Dan ‘Artosis’ Stemkoski, but is best remembered for the allegations of fraud and directorial mismanagement that plagued its production. Likewise, forum-turned-sponsor Team Liquid’s highly-anticipated Liquid Rising (2012) was billed as a comprehensive history of the organization, the ‘heart’ of Western StarCraft II, but ultimately took the form of a series of interviews with exactly zero narrative coherence; lots of words, with little sense of why they matter. Several documentaries from this period never yielded a finished product. Star Nation, intended to be a survey of StarCraft II in America, despite raising nearly $25,000 on Kickstarter, has never been released (and, presumably, never will be). Though there was no shortage of enthusiasm—and therefore crowdfunding—for documentaries about StarCraft II in the early 2010s, virtually every film produced fell flat on account of hasty production, overestimation of artistic ability, financial boondoggles, or some combination thereof.

By contrast, The Foreigner, a personal project pursued as a complement to Sutak’s more remunerative business of editing trailers, was unburdened by a pressure for quick release and the cries of impatient Kickstarter backers. Sutak also shows a judicious sense of directorial restraint that’s desperately lacking in so many other StarCraft documentaries. Though Sutak collected footage for The Foreigner at eight major tournaments, he ultimately scaled back his original, macroscopic intentions for the project in order to focus on a single, potent episode in the mythology of professional StarCraft II: MLG Columbus 2011, the first tournament in which South Korean players competed against ‘foreign’ (i.e. non-Korean) ones outside of Korea. The tournament is remembered as something of a Waterloo for ‘foreign’ StarCraft II. Though South Korea was the unquestioned champion of StarCraft: Brood War (1998), many in North America and Europe hoped that foreign players would rise to the level of Koreans in StarCraft II. MLG Columbus 2011, where the Koreans outclassed foreigners in every way imaginable, put an end to that. Since then, foreign players have won only a handful of premier tournaments (to wit, of the 20 winningest StarCraft II players, only one, Ilyes ‘Stephano’ Satouri, is not Korean).

virtually every film produced fell flat

Sutak examines MLG Columbus 2011 through the eyes of his titular foreigner, Greg Fields, known more widely by his nom de guerre, ‘IdrA.’ Even before his scandalous retirement from competitive play in 2013, IdrA’s tumultuous career was the stuff of legends. Briefly: after his 18th birthday, IdrA famously moved to South Korea to live and train with professional StarCraft: Brood War players. Though he experienced limited success in South Korea, he was, by a wide margin, the strongest foreigner in Brood War, which foreshadowed his initial success in StarCraft II. But what really captured fans’ imagination about IdrA was his notorious pugnacity, which elevated him from talented competitor to esports icon. IdrA eschewed the principles of good sportsmanship and professional decorum; handshakes were refused, opponents insulted, and keyboards smashed. Over time, IdrA’s antics overshadowed his achievements as a player, and he gained a reputation for being technically gifted, but emotionally vulnerable.

In the early days of StarCraft II, South Koreans rarely ventured beyond their border. Yet increasing competition in Korea, paired with the promise of tournaments abroad stocked with inferior players, meant that Korean pros quickly set their sights on world wide dominance. MLG Columbus was, officially, at least, the beachhead of the Korean invasion (née the Global StarCraft League – Major League Gaming Exchange Program) in North America. At the time, IdrA, then at the peak of his skill, was thought to be the only foreign player capable of halting its advance. The Foreigner picks up with a truncated version of this general story and follows IdrA as he works his way through the group stages of MLG Columbus and into the playoff bracket. Longtime fans of StarCraft II know what’s coming: the dramatic climax of The Foreigner constitutes one of the most notorious moments in StarCraft II history. In a crucial match against Mun ‘MMA’ Seong Won, IdrA inexplicably quits a game he had all but won. Sutak perfectly captures the moment through a series of reaction shots: MMA giggles in his booth, shocked by his good fortune; the casters’ jaws have, quite literally, dropped; the audience stares in silent disbelief, their illusion that foreigners would usurp their Korean overlords shattered. Then, Sutak turns the camera on IdrA himself, who simply stares into the screen with an expression of straight-faced inscrutability.

It’s a challenging moment to depict, but Sutak handles it with grace. For Sutak, the episode is reminiscent of Alan Sillitoe’s 1959 short story, ‘The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner,’ in which the protagonist, an inmate in a juvenile detention facility, is offered the chance to shorten his sentence by winning a long distance foot race organized by the wardens. Though he easily outruns his opponents, he deliberately stops short of the finish line as a declaration of his independence. The parallels to IdrA’s abdication in Columbus are obvious, but they raise a number of questions about the meaning of the abdications. Was IdrA’s forfeiture a gesture of vanity or hubris in the extreme? Perhaps he misread the battle and genuinely believed that he had lost. Were IdrA’s actions, like Smith’s refusal to submit to his captors’ contest, a kind of resistance to his commodification? Or maybe the pressure, that weight of Atlantean expectation that IdrA was asked to carry in Columbus, was too much to bear. In the delirious moments after IdrA quits, The Foreigner refuses to settle this ambiguity. A lesser director might have pestered IdrA for an explanation, but Sutak allows the viewer to draw their own conclusions about this curious vignette. As if to underscore this open-endedness, Sutak juxtaposes the credits over a close up of IdrA’s emotionless expression.

It’s a thoughtful close to a well-crafted film, which is in itself enough to secure The Foreigner the reputation of being the best StarCraft II documentary to date, even if the competition isn’t very stiff. But ‘good’ isn’t the same as ‘important,’ and The Foreigner is both. To think about why the film is important, it’s not enough to ask simply what it means, but also what it does. So while we could and probably should debate the ‘meaning’ of IdrA’s actions at MLG Columbus, and reflect on whether or not The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner is a useful precedent for coming to terms with this loss, it’s equally important for us to ask what effects The Foreigner has upon its subject, and upon its audiences.

In the delirious moments after IdrA quits, The Foreigner refuses to settle this ambiguity

In 1987, the film theorist Bill Nichols wrote that the documentary is, all at once, “a filmmaking practice, a cinematic tradition, and a mode of audience reception.” There are many potential effects for a successful documentary—it can praise, criticize, or raise awareness in a general sense—but, in one way or another, documentaries lend an air of ‘legitimacy’ to their subjects. One way of interpreting the surprisingly large number of esports documentaries is that esports communities desperately want to be seen as legitimate, and, as a result, were eager to bankroll just about any attempt at making a documentary. The logic here is that every documentary, by virtue of its existence, establishes its subject as ‘worthy’ of documentation. The inverse holds true as well: documentaries are legitimated by their subjects, the perceived worth of which justifies the documentary itself.

It’s a strange, symbiotic relationship, but it would be a mistake to assume that the correspondence between a documentary and its subject is either simple, transparent, or automatic. Words like ‘legitimate’ always smuggle with them the thorny, unsaid question ‘legitimate to whom?’ Such judgements must be situated in the context of a particular audience. The viewer, philosophy of aesthetics be damned, is never an abstract ideal but a particular human being who belongs to particular communities, and consumes media through the lens of a preexisting set of interests and biases. Identity is not something we think ‘about’ so much it is something we think ‘with.’ To understand how and why esports documentaries, from MTV True Life to The Foreigner, do or don’t legitimize ‘esports’, it’s essential to examine these films’ intended audiences and the modes of address they employ to engage those audiences.

A still from the 1962 film version of The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner

At its heart, this is a question of what counts as being ‘in’ and ‘out’ of esports. Making these assumptions implicitly constructs a knowledge-boundary about what esports fans know, and what those not interested in esports presumably don’t know. What’s useful about uncovering this boundary is that it allows us to imagine the audience for esports as something more nuanced than a growing horde of unspecified individuals. Instead, we can see how specific documentaries address (or not) particular audiences by unpacking the assumptions a film makes about what the viewer does or doesn’t know. Two intransigent formal conventions of esports documentaries are particularly telling: one, the manner in which a documentary introduces ‘esports’ as a whole, and, two, how a documentary explains the mechanics of whatever game is being featured.

On the first point, many documentaries about esports devote the first few minutes of their running time to a general introduction to esports as a whole. Typically, this includes long shots of stadiums bathed in dark light, slow pans over cheering crowds, infographics of exponentially growing esports prize pools or viewership, all carefully selected and arranged to convince the viewer that esports is serious business. Unsurprisingly, this kind of exposition-as-justification generally indicates that the intended audience is not one already familiar with esports (i.e. ‘outside’ esports). Why else would these viewers need to be convinced that the documentary is worth their time? ESPN’s short documentary Throne of Games, which examines the North American Dota 2 team’s victory at The International 5, the largest esports tournament in history, is a prime example. Advertised as “an unprecedented look into the world of professional video games,” the film draws upon familiar narrative contours—young men whose parents don’t approve of their passions but go on to win absurd amounts of money—and visual motifs—Evil Geniuses walks onto the stage of Seattle’s KeyArena through a haze of photogenic fog—to persuade skeptical viewers that esports might be worth their time (and, to connect esports to ESPN’s more traditional program; ESPN launched its own esports division only a few months after broadcasting Throne of Games).

this is a question of what counts as being ‘in’ and ‘out’ of esports

Often, documentaries of this sort represent a kind of double-edged sword for esports. Attempts at introducing esports to viewers who aren’t aware of or amenable to its existence often end up reinforcing esports’ alterity. Esports, in this sense, is presented as a curious spectacle, possibly admirable, possibly lamentable, but definitely different. Especially in the first wave of esports documentaries (~2005-2007), the exposition portion of esports documentaries evinces a tone of bemused novelty, if not outright condescension. The entire premise of the MTV True Life profile of Ken Hoang et al, of course, is that playing videogames for a career is too absurd to be ‘true life.’ In all cases, the documentarian is thus established as an outsider looking in—what Sutak would call a ‘documentary about esports.’ As a result, the boundary between what’s ‘in’ and what’s ‘out’ is made more, not less, rigid.

The other telling convention is the degree to which an esports documentary explains the mechanics of whatever game is being played, a task that’s easier in some cases than others. StarCraft, in which battles are fought by color-coded armies and follow the general principle of ‘the side with the biggest army is ahead,’ is surprisingly legible for the uninitiated. When a fortification of siege tanks and marines is overrun by a swarm of insectoids, it’s obvious which faction is winning. Likewise, most fighting games—Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat, Super Smash Bros., etc.—place a relatively low burden of knowledge on the viewer. The subtleties of a bout might escape neophytes, but it’s clear that the character getting their ass beat is losing. By contrast, the cataclysmic, frenetic teamfights of Dota 2 and League of Legends are nigh-unintelligible to unseasoned viewers. So impenetrable is Dota 2 to newcomers that, at Dota 2’s premiere tournament, The International, Valve sponsors a stream dedicated solely to a cast directed at those not familiar with the game and its mechanics.

Traditionally, whether or not a documentary feels the need to explain the basics of a given esport says a lot about who the documentary assumes its audience is. Valve’s Free to Play, for example, devotes nearly 10 minutes—a significant investment of time for a film that’s barely longer than an hour—to an explanation of the basics of Dota 2’s ruleset to viewers. Throughout the lesson, Dota 2 personalities make repeated allusions to widely-known reference points (e.g. “Dota 2 is played five on five, like basketball”), leaving little doubt that Free to Play is as much intended for audiences who don’t play Dota 2 as much as it is for those who do. In this respect, Free to Play is a particularly well-made advertisement for Dota 2. This doesn’t necessarily undercut its artistic value, but it does speak to its authors’ intentions.

documentaries of this sort represent a kind of double-edged sword for esports

There are, of course, other telling signs about address and audience. One of the most famous esports documentaries is The Smash Brothers (2013), the Super Smash Bros Melee community’s love letter addressed to itself. Produced on a budget of $12,000 raised through Kickstarter, the documentary’s production coincided with professional Melee’s long winter, when prize pools dried up and most of the first wave of professional players retired in obscurity. As a result, an eulogistic air infuses much of the film. What The Smash Brothers lacks in production value it more than makes up for in its spirit. Still, at a cumbersome four hours and 18 minutes, it’s hard to imagine anyone without a preexisting interest in Super Smash Bros. committing to a complete viewing. Likewise, the crass language of the players wouldn’t alarm many of those in the late 2000s Super Smash Bros. scene, but would do little to endear the game and its culture to someone who wasn’t at least familiar with the community’s discursive conventions. The point isn’t to be judgemental, but to note that a documentary truly intended for a wide audience would have, firstly, been much shorter and, secondly, selectively edited some players’ coarser comments, especially the frequent allusions to ‘raping’ their opponents.

The Foreigner, though, is an outlier among esports documentary films in that, excepting some quotes made in passing, it devotes almost none of its running time either to introducing esports in general or explaining what transpires in a game of StarCraft II. Does this mean that Sutak is operating on the assumption that his viewers are familiar with esports? Not quite. Sutak includes many shots of in-game footage—flocks of Mutalisks tearing through a cluster of prefab buildings, marines being swarmed by goo-spewing Banelings etc.—but he seems distinctly less interested in their narrative value than in the kinetic sense of action they convey. Someone familiar with IdrA’s series against MMA might in fact recognize some specific moments (including MMA’s infamous and unintentional destruction of his own Command Center), but even a viewer with no knowledge of StarCraft II can appreciate these shots’ aesthetic value; paired with quick cuts, they lend The Foreigner a frenzied pacing that mirrors what a seasoned StarCraft II viewer gets from watching a competitive match. There is, in short, something—but something different—for both kinds of audiences, which presents a certain difficulty for the question of address, and, by extension, Sutak’s own distinction between esports documentaries and documentaries about esports.

A still from The Smash Brothers

Likewise, Sutak trusts that viewers need not see an infographic about prize pools and viewership to recognize the human story that animates The Foreigner. At the same time, MLG Columbus 2011 represents something very specific to fans of StarCraft II; it was a bright point in the game’s early arcadian history that made palpable the dream of esports as something other than a subcultural curiosity. Amid the broadcasts, the neon lights, the screams, the cheers, the sponsors, and, most of all, the thought that we foreigners might beat the Koreans at their own game, there was an electric sense that something about esports had changed irreparably. Unlike the junkyard of unrealized dreams in our collective past, this time, esports was here to stay. Sutak was there, and so I’m sure he witnessed this, but that’s not the same as knowing if he felt it—on that count, I have no idea. But this multiform feeling pervaded every attendee of MLG Columbus, who hung on StarCraft II their hopes for a future for (and of) esports. I should know; I was watching too.

For a moment, let me drop the dispassionate tone of a critic and speak as someone who has loved esports for a decade and is now a part of the industry, largely because of StarCraft II’s success. There’s no point in pretending I don’t have a stake in esports; in fact, for four years, I’ve worked with the same organization that sponsored IdrA at MLG Columbus, Evil Geniuses. I am, in short, anything but an impartial observer (so consider this my disclaimer and disclosure). Like Sutak, and like IdrA, I began playing StarCraft in the early 2000s, and was both amazed and excited when I one day discovered that, on the other side of the world, some people did this for a living. As a consequence, StarCraft II, for me and for so many others, bore an unbearable weight of expectation. At long last, esports would take root in the West! A myopic perspective in retrospect, but sincerely held all the same. And so when StarCraft II was finally released in July of 2010 following a tortuous, prolonged development, I devoted to it a sum of hours so great I am embarrassed to reveal it.

With The Foreigner, Sutak found a human story—and a form to match it

In fact, it was over 2,000 hours, plus many more spent watching player streams, tournaments, and updating esports’ largest wiki, Liquipedia. When later I received the opportunity to work in esports, I seized it not simply because I wanted to be part of an emerging industry, but to prove to myself that all those hours had not been wasted. What I wanted, in other words, was for esports as an ‘institution’ to legitimize my passion to myself. But the truth about passions is that they do not require justification. Indeed, they cannot be justified—if they could be, why would we call them passions? When we construct elaborate, productive justifications for our passions, haven’t we surely missed the point? And this is, I propose, the strange paradox of legitimation: it is achieved at the exact moment we no longer feel the need to achieve it. This is, after all, the humor of the meme “We demand to be taken seriously”: anyone who demands to be taken seriously should under no circumstances be taken seriously. True legitimation involves seamless integration into the textures of everyday life.

This has been true for me, and, in my mind, it’s true for esports as a whole, which is what makes The Foreigner such a significant film, probably without trying to be. But, in a sense, isn’t that the point? With The Foreigner, Sutak found a human story—and a form to match it—that could speak to anyone willing to listen, be they a lover of esports or not. While ‘outsider’ directors have seen meaningful narratives in esports many times before, they were inevitably possessed by a need to frame those stories in an argument about the legitimacy of those stories (see: Throne of Games). What’s so important about The Foreigner is that although it was purportedly filmed from the ‘outside’ of esports, it displays no evidence of a compulsion to justify its subject. The worth of esports, like its legitimacy, is taken as axiomatic.

Likewise, Sutak uses familiar conventions, storylines, and archetypes to emphasize his subject’s commonality, not difference, with sports and culture as a whole. The point is not that esports have become like sports (or that sports have become like esports), but that they are becoming like each other. As it turns out, the solution to the perennial desire for ‘legitimacy’ was not to move the ‘inside’ of esports outwards, or to bring the ‘outside’ ‘in.’ Rather, it’s to avoid the temptation to make that distinction entirely, to refuse the Faustian bargain that simultaneously blesses esports with visibility and curses it with alterity. This, in my mind, is a genuine triumph, and, for now at least, The Foreigner is unique among esports documentaries in making this point about esports. So perhaps it’s unsurprising that Sutak has been well-rewarded for The Foreigner: it is the first film about esports to win any significant award from the discerning film festivals of the world, being named ‘Best Short Documentary’ at both the Las Vegas Film Festival and Los Angeles New Wave International Film Festival.

In the conclusion to his book How to Do Things With Videogames, Ian Bogost wonders aloud about the supposed and imminent end of ‘gamer’ as a useful identity. As he writes, ‘as videogames broaden in appeal, being a “gamer” will actually become less common, if being a gamer means consuming games as one’s primary media diet or identifying with videogames as part of a primary part of one’s identity.’ If we’re fortunate, Bogost says, the identity will dissolve altogether, simply melting into ‘people’ and ‘culture.’ The Foreigner is, perhaps, the best evidence we have that the beginnings of such a shift is now underway for esports. There will be more esports documentaries, and no doubt that some will still treat esports as a spectacle of digital difference. The better ones won’t, and indeed, will explore what happens when esports is no longer an oddity but the norm. In an age where commerce means e-commerce and dating means online dating, we shouldn’t be surprised that the difference between esports culture, sports culture, and culture as such is wearing very thin indeed. Dissolution is grace.

March 30, 2016

Cartas captures the terror of immigration in the 19th century

Julian Palacios, the Milan-based creator of Cartas, describes it as being “a short narrative game about the journey of a man adrift.” It is, in fact, more specific than that, it being bookended by letters written by immigrants who traveled to Argentina at the end of the 19th century. The game seems most concerned with depicting the dysphoria and disappointment of immigration, particularly as it’s described in the letter that is read aloud at its beginning—that of open hostility, constant alienation, racial abuse, feeling alone in an unfamiliar land. It captures all this through abstract, dreamlike segments that see you passing through the geometry of the game’s virtual scenes, pushed into the black voidscape beyond, where you become utterly lost.

Then it all comes crashing down

The presence of the void is dominant from the start. You see a square cut-out in front of you, surrounded by the total blackness, and inside this square is shown a cartwheel as it spins across gravelly terrain. You cannot move but you can look around during this scene. However, be that almost the only thing you can see is total blackness, your main informational stimulant is the sound of the horse-pulled cart coming from the cut-out. The set-up implies a bigger world than you are able to see, as if you have blinders on, but are still able to imagine the visuals you’re missing due to being fed sound cues. In total, it feels like the start of a hopeful journey, almost relaxed, like you were lazing atop the cart and riding toward a better future.

Then it all comes crashing down. For several minutes during this first scene, a voiceover reads the first immigrant’s letter to you over the sound of the cart and the clip-clop of the horse’s hooves. The letter is written by an Austrian called Jose Wanza, who sought a better life in Buenos Aires but ended up being treated like a slave—more on that here—and so any positive vibes the scene has are steadily dashed as you learn of his misery. When the voiceover finishes reading Wanza’s letter, the cut-out of the cartwheel suddenly expands to surround you with a full 3D world. It’s an astonishing transition. The cart you were looking at now appears empty and is without a horse. It loses momentum and rolls to a slow stop amid an empty natural expanse. There’s nothing here, nowhere to go, and you’re absolutely alone. It’s akin to waking up from a beautiful dream to find yourself in a grimmer reality.

This is only the start of the game’s brief journey. From this dull meadow that the cart sits within the void gradually absorbs you, expanding in presence with each new scene. The next one sees you stood on a dock at night, watching as a large ship comes in from the sea. It seems unsuspecting until the ship pulls in closer and you notice that it hasn’t slowed down at all, it heading right at you with a dangerous velocity. Unable to escape, the huge ship pushes you aside, and as its width swallows the dock it pushes you through the stone walls and into the voidscape behind them. This is where you fall eternally into the blackness.

this land is a vacant construct for them where no home can be made

But you don’t. A transition to another scene pulls you out of your indefinite descent, but the void is no less consuming. You find yourself in the middle of what could be a city. The only signs of this are the tall townhouses that sit separate from each other inside the voidscape. You travel to each of them, not knowing where to go, what to do, but discover that you can press ‘E’ when close enough to the jagged walls. Doing this causes them each building to vanish but adds the sound of a barking dog to the mix. The dog is unfriendly, aggressive, a signifier for the unwelcome gesture that immigrants like Wanza experienced. Eventually, you’re left with no structure, only the sounds of angry dogs and an all-consuming nothingness; lost and scared. Another scene after this one sees you in the crow’s nest of a large ship as it approaches a mountain from the sea and eventually moves through it. It reiterates the idea that the immigrant cannot truly dock on foreign land, that this land is a vacant construct for them where no home can be made.

The ending of Cartas seems to switch everything around, or at least aim to be more hopeful. A second letter is read aloud (it’s actually two letters jumbled into one) over the top of reversed footage of workers leaving the Lumière brothers’ factories. The writer of the letter is happy that they emigrated as they found work and are treated well, finding themselves in a more forward-thinking and polite society. It’s a note that’s at odds with the rest of Cartas but perhaps one that exists to better acknowledge the spectrum of the immigrant’s experience, and a reminder of why people thought it a good idea in the first place. But it leaves you wondering about the honesty of this letter given that it’s written from an immigrant back to their loved ones at home—they wouldn’t want to worry them. Or if the prosperity this particular immigrant is experiencing is true, whether or not it has a timer on it before they, too, feel alienated as the void creeps its way in.

You can download Cartas over on itch.io.

Glaciers writes poetry using Google’s most popular searches

Currently wrapping up its first weekend on display at New York’s Postmasters art gallery, Glaciers is the latest art project from Sage Solitaire (2015) creator and Tharsis systems designer Zach Gage, as well as several billion unknowing co-authors. The exhibit features a collection of small e-ink screens, each displaying a digital poem generated using the top three Google autocomplete results to a specific prompt, such as “how much,” “does he want,” and “should I save.” The poems refresh once per day, meaning that like their namesake, they have the potential to change shape and meaning over time.

Though Gage is well known for his work in game design, he also has a long background as a digital artist, Glaciers being the most recent in a series of projects which focus on the questions people ask each other online. While visiting Glaciers’ opening day this past Friday, I sat down with Gage to ask him about his goals with the project. “When we build these giant systems [like Google or Twitter] on the internet,” he told me, “they amass a lot of data.” But while it might be easy to pull statistics from search engines and social media platforms, he explained, “that data is very difficult to interrogate in a meaningful way.” With Glaciers, he’s hoping to transform this data into an art piece that visitors can appreciate on a personal level.

Gage had previously approached this concept in his 2009 project Best Day Ever, which is also on display alongside Glaciers. Similar to Glaciers, Best Day Ever searches Twitter for a specific phrase—in this case, “best day ever”—and then uses an algorithm to pick one of the resulting tweets to display on its LED screen. “Early on, with Best Day Ever, I keyed into the idea that if you’re very careful with your searches, and you’re very careful about the context that your searches are presented in,” he explained, “you can make components of these large systems very meaningful to people.”

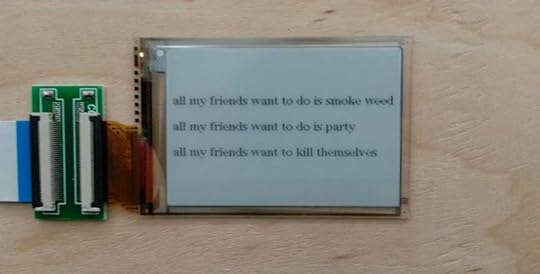

This mirrored my own experience seeing Glaciers for the first time. As I inspected each of the poems lining the gallery’s walls, I was surprised by how coherent they were, given that they written using unrelated Google searches. The poem for “is it scary,” for instance, read “is it scary to die, is it scary to fly, is it scary to skydive,” leading the reader along a single train of thought. Meanwhile, the poem for “all my friends want to” came across like a frustrated plea from a puritanical friend, reading “all my friends want to do is smoke weed, all my friends want to do is party, all my friends want to kill themselves.” Surprised by how laser-focused these unintended messages were, I asked Gage how he chose the prompts for Glaciers.

“data is very difficult to interrogate in a meaningful way.”

“Because I’ve been doing these human query things for a long time, I’ve gotten a little adept at trying to find prompts and making sure things were meaningful,” he answered. “I wanted stuff that made nice poems, were representative of the system [Google], and that I could rely upon to be interesting in the future.” I asked if any of the autocompletes he found while working on the project surprised him. “I think all of them surprised me. If they didn’t surprise me, I didn’t want to put them in the exhibit.”

As Glaciers is on display at a gallery rather than a museum, each poem is also available for sale, which Gage told me actually works into the project’s meaning. “Digital art is traditionally very momentary,” he said, saying that it often involves interacting with a piece for a minute or so and then walking away and thinking about it. “Whereas a lot of more traditional art is very passive,” he continued, explaining that when a patron buys a painting, while they may interact with it once in a while, it usually simply sits in the background of their life and becomes part of their daily experience. “So I was interested in trying to come up with a way that I could make digital art be this thing that you just pass and is part of you and becomes this monumental kind of experience.” At the same time, however, because the poem is connected to Google and will change along with it, Gage was also hoping to “be very true to its digital nature and have it be changing and really about this changing world.”

As I further explored the exhibit and noticed how deeply personal some of the poems were, frequently making mention of sexual or financial failure, I started to think about Google’s nature as an anonymous service. Because users don’t have to be embarrassed when asking it questions, it’s able to see people at their most vulnerable, making it a great way to track the anxiety of a culture over time. As Gage explained, “These are games being played by billions of people who don’t really know that they’re playing them.” The poems in Glaciers, like their real-world counterpart, have more going on under the surface than one might initially assume.

You can experience Glaciers for yourself at Postmasters Gallery in New York, running through May 7th. For more of Gage’s work, visit his website.

The hacker pulling off SNES glitches that only machines were supposed to do

We’re at a time when artificial intelligence is not only mimicking human behavior but surpassing it. The common story now is one of a previously human-exclusive activity—usually labor or a sport—being performed better by a machine programmed to perfect it. That’s why it might feel like we’re on the verge of everything tipping into the robots’ favor: the many technological warnings of science-fiction coming true (Skynet in 1984’s The Terminator, etc). Perhaps this is why Seth Bling does what he does. He’s something of a videogame engineer and hacker who, among other things, specializes in completing tasks that only machines were thought capable of doing.

he can alter the game while playing it

A year ago, he became the first human to pull off the “Credits Warp” in Super Mario World (1990) on a SNES console—”a glitch which plays the end credits without actually defeating Bowser.” What’s remarkable about this glitch is that it involves rewriting the game’s code from inside the game itself. By putting certain objects within pixel-precise locations inside a level, Bling is able to write binary code into parts of the RAM. What this means is he can alter the game while playing it, without any of the tools usually required to do so, as if he had direct access to the lines of code that form the game (and he kinda does). You don’t really need to understand why this is possible or how exactly it works (although there is a technical breakdown here), just know that it can be done.

It’s this discovery, originally made by Jeffw356, that set the pace for another exploit in Super Mario World that Bling pulled off on March 27th. This time, he altered the system RAM so that Super Mario World ran the code for the 2014 mobile game hit Flappy Bird. As Bling explains in the video, this has been done before by feeding pre-recorded controller inputs into the game through a computer, but he has now done it without that assistance, becoming the first human to ever do it on an unmodded SNES console.

To pull it off, Bling had to use a series of glitches to manually inject 331 bytes of processor instructions, which corresponded to the Flappy Bird source code. This involved having to line Mario up to 331 precise co-ordinates inside the game world that corresponded to memory locations. All of these co-ordinates had to be spot on otherwise the game would crash or Bling would have to restart that section of code over. All of this was made possible after months of work, a lot of it done by SNES hacker p4plus2, who wrote the assembly code that basically made it all possible. And it all came to fruition a couple of days ago; a human using a complicated set of glitches to inject a game inside of another one.

You can get the full explanation of how this SNES code injection works in these public documents or you can watch the full video for a showcase of it in action.

Umberto Eco and his legacy in open-world games

At the very end of his playful Postscript to The Name of the Rose (1980), Umberto Eco made a casually sibylline gesture toward the future of interactive fiction. “It seems,” Eco wrote, “that the Parisian Oulipo group has recently constructed a matrix of all possible murder-story situations and has found that there is still to be written a book in which the murderer is the reader.” And a few lines later, with a wink: “Any true detection should reveal that we are the guilty party.” The text either ends or begins here, depending on your interpretation.

OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle) was a collective of experimental French writers and mathematicians who, in the 1960s, developed a new form of “potential literature,” where the imposition of arbitrary rules became a constitutive part of the work’s meaning. George Perec’s La Disparition (1969), for example, was a 300-page novel written without the letter “e.” The characters in the novel search for the missing letter, but can’t actually use it for fear of fatally injuring themselves. Meanwhile, Raymond Queneau’s A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems (1961) offered just that: 10 sonnets printed on separable lines of text that could be individually turned at will, producing 100,000,000,000,000 different poems for the reader’s pleasure. In adapting the aleatory (or chance-based) methods of composers like John Cage to the more nebulous domain of literary meaning, writers like Queneau updated the classical conventions of literature for a civilization riven by the conflict between freedom and order in unprecedented ways.

Although much of his work as a philosopher was devoted to explaining how such experiments were linguistically possible, Eco never set these constraints on his own fiction. Instead, he played other kinds of games. In his 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum, Eco had three men feed an unwieldy amount of esoteric trivia—involving Templars, Rosicrucians, Freemasons, Illuminati, and a thousand other occult sects—into a computer that synthesizes them at random to generate a master “Plan” explaining the course of European history. Tension rises as, over time, the three start to believe in their own Plan. Reality and fiction bleed together: “the game,” he writes, “was no longer a game.” Tragic consequences ensue, but it seems that the moral of the story didn’t stick: Eco would joke a few decades later that one of the uncredited characters in Foucault’s Pendulum was The Da Vinci Code (2003) author Dan Brown.

The Name of the Rose was built around a similar twist of interpretation. A monk detective hypothesizes that a series of unconnected murders in an abbey are being inspired by the events of the Seven Days of Revelation. But when he voices this erroneous theory, another monk is inspired to see the pattern through to its bloody end. This marks a common theme in both Eco’s fiction and his philosophical work: our interpretations of the world are necessary tools for making sense of it, but fixing onto these beliefs as if they revealed the true nature of things can be dangerous. The world is always more chaotic than the order our closed systems of signs impose.

The world is always more chaotic than the order our closed systems of signs impose

From this angle, the playfulness of Eco’s fiction served a serious purpose. The author was notorious for stuffing his novels with an endless series of digressions, side quests, ephemera, arcane debates, and insane lists of every variety. (Eco once wrote that “we like lists because we don’t want to die.”) But in offering so many points of potential diversion and avenues of further learning for the curious reader, Eco, who grew up under the shadow of Mussolini, was waging as fierce a battle for artistic and intellectual liberty as the most radical of the French avant-gardists. Without sacrificing his natural gift for telling a great story, he ensured that his own text remained an open work, thereby preserving a space of possibility for an open world.

///

When Eco died from cancer in February, it felt like a grim period on the printed word’s death sentence. It is almost impossible to imagine a novel like The Name of the Rose selling 50 million copies in 2016. True, its appeal has been enduring enough over the years to inspire two Spanish videogames, a board game, and the curious idea that Christian Slater could pass as a German monk. But Eco never sanctioned any of these. He always insisted on the autonomy of literature, even as he was helping to change the idea of what literature could be. And it is doubtful that his fiction had the same kind of influence on the aesthetics of games that Philip K. Dick or William Gibson’s arguably did.

But in his work as a philosopher and cultural critic, Eco helped to create a world where feeding coded information into a user-controlled computer could produce something like art. Decades before his ascent to literary fame, he insisted on the necessity of breaking down the distinction between “high” and “low” culture, treating both as equally significant objects of analysis. Thus one might find, in any given essay, allusions to Thomas Aquinas, Ferdinand de Saussure, and Bach stacked up against intricate meditations on Disneyland and James Bond. This kind of polymathy was not just an opportunity for Eco to show off his unmatched erudition; it was a natural development of his theoretical conviction that, since all meaning arises from the interaction between structures of symbols, the true distinction between high and low culture is dictated by taste, not form.

Eco’s work in semiotics—a field he didn’t invent, but which he had largely sustained since the 1980s—was devoted to classifying and evaluating the forms of these symbolic structures. This work could be as dauntingly technical as that of any of the Medieval thinkers Eco loved, but the core idea is simple. Think of language: On their own, the 26 letters of the alphabet are just empty shapes with no meaning. But when we combine them into larger structures (words and sentences) according to fixed rules (of grammar), we end up with meaningful speech and successful communication. Semiotics takes this basic picture and applies it to everything in the human world—soccer matches, marriage customs, advertising. The world is an unfinished text waiting to be interpreted.

The revolutionary effect of combining these ideas is that the creation of artistic meaning becomes as natural to human beings as the ability to use language. As Cage and Queneau already intuited, we no longer need restrict ourselves to the classic aesthetic scenario of a God-like author imparting profound meanings through knowledge and techniques available only to her. We have, instead, the possibility of a democratic artwork where spectators become participants. A work where you can be the murderer and the detective.

The world is an unfinished text waiting to be interpreted

It would be hard to overstate the importance of this shift for the development of open-world videogames. Whether the signs in question are pixelated manticores and ogres or the skyscrapers of a post-apocalyptic Boston, what distinguishes these games is that they allow for a recursive determination of the game’s own structures by the player. (Note that I am not distinguishing here between open world and “sandbox” games.) Every game necessarily gives the player some element of choice, even if it is only “Push A to proceed.” But open games give us choices about what kinds of choices we can make—they don’t give us a world of possibilities, they give us millions of possible worlds. The enjoyment doesn’t come from the number of options, but from seeing one’s authorial identity become manifest in a creation that remains larger than oneself.

Of course, not every collaboration is going to produce a great story. If one believes, as Eco did, that it should still be possible to distinguish “trash” from true art within interactive fiction, how do we know the difference? We can tease an answer out of Eco’s distinction between code and labyrinth. A code, in Eco’s sense, is the set of conventions that make it possible for a sender’s message to be understood by the receiver in an act of communication. My writing this paragraph presumes that you can read English, that you can operate a computer, and so on. Codes set a particular context for exchanges of information, eliminating ambiguity. Labyrinths, by contrast, are situations of irreducible ambiguity that arise from violations of convention. Codes make us stop at red lights and allow us to tell the time. Mulholland Drive (2001) beckons us into a labyrinth. Eco’s conviction is that art should actively struggle to defer and delay conventional meaning-fulfillments in order to restore our sense of the essential strangeness of the world.

A still from David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive

The ambiguity of open-world games is typically not, however, a symbolic one. Instead, it’s what can only be called an ontological ambiguity: which history will transpire? What virtual events will be actualized? Which soldiers will take an arrow in the knee? As you create your world, one omnipotent decree at a time, signs in that world begin to take on their own meaning as a part of the larger whole. But actually doing this involves navigating an endless series of deferrals and delays. As you progressively assemble your own labyrinth, where every point is connected to every other point, you create so many interlinked zones of expression to give the programmed codes a context.

Fans of open-world games already know that getting sidetracked is the point. But the best of these games, perhaps, are those where the secondary quests are as meaningful as the main plot, and where all of the different threads of the story can be woven together to form what Eco called “controlled disorder,” or an “organic fusion of multiple elements.” The success of The Witcher 3 last year seems largely attributable to its achievement of this precarious balance. This may have something to do with the game’s novelistic origins, but the real credit goes to the creators. Chris Breault put it well in his review for Kill Screen last year: “In almost every side-quest and monster-hunting contract you undertake, there are telltale signs of someone at CD Projekt Red actually giving a shit.”

getting sidetracked is the point

In this light, perhaps we shouldn’t be too quick to celebrate the vaunted death of the author. It may be true that the modern work should be open, but to be art, it still needs the artists on the other side of the screen. And we need artists because our stories aren’t always our own. If they were, we would outlive their telling.

This seems to be what Eco wanted to convey when, in a 2003 talk on “The Future of Books,” he touched on the possibilities opened up by new forms of narrative media. This address seems endearingly outdated now, both for its dial-up era dialect and perhaps naive belief in the persistence of printed fiction. But with its playfully irreverent mashup of classic literary heavyweights and modern short-order entertainment, it is classic Eco. As a summation of the stakes of interactive fiction, it is perfect. And as an unwitting epitaph for this most bookish of authors, it is unexpectedly moving:

If you had War and Peace on a hypertextual and interactive CD-ROM, you could rewrite your own story according to your desires; you could invent innumerable War and Peaces, where Pierre Besuchov succeeds in killing Napoleon, or, according to your penchants, Napoleon definitely defeats General Kutusov. What freedom, what excitement! Every Bouvard or Pécuchet could become a Flaubert!

Alas, with an already written book, whose fate is determined by repressive, authorial decision, we cannot do this. We are obliged to accept fate and to realize that we are unable to change destiny. A hypertextual and interactive novel allows us to practice freedom and creativity, and I hope that such inventive activity will be implemented in the schools of the future. However, the already and definitely written novel War and Peace does not confront us with the unlimited possibilities of our imagination, but with the severe laws governing life and death.

March 29, 2016

Cat++ turns our feline obsession into a coding language

Cat++ is a code developed by Nora O’ Murchú, an Irish new media art curator, designer, and academic. Oh, and a cat lover, of course. Created during a residency at Access Space in the UK, Cat++ is thought of as a one-of-a-kind “cat simulator.” The coding alternates cat interactions with random and uncontrollable events that are translated through a series of 8-bit-esque animations. The code is based on real cat characteristics and assigns different dynamic visuals to user input. What’s even more wonderful is that O’ Murchú invites others to expand on the code with more cats and behaviors for new and unexpected interactions.

cat behavior is being taken more seriously by more and more people

Cats have had a lengthy and high profile relationship with the internet. Often considered frivolous, our obsession with cats has garnered the attention of scientists, academics, and critics for serious analysis. Now, even Wikipedia highlights its complexities, and different findings in great detail. You can easily find listicles that detail our complex psychological relationship with cats too. It is also seen as having great historical value, as we can see from the Museum of the Moving Image exhibition last year titled: How Cats Took Over The Internet.

Although the conversations about cats and the internet have been numerous, this conversation is now broadening in relation to other digital forms. As we see with the rise of things like Neko Atsume, cat behavior, too, is being taken more seriously by more and more people. This is contrasted with our internet interaction with cats, which tends to be more passive, through the watching of cat videos, or human centric, through the creation of memes. O’ Murchú’s work with Cat++ can be seen as an extension of this newer approach.

However, beyond taking cat behavior more seriously, O’ Murchú is also interested in the importance of diversifying coding languages in ways which speak to our different needs and interests. “Developing new uses for code as a medium for aesthetic or political expression allows for the dissemination and development of new understandings of the use and influence of code beyond technical domains.”, O’ Murchú told The Creators Project.

This is not only an issue of broadening the appeal and accessibility of coding, but also of examining the intersection between creativity, technology, and theory. O’ Murchú points to the School for Poetic Computation as a massive point of inspiration, because of the emphasis they place on both research and practice, allowing people the space to learn and think more critically about the technology they are engaging with.

Cat++ reminds us that fun and seriousness are by no means mutually exclusive traits. It’s a step further in us digitally exploring and expanding our relationship with cats. More than that, though, innovative conversations started by such projects will hopefully allow coding, and the digital, to grow in ways which are both accessible and interesting to those new (and old) to the medium.

Be sure to keep track of Nora O’ Murchú’s projects via Twitter and to check out Cat++ on GitHub

Pokémon GO will encourage players to visit museums and art installations

As a series that has been primarily confined to handhelds since its inception, Pokémon has always encouraged a certain amount of “go” from its audience. For instance, its commercials frequently feature players wandering through forests and cityscapes, getting to know their hometowns better and meeting new friends along the way. Yet, as much as these games want me to take them to the park or the museum and collaborate with others, I’ve mostly always played them by myself while huddled around a power outlet in my bedroom. And given consistent cries from fans for a main series Pokémon game to be released on a home console, I’m guessing I’m not alone here. However, according to a new official post on alternate reality smartphone game Pokémon GO, it seems as if those looking to catch ’em all will have no choice this time but to go outside and experience some damn culture, finally fulfilling the vision Nintendo promised in those ads all those years ago.

The post explains that to catch Pokémon in the game, players will first need to visit PokéStops, which can be found at public art installations, historical markers, local monuments, and other places of interest. There, they can acquire Poké Balls and then set out to capture their target Pokémon, which they can only find by going to its real-world habitat. Meaning that if you want to catch a water Pokémon, you better pack some sunblock, ‘cuz you’re going to the lake. At this point, all players need to do is start exploring and wait for their phone to vibrate, indicating a nearby Pokémon which they can then catch by using their touchscreen to toss a Poké Ball at it. Because of the lack of battles involved in the capture process, it almost seems as if the goal here is more to get you visiting places of interest (read: culture and natural beauty) than anything else.

not every Pokémon GO player is going to live in an 8 million person metropolis

Which is not to say that battles aren’t in the game. For those who don’t want to go on an endless series of field trips, there’s also the option to set up and challenge gyms. At a certain point in the game, players will be offered the chance to join one of three teams, at which point they’ll be able to work together to claim certain real-world locations as gyms. By setting down a Pokémon at an empty gym, a player will claim it for their team. The more players who set down a Pokémon, the stronger the gym’s defense will be. Then, to claim that gym, opposing teams will need to take out all defending Pokémon first. Because if kids are going to fight over territory, they might as well do it with fire-breathing dragons.

Living in New York, I’m sure I’ll be able to find plenty of PokéStops, and some may even lead me to a new favorite spot or hobby I might have otherwise missed. The potential problem with this system is that not every Pokémon GO player is going to live in an 8 million person metropolis. For those living in more rural or economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, public art installations and local monuments might be difficult to find, and traveling to lakes might not be feasible. Whether or not Nintendo has taken this into consideration will become more clear as the company launches early user tests in Japan to test the game’s technology. As it stands, my hope is that players from Palette Town won’t have to hoof it all the way to Saffron City to catch a damn rattata.

Find out more about Pokémon GO right here.

Fire Emblem Fates isn’t afraid of big, bold choices

Videogames operate on a timescale that we don’t expect from any other medium. Poetry and music often take minutes; novels and films hours. The day is not an uncommon unit of measure for the time we spend with games, and for games like Destiny (2014) or World of Warcraft (2005), weeks can be the operative unit.

To me, “play” seems like a reductive way of describing a relationship of that length. You watch a movie, read a book, play a game; those verbs seem to describe fairly casual relationships. “Rewatch” and “reread” suggest a higher degree of focus or devotion, but we’re still talking about just a few extra hours. One would need to get into terms like “study,” “analyze,” and even something as overreaching as “understand” or “know” to approach the hours many games expect of us in order to have “played” them.

“play” seems like a reductive way of describing the lengthy relationship with videogames

If reread and rewatch are exceptional, replay is the normal condition of games. The repeated and revised encounter lets us learn the systems that comprise the game. No doubt psychoanalysis would have a few things to say about these compulsively repetitive relationships. But I doubt that we would find it satisfying to conclude that, a thousand hours later, we were “just playing.”

Fire Emblem Fates capitalizes on the time you spend with it—days, certainly; weeks, possibly—in both a narrative and ludic sense. It demands masterful play at anything other than the lowest difficulty. But mastery here is not only a thorough knowledge of its systems, but also includes its characters, the people who you’re leading into combat. If you haven’t played a Fire Emblem game before, this is the best simile I’ve got to explain it: Imagine if, in order to play Chess well, you not only had to know how to use each piece most effectively, but also had to know which pawn loved which knight, who the left bishop would die for, what that rook wants to be when he grows up, etc.

Throughout the series, Fire Emblem has brought with it an idea about leadership that is as much about tactics and bravery as it is about community and empathy. We see the former constantly in games; the latter has, for the most part, stubbornly remained the purview of film and the novel. Thinking about leadership within a collective poses a radical alternative to the kind of heroic individualism that war stories love to traffic in. It’s a pernicious tendency less common in Hollywood, where we might rightly expect a jingoistic good guy with a gun, than in videogames—specifically in the kinds of games Spec Ops: The Line (2012) immanently critiques. Fire Emblem presents ideas of war and leadership that cut against hero worship by making you responsible not only for troops’ movements in combat, but, with the castle-building and support mechanisms, responsible for their well-being away from the battlefield, too.

Fire Emblem Fates expands on this series-long theme of war as a collective tragedy rather than a place for individuals to prove themselves as heroes by making you choose not only how you care for your army, but which side of the war you’re on. Fates contains three full games: Birthright, Conquest, and Revelation. As is conventional in this series (and, indeed, across a whole range of related genres), your character has forgotten a key part of their history. Normally this manifests itself as a simple cipher, allowing for role-play that doesn’t have to be sensitive to ideas of memory or character that precedes your intervention. Fire Emblem Fates‘ excellent predecessor, Fire Emblem Awakening (2012), has a protagonist fundamentally like this.

leadership within a collective poses a radical alternative to the heroic individualism of war stories

Here, though, that absent memory forks your path: you must decide whether to side with the people you just met who claim to be your real family (Birthright), the warmongering family who raised you as one of their own (Conquest), or strike out on your own (Revelation). In and of itself, this presents a radical alternative to the kind of end-game decision-making that you see in games like Mass Effect (2007) or Bastion (2011), where the player finally makes a choice with world historical consequences and is rewarded with one of a few end cutscenes depending on what they chose. The question Fire Emblem Fates asks is: What would happen if that choice were practically the first one you made? What if you could choose your family?

Those divergent paths allow for you to get to know characters on both sides of the battlefield, making the morally uncomplicated instruction you’re often given to start battles—”rout the enemy”—much less of a given. Whether you see a certain character as friend or foe depends entirely on that choice you made, one that is irrevocable except by quite literally “playing out” the alternatives to it. Your family in Birthright becomes your sworn enemy in Conquest and something else altogether in Revelation. As motivations reveal themselves, sympathies shift. There are two places early in Fire Emblem Fates that ask you to reflect on this theme: the eternal stairway and the bottomless canyon. Neither is what their name suggests; of course the stairs end and the canyon bottoms out eventually. But they suggest our recursive relationship to our pasts, memories, and the choices that constitute them: winding upward, falling down, always ongoing, approachable—like eternity and bottomlessness—by thought alone.

In a series underwritten by amnesiac orphans, Fire Emblem Fates breaks away to tell a story about memory, family, and the self, meditating on the decisions that define us and how we regret them. As games are always teaching us, we’re defined by our choices. Fates revels in the irony of its name, which only deepens the further you fall down the bottomless canyon. Recursion through each of the game’s three paths from that originary fork forces you to rethink your place in its world and drives the game’s argument home: Fire Emblem Fates rejects fatalism beautifully.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

March 28, 2016

What the 24-hour deer cam in GTA V tells us about the game

There is a wild deer wandering the paved streets of San Andreas, the fictional city of Grand Theft Auto V (2013), freely roaming the 100 square miles of gangland and beaches. By “wild” I don’t mean that this creature is merely not of civilized society—a wild beast—I mean that it doesn’t fit in with the autonomy of the game’s programmed virtuality. Like the player might be a “wild” integer in the game’s system, chasing their own goals, operating on thoughts and desires that aren’t produced by the game’s code, so too is this deer.

It is, in fact, an artificial intelligence that is ‘self-playing’ inside GTA V. “The deer has been programmed to control itself and make its own decisions, with no one actually playing the video game,” explains the deer’s creator and new media artist Brent Watanabe. He has spent the past months experimenting with the idea of a computer-controlled installation. By unleashing an AI entity into a simulated city he removes himself as artist (a conscious decision to submit to the “death of the author”) to instead let the computer act as the artist, it creating its own scenarios inside the game for viewers to interpret. And yes, there are viewers, as the deer’s activity is being entirely livestreamed onto Twitch.tv—you can view it right here.

he pulls out a handgun and starts to shoot the deer

The deer can be an agent of chaos. Sometimes, it sprints at top speed into a pedestrian, who it so happens is a gang member, and so is susceptible to signs of hostility. When the man picks himself off the ground, he pulls out a handgun and starts to shoot the deer, and the other gang members in that area join in the hunt. A nearby rottweiler runs up alongside the deer and jumps up to take a bite at its neck. Other times, the deer is nothing but a victim to the unending traffic of the metropolis. I once viewed the deer run across a street at night in front of a moving car. It was hit in the side by the bonnet, immediately limp and lifeless. Seconds later the deer respawned elsewhere and continued running in spurts as it tangled its antlers in a line of wire fencing.

The whole set-up reminds me most of Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s sports documentary Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006), in which they used 17 cameras to film soccer player Zinedine Zidane during a 2005 match. Focusing solely on Zidane during this match, cutting between the various cameras they had focused on him, the two creators said the concept was to see what happens to a major football star on the pitch “when TV is not watching.” It looked towards the inaction of a soccer match while the television camera always moves to the most obvious action—keeping focus on the ball. Perhaps, in this, a different side of the professional sport is revealed.

The same idea could be applied to Watanabe’s deer camera. Here, we see what happens in a game when it is not played by a human. And so we are encouraged, when we see the deer causing these kinds of reactions in GTA V‘s virtual world, to make assumptions about the constituent pieces of the simulation. We can say that the city is made to be dangerous, a place of gangland violence, where nature is unwelcomed by the aggression of the populace and the physical barriers they erect around their structures. Further, given that San Andreas is itself based on California, we can extend the analysis to what GTA creator Rockstar means to say about the very real US state that it pins under its virtual satire.

the sanctimony of humanity to lay asphalt upon nature

Before you think this reaching, bear in mind that GTA V is the first game in the series to even include a significant animal population. The early 3D GTA games prior to it only had non-solid props representing seagulls, jellyfish, and flies. GTA: San Andreas (2004) added dolphins, turtles, and hawks. While GTA IV (2008) added flying rats and cockroaches; hardly a zoo. GTA V, on the other hand, has boars, chimps, coyotes, rabbits, cats, crows, whales, sharks, and more. These animals play a more interactive role in the game too, as dogs can be taken for walks, and the hunting side-missions see one of the three main characters shooting wild animals and taking photos of their corpses.

The presence of wild animals goes to inform one of the major themes that runs throughout GTA V‘s San Andreas: the man versus nature dichotomy. This is why, in the game, the city is said to have the most polluted air in the world, and why its Alamo Sea is considered toxic, uninhabitable to any fish that may be caught, and thought to “burn through a man’s lower intestine in seconds” if drunk. There’s also Trevor, one of the playable characters, who is somewhat of a ‘wild man’ who embraces violence and profanity with a near-lunacy.

The wild deer running through the streets of GTA V occasionally produces the sounds of sirens and gunshots. We are used to enacting this as players of the game ourselves and so it is not unique to the deer’s experience. But the moments between the chaos, when the deer butts up against a brick wall or dodges traffic on land that was once green, show us images that riff on one of its bigger themes: the sanctimony of humanity to lay asphalt upon nature, to replace trees with skyscrapers, and then to ask why climate change is happening, or to long for the presence of a declining wildlife. “We won’t be broken hypocrites forever,” goes the San Andreas motto. Despite the denial, this is a videogame in which humanity is framed as the villain, and it’s this the deer cam brings into sharp focus.

You can find out more about the Wandering Deer Cam here and you can watch the livestream here.

We should be talking about torture in VR

This is a preview of an article you can read on our new website dedicated to virtual reality, Versions.

///

It seemed like magic. By hacking together a pair of VR headsets, a group of artists and DIY neuroscientists discovered that they could create empathy between two strangers. Men could empathize with women. The old could understand the young. White people could hold up their hands and see black skin. Not only was VR slick, shiny new technology, but it had a wonderful potential for helping people learn compassion. VR was hailed as a savior, and the praise was piled on.

BeAnotherLab, who conducted the empathy experiments, came away with a darker opinion: it would be just as easy for VR to inflict pain on someone. “VR has the potential to induce severe pain or suffering, whether physically or mentally, if it is applied with a tortuous intentionality,” the team wrote over email. They went on to say that “most certainly, the military will shortly be experimenting with VR as a form of torture if they have not already begun.”

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers