Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 145

March 22, 2016

Twitch streamer plays Counter-Strike with lipstick controller

Frequently placing second among Twitch’s most streamed games, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (2012) has become an institution among the website’s community. At any given moment, there are hundreds of streamers playing the title, all vying for attention as they each try to figure out the most entertaining way to shoot a terrorist. In this space, style is as important as skill, which is what makes Chloe Desmoineaux’s Lipstrike so clever. In Lipstrike, Desmoineaux streams normal matches of Counter-Strike, but rather than using a traditional keyboard and mouse to control her character, she has instead modified a normal lipstick container to serve as her controller, so that she can slay the competition both on the battlefield and in front of the camera.

Having attached a small USB stick with minimal controls to her lipstick, Desmoineaux plays Lipstrike entirely with one hand. She can move forward with the left mouse button, aim with the right mouse button, and switch weapons with the scroll wheel. The best part, though, is how she actually fires her weapons. To shoot, Desmoineaux simply applies her lipstick, meaning that as her enemies die at her feet, she only comes out looking more fabulous.

the most stylish person on the server

Makeup is often characterized as a cage for women, encouraging us to adhere to unrealistic beauty standards that we couldn’t achieve without it. But within the makeup enthusiast community, it’s seen as something else entirely. It ceases to be a tool of conformity and instead become an artform, where the user’s face is the canvas. Here, women—and people of all genders—alter their appearance to their own desires, at once asserting both their identity and their bodily autonomy. This is the meaning behind the term “fierce.” And as I watch Desmoineaux shoot down countless other players who are most likely using far less challenging control schemes, I can’t help but think “Damn girl, that is fierce.”

Lipstrike perfectly captures the idea that in the liberation it offers, applying makeup is not a demure act of self-defeat, but rather a radical practice of self-actualization. It’s fitting that Desmoineaux’s choice of color is a bold red. Just like the blood of her enemies.

You can find out more about Lipstrike over on alternate controller site Shake That Button, and you can follow

Desmoineaux

’s weekly streams over on her Twitch channel. Additionally, archives of her past streams are available over on her YouTube channel.

Pokkén Tournament is killing my Pokémon vibe

“Kids play inside their homes now, and a lot had forgotten about catching insects. So had I. When I was making games, something clicked and I decided to make a game with that concept. Everything I did as a kid is kind of rolled into one—that’s what Pokémon is. Playing video games, watching TV, Ultraman with his capsule monsters—they all became ingredients for the game.” – Satoshi Tajiri in an interview with TIME Magazine, 1999

It’s a fun bit of trivia now, but Pokémon originally grew out of its creator’s simple, childlike sense of awe toward the bugs in his backyard. At its core, the series is still driven by that curious desire to observe, to collect, and even to befriend the fauna that surround us. But on its 20th anniversary, the franchise has ballooned into something with a farther reach and a much more convoluted message than it ever had in its early period. Pokémon is no longer a holy trinity of videogames, card games, and an anime—it’s a detective film, an augmented reality simulation, a series of roguelike dungeon crawlers, a film franchise, an entire marketing universe unto itself, and now, an arcade-style brawling game.

On its surface, Bandai Namco’s Pokkén Tournament seems like the type of game that fits perfectly into Pokémon’s ever-expanding tableau of genre experiments. The game is plainly—and unapologetically—a 3D fighter in which you make cherished Pocket Monsters beat each other senseless for hours at a time, and at first blush this doesn’t actually seem too far out of place in the Pokémon universe. But while there’s nothing inherently wrong with a little of the old cartoon violence, Pokkén Tournament stretches the fiction to an excruciating degree in an attempt to obscure Pokémon’s dirtiest secret: that we’ve actually been making these poor little guys beat each other senseless for more than two decades now, and never really stopped to ask why.

we’ve been making these poor little guys beat each other senseless for two decades now, and never really stopped to ask why

For their part, the folks over at Bandai Namco have done quite a bit of work to try and reduce the conceptual disconnect to background noise in Pokkén Tournament by molding the Tekken template into something more palatable for children and long-time fans of the series. Pokkén’s story arc, if you want to call it that, is loosely held together by a fiction that, unless I’m misremembering the series I watched back in grade school, bears some important distinctions from the Pokémon universe that’s already been established. First and foremost, the Pocket Monsters of Pokkén Tournament take commands from their trainers via a magic crystal-powered telekinetic headset called a “Battle AR,” which is worlds different from the verbal commands that trainers used to give back in the day. It’s a subtle difference, but there’s an implication that the “synergy stones” of Pokkén Tournament’s Ferrum region revoke the free will of the Pokémon under their influence. The game’s main villain isn’t a costumed bandit, but a powerful Pokémon who has fallen victim to a massive, corrupted synergy stone. Unlike the commands in previous games, which Pokémon could disobey if they lacked respect for their trainer, these synergy stone-empowered orders never miss their mark. Already, it’s easy to sense a line being drawn between Pokémon-as-wild animal and Pokémon-as-cartoonish videogame combatant, and it’s a line that Bandai Namco constantly aims to reinforce with nearly every facet of the game’s execution.

We’ve already seen quite a bit of Pokémon-as-nature in the franchise media that’s already been released. The Pokémon anime in particular has always been fond of depicting these creatures in their natural habitats as a direct analog to the grandeur of mother nature. In this universe, the untamed, peaceful grace of the monsters is set in direct contrast with the motives of Team Rocket or, more recently, Team Magma and Team Aqua, who exploit Pokémon in the pursuit of furthering their own agendas. In the anime, as well as in the Game Freak-helmed RPG series, combat is portrayed as a kind of pugnacious but ultimately safe form of sparring, with injured Pokémon disappearing away into innocuous two-toned spheres and abstracted 2D tackle animations depicting what can only be described as a colorful turn-based wiggling contest.

There was always a cluster of messy subtext here, and no real resolution for questions like: why are we capturing helpless animals in little balls? Why, if Pokémon are non-aggressive, are we making them fight each other? Why is the Pokémon universe framed as a disbelief-suspending cartoon, only to be shrink-wrapped in disingenuous and hamfisted “let’s respect the planet” sermonizing? Godzilla may have been shrouded in paranoia and symbolism concerning the consequences of pollution and nuclear energy, but at least he had the agency to fight Mothra when he damn well pleased, and not on the whims of some random teenager with a bright blue flannel shirt and a wispy hairdo.

For most of its history, Pokémon has rested comfortably in a kind of critical stasis. Half-baked Satanist associations and animal rights concerns notwithstanding, the series’ modest origins in schoolyard bug-catching and its cutesy, cartoonish nature meant that it was practically beyond reproach. But the series’ growing scope has resulted in more than a massive product line: as the Pokémon franchise continues to inflate, so does its message. And with new entries coming into the universe on an almost yearly basis, the Pokémon fiction has been forced to adjust its thematic throughlines in order to make room for new creative ventures.

the Pokémon fiction has been forced to adjust its thematic throughlines to make room for new creative ventures

One of the clearest examples of this thematic alteration has been the gradual self-aggrandizement of the series’ lore. Where the first Pokémon games introduced a mythical trio of birds as powerful, elementally-imbued wild animals, legendary Pokémon eventually grew to represent entire concepts—to the point where the series even began to carve out its own internal theology. This reached a fever pitch in 2006’s Pokémon Diamond, Pearl, and Platinum, which introduced a “Creation Trio” of Pokémon who represented time, space, and antimatter. It was also around this time when the series introduced Arceus, the creator of the Pokémon universe. It’s hard to say for certain that this fictional overreach was a product of creative hubris, but it’s a pretty drastic conceptual ramp-up that can get us from backyard bug fighting to the Book of Genesis in a matter of a few years.

As the series’ themes continued to gather mass, so did the prickly implications of its premise. In recent years, players have begun to question Pokémon’s central themes, with the internet concocting new ways of playing the game that pose questions like: how much different would the series be if we looked at our relationship with Pokémon in the same light as a relationship between master and slave?

The growing wedge between message and content, it seems, is the main reason why Pokkén Tournament tries so hard to alter the classic Pokémon recipe without perverting it. If Pokkén Tournament had depicted Pokémon as wild creatures, it would look pretty disturbing for us to sit back and watch them annihilate one another. And so these creatures have been made to look very different from the beasts we might have found in the anime. Instead, the combatants of Pokkén Tournament have been ever-so-slightly humanized to look like Tekken characters, rendered with a child-friendly Nintendo slant. Braixen, the fire-type biped who I actually chose as my main sidekick back in Pokémon X (2013), is no longer a fox standing on its hind legs, but a magical diva with a battering stick and a bit of an attitude. Pikachu, the series’ beloved mascot, comes off as an aggressive little prick with anger management problems. Machamp is no longer a goofy anthropomorphic reptile, but a greased-up, roided-out freak who seems entirely out of place among creatures with more obvious real-world analogs: even the looks like something. All of this characterization helps ensure us that we’re not partaking in animal cruelty, but a more noble, more consent-driven competitive venture. The more human these creatures look—and the more influence that humans have over them in this fictional universe—the better this illusion holds up.

When the Pokémon finally get to fighting each other, the combat feels like it’s been clipped in an effort to stop players from asking too many questions. The pastel colors and smoothed-out graphical style cast a smooth sheen over Pokémon skin and fur as the creatures tangle up in battle. Every single landed strike, while tight and heavy to the button press, has a slightly detached sense of impact, as if your character is wailing on a sack of grain with bubble wrap strapped to its fist.

One of Pokkén Tournament’s biggest talking points is that it’s an accessible fighting game for more casual players, and for the most part this is true. The game rests somewhere on the difficulty curve between Street Fighter and Super Smash Bros. in that it requires very little technical execution, but demands in-depth knowledge of the game’s complex “battle phases” and character traits to fully master. In other words, while the moves aren’t that hard to pick up, the systems themselves can get pretty convoluted.

The game shifts constantly between an over-the-shoulder perspective and a more traditional 2D fighting game format, with each Pokémon’s moveset shifting depending on the perspective. There are support Pokémon that can be summoned during the match (Marvel vs. Capcom, anyone?), and they must be carefully selected before the match for maximum utility. “I just go with my gut,” says the in game tutorial “advisor.” No big deal. But then there’s also the powered-up “Mega” state, where your Pokémon transforms into a more badass version of itself and can unleash a powerful burst attack on the opposition.

while the moves aren’t that hard to pick up, the systems themselves can get pretty convoluted

Despite the sheer volume of stuff at play here, the game’s tutorial voice constantly has to remind you that “you’re in this to have fun.” She’s not wrong, but then again, if any of this felt too high-impact or too competitive, it would fall out of alignment with the central Pokémon themes of self-improvement, human/beast companionship, and unfaltering sportsmanlike conduct in the face of truly sketchy practices in Pokémon husbandry and competition.

Still, Pokkén Tournament glosses over a few of the gritty problem areas that remind us of the series’ more unsavory plot points. As you play through the game’s central storyline, you’re presented with an endless string of matches against AI opponents, all laid out in an ultra-grindy tournament format. Each match rewards you with achievements, new character titles, gear for decking out your avatar, and in-game currency that can be used to buy even more customizations and meaningless kitsch. It’s all one big carrot on a stick, and it makes the space between matches echo with the boring emptiness of its incentive systems.

No longer is Satoshi Tajiri’s original vision of insect-like creatures the orientation point for Pokémon fiction; instead, we’ve got Pokkén Tournament’s crew of bloodthirsty pit fighters who connect to their humans via mind synergy. This wouldn’t be such a bad thing if the central conceit of Pokémon weren’t so troublesome in certain scenarios, and that’s why Pokkén Tournament is such a strange little game. Although its brawls are tense and exciting, there’s no getting around the fact that we’re not just watching beetles wrestle with one another; we’re watching something that looks awkwardly similar to a dogfight. The game tries its best to cover this up, but in the process, gives us a peek through the cracks at Pokémon’s pure, delicate foundation.

This is why Pokkén Tournament seems to open up the questions burning at the heart of the Pokémon series. It suggests that battling Pokémon is done primarily for fun, but the half-hearted delivery of that idea makes it feel fake, hollow, like a high school coach who recites mantras like “it’s only football” but really wants that extra trophy on his shelf. Structurally, the game’s hunger for your time and mechanical skill send a much different message: that self-serving competitive mastery—and not a carefully forged co-existence with nature—is the greatest accomplishment that humankind can aspire to. From this perspective, the Pokémon isn’t a creature of its own agency, but a mere extension of its trainer’s body and mind; a tool in a rat race, forever wrestling in the futile pursuit of human ambition. And when you look at it that way, all the thematic waffling starts to make a whole lot of sense.

March 21, 2016

Playing with touchtone phones and old TV sets at the Experimental Gameplay Workshop

It was an early afternoon on the final day of the Game Developer’s Conference this year. Everyone scuttled into one of the larger panel halls of the Moscone Center, most looking exhausted over one of their busiest weeks of the year (or maybe just hungover). As everyone swiftly got seated, the panel hall buzzed with anticipation for the 14th annual Experimental Gameplay Workshop. Curated by Funomena’s Robin Hunicke and independent game designer Daniel Benmergui, the Experimental Gameplay Workshop celebrates the best of the weirdest innovations of what it means to play. This year’s workshop celebrated 16 games, cherry-picked from nearly 200 submissions, about everything from slapping your friends with My Little Pony-esque hats, swipeable B-Boy emulators, to even simulating the poetic, transcendent mindset of a classic philosopher’s novel.

After the resurgence of a familiar title, the second game showcased of the afternoon was Operator, created by Travis Chen and Peter Javidpour. Operator’s premise is straightforward. You, the player, are a technician of an orbital satellite, aimed directly at Earth. “You don’t know what you’re doing,” summed up Chen succinctly. Luckily you have access to your company’s customer service support line. That’s where the game really comes in. Chen and Javidpour created an interactive tool out of an old touchtone phone, which the player actually uses to dial the support line for help. In a nutshell, as described by Chen, Operator “celebrates the joys of automated customer support systems,” or rather, the immense frustration that comes from them. The original prototype for Operator wasn’t created initially with as much touchtone phone-filled fun, but instead had a voiceover within the game. “[But] it just didn’t bring back those frustrating memories,” said Chen. For Operator, the game was initially planned to be a long “epic” experience, before Chen and Javidpour realized that 10 minutes was the “sweet spot” for fun frustration. And thus, the shortened, touchtone phone-controlled Operator was conceived.

When the word “esport” is dropped, the descriptor “casual” is usually not alongside it. Fortunately, that’s not the case for Richard Boeser’s “casual esport” game Chalo Chalo. Described by Boeser himself as a “a very slow racing game,” Chalo Chalo is a procedurally generated competitive game for up to eight players at a time. Each player is a different colored dot, racing at the speed of a snail towards a yellow cell on the opposite end of the map. Different areas of the map are color-coded. Black areas make the player move extremely slow, red kills the player instantly, and so on. Reaching the goal first nets the player two points, second place gets none, and if they die, they lose a point. For Chalo Chalo’s live demo, the panel hall transformed into a mob of spectators; yelling, booing, and cheering at the cusp of the goal for every match. And honestly, that’s at least half of what esports are all about: gettin’ hyped in a crowd.

“This is why I make games”

Later in the event emerged Jerry Belich and Victor Thompson with a modified 1951 Capehart television set, embodied with various knobs, smackable sides, and adjustable antennas. As the player twists knobs and adjusts the antenna, or bats the side of the television, they solve puzzles on the screen at a given time. Such as: screen’s a bit fuzzy? Adjust the antenna to get a better signal. The game itself, Please Stand By, in this way lies in a similar realm as Operator: both set to portray the deep rooted feeling of frustration when dealing with arbitrary technology. However, Please Stand By hopes to step deeper beyond just its alternative controller’s presence. In the 1950s, technology was ever changing. Radio was a thing of the past. Communism was everywhere. Broadcasts were the source of any and all news. In an updated, longer version of Please Stand By, Belich noted that they want to explore the idea of what if all the broadcasts ended, what would happen? How would people consume information and news? Or as Belich chillingly said, “What happens when there’s no information left?”

The Experimental Gameplay Workshop amplified its celebration of creativity once more this year. The sheer breadth of different aspects of play being explored by game makers was awe-inspiring, whether with creative alternative controllers to enhance the experience, or just looking at the ways we play within games in a fresh, new way. Perhaps the show-stopper of the afternoon was Iranian game designer Mahdi Bahrami’s latest experimental title, Tandis. Tandis is a bit hard to simplify into layman terms.

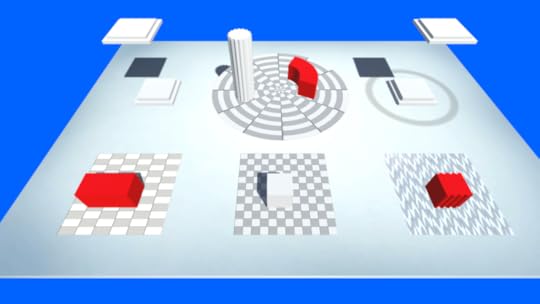

Inspired by Celtic shapes, the game experiments with topological transformation. Topology is the mathematical study of shapes preserved through any sort of twisting or other deformation (such as, a sphere is topologically identical to an ellipse). In Tandis, the player shifts an object between two different flat planes that actively deform the object to match its cousin (another object on the board). Tandis is most simply explained as geometry made into an interactive puzzle; making math actually kinda fun. During its live demo, Tandis’ topological mechanics created a shape that Bahrami didn’t anticipate, and to him even, it didn’t make sense. In between semi-confused laughter, Bahrami said, “This is why I make games.”

A list of all 16 games from this year’s Experimental Gameplay Workshop: Fantastic Contraption (Lindsey Jorgensen and Sarah Northway), Operator (Travis Chen and Peter Javidpour), Plosh: Time Bomb (Chris Hazard and T.C. Chang), Floor Kids (Mike Wozniewski and Jonathan Ng), Chalo Chalo (Richard Boeser), Simple Circles (Jeroen Wimmers), Tandis (Mahdi Bahrami), Mu Cartographer (Titouan Millet), Everything (David OReilly and Damien Difede), Orchids to Dusk (Pol Clarissou and Marskye), Walden (Tracy Fullerton), Untitled (Jason Rohrer and Thomas Bailey), Please Stand By (Jerry Belich and Victor Thompson), Let’s Robot (Jillian Ogle and Ryan Tharp), and Slap Friends (Terence Tolman and John Ceceri III).

Check out the rest of our coverage of GDC 2016 here.

A videogame about making the kind of game you’re not supposed to make

There’s a succinct piece of traditional wisdom in videogame development: start small. It’s common for nearly everyone who wants to make a game to have a great idea for a massively multiplayer online game, but if you’re just getting started, that’s a pretty tough project to get off the ground, to say the least.

At the end of 2014, Aaron John-Baptiste made a game called TMO (Tiny Multiplayer Online) for the weekend-long game jam Ludum Dare. The jam theme was “Entire Game on One Screen” and the tiny MMO-maker plays like a small “clicker game”—you put down Level 1 combat areas until you can afford to build some Level 2 combat areas, and on and on while you keep up with your player base and increase your “Rating” and, consequently, your cashflow. That loop continues as long as you can fit the world on your screen.

demonstrating the underlying structures of MMOs

TMO lets a player see the way quests work in multiplayer online games—talk to an NPC to get a quest, kill 10 monsters, sell loot, talk to another NPC—and in doing so, points out how the system of the “addictive” world you’ve put together mirrors its own systems that keep you playing and expanding your game within a game.

The similarly-named MYMMO grows out of that idea, but, having done away with the single-screen restriction, it already looks much bigger, and it seems the focus has shifted somewhat. It now features chunky Minecraft-inspired voxel graphics (the AI-controlled “players” are already wearing a random assortment of Minecraft skins), and a whole lot more world-building than arranging differently shaped combat areas on a single screen. It looks like the project is moving away from only demonstrating the underlying structures of MMOs and idle-clicking games and towards encouraging players to use its terraforming tools to build worlds that are fun for fake humans to run around in.

Maybe story-telling world simulators like Dwarf Fortress (2006) and the ill-fated Spacebase DF-9 are the new MMOs—appealing but difficult projects for first-time game makers—but since they don’t have to rely on constantly having other people playing, they can find a smaller niche to develop. MYMMO already looks like it’ll be an adorable ant farm. It’s chugging along well with an alpha build planned for later this spring.

You can play TMO here, and follow development on MYMMO here.

New word processor lets you type letters with satellite images

Imagine painstakingly combing through the entirety of Google Maps trying to find buildings, pools, and other structures that resemble letters, then compiling those images together to make new fonts created wholly out of aerial imagery. That’s exactly what creators Benedikt Groß (a computational designer) and Joey Lee (a geographer) did while working on Aerial Bold Typewriter, a new word processor that allows users to easily type full sentences using satellite images of various man-made structures.

“Satellite and aerial imagery are rich with stories,” write the duo, explaining how they came up with the idea for the Typewriter. In 2013, they released a book titled The Big Atlas of LA Pools, which used satellite images to catalog the various pools scattered around the Los Angeles area. While working on the Atlas, they found a love for these aerial photos and envisioned Aerial Bold, a new set of fonts created using letterforms—or shapes resembling letters—taken from satellite imagery across the entire planet. To fund this more ambitious project, they then successfully launched a Kickstarter in October of 2014 to help gather a team and build an algorithm to make the process easier.

“Satellite and aerial imagery are rich with stories”

Now they’ve released Aerial Bold Typewriter to showcase the various fonts they’ve created. As of now, the Typewriter features four fonts, each based on different real-world locales. The first is simply Aerial Bold Satellite, which allows users to type using satellite images, as previously described. Of note is that users can select a specific location, such as Germany, and the processor will only use images from that area. Second is Aerial Bold Buildings, which turns pictures of real-world buildings into vector graphics to make them easier to read. Last are Aerial Bold Suburbia and Aerial Bold Provence, which follow the same process as Aerial Bold Buildings, but using North American/European suburbs and tree patterns from the French countryside as their sources, respectively.

Each font also has a unique set of sound effects that play as users type, giving the Typewriter a pleasing and responsive feeling similar to what’s referred to within videogames as “game feel.” This can be seen in the thrills that accompany firing a gun in games like Nuclear Throne (2015), but Aerial Bold Typewriter helps demonstrate the value this concept has outside of games, as its use of sound manages to make the simple act of typing exciting. Personally, I wouldn’t mind seeing more word processors with this kind of “type feel” in the future.

Fans of Aerial Bold Typewriter can also look forward to September 13th, when Groß and Lee will be teaming up with Penguin Random House to release ABC: The Alphabet from the Sky, a book compiling their fonts and going into more detail on the project overall. Until then, you can try Aerial Bold Typewriter for yourself over on Aerial Bold’s website.

Kanye West is patching his latest album like a videogame

“Ima fix wolves,” tweeted Kanye West some four weeks ago in reference to a track that he was seemingly unsatisfied with from his most recent album, The Life of Pablo. Last week, in the second update Kanye made to The Life of Pablo (streaming exclusively on Tidal), he finally subbed in a new version of “Wolves,” now featuring more pronounced contributions from Sia and Vic Mensa. And this may not be the last update we see for The Life of Pablo either. Kanye has stated that he sees the album as “living breathing changing creative expression #contemporaryart,” implying that it may never technically be done, or to declare it so would be to kill it. While these kinds of distribution subversions, particularly on the Kanye West celebrity scale, are unprecedented in the music industry, they’ve become quite familiar tactics for videogames—tactics that have pushed players to make long-term commitments for seemingly innocuous purchases.

Kanye should look at some of the mistakes that have been made

When it comes to never-finished creative expression, the Early Access program on Steam, the digital game marketplace, has plenty of famous (and some infamous) stories to tell. The basic principle of the Early Access label is that a consumer can purchase incomplete but playable games that will someday reach “done” status and enter the storefront proper. However, the wildly popular zombie survival game DayZ (2013) has been available in Early Access for over two years and its description still pleads with potential players to, “NOT PURCHASE IT UNLESS YOU…ARE PREPARED TO DEAL WITH SERIOUS ISSUES AND POSSIBLE INTERRUPTIONS.” DayZ will probably never be “fixed” or “done” and will stay in Early Access for as long as the program exists. Kanye’s The Life of Pablo may be charting a similar path as DayZ in this regard, and whether he’s up-front with the amoebic nature of the project or not, fans should no longer depend on any single statement (musical or otherwise) from Kanye to remain unchanged forever.

And Kanye’s decision to make The Life of Pablo available only through the streaming service Tidal, of which he is a corporate stakeholder, only adds increased complexity to the matter. While normally one would have to pay $10/month for basic Tidal access, you can instead sign up for a free trial. The rub is that, for The Life of Pablo listeners on release day, the free trial was set to expire just before Kanye’s most recent, “Wolves”-fixing update. Now it’s true that after a bit of outcry, Tidal extended that free trial by another 30 days, but that generosity can’t continue in perpetuity, especially given that Kanye West’s music is the reason Tidal saw itself on top of iOS’s App Store downloads upon The Life of Pablo’s release.

A similar platform-exclusivity marketing strategy (though with far less hand-wringing and Twitter drama) was rolled out for car soccer game Rocket League when it originally launched as a free download for paying PlayStation Plus subscribers last year. The game was, and continues to be, a smash hit with over 12 million unique players to date across three different platforms. However, there’s no doubt that the bundled PlayStation Plus deal helped get the game into the hands of hundreds of thousands of players that may not have touched it otherwise. And just as listeners would lose access to The Life of Pablo if their Tidal membership expired, so too would anyone who downloaded Rocket League for free lose access to the game if they let their monthly PlayStation Plus subscription lapse. Now if only Rocket League developer Psyonix also had an ownership stake in Sony Interactive…

I’m not saying there’s any inherent moral dubiousness in Kanye West wanting his music to live and evolve over time. But perhaps Kanye should look at some of the mistakes that have been made in the videogame space with distribution strategies similar to his own (no one wants another non-refundable creator walkout situation a la The Stomping Land), and learn from them. For starters, maybe Kanye’s next album shouldn’t be named after an old videogame console like the rumored TurboGrafx 16, but rather something more evocative of the contemporary form the album is likely to take. I humbly suggest “The Life of Patch Notes.”

Inside Please Knock on My Door, a new perspective on depression

“This could be anyone.”

This is the premise for game designer Michael Levall’s upcoming game, Please Knock on My Door. It’s a choice-driven narrative, with three paths awaiting the player on exploring the realms of depression, social anxiety, and general phobia.

The game begins almost as any working person’s day would. The player drowsily wakes up from their noisy alarm, and slogs out of bed. Then an omniscient, The Stanley Parable-esque narrator pipes into the game, and urges the player to eat breakfast and speed off to work by 7:30am. This is where player choice comes in, as they can listen to the narrator and abide by their instructions, or choose to stay home and wallow in their bleak, dark apartment. “The shadows become encroaching,” said Levall of the apartment’s space, as the lighting fades throughout the day, and the rooms feel claustrophobic. The apartment is a prison but work is just as emotionally draining. The player feels trapped, no matter what the avenue.

Levall’s research for Please Knock on My Door saw him expand from his personal experiences to listening to his close friends’ own stories, to articles written by people who have suffered from any sort of mental illness. It was this research that solidified Levall’s mindset of not creating just an autobiographical game, but a game with a wider range of perspectives. “While it’s based on personal experiences, it’s not my story, you’re not playing through an autobiographical game,” said Levall. He pulls directly from his own personal experiences only when the game benefits from it, such as modeling the drab in-game apartment from his own past home. “As long as I don’t feel it has a negative impact on the experience,” said Levall. “I use things from my own life to help me get inspired.”

“There’s value in having a choice”

The protagonist of Please Knock on My Door is something of an anonymous entity—that’s intentional. As a black cubular being, with surprisingly emotion-filled rectangular eyes that change depending on the player’s mood, the character is ripe for the player’s projection. The anonymous being can really be anyone, no matter the gender or ethnicity, because of its simple shaped existence. As Levall described it, the character is sculpted with anonymity in mind to show that anyone can feel the “black void” that the in-game character feels.

Tackling far-ranging perspectives has always been a singular point of access for Levall. In his game A Can of Soda (2015), Levall explored the value of having different perspectives on life through religion, focusing on the differences and similarities between Christianity and secular humanism. “I don’t want to make up my mind about something, about what I think is right, and just convey that through a game to the player,” said Levall on his use of perspectives in games. “I want to offer a space where the player can make up his or her own mind about what they think about the themes, such as depression, or life philosophies.”

As the day grows on in-game, the narrator barks at the player for either not following his instructions on leading a “healthy” life, or even prods him with inspirational quotes. Something along the lines of “it gets better,” it says. It’s feels like an empty assertion. As the player stares out the lone window in their kitchen, they see a centered tree (which Levall says is a metaphor for the player’s situation), with other anonymous characters in the distance, smoking or staring blankly at their phones. These outside characters are all alone, isolated, just like the player themselves.

Levall’s game is not the first to tackle the experience of suffering from depression, and it won’t be the last. Levall hopes that his game will exist as a tool for others. Its wide-array of choices in the narrative to prove especially useful to players looking for different layers of perspective within the same title. “There’s value in having a choice,” said Levall. “I think we need several different perspectives, made by several different people, in order to be able to offer the gaming community a better array of perspectives, a better understanding of the suffering that people with these issues go through.”

Please Knock on My Door is aiming to be released in Fall 2016. Check out the rest of our coverage of GDC 2016 here.

Drones: good at spying, shooting, and now art

Will a robot ever be able to write a symphony? It’s a question pulled from that scene in I, Robot (2004) which, while cheesy, tugs on a line of thought that is only getting more relevant—if art is a particularly human endeavor, what happens when a robot tries to make art?

Creators Sang-won Leigh, Harshit Agrawal, and Pattie Maes from the MIT Fluid Interfaces Lab poke at an answer to that question with their project The Flying Pantograph. The gist of it is that they’ve given a drone a marker and programmed it to draw on a canvas in response to human motions with a pen. The drone is programmed with different kinds of responsiveness which in turn lead to different kinds of drawing output, from more precise motion tracking to a very loose responsiveness to guidance. What happens in result is a human-guided but distinctly robotic artistic product, a collaboration in which neither party is fully in control.

It sure is no Picasso. Heck, it’s not even Warhol. The whole exercise is a bit reminiscent of those videos where they give an elephant a paintbrush—it’s cute and endearing and a little unsettling to watch a non-human thing attempt to create some semblance of art. But ultimately we’re in on the joke—a painting by an elephant will never be real art, and the end product in both cases is not something that can really be hung in a museum. However, The Flying Pantograph is still something noteworthy by virtue of the process.

Can a robot have aesthetics?

The creators embrace the “mechanic disconnect” between human intention and drone output, seeing it not as an insurmountable fault but as part of the artistic value. They go as far to describe the drone as if it brings its own intentionality to the process. “It offers its own aesthetics created by a software algorithm and aerodynamics,” their project video explains. Can a robot have aesthetics? Either way, consider the line between artistic intentionality and haphazard circumstance thoroughly blurred.

In the end, this drone isn’t quite ready to write it’s own symphony, nor even draw without the help of a guiding human hand. But in a time when computers are increasingly responsible for creation, The Flying Pantograph calls out both the existence and the nature of the collaboration between human and machine. What happens is not quite fully machinated procedural generation and not quite manual human input, but something in between.

The peculiar future of videogame history

The history of videogames maps directly onto the history of computation. At least, that’s how speakers cast it at GDC this year. Chelsea Howe, Chris Crawford, Dave Jones, Graeme Devine, Ken Lobb, Lori Cole, Luke Muscat, Palmer Luckey, Phil Harrison, Raph Koster, Seth Killian, and Tim Schafer (phew) each talked about one aspect of videogame history in which they were personally involved. The keynote was both an homage to GDC, the event, and to GDC’s prime mover, that repugnant, beautiful monstrosity known as ‘the videogame industry’.

At the 30th iteration of an event that has become one focal point for videogames writ large, the stakes for writing the history of the field seem almost too high even to attempt. Representing all the people who made the moves, deals, designs, and mistakes that made videogames what they are today isn’t something one does in an hour or two. And perhaps it’s truly impossible to do in a cavernous ballroom in San Francisco. Then again, telling this story right next to where Apple announces the iPhone each year seems queasily right considering the history that the speakers settled on.

a violently optimistic way of doing history

The talk began with what was seemed like a leitmotif, but then became a theme before finally unveiling itself as would-be history. It’s about technology, and the fact that chips that make your computer, well, compute have gotten smaller, faster, cheaper, and better, year after year after year. You’ve probably heard of Moore’s Law. It has been one of the tech industry’s waypoints / self-fulfilling prophesies for most of the consumer computing era.

This idea emerged innocently enough. 30 years ago, we used old computers to make state-of-the-art games; now we use new ones. New Macs have 5,000 times the transistors, 86 times the clock speed, and 2,000 times the memory of that laughable (and people did laugh) 30-year-old Mac that some people in this cavernous room used to use to make games. This account trades on the same winking nostalgia we might feel looking back at that scene from Friends where Chandler tells everyone about his “bad boy” of a laptop by rattling off its now-feeble specs.

Many of the speakers at GDC used this move to turn and return to a narrative of technological empowerment that goes something like this: The present is great because computation is the smallest, fastest, cheapest, and best it’s ever been. And the future looks bright, over there there in the hazy not-now! That’s the place where the chips are even smaller, faster, cheaper, and better than they are today.

It’s a seductive argument, in part because it has the advantage of being simply true. Games look, sound, and feel different today than they did when GDC began in the 80s, and technology affected that. But histories like this that are reliably true also have a certain disingenuous miasma about them. Sure, they might be true, but that often means they’re also merely true.

After all, the argument for reading technology as progress itself it isn’t made persuasive by how amazing the technology of the present seems. Current technology usually seems slightly shitty, even or especially when it’s “amazing.” Instead of focusing on the achievements of the present, the argument for technology-as-progress persuades by the promise of tomorrow and its distance from yesterday. If you fully buy in, today is always already the best of all possible days. (Remember how terrible yesterday was?) And tomorrow will be even better. It’s a violently optimistic way of doing history, but a great way of doing business. The near-future technological promise is the economic ground on which the Bay Area rests. You’ll note the presence of the San Andreas Fault.

I always think about America’s favorite piece of Concord pond scum, Henry David Thoreau, at moments like this. Thoreau emphasizes that nothing in the world of the mid-19th century United States really needed to run at 30 miles per hour. “We do not ride upon the railroad;” he writes in Walden (1854), “it rides upon us.”

So, yes, as technology changes, new things become possible, from living west of the Mississippi to living in The Witcher 3‘s (2015) expansive kingdoms. But our expectations and assumptions catch up with the technology. The railroad rides upon us. And the best of all possible tomorrows never arrives as promised. Google Fiber will seem like Chandler’s 56k modem before long. But is life better with Fiber than it was with 56k? That’s a serious question, and one these histories recklessly, disingenuously didn’t ask.

I find it strange that this is the story—naive, earnest, predicated on a stable notion of progress—that luminaries in the game industry decided to tell about their lives’ work. Saying that the history of videogames is the history of technological improvement is tantamount to saying that the history of literature is the history of writing implements, from cuneiform to Shakespeare’s quill to David Foster Wallace’s Microsoft Word. The quill didn’t write King Lear; Word didn’t write Infinite Jest (even if it helped with the footnotes). Such a history mistakes tools for art.

Check out our ongoing coverage of GDC 2016 here.

No Pineapple Left Behind spends too long in the classroom

You are a school principal. You see a student who is being bullied. His parents ask for you to keep an eye out on him, make sure his feelings aren’t hurt. There will be hell to pay if he is sad when he goes home. You could stop kids from picking on him. Or you could help his self-esteem. But the easiest way to not get an earful from the student’s parents? Have his teachers use lasers to turn him into a pineapple.

In No Pineapple Left Behind, from Subaltern Games, you play as this peculiar principal. You have to juggle the responsibilities of supporting teachers, improving students’ grades, and managing a budget. This is quite a job, where accounting for every dollar of your daily spending allowance becomes crucial. It is much easier to resort to your magical power, which drains the humanity from kids, turning them into pineapples. The titular fruit has no feelings or distractions. They just learn. If only real life were as easy.

THE TITULAR FRUIT HAS NO FEELINGS OR DISTRACTIONS. THEY JUST LEARN

As the title suggests, No Pineapple Left Behind is a satire of the “No Child Left Behind Act” of 2001. The concept of this act is to punish schools that aren’t performing well by reducing their funding. Many claim that the result has been an education system geared solely towards passing the tests used to measure performance, rather than teaching subjects fully. Some teachers have even been caught cheating for their students, hoping to ensure they have bigger budgets to teach with down the road. It’s an imperfect solution for a messy system.

No Pineapple Left Behind creator Seth Alter, a former teacher, used the frustration he felt from his time in front of the classroom to fuel this latest game. He pipes the frustrations he experienced during that former job into a game is both silly and critical. The blows that Alter delivers to the school system tend to be heavy-handed. In No Pineapple Left Behind, children have a humanity rating, and as they learn and grades go up, it automatically goes down. When it hits zero they become pineapples.

This isn’t as alarming as it reads: the game is presented with its tongue firmly planted in its cheek. The title screen looks like Soviet-era propaganda. The music feels like a militant march. The lesson names, like “Invisible Hand’ and “Trigonomancy,” as well as teacher’s laser attacks, like “Cheating Bolt” and “Unfriender Nova” are meant to make you smile. The levels in this magical world drive the satire home with their amusing obstacles: child tardiness due to teleporting buses running late during a drivers’ strike, or overcrowding because a wing of an underwater school is being flooded. The children talk to each other with emojis and messaging language like “U SUX.” There is even a game called Fruitbol. Turning kids into pineapples isn’t so outrageous among all this.

As a principal, however, you’ve got to keep a straight face, working towards increasing students’ grades (and decreasing their humanity). The higher the grades at the end of the day, the bigger budget you have for the next day. The result of this system is micromanaging every aspect you can, switching lessons and educational materials between classes, zapping students with lasers to dehumanize them or to end their distracting friendships. It’s a lot of work, and students can still fail to learn the lessons taught, their grades going down (and humanity going up). Often, it is easier to have a teacher zap the children into pineapples, then push to reach the high grades you need to finish a level or to earn more money. Reduced to objects, the students can be approached purely analytically, fixed with just the right approach, all without the messy empathy or complexity that dealing with people requires. Morality be damned.

MORALITY BE DAMNED

But adjusting teachers’ situations continuously exposes another challenge of the game, which in turn, reflects another of the difficulties of real world education. The more money you give teachers, the more energy they get back overnight to fuel the next day’s lessons. In the beginning, a teacher only has a class or two, but that grows to five per day. Teachers can’t lead five classes and give their all for every single one. Some get crappy lessons to conserve the teacher’s energy. Inevitably, you hit a moment when it becomes cheaper to fire your teachers and hire new ones than to pay your burned out teachers to come back the next day. The grim fact you learn is that overworked teachers, driven by your own whip, are not as effective as those that are not—there is no mercy when money is the ruler.

Pulling back from these finer details, No Pineapple Left Behind is divided at the macro level into different schools in the different neighborhoods of the fictional city of New Bellona. Each school is a level with specific objectives to meet, such as reaching a $1000 surplus in one week, or avoiding going bankrupt in a period of two weeks. Surviving the typical grind of the game is difficult enough but the later challenges become gruelling. Add parents complaining, along with budget penalties if you don’t address issues like students being teased or grades not going up, and succeeding in managing a school becomes a nearly impossible task.

Unfortunately, No Pineapple Left Behind, in satirizing a long and tedious job, becomes one itself. The daily routine of pausing to adjust a teacher’s lessons and materials, unpausing so a class occurs, then pausing to reassess and readjust for the next class, and then repeating all that for each class, while strategically shooting lasers to turn kids into pineapples; it wears you down.

The systems of the game are interesting at an intellectual level, good for discussion, but they aren’t compelling to play with. Yes, the game succeeds in showing that the only strategy to be a good principal in such a system is to fire new teachers instead of bringing back veterans. It displays that rigid education can dehumanize students. And it shines a light on the ridiculous juggling a principal has to do to keep it all afloat, and does it in a somewhat amusing way. But it is a satire that becomes increasingly hard to appreciate the longer it goes on.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers