Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 143

March 28, 2016

Threadsteading is a strategy game you play by sewing

Threadsteading is a strategy game about quilting, or perhaps more accurately, a strategy game that is quilting. Controlled by a quilting machine (or an embroidery machine in its portable form), Threadsteading is a two-player competitive game. In it, the players try to nab territories on a hexagonal grid, using a similar-shaped button-module to dictate the direction the player will guide the thread that the machine sews. The game was initially developed during a game jam at Disney Research Pittsburgh, the project helmed by Gillian Smith, alongside team members April Grow, Chenxi Liu, Lea Albaugh, Jen Mankoff, and Jim McCann.

breaking gendered activities

The quilting machine version of Threadsteading is massive—with a 13-foot wide arm to sew. For practical travelling purposes, the Disney Research team opted to create a smaller, more portable version of the game, programming similar gameplay into an embroidery machine. At alt.ctrl.GDC this year, an area on the annual Game Developer’s Conference dedicated to celebrating alternative controllers and ways of play, the embroidery machine version of Threadsteading was on display in its playable form.

For the territory-control gameplay itself, a hexagonal grid printed on cloth is used as a board within the machine. As players direct the the thread using the button module (a different pattern for each player is used for both players), they try to nab any of the six pink “town” squares across the map. Different colors of terrain use up different energy per turn, and the player only has four energy to use. At the end of the game, the machine itself tallies up the score per player and sews it onto the board.

Inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry, a 68-meter-long embroidered cloth depicting history up until the Norman Conquest of England, Threadsteading is an interesting and fun experiment in alternative ways of play—and in breaking gendered activities. In an interview with Gamasutra, Gillian Smith explained, “Gaming is a lot more balanced in the gender of participants, but societally still seen as quite masculine. So some of our interest is also in juxtaposing these two differently gendered activities.”

Photos and gif by Caty McCarthy

Tetris and the future of architecture

French architectural genius Axel de Stampa created a dancing ode to Tetris (1984) with the 2014 debut of his gif art gallery Architecture Animée. The introductory image sees large Tetris piece-shaped buildings fall from a blue sky to interlock themselves with the grounded structures below. The result is a series of architectural tetrominoes that reveal an understanding of the choreography and composition of each great city. But this is more than a videogame reference, as it alludes to the need for movement in the skyscrapers and city blocks of the urban utopias of the future. There is a growing demand for spatially efficient and moveable office spaces and apartments that could potentially reduce urban congestion, while also allowing cities to grow outwards and perhaps even inwards, onto themselves. With his gallery, Stampa realizes the dream of changeable, pieceable, and transformative architectural units that the design concepts of the future may move towards.

the need for movement in the skyscrapers and city blocks of future urban utopias

This is not a new idea. Kisho Kurokawa initiated his version of the architectural future with the Nakagin Capsule Tower, which was completed in 1972 and consists of 140 concrete, liveable capsules fabricated into the backbone of the tower itself. The crux of the concept is that any of the capsules can be moved out of the tower by the owners at any time and installed at a different part of the sprawling metropolis that is Tokyo. Kurokawa’s brainchild was still very much ahead of his time—today’s architectural norms haven’t yet caught up with his idealistic perspective on spatially efficient approaches to architecture. The story of the Nakagin Capsule Tower remains something of a tragedy, a forsaken approach to urban growth and development. Kurokawa passed away in 2007, passionately protesting the Nakagin Capsule Tower owners’ collective decision to demolish the building, which is situated in the celebrated Ginza district where real-estate is always in high demand and quite expensive. Fortunately, the advent of the financial crisis prevented any such destruction and the tower was saved, though only half of the capsules are actually used today due to the derelict condition of the apartments themselves.

It is clear that tomorrow’s progressive architects and designers must continue to find innovative ways to create spatially efficient living spaces and offices without compromising on the distinct character of each space, as demanded by the owner. Architect Julien De Smedt from PLOT puts it perfectly, “We live in a world where individualism has larger resonance than previously. Diversity is well accepted, even desired. People who live in a housing complex of 221 apartments should have the same access to individuality.” PLOT has readily embraced the concept of providing architectural individuality rather than following the masses with stereotypically suburban cookie-cutter ideas. This is shown in the VM Houses that De Smedt and his partner, Bjarke Ingels, created using a series of permutations of interlocking tetromino spatial units. It turned out to be the final concept for their curious Copenhagen apartment complex, which actually won the Forum Prize as the best new building in Scandinavia. We see here the architecture of the future once again turning to Tetris for its template.

An environmentally-friendly approach towards modern architecture would add yet another layer of complexity to futuristic pieces. David Fisher’s company aims to create rotating towers that use self-sustenance methods—buildings that are completely powered by wind and solar energy that react dynamically with their environment. Even Ayn Rand couldn’t have conceived of such new-age creations as she was writing in favor of modern, unconventional architecture in her 1943 novel The Fountainhead. What’s interesting about David Fisher’s approach is that it promotes individuality by embracing movement, allowing the inhabitants of each living space to experience a complete 360-degree perspective of their surroundings. Compare this to the designs of De Smedt and Ingels, who also regard their permutations and combinations of tetrominoes as creating distinctive, individualistic living spaces, yet see them realized as part of a single collective unit. The major difference is that the Tetris pieces It might be argued that their Tetris-based concept is the definitive metaphor of a socialist approach towards architecture, seeking out an equalizing factor.

This should come as no surprise given that Tetris is is a product of the Soviet Union, designed by Alexy Pazhitnov and programmed by Vadim Gerasimov in 1984. It has long been theorized that a communist concept underlies the game’s single task. After all, it’s a puzzle game about taking a variety of distinct shapes and melding them into one uniform whole. Everything individual is removed in favor of all being equal. And yet the spatial manipulation inherent to Tetris has spurred on many other modern architects to create structures that don’t fall in line with this political parallel. There’s the Tetris House concept, for instance, created by Dutch firm Universe Architecture. This concept also uses prefabricated movable blocks as living spaces, allowing entire homes to be transformed and melded together into apartments. It allows the owner to redefine the contours and the identity of their living space at will—it entirely supports individuality. It also suggest that this age will perhaps be one where a lifestyle of spatial variety will finally be embraced, maybe even becoming commonplace. Perhaps Kurokawa’s decades-old decomposing dream of absolute prefabrication will finally be re-envisioned by today’s more avant garde architects who will dare to design something new and different, perhaps even verging on radical.

gif via Axel de Stampa

There is mathematical proof that states almost all Tetris games must end. An infinite game of Tetris is very hard to attain, no matter how great the player’s gaming skills or strategy, but not impossible. This concept could be translated in terms of the architectural world as well. While infinite Tetris-concept skyscrapers might be physically impossible to realize, perhaps mathematical algorithms and modern data analytics can help construct the right permutations and combinations needed to create dense layouts of spatial units that could cater to large, growing populations. How will tomorrow’s architecture capture all of humanity’s lifestyle choices? What will the London or New York City or Tokyo of 3016 look like? The result could be a series of distinct concrete jungles unlike any other; skylines blazing with curves and tetrominoes and dancing buildings and twisting towers synchronized to sublime metropolitan choreographies. Kurokawa would be proud of such a sight.

featured image via urbz

Mosaic will tackle the soul-crushing surrealism of adult life

Kafkaesque. It’s a word whose usage in everyday conversation has inspired an unfair status as a self-effacing pejorative of pseudo-intellectualism. Believe it or not, Kafkaesque does retain a meaning apart from these misconceptions; a shorthand description of the soul-crushing drudgery and ineffectual bureaucratic tyranny found in the absurdist-nightmare fictions of, you guessed it, Franz Kafka. It’s a word that’s grown to typify the restless indignation of the individual working in the white-collar hive-mind of the 21st century, and it’s a word that aptly describes the tone of Krillbite Studio’s upcoming point-and-click adventure Mosaic.

you’ll start to realize that something is askew

In deciding to step away from the tried-and-proven success of its debut Among The Sleep (2014), Krillbite is attempting to explore the next evolutionary leap from the emotional horror of childhood: the malaise and existential surreality of being an adult. “It’s about being a small piece in this big machinery that you don’t feel anything for,” says artist Bjørnar Frøyse about Moasaic. “Games don’t have to be a kind of escapism […] they can leave you with something more than that.”

With a length currently sitting around three hours and a release slated for sometime next year, Mosaic is an attempt to do just that. As your day starts off like any other—passing through security, settling in front of your terminal—you’ll start to realize that something is askew about your respective role in this fluorescent-lit farm of cubicles. What answers might lie at the conclusion of this personal journey Krillbite won’t say, preferring instead to offer players as clean a slate of impressions as possible before diving through their first playthrough. Whatever other mysteries Mosaic might have in store for players, we’re sure to be left with at least a few clues to those answers leading up to the game’s release later next year.

Look out for updates on Mosaic over on its website.

An intro to tabletop gaming as ritual

Every time I unbox a board game it feels as though I’m ‘starting something’. There’s a secure rhythm in drawing out components, shuffling decks, placing pieces; it feels significant in the same way that the placement and positioning of elements in communion or offering feels holy. Mats are laid out, figurines placed, tokens piled according to kind. Victor Turner wrote the following in “Symbols in African Ritual” in 1973:

“A ritual is a stereotyped sequence of activities involving gestures, words, and objects, performed in a sequestered place, and designed to influence preternatural entities or forces on behalf of the actors’ goals and interests.”

Society is comprised of a number of closed loops: regular business hours, reliable services like money withdrawal or ticketing, religious liturgy. Banks and donut stands alike thrive on predictability. So do churches, news sites, nurseries, universities, Tumblrs, and bike shops. Much like train schedules and the Eucharist, each board game is a kind of closed circuit, a mechanism designed to operate by certain rules to produce a specific experience.

Embedded in these rituals of play are distinct cultural events

When I splay out the monstrosity that is Eldritch Horror (2013) on my grandparents’ dining room table, I raid the cupboards for small bowls in which I place travel tickets, brain-shaped sanity tokens, monster tiles, clue tokens. After the other players are gathered, I gesture to progress tracks and parts of the board state, explaining the mechanics we need to know to start playing. “We’re fighting an ancient evil,” I say, “and we have to work together if we want to stop it.” The ritual we’re undertaking, playing this game, is purely in service of the preternatural forces of fun, friendship, and intellectual exercise. And also in service to defeating Cthullu.

“Board games are engines to create memories with people,” said Quintin Smith, of the tabletop games blog Shut Up & Sit Down, in an interview at the 2015 Fantasy Flight Worlds Championship. Each unique system is meant to simulate or reflect social moments, such as shared survival, trust, rivalry. Embedded in these rituals of play are distinct cultural events: processes of incorporation, of cleansing, of invoking higher powers for gain in certain spheres. And so it is that we can categorize various styles of board game experiences according to their ritual parallels, such as the five below.

Henrique Poyatos via Wikimedia Commons

Henrique Poyatos via Wikimedia CommonsRite of Passage

There’s an element of becoming involved in any gaming experience. In Agricola (2007), we become farmers; in Catan (1995), settlers; and in Ticket To Ride (2004), bored plutocrats. In hidden identity games, though, the lifeblood of the game is wound up in creating a society and tasking a few players to sabotage that society. These are games in which trust is currency. The Resistance (2009), Shadows Over Camelot (2005), and any variation on the Werewolf (1986) and Mafia (1981) genre (i.e. last year’s Mafia de Cuba) involve setting up a complex ecosystem in which players must lie or stretch the truth to some degree to survive. These games are about separation from a society, and subsequent incorporation into that society. Successfully incorporating oneself into “the group” is the goal, regardless of whether or not a player is “one of them”: it’s about the ritual of becoming, not actually being. Much like Confirmation for Catholics, a Bar/bat Mitzvah in Judaism, or the Walkabout in Aboriginal Australian society, the point is to become part of the whole.

The mechanics in the hidden identity game are social, not technical: verbal battery and interrogation, group assessment, and eventual incorporation or estrangement depending on whether or not the subject meets the group’s standards. In Avalon (2012) and this year’s Secret Hitler, votes are cast to determine whether or not the group trusts the individuals. Players win or lose based on how well they can be trusted and how well they judge their fellow players—or if their faction’s compatriots hold sway. Regardless of whether or not friendships have been shattered, the illusion of this new society (and one’s place in it) is shattered when the game ends.

Ritual of Purification

There are a variety of games designed to play out like unfolding crises. These are cooperative in nature, or at least heavily collaborative, and include the likes of 2008’s Pandemic (curing disease), 2008’s Ghost Stories (exorcising ghosts), or 2010’s Forbidden Island (keeping an island afloat). Every mechanic works to up the tension like a self-winding trap as players work to mitigate the crisis and prepare for new disasters. Board games of this nature are mostly mechanical puzzles, and require players to think together. Others, like Descent (2005) and The Fury of Dracula (1987), pit a group of players cooperatively against one player in asymmetrical play.

A wasted round can end a game prematurely

Typically, a rite of purification needs a shaman or spiritual leader. And regardless of how egalitarian a group of players may be, a similar dynamic often emerges during gameplay. The most experienced player often guides other players’ hands to make “best decisions” in a game like Arkham Horror (2005) in which play itself feels like a constantly losing battle. A wasted round can end a game prematurely, and direction is often sorely needed. Like its cultural counterpart, this kind of game can end abruptly with nothing to show for it save its psychological drain.

Rites of Political Power

Gluckman’s conflict-focused study of political anthropology is at the core of many politically-themed board games. The tensions of navigating a claustrophobic board space with other players are fuel for Risk (1959), Chess (1475), and Small World (2009). These tabletop games can solidify one person as “chief” of one’s social circle, prompting favors (ie. “Losers buy winner ramen,” etc.) but, unlike the shaman in more cooperative games, everyone wants to be the chief. Through direct competition—with less cooperation, and maybe with a little luck—the chief establishes herself.

However, as in Geertz’s observations of the traditional Balinese state, power in these games lies in how one is perceived. The most powerful player may have nothing other than an image. Still, how the group reacts to their perception of that player can put someone else ahead. This is particularly salient in a game like Cosmic Encounter (2008), in which a simple over or underestimation can hand a player the win. And in the heady A Game of Thrones: The Board Game (2003) which runs off of player suspicions, misplaced trust can cost a player dearly.

Rituals of Harvest and Bounty

Some rituals are about invoking powers for greater fortune or bounty—and these might fit roughly under shamanic purification (solving a spiritual problem). However, people gather during harvest rituals such as Thanksgiving to celebrate abundance, not simply to ask for it. The same is true of many Euro-games like Agricola or Settlers of Catan, or even economic simulators like Machi Koro (2012): the ecosystem of the game is designed to feed the players, who harvest and feed back into the game as they build their own economy. Competition here is often passive, and there’s a sense that “you get out what you put in” along with a bit of luck. The “offering” players make at the end of these games is the sum of what they have earned; the payoff is victory.

Commemorative or Calendrical Rituals

According to my friend Amangul, Kazakhs and Turkish people feast for three days on Nowruz to celebrate an ancient Persian massacre. On Columbus Day, we commemorate a man who exploited the Americas. These holidays are embedded rituals that serve to keep significant bits of history relevant, even if we mostly use them to overeat or buy extravagantly. Tabletop games like Twilight Struggle (2005) and Memoir ‘44 (2004) commemorate the paranoia of the Cold War and the furor of the D-Day Landing, respectively. Though, they’re mostly an excuse to gather two or more people around the dining room table to wage complex tactical and psychological warfare.

The celebrated events don’t even have to be real. The upcoming Star Wars: Rebellion is a tactical war game that invites players to reimagine moments and events from the films, often in unique ways. When one examines the potency of role-playing a part, either as an unsympathetic villain or inscrutable hero, the ritual of play becomes more an exercise in empathy, inviting players to experience moments they never would otherwise.

Header image: Valentin Gorbunov via Wikimedia Commons

March 24, 2016

Game turns you into a 1920s phone operator, complete with vintage switchboard

It must be difficult for a game made on 89-year-old hardware to stand out anywhere, let alone at a conference brimming with excitement over upcoming virtual reality headsets like PlayStation VR and the HTC Vive—it wouldn’t help that this game assigns the player with a menial day job that’s now handled by computers, either. But when Kill Screen’s Jess Joho visited the alternate controller exhibition at this year’s GDC, she found herself most interested not in Sony and Valve’s latest technology, but rather Hello Operator, a game played with an actual telephone switchboard that first saw use in 1927.

Hello Operator has you take on the role of a telephone operator from the 1920s, using an antique controller to manage dozens of impatient customers across a limited number of three or four phone lines. Intrigued, Joho sat down with creator Mike Lazer-Walker to ask him some of the questions that crossed her mind while she was playing the game.

“For me, this is really interesting, because with the original female computers and then with telephone operators, there’s this trend in our technology that women are there to connect us,” explained Joho. “Do you think people respect this kind of work? Is that something you were going for with this?”

“I’m really interested in exploring that,” Lazer-Walker told her, going into the history of real-life telephone operators. “What’s fascinating about this is that, originally, switchboard operators were men. But the work was too tiring and they were so gruff and so nasty that they then brought in the women instead.” He compared it to the early days of computing in which women handled the tasks men didn’t want. “It was sort of the opposite of computing,” explained Lazer-Walker. “In computing, no one wanted to do it at first, so it was considered women’s work, and then the men came in when they found it interesting enough.”

“So, then, who have you seen take to this kind of work?” asked Joho.

“A thing about this is it’s really hard, but at the same time, it’s very good at getting you into a state of flow,” Lazer-Walker replied. “So it’s interesting seeing who the people are who really enjoy sitting down and feeling challenged.” Of course, the novelty of the controller also draws some players in, as he continued: “And similarly, it’s neat to find the players who get into the role play and end up feeling really bad for the people they’re leaving on the lines.”

“How does the way you physically interact with a story affect it?”

Harkening to classic work games Diner Dash (2004) and Tapper (1983), Lazer-Walker explained that even though Hello Operator is about menial labor, working a job and balancing disgruntled customers can actually be quite enjoyable within the context of a game. “Time management games are such a well-worn genre that as an industry, we know how to design these and make them fun.”

Lazer-Walker had previously told Joho that he was also interested in giving the game a narrative, and curious how that might work within the context of labor, she asked how he planned to address story within that experience. “I’m really interested in exploring what happens when you can listen in on conversations,” Lazer-Walker replied. “What does it mean when three people are making calls at once and you have to decide who to listen to? How can I make sure that you have an interesting story? Is it like a murder mystery, where you have to figure out who did it? There’s a really big narrative possibility space there.”

This reminded Joho of her days playing hotel or other “ridiculously menial things” as a child, and the stories she would come up with while playing. She asked if that “love of getting the job done” was something that Lazer-Walker wanted to capture with Hello Operator. “Yeah, and I think the two things that really interest me about this are that sort of menial getting into a state of flow and having fun, and doing that in context of old technology,” replied Lazer-Walker. “And then on the other side, looking at how you take the same physicality and apply it to storytelling. How does the way you physically interact with a story affect it?”

After all, this isn’t Lazer-Walker’s first time experimenting with alternate controllers. Prior to this, he developed a game called What Hath God Wrought, named after the first message sent via telegraph. Like Hello Operator, What Hath God Wrought also used antique tech as its controller, this time a 19th century telegraph machine. By having players use an actual telegraph, Mike hoped to make them more familiar with morse code despite most of them having no experience with it. Seeing the game as a predecessor to Hello Operator, he explained that with both titles, he was asking “How can we take these things that are sort of interesting and compelling and use those to get you to learn about old technology?”

The result are games that call back to eras where the modern conveniences players might take for granted today, such as being able to place a call without having to go through an operator, were handled by real people who were working real jobs. In taking on these roles, players are able to learn, if only for a small fraction of time, a bit more of what these people dealt with in their daily lives. “I can’t teach you morse code in five minutes,” Lazer-Walker explained. “But can I make you feel like you know morse code?”

You can learn more about Hello Operator over on its website. Check out the rest of our coverage of GDC 2016 here.

The demolition of Japan’s videogame history

In the eastern region of Kyoto, Japan, there lies an area named Higashiyama, filled with shrines, temples, and the Kyoto National Museum. It was here in Higashiyama that Nintendo built an office complex with buildings adjacent to one another that the company’s greatest designers worked in. Almost everything videogame-related that Nintendo developed before the year 2000 came from the complex known as 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho—from the original Game & Watch and Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), to Donkey Kong (1981), Super Mario Bros. (1985), The Legend of Zelda (1986), and Metroid (1986). But while these games can still be played the buildings they were created in are now gone.

At one point in time there were approximately five buildings at 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho, including Nintendo’s headquarters and its iconic Research Center. The construction and exact dates of establishment for each of these buildings remains a mystery. What is known, however, is that in the past 15 years, two of these five buildings have been demolished. This absence coincides with recent concerns related to videogame preservation. As more buildings are torn down, we are urged to question the historical value of the physical birthplaces of iconic videogames.

The discussion among those in the game preservation community, including the IGDA, concerns whether game companies should begin preserving their physical legacy in the form of museums and archives on company property. Japanese corporations including Casio, Mitsubishi, NEC, Panasonic, Seiko, Sharp, Sony, TDK, and Toshiba all have corporate museums and archives open to the general public. They are regularly visited by tourists, educators, students, and prospective job applicants. Many of these same companies have manufactured countless integrated circuits, display screens, and other components for videogame hardware over the years.

Nintendo’s 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho office complex as seen in the mid-1990s (left) and what the complex looks like today after two prominent buildings were demolished at the complex. What remains is the former Kyoto Research Center Building, now home to Mario Club. Courtesy: NHK and Justin Doub (Twitter @JustinDoub)

Nintendo’s 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho office complex as seen in the mid-1990s (left) and what the complex looks like today after two prominent buildings were demolished at the complex. What remains is the former Kyoto Research Center Building, now home to Mario Club. Courtesy: NHK and Justin Doub (Twitter @JustinDoub)By establishing a museum or archive, a videogame company moves towards acknowledging the value of its legacy, making it both publicly observable and ensuring its ongoing protection through a continuous cataloguing of production material. Keeping all of this in a single location deemed permanent and secure adds to the seriousness of the commitment. Yet the unsettling prospect remains: Where does every single element from a finished videogame go once production and publishing is finished? The fear is that it remains scattered throughout departments and development staff workstations, unorganized and vulnerable. Making use of company real-estate to establish a place to organize, store, and even display these elements is the simple but often overlooked solution to a medium’s disappearing history.

///

Due to confidentiality, we don’t know the full extent of the work that went on in the buildings at 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho. When the time comes to tell the stories behind Nintendo’s earliest games, it is often pieced together from various sources, that is if it can be pieced together at all. All that’s currently left are fading memories from former and current staff as well as some archived media, both of which are often difficult to track down. And so, the limited history of Nintendo’s 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho complex is the result of bringing together various tourist photographs, Google Map images, and news media snapshots and video. All this first-hand evidence is vital to establishing the true history of these buildings. For instance, Nintendo’s official history on its corporate website says it merged all its playing card manufacturing facilities to this location in 1952, and then moved its headquarters to the complex in 1959. However, a stone plaque hanging down the street from the guarded entrance gate to the complex in Higashiyama tells a different story—it commemorates its establishment as 1954. Unfortunately, such historical clarity isn’t always possible. Nintendo’s headquarters once sat at the left of the entrance gate, and on the far-left was what is assumed to be a manufacturing facility, with Nintendo’s kanji logo displayed in blue on white signage. Both of these buildings are believed to have been built sometime in the 1970s. At the center of this complex was Nintendo’s three-story Kyoto Research Center, built in the late 1980s. Then there are two smaller buildings that stand at the back of the complex, but their history and current usage remain a mystery.

Where does every element from a videogame go once production and publishing is finished?

Nintendo ended up outgrowing this area, and in 2000 moved its headquarters to its present location: 11-1 Hokotate-cho in the Minami-ku ward of Kyoto. Within a few years (the exact date is unknown) the former Nintendo headquarters building at 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho was demolished and a green patch of land replaced it. Intelligent Systems, a Kyoto developer that has close relations with Nintendo, would move into Nintendo’s Kyoto Research Center at 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho in 2002. It was here that Intelligent Systems developed Fire Emblem, Paper Mario, and WarioWare as well as development tools for the Nintendo DS and 3DS handhelds. In 2013, Intelligent Systems moved out and transferred its entire operations into its own building, an eight-minute walk from Nintendo’s current headquarters. At around this time, Nintendo began constructing a new development center in the same area of its headquarters. The Nintendo Development Center, a seven-floor eco-friendly structure complete with rooftop solar panels and a rainwater recycling system, opened in June 2014 with reported construction costs of 19 billion yen ($186.3 million USD).

One year later in 2015 another one of Nintendo’s larger buildings at 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho would be quietly demolished. The three-story rectangular building iconically displaying Nintendo’s blue kanji logo to surrounding neighborhoods was gone. What remains is the former three-floor Kyoto Development Center. On occasion, it has been mistaken as Nintendo’s headquarters by the media. The Kyoto Development Center is now home to the Nintendo subsidiary Mario Club, which focuses on game debugging services for the company. Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Nintendo of America declined to comment on the history and future of the 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho complex in Kyoto.

///

Nintendo has certainly never ignored its past, and in fact has chronicled much of its history in former Iwata Asks website interviews with senior Nintendo staff. Nintendo New York (previously known as Nintendo World) and Pokémon Centers in Japan serve as both company stores and showrooms for new games. Nintendo New York in particular has exhibited items from Nintendo’s legacy, from game design documents to its vast line of handhelds. However, this has not stopped tourists in Japan from trekking to its various office buildings in Kyoto to pay tribute. While some may see these buildings as basic offices with fluorescent lighting and a maze of workstations, fans see them as attractions to visit and pay tribute. They pose for photos with character merchandise outside company entrance gates to share on social media, some hope to catch a glimpse of some kind of game development (or game developer personality), while others ask security guards at the gate if they can enter and take pictures at a better angle, only to have their request turned down.

Left: A young Shigeru Miyamoto works at his desk at the 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho complex in the mid-1980s. Right: Masayuki Uemura, the designer of the Nintendo Entertainment System (left) and game designer Shigeru Miyamoto (right) in the mid-1980s. Courtesy: NHK

Left: A young Shigeru Miyamoto works at his desk at the 60 Kamitakamatsu-cho complex in the mid-1980s. Right: Masayuki Uemura, the designer of the Nintendo Entertainment System (left) and game designer Shigeru Miyamoto (right) in the mid-1980s. Courtesy: NHKHaving traveled across Hyrule as part of the quest in The Legend of Zelda, it seems these fans have been inspired to go on a similar pilgrimage to Kyoto, to the origin of their enthusiasm. Instead of talking to townspeople they talk to train station attendants and ask for directions that lead them to the white block towers of Nintendo’s buildings in the city. Along with that same sense of adventure, game players seek a connection with companies like Nintendo to display appreciation, gratitude, and take in the same physical environment that hosted and informed the games they play, hoping to be inspired in some way. However, there may not be anything left to visit or view, the kicker being that the absence of a museum or archive means their arrival probably wasn’t ever considered. Just as Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, California has plaques hanging on each of its soundstages listing the motion pictures and TV shows filmed there, game development offices hold a somewhat similar allure, albeit without the official recognition.

The big difference between film and game companies is that the latter don’t need soundstages and backlots to produce games, they just need technology, efficiency, as well as secrecy to stay ahead of competitors. It’s upholding these tenets that encouraged many Japanese videogame companies to recently sell off old real estate and bring their operations under a single roof, with all the modernizations they required. Notably, this is a contrast to the structure they adopted during the 80s and 90s, which saw some Japanese game developers, handling both consumer and coin-op game production, opting to spread out operations across different buildings. Some operational structures even had game development, sales, marketing, and distribution spread across different cities for various reasons. The shake-up to this system has been caused by big, often unexpected changes across many Japanese game makers in recent years. Several small studios have been hit by bankruptcy that led to their closure. And larger development houses and publishers have seen a dramatic shift in operations—not just Nintendo. Many have sold off property in other areas of Japan in order to focus their efforts in Tokyo and Osaka.

Fans have been inspired to go on a similar pilgrimage to Kyoto, to the origin of their enthusiasm

The obvious reason for this shift would be to raise cash to acquire new real estate. It also serves to keep up-to-date with Japanese building standards in a country vulnerable to earthquakes. But there’s more to it. In the transition to digital, retail disc assembly isn’t required to as large an extent as it once was, eliminating the need for warehouse space to store inventory. Coin-op game development is not what it once used to be, either. Factories and plants utilized to build game cabinets in the downsized coin-op market can be closed with the logistical work outsourced entirely. Some would argue that certain buildings destined for demolition are relics from decades-past, eyesores from the interior to exterior, and do not reflect an industry that’s all about moving forward. This may be why numerous game companies are not holding on to old real-estate. But in doing so they deny any possibility of turning these properties into corporate archive or museum facilities. Those on the other side of the debate see this as a depressing state of affairs given that a part of both a company’s and videogaming’s legacy practically vanishes as a result.

///

Taito, Konami, and Sega are Japanese game companies that share one thing in common: very early in their business operations they were selling jukeboxes in Japan in addition to videogames. Sega also manufactured slot and pinball machines in Japan in its infancy. Namco once produced mechanical rocking-horse rides with Disney characters on them in the late 1960s, and also distributed Atari arcade games in Japan starting in the mid-70s. The entire inventory of all amusement and consumer gaming items manufactured by these four companies combined over the past several decades is enormous.

What doesn’t end up stored in warehouses is sold off to buyers, or discovered by collectors. And what isn’t discovered is left outside for trash collectors to pick up and toss into a landfill. Anything that breaks and is considered irreparable is trashed by arcade operators or distributors that may deem the work a waste of time, effort, and money. The entertainment these games provide is considered short-term by them, and each year countless replacements for this entertainment are presented to the marketplace—that is their protocol. No such protocol exists among the gaming industry for cataloging game assets and it’s an issue rarely discussed at industry events, if at all.

The former headquarters of Bandai Namco Games since May 2007, the company has since sold and moved off the property. The building will be demolished for a residential complex. Courtesy: Google Maps

The former headquarters of Bandai Namco Games since May 2007, the company has since sold and moved off the property. The building will be demolished for a residential complex. Courtesy: Google MapsWhen videogame development buildings are demolished, the mystery remains about what is deemed important to keep and what is thrown out in the trash and who is put in charge of making these decisions. From design documents, marketing materials, artwork, source code, music files, ROMs, circuit boards, spare components, contracts, legal documents—the responsibility and work that would go into organizing all of this is extensive and comes at a cost. It’s unclear if game companies can afford warehouse space, security, and personnel on staff to keep archived games catalogued and in working order. If these can be considered worthwhile operating costs is currently in question. Certain pieces of Taito, Konami, and Sega real-estate owned for decades by each of these game companies in Japan has already been sold off, some of these buildings that once sat on these properties have been demolished. What’s clear is that the opportunity to turn these properties into an archive or museum vanishes with the buildings themselves.

///

Last year, Konami sold off the downtown Sapporo nine-floor high-rise—which was once the long-time headquarters of its Hudson Soft subsidiary—taking with it the famous Hudson Soft bee mascot that once sat atop its entrance awning. The legacy that Hudson Soft built, which included such titles as Bomberman (1983), Adventure Island (1986), Bonk’s Adventure (1989), and Bloody Roar (1997) disappeared from the snowy island of Sapporo where the company originally began in 1973. Konami would however make headlines in 2013 by purchasing an old hotel and theater complex in the Ginza district of Tokyo for a reported 17.8 billion Yen ($222.5 million USD), demolishing it to make way for a new complex tentatively named “Konami Creative Center Ginza.” In statements made to the press, Konami said it intends to use the facility for the production of new content and “intends for it to be a hub for production of its content and for communication between the Konami Group and its customers.” Konami declined to comment on its completion date nor elaborate on what type of production (videogames or casino gaming) it would be used for. The building is currently under construction.

What doesn’t end up stored in warehouses is sold off to buyers, or discovered by collectors

In 2013 Sega sold off its five-story headquarters annex across the street from Sega Haneda Buildings 1&2, still sitting on land that Sega established itself on over five decades ago in Tokyo’s Ota-ku ward. The building maintained a towering neon sign of the Sega logo for decades and was sold off and demolished to make way for a new apartment building. That same year, Sega also sold off Sega Building 3, a complex once home to its internal development teams AM2, Hitmaker, Sega Rosso, Amusement Vision, and WOW Entertainment. The building, once the headquarters of AKAI (before Sega acquired it in 1996), was just a 10-minute walk from Sega’s Haneda Building 1&2. It was demolished and will reportedly make way for a furniture superstore. Sega’s Haneda 1 and 2 buildings are still in use and are now occupied by Sega Games (its mobile, PC and home console game division) and Sega Interactive (its coin-op amusement division).

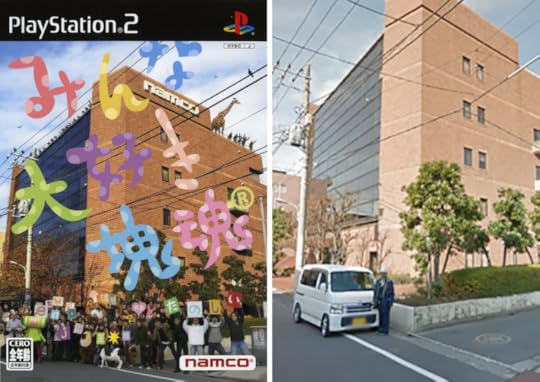

BANDAI NAMCO Games moved into a new 13-story high-rise building this year in the Minato ward of Tokyo, leaving its famous trapezoid-shaped eight-floor office that it once occupied in Shinagawa since May 2007—it will be demolished for a 19-story apartment building. Their Shinagawa building lobby once prominently displayed their legacy of arcade cabinets ranging from Pac-Man (1980), Xevious (1982), and Tekken (1997). In the process of bringing operations into a single complex, four of Namco’s Ota-ku Tokyo branch offices originally built in the 1980s were sold off, and some were demolished. One of these buildings was nicknamed “Xevious” because the profits from its Nintendo Famicom release helped fund its construction. Its most recent Ota-ku office departure took place in September 2014 when Namco moved out of its Yaguchi office that was once prominently featured on the Japanese cover of “We Love Katamari.” Namco’s Yaguchi office was built in 1985 and previously served as Namco’s long-time headquarters.

Namco’s former headquarters building, established in 1985, was vacated by BANDAI NAMCO recently. It made a prominent appearance on the Japanese cover of “We Love Katamari.” Courtesy: Moby Games and Google Maps

Namco’s former headquarters building, established in 1985, was vacated by BANDAI NAMCO recently. It made a prominent appearance on the Japanese cover of “We Love Katamari.” Courtesy: Moby Games and Google MapsIt hasn’t all been about expansion, some Japanese game companies have, in fact, opened their doors to welcome game players into shops on company property (similar to Nintendo New York), even lending company buildings and games to museums and exhibits. While they are not specifically corporate museums or archives, they are a step in the right direction, moving towards opening up to the public to a certain degree.

Square Enix sold off its Hatsudai Building last year, which was formerly the headquarters of ENIX itself (built in 1996), before its merger with Square. The Hatsudai Building once famously housed a Square Enix Character Goods Shop open to the public on its first floor. Square Enix moved into the Shinjuku Eastside Square with subsidiary Taito Corporation in 2012 occupying several floors. Square Enix also opened an all new character goods, shop, café, and bar area named ARTNIA on the ground floor of Shinjuku Eastside Square complete with souvenirs and limited-edition items. The company calls ARTNIA “an area that serves as a bridge between our goods and our customers.”

Videogames have solidified themselves as part in the lives of players

Taito Corporation closed its Ebina Development Center and factory in 2014, the site was originally established in 1979 within Kanagawa Prefecture in the midst of the Space Invaders (1978) craze. It was here that cabinets for countless coin-operated games from Darius (1986) to Chase H.Q. (1988) were manufactured, it also served as development offices for numerous games. Another Taito building where consumer and coin-op development occurred for many years in Yokohama, known as the Taito Central Research and Development Laboratory, was also demolished in 2014. The building was reportedly unoccupied for a number of years before the demolition occurred. Taito does provide help to the game museum sector in Japan. Taito currently lends its warehouse and former development office in Saitama prefecture, known as the Taito Kumagai Building, to a game museum that showcases arcade cabinets on a regular basis.

///

Videogames have solidified themselves as part in the lives of players and are passed on to new generations. However, they still struggle to be taken seriously by governments, educators, and those that would dismiss them as harmful, unhealthy, and a waste of time. Walking into a corporate museum to experience the personal storytelling of the design, artistry, and engineering that goes into game design could educate these critics on the value of videogames while further engaging those that already enjoy them.

The former headquarters of Enix absorbed by the Square Enix merger (left), the building was recently sold off to another company. Square Enix now partially occupies a new building complete with a company store called ARTNIA on the ground floor. Courtesy: Google Maps

The former headquarters of Enix absorbed by the Square Enix merger (left), the building was recently sold off to another company. Square Enix now partially occupies a new building complete with a company store called ARTNIA on the ground floor. Courtesy: Google MapsMuch of the game development work produced in these demolished buildings continues to be a mystery to game audiences in and outside Japan. Some can often take the end product that’s developed and the effort that went into it for granted. On occasion, during interviews, game designers and programmers will tell stories of the places they worked in, the camaraderie they shared with co-workers, and the numerous challenges, both personal and technical, they faced during development. These game development operations were places where countless game designers, programmers, and engineers worked endless hours creating games that went on to be played for years and still are today. They are a part of our culture, bringing people together, and some have an inspirational meaning to individuals. What future generations of game players and creators can learn from them is invaluable.

Whether or not the game industry is open to putting their interactive legacies on display to a personal audience of game players, aspiring game designers and visiting tourists is now in question. Time will tell if game industry real-estate can be turned into museums or archives and if the game industry, game players, and the general public are ready to support it.

Header image: The Sega Annex Building, an office that had been a part of Sega for decades with its enormous signage, was recently demolished for a residential building. Courtesy of Twitter user: @t_arai2012

New technology lets anyone control Donald Trump’s face

If given the opportunity, what would you do to the melted clump of leftover Kraft Dinner that is Donald Trump’s visage? While this is surely a question with which much of the electorate has recently reckoned in a hypothetical sense, technology is making it tantalizingly real.

Let’s start with the serious application: “Face2Face” takes a YouTube video and re-renders the face in real-time to match the movements of another person as captured by a webcam. The project, which was created by researchers at Stanford, the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, and the Max Planck Institute for Informatics, turns real people into puppets. Their faces can be deformed with remarkable ease. That isn’t what it looks like—we expect deformation to smudge shapes—but all movement is deformation, and in “Face2Face” that logic is followed through to its ultimate conclusion. Thus, this can be done to Donald Trump’s face:

What does it take to make deformation look like gentle transformation? Lots of facial tracking technology, obviously, and plenty of fancy rendering. But the most interesting tidbit about “Face2Face” is that “The mouth interior that best matches the re-targeted expression is retrieved from the target sequence and warped to produce an accurate fit.” One might not immediately think the interior of the mouth is particularly consequential when it comes to facial matching, but these are the little details that can easily derail a work of animation into the uncanny valley. “Face2Face” doesn’t fall into that trap, so we can now worry about how it’ll be used to ruin political discourse.

Or maybe political discourse is already dead. Maybe there are no words left to be placed in the mouths of politicians, save perhaps for “sorry.” For those with that outlook on the current political climate, there’s Drumpulous, a game where you follow Donald Trump (Drumpf?) and fire dildos of various colors and sizes at The Donald’s head.

Why is this a thing? “I am chilled to the core watching trump’s rise in popularity and working on this was cathartic for me,” Drumpulous’ creator explains. “I hope it brings a lighthearted moment to anyone also suffering from dread in these troubling times.” Fair enough, at least up to a point. Watching the rise of Donald Trump has been nothing if not infuriating, and the constant, asymmetric demands that his detractors behave with levels of civility that The Donald never meets is exhausting. (Here’s looking at you, Jonathan Chait.) So, who could begrudge Drumpulous’ creator and players a little laugh? It is indeed funny to watch cartoon-Trump’s head rock back and forth as dildos collide with its squared-off corners.

Drumpulous might indeed be funny if it did not have sound. But it does, and it turns out that a gun that shoots dildos sounds just like a gun. The projectiles aren’t even launched with the light thoompf of a nerf gun. They leave the chamber with the concussive sounds of real projectiles. Drumpulous is a shooting fantasy dressed up with dicks as moral cover. It’s not a work of sociopathic violence or anything worth alerting authorities over, but it’s also not just a joke about Donald Trump and dildos.

We’ve been here before with Trumpiñata. Games provide an outlet for political frustrations, and that’s for the best. It’s better to have slightly violent jokes in virtual spaces than elsewhere. Online spaces also allow citizens to escape demands for civility in the privacy of their own homes, which is psychically and practically useful. That does not, however, fully excuse the Beat-Up-Politician-X genre, which never seems to have sufficiently reckoned with the power of its iconography. These games will be looked back on as interesting cultural artefacts, but probably not as wholly thought-out pieces of commentary.

How virtual reality reinvents party games

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Though virtual reality can be an immersive, solitary experience, multiplayer games are bringing people together for a new kind of group fun. With all the enthusiasm and excitement surrounding virtual reality (VR) games this year, it makes sense to expect some partying. After all, huddling around the TV with a group of friends to play Mario Party—or transforming the living room into a makeshift concert hall with Rock Band—remain marquee gaming moments for gamer groups.

Yet these types of party games seem to fly in the face of the head-mounted displays of VR, which appear to isolate players in immersive yet solitary experiences. Inviting the gang over to goof around and play games seems almost contrarian to the very concept of VR as a means of transporting the sole user to far-off digital worlds. But VR knows how to have a good time, too. In fact, some of the most promising VR games could be as fun as epic Guitar Hero group battles on beer-and-pizza night.

VR is fertile ground for positive social experiences with real-life family and non-Internet friends, according to Intel’s VR Evangelist, Kim Pallister. “There will be people doing things that are social in the Nintendo sense of the word, in which you are in the same room or sitting on the same couch,” Pallister said. “I’m very confident that lots of indie developers will think of interesting twists to that scenario.”

Some already have. Fantastic Contraption, a launch title for HTC Vive, tasks players with going under the mask to construct whimsical virtual machines while their friends jeer and cheer for them. The game gives players the impression that they’re performers entertaining an audience—an experience that’s a cross between a game of charades and a French mime. Sony’s eye-popping mini-game Monster Escape takes an alternative approach. Here, it’s four against one, with colorful little robots taking on a single yellow, squeaky, VR-outfitted dinosaur.

VR is fertile ground for positive social experiences

Still, the best of the bunch may be the 2016 Independent Game Festival Grand Prize finalist Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes. This one requires people outside the VR headset to relay instructions to a person who is inside VR trying to defuse a bomb. The game essentially casts players as the star and co-stars of their own James Bond film.

Actually, Brian Fetter, one of three developers at Steel Crate Games, explained that the team was inspired by an episode of the master spy spoof animated series Archer. In the episode, the titular and notoriously bumbling hero is on a blimp trying to defuse a bomb but has a communication breakdown with headquarters. “It’s M as in Mancy,” Archer blunders before making the ticking time bomb speed faster toward detonation. “That’s what we wanted to go for,” Fetter said.

Aside from living out the fantasy of being an international super spy, the purpose of the multiplayer in Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes is to get everyone in on VR fun. “It’s not likely there are going to be five headsets at a party, so we started thinking about how we could make a game that only involved one,” Fetter said. The team first encountered this design obstacle for multiplayer VR experiences at the 2014 Global Game Jam (which asks designers to create a game in only 48 hours). It turned out they were one of the only groups who brought an Oculus Rift development kit to the jam.

Because there weren’t many kits in circulation at all back then, the other programmers and game jammers were antsy to take it for a spin. This prompted Fetter and his team to share the experience by setting up a kiosk for others to use. Before they knew it, a line had formed. They thought, “Wouldn’t it be cool to have everyone involved in some way instead of waiting?” Before they could say “virtual reality party,” Nobody Explodes was born.

get everyone in on VR fun

They discovered that this evolution of the digital party game had the unintended benefit of making people who were totally uninterested in VR suddenly very curious. “We didn’t design it as an introductory game to VR,” Fetter said, “Later on, we saw it as a gateway.” The design of Nobody Explodes invites those who might feel intimidated by the newness of VR to play as the assistants who communicate the instructions to the bomb defuser. After seeing how much fun the plugged-in player can have, their uncertainties quickly wash away. Without even realizing, naysayers catch the VR bug themselves.

Titles like Nobody Explodes and Fantastic Contraption don’t just give a sneak peek of an evolution in game nights. Aside from getting friends together, the game also acts as a bridge for those who want to explore VR while keeping one foot firmly in the physical world. Light multiplayer games like that might be exactly what VR needs in order to woo early adopters. As Pallister explained, one of the big challenges is getting around “this awkward head-mounted display thing.”

“You can’t put it in a commercial,” he continued. “You can’t show a screenshot. If you really want to see [what it’s like], you have to put it on your head.” Luckily, after one person gets in on the fun by wearing the headset, it’ll be hard for the others to resist a party.

Practice your improv in this videogame theater

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Commedia del’Arte (PC, Mac)

A COLLABORATION BETWEEN STUDENTS AT THE ENJMIN AND EMCA SCHOOLS

Surprisingly, improv is about more than Amy Poehler making fart jokes. At the heart of great improv is a sense of play. Though it’s controlled and focused, emergent play defines improv as much as it defines games like The Sims, where players (or actors) are encouraged to go to town within the confines of a defined possibility space. Commedia dell’Arte: Masks, Masters and Servants marries the play of improv with the play of videogames into a point and click stage play. You are a young comedian in Italy at the height of the 16th century, and the crowd has come to love your buffoonery. You can interact and influence each show with a myriad of responses, from scaring your fellow thespians with props, to verbally abusing them with dialogue choices. The stage is your oyster!

Perfect for: Actors, members of the Upright Citizens Brigade, Ezio Auditore

Playtime: Ten minutes

Samorost 3 is the best adventure game in years

In a cabin near Walker’s Lake, in Mississippi, there’s a piece of driftwood that looks almost like a wolf’s head. From another angle, it appears as some bizarre sailing vessel, and from another still, it has the look of an alien weapon—perhaps a hybrid of a gun and a club. I remember turning it over in my hands as a child, curious as to why anyone would place an oddly-shaped piece of wood on a table as a decorative object. I hadn’t thought of that bit of ornamental flotsam for years, but it suddenly appeared in my mind when I began playing Samorost 3. The various planetoids that drift through the game’s version of outer space have the asymmetrical appearance of organic junk, decaying stumps and moss-claimed stones infused with extraordinary life to unlock their inherent aesthetic potential.

The most ambitious project yet from Jakub Dvorsky and the team at Amanita Design (which gets its name from a genus of mushrooms known for toxic and hallucinogenic properties), Samorost 3 bears the markings of a creative mind fascinated with unlocking the art behind man-made and natural throwaways. Even the title of the Samorost series points to Dvorsky’s curiosity with the peculiar shapes of the natural world. In a 2005 interview, Dvorsky stated that the title “samorost” is a Czech word that means “a root or piece of wood which resembles a creature; but it is also a term for a person who doesn’t care about the rest of the world.” Appropriately, both Samorost (2003) and Samorost 2 (2005) follow the adventures of a space-faring gnome as he travels to worlds of overgrown wood and rusted metal. A blend of manipulated photography and hand-drawn environments play host to bizarre and charming characters, all moving to the tunes of equally imaginative soundscapes.

Amanita’s most recent titles, Machinarium (2009) and Botanicula (2012), split this aesthetic blend of found object and organic material by designing worlds solely out of junkyard scrap for the former, and an enormous tree for the latter. Samorost 3, however, returns to the previous art design of blending the natural and technological worlds to construct fascinating environments hewn from broken stones and overgrown forests commixed with discarded bits of trash and rusted metal. Such a style finds a delightful playfulness by blending found object art, like the “ready-mades” of Marcel Duchamp, with the surrealist landscapes and creatures of Max Ernst. The world of Samorost 3 is, quite plainly, unlike any other I’ve encountered.

The world of Samorost 3 is, quite plainly, unlike any other I’ve encountered

The game begins simply enough with the gnome wandering around his own planetoid, his house a tower with a telescope through which he can gaze up at other planets and their orbiting satellites. Without exposition or dialogue, the player understands that mere curiosity sets the gnome on his quest for other worlds, and only by helping him build his rocket ship (from a living mushroom, a rusted panel, a bathtub, and plastic bottle) can he set off to explore the stars. This humble introduction equates the gnome’s wanderlust with the player’s own inquisitiveness, and, consequently, embraces one of the fundamental pleasures of videogames: simple exploration.

In fact, “simple” seems to be one of the driving philosophies behind Samorost 3’s design. Like most adventure games of its type, Samorost 3 strips the “point-and-click” template to its core without succumbing to cold, mechanical repetition. Solving puzzles mostly involves clicking objects in the environment in the correct order, but the reactions from the characters and movement of the environment after being prodded make the game stir with life. Poking and disturbing the bizarre inhabitants of Samorost 3 causes them to react in ways that seem unpredictable, until repeated clicks uncover hidden rhythms that connect them to their world in ways that feel organic. Moving cattails near a pond causes nearby reptiles to strike up a chorus, and tapping busy termites halts their work for a quick song of praise to their patron saint. Completing such puzzles, then, is of secondary importance to engaging with them. In a game about the virtues of curiosity and exploration, the act of clicking becomes a tool for observational science replete with wonder, constantly poking at the world to see how it reacts in unexpected ways.

That sense of discovery makes playing Samorost 3 feel far less like an adventure game and more like a naturalist’s excursion, documenting foreign flora and fauna to better understand the complex universe they inhabit. Helping a forager pick mushrooms, participating in a polite yet informal tea ceremony, feeding a giant anteater, and helping numerous creatures find the right tunes to sing; all inform a profound experience of that world. All of these characters move like incredibly-detailed cut-out puppets gliding across painted landscapes, each visual piece complementing the game’s commitment to straightforward storytelling without the tedium of exposition. A gesture from a hungry parrot tells the player it needs food. Subterranean gremlins covered in soot bounce anxiously, revealing that they need the right tune to work in sync. The game asks for the player’s attention instead of demanding it through the use of such subtle cues that I rarely found myself at a loss for what to do.

Even those moments that halted progress were more like opportunities to wander around the world than barriers obstructing play. While there is an overarching quest involving a selfish monk who wreaks havoc across these small planets, the gnome more locally acts as a naturalist studying foreign places. His motivation rarely extends beyond curiosity, and the various environments, creatures, and characters seem mostly indifferent to his existence. Any positive or negative effects on the world are mostly incidental. He looks at the world with a sincere desire to learn about it, turning over stones and toying with strange devices only to see what happens.

The result is a game that is endlessly charming. In playing Samorost 3, I’m not compelled to be the hero, nor am I tasked with solving difficult puzzles for any sort of self-satisfaction. The game asks something far more humble of me: my desire to experience another world. After I completed what seemed to be the main quest, the game rewarded the gnome (and by extension myself) with the ability to travel more easily among the small planets and their satellites. In other words, the prize for playing Samorost 3 is simply more Samorost 3.

It seems an appropriate reward because I’m not yet done with Samorost 3. I hope I never am. Even if I somehow uncover every secret, wander through every niche of that world, I’ll still probably come back to it if only to toy around with the sights and sounds of a natural world waiting to divulge its secrets to the patient and curious observer. Maybe the best way to play Samorost 3 is to play with it, to think of it as a bizarrely-shaped thing that prompts one to appreciate the ways oddities can spark and delight the imagination. At least that’s the way I’ll continue to play it, curiously wandering through alien environments, turning each sight and sound over and over in my head, very much like I once did with a strange piece of wood I encountered when I was young.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers