Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 140

April 5, 2016

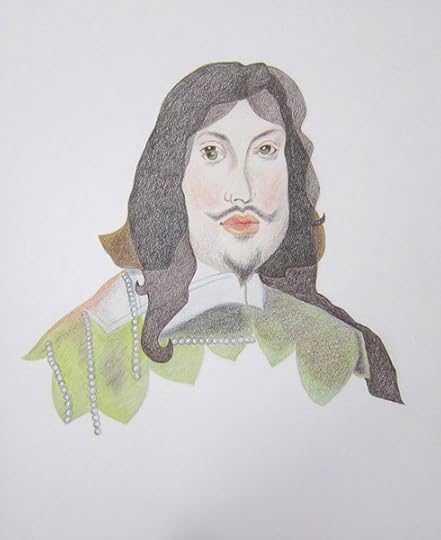

Degraded portraits of royals reflect their obsessive inbreeding

It is commonly known that the in-marrying of families was an aristocratic trait used to ensure the purity of a monarchy or empire’s bloodline. Unlike the infamous incestuous relationship between Cersei and Jaime Lannister in Game of Thrones, these relationships held significant political power, and weren’t considered subversive, but rather the norm. Michelle Vaughan explores this idea through the Spanish-Austrian Habsburg royal family in the exhibition Generations.

the idea of degradation through the pursuit of improvement

In these works, Vaughan works conceptually with the idea of degradation through the pursuit of improvement. Hyperallergic likens this, aesthetically, to our modern pursuit of perfecting digital images, and in the process, losing touch with the original image. Whether it be compression of an image through over-saving, or sharpening to the point of pixelation, we are often familiar with this idea of accidental degradation without realizing it. Anyone who has spent a large portion of time editing images is likely to know how, the longer one works with an image, the harder it is to tell whether the image is indeed looking better or worse.

Vaughan uses archival images and manipulates them to highlight the similarities between the Habsburg line. In doing so, the seeming absurdity of this historic lineage and practice shines through. Indeed, Vaughan mentions how the similarities among the Habsburgs has meant that art historians often cannot tell them apart. From this perspective, the absurdity of both the historic, and our attempts to legitimately study it from our own context in an objective way, comes to the fore.

Through adapting archival prints into GIFs , and then using these as reference points, Vaughan duplicates the images in colored pencil. Through this duplication and manipulation of the archival, the process of portraiture and how portraits were made, reproduced, and distributed is mirrored. Historically, this was a means of affirming the legitimacy of the royal family’s rule and marriages in an aesthetic way. Vaughan’s artistic process appropriates this for the inverted means of undermining that legitimacy. Which is only fitting, since this strategy of in-marrying was the very thing that lead to the extinction of this royal line.

You can learn more about the exhibition on Theodore:Art‘s website, and follow Michelle Vaughan on Twitter.

Panama Papers newsgame teaches you how the rich evade tax

Let’s say you’ve just come into some money. Maybe you earned it through your labors. Maybe you didn’t—no need to get bogged down in the details. Anyhow, you have this money. Now what?

A series of choices present themselves, which is to say that this situation has the makings of a game. Well, at least it has the makings of an interesting game so long as you don’t choose to disclose your wealth at every possible turn. Should you choose to do that, things will end quickly and with little excitement. But humans are not always that moral—at least not all the time—so a game can work.

The game in question is Stairway to Tax Heaven. It’s a newsgame published by the Toronto Star as part of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The subtext of this game is the release of the Panama Papers, a massive leak from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca that reveals the extent to which the global elite has gone to hide its money. Coverage of the 11.5 million files has so far identified 214,000 offshore companies linked to individuals in over 200 nations. Iceland’s prime minister, the father of British Prime Minister David Cameron, and soccer star Lionel Messi have all been implicated. They are hardly alone in that regard.

the real game in Stairway to Tax Heaven is not the one created by the Star

Stairway to Tax Heaven is effectively an interactive version of Fusion’s infographic explaining the workings of shell companies. You select a territory with a history of secrecy, appoint shady intermediaries, give your new company an anodyne name, and if all has gone according to plan you have hidden your wealth. (It should be noted that not all of the actions revealed in the Panama Papers are illegal.) Stairway to Tax Heaven is not a particularly challenging (dare I say taxing?) game. The moves that lead you to tax evasion or a shell company are heavily telegraphed; just pick the least transparent option at every turn. It really is that simple.

Austurvöllur er fullur #panamapapers #cashljós pic.twitter.com/h5TF7Nl4Gk

— Hjörtur Jóhann Jónss (@HjorturJohann) April 4, 2016

In reality, hiding all your money isn’t so simple. That’s how law firms like Mossack Fonseca make their money. Obscurity is possible, but it is not easily accessible. In light of this latest leak, however, we must consider that obscurantism is still too easily accessible. In that respect, the real game in Stairway to Tax Heaven is not the one created by the Star, but the underlying financial systems. Rules create strange choices at the margins, which can be manipulated by those with the will—and resources—to do so. That doesn’t mean that tighter financial regulations are not desirable, but it is a game where both sides are trying to outmaneuver one another. If nothing else, 40 years of documents from Mossack Fonseca show just how hard it is to make the rules of the game work for everyone.

Development of Papers, Please creator’s next game hits rough seas

It’s been a year and a half since Papers Please (2013) creator Lucas Pope first announced his nautical mystery game Return of the Obra Dinn, releasing a small demo of the game for players to try for free. Like many demos, it offered a vertical slice of the game’s typical routine, helping to embody what the full game might eventually look like as a whole. However, while working on a new demo to show at this year’s GDC, Pope found that his original vertical slice “did not scale up (at all) to making a full game.” As such, he’s taken to his devlog to give readers an honest, firsthand experience at some of the unexpected difficulties creators come across while making games.

“Something that bothered me during this 1.5 months of democrunch was just how much fucking work I was doing just to get back to the level of functionality the old development build had, 1.5 years ago,” he writes. “This is something I’ve experienced before – kicking out a solid vertical slice in X months, then breaking everything badly while scaling up the tools/pipeline/systems for the full game.”

A before/after shot of the game’s upper deck

Pope explains that, since beginning work on the full title, the tools he used to build the demo haven’t held up to the increased needs of the full project. New game features wouldn’t work with old programs, he had to write a new lighting engine from scratch, he needed to purchase an upgrade to his animation software, and “a lot of random stuff broke.” As he explains, “The current GDC demo isn’t clearly 1.5 years better than the old development build.”

Still, for Pope, his difficulty with tools was simply emblematic of a larger problem. “Looking back at all these problems, it’s easy to blame the tools I’m working with,” he writes. “But I think the real issue is just with how I build games.” According to Pope, while it tends to be easier to avoid these problems by building games with a clear plan in place first, he prefers to work in a looser style, tweaking and redesigning aspects of the game as he builds them. “There’ve been several times when I sat down and said: ‘ok, plot out the whole game so I know what to build,’” he explains. “Only to give up and go back to noodling on some small thing.”

the real issue is just with how I build games

Despite this, the results of his work still show marked improvement over the original. The ship the game takes place on now has full masts and sails, complete with movement in response to wind and other environmental factors. The ocean is fully animated. The characters are now wearing clothing rather than having it built into their models. He’s even added in multiple color schemes meant to pay homage to different one-bit computers, expanding the game beyond the black and white of the original build.

For all the difficulty Pope’s encountered, Obra Dinn seems to have only grown since we’ve last seen it, even if it’s pulling into port a bit late. Pope is currently busy fixing one last graphical issue with the GDC demo, after which he plans to release to the public. Until then, you can follow Pope’s work over on his website, and read Pope’s devlog here.

Salt and Sanctuary has soul

Salt is an essential part of our biology. It helps regulate fluid balance between cells. Our entire system of nerves and muscles is designed around the special electrochemical properties of salt. Too much salt and we die. Too little salt and we die. It’s the perfect metaphor for the kind of complex equilibrium Salt and Sanctuary likes to brutally enforce. Get too aggressive and you die. Give into cautious hesitation and you die. Learn to navigate the invisible rhythms in-between these two extremes, though, and something beautiful happens.

It’s a construct familiar to anyone who’s subjected themselves to the punishing specificity of a FromSoftware game. This is why it’s impossible to talk about Ska Studios’ Salt and Sanctuary without mentioning the Souls series. But it’s also unfortunate, because comparisons like this are more likely to bury the former under a pile of decomposing clichés than unearth its unique merits.

Yes, Salt and Sanctuary treats salt like a currency that can be collected from enemies and invested in leveling up or weapon upgrades. And yes, you can lose all your salt for good if you die in the field and are unable to collect your remains before dying again. Players can choose from a number of classes, ranging from vanilla fighters to poison-immune chefs, but a sprawling skill tree lets them customize their character from there. Most Souls-ian of all, every action is constrained by a stamina bar which, though it can be expanded over the course of the game, is always finite.

Calling Salt and Sanctuary a 2D Souls game, however, is like saying a map is just a picture of reality if it were in two-dimensions instead of three. That people spent centuries debating whether the Earth was flat offers some indication that the problem is more complex. As a gothic, side-scrolling brawler, Salt and Sanctuary relies on the friction of blood and bones in compact spaces to create forward momentum. Propelling the player up and down a series of bi-directional boulevards, the game owes more to SNES-era platformers than FromSoftware’s recent empire of action-RPGs.

Loosely tasked with finding a princess so that her marriage to a prince can cement peace throughout the land, Salt and Sanctuary begins in earnest when you awaken on a color-drained beach with only one way forward. Like the beginning of Playdead’s Limbo (2010), the game feeds off the player’s instinct to scroll from left to right across the screen with her bewildered avatar. Contrary to the taunting aimlessness of Souls, Salt and Sanctuary is urgent and direct.

the savage violence moves beyond life and death to take on a vivacious quality

It’s less interested in meticulously deconstructing the player, one deathblow at a time, instead reveling in its crunchy sound effects and scintillating blood splatters. Mutant blobs that try to suffocate you explode once you break free. Flames pour out of the necks of Hyena-looking reptiles when you decapitate them. Bones crackle and hiss whenever you smash something that looks even remotely like it might have a spine. Knock an enemy down and rush to its side fast enough, and the game will prompt you to curbstomp the remaining life out of it.

These aesthetic flourishes are what tie the game together and make it feel so bouncy and full of life despite its macabre trappings. The desperation of my grizzly, white-haired sorcerer as he dodged and hewed his way across the screen became a source of inspiration rather than soul-crushing fatalism. In two dimensions, the contours of a hitbox are laid bare, and the enemy’s tells have nowhere to hide. By abstracting reality and rendering it more pure and cartoonish, the savage violence moves beyond life and death to take on a vivacious quality.

The common Souls encounter has the feel of two entities wrestling in the mud to see who can extinguish the other first. Understated given the stakes, it has all the charm of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Valhalla Rising (2009), which is to say none. Refn’s viking pilgrims know only the hell of Dark Ages Europe and its daily immiserations of the flesh. What they lack in charm, however, they make up for in the pity they provoke when confronted with a life that’s nasty, brutish, and short. Salt and Sanctuary instead captures the driving force of Gareth Evans more jubilant The Raid: Redemption (2011). Death at the bottom of the apartment block is not the same as death at the top or beyond, providing the film with a clear trajectory, both moral and physical, against which to measure progress. When Evans stages a scrum between gang members and swat officers, its fury and delight is underlined by clear objectives rather than sadistic absurdities. Salt and Sanctuary is content to teach you how to move through hell without the need to torture while you search for the exits.

The game’s use of “brands,” platforming abilities bestowed by NPCs dispersed throughout the world, show Salt and Sanctuary’s substantively different focus as well. Beginning with a vertigo brand that allows the player to flip gravity at specific points and walk along the ceiling, each one offers a new way to traverse the game’s labyrinth and access previously gated areas. With many of them doubling as combat maneuvers, like a wall jump and air dash, the player’s relationship to the world around her becomes deeper and more intimate.

What begins as a weighty trudge through the festering underbelly of dark forests and abandoned keeps slowly evolves, growing lighter and more nuanced and intuitive. The overall effect is one of relief and, eventually, transcendence. Instead of surviving Salt and Sanctuary’s horrors by obsessively dissecting them, liberation comes as a result of being able to execute ever more deft acrobatics with a few simple twitches. In this way, the game helps us learn to shed the burden of realism by flattening it, reducing its physical and emotional details into obstacles that can be overcome with the flick of a button.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

April 4, 2016

An appreciation of Zaha Hadid, modern architecture’s greatest woman

The architect Zaha Hadid, who died in Miami last Thursday at the age of 65, was one of design’s great optimists.

Only an optimist could dream up the billowing curves of Azerbaijan’s Heydar Aliyev Center, which sprout from the ground, rise like sine curves, and blend into one another without ever meeting at right angles, and think “Yes, this building can live unburdened by earth’s gravity.” Only an optimistic could spend decades drawing fantastical jagged futurescapes—impressive works of art in their own right—while breaking ground on precious few projects. Only an optimist, one imagines, could make headway in a male-dominated field with an unfortunate history of erasing women’s contributions.

Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center — Photo by Francisco Anzola (Flickr)

Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center — Photo by Francisco Anzola (Flickr)But Hadid’s legacy is not attitudinal. It is physical. It is a deconstructionist fire station for the Vitra campus, a factory for BMW that transposed the machine-age musicality of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) into this millennium, and it’s a school in Brixton that wrapped over and around athletic fields. It is an aquatics stadium for the London Olympics that made concrete appear more welcoming and fluid than the water which swimmers launched themselves into. It is a series of cultural facilities spanning East Lansing, Rome, Guangzhou, and Dubai, each more improbable than the one that preceded it.

What does it take to get an ambitious building constructed in the 21st century? Money? Time? The right client? A permissive environment? All of the above, one supposes. That is the context in which starchitecture happens, which is to say Hadid was both famously uncompromising and compromised. Her Riverside Museum of Transport in Glasgow and MAXXI in Rome both cost dearly, while skyrocketing budgets were cited as causes for abandoning her plans for England’s Architecture Foundation and Tokyo’s Olympic Stadium. “Her argument,” Rowan Moore writes in The Guardian, “was that buildings are around for a long time, and it is therefore worth spending more on something exceptional.”

Other builds designed by Hadid that experienced issues include her curvy cultural center in Baku, which is named after Heydar Aliyev, who purged rivals during his KGB days before trending towards the autocratic in his post-Soviet days as Azerbaijan’s president. Aliyev’s son and successor, Ilham, championed Hadid’s project. But in 2012, Human Rights Watch alleged that the center was built on unlawfully expropriated land. Then there’s the more recent construction of Hadid’s Al Wakrah stadium for Qatar’s 2022 World Cup, which has infamously been plagued by controversies over labor conditions.

the first female and Muslim recipient of the Pritzker Prize

None of these faults were really unique to Hadid, though they were often described as such. Santiago Calatrava has proven just as proficient at running over budget. The likes of Norman Foster are all the more entangled with regimes that have questionable human rights records. Frank Ghery once gave critics the middle finger at a press conference, but the word “diva” followed Hadid instead. (It is here that I pause to note that Zaha Hadid was both the first female and Muslim recipient of the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s Oscar.) One might reasonably contend that elite architecture has devolved into little more than the creation of expensive, distant baubles that do little more than reify their own creators, but blame for that state of affairs ought be diffuse.

Hadid’s MAXXI gallery in Rome — Antonella Profeta (flickr)

Hadid’s MAXXI gallery in Rome — Antonella Profeta (flickr)It would, however, be unfair to simply say that Zaha Hadid embodied the values of her time. That formulation robs one of this century’s great architects of her agency. Zaha Hadid was a defining figure in architecture. Her work tested the very limits of science and materials. To watch other architects fall short with their swoops and swooshes is to see the unheralded brilliance of Zaha Hadid.

To merely decry the compromises inherent in Hadid’s work as naïve or cynical also denies the projects their underlying optimism. The MAXXI gallery and Guangzhou Opera House may have landed in their neighbourhoods like aliens from outer space with little sensitivity to the surrounding context (the latter design was originally pitched to Cardiff) but they were not hostile invaders. Hadid’s work embodied the optimistic belief that architecture could make places—including those with autocratic leaders—better. Her moral calculus may not have been beyond reproach, but she was not merely a cynic. The interpretive challenge for Hadid’s fans and detractors alike is to reckon with the sincerity of her work.

London Aquatics Centre — Artur Salisz (Flickr)

London Aquatics Centre — Artur Salisz (Flickr)Sixty-five is always too young an age at which to die, but it is all the more so for an architect. Hadid’s was not a profession where luminaries tend to peak early. Having spent much of the 1980s designing projects that never came to fruition, she ultimately died in her prime. Many of her projects, including a new parliament and central bank for her native Iraq, have yet to be completed. Whether these projects will substantially change how we feel about Hadid’s work is unknowable, but their looming arrival, like the existence of their precursors, is a source of optimism for architecture’s future.

LARP game has players cope with the expectations placed on different genders

It’s not hard to understand the appeal of LARPing (live-action role playing). A player can both cosplay and let go of their inhibitions in a safe space by acting out a character-driven narrative. Though I’ve never LARPed before, actress Felicia Day convinced me of its potential for sheer fun in an episode of Supernatural where her character got to be the Queen of a popular LARP and was practically worshiped by the other players. Definitely appealing. But perhaps the best aspect of LARPing is that it is a medium entirely shaped by its players backgrounds and intents, and can be used as a teaching method for players who wish to better understand the experience of the disenfranchised and marginalized.

Anna Kreider, creator of the game website Go Make Me a Sandwich, has created a LARP called Autonomy that seeks to do just that: her game not only allows its players to embody a character, but further allows them to eschew and transform gender roles entirely. The goal of the game, in forcing its players to swap gender performances as part of the game mechanics, is to give both men and women a little walk in each others’ shoes and hopefully become better acquainted with society’s expectations for both genders.

several players cried after the experience

The LARP was inspired by the 2012 U.S. House panel on contraception and religious liberty, where Kreider noticed the House relied on an nearly entirely-male panel of witnesses; the single female witness, Sandra Fluke, was forbidden from testifying about an issue specific to only women. Kreider believed a gender-based LARP could be a useful tool in understanding gendered experiences, and joked that if she could swap the players’ genders, the game could result in “hilariously misandrist entertainment.”

Her plan was successful to an extent, though the first playthrough of Autonomy wasn’t as hilarious as she’d hoped. As Kreider recalls on her website, several players cried after the experience, noting that they never wanted to experience being the opposite gender ever again; the players also acknowledged that the opposite gender didn’t have the option of halting the experience because it was their reality every day, which caused feelings of guilt and pain to run rampant throughout the group.

Autonomy consists of three separate phases: a workshop on gendered body language, a workshop on gendered speech, and finally, the actual roleplaying portion. At the same time, of course, the game depends on the players’ understanding of stereotypical gender roles in order for it to work; as Kreider notes, male players must assume “typically feminine posture and body language,” while its female players must learn to take up space and “perform masculinity.” While the LARP currently ignores trans and nonbinary identity, Kreider wishes to acknowledge these experiences in the future.

If you’re interested in playing Autonomy, simply pay-what-you-want for it here, and gather 6-9 players and an open mind.

Header image: Karikatur Album; by C. E. Jensen via Wikimedia

Installation reveals the game-like complexity of life on the Scottish isles

Off the Western coast of Scotland, the Hebrides are a set of islands somewhat removed from the mainland. Scottish Gaelic is most prevalent there, but the furthest island out appears to be named for a non-existent saint, while some get their names from Norse or even pre-Celtic languages. 1973 horror film The Wicker Man is set on a fictional island among the Hebrides, and so is The Chinese Room’s Dear Esther (2012). There’s a misty sense of uncertainty brought on by the distance between the far-flung islands, and by the fact that travel from one island to another has historically been dangerous.

the “piece starts to resemble a game”

The networks established by the locals on these islands, especially one of steamboats in the late 19th century, allowed for the development of robust inter-island communication and exchange, and are the inspiration for Simon Sloan’s new project Logistic. Logistic is presented as several 3D-printed islands on a set of monitors spread out like a map table. Boats, represented by lines, move across the screens from one island to the next. Sloane says that when a visitor moves the islands around and watches boats change their paths and interact according to his 32 rules, the “piece starts to resemble a game, the goal however is somewhat unknown. The rules are hidden.”

While active, Logistic produces a map not of places and spaces, but of relationships. In this case, economic relationships are represented through the transmission of “resources.” But the second characteristic of islands, “potential,” acts a kind of social capital, or importance: when a boat has no resources left it is converted into potential for the island it stops at, attracting more boats. Rule 21 dictates that “a boat will follow where previous boats have been,” but the higher the Potential and Resource values of an island, the faster those values start to decrease—the networks drawn out across the table will inevitably shift and decay.

One of Sloane’s earlier projects, Visible Networks, touches on some of the same ideas, but the way Logistic forces a viewer to think about prominence of paths shifting over time blurs the line between Earth-bound networks and digital ones in a novel way. Of course, like the systems in Logistic, the networks we interact on today are also bound to ebb and flow over time, as new paths gain influence and old ones are left behind to decay and disappear.

You can find Logistic, and several more of Sloane’s digital artworks on his website.

Interactive web comic simulates what it’s like to have dementia

Towards the end of his life, my grandfather began carrying a notebook wherever he went, writing down every minute detail of his day as best he could. He wasn’t working on a memoir or gathering ideas for a novel, but simply trying to keep track of his memories. At this point, he was years-deep into a battle with Alzheimer’s, and the notebook was his attempt to maintain some semblance of dignity, preparing himself for the five or so minutes later when he will have forgotten whatever it was he had written down. It was a valiant effort, but to our disappointment, it didn’t work.

In these moments, I always saw my grandfather’s thought process from the outside. But while reading These Memories Won’t Last, an animated web comic written and drawn by artist Stuart Campbell during his time at Vienna’s Air 15 artist residency, I got a peek at what it might have been like from his perspective. The comic tells the story of Campbell’s grandfather as he struggles with dementia, but as users scroll down the page, old panels begin to disappear and rereading them becomes difficult, mirroring the disease.

With dementia, there is no getting better

In the comic, Campbell talks about spending his youth listening to his grandfather’s childhood memories and old war stories, before tearfully recounting how those stories have begun to fade as his grandfather’s condition has continued to develop. He discusses moments when his grandfather became absorbed by paranoia, and times when his grandfather addressed him by his cousin’s name. These are all experiences I can attest to as well. Nowadays, Campbell’s grandfather still occasionally has brief moments of lucidity, but they are often sad affairs, where he reflects on what he’s lost and what he’s lived for. With dementia, there is no getting better. Just hoping that your children have a better future.

Today, I am the last remaining member of my mom’s side of the family, with my mom having passed away from heart disease a few years after my grandfather lost his battle with Alzheimer’s. The doctors tell me it was a lack of oxygen going to her brain, but in her last few weeks, I began to see behavior from her that mirrored my grandfather’s. One of the nastier sides of Alzheimer’s is that it is hereditary, and while it is not guaranteed that someone who has a family history of the disease will develop it, they are at a higher risk for it. I have no idea if I will get Alzheimer’s one day. I don’t particularly care to find out. I only hope that if I do, someone will be around to tell my story, just as Campbell told his grandfather’s.

You can read These Memories Won’t Last on Campbell’s website, and follow him on Tumblr.

Fairytale of New York: Max Payne 15 Years On

Remedy has always come at videogames from a slightly different angle. Quantum Break, coming out this week, appears to encapsulate the developer’s idiosyncrasies. Rote gunplay livened up with time manipulation. And then lashings of bizarre inter-textuality. They did it in the first two Max Payne games, and they did it again in 2010’s Alan Wake. But Max Payne is where it all started, the genesis of ideas the Finnish studio is still working through today.

///

“Outside, the mercury was falling fast. It was colder than the Devil’s heart, raining ice pitchforks as if the Heavens were ready to fall.”

You’ve got to hand it to Max. Even under circumstances of utmost duress he’s still able to turn a phrase like the one above. Hats off: it’s more than I could manage in his position. Max, the titular protagonist of 2001’s Max Payne, is having a shocker. Three years before the events of the game, Max’s wife, and their baby, were murdered. Cut to the present day and Max has been undercover for those interim years trying to halt the distribution of designer drug, Valkyr, the same drug his wife and child’s murderers were high on when the killing occurred. And, following an anonymous tip-off, Max has just been framed for the murder of his colleague on the DEA, with the mob and police gunning for him. Max, you see, is having a hard time.

In the first 20 minutes of Max Payne, Remedy has almost played its full hand. There’s the hardboiled Raymond Chandleresque script—awful, yes, but not without charm. There’s the cast of characters that consists entirely of the criminal underworld, bent cops, and drug addicts (prostitutes appear later). There’s New York City itself, coated in enough muck and grime you could scrape it off with a knife. There are the horror elements surrounding the death of Max’s wife and baby, which are truly unsettling, and there’s also the references to Norse mythology that surface throughout the game. And then, as a garnish to the dish, there’s the bullet time, a mechanic seemingly beamed in from The Matrix (1999) with nothing to tie it to the world or events of the game. Max Payne, it’s fair to say, is a shitstorm of influences and it absolutely shouldn’t work. But it does, just about.

a construction of stylized bleakness

What’s holding it all together is, primarily, Remedy’s take on New York City—a construction of stylized bleakness, a mirror to the depravity of Max’s personality. The worst snowstorm in the city’s history has hit, meaning the citizens are at home, waiting for it to pass. Max, though, is out on the streets, crunching through the snow. There’s an eerie quietness to these sections where you’re moving from one interior to another, forced to brave the elements, but once Max returns inside it’s back to Remedy’s squalid, debased vision.

It’s in the first of the game’s three acts where this vision is fully flexed. Max visits a seedy hotel owned by mobster Jack Lupino: the paint is peeling off the wall, yellow cigarette stains color the ceiling, and damp seeps through the walls. It’s brilliantly grotty. Act one climaxes in Ragna Rock, an old theater turned mobster nightclub. The mood is oppressive throughout as satanic imagery gradually reveals itself while Max descends deeper into the club, the darkness offset by the neon lettering. It’s sleazy, sticky, and totally memorable.

And then there are the horror sections; the drug induced nightmares Max is subjected to at various points throughout the story. I remember playing through these when the game was released, either 12 or 13-years-old, and being utterly terrified by them. The screams of Max’s wife, the wailing baby, the contorted perspective, and that blood maze, navigated by following the cries of Max’s dead child. Playing through it now, the mood holds, and compliments the main action of the game. Too often, though, the nightmare sequences descend into frustration as Max is unable to find a way out of his own psyche, or worse, falls to his death after venturing too far from the invisible platform the blood trail is laid upon. You’re reminded, in these instances, that this is a game made 15 years ago—a feeling that the shooting, paradoxically, confirms and confounds in equal measure.

it shouldn’t work

It’s basic, let’s say that. There’s no levelling up in sight, there’s no tweaking of the weapons, there’s no cover system. And there’s no regioning on Max’s perp enemies. Leg shot, head shot, it doesn’t matter; they all count the same. Max is merely given a set of weapons and one additional mechanic, the bullet time, to clear each room of enemies. But in that there’s almost a pureness to the proceedings. It has a sharp focus that lends the game a sense of propulsion as Max careers from one room to the next, addled by the effects of the painkillers. For all the talk of balletic gunplay surrounding the game on its release, the reality of the shooting is messy and twitchy. Max lurches from real time to bullet time, scraping by while sustaining huge damage. But in the instances where it does all go to plan, he’s able to transcend the moment. Those slow seconds afford Max a sense of relief, fleeting clarity in a world where morality and purpose seem absent. They are, tragically, minor victories for a man already beaten.

But, really, Max Payne the shooter is the least remarkable aspect of the game. It’s the conviction with which the world is created and presented that makes the game work, from the daft comic book presentation of the story to the relentless fourth wall breaking nonsense. Like I said, it shouldn’t work, but the sheer exuberance of Remedy to chuck this much stuff at the game and, more remarkably, make it stick, makes Max Payne worth playing today.

It stands apart from so much of the dross that constitutes the shooter landscape since its release back in 2001 and right up to the present day. In those intervening years, publishers rinsed the World War 2 setting for all it was worth, and then did exactly the same thing with titles utilizing contemporary conflicts in the Middle East.

More recently, there seems to have been a collective step away from real-world conflict. This year’s Far Cry: Primal retreated into our prehistory while the latest entries in the Call of Duty series concern themselves with future warfare. Quantum Break appears to sit outside of these developments but its sci-fi premise and glossy, contemporary setting already seems less distinctive than Remedy’s previous games. Max Payne, though, stands for singularity, for imagination, in the face of market trends and demands. Playing the game 15 years on, it’s a refreshing tonic to the increasing homogenization of shooters.

April 2, 2016

Weekend Reading: You Can Take The Hippies Out of Hippie Town, But…

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

With ‘Patience’, Daniel Clowes’ Looks for Answers to the Big Questions, Sean T. Collins, Observer

Does time travel sound like a blast? Hold that thought. Sean T. Collins speaks with cartoonist Daniel Clowes about his new book Patience, in which a time traveler attempts to save the one he loves. This being a Clowes book, the time traveler is more confronted by the weight of modern anxieties and his own shortcomings than the more traditional sound of thundery super mutants. Okay, how about now, how does time travel sound, champ?

Google and Apple: the High-Tech Hippies of Silicon Valley, Nikil Saval, T Magazine

Silicon Valley likes to think of itself as the starting line for the future, but despite trying to revolutionize the world or die trying, their ideals for community and architecture are helplessly stuck in the past. Nikil Saval looks into “Hippie Modernism” and the influential design ethics that lead to the kind of influential people who still assure you that the wearable boom is on its way.

Photograph of Zack Snyder by Kurt Iswarienko for Bloomberg

Director Zack Snyder’s Superhero Life, Devin Leonard, Bloomberg

If you happened to be one of the thousands of people who saw, then regretted, Batman v Superman over the weekend, you might be interested in a profile of its sculptor. Want to guess how many battle axes are in Zack Snyder’s office? The answer will not surprise you!

The Mothman Economy, Alison Stine, The Awl

Point Pleasant, West Virginia, meanwhile, is not Silicon Valley. It does not have billions of dollars to throw at campus redesigns or millions to guzzle at after parties. If people do pass through Point Pleasant to leave a few dollars behind, it is most likely because of a big metal, ruby-eyed beast, honored in the city with a monument since 2003. Alison Stine explores what life in a cryptozoo town is like, where it’s believed a fabled creature tried to warn them of a real life tragedy.

Header image: A page from Daniel Clowes’ new graphic novel, Patience, published by Fantagraphics Books.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers