Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 138

April 8, 2016

Artists are turning to voxels to make the familiar feel new

On February 21, 1986, Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda was first released in Japan. This week, to celebrate the game’s 30th anniversary, series fans Scott Liniger and Mike McGee took to browser to release a complete 3D remake of the first game titled The Legend of Zelda: 30 Year Tribute. Unfortunately, Nintendo has since pulled the project, but what’s notable about it is how it used voxels to make the familiar world of a decades-old game feel new again.

Short for “volumetric pixels,” voxels are an oft-forgotten method of rendering 3D worlds that have nonetheless been making a comeback as of late. As explained by Kill Screen founder Jamin Warren on PBS Game/Show, voxels are essentially pixels with depth, small cubes placed together to create detailed, though often blocky, 3D graphics. Because this requires more processing power than polygons, which are small planar shapes that come together to create objects, voxels ended up falling into obscurity while the polygon became the game industry’s primary way of creating 3D games, similar to how the cassette beat the 8-track.

As computers have become more powerful, however, the voxel has seen a small resurgence, most notably in popular block-building game Minecraft (2011). So when Liniger and McGee set out to recreate Zelda in 3D, the blocky nature of the voxel proved a perfect way of recapturing the nostalgia of the original game’s pixel aesthetic. It’s a technique that resembles Silicon Studios’ PlayStation 3 game 3D Dot Game Heroes (2009), which also used voxels to pay homage to the original Legend of Zelda.

Beyond Zelda, though, programmer Trần Vũ Trúc has set out to voxel-ize the entire Nintendo Entertainment System library with his browser-based 3DNes emulator. Using actual, original game files, the 3DNes emulator is able to extrapolate the pixel graphics of old NES games into voxels, rendering them in 3D for an effect that looks something like a diorama. This includes the original Legend of Zelda, of course, but because the emulator doesn’t build these games from the ground up like 30 Year Tribute or 3D Dot Game Heroes, its results often look more rough. Still, as the project is currently in beta, certain hiccups are to be expected. The 3DNes emulator only works in Firefox at the moment, but it serves as another example of fans using voxels to make the old seem new.

harkens back to childhoods spent exploring blocky worlds

Outside of games, however, businesses are using the aesthetic of the voxel to make the new seem old, hoping to appeal to their customers’ sense of nostalgia. Drive-in chain Sonic, for instance, has recently taken to Instagram to show off a series of new cube-shaped milkshakes that are currently being developed exclusively for the Coachella music festival. Looking like they came straight out of a Minecraft power user’s kitchen, the cube milkshakes are being designed with help from Instagram user Christine Flynn, who has a history of dressing up everyday food to look fancy. Despite offering less milkshake than a traditional cup, these cubes offer a novelty that at the same time harkens back to childhoods spent exploring blocky worlds.

It’s difficult to reconcile the idea of novelty and nostalgia, with the former representing the new and original and the latter representing the old and fondly remembered. But voxels allow artists to keep one foot firmly in each camp, harkening back to the pixel aesthetic of youth while also capturing the depth and clarity of more modern projects. As such, the once overlooked aesthetic of the voxel is emerging as a powerful way to bring the comfort of youth into adulthood.

Halo composer is making a “musical prequel” to his next big game

“It needs to be ancient, epic, and mysterious.” These were Marty O’Donnell’s only instructions from Joseph Staten, who’d asked him to write the music that would accompany Halo’s (2001) unveiling at Macworld four days later on July 21, 1999. The melody that resulted from Staten’s minimalist direction, and O’Donnell’s clever use of Gregorian chant, has since become synonymous with the Halo franchise. Rolling Stone named the score for Halo: Combat Evolved the Best Original Soundtrack of 2001. Then, in May 2005, BusinessWeek reported that the first volume of the soundtrack for its sequel, Halo 2 (2004), had sold upwards of 90,000 copies and landed at number 162 on the Billboard 200 chart, something no videogame soundtrack had ever done before.

Today, Highwire Games, the Seattle studio O’Donnell co-founded in 2015 with several other industry veterans, aim to bring his tradition of cutting-edge music and sound into the realm of virtual reality. Their debut title is a first-person PlayStation VR exclusive called Golem, announced at last year’s PlayStation Experience keynote.

Although Golem has no release date at the time of writing, Highwire is currently raising funds on Kickstarter for a “musical prequel” to the project called Echoes of the First Dreamer. A stand-alone album “meant to be a musical journey that tells the story of the world of Golem,” Echoes will be released digitally to backers before the launch of the game, with CD and vinyl pressings also available. The compositions heard in the campaign video meld gentle piano melodies with orchestral strings in a way that’s at once familiar and entirely new—recalling, at times, the intimate soundscapes of Halo 3: ODST (2009).

As for the virtual reality experience of the upcoming game itself? “The biggest leap forward from a tech standpoint is 3D audio,” O’Donnell says. “We’re already working with Unreal 4 and Wwise to use [binaural audio technology] in the headphones in order to place all the sounds in a three-dimensional space around your head.”

“the music will reflect an intimate, less bombastic approach”

And further breakthroughs are being made in spatial audio at this very moment. One pioneer in the field, Professor Edgar Y. Choueiri at Princeton University, has “actually developed filters that can create 3D audio from two speakers—without the use of headphones,” according to O’Donnell. “I’m not sure if his technology will be ready for the launch of PS VR, but it’s been fascinating for me to work with him and hear the amazing results. It’s possible that I’ll be able to utilize this even on the music recording for Echoes of the First Dreamer. We’ll see.”

While he’s hesitant to “oversell” PlayStation’s VR, O’Donnell explains that “there really is nothing like it currently on the market. Once you put on the head-mounted display, you are visually transported to another place. Your brain really starts to believe that [what you’re] seeing is reality. Once you add the full 360-degree audio field to the visuals it’s almost impossible to realize that you aren’t actually there. I found myself trying to lean on a stone parapet that our artists had created even though I knew that I was still sitting on a chair in my studio. When you take over a golem in our game, you really start to feel like you are controlling its movements and you are seeing through its eyes. When you swing the sword or shine the magic flashlight, because you’re holding a Move controller, it feels completely natural and needs no explanation.”

Golem’s story begins with the player character injured and confined to her bed. “You’ll need to learn and master the ability to create and control golems so you can explore and restore order to your world,” says O’Donnell. “When you are controlling a doll, bugs will seem like a huge threat—and when you’re controlling a 20-foot-tall stone giant, you’ll swing a huge sword and fight giant, evil golems.” However, players coming to the game hoping for combat in the vein of something like Halo or Destiny will be met with disappointment. Though the majority of Highwire’s employees previously worked on blockbuster titles at studios like Bungie, 343 Industries, and Valve, this is a new direction for the team. The music on Echoes of the First Dreamer, and within the virtual game world, will reinforce that.

“Since the story of Golem is smaller and more personal than some of the previous stories we’ve told,” O’Donnell says, “the music will reflect an intimate, less bombastic approach. We’re not flying around the galaxy saving mankind—we’re playing as an injured child who wants to help save the family from a malevolent magical force.”

O’Donnell is the 2015 recipient of the Game Audio Network Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award. His album Echoes of the First Dreamer will only be released if it reaches its funding goal by Tuesday, April 12. Check out the Kickstarter and reserve your copy here.

More people will soon be able to play The Chinese Room’s poetic videogames

Very soon, thousands more will have the opportunity to get lonely with a videogame in the most beautiful way. Yes, The Chinese Room is bringing both its poetic narrative games, Dear Esther (2012) and last year’s Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, to new platforms—the former is coming to Xbox One and PlayStation 4, while the latter makes its way to PC.

Other than a few pleasant additional touches, like a developer’s commentary for Dear Esther and a few bug fixes, the games will remain essentially unchanged. That means each of these games will, once again, invite you into their virtual worlds as their seemingly lone consciousness, left to roam a lovingly-crafted recreation of classic British countryside and coasts.

They want you to look, to listen, and to think

What perhaps distinguishes both of these games is the feeling of having been left behind. There’s a reason for that: you have been. Maybe it’s the absence of other human characters—bar the orbs of light that represent the disappeared townsfolk of Rapture—but the environments become characters unto themselves as you wander. You navigate dirt roads, crystal caverns, deserted business spaces, and each in turn tell you fractured bits of a story.

And that goes for both games. They want you to look, to listen, and to think upon the personal stories that you uncover. Each prioritize an examination of their surroundings, which attain a kind of photorealistic pastoralism, playing with light and dark like paint on a canvas, across lichen-coated rocks, teeming flowers, and encroaching greenery. The experience is more like strolling through a gallery than segwaying between plot-points.

2015 was a big year for games that want you to spend more time by yourself and to consider more deeply. Rapture proved to be an impressive meditation on intentionality, on powerlessness, and agency. It’s this that elevated it. It seems only right Rapture’s smaller sister in Dear Esther be delivered to the same people that were able to appreciate it when it came out last year, and vice versa.

If you want more on either game, you can read our previous takes on Dear Esther here, and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture here and here.

The VR experience that tries to stop you eating meat

Assuming you are not already a vegetarian, what would it take for you to renounce meat? What previously unseen sight would turn you to swear off steak? What heretofore unheard fact would get you to give up fried chicken? Perhaps it would it help if the point were made in brand spankin’ new virtual reality?

The animal welfare charity Animal Equity is betting on the answer to that last question being a resounding yes. Its VR film, iAnimal, places you in a cage with an animal destined for the dining room table and invites you to look around. This whole experience was made for VR headsets but an accompanying interactive video has been uploaded to YouTube.

Narrated by Peter Egan (Shrimpie of Downton Abbey fame), iAnimal Pigs talks you through the life of a pig destined for slaughter. Egan proceeds in the second person: “You were born in a cage. … For the single month that you knew her, your mother was penned against the floor, unable to show affection or comfort you or your siblings.” It’s grim stuff, rendered all the grimmer by the ominous background music.

The footage in iAnimal is indeed harrowing. Suffice it to say that pigs bred for slaughter do not have the greatest of lives. Whether this is really news, however, is up for debate. Indeed, the real question raised by iAnimal is whether the use of virtual reality meaningfully strengthens a rhetorical claim. On this evidence, it’s not clear that one should answer that question in the affirmative.

the logical conclusion of the “life sucks for animals” argument

If virtual reality is capable of engendering empathy, it must also be capable of inflicting a certain amount of emotional harm. The former aspect is the one that gets played up—hey look how this new technology can make you relate with little refugee children—but it is a mere effect of VR’s power to trigger something in the viewer. Indeed, empathy can be the product of fear. That’s iAnimal’s premise: experiencing the terror of a caged animal will make you a more empathetic person. No creative work can be expected to perfectly strike this balance, but it is the existence of both facets that is truly noteworthy. (For the flipside, consider last year’s 9/11-inspired VR experience.)

As a work of activism, iAnimal is willing to stack the deck in favor of a particular conclusion. To wit: Egan’s narration, which constantly tells you what you (the pig?) are feeling. Each statement is plausible—again, it’s hard to doubt that pigs like this life—but it’s not really the VR that’s making you feel these things when Egan declares them in the second person. The balance of showing and telling is off here. VR can bring you closer to the perspective of a pig, but it lacks the formal advancement to see the world through its eyes. iAnimal brings you closer, sure, but it struggles to get across this line.

What exactly does iAnimal teach the viewer that was not previously knowable? Its images of animal suffering are not meaningfully different from the posters I pass on the way from work. The video’s conceit that everything on display is legal is no different than Ted Conover’s Harper’s exposé “The Way Of All Flesh.” iAnimal is powerful, sure, but the only element it adds to existing media narratives is a different camera angle. Maybe that’s enough. “iAnimal brought me back to reality with a jolt,” writes Engadget’s Aaron Souppouris.

But what if that isn’t enough? What if seeing the same story from a slightly closer perspective doesn’t finally change your mind? Where does that leave us? iAnimal takes you to the logical conclusion of the “life sucks for animals” argument, but even if that persuades a few more people it ultimately feels like more of a dead end. If the posters and the videos and now this VR thing all fail at their stated goal, it’s hard to believe that actually looking through the eyes of a pig will make a difference. Virtual reality’s rhetorical power may not allow us to tell new or meaningfully better stories; it may just allow us to proclaim our existing positions with even more vehemence.

How babies can help teach game design

There are many different types of people to consider when making a videogame and a lot can be learned by discovering their needs. There are those that don’t normally play games, children, as well as the elderly, but there’s one group that’s easy to dismiss, if only because they seem too young: babies.

Babies themselves are constantly learning new things and conveying their thoughts and feelings in a way only they can. Observing the way they learn and applying that to game design can be incredible beneficial, as a child learning about the world is similar to a player interacting with a new game for the first time. This is the exact conclusion that Luis Antonio, designer of the time-looping puzzle game Twelve Minutes, came to after watching his two-year-old daughter while working on his game.

she would become overwhelmed by everything she had to play with

In a new blog post on the Twelve Minutes website, appropriately titled ‘Babies and Game Design,’ Antonio explains that his daughter and several books on parenting led him to the realization that the way we teach children can also be applied to teaching players in games, to the point that it even helped him solve a few problems he ran into during development. He shared a few of his discoveries and broke them down into four categories: Illusion of Choice, Attention Focus, Identifying Emotions, and Player Focus. Four things that probably sound familiar to anyone that makes or plays games regularly.

As a parent, Antonio would often ask his daughter to do something, to which she would refuse to do if she didn’t feel like it. However, if given options directly related to what he wanted her to do (like putting on blue or white pants), she would respond more positively: “In design I often need to limit the player’s choice towards a specific direction without it feeling forced or artificial, and by giving the player naturally limiting options, they still feel in control and enjoy the guidance,” Antonio writes.

In another scenario, when all of his daughter’s toys were spread out and placed in different corners of the room, she would become overwhelmed by everything she had to play with, and wouldn’t stick with any one set of toys for too long. But, after placing some toys within her line of sight but out of reach, and others inside boxes, she would spend more time with one set of toys since she was no longer overcome by the options presented to her.

“I try to organically expand that set of knowledge in a way that is interesting”

According to Antonio, scenarios like this “happen a lot in Twelve Minutes, since the whole game is set in a small space and he needs to prevent a similar information overload from happening. “Each loop, I try to organically expand that set of knowledge in a way that is interesting but without becoming too limiting,” he writes. This covers only two of Antonio’s examples of the game design lessons that he’s learned from interacting with his daughter, but he stresses his findings are not a complete list or a set of rules to follow. It is, nonetheless, a fascinating and interesting subject to discuss.

As for Twelve Minutes itself, it’s still being worked on, though the business side of things has been taking up a lot of his time recently. Next time it’s shown, it should have a new art direction and animations, which will make “the experience a lot more immersive and closer to the final product.”

Find out more about Twelve Minutes on its website.

Come for the swordplay, stay for the mystery

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Hyper Light Drifter (PC, Mac)

BY HEART MACHINE

Hyper Light Drifter starts out loud—streams of stars, planet-sized eruptions, and a huge, electric soundtrack by Fez (2013) composer Diasterpeace. Then it fades into the near-silence of an open map and a drifter coughing up blood. You’re left with a headful of questions. As you push the drifter to cut through stoic enemies and dash across environments lush with secrets, you start to piece together the answers. What emerges is a language. It turns pixels into glyphs, and tells a story without words, instead letting the memories of inflicted survivors and foul science experiments reveal the underlying plot. And so, while Hyper Light Drifter might play out like classic Zelda‘s sharper, wiser sister, its journey is even more mysterious and gripping, as if you’ve been tasked with decrypting an ancient tome that holds the planet’s greatest secret. It lures you in with purple bloodstains and sword artistry, but it’s the unknown promise held within the game’s hazier details that keep you and the drifter pushing through the pain.

Perfect for: Star warriors, Zelda fans, decrypters

Playtime: 10 hours

Imagining the technological singularity with Factorio

The trouncing of the world’s top Go player by Google’s AlphaGo AI has led more than a few people to speculate on how we’ll be feeling the ramifications of this victory in the near future. What this speculation mainly concerns is the question of what will happen if software continues to eat the world with such a voracious appetite that we are only beginning to truly fathom. For now, “Big Data,” the truly massive collection of data that humans collectively generate through any and all combinations of internet browsing history, biometrics, credit card payments, and more, provides the equivalent of a well balanced diet to these insatiable AIs, giving them plenty to process day in and day out.

AlphaGo, equally hungry, was “taught” how to act like us by looking repeatedly at another equally massive dataset: the thousands of past Go games played between both amateurs and professionals. This process of repeatedly analyzing large datasets, either by AlphaGo or any other AI, in domain-specific scenarios is known as “deep learning,” and speculation on what a world full of well-fed AIs looks like is currently being highly influenced by the AI researchers working in and around this topic. AlphaGo’s victory was, in some ways, yet another vindication of this model.

“Deep learning” can be applied to much more than Go though, and one must realize that we generate massive amounts of data daily about us and almost everything we do. This is to say, then, that computers and AIs are learning not just about Go, but about us, writ large. Your phone now knows how you’ll likely travel to work (and on what days you’ll choose to take a shortcut) and your Facebook feed is an algorithmically curated set of pitch-perfect posts for your predicted mood and current interests. But, as evidenced by AlphaGo’s victories over Lee Sedol, computers and AI are becoming not only good at predicting what it’s like to be us, but are quickly becoming much better at what we do than we could ever hope to be. And, when an AI can beat most humans in Atari 2600 games or learn to read, the obvious question arises, “Will this affect me too?”

We will sail past the technological singularity sooner than we may imagine.

Founder of Google’s “Deep Brain” deep learning project Andrew Ng has already expressed concern that “There is a high chance that AI will create massive labor displacement, putting people out of jobs.” If a sophisticated AI can become a Chess Grandmaster in 72 hours and paint like Van Gogh, the question seems not a matter of “if”, but when—How long before the master accountant AI? The 10x programmer? The pulitzer journalist? If it is truly a whimper that ends the world, these seemingly incongruous and unrelated advances in AI research may signal not only that our time is nigh, but that we will sail past the technological singularity sooner than we may imagine.

These tiny murmurs of progress are likely paving the road to the development of what’s known as the “superintelligence,” but where that leaves humans after it’s “done” is the subject of pure, if reasoned, fiction. Tim Urban over on WaitButWhy gives a neat overview of what this future could be, ranging from “our worst nightmare” to “our greatest dream,” and from Her (2013) to Transcendence (2014), opinions seem similarly, and predictably, split on what happens after the technological singularity. It’s all emotional speculation because the point of the superintelligence is that we, as humans, can’t understand or comprehend it. But, as humans who still must plan for and potentially preempt the future, when it comes to simply understanding what may be next, we have a few options.

Though looking for verisimilitude through simulation can be a potentially destructive fool’s errand, the Steam Early Access title Factorio provides us with a glimpse into what this future may actually be like. Crash landing on a planet with no narrative exposition to speak of, Factorio starts the player off on “a remote and unexplored planet full of life, riches, and natural resources,” and from there, as the trailer says, “your only possibility to survive is the use of your talent to create technology.” Technology here does not take the Civilization angle of aqueducts, the printing press, or the wheel, but instead manifests in industrial logistics structures (factories, supply belts, robotic arms, etc.) meant only to exploit the unknown planet’s aforementioned richness and produce refined materials for… we’re not sure.

The question of who, why, and for what reason you actually need to build anything is forever unclear, and nowhere on the current development roadmap is there anything indicating that this will be changing. As the trailer said, you must build to survive, but as a player in the game, you survive just fine without building anything. You can let the game run for hours and hours on its own, only to come back to a serene planet with your worker still standing idly by.

However, should you choose to build—and you should, because building factories and logistics networks in this game is satisfying to the point of becoming addicting—two things happen. One, the greater question of “why” never dissipates; instead, it hangs constantly over your spidering network of interlocking and articulating mechanical arms, supply belts, fabricators, and furnaces. Two, monsters, or as Factorio ungenerously calls them, “natives,” attack. As the trailer says:

“Beware, you’re not alone in this planet. Natives will try to recover what belongs to them, forcing you to focus the production into combat assets.”

To be clear then, Factorio contextualizes the work you’re doing for reasons nebulous at best as something to be defended at all costs. This means, in the case of the game, killing off the native population of creatures who oppose your pollution and exploitation of their natural environment that, upon your arrival, was by all indicators in a point of peaceful equilibrium. Dogmatic then, is the idea of work and progress in Factorio, its existence and implementation being the unquestioned and veered towards “attractor state” of the player in its narrative universe. All of the actions you can take in the game directly forward “work” in one form or another (building, mining, crafting, transporting)—you are given no tools to question its position or role in this foreign environment, it being quite literally the only thing you can do.

The machine you created functions without you.

This point, too, is echoed in Factorio’s actual structures, most often single purpose machines that do one thing well forever, stopping only to wait for more work. Gyrating arms like those from automobile assembly plants will quickly and efficiently move resources and goods from here to there, and will wait patiently for another object to arrive. This period of waiting starts off being relatively long because you, as a player, are forced to manually provide your structures with their required materials. Quickly though, you realize you can connect X to Y to transport A to Z (which turns into B that moves to C…), in turn almost entirely eliminating any need to wait for anything. The pull of automation is strong though, and with the later addition of “logistics robots” for easily transporting goods across long distances, you end up obsoleting most forms of your own labor, leaving you tasked only with killing the literal “bugs” in your system (though unmanned turrets can mostly take care of this as well). The machine you created functions without you.

This is the post-AI future, where whole systems of automation not only replace us by design, but also replicate themselves in novel situations (like a remote planet) where, with the still-needed and likely disdained human spark, they are able to almost instantly reach a state of insular automation that furthers some nebulous goal that we humans are simply brought along to help out with. Though your factory system starts out as a very “knowable” combination of belts, arms, and supply crates, the thing as a whole slowly grows beyond your total comprehension. Understanding how coal got along the first belt you built to that first furnace was easy, but when the belts multiply by an order of ten and you add in trains, quadruple your furnaces, and throw in some assemblers for good measure, thinking outside of any local patch of automation is incredibly difficult. Your role in Factorio moves rapidly from an individual agent of immense change to a “conductor” of systems, gently guiding your factories towards greater and greater productivity with your carrot-on-a-stick goal of “survival.” Remember, if you don’t build anything, nothing will attack you.

Yet, as players, we do still seek the carrot, and the nebulous goal you chase may very well represent what humanity’s “goals” in general may seem like from our vantage point in an AI-driven future. When AlphaGo made a move that seemed inhuman, it wasn’t working from some arbitrary data set—it was using human data and using it better than anyone else ever had before. AlphaGo made a decision by learning past us, “seeing the matrix” so to speak, and could make seemingly incongruous and improbable decisions based on a deeper understanding of our own data than we have.

Factorio’s tech tree pushes us to make machines that help us make machines and weapons to stop anyone from stopping us, but we should consider the possibility that we don’t fully understand what these machines are actually doing. To us, a furnace is a furnace, it smelts raw ore. But to a well-fed AI? Instead of Go games, what could an AI do with “factory data”? What “moves” does it make? It’s worth considering that the notion of “work” we see being executed in the game is not the same idea of “work” an AI understands when provided with Factorio-like data. Even as the game unceremoniously ends upon the completion of your stated goal to launch a rocket into space, the player is prompted with a simple message: “Finish” or “Continue.” With our comprehended work seemingly “completed,” some “work”, to our surprise and bewilderment, must still, and forever more, be done.

Header image: Industry by Roman Pfieffer

April 7, 2016

What cyberpunk was and what it will be

This is a preview of an article you can read on our new website dedicated to virtual reality, Versions.

///

We often forget when predicting the future that it will inevitably continue to change. Whatever we dream up, however utopian or dystopian, will be subject to resistances and reimaginings. It will be a temporary state. The future will get old fast and there will be no end of history, despite frequent claims to the contrary, until the last human breathes the last breath. Travelling through modern metropolises at night, particularly in Asia, the temptation is to dwell on how prophetic cyberpunk classics like Blade Runner (1982), Neuromancer (1984) or Akira (1982) have been (to say nothing of earlier works like the books of John Brunner).

Yet there is also a sense, when we look closer, when the rain and the neon lights peter out, that this is partly an illusion. While cyberpunk-esque technological developments, and their side-effects, are increasingly coming to pass in meatspace, cities are stylistically moving away from the model we envisaged for so long. Just as the utopian space-age future of the West in the 1950s passed unthinkably into the past with space shuttles entering museums, so too is the largely dystopian cyberpunk vision, at least aesthetically, becoming outmoded. One of the central inspirations for Blade Runner, the labyrinthine Kowloon Walled City on the outskirts of Hong Kong, was demolished in 1994. It is now the site of a park with gardens, floral walks, ponds and pavilions. It is a post-cyberpunk space. If the apocalypse has come and (temporarily) gone, what was it really and what comes next?

READ THE REST OF THIS ARTICLE OVER ON VERSIONS.

///

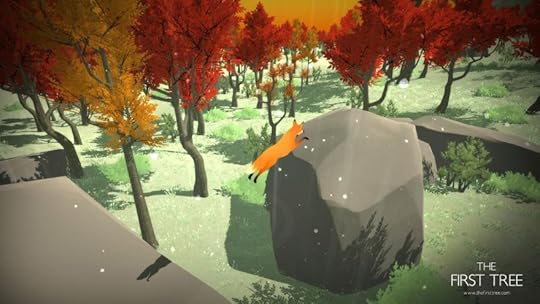

A pretty game about a fox will explore how we cope with death in the family

David Wehle is a game designer and recent father now coping with the loss of a loved one. Life and death have been, to put it lightly, on his mind. His upcoming game The First Tree is a personal, painful reckoning with a universal experience.

The First Tree is a game with two parallel stories: one follows a fox searching for her lost family, and the other a young couple learning to live with a death in their own family. When asked about his influences, Wehle pointed to games such as Journey (2012), Gone Home (2013), and this year’s Firewatch, as well as literary influences including Cormac McCarthy’s 2006 novel The Road. McCarthy’s book is about the death of the Earth, which Whele referred to as “probably the grandest, heaviest topic you could tackle.”

“This symbol of life, knowledge, and even the afterlife has powerful implications”

But more than that, he continued, The Road is about McCarthy’s relationship with his own son. “We just had our first baby three months ago, and those same themes of parenthood and life and death are explored in The First Tree,” he said.

The First Tree is about family, but as seen “through the lens of the grandiose,” Wehle said. “I love seeing intimate, domestic stories juxtaposed next to epic, origin-of-life stories, because in my mind they’re not that dissimilar.” The game concludes with the stories of the fox and family converging at the titular first tree, a symbol Wehle saw as archetypal. “This symbol of life, knowledge, and even the afterlife has powerful implications for the characters in this story, and eventually it affects both parties in unexpected ways,” he continued.

Wehle currently hasn’t released much info about The First Tree, but for those interested, you can sign up via the game’s website to be alerted when it is released (currently expected mid-2017), or follow him on Twitter for updates on its development. Note that the current screenshots are from a pre-alpha build.

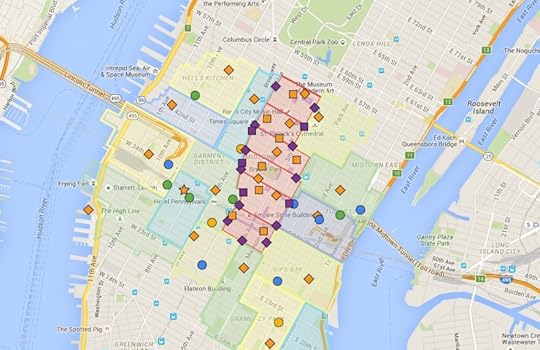

Now you can explore The Division’s version of Manhattan in Google Maps

There’s a stillness to The Division’s plague-stricken version of New York. Rats populate the streets in greater numbers than do human beings, and a rustling newspaper is often the only visible object in motion beyond the player character and the omnipresent snowfall.

The view outside of Madison Square Gardens is one example of how Ubisoft Massive has repurposed Midtown Manhattan to suit its game’s persistent, near-future crisis state. Fences are lined with razorwire. The digital billboard out front loops between two images: an American flag and the seal of the Catastrophic Emergency Response Agency, the game’s fictionalized version of FEMA. A tarp has been thrown over the sign at the front entrance of the building, rechristening it the Madison Field Hospital. “Remain calm,” a marquee urges. “Stay off the streets. Help is coming.”

Players might be forgiven for finding much of Midtown unrecognizable within the always-online game world. But Reddit user Feanauro has done their best to bridge The Division’s version of the city with that of the real world by mapping the game’s mission and safe-house locations onto a Manhattan variant in Google Maps.

Despite “some inconsistencies” and “visual anomalies,” which, Feanauro notes, are due to artistic license on Ubisoft’s part, the augmented-reality exercise largely succeeds. A player hoping to take a Division-inspired stroll through Midtown can now do so with relative ease; using the custom map, she might follow the very same path laid out by the game’s campaign, beginning at “Camp Hudson” along the real-life Chelsea Pier. This would probably best be accomplished with the help of a taxi, or an Uber driver, but then the very dedicated Division Agent in question would miss out one of the defining quirks of the experience—Agents can’t use vehicles. In fact, vehicles are not even a part of the game. Helicopter rides take place during cut scenes, while the campaign itself takes place entirely on foot.

the line between games and reality will continue to blur

Feanauro says he may add further points of interest to the map, such as “weapon parts, tools, fabric, [and] electronics,” but admits that he has little intention of adding items like boss-fight encounters and side missions. In the few days since his Reddit post went live, however, he has already made note of several significant additions to the Google Maps variant, so it remains to be seen just how far his efforts at reproducing the world of The Division might go.

I’m reminded of Cory Doctorow’s 2008 novel Little Brother, in which the book’s characters spend their time playing a massively multiplayer augmented-reality game (ARG) called Harajuku Fun Madness. “Imagine the best afternoon you’ve ever spent prowling the streets of a city,” Doctorow writes, “checking out all the weird people, funny handbills, street maniacs, and funky shops. Now add a scavenger hunt to that.” With titles like Nintendo’s Pokémon Go on the horizon, it seems the line between games and reality will continue to blur in the novel and exciting ways that Doctorow wrote about.

See Feanauro’s Google Maps variant of Manhattan based on The Division right here.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers