Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 132

April 21, 2016

Hardcore Henry and the problem with immersion

This is a preview of an article you can read on our new website dedicated to virtual reality, Versions.

///

A fight scene is a dance: not just between the characters in conflict, but between stunt people and the effects crew, between the cinematographer and choreographer, between the editor and sound designer, all of them moving together at once.

The best fight scenes have a narrative arc, however slight or implied. Think of Bruce Lee adapting to and punishing Chuck Norris’s brute power in Lee’s 1972 The Way of the Dragon, or the feral, hallucinatory slaughter that ends Kihachi Okamoto’s 1966 psychotic ronin portrait The Sword of Doom. These fights reveal something about the characters, or give us miniature dramas of will, all thanks to the intricate efforts of the filmmakers.

All this is to say that Ilya Naishuller’s Hardcore Henry not only fails to function as an action movie, but completely misapprehends the basic workings of action movies. Hardcore Henry employs an absurd gimmick: it’s filmed entirely in point-of-view shots to—if videogames have taught me anything—fully immerse you in the action. That it’s not all one take perhaps counts as restraint on the filmmakers’ part.

READ THE REST OF THIS ARTICLE OVER ON VERSIONS.

The Lion’s Song aims to depict the loneliness of history’s greatest minds

Originally created as a short title for a 2014 Ludum Dare game jam, old-timey narrative adventure game The Lion’s Song is now getting a full release. According to a new trailer for the game, four episodes are planned in total, expanding it beyond the “finely honed short story” of the original and into an extended interrogation of academic life in fin-de-siecle Austria.

The game stars three different turn-of-the-century artists and scientists as they struggle to find inspiration and learn how to cope with the pressures of success, as well as those of their time period. “To succeed in a world of men…” says one of the protagonists as she sits on a bench within what looks to be a university courtyard, “…I had to act like one.” As a crowd walks in front of her, she quickly trades her dress and updo for a suit-and-tie.

The rest of the trailer focuses on tapping pencils, restless nights, and tears as our characters stall in their work. Particularly striking is a scene where one of our leads stares expressionless into a mirror, his only company being his own blank reflection.

struggle to find inspiration

This sense of isolation is at stark contrast with the original game, the prompt for which was “connected worlds.” In it, a young composer named Wilma struggles with her work in a remote cabin until she receives a phone call from a friend who offers her comfort. The idea, explains developer Stefan Srb in a post-mortem, was to “depict a world in which the telephone was something new” and how it allowed for “the bridging of long distances that shrunk the world and didn’t at the same time.” Notable is how the game used split-screen to accomplish this, and though the split-screen seems to be gone now in service of the larger narrative, the need for connection appears to be as vital as ever.

You can learn more about The Lion’s Song over on its development log. Play the original here.

Let Suda 51 Die

It is rare that a piece of key art is worthy of comment. That ugly, industry-saturated term, “key art”, tells the whole story, bringing to mind images of focus testing promotional images usually of men with guns facing away, silhouetted in the light of an explosion. But this bit of key art, this is something special. Let’s just lay it out here, for your enjoyment.

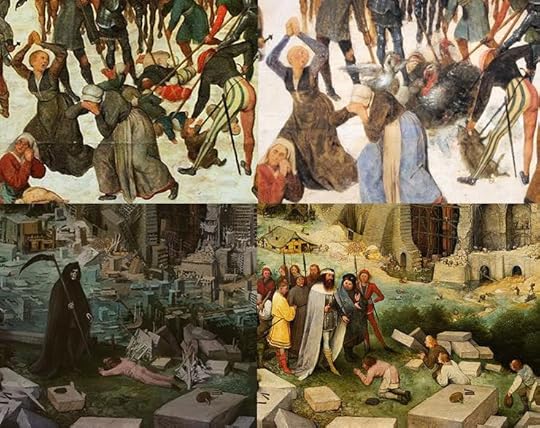

Observe the faded tones, the dappled light. Look on the grim reaper, posed classically, one hand stretched towards a prostate victim. Take in the towering pile of city, punctuated with plumes of smoke, the distant towers of a modern city all around. What a vision in digital paint. This is the key art for Let it Die, the upcoming hack-and-slash RPG from Suda 51’s GrasshopperManufacture, and it is more than a pretty picture. It may strike you as familiar, the forms and colors recognizable somehow. That’s because this piece of art is a paintover.

Above is Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel, painted around 1563. Note the warm tones, the dappled light. Look on King Nimrod, surrounded by his retinue of architects, reaching towards a grovelling builder. Take in the tower, its arched forms spiraling towards the sky. Now look at the line of scaffolding on the bottom left of the tower. Fix it in your mind. Now scroll back up to Let it Die’s key art. Scroll up and down a few times. Look at the raft turned to a dock. The winch integrated into a roller-coaster. The tools lying on the closest slab, now receding under accumulated dirt. The hill in the top left. The red stone in the center. Nimrod himself turned to the figure of death. Grasshopper didn’t just copy Bruegel, they iterated upon him, sketched out a tower of Babel 500 years later, their brushstrokes covering his.

But what are we actually looking at? Is it a lazy artist daubing over the work of a master, or a complex set of references, overlaid and interlocking? Does it help to know that Let it Die’s central city-tower seems to be an arena of battle, a place for warriors to test their strength, and that Bruegel’s tower of Babel was based on that most infamous of all arenas, Rome’s Colosseum? Perhaps things might be clearer if I pointed out that Bruegel was victim of one of the most famous acts of overpainting in art history, when his Massacre of The Innocents (1565-67) was, at the Holy Roman Emperor’s instruction, modified to have its dead babies and speared children replaced with animals and sacks of grain.

It’s tempting to imagine Let it Die’s art as a network of these ideas and images. That its overpainting is a reference to Bruegel’s censored violence and that its city-arena is connected to the folly of Rome’s gladiator battles. It wouldn’t be out of character for a designer like Suda 51 to be so bold. His existential detective story Flower, Sun, and Rain (2001) riffed on Wim Wenders, the nightmarish Killer7 (2005) finds points of connection with Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), and even the grindhouse pastiche Shadows of the Damned (2011) started life as an adaptation of Franz Kafka’s final unfinished novel, The Castle (1926). That book, supposedly Suda’s favorite, might be one of the most distinct indicators of his approach.

there is something hollow here

The Castle is a work that specifically blocks progression, tangling the reader up in subplots and diversions that do nothing to progress the fortunes of its protagonist K. The heroes of Suda’s earlier work—Sumio Mondo of Flower, Sun, and Rain and The Silver Case (1999), The Smith syndicate of Killer 7—are equally lost, knowing less than the player, stumbling through endless increasingly surreal tasks. Even Travis Touchdown’s quest for the position of number one ranked assassin in No More Heroes (2007) might be seen through the same filter, his challengers constantly diverting him on bizarre side stories. It is tempting to imagine Let it Die as another potential work in this vein, rich, surreal, jammed with references, but it is also naive.

Here is Let it Die’s city of babel again, darker, foggier, more like a thousand Kowloon Walled Citys piled on top of each other than a Bruegel painting. And here is Suda as we know him, ramming that city with stylish violence, freakish horrors, and at the end of the trailer a Daft Punk anime crossover. Our figure of death? He’s got a skateboard now. This kind of tonal insanity is what we’ve come to expect from Suda, and yet there is something hollow here. Perhaps it’s the fact that Shadows of the Damned, Kafka-inspired or not, was an oddly misogynistic mess of a game. Or that Killer is Dead (2013), his supposed return to Killer 7’s masterful form was an even more misogynistic collection of self parodying non-sequiturs that rang hollow at every beat. In fact, by my count, it’s been almost 10 long years since Killer 7, and while No More Heroes went some way to filling that gap, its otaku-obsessed, non-stop pop-culture remix felt like a side project. A Chungking Express (1995) to his In The Mood for Love (2000), so to speak.

Yet here we are, Bruegel on screen, playing that game again. Trying to unpick the references and the details, expecting something mind-blowing to emerge from the synergy of high and low, ugly and sublime. We want Suda to be an auteur, a genius, we want his games to blast through our optic nerves and into our brains like napalm. Here I am overlooking over the dreary screenshots, and the free-to-play mechanics, and thinking to myself, could this be Suda’s Dark Souls (2011)? Lets face it, in reality this key art is the work of an unknown (and seemingly talented) artist at Grasshopper, who probably did a Google Search for “tower of babel” and downloaded the Bruegel to work it over. Right? But we want it to be Suda, we want it to be great. As Kill Screen’s Zack Kotzer put it in a late night conversation:

‘I miss the old Suda, the Sun and Rain Suda

Smiths lyric bold Suda, set on his colours Suda

I hate the new Suda, the laptop sticker Suda

The kinda bland Suda, beat-em-up fan Suda

I miss the obtuse Suda, fast and loose Suda

I gotta say, at that time I’d like to meet Suda

I used to love Suda, I used to love Suda

What if Suda made a game about Suda?

Called “I Miss The Old Suda,” man that would be so Suda!’

When I load up the website for Let it Die, death skates across the screen on his board, scythe casually hooked over his shoulder. In his wake some text appears: “Death cancels everything, but the truth.” It’s a William Hazlitt quotation, a 19th century philosopher, painter, and poet; a true renaissance man. When I see it, all I can do is laugh. Suda 51 used a single title to cover all of his early games, a thematic link that tied these often incoherent pieces together. “Kill the past.” Perhaps Suda should follow his own advice. Perhaps it’s time we let Suda die.

Shinobi and the art of videogame “cool”

This article is part of PS2 Week, a full week celebrating the 2000 PlayStation 2 console. To see other articles, go here.

///

Shinobi (2002) begins with a cliché. Two honorable ninja warriors, a master and a student, face off in a duel. The winner will take a position as the leader of his clan. The other will die. Off to the side, a female member of the clan complains to an elder: Why does it have to be this way? “This is something they have to do,” he replies. Of course he does.

Shinobi exists firmly in the cliché action movie world, where hard and irrationally grumpy men fight over poorly defined concepts of honor, all in keeping with rules that no one in their right mind would adhere to. It is, in short, excellently and fearlessly cheesy, committing to its own absurd premises in a way that only the most pulpy entertainment can.

When the protagonist, Hotsuma, begins the game proper, jumping from rooftop to rooftop in modern Tokyo wearing a Metal Gear Solid-style stealth bodysuit and Batman gauntlets, it’s immediately endearing and believable. I mean, what else would he be wearing?

When I was a kid, I told stories with my action figures. I self-consciously emulated my favorite media: shonen anime (intended for young boys), Power Rangers, American superheroes, and whatever snippets of action movies my parents let me get away with seeing. They were infinitely remixable improvised fanfictions, set on the stage of my wooden toy box. I’d act out scenes I’d watched, adding my own flair and imagery, conjuring up reasons for Spider-Man to fight Venom ad infinitum. It was here that I first learned that I loved telling stories. It was also where I first understood the thrill of participating in the particular type of storytelling that hero-based action media provides.

Heroic violence offers a profound but ill-defined sense of mystique. It’s an awareness of being involved with great people doing superhuman things, whether it’s Jack Bauer saving the country in the nick of time, or Zatoichi the “Blind Swordsman” conquering impossible odds with a grace and aplomb that no sighted warrior could ever hope to match. It’s a sense of cool. Cool that comes in the knowing that I could never be as exceptional or strong as this character. I could never do what they do. But knowing that they can do it is thrilling.

Did the steel connect?

“Cool” is a concept not broached much in serious critical talk, but it’s essential to understanding this type of media. It especially seems relevant in videogames, a medium which strives to capture the same participatory thrill of my childhood dramas. Cool is the cousin of empowerment, after all. The basic power fantasy of many videogames bleeds into the fantasy of cool-guy mystique set up in heroic violence media. It’s not just that you can beat the boss. It’s that beating the boss can be a performance, a virtuous theater of heroic bloodshed.

This is the power of Shinobi. Situated at the middle of the three-dimensional reimagining of action videogames that would eventually birth such bombastic, mystique-filled games as Bayonetta (2009), Shinobi has a pure dedication to delivering on the fantasy of action-movie cool. It does this in a novel and direct way; by directly translating the tropes of heroic violence films into its gameplay in a manner that still transfixes.

Core to Shinobi‘s action is a simple, repeated maneuver. You’ve seen it, I’m sure, in some action film or anime. It’s iconic, and Shinobi is geared around tapping into that particular iconicism.

It goes like this: The sword-wielding hero attacks with a running leap, his weapon slicing through the air like a flash of light. The viewer doesn’t see the weapon connect. They just feel it, through deft cinematic cuts and a manipulation of lighting and sound. They feel it, and then the hero lands, crouched, sheathing her sword. Her foe stands still for a moment, stunned, and the audience has a chance to wonder: Did the steel connect? Perhaps the enemy gloats, thinking they’ve won. There’s a long, expectant pause.

Then, as if physics needed a moment to catch up, it happens. A slide of skin against skin, or a trickle of blood from a wound, molecules thick. The enemy is cut, and falls. The hero doesn’t even watch.

Combat in Shinobi is designed to conjure that moment to mind in every encounter. Most regular enemies die in just a few hits, making it easy, once you get the hang of it, to cut through them in seconds each. When an enemy dies, they don’t die immediately. They freeze, as if in stasis. This gives the player an opportunity to chain kills, jumping and dashing between multiple assailants, trying to kill everyone on screen before an invisible timer ticks down. When that timer finishes, all the frozen enemies die at once, blood and death rattles covering the game space. If the player is able to kill all of the enemies in that timeframe, this occurs as a short finishing cutscene.

It elevates random encounters to violent theater

Outside of that one conceit, the rest of the game is a bit thin and clunky—mostly basic running and jumping with a camera that, as is characteristic for the era, seems intent on fighting the player every step of the way. But the rest of the game doesn’t matter much, either. That core conceit is everything Shinobi needed to be. It elevates random encounters to violent theater, one that offers the mystique and ineffable cool of its absurd action movie ninja protagonist to the player, to hold it for just a time. To perform it as frequently—and as elegantly—as they please.

When videogames went from two to three dimensions, film opened up as a wellspring of influence. The era of the Nintendo 64 and the original PlayStation were largely defined by trying to adapt the spatial and narrative logic of those media to videogames, with mixed and muddled results. By the time of the PlayStation 2, an early vocabulary of games-via-film had been established. Short movies, cutscenes, were regularly used to distribute narrative, often aping the work of big-box Hollywood films with varying levels of success. The viewpoint with which we watch characters in 3D space was called a camera, after the literal camera held by Lakitu on a fishing rod establishing the premise in Super Mario 64.

With that vocabulary established, games in the second generation of 3D-capable consoles tried to better understand how to reintroduce elegance and grace into play. Many of the types of play that succeed in 2D look silly, or unrealistic, when realized in 3D. Film, again, was a powerful influence here, from the Black Hawk Down (2001) military fetishism of Metal Gear Solid 2 (2001) to the increasing reliance on action movie mystique in games like Shinobi and its near predecessor, Devil May Cry (2001). The latter is considered by history to be more influential, cementing the legacy of kinetic cool that would become the modern “character action” game (see, again, Bayonetta.)

But Shinobi, in terms of grafting filmic heroic violence into its mechanics, leverages a type of success that Devil May Cry doesn’t. It focuses on one bit of that mystique and chisels it into simple perfection. Pure Bloodshed Theater. Just like I’d always wanted.

Stephen’s Sausage Roll gives you something to chew on

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Stephen’s Sausage Roll (PC, Mac)

BY INCREPARE GAMES

Sometimes, you look down at an item of food and wish it was twenty times bigger so you could enjoy more of that food. Other times, you play a game and wish it was twenty times harder so you could play it for longer. Luckily, both are the case with Stephen’s Sausage Roll, a puzzle game about a guy named Stephen who’s sole purpose in life is to grill two giant sausage links to perfection. Stephen’s Sausage Roll is not for the faint of heart or stomach. While the creator describes it as a “simple puzzle game,” it is anything but. You must time your sausage flips perfectly through elaborate contraptions, while also protecting your giant weiners from other hazards. Deceptively simple and outlandishly enjoyable, Stephen’s Sausage Roll will have you chomping on elegant puzzle game design for hours.

Perfect for: Professional eaters, fans of The Witness, pigs

Playtime: Until grilled to perfection

Final Fantasy XII and the glory of the grind

This article is part of PS2 Week, a full week celebrating the 2000 PlayStation 2 console. To see other articles, go here.

///

The first time I played Final Fantasy XII (2006), I didn’t get it. I liked it, I think—there was something unusually elegant about the game’s stern, philosophical conversations about honor, and the long loping lines of its battle system—but I got halfway through, hit a boss battle of five little goblins that wrecked my shit with a panoply of status effects, and called it a day. I believe winter break was ending, anyway. I mused over my failure to a friend, and he was appalled. “Just grind it out,” he told me, before we stubbed out our cigarettes and headed back into the bar.

This advice—“just grind it out”—may as well be the slogan for the Japanese role-playing game. I’m not sure when I first came across the term “grinding,” intended as a catch-all for the long hours these games require in order to progress, but I immediately loved it, perhaps because of the endless Clipse jokes it facilitated. Grinding is the barrier to entry for a JRPG, a genre that locks gonzo narrative and aesthetic riches behind hours of sheer, exhausting repetition. Grinding is a fanciful name for an act of intentionally mind-numbing repetition: the player traverses a specific area repeatedly in order to engage in battles, thereby gaining experience points and growing stronger. You might find a good “grind spot” and spend an hour, steadily at work there. Its corollary is farming, which looks identical but in which the goal is the acquisition of a certain type of item rather than a certain type of point. Is this boring? It is boring. Grinding leads to strength, of a sort; farming leads to wealth, of a sort; both are, intentionally, punishing.

Grinding is the barrier to entry for a JRPG

The grind is the central component of a JRPG; but, like sampling in popular music, it has refused to be confined to its origin genre, and has spread perniciously through almost every type of popular videogame. If you want to get better in a basketball game these days, you better hit the gym. If you want the top-tier guns in a shooter, you better have a few weekends to spend in multiplayer. The “clicker” genre of game isolates the grind to a single, curvilinear arc; Neko Atsume (2014) festoons that single line with cats and costumes and sprightly lounge music. MMOs take the concepts of grinding and farming to an illogical extreme, reasoning that if you’re going to spend your life rolling a boulder up a hill, you might as well join a guild. Destiny (2014), perhaps the most resonant title in the current videogame zeitgeist, combined the MMO and the shooter, enslaving a generation of young people in the process.

It is almost assumed that a player will comply. The grind is a surefire method of engagement, tapping into the same deep psychological impulses that keep people pulling the levers at a casino, or obsessively checking Twitter for fav-hearts. Each level we earn is a reward, and as those rewards become increasingly infrequent as our devotion to gaining them only increases. Eventually we rain hell on a field of merpeople, hours at a time, to move from level 45 to 46. These grinds are appealing to us on a deeply human basis, and I spent much of my adolescence in their thrall, but at some point I saw through the matrix, and swore them off. “I’m gonna die someday,” I’d grouse the moment a game demanded repetition, and then never play it again. Give me something short and designed or meaningfully hard, I reasoned; don’t only dare me to waste my weekend. That Final Fantasy XII and its band of merry hobgoblins demanded an afternoon spent grinding at all was reason enough to quit, as far as I was concerned. But something strange happened in the years afterward, as the grind seeped from the JRPG and contaminated so many other games: my feelings of animosity toward it softened. They were replaced, over time, by an easy, unhurried affection. A grind is like anything else in a videogame, I figured—an idea to be exploited, or just as easily refined. Bad grinds are a dime a dozen, hiding out in each minutely upgradeable ability or map full of collectible trinkets, not to mention the bargain-bin of cartoon-porn automatons currently filling the JRPG genre. But what, then, makes a good grind? I found a PlayStation 2 buried in my brother’s house recently, along with a gaggle of my old games. When those long blue lines started arcing and the stoic men began talking about war, I settled in, content to watch a handful of experience bars fill slowly, again and again, for dozens of hours. If there is such thing as a good grind, surely, it is Final Fantasy XII’s.

But why?

///

First, you have to commit, and getting there is harder than it may seem. There is a weird amount of turmoil around Final Fantasy XII. This is the case for every game unlucky enough to have the words “Final” and “Fantasy” in the title, but particularly true of this one, which is tagged in the history books as either underrated, experimental, or a travesty. Much of this is attributed to its fraught production, in which the fiercely cerebral game designer Yasumi Matsuno was brought in at the beginning only to be replaced by a more traditional company man later on. The story goes, among Final Fantasy XII apologists, that all of the good stuff is Matsuno’s, and all the shitty stuff his successor’s. Nowhere is this clearer than in the game’s bifurcated protagonists: Basch, a classically Matsunian protagonist of stolid demeanor and very serious concern, features prominently in the game’s intro, before the story detours to Vaan, a doe-eyed desert-boy who dreams of becoming a sky pirate.

Little of this is verifiable—Japanese game studios are a black box—but I’ll buy the narrative. Vaan was famously added to the game later in its production to appeal to younger players, and as such he can be almost entirely ignored, a protagonist relegated to popping in like Spritle and Chim-Chim from the back of the Mach 5 in Japanese racing anime Speed Racer. In one telling cutscene, Vaan appears to yelp “Race you to the beach!” to his pal Penelo, before Basch and a princess discuss royal bloodlines for several minutes. The game is riven between these two poles. Matsuno’s earlier works—Tactics Ogre (1995), Final Fantasy Tactics (1997), and Vagrant Story (2000)—are some of the most distinctly authored in the history of Japanese videogames, an impossibly rich stew of European history and JRPG melodrama, and Final Fantasy XII bears out many of those hallmarks. Allies of specious pasts join your party and fight nobly alongside you, only to peel themselves off upon a betrayal or noble disagreement. The games are fervently interested in the permeability of maps and the telling of histories; borderlines are seized and weighty books pored over. The games all feature economical menus, comic book font choices, and overcooked, feverishly nerdy translations. Final Fantasy XII, like its Matsuno predecessors, takes place in a sumptuous world, of vast, muted, naturalistic fields and timeworn cities drawn in gnarled, 45-degree hooks. Its dungeons represent an underworld inversion of these cities, at once more open and oppressively, envelopingly drab. Spending an afternoon in one of them has the deeply depressing feel of taking a bunch of pills, reemerging, and then taking some more, letting the murk rise back up to your neck. You wallow in it.

Tagged in the history books as either underrated, experimental, or a travesty

It’s great. The whole thing is great. I would recommend it fervently to anyone who likes all of the exact things I do and pretty much no one else. And yet: it does feel watered-down, compromised, as things drag on—not just Vaan, ending another cutscene with his fish-out-of-water yuckiness and his hands clasped incomprehensibly above his head, but the way those plot points of bloodlines and borders slowly get shaved into a mystical quest not even half as interesting. It’s like a bowl of gumbo that slowly turns into thin, reliable Campbell’s soup. One lavishly produced cutscene, early in the game and presumably while still under Matsuno’s supervision, is composed of a minutes-long monologue by a contentious new leader, making promises to the populace that seem too good to be true. It’s perfect Matsuno—political intrigue drawn in shades of gray. By the end of the game, that leader has turned into some sort of ancient, cartoon evil, soaringly repulsive.

This is where Final Fantasy XII apologists are thwarted. You want to like the game for its story, so much more somber and sober than any in the series’ prior entries, but it keeps giving you less and less to hold onto. Much Final Fantasy XII apologia focuses on the most distinctly Matsunian elements—the subtlety of its political setting, the decadence of its grammatical curlicues—but in the end, it’s Vaan who wins. The narrator that began the game was a king from a neighboring country of questionable allegiance; the narrator that ends the game is Vaan’s childhood friend, Penelo, speaking of dreams fulfilled. What keeps us playing, then, is not the story of the boy who wants to fly or the man who thirsts for honor, nor is it the princess or the sky pirate or the bunny lady (although the bunny lady is dope). What keeps us playing isn’t even the world, gorgeous and gray. We press on, like Matsuno’s noble knights, for the grind.

///

It begins with those arcing lines, blinking out of everyone’s heads the moment they step onto the first battlefield. Red lines spout from enemies, blue lines from your team, indicating each player’s current target. But these lines also represented a quiet revolution for the JRPG—a genre that, for all its narrative extravagance, upholds remarkably conservative design principles. Chief among them: a strict separation between the fields through which you run and the arenas on which you battle. You’d jog along in an old Final Fantasy, and then the game would decide it was time for you to fight, and so you’d be shuttled to another screen to take turns attacking a many-eyed pile of jelly before returning to the field. Final Fantasy XII’s first act of daring was to erase this delineation, letting you fight it out right on the field.

A fundamental rethinking of the grind as an aesthetic idea

Its other revolution was closer to heresy—a fundamental rethinking of the grind as an aesthetic idea. In the 60 hours or so spent playing a JRPG, perhaps 40 of those are spent in idle, inconsequential combat. One might further break the grind up between the trigger—what the player does repeatedly—and the lure—why she does it. The trigger in most JRPGs is to navigate a menu and select some form of attack. This is an opportunity to feel quiet mastery over its systems, and which in recent years has also come to include draining jump-shots, shooting an alien in its pneumatic little face, and feeding a bunch of lovable cats. You pull the metaphorical trigger, again and again, in a grind, because of the lure, something tantalizingly out of reach. In the classic JRPG, this lure is incrementally better equipment and statistics, but it might also be radical flair or a transformative new ability. Recent Bethesda games like Fallout 4 (2015) and The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011) hide comical powers at the top of their skill trees, while MMOs and dungeon crawlers let players festoon themselves in ever-more ridiculous assemblages of equipment. (The Persona games, memorably, combined traditional JRPG triggers with “hitting on classmates,” and combined traditional JRPG lures with “having sex with those classmates.” Somehow, they are some of the finest games ever conceived.) Many words have been written about why people play the games they do, and the lure of a grind is one of the clearest places to see those motivations at work. Why, exactly, would someone suffer such monotony? We also call going to work “a grind,” after all.

When we typically talk about the grind in videogames, then, we talk about how good the trigger feels, and how much desire the lure inspires. Final Fantasy XII gives zero shits about either of these. The lure is a board of unlockable abilities, initially appetizing but devoid of meaningful surprises. More daringly, the trigger is removed entirely. A standard JRPG’s combat, with each player and enemy taking turns attacking, upheld stately rules of battle, built on the mold of tabletop gaming. In Matsuno’s prior games, war was fought by tired, conflicted soldiers in swamps and forests and deserts, still taking turns but wading waist-deep through thickets of mud before doing so. In Final Fantasy XII, however, all of this is swept aside in favor of a system of gambits, which allow the player to program all of her characters. The gambits kick into action the moment the player is near an enemy—those red and blue lines start arcing up and out, action without the pull of a trigger. Final Fantasy XII’s critics balked, likening this to autopilot. You might tell an ally to attack an enemy on sight, and to heal teammates when weak. Ah, but in which order? And at how little health? At first, the gambits ask simple questions, but as the game moves on, more gambit slots open up, and divisions of labor take shape: perhaps the bunny lady hangs out with a crossbow at the rear, almost endlessly healing the princess, who is an angel of death; perhaps Penelo, god bless her, runs around stealing shit. The possibilities for roles aren’t quite endless, but you author them for your characters, hour after hour, in seemingly infinite variations. Each new locale represents a new mix of needs, and a slight reenvisioning of the programming of your team. The great rusty oil derricks of the Ogir-Yensa Sandsea force an aggressive pattern of healing, while the towering, labyrinthine spire of Pharos necessitates focused attacks.

But without buttons to press, what exactly are we even doing here? The grind always looks absurd to a spectator. Matsuno’s previous titles at least engaged in a sort of topographical intrigue, with enemies taking positions atop houses and retreating through alleyways, but in Final Fantasy XII, your characters will go so far as to position themselves on the field for you. And so for hours at a time—say, the hours I spent grinding before finally slaying those five giggling hobgoblins—the player merely moves the joystick toward the nearest enemy, watching the designed system kick into action. But this is where I might observe a third quality to the grind, sitting at the intersection of the trigger and the lure: its texture. The way the player strategizes toward that growth; the way the player is lead to understand the machine. The texture is the feel of an afternoon spent in the grind’s thrall. Because in practice, and with hindsight, Final Fantasy XII feels like the hale, staid JRPG, at the peak of its commercial popularity but just years before entering a period of long artistic neglect, reaching out wildly for new influences—synthesizing at once the onfield action of an MMO, the menu-driven perfection of a strategy-RPG, the slow crawl toward strength of the classic JRPG, and, in boss battles, the stop-and-start rhythm of a computer RPG. It is designed not around instant rewards or even eventual rewards but around the feel of the grind—nothing more and nothing less. It thinks in geological terms, confident that your understanding of mechanics is big—that you can feel the gears shifting at an almost imperceptible speed. That you could sit back and do nothing was perceived as the game’s greatest problem; it ends up being its richest reward.

///

A recently released videogame—okay, Far Cry Primal—stopped me, an hour or so in, to explain the process I would go about to upgrade my owl abilities. I envisioned immediately the moment, a few hours down the road, when an owl-related challenge would seem simply too much, and I would think: “I need to upgrade those owl abilities.” I quit instantly, of course. I will die someday, I thought, and my owl will be upgrade-free—a baby owl, unsuited to murder. This felt both fine and fair. A bad grind is worth quitting on. It feels terrific to stare at a huge platter of lures splayed out for your approval and to simply decline. I’m not sure which is more dispiriting: the way so many videogames impose the grind on players, or the notion that players have demanded grinds from videogames, ballooning out their runtimes in a tireless min-maxing of gameplay-per-dollar. The result, today, is more videogame than anyone could ever play, all eager-to-please and oozing content from every orifice. Final Fantasy XII is almost exactly a decade old, but in this context its most controversial ideas are more relevant than ever. The game asks only that we take our own time seriously, and spend it as if its supply were not infinite.

April 20, 2016

Welkin Road takes parkour from the rooftops and up to the skies

Gregor Panič has just released Welkin Road, a first-person grappling platformer for Windows, on Steam Early Access. It’s not only his debut game but also a sophisticated one that blends puzzles, freerunning, fast-paced grappling-hook maneuvers, and a “surreal skyscape.” The obvious comparison is with Mirror’s Edge (2008) in that it’s both a first-person platformer and eschews naturalism in favor of efficient design.

However, while playing it, the game’s cool, almost minty color palette, its inspired use of cloud imagery, and form-follows-function philosophy, led me to draw comparisons to the NES classic Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988). I wasn’t wrong. “Classic platformers have had a big influence on videogames in general, and as such their influence can be felt in Welkin Road as well, both directly and indirectly,” says Panič. “I think early platformers were based on a concept of putting gameplay and challenge before storytelling, and the same principle was used [here]. Furthermore, the scoring system and progression in terms of levels also draws inspiration from classic platformers.”

“make it feel almost as if the player was flying.”

A player’s success depends entirely on how well she uses the grappling hooks, which are really beams of colored light, or energy, that can be used either together or independently to achieve various distances and chained jumps. “The grappling mechanic was the first element of the game,” according to Panič. “Everything else was created around and as a result of this mechanic. For example, since the grappling and swinging is very dynamic and fast, adding parkour elements seemed like a natural evolution.”

Despite being influenced by the two-handed web-slinging of licensed games like Spider-Man 2 (2004) and Web of Shadows (2008), and by the first-person parkour of Mirror’s Edge, there’s no definite setting in the world of Welkin Road. You won’t find yourself taking on a police state or saving Mary Jane Watson from Manhattan’s latest monster of the week. “To be able to create certain tricks and puzzles, I knew I needed specific architecture that would be very difficult to base in a real-world setting. I thought that the game would be better off letting the [puzzle design] drive the creation of the architecture, rather than being limited to what exists in the real world.”

The first-time developer faced a great many challenges in realizing his vision, not the least of which was creating the art assets for the game. “Since I was working on the game on my own, and the player covers a lot of distance really quickly, it needed to be feasible for me to create a lot of geometry.” As for the use of clouds and the game’s celestial milieu? “It came about as an extension of the grappling. I wanted to make it feel almost as if the player was flying.”

Panič hopes the Early Access launch will give him an opportunity to add community-driven features such as “multiplayer racing, replay sharing, and a level editor” once the physics and level designs have been finalized. You can grab Welkin Road yourself over on Steam.

Interactive map lets you see the FBI planes circling our homes

In an analysis of over 200 federal aircraft using the flight tracking website Flightradar24, Buzzfeed has put together a visual compendium of where and when government planes have been flying over US soil. The results, concentrated overwhelmingly over urban areas, spanned across flights from August to December of 2015, providing a glimpse into what the government gets up to when we’re not looking. Buzzfeed makes the helpful choice to display this terrifying data using an interactive graph with flashing colors.

Weirdly, once you stop thinking about the meaning behind the map and start dragging and dropping it, it becomes a game: was your residence important enough to get noticed? The spinning lines over New York seem less intense when you zoom out, and Atlanta is so bright! Look at all the blue over Tucson! There’s nothing in St. Louis but there’s a constant dot around Buffalo, Missouri; a reminder to us all that Buffalo, Missouri exists. The envy makes perfect sense when staring at the colorful map, but becomes nauseating when you remember what the lines actually mean.

was your residence important enough to get noticed?

Clicking through the bright red flight patterns is similar to surfing Google Street View for possible day-trip destinations. It isn’t, and shouldn’t be, the same. It may seems like an enjoyable, interesting exercise to narrow down exactly which parts of suburban Los Angeles are being circled by government planes, until you realize you’re looking at exactly which parts of suburban Los Angeles are being circled by government planes.

gif via Buzzfeed

Although Buzzfeed would have us overwhelmed by the amount of information presented here, it takes more than foreboding circles to scare a denizen of the Internet in 2016. These graphs are scary, yes, and they’re important, but their impact is dulled by what we already know. The fact that the FBI has a host of front companies to cover these flights is more regretful than shocking, and knowing that surveillance planes circled local mosques in the wake of the San Bernardino shooting is important to understanding how our government operates. We already know that the NSA is reading all of our emails and that the FBI has no qualms about paying hackers to unlock phones; racial profiling from the literal sky doesn’t seem far-fetched anymore. If you live in the United States, these “revelations” have become commonplace. They’re just another one of those things we’ve learned to accept.

So, yeah, the conspiracy theorists, libertarian subreddits, and recent revival of The X-Files have a point: the government is most likely watching us from the skies. But what do we do with that information?

Simple: drag and drop it.

Explore the FBI’s attempts at being covert at Buzzfeed.

Southern Monsters, an upcoming game about living with disability

The southern forests of the United States are filled with stories of strange creatures. Tales of monsters. Things that look like a man, but too big and covered in too much hair to be a man. For some, the idea of these creatures draws them to search for these monsters. They explore the thick woods, looking for anything that will finally prove what they believe. And if they don’t find it—and they usually don’t—they go back out and keep hunting.

But for the main character of Southern Monsters this isn’t an option. The character you’ll play as in this narrative driven game is disabled. He spends most of his day behind the glow of a computer screen. He searches the web for monsters, living vicariously through those out in the world. “Cripplefoot shares my disability,” explains Kevin Snow, writer and creator of Southern Monsters. “A jacked up leg that requires a cane to minimize the pain of walking.” Both Snow and Cripplefoot also grew up and continue to live in the South.

“Cripplefoot grew up in the town that The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972) was filmed in,” Snow says. “He grew up going to these local monster conventions with his mom, living in this town with one claim to fame.” Living in that town is what made Cripplefoot (which isn’t the character’s real name, but his forum handle) so interested in monsters. But because the character is disabled he is trapped in his room. Unable to go out and look for them. So he uses cryptozoology forums to satiate his curiosity of monsters.

“I’m sure many people will have negative reactions”

What specifically drove Snow to make Southern Monsters was the “frustration” they had due to being treated as a disabled person. “I had a rough year.” says Snow. “Unsuccessful surgery, bureaucratic nonsense, unemployment because I couldn’t stand for more than 15 minutes.” The game became an outlet; a way to explain how they felt.

Writing a character like Cripplefoot isn’t easy—even if it’s one based on the writer’s personal experiences. The name alone might cause some to get upset. “I’m sure many people will have negative reactions,” Snow admits. “I call myself a cripple because it’s an aspect of my identity I’ve become comfortable with, but I wouldn’t use that word around another disabled person I don’t know.” Snow says that writing a character like Cripplefoot involves a lot of “soul-searching,” and they’re listening to people to make sure the story in Southern Monsters is nuanced and not hurtful.

Some of the people Snow is listening to include those who believe in cryptids. In the past few months Snow has started going to cryptozoology conventions and joined cryptid forums. “As an ‘outsider’ (I don’t believe in cryptids), I don’t want to exploit these people, even if I might poke a little fun at them in the game. I’ve met a lot of sweet folks, and made good friends,” Snow says.

The reason these people believe in monsters is varied. Snow has met people who love the outdoors and exploring them. Others seem more skeptical, but not of the monsters. “[Some of them] are intensely skeptical of academia, or the idea a scientist knows the wilderness better than them.” Whatever the reason for their belief they all continue to search the forests of the South, hunting for monsters.

Southern Monsters is currently being developed and will be released on PC later this year. You can check out its website for more information.

The false legacy of Grand Theft Auto 3

This article is part of PS2 Week, a full week celebrating the 2000 PlayStation 2 console. To see other articles, go here.

///

Up until Grand Theft Auto III (2001), it was standard to classify videogames by their central mechanics. There were stealth games, platformers, shooters, racing games, action-RPGs, turn-based RPGs, fighters, puzzle games, action-adventure games—and the expectation was that every game would feature a whole range of genre-informing actions and rules, typically interspersed with sections devoted to “story.” The problem is that this naming structure was a presupposition in itself: what if you wanted to do all of these things at the same time? What if you wanted to make the sights and sounds just as important as the shooting or the driving?

In a 2001 interview with IGN (one of the few he’s ever given) Rockstar co-founder Sam Houser honed in on his priority of making sure Grand Theft Auto III had “a look, a sound, a story and a feel that worked.” Working alongside film directors, writers, video producers, audio producers, and other connections from outside the industry, Rockstar created a sort of ragtag multimedia mash-up that, aside from boasting new tech, came together as a well-oiled, ultra-violent machine. Looking back on it now, the approach had an almost DIY punk aesthetic to it, rejecting the insular pillars of traditional game design and reaching outside the videogame sphere for direction. The list of artistic influences that show up in Grand Theft Auto III would read like the programming schedule for a Gen X fever dream: it pulls from Scorsese gangster flicks, house music and hip-hop, exploitation cinema, sketch comedy, chase films, and the city of New York itself, just to name a few.

The approach had an almost DIY punk aesthetic to it

It’s easy to forget now, but the open-world game wasn’t a novel concept when Grand Theft Auto III was released. Games like Driver (1999) and Crazy Taxi (1999) had already put us behind the wheels of beefy vehicles to cruise freely through city streets. The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) and Shenmue (2000) had already built open worlds to explore and characters to interact with. Even previous Grand Theft Auto installments featured comparably-sized worlds: when you look at Grand Theft Auto 2 (1998), for instance, there are very few base mechanics to differentiate it from the third. They had similar maps, similar missions, and similar lines of progression. If there was any unique accolade to give Rockstar after the release of Grand Theft Auto III, it’d be for their ability to mesh its various systems with world elements that felt diegetic.

“The cleverness of the GTA design is in the glue,” Rockstar vice president Dan Houser said in a 2011 interview with IGN, “not in the things that have been held together.” Most of Grand Theft Auto III’s proverbial adhesive came in the form of its then-groundbreaking data streaming system, which allowed the game to quickly retrieve information from the PS2 disc without cutting to a load screen. This meant that a player could walk up to a vehicle, press the triangle button, then seamlessly drive that vehicle off into the sunset without any interruptions. It was a major technical accomplishment for the time, but Rockstar backed its impact with subtler elements that helped to flesh out the world as a sandbox of possibilities. For one, they hid collectible pigeons across the city to encourage deep exploration in a pre-Achievement era. They placed ramps and hills across the map, allowing players to pull off stunts if they were on the run or just looking to satisfy their inner Evel Knievel. All of these ingredients helped to encourage a constant crossing-over between videogame genres. In tandem with the multimedia eclecticism of its world, Grand Theft Auto III conjured the illusion of “realness”: that the player’s actions had some semblance of weight in a world that lived and breathed, even if only in a digital sense.

In its immediate aftermath, this newfangled sense of realism set off a widespread moral panic about the impact of violent videogames. There had been ultra-gruesome splatterfests before Grand Theft Auto III, but something about granting players the agency to pick up, have sex with, and then murder prostitutes gave this game a disturbing gravity. “While the violent nature of the game will surely turn some people off and kids simply shouldn’t be allowed anywhere near it, Grand Theft Auto III is, quite simply, an incredible experience that shouldn’t be missed by anyone mature enough to handle it,” Jeff Gerstmann said in a 2001 review. While the most infamous outbursts of panic came in the form of Jack Thompson-types and parental word-of-mouth, there was a sense even among the critics and players that Grand Theft Auto III’s pioneering openness made it somehow dangerous.

Grand Theft Auto III was so alien that people didn’t only struggle to comprehend its immediate impact, but also had trouble tracing its legacy. At a point in time not too long ago, practically every reference to a 3D open-world action game after Grand Theft Auto III came with the words “GTA clone.” These sorts of clunky sub-genre monikers come around all the time. They’re used to supply more of those little boxes to tick when categorizing videogames. There’s the “Metroidvania,” a portmanteau of Metroid and Castlevania, meaning that at some point in the game progress will be blocked until the player finds a specific item. There’s also the “roguelike,” named after Rogue (1980), which is differentiated from a regular RPG due to features like permadeath and world randomization. “GTA clone” became another one in this long list.

Nomenclature becomes a straitjacket

The term worked well enough at first: games like Dead to Rights (2002), Mafia (2002), Saints Row (2006), and even Spider-Man 2 (2004) featured action-oriented sandboxes and looked a hell of a lot like Grand Theft Auto III. These games typically deviated from the formula in one way or another: Saints Row was (somehow) more crass than Grand Theft Auto, for instance, and Spider-Man 2 let you swing around the city on webs. For the most part, though, these successors felt like spiritual derivatives. Eventually, so many videogames used open worlds that the category outgrew the scope of Grand Theft Auto altogether. To call a game like Saints Row IV (2013) a “GTA clone” these days would be like calling a platformer a “Mario clone”: while the influence is clearly present, the genre has evolved so much that the comparison is practically irrelevant.

Still, Grand Theft Auto III’s categorical specter continues to loom over the open-world genre. As late as 2010, when Rockstar released the spaghetti western-themed Red Dead Redemption, critics lovingly mocked it as “Grand Theft Horse”. It was, after all, another open-world game filled with shooting and driving, except that instead of cars you galloped around on a trusty steed. Red Dead Redemption was far from another “GTA clone,” but its similar mechanical makeup made the comparison difficult to resist.

Now, almost 15 years after its release, there’s still the urge to describe open-world games by using Grand Theft Auto III as a frame of reference. In other media, this can be a helpful shortcut: point a shoegaze newbie toward My Bloody Valentine and the Cocteau Twins, and it becomes much easier for them to delve into groups like Slowdive or The Jesus and Mary Chain. But when your genre of origin comes pre-packaged with such specific expectations, the nomenclature becomes a straitjacket: think, for instance, of the baggage that comes with a pejorative genre designation like “walking simulator”. The name may have started as a joke for emotionally-charged first-person games like Dear Esther (2012) and Gone Home (2013), but it’s grown into a stigma of its own.

To view Grand Theft Auto III as the mere ancestor to a couple back-of-box features is to undermine the details that fuel its experiences. Back in 2001, there was no linguistic scaffolding that could handle the possibilities it presented. But now, as videogames get even more complex—tackling subjects like mortality, fraying relationships, first loves—it becomes increasingly inept to reduce their value to the details of their mechanical inner-workings. Instead, the act of evaluating a videogame should be an active, personal process that seeks to expand instead of contract the possibilities of interactive media. The eventual upgrade from “GTA clone” to “open-world” was a step in the right direction. But the open-world designation has its own limitations: with open universes just on the horizon, even that phrase seems destined to fail.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers