Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 130

April 26, 2016

Waiting Rooms is a building-sized game about the struggles of bureaucracy

When I left the Rubin Museum of Art’s Waiting Rooms exhibit, I had 14 yellow tickets, 24 pennies, and a form with a picture of a unicorn on it in my pocket. It sounds like the random hodgepodge of garbage a quirky Tina Fey character might carry, yes, but within the world of the exhibit, it was a veritable fortune.

Created by architect Nathalie Pozzi and game designer Eric Zimmerman, Waiting Rooms is a building-sized game about bureaucracy. In it, the museum is divided into a series of nonlinear rooms, each with their own arbitrary task to complete as well as a required exit fee of either yellow tickets or pennies. To start, groups of players are first given a certain number of tickets based on a hidden set of circumstances, which they can then distribute between each other how they see fit. Then, players are free to split up and explore the rooms in whatever order they wish, so long as they can afford it. Players who are able to pay the exit fee are free to leave a room whenever they want, but those who cannot must instead wait for a set amount of time before proceeding. The tasks also carry the opportunity to earn tickets/pennies, but this usually comes at a fee of both tickets and time.

The end goal of Waiting Rooms is not clear, and maybe that’s the point. In my playthrough, I focused on getting higher and higher into the building, but I had no idea if I was actually reaching the end of the game or moving farther away from it. Eventually, I became less concerned about winning the game and cared more about achieving my own personal goal, an experience I seemed to share with many of my fellow players.

I never got to see the top of the staircase

With each room presenting a new challenge and arbitrary set of rules, I felt a bit like Chris Evans moving through the many highly varied train cars in Snowpiercer (2013), or maybe a spiky haired protagonist making a game-of-death tower climb in an anime (Yu Yu Hakusho comes to mind). In the rooms I visited, I played a combination of rock-paper-scissors and prisoner’s dilemma, sat waiting in an elevator until someone on the floor I needed to visit happened to call it there, was forbidden to speak while being randomly assigned a direction to explore, and eventually reached a roadblock in the form of a staircase, a currency exchange, and a room that gave players pennies in exchange for filling out forms. The staircase required 10 tickets to climb it, so I kept moving back and forth between the form room and the currency exchange, trading my freshly earned pennies to try to grind out the necessary tickets. Unfortunately, I never got to see the top of the staircase, as a gong soon rang out signaling that I was out of time. I did, however, leave with a sweet unicorn drawing, which I had doodled on my form to kill boredom while waiting to hand it in.

After the game wrapped up, we were lead to a brief Q&A session where players asked the designers questions as well as shared their experiences. For some, like myself, other players were surprisingly kind, giving advice and tickets/pennies when needed. Others, however, were not so lucky. One group, it seems, had a single member steal all their tickets at the beginning and leave before they could do anything about it. Some bucked the system entirely, staging a socialist revolution where they pooled tickets together and did as they pleased. Yet another person just left, frustrated with the whole thing.

I asked Pozzi and Zimmerman about their goals with the project. “I think that Waiting Rooms in part is a way to express both the value and the arbitrariness of human systems,” said Pozzi. “I have experienced some truly absurd and hilarious bureaucratic scenes,” she explained, referencing her experiences dealing with immigration and customs. She spoke about an experience where she had waited in a long line of angry people while going through customs, only to be greeted at the end by an officer who was all smiles. “It was a moment of true, unexpected, intentional kindness within a very cold and inhuman system,” she told me. She asked why the officer was being so kind, to which he told her that he wanted to prove that New Yorkers are nice. “For me, Waiting Rooms is not just about designing social rules but in how those rules become a personal experience that is different for each visitor.”

Zimmerman mirrored this sentiment, talking about what players had told him during previous showings of the game “For some of the participants, it represented the genuinely unpleasant hell of navigating a bureaucratic system,” he shared. “For others, it was a kind of Willy Wonka adventure full of mystery and magic.” I asked him what questions he would like us to be asking ourselves as we leave. “I’m not sure,” he said, “but I am so happy that everyone can have their own individual, personal experiences.”

“I like the way that Waiting Rooms plays with value”

On my way out of the museum, I was stopped by those who had revolted, where they gave me all those extra pennies and tickets I mentioned earlier. During the game, this would have been a boon, but now, they had become worthless. The one goal I had set myself to pursue for so long—get more tickets—suddenly meant nothing when divorced from the system that gave it meaning, leaving me feeling like an old miser who had wasted my life trying to strike it big, and was now wondering what the point was.

Later, I emailed Pozzi about her thoughts on this issue of how we assign value in our culture. “I like the way that Waiting Rooms plays with value. There are several currencies in the game, and there is a tremendous degree of arbitrariness about whether you end up with many or few resources,” she told me. “Time seems to be the only resource that is actually ‘free.’ But actually, time is the only currency that has a deep, non-arbitrary value outside of Waiting Rooms.”

So much of our culture requires us to sacrifice our time in pursuit of wealth. Waiting Rooms asks us if that trade is really worthwhile.

Waiting Rooms has recently wrapped up its final playtest at the Rubin Museum of Art. While there are “no definite plans to show it in the future,” Pozzi and Zimmerman look forward “to more testing and collaboration in the next version of the project.” For more, visit the Rubin Museum’s website.

///

All photos taken and provided by Ida C. Benedetto.

Creators of Never Alone to explore Ukrainian folklore in their next game

Never Alone (2014) is a game steeped in culture. Not just for videogames in the role of cultural accuracy, but in preserving the waning history of Alaskan Natives. The game, based on Alaskan Iñupiat (a hunter-gatherer indigenous people of Alaska) folklore, was an anomaly in the videogame space when it saw release. It was developed in an almost unheard-of collaborative effort between Upper One Games (the first indigenous-owned game developer and publisher in the U.S.) and the nonprofit group Cook Inlet Tribal Council. Both parties sought to develop a game that not only entertained players, but also enchanted them with education in a befitting portrayal of Alaskan Native culture. The Art and Creative Directors of Never Alone, Sean Vesce and Dima Veryovka, have now returned with a new worldly, Ukraine-focused project: The Forest Song.

The Forest Song is a first-person adventure game, already differing from the core side-scrolling platforming of Never Alone, but remains rooted in its sensible goal to educate players on different cultures. The Forest Song is based on Lisova Pisniya, a classic Ukrainian drama about a peasant that happens upon a powerful Forest Spirit, and their chance meeting opens up a realm of mishappenings between both the supernatural and humans’ world. Just as with Never Alone, Vesce and Veryovka (and the rest of the Colabee Studios development team) are consulting Ukranian culture and folklore experts every step of the way.

Led on their cultural expedition to the Volyn region of western Ukraine by scholars from the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, the scholars and development team of Colabee interviewed a variety Ukrainian residents about their life experiences. In one shared video of the first expedition, two Ukranian villagers that share a farmhouse (Pani Dominika Checkun and the 89-year-old Pani Paraska) display their renowned talents in traditional singing. In other moments of their expedition, Colabee visited a local fashion show celebrating traditional Ukrainian clothing, and even met a Chernobyl survivor, Pani Svetlana, and interviewed her about her experiences.

Consulting Ukranian culture and folklore experts every step of the way

The Forest Song is a project that creative director of Colabee Studios Veryovka holds dear to him, as he wrote on the game’s site. “Ukrainian mythology has so much to teach us, but for people outside of Eastern Europe it has remained largely inaccessible,” wrote Veryovka. “Having grown up surrounded by these magical tales it is so exciting now to be able to share this part of my culture with gamers everywhere.” The Forest Song is currently being developed for consoles, along with specialized VR content for a fully immersive experience.

You can follow The Forest Song’s development on Colabee’s website .

UNICEF combines 500 photos of war victims to give the refugee crisis a face

It’s difficult to grasp the meaning of a global refugee crisis. For much of the world this mass displacement is a moment on a newscast, a headline to be skimmed, a statistic to move us, but only briefly. UNICEF’s Sofia is the latest attempt to give us a deeper understanding. Sofia is a 3D animated girl created using 500 images of actual children from places affected by conflict, such as Ethiopia and Ukraine. The campaign worked with Getty Images, animators who worked on Planet of the Apes, Tintin (2011), and Avatar (2009), and the marketing agency Edelman Deportivo to culminate these images into a wide-eyed child with a heartbreaking story.

Sofia tells us in a clear voice who she is, her age, and what she has gone through. And in the end tells us she is not real. “I am the face of all the children suffering from emergencies no one talks about.” The inspirational music swells as she looks down, and then looks back into your eyes. UNICEF’s goal is clear: give a face to the unseen pain of many.

perhaps this animated spokesperson can call out to our humanity

There have been many efforts towards humanizing this global epidemic. Hearing the numbers of people displaced by conflict and how many of them are children is one thing. But UNICEF hopes to bring us closer to the people those numbers represent. Personal appeals, like Sofia’s, intend to bridge our divide. As yet another intersection between high-tech tools and social advocacy, Sofia joins the likes of Clouds of Sidra (2015), a virtual reality documentary that brought viewers into the world of a young girl at a Syrian refugee camp. But while a VR film has limited accessibility and viewership, Sofia gives anyone with the Internet and a computer a way to get emotionally involved in this global epidemic.

Although it is clear that UNICEF’s goal is to make Sofia appear as real as possible, delivering her message through animation may be one of the project’s more effective design choices. In Understanding Comics Scott McCloud talks about the benefits of abstraction in cartooning, positing a theory that when we see a realistic face we see an “other,” but when we see a cartoon we see ourselves. He argues that if he were to draw himself realistically, “You would have been far too aware of the messenger to fully receive the message!” Although Sofia’s abstraction is minimal, it is there, and it might create a space where we are more open to seeing and understanding.

More abstraction might have even helped Sofia deliver the message more effectively. While it is meaningful that she is an amalgam of 500 real-life children, which may strike a chord with some viewers, Sofia can still only tell one story. No single story can capture such a large diaspora, but perhaps this animated spokesperson can call out to our humanity, and open the door for us to hear more.

You can find out more about the work UNICEF does on their website.

Binary Domain and the importance of shooting robots

A third-person shooter in which you destroy thousands of robots using big guns and lots of bullets. That could be a description for both Binary Domain (2012) and Vanquish (2010). They’re both science-fiction and both published by SEGA. And each of them is styled in a way that might be described as “very Japanese.” But where Vanquish quickly gets old, Binary Domain is alive, vibrant, and keeps you hooked until its end. The difference is revealed in the characters. More specifically, it’s found in the cutscenes. As game-makers continue to explore new methods of interactive storytelling, I understand why cutscenes have become, to some extent, non grata. But the cinematics in Binary Domain, as well as pushing forward the game’s smart, swift plot, are short films unto themselves.

In these cutscenes, Binary Domain frames its human characters as precisely that—if this is a game about the differences between men and machines, then the occasional intimate moments shared by Binary Domain’s cast (the flashback to Dan’s childhood is an eminent example) tell that story. Vanquish, by contrast, is uninterested in people. Its climactic twist, whereby your squad leader and even the American president turn traitor, feels cheap and cynical; an ugly plot turn that sacrifices the game’s humanistic theme for traditional espionage intrigue. Up until that point, you’ve fought and died alongside dozens of US Marines, united in a battle against malicious robots and a cyborg antagonist. When the game spins 180 and announces “actually, your comrades have betrayed you,” it’s a glaring and unfortunate inconsistency. This is a notable contrast to how Binary Domain draws clear battle lines between man and robot—sure, they are muddied in the final act, but gracefully so. Whereas Vanquish goes the other direction, implying similarity between humans and robots by revealing that people are just as abhorrent as mass-murdering machines.

in between two loathsome genres of videogame, it finds genuine sophistication

Binary Domain shows itself as a game appreciative of its audience and their ability to identify adolescent cynicism. It suggests that men and robots are united not through shared shortcomings, but universal goodness. The machines, too, have feelings and compassion—when the child Dan destroys a robot we’re lead to believe this was because it was attacking his mother. In fact, Dan lashed out because the robot had failed to protect his mother from his abusive father. Vanquish wants its players to doubt the entire world. Binary Domain, smarter and more mature, finds the goodness in all its characters, and is a more interesting game for it.

Two other cutscenes deserve honorary mentions: An early scene in The White House situation room is only a few minutes long, but has one of the best twist endings in all games. The human being you least suspect, and who least suspects it himself, is the one who turns out to be the machine. The other scene is the arrival of the Hollow Child robot at Bergen headquarters—the sequence that provides Binary Domain’s most lasting image, of the man with half his face ripped off, revealing circuitry underneath—which wonderfully sets up the game’s emotional through line. With some nasty gore, Binary Domain goes straight for the audience’s stomach and, like Dan, players are instinctively and immediately repulsed by the men-machines. But by the end of the game, to an extent at least, they’ve gone through the same process to gradually understand as the characters under their control. From sharply evoked suspicion and disgust, they’ve grown to like Faye and Cain, the two android characters. Players’ attitudes have matured. It’s another example of the optimism that’s at Binary Domain’s heart: with more exposure to and understanding of the “other,” people’s prejudices will soften. Empathy prevails.

The relationship between Faye and Dan is also lovingly played out. It begins with Dan’s frat boy catcalling, transitions through their sex scene and subsequent fall out, and ends with an embrace plucked straight from ’50s Hollywood. In fact, it puts in mind a simple metric for how to write romance: the two lovers need to have got together, and had sex, before the final act. Anya and B.J. do this in Wolfenstein: The New Order (2014). It helps them seem not as characters that are in love only in a vague, theoretical sense, but people that have a physical, biological attraction to one another. This type of romance also eliminates one of the most awful tropes of the male power fantasy: the idea that the woman is a kind of reward for the man once he has completed his mission. In Binary Domain, Faye isn’t a prize for Dan (or the player) after he’s saved the world. Simply because they’ve slept together, and experienced some kind of emotional consummation before the game’s end, Dan and Faye’s relationship comes across more meaningful than romances in other shooters—it exists outside the paradigm of typical masculine fantasy, and Faye feels like something more than a status symbol for Dan to acquire. Dan matures, from a gawking bro to a genuine lover. Faye, unlike so many women in videogames, is personable and independent. Though she is literally part machine, she feels more human than most of her entirely biological contemporaries. In these two characters, and their romance, we once again feel Binary Domain’s optimistic attitude regarding human beings.

it’s difficult to keep yourself from grimacing

When was the last time you played a boxed shooter, with AAA production value, that was at least eight hours long and didn’t involve killing a single human being? For me it was Portal 2 (2012), and even that falls more beneath the rubric of puzzle games than of shooters. Binary Domain has you dispatch thousands of enemies, using hundreds of thousands of bullets, and yet your endgame body count is zero: very few other videogames, especially those with a 15 age rating (in the UK), can make that boast. And it is a boast. Referring back to those cutscenes, one thing Binary Domain absolutely understands is consistency of tone. Never too serious, never too daft—at the best of times it’s akin to one of Spielberg’s adventure films, a veritable summer blockbuster of a game, appropriately replete with broad appeal. Throw human enemies into the mix and Binary Domain would become much dirtier. Its electric pace and offhand jokes, instead of entertaining, would seem crass, the way Uncharted, at times, can seem crass.

On the contrary, Amada Corporation’s robots make for terrifying opponents and blasting chunks out of them is as grotesquely satisfying as spilling human blood. In fact, it’s outright violent. They are not people, but when the robots’ heads, legs, and metallic torsos go twirling into the air, ripped from the CPU by your pneumatic drill of an assault rifle, it’s difficult to keep yourself from grimacing. It’s a game of high action and high emotion and brilliant for it. Timidity is boring. Clemency is boring. It’s not CGI gore but the videogames that are satisfied with being safe and genteel that turn my stomach. But at the same time, shooters—especially as of late—have grown so very ugly. Churlishness has become insensitivity, boisterousness sexism and escapism is now complete ignorance. Binary Domain is violent and often adult, but intelligent and graceful nevertheless—in between two loathsome genres of videogame, it finds genuine sophistication.

And that’s much more than can be said about Vanquish, and any other game that doesn’t meaningfully consider the targets it throws at you to shoot. When, in the game’s final act, your enemies become humans—instead of the robots you were tearing apart before—the game barely acknowledges it. You kill them, thoughtlessly, as you had done the machines. The message is once again dishonest, self-loathing, and clear: we are all equally worthless. Vanquish may share its theme and fast action with Binary Domain, but only the latter has enough love for people to not continually and meaninglessly throw them before bullets.

April 25, 2016

A game designer speaks to how systems thinking can benefit journalism

Systems thinking is an approach to analysis, focusing on how different parts of a system relate to each other, and how they change over time and within the context of larger systems. That’s lot of words to process, but luckily Nicky Case has sketched up a great reflection on systems thinking in relation to journalism for those of us who may not be aware of the basics. You may recognize Case from their past work in describing how systems work through interactive simulations. After attending a two-day workshop on systems thinking for journalists, Case sketched up a blog post to explain the ideas further, particularly for those who aren’t as familiar with the concept.

First, Case establishes the difference between conventional and systems thinking, which is straightforward: the former is a linear cause-and-effect, while the latter is nonlinear cause-and-effect. Then, they expand with some advice on not only how to write stories about systems, but stories with systems. For Case the one overarching concept to remember is that “at the philosophical, emotional core of system-stories: empathy. Individuals may have noble motives, but are constrained by the system. ‘None are to blame, but all are responsible.'”

The notes Case provides from the event are also illustrated, visually showing how to use systems thinking to positively affect the world around you. In relation to journalism, systems thinking can be put to good use by helping a writer understand the connections and intersections that make the story their covering complex. All of it works toward making a healthier system overall and on a larger scale. As Case reminds readers, “You don’t fix systems; you can evolve & influence ’em so they can change themselves.”

Below the summarized workshop notes are Nicky’s personal reflections that don’t have as much context but provide a more exclusive view. There are pages of these sketches that dive deeper into how systems thinking can benefit journalism, with language that is easier to digest (like “What the diddly do dang is systems thinking?”).

A major takeaway from these notes for journalists is that applying a systemic way of thinking “can help all sides see that their enemies aren’t each other—but rather, they have a common enemy: the system.”

Read through Case’s entire article on systems thinking and journalism right here.

A cyberpunk pottery game gives you something to think about

When Ludum Dare announced the theme for its 35th game jam would be “shapeshift,” it triggered something within the mind of Deconstructeam’s creative director, Jordi de Paco: a memory about a short story he once read in the book Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking (1993). This story, combined with a couple of other books on zen, and de Paco’s own interest in transhumanism, led to the creation of the studio’s game jam project, Zen and the Art of Transhumanism.

The aforementioned short story, incidentally, tells of a pottery master and his students. The master divides his students into two groups: one that will be evaluated based on the quality of their pottery, and the other that will be evaluated based on how many pottery pieces they can create. In the end, the best pottery creations came from the latter group. According to de Paco, this story had a profound effect on him. “[The story] changed my take on making games,” de Paco said. “I was so worried about making great pieces [that I was] always sabotaging myself, not being able to create freely due to the pressure… so this time I took it way too literally and made a lot of pots.”

Zen and the Art of Transhumanism, described as “a cyberpunk pottery game about improving the human race through technology,” puts players in the role of a robot tasked with making implants to fulfill the desires of various people. The implants, which are made in the same way as pottery, can do everything, from improving a person’s online social status, to making them stronger, to even extending one’s life.

But in a universe in which the technology has advanced to such a point, how was pottery, of all things, chosen to be implemented into the game? “I like to mix ancient arts with sci-fi,” explains de Paco. “Like a tattoo artist [that] burns silicon circuits into yakuza robots, that kind of concept feels very attractive for some reason, at least to me. Also I wanted to have a fun toy in my game, which I don’t usually have.”

Getting a new client, checking their profile to see what they desire, choosing the appropriate implant, then making and installing it is the basic gameplay loop of Zen and the Art of Transhumanism. At the table where the implants are made, players can choose which of the four carving tools they want (and often need) to use to shape the clay. A holographic pattern detector will turn green when the clay and implant shape match, or are roughly the same.

the relationship between the human race and technology

There was an idea to add a shop where players could do odd jobs to earn money, and then use their gains to buy new pottery tools and designs. It didn’t make it into the final game. At one point, there was also a time limit to the game, but was ultimately removed because it “detracted from the intended experience.” That experience is an interesting one, and one that may have some weighing the pros and cons of the game’s main idea: the relationship between the human race and technology.

“I’m happy with whatever answer a player extracts from the game as long as the game gave them something to think about,” said de Paco. This is something that de Paco and team previously achieved through violence and moral choices in Gods Will Be Watching. And as with that game, Zen and the Art of Transhumanism won’t be the last time we see transhumanism and science-fiction explored by Deconstructeam. Pottery, however, may have run its course.

You can download Zen and the Art of Transhumanism from the developer’s itch.io page. Their previous big release, Gods Will Be Watching, is available on PC, Mac, iOS and Android.

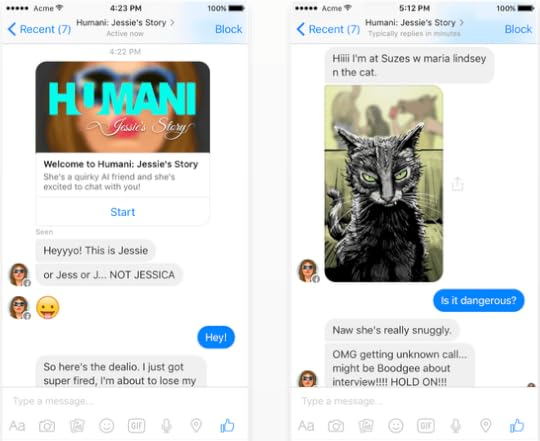

Humani: Jessie’s Story turns the sitcom into a chatbot game

Jessie came into my life a couple of weeks ago. She was announced by her creators at PullString at the beginning of April as part of a conversation-based narrative game called Humani: Jessie’s Story, which you play on Facebook Messenger. You only need to say “hi” to meet Jessie, who is a 20-something girl who is not only experiencing a quarter-life crisis, but also looking for a job, a boyfriend, and a new apartment — all in the same day. You go along for the ride.

As Jessie gives you the lowdown on how to get to a job interview, how to find the best shared house, or how to escape from her friend’s boyfriend after invading his flat, you may feel like you’re simply helping one of your friends and not actually talking to a chat bot. Besides the fact that the conversations in Humani are very well written, using a popular messaging service like Facebook Messenger makes it feel remarkably closer to our everyday online chats.

Rod Humble, chief creative officer at PullString, says they are still interested in using other apps for the next releases. “Humani: Jessie’s Story represents our plan to offer future products to broader audiences on a variety of platforms,” he says. “In the future you can expect to see PullString conversation-based games on several messaging services and platforms, such as Skype, Slack and others.”

Humble goes on to say that PullString’s goal was always to create a new form of entertainment and bring conversation to as many digital and physical characters as possible. Humani: Jessie’s Story is both the latest reflection of that goal and also an important asset for chat bots and AI development. “I think this will become a commonplace in the same way as interacting with a computer is now,” says Humble. “If you buy into that concept —and more and more people are certainly starting to —then it seems obvious to me as an artist that we should use chat bots to create new kinds of art and storytelling.” Humble also believes that, “in many ways, this is a very ancient tradition that we have lost, the notion that you can guide and question the storyteller or even the hero within a story.” He adds that this is “a powerful tool which goes back to the Homeric tradition.”

they wished that Jessie could be their real friend

PullString knew, since the beginning of the project, that they wanted the experience to be “light and comedic.” Humble says part of that decision was “the desire to take advantage of the text/chat format itself, which lends itself to these types of exchanges.” It’s in approaching the narrative from this angle that led to Humani becoming an exploration of different types of characters and situations heavily based on the tropes of contemporary sitcoms and movies. “We settled on a young, urban woman having a quarter-life crisis and generally trying to make her way through the world,” says Humble. “You’ll see the basic absurdity of Jessie’s situations reflected in such sitcoms as New Girl (2011-present) and Broad City (2009-2011), in movies like Bridesmaids (2011), and embodied by actresses like Amy Schumer and Kristen Wiig. All of those served as an inspiration for the character of Jessie and the game experience itself.”

While Humani being located on Facebook Messenger achieves that feeling of it being part of our reality, PullString made concessions to make sure it didn’t feel too real. For instance, images are illustrations rather than photographs, and Jessie only has a fan page and not a personal profile on Facebook. The reason for this is that they wanted to take Jessie to “a fun, lighthearted place,” and are not looking for Jessie “to pass the Turing test or for people to think of her as a real person, but to immerse them into the life of a fascinating character during a particularly eventful day in her life.”

This means Jessie has limitations. She is not an open-world chatbot, although she has several possibilities when in her dialogue. If you don’t help her to choose between one option or the other, she will repeat the question until you make one . Also, sometimes she might ask for your advice on which word should she use for research or to complete a task, which can result in a sillier outcomes when, for example, you she asks for a slogan for “Butt.” Outside of this, Jessie has been designed only to tell a specific story and to “flex [PullString’s] storytelling muscles.”

Soon PullString will be making the platform used to create Humani available to other developers. Humble argues that, given the rapid emergence of chat bots, there will be a “thriving market for the PullString content authoring platform.” He says that in the past few months they have seen an explosion of interest for chat bots on communication and messaging services like Skype, Slack, and Facebook Messenger, with ends such as entertainment, customer care, and brand experiences. “Because we have spent the last four-plus years building and refining what at this point is the most advanced tool available, we feel we are in an ideal position to take advantage of the opportunity in the marketplace,” he says.

Meanwhile, Jessie has already been providing good laughs and some fine entertainment for those who enjoy her energetic personality. As a matter of fact, Humble says that some players have said they wished that Jessie could be their real friend. “There has also been an interesting reaction based on demographics,” he adds. “The language of texting turns out to be quite generational, so it is very natural for certain generations to interact by text. They are comfortable reacting to memes, emoticons, and Internet slang, which in itself is quite split by various demographics. In fact, I would suggest that Internet slang is the fastest evolving language in the world.”

You can play Humani: Jessie’s Story on your computer or mobile device, provided you have Facebook Messenger installed on it.

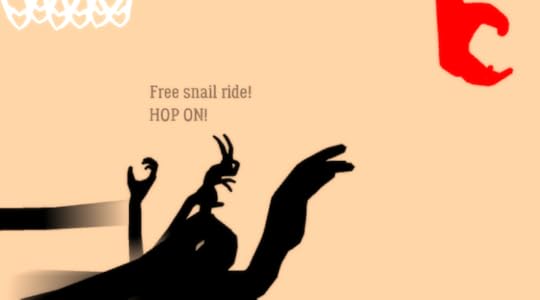

Shadow of the Red Hand, a game made entirely out of shadow puppets

Created for the latest Ludum Dare game jam, the theme for which was “shapeshift,” Shadow of the Red Hand is a game made entirely out of shadow puppets. In it, the player’s hands take on the role of a rabbit, and must hop away from the evil “Red Hand of Doom” as it chases them through the ever-changing puppet show that they call home.

The result is more challenging than the cute children’s-slumber-party motif lets on, with platforms often moving in unpredictable ways due to the many different shapes a hand can take. “Will this one become a fist?” I asked myself while playing. “Will this one open its palm?” It reminded me of going in to fist bump someone before realizing that, no, the other person was actually trying to high-five all along.

“Hands are shapeshifting creatures,” explains Andrew Wang, the game’s creator. “The game only contains a single 3D model—a hand. But that model is animated and angled in different ways so that its shadows shape the entire world.” This allowed him to create “the illusion of platforms, birds, rabbits, crocodiles, and other creatures” while only using one universal model rather than creating a separate one for each new character. A clever choice for a game made over a weekend.

“Hands are shapeshifting creatures”

It’s worth pointing out that, with enough time, people, and patience, one could theoretically recreate Shadow of the Red Hand at home with no computer whatsoever. It makes for a charming reminder of the amazing things our bodies are capable of, as if to say “Woah, dude, look at my hand!” No, but seriously, look at your hand… it’s so strange.

You can play Shadow of the Red Hand over on its Ludum Dare page. To play other entries from this year’s Ludum Dare, visit its website.

The beauty of Hayao Miyazaki and VHS glitches

The first time I ever watched Princess Mononoke (1997) was on a grainy bootleg from a relative. I was a kid, maybe nine-years-old, but the otherwise beautiful film’s terrible quality was ingrained in my psyche. Since I was only nine, its fuzziness didn’t bother me. It wasn’t until I was much older, and more appreciative of the crisp existence of blu-rays, that I was able to rewatch the film and re-fall in love with it all over again.

Still, that first grainy take on the film rests as my first “true” experience with a Hayao Miyazaki film, and was my gateway into the legendary animator’s other classic works. While my first viewing of a Miyazaki film wasn’t on an arbitrary VHS like many others, Hyo Taek Kim’s glitch art series of distorting Miyazaki’s imagery, chimes into a similar feeling. That glitch-prone, off-kilter feeling a lot of our generation share in experiencing Miyazaki’s magic for the first time in our youth—even on something as shabby as a VHS tape or bootleg.

“Ghibli’s the master of creating emotions”

Kim, a Brazilian-Korean designer, isn’t a stranger to channeling his love for Miyazaki into his works. In the past, he’s divvied up films into minimalistic color palettes (including some of Miyazaki’s films), and aptly redesigned Andy Warhol’s classic Campbell soup can series, but theming the cans after Miyazaki’s filmography. With the glitch art series, Kim marries the distorted-VHS aesthetic that he grew up with to the Miyazaki characters he loved the most, creating a wholly unique blend of nostalgia and modern (since Kim even borrows characters from Miyazaki’s post-90s films). As Kim told The Creator’s Project, “Ghibli is the master of creating emotions, and I love to revisit these moments whenever I get the chance.” Whether it’s moments of nostalgia in watching VHS tapes, or even just the feelings of empowerment that emit from the films themselves.

Characters from Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001), My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), Ponyo (2008), Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), and Princess Mononoke are all represented in Kim’s discolored homage to VHS glitches. There’s something palpably nostalgic about glitches, whether they’re of the videogame variety of restarting a game over and over again to make it work, or the bastardized quality of collected VHS tapes. The VHS-glitch harkens back to being a kid, and watching your favorite movie over and over again, that is, until the tape dies.

You can purchase prints of Kim’s Miyazaki glitch art here .

Via The Creator’s Project .

I Took My Outdoor Education Professor On A Canoe Trip In Twilight Princess

When you think of outdoor educators, someone like Z (name changed to protect privacy) probably comes to mind: grey hair in braids, wearing a wool sweater with jeans and mukluks, she uses her university email account with reluctance and sees devices as a harbinger of the end-times. Her pedagogy born out of her environmental activism in the 70s, Z will talk your ear off about “indoor kids” and the “wired generation,” and how the only solution to the oncoming apocalypse is taking technology out of kids’ hands.

She’s also curious about The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess (2006). I’d applied to her program stream as part of my teachers’ college degree on a whim. Part of the application package asked for a personal artefact expressing our teaching philosophy in a way that a resume couldn’t. I’d submitted—in hindsight perhaps a little too boldly—a cross-stitch I’d made of the opening scene of the battle with Red in Pokémon Crystal (2001); she later confessed that she’d taken me into the program based on that artefact. Z can knit a pair of socks out of tumbleweeds and make a delicious stew out of meat she’s hunted herself, but figuring out how to articulate the moment where the “natural” and the “virtual” collide escapes her.

Z will be speaking at a symposium on canoeing where, for the last few years, the organizers have noticed a decline in younger attendees; there’s a certain staleness to the air, and there are only so many times one can bemoan kids these days. Something fresh needs to find its way into the program. Z asks me if I’ve ever played a videogame in which a character goes canoeing.

And so we find ourselves, some weeks later, setting up my Nintendo Wii in an empty classroom, and I’m booting up Twilight Princess.

///

Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Wilderness (2005) has left its mark all over the outdoor and experiential education field. With urgency and excitement in his tone, Louv describes the causes and effects of “Nature-Deficit Disorder”, linking a lack of nature in our childrens’ lives to everything from obesity to depression. Physical and emotional development in young folks, he argues, depend on their direct and ongoing interaction with green places. Devices are the enemy; videogames are mindlessly addictive wastes of time at best, and recruitment tools of corporate entities at worst.

I’ve climbed snowy mountains in Quebec and in Minecraft

Certainly, there’s good to be had in the outdoors: silence, a space for reflection, the feeling of dirt between your toes. I’ve taken kids on canoe trips and marvelled at how different they are after two or three days—life’s hectic enough as it is, and sometimes slowing down and appreciating what you have is all you need to re-energize. I wonder, though, what exactly “nature” entails, what “slowing down” means, what “disconnecting” can look like.

Right up there with my precious memories of watching a pill bug unfurl or starting a campfire with nothing but a match and some hope, are memories of seeing greenness and life return to Shinshu Field in Ōkami (2006), or finding hidden treasures in the underground jungle in Terraria (2011). I’ve spent hours paddling in canoes and hours sailing in the King of Red Lions in The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (2003). I’ve climbed snowy mountains in Quebec and in Minecraft (2011), with joy and urgency in both.

///

Z holds the Wii Remote gingerly, distracted by Navi, who appears on screen to denote where the controller is pointed. I’d forgotten about that; somehow, over the course of the hours I’d put into the game, I’d deleted her from my visual lexicon. To me, she was nothing more than a cursor. To Z, she was a character that was a part of her experience.

I’ve brought a copy saved just outside the fishing hole.

“Does it get cold up there in the winter?” Z asks.

“No, but Snowpeak is just to the north—look there, on the minimap.”

“What’s a minimap?”

“Well, it’s like—imagine if you were on an expedition, and the map was always in the lower right-hand corner of your field of vision…”

We discuss, as she orients herself, augmented reality and the virtues of north-up versus track-up maps.

After some time attempting to figure out how to control Link (“the elf boy”) she finally enters the door in front of her. Locating the A button takes work; her hands aren’t used to the geography of a two-part controller—it may as well be 2006 again, when I loaded up Wii Sports for the first time to work out the Wii’s many parts for myself. I sigh, softly; it’s spring in the fishing hole, a soft breeze carrying flower petals into the lake. My eye catches the heart piece I’d somehow missed in this playthrough, more interested in the graphics in the background, and all the trees she can’t climb.

///

In 2013, I had the opportunity to attend the first annual Canadian Student Outdoor Education Conference, a coming-together of rugged adventuresome folks, environmental activists, gym teachers and camp directors. Z suggested I attend to get a feel for what it would be like speaking at it in years to come.

Link could learn a thing or two from a professional about sterning a canoe

I discovered that nothing fires up a tired crowd quite like asking a room full of people in hiking boots what they think about gaming. I ended up in a long and thoughtful debate with a retired tactical helicopter pilot now working towards her M.Ed in education—specifically, studying how children develop spatial orientation and cognitive mapping—whose career spanned the introduction of real-time mapping technologies, such as GPS. She wondered if we were entering some kind of brave new world where people would learn to trust Google Maps more than their own knowledge and instinct to get from Point A to Point B, if there wasn’t some way we could teach kids to really learn how to navigate a space by memory.

I had that conversation in mind a year later when 90,000 people—furiously typing away in a Twitch stream now immortalized in iconography and mythology any anthropologist would be proud of—perfectly and simultaneously recalled how to get from Pallet Town to the final showdown at the end of the Indigo Plateau.

///

We paddle around in near-silence for a while. Z tries, unsuccessfully, to canoe up a waterfall. She’s incensed that if you jump out of the canoe you’re not allowed back in. She’s also discovered that she genuinely enjoys fishing and the motion of turning the nunchuck. I point out the heart piece and turn up the contrast on the TV screen so she can see the bottle hidden by the walkway. She feels that Link could learn a thing or two from a professional about sterning a canoe. (“Maybe Hana is letting him figure it out on his own,” she wonders. I wonder about fanfiction and character agency.) She asks if there’s any canoeing other than the fishing hole and I take her to Iza’s Rapid Ride, which is a little beyond her skill level. She tells me about swift-water kayaking as I navigate the river, and when I get to the bottom, she asks to see it again.

Later I call Epona in Hyrule Field so that Z can try sharpshooting on horseback. She’s interested in the human-wolf transformation and wonders about its relationship to several religious canons, and is genuinely delighted that Link can speak to Epona as a fellow animal. She notices things I hadn’t: the texture of the grass, the movement of Navi on screen, the way the wind pulls at Link’s hat. I teach her the difference between horse grass and hawk grass and show her where they grow. She gets excited about plant identification as a gameplay element and wonders if there’s a field guide to the game—I direct her to the plethora of wikis.

In the end we must have been in that room together for four hours, playing Twilight Princess like my brother and I played The Legend of Zelda (1987) when I was six: noticing things, missing things, trying and failing and trying again, pointing things out to each other, sharing information, testing items and skills to see if they work as intended. I had a better sense of where things were and how to defeat certain enemies, but for Z it was all about that moment of joy in trying something for the first time.

When I guide trips or run an outdoor education lesson I try to instil that same sense of curiosity and wonder in my students.

///

In his book, Louv talks a lot about “wonder,” that elusive sense of surprise and admiration at the new or unexpected. Wonder can lead to a sense of belonging, and community built around shared experiences of discovering how we fit in with those around us. He writes with concern about a generation being raised without that sense of connectedness, without the joys of play, the emotional extremes of loss and longing and delight. I wonder if he just isn’t considering all his options; maybe, despite all our big talk about being open-minded, outdoorsy people are cutting ourselves off from entire worlds of possibility.

An attendee at the outdoor education conference, furiously defending Louv against my blasphemy, suggests that videogames are the wrong kind of play because they’re “not real”. I ask her what ‘real’ is. She’s silent for a while. “Real is anything you can feel,” she offers. “Real is anything that makes you feel something.”

It’s common for people in my field to talk about “real” in this way, as though it’s a place you can go to: a mountain or a forest or a river. But, for four whole hours, “real”, for Z, was in Hyrule.

Images via Zelda Wikia

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers