Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 128

April 29, 2016

Run the world’s fastest tattoo parlor in Ten Second Tattoo

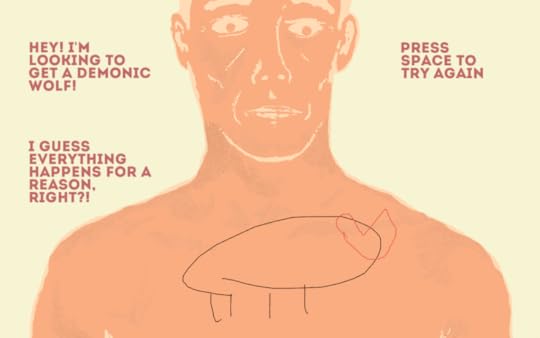

For a little while now, I’ve been contemplating whether or not I want to get a tattoo. It’s not that I have a particular idea for one in mind, so much as it is that I like the thought of using ink to assert my own bodily autonomy. I just have two issues stopping me from pulling the trigger. The first is that I can’t think of a design I want at the moment, let alone one I’ll like decades down the line. The second is that I worry about where I should go for such a permanent change. After playing Burgess Voshell’s Ten Second Tattoo, I can at least say: probably not here.

On the surface, Ten Second Tattoo has all the makings of a Jenny Jiao Hsia game. It’s got her same soft palette art style, the same font she uses in many of her own games, and its conceit is similar to Hsia’s Morning Makeup Madness, only instead of putting makeup on in a 10 second time limit, you’re applying something that can’t be wiped off—a tattoo. The title screen even has a disclaimer reading “A Game Not By Jenny Jiao Hsia.”

I’ll admit, the first time I saw screenshots of the game, I was fooled. Hsia herself had posted them, and I assumed they were part of a sequel to Morning Makeup Madness. In the shots, she had appropriated the game to do some rather “bold” permanent makeup, leading me to ask “Dear Lord, what are you working on now?” She laughed, and pointed me to Voshell as the actual person behind the project.

“It’s a bit of an ouroboros situation”

In an email, he explained to me that Ten Second Tattoo was part of an NYU Game Center assignment asking students to make a fan game of another student’s game. He chose Morning Makeup Madness, and here we are. “It’s a bit of an ouroboros situation,” he tells me.

As a fan game of a small browser title, Ten Second Tattoo occupies a space not seen often in games. After all, it’s usually only larger games that tend to see fan games based off of them, urged on by vibrant modding scenes and powerful user creation tools. By contrast, Ten Second Tattoo shows us what happens when creators riff off each other’s smaller works.

The result is a title that captures Hsia’s signature use of frustration as a mechanic while upping the consequence, and it is a hoot. Let me be blunt: I am not a good tattoo artist. Of the dozens of customers I’ve seen in Ten Second Tattoo so far, only one has ever had a positive reaction, and I think he might have been being sarcastic. The others keep asking for my manager or about our refund policy, and frankly, I’m surprised they’re being so polite after I’ve (almost) permanently destroyed their chest like a toddler scribbling on living room walls. In my defense, though, drawing a “murderous balloon” or a “poisonous moon” isn’t easy, let alone in 10 seconds. Be kind to me, Yelpers.

You can download Ten Second Tattoo for PC and Mac on Gamejolt.

New game reminds us you can’t take the ‘disco’ out of ‘discomfort’

You can’t spell ‘discomfort’ without ‘disco.’ Or at least, that’s quite literally the scenario spelled out in game maker Fedor Balashav’s brief experimental title DISCO / DISCOMFORT . In DISCO / DISCOMFORT, the player enters a neon-flushed disco club in the midst of seemingly nowhere, an environment that quickly devolves into a sociophobia-driven nightmare. You, the player, are tasked with interacting with other people, but if only it were that simple.

Not just looking at my faceless first-person character, they were looking at me

Sociophobia is, by its dictionary definition, the fear of socializing. That means, the fear of social gatherings. The fear of embarrassment in the presence of peers. In DISCO / DISCOMFORT’s case, the fear of dancing and drinking at a club. It’s social anxiety at its utmost crippling. You enter the club, initially greeted by the room’s technicolored, disco-thumping embrace, until you take a step forward. The music grows distorted. Then another step forward. Some people turn around. Then everyone’s watching. The dancing stops. Everyone’s eyes are locked on you.

For the ‘full experience,’ Balashav notes that players should have an operational webcam. I had my webcam turned on, and while I wasn’t sure of its precise function, I did feel an uncanny eye-to-eye ratio when I passed by the ever-staring 3D people on the screen. They weren’t just looking at my faceless first-person character, they were looking at me. The real-life eye contact adds an extra level of dread to the experience.

As someone who suffers from social anxiety, and has even written about it from time to time, I found DISCO / DISCOMFORT to be realistically distressing—but that’s the point. Social anxiety isn’t cozy. It doesn’t turn off when you want it to. You work through it, even if it haunts you along the way. Whether it’s to get that “Special Introversion Award” trophy at the end of the disco club, or to do something else entirely.

You too can attempt to avoid other virtual humans at all costs by downloading DISCO / DISCOMFORT on itch.io for Mac or PC.

Nostation, a game inspired by late-night train rides across China

In China, years ago, Bubble is riding a train late at night. “In the [past] the train was slow and dirty, it [would] take a long time to arrive at the destination,” they say. Bubble is far away from home and the train is almost entirely empty. “Just me alone,” Bubble tells me while recalling the memory. “Probably at 2 a.m. I opened the window and looked out, it [was] a fantastic feeling.” Bubble can’t describe the feeling further than that, other than saying it wasn’t loneliness, and it wasn’t fear, it was something else.

The experience left a deep impression on Bubble. In fact, that quiet and desolate train ride is the inspiration behind Nostation, an upcoming game about riding a train—possibly forever. Those mysterious and long hours on a lonesome train is what Nostation is being made to capture. And so, in the game, you board a train with five other passengers. Your destination is unknown to you and the others on the train. As the game goes on the train will stop four times. You may or may not be permitted to get off any one of these stops. Regardless, whoever is left when the train leaves that final station will remain on it forever.

“I want to let the world see China [can make] great games.”

“This will be an unpredictable trip,” Bubble explains. The train and the destinations are procedurally generated with each playthrough in an effort to create what Bubble describes as a “story game with some rogue-like elements.” It’s expected that you’ll play the game over at least a few times to explore the different story branches and endings. It might even take a few playthroughs before you can actually escape the train. When I ask Bubble if it’s possible to escape on the first try, they respond cryptically: “Ah-ha, it’s a secret! I can’t tell you anything.”

Bubble is the nickname of the founder and lead designer at Chinese studio Bubble Games Paradise. The studio was formed in 2015 and is spread out across the country. The employees of Bubble Games Paradise coordinate via the internet. Developing a game this way can be tough, but Bubble explains that Bubble Games Paradise is made up of longtime friends. “We are very successful at communicating and understanding, and they are very trust[ing of] me.”

Making a game using the web can be tricky enough, but doing it in China makes it even more difficult. Bubble describes making games in China as “Just like Hell.” The market in China is focused on making money, usually with free-to-play games. Bubble isn’t looking to make that type of game. They want to focus on the story and art of games, something they say is hard to do in China. Many of the studios and publishers are looking for profits over story. But Bubble and the people at Bubble Games Paradise are determined to finish Nostation and to make more games after that. “We will not stop making games,” Bubble says. “[This] is my dream. Games [have no] borders, I want to let the world see China [can make] great games.”

Nostation is currently on Steam Greenlight. You can also check out the game’s website.

Videogames and the digital baroque

During the 17th century in Europe and her colonies, mankind was forcibly removed from the center of the universe and cast adrift in an indifferent cosmos devoid of greater purpose or meaning. This was accomplished not by any supernatural power but by advancements in technology, particularly optics: telescopes could chart the motions of previously obscure celestial bodies while microscopes could, for the first time, see the living cells that made up human bodies. Earth turned out not to be the center of the universe but one of many planets that orbited the Sun; an average star among countless others in the heavens. The human body was not a complete and sacred image of God, but a fragmented mess of cells, each growing, splitting, and dying autonomously. Literary critic William Egginton, in his book The Theater of Truth (2009), wrote that “the relation of appearances to the world they ostensibly represent” was a central problem of baroque thought, a problem that had no easy solutions and, thus, was pondered by generations of artists and writers through the works they produced.

The arts—painting, sculpture, architecture, theater, and poetry—flourished not in spite of these problems and upheavals but perhaps because of it. The baroque era, which lasted roughly from the late 16th century to the middle of the 18th, played host to new varieties of artistic expression that, in their melancholic mourning, pilfered fragments from ruined or imagined pasts and rearranged them—like a puzzle without a solution—into a nearly endless variety of novel forms and iterations. This process continues to this day, as a growing number of theorists draw parallels between the disorienting effects of digital technology in the 20th and 21st centuries and the societal upheavals of the 17th. A digital baroque era has been inaugurated, expressing potential solutions to the same problems of thought through the media we produce and consume.

The human body was not a complete and sacred image of God but a fragmented mess of cells

The relationship between image and reality has been brought into question once again due to the destabilizing effects of digital technology. Richard Sherwin wrote about this tenuous relationship in his book, Visualizing Law in the Age of the Digital Baroque (2011): “In a time when we can digitally picture just about anything we can imagine it should not prove surprising that doubts may arise concerning the truth of what we see. This feeling of doubt, which culminates in a loss of confidence in the faculty of representation itself, lies at the core of baroque culture—both the baroque culture of 17th century Europe, and the global digital baroque culture that we are living in today.” The baroque presents the threatening notion that, if there is an absolute reality beyond the veils of appearances, we have no means with which to access it. The mediation of digital technology—a gatekeeper stationed between an assumed reality and the images we see of it—has brought this anxiety to the fore once again, now fittingly expressed through digital media. Final Fantasy VI, a role-playing game released for Japan’s Super Famicom in 1994 and localized as Final Fantasy III later that year on the Super Nintendo in America, is an artifact of this anxiety, a virtuoso performance that uses visual, audio, and narrative techniques of the historical baroque while pushing the game technology of the early 1990s to its limits. From Software’s Souls series, consisting of Demon’s Souls (2009) and Dark Souls I, II, and III (2011, 2014, and 2016), popularly known for their infamous difficulty, presents a neo-baroque vision that stands as a counterpoint to that of Final Fantasy VI: the worlds presented in the Souls games lack most surface trappings of the baroque but, on the levels of narrative and interactivity, are conceptually indebted to the problems of thought that influenced artists of the baroque and digital eras alike.

In 1928, Walter Benjamin published his first (and, during his lifetime, his only) book, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, examining a little known—and even less appreciated—genre of German theater: the baroque Trauerspiel, or tragedy play. Towards the end of the text Benjamin, writing about the use of allegory in the genre, sets up an allegory of his own: “In the ruin history has physically merged into the setting. And in this guise history does not assume the form of the process of eternal life so much as that of irresistible decay. […] Allegories are, in the realm of thoughts, what ruins are in the realm of things. This explains the baroque cult of the ruin.” To Benjamin, the artists and writers of the baroque rarely, if ever, invented anything: they instead took pieces from antiquity and stuck them together to form new combinations of existing elements. The ruin and its fragments constituted “the finest material in baroque creation,” and the era’s artists and writers collected these fragments with the hope that new works would coalesce from these piles of cultural detritus. Benjamin’s ruins are not the literal remains of ancient civilizations, but textual, visual, and narrative fragments scattered throughout the field of history. The “baroque cult of the ruin” is related to the baroque problem of thought—the gap between image and reality—through the assembly of new fictional realities from these leftover bits of past images. This is heightened in the digital age, as processes of digitalization involve multiple levels of fragmentation down to the individual zeroes and ones of binary code. The worlds presented in Final Fantasy VI and Dark Souls could be seen as fractured from the start, existing as ruins of bits and bytes burned to ROM chips or pressed on DVDs. At another level, both games use the ruin as a form of narrative structure, allowing the player to put together a broken story piece by piece, fragment on top of fragment.

Final Fantasy VI is a game divided in two: the first half builds up a world and story characteristic of a mid-90s role-playing game, with the player assembling a ragtag band of rebels to fight against an evil empire. In the second half of Final Fantasy VI the ruin becomes the main form of both the in-game world and the narrative. The player’s party of characters has been broken up and strewn around the world. The world map itself has been violently rearranged, with continents shattered to bits and smashed together to form new land masses. At the same time as the world is broken apart, the game’s narrative is fragmented as well. The previous half of the game had a chiefly linear storyline progression: one event followed another, and the game’s events kept the player on a narrow, singular path. This narrative path, along with the world, is destroyed in an apocalypse which the player was powerless to prevent. After an escape from a deserted island, the player is given free reign over this new world, left to wander with the ultimate goal of reuniting the scattered party of characters and defeating Kefka, the self-proclaimed god of magic whose lust for power shattered the world in the first place. Interestingly, this goal does not involve restoring the world to a singular, cohesive whole. The characters seem to recognize the impossibility of returning the ruin to its former state of completion. Their goal, instead, is a practical one: prevent further destruction by killing the false god and “demystifying” the world. The characters have to be content to inhabit, rather than save, their broken world.

From Software’s Souls series takes an opposite approach from that of Final Fantasy VI: rather than ruining the world and the narrative before the player’s eyes, the game takes this fallen state as its genesis and allows the player to build the world and story as if wandering through a vast field of scattered fragments. Dark Souls begins by throwing the player into a world of dying flames, offering minimal explanation or exposition beyond the basic controls, written in glowing orange “messages” on the ground. These messages, whether left by the game’s developers or by other players, are a few of the many fragments the game invites the player to piece together. Every item the player can pick up has a bit of narrative associated with it. Some of this “flavor text” is straightforward, telling the player how to use the item, but much of it offers insights into the game’s story that cannot be found anywhere else: all of these fragments add to a larger story that, to the delight of some and the frustration of others, may not actually exist.

artists of the baroque took pieces from antiquity and stuck them together to form new combinations

A technique that was widespread in historical baroque artworks was anamorphosis, the intentional distortion of a pictorial element that calls for the viewer’s direct involvement to “complete” the image. A canonical example would be The Ambassadors (1533), a pre-baroque painting by Hans Holbein the Younger that featured a strange gray smear in the foreground between the painting’s two figures. If the viewer stands at a particular angle, however, the smear resolves itself into the shape of a skull, a reminder of the omnipresence of death amidst worldly wealth and power. Anamorphic technique is not limited to simple distortion, however: an anamorphic technique that Gregg Lambert, in On the (new) Baroque (2008), calls the “central absence” involves the subtraction or non-inclusion of an element central to a work’s composition. Lambert cites Caravaggio’s painting The Conversion of Saint Paul (1600) as a prime example, as it depicts the titular saint’s conversion on the road to Damascus yet does so in a completely naturalistic manner, leaving images of angels or apparitions out of the picture in favor of the swirling shadows of baroque chiaroscuro. The focus of the painting—Paul’s spiritual change—is shown in a more powerful manner by not being shown directly.

Both Final Fantasy VI and Dark Souls have central elements that are inaccessible or non-existent. In Dark Souls, the storyline is made visible to the player almost exclusively through the narrative fragments provided by items, characters, or other players. The game’s story does not exist in any singular form outside of the player’s interaction. The player is encouraged to create a story out of these fragments, but that story becomes about that particular player and her interaction with her world, rather than a “grand narrative” of the game’s world in general. An earlier work that used a similar method of narrative and world building was SquareSoft’s SaGa Frontier (1997), a role-playing game that, rather than featuring a single story, allowed the player to play through seven loosely interconnected storylines in any desired order. Each of the game’s seven main characters had a storyline that revolved around him/her/it: the cast included a magician training to fulfil his destiny by killing his twin brother, a girl whose life had been saved by a blood transfusion from a vampire-like “mystic” lord, and an ancient robot who sets out to rediscover and complete a lost mission. Each of these storylines could stand on its own, but all of them are tenuously connected to each other, having worlds, areas, characters, enemies, and some sub-plot elements in common. They don’t present different sides of a larger story, as there is no larger story to represent. SaGa Frontier could be seen as a “polycentric narrative,” as it contains multiple stories yet has no single element acting as its “center.” At the narrative center of SaGa Frontier is a void, like that of Dark Souls, an empty space for the player to fill using the raw material given to her by the game.

The Conversion of Saint Paul (or Conversion of Saul), Caravaggio, 1600

The Conversion of Saint Paul (or Conversion of Saul), Caravaggio, 1600

In Final Fantasy VI, the player could be seen as the absent central element, as there is no way to directly control the characters on screen: the player is a director, issuing commands to them from outside of the game’s diegetic space. While player interaction in Dark Souls is centered around the player’s avatar, and thus the player’s presence in the game’s world by proxy, Final Fantasy VI has no means through which the player can interface with the world directly. In a battle situation in Dark Souls, the player’s button presses have a predictable and particular correspondence to the avatar’s on-screen and in-world actions: pressing the “attack” button allows the avatar to strike with an equipped weapon, while the “dodge” button immediately executes a dodging somersault. In Final Fantasy VI, by contrast, the player’s interaction with the game’s cast of characters is mediated by systems of menus. To attack an enemy in battle, the player selects the “Fight” command. The character on-screen switches to a battle stance, waits for her turn in combat, and, depending on calculations made by the game’s battle system, may or may not execute the attack as commanded. If the character gets hit by an enemy’s attack before her turn comes up, she could be knocked out, confused, paralyzed, or otherwise made to attack ineffectively, if at all. The game’s battle system mediates between the player’s commands from outside the game and the actions taken by the characters on the screen. The use of this particular system may have been due to the limitations of 16-bit gaming technology that made Dark Souls-style real-time combat impossible, or an artifact of the accumulated tropes of role-playing games that made the use of turn-based combat a relatively unquestioned default within the genre, but nonetheless the use of this system in Final Fantasy VI and similar games had powerful effects on the player’s relation to the game world and its inhabitants. The distance maintained between the player and the characters works to prevent the player from having an avatar-like identification with a particular party member. A player may have a favorite character, but none of them are empty vessels to be filled with the player’s subjectivity as the player avatar in Dark Souls can be.

Instead of being avatars, the characters in Final Fantasy VI are just that: characters, in a theatrical sense. Like SaGa Frontier, there is no single “main” character in Final Fantasy VI: the game features an ensemble cast that has no central protagonist. The narrative may occasionally focus on a particular character—such as the opening scenes, in which Terra and her magical talents are sought by both the Empire and the rebels—but the game’s overall story doesn’t follow a single individual. The game presents a cast of characters on a digital stage, allowing the player to direct (but not control) their actions from beyond the “fourth wall.” This theatricality—the division of the world into an audience and a stage—is perhaps the most direct expression of the baroque’s problem of thought. Egginton wrote, “From the moment of its inception in the late sixteenth century, the modern European theater, that institution coterminous with the division of the world into an audience and a stage, has been driven by the same troubled relation that has prodded its historical fellow traveler, modern philosophy: the relation between truth and illusion.” If this analogy holds, and the player’s role in this role-playing game is that of a director, who is the audience of the performance on the screen?

the player is both the director of the on-screen play and as its intended audience

In the theatrical space of Final Fantasy VI, and much interactive media in general, the baroque problem of thought is made more complex because the player stands on both sides of the theatrical division of space, acting as both the director of the on-screen play and as its intended audience. Multiplayer games, such as Dark Souls, complicate this division further: each player performs not only for herself but for everyone connected to her. The multiplayer system used—with minor modifications between entries—in the Souls series envisions a multiplicity of worlds, each inhabited by a single player, through which other players from other worlds phase in and out of it as “phantoms,” illusions as opposed to the “reality” of the embodied player. Some phantoms are harmless apparitions; others are summoned by the player to engage in cooperation, while some invade the world maliciously to kill and wreak havoc. All of these worlds exist parallel to one another, a setup illustrated diegetically in Dark Souls: the game world is supported by a massive “world tree,” and if the player finds the hidden area of Ash Lake at the base of its trunk, other world trees—supporting other worlds—can be seen sprouting from an endless primordial sea. Each player is the sole inhabitant of her own world, as all interaction with other worlds and other players must be mediated through phantoms, and each of these phantoms acts as performer and audience to each other and themselves.

The question of who performs and who spectates becomes even more complicated when interactive streaming technologies are brought into the equation. Online platforms such as Twitch allow players to broadcast their play to any number of viewers worldwide, who, through a text-chat interface, provide real-time feedback that can influence the player’s actions. The digital baroque could thus be seen as breaking down the theatrical division of space that had so closely defined its historical predecessor. Emerging virtual reality technologies open up new possibilities for illusionism and spectacle that could further destabilize the already tenuous boundary between images and reality. The anxieties associated with the loss of connection to an ever-receding truth are likely to stay and deepen as the digital baroque proliferates and iterates, its fragments recombining into new cultural forms that subsume and consume that which came before to create things never before seen.

Featured image via Li Taipo

April 28, 2016

An art book wants you to embrace your failures

To be an artist is to know failure. We know it intimately, in our smudges and our typos. We fear it, anxiously hesitating before we draw the second eye, afraid that we cannot replicate the perfection of the first. Failed It! by Erik Kessels challenges these feelings, arguing for the beauty of our mistakes. It’s part photobook, showcasing many beautiful and hilarious examples of imperfection across different creative mediums. But it’s also part guidebook, seeking to dispel our fear of mistakes and, in doing so, remove an obstacle to reaching our full potential as artists.

While some of the photographs in Failed It! may only give you pause to chuckle, many others show precisely why we shouldn’t be afraid of mistakes in our work. It is often the unintended strokes that make things interesting after all. In the words of the immortal Bob Ross: “There are no mistakes, only happy accidents.” To Kessels, a thumb obscuring the lens doesn’t ruin the photograph—it just makes the photograph about something else. Failures become transformative.

there is something precious in the imperfect

In a world where we have the ability to perfect everything, there is something precious in the imperfect. When we can Ctrl+Z away a slip of the hand on our computers, there’s something daring about pencils and nibs and brushes. Kessels asks us not only to be unafraid of failure but to view it as an element of what makes our art worth caring about at all. If art imitates life, perhaps it should be imperfect, just like the humans who make it.

Failed It! is out now and can be purchased here.

Header Image: Mistake by Bradley Higginson

Internet Murder Revenge Fantasy is a first-hand look at growing up online

As a transgender girl growing up in the American Midwest, childhood was a lonely experience for me. I was still questioning so much of who I was, and at the time, there weren’t many resources out there to help me work through it. Transfeminist literature like Julia Serano’s Whipping Girl (2007) had yet to be published, and I had to resort to older and more colloquial narratives instead, like a 1998 book a mother wrote about her daughter’s transition titled Mom, I Need to Be a Girl.

Finding myself in a real-world culture that was unwilling to talk about LGBT issues for fear that they were somehow inherently “too adult” for me, I instead turned to the internet in my bid to put words to the feelings inside. Finally, on a few backwater websites with conflicting information and often unreadable fonts, I got my first glimpse of the trans community. It was scattershot and reflected an era when the term “transsexual” was more popular than “transgender,” but its Geocities and Xanga stylings were the first to tell me “You are not alone.”

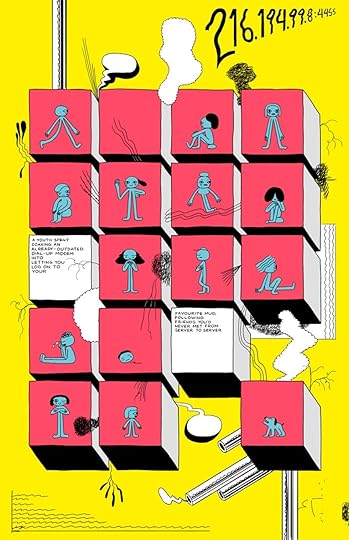

In her comic Internet Murder Revenge Fantasy, transgender artist and game designer Merritt Kopas describes her own experience of finding herself online, going all-in on a childhood not formed on football fields or even in 7-11 parking lots, but rather through obscure internet forums, blue-haired anime pretty boys, and French ROMS of Japanese fighting games.

The comic, a collection of seven poems illustrated by 28 different artists, opens with a diverse group of blue stick people each living within their own individual red box, which are then connected together by a series of tubes. Their personalities vary from welcoming to decapitated, and it’s an apt representation of the kinds of online environments where many of us spent our formative years. What follows is a coming-of-age story about stumbling upon the forbidden corners of the internet and for the first time being exposed to a culture outside of the real-world that is so often unhelpful to the queer and questioning.

Like Sailor Moon transforming into new outfits, Kopas tries on new identities based on the internet culture around her, making them her own with each morphing sequence. Throughout the course of the comic, she is a shoujo heroine, a half-beaten Saiyan warrior (who kind of likes it), an anthropomorphic dog person, a forum user with a perverse taste for the report button, and a blue-haired anime girl role-playing her way to submissive fantasies she didn’t know she had. For someone desperate to be anyone other than what their culture has assigned to them, the internet is a powerful tool.

a coming-of-age story about stumbling upon the forbidden corners of the internet

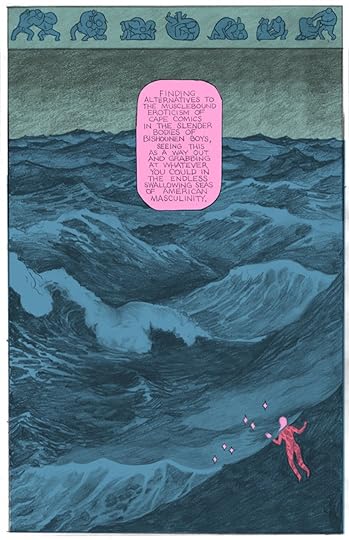

That said, few of the sites Kopas visits are directly related to being trans. Overtly trans themes are peppered throughout the comic, but its most prevalent aesthetic is one of anime. There’s a splash page with an original fan-character pulled from the collective sophomore study halls of a million weebs, a pencil-drawn sketch of a blushing fox boy in a kimono, and always a helping hand from anime poster-boy Goku when times get rough. In “A Bishie Saved My Life,” Kopas dives deep into how the soft-featured, long-haired, androgynous men of anime gave her an avenue to explore her own burgeoning femininity.

“Finding alternatives to the musclebound eroticism of cape comics in the slender bodies of bishounen boys,” she writes. “Seeing this as a way out and grabbing whatever you could in the endless swallowing seas of American masculinity.” Here, Kopas fires back at a culture that often likes to ignore its own sexual subtext with raw sexuality of her own, refined through fansubs and manga scans adopted from a series of islands an ocean away. At the same time, she is an outsider looking in, playing into classic orientalist themes by exoticizing small and unrepresentative scraps of Japan’s culture, and she recognizes this. At a certain point, she had to go back home.

The comic ends with a riff on Blade Runner’s (1982) famous death scene as Kopas recounts her visits to the congealed cumrag of id that is 4Chan. She talks about coming across other trans girls posting nude selfies for the boys to fap over. She wants to embrace them, worried that they have “moulded themselves into subhuman sex dolls,” knowing that it was because “it felt like the only route to intelligibility.” She wants to save them from a community that’ll praise them as sexual objects but refuse them basic dignity as human beings. She’s no longer some scared kid making the text smaller to hide it from dad. She’s an internet senior ready to take the new batch of froshes on tour.

With its many open browser windows and instant messenger clients, reading Kopas’s comic is reminiscent of diving through Nina Freeman’s desktop in Cibele (2015). But if Cibele is a drama about failed romance, then Internet Murder Revenge Fantasy is straight pornography. It’s vibrant, it’s taboo, it’s brazenly erotic, and it’s an open-book look at some of the lesser-discussed “pastimes” that we all had as teenagers (wink wink). For queer audiences, it holds special value as a representation of where many of us first found ourselves—I’ve even put it on my OkCupid profile alongside an “it me”—but it also points to the more general internet Wild West of the ’90s and early ’00s.

As an adult living 16 years into the new millenium, I now spend most of my browsing time on clean, contemporary, “safe” sites like Facebook and Twitter. But as a kid? I frequently sneaked into my family’s computer room at 3:00 a.m. to stream illegal fansubs of terrible body-switching anime from sites that had a 50/50 chance of giving me a virus. My family would have been mortified if they knew, but there’s something to be said about letting the shield down and allowing kids to tread out into dangerous waters now and then. It was there that I learned to swim.

You can buy Internet Murder Revenge Fantasy on Kopas’ itch.io. All proceeds go to her surgery fund.

The threat music and animal sounds of Rain World

The goofy term “slugcat” has been tossed around to describe the creature you’ll control in Videocult’s upcoming game Rain World for a couple of years now. Due to its unique ecosystem set on an industrial planet that’s ravaged by bone-crushing downpours for most of the year (the game takes place during the brief dry season), describing the things that flap, squirm, and leap around Rain World is a task. Imagine, then, trying to apply not words but audio to match everything found on this alien planet. Well, you don’t need to, as a recent Kickstarter update (the game was successfully funded back in January 2014) sees creator James Primate detail the dynamic audio design for this grimy-aestheticized platformer.

“At this point Rain World has around 1400 screens of playable terrain covering 12 huge regions,” writes Primate in the update. “So naturally the music has to be equally gigantic in scope to match.” Together with musician Lydia Primal, Primate has had 3.5 hours of music composed for the game. Yet, surprisingly, music in Rain World is not a constant.

The game is quiet when it needs to be

In a detailed video explanation, Primate explains the dynamics of the audio in Rain World. For the most part, the game is littered with ambient sounds, such as the wind blowing, the rustling of slugcat and other critters, to drips of unknown fluids in the area. The game is quiet when it needs to be. Yet, in some cases, the game needs some melody to cultivate a mood, and that’s where Primal and Primate’s compositions come in. Depending on the particular environment or event, the somber music chimes in, and plays out to the extent of the event (or the length of the area).

In a more dynamic path, Primate and co. have implemented a unique “threat music system.” With this, the melodies shift depending on how much danger slugcat is in. Each level has 10 “or so” variations of audio, depending on the perceived danger of a nearby enemy. If slugcat successfully evades the hazardous lizard-y creature and slugcat’s danger decreases, as does the threat of the music. It’s a clever cue to inhibit the player’s perceived danger level, in addition to the environmental sounds, such as the loud thud of a lizard following slugcat into a new area and attempting to seek it out displayed in the video update.

Dynamic audio is only a small sliver of what’s been detailed for Rain World in its past updates, with consistently beautiful GIFs showcasing the smooth movement in the game, and smartly designed enemy encounters. At the very least, we’re looking forward to all the eerie environments, panicked lizard-escaping, garbage worm-inhabiting adventures that slugcat’s world has to offer.

Rain World remains in active development with hopes of releasing sometime in 2016. You can follow its Kickstarter for more updates and slugcat-filled GIFs.

The MADE, or the importance of games console history you can touch

About 30 miles northeast of the Frank Gehry-designed campuses and complexes where competing cloud environments are designed, there’s an Oakland museum full of game cartridges. You can see the sign from the highway: The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE).

That the sign is visible from the highway is a big reason for an uptick in attendance since the museum’s February 2016 re-opening, I’m told, and this seems right to me. In the San Francisco Bay, where programming cultures abound and history is cast as something to be disrupted, forgotten, discarded, the MADE idiosyncratically contrasts the irresistible narratives playing out in the marketing and team scrums of nearby Silicon Valley.

I caught up with Anders Sajbel, the creative director for the MADE, who took me through the museum’s history, its future, and how the context of a museum might change the way these games are perceived and interpreted.

The MADE is a non-profit dedicated to the preservation of videogame history, and to educating the public as to how videogames are made. Its space is divided largely in two: the first, a display floor, arranges game consoles and cartridges in a roughly linear order by era. Most of the games and consoles were received by donation, the majority of those from the now-defunct GamePro magazine’s offices.

The second space is formed by a cluster of classrooms, in which seminars and workshops cover such topics as ‘Scratch Programming for Kids,’ the finer points of character design, and how to make your own GIF. When I visited the space, Anders was preparing it for a talk later that evening by a panel of sound designers whose game audio has appeared in the Ratchet & Clank and Oddworld series’.

there’s something to learn from the faded boxes and failed peripherals

The tacit interdependency of these two spaces is important to make explicit: by co-locating a space for game history with a space for learning how to make games, the MADE enables a dialogue about what’s come before and what’s coming next. This is where the context of a museum adds value, and elevates the concept of the MADE above festishism or nostalgia. In a city where ‘what’s next’ is valued in billions, the MADE presumes that there’s something to learn from the faded boxes and failed peripherals of yesteryear.

I recently moved to San Francisco, and moving all my stuff was surprisingly easy, because people don’t really have stuff anymore. All of my carefully curated collections of books and records live in the cloud now. If not for a duffel bag of wrinkled t-shirts, I’d have arrived empty handed. So you could say I was skeptical that the value attached to little grey cartridges might outweigh the incredible convenience of lightness.

And then I saw a faded Super Nintendo Superscope box and, like Anton Ego eating ratatouille and being transported in his mind’s eye back to his childhood home, I was on maroon-colored carpeting in my parents’ basement, whiling away summer hours. A Power Glove presumed to sit in a glass case. Curiosities, like Philips CD-i’s with Nintendo-licensed characters, speak to oddball arrangements and one-offs in the history of the console wars. Stacks of old gaming magazines; the grey Game Boy display case from which one can sample bi-chromatic Tetris (1989); a cardboard standup of infamous Atari flameout E.T. (1982).

What struck me immediately was the power of the packaging. The MADE is a 1980 aesthete’s opium den.

What seems, when on store shelves, to be junky old marketing—crass, obnoxious, and silly—takes on a retrospective resonance. In that, the MADE serves to not only preserve and re-frame an aesthetic that existed between the late 1970s and late 1990s, but drives one to consider the design of the marketing encountered everyday.

The MADE seems to tap into the tactility of these consoles

What will retrospection do to, say, the celebrity-laden mobile game commercials that have currency today? Or, put more bluntly, turn an Odyssey 3000 box into a t-shirt and I might never take it off. In any other context, one might simply conclude that the MADE is possible because of an extremely lucrative nostalgia market that pumps out Transformers movies for young men who grew up on Transformers, and who today have jobs, but don’t yet have kids, and so have money to spend.

But then again, there are those nagging concepts of community—the beckoning classrooms, asking the visitor to not only experience videogame history, but then to apply it. There are the kids being taught programming, and the partnerships with local schools via youth education programs, providing job experience in exchange of volunteer hours. The MADE seems to tap into the tactility of these consoles to reinforce the value of physical community.

Like everybody in the Bay, the MADE is struggling with outrageous housing prices driven by the influx of the tech industry. Finding an open warehousing space to hold shelves of game consoles and cartridges is particularly challenging. One never knows if, when the lease is up, one will be forced out so that a building can be rented for twice the price, or sold off to developers.

But for now, the MADE is hoping to keep expanding. Anders is planning to expand the collection to include recently discontinued consoles, like the Xbox 360, and a themed exhibit dedicated to former Nintendo CEO Satoru Iwata. And the demand for spots in MADE classes continues to grow.

For those of us for who the Bay remains a dream space of abstracted values, future promises, and very real inequalities, the MADE is a grounding experience. Walking in this cemetery of former giants has a way of doing that.

Visit www.themade.org for more information about the museum and a schedule of upcoming events.

A game idea hidden right in front of you

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

windowframe (PC)

BY DANIEL LINSSEN

You’re reading this inside a window. Practically every interaction with a piece of software takes place inside one. This has been the norm for computer use since around 1990, which is when Microsoft’s Windows 3.0 arrived and engulfed all other graphical interfaces. It’s reasonable to say, then, that having us reconsider the windows we peer into our computer files and the internet with every day isn’t an easy task. But, in only 48 hours, game designer Daniel Linssen has managed exactly that. In his Ludum Dare 35 entry, windowframe, you are tasked with killing six vampires, carrying a stake for each. This lethal use of the stakes is, however, secondary to their ability to pin the sides of the game’s window. To explain: Without throwing a stake into the sides of the square the game is contained in, the tiny window follows the character across the screen. Playing like this makes some puzzles impossible. To progress, you’ll occasionally need to keep the sides of the window in place and use them as a surface to walk and jump on. It’s a game about resizing windows. And a clever one at that.

Perfect for: Vampire killers, puzzle game addicts, software developers

Playtime: 20 minutes

Pixel art exploration game gets its moral ambiguity from Studio Ghibli films

Mable & the Wood is a 2D exploration game about a young red-haired girl with the ability to transform into other creatures. The idea is to get her through the titular colorful woods. However, the more you use the girl’s powers, the more you take from the forest, slowly destroying it—regardless, it’s the only way to reach some areas, and it’s the only way to beat the enemies you meet.

The idea behind the game was born in April 2015, as it was made for the Ludum Dare game jam that month, which carried the theme “An Unconventional Weapon,” hence the shape-shifting. Now the team has expanded upon the idea and taken it to Kickstarter, where it’s currently going through its final hours it’s already reached its funding goal.

“I don’t want to tell them that they’re the hero or the villain”

There’s an element to Mable & the Wood that definitely calls to mind fairy-tales and children’s folklore, but it’s the Hayao Miyazaki variety of moral ambiguity seen in many of his Studio Ghibli animated films that is the strongest influence. And this is intentional according to its creator Andrew Stewart. The game was inspired by the woods of the English Peak District near where Stewart grew up, but also on the works of the Japanese filmmaker, specifically Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984).

Miyazaki’s films have often portrayed a more nuanced portrait of morality than traditional children’s media. He has stated “the concept of portraying evil and then destroying it—I know this is considered mainstream, but I think it is rotten. The idea that whenever something evil happens someone particular can be blamed and punished for it, in life and in politics, is hopeless.” Characters in Miyazaki films are rarely portrayed as “Disney-villain-evil,” and this level of ambiguity is what Stewart hopes to attain.

“In a lot of magical stories, and particularly in videogames, there’s this strict conflict between good and evil,” Stewart says. “There’s good magic and then there’s black magic. That’s something I wanted to avoid in Mable—there’s just magic, and it can be used in a variety of different ways… so it’s down to the player to decide what their role has been in the story when they get to the end of it. I don’t want to tell them that they’re the hero or the villain.”

You can back Mable & the Wood on Kickstarter or play the demo on itch.io. The game has already been Greenlit for a Steam release.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers