Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 125

May 5, 2016

Paint Bug fills you with childlike joy as you create digital art

Even with the advent of adult coloring, it’s difficult to find an outlet that makes you feel like you’re creating unique art without actually having the talent to do so. Paint Bug, made in 72 hours for the Ludum Dare game jam, attempts to do just that.

Paint Bug gives the player control over a series of sticker-like characters that they can draw across a canvas. Each sticker, from the water droplet to the moon, has a different effect on the canvas. Players then have the opportunity to save their works as the final piece or as a timelapse series that shows all of the frames of the creation.

Paloma Dawkins, one of the artists involved with the game, said that the team originally wanted to create a kids game but that “our friend Henk had been doing work with brushes so we kinda veered into a drawing app.” What they ended up with was something between the childlike joy of Kid Pix (1989) and the procedurally generated art of Strangethink’s Joy Exhibition and Michael Brough and Andi McClure’s BECOME A GREAT ARTIST IN JUST 10 SECONDS (2013).

“You can jump in and just start making art”

One of the greatest strengths in Paint Bug is that the game just lets you create cool art immediately. “We wanted to let you quickly make something unique. I think that’s what works best. You can jump in and just start making art, and then when you’ve created something you like you can save it and share with your friends,” Dawkins writes. With a variety of tools that warp, distort and color the canvas it’s hard not to create something that is visually engaging.

More additions are incoming to the application, including more brush creatures and having the background have a greater effect on the brushes that are available. If you’re interested in playing around with Paint Bug, you can download it off of the game’s itch.io page.

Photography project kidnaps New York’s strangest architecture

You shake some cereal into a bowl and pick up a box of milk. As you’re about to pour, you see a sign on its side: Have you seen this building? Well, not exactly.

Some mischief has been done here. At least it’s mischief of the architectural instead of criminal variety. (Granted, this line is occasionally blurred.) The artist Anton Repponen and writer Jon Earle have imagined what would happen if 11 New York City icons were uprooted and placed in foreign, desert-like landscapes. They have, in a sense, been kidnapped, though that backstory is not wholly necessary when examining Repponen and Earle’s project “Misplaced New York.”

Marcel Breuer’s Whitney (now the Met Breuer) was always something of a fortress. The inverted ziggurat, with only one window on its façade and a series of portholes-cum-bay windows on its side, sits heavily on Madison Avenue. It looks even heavier dropped in whatever desert Repponen has chosen for it—heavier, but oddly at home. It’s the kind of building that, while suited to its original site, can impose its will. “I honestly don’t remember how we got the concrete on site,” Earle jokes. “Mules?”

Even the strangest of architecture is of a time and place

The Whitney’s new home, an industrial assemblage the architect and critic Joseph Giovannini described as “a catalyst sustaining and precipitating urban activity,” is not so easily transposed. Sitting atop a brush-covered mountain, its shapes feel somewhat incongruous. Whereas Breuer’s Whitney forced itself onto its site, this new museum designed by Renzo Piano absorbs urban forms like a sin-eater. In the absence of its neighbours, the building is deprived of energy. Its fictional kidnappers have not been kind.

“Misplaced New York” ought not, however, be judged solely on the basis of whether these icons work in their new environments. Indeed, the artwork functions as a commentary on architecture precisely because it reveals the importance of context. Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiraling Guggenheim building may look like a UFO dropped from outer space at the best of times, but it looks far more alien when moved from its actual site. Even the strangest of architecture is of a time and place. “Misplaced New York,” through its amusing scale and locale manipulation, makes this reality all the more apparent. In that respect, it is more of a love letter to New York than a demand for ransom.

See the entire “Misplaced New York” project on its website.

Traditional artists try virtual reality art for the first time

We all know that art can exist in virtual reality, from games like Adr1ft, to films such as Collisions. Virtual reality has shown itself to be a unique medium for immersing audiences in a work of art. But what about creating art within virtual reality? Google’s Virtual Art Sessions set out to experiment with exactly that.

Google invited six artists who all work with different mediums and material, to test out Google’s new Tilt Brush software. Tilt Brush functions as a palette and a brush that simulates painting in a 3D environment. Jeff Nusz, one of the people on the Data Arts Team at Google, commented in the behind the scenes video that it was interesting to take artists accustomed to working with physical things and “hand them this new medium, this new tool that no one knows how to use.”

In that same video many of the artists exclaim that this technology is “magical” and “incredible.” Yok, of the street art duo Yok & Sheryo described it as “legal acid.” But what is perhaps more intriguing is the art that was actually created, and how people are able to view it. On the site for the Virtual Art Sessions, you can view four works from each of the six artists. Not just as static images, or even 3D models that you can turn, but also the process during the act of creation. You can then choose whether to watch it in real time, or speed it up, and whether to view it from outside where you can turn and zoom in and out on the art being made, or from the artist’s point of view.

showing the act of creation from the creator’s eyes

Viewing this art, one may notice that even given this virtual space, the artists often are still creating something like their usual medium. Andrea Blasich’s sculptures made with Tilt Brush still express as much with shape as with texture. Katie Rodger’s flowing dresses and 3D drawings have the same organic, nature-inspired feeling of her other art. Seung Yul Oh is an installation artist, and although you can turn and view his work from any angle, the most compelling view is within the art itself. But perhaps the most interesting piece of art to come out of the experiment was the website itself. By allowing viewers to twist and turn the art as it’s being made, showing the act of creation from the creator’s eyes, Google’s Virtual Art Sessions become a sort of digital installation and performance piece itself. And that is truly unique.

You can explore the Virtual Art Sessions here.

Manipulate shapeshifting hell in Mason Lindroth’s latest game

Mason Lindroth’s animations exist somewhere between the realm of a hellish nightmare, surreal art, and collages. It’s all those things, and also none of them. Lindroth’s repeated animated aesthetic is wholly unique—there’s nothing else like it (and in fact, he even hand-sculpts some objects from clay). And that’s why when he does something as “trivial” as VA DA, a new “animation/drawing program,” it still resonates. It’s wild and bizarre, like so many of his other works before it.

A distorted conglomerate of gif-able lo-fi clipart

VA DA, as described above, is a simple “drawing” program. You control a space with your mouse, and drop in randomly generated items. You can change the color of the background, of the items, and even make the objects walk around on their own. The objects themselves are grotesque, ranging from eerie blank-staring faces to vintage stock-like footage of families. Nothing blends together, it becomes a distorted conglomerate of gif-able lo-fi clipart. While it may be a drawing program, it hardly has any actual player participation. You’re tasked to just sit back, and casually create your own randomly generated Lindrothian art.

Lindroth’s created nearly a dozen bite-sized game jam titles. His most developed game is Hylics (2015), a two-hour long JRPG-like experience; a delightfully weird and clay-filled adventure. In an interview with Kill Screen last summer, Lindroth described the game’s use of randomly generated text. “The player’s goals are communicated visually, by the environment design, so I felt free to make the textual aspects of the game into a sort of joke or red herring,” said Lindroth. “Everything else is there to present a certain atmosphere.” The same can be said for VA DA—or rather any of Lindroth’s games—the environment design is the focal point, everything else just falls into place around it.

VA DA was created for the 35th Ludum Dare, a themed semi-annual game jam competition. April 2016’s theme was “Shapeshift,” a theme that Lindroth realized in a notably complex way. The objects don’t necessarily shapeshift at the player’s behest, but instead move on their own. The shapeshifting isn’t at the forefront of VA DA, instead it’s in the background, shifting on its own without a care for player input.

Create your own Lindrothian nightmare in your very own browser here .

A videogame that’s also a poem about someone else’s dreams

Popularized by the 122 tape-recorders scattered across BioShock’s (2007) sunken city, the audio-log is a device for dispensing story details in voiceover to a player who might be more absorbed by shooting baddies. Audio-logs allow for writing to be integrated into a game which otherwise would not support the story formats we’re already familiar with through text or radio or film: usually they are unobtrusive and not integral to the experience. This is not always true: in Gone Home (2013), the audio-logs represent pages of a diary, and are not just the central way in which the story is told, but the most prominently emphasized feature of the game. In either case, players are able to explore writing at their own pace and in their own progression.

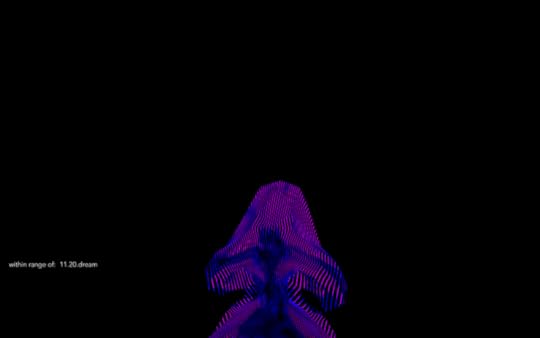

Diana Hamilton’s Dreams is a project that integrates poetry into a game space by reimagining the audio-log. Coded and created by Alejandro Miguel Justino Crawford, the game lets the player navigate a large black expanse to track down bouncing brightly-lit canisters that broadcast the voice of poet Diana Hamilton as she relates her dreams, full of strong imagery and complicated social dynamics. The dreams sound like they’re being relayed from bed—there’s a quietness to the voice, and the presentation feels unprocessed and unpolished: she coughs, she restates, reconsiders.

The canisters bounce away from a player who gets too close, but can be heard at a distance, which, at times, creates a chorus of dreams. Words and mental images are overlaid on one another and nothing can be totally discerned or pulled out of anything else. It is a work firmly grounded in poetry, and one that demonstrates the difficulty of remembering or relating a dream you can’t quite pull from your subconscious.

Crawford’s game approaches the truth of dreams

When asked to nail down a definition for poetry, Hamilton suggested that “The easiest way to know if something is a poem is to find out if anyone has called it one. This is not sufficient, but it helps,” and in that sense, Diana Hamilton’s Dreams is not just a collection of poems in the form of a game, but is itself a poem: it’s a collection of stanzas, beginning at the bed, and linked by the neon lines the player draws by moving from audio-log to audio-log. Hamilton’s definition of poetry also says that maybe “poetry involves a greater degree of connotation over denotation, or some less specific lack of utility, enabling us to recognize poetry in prose; poetry is a naming function; it’s a truth process; it’s one output of the movement of Spirit.” Crawford’s game approaches the truth of dreams not necessarily through the neon visuals, but through the navigation and connection and layering of sounds and stories that, half-recognized, slip away when we try to tie them down.

Diana Hamilton’s Dreams is the 200th release from Gauss PDF, an online publication started and maintained by J. Gordon Faylor, who saw a need for it in the experimental poetry scenes in New York and Philadelphia. In the changing landscape of the digital humanities, Faylor’s Gauss PDF imagines file types as genres.

Alejandro Miguel Justino Crawford is a poet and video artist. He has directed music videos and live visuals for several bands, including MGMT and Tame Impala, and he’s made a couple games, too. More of his work can be found here. Diana Hamilton’s website is here, and the Gauss PDF collection is here.

An Edgar Allan Poe classic is now a game

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

The Pit and the Pendulum (PC)

BY PAPER PIRATES AND SOKOLAB

Given that Edgar Allan Poe focused on sensation to communicate the terror of torture in his 1842 short story The Pit and the Pendulum, it would have been wise to further etch that out in the videogame version. In particular, the hissing of a swinging blade as it descends upon the narrator’s flesh could have been realized with actual sound, yet it is lacking in this digital adaptation. Forgoing that, what this game does achieve is realizing in its players the same sense of being as lost as the story’s narrator. Clicking frantically around the iron cell mimics the prisoner’s blind fumbling in the pitch black. Having him pace the cell in confusion as the player searches for something to do (since the game lacks prompts) matches the description from the original short story. While this videogame adaptation of Poe’s story lacks in some areas, it does manage to successfully position us as the confounded narrator, not knowing what to do (if anything) and what will happen next—a vital instrument in torture methods throughout the ages.

Perfect for: Literature geeks, time keepers, executioners

Playtime: 15 minutes

Fragments of Him finds the everyday poetry of grief

It is very, very hard to talk about death and grief without falling into platitudes. But we have the elegy to save us from the cliché—that form of poem or writing that seeks to capture the abyssal depths of the writer’s despair over the absence of the departed and impart some singular meaning to that life and its end. Take, for example, the nineteenth-century poet, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who wrote In Memoriam, A.H.H. (1849) in response to the sudden death of his closest friend and future brother-in-law sixteen years earlier. The book consists of over one hundred and thirty smaller poems—called cantos—that rove without any real structure over a number of topics: from the merest lament over physical absence to an examination of how loss can be reconciled with Christian belief. In form, In Memoriam is emblematic of a particular kind of mourning: there is no set agenda, no argument to be parsed out, just a scattering of images and ideas that, taken together, impart some sense of the person lost and the feeling of loss itself. “That loss is common would not make / My own less bitter, rather more: / Too common! Never morning wore / To evening, but some heart did break.”

Other elegies are more particular. They speak of death and grief obliquely, referring often to time—when lilacs last in the dooryard bloomed (Walt Whitman)—and location—when walking down the sunny pavement of Greenwich Village (Allen Ginsberg)—in order to fully map out the terrain of loss. In essence, poets find every possible permutation of the rote phrase, “she died,” because that phrase lacks (or is superfluous in) the particular connotations that the mourner is trying to bring to it. But even elegies fall into cliché—“’tis better to have loved and lost / than never to have loved at all” comes from canto 27 of In Memoriam—and so we keep writing them.

This is not passive, second-hand observation, but active participation

Fragments of Him is in this tradition: a videogame spent exploring and elegizing the life of a young man named Will through the memories of his grandmother, an old flame named Sara, and his boyfriend Harry. Originally conceived three years ago as a small experiment in interactive grief, Fragments has since grown the wings and talons of a fuller experience: framed by the narrative of the departed’s past and the effect that death has on his loved ones, the game functions as an elegy for Will through the experiential element particular to videogames. That is, when his grandmother waxes nostalgic over the preschooler Will, the player is literally brought back to that sunny morning and builds marble mazes with the pair. When Sara reminisces over the beginning of her relationship with Will, the player stumbles through a campus pub with her. This is not passive, second-hand observation, but active participation: the small, mundane moments of life are dredged up and given a vibrancy that is meant to contrast poignantly with Will’s death. So far so good.

But what marks Fragments as distinct—as, partly, in poetry—is its reliance on metaphor: the constituent parts of these memories are the physical objects the player interacts with, but they come to stand in for the personal, emotional connotations that accrete upon all of our things. The bear in Sara’s dormitory is not just any bear, but the bear that was given to her mother by a co-worker, and which has accompanied that young woman through her early romance with Will. The player’s interaction with objects is the only way of progressing the story—by laying down one toy after another, the player triggers the next segment of dialogue, tying these more tangible representatives of Will’s life to the intangible elements. Will’s books come to represent his presence in the way, that possessive adjective—his books, his clothes, his picture—speaking not merely to the fact that they are owned by him, but that ownership’s corollary: that they represent some essential quality of the character through that possessive relationship. “Dark house, by which once more I stand / Here in the long unlovely street, / Doors, where my heart was used to beat / So quickly, waiting for a hand” (canto 7). You shall know a man by the contents of his bathroom, and the singular grief of a single toothbrush.

And just as it is hard to talk about death without bromides, it is hard to conceive of a life without the quotidian: playing through Will’s last morning is marked by the overwhelmingly mundane details of making tea (the game is set in England) and cereal, of showering, of brushing teeth and putting on deodorant—all the while listening to his thoughts as he plots marriage and chafes against the very idea of a routine. Flashbacks from other characters’ perspectives leap in, interrupting the morning’s ablutions with the story of a first date, or a past discussion of Princess Diana’s divorce from Prince Charles (again, the game is set in England). In essence, the game relies upon a superfluity of mundane items—towels and tea—to transmit the day-to-day reality of the man’s life. There’s nothing particularly special about that life—but that contradictory structure (uniqueness out of ubiquity) is what makes Will real enough to mourn.

The game, in essence, relies upon this “and, and, and, and” structure, the player piecing together shard upon shard not to put back together that which was broken but to understand what it looked like in the first place. Going through the morning’s routine with Will and Sara and Harry, clicking on object after object to propel breakfast, and the layout of a dorm room, and a pub, and a comfortable, sunny flat is meant, however disjointedly, however obviously, to bring the player into a sense of intimacy Will through the people and objects that yet remain. The second half of the game then tears this metaphor apart: the repeated removal of furniture and books and pictures only serves to create an absence that speaks of the departed just as clearly as their presence did.

It is in the living to try nevertheless

When taken out of ourselves, we are just such an accumulation of details: people, characteristics, places, memories, and so on. Anyone can go to University; only, Will went to the University of Manchester. Anyone can have a boyfriend; only, Will’s was named Harry. Fragments is predicated on the utterly pedestrian—and yet utterly true—idea that those constituent elements can be pieced together to form something of a cohesive narrative, even if the gap between what the player experiences while witnessing Will’s thoughts and what can be reassembled from the other characters remains insurmountable. But it is in the living to try nevertheless.

At the end, the sentiment is Hallmarkian—grief wrapped up in a tiny bow, the image of a sole figure walking down a path alone, wounded yet whole, and a group hug representing solace in a communal grief—and the writing is, at times, tedious. The constant clicking of object after object can be repetitive and their significance can be, at times, bromidic: Christmas is always special, and every first, doomed love always evokes Romeo and Juliet, and every love was absolutely worthwhile, and so on. But we can never quite escape cliché: platitudes are common because they are absolutely transparent, easily familiar, readily comprehensible. Loss is readily, almost preternaturally, understood by virtue of its ubiquity—even as elegies try to dodge bromides while guiding the reader across the ragged contours of a particular grief. At its best, Fragments of Him says, “No, you really don’t understand. Let me show you.”

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

May 4, 2016

A jazz tribute to one of Super Smash Bros.’s greatest performances

Legend has it that before recording “Maggot Brain,” Funkadelic frontman George Clinton told his guitarist Eddie Hazel to “play like your momma just died.” The resulting track is a 10-minute journey through the cosmos that slowly calcifies into a sad, wonderful kind of musical ego-death. Not only is it one of the finest pieces of musical expression ever recorded—it was all done in a single take.

For Super Smash Bros. Melee (2001) fans, one such moment of sublime perfection happened just last year, at the B.E.A.S.T 5 tournament in Gothenburg, Sweden. It was the grand final, as world-renowned Peach player Adam “Armada” Lindgren faced off against the rising Fox player William “Leffen” Hjelte. In a best-of-five series, Armada was already down 2-1, and his two losses were so convincing that for a minute, it looked like Leffen would emerge from status as a “very good” Melee player to a Melee player who could dominate the game’s uncontested “Five Gods” in a major tournament setting. But in the fourth game, Armada pulled out all the stops: not only did he snag the victory—he didn’t lose a single stock in the process. In Smash, this is a rare feat in top-level play; about the equivalent of pulling off a no-hitter in baseball.

There’s an almost sacred feel to all of these performances

Every performance-based medium has its share of “Maggot Brain” and B.E.A.S.T 5 moments. There’s Kobe Bryant’s 81-point game against the Raptors, Whitney Houston’s earth-shattering rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner at Super Bowl XXV, Daigo Umehara’s legendary victory over Justin Wong at Evo 2004. There’s an almost sacred feel to all of these performances, as if the universe had perfectly aligned to bring us top talent performing at the top level in a peak pressure scenario.

Just as Hazel’s “Maggot Brain” solo would later go on to influence guitar greats like John Frusciante, Carlos Santana, and Dean Ween, Armada’s B.E.A.S.T 5 stunner against Leffen has also inspired a glut of performers who take direct influence. But on top of granting a morale boost to the top-tier Peach players of the world, Armada’s 4-stock victory over Leffen has now inspired a less orthodox tribute in the form of an improvised musical solo.

In a new video called “Musical Melee,” jazz drummer Caleb Goss “covers” the Leffen/Armada matchup with a play-by-play soundtrack that imitates the game’s action in sonic form. When Armada’s Peach gets knocked off the stage, Goss slams the crash cymbal. When Leffen’s Fox fires his signature laser beams for chip damage, Goss taps out a barrage of rim clicks. The combined effect is a wonderful synesthesia that captures greatness across mediums: contrasted with Goss’s constant backbeat, Armada’s every movement transforms into a perfectly assured tightrope act, each hitbox placed just perfectly enough to make contact, every spot dodge an uncanny read of Leffen’s tells.

The funny thing about this tribute is that after tying the series at 2-2 with this flawless performance, Armada actually went on to lose B.E.A.S.T. 5 to Leffen in the very next set. To this day, the tournament is still remembered as Leffen’s breakout victory. But that’s not the point: Kobe’s Lakers didn’t win the championship in the season of his 81-point performance, either. As Goss’s solo illustrates, the most compelling inspiration comes from the latticed inner-workings of the art itself.

Soft Body brings colorful elegance to bullet-dodging on May 17th

According to a new post over on the PlayStation Blog, bullet-dodging puzzle game Soft Body will be releasing on May 17th for both PlayStation 4 and Windows, with PS Vita and Mac versions to follow soon after. It’s also got a new trailer to go along with the announcement, as well as a sneak preview of some of the game’s levels from creator Zeke Virant, during which he discusses how the game’s soft presentation works together with its nonetheless hard challenges.

For the uninitiated, Soft Body is about controlling two “beautiful, gooey” snakes in tandem with each other, all while trying to dodge gunfire and “paint” various light panels into existence to build a new, blocky world. It’s a coordination-heavy setup, which Virant describes as something of a mix between the color-changing confusion of Ikaruga (2001) and the short but intense obstacles courses of Super Meat Boy (2010). “Soft Body’s levels encourage motion,” he writes. “Fast and slow, hectic or careful.” At the same time, the environment is serene and meditative, inviting players to endure its challenges with sometimes colorful, sometimes eerie art styles, and almost always an ethereal string of distant musical notes. As a previous trailer explained, this is more “bullet heaven” than bullet hell. But, I mean, it’s still bullets, and they still hurt.

more “bullet heaven” than bullet hell

This duality of conflict versus comfort becomes apparent in “Way of Life,” a level in which the player’s snakes Voltron together to form a single body. The map is chock full of deadly obstacles, with a spinning turret that never stops firing bullets, a sniper turret that always shoots directly at the player, and electronic floor traps that explode if the player stays on them for too long. It encourages on-the-fly puzzle solving, but it also takes place in an easy-to-read and nostalgic wireframe environment reminiscent of Asteroids (1979), just one of the game’s many ever-changing art styles.

The ironically named “Hard Game” levels, meanwhile, put players in control of both snakes at once, and if either is destroyed, both lose. There’s a level called “Quoting Ourselves,” in which both snakes must work together to save each other from bullets that one is invulnerable to but the other is not, and a level called Inside Circles, in which one snake must rescue the other from a bullet-prison before they can solve the puzzle. Both are bright levels, featuring vibrant pinks, blues, and yellows, and all are accompanied by ambient soundtracks that should be familiar to fans of NPR’s Echoes program.

“I want people to take tons of small risks,” writes Virant. “To push their luck, and to search for new approaches.” It’s not the first time a game has used its presentation to make classic arcade challenges feel more approachable, of course—Soft Body game has a distinctly Rez (2001) feel to it—but as we previously noted, its distinctly balletic style does stand in stark contrast to more conventional, testosterone-fueled shooter games like Gears of War (2006). Both like bullets, but if Marcus Fenix is someone you might share a Monster energy drink with, then the snakes from Soft Body are more likely to offer to a very special kind of brownie instead.

Soft Body releases for PC and PlayStation 4 on May 17th. To see more, including full playthroughs of more levels, visit its official website.

A brief history of men who build female robots

This is a preview of an article you can read on our new website dedicated to virtual reality, Versions.

///

You probably saw the news about the Chinese guy who created his own robotic Scarlett Johansson in his flat, right? Ricky Ma has caught the attention of many during the past weeks not just because he managed to build a robot that looks just like the American actress, but also because he did this all alone, and because he doesn’t admit the resemblance. Besides the discussion of how this could become a legal issue, the robot named Mark 1 also brought (back) to the surface the question of whether realistic female robots would be yet another source for the objectification of women.

The issue has already been addressed by Wired and Dazed Digital, but Ma doesn’t seem to comprehend that. When asked if his robot could be objectifying women, he replied “I’m not sure of this question.” He states that, in spite of the robot’s possibilities to interact with people, winking and smiling when you tell her she is beautiful, Mark 1 is used purely for scientific reasons and there is no contact with her on a more personal level.

After spending 24 years in the graphic and product design field, it seems Ma has made his childhood dream come true. He bought himself a 3D printer, spent over $50,000, and created Mark 1 in 18 months. But he doesn’t think robots could replace humans, even though they are, indeed, important assets for the economy. On the other hand, Ma says that human-like robots will definitely be popular in the future: “It’s just a psychological thing.”

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers