Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 123

May 10, 2016

Bat simulator realizes echolocation in Tron-like neon

Tron (1982) is a dope science-fiction film. Maybe it’s the dopest sci-fi film. And maybe it would be even doper if it starred a bat, instead of a digitized Jeff Bridges on a lightcycle. In the game Winging It that exact fantasy is realized.

After booting up Winging It, my screen turned dark—which is an unusual. There’s no menu and no instructions. Instinctively, I clicked, and a sound shot out to reveal my surroundings. A wave of sound that revealed on-screen that I am a bat. But not a photo-realistic bat, or even a cartoon bat. Instead, I’m a bat that, yes, looks like it’s straight out of the Grid from Tron. I’m a wireframed bat, in a neon-lit, barren cave. The click of my mouse serves as my echolocation, and is my vision to exploring the abyss.

Constant echolocation is necessary for success

Winging It was born out of the Toronto Game Jam 11: Don’t Stop bEleven (the theme: “There Will Be Consequences”) as a collaborative effort between veteran game developer and animator Sagan Yee, artist Ksenia Eic (apparently her first game-making project, as it turns out), and composer Jake Butineau. Yee’s the most seasoned of the bunch, and handled the Unity-bound programming for the game, as Eic conceived the art and modeling, and Butineau orchestrated the music and sound.

The goal of Winging It imminently is to reach the “Cave of the Toronto Game Jam Goat,” using your bat’s echolocation to light the way and knock down any obstructions in your path. The cave itself seems endless. Constant echolocation is necessary for success, because if you don’t use it, you may just lose your way and fall into perpetual darkness.

Soar through the caves of this Toronto Game Jam 11 submission on Mac and PC, available for free on itch.io .

Iron Man’s suit designer is now working on actual space suits

All space travel is fiction. Alright, it’s not fake in the “we didn’t go to the moon” sense of the term, but it necessarily involves the creation of tales to justify what remains a riotously expensive undertaking. “Major achievements in space contribute to the national prestige,” American Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara noted in 1961. “This is true even though the scientific, commercial or military value of the undertaking may … be marginal or economically unjustifiable.” In the years since the space race, this calculus is even more complicated. Much of what humans now do in space is quite tedious; waiting and experimenting with dirt is not the stuff thrillers are made of. Space may be the next frontier, but in grand narrative terms that is not always enough, which is why stories still need to be told.

What, then, are we to make of the news that Elon Musk’s Space X has hired costume designer Jose Fernandez of Tron: Legacy (2010) and assorted superhero movies fame to design their spacesuits? This is perhaps the least shocking surprise in recent memory: the studiously geeky billionaire hiring the man who designed Iron Man’s suit. At first glance, the whole thing calls for an eye-roll and a muttered “of course.”

It’s not like we weren’t warned. As Gizmodo points out, Musk has priorities in this regard. A year ago, in a Reddit AMA, the Space X supremo wrote:

Our spacesuit design is finally coming together and will also be unveiled later this year. We are putting a lot of effort into design esthetics [sic], not just utility. It needs to both look like a 21st century spacesuit and work well. Really difficult to achieve both.

We don’t yet know what Fernandez’s suits will look like, but there’s no reason to think of them as an outlier within Space X’s operations. This is, after all, an operation where promises of Mars Colonies exist alongside the more mundane (and important) work of launching satellites. As with McNamara 55 years ago, Space X is trying to figure out the balance between work that is impressive and work that has a clear upside. The private sector, however, has an advantage over NASA when it comes to playing the narrative appeal and design cards.

There is another historical precedent worth keeping in mind here, as recounted in Nicholas de Monchaux’s magisterial Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo. In short, the original plans for NASA’s spacesuit, as developed by military contractors and other putative experts, were hard-surfaced creations that looked like evolved forms of diving suits. In hindsight, they looked like bloated versions of Iron Man’s suit. These hard suits were also highly impractical, making it impossible for astronauts to move around. The final, soft spacesuit was actually made by the undergarment manufacturer Playtex, because they were the rare company with enough experience to sew the suits to the requisite tolerances.

The story of the Playtex spacesuit can be seen as a good sign for Fernandez’s suit design. This is, after all, not an area historically dominated by military experts. Who is to say a costume designer, working in conjunction with engineers, might not do well? Yet the design of the Apollo spacesuit is also a reminder that the future rarely looks like we expect it to. Playtex’s suit did not necessarily embody sci-fi futurism, but it got the job done. Private space companies, including Space X and Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, have a major advantage when it comes to weaving futuristic narratives. When it comes to putting those ideas into practice, however, such futurism isn’t always the answer.

The dreamy, underground worlds of Lilith

This article is part of our lead-up to Kill Screen Festival where Lilith will be speaking.

///

Originally published in October 2014. Header illustration by Jordan Rosenberg

///

“I made the piss game.”

That short, demonstrative line is the entire “About” text of artist and game maker Lilith’s Patreon page, but in its simplicity and directness, it says so much. Firstly, it’s a true statement; Lilith (aka Lilith Zone/Megiddo/Rusalka, aka Cicada Marionette, aka Elizabeth Deadman) did indeed make a game called Crypt Worlds where you pee on anything and everything from a first-person point of view. But the 5-word descriptor is also a terse, upfront, and potentially polarizing stump speech. It lays out expectations for would-be crowd-funding supporters quite clearly by asking if they’d be into “the piss game” or something like it. Lastly, it’s not a stretch to imagine Lilith’s About line as her efficient answer to the ever-troublesome question of “what kind of work do you do?” rather than launching into some convoluted, oft-recited artist statement. Obviously, “I made the piss game” isn’t an all-encompassing descriptor of Lilith as an artist, but it’s an apt welcome mat for the underworld lair where her games reside.

And to be clear, there’s a lot more to Lilith’s games than just bodily fluids, too. The games oscillate between dark and lowbrow humor, the serene and the occult, and the austere and the destructible. In Crypt Worlds you have 50 in-game days to decide the fate of the world, whether or not you realize it when you’re planting skulls in your backyard garden or collecting gold out of trash cans. My first time playing through the game I accidentally summoned the Chaos God, which turned the entire world into a barren, red hellscape, at which point the only thing left to do was restart from the beginning. These aren’t games that play by the typical rules that dictate most videogames. While they incorporate game-y concepts like exchangeable currencies, collectibles, and environmental storytelling, in many cases she totally subverts the ways those concepts function.

Lilith achieves this in part by doubling down on the externally applied “low culture” status of videogames, treating that lowness as the medium’s chief asset and also a point of personal ingress. In her games, this lowness manifests through muddy, low-resolution textures that cover most of her virtual architecture and characters, humor that could be considered lowbrow, personalities that seem sullen or sarcastic, and the topographically low and underground spaces where many of Lilith’s games take place. “I loveeee blurry textures—real world forms reduced and stretched, removing detail, leaving vague ideas and shapes of what it was,” Lilith told me. “It feels like wandering around dream versions of places you’ve been, half-constructed foggy architecture and people and objects, existing in the context of a place you can believe, but pulled from that reality and put in its own context.”

“I feel connected to things that are broken, ‘bad,’ trashy.”

While even an established classic like Super Mario Bros has underground areas, many of the “low” characteristics are associated with bad taste, brokenness, or ineptitude: not the adjectives that commercial game developers want associated with their products. But for Lilith’s creative sensibilities, that environment resonates most strongly and perhaps most honestly as well.

“A lot of my defining memories are alone in mazelike hospitals, long road trips and strange hotels, staying at psychiatric wards, forced inside with only artificial light for days,” she said. “I fixate on these images a lot. I’ve always felt alien—like I’ve slipped between the cracks and exist outside the world. To that end I feel pretty connected to things that are broken, ‘bad,’ trashy … things that exist outside of legitimacy. A lot of being ‘good’ just seems like posturing, being able to create things that fit within an established discourse. I wanna wallow in shadows, to be illegitimate, to create personal mythologies and secrets and dark underground tunnel systems …”

Lilith’s Tape Dream is just one example of those aspirations come to bear. In Tape Dream, you’re confined to a dank, indoor space, lit by candles that spew plumes of flames upward as if they were tiny bonfires. You share the space with a floating, monstrous creature that looks like an oversized human heart fused with a mutilated chicken. Its body is coated with a fine red static that undulates as it breathes heavily. It’s unsettling, needless to say. In another room is a VCR, and VHS tapes are scattered around; one is labeled “God,” another “Zin,” and the other two are stamped with strange symbols. You can pop them in the VCR one by one as a nearby monitor displays abstract images and emits down-pitched, sometimes indecipherable soliloquies about the order of the universe. If you like, you can toss the VHS tapes in a nearby brazier where they explode into a cloud of smoke and smog up the place, making it feel all the more claustrophobic. I don’t know any way to exit the space or “finish” the game besides quitting the application.

Tape Dream and most of Lilith’s other games operate within a sort of dream architecture. Most videogames present players with puzzles or challenges to conquer: fit these differently shaped blocks together, shoot the aliens before time runs out, reach the finish line first. Lilith’s games don’t incentivize you toward specific goals other than offering the toy-like experience of tinkering, testing boundaries, and seeing how the game responds. We rarely find answers in dreams while we’re dreaming them—they are moments that we drift through, leaving only traces of subconscious imprints and déjà vu as clues for waking interpretation.

We rarely find answers in dreams while we’re dreaming.

Lilith’s games contain traces of one another too, often sharing characters or assets across titles. You could read this as an analogue to recurring dreams, or simply an allusion to the interconnected ways that our brains store and retrieve information. “I always loved how in old Nintendo Power magazines you’d see screenshots and blurbs for the same game over time, but they would change (sometimes drastically) as production went on,” Lilith explains. “For me, it created a world that was separate from the end thing, but also intrinsic to where it went. I want to replicate the feeling of the way images and excerpts of text augmented these lil zones, but also felt important on their own terms; mysterious microworlds that are part of this larger thing, an incomprehensible barrage of media.”

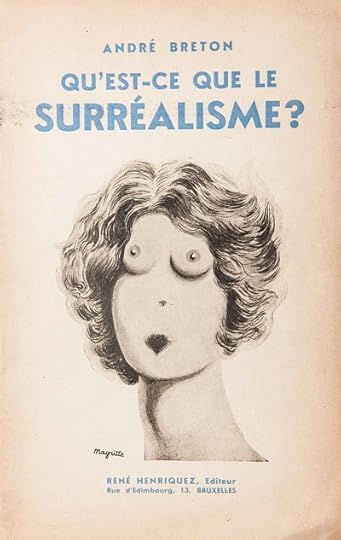

Oneiric Gardens again makes the dreamscape explicit via its title, but contains imagery that places it in line with elements of Surrealist tradition. In Oneiric Gardens, you explore the interiors of several structures housed within a deep underground cave. One building in particular contains a portal that transports you to an endless, crystal ocean, dotted with a few sandy islands and monolithic ruins—as well as kitschy beach houses, palm trees, and a surfboard. The pronounced, distant horizon line and familiar-yet-strange imagery are right out of Surrealism’s playbook. In 1924, artist André Breton wrote the Surrealist Manifesto, which defined the movement as “pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought.” In Oneiric Gardens you explore diorama-like thought spaces moreso than complete levels.

Oneiric Gardens again makes the dreamscape explicit via its title, but contains imagery that places it in line with elements of Surrealist tradition. In Oneiric Gardens, you explore the interiors of several structures housed within a deep underground cave. One building in particular contains a portal that transports you to an endless, crystal ocean, dotted with a few sandy islands and monolithic ruins—as well as kitschy beach houses, palm trees, and a surfboard. The pronounced, distant horizon line and familiar-yet-strange imagery are right out of Surrealism’s playbook. In 1924, artist André Breton wrote the Surrealist Manifesto, which defined the movement as “pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought.” In Oneiric Gardens you explore diorama-like thought spaces moreso than complete levels.

However, Lilith’s videogame version of the Surrealist process feels fresh, and not shackled to a dusty manifesto. Perhaps this is due in part to the more contemporary, interactive nature of videogames, which inherently feel less prescribed and authoritative than paintings seeking to encapsulate the “vision of an artist.” There’s a playful exuberance in Lilith’s games that detaches from points of reference just as quickly as one can make those connections.

“Honestly, more than anything I just want to be making playgrounds at this point,” she said. “I always love how so many early 3D games seem equally confused and excited about prospect of ‘THREE DEE VIDEOGAME’ and feel so loose and free [as] self-assured jungle-gym worlds.” In Oneiric Gardens, as with the rest of Lilith’s catalogue, it’s not important to draw distinctions between Lilith’s “psychic automatism” and the simple, dreamlike experience of playing in the space. Instead, I’d recommend just sitting back and soaking in the heaps of turbid textures, while occasionally leaning forward to piss into the void.

///

To learn more about the Kill Screen Festival and register, visit the website.

Visit the latest haunted cities from the queen of horror games

Further cementing herself as an architecture goddess, Kitty Horrorshow has publicly released a collection of three games and a flash-fiction story called Haunted Cities. These were all projects originally made as exclusive rewards for those backing her on Patreon for $5 a month, the deal being that you get one of Horrorshow’s virtual worlds a month for the subscription—these four were released across November 2015 to February 2016.

If you’re familiar with Horrorshow then your expectations for Haunted Cities shouldn’t be amiss. These are lo-fi videogames that prioritize looming architecture and eerie synth work over everything else. Rather than offering, say, puzzles or enemies to shoot, instead the focus is upon the timbre of the virtual space. The idea that permeates is that these places exist for you to wander inside them for a short while, for you to do nothing but feel out topography, at most perhaps you’ll uncover evidence of life that dwelled there before you arrived. This goes some way to explain why every entry in this collection feels like a cross-section of a dreamworld—you are given a slice of a timeline and have to fill out the rest yourself.

“Leechbowl” is the most evident of this. It seems to have been built upon the singular idea of “an abandoned midwestern factory town” that was once filled with people (perhaps leeches?) obsessed with blood. Inside a bar, inside a farmhouse, even a convenience store, always at arm’s reach is a bottle of gore. It’s telling that it is displayed and sold without a label upon its clear plastic bottle, as there is no need to label it, as blood is the only commodity available in this industrial shanty town of corrugated iron and transmission towers.

It’s clear that the occupants of this town drunk the blood, as a poster behind a bar reads “Everything tastes better with blood,” and countless others allude to penetrating skin and supping on the plasma beneath (one of them even features a cartoon mosquito). Your role, however, is not to drink, but to throw these bottles of blood at the exterior walls of the buildings. A select few walls have messages written across them that are revealed when blood soaks them. And as if often the case with Horrorshow’s games, the writing here is chilling, effectively short and evocative in its threats—nightmares of teeth and blood lust.

it is there not to be explained, but to raise goosebumps

“Grandmother” breaks what has become something of an expectation in Horrorshow’s games: there is a living, breathing person. Until now, none of her games have depicted a human body. That is, outside of the recurring theme of architecture as a metaphorical representation of the body, and sentences that describe unseen bodies in various forms and strains. Here, you can walk into a darkened hut, and sat in a comfy chair illumined by the static light of a television is the titular grandmother. Her body moves with her breath, but she does nothing else, not even if you turn the television off to plunge her and yourself in absolute darkness. The rest of the game space comprises a thick forest in which the only landmarks to help guide you are dirt paths, lamp posts, a barn, and a convulsing pillar of dirt that stretches from the ground and beyond your vertical sight. What it’s doing there is a mystery. And as with everything else you can find, it is there not to be explained, but to raise goosebumps and stop you in your saunter.

The other two entries in this collection are “Pente,” which has you visiting a historic floating shrine—where you can enter an empty cathedral and walk by huge swords—and the flash-fiction story “Circadia,” which is “about a girl trying to cure a cassette tape’s infection.” Both of them cannot be mistaken for anything else than the terror-stricken fiction of Horrorshow, each concerned with an individual that has to deal with pain realized through media: in “Pente” it’s a digital world that contains memories of suffering; while in “Circadia” it’s a battle with a cassette tape.

You can download Haunted Cities over on itch.io. You can also support Kitty Horrorshow over on Patreon.

Uncharted 4 has no regrets

There’s a brief moment in the first hour of Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End where Nathan Drake, a retired treasure hunter, combs through the artifacts from his adventures that he keeps in his attic. The space is ruined with meticulous clutter—each individual relic a callback to some grand excursion—and as I explored this makeshift museum, I found myself falling prey to the same fond memories that overtake the game’s protagonist.

Sifting through this digital archive prompts Drake to discover his old holster, now holding a toy gun. Almost instinctively, I make him pick it up, and then I steer him as he darts between shelves of memories and shoots plastic balls at imaginary enemies. Soon, however, Drake shelves his weapon and remarks that he’ll clean up the mess later. It’s a brief moment of childish fun, but, in the end, I guess he has to grow up—until, of course, he doesn’t.

///

One of the enduring charms of adventure fiction is that it never hangs around long enough to age, or at least not in the same way as other, more “literary” fictions. Robert Louis Stevenson and H. Rider Haggard do not have the burden of timelessness; we can enjoy them as escapist diversions, bizarre artifacts from a particular time that now seem almost as ancient as the ruins that populate their pages. The study of adventure fiction is more often the study of empire, colonialism, racism, and the legacies thereof than the study of aesthetic genius. Treasure Island (1883) and King Solomon’s Mines (1885) endure as fodder for easy reading and popcorn cinema as we tell ourselves that the values they communicate remain in some distant past.

Illustration from Treasure Island by George Roux, via Wikimedia

That past catches up to Naughty Dog, the team behind the Uncharted series. When Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune (2007) released, it wore its pulp influences on its tattered, sweat-soaked sleeves, seeing Nathan Drake and his partner Victor “Sully” Sullivan blow up ancient ruins, shoot pirates, find the cursed treasure, and get the girl. Sure, it bore the ghosts of exoticism and the peculiar brand of racial problems of its predecessors, but most have accepted these missteps as the game’s commitment to the sloppy legacy of its genre. Drake’s roguish charm reappeared subsequently in Uncharted 2: Among Thieves (2009) when its cinematic bravado erupted across Tibet, using a troubled country’s crumbling traditional architecture as a backdrop for explosions and gunfights. By his third major outing, Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception (2011), the exploits of the series’ protagonist began to wear a bit thin. Smirks and witticisms can hide reckless destruction of antiquity and mass murder for only so long before one starts to notice the cracks in the genre mold that Naughty Dog uses for each entry in the series.

Naughty Dog waves this penitent iconography with a heavy hand

Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End is, in some ways, the studio’s attempt to see if Drake and the genre that it has explored with the series can, in fact, mature. After a tiresome first hour that tries to introduce Drake’s brother, Sam—whose absence in the series’ previous entries never stops being suspicious even after the game’s trite explanation for it—we see Drake at a menial job with a boring but pleasant domestic life with his wife Elena, the treasures from their previous exploits tucked safely away in the attic. When Sam returns and propositions Drake with one last adventure, this time in search of a treasure they sought together over a decade prior, Drake’s initial misgivings crumble under the weight of familial obligation and a pathological need to cultivate his own legend.

The latter proves the more convincing motivator for Drake and for Naughty Dog, too. Moving away from the more fantastic settings of the previous entries, the stakes in Uncharted 4 feel more personal, the quest more grounded. The magical cities or mystical artifacts that began each of Drake’s prior adventures are replaced with a simpler macguffin: the treasure horde of Henry Avery, a pirate who marks his trail with statues and artifacts bearing the likeness of Saint Dismas, the repentant thief crucified alongside Jesus Christ. Naughty Dog waves this penitent iconography with a heavy hand, but this is not a series known for its subtlety. From its onset, Uncharted 4 insists that it will be Drake’s final adventure, investing even the most bombastic moments—from an Ocean’s 11-style auction heist to a car chase through a Madagascar market place—with a tinge of bittersweet resolve.

This air of seriousness, however, never attempts to elevate the game above its pulp trappings. That is, in an effort to make a more mature game, Naughty Dog doubles down on the adventure fiction tropes it has spent so many years attempting to perfect, focusing its efforts on meticulous detail to achieve a remarkable level of fidelity. Grass bends realistically as Drake and Sam hide from patrolling mercenaries. Mud convincingly clings to Drake’s clothes as he gets dragged behind a vehicle. Props and pieces in any given locale beg to be considered with a careful eye, even as Drake sprints past them to dodge a hail of gunfire. This obsession with visual minutiae seems all the more impressive when the game’s camera languishes over the grand vistas of misty Scottish cliffs or the lush green of a Madagascar jungle.

Many of these visuals splash across the screen during scripted moments, of course, but there are areas that offer at least the illusion of openness. Driving across the rocky terrain of Madagascar with Sully and Sam in the passenger seats, it’s possible to take brief excursions to ruins that dot the landscape, and in these quiet places between explosive firefights, I almost forgot that I was being funneled along a narrow narrative path. As I used a winch to pull the jeep up a steep mud bank, I found myself wanting more opportunities to slow down and explore at my own pace without the inevitable gunfight interrupting my own adventure, one with a bit more introspection than the game’s genre would ever allow. Like so many works of adventure fiction, Uncharted 4 hints at a much larger, more complex world, but it is only ever concerned about a small part of it—namely, those parts ripe for plunder.

Uncharted 4 never pretends to be anything other than the sum of its highly-polished parts

As a result, Uncharted 4 falls back on predictable story beats pulled straight from the hallmarks of its genre. While there’s enjoyment to be had swinging from a rope, spraying rounds of ammo like some gun-toting Errol Flynn, the game’s overlong sequences of gunplay become tedious, especially in its third act. Treacherous ledges crumble with clockwork regularity in nearly every climbing sequence, and a laughable number of environmental obstacles require using the same type of crate to surpass them and reach new areas. By the game’s end, there are no more surprises, each encounter funneled down a narrowing alley of gunfights and cliff jumping that mimic the easy, digestible parts of adventure fiction. Any more self-doubt or confusion about motivation would shatter the illusion that Drake and his crew pursue anything more profound than a pile of gold and a story to tell.

That’s one of the limits of basing an entire franchise on a genre of fiction known for recycling locales and themes, I suppose. But Uncharted 4 never pretends to be anything other than the sum of its highly-polished parts. Its initial aim of interrogating the ability of adventure fiction to mature seems assured in the knowledge that it doesn’t need to. Pulp fiction has always been produced with the knowledge that it inevitably become trash, consumed and then thrown away, but Naughty Dog treats the genre with such confidence that it dares us to dismiss it. Uncharted 4 offers nothing profound, assured in its own way that it has nothing to prove.

In this way, Uncharted 4 has more in common with the works Haggard or Stevenson than it does the throwaway magazines of the 1940s-60s, being a well-made example of an ephemeral genre. That’s why, out of all the game’s explosive moments, I remember Drake’s time in his attic, playing with a toy gun in a museum of his own past. In his attempts to recapture a bit of his old self, he realizes that he can, indeed, grow up, even if his adventure fiction legacy cannot. As impressive as it is, it remains an artifact more suited to a curiosity cabinet than a model for a way of life. For him, and for Naughty Dog, too, that’s enough.

May 9, 2016

Don’t Kill Her turns murder mystery into a hand-drawn delight

Call him Wuthrer, call him Wuthrer Cuany—call him any name you like. Just don’t call him conventional or compromising. The Swiss artist’s latest project, Don’t Kill Her, is an ostensibly two-dimensional adventure game drawn entirely in pencil. The title is up for vote on Steam Greenlight and is currently seeking funds on Indiegogo.

Driven by a central murder mystery in which the player character is said to be the killer, an unnamed victim narrates the dreamlike story as you make your way through Wuthrer’s sketchbook-esque world. While the artist is coy on specifics (“Don’t judge a game by its cover,” his website urges), there’s plenty to admire on the surface.

Aside from audio production—Siddhartha Barnhoorn’s music, Julien Matthey’s sound design, and Lara Ausensi’s voiceover narration—the game has been a fairly solitary endeavor. “All of the visuals used for Don’t Kill Her are the result of my sole relentlessness to fill a plethora of sheets of paper,” says Wuthrer, though “a few animations were created with the help of a well-known animation software that allows you to effortlessly add special effects or basic movement.”

“The animation of the ostrich with a tie, for example, is for the most part hand-drawn,” he explains. (See above.) “On the other hand, the balloon bobbing up and down is interpolated with Flash to avoid having to draw each frame of its movement. The combination of both techniques, namely traditional and computer-assisted animation, allows for this unique rendering—admittedly always vibrant, yet not without a certain softness in some parts.”

“Images become animated and can even possess a will of their own”

There are both practical and aesthetic advantages to this approach according to Wuthrer. The hybridized process “helps save a significant amount of time, which is more than welcome, as Don’t Kill Her is mostly a solo project.” The second advantage is far less pragmatic: “I really love imagining my creatures and characters in their entirety. To bring them to life, I cut them up in little pieces that I draw separately. I therefore find myself digitizing them and cutting out [individual parts of the sprites’ anatomy] one after the other before reassembling them within the animation software.”

Wuthrer confesses to taking great delight in his role as a kind of mad scientist. “The vital power that digital creativity holds really strikes me,” he says. “Images become animated and can even possess a will of their own with the help of artificial intelligence [and electronics] created with seemingly lifeless concrete materials.” And with Don’t Kill Her, he believes that he exacerbates this paradox, “drawing dismembered monsters on lifeless and innocuous sheets of paper in order to bring them to life with a machine.”

Born of a lengthy learning process marked by trail and error, Wuthrer credits much of his mixed-media technique to an academic background outside of game design. “I initially studied psychology,” he says, adding that he later moved on to a school of art and communication. “I’ve been able to effortlessly detach myself from traditional techniques and resources of game development. Hence the game’s distinctive appearance.”

Outside of games, Wuthrer’s artistic influences are many. “I have the awful habit of systematically trying to escape any form of stereotype,” he admits. “I’m part of a collective of artists, I practice Muay Thai, I organize beach dodgeball tournaments, et cetera. My centers of interest and inspiration tend to be multifaceted, as I have this urge to try out new things and explore the unknown, even when hostile. My approach to culture, in the broadest sense of the word, is identical.”

He admits it’s less about individual works themselves than the way people respond to them that interests him most. “I enjoy discovering what inspires passions, with their fascinations and contradictions, regardless of the field of interest,” says Wuthrer. “One could say that I’m a bit of an amateur anthropologist.” This outlook bleeds into his expectations for Don’t Kill Her, as well: “The game’s underlying message is open to interpretation, and the hidden meanings it aims to convey are numerous. As a matter of fact, I’m really looking forward to discovering each and every player’s interpretation.”

Cast your vote on Steam Greenlight and help make the game a reality at Indiegogo. You can also check out more of Wuthrer’s pencil drawings on his Tumblr blog.

Map slippage is real, and it’s about to matter

If an object does not exist on a map, does it exist at all? Do you? You can see it with your own two eyes, and yet it is exists outside your world.

In the early days of mapping, when much of the world was unknown, such discoveries simply expanded the known universe. There was a world beyond maps. But now that we go through life with the reasonably well-founded belief that maps can accurately capture the intricacies of our world, the process of mapping glitches raises a whole new series of problems.

When this happens in a game, it’s almost funny. In Halo 3 (2007), for instance, a Monkey Man existed outside a level map. The only way to reach it was to die and be reborn in a convenient locale. It was a glitch, to be sure, but it was hardly consequential. Indeed, these sorts of videogame mapping glitches populate obscure forums as weird collectibles in their own rights; mapping failures to be discovered (and, in some cases, remedied) by intrepid explorers.

The Halo 3 glitch was not all that dissimilar from the first famous internet mapping glitch. In the early days of Google Maps, if you asked for driving directions from an East Coast city to London, you were directed a specific pier, and then told to drive across the ocean. For those who were in on the joke, it was a delightful little Easter egg. For those who weren’t… well, who knows? Here’s hoping they didn’t take it too seriously.

Maps are more serious now. Perhaps they always were, and the public is just catching up. Google no longer tells you to drive into the sea, but as Justin O’Beirne pointed out in a recent essay about the evolution of the company’s mapping product, “the number of roads shown has actually increased.” He further noted that the placement of text in relation to labels had been standardized and fewer cities were displayed. This, one supposes, is what adulthood looks like.

infrastructure would eventually grind to a halt

We are now very much in the adulthood of geographic data. Just turn on a new phone and watch it be inundated by apps’ demands to use your location, some of which make more obvious sense than others. These uses of GPS, it should be noted, are but the tip of the iceberg. “There are now around seven G.P.S. receivers on this planet for every ten people,” Greg Milner, the author of Pinpoint: How GPS Is Changing Technology, Culture, and Our Minds, noted last week in The New Yorker. “Estimates of the system’s economic value often run into the trillions of dollars.”

As with all systems that are this valuable, the real questions involve what would happen in the event of a failure. In the event of a breakdown, Milner notes:

The Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency recently determined that, within thirty seconds of a catastrophic G.P.S. shutdown, a position reading would have a margin of error the size of Washington, D.C. After an hour, it would be Montana-sized. Drivers might miss their freeway exits, but planes would also be grounded, ships would drift off course, commuter-rail systems would be tied up, and millions of freight-train cars with G.P.S. beacons would disappear from the map.

It’s hard to know exactly what to make of these warnings. As the pilot-cum-journalist William Langewiesche once noted in The Atlantic: “Air-traffic control’s main function is to provide for the efficient flow of traffic, and to allow for the efficient use of limited runway space—in other words, not primarily to keep people alive but to keep them moving.” Planes, in other words, would be able to coordinate and land, but they wouldn’t take back off. The same holds true in other cases; drivers can navigate cities when traffic lights go out, but they are unlikely to plan further sorties. Milner is not wrong in pointing out that some drivers would miss their exits and that infrastructure would eventually grind to a halt, but immediate and widespread apocalypse—in spite of the speed at which GPS could fail—would be unlikely. Rather, the damage of infrastructure grinding to a halt that Milner alludes to would have a longer tail and speaks more to the importance of geographic data in the current economy.

That, in turn, brings up the second cause for concern raised by Milner: spoofing. Sending false signals over a short distance could conceivably affect certain devices. To wit, Milner notes:

Security officials have been concerned about the susceptibility of G.P.S. to spoofing since at least the early two-thousands. Fourteen years ago, a team at Los Alamos National Laboratory, in New Mexico, built a spoofer by modifying a G.P.S.-signal simulator (a legal device that tests receivers’ accuracy) and aiming it at a stationary receiver more than a mile away. The receiver’s display revealed that it believed it was zipping across the desert at six hundred miles per hour.

Seven years before the Los Alamos test, spoofing GPS was central to the plot of the James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies, wherein a British warship is slowly led off-course to provoke an international incident. Whether such a thing could actually happen is not really the point; Tomorrow Never Dies introduced GPS spoofing into the cultural vocabulary. It was, one must also note, a movie where a “stealth ship” remained invisible because, on multiple occasions, people relied solely on GPS instead of, say, looking out a window at a ship a few hundred meters away. (More on that in a moment.)

autonomous vehicles would crash into one another or living rooms en masse

The fear of spoofing, mind you, presupposes that the streets and locations we see on maps are accurate. This, though we don’t like to talk about it, is as much an article of faith as it is an objective truth. In China, Geoff Manaugh wrote in a recent article for Travel and Leisure, “every street, building, and freeway is just slightly off its mark, skewed for reasons of national and economic security.” In order to make a digital map in China, he notes, one needs government permission, a condition for which is the inclusion of a random offset in coordinates. “The result is an almost ghostly slippage between digital maps and the landscapes they document,” Manaugh writes. “Lines of traffic snake through the centers of buildings; monuments migrate into the midst of rivers; one’s own position standing in a park or shopping mall appears to be nearly half a kilometer away, as if there is more than one version of you on the loose.”

In most cases, this is just a strange edge case—something larger and more systemic than a glitch but also not much bigger than an inconvenience. (The random offset can be accounted for, but that requires expertise a layperson doesn’t have.) In marginal situations, however, 100m of variance in one’s location can have serious consequences. “If a traveler finds herself in, say, Tibet or on a short trip to the artificial islands of the South China Sea—or perhaps simply in Taiwan—are she and her devices really “in China”?” Manaugh asks. Strange things can happen when the borders experienced by humans and devices cease to overlap. (This, once again, is the plot of Tomorrow Never Dies.)

The various problems with mapping Milner and Manaugh raise are of this moment because the “look out your window and communicate”-solution suggested by Langeweische and known to drivers in the midst of power outages—though not the captain of that ship in the Bond movie—may have reached its limits. A self-driving car’s mental map of the universe, for better or for worse, is not the same as a human’s. It’s unfair to say that, in the event of a GPS failure or slippage, autonomous vehicles would crash into one another or living rooms en masse. At the same time, however, many of the advantages of autonomous technology, such as the ability to pack vehicles closer together would be much more affected by an outage.

As in Langeweische’s aviation scenario, vehicles wouldn’t immediately crash, but the system would (safely) grind to the halt. In a world where more devices depend on GPS and downplay the importance of human input, gaps between the borders experienced by humans and technology can be highly consequential. Indeed, one might even wonder which of these two geographic realities might be dominant.

Tale of Tales explains why it’s bringing Christian art to virtual reality

Since being successfully funded on Kickstarter in October 2015, details on Tale of Tales’s latest project, a digital collection of animated Christian dioramas titled Cathedral in the Clouds, have been light. “We haven’t produced anything yet,” explains co-creator Michaël Samyn, who is working on Cathedral in the Clouds along with his partner Aureia Harvey. However, during a recent presentation at France’s CFIC cultural heritage and digital media forum, Samyn finally released new information about the project, walking the audience through how he and Harvey came up with the idea for it, as well as how they’re hoping to translate the Gothic and Renaissance-era religious art that inspired it into virtual reality.

The presentation opened with a brief explanation of Tale of Tales’s history as a studio, as well as how the pair’s taste in art led them to games in the first place. “The art that we enjoy tends to be older,” explained Samyn, referencing the many cathedrals and religious structures of their current hometown of Ghent, Belgium. He explained that while they appreciate the realistic beauty and figuration of older art, the irony and abstraction of modern art “just doesn’t do it for us.” Because videogames, too, are often concerned with realistic representation, they decided to start making games as a way to “continue the traditions of art before modernism interrupted them.” Like Renaissance-era master painters and Flemish primitives, they see themselves as working with the high technology of the time to tell stories that are nonetheless an ancient part of Western culture.

A still from Samyn’s presentation likening games to traditional art

Despite being atheists, the pair has been drawn to work with Christianity, as it is a subject of much of the art from which they draw inspiration. “A lot of these paintings and sculptures depict religious themes and characters,” explained Samyn. “We look up to them, we admire them, and they help us understand and deal with our lives.” It is the universal themes of “kindness, patience, and self-sacrifice” found in the religious art that inspire them and that that they hope to make more accessible through technology. “We have a feeling that a lot of people now don’t experience that with old art,” said Samyn. “So we would like to create something that people can connect to more easily.”

This led to the idea for Cathedral in the Clouds, which hopes to recontextualize Christianity and its many artistic influences into a specifically digital experience that people around the world can access on almost any platform. The project is split into two halves, the first being a series of digital depictions of Saints for “desktop, laptop, tablet, smartphone, web, even video and print,” and the second being a fully-explorable virtual reality cathedral to house them. Because of its digital nature, Tale of Tales also expects the cathedral to be endless, with the ability to continually expand over time.

themes of “kindness, patience, and self-sacrifice”

So far, much of this has already been covered by the project’s Kickstarter page, but the next leg of Samyn’s presentation then laid out new details as to how each half of the project is being built. For the Saint depictions, they are meant to be like “home editions” of triptychs, devotional cabinets, and altars, showing a rendition of a scene around a central character, such as a Saint, the Virgin Mary, or Jesus. To depict the gravity of these figures, who Samyn compares to superheroes, they will be life size, meaning that users will have to scroll up and down to view the whole piece.

To take advantage of their digital nature, the cabinets will be animated, portraying specific biblical scenes and making dramatic twists to explain the significance of the character portrayed. However, Samyn insisted that the pieces not be viewed as “alive” so much as being virtual statues, again calling back to the art that influenced the project. “We’re very inspired by the style of medieval sculpture,” explained Samyn. “But also by African sculpture and even some modernists.” Rather than wanting the scenes to be photorealistic, he prefers that they be read as “symbolic representations of a realm that cannot be perceived.”

For the cathedral half of the project, which will collect all of the Saint depictions into a single virtual reality app, the duo expects a bit more work from its users. Whereas the saint depictions are being made with availability in mind, the cathedral will instead require users to overcome a number of barriers, including the cost of virtual reality, the discomfort of wearing a VR headset, and the public perception of VR as a “very nerdy, very uncool thing to do.” This is meant to symbolize the sacrifices medieval Christians would have to make to show their devotion, similar to how a monk might wear an uncomfortable hairshirt as a way to humble himself before God. Like planning a trip to Ghent to visit its famous cathedrals, Samyn stated that “a sort of pilgrimage will be needed to see our cathedral.”

Samyn ended his presentation by meditating on the connection between cyberspace and the afterlife. “Back in the 90s we thought of the internet as a place, a sort of other planet, where different rules applied,” he explained. “Sometimes it felt a bit like the afterlife, like eternity.” By placing a cathedral in the cloud, which is both a name for cyberspace as well as the supposed location of Heaven, Tale of Tales hopes to explore how these two non-physical planes intersect.

“a sort of pilgrimage will be needed to see our cathedral”

At the same time, Samyn acknowledges the Saint depictions themselves as not a space, but a time. Whereas physical art is experienced by sharing the same space as an object, he explains, digital art instead asks viewers to share time with it instead. Think of it as the difference between visiting a museum to see the original version of a famous piece of art and sitting down pretty much anywhere with an internet connection to watch a Netflix series. This is why it is so important to Tale of Tales that the scenes be animated, as “this is where the art happens.” As such, the hopes is that Cathedral in the Clouds not only reconciles both the ancient and modern interpretations of ethereal places, but also continues medieval traditions in a way that only modern technology can achieve.

The project is entirely non-commercial, and will be made available for free to anyone who has the technology to access it. As with a real cathedral, patrons are able to donate via Paypal or Patreon, or even make commissions for a new chapel in their name.

To learn more about Cathedral in the Clouds, you can follow the project on its website, tumblr, or Twitter. You can also download the slides from Samyn’s presentation here.

Cultural representation in Assassin’s Creed Chronicles: India

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

India is a diverse country, home to some 3499 separate communities and 325 different languages and dialects, according to one anthropological survey. But representation of the region in videogames has been lazy at best and non-existent at worst.

Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3’s (2011) campaign featured a single mission set in the city of Dharamshala with barely a trace of Indian culture, let alone accuracy. On the other hand, games like Final Fantasy and Smite (2014) tend to bend elements of Indian culture to fit the game’s needs or aesthetic (particularly with Smite’s voluptuous re-imagining of an Indian goddess). “There is a feeling of cringing when you have someone called Shiva, but the thing looks nothing like Shiva is supposed to look,” said Arvind Raja Yadav, an independent game designer who created his own role-playing game inspired by Indian mythology.

Assassin’s Creed Chronicles: India, however, is one title evidently more committed to authentic Indian representation. Set in a bustling city of sandstone and Rangoli patterns, Assassin’s Creed Chronicles: India, an offshoot of the main series, features a cloaked adventurer in the middle of the Sikh War of 1841. The mission is to recover the famed Koh-i-Noor diamond for the good of mankind—while killing a bunch of Sikh enemies along the way. As with other Assassin’s Creed titles by game publisher Ubisoft, plenty of historical research went into its creation. The Sikh weaponry for instance, accurately features the katar, the chakram (a sharp, ringlike blade employed by throwing it), and the bag naka, or “tiger’s claw.”

UK-based Climax Studios, the lead designers behind Chronicles: India, emphasized the importance of original historical sources for their world-building. “We took influence from lithographs. Color was a key component. . . we mixed some Sikh-influence into the world,” the game’s art director Glenn Brace blogged. It’s not hard to see why a big game studio like Ubisoft is turning its attention to India. According to Ken Research, the Indian gaming market is predicted to exceed 2.7 billion dollars in revenue by 2018. As others have speculated, the Chronicles series—which includes two other games set in Russia and China, appears to be Ubisoft’s attempt to court these powerful emerging markets.

Designers who are poorly acquainted with Indian culture often take artistic liberties

As Vishal Golia, CEO of Gamiana Digital Entertainment, told Franchise India, emerging markets are important to game publishers. “Foreign giants like EA and Ubisoft have had Indian presence for a long time, helping nurture the local talent. So the ecosystem is building up,” he explained. This coming-of-age story for Indian gaming, however, is not without complications. Designers who are poorly acquainted with Indian culture often take artistic liberties that mix up or flat-out ignore important nuances. The results can easily come off as offensive and even exploitative. Despite its best attempts, Chronicles: India is not above reproach in regards to cultural marginalization. By casting the Sikhs as the antagonists of the story, some argue the game unwittingly plays into pre-existing stereotypes that paint this religious minority as villainous.

According to Gurinder Mann, the director of the Sikh Museum Initiative, “There is a long way to go before a Sikh character with a turban and beard is seen as being the hero. Only then will we see a true representation of Sikhs in the gaming world.” An example from comic books is already showing a way forward. Last year, Silicon Valley executive Supreet Singh Manchanda launched a Kickstarter project called Super Sikh. The goal was to reboot the modern-day superhero. Not with a reimagining of Superman, Ironman, or Spiderman, but with a secret agent who also wears a turban. The message? Looks don’t define a hero—actions do.

Assassin’s Creed Chronicles: India might best be thought of as two steps forward coupled with an unfortunate step backward. Yet, despite its more shallow depiction of Sikhs, the game avoids the common pitfalls of other major franchises, which treat India like exotic wallpaper, according to Yadav. The next step, perhaps, would be a blockbuster game that not only features India, but is created by Indians too. “I understand that the Chronicles series is a low-risk way for Ubisoft to explore new settings [but] I’m happy about it, slightly,” said Yadav. If nothing else, the game comes across as a compelling argument for further exploration of the Indian identity in games—as long, of course, as the question of cultural sensitivity isn’t forgotten.

Hitchcock’s Psycho is getting a horror game homage

Legendary filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) is a classic. Psycho made waves in a magnitude of ways: like killing off its female lead in the shocking first third in the pivotal shower scene, displaying sex and violence interchangeably within a mainstream film, among other, ever-shadowy film motifs. Psycho is a pure symptom of its time—it was one of few films that combatted the conservative Production Code that stifled Hollywood until 1968. Psycho’s influence is eminent on any modern thriller. In fact, it’d be fair to say that it’s hard to see a thriller that wasn’t influenced by Hitchcock’s seminal film. Shockingly, the tense Hitchcockian aesthetic hasn’t been seriously implemented into videogames. At least, not so directly as it has now.

Gates Motel is clear on its inspiration, and it’s not hiding it

The aptly titled Gates Motel is an upcoming homage to the ominous Bates Motel of Psycho, in which main character Norman Bates “resides” with his murderous mother Norma. The in-game Gates Motel is nearly a perfect recreation of Psycho’s name-rhyming lodge (though hopefully, doesn’t turn out as abysmal as Gus Van Sant’s shot-by-shot film remake). The game is bleakly stylized, with dramatic shadows and a fully desaturated environment, harkening back to the early days of black-and-white film, and to the original Psycho’s lack of color itself. Gates Motel is clear on its inspiration, and it’s not hiding it.

Gates Motel’s gameplay is familiar to the survival horror genre (of the well-trodden “collect things for your inventory as the story progresses to survive”), but barely shares semblance with the film’s plot. The game tasks you as a nameless woman trying desperately to survive, her imminent goal to find a telephone to call the police. She only has two enemies: the owner of the motel, and her very own fears. How those fears manifest remains a mystery, as the game currently only has a brief a trailer and description. Though, the rainy, mysterious shadowed world of Gates Motel gets one thing right: it looks perilous. And a Norman-lookalike is probably skulking about somewhere.

Avoid motel showers at all costs and vote for Gates Motel on Steam Greenlight .

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers