Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 119

May 18, 2016

Why esports commentary is so difficult

The job of a sports commentator is to help viewers understand the “why” of what is happening on the field. The reasons behind that 40-yard catch-and-run, the set-up behind that buzzer-beating 3-pointer, the specific actions that led to that corner kick goal—all should be made clear from the insightful and revealing analysis of an experienced commentator.

Since viewers generally understand the basic rules of the sport at hand, commentary for popular sports, at least in the USA, focuses on analytics, helping viewers understand the game as it’s being played at a deeper level. This might be achieved by sharing relevant statistics or commenting on a player’s tendencies in certain situations. Commentators can help viewers become experts in the game even as they watch, leading to a more satisfying spectator experience. It’s typically more engaging for a viewer to watch something they understand with commentators bridging the gaps in their knowledge. This is why esports commentary proves so difficult.

esports commentating suffers this ebb-and-flow of viewership more

Here, in Chicago, I regularly commentate on fighting game tournaments and have hosted and commentated on traditional sports as well through podcasts and live football broadcasts. In my experience, the relative lack of familiarity that a larger viewing audience may have with esports as a whole, means that my job as an esports commentator has often been more difficult than when I call football games. At the highest competitive levels, videogames look very different than they do when played casually among friends, and often have rule sets and eccentricities that a wider audience will not be aware of unless they’re directly involved in the competitive scene.

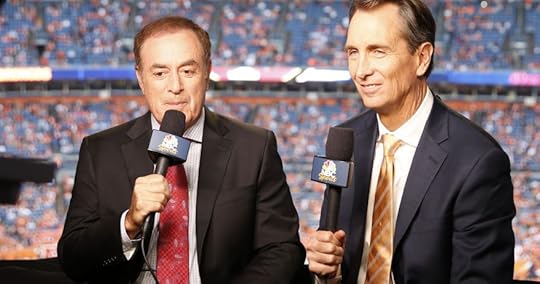

Viewership is growing, yes—Newzoo reports that the number of esports viewers around the world now compares well to the viewership of mid-tier traditional sports like swimming and ice hockey—but the fact remains that esports are relatively new, gaining popularity in only the past 10 years. Most other sports, on the other hand, have had decades if not hundreds of years to make themselves a familiar of the world. In an interview with Forbes, Monday Night Football commentator Mike Tirico explains that, largely due to people being surrounded by sports media both before and after games, commentators are able to let the game action speak for itself most of the time. Their job is then to offer insightful elaboration on top of that. The familiarity the audience has with the sport—its rules, players, and storylines—means that viewers generally just want to hear directly about the on-field play during broadcasts.

It’s true that most of us are easily able to acquire the knowledge necessary to understand sports from a very young age, even at their highest levels of play. In an interview with Vice, noted esports commentator Lauren Scott remarks that simply playing traditional sports in school means that later on, while watching these sports, you already have a certain level of understanding in mind. Recreation league sports, parents, local news; there are plenty of cultural sources that build familiarity with the rules of traditional sports, allowing commentators to assume a certain level of basic knowledge. This doesn’t yet exist for esports. In effect, esports commentators are required to provide exposition of the competitive specifics of the game at hand during the broadcast itself. Only then can they help viewers to understand the reasons behind each in-game action. This might be explaining that a teammate hit their partner in Super Smash Bros. in order to allow them to use their recovery move again, or spelling out the rationale behind what appears to be a seemingly nonsensical weapon selection in Counter-Strike.

Complicating this further is the fact that, in my personal experience, people often tune in and out at any given time during broadcasts. This is true for both traditional sports and esports commentating. However, esports commentating suffers this ebb-and-flow of viewership more due to largely being broadcast on the internet—people often flick through their open tabs, or will choose to only start watching near the end of tournaments or matches to see the highest level of play. Television, however, where most traditional sports are watched, tends to have a more steady audience, generally speaking. What this means for esports commentators is that, in addition to being engaging and likable on camera, they must also explain what is going on at a basic level to build familiarity, as well as offer insight into those actions throughout the entirety of a broadcast, never assuming that a viewer has been watching the broadcast up to that point. For fighting games, commentary becomes even more difficult.

In the world of esports… that warning barely exists

Newer commentators often fall into a trap where they immerse themselves in the game’s mechanics, becoming familiar with frame data, character matchups, and the prominent players in the game’s scene. But since these games move so fast it’s very hard to keep up while spewing all this knowledge. This causes newer commentators to either linger on explaining the intricacies of an action that is no longer relevant, or resigning themselves to simply calling the action as it happens in a play-by-play style. Mike Buetsch, one of the founders of Unrivaled Tournaments (and the company I commentate for), an esports and tournament organizing group local to Chicago, agrees that for fighting game commentary, finding this balance can be tricky. “Everything you just stated can be totally nullified in one button press, it can be overwhelming,” Buetsch says. “It’s like you’re trying to paint this storyline but the players are constantly trying to change what you’ve just stated. It’s why so many commentators fall into one specific style, and have a hard time breaking into a big scene.”

Some of the most prominent fighting game commentators like D1, Yipes, Scar, and Toph have mastered the art of commentary to the point that they can easily keep up with the games they cover. Their speech lingers on covering tactics, strategies, or player tendencies that need to be explained further, but are able to pivot at a moment’s notice should something amazing happen. They are all masters of improvisation with deep knowledge of the games they cover.

This is absolutely necessary in esports because one of their greatest draws—the frequency of upsets and their split-second nature—also makes the job of the commentator much trickier. In my experience covering and watching major sports, comebacks take time. With the notable exceptions of baseball and boxing, a literal last-second comeback cannot happen, given the fact that all plays take time off the clock. That gives commentators a bit of warning, a bit of time to react, even if it’s only a few seconds. In the world of esports, however, that warning barely exists. One blocked shoryuken in Street Fighter can lead to an insane combo that completely turns the tide of the match. When this happens, it’s not a matter of seconds, it’s a matter of frames. A single frame of animation can change the tide of a match, and the simple fact is that it’s the commentator’s job to immediately pivot, improvise, and analyze the specifics of what happened in that single frame. A traditional sports commentator, on the other hand, has the relative luxury of breaking down plays that take longer to develop.

Of course, not every esport is as fast-paced as say, Super Smash Bros. Melee (2001), but even in games like League of Legends (2009) or StarCraft II (2010), strategies must develop and change many times quicker than they do in professional sports. There are no time-outs in esports. Unlike football and basketball, there’s no play clock, no allotted time for strategizing and drawing up plays. Professional gamers are forced to make these shifts on the fly, reacting to their opponent. This is why, even in slower-paced games like StarCraft, statistics like APM (Actions Per Minute) are tracked. A professional player of real-time strategy games is able to perform up to 600 game actions per minute while constantly shifting tactics depending upon the situation. The difficult thing for commentators is that these changes are often very basic strategy shifts, ones that are necessary for a viewer to understand before they will grasp critique of a player’s technique, or color commentary on whether or not the strategy is a good idea. The best commentators pivot with the flow of the game quickly, yes, but they then leverage that pivot as a foundation from which to provide deeper commentary, with the goal of teaching the viewer about the game.

As a tournament organizer, however, Buetsch knows there’s more to it than that. Besides knowledge of the game at hand, Buetsch thinks that the heart of esports commentary lies in the love commentators have for the game and the community at large. “[…] A commentator has to just love the game he or she is watching. It’s very clear when someone who just genuinely loves the game is on mic. They bring a certain energy and their excitement feels so much more genuine.” At its heart, esports commentary is all about growing a game’s scene, growing its community. Despite its frenetic nature, it’s often an intimate experience to commentate on these games. The commentators love them, and are often very close with their co-commentators. Buetsch points out that the best esports commentary teams, like the Super Smash Bros. Melee (2001) duo of Scar & Toph, have amazing chemistry and can give the commentary a natural flow that brings the viewer into the world. They share that love with the viewers in an effort to get them to deepen their love for the game as well.

the commentators are removed from the action somehow

This is why great esports commentators, in comparison to traditional sports commentators, don’t tone down their reactions. They’ll yell during the broadcast and get very animated in their excitement. The point of this is to create a sense of a shared moment, of camaraderie, which helps to glue together the community surrounding a particular game. It’s why it could be said that esports commentators usually approach commentary from an entertainment standpoint rather than the drier, journalistic tone favored by traditional sports. As the community grows and becomes more profitable, commentary in the esports scene may become more regimented, but as it stands right now, anybody reading this could likely find a weekly streamed esports tournament in their area and ask to commentate. It’s open, which intrinsically leads to a more unpredictable and lively commentary style.

The famous “WOMBO COMBO!!!!” video might be the best example of this phenomenon. It’s a slice of what makes esports commentary so special. The commentators are not just fans of the game, of the esport, but commentate as fans as well. This team combo gets the commentators (HomeMadeWaffles, Phil, and Mango) excited to the point of yelling (and vulgarity), which naturally gets the crowd and viewers excited too. Compare that with the call for one of the most amazing athletic displays ever seen. Though the commentary duo of Cris Collinsworth and Al Michaels sound excited about Odell Beckham’s phenomenal catch, there is a distinct lack of emotion in their voices. The cadence of their voices, the analytical nature of the commentary, it all implies that the commentators are removed from the action somehow. They’re not showing their reaction to the amazing catch, they’re telling us how impressed they are by it. There’s a key difference.

It’s common to see this style of commentary underscoring amazing moments in traditional sports. With some notable exceptions, pro sports commentary is often clinical and holds absolute control over any emotion, despite the blood, sweat, and tears shed by the athletes. In a piece for SB Nation criticizing sports media, Spencer Hall argues that this is because “being bland and featureless is very marketable.” Given the lucrative amount of money tied up in product sponsorships for each and every one of the major sports leagues in America, it becomes a good business decision for commentators to be low-key simply because that style carries a very low risk of alienating anybody the league is trying to sell products to. John Strong, a Major League Soccer commentator for NBC puts it a bit more tactfully in an interview for Work In Sports, saying that the best commentators don’t “go nuts with catchphrases” or show off their personality, they just keep it simple and talk about the game at hand.

By the same token, while esports commentators may be less polished, may make more mistakes, and may, at the end of the day, be talking about the 1s and 0s produced by a piece of software, their personalities always come through. The commentary is somehow more human. And as the esports community grows in viewership, broadcasts will need to remember that these personalities are a big reason why the community has become so large, so quickly. In the next few years, esports will serve as regular programming on major networks like TBS. And ESPN has already launched a separate vertical to cover competitive gaming. Because of this investment in the future of esports, sponsorship deals with major esports leagues should become more lucrative, and viewership looks to continue its steady rise. Esports and its audience will grow, and in growing, change. And with that change comes a number of external pressures that will face the commentary community; the people expected to communicate esports to an increasingly wider audience. Given these pressures, the human touch present in current esports commentary risks being lost, at least at the highest levels of competition. While perhaps necessary, it would be a shame.

The post Why esports commentary is so difficult appeared first on Kill Screen.

NES hack brings your old Nintendo online, complete with Twitter

Despite being over 30-years-old, and therefore predating public internet access, it turns out that the original Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) has actually been capable of connecting to the internet the whole time. All it takes is a “modem” and a little bit of hacking, courtesy of Femicom Museum founder and serial videogame tinkerer Rachel Simone Weil.

Dubbed ConnectedNes, Weil’s hack brings the NES online in three easy steps. First, it takes a Particle Photon Wifi development kit and hacks it together with bits of a NES controller, then plugs it into a standard NES controller port. Because the kit (which Weil has nicknamed a modem) transfers data using the same binary bits system as a controller, the machine can then read its output as if it were a normal NES controller.

Second, a server running on a separate device parses through services such as Twitter for tweets containing certain keywords and then wirelessly transfers them over to the modem. Third, the data is run through a custom ROM—or game file—that allows the machine to process and display the information on screen.

Happy to announce ConnectedNES, a ~super-cute~ WiFi-enabled NES + 8-bit twitter client. https://t.co/vhQ48Cnyc1 pic.twitter.com/eWjj0SkQKu

— Rachel Simone Weil (@partytimeHXLNT) May 9, 2016

The result is a 1983 game console capable of reading tweets just as well as a smartphone, albeit with classic 8-bit flair instead of trendy web 2.0 design. Perhaps more interestingly, it can then incorporate online data into standard NES games. All you need is a custom cartridge with one of Weil’s ROMs on it.

a new Twitter notification every time you step on a Goomba

So far, Weil’s built two ROMs for the device. The first, also called ConnectedNes, simply allows the machine to display tweets, complete with a colorful pixel art style and balloons floating by in the background. The second, Social Media Bros, is a hack of the original Super Mario Bros. (1985) that displays a new Twitter notification every time you step on a Goomba. Currently, the device is limited to Twitter, but Weil hopes to expand it to include other services in the future and turn it into “a true platform that anyone can use!”

For those looking to bring their NES into the information age, you can find the code behind the device over on Weil’s Github. As for the hardware, Weil is planning to post detailed tutorials on how to build it soon, but a simple description of the process is currently available over on her site. For those without a NES, Weil’s ROMs will work in an emulator, though she doubts if the same is true for the modem, as it would have to be connected to a PC using a USB adapter.

To learn more, visit Weil’s site.

h/t Motherboard

The post NES hack brings your old Nintendo online, complete with Twitter appeared first on Kill Screen.

DOOM is another act of rebellion

In the Abrahamic religions—and the texts that have grown out of them—Satan is a fallen angel, cast out of heaven for daring to rebel against God. Though his name is synonymous with fear and evil, it’s Satan’s tireless, implacable need to oppose everything God wills that truly characterizes him. He’s a catch-all for the misfortune of heroes and nations. He’s a scoundrel who’s always up to overturn the plans of the master of the universe.

Back in 1993, id Software’s DOOM was another act of rebellion. Created by a small team of industry upstarts, DOOM (like many contemporary metal bands) latched onto Satanic iconography to mark itself as dangerous—a raised middle finger to the authoritarian mainstream of the morally panicked religious right then dominating Western culture and politics. DOOM was meant to feel threatening in both imagery and business. Filled with inverted crosses and goat-headed sigils, splashed with gore, its free “shareware” levels spread like wildfire through the young internet.

something clicks into place

Now, more than 20 years later, id has returned to DOOM, reimagining its best-loved creation with a game called, fittingly, DOOM. It’s a difficult proposition not just because nostalgia can be so unkind to revisits, but because, more than anything else, the first DOOM is defined so largely by its attempt to buck tradition—something that a backward-looking reboot can’t replicate.

The first moments of 2016’s DOOM make deliberate reference to the series’ past, presenting a worrying first impression. A man’s muscular arms tear free of iron shackles and grab a laser pistol. He blasts through crowds of skeletal zombies as if his feet are freshly sharpened skates and the corridors are newly polished ice. It all feels familiar and, at first, too much so. But something clicks into place once the player has stepped into the bomb suit and ski helmet of the Doom Marine’s armor and located her shotgun. The weapon punches into the leathery chest of a monster, shoving them backward and leaving them reeling in place, glowing a tantalizing blue. Push a button and the Marine’s hands thrust out, wrenching the creature’s neck around or punching straight through its sternum so it explodes in a shower of viscera and health-restoring orbs. By the time a chainsaw is found and the player has sawed through the protesting arms of a demon (that bursts with ammunition pick-ups), a rhythm is established that buoys the entire game.

The original DOOM is a game of speed. It demands quick thinking in navigating the Marine around the fireballs and gnashing teeth of its enemies. Choosing the right weapon for the job; prioritizing which demons to kill when an arena is full with a variety of different types; balancing the need for ammunition and health pick-ups—all of it requires on-the-fly tactical thinking of a kind that’s largely vanished from mainstream shooters.

If the 2016 DOOM did nothing more than replicate this style of play with improved audiovisual fidelity, it would be a hollow effort—a fresh coat of paint applied to an already sturdy house. Instead, it takes the fundamental joys of the original DOOM’s projectile dodging and implements subtle tweaks that, with time, create something novel out of familiar parts. Fighting through waves of demons still requires quick footwork, but the ability to smash essential health and ammo from the wavering almost-corpses of the monsters introduces an important new element. Firing off rockets from a distance must eventually be combined with leaps into boiling masses of growling beasts. The player has to be ready, when the screen or ammo count flash a dangerous red, to wade into the thick of danger to smack potentially life-saving items out of deadly piñatas.

It knows its Halloween store gore and demons are no longer shocking

The immediate feedback of these up-close kills is resounding. The controller rumbles along with the crunch of bone and the wet thud of organs, the Marine and player’s hands achieving gruesome symbiosis as a physical reward on par with the visual thrill of a rapidly filling health bar. The pace of the combat—constant changes in proximity mimicking a hyperactive boxing match—is unrelenting. All the while nü-metal guitars chug and squeal, their too-clean production propelling the action with a crushed Ritalin fervor and greasy-haired charm that easily matches the 1993 DOOM’s MIDI noodling.

DOOM not only does a fantastic job revising its source material’s combat, but also its blend of sci-fi tech and demonic horror. The Union Aerospace Corporation (whose Martian base serves as setting) is depicted as a cult-like corporation, its employees literally mining hell for resources while ritually prostrating themselves before powerful CEOs and senior researchers. The UAC’s enormous authority over its employees is a satire of not just modern day corporate power—one hologram proudly advertises the UAC’s work in “weaponizing demons for a brighter tomorrow” while an informational log urges new employees to sign up for team-bonding pentagram tattoos—but also the power structures in the Christian church tradition used as the basis of its depiction of hell. (It’s a troublingly unexamined echo of Eve and the original sin that, of the few characters who make up the cast, it’s the lone woman who is intoxicated enough by hell’s power that she facilitates the demonic invasion.)

Opposed to the UAC’s hell-enabling mission is the Doom Marine—a primal and anarchic force. He’s a violent monster but an agent, ultimately, of good. Though he never speaks, the Marine subverts both the rigid structures of a massive corporation and the player’s expectation of the personality a silent character can possess. Through his arms alone, the Marine is responsible for some of the best humor of the game. When he comes across the floating robots who provide weapon upgrades, the Marine yanks it from the air, takes what he needs, and smacks it to the side in a beautifully animated bit of recurring slapstick. When tasked with shutting down the transfer of a renewable energy resource, he smashes apart terminals rather than carry out the complicated work of properly stopping the process and saving the incredible technology.

Id Software has expended plenty of effort to justify a return to the narrative and play style of the 1993 DOOM. The spirit of rebellion that made that game such a bold statement is impossible to replicate—it’s too much to ask that a reimagining match the unquantifiable chutzpah of its source material. All the same, any iteration of DOOM will always be held in comparison to what’s come before. Rather than attempt to emulate design that was impactful because it was released in a different, bygone time, the new DOOM understands that there are other ways to capture the appropriate spirit. It knows its Halloween store gore and demons are no longer shocking. It understands that this culture has changed, and that attempts to repeat prior tricks will only lead to bland pastiche. The 2016 DOOM’s rebellion is smaller than its predecessor, but still impressive: it is unabashedly itself. It’s a game with confidence in the worth of revisiting its history and an earnest belief that doing so can result in much more than an empty exercise in nostalgia.

///

The post DOOM is another act of rebellion appeared first on Kill Screen.

May 17, 2016

Bloc by Bloc aims to be the board game for modern revolution

The Earth has seen her fair share of revolutions in the last decade. We have watched them on our televisions, followed them on Twitter, witnessed them both in our hometowns and impossibly far away. In such a tumultuous period they often seem inescapable, but unless they were brought directly to your door, they are also usually preserved pristinely behind a computer screen. The reality of the action has a hard time crossing the border between activists on the street and spectators at home. Bloc by Bloc: The Insurrection Game, by Out of Order Games and now on Kickstarter—described as “semi-cooperative strategy inspired by 21st century urban rebellion”—seeks to close this gap with, of all things, a board game.

a counterpoint for the modern revolutionary

The title brings to mind Eastern Europe, but Out of Order has instead taken their inspiration from more recent insurrections: Cairo, Istanbul, London, Oakland, Athens. The Kickstarter trailer shows footage of these uprisings interspersed with figures moving game pieces, bandannas over their faces, hoodies up. It’s clear what this game intends to be: a counterpoint for the modern revolutionary.

Bloc by Bloc gives you eight nights to liberate the city before it is retaken. Every player has a different goal that they have to approach independently, but the completion of that goal is the extent that any one person can “win.” If the most important districts of the city have been occupied, the uprising is successful: if they are not, the sun rises, the military arrives, and the bloc is forgotten.

Maybe 10 years ago a board game about contemporary revolution would have been unthinkable. Though, we are fine with playing war with Risk (1959) and Battleship (1967); the scenarios they bring to mind are far enough away to give comfortable distance. Bloc by Bloc shows none of this hesitation, neither seeking to trivialize the violence that is going on right now or to claim itself as some grand representation of it. The eponymous “blocs” are both game pieces and city tiles, but more importantly, they are nameless. They have no geography, no identifier, no agenda. They could be Budapest in 1956 just as easily as they could be Ferguson in 2014. It may be a few hours of fun over beers with friends, but it’s also an exercise in empathy.

Back Bloc by Bloc: The Insurrection Game on Kickstarter before May 18.

The post Bloc by Bloc aims to be the board game for modern revolution appeared first on Kill Screen.

Celebrate International Month of Creative Coding by taking online courses

Everything we know and love virtually is the source of meticulous coding. Coding is the backbone of videogames. Coding is in the DNA of the websites we visit daily. In fact, coding can be the reason why some of our favorite creative endeavors exist at all. Coding all too often makes the impossible possible. And that’s why the for-profit online course provider Kadenze has officially dubbed May as the “International Month of Creative Coding.” But what makes coding creative?

Coding makes the impossible possible

Creative coding is the primary goal of Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Mathematics education (STEAM). Coding’s a marriage of four of those fields, whereas the outlier, art, makes for trickier integration. By urging coders to think to innovatively and work towards a more artistic goal rather than a strictly functional one, creative coding is born.

Kadenze has a number of creative code-focused online courses for their special themed month. Videogames aren’t ignored in this. In the course “Physics-Based Sound Synthesis in Games and Interactive Systems,” the lessons of replicating vibrational real-world sound within a digital space is exemplified, such as learning how to craft realistic echos. As Professor Perry R. Cook of Princeton University explains in a video introducing the course, many of the sounds we hear in the games we enjoy are often pre-recorded in real life, manipulated and processed for a digital world.

In another, a course is dedicated to introducing coders to viewing the internet as a platform for art beyond a visual standpoint, and seeing its social, physical, interactive, and sonic potential. On a music-focused end, a course caters to “machine learning,” on creating a multitude of interactive musical projects. The common thread through all of them is that thinking outside the box, even in coding, is key to a unique project.

Visit Kadenze’s blog for more creative code-oriented courses, interviews, projects, and more.

The post Celebrate International Month of Creative Coding by taking online courses appeared first on Kill Screen.

Erotica Robotica proves sex with robots is tricky

In this fantastical world of booming technological advances in robotics, you’d probably be lying if you said you’ve never thought about sex with robots. After all, the topic has been almost unavoidable, cropping up in the news thanks to very possibly sex-craved innovators like this man, who made his personal robot look eerily like Scarlett Johansson, and the many people—including myself—who swooned over the AI who spouts post-modern poetry.

Enter Erotica Robotica, a game where two players must work together to sexually pleasure a robot named SAMM-69, to satiate that, uh, curiosity. And SAMM-69, the genderless robot clothed in a pink leopard blanket and nothing else, awaits eagerly for someone to figure out the mechanisms of its very complicated body.

Who said having sex with robots was easy?

At its core, Erotica Robotica, as developed by TeamBONE, is a puzzle game. Modeled similarly to the game Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes (2015), one player must download and read the User Manual specific to SAMM-69, which explains how to solve the various puzzles presented in the game in order to pleasure the robot. Without looking at the computer screen, the player with the User Manual must then instruct the other player on how to navigate each puzzle, and the puzzles are actually pretty tricky.

One puzzle, for example, is a 10×10 grid containing two different colored dots spread in two different squares. Like a maze, the goal is to get both dots in the same square on the grid by moving one of the dots through a specific path of squares on the grid. But if you move a dot on a wrong square, SAMM-69 lets out a cry of pain.

As such, the players have to be clear in their descriptions of coordinates, their movements, and anything else helpful in understanding what the player pleasuring SAMM-69 is seeing on the computer screen, lest the robot is denied the pleasure it so desperately craves. Often, this results in both players screaming at each other in frustration and quite a bit of name-calling.

If the game sounds confusing, good: it’s supposed to be. Who said having sex with robots was easy?

You can play Erotica Robotica over on itch.io.

The post Erotica Robotica proves sex with robots is tricky appeared first on Kill Screen.

Negotiator, a game about dealing with terrorism and online harassment

If you’ve watched enough movies or TV you would have seen a hostage situation. And almost every hostage situation involves a negotiator. Someone who is there to try and defuse the situation, hopefully with words instead of bullets. Negotiator from 4PM Games is going to let you step into the shoes of one of those hostage negotiators. And it won’t be easy. One mistake and you could be the cause of someone losing their life.

“I have always wanted to recreate the feeling of static tension, present in hostage situations,” explained Bojan Brbora, founder of 4PM Games and creator of Negotiator. “I wanted to mix a few genres to create a seamless, thriller experience.”

“Feeling your hands sweat when you hear the gunshot on the other end of the phone”

Social media plays a big part in the narrative of Negotiator. Jonathan Martell is part of a hostage situation in South America that fails. That failure leads to the death of a famous celebrity. After getting discharged from the military, Martell arrives home in London to find that the internet is angry at him. They even have a hashtag, #killerofinnocents. This hate spreads beyond just him and his sister is harassed by those upset over John’s mistakes. It’s a story that echoes some of the same events and harassment that currently happens online.

The story of Negotiator has been bouncing around the head of Brbora for a few years. Once he started actually developing those ideas the world “went to hell.” The subjects that Negotiator deals with—war, terrorism, and even harassment—have all become increasingly common and talked about subjects. Brbora is aware of this, but still thinks the story he has come up with is worth telling. “These are sensitive subjects, but if we are going to do something different, something truly relevant, we can’t shy away from such things,” he said. But Brbora also feels that the story of Negotiator isn’t really about terrorism or war. Instead, Brbora is more interested in different points of view and what influences those views. “The main [influencer] being news and social media, how they affect our real world actions and the extreme situations it takes to break free from that influence to do the right thing.”

Most of the narrative of Negotiator takes place over a day in London. And throughout this narrative you will be able change the course of events. For example, whether or not you let a person die can alter the story and the ending you get. Brbora wanted to create a high sense of tension in the player by allowing them to make mistakes a key part in accomplishing this. “Feeling your hands sweat when you hear the gunshot on the other end of the phone. There are several key points where people in your group can die, similar to what Telltale does. The story always moves on, with slightly different variables.”

And while Brobra has researched real life hostage negotiators he wanted to make sure that people understand that this isn’t a simulator or training program. “This is primarily meant to engage and thrill, with the boring bits cut out.”

Currently, 4PM Games is running a Kickstarter to help secure funding for the game. The studio is small and made up of different freelancers who come together to make something. “This is a very unique and special project for us, one that we need loads of support for. This is why we have launched a kickstarter, in order to show publishers and financiers that this is a worthwhile venture.”

Negotiator will be released on Windows via Steam sometime next year. It will also be released on Oculus and Vive. You can support the game on Kickstarter and Steam Greenlight. You can also check out other titles by 4PM Games on the studio’s website.

The post Negotiator, a game about dealing with terrorism and online harassment appeared first on Kill Screen.

The English melancholia of Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture

This article is part of our lead-up to Kill Screen Festival where Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture artist Alex Grahame will be speaking.

///

“These are the dark November days when the English hang themselves!” – Voltaire

///

The English are known for a number of bred-in-the-bone traits but chief among them is a certain melancholia. There is nothing uniquely English about being a bit sad but history has latched it to us as part of our national character. Perhaps it is our artists who are to blame for this. John Dowland, the Elizabethan bard, is remembered for his motto: “Semper Dowland, semper dolens” (“always Dowland, always miserable”). Centuries later, Blur and Gorillaz frontman Damon Albarn—who calls himself “an English melancholic”—would echo Dowland’s sentiment, especially with song titles like “On Melancholy Hill.” As Jules Evans notes, Albarn is only one of many modern English musicians to hit upon that pensive chord, along with Amy Winehouse, Morrissey, and Nick Drake. And surely it’s no coincidence that goth rock started with morose English bands like Bauhaus, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and The Cure.

overlooking the villages below as one would a burial ground

Then there’s the so-called “graveyard poets” of the 18th century: Englishmen who wrote gloomily about death, coffins, bones, and our eternal rot in the ground. Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751), among others, did the job of kneading this national melancholia into an association with the English countryside. “To Continental observers hypochondria was notoriously The English Malady before 1733 when Dr. George Cheyne published his book of that title,” writes George Sherburne and Donald F. Bond in The Literary History of England: Vol 3 (1959), adding that it was during the 18th century that “the English acquired an international reputation for suicide.” The fashionable artistic image of the time became one of an Englishman sat atop a knoll, skull held in one hand, the other penning his wizened thoughts on mortality while overlooking the villages below as one would a burial ground.

That poetic image dominates the tone of last year’s Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. Made by Brighton-based studio The Chinese Room, it has players explore a small English village in the wake of an apocalyptic event that has caused all the residents to suddenly vanish. Players discover what happened to these people by chasing the traces of human life that remain in the idyllic environment. Manifesting as orbs and particles of light, these theatrical remnants reveal the various tales of loss and grief that the villagers were in the throes of when they were stricken. But these fading presences are fragmented and so a greater well for players to draw from in their investigation are the physical details left of each character’s struggles inside houses, and across the many streets and fields. It’s there that players can see the work of Alex Grahame, one of only a handful of artists who worked on Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, and who will be speaking about how she designed loneliness in this role at Kill Screen Festival on June 4th.

Grahame had the hefty job of establishing the somber tone that runs throughout the whole game while working on Barbara Foster’s house. It’s one of the first buildings players can enter and be presented with a character scene inside—a small flashback related to a specific character and location played out in light particles. This one, it turns out, is particularly harrowing, and Grahame had to make sure it both resonated and intrigued its audience. “This was a difficult task as the scene that plays out is not of the character who owns the house,” Grahame said. “It was important to visualize the owner (Barbara Foster) and use her background to juxtapose with the scene of a woman realizing her children have died.” Grahame created Barbara Foster’s personality by looking to classic British cultural touchstones such as the TV series Keeping Up Appearances (1990-1995), and its snobbish middle-class homemaker Hyacinth Bucket. As such, Barbara Foster became a conservative character in her 60s or 70s, which is reflected in the interior decoration. “Floral patterns cover the walls, the sofas and pictures of flowers and vases are all over the warm pastel colored environment,” Grahame said. This is then contrasted with bloody tissues that lie around the living room, where the character scene plays out, which were used to “suggest that something is wrong.” It’s not until the scene leads players upstairs that they can infer that the children must have died.

Barbara Foster’s house is representative of the balance that Grahame and the rest of the artists working on Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture had to consistently aim to hit. On one side of this balance was an effort to create a “classically beautiful aesthetic and idyllic environment” like those iconic landscapes painted by English Romantics in the 18th and 19th centuries. Think sun-drenched horizons and fields of windswept buttercups, perhaps the green leaves of a weeping willow drooping into a shimmering summer lake while families picnic on the nearby grass. Alongside this there was a need to strive for authenticity and plausibility to ground the characters and the game’s tragic narrative. “It was a rare and exciting opportunity for a games artist to include classically unique British moments and props into the game such as British architecture, foliage, vehicles, phone boxes, post boxes, graffiti, and other instantly recognizably British icons,” Grahame said.

“since her death, his house is in disarray”

To inform her efforts to hit that balance between these two conflicting sides—the romantic and the real—Grahame looked to classic English landscape painter J. M. W. Turner and German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich. “I like to look at artists that create emotion through their work in less explicit ways to understand how to create atmosphere and tone through subtlety,” Grahame said. “Turner and Friedrich […] both use light and color to create emotion through their work with strong contrast.” Following that lead, Grahame looked to capture the atmosphere of a location through color and environmental contrast, and the scene that exemplifies this for her involves the character Frank Appleton. “Through the game we discover that Frank’s wife died months ago, and since her death, his house is in disarray,” Grahame said. “The dirty, unkept house visualizes Frank’s dependency and his sadness for losing his wife. The contrast and realization of this comes only from the room she died in, which has been kept immaculate, untouched, and preserved. It demonstrates the depth of these characters. There’s an appreciation to understand and empathize, which makes their stories come alive.”

Thunderstorm with the Death of Amelia, William Williams, 1784

Frank Appleton is almost an archetype of British melancholia. He’s a stern farmer and family man turned inside out by the death of his wife. He has anger issues, but his attacks are mostly directed at himself: an anger at his incapability to deal with his personal loss. We last see him stood upon a hill overlooking his farmlands as bombs are dropped on them, ready to face death and rejoin his wife. It’s as if a realization of William Williams’ 1784 painting Thunderstorm with the Death of Amelia (in which two lovers meet at a hilltop for the woman to be struck dead by lightning), or the opening stanza of Gray’s Elegy, which goes:

“The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o’er the lea,

The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.”

But where Gray formed his sad characters in his own mind flowed through ink on the page, Grahame emphasizes that Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture was able to so superbly capture loneliness due to the strength of of the team behind it. “It is the whole experience that is a tool of artistic expression,” she said, “from the high level narrative themes, to the visually detailed worlds and the emotive soundtrack. Working collaboratively creates a cohesive and authentic final experience that can convey the story from different perspectives.” Working with a flat hierarchy and allowing everyone on the team to chip in with their unique perspective is what Grahame said encouraged communication and creativity in the game’s production. It succeeds, she said, as a work stitched together by multiple artistic visions. Which is appropriate given that Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture doesn’t capture the melancholy of just one person, but many, all of their stories woven into an environment marked by solitary yet connected deaths. It is a tapestry of the melancholy that runs through the English character and the varying artworks the nation has used to express it to the world over the years.

///

To learn more about the Kill Screen Festival and register, visit the website.

The post The English melancholia of Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture appeared first on Kill Screen.

Future Unfolding’s team wants to randomly generate hand-designed puzzles

In his recent book Spelunky, Derek Yu writes about the process of designing his 2008 (and 2012 remake) game of the same name, and often refers to the difficulties introduced by the decision to generate levels randomly. He describes trying to make sure that every time a level is generated, it is new, challenging, and solvable: “The game’s first priority,” he says, “is to make sure that there is a path from the entrance to the exit that is traversable without the use of bombs, rope, or other special equipment.”

Spelunky generates its levels with templates for rooms and patterns for smaller pieces of those rooms, and Yu emphasizes that his role is to control the chaos in this randomness. “All I could do was create the building blocks of the world and set them in motion—what came out could be as surprising and indifferent to me as it was to the players,” he says. Traversing the levels of Spelunky becomes about reading the systems at play in any given moment and using what you’ve got in your inventory to solve the problems ahead of you.

this system introduces variety

A recent blog post from the team behind the upcoming Future Unfolding describes their approach to random generation very differently. The first game they cite as an inspiration is The Witness, a game full of meticulously hand-designed puzzles with only one solution each. In order to combine the precision of hand-design with the novelty afforded by random generation, they designed their own level editor for Future Unfolding that allows them to swap animals with other animals or obstacles with other obstacles: “For example – an opening has low-height vegetation which can be either flowers, small bushes or grass. A path has an enemy, it could be a wolf or a snake.”

But this applies to puzzles too—objects can be designated as relevant to puzzles, and these “artifacts” can be swapped out with each other too. The result is “puzzle scenes with… solutions [that depend] on which objects are randomly chosen for you.” Future Unfolding still has a lot of randomness, with areas in different arrangements and locations, but this system introduces variety, and ensures that while each piece of the game has been designed only once, it might be experienced in different ways, maybe not even recognizable if you play through the game more than once.

Derek Yu designed Spelunky the way it is partly because he was interested in a game that challenges the player without becoming rote—he says “I dislike boss battles that follow a rigid pattern… Once the puzzle is solved, it becomes a purely repetitive exercise.” As in The Witness, solving puzzles that have only one solution can be intensely satisfying, but these don’t tend to invite repetition or exploration on the part of the player. If Future Unfolding succeeds in combining the hand-designed single solution with the randomly-generated novel space, maybe it can get away with having the best of both worlds.

Read the full blog post about Future Unfolding’s procedural generation over on Spaces of Play’s website.

The post Future Unfolding’s team wants to randomly generate hand-designed puzzles appeared first on Kill Screen.

Glitchspace is a part-time shift of fixing bugs

No videogame is perfect. Somewhere lurking in the seams of polygonal landscapes lives the glitch —a graphical hiccup that could lead to characters not loading properly, items malfunctioning, or walls losing their solid form. However, in recent years the glitch has transcended its status as a technical bug to become a populist generative art tool. For example, Assassin’s Creed Unity’s (2014) walking nightmares wouldn’t have existed without errors to prompt them. Someone found an exploit in Dark Souls (2011) that lets you skip most of the game and break speedrun records. And even older videogames have found new life through gorgeous glitches that resituate retro charm for new audiences. In fact, glitches have become so popular that games like Memory of a Broken Dimension have adopted glitch aesthetics whole cloth and applied them to environments meant to bewilder players with intentionally fractured spaces. Unlike glitch aesthetics, real glitches are signifiers that something is broken or incomplete in a system’s programming. So while sometimes players might think glitches look funny or beautiful, they can be real headaches for game makers.

In the new game Glitchspace from Dundee-based studio Space Budgie, it’s your job to relieve those headaches—you’re a glitch repairperson. You walk around on white floating cube islands, clicking on red blocks to alter their code, reshaping them, moving them, or changing their function to build pathways and unblock passages to get from point A to B. It’s not a glamorous job and Glitchspace is not a glamorous game. For better or worse, there are almost no notable glitches or glitch aesthetics to gawk at. There’s no story setup or pretense to imply motivation for your role either; fixing is what you’re there to do, and that is all.

If you’re like me and have very little experience with writing code, Glitchspace is all on-the-job training. Say you come to a dead end, but when you look up some five stories high, there’s an opening. It’s the only way forward and your meager jumping abilities won’t get you anywhere close. Luckily the floor is a red block, which means you can manipulate it. When you right-click on a red block, a two-dimensional word-web interface pops up, allowing you to summon and connect nodes that change the function of the blocks. In this case, you could pull in an “Apply Force” node (more bouncy castle than Jedi), along with a few others to register the proper syntax, and assuming you set the numbers high enough, the red block will spring you up to the opening in the wall. What was once broken has now been fixed.

In concept, Glitchspace has a lot in common with music puzzler FRACT OSC (2014). Both games situate you in an abstract world within a computerized machine, and both have at least a partial goal of sparking real world interest in its subject matter beyond the game. In Glitchspace, that’s writing code. In FRACT it’s creating synthesizer music. However, where FRACT’s puzzle design had little to do with actually teaching players how to make music, I left Glitchspace knowing a smidgen more about programming than when I entered. Granted, most of what you can do in Glitchspace stays within the realm of basic circuitry (flip this switch to send electricity to the light bulb kind of stuff), but seeing the real language and making those connections by hand is more powerful and convincing than simply reading them or having an implied understanding.

I left Glitchspace knowing a smidgen more about programming

But even as a learning environment, Glitchspace has its limits. It offers an experiential learning half step; providing hands-on activities, but little in the way of self-directed exploration. Though a sandbox level creation mode is planned, it’s not present at launch, which leaves the “Story” mode surprisingly lacking in playfulness. It doesn’t help that the design of Glitchspace’s world is bare bones and uninspiring (think Portal with placeholder assets). You’ll spend the majority of your time in Glitchspace traversing white tiled walls and floors, hacking into red rectangles, and spawning grey fodder cubes. There’s something very “corporate training session” to the whole endeavor that made me want to get most puzzles over with as soon as I could.

Glitchspace’s claim to fame is its node interface, which is notably accessible for coding novices, but gives way to encumbrance and tedium by the end. Once I got the hang of moving the red blocks around on various axes, I felt empowered to take on whatever challenge the game threw at me next. I’d simply eyeball which point in the grid the block needed to be moved and plugged in the corresponding components. Easy enough. But when you don’t know exactly which nodes to implement to, say, repurpose one block as button that turns another invisible, the trial and error becomes an embedded menu hunt for whichever nodes are even compatible with one another. Not to mention that I still don’t know why nodes like “Rotate” show up in multiple places but seem to have different uses. There’s elegance and satisfaction to executing simple manipulations that gets lost in translation as more complex logic systems are introduced.

There is a sweet spot around the midpoint of Glitchspace after you learn “Apply Force” and you get a string of puzzles that do allow you to play around a bit—it helps when you can fling yourself around like a ping-pong ball. But the endgame puzzles come with red cubes that are preloaded with so much node-clutter, I found myself looking for glitches just to get around it all. It’s one thing to allow for multiple solutions for puzzles, but another to imply that there’s a right answer and let players sneak by with some other answer that probably wasn’t supposed to work. I went from being a glitch repairperson to leaving horrible messes of rubberized cubes at 20-degree angles in my wake, simply doing whatever I could to get to pass the test with no concern for the theoretical next player.

I started out by saying in Glitchspace you’re a glitch repairperson, but that role is less a character to embody than simply a list of tasks. A couple hours into Glitchspace, I hoped for a break in the progression and the chance to explore my newly acquired skills, but instead the complexity is continuously layered on top of itself until the game ends. And it ends with you literally walking back up to the title screen, ready to clock in for another shift. I think I’ll take my lunch break instead.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Glitchspace is a part-time shift of fixing bugs appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers