Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 116

May 24, 2016

Before gets NSFW in its latest update (but it’s still beautiful as heck)

Before is a new spin on the survival game from Rust developer Facepunch Studios where, rather than controlling a single character, players must lead a whole tribe of cave people to survive in an intimidating post-Ice Age world. Up until now, we’ve had a few opportunities to gawk at the game’s naturalistic vistas and see early glimpses of how the player’s tribespeople interact with both the environment and each other. But thanks to a new update over on Before’s blog, we now have a better idea of the specifics on how they’ll live and fight in this still young society.

The game starts by allowing players to customize their tribe members, adding a touch of personal connection to the group. Players can choose between different beards, hairstyles, hair colors, and clothing options, not unlike other games of the same type, but what’s notable here is that everyone is anatomically correct. Certain clothing options do cover these areas, but shame is by no needs mandated. “This is a Facepunch game after all,” write the developers, referencing similar features in Rust.

everyone is anatomically correct

The team is still in the process of fleshing out how your tribe will both hunt and defend itself, but much of it seems to rely on the intuition of the cave people themselves as opposed to direct player control. “We’re letting the AI deal with things like picking which weapon to use, and what type of attack they should perform,” the post explains, with special attention having been paid to improving ranged weapons like bows. The world is no less threatening, however, as larger animals like bears will be able to wound multiple tribe members in a single swipe.

Because the game is as much social simulation as it is struggle to stay alive, the team has also added a traits system to the cave people. These will boost or hamper certain skills, but can also give certain tribespeople specific behaviors. As of now, the team is toying with the idea of giving each cave person two positive traits, and one negative one, “the idea being that everyone has a flaw and it’s those quirks in personality that will make our social simulation a little more interesting.”

Currently, the team is working towards creating another build of the game to release among themselves for further testing around June, with more updates to follow soon after. To see more, visit Before‘s website.

The post Before gets NSFW in its latest update (but it’s still beautiful as heck) appeared first on Kill Screen.

Second Life is the newest front in America’s electoral ugliness

There is officially nowhere you can go to hide from the interminable agony that is this election, especially online.

To wit: Cory Doctorow, by way of Motherboard, reports that tensions between Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump loyalists have boiled over on Second Life (2003). More to the point, Trump supporters have attacked Sanders HQ, which is apparently a not-that-socialist roman fort. “Peace was shattered,” Doctorow writes, “when Second Life‘s Donald Trump supporters laid siege to the building, firing virtual guns whose rounds exploded into swastika flags at Sanders central.”

the toxic discourse around the edges of this campaign cannot be avoided

That sentence features more revelations than a week of CNN coverage, so let’s unpack it. Yes, Second Life is still a thing. Yes, some Sanders and Trump supporters appear to be on Second Life. (No, before you start tweeting, these are not all—or even most—supporters of the candidates.) This is largely consistent with Second Life’s initial premise of being a player-driven experience. “Residents can build anything they can imagine,” Robert D. Hof wrote in a 2006 Businessweek feature on the game, “from notary services to candles that burn down to pools of wax.” That is still true, and the people have chosen to wage campaign warfare.

(There are, presumably, some Clinton supporters on Second Life as well, though comedic form dictates that this is the point in the article where I point out that Hillary is actually big on MySpace or Geocities. Yuck yuck.)

(Image: SLer Macaria Wind)

Second Life is not what it once was. At this point, its most interesting spaces are deserted—a digital form of ruins porn. The existence of a Trump-Sanders war on Second Life doesn’t really change any of these dynamics, but it is interesting nonetheless. Above all else, it is a reminder that the toxic discourse around the edges (and increasingly at the center) of this campaign cannot be avoided. It is especially unavoidable online. Strange spaces that you carve out for your interests will be taken over and filled with strife. In Second Life, supposed Trump supporters will use their guns to make a swastika flag fly over Sanders HQ. It’s a fascinating episode on its own, but perhaps more effective as a metaphor for online worlds and the election that is still months from being over.

The post Second Life is the newest front in America’s electoral ugliness appeared first on Kill Screen.

The irresistible appeal of roguelike storytelling

A 20-something girl stands in an elevator. There’s an eye patch on her face, a shotgun on her back, and a pistol in her right hand. The door opens, and she hits the ground running into a room full of drones. They hover over her, firing red lasers completely bent on killing her. After all, why wouldn’t they be? Molly Pop is the head of the Zero Sum Gang, and she’s on a mission to topple the Fero corporation by raiding their bunkers one-by-one. She wastes no time, shooting down the flying robots in seconds, then travelling down a hallway into a large room filled with yet more AIs.

There’s something different here, though. A humanoid figure stares at Molly, firing a gun in his hand. Molly runs up close and unloads her pistol at point-blank range into his face. Blood sprays onto the floor and walls as a poster becomes coated with the man’s viscera. “Downsized?” it asks. “Become a proxyman.” A line of the same humanoid enemies rests in the center of the portrait, ready for duty.

Molly Pop pushes past the ad and heads to the exit elevator. She brags to herself about her successful raid, as she leaves behind dozens of dead proxymen and broken machines in pursuit of her true enemy: Fero’s corporate leaders.

///

Bunker Punks isn’t a standard first-person shooter. Created by industry veteran Shane Neville under the guise Ninja Robot Dinosaur Entertainment, Bunker Punks is about everyday heroes fighting against a wealthy megacorporation at the center of a dystopian society. Players take control of a group of post-apocalyptic freedom fighters bent on destroying the Fero megacorporation by raiding their bunkers, and claiming the loot inside for their own use. Play is split into two segments: building up the gang’s base of operations, and raiding bunkers for resources. Levels are procedurally generated and permadeath is active—meaning no two bunkers are the same, and players cannot load from a past save point if things go awry.

Bunker Punks’s post-apocalyptic world is self-aware of the present

As a roguelike shooter, Bunker Punks is pretty heavily invested in its own lineage. Critics have called the game a throwback to DOOM (1993), hailing its fast-paced combat and engaging gunplay. However, Neville hasn’t neglected the underlying politics behind Bunker Punks. Fero advertisements litter the bunkers’ walls, encouraging profit consumption when money is in excess. Security cameras force employees to be on their best behavior, and bulletins implore laid off workers to join the cyborg proxymen army. The Fero corporation isn’t just a dystopian villain, Bunker Punks suggests—it represents the very worst of late capitalism. In other words, Bunker Punks’s post-apocalyptic world is self-aware of the present. Neville says this is no accident.

“Today, the largest corporations have more money than many countries, and there are private military contractors larger than some armies,” he explained to me. “If the government collapses, it almost seems silly to think that the wealthiest and most powerful people and companies in the world wouldn’t step up and at least provide for themselves.”

In a world where major corporations are given more power daily by the United States government, and federal spending diverts millions upon millions of dollars towards private military contractors in Afghanistan, Neville’s setting is incredibly relevant. In fact, Bunker Punks was written with American geopolitical and socioeconomic fears in mind. The more time Neville spent following current events on social media, he explained, the more he began to think about the ramifications of a global apocalypse in the United States.

“I thought that the world’s wealthiest people would have some sort of emergency plan in place, a place to go and live out the apocalypse in comfort,” he explained. Such is the case in Bunker Punks, where Fero reigns supreme, and its workers are left scrambling for scraps.

///

Humans are hard-wired to learn about the world through experience. Gradual exposure makes us familiar with our surroundings over time. We pick up small threads to hang onto—a certain hallway, a specific food, a special memory—and start to build a relationship with the locations we’ve visited. As we put these thoughts together, we eventually establish a narrative about our experiences. We begin to understand where we’ve been through stories.

In the same way, Neville doesn’t expect the player to understand Bunker Punks’s lore immediately. Rather, players are gradually exposed to the in-game world through hints and clues. Quotations from Molly Pop are placed across loading screens. Caravan merchants make small talk with the player after death. Corporate advertisements reveal how Fero is exploiting its workers. The player learns about the world piecemeal, putting together the full picture as they continue to experience life inside the Zero Sum Gang.

“The storytelling in Bunker Punks is very passive,” Neville explained. “I did this because I want the players to learn about the world bit by bit, as they play. It leaves a lot of questions unanswered and lets the player dig deeper.”

Neville’s approach to narrative design is becoming an increasingly common one in videogames. From The Binding of Isaac’s (2011) item pickups, to BioShock Infinite’s (2013) Vox Populi, action videogames traditionally encourage players to learn about the world as they go along. Questions about motive or origin may be left open, but that’s perfectly fine. As Neville points out, part of environmental storytelling is encouraging the player to fill in the blanks. In fact, this seems to be a staple of the roguelike genre.

Humans are hard-wired to learn about the world through experience

“In roguelikes, each game tells its own unique story. The characters you have, what happens to them, their close calls and easy victories,” he said. “I didn’t want to get in the way of that, so I focused on passive, exploration-based narrative to introduce the players to the world.”

The roguelike genre first emerged in the industry during the late 1970s and early 1980s, when titles such as Rogue (1980) and Beneath Apple Manor (1978) introduced procedurally generated content as a tool in game design. Because no two games could be played the same way, each runthrough possessed individual challenges, victories, and defeats. This meant that every player essentially built their own story as they played, with all the victories and tragedies unique to their protagonist’s experience.

Indeed, because roguelikes are largely driven by procedurally generated content, passive storytelling is an extremely popular approach to worldbuilding in the genre. Take the player character Rogue, from Vlambeer’s 2015 shoot ‘em up Nuclear Throne. Very little is known about Rogue when the player first unlocks her. It’s the contextual clues about her identity that help the player fill in the blanks. She clearly is a former member of the Inter-Dimensional Police Department (or IDPD), due to her blue police uniform. She can’t speak the post-apocalyptic Trashtalk jargon, suggesting that she hasn’t been in the nuclear wastelands for long. The IDPD constantly gives chase to her, implying that Rogue’s former employers are not happy about her sudden departure. Most noticeable of all is the change in level music for her penultimate return to the IDPD headquarters, suggesting something foreboding about her reappearance.

Nuclear Throne never tells the player these things outright, though. Instead, every player ends up creating their own stories about Rogue. Some see her as a scorned police officer thirsty for revenge. Others say she is uninterested in her past, and simply eager to discover the secrets of the Nuclear Throne. Either way, no two fans view Rogue the same way. The game leaves its lore up to the player’s interpretation as they play through the game.

In the same way, Bunker Punks isn’t interested in hand-holding the player through the why’s and what’s of its world. Instead, the game gives the player a base of operations, a gun, a player character, a premise, and an enemy to kill. The rest comes through in bits and pieces, vis-à-vis the player’s actions. Reading Fero’s advertisements reveals the proxymen’s true nature, for example. Character bios provide additional backstory regarding the Zero Sum Gang’s history and Fero’s nefarious deeds. By simply playing through the world, the player comes to learn how determined Molly Pop and her allies are to destroy the megacorporation from within—even if that means losing their own comrades in the process.

///

Despite its popularity in roguelikes and action-adventure titles, videogaming isn’t the only art form interested in environmental storytelling. In fact, musicians are often fascinated with the subtext behind the worlds they build, too.

In 1975, Bruce Springsteen released Born to Run, one of the most critically acclaimed albums of his entire songwriting career. The album continued a longstanding trend in Springsteen’s discography of referencing locations across New Jersey. In particular, Springsteen’s closing song, “Jungleland,” features a 9 minute and 34 second ballad about street life in the Garden State and New York City during the mid-1970s.

environmental storytelling is a natural way of processing information

Springsteen never directly states where “Jungleland” takes place, however. Instead, clues are dropped throughout the story—Flamingo Lane seems to be referencing the Flamingo Hotel in Asbury Park, and the “giant Exxon sign that brings this fair city light” appears to be an actual Exxon sign in the town. Each of these objects and symbols paint a larger picture of an area drowning in sorrow and despair, and Springsteen allows the listener to fill in the blanks themselves. Every story becomes a personal one about isolation, desire, and loneliness in mid-20th century American life.

Granted, when Springsteen sat down to record Born to Run, he certainly didn’t have the fledgling videogame industry in mind. But his approach to storytelling—one based around a gradual introduction to locations through symbolism and description—mirrors the roguelike genre in its own right. And both videogaming and music draw on the senses to orient their audiences into their artists’ worlds. Again, this is no coincidence. In fact, it’s quite a natural way of processing information.

According to Karl Kroeber’s 2006 work Make Believe in Film and Fiction: Visual vs. Verbal Storytelling, perceiving one’s environment is “psychosomatic” in its functioning. Referencing Raymond Williams and J.J. Gibson, he explains that human psychological perception is a “proactive process for entering into the environment, orienting ourselves, exploring, investigating, seeking.” In other words, human psychology is based entirely on environmental exploration and investigation. Therefore, Gibson’s theories suggest that environmental storytelling is a natural way of processing information, because the human mind is hard-wired to engage with objects while in motion. After all, as Williams says, “new facts about perception [are] a determining relation between neural and environmental electrons.” Humans build meaning from new information about their environments, as opposed to static descriptions of individual locations.

“Registering movements with acuity facilitates our exploring of our environment, actively entering into reciprocal engagement with it,” Kroeber states. “The most common and ingrained mistake about our perceptual systems is to think of them as passive, as mere receptors.”

Granted, Kroeber’s work focuses largely on visual processing in film criticism. But the body’s ability to process and understand information is, psychologically speaking, the essence of human life. In other words, as people, we want to learn more about our environments by experiencing them. Whether that’s a nuclear apocalypse, or an urban wasteland, artists that leave their work up to interpretation end up appealing the most to their viewers, listeners, and players by mimicking the ways our brains naturally function. They replicate real world psychology through art.

///

Much has changed since Shane Neville first began working on Bunker Punks in 2014. Back then, the Obama administration was still halfway through its second term in office. Edward Snowden’s NSA leak had just changed the landscape of Internet privacy. Drones were a looming concern, but few thought they were anything more than a science-fiction dream. “Presidential Candidate Donald Trump,” was a punchline, not an anxiety. Now that Bunker Punks has entered Steam Early Access, Neville’s game is in a very different world.

“Unplanned or not, it suddenly became satire.”

“In the process of building a science-fiction setting, sometimes the fiction is too close to reality, and instead of being fiction it becomes satire,” Neville said. “Two years ago, I had this idea that the richest people in North America would build giant walls to keep out poor people. Now, this has become a campaign promise. Unplanned or not, it suddenly became satire.”

More than ever, Americans are afraid of the rise of megacorporations. In a game where downsized workers become cyborg henchmen, and wealthy businessmen dictate when its wage laborers should consume, Bunker Punks finds itself in a political environment ripe for its story. Neville’s world captures the issues driving at the heart of today’s recession.

But perhaps this is the very nature of environmental storytelling in roguelikes. Instead of telling a linear story, Neville has simply given his players the opportunity to fill in the blanks with their own narratives. It means that each runthrough of Bunker Punks becomes a personal story for the player—with all the highs, lows, and political anxieties it may involve.

The post The irresistible appeal of roguelike storytelling appeared first on Kill Screen.

Hyper-Reality imagines the hell of our Augmented Reality future

Augmented Reality (AR) is the mixing of the world as we know it with the digital world. Fittingly, it has long blended with videogames. In the popular rhythm game series Hatsune Miku: Project DIVA, if playing on a PlayStation Vita, the player can enable an AR Mode and carefully orchestrate where Miku and her Vocaloid pals are placed in the “real world.” But know this: Miku is not a person. She’s a purely digital pop star, and even plays live concerts as a projected hologram—what some might call the ultimate AR experience.

Alongside some odds and ends in miscellaneous Nintendo 3DS games, AR has felt more like a complement to technology and life as we know it, rather than integrating the two seamlessly. But in designer and filmmaker Keiichi Matsuda’s Kickstarter-funded short film Hyper-Reality, life itself is a game.

Matsuda’s long experimented with the wishy-washy premise of AR under his blanket series “Augmented (hyper)Reality.” Six years ago, Matsuda first embarked on this journey with two short films: Domestic Robocop and Augmented City 3D, two After-Effects laden videos showing the more questionable side of AR’s potential. It’s an AR-embodied future that obscures literally everything we see through our own eyes with digital candy.

In 2013, Matsuda launched a Kickstarter campaign for the cherry on top of the “Augmented (hyper)Reality” cake: Hyper-Reality, a Colombia-based short film about a middle-class AR user, and the dangers she faces when hacked by an unknown user. Recently, the short film was finally released to the public (following screenings and crowdfunding backers getting the opportunity to watch it first, of course). In Hyper-Reality, the digital and physical worlds have merged into a singular kaleidoscopic technicolored vision of reality, so much so that the brief shattering of the AR-induced world is incredibly jarring for the dependent user.

Hyper-Reality is our worst nightmares about AR fully realized

Hyper-Reality is a fever dream. It’s our worst nightmares about AR (and even, to another extent, virtual reality) fully realized. A future in which seedy advertisements plague our every vision within an AR “freemium” software. A future in which even the most mundane tasks in our daily lives are gamified by ever-accumulating points and prizes. Even points are often necessary to progress through even the most essential errands, such as grocery shopping. Taking on religion in a time of crises is celebrated through a pop-up “Level Up” banner, as if the film’s protagonist hadn’t just been robbed of her very identity via a hacker moments before. Matsuda’s AR-future is truly a terrifying one, but boy, it sure is pretty to look at.

You can watch Matsuda’s Hyper-Reality below, and read more about the project here .

The post Hyper-Reality imagines the hell of our Augmented Reality future appeared first on Kill Screen.

Myst and the truth of objects

This article is part of our lead-up to Kill Screen Festival where Robyn and Rand Miller, creators of Myst, are keynote speakers.

///

Your job in Myst (1993) is to assemble books. Set aside for a moment the impossible grandeur, hermetic mythos, and resonant cultural legacy of the game and this is what you’re left with—red page, blue page. Eventually there’s a white page. These pages are objects. Any decent open-world game of the last few years will allow you to cart around hundreds of pounds of literature without slowing your upswing, because in these games, the books aren’t objects. They’re not even tools, like weapons or torches, which have weight and occupy space when you wield them. They’re information. But in Myst, where an entire completed volume is a sanctified, dimension-transcending treasure, you traverse great distances and surmount mighty obstacles to carry each page home one at a time, like exiled infants. There’s room for nothing else in your inventory: pick up the red page, you put down the blue one. In a rare moment of authorial magnanimity, there is even a menu option that is hard to imagine appearing in any other videogame—”Drop Page.”

The irony is that for all this focus on the palpable and concrete presence of books, there is very little information to be found anywhere. A cryptic note on the hillside, a mostly-charred library, and a handful of incomprehensible symbols are all you have to work with in the beginning. The rocket and the dentist chair sitting on either side of the library seem like the signatures of some absent author—but they aren’t talking. The books eventually do open up to you in a decidedly non-bookish way: insert the red or blue pages in the appropriately colored library volumes, and you get to watch (by way of portals stamped into the naked pages) a series of short films memorably starring creators Rand and Robyn Miller as the evil brothers Achenar and Sirrus.

The decision to use video footage for the cinematic moments of the the game was, of course, a result of the technological limitations the Rand brothers were working with in the early 90s. Sequels would integrate motion capture technology and more advanced animation techniques. But the decision to put a movie inside a book inside a game is an aesthetic decision, and one completely of a piece with the ingeniously syncretic design of Myst. The Millers weren’t beholden to their technology; like great artists in every field, they make its shortcomings work in their favor. They affirm the blunt objective reality of each medium used to play the game—the static on the video screen, the CD-ROM icon that pops up during loading intervals, the weighty pages—as a reflection of the story’s focus on broken-down technology. It’s just one example of how, in this game, meaning isn’t derived from the acquisition of information or goal-directed catharsis; it arises from an engagement with the depths of objects.

In order to conduct their object-oriented symphony, the Millers had to dehumanize books as much as possible, depriving them of any privileged place in the plan of nature and scattering them in silence among their corporeal cohabitants. Scrape a page clean of text and all you have left is a dead tree. But you never really feel alone wandering through Myst’s quiet forests and forsaken fortresses, for the objects you encounter there—the rocket and dentist chair, the pumps, ball valves, telescopes, ladders, and lighthouses—speak their own language. There’s no glossary, but you have to learn it all the same if you want to get anywhere. This is why you are equipped with a hand instead of a cursor, arrow, or any other post-literary artifact of abstraction—acquaintance with an object is a strictly tactile affair.

the game disrupts any sense of acquaintance

Gripping and grasping my way back through the Ages of Myst in recent weeks, I was reminded of a distinction the philosopher Martin Heidegger makes between objects that are “ready-to-hand” (Zuhanden) and objects that are “present-at-hand” (Vorhanden). Ready-to-hand objects are the ones we encounter with an eye to their use: you don’t contemplate the design of your engine in the morning, you just want it to start. But if the engine doesn’t start because something breaks, it comes quickly to your attention—you now have this thing to deal with. In resisting your projection of a function onto it, the present-at-hand engine affirms its being as something fundamentally other.

For Heidegger, this jolt out of “everydayness” can lead to two outcomes. We can analyze the object’s properties and try to understand it better so that we can fix it and keep it inconspicuously churning in the future. This is the approach of technocratic capitalism, the reigning ideology of our time. The other approach is that of the artist, who is inspired by that initial defamiliarizing shock to perpetuate it with other materials and by artificial means. The artist’s true calling isn’t to portray objects the way everyone already sees them, but it isn’t to show us something new either; it is, paradoxically, to present what was already present as though we were seeing it for the first time.

By this standard, Myst represents art of the highest order. Trans-dimensional portals aside, few of the objects you encounter in Myst are truly alien artifacts. In another context, or in another game, the rocket and the dentist chair might so befit the environment that you wouldn’t even give them a second glance. But by presenting them as broken-down, misplaced objects whose function doesn’t match their form, the game disrupts any sense of acquaintance before it can settle in as a veil over their essence.

This is why the world of Myst still, in 2016, feels more genuinely extraterrestrial than any number of more overtly fantastical (not to mention better-funded, better-staffed) studio creations. It’s true, of course, that some of these objects will eventually function as tools to be used in solving the game’s puzzles. Thus the hand cursor has two different modes, one for what is interactively ready and the other for what is merely present. But since, in this game, we never have a proverbial rug under our feet to begin with, there is no sense of security restored and no comfort regained when a puzzle is solved. There is only a kind of passing levity before we re-submit to the gravity of the tangible.

///

Myst has had a heavy burden to carry since the first weeks of its release. Here was a strange game about strange technology that made the technology it was made for mainstream for a decade. Here was a modest, quiet dream that sold six million copies and became a talking point for people who generally thought of games as things for kids to waste time on. In the apparently perennial conversation about whether games are truly Art, Myst has ever since been an essential reference point, like Ico (2001) or BioShock (2007) after it. But this kind of adulation has its downside, as Myst also became a favorite target for every new generation of game critics eager to kill its idols. This has led to a series of hyperbolic charges over the years—most infamously, Gamecenter‘s proclamation in 2000 that Myst “killed the adventure game.”

A better conversation might not dwell on whether games deserve their place in the pantheon of the arts, but which games deserve it. This requires choosing some basic criteria; without a set of requirements for what constitutes art, how could the debate be anything but interminable? Yet it is difficult for a critic to adumbrate criteria without implicitly privileging some subsection of the very works up for debate. One way out of this quandary is to really pay attention when universally recognized artists themselves try to define their craft, for even if their own definitions are selective, they can offer a perspective on creativity that critics by and large do not have.

A few years ago, in honor of Myst‘s 20th anniversary, Emily Yoshida wrote a wonderful retrospective on the game for Grantland (RIP) that included an interview with Rand Miller. Yoshida took the opportunity to press Miller about a particularly arcane plot point that has little significance in the game itself, but huge ramifications for anyone trying to understand it. The issue concerns the game’s “linking books,” which contain the portals that allow for travel from Myst to the Ages and back. In the game, these linking books were written by Atrus, the father of Sirrus and Achenar, using “the Art” he inherited from the extraterrestrial wordsmiths on his father’s side of the family. Those with the Art are able to pass through their books and see the worlds they describe come to life. However—and this is the crucial point—they don’t actually create the worlds they enter; everything was the way it was before they wrote about it.

As Yoshida suggests, the implications of this point are fundamentally theological. A writer with the ability to write worlds into being is a kind of god; what is the writer who can perfectly describe a place they have no information about, and then go to that place? Do they actually have any power at all, or are they pawns in somebody else’s story? When Yoshida raises these issues, Miller has this to say:

“I’ll put it this way,” Rand said. “People ask me all the time if Myst was art. And I don’t even know what art is, so I’ve made up my own definition. I think Art with a capital A, for me, has this intent to communicate truth. Somehow you try to make something—you’ve gotten so good at what you do, you’ve become a master craftsman at what you do, that you can now try to communicate some kind of truth. And truth is a simple thing; it’s just, you know, something about the world around you, something about yourself.”

This apparently incongruous response is illuminating for a number of reasons. It is impossible, to begin with, not to make the connection between Miller’s “capital A” Art and the in-game Art that he and his brother devised. Indeed, Miller goes on to confirm that the decision to make the Art a non-creative power was a gesture of humility on the part of its meta-creators: “It’s good to stay a little bit humble with a powerful thing.” This explains why the objects chosen to populate Myst‘s landscape are mostly familiar ones from everyday life. Rand and Robyn Miller weren’t trying to show us anything new; they were unveiling the truth of objects we already thought we knew by simultaneously defamiliarizing and re-territorializing them.

you can’t put anything into words that didn’t already exist

Equally noteworthy is the way Miller defines the activity of the Artist. He speaks of becoming a “master craftsman,” a fashioner of objects, rather than using the language of—well, language. Miller says elsewhere in the interview that “we’re not game designers; we were place designers.” Hence they constructed the Ages and all their eccentric details first, and then let the environment dictate the contours of the story. This is perfectly in line with Miller’s aesthetic maxim; first you build something, and then you reorient the light so that truth shines through it. If the Millers had taken the traditional approach to building a narrative, letting the characters and plot dictate the details of the environment, then they would have been violating the prohibition that they imposed on their in-game personae: you can’t put anything into words that didn’t already exist.

If we don’t understand how these various dimensions of the game come together under the rubric of a universal respect for objects, then I think we miss the core of what makes Myst worth treasuring over two decades after its release. As a prime example of how easy it is to miss this mark, take the most high-profile game of recent years to be directly inspired by Myst—Jonathan Blow’s The Witness. Blow openly took inspiration from the design of Myst for his own obtuse puzzle game, hitting on all the major bullet points—abandoned island, strange objects, no interaction with anything living. But the puzzle objects in Blow’s game are geometrically rigid, artificial things positively reeking of intelligent design; Blow would rather invent an entire symbolic system of his own than find a way to let common objects speak. Where Rand Miller aspires to be a good craftsman, Blow openly compares himself to Thomas Pynchon, yet substitutes regurgitated information (in the form of pre-recorded quotations) for Pynchon’s gonzo inspiration. He puts in 15 minutes of a Tarkovsky film near the end just for the sake of doing so. Blow seems to think that the way to make a videogame a piece of art is to associate it as closely as possible with examples of great art in other media. It is startling that he doesn’t recognize what a disservice this does to his craft.

Videogames are not books. They aren’t paintings, films, or poems. To insist on evaluating their aesthetic worth by the criteria applied to other arts is to devalue what makes games, for all their diversity, singular. It ensures that they will always maintain the second-class position they once seemed born into, like television before The Sopranos (1999-2007) or pop before The Beatles. On the other hand, games have the potential to integrate all of these other arts in a way the latter can’t reciprocate, as Myst already demonstrated back in 1993 with its technological Matroyshka dolls. In theory, there could well be a Thomas Pynchon of the gaming world. But Pynchon didn’t build puzzles; he wrote words. Imagine a Pynchon successor as just one of hundreds of equally talented people working on a game, and you have some idea of the medium’s potential.

As the debate over games and art rages on, meanwhile, Rand and Robyn Miller are getting back to the business of making some. Obduction, the new project from their flagship company Cyan, is scheduled for release in June. The setup is similar to that of Myst: you come into contact with a strange object which instantly transports you to an alien world that, as the game’s website suggests, looks a bit like Kansas. Only this time, it isn’t a book that initiates the journey; the site describes it instead as simply a “curious organic artifact.” A living object, then, that wants nothing more than to transport you over the rainbow—imagine the stories its world has to tell.

///

To learn more about the Kill Screen Festival and register, visit the website.

The post Myst and the truth of objects appeared first on Kill Screen.

May 23, 2016

Thailand’s military junta is distorting the videogame market

On May 22, 2014, after months of anti-government protests, the Royal Thai Armed Forces overthrew the country’s government, repealed its constitution, and established rule by military junta. It was a momentous event that flew under Western radars by dint of being the country’s 12th coup since 1932. The junta promised an eventual return to democratic rule, but on the coup’s second anniversary there is little reason to expect a handover to civilian power any time soon.

All of which is to say that you have to look really hard for good news from Thailand. And Venture Beat, a reliable source on the affairs of modern capitalism’s pond scum, has done just that. “The great thing about having a military coup is that people spend a lot of time at home,” VentureBeat quotes Playlab CEO Jakob Lykkegaard Pedersen as saying. “So they can play a lot of games. Instead of going to the theme park, you stay home and spend money on mobile games.”

political systems do affect the experiences of people who play games

Pedersen, who was speaking at the Casual Connect conference in Singapore, was hawking a game that needs an additional SEO boost from these parts. It involves smashing bright, cheerful things into each other on a phone, and that’s really about it. (Pedersen, according to VentureBeat, moved to Thailand so he could start his own company. Who said coups aren’t good for some people?) Anyhow, by virtue of Pedersen’s pitch, the game channels the weaselly spirit of Donald Rumsfeld even more effectively than the one Rumsfeld has been shamelessly hawking in recent months. It’s the kind of nonsense you’d expect from the walking Faustian pact better known as Henry Kissinger.

In the interests of fairness, however, let’s try to find something decent enough to say about Pedersen’s point. His business calculus is morally irredeemable, but it’s not wrong to note that political systems do affect the experiences of people who play games. In his essay on games in Venezuela under Hugo Chavez’s rule, J.D. Lopez notes that the price of games soared during the leader’s 14 years in charge. (This market distortion, it should be noted, was also affected by a law outlawing most games.) Developers are not wrong to expect these sorts of occurrences. Thailand, by the by, “has become more militarized than we’ve seen in any contemporary period,” says Thitinan Pongsudhirak of Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University.

The people of Thailand deserve better representation and, if it’s too much to ask, they could also do with better games to play than Pedersen’s while they wait.

The post Thailand’s military junta is distorting the videogame market appeared first on Kill Screen.

How Twitter bots could sway the outcome of the presidential election

In the midst of the most unprecedented election season in recent history, questioning the political power of technology is now more important than ever. From the media to political parties themselves, fear around social platform’s changing the course of history is mounting. Twitter was accused of purposefully pulling a trending hashtag that critiqued presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. Facebook is being investigated for political bias in its trending topics. People now see that these are not just platforms, but curated and published media.

And, like all published media, they come with a bias, be it through a curator’s choices or an algorithm. While these conversations are important, they may lend too much credit (or fault, depending on your perspective) to the CEOs for the current state of political discourse. The comments and posts still come from the users—many of who aren’t even real people. With bots flooding the political landscape in the order of millions, they may be influencing this American election cycle more than anyone could have anticipated.

an illusion of popular support with alarming consequences

A 2013 study found that more than 60 percent of internet traffic is generated by bots. That staggering number may provide some insight into the electoral circus we’re experiencing now. A little less than one third of presidential candidate Donald Trump’s Twitter followers are fake accounts. Hillary Clinton’s percentage is 27 percent, and Bernie Sanders clocks in at 12 percent. While many of these accounts simply sit there bolstering the support a candidate may appear to have, many others are tweeting out support, or worse, tweeting negative things about the opposition. In 2010 a Wellesley College study found that Twitter-bombing may have swayed the outcome of a senate election in Massachusetts. In 2011, former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich was found to have purchased a million Twitter followers; Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party has been accused of using Twitter bots to silence opposition and spread their message. It contributes to an illusion of popular support with alarming consequences.

The world seems woefully unprepared to handle this problem. The Federal Election Commission has as of yet said nothing about the Twitter bot situation. Paid endorsements in politics aren’t legal, but it’s not hard to get around that. If a politician can pay someone to speak at their rally, or act in a commercial for them, they could probably legally pay for fake accounts. Even if a politician can’t do it directly, that still leaves Political Action Committees to act on their behalf. And even if that became illegal, there’s still the task of parsing out propaganda from satire. Then, of course, there’s the little problem of social media sites not being able to handle bots themselves.

Both Facebook and Twitter use a system that relies on users reporting fake accounts, a system that has proven to be inadequate. With the sheer number of bots, it’s difficult to imagine what a successful system would look like. But difficulty is never an excuse for not trying, especially when it’s something so important. Like it or not, millions of voices do influence what we think, and if those millions of voices are manufacturing propaganda disguised as actual conversation, it has a real affect on the turning political tides. New technology means new avenues for manipulation, and we cannot allow that to go unchecked. If we don’t have this conversation now, we may soon find the bots are too loud and too pervasive for us to have the conversation at all.

Header image: Twitter by Andreas Eldh

The post How Twitter bots could sway the outcome of the presidential election appeared first on Kill Screen.

Pixelsynth lets you turn your face into a song

Pixelsynth is a new web app from coder Olivia Jack that allows anyone to compose songs simply by drawing or uploading pictures. It’s available for free over on her Github, and it works by setting music to images in a method similar to a commonly used scientific and musical tool called a spectrogram. Like how sheet music is a language for representing different pitches of notes, spectrograms are visual representations of the spectrum of frequencies that make up a sound. Every song has a spectrogram that can be derived from it, and conversely, any image can be plugged into a spectrogram to create a series of sounds to go along with it. Essentially, all images sound like something.

all images sound like something

Take, for instance, electronic music producer Aphex Twin’s 1999 single “Widowlicker.” I still remember when an old pot-loving former roommate of mine showed me the spectrogram for this song. Towards the end, the normal flow of music stops as a sort of theremin style whine takes its place. In the spectrogram, this is actually reflected as a picture of Aphex Twin’s own face, which he had inserted into the song as a signature of sorts. Like Aphex Twin, Pixelsynth allows you to find out what your own face (or your dog’s face, or your boss’ face, or any image you like) sounds like.

The app comes with a variety of options, allowing users to upload photos, repeat them in a checkerboard pattern, change their width and contrast, draw over them, and manipulate the drawings in a similar way. It also comes with a number of premade backgrounds, as well as the ability to draw without any backgrounds. All the while, a line moves across the screen from left-to-right, turning sketches into sound as they are drawn.

Here’s one where I messed around with a picture of my face for a bit. Go ahead and plug it in to Pixelsynth to hear what it sounds like.

Here’s one with Drake, because of course we had to do one with Drake.

To hear what your face sounds like, you can play Pixelsynth in your browser. For future updates on Olivia Jack’s work, follow her on Twitter.

The post Pixelsynth lets you turn your face into a song appeared first on Kill Screen.

Push Me Pull You’s long stretch to good menu design

Spending time in menus and load screens is often tedious. It can be a time of annoyance and bored Twitter refreshing. Except when it doesn’t have to be. In a blog post from House House, the creators of the recently released competitive game Push Me Pull You, the team described their different approach for the user interface (UI) design of their game’s menus. Instead of a bland menu, House House dreamed of a practically designed UI—one that exists within its own little world. Menus that can even serve as a time for careful reflection, rather than boredom, between the quick wrestling matches of Push Me Pull You.

“We didn’t want our menus’ design to be an afterthought,” writes Nico Disseldorp, one member of the four-man development team behind Push Me Pull You, in the blog update. “We saw them as part of the game itself, and wanted it to feel that way.” In the design for Push Me Pull You’s menu, Disseldorp, alongside fellow game makers Michael McMaster, Stuart Gillespie-Cook, and Jacob Strasser, had two primary goals: to show off their worm-like characters more, and accentuate their snake-like curves to tie separate menu screens together.

House House initially found inspiration for their menus from another recent indie title, last year’s subway-designing game Mini Metro (2015). In Mini Metro‘s main menu, each station along a train track represents a different option, and creates a sense of continuity in looking nearly straight out of an actual level from the game itself. “We felt like our characters’ big bodies could do something similar, and make a winding path that physically drew the menu’s progression,” writes Disseldorp of Mini Metro’s inspirational approach.

“We didn’t want our menus’ design to be an afterthought”

The menus serving an aesthetically continuous purpose wasn’t the sole goal for the team—all the menu’s inhabitants had to act dynamically as well. That means the camera must follow a characters’ body to each separate screen, no bodies must cross paths, and each character must have equal body lengths. With all these rules in place, a UI World is established. And as with all newly established worlds, new music must exist.

“We aren’t the first people to use a [music] system like this, but we might be among the first to make one with so much variety solely for a game’s menu,” writes Disseldorp of the new music composed for each menu scene. The idea was initially pitched to composer Dan Golding half-jokingly (or half-seriously, Disseldorp can’t recall precisely). Golding ran with the idea, writing nearly a dozen dynamic tracks for the menu exclusively. Around six ended up in the final menu design. “All the credit here goes to Dan, who went above and beyond to find the best way to make all this work musically,” writes Disseldorp. “Thanks to him, UI World feels like one consistent piece, but each screen feels like it’s own song.”

Read the full blog post on Push Me Pull You’s unique UI World here . Push Me Pull You is available now on PS4 , and coming to PC, Mac, and Linux sometime soon.

The post Push Me Pull You’s long stretch to good menu design appeared first on Kill Screen.

Nova Alea has a go at criticizing the state of urban housing

Molleindustria’s Nova Alea is a parable in search of a game. It is the story of real estate speculation, housing bubbles, and capitalism run amok.

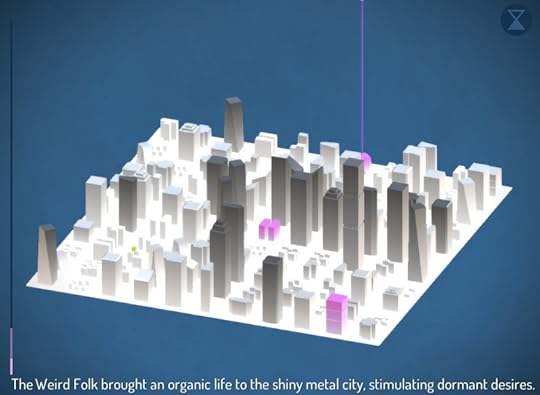

The story takes place on a chessboard—that or a graveyard for skyscrapers. Maybe both. “For its masters,” the gentle-voiced narrator intones, “the city was a matrix of financial abstractions.” Note the use of the past tense: that’s the first sign you’re inside a parable. The powers of finance are represented by a tilted pink cube—think Tony Rosenthal’s “Alamo,” but cuter—that floats above the city. More accurately, it looms, dropping capital in underdeveloped neighborhoods and hopefully extracting profits before bubbles burst. Do it well and you’ll become rich; get the timing wrong and you’ll go bust.

Only it doesn’t really matter if you do a good job as a speculator. Nova Alea is transformed regardless. Shadows are cast by growing towers. Longstanding communities, one hears, are pushed out. Sure, some of the speculators may go bust, but that doesn’t return the displaced to their communities. There is nothing left for them to come home to. The logic and consequences of high-flying capitalism, as represented by the cube, has nothing to with life on the ground.

It also doesn’t really matter if you do a good job as a speculator because Nova Alea is impervious to human inputs. Your clicks move the game along, but they just bring about set queues and beats. Molleindustria’s is a game that tells instead of showing. There is no solution to the problems presented, just a vicious cycle in which you impotently click away into the ether.

Nova Alea has blind spot for all but its intended targets

People are an abstraction in Nova Alea, which is both the game’s central point and its biggest problem. At a certain point, Molleindustria’s criticism of capitalism’s cold indifference to the little people morphs into its own cold indifference to the little people. That point, incidentally, is when the “weird folks” arrive. “In the craters left by the cyclical crisis,” the narrator sweetly intones, “the Weird Folk settled. The Weird Folk brought an organic life to the shiny metal city, stimulating dormant desires.” They are some form of hipster, one imagines, perhaps the more accurate description would be that the “Weird Folk” are Richard Florida’s “creative class.”

Are these “Weird Folk,” whoever they may be, not also dislocating some residents? Do their actions not have economic consequences? The parable of Nova Alea has no room for these questions, but they linger nonetheless. This is a game that proposes that actions within the carefully calibrated ecosystem of a city have consequences yet seems blind to some of them. To be fair, the “Weird Folk” and speculators are in no way equals, but Nova Alea has blind spot for all but its intended targets.

The game’s chessboard is literally and figuratively white. That is its only constant. Nova Alea is curiously impervious to the effects housing policy on different racial groups. “If zero is a measure for perfect integration and 100 is complete segregation,” writes BBC News’ Rajini Vaidyanathan, “analysis from Brookings showed most of the country’s largest metropolitan areas have segregation levels of between 50 to 70.” The construction of Nova Alea simplifies and stylizes certain facts, but this is more than a simplification. Vaidyanathan continues:

Racial and socioeconomic segregation are closely linked – if you’re a black person in America, you’re more likely than a white person to live in an area of concentrated poverty.

This isn’t simply a matter of choice, or chance. Some of it is by design – and down to decades-old housing policies which actively prevented African Americans from living in certain areas.

Nova Alea, as with much of Molleindustria’s output, belongs to a form of leftist criticism that prioritizes class above all else. As such, it is often good at identifying big villains, while struggling to identify challenges at ground level. The “Weird Folk” is slippery abstraction, rendered as green cubes, that avoids careful interrogation. Nevertheless, the game’s blind spots are often more noticeable than its points. There are no people in the ultracapitalist’s dreamscape, just as there are none in Molleindustria’s. If Nova Alea is a parable for our age, then, it is perhaps an account of more flaws than its creator might care to mention.

The post Nova Alea has a go at criticizing the state of urban housing appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers