Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 115

May 26, 2016

Soft Body helps you find serenity among chaos

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Soft Body (PC, PlayStation 4)

BY ZEKE VIRANT

The words “bullet-hell” may not immediately call calm and tranquility to mind. But meditative app/game Soft Body is here to fix that. Combining the difficulty of Super Meat Boy (2010) with the serenity of a zen sandbox, Soft Body challenges you to overcome obstacles with a meditative approach. Requiring players to split their attention between controlling two “snakes,” operated by opposite hands, the game helps mind and body focus on accomplishing tasks in tandem. Featuring various color palettes and diverse maps, players must protect their snakes from an onslaught of bullets. Through hard work and diligence, players learn to use their soft bodies and minds to conquer even the most trying challenges.

Perfect for: Yogis, bullet-hell lovers, bonsai trees

Playtime: Minutes per level, several hours to complete all 100

The post Soft Body helps you find serenity among chaos appeared first on Kill Screen.

The power of silence in Hitman: Blood Money

War games have consistently failed at making me feel like an invader. Their stories, almost always, involve Western troops on top secret missions behind enemy lines—myself and my AI squad mates are supposed to be interlopers, constantly vulnerable amid a foreign, hostile environment. And yet, we master our surroundings, and our enemies within them, entirely. On-screen objective markers tell us where to go. An arsenal of science-fiction weaponry ensures our safety. Videogames are sycophantic. We, the players, must always be comfortable. We must be provided with the necessary equipment and navigational tools so as not to become stuck (or even face considerable challenge), and regularly patted on the back, told that we are good, that we are the hero—we must know that it is our actions, and what we choose, that matters most.

Hitman: Blood Money (2006) is not sycophantic. It values its players’ intelligence and attention above their enjoyment, and certainly above their egos. It’s a game that encourages players to take concomitant responsibility for keeping its story and tone cohesive. Surreptitiously, Blood Money motivates players to think and act in ways that compliment its creators’ vision. Anyone searching for answers to the question of ludonarrative dissonance (I have no idea why that term has become a joke, or why people are skittish about using it) would do well to play Hitman: Blood Money. To put it simply, this is a game where, without realizing, players consistently think and behave like their character. Considering Blood Money’s central character is a sociopathic, inhuman murderer, that is no small feat—the game-makers achieve it by making the player always feel as if they are an invader.

Blood Money’s weakest missions are its most normal. The vineyard, steamboat, wedding, and White House levels take place in locations that are familiar to us due to the prevalence of their real life counterparts—the enemies are merely gangsters, cops and soldiers, housed in recognizable architecture. The sense of being an interloper, inhabiting a space that is alien which can only be successfully traversed if one pays close attention, is felt more strongly in Blood Money’s other sections. The rehab clinic, the Heaven and Hell party, the Mardi Gras parade, and the Playboy mansion-style mountaintop soirée are much more elaborately designed. They are more colorful, more complex, more idiosyncratic—your targets at the vineyard are simply drug dealers; at Mardi Gras, they are a married pair of assassins disguised as giant crows.

Affectations such as these (the pedophile opera singer, killed on stage after the player swaps his prop pistol for the genuine item is another) are often understood as exemplifying Blood Money’s “art style” or its “humor.” But they are more than simple flourishes. Agent 47, the player character, is a human clone: comprised of various people’s DNA, and developed in a laboratory, he is not a person, in the true sense of the word. Nor does he have access to human emotions—specifically, he was bred to be an efficient murderer, and so feels no remorse and no guilt, and does not develop attachment to people. Blood Money’s “art style,” its many strange characters and unique locations, are designed to make players feel as if they, too, are an outsider.

players consistently think and behave like their character

When first playing Blood Money, one may simply marvel at creator IO Interactive’s willing and ability to create distinct and disparate levels—here is a rare example of a game-maker reluctant to recycle textures, enemy designs, and other videogame assets. Further considered, Blood Money’s variety of locations and targets is conducive to creating in the player an assonant frame of mind. Level upon level, she arrives in new and exotic places. Knowledge of basic mechanical conceits may carry over, but she is forced to imbibe and comprehend an unfamiliar setting. And, of course, she is always on her enemy’s turf. 47 does not assassinate his targets out in the street—he hits them at home, invading their domiciles, their parties, and their places of work to (sometimes metaphorically, sometimes literally) kill them in their sleep. In virtually every mission of Blood Money, 47 is a rogue presence. The player, constantly wrong-footed by the changes in surroundings and people, feels as he does, unfamiliar and unattached: a non-human, temporarily trespassing upon a world where she does not fit.

This dynamic is present, also, in Blood Money’s objective and mechanical structure. Levels are open-ended—the player is perhaps given hints, but largely she must devise and execute her own route to her target. Weapons must be smuggled past guards, security cameras must be evaded, a silent and complex assassination is rewarded by the game above a loud, simple one. In short, Blood Money’s levels are self-contained puzzles. The player is given a problem—47 cannot enter this area without alerting the guards—and a solution: by following this lone guard to the bathroom, she can knock him out and take his clothes as a disguise.

If Blood Money wants its player to feel alien in her surroundings, appropriately, its levels are designed to be perplexing. The player cannot simply traverse: she has plot to scheme. For 47, an emotionless non-person, and for the player, who temporarily inhabits new and peculiar game spaces, the successful navigation of which requires effort and forethought, the human world is very literally a puzzle. 47 does not understand and cannot empathize with people. The player arrives at each mission unaware of what to do and how. To comprehend the people and the place around her, she must work hard and pay close attention, and through that process, of steadily evaluating the roles everyone and everything play as pieces in a puzzle, she develops the same detached, dispassionate mindset as Agent 47. Both are disarmed by their lack of understanding of the environments they fleetingly inhabit. Both develop their understandings not through ingratiation but through cool observation.

the human world is very literally a puzzle

And that cool observation, as well as its puzzling level set-ups, is encouraged by Blood Money’s absence of sound. Save for some choice clips of dialogue and occasional ambient effects, the missions in Blood Money are largely silent—rather than diegetic sound, the player is accompanied by Jesper Kyd’s score. Experiencing the levels this way, able to see but not especially hear the people around her, the player is not only forced to use her eyes and to regard non-player characters as silent game pieces, like those on a chessboard, she is unable to fully immerse in the world around her. Such an aesthetic was taken to its logical conclusion in Hitman GO (2014), an acknowledged puzzle game wherein guards and civilians appear literally as pieces, silent, largely inanimate, all to be coolly removed from the board by the player. Here, 47, again, is a non-human. Humans, to him, are “others.” And in the incongruously quiet levels of Blood Money and the utterly silent boards of Hitman GO, he cannot hear their screams.

In this silent, strange world, constructed with a puzzle-like complexity, a sense of belonging—a sense of ownership, or agency—must be hard won. Hitman: Blood Money, though it casts the player as the world’s greatest assassin, reminds her constantly that she is disarmed, that she does not belong, that in its simulated human world she has no jurisdiction. Too often videogames pander to their players. They make them not just comfortable but confident. In what ought to be dire, disempowering scenarios—a soldier, fighting a war on foreign soil—players are allowed to feel superior, even brazen. Blood Money does not deliberately obfuscate the player.

Its subversion of typical videogame power transference, whereby game-makers bestow upon players as much agency as possible, is not overt. Blood Money is not a snarky game. But it deftly undercuts players’ expectations by placing them into a world in which they do not belong. The player does not merely inhabit 47 physically: unable to hear what the humans are saying, yet encouraged to regard them as they go about peculiar routines. She inhabits him mentally. And in doing so begins to feel less like a videogame player, in the cosseted, pandered to sense, and more like an interloper—a person who must use intelligence and perception, two virtues all too often ignored or even disparaged by videogames, in order to succeed.

The post The power of silence in Hitman: Blood Money appeared first on Kill Screen.

May 25, 2016

See a beautiful black-and-white world unfurl as you move

Stroke is a new short game from James Coffey that plays a bit like a movie theater roller coaster ride. You know the sort: short vignettes that advertise the brand of the theater right after the previews finish but before the movie starts. These shorts are known for their over-the-top nature and flashy effects, with coaster tracks being made out of licorice or popcorn kernels exploding in the distance as the cart swings by. There are many different versions depending on which theater you visit, but the one factor linking them all together is that something is always moving in them. Similarly, something is always moving in Stroke.

On his website, Coffey doesn’t say much about himself other than that he is a “game designer with a very strong passion towards the visual side of game design.” This is understandable, as Stroke is first and foremost a game about visual effects. Arches form over you while running forward, and geometric shapes fade in and out of existence in time with your footsteps. Gems wait to be caught at the end of tracks before disappearing just as you reach them, and hidden springs blast you into the sky at unexpected moments. It’s a highly choreographed affair, with all the pomp of a Vegas show. Except for one key difference: there’s no color.

something is always moving

Typically, special effects features tend to go for neon and bright colors to emphasize their excitement, as is the case in Sonic the Hedgehog’s similar special stages. But Coffey instead decided to look to atmospheric monochromatic games like Limbo (2010) and The Unfinished Swan (2012) for inspiration. It’s not what one would immediately expect from a game of this style, but it works well, emphasizing the movement of the environment rather than the glamour of its architecture.

The effects in the game are actually inspired by Coffey’s previous game, Orbits, which allows players to create their own visual effects (this time in amazing technicolor) while listening to a song from Australian electronic music producer Flume. Similarly, Stroke is set to an upbeat electronic track that pairs well with the momentum of the game.

Stroke is available for free on itch.io, and is only about 10 minutes long. My suggestion is to hold the shift key and just keep running forward the whole time. The game will play out almost like a cartoon, with its minimalist visuals dancing across the screen like an art-deco burlesque club. Then you can load it up again and see what happens when you slow down. The bombast of the visuals pairs well with the black-and-white color scheme, creating a roller coaster worth getting in line for over and over.

You can download Stroke over on Coffey’s itch.io, and you can follow his Twitter for updates on his work.

The post See a beautiful black-and-white world unfurl as you move appeared first on Kill Screen.

Turn the internet into a floral garden for a happier browsing experience

The Internet is, by and large, an ugly place. This is a reality partially informed by the choices we each make (some more than others, granted) but largely attributable to choices made upstream, before websites arrive on our screens. To beautify the Internet, then, is to wrest control away from the powers that be.

Pol Clarissou’s The Quiet Gardens of the Internet lets you turn every website into your happy place. The Google Chrome extension places a flower button in your navigation bar that you can click when in need of relief. Shortly thereafter, by the magic of Unicode, it replaces all the text on your screen with floral emojis. The effect alternates between serene and cacophonous; the flowers are calmer than digital invective but the effect is still quite busy. Even Liberty of London would find this to be an extreme floral pattern. But calm on the Internet is relative and hard to come by, so The Quiet Gardens of the Internet does exactly what it promises.

vandalism is a way of (re)asserting control over contested space

A similar extension is Addendum—a collection of visual essays created by the arts non-profit Kadist, which turns the sort of private statement Clarissou’s extension offers into a form of political discourse. Addendum replaces ads on websites with curated photo-essays from contributing artists. In a narrow sense, Addendum is a political statement akin to using an ad-blocker: both interrupt the economic flows of websites and, in theory, push for changes to their underlying business models. Addendum, of course, adds the beautifying quality of The Quiet Gardens of the Internet to the traditional ad-blocker model. It reallocates space instead of simply erasing it.

Very little good ever comes from comparing the Internet to physical space—it is famously not a set of tubes—but that is the salient comparison when thinking about the politics of these extensions. Much as graffiti and murals exist on a spectrum of uses of public space, so too do extensions. They are ways of reclaiming digital real estate for the needs of locals. Ads and content, after all, are served upstream—assembled on a server before being sent to your computer. Extensions, however, represent decisions made on the end user’s system. Here, as in the physical world, vandalism is a way of (re)asserting control over contested space. This perspective does not solve all the moral questions about ad-blocking or how the Internet should work, but it gives us a bit more language to rely on when discussing digital spaces. The urban sphere, where the contested politics of space and its competing uses has a longer history, can help in navigating digital spaces.

You can get hold of The Quiet Gardens of the Internet on itch.io. Addendum is available through its website.

The post Turn the internet into a floral garden for a happier browsing experience appeared first on Kill Screen.

Explore a bleak British town in a Kafkaesque adventure game

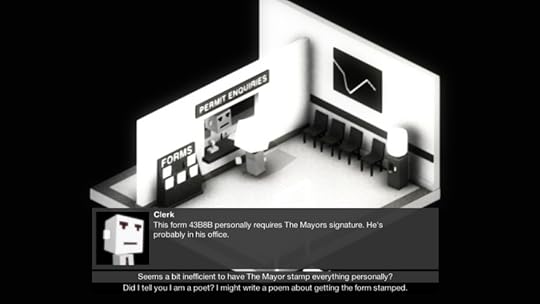

The northern England town of Grimsfield is bleak—completely desaturated of color, existing solely on small, square dioramas. Its inhabitants, architecture, and virtually everything within it are completely cubular, except for some dashing, rare berets. Everyone within Grimsfield is self-absorbed, the protagonist perhaps most of all. He’s an ex-detective who has recently given up on his day job to pursue his dream of becoming a poet. But if only life were that simple in this Kafkaesque adventure.

The rules-laden town of Grimsfield is all about making your life inconvenient

Adam Wells, the creator of the point-and-click adventure game Grimsfield, is an animator by day, newly-dubbed game designer by night. Grimsfield is his first, and “possibly last,” foray into game development. “I figured the most interesting thing I could do is produce a small adventure game, similar to a Twine game, but with a few more graphic elements to give it a sense of location and tone,” explained Wells in a blog retrospective about the experience of making his first game. “I tend to enjoy games and films that show rather than tell.”

Grimsfield’s a short game, running from about 45 minutes to an hour. All along the bite-sized adventure are enriching, silly characters that are fiending to tell you about all their problems—whether you like it or not. And you won’t like it. You always seem pestered when asking another cube-headed person about where they got their beret, or scoff when you learn you have to go another office to get a stamp on a form. So many hoops to jump through just to be able to perform some live poetry, man. The rules-laden town of Grimsfield is all about making your life inconvenient.

Grimsfield is emblematic of Wells’ own past work. The cubular styled characters from his short film Brave New Old (2012) return for his videogame debut. This time they’re coupled with the noir-driven style of his short The Circle Line (2013), combined to create a singular, yet familiar style for the game. Wells also cited the classic noir adventure game Grim Fandango (1998) (most particularly the Blue Casket location—wherein Manny recites some spontaneous poetry) and the solipsistic Blue Jam Monologues radio show from comedian and writer Chris Morris as notable influences for Grimsfield.

Among these pointed aesthetical points, Wells also sought to emulate the absurdist comedy of British comedies, such as Catterick (2004) and The League of Gentlemen (1999). “I knew I wanted to portray a side of England in games I have never seen,” wrote Wells of the obscure influence. “I and many others fetishise the likes of Twin Peaks and small town Americana for its assets and tone. But small town Britain is equally fascinating.”

The absurd, bleak town of Grimsfield is available to explore on PC or Mac via itch.io or Steam for $3.99 (a price that would especially please the town’s shop purveyor Sexy Jim).

The post Explore a bleak British town in a Kafkaesque adventure game appeared first on Kill Screen.

Why the future of esports is mobile

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Popular new mobile titles like Vainglory (2014) and Clash Royale show the promise of competitive esports on the go. While esports competitions continue to emphasize PC games like League of Legends (2009), new titles available on mobile devices are shaking things up for players and fans. According to a report released last year by the NPD Group, younger kids are playing games on their phones more than any other device. Game studios have taken note, creating mobile games that appeal to core and casual players alike. “Somebody’s going to create [these multiplayer competitive games] for the touchscreen generation,” said Kristian Segerstrale, COO and Executive Director of Super Evil Megacorp, the studio behind Vainglory, a mobile multiplayer online battle arena game.

Segerstrale said Blizzard Entertainment, Riot Games and Valve showed they can grow big communities of PC players, and mobile devices could be next. To get there, Segerstrale believes mobile designers need to appeal to a traditional PC audience while remaining approachable to the more general smartphone audience. When Vainglory was first unveiled in 2014, for example, a guild for competitive mobile gamers didn’t exist yet. Designed for mobile platforms, Vainglory is a simplified version of PC games that pit teams against one another in battle.

A little more than a year later, the Vainglory guild organization “Gankstars” is forging this new on-the-go arena. According to the team, what started as a casual guild to help friends play games together quickly blossomed into a household name in the small but rapidly growing world of competitive Vainglory. The members of team Sirius, part of the Gankstars guild, ranked as world champions after winning the first-ever Vainglory International Premier League in South Korea last year. Their success not only speaks to the growing popularity of all different kinds of esports, but also the promise of esports on such ubiquitous platforms as iOS and Android. It also helps that the game is accessible to a variety of audiences, which Segerstrale stressed, can be difficult. “Being respectful of the very casual player as much as we are respectful of the core player will be a big challenge,” she said. “The companies that will truly create the stand out product and experience over the next five to 10 years on touchscreens will be able to do that well.”

While Vainglory aims to ingratiate PC players, Supercell’s recently released Clash Royale hopes to be the one to bring esports to the “anyone with a phone” demographic. A strategy game from the makers of hugely popular Clash of Clans (2012), Clash Royale combines the collectible card game with tower defense mechanics. It’s already brought in close to $110 million since it was released in early March. “It has everything it needs to be a really popular competitive game,” said Marcus Graham, Director of Programming at Twitch. “World of Warcraft (2004), League of Legends, these are games that at their core had millions and millions of people playing the game,” Graham said, noting that this gives popular games a leg up on the competition. “If you have 10 million players and you say you’re doing a tournament for the game, it’s easy to be a success even if you only get one percent of those players involved.”

Mobile games offer built-in simplicity

Graham and others believe mobile esports could outsize existing PC esports communities. The free-to-play model has worked well for esports in the past. “Free-to-play battle arena games like League of Legends are where the trend is,” said George Woo, events organizer at Intel and the man behind Intel Extreme Masters. “Games with free distribution probably have the most leg for being successful in esports because there’s a larger population of people playing it.”

Mobile games offer built-in simplicity, such as eliminating the need for external controllers, which can bode well for streaming, according to Koh Kim, co-head of business development at Mobcrush. Mobcrush, a mobile streaming app that sponsors Gankstars, requires little setup compared to its counterparts on PC. “In the PC realm, the user interface itself is really complicated,” said Kim. By catering to a mobile-centric audience, Mobcrush aims to introduce game streaming to a larger, more diverse audience. “People who probably have never streamed before, [lacking] the means or the technical know-how, now have the ability to engage with other users in real-time,” said Kim.

Perhaps the biggest perk to mobile esports is that the gameplay is intuitive for the smartphone generation. Alex ‘PwntByUkrainian’ Novosad, co-founder and manager of Gankstars, said playing games with a touchscreen “just feels natural.” Twitch’s Graham said that the growth of esports on mobile has the potential to transform existing PC games. “Eventually we’re going to have our League of Legends for mobile,” he said. “We’re going have a game that’s played worldwide, where you can speak a language completely different from someone else, but [the game is] the language you speak together.”

The post Why the future of esports is mobile appeared first on Kill Screen.

Teach yourself to think more like a computer

What is the function of rationality? How much efficiency is lost to irrational impulses? How can a person overcome these natural irrationalities? These are the questions posed by the Center for Applied Rationality (CFAR), an organization dedicated to learning how to use your brain to the best of its ability. This is managed by training it in rationality, defined by founder Anna Salamon as “the ability to form accurate beliefs in confusing contexts, and achieve one’s goals.” The CFAR’s website elaborates to explain that they make no pretenses towards aiming for “perfect” rationality, which is an entirely theoretical concept, but instead want to overcome cognitive biases and improve the inclination to make effective decisions towards goals by understanding and learning to use human motivation and attention. This skill is called “applied rationality.”

Lest you protest that the difference between man and robot is the reason we aren’t living in an over-regulated dystopia right now, the CFAR doesn’t want to forgo what makes us human. Intuition is just as important as logic, and rationality, by their definition, means learning how to use intuition and analysis in tandem. The point where there is still something to learn comes from a lack of knowledge about when intuition rather than analysis is appropriate, and vice versa. Rationality can help to keep upsetting emotions in check by limiting “cognitive distortions,” which lead to all-or-nothing thinking, jumping to conclusions, and focusing only on negatives. What’s more, it can also help assess when changes to habits and thought processes can actually be made, as opposed to worrying about things that are beyond your control.

Rationality means learning how to use intuition and analysis in tandem

Salamon and her associates implement these rationality theories through workshops (priced at $3,900) that they hold at their facility in California as well as occasional ones in New York and Melbourne (though they hope to expand geographically.) They also provide something called the “Credence Calibration” game, which, in as simple language as possible, attempts to take a claim like “I’m 75 percent sure about variable x” and make sure that you are actually 75 percent sure about variable x. Credence levels give other people a gauge to know how much to trust you, and a test like this can avoid false claims of “I’m 90 percent sure” leading people to be misled.

(A Sidney Paget illustration for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories in The Strand magazine, September 1893)

If all of this seems a bit too theoretical, fear not. The CFAR provides a handy “Checklist of Rationality Habits,” in case you want to begin this training without the plane ticket to Berkley. The list, split up into six sections, covers questioning your own beliefs, dealing with stress and confusion, and forming new behaviors. If the concept of training rationality still seems overly mechanical, this grouping of habits should sound much more familiar. Anyone can recognize when a mental debate between two sides of an argument becomes skewed in favor of one, and most people know that they occasionally condition themselves against tasks that they don’t want to repeat. Which of us hasn’t prolonged an awkward phone call, or pushed too close to a deadline, or ignored something that desperately needed doing because other things were “more urgent”? It’s those little things that the CFAR is trying to overcome; we still have a long way to go before we get “too” rational.

Check out the CFAR’s goals and upcoming workshops on their website.

H/t Motherboard

Header image by Anna Riedl for CFAR

The post Teach yourself to think more like a computer appeared first on Kill Screen.

Homefront: The Revolution is everything wrong with America

By the most recent estimate of the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), there are just under 300 non-governmental militias active in the United States. Though the specifics of their agendas vary, their shibboleth is what’s often labeled “insurrection theory,” the supposed right of the body politic to take up arms against tyranny, no matter its source. What constitutes tyranny is rather open to interpretation—one group, Posse Comitatus, rejects the validity of both fiat money and driver’s licenses, along with more familiar grievances about income tax and gun control—but, in every case, there is a common antagonist: an overbearing, conspiratorial government intent upon suppressing the “freedom” of the American citizen.

Such groups are rarely taken seriously in popular media, and rightly so: virtually every militia associated with the so-called “patriot movement” espouses, implicitly or explicitly, some version of white supremacism as an integral component of their ideology (the SPLC attributes the growth of these groups since 2008 in part to “an angry backlash against non-white immigration …and an African-American president”). Their sense of “freedom,” such as it is, is highly selective, keyed to the tradition of white dominance that is threatened by an increasingly diverse nation. But the fantasy of open rebellion is potent and pervasive, not least of all because revolution sits squarely at the center of our myths of national origin. As a result, especially in videogames and in film, there exists a genre of works that center on “ordinary” Americans rising up to recover “freedom” from the hands of occupying foreign army, enacting the lurid dream of far-right militias against a less-treasonous foe than the federal government.

It’s this tradition that gives us Dambuster’s lamentable Homefront: The Revolution, the sequel to THQ’s Homefront (2011) that neither critics nor players asked for. Homefront was, in many ways, a ludic adaptation of Red Dawn (1984), a classic piece of Cold War cinema that was recently remade, though not well, to reflect a new era of political boogeymen. In Red Dawn, a high school football team from the fictional any-town-every-town of Calumet, Colorado arms itself to usurp invading Soviet, Nicaraguan, and Cuban armies (the original Homefront takes place in Montrose, Colorado). Homefront: The Revolution’s designs, though, are somewhat more ambitious: we’re now in Philadelphia, and therefore re-performing the myths of the American Revolution, piecing together an ad-hoc resistance to depose a technologically superior foe. In Homefront: The Revolution, this means doing things like “liberating” surveillance drones in the name of American “freedom,” a task presented to the player with no apparent sense of irony.

In fact, just about everything in Homefront: The Revolution is painfully stupid. The speculative fiction that sets up the events of the game falls well short of coherent, and much less believable, but it has something to do with the national debt and an overreliance on foreign products produced by that titan of industry, North Korea. Occupied Philadelphia is a strange place, with arms dealers who operate in plain sight of security forces, and security forces whose effectiveness is greatly reduced by their apparent inability to walk up stairs. Most of the game is spent sneaking around/running from/shooting at North Korean patrols, sowing discontent among an ungrateful populace, and enduring the witless bits of phatic dialogue from your psychopathic allies, many of who sport Boston accents of dubious provenance. “Yeah, fuck ‘em up! Fuck ‘em up! Fuck!, etc.” one spouts, apropos of nothing, as you fumble through a crashed subway train, scanning for the components of a pipe bomb with which to fuck them up.

The ironies—OK, idiocies—of Homefront: The Revolution are so rich and so pervasive that, at times, it’s hard not to think that you’re part of an elaborate satire. The occupying Korean People’s Army (KPA) has divided Philadelphia into three zones—red, yellow, and green—the last of which is the seat of the KPA, who, of course, have made Independence Hall their headquarters. If the “Green Zone” rings a (liberty) bell, it’s because it was also the name given by the Coalition Provisional Authority to the heavily-fortified International Zone of Baghdad, where was overseen disastrous “reconstruction” of Iraq. For a moment, it seemed like Homefront: The Revolution might draw a parallel between two occupying forces engaged in a process of “nation building” in the name of liberty (Operation Enduring Freedom, even now, remains the official name for the global War on Terror). But then one of your bibulous companions barks out something like “the fucker is trying to sell us out to the Norks for a bowl of rice!” or any other of the game’s juvenile, jingoistic clichés, and whatever self-awareness Homefront: The Revolution might have stood upon the verge of dissipates like so much dust tossed up by a desert storm.

this mythic freedom sounds hopelessly uncritical and plainly ignorant

At many points, Homefront: The Revolution begs comparison to Ubisoft’s The Division, another recent open-world game premised on the breakdown of an American society undone by its greed. Beyond genre, both games are centered on relentless political violence against targets who can be gunned down in the street with little guilt, and less questioning. But the methods by which they justify their premise and the killing it entails diverge in telling ways. As Kill Screen’s Gareth Damian Martin wrote in his review of The Division, the game tees up a trinity of “soft political targets”—rioters, looters, the urban poor—whose disrespect for property marks them for summary execution by the player, the sharpened tip of the neoliberal spear. Homefront: The Revolution’s justifications are equally vile, but in different ways: ask your sociopathic resistance lackeys what they’re fighting for, and in between boasts about disfiguring and dismembering captured security forces, they’ll give you exactly one answer: freedom.

Right!

But what exactly does “freedom” mean in Homefront: The Revolution? How does this particular band of revolutionaries define it, and how did they come to agree upon this definition? Who does this sense of freedom serve, and in what ways? Alas, the dozen or so resistance fighters who offer their thoughts on the justifications for their armed revolt are stupefyingly inarticulate. To them, whatever “freedom” means is so obvious and transparent that it’s not even worth questioning. Freedom, to them, belongs to what Roland Barthes called “myth,” a form of depoliticized speech that places a concept beyond reproach, invoked not to open up debate but to shut it down. Put in these terms, this mythic freedom sounds hopelessly uncritical and plainly ignorant, but this exact discourse of “freedom” has a history and a politics, that weaves through our national past, from the conflict Homefront: The Revolution purports to restage, to the birth of the postwar economy and suburbanization, to the vile right-wing militias of our present day.

It shouldn’t surprise you to learn that, like Homefront: The Revolution, the militia groups associated with the “patriot movement” also dredge the American revolution for their rhetoric (“don’t tread on me,” etc.) and iconography (Uncle Sam, the 13-star Betsy Ross flag, etc). The Three Percenters, one of the dozens of militias founded within weeks of Obama’s election, takes their name from the spurious apocryphal claim that the Continental Army constituted only three percent of the American population circa 1776. One now-defunct anti-communist organization labeled itself the Minutemen. These are, of course, very selective interpretations of history—it takes some serious historiographical gymnastics to reimagine colonial partisans as defenders of industrial capitalism—but history only exists as interpretation, and so is told and retold, made and made anew by our representations and uses of it. Videogames are no exception.

I’ll come clean here—frankly, I don’t give a damn whether or not Homefront: The Revolution is fun (it’s not), or whether it improves upon its mundane-but-competent predecessor (nope), or if it adds anything new and meaningful to the overstuffed genre of near-future military shooters (absolutely not). What matters to me is how the game wields the worst, most one-dimensional caricatures of American history to explain (or not) the “freedom” that’s apparently worth torturing and stealing surveillance drones for, thereby subverting the very principles that make a democratic republic worth defending. But most of all, I’m concerned about the ideas this corroded sense of our national past can launder. At minimum, it gives us mediocre videogames; at its worst, it enables groups like Posse Comitatus and Oath Keepers, who veil their most repugnant, openly racist ideologies behind an untroubled discourse of “freedom” propped up by ignorant productions like Homefront: The Revolution.

History is inescapably pliable, but the appropriation of the American revolution as the gold-standard of American freedom by borderline treasonous, openly racist militias of the present day is especially pernicious. What’s at stake for so many “patriots” is their particular understanding of freedom, a “freedom” that’s threatened by the fear of a black president, gun control, fiat money, and non-white immigration. This is, in other words, a selective idea of freedom, and so only available to a selective few. Put bluntly, the problem with Homefront: The Revolution is that it largely reproduces this laughably ignorant notion of “freedom” that enables most rancid aspects of the patriot movement. It is a freedom for some, premised on, and at the expense of, the oppression of others. And though it’s true that Homefront: The Revolution is nowhere near as vile as anything that spews from the hateful maws of the “patriot movement,” let’s not confuse moderation with neutrality.

Homefront: The Revolution chokes on the myths of freedom and progress that excuse our nation’s most shameful episodes, and then it begs for more. Just one example: as you pick away at the Korean People’s Army, you eventually make your way into their “Green Zone,” Philadelphia’s monied, historic center. In the hours leading up to your incursion, the game positions its liberation as your ultimate goal, as if those pristine green spaces, immaculate facades, and light-soaked lofts have been the beating heart of American freedom all along. And, for some, they were. In the 1950s, homeownership was inseparable from both citizenship and patriotism, leading the real-estate icon William Levitt to declare that “no man who owns his house can be a communist.” But there’s a dissonance between the myth of the “white picket fence” and the politics of its era: owning and maintaining property might have been a sign of American freedom, but it was not equally available to every citizen. Black veterans of World War II were systematically denied access to low-interest, federally-backed loans, excluding them from the largest wealth building in American history. “They fought to save the world from tyranny,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes of the 1.2 million black Americans who served in World War II, “only to find that tyranny had followed them home.”

the myths of freedom and progress that excuse our nation’s most shameful episodes

But tyranny had been there from the start. “America,” Coates continues, “begins in black plunder and white democracy, two features that are not contradictory but complementary.” Even as the Continental Army fought to expel the British for the sake of American liberty, the nascent nation enriched itself through the exploitation of the enslaved. In American history, oppression is not the exception of the nation’s promise, but rather its rule. That a slave owner could sincerely state “all men are created equal” reveals just how perverse a refusal to question the terms of “freedom” can be. By extension, the empowered who benefit from this exclusionary sense of liberty have an incentive to keep it unquestioned—it is of no surprise that the militias that popped up in the wake of Obama’s election, those who champion the cause of an unexamined “freedom” so loudly, are overwhelmingly white.

A more competent game than Homefront: The Revolution might have used the caricatures that form your inner circle—the archetypal white-dad-action-hero, the sadistic pseudo-goth head of intelligence (read: torturer), the milquetoast white-collar collaborator, etc.—and explored what the freedom they’re fighting for means to them. But Homefront: The Revolution is anything but competent, and most of your allies simply cry “freedom” as background to your gunplay. The lone, dissenting voice among your lackeys is the the group’s doctor, who is concerned that all your rabble-rousing is making life worse for the resistance and the general populace alike (not an unreasonable claim). His reluctance to convert his clinics to weapons depots might have prompted some much-needed moral reflection about the events of Homefront: The Revolution, except that the doctor loudly proclaims that he, the game’s most prominent black character, would sooner be a “good man enslaved than a monster in the name of freedom.”

Above all, the problem with Homefront: The Revolution is that it, like so many others before it, presumes that whatever freedom is is obvious and transparent, and so can simply be acquired in a transaction like any other. But freedom is not earned: it is discovered and rediscovered, its meanings continually renewable as history lays the conditions for new and more ways of being in the world. As SCOTUS’s Justice Kennedy put it in his majority opinion legalizing same-sex marriage: “The generations that wrote and ratified the Bill of Rights and Fourteenth Amendment did not presume to know the extent of freedom in all its dimensions, and so they entrusted to future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning”. When we pretend, as Homefront: The Revolution does, to know what “freedom” is in advance, when we take the past not as our guide but as our warden, not as our shame but as a prison built of blind pride, we will always be the weaker for it.

Perhaps it’s unfair to expect that Dambuster, a British studio funded by the Austrian publisher Koch Media, would know these histories. And, sure, it’s hard to lay the blame at the studio’s feet; Homefront: The Revolution was sold off and passed around nearly a half-dozen companies over the course of its tortuous five-year development, and so it’s a challenge to say who is really responsible for this mess. If the tone of the game feels schizophrenic and ill-considered, it’s hard to imagine that’s a coincidence. But here’s the thing: the myths that animate the events of Homefront: The Revolution are both familiar and pervasive, and therefore represent a “default” way of thinking about American history. Their inclusion represents not a decision made, but something fallen back upon; not choice, but its opposite. The hapless writers at Dambuster are just along for the ride, swept up in the swift flow of history.

It’s long past time to choose something better.

In 1980, frustrated by the onanistic textbooks of his day, the dissident historian Howard Zinn published A People’s History of the United States, a veritable declaration of war on American history as it had been written and taught. Zinn’s American history is an Manichean parable of the (good) people rising up against the (evil) elite, written from the perspective of the marginalized voices sanitized or silenced by the teleological whitewash of untroubled progress and freedom that passes for history in most classrooms. Though more mainstream historians complained that Zinn’s history was hopelessly biased, they could hardly pretend that their own histories were not. All histories are partial, and so writing or using history is always a political act. The past may live on in the present, but history lives on as the present. And everywhere is someone’s homefront.

It was 13 years after A People’s History of the United States that Zinn published his fiery, iconoclastic autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train. That phrase echoed throughout the empty hours of Homefront: The Revolution I willed myself to suffer through. This game will slip drones over your eyes and stuff bullets in your ears. It will carry you from skirmish to sortie to subterfuge, assuring you that, as long as you’re shooting, you’re in the flow of progress. You can’t be neutral on a moving train; so Homefront: The Revolution marks the truth in its ubiquity.

You can’t be neutral in a fucking game.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Homefront: The Revolution is everything wrong with America appeared first on Kill Screen.

May 24, 2016

[Sponsored] Man Beaten with Own Leg in Back Alley

Fear piques in post Panchaea era.

The fear over the augmented community has boiled over into the streets, as evidenced by this video footage which shows an argument turning into a brutal fight. Unlike the Panchaea Aug Incident, the humans took this round, as a beast of a man ripped off an Augs leg and used it to beat him. “There is reason to be concerned,” says AugAware.org, the organization responsible for releasing the footage. The AugAware.org website seems to indicate that their anti-Aug awareness campaign is just beginning—check the site on May 26th to see what’s next.

The post [Sponsored] Man Beaten with Own Leg in Back Alley appeared first on Kill Screen.

Digitizing your ex: How men are using RPGs to cope with breakups

Videogames are a medium often used to escape the cruelties of reality, fostering a safe place for players to take a load off and step into a world that is familiar and comforting. Using a digital space to cope with complex situations or emotions isn’t a new concept, but it seems that some users are taking to the environment of RPGs in order to deal with their break ups. More specifically, Cecilia D’Anastasio of Motherboard explains how men are digitalizing their exes and placing them in games to be downloaded and shared among the modding communities.

Cited as both a coping mechanism and a painful reminder of what they lost, D’Anastasio gives further insight as to why men would create a digital likeness of their exes: “For some, using an avatar of their lover, or at least interacting with their digital incarnation, is a benign way to get more into a game, or even add a fun dynamic to their real-life romance. Others, it turns out—the majority of whom are men—enjoy the thrill of subduing and controlling avatars of lovers past.”

used in whatever way the player wishes to utilize her

Playing as a partner or ex-lover could create unforeseen complications. Modders can create a digital incantation of their previous girlfriend and advertise them in a way that is appealing for other users. After the initial download, the digital girlfriend is free to be used in whatever way the player wishes to utilize her. In the case of Natalie, the digital embodiment of The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011) modder “HarrisModifications” ex, she has been downloaded 10,289 times. She can be persuaded to follow the player around the open world or stay at home and occupy herself. According to Harris, Natalie was “100 percent fine” with him uploading the creation.

(Image: Jacqueline Trudeau and her husband in Second Life, via Motherboard)

D’Anastasio writes in her article that evoking an ex-partner in a game could not only be used for managing breakups or adding to an already existing relationship, but can also be used as a vessel to explore activities and concepts that wouldn’t translate well into real life. D’Anastasio interviewed Second Life (2003) user Jacqueline Trudeau, who says that she uses her husband’s likeness for promotional photos when advertising her business of selling highly-detailed yachts. “Trudeau’s husband can be seen in-world wearing tight-fitting swim trunks and wraparound sunglasses, which, she explains, would never happen outside of the virtual world.” Trudeau goes on to say that placing her husband within this digital space is a way of getting him to come out onto the boat with her, which would be impossible otherwise due to his seasickness.

Read through D’Anastasio’s entire article on men playing as their exes in RPGs here.

The post Digitizing your ex: How men are using RPGs to cope with breakups appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers