Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 111

June 6, 2016

Here it is, the farting Daniel Radcliffe game that dreams are made of

When the flatulence-filled Swiss Army Man screened at the Sundance Film Festival, it was polarizing, to say the least. It even prompted a multitude of disgusted filmgoers to leave the theater, what Variety described as “could win the festival’s award for the most walk-outs.” The divisive Swiss Army Man is the feature film debut from the quirky filmmaking duo Daniels. The film itself stars Daniel Radcliffe (another Daniel) as a farting corpse with strange magical abilities, and Paul Dano as his suicidal, but very much alive, companion. As a part of the film’s marketing, an interactive version of Radcliffe’s ragdollian, ever-farting corpse is draggable across the film’s website.

The best way to accentuate the weirdness of the film itself

The Daniels, Daniel Scheinert and Daniel Kwan, got their start directing unconventional shorts and wild music videos. Absurd humor and inventive, dramatic visual effects became a staple for the directing twofer, culminating in the face-melting music video for DJ Snake and Lil Jon’s party anthem, “Turn Down for What.” Eventually, the Daniels embarked on a brand new adventure: writing and directing their first film. “Honestly, the only thing we were trying to do was start a movie with a fart joke and end the movie with a fart that makes you cry,” explained Kwan in an interview with Rolling Stone. And thus, Swiss Army Man was born.

Given the film’s jarring plot (in which Dano escapes a deserted island by riding on a farting boat-like Radcliffe) and the role of Radcliffe himself, this approach to marketing game-making makes complete sense. Its interactivity is a bare-minimum, you can drag Radcliffe’s “Manny” across the screen, his limbs flailing everywhere. You can text “buddy” to the number Manny tells you, as he spits out words that are typable within the game’s interface.

“I don’t know what DREAMS are but I bet they are nice,” read the automated text I received. And by typing “dreams,” everything in my browser’s peripheral became floaty. Typing “compass” gives Manny an erection (which, as it turns out, is actually a plot point in Swiss Army Man itself… perhaps unsurprisingly). Swiss Army Man’s browser game companion is maybe the best way to accentuate the weirdness of the film itself. Giving additional flavor to the otherwise bizarre abilities that Radcliffe carries in the movie, and showcasing them in a fun, interactive fashion beyond just watching the film itself.

You too can make Daniel Radcliffe fart, karate chop wood, become a human water fountain, get an erection, and wear a party hat right in your browser on the Swiss Army Man website . Swiss Army Man will be released in New York and Los Angeles on June 24, before going to nationwide theaters on July 1.

Via The A.V. Club

The post Here it is, the farting Daniel Radcliffe game that dreams are made of appeared first on Kill Screen.

The prison of the videogame camera

Techniques such as lens flare or liquids splattered on the camera (usually blood) have become so commonplace in videogames that we no longer pay attention to them. This indifference is a bit disquieting. After all, with videogames, we play two roles at once: the character on the screen, and ourselves in our own body viewing the screen. We act by pushing buttons and at the same time passively watch those actions performed by somebody else through the distancing filter of a camera lens. We accept this double perspective so wholly that in our minds it seems to become one. When blood splats on the surface of the camera in Red Dead Redemption (2010), the effect is that of immediacy, as if the liquid was really there, and we could almost feel it by touching the screen. And yet, at the same time, we are reminded that the screen is always present. Paradoxically then, the greatest immediacy is achieved by revealing the intransgressible barrier of the camera lens. Moments such as these prove that immersion, perceived by the player as the synthesis of game character and physical body, would be impossible without the mediation of the camera. After all, if this blood reached our face, our engagement with the game would be interrupted.

There is no way that we can truly push aside this mediation. Some see such a possibility in virtual reality due to it attaching the camera to the player’s face—the gap between realities tighter than ever. But we cannot truly escape the duality of our role when playing videogames. To do so would either mean to watch without participating, in which case there is no game, but film instead. Or you would fully participate and have to accept that your actions have real consequences, not just virtual ones. And so we are trapped in a limbo of unreality; between the virtual and the real. This impasse cannot be resolved. But it can be exposed. And this is what two games, L.A. Noire (2011) and Outlast (2013), achieve in different ways.

The world of L.A. Noire exists for the sole purpose of being captured on camera. This isn’t just a figure of speech related to the fact that Los Angeles is home to Hollywood. On the contrary, in the game, the roles are reversed. Los Angeles is subsumed into the film-making machine. For instance, some of the most climactic events of the game take place on a set built for D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916). Looking at a model of this set, the protagonist Cole Phelps says that it’s a replica of a replica. However, we, the players, know better. This model is a virtual replica of a replica of a replica, to be replicated yet further by our camera. Plus, it is a replica of something that did not exist. In reality, the set had long been dismantled by 1947, when the game takes place. It’s hard not to find irony in the existence of this building amid an historically accurate representation of post-war Los Angeles. This set, then, is an explicit fissure in the texture of the world—an ominous presence whose distance from reality, and its origin in cinematic fiction, makes us aware of the illusory nature of this ostensibly realistic world.

Actually, the game itself rips this texture apart. The Intolerance set is a mere teaser to a cinematic apocalypse. A considerable part of the game’s virtual Los Angeles is going to be destroyed and turned into one big film set. As we explore the city, we are haunted by the ubiquitous logos of the Suburban Redevelopment Fund and Instaheat. Innocent enough. Only retrospectively, by the end of the game, we realize that they are portents of a disaster. Suburban Redevelopment Fund is buying out land and building artificial houses using materials from Hollywood studios. If somebody refuses to sell their property, a brand new heating system, installed virtually in every household, is used to burn this property down. Almost every single important person in the city takes part in this plot. In the game this fraud is explained in rational terms. Considering, however, that it connects with the themes of film, advertisement, and imitation pervasive throughout, and that it frames the entire space and narrative, thinking about it in terms of how it relates to the real world would miss the point. This plot is supposed to makes us realize one crucial thing: the virtual Los Angeles is a hell of non-existence, a repository of images with no reality behind them.

the city is nothing but images

Since L.A. Noire’s city exists only as a set of images, it would cease to exist if there were nobody to see them. And the main role of the player is exactly this: to watch. We spend a lot of time driving from one place to another and watching the city pass by like a rear projection, a stream of constantly self-effacing images. But this tridimensional rear projection is everywhere and cannot be escaped. If we want, of course, we can stop for a moment and enjoy the landmarks. Enjoy, of course, meaning to watch. Like a tourist. Because we are tourists in this world, consuming its nicely rendered sights. Significantly, a majority of the game takes place in daylight. After all, postcard pictures, into which the landmarks are turned into after being framed by the player’s camera, could not be watched without light. The intense, overwhelming lighting is supposed to blind us to the fact that the city is nothing but images.

Night is also present in this world. But this is not real night. It is the stylized night of a movie scene, with inspirations ranging from noir classics such as Act of Violence (1948) and The Third Man (1949) to neo-noir reinterpretations of the genre, such as L.A. Confidential (1997) and The Black Dahlia (2006). Night here is used only to create a cinematic atmosphere. But this cinematic atmosphere transpires at every moment of the game. To begin with, we are detective Cole Phelps, L.A.P.D. We search for clues, interrogate, shoot, and chase. But, what is crucial, we simultaneously watch ourselves search for clues, interrogate, shoot, and chase in an enactment of our cinematic fantasies. However, we do not have control over these fantasies; they have control over us. We are forced to act them out in order to consume them. We are consuming our own actions as images, so it is obvious to us that these actions cannot have any consequences. But we are in a privileged position because we can turn off the game at any moment. The characters, including the avatar, do not have this privilege. They are trapped in the position of simultaneous acting in the sense of doing things, and acting in the sense of existing for the sole purpose of being turned into an image. Even, or especially, when they do something foul, it is still only an enactment of a scene we have seen hundreds of times before in cinema. You can lie, steal, and murder—but no worries, it’s never for real, it is all in the script. And when you die, your corpse can provide a stylish noiresque spectacle. Nothing escapes the all-fictionalizing camera.

This would not mean anything as many games consist of scenes taken from the common stock of genre cinema. L.A. Noire, however, goes a step further and self-consciously inscribes into its narrative and structure the entrapment of the characters in cinematic fiction. As we can guess, they are not happy in their state of nonexistence. Why are they unhappy? Because their actions carry no weight. If all responsibility is removed exactly at the moment when an action, or its account, is caught on camera, the characters will futilely try to repeat what they did in order to acquire at least a momentary sense of agency. This leads to compulsion, the constant repetition of a self-effacing action. That is why the game is driven by themes of addiction, serial murder, arson, all based on repetition. More interestingly, however, this is visible in the structure of the game. The game consists of cases only loosely connected by the main plot. They are related mostly on the basis of repetition. The repetition of the murder weapon, a particular place, the modus operandi, etc. Once the case is finished, it’s finished; it has no consequences later on. And if we haven’t got enough, there are yet more inconsequential cases available as DLC. For instance, the murder cases revolve around the story of The Black Dahlia. Contrary to the real events, in the game there is not one victim but five. And there could easily be more or less, as there is no continuity between them apart from repetition. The killer is clearly stuck in a loop of irrelevant actions. No matter how many murders he commits, they are immediately reduced to cinematic fiction; even his death takes place in a highly atmospheric setting of a church and its graveyard, just as the camera likes it.

This structure may also be said to have a simplified psychological explanation connected to the protagonist’s past. Cole enacts his guilt from the war through compulsive action. He keeps condemning people guilty of minor crimes, and often of no crimes at all or at least not the crimes they are accused of, as he cannot face the real criminal: himself. By the end, he confronts the past with the help of a third party, Jack Kelso, and it is only at this moment that the main storyline, told in retrospective cutscenes, starts to connect with the content of the cases. Only the last cases have some continuity. After facing the past, Cole dies, in this way interrupting the loop of his compulsion. The more brutal truth, however, is that even the psychological reality of the game is built on the spectral foundation of film clichés. After all, many renowned directors, including Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, and Alfred Hitchcock, used psychoanalysis and psychiatry both as an explicit motif and to structure their narratives, and L.A Noire simply alludes to this convention. The game, however, adjusts this structure to the requirements of providing long hours of entertainment by focusing on compulsive repetition. After all, this world exists only in the present. It is neither a place for psychological depth nor for confrontations with the past; even the most deeply buried traumas are turned into images here. This virtual Los Angeles exists in the presence of the camera, and it has no right to exist when the camera is turned off.

built on the spectral foundation of film clichés

Outlast takes the opposite approach. It focuses not on what is in front of the camera but on the camera itself. Ironically, its protagonist, Miles Upshur, is a journalist—somebody whose role is to treat the world as if it were a repository of images. He thinks that nothing can touch him as long as he is protected by the magic lens, just like a videogame player. To emphasize this illusionary distance, we start the game in a car, protected by the windshield. Like L.A. Noire, with its city as a tourist attraction, Outlast promises us a safe thrill ride through a horror movie-based theme park. And this is what we get. However, this time there is a twist. Through the safety of the camera we get to see what would happen if the monsters broke the unbreakable rule and attacked the cameraman.

The avatar of Outlast carries a camcorder. When it’s on, the screen switches to a low-quality handheld cam aesthetic, which in cinematic vocabulary connotes realism. Outlast exploits a crucial flaw in this technique. Namely, even though this aesthetic is meant to convey a sense of immediate contact with reality, it still relies on a camera: an unbreakable shield granting immortality to the person who holds it. The camera can show exploding buildings, bodies torn by bullets, and other symptoms of infernal mayhem, but it itself can never be broken. That would mean the destruction of the film. Even during an apocalypse the camera would remain invincible. This pursuit of realism paradoxically fulfills the unrealistic fantasy of immortality. This is what we expect when we turn the camera on in the game. And it’s due to this very expectation that we feel so uncomfortable when the camera gets broken and our avatar’s head torn off. Just as children might think that looking away is enough to make the danger disappear, we want to neutralize the monster through the camera lens. The horror of Outlast is based on this contemporary iteration of a primal fantasy.

As I have already mentioned, L.A. Noire relies, broadly speaking, on two kinds of light: the oppressing, inescapable daylight turning the city into a set of postcard photos; and the night of stylish noiresque images. Outlast does things differently. It plunges us into impenetrable darkness. Literally impenetrable as we cannot really move without getting stuck on the nearest wall. If we want to see anything, we have to use night vision mode on the camcorder. In L.A. Noire, the world exists for the camera, but in Outlast our interaction with the world is dependent on the camera. And this interaction is explicitly about avoiding interaction. We are to record as much as we can of the asylum we’re trapped in without being seen ourselves, as being seen can mean death. This is, again, a reversal of the situation in L.A. Noire, based on the irreducible distance between the camera and the world—irreducible because L.A. Noire’s world owes its existence to this very distance. In Outlast, the world exists apart from the camcorder. The avatar has to use it in order to see, so it is he that would cease to exist without the camera. But there is no denying the fact that the camera and its user are only fragile objects in the world of oppressing physicality and carnality.

L.A. Noire turns its world into a set of images. Everything that happens there happens for the camera. Outlast, on the contrary, gives even the most intimate and elusive images a palpable reality. In order to understand this contrast better it may be worth taking a look at the role of psychiatry in both games. In L.A. Noire, one of the main antagonists is a psychiatrist. He takes part in morphine trafficking in order to keep people safe in the state of cinematic unreality, or perhaps prevent them from the realization of the fact that they are already in such a state. Apart from that, he uses the war trauma of one of his patients, whose destructive urge is meant to help in the aforementioned project of turning Los Angeles into a film set. Outlast takes place in an asylum. The story revolves around an experiment meant to exploit the patients’ mental images in the creation of a creature called the Walrider. This experiment, however, not only brings Walrider to life but also physically deforms the patients and the doctors. Contrary to L.A. Noire, in which even the darkest recesses of the human psyche are turned into self-effacing images, Outlast turns every image into flesh.

our interaction with the world is dependent on the camera

Well, not every image. There is one crucial image that cannot be turned into flesh. The image seen from the player’s camera. The one camera that can never be turned into an object and destroyed. Even when the avatar’s head gets torn off, we still see this performed. Outlast plays out our fear and fantasy of total immersion, that is, a direct experience of the game reality, by showing what would happen if the magic lens were to lose its invincibility. But this makes all the more pertinent the realization that, in fact, this is yet another horror story—built on the most overused images—to be experienced from the split perspective that has us both acting (in the game) and observing. L.A. Noire, on the other hand, gives us a detailed open world with every pretension to so-called “realism,” only to start hinting that perhaps this realistic city is nothing more than a set of images. In both cases there is no escaping the camera.

Header image: Monday March 25, 84/365 by Evan Blaser

The post The prison of the videogame camera appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 3, 2016

PLLUG plays with light and dark to tease out your curiosity

Everything is enveloped with darkness. You are a creature that thrives on electricity. You fall into a strange underground world; separated from your loved ones, you must find a way to get back to the surface. This is the premise of the game PLLUG, created by carpetbones. With simple keyboard controls, you wander around a maze-like landscape, encountering other strange creatures, and must absorb energy to keep your surroundings lit up in order to make your way home.

each nook and cranny takes on an element of interest

Development of PLLUG started in 2013 and although much of the art was completed early on, carpetbones hand-placed over 12,000+ blocks in this project. While this sort of repetitive labor and attention to detail is hard to imagine, it really shines through in the world itself. With the mushrooms, grass tufts, vines, chains, rocks etc. which ornament the different types of blocks, each nook and cranny takes on an element of interest.

Exploring the different parts of the underground is a work of trial and error because of this, where being lured to a new corner may lead you inadvertently back to where you came from, or into a dead end, only to realize there was nothing of real value there. Although this happens fairly often in the game, it all feels a part of getting to know the world better, rather than being a frustration.

Sound is an important part of PLLUG. The most obvious part of this is its varied and ambient soundtrack by rabbitgirl, which ranges from soft and gentle, to eerie and ominous, depending on the areas of the underground you’re exploring. However, the sound design of the world itself is also quite noticeable. For example, when you walk through flowers scattered across the levels, they give off a chord each time you pass. This makes the flowers feel significant somehow, and part of a larger mysterious world. These types of small details give the underground life.

There are other elements of the game that hint at further mystery, such as the strange creatures you come across on your journey, some of which give you quests, non-verbally through means of symbols, and others who simply occupy the world quietly. There is also the strangeness of the technology — how initially you absorb energy mainly through lone lampposts, surrounded by old stone blocks and rickety bridges, and later come across street lights and blocks and architecture which seem more advanced. These differences allude to a rich and unknown history of the underground and its different spaces.

Without any voiceover or text, PLLUG‘s narrative and world remain mostly obscure. However, the detail of the world and its inhabitants allow for a player to fill in the gaps and make their own conclusions. Finding your way through the dark, with varying levels of light, makes vision a commodity here that allows a player to more appreciate what they do see. Unlike many other games which employ darkness to evoke horror, PLLUG‘s darkness evokes curiosity. Despite its short play time of around half an hour, there is a lot to be found in the underground depths of PLLUG.

You can download PLLUG on itch.io, and keep track of carpetbones and their work on Twitter

The post PLLUG plays with light and dark to tease out your curiosity appeared first on Kill Screen.

Find angst and beauty in 35MM’s post-apocalyptic Russia

In 35MM, post-apocalyptic Russia plays you. You are one of a pair of friends walking across deserted Russian villages and forests. It’s not entirely clear what befell the world, but it was bad. The people are gone, and so too are most signs of life. More to the point: most signs of life as you commonly understand them are gone. The earth is adaptable and has moved on to new challenges since whatever foul event occurred. It is changing, and you can’t be exactly sure why or how. If you are to survive, you, too, must change.

That’s sort of a mystery. There are definitely questions to be answered in 35MM and challenges involved, but that doesn’t make the game a mystery in the conventional sense. When all signs of life are lost and the world is changing around you, mystery becomes existential angst, a series of questions about your place in the universe that can’t really be resolved by sleuthing alone. In narrative terms, however, it’s still a plain old mystery. 35MM plays with the hybridity of these different forms of suspense.

Some things have not been destroyed, and that is what you must deal with

What role does setting play after the apocalypse? If all that we know is gone, do the nation state’s geographical associations really matter? (In international law, as in space, nobody can hear you scream.) Put otherwise: 35MM takes place in something approximating Russia but Russia is no more, so which is it?

There are plenty of games in the post-apocalyptic somewhere—Everybody’s Gone To The Rapture (2015), for instance—and they all have an uncomfortable relationship with place. What’s left of the fictional village of Yaughton, in Shropshire, England, is still very English, and that tension is of narrative value. Some things have not been destroyed, and that is what you must deal with.

Likewise, 35MM isn’t really trying to outrun Russia’s past; clips of deserted apartment buildings in promotional footage look an awful lot like Chernobyl. This is, admittedly, an interpretation informed by hindsight bias, but the whole point of hindsight bias in this case is that we only have so many disasters to work off as precedent. If everything—all ruins porn, all post-apocalyptic gaming—looks something like Chernobyl, a place most will never truly experience in this lifetime, it’s because we have limited practice imagining the apocalypse. In 35MM’s eerily recognizable beauty, then, lies its own form of existential angst: a life that is recognizable but also largely after life as we know it. Good luck with that.

You can purchase 35MM on Steam.

The post Find angst and beauty in 35MM’s post-apocalyptic Russia appeared first on Kill Screen.

Walk inside the dreamy paintings of a Metaphysical art pioneer

Imagine if you could visit any museum in the entire world: The Louvre, the MET, the MOMA. Any museum you’ve ever dreamed of. Now imagine again, if you could literally visit and walk within any work of art from around the world. This is a gift that Gigoia Studios has brought to life, time and again, with their fine art appreciation projects. Now realized to its fullest capacity with the fully completed SURREALISTa, a virtual, interactive exploration through eight classic paintings of Italian metaphysical art pioneer Giorgio de Chirico.

Not diminished by new technology, but enhanced

De Chirico’s work is seen by many as being an inspiration for the eventual surreal art movement, pioneered by Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst. But his dense, multi-dimensional work is seen wholly his own, and should easily be appreciated for its own merits, and not just what it inspired. In fact, the Metaphysical art movement was founded by de Chirico and artist Carlo Carrà in 1911, lasting until 1920.

Metaphysical art saw the blending of obscure spaces, sharp contrasts, and a marriage of classic Italian art with the modern. De Chirico’s dreamlike art even influenced the cover for Fumito Ueda’s cult game Ico (2001), specifically the painting The Nostalgia of the Infinite. As Ueda explained in an interview with 1UP, “I thought the surrealistic world of de Chirico matched the allegoric world of Ico.”

As Metaphysical art pushed back against Futurism’s betrayal of the past, Gigoia Studios push against the boundaries of painterly art by making it 3D and fully explorable. In making classic art more accessible, and exploring it in fresh ways (as through an interactive videogame), classic art’s longevity and appreciation lives on. Not diminished by new technology, but truly enhanced.

You can walk within the surreal art of Giorgio de Chirico for yourself on PC, Linux, and Mac here .

The post Walk inside the dreamy paintings of a Metaphysical art pioneer appeared first on Kill Screen.

How scientists are using MMOs to study sexism in videogames

For the past few years, one of the more common debates to be found on social media has been over whether women are discriminated against within videogames. This can relate to a number of factors, including skill, female presence in the community, and how women are represented within games, but conversations in these topics are often noticeably hostile and difficult to conduct. However, recent scientific studies on the topic have provided new insight into if and how discrimination presents a problem for women in and around videogames, as well as what difficulties sexism in games poses for women in tech in general.

According to a 2015 study from the peer-reviewed journal Games and Culture, two different 2014 studies from Computers in Human Behavior, and a host of numerous other studies conducted in various journals from 2004-2012, sexism against female players does indeed present a prevalent barrier to entry for women in many popular online games. Taking note of a glass ceiling of sorts, these studies argue that this discrimination tends to push women away from leadership roles in games and into support positions, and can even pressure them into outright silence through the use of harassment and stereotypes. But regardless of how it manifests, the researchers note that this discrimination is often built around and justified through one central claim: that women are simply worse at games than men.

However, according to a recent study released on the 18th of May from the peer-reviewed Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, the stereotype that there are gender-based skill disparities in online games is nothing more than a myth, and may in fact contribute to under representation of otherwise skilled women in fields related to science and technology as a whole.

The study begins by looking into the basics of gender role theory, and explains that many of the supposed gaps prior research has found between male and female players aren’t a result of innate gender differences so much as an indicator of female players being under represented in more competitive videogame genres. The researchers note that because many popular games are built around actions geared towards stereotypically male preferences, such as violence and shooting, they tend to be largely dominated by men, which may encourage women who play them to doubt their own skills and rely on help from male friends and partners instead.

This can also lead otherwise capable female players to underreport their own ability, as seen in a 2015 study of the League of Legends (2009) community, which showed that many female players often demonstrated lower confidence than their male peers despite being around the same skill level. However, the aforementioned recent study from the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (JCMC) notes that once women secure “authentic access” to these games and become familiar with them, they tend to play with just as much expertise as male players. “Gender,” it notes, “is a correlate of experience rather than the true cause of gameplay differences.”

many popular games are built around actions geared towards stereotypically male preferences

To test this, the JCMC study gathered data from two popular massively multiplayer games across two different regions and decades, and compared how quickly female players leveled up in them when judged against their male counterparts. For the West, the study looked at the fantasy game Everquest II (2004) between the period of January and September of 2006, whereas the study looked at a game titled Chevaliers’ Romance III from the period of May 2010 to June 2012 to track progress in China. To determine player gender, the study took data from the gender players used when signing up for the game rather than the gender of their character, so as to control for players who were playing across gender lines either for role-playing purposes or, in the case of women playing male characters, to escape sexism.

The results? Regardless of gender, players who played more frequently tended to perform better. In the Everquest II study, while men committed slightly more hours of total playtime than women, the difference was not considered statistically significant, and may also simply point to a greater population of male players than a lack of time devoted to the game among their female counterparts. As for character level, men did have a slightly higher level overall, but the researchers noted that this was also not statistically significant. For the Chavaliers’ Romance III study, the team also found that men and women had comparable playtimes and levels.

“Based on our data from two MMOs, there is no significant gender-based performance disparity,” they write. “In both studies, women performed at least as well as men did.” However, although the differences in the Everquest II study were statically insignificant, the team still notes that the higher overall level of male players likely has less to do with skill and more with men placing a higher value on leveling up than women. They note that when women dedicated their time to leveling, they “leveled up at least as fast as men did,” and conclude that the reason men reached a slightly higher level overall may simply be due to them having a greater interest in competition rather than a greater ability to play the game; whereas women preferred to apply their time and equal level of skill to social activities instead. “The motivational difference between genders only makes our findings more robust,” write the researchers.

In their conclusion for the study, the team notes that women who played as much as men reached similar levels, and claims that their findings show that any perceived differences in performance or game choice has more to do with cultural expectations and prior game experience than innate differences in gender skill level. Additionally, the team proposes that stereotype threat—in which a negatively stereotyped group might perform worse out of fear of confirming the stereotype—may contribute to perceived differences in gender skill level, helping to sustain the stereotype and create a vicious cycle which fulfills itself.

“In both studies, women performed at least as well as men did.”

Outside of games, the researchers note that this could have dangerous effects for women in science and technology fields, or STEM fields, as a whole. “A similarly designed study also found that gender-based stereotype threat induced in a gaming context led women to perceive some STEM fields as better suited for men than women,” write the researchers. “Together, these studies suggest that the gender stereotypes in gaming are not only false, but potentially cause unequal participation in digital gaming, thereby perpetuating gender disparity in the distribution of the many known benefits associated with gaming, such as interest in STEM fields.” Essentially, the team is noting that because videogames tend to garner interest in fields related to science and technology, stereotypes which discourage women from playing them may also discourage them from entering into these fields as a whole, making sexism within games a broader educational issue even for those who have never held a controller.

All of which suggests that, yes, women are discriminated against in games, but no, they are not worse at them than men. Rather, both the existence of predominantly male gaming communities and the fundamental way many competitive games are built creates a hostile environment which causes women to second guess their skills and conclude that games “just aren’t for them.” This not only leads to a lack of female representation within games as a whole, but because games also act as a gateway to computer science for many young players, also contributes to a general lack of women in STEM. However, as the study notes when covering an experiment in which men and women learned to make educational games, the games which were developed by women did present a more welcoming atmosphere for other female players. The hope here, then, is that as more women are encouraged to enter into game development, more women will feel as if gaming is “for them.” Just so long as they are not scared, judged, or harassed away first.

To read the full Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication’s study for yourself, visit its website.

h/t Motherboard

The post How scientists are using MMOs to study sexism in videogames appeared first on Kill Screen.

Learning from Disney to tell human stories through animal characters

Propelled by nature and elemental attributes, Quench’s tale of animal pilgrimage is actually ruled by human traits. It features a guidance system built around weather controls—tremors, wind gusts, and the like—that’s supported with flexible puzzle design.

Different actions can surmount the same hazard, impacted by herd size, enemy presence, time constraints, and manually-recharged power. There are also consequences tied to each choice—the most obvious: indiscriminate use of lightning will start fires—with subtle effects tailored to each tribe (Elephant, Wildebeest, Zebra, and others). The creators at Axon Interactive hope a philosophy of openness will pave the way for emergent applications of these actions. This quality does not extend to the story, however.

the difficulties encountered on a storytelling level are internal

A linear narrative is threaded with positive emotions and characteristics. Compassion, for example, is a driving force in the game and manifested in the role you play for the animals, mining the same principles as Shelter (2013) and its system of parental oversight but trading a physical presence for the ethereal. Less clear is how forgiveness—another major element—factors in.

When asked how this will come to the fore, producer Tabby Rose outlined that while there are external forces that stifle your journey—smokebeasts and the terrain—much of the difficulties encountered on a storytelling level are internal, where unity between tribes is not organic.

“Your primary narrative objective is gathering all these different animal tribes and keeping them together as they make a pilgrimage,” Rose said, adding that each are guided by differing value systems and goals. “The thrust of the story revolves around reframing these conflicts and the ways we resolve them.” In keeping with this, Quench concentrates its design vocabulary on peaceful methods—“mediate,” “restore,” and “forgive”—over traditionally violent proclivities—“destroy” and “kill.”

“we simply have to move past our own grudges”

Among Quench‘s multiple inspirations—including the conflict resolution of Avatar: The Last Airbender—is Disney’s 1994 classic, The Lion King. Its influence goes beyond the shared presence of an Elephant Graveyard, really serving as an overseeing aesthetic. “We drew inspiration from the broad strokes,” Rose commented, “such as the color palettes and environments, or the dark moments that left lasting impressions.”

Quench itself isn’t a dark game. In fact, the decision for a narrative bound by linearity was to prevent the game from moving in this direction. But it’s the essence of key scenes in The Lion King—Scar’s height of treachery, adult Simba seeing Mufasa in the clouds—that they’re looking to extract and recreate in terms unique to the game.

This guiding role has less to do with pulling from The Lion King‘s core themes, Rose told me. “The story we’re telling is quite different, and the medium is different,” she said. The definition may follow a different standard, but there’s a definite overlap and equivalency in the meaning they’re looking to translate. The mentorship of Quench‘s main character—a crane by the name of Shepherd—is similar to Rafiki’s role; Elephant tribe leader, Shaman, is tasked with a leadership that relates to the hierarchical structure among the lions; and a dying land and pollution caused by smokebeasts matches the oppression and ruin represented by Scar and the hyenas.

Although more prominent in the sequel, forgiveness—that of self—made up a subtle undercurrent in The Lion King, with dark ramifications blossoming from Simba’s acceptance of a lie. Prior to being torn apart through confrontation, Rafiki’s simple yet meaningful lesson on moving forward provided the agency for overcoming this internal conflict. Axon Interactive strives for similar aims with Quench. “Sometimes in order to solve a conflict we simply have to move past our own grudges and accept what’s happened,” Rose posited. “We want the player to come away from Quench feeling like they have the power and resilience to do good.”

Awakening that sense of empowerment will be the primary duty of the “idealistic” story and its humanized lessons.

You can find out more about Quench on its Kickstarter page.

The post Learning from Disney to tell human stories through animal characters appeared first on Kill Screen.

Mirror’s Edge and the politics of parkour

As world design in games nowadays trends towards visions of vast, sprawling overworlds, intricately layered and impeccably nuanced, questions of mobility have risen to the forefront: how does the player get from point A to point B in the most efficient way possible? Questions of speed are of paramount concern, of course; no one likes to be held up unnecessarily in pursuit of some arbitrary objective. But, as in any art, games too must also be concerned with not just raw efficiency, but beauty as well: it’s not enough to just get there, but to get there in style, preferably with a certain poise and elegance to one’s motion.

From this desire has emerged the rise of parkour in games. It’s exemplified by titles such as Dying Light (2015), the Assassin’s Creed series and Mirror’s Edge (2008), in which almost every action is defined through the fluidity of one’s movement. More significant than the mechanistic implications of this trend, however, are the social, and possibly even political implications: parkour, not just as a means of movement, but as a tool of freedom, of liberation, of individualized power without constraint, and limitless exploration. And ultimately, it can act as a weapon against oppression: at once symbolic and physical, a modernist philosophy of personal resistance embracing both the sky to which we aspire, and the body which holds us down.

A tool of freedom, of liberation, of individualized power

Parkour, from the French le parcours (‘the course’), is the art of efficient movement within inefficient space. In a world inundated with geospatial interference—from garbage cans to park benches to hanging gardens to fences—movement is largely confined to pre-established paths in order to preserve the semblance of communal order. Whether such paths are roads for automobiles, trails and sidewalks for pedestrians, railroad tracks for subway cars and trains, or bicycle paths for cyclists; movement in the modern world has become so rigidly defined that it has become in many places unnecessarily complex and at times, downright convoluted. Anyone who has ever attempted to navigate the public transportation system in any major American city can pay testament to this fact.

Parkour solves the problem of inefficient transportation by deconstructing human movement to its most basic foundation: movement simultaneously restricted to and liberated through the human body as sole vehicle of motion, with emphasis on individual willpower and efficacy as means of navigation. While it is very much utilitarianistic in its ambitions, it is not however altogether divorced from a physio-kinaesthetic grace and aesthetic, which very much classifies within the broad domain of art. In both its goals and its underlying philosophy, parkour fundamentally aligns with modernism in that its primary motive is the affirmation of the power of humanity over its environment, emphasizing the ability to create, improve, and utilize the environment to maximum efficiency. And indeed, there is a particularly deadly elegance to any of the various hooded eponymous assassins of the Assassin’s Creed series, for example, gliding along silently towards their targets, blades glinting in the moonlight.

The primary conceit of Assassin’s Creed, however, is that movement always carries with it a certain specific destination, and (often lethal) purpose: whether in pursuit of a fleeing target, or attempting to gain a vantage point on an unsuspecting guard, the player character’s movements are always purposeful, performed with a strictly utilitarian function. Consequently, as much as one may delight in the fluidity of the animations, and the accuracy of the actions captured, the act of navigation will always remain little more than one more component in a vast, deadly toolbox. The very mechanics of parkour in the Assassin’s Creed series reflect this as well. Movement is restricted to no more than two commands at most; one, which specifies the direction, and another, to signify a transition from a ‘normal’ state to an ‘active’ state. Rarely are players required to consider the meaning of their movements, or even the motivation behind them. They simply have to press a series of buttons to let the game know that they now want to ‘free run’ (an ironic name, given the real-world distinction between parkour and freerunning), point in a direction, and watch as their character scales, vaults, and hurls over all obstacles in the way with minimal effort. While Assassin’s Creed may have been a pioneer in bringing parkour as a viable means of in-game navigation to the public attention, it captured at most its utilitarian aspect while eschewing the grace and challenge vital to it. Consequently, it remains at best a crude and distilled approximation of what parkour actually is: a blunt tool, another trick in the assassin’s magic sleeve of lethal gadgets, no more different or extraordinary than a concealed blade thrust into the neck of an unsuspecting guard.

On the opposite side of the spectrum is the Mirror’s Edge series. Rightfully recognized as one of the first and only games to properly capture the essence of parkour, Mirror’s Edge stands as a tremendous realization of parkour as not just a locomotive gimmick, but an art form as well. Faith, the protagonist and player character of Mirror’s Edge and its upcoming reboot Mirror’s Edge: Catalyst, uses her considerable athletic prowess as a ‘Runner’ to act as a courier of compromising messages between various cells of the resistance, rather than acting as an agent of violence herself. Where her fellow resistance members seek to dismantle the corrupt forces eating away at their gleaming metropolis through a variety of infernal machinations and devious plots aimed directly at exposing them, she instead is able to resist not just the forces which oppress her (quite literally, too, in the form of the black-suited guards who show up at various points in the game), but the physical boundaries of the city itself.

parkour as not just a locomotive gimmick, but an art form

For Faith, the primary opposition to her agency is not a corrupt government, or dubious politicians, but the city itself; and not just opposition, but paradoxically her primary conduit of self-realization as well. Indeed, the aforementioned enemies and their ominous black helicopters, in the rare moments they do appear, are more cinematic set-piece than legitimate danger—their bullets rarely seem to hit, and when they do, it seems more of a programming fluke than anything else. Mirror’s Edge had very limited combat segments that, compared to the effortless grace of the actions which brought Faith into that moment of peril, felt incredibly awkward and clunky. The guns she commandeered felt not like the precise and lethal instruments wielded by her siblings in the first-person genre, but unwieldy and unreliable bricks more effectively hurled than actually fired. Catalyst promises a significantly more refined combat system integrated fluidly and inextricably into the movement system itself, which stands far truer to the philosophy behind parkour and many martial arts as well, emphasizing the effortlessness and ease of motion above brute force and muscle power. And while these changes will definitely improve the overall flow of combat, it hopefully doesn’t amount to a loss of focus on refining the overall movement itself. For while Mirror’s Edge may fundamentally be a game about resistance, it is resistance through kinesis, not violence.

The true difficulties of the game are not through encounters with human enemies, but with one’s environment, specifically the choices made to navigate it efficiently and elegantly. Faith’s ‘Runner vision’, which highlights potential paths and traversable objects in a bright, clean red, is one of the clearest indications of this: the world is seen not as a collection of individual components with separate meanings but a system of unified parts, each working in distinct and organic synergy with one another to accommodate a single purpose: movement. Catalyst will update the relatively linear chapters of the first title to a vast, open world, promising nearly limitless movement and opportunities for play. While this might be seen as the game falling for the fad of open-world titles, it is in many ways less of a gimmick and more of a highly sensible and almost necessary upgrade for this particular series. In Mirror’s Edge, an open world seemingly presents very few of the problems that plague other titles to have attempted this model. For where others require an ulterior motivation to engage with the environment (quests, collectibles, etc), which can be easily (and often are) ignored by many players, the mechanics of Mirror’s Edge dictate by their very nature that the world will only become boring if the actual mechanics become boring; that is to say, the world is not seen as a liminal space in which events and gameplay occur, but is itself a critical manifestation of those interactions—player vs. world.

This kind of ideology represents a vision of modernism in which the artist embraces his or her world as it is, rather than through the confinement of any single medium. Despite its modernist trappings, though, this is not a particularly modern philosophy: when asked about how his statues were so beautiful, and where he drew his inspiration from, the sculptor Michelangelo once purportedly said, “Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it”. And indeed, much in the same way, parkour embrace this notion of a ‘hidden beauty’; an often frenetic, chaotic, wild sense of beauty trapped within the environment, waiting to be freed in powerful, explosive strokes. This aesthetic seeps into the vocabulary of parkour: the traceur (or ‘tracer’), as the runner is called, is cast as both simultaneous artistic genesis, and an active ‘discoverer’ of the environment that she traverses. What Michelangelo attempted to arouse with the powerful sweeping arches and tumbling spires of marble, and what the painter Jackson Pollock attempted to capture in the graceful splatters and arcs of his compositions, the traceur experiences as an intimately physical phenomenon, rawer than any other medium—nature not diluted through a canvas but experienced through direct interaction with the interface of reality.

The traceur, then, is simultaneous artist and audience, as framed within the paradigm of modernism. Artist, in the sense that she is navigating (interpreting) the environment through a specific chosen course of action in a conscious decision, resembling the painter’s choice of colors and forms, or the dancer’s choice of steps and half-turns; and audience, in the sense that she is directly experiencing the project of art prescribed via movement. The most comparable experience within the frame of traditional art would be either theater or dance. Unlike more static disciplines such as painting, sculpture, or architecture, dance and theater add the element of time. The work can be enjoyed while it is created/performed, yet afterwards it disappears and leaves no trace. Memories of traceurs flitting through an urban landscape like silent birds, and memories of ghosts spinning to a haunting melody, are all that remain after the performance is done.

Liquidation of systems through the deliberate subversion of each system’s rules

Parkour also fundamentally embraces the ideology of resistance which runs through the heart of the modernist movement. Modernist art rejects traditional form and convention in favor of bold individual freedom, with emphasis on the deconstruction of systems and societal notions of aesthetic order. It espouses the liquidation of systems through the deliberate subversion of each system’s rules from within: for example, where the abstract expressionists utilize the canvas as a means of destroying the notion of a canvas, the traceur utilizes the environment as a means of demonstrating the inherent flaws presented by the environment. As painters such as René Magritte and Salvador Dali sought to dissemble the banalities of modern life by rendering them in nearly hyperrealistic, yet simultaneously surrealistic detail, parkour strips it away through the aestheticization of everyday objects and routines. It turns mundane objects into objects of navigation, and tired routines into paths of varied creativity and strategic exercise. This is no more obvious than in the glittering, nearly sterile world of Mirror’s Edge, a white utopia splashed with the occasional hue, every color and surface indicating not a quotidian occurrence but an opportunity for catapulting, for vaulting, for veering, for vaunting, for launching oneself away towards another precarious edge.

It is in this act of reappropriation that parkour takes on the full qualifications as a work of modernist art. Though markedly materialist philosophers such as Karl Marx and Walter Benjamin would argue that there is no return to an authentic existence—in other words, a state of being in society in which one’s actions, desires, and general consciousness are independent from the influence of social structures—that is not the purpose of either parkour, or modernism in general. Neither is free from social relations, as both are reactions and thus products of such worlds which bred first their existence, and then perhaps their necessity. Neither seeks to be independent from their respective systems, either. Rather, they work by constructing different dialectics with their respective environments; dialogic engagements in which the balance of power is concentrated on the artist/audience rather than the origin of the dialogue, the system itself. Parkour is based on the activity of self-discovery and personal revelation—each traceur discovers a personal experience of freedom through navigating different, self-defined paths through their environments, a discourse in itself which leaves room for each individual to interpret the environment on their own terms. It is modernism at its finest. It does not promise a return to an ‘authentic’ existence free from social relations, one that so many have attempted to reach but have never come close to replicating. Instead, it provides a way for individuals within the modern world to renegotiate their artistic experience and ways of thinking about these interactions within the confines of the unbreakable society, but simultaneously outside of it. As a work of modernist art, parkour takes on a different rationale by rejecting the efficiency and economic logic engendered in predetermined urban spaces. It appropriates space within the system but also beyond it by differently consuming the material society and in so doing rejecting the arbitrary domination created by its rules and limitations.

As the traceur leaps from building to building, vaults over railings and across stairs, these spectacular corporeal exercises further solidify a new way of approaching mundane space. Parkour, although dependent upon the physical space of one’s environment, molds its own territory constituting different legibilities of physical and kinaesthetic environment. Thus, parkour achieves the modernist goal of simultaneous coexistence with and liberation from an overruling system, and becomes a practice of freedom—a way of liberating the practitioner from the confines, both material and abstract, that are found and engendered in urban architectural space.

The noon sun hangs precariously in the sky above the rooftops. The buzz and hum of the city below, amplified through the canyoned echo of the concrete jungle. A cold wind blows, a pigeon lands on a ledge beside me, 300 feet above the ground. The open blackness of the roof beckons me. Step once. Step twice. Jump. The seconds hang in the air, gravity’s rainbow. Birds in flight. The landing is hard, and strains the soles of my feet with pain, but the impact is absorbed as the body responds to the shock, rolling forward. The sky looms and lurches above me, hard and clear. Feet and hands working in tandem, I rise and continue running. There is nothing but mass, fluidity, and compressibility. There is nothing but freedom.

The post Mirror’s Edge and the politics of parkour appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 2, 2016

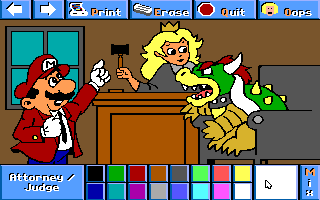

That time Super Mario decided to get a real job

Super Mario, as long as we’ve known him, has been a plumber. Strangely we have rarely seen him engage in any plumbing. Super Mario is simply surrounded by pipes, but we do not see him inquiring about water leaks, fecal blockage, or invoices. Super Mario is more of a career adventurer, a socialite, a close friend to the royals, and the matter of his income would be more confusing if it weren’t for all the coins he picks up. The fact that every 100 coins automatically turns into an extended life suggests Philip K. Dickian elements may be at play within the mushroom kingdom, but dystopian factors don’t bar Super Mario, and his friends, from dreaming.

Super Mario Bros. & Friends: When I Grow Up (1991) was an edutainment coloring book for DOS made by Brian A. Rice, Inc., who also made virtual coloring books for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Inspector Gadget, and All Dogs Go To Heaven, as well as games based on Willow, Young Indiana Jones, and Donald Trump’s casinos. In When I Grow Up, Mario, Luigi, Princess Peach, Bowser, Toad, and even Link all consider different career paths. They imagine lives that could have been. They imagine what they could be doing if they weren’t kidnapping, being kidnapped, or intervening with kidnaps. They imagine of a more pedestrian life. Here are portraits from those lives.

They say divorce court is the hardest. That statement crouched in the back of Bowser’s mind for years, nestled with the wincing thought which repeated “that day will come.” He knew that day would come. He knew it was coming for a long, long time.

Bowser had been cynical much longer than he had been panicked. He came to accept that the case was stacked against him, he just wanted the agony to be over. He requested over and over that his trial be taken to a different county. The bad blood between him and the judge was toxic, thick, and old. The Mushroom Kingdom had very few eligible legal workers. It would be generations until society allowed Yoshi and Boos to approach the bar.

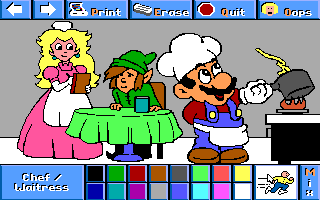

Link had waited for a plate of spaghetti for forty minutes.

Bowser sat in the hot seat, a pedestrian pleather chair that stuck to his own coarse skin. He was surrounded by people who have seen him at his angriest, his most ruthless, his most violent. It wasn’t panic or cynicism anymore, his body was flushed with pure, stone regret. Eventually he was fed up. He thought, if they think they know me, if they think I’m a monster, I’ll be a monster. I’ll put on a show. His tone flared up, gurning his face. He cut into the upholstery with his nails. His eyes turned white and red. He let a wisp of smoke seep through his teeth, residue like a cigarette trail, churned from his hot molten stomach. He looked for a moment at his wife. His ex-wife. Just for a moment. He thought it was like Persephone, just that if he glanced back at her he’d lose everything. She wasn’t crying. She wasn’t distraught. She looked unsurprised.

Bowser requested a recess to use the washroom. He sat in the stall, slumped against the side, weeping his snout into his claws, “They’re going to take my boy away.”

Link had waited for a plate of spaghetti for forty minutes. It wasn’t pomodoro. It wasn’t bucatini. It wasn’t Spanish-style tagliatelle. It was spaghetti and meatballs, the same kind his own father could make in a rushed evening, in family-sized portions. Princess Peach asked for the third time if he wanted anything to drink.

“I’m fine,” said Link. He just wanted to grab a quick meal before going to a friend’s birthday, where there would be drinks, music, maybe even women. He decided to try a new place in the neighborhood, “Mario’s.” It looked humble, hand-made. He liked that. Link liked the idea of supporting local business. His buttock was beginning to feel damp from the sweat. It was a hot room, and the gas stove shot out plumes of fire that reflected off the walls.

“This is looking good!” yelled Mario, presumably, from the kitchen. Link hoped it was good. Link hoped he’d arrive to the party with a story along the lines of, “I tried this new place in the neighborhood, the service was terrible but the food was amazing!”

Link had a second thought. No, the service wasn’t terrible. Peach, she introduced herself, shook his hand, brought him napkins before food, she was very nice, personable. He thought there must be a better way to describe the problem. “Almost done!” yelled Mario, presumably, from the kitchen.

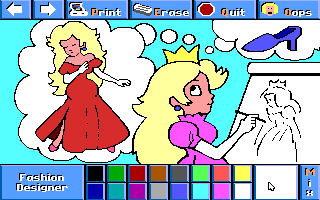

Many people in the Mushroom Kingdom dreamed of being a princess. The princess of the Mushroom Kingdom dreamed about parenthood. And shoes.

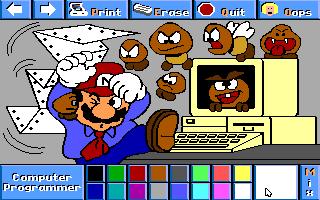

It will always be this way, thought Mario. Mario bought new shirts and pants, nice new shoes. Ties. Mario bought ties. Mario couldn’t remember the last time he bought a tie. He anticipated an office job. The grass is always greener, he told his friends, he would laugh. But it’s always going to be this way.

Mario did two hours of data entry, fielding calls, drinking coffee. Normal. How wonderfully normal! Then it began. They came back. The same stubby little nightmares who followed him everywhere. Turtles he could shake. They’re turtles. No ambiguity. What are these? Mushrooms? Spades? Nipples? Mario would see them everywhere. They were enemies that ruined other things. But he wasn’t mistaking some normal everyday objects for them. They were real. They followed him.

Luigi’s hair was only a third done.

They poured out from behind his desk. One cracked through the glass of the monitor, like a creature birthed from a shiny black egg. They were parading all over the desk of his new life. Mario stood up and rushed out of the office. “I’m fine, I’m sorry” he told co-workers as he passed. He bet they didn’t even see them, out of view behind their cubicle walls or under their desks, like how mice sneak around. They wouldn’t even know they were there.

Mario made his way up to the roof and smoked half a cigarette. It was windy and cold. He outran them for now. It’s not in his nature, but he wondered if he jumped- “Would I end up landing on one of them?”

No one in the Mushroom Kingdom knew there were different sports.

Peach knew Mario. Peach knew Luigi deserved better. Peach knew how to play Mario like a drum. Luigi knew nothing.

Peach sees a lot of things as a post worker. She walks by every house every day. She walks by Mario’s house and she remembers all the things that happened there. Some days she remembers the good moments there, the sweet and sincere moments. Some days she remembers the bad moments. There are no days she regrets her decisions, only that she wishes she could make more.

Mario hears a lot of things. People walk into his barbershop every day, and they talk to him. They tell him about their trips, their kids, their trouble in paradise. Sometimes they are like puzzles, problems from one customer seem to fit with the woes from another. How often, he wondered, had the bane of one man’s life sat in the same chair? He felt like he knew more than anyone.

Peach opened the door but she didn’t walk in. She told Mario she had a package for him. Mario reached over and grabbed the firm envelope. It was reinforced by cardboard sheets to protect what was inside.

Mario unfolded the top of the envelope. It wasn’t fully sealed, it cracked open easier than velcro. He fished out the photos with his thumb, catching just the edge. He stopped. He retreated back to his office. Luigi’s hair was only a third done. He called for Mario. Knocked on his door. Mario never answered. Luigi never saw him leave.

Luigi decided he’d wear a hat for a while.

Luigi listened to “Gangster’s Paradise” five times en route to his first day of work. He never saw “Dangerous Minds,” but he could visualize Michelle Pfeiffer in the video as he made his way to a kingdom he had never stepped foot in before. Luigi thought he’d make the perfect teacher, that he could teach these kids anything.

“Back to our roots!” shouted Mario as he fitted a wrench.

“Back to our roots!” shouted Luigi as he set the tools down by the water heater.

“Back to our roots!” shouted Mario as he twisted a pipe off from the network.

“Back to our roots!” shouted Luigi just before they were interrupted.

From somewhere up the drain was a scream. A genuine, horrible scream. Someone who needed help, immediately, in one of the building’s apartments. They listened for a few moments, stunned, silent. It would be impossible to tell if the rattles and drips that resonated through the pipes were of their nature or signs of life on the other end. These pipes were not big enough to fit through.

The post That time Super Mario decided to get a real job appeared first on Kill Screen.

Conveni Dream tries to make management sympathetic

The dream starts small. It feels big, but in the grander scheme of life and business, it is small. You have a convenience store, and a small one at that—just a few shelves and one part-time helper. But maybe—just maybe—it can be something more. If you work hard, if you make the right choices, and if everything goes your way. If, if, if.

This is both the promise of small-time entrepreneurship and of Conveni Dream, a new game for Nintendo 3DS that turns the challenges of starting a small business into a colorful joyride. Sure, there are stakes—some will build a big business and others will fail—but gone is the pathos. In its place, you will find colors and swiping motions as you choose what to display prominently in the hope of maximizing sales. This is commerce at its most transactional—more transactional than in real life.

There is, of course, the small matter of your employee. Maybe one day you’ll be able to afford a second, but for now it’s just one. Anyhow, that employee—maybe they have a name and personality—is a dot you swipe across the screen. A slightly larger dot than other dots, but a dot nonetheless. This is a relatively old tradition in videogames. In the early 2000s, you could buy a hot dog shop management game from Scholastic (yes, the book people) and Conveni Dream is basically the same thing. You watch these people from above, moving them around. Theirs is not the agency that matters here.

A convenience store is not exactly the ideal place for staging the great labor battle of our time, but Conveni Dream formalizes a cultural idea that’s been in the works for a while. Most nights on Food Network, if you stay up late enough and survive the onslaught of Guy Fieri, you can see one show or another where someone comes in with a series of hidden cameras to tell a boss that their restaurant/shop/bar/hotel’s employees are schmucks. And, to be fair, the employees are often schmucks.

Theft, in case it needed to be said, is bad. But whereas the earlier genre of undercover boss shows humanized everyone, this brand of cultural product offers minimal agency to the employees; it is just corporate surveillance as a form of entertainment. Conveni Dream exists on a smaller scale where everyone is a striver and the discordance is less noticeable, but it’s still hard to escape who gets agency in business simulations and who doesn’t. You are the boss and the employees are dots; you work your way up to a larger business and they… well, that’s a whole other story.

You can purchase Conveni Dream for $5 on the 3DS eShop.

The post Conveni Dream tries to make management sympathetic appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers