Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 112

June 2, 2016

Scale creator explains how he builds such sizey-wizey puzzles

As anyone who’s spent more than a few hours scratching their head at that damn fox-chicken-grain riddle knows, solving a puzzle can often be a frustrating, demoralizing experience. If the puzzle’s good enough, it can even feel impossible. But despite however stressed the solver feels while trying to put the puzzle together, there is always at least one other person it has frustrated more: its creator.

Whereas the solver only has to find a single solution to put an end to their struggle, the creator has to anticipate all possible solutions and narrow them down to just the desired outcomes before even so much as putting their puzzle in front of another person, and that’s only the beginning. In the latest update for the upcoming size-shifting puzzle game Scale, creator Steve Swink gives an in-depth look into just how he deals with this frustration while creating his own brainteasers, as well as the steps he goes through while implementing them into his game’s ever-growing-and shrinking-world.

Categorized under four different subheadings, Swink’s process is long, thorough, and more than anything else, focused on revision, revision, revision. It starts simple enough, with the first few steps being dedicated to brainstorming and drafting, but it’s not long before it becomes an involved process of self-rubrics and continuous notes from testers. However, before Swink can even begin putting a puzzle into the game, he first runs himself through something called the “Idea Gauntlet,” which is a series of self-invented questions about how viable the puzzle actually is and what it might offer to the game as a whole.

“discomfort and struggle are signs that you’re doing the right thing”

“What is the insight?” he asks. “Can this puzzle only exist in Scale? What is the purest form of this idea?” These questions are difficult enough on their own, but they are only the first part of a much longer process. It is only after he has answered them all that he moves onto building a rough version of the puzzle and testing it himself. Beyond this lies more testing, this time with other people at the controls, during which time Swink takes notes on both how players solve the puzzle and if it causes any bugs or defects within the game. Then, two more idea gauntlets, which sometimes involves reworking a puzzle from scratch and having to test the game for bugs again. Once this is all complete, he is finally able to take a breather… before getting ready to start the process all over again.

It’s a laborious process, and as Swink notes, it is often filled with uncertainty and discomfort. But according to him, this frustration is only a sign of progress. “I recently read a great book: Deep Work by Cal Newport,” he writes. “In a later chapter, he describes his experience being a theoretical mathematician and computer scientist. In particular, he describes the sensation of doing deep work.” Swink explains that according to Newport, feeling uncomfortable while doing one’s best work isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It simply means “you’re operating right at the edge of your current abilities and mental capacities.” As Swink explains, ““uncertainty and discomfort and struggle are signs that you’re doing the right thing.”

With this mindset, Swink is able to charge into his process free of his former doubt, confident that like an itching wound, the pain only means progress. “That’s way better than getting all down on myself for not [being] a perfect magical designer whose entire output is immaculate, gorgeous perfection,” he says. “I’ll leave that to Derek Yu.”

To read Swink’s full update for yourself, including a recap of his recent trip to Banff, visit Scale’s Kickstarter page.

The post Scale creator explains how he builds such sizey-wizey puzzles appeared first on Kill Screen.

DOOM’s soundtrack has hellish secrets of its own

DOOM is a game of many secrets. The fast-paced shooter is filled to the brim with nostalgia-laden easter eggs to discover, catering well to its demographic. It’s no surprise that its soundtrack is bursting with secrets as well, this time of the spectrogram variety, according to eagle-eyed fan TomButcher.

It’s no surprise that its soundtrack is bursting with secrets as well

A spectrogram is the visualization of the frequencies of sound. While usually acting as most visualizers do—giving the listener some pretty colors to look at while enjoying a song or album—some musicians, like Aphex Twin, have slipped in eerie imagery into the waves of their music. Composer Disasterpeace took spectrogramming to a new level with his soundtrack for Fez (2012), sneaking in mysterious QR codes, photos, and even a string of dates.

In DOOM’s soundtrack, sly composer Mick Gordon veered pentagrams and the unholy numbers “666” visuals into the aptly titled track “Cyberdemon.” Gordon himself even teased the imagery in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it clip towards the end (at around 3:29) of a Behind the Music video. This musical easter egg of sorts proves that literally everything about the DOOM series remains hellish to this day, from its intense music, its blood-soaked environments, to this subtle subliminal messaging to corrupt the youth: the most dastardly of them all.

You can view the hellish spectrogram findings for yourself here .

Via Engadget

The post DOOM’s soundtrack has hellish secrets of its own appeared first on Kill Screen.

A new videogame art gallery will consume you

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

These Monsters (PC, Mac, Linux)

BY STRANGETHINK

Monsters with a psychedelic Rorschach test for a face. There are loads of them, sitting in framed portraits all around the walls of Strangethink’s latest procedurally generated galleries. Though motionless, these faces seem inescapable. Each black door you see generates another island of maze-like architecture (all ramps and stacks of oblong rooms), offering a chance—you might think—to warp you to a place with different scenery. But the only end here is happening upon a badly generated world that crashes the game, or closing it down yourself. So you move, non-stop, through these endless realms, the audio washing in and out as you pass through doorways, as if you were moving through cities of underwater coral. Evil television sets sit in toppled piles like washed up corpses on a beach at dawn. Underneath them, pools of black ooze squirm—like squids bathing in their own poisonous ink. On the screens is your only distraction; looping teletext about the monsters, which reads “THEY MOVE IN DARKNESS” or “THEY DWELL IN INFINITE BEAUTY.” Equal parts terror and wonder fill your mind. The monsters stare outwards from the walls.

Perfect for: Gallery goers, aliens, hippies

Playtime: 10 minutes, or forever

The post A new videogame art gallery will consume you appeared first on Kill Screen.

The videogame that dares to tackle African politics

Videogames have a problem with how they portray Africa—the continent often appears as nothing more than a stereotypical warzone. The most egregious example is 2009’s Resident Evil 5, which included an unnamed African locale with a conspicuously incensed mob united under an unconvincing explanation of undeadness as an excuse for white protagonist Chris Redfield to shoot every local he sees. A more recent slight was the Call of Duty: Black Ops II (2012) mission” Pyrrhic Victory”, where combatants of the Angolan Civil War are portrayed as machete-wielding maniacs charging at each other in a dusty battlefield. The portrayal was so skewed that in February, the family of Jonas Savimbi, the inspiration for the supporting character featured in the level, sued Activision Blizzard for allegedly portraying the real-life rebel leader in a false light.

Fortunately, there are more recent efforts, such as Aurion: Legacy of the Kori-Odan, a crowdfunded game out of Cameroon, that seek to change the landscape and portray African culture on its own terms. However, two days after its release back in April, Democracy 3: Africa, an expandalone game for the Democracy series, also arrived. Notably, it is not made by an African studio as is the case with Aurion, it is made by a British one, called Positech Games. That makes it worth scrutinizing.

Videogames have a problem with how they portray Africa

Democracy 3: Africa places the player as a democratically-elected leader of various African countries including Egypt, Tunisia, South Africa, Nigeria, Senegal, Kenya, Ghana, and Botswana. The main play screen shows a grid of voting demographics surrounded by a web of circular nodes that represent policies and issues. These nodes relate to each other with flowing arrows that denote pull and push forces. Event triggers influence the effectiveness of these nodes, like a local author winning a book award or a plane crash.

The game diverts from the original Democracy 3 by including factors and challenges that developing countries face, such as desertification, food insecurity, gender discrimination, and female genital mutilation, alongside democratic policy factors common to the Democracy series. In interviews with ZAM, IGN Africa, and Kotaku, creators Cliff Harris and Jeff Davis have shown a keen awareness of the pitfalls of outsiders portraying Africa in a medium that struggles to portray African locales with respect and accuracy. Democracy 3: Africa’s potential role as an education tool (Positech offers educational licenses for Democracy 3) calls for further obligation to portray African countries credibly.

The overarching goal of the Democracy series is to govern by making policy decisions from a presidential office. The player must seek popular approval and votes for reelection by making decisions by turn, which represents a quarter year. Demographics that are deeply angry may form armed groups and try to assassinate the player, ending the game. Since Democracy 3: Africa measures women as dissatisfied due to endemic discrimination and conservative traditions such as female genital mutilation, the player is often opposed to by the militant women’s group Matriarchs of Justice. This is probably an unintended consequence of low starting approval for women and corresponding issues that negatively affect their opinion than an inspired statement about feminism.

With its focus on the executive branch of government, the Democracy series implies that liberal democratic institutions are the primary source of power in society. As someone that lives in the United States, I can barely argue with the practicality and grasp of constitutional power over society—as Philip K. Dick once said, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” However, in less developed, illiberal democratic states, other sources of power are more visible and real. Three factors greatly influence governance in the region: the influence of foreign aid on policy, the arrow of the military in the political sphere, and the ethnic identity of voters. A credible game about African governance should include these factors. And so I played Democracy 3: Africa and made radical decisions in an effort to get these factors to play out. I turned off assassinations so as not to be thwarted by radical groups, including the dreaded Matriarchs, or The Moral Crusade.

A credible game about African governance should include factors other than liberal democratic institutions

Since foreign aid is well documented, Democracy 3: Africa can credibly simulate the influence of foreign aid on African governance. A common form of aid during the late 80s and early 90s was a Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), a loan which required countries to adopt a policy, such as budget cuts, to continue receiving aid. These were offered to developing countries by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Critics of SAPs say that the lenders often advocate for cuts that hinder a country’s development and are often broad brush measures that don’t account for differences in economies. Supporters say SAPs help develop a country’s private sector, balance state budgets, and reduce government corruption. The term has fallen out of favor, but austerity measures enacted across Europe this decade follow the same logic.

Democracy 3: Africa represents this in the node Foreign Aid Received. It is influenced by the nodes Human Development, GDP, and revenue administration. The new policy called foreign aid petitioning also influences aid received. I didn’t see any indications of budget stipulations as a condition of continuing foreign aid. The game represents this as a “softer” push and pull force instead of overt mandates and conditions that the SAPs represented. The game seems to portray foreign lenders as another stakeholder in governance instead of top-down creditors.

The military is a pernicious influence on democratic politics in places like Egypt, Nigeria, and Ghana. 67 attempted or successful coups occurred among 54 countries in Africa between 1990 and 2012. Egypt is a recent example of military intervention on democratic governance. Since the overthrow of King Farouk in 1952, Egypt has been overseen by a faction of senior military officers—the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. Six of the nine presidents of Egypt came from the Egyptian military’s officer corps.

Egyptian Free Officers, the precursor to the SCAF, in 1953 via Wikimedia Commons

The 2011 Egyptian revolution sought the overthrow of military-appointed president Hosni Mubarak who had ruled since 1981. When Mubarak resigned, the SCAF took over and oversaw the 2012 presidential election. Voters chose Mohammad Morsi of the Freedom and Justice Party, affiliated with the historic Islamist party Muslim Brotherhood. Instability and violence during Morsi’s presidency compelled the SCAF to depose and arrest Morsi in 2013. With the sanction of the SCAF, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi took the presidency in 2013. Al-Sisi went on to win the 2014 Egyptian presidential election.

Military intervention appears as a factor in Democracy 3: Africa’s web, influenced by stability and military spending, and pushes against democracy factor as well. When playing Egypt, I tried to decrease stability and raise military spending to elicit a military response to my presidency. With assassination turned off in the options screen, I was insulated from the blowback of decreased public approval. After a few tries, I looked at the code and found that Military State was an achievement, but didn’t elicit a coup. The game seems to think a president is more likely to be assassinated by a militant feminist group than deposed by a military junta. The former is extremely unlikely, while the latter happens frequently.

military intervention pushes against the democracy factor

Kenya is an exception to the perception of violence and military influence on politics in the continent. However, the country has another prominent issue affecting democratic governance. The borders of various African countries had been drawn haphazardly by European powers. During colonialism, some groups were given favorable treatment by the colonizers, while others were treated harshly. This lead to divided ethnic homelands, and different groups competing for wealth and political power in the independent countries that emerged after the colonizers left. In parliamentary governments, political parties may often demarcate along religious sects, ethnic groups, tribes, and prominent land-owning families. Examples include the Hutu/Tutsi conflict that ignited into the Rwandan Genocide in 1994. The Darfur crisis and Second Sudanese Civil war culminating in the independence of South Sudan, and tensions in Nigeria between groups in the North and South—a wedge that terrorist group Boko Haram exploited in its early period.

The disputed Kenyan election in 2007 highlights ethnic conflict influencing elections. The disagreement between the incumbent president Mwai Kibaki and opposition leader Raila Odinga’s resulted in violence between Odinga’s group, the Luo (a group President Obama’s father also belonged to) and Kibaki’s group, the Kikuyu. 1300 people died in the violence and hundreds of thousands left their homes in fear. Despite being only 22 percent of Kenya’s population, the Kikuyu have dominated Kenyan politics and the economy since independence.

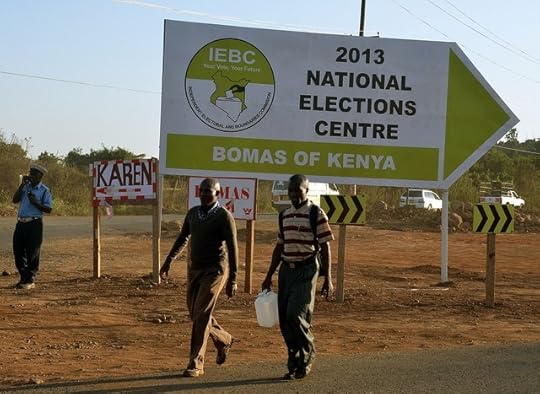

After a power sharing agreement was signed in 2008, feuding between the different factions slowed down. Kenya’s parliament passed the National Cohesion and Integration Act, which established a commission to address ethnic tension. The 2013 Kenyan general election was more peaceful and the NCI commission acted against perceived incitement based on ethnicity. The commission warns that more violence is possible in Kenya’s 2017 general election. Alongside native groups, Kenya had accepted 600,000 refugees from Somalia, Uganda, and before the Kenyan government announced a plan to shut down its refugee campsSouth Sudan before the Kenyan government announced a plan to shut down its refugee camps in May.

Kenyan general elections in 2013 via Commonwealth Secretariat on Flickr through CC

To push different groups into conflict in Democracy 3: Africa, I tried to foster unemployment and poverty. This influences racial tension, as one group blames another for their misfortunes, and groups compete for scarce opportunities and resources. The game triggers race riots if there is enough racial tension. It also simulates the opposition party contesting elections, as Odinga’s Orange Democratic Movement did in 2007, but without the ethnic element that motivated the violence in 2007. We also see the limits of Democracy 3: Africa’s web model. The demographic of “ethnic minorities” seems to only apply to immigrants and their children, as opposed to ethnic minorities who may be native rivals to a region, or an alienated majority, such as Hutu in Rwanda.

While the game’s nodal network expresses the complex stakes that a democratic ruler faces, those stakeholders and issues are not as comprehensive or influential in developing countries such as those Democracy 3: Africa portrays. The underlying assumption of the game is that the player must govern pragmatically towards the popular center instead of towards ideals, or the mandate of a tribe, army, or multinational corporation. The factors reviewed expressed themselves as “soft” cause and effect forces instead of overt power shows that may occur in African politics. The reliability of the game’s simulation is limited by its focus on democratic institutions. And if I’m honest, my focus on coups and ethnic riots is just as clouded by a Western vantage point as the people over at Positech. Despite the limitation, even this narrow view of Africa as a series of challenges to tackle and demographics to pander to is more promising than a perpetually dangerous continent with an interchangeable mob of targets for the cookie-cutter protagonist.

Header via Zeinab Mohamed on Flickr

The post The videogame that dares to tackle African politics appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 1, 2016

Watch the coordinated beauty of birds flocking in digital form

Bird flocks are ruthlessly efficient convoys, though that is not always obvious from the ground. As thousands of birds fly overhead, it is not immediately apparent that they are maneuvering at remarkable speeds or turning on a dime. Enough of this amateur description, however. Let’s turn this thing over to the expert—in this case, Richard Wilbur:

As if a cast of grain leapt back to the hand,

A landscapeful of small black birds, intent

On the far south, convene at some command

At once in the middle of the air, at once are gone

With headlong and unanimous consent

From the pale trees and fields they settled on.

What is an individual thing? They roll

Like a drunken fingerprint across the sky!

“Sometimes I just want to watch birds all day”

Murray Campbell’s Flock is more deliberate than a drunken fingerprint, but its beauty is comparable to Wilbur’s poem. Not so much a game as a series of animated graphics, Flocks shows abstracted winged creatures flying across the sky. Are they airplanes, birds, fireworks? It isn’t really clear; you are too far away to tell. The same holds true with actual bird flocks. There’s only so much you can understand from the ground, but they are compelling nonetheless. “Sometimes I just want to watch birds all day,” Campbell writes, “don’t you?”

Flocking is not an intuitive concept to grasp. “Imagine doing unrehearsed evasive maneuvers in concert with all the other fast-moving drivers around you on an expressway,” writes Peter Friederici for the Audubon society’s magazine, “and you get an idea of the difficulty involved.” That, incidentally, would be a good pitch for a game (and synchronized driving, as with swimming and virtually all other synchronized activities, makes for good viewing). Since birds are hard to appreciate from the ground, they are excellent candidates for abstraction, and Campbell pulls off the art with great effect. Flock is basically a screensaver, but it promises nothing more and, like Campbell, I just want to watch birds all day.

You can check out Flock over on itch.io.

The post Watch the coordinated beauty of birds flocking in digital form appeared first on Kill Screen.

Visual novel sends you on an accidental trip to the darker side of Japan

When I had the chance to visit Japan, after years of accruing savings and getting a handy-dandy passport, it was a dream come true. I could collect adorable capsule toys wherever I travelled, eat conbini onigiri at my leisure, and admire the beautiful streets and swift transit system. Japan was the most amazing place I’ve ever visited.

But even perceived utopias aren’t perfect, and musician and game maker Sean Han-Tani-Chen-Hogan (HTCH) knows that. So in comes the bleak visual novel HIROSHIMA 2016: Sean Hogan Visits Japan, an adventure filled with insensitive Twitter feeds, President Barack Obama visiting Hiroshima, and witnessing dastardly real-life crimes.

All of these steps take HTCH down a path to witnessing the dark side of Japan

HIROSHIMA 2016 is lo-fi as hell. Low-res JPEGs plague every “background,” and even the text of HTCH’s Twitter feed is of the lowest quality. Between tweets of excitement from HTCH of visiting Japan are cheery Kotaku headlines, like one about a new Catbus for adults at the Ghibli Museum, and humorous tweets from HTCH’s own peers. All of these are real tweets, of course. And as the game progresses, the tweet-checking grows more and more egregious.

HTCH is on a quest to buy an idol CD (coupled with a way-pitched down version of kawaii-guru Kyary Pamyu Pamyu’s “Pon Pon Pon”), take a selfie in Okinawa, and visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. Except, all of these steps take HTCH down a path to witnessing the dark side of Japan. Along his journey back to Narita Airport, HTCH sees President Obama’s press conference at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, the aftermath of a horrific crime in Okinawa (the latest in a long line of U.S. Marine-involved assaults), and even the recent stabbing of a pop idol take place.

When not creating the bleakest of visual novels, HTCH spends his time composing music and making games. His current most prominent projects are Perfect, a “software with elements of 2D exploration games, web browsers, music albums, and nonfiction interviews,” specifically about the issues rising from the future state of nationality, race, and identity, and Even the Ocean, a diversity-driven adventure platformer.

You can download HIROSHIMA 2016: Sean Hogan Visits Japan for PC or Mac here . You can also follow the ongoing-development of HTCH’s next big project, Even the Ocean, here .

The post Visual novel sends you on an accidental trip to the darker side of Japan appeared first on Kill Screen.

Online art installation examines propaganda in the Internet age

The first few moments in the online version of The Sprawl can best be described as overwhelming. Videos with bizarre eye-catching graphics shift around for just a second, there’s a moving shape in the background. The text that appears would seem to be an explanation, but explains very little, saying, in part, “pixelated illusions replace our faith in information, ideologies collide in chasms of uncertainty and hope.” This is Dutch design collective Metahaven’s latest project, The Sprawl (Propaganda about Propaganda), a film/installation examining propaganda, its usage, its prevalence, and how it affects our view of information and truth.

simulates the quagmire that is propaganda in the Internet age

Although The Sprawl is being shown as a film, there’s something unique about its presentation on the website. Clicking through the videos (their arrangement partially shaped by YouTube’s viewing algorithms) rather than having them all presented in a particular order for you to watch, it captures that investigative feeling. Metahaven refers to these short videos as “shards.” Although everything there is created and curated by Metahaven, giving it in small, bite-sized shards and having it be presented in such a non-linear fashion allows the viewer to feel like they are uncovering something.

Although the project is focused mostly on the Ukraine and Russia, in an interview with The Fader, Metahaven expressed that they do not believe this kind of propaganda is in any way exclusive to them, and they could easily make further projects in other places. After going through all of The Sprawl, one is likely to have many more questions, and no more answers. The truth feels so close you can touch it, but it still just eludes you. You’re pulled again to watch a video one more time, hoping to understand it better. But even if you do, The Sprawl effectively simulates the quagmire that is propaganda in the Internet age, and you’ll still be looking for more.

Experience The Sprawl for yourself here.

The post Online art installation examines propaganda in the Internet age appeared first on Kill Screen.

Screw diamonds, the dildo hoverboard is a girl’s best friend

Don’t you just hate it when you need to give the ol’ honey pot a little self-loving but you’ve got an early morning meeting at work that you’re already late for? Me too. That’s why I’m totally psyched for the creator of the Dildo Drone, Michael Krivicka, and his newest invention: the Dildo Hoverboard.

Okay, so maybe it’s a faux invention, but think of the possibilities if it were real. The faux-prototype Dildo Hoverboard presents a speedy way to get to work, perfect for the busy millennial, while also giving its rider the option to multitask with a little, you know, somethin’-somethin’.

forces a taboo act into the public sphere for all to see

The device is, the product’s YouTube advertisement claims, “fully adjustable” with an “easy to use control panel” where you can pick your personal favorite thrusting speed and rhythmic vibration. Not stated in the ad is the potential for a pretty awesome ab workout. I mean, imagine the balance required to maintain the straight posture while also hitting all the right places.

But perhaps the best part of the Dildo Hoverboard is how it forces a taboo, secretive act into the public sphere for all to see and revel in. It could inspire a whole new era of openness and sex-positivity! And what better timing, for May was National Masturbation Month. What’s it hurt to extend it for one extra day? I’ll bring the maypoles.

But wait, you may say, this is actually really creepy and I don’t think I’d feel comfortable standing next to someone in line at the Starbucks enjoying their new Dildo Hoverboard. To that I say, is it really as creepy as the very not-faux lap pillow, though?

Hold on, you may say again, isn’t public masturbation illegal in most states? And to that I say, no comment.

Check out the Dildo Hoverboard and Krivicka’s other faux inventions here.

The post Screw diamonds, the dildo hoverboard is a girl’s best friend appeared first on Kill Screen.

The difficult history of videogames and indigenous people

Content warning: This article mentions child abuse and rape

///

The Raven and the Light (2015) starts with a car crash. It ends with an almost dream-like ascent to a state of transcendence, narrated by the myth of the raven and the light—a Northwest indigenous folk tale. Everything in between thrusts you into a world that, for some, will be foreign, but for North America’s indigenous population is and has been painfully real.

Your character in this horror game (mostly unseen and unheard throughout) explores a fictional residential school called Mother Mary’s Residential School for Indian Students. Inside, you dodge monsters and creatures while picking up documents (letters, diary entries, and records—also fictional) that tell the story of a former residential school student—referred to as Sixty-Four—who was raped by Reverend Caldwell (the clerical patriarch of the school), who is later revealed to to be your mother.

Its invented details might not be real but the horror of the experience is

Not many videogames would dare venture into a subject as touchy as Canada’s dark history of residential schooling and the damage that it inflicted upon hundreds of thousands of indigenous students. They were forcibly taken from their families, enrolled in remote schools, and banned from expressing their language or culture in any way. More often than not these students were physically and sexually abused too. The Canadian residential schooling system was historically designed to extinguish indigenous culture and assimilate an entire race into a distinct vision of English-Canadian whiteness. It existed in Canada for much of the 19th and nearly the entirety of the 20th century. With the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015, the history of residential schooling is only now beginning to be understood in terms of its human cost.

The purpose of The Raven and the Light is to introduce this history. And it does this with a story that is both fiction and not. Its invented details (characters and places) might not be real, but the horror of the experience is. To wit, it uses fictional horror to teach its players about the experience of a real-life terror.

///

It’s a defining experience of 21st century living to go down a digital rabbit hole and emerge differently on the other side. Case in point: about three years ago, Mark Basedow, a young, wiry first-time game maker from Ringwood, NJ, was in search of a setting for a horror game. “I wanted to do something with some meaning to it,” he says. After all, an explosion of independent game makers over the past decade has created more noise to cut through. “I was thinking of a cold area, and I typed into Google: ‘Canada’s dark past.’,” he said. What Basedow stumbled upon was Canada’s history of residential schools—something that the entire nation is still, in a way, stumbling through.

A lack of awareness about the history of residential schooling has allowed Basedow to break new ground with The Raven and the Light—quite possibly the only videogame to approach the subject of residential schooling, and one of only a few games that casts an indigenous person as its protagonist. It’s a simple fact that, for indigenous people, videogames have not been especially welcoming. The various histories of indigenous people—histories that contain some of the worst atrocities committed to a group of people ever—almost never make it on screen, and when they do it’s not in any meaningful way (think Custer’s Revenge (1982), which only worsens with each year in how offensive it is to Native Americans).

In western games like Red Dead Revolver (2004), and Gun (2005), killing “Indians” is rewarded, and indigenous characters are portrayed as a savage, primitive enemy. In countless other games, indigenous characters are only ever portrayed as warriors or North American quasi-necromancers. (It goes without saying, of course, that this is both a damaging and wildly inaccurate way of coming to know the histories and lives of indigenous peoples.) The Raven and the Light, in its small way, attempts to bring more attention to the true, and often unpleasant, aspects of indigenous history.

///

While The Raven and the Light has some elements that are expected in a horror game—at one point you have to escape a rapidly freezing room, while another has you dodge hungry wolves—these seem like secondary challenges. The Raven and the Light throws you into a virtual environment not necessarily expecting or demanding that you be challenged in any technical sense, but a social sense instead.

“I typed into Google: ‘Canada’s dark past.’”

History, while important, can be a hard sell; the nuances that tend to excite historians are not often dynamic or sexy enough for the general population. Museums can be distant and struggle to tell stories, books and articles might be considered lifeless, and architecture might not be interactive enough for some. Videogames offer new possibilities for the communication of history—especially difficult history—to those who might not otherwise learn about occurrences like residential schooling. It’s worked before, particularly with war—games often succeed in placing you in the shoes of a soldier, pilot, and so on. For archetypal figures, like soldiers, who are generally valorized, and who are not generally subject to the kinds of systemic prejudice that one sees when discussing indigenous peoples, very little is at stake: all glamor, but not often much substance. Soldiers are celebrated as honorable, the history is told through action set-pieces, but not much is typically said about people or culture.

With difficult histories, like the residential schools in The Raven and the Light, however, videogames offer “a very effective way of getting things about the culture to younger generations,” says Tehoniehtathe Delisle, a young indigenous individual from Quebec, who was enrolled in the Skins Workshop at Concordia University (a program designed to integrate indigenous individuals and culture into videogames by training young, indigenous game developers). “They really listen to it. If they’re playing videogames it’s like they’re actually active in the story—it’s like they’re the character, and they’re actually playing through this, and listening, and actually hearing these stories.”

In the past few years, indigenous communities have begun to explore the possibilities that videogames, as a medium, act as a channel through which to tell stories and relate their culture to the broader world. Earlier this year, a University of Sao Paolo anthropologist created Huni Kuin, a game that explored the history of the Huni Kuin, an Amazonian tribe who live in western Brazil and Peru. Other games have been used in more direct efforts of cultural preservation. In 2013, RezWorld was released (now branded as Talking Games). It’s an interactive game used to teach indigenous languages. In its first iteration it was designed to teach Cherokee, but has since been adapted to teach a vast array of indigenous languages.

According to Statistics Canada, indigenous populations are the fastest growing demographic in the country—meaning that there are a tremendous number of young indigenous individuals who are embracing digital media in a way that no generation before them was able to. “We’re in the digital age, and we need to create our own things,” says Owisokon Lahache, a staff member at the Skins workshop. “Videogames are becoming as important as any other mass media,” says Jason Edward Lewis, another staff member. “The more opportunities we make for ourselves as a people to tell our stories and to represent ourselves, the more powerful we’ll be as a people,” he adds.

for indigenous people, videogames have not been especially welcoming

Telling indigenous stories through digital media presents a new challenge for communities who have, in the past, had a greater degree of control over the way stories are told. “There are definitely people out there—native people—who don’t think that non-native people should be hearing native stories,” says Fragnito. “We treat very carefully—there are definitely stories that are not supposed to be told.” Young indigenous game makers, however, are more interested in telling their stories to a wide audience, rather than a selective one. “We say: this is going to be your story, and you can tell it as widely or as tightly as you want,” says Fragnito. “They want it to be as big as Assassin’s Creed III (2012)! The idea is that more videogames made by native people, with more native characters, to get a richer picture of who we are.”

///

Broadly speaking, things are getting better. Delisle also brings up Assassin’s Creed III, this time as an example of how indigenous cultures can be represented well. “They did a lot of research, and they had a lot of our language in the game,” says Delisle. “I think that got to a lot of the youth all over the place.” (The main character, Ratonhnhaké:ton—a half-English, half-Mohawk assassin—gets caught up in the American Revolution after his village is invaded. In addition to the positive and researched portrayal of Ratonhnhaké:ton, the game explored a less well-known perspective on a well-worn conflict through the use of indigenous characters and settings.) Programs like Skins aim to provide a platform for indigenous game makers to inject their characters, their voices, their experiences—in short, themselves—into videogames. The program, started in 2011, is growing, and is beginning to reach out to indigenous groups across Canada in hopes of improving representation and, perhaps more importantly, to help young indigenous individuals gain the skills needed to make inroads into the actual development of games.

It seems that indigenous game makers are realizing that videogames are a legitimate medium through which to communicate their cultures—and there are more resources and tools available that encourage and allow them to enter the game development industry. “Getting our culture out there is one of our biggest concerns right now,” says Delisle. “Legends are different throughout different nations. They change over time, and people tell them in different ways.” But all this may not be enough.

The Raven and the Light, like many smaller games, had a limited reach. It was downloaded about 2000 times, and enjoyed a handful of mixed reviews on YouTube. But then its existence seemed to be forgotten, it becoming yet another artefact of the internet. Its reach, though, does not diminish the effect of Basedow’s bigger point. Residential schools were, by just about every metric imaginable, quite horrible. But to many who didn’t live it, or whose families haven’t lived it, or who haven’t had the opportunity to learn about their history, residential schools can seem distant. By putting you within the walls, to confront a fictional story intertwined with historical fact, and by imploring you to learn more for yourself, it’s possible for the game to bring a dark history a little bit closer to the light.

The post The difficult history of videogames and indigenous people appeared first on Kill Screen.

Far from Noise, an upcoming narrative game about nature and mortality

Transcendentalism and 19th-century American thought aren’t the typical influences in game design, but London-based programmer George Batchelor is prepared to overlook that.

Though he works primarily for the BAFTA Award–winning studio State of Play, Batchelor moonlights as a game maker on his own personal projects, such as the forthcoming Far from Noise. A low-poly, warm-hued game in which the player takes on the role of a woman in her early 20s having a lengthy conversation with a deer, it promises both a rich narrative and more than a few surprises. After driving through the woods, the young woman loses control of her car and finds herself teetering on the edge of a cliff, surrounded by nature and confronted with mortality.

“The game is essentially a story that takes place over a day and a night,” Batchelor told me. Little by little, strange mysteries begin to unfold; you’re made to face your own identity, your motivations, your fate—things set in motion before the game ever began. But “it’s actually pretty lighthearted, too,” he said. “It’s not all deep introspection. You crack a lot of jokes.” Batchelor credits the writers of the Transcendentalist movement—namely Emerson, Thoreau, and John Muir—as his inspiration. “I love how poetic and intense they get about the outdoors. It’s great.”

“You get these really great dynamics a lot in theater”

Another philosophical component of the game is that it’s built entirely around a dialogue. “There’s something about two characters just having a conversation that can be really powerful,” said Batchelor. “You get these really great dynamics a lot in theater, things like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead—the back-and-forth between the characters is the best. Also, Daniel Clowes. Any dialogue he writes is brilliant. It’s fun getting into that sort of thing with games; people playing the game can then start to guide the conversation and set the pace.”

While most games use dialogue as a method of interrogation, either to find a clue toward solving a puzzle or help you get to the next environment, Far from Noise lets players simply experience a conversation for conversation’s sake. This involves making choices that steer the direction of the game’s story and trigger different events on each playthrough, which Batchelor hopes will add replay value to the narrative.

Batchelor has enlisted the help of musician Geoff Lentin to score the game, and hopes to launch the title on Steam Greenlight and itch.io later this year, once he’s released a trailer.

Visit the developer’s blog to find out more about Batchelor’s various videogame projects.

The post Far from Noise, an upcoming narrative game about nature and mortality appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers