Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 107

June 14, 2016

Star Trek: Bridge Crew brings space camp to virtual reality

I was always under the distinct impression that Star Trek was a virtual reality—no, it’s really not necessary to email me about this—but now… it actually is?

This is Star Trek: Bridge Crew, as revealed at E3 on Monday. It’s a collaborative VR game where, instead of interacting with your friends, you all put on headsets and interact with one another’s avatars. Here, for instance, are some of the franchise’s distinguished alumna giving it a go:

Having actors record a video trying out virtual reality is always an interesting gambit because they are… well… actors. But, for argument’s sake, let’s assume sincerity and check out their VR faces.

Here is Jeri Ryan, of The OC and apparently also some Star Trek franchise fame, looking excited while wearing the world’s most expensive blindfold:

And here is Karl Urban, who sources tell me is not related to Keith, just chilling:

Rounding it all up is LeVar Burton looking into the middle-distance, or maybe not because he has a headset on:

For all its virtual reality trappings, mind you, Star Trek: Bridge Crew appears to be a relatively traditional game. Collaborative setups where players interact on some levels but interface with computers on another one is not a new idea. Battleship is a confrontational version of this setup. More recently, We’ll Meet Again challenged two players to solve problems while both staring at screens and talking to one another. (Not to mention that we’ve already had Artemis Spaceship Bridge Simulator, which is basically this Star Trek VR game in all but name) The screens in Star Trek: Bridge Crew just so happen to be mounted to the players’ faces. Otherwise, the setup is more conventional than it appears.

There is, of course, another term for this game: space camp. It is, after all, a place where people go and LARP as space explorers while staring at screens. It’s science fiction and so is Star Trek: Bridge Crew.

The post Star Trek: Bridge Crew brings space camp to virtual reality appeared first on Kill Screen.

ReCore, robots, and us

ReCore belongs to a grand storytelling tradition. From Forbidden Planet (1956) to Big Hero 6 (2014), Isaac Asimov to Fallout 4 (2015), science fiction has long been preoccupied with the bond between humanity and machines. So have I, for that matter—my earliest memory is being hospitalized for pneumonia at age two and getting to interact with a remote-control robot in the hospital’s playroom. There’s something incredibly powerful about the notion that we’ll one day create automated beings with superior intelligences and mechanical bodies that’ll outlive us all.

First announced at last year’s Microsoft E3 Briefing, ReCore is the story of a young woman named Joule Adams and her robotic canine, wandering a storm-ravaged desert called Far Eden and fending off hostile machines in the wake of some mysterious world-ending event. It might be worrisome that the worldbuilding appears to be equal parts Destiny (2014) and WALL-E (2008), if not for the sheer undeniable talent behind the project.

her companion thrums to life in its new form

The game is being directed by Mark Pacini (Metroid Prime), produced by Keiji Inafune (Mega Man), and written by Joseph Staten (Halo). From what we’ve seen so far, the combat system and story of ReCore share little with these superstar designers’ previous games, though it does seem to fall into the narrative trap of having to shoot everything in sight in order to progress through the world. This may not be such a bad thing, so long as there’s a degree of something (anything) mechanically different to every other shooter out there happening as part of the deal, though the most interesting thing about the game so far has to do with repairs.

When Joule’s “Corebot companion” Mack sacrifices itself to save her from a band of spiderlike foes in the game’s 2015 announcement trailer, it leaves behind a glowing spherical core. Joule retrieves the core and places it inside the body of a dormant, much larger robot, and her companion thrums to life in its new form. Yesterday’s E3 2016 trailer shows the player wielding a grappling hook to swipe the cores of enemy machines to revive and, presumably, upgrade your Corebot companions.

I’m reminded of the Pokémon-esque Super NES game called Robotrek (1994), in which the player character builds and maintains a team of robots to defend himself on his quest to save the planet of Quintenix from a sinister faction called the Hackers. Except that this time around, Joule is among the last humans in a world dominated by technology—a clear example of the emerging scavenger archetype. See also: Rey in The Force Awakens (2015), D.va’s “Scavenger” and “Junker” skins in Overwatch, WALL-E, and Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984).

“As one of the last remaining humans on a planet controlled by robotic foes bent on your destruction,” the Xbox.com product description explains, “you must forge friendships with a courageous group of robot companions, each with unique abilities and powers. Lead this band of unlikely heroes on an epic adventure through a mysterious, dynamic world.”

ReCore is slated for a September 13 release on Windows 10 and Xbox One.

The post ReCore, robots, and us appeared first on Kill Screen.

June 13, 2016

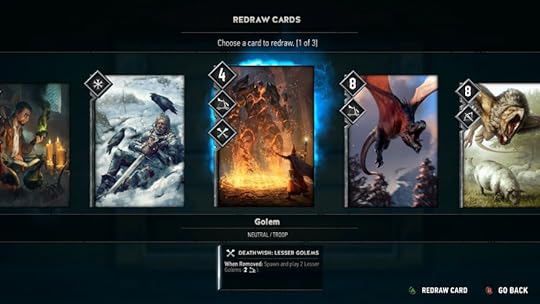

All your real-life Gwent fantasies are coming true

Among the countless hours I spent playing CD Projekt RED’s sprawling open-world adventure The Witcher 3 (2015), too many of those were spent playing Gwent. Whether it was battling against random merchants or innkeepers, or challenging the best players of Novigrad in an effort to win a coveted card of my surrogate daughter, the seemingly simple card game of Gwent wasn’t just another side quest. Gwent transcended the tedious minigame trope and became something wholly enjoyable itself.

I can see myself roaming the pubs of San Francisco to battle friends, as I once did in The Witcher 3’s Velen

During Microsoft’s E3 conference, the Poland-based developer took the stage to announce a standalone, spin-off game based on the beloved minigame, aptly titled Gwent: The Witcher Card Game. “Gwent literally would not exist if the fans hadn’t sent us thousands of emails,” said Damien Monnier, lead designer for CD Projekt RED during a quick interview on YouTube Gaming’s Live at E3 stream. Monnier insists that the new multiplayer-employed Gwent will still have the core mechanics of its The Witcher 3-bound predecessor.

A standalone Gwent likely would not have been able to live were it not for the immense success of Blizzard’s World of Warcraft (2004) virtual card game spin-off Hearthstone (2014). But where Hearthstone was developed from nearly the ground up (aside from lifting some art from the physical World of Warcraft Trading Card Game (2006)), Gwent has the foundation of already being a game, and the ability to be expanded beyond that. Part of the appeal of virtual card games like Hearthstone and Gwent is the portability of it. There’s no more lugging around binders of cards, as many once did with Pokémon or Yu-Gi-Oh cards. With Hearthstone and Gwent, everything is available at all times.

I can see my future now. Roaming the pubs of San Francisco (once Gwent is hopefully readily available on my tablet), as I once did in The Witcher 3’s Velen, seeking out other experienced Gwent-players to play against. With some well-timed cards, I’ll defeat others triumphantly for that one powerful card. Then I’ll pack it in, return home, until the next glorious Gwent challenge awaits.

You can sign up for Gwent: The Witcher Card Game’s beta on PC and Xbox One here .

The post All your real-life Gwent fantasies are coming true appeared first on Kill Screen.

The next game from the creators of LIMBO goes full-on George Orwell

It’s been six years since black-and-white sidescroller LIMBO (2010) came out. It might not feel that long—it doesn’t to me—due to it having lingered with an almost ghostly presence over the world of videogames. Small or large, it didn’t matter, many games have since adapted LIMBO‘s foggy chiaroscuro and quiet, morbid world for their own stories. You might think then, given that length of time, as well as the lasting paucity of LIMBO, that the studio behind it, Playdead, would have moved on. Plus, surely, the two-tone 2D landscape was made out of necessity; don’t they have wilder dreams to realize off the back of its runaway success?

Well, take a look at the new trailer for INSIDE, and you’ll see that while, yes, Playdead’s second game is bigger, more animated, and has crowds of people rather than a single running-and-jumping boy, the tone is wholly familiar. Playdead, as is perhaps given away in its own name, is a studio interested in foreboding scenes of overhanging darkness and young boys in a lot of danger. With LIMBO, the studio struck down hard with a determined style, and hit it off big. And now, with INSIDE, it looks like the studio is going to take the same idea and weave it with an eerie sci-fi tone fitting of both the Cold War and the 1953 movie adaptation of The War of the Worlds. Large stabby spider legs and spear-throwing tribes are replaced by men with flashlights, pick-up trucks, and guns.

The world of INSIDE seems to be one made to make you ask the question: what kind of people would be so willing to shoot a small boy dead? You can see this happen in Polygon‘s 10 minute footage of the game in action. The boy hops over a wall—after pushing over a block to reach its top—sneaks past some guardsmen in the background, before being chased by his pursuers into a trap. POP. POP. His chest bursts open with the impact of the bullets and he dies. Grim.

assembly lines of humans are overseen by steel robots

The impassiveness with which this violence is presented totally resembles LIMBO‘s silent approach to death and the killing of children. It’s Playdead’s way of communicating two things: 1) You fucked up, try again; and 2) This is a nasty place, take nothing for granted. This is why there’s a totally serious moment when an angry pig wakes up and chases the boy, charging him as if it had horns to do any damage with—everything in INSIDE wants its main character to die as immediately as it spots him. Suffering isn’t an option; it’s gotta be instant, bloody death.

A little later in the footage we find out why this might be the case as a machine-guarded facility is traversed and the sunken city beyond it is explored by way of single-person submarine: welcome to dystopia. The most telling detail here is the technology on show. It is not modern, in fact, it’s perhaps closest to the future envisioned by George Orwell in 1984 (1949), one in which assembly lines of humans are overseen by steel robots, and not the other way around. The fact that there are armed men driving around in military-like vehicles shooting runaways, while we’re also shown large halls of people sat around occupying their time, suggests that a robot manufacturer (read: corporation) or a government has got away with ruling this darkened land with violence and surveillance.

What is the big fear that they have used to pin down this population, though? That’s the big unanswered question. You’d typically expect to see propaganda plastering walls to tell this part of the world’s background, but it’s either in short supply or completely absent. However, perhaps it isn’t needed at all. In one scene, the boy happens across a device that looks like an upturned sieve, which sucks onto his skull and allows him to control the adults in the background as if they were puppets. He flings his limbs around and they copy the motion. It’s the kind of invention that drives scientists mad and turns bullies into dictators. You can see where this is going…

INSIDE will be coming out for Xbox One on June 29th and Steam (for PC) on July 7th. You’ll be able to pre-order the game on its website.

The post The next game from the creators of LIMBO goes full-on George Orwell appeared first on Kill Screen.

Listen, Battlefield 1 owes nothing to history

The title might say it all: Battlefield 1’s choice of numeral suggests a process of looking backward, of turning to the past to find a way forward. In its appearance at the EA Play event yesterday, Battlefield 1 demonstrated this in what was a comprehensive display of force: British Mark IV tanks churned through French mud like supercharged rally cars, soldiers bayoneted their foes after Olympian sprints across the battlefield, and zeppelin after zeppelin tumbled to the ground in a simulacra of the Hindenburg’s fiery descent.

Yet the commentary was not the panicked voice of Herbert Morrison, his cry of “Oh the humanity!” echoing through the years, but the rapid-fire patter of commentators Golden Boy and Westie. But this is as it should be, there is no humanity lost here, no death. These soldiers return to their feet as soon as they have fallen, run through bullets, throw themselves to prone position with the abandon of a Hollywood stunt man. As we watch a magic syringe revive a fallen teammate, a parachute effectively deployed seconds before impact and grenades ping about like tennis balls, it becomes increasingly clear that this is a Battlefield game before anything else. World War I is little more than a patina, a thin layer of mud and mustard gas draped over the same whirring machinery.

World War I reimagined as a frictionless machine

So why the consternation, the hand-wringing? Since the recent announcement of Battlefield 1 there has been a rumbling murmur of worry, suggesting that the setting is distasteful, disrespectful, or historically inaccurate. Even the boss of EA game studios, Patrick Soderlund has said that “When the team presented the idea to me of World War 1, I absolutely rejected it.” Though Sonderland was eventually convinced by the team at DICE, his mention of this seems intended to give him some critical distance, so he might remain safe if critical opinion turns sour. Of course, there is a hypocrisy on display here, not just from Soderlund, but in the general accusations of disrespect or disgust. After all, DICE has been depicting war as “fun” for over a decade now, running through both historical settings in Battlefield: 1942 (2002) and Battlefield: Vietnam (2004), as well as the contemporary fictional wars of Battlefield 2 (2005), Battlefield 3 (2011), and Battlefield 4 (2014).

The lack of similar distaste being expressed around Battlefield 4 in particular is telling of both our comfort with depictions of contemporary conflict and our lack of moral compunctions regarding fictional warfare. Of course, Battlefield 1 is no less fictional than Battlefield 4, and watching five minutes of game footage will more than prove that. This is World War I reimagined as a frictionless machine, an endless breakneck charge. The question of historical accuracy seems comical when the game fails to depict reality in any sense. This is something that has become invisible to those of us who play games (and war games) on a daily basis, used as we are to the selective “realism” they choose to depict, but to anyone else this roar of sound and fury is as real as Tom and Jerry (albeit with a photorealistic sheen).

So why is it that the unpleasant feeling remains, the knot in the pit of our stomach that unexpectedly appears at a violent bayoneting? Perhaps it is because we have been well trained in the gravity of old wars. Both through our education systems and the rituals of our Western societies we have been imbued with an unevenly weighted respect for the “Great” wars of our past. Symbols of heroism, drama, and meaningful suffering, they have been transplanted with fictional versions of themselves, where no death was meaningless, no battle without merit. Our over-education in these wars has made their suffering oddly familiar to us: the announcement of Battlefield 1 was greeted with many a dark joke about mustard gas and death by disease in muddy trenches, but you will fail to find similar jokes about how the soldiers of Battlefield 4 or Call of Duty are more likely to die by suicide or transport accidents than enemy fire.

a violence towards history

While our own generation has been dying on foreign soil since the turn of the century, we have been happily consuming videogame depictions of these wars or analogs of them, made palatable by their status as speculative fiction. To jump to claims of historical inaccuracy and disgust around Battlefield 1, but not this long history of misrepresentation is a hollow gesture, one motivated by a questionable respect for our “sacred” conflicts of the past. Should our allegiance not be to our own time, own generation? The truth is we don’t believe in our conflicts, or they are too complicated for us to invest in, and their imagery is tired, worn out, lost in the cacophony of news video and cinema.

The World Wars represent something we can believe in, to quote theorist Jean Baudrillard: “today one has the impression that history has retreated, leaving behind it an indifferent nebula, traversed by currents, but emptied of references. It is into this void that the phantasms of a past history recede, the panoply of events, ideologies, retro fashions – no longer so much because people believe in them or still place some hope in them, but simply to resurrect the period when at least there was history, at least there was violence (albeit fascist), when at least life and death were at stake.” And so, it is the same trained respect, the same pseudo-religious power of these conflicts that leads us to return to them again and again. The ideas that are making critics uncomfortable with Battlefield 1 are the same ideas that motivated its creation in the first place: the mythical status of historical wars.

The violence that Battlefield 1 is contributing to is then not the real violence of war, neither is it a violence towards the memories or realities of those who fought and died in World War I. It is instead a violence towards history, an aggressive reinterpretation of our past in our own image, so as to suggest that our contemporary logic possesses some kind of truth. Like Far Cry Primal—which as Kill Screen’s Matt Margini pointed out, was somehow searching for an origin point for its own logic of hunting, killing, and upgrading—Battlefield 1 is an attempt to dovetail the origins of the series’ own gameplay and logic with the origins of mechanized mass war.

When the game’s lead designer Daniel Berlin says the team wishes to “challenge some preconceptions” about the first World War he means they aim to reshape it for their own means. But before you take this as a weighty accusation, it’s important to understand that this violence towards history has been around for longer than we realize. It has operated in high-school classrooms and on TV documentaries, in cinemas and through videogames. It is what has shaped our relationship to our own past, what has given us our understanding of the world. As a child I built models of Messerschmitts and Spitfires, Kubelwagens and Mark V tanks, decorating my room with hand-painted dioramas of the battle of Stalingrad or Verdun. I can’t help but feel affectionate towards these killing machines, to the angles of their plate armor or their shades of olive drab. We are more comfortable with old war when it is presented to us with noble bugles in the backdrop, black-and-white grain flowering beautifully across images of advancing artillery. We are conditioned to believe, to quote Baudrillard once more: “History is our lost referential, that is to say our myth.”

So let’s not trick ourselves into thinking that Battlefield 1 is even able to trample the memory of our ancestors, or that it disrespects the gravity of mass killing: that history was lost to us long ago. If we do so, we are simply playing into the game’s own borrowed gravitas. And by doing so we risk missing what is in front of us, the reality of the situation, which is that Battlefield 1, in its reconditioning of our great myths, tells us more about us, now, and our endless quest to find “new” things to sell to each other than it ever will ever say about the dead of the Somme or Verdun.

The post Listen, Battlefield 1 owes nothing to history appeared first on Kill Screen.

Live the life of a lonely introvert in a hikikimori simulator

The blinds are drawn. A tiny sliver of light manages to brighten up the room, casting a jagged shadow against the wall that trickles down the length of your bed. A brightly colored poster and several polaroids decorate the walls. A casual guitar riff plays softly in the background, accompanied by the sound of the outside world—traffic and pedestrians. This is the beginning of Hikikimori Simulator (alternatively named Solitude), a “five minute experience” by Alexandre Ignatov. “Hikikimori” is a Japanese term that refers to (usually male) reclusive adults/adolescents who pull away from social interactions. You play as a man who has withdrawn from society.

hurtful words taking jabs at your hermit status

The environment to explore is limited but there are objects to be picked up, things to be examined, and pieces to be put together that create a larger narrative. Solitude says so much through exploration and observation. For example, there are a lot of light sources in the room you are confined to—string lights frame the space above your bed, with a table lamp nearby a ceiling light cast over it all. You can go around flipping switches to help brighten up the room, which gives the illusion of happiness. However, going through your things gives off an entirely different feeling.

A small plant sits on the windowsill, the only other sign of life in the space. Several books adorn the shelf above your desk, along with dirty dishes and leftover food that hasn’t been touched. Emails on your laptop reveal a date gone sour and hurtful words taking jabs at your hermit status. Diary entries go through your inner monologue, which echoes the thoughts of a lonely introvert. Without spoiling what happens after you decide to leave your room, Solitude succeeds in capturing the anxiety and the self deprecation that comes from isolation.

Play Solitude for yourself here.

The post Live the life of a lonely introvert in a hikikimori simulator appeared first on Kill Screen.

A man and his mecha fall in love in Titanfall 2

Though a thin game in terms of what it offered overall, Respawn Entertainment’s Titanfall (2014) was a well-balanced, quick-paced multiplayer shooter in a time where run-of-the-mill Call of Dutys and Battlefields ruled, with not much else to spare. But one of the largest grievances from fans of Titanfall was not only the sparse diversity of its multiplayer modes—but its entire lack of having a single player campaign.

In the newest footage of its follow-up Titanfall 2, revealed during EA’s press conference early Sunday afternoon, Respawn finally confirmed that very inclusion (even if the trailer did leak earlier than expected).

In the single-player trailer, a (non-sentient, according to an interview with Polygon) mecha bemoans his former pilot dying. He seems sad about it, or at least, as sad as a cognizant mecha can be. A new pilot—a riflemen who goes by the most generic of names: Jack Cooper—is the mecha’s new lifelong companion in shooting bad guys and fighting monster things. A disembodied woman’s voice barks at the mecha, asking why the robot paired with another human without running it by her first. To which it gravely replies, “We had no other options.” Because, you know, war and monsters probably. The trailer then shows some more human x mecha bonding, maybe falling deeper in love with one another, culminating into some good ol’ pilot hopping into mecha and shooting things action.

Is there true love between this unlikely pair?

There’s more heightened action in the trailer, like Cooper falling in an endless sky BioShock Infinite-style and the mecha saving him in the nick of time. There’s more shooting things, because at the crux of it all, that’s where Titanfall shines. (It plays well.) But in so many contextually-dry multiplayer-heavy games, the concept of a mecha and a pilot is perhaps the most fruitful to expand. It’s not just another war game, or a tone-deaf cops versus robbers romp.

It’s doubtful that Titanfall 2’s story will hit the heights of other mecha-addled tales, such as Hideaki Anno’s blissfully dark Neon Genesis: Evangelion (1995). Nonetheless, it’s a welcome change to what fans and critics saw as an issue with the first game, and remedying that by actually exploring the relationship between a pilot and their killing machine buddy with a programmed mind of its own. Like, is there true love between this unlikely pair? Is it just a solid friendship, complete with the pilot remarking, “Man, you really shot the hell outta that guy” with maybe a subsequent fist bump? Or is the mecha simply just programmed to the beck and call of its human companion, without a genuine feeling beyond that? I suspect we’ll find out in Titanfall 2’s campaign, when the game launches in October.

Titanfall 2 will be released on PS4, Xbox One, and PC on October 28th.

The post A man and his mecha fall in love in Titanfall 2 appeared first on Kill Screen.

Sympathy for the Spoon-Collector in The Witcher 3: Blood and Wine

“I like rusty spoons” whispers Salad Fingers, in his bizarre quavering voice, those ovular eyes pointed in precisely the opposite direction from each other. “I must find the perfect spoon.” Pleasingly creepy and unhinged, David Firth’s crudely-made web series appears, at this distance of a decade, as a fairly distinctive generational marker. That’s why it seems an unlikely coincidence when, in The Witcher 3: Blood and Wine, we find a creature with exactly the same desire. Holed away in a overgrown house is the Spoon Collector, a skeletal horror wracked by a supernatural curse that has it searching for the “perfect spoon” to sate its hunger. It is typical Witcher territory; a derelict home carefully populated with clues, journals and letters, leading to an inevitable encounter with a dangerous monster. The fact that among these clues are more than a few rusty spoons feels like it cements the Salad Fingers reference in place. But while this would seem to condemn the Spoon Collector to being little more than a joke, a silly reference in an expansion with a fair share of weird and frankly crappy jokes—including a character whose initials are “D.L.C.” and another whose name is “Barnabas-Basil Foulty”—this is a creature far more slippery than that.

As a spotted-wight, an emaciated, distorted breed of creature so terrifying that we are told they were hunted to extinction by the witchers long past, the Spoon Collector makes for an unpleasant sight. Tucked away in a wardrobe in a corner of its lair, Geralt watches as it stumbles around with an unpredictable gait, tending to its noxious cauldron. It’s a scene with some wonderfully old-fashioned horror-movie tension; the half glimpsed monstrosity watched as it goes about its dark deeds. But as the Spoon Collector approaches Geralt’s hiding place with madly roving eyes, the scene transforms. Here, we are given the chance to attack, or to try to lift the creature’s curse. Both choices lead to wonderfully bizarre events. Choose to attack and you’ll trigger a battle where the Spoon Collector swims through a pool of spoons like a cutlery-obsessed Scrooge McDuck. But attempt to lift the curse instead and Geralt has to sit down to dinner with the damn thing. Suddenly, the creature transforms from sinister to slapstick, as the Witcher tentatively guides the creature into sitting with him, like teaching a child to eat through imitation alone. Its also an oddly affectionate scene—not just between Geralt and the creature, but between developer CD Projekt RED and their subject matter. The Spoon Collector’s careful animations and expressions, its wobbling gait and comic timing all pointing to a loving level of craft and attention expended on the Spoon Collector, one that delights in the grotesque and fantastic potential of man-eating monsters.

This is a creature far more slippery than that

///

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt’s (2015) base game is filled to the brim with peasants. Stand still in one of its muddy, godforsaken villages and you can watch them mill around, gabbling on about the weather or their ailments, spouting aphorisms for the downtrodden: “Nothing hurts so much as life,” observes an abused servant. “Even the gods weep for our misfortune,” grumbles a rain-sodden farmer. “No such things as bad ships or bad weather,” croaks a wizened Skelliger, before adding: “only worthless fucking sailors.” It’s an atmosphere that falls somewhere between the silly humor of Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) and the deranged, mud-caked mutterings of Alexei German’s Hard to be a God (2014). Like German’s masterpiece it’s also hard to place these interjections on a scale that stretches from perverse to profound. This is what gives the game much of its rich character, especially in side quests and witcher contracts that have Geralt rubbing elbows with the underclass. Even the games more notable questline, the much-praised Bloody Baron, hinges on this atmosphere of medieval grubbiness. That’s why, when The Witcher 3: Blood and Wine takes us off to a fairytale kingdom of knights and nobles, complete with a Disney Cinderella Castle at its center, something feels missing. Unsurprisingly, the knights turn out to be asinine and vapid characters, their appearances usually involve them acting as likely foils to Geralt’s now well-worn snarky comments. Unfortunately, these exercises in gentle fun-poking have none of the grit and charm of Geralt’s dealings with bloody-minded peasant folk, and in the end, the expansion’s humans end up fading into the background. However, rather than losing its identity through this shift, Blood and Wine takes this opportunity to let its monsters take more of the spotlight.

The Spoon Collector is just one among many of these monsters. From the very start, Blood and Wine throws wonderful monster after wonderful monster at you in a run of tricky battles, including the Dark Souls-like giant Golyat and the ancient geological structures of the Shaelmaar. Each is elegantly animated, distinctively designed and carefully back-storied. Together they are a strong reminder that monsters are the true heart of the Witcher series. However, while these beasts are fearsome enemies and strong works of design, their memorable nature stems from CD Projekt RED’s pursuit of sympathy for these creatures. The gigantic Golyat, according to a legend found in the game world, is actually Luis Alberni, a knight punished for his vanity by the Lady of the Lake by being transformed into a misshapen giant. Meanwhile the Shaelmaar, a rare and powerful creature from deep within the earth, is simply being used for entertainment in the Duchess’s tournament ring, its sensitive hearing tormented by the roar of the crowd. Again and again the player is given reasons to be sympathetic towards these creatures, to find explanations for their actions, pity for their fates. In short, the monsters of The Witcher 3: Blood and Wine are not beasts, but characters, even if they might not speak a word.

This attitude is part of a long tradition of finding the human in monsters, perhaps most recently and compellingly pursued by director Guillermo del Toro. From the ghosts of The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and the faun of Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), to the ensemble cast of freaks and creatures in the Hellboy films, Del Toro finds his strongest characters in the supernatural, the lost and the monstrous. Combined with his precise eye for strong design and love of practical effects (perhaps best evidenced in Hellboy 2’s wonderful Troll Market) Del Toro’s monsters are built for more than just mass slaughter or jump scares—they are explorations of his own sense of identity, his own love of the macabre. Del Toro has often said that his vision of Hellboy, a character much like the witcher Geralt, trapped between the worlds of monsters and men, is his most personal work. That might seem strange for a such a pulp film series, but Del Toro sees Hellboy as “a monument to human vulnerability.” And perhaps it is this vulnerability that makes his monsters so compelling, even when they are simultaneously terrifying. In a comprehensive interview in 2011 with the New York Times, Del Toro said “I’m not just Hellboy—I’m the Pale Man, too.” The Pale Man, the eyeless child-murder of Pan’s Labyrinth, and one of contemporary cinema’s greatest monsters, is not the first creature you would think of as relatable. But for Del Toro this creature was an image of pure and primitive greed, stemming from his own struggle with his weight. The Pale Man, in Del Toro’s eyes, was not just another cool idea for a freakish beast, but an expression of something undeniably, even unpleasantly, human.

Blood and Wine takes this opportunity to let its monsters take more of the spotlight

///

I don’t want to spoil the fate of the Spoon Collector, but there is something of the Pale Man in its nature. This creature too is formed of a very human failing, and finds its cure in the most positive human aspect of Geralt, his compassion. This compassion is something that, if the player chooses, they can show to many of the creatures of Blood and Wine. In fact, while there are irredeemable horrors in its bestiary—corpse-eaters and child-killers, creatures from nightmares and fever-dreams—Blood and Wine finds its strongest moments in its discussions of humanity through the lens of monsters. Emiel Regis Rohellec Terzieff-Godefroy, or Regis for short, plays a large part in these discussions. A higher vampire who no longer drinks the blood of the living, and an old friend of Geralt, Regis’ softly-spoken manner and composed attitude betray a fierce intelligence. Voiced in what is a rare understated performance by Mark Nobel, Regis brings discussions of the value of humanity to the fore, his immortal nature and powerful abilities making him unable to fully comprehend the short and ugly lives of humans. He is compassionate to a fault, loyal and intelligent, and yet he is by definition a monster. His presence among the oversaturated colors and more luridly bizarre quests of Blood and Wine is a pleasant one, shifting the expansion’s focus towards Geralt’s distance from the humans he seeks to protect, and his similarities to the beasts he slays.

This concern of The Witcher 3: Blood and Wine creates an interesting relationship to the themes and strengths of the base game. It suggests that the strength of the Witcher series neither lies in its fantastic monsters nor its richly drawn peasants, but somewhere between. It finds the monstrous, the ugly, and the grotesque in humans, and the redeemable, expressive elements of monsters, and in doing so it bridges the gap between them. However, rather than using this idea to damn both sides, it finds sympathy for its subjects. That sympathy can just as easily be for the terrifying Spoon Collector and its victims or the Bloody Baron and his abusive acts as both a father and husband. And it is that sympathy that opens us to the strongest message of The Witcher 3 games, that like it or not, humans and monsters are closer than we could ever imagine.

The post Sympathy for the Spoon-Collector in The Witcher 3: Blood and Wine appeared first on Kill Screen.

At E3, FIFA 17 concedes that soccer is boring

Soccer clubs are fundamentally in the content business. Their prime offering is a match—90ish minutes of action delivered once or twice a week—but they have to fill in around the edges. This is how it came to pass that clubs started releasing exclusive video content through their own online portals—anything to fill the void between matches.

Soccer media, more obviously, is in the content business. It, too, must reckon with the fact that relatively little time is taken up by the sport itself. It, too, has sought to fill this void with pseudo-events: endless talk shows and things like “transfer deadline day” to dress up slow news days.

The potential pratfalls, like the game itself, seem sanitized

It was only ever going to be a matter of time, then, until soccer videogames also clued into the sport’s inherent limitations. If you can blitz through entire seasons in a few days, then clearly videogames are leaving plenty of content on the table. FIFA 17’s “The Journey”, unveiled on Sunday at E3, is an attempt to fill that void. It tells the story of a player, Alex Hunter, through his off-the-pitch trials and tribulations. You guide Hunter though his interactions with families, other players, and agents. In principle, “The Journey” takes the traditional sports game idea of a career mode and turns it into an entire life.

But what life is that really? The trailer and information EA released at E3 offer little indication of a fully rounded life. There are opportunities for failure, but the game shows no signs of engaging with all the ways that promising athletes can fail. The potential pratfalls, like the game itself, seem sanitized. Sure “The Journey” is something of a “reality” show—as 2K Sports previously attempted with NBA 2K16—but reality is more circumscribed than it even is on TV.

Would EA let Alex Hunter decide to do something else with his life? Would EA let Alex Hunter succumb to drug addiction? Would EA’s Alex Hunter become embroiled in the sort of sexual assault allegations levied against multiple Spanish internationals on the eve of Euro 2016? EA’s “The Journey” does not seem willing to go there, and so long as it is not, it is likely to remain as awkward as all the other parts of the soccer content ecosystem—items designed to fill around the 90 minutes of on-field action but never fundamentally challenge it.

The post At E3, FIFA 17 concedes that soccer is boring appeared first on Kill Screen.

Overwatch and the pleasure of transmedia narratives

Before Winston, a glasses-clad gorilla scientist, was leaping across maps to crush his enemies in the chaotic multiplayer battles of Overwatch, he was merely a young ape with big aspirations and an affinity for peanut butter. But you wouldn’t know that from merely playing the game.

You’ll find no calculated, story-driven campaign in Blizzard’s competitive team-based multiplayer shooter. Overwatch’s character-driven narrative is instead trickled elsewhere: in genuinely endearing animated shorts, character-focused one-off webcomics, and short website-bound character biographies. The latter-most isn’t uncommon within videogames, the second less so, and the first is the most uncommon of them all, the three combined serve as the primary way to tell the story behind Overwatch. What’s significant is that none of these storytelling techniques involve the actual game itself—outside of a minor pre-start menu cutscene explanation— and narrowly avoid the trappings of bland expository lore dumps, as was the case with the repetitive Destiny (2014), and other similar multiplayer-focused games.

In separating the narrative from the game itself, Blizzard’s exercising a new kind of transmedia approach to storytelling. Transmedia storytelling, a phrase originally coined by scholar Henry Jenkins, is the practice of a narrative’s world-building across different platforms. This doesn’t mean sequels. It means literally peppering a story across comics, shorts, or whatever else, just as Overwatch has (and even the Halo series to an extent). “Most often, transmedia stories are based not on individual characters or specific plots but rather complex fictional worlds which can sustain multiple interrelated characters and their stories,” writes Jenkins on a “Transmedia Storytelling 101” blog post. “This process of world-building encourages an encyclopedic impulse in both readers and writers. We are drawn to master what can be known about a world which always expands beyond our grasp.”

When playing Overwatch, the player is absorbed by its radiating positivity. It’s a world filled with lively color and energetic, playful competition, much like Nintendo’s creative kid-friendly ink-shooter Splatoon (2015). The game doesn’t encumber itself with “killing” as so many other grisly shooters do. Additionally, it doesn’t encumber itself with story either. The game is enjoyable without the weight of a narrative shoehorned through it, just as Valve’s similar team-based shooter Team Fortress 2 (2007) did many years before it in the form of its “Meet the Team” shorts. By separating its narrative entirely, the game is given room to focus on its frenetic action at hand.

The game is enjoyable without the weight of a narrative shoehorned through it

Overwatch, as we play it, takes place 60 years in the future. About 30 years prior to that point in time, the Overwatch team was initiated, a government-funded group of heroes, organized to fight against the rebellion of Omnics, a type of self-improving sentient robot. A couple decades later, the rebellion had been quashed, “peace” was semi-restored, and Overwatch was made illegal, scattering the many heroes. That’s until ominous characters (namely Reaper and Widowmaker, as seen in the game’s animated shorts) start snooping around, wreaking havoc, and drive Winston to make an impossible call to illegally reinstate his former teammates. Overwatch is back to save the world. Of course, this dense information is gathered nearly everywhere but inside the game itself.

The most common comparison tossed around about Overwatch’s garden variety story is to Pixar’s lovable superhero romp The Incredibles (2004). Yet, it also has a bit in common with Alan Moore’s renowned, dark graphic novel Watchmen (1987). Both The Incredibles and Watchmen tell tales of post-superhero disappointment, wherein being a hero is now outlawed by the government, and former heroes turn to vigilantism, until a new type of war pulls them back in. But where Watchmen excels in its cynicism of the world and governments, The Incredibles and Overwatch flourish in their idealized promises of hope.

Surprisingly, this distant approach to the game’s storytelling feels all too familiar for a different reason. When I think of the games I loved as a kid, they were nearly all colorful action-oriented platformers: Sonic the Hedgehog (1991), Crash Bandicoot (1996), Super Mario World (1990). There was no explicitly-told story between any of these games, but they were all led at the helm by an endearing character or two, and a dastardly evil for them to chase. These are characters that clung to me and that I loved with all my heart as a child.

How we consume narratives transcends mere pages and screens

As with most media as a kid to preteen, when I adored something, I’d always seek out more. It didn’t matter whether it was Harry Potter or emo band-related fan fiction, or anime-cultivated music videos—I always wanted more, more, more. Absorbing a fiction through a lone medium was never a satisfying option. J.K. Rowling, author of that aforementioned boy wizard series, leaped at the chance to expand her universe. With an illustrated and short story-filled site-appendage to the series, several minor book spin-offs, and even a new film adventure in the works, for Rowling, Harry’s story didn’t end with a loving wave from Platform 9 and 3/4s in the Deathly Hallows (2007).

This is the power of transmedia storytelling, and how we consume narratives overall—transcending mere pages and screens. Transmedia storytelling begats the ability to give life to a story beyond its concrete narrative, even trickling it elsewhere in lieu of the primary medium itself, as Overwatch has. Blizzard uses the same universe-building, medium-transcending approach with Overwatch as Rowling does with Harry Potter, reaching far-and-wide to expound its storytelling. Yes, I love playing as Widowmaker, but how about watching an animated short of her battling Tracer in an effort to assassinate an Omnic leader, creating further tension between the two storied enemies? Or reading a comic about a mission of Symmetra’s that goes terrible awry, leaving her with insurmountable guilt over accidentally injuring a bystander? Hell yes.

Overwatch returns that child-like glee of admiring a character for the simpler things: their character design, their cheerful (albeit, sometimes goofy) demeanors, and most of all, how I feel while playing them: confident and happy. Games were an escape for me as a kid, because I could imagine myself as the character themselves, or at least as a friend of theirs. In transmedia storytelling, it’s easy to surround myself completely with whatever medium I admire, fully embracing my “encyclopedic impulses,” as Jenkins once wrote. Overlaying the very textures of my everyday reality with fictional fluff. With Blizzard’s narratorial distance, I’m regranted that innocent pleasure, but luckily without feeling overwhelmed, and given enjoyable side romps for when I want to seek out more.

For now, I like my Overwatch with a side of story. An Overwatch where characters are ripe for kid-like fancying. Like how I may want to be Mercy, keeping a watchful eye on my friends, and healing them at every turn. But in all actuality, I’m probably most like D.Va, charging in without a thought, ready to take on the world no matter its consequences.

The post Overwatch and the pleasure of transmedia narratives appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers