Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 118

May 19, 2016

It’s time to confront the uncanny potential of virtual architecture

A room enclosed on all sides sits naked in grayspace. Inside is a trunk, a bed, a tube, a radiator, a light, and little else. A sharp sound swells and suddenly the room snaps out of place. Now it is upside-down. You can’t even enter through the open doorway, barely able to peer inside through the window, the objects once sat neatly now thrown into disarray across a ceiling that is now a floor. The sound comes again and the room changes, again. It sits as it did before, at the center of a square cut of rock floating in a void, but now a duplicate of the room slumps on one of its corners at a diagonal like a schoolyard bully pinning down their victim. At the next swell and switch you are returned to a single room; this time it has abandoned the floor and hangs above you in a brutal pose, suspended in emptiness.

To understand Pippin Barr’s latest project, titled v r 1, it is best to know where it came from. Barr’s fidgeting digital room, which dissembles and rebuilds itself a number of times, is a duplicate of “u r 1,” which is a single room located in Gregor Schneider’s childhood home in Rheydt, Germany. It is said that inside that house there is another room with no door handle on its inside, and only a decorative knob on the other side—if the door is shut, the person inside is trapped forever. This is only believable because Schneider has, since the age of 16 when his father died, relentlessly re-renovated and reconfigured his home into a claustrophobic maze of crawlspaces, fake partitions, and dark corridors. Rooms are built inside rooms, colored lights suggest different times of day throughout the interior, and in the cramped and dank basement there is a noticeably incongruous disco ball hanging from the low ceiling.

u r 1, via Portikus

It is unknown as to why Schneider was compelled to this project now known as “Totes Haus u r” (Dead House u r), but many have perceived it as a result of trauma; his father’s death playing on his mind and manifesting as a psycho-architectural passion. That is conjecture, and in any case, Schneider has a keen interest in Expressionist art, fascinated especially with more morbid works during his younger years that involved screaming human faces and auto-mutilation (the urban legend of John Fare is an example of his taste). And so what some see in “Totes Haus u r” is a transformation of Schneider’s interests into interior design—it’s this that has attracted museum and art curators to his home.

If you disregard the accusations of perceptual disorder and mental unrest, Schneider’s work and vision becomes wholly artistic. Interior designer and writer Keehnan Konyha, who visited Schneider’s house and interviewed him, provides insight on the German artist’s chief interest: “He is interested above all in forms of existence that escape perception—substances, spaces, objects, and qualities that remain hidden. When one wall is built in front of another, a space is created between the two. […] The invisible works are just as significant as the visible ones to Schneider, and the very distinction between the two might be of minor importance to him.”

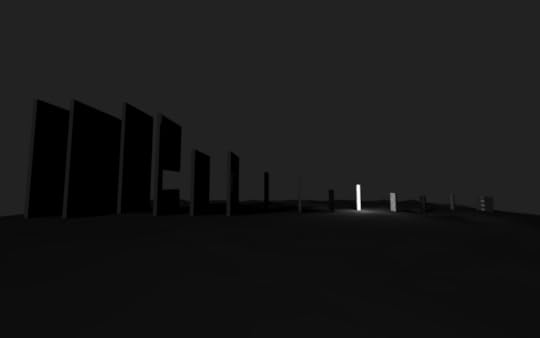

the uncanny and creepy effects of Schneider’s room configurations

The suggestion is that Schneider is actively testing our boundaries, quite literally pushing and shifting them to see how we, in our physical bodies, are affected by different forms of architecture. Navigating his home requires squeezing through gaps and crawling through muck, but perhaps more importantly, a lot of the spaces are inaccessible as they are hidden behind newer walls or barricaded by concrete. The Guardian‘s Jessica Lack adds to this that our fascination with the house “reveals how compelling we find the most disquieting aspects of the human condition.” She doesn’t see only a house but a metaphor for the interlocking parts of our psyche, going so far as to seeing Schneider’s basement as alluding to the nefarious under-house nightmares of Fred West and Josef Fritzl. The spaces hidden by layers of walling are the parts of our mind we lock away if this interpretation is to be carried further.

With v r 1, Barr hoped to replicate Schneider’s cluttered interior space in a virtual environment, and to see how digital architectural tools grant further experimentation. “I was most interested in seeing how creating doubled spaces differs in a virtual setting,” Barr writes, “notably the idea that doubling is trivial in this context, amounting to nothing more complex or laborious than ‘cut and paste’.” The goal was to achieve the uncanny and creepy effects of Schneider’s room configurations but the minimized labor means wilder restructuring was required—placing a room inside a room isn’t as impressive in a virtual context as it is in a cramped house next to an industrial complex in Germany.

Barr’s best efforts come when he lets the room forget its orderliness. While upside-down, its contents sprawled in the heap they fell into, it seems as if a sleeping man has angrily tossed over to rest on a more comfortable side, or, more grotesquely, they resemble the collapsed organs of a retired body. The room takes on a menacing quality when hanging over you; a beastly monolith suddenly woken from its slumber due to a human opening a cavity inside it to use as a home. A personal favorite, though not particularly unsettling, is when the room arranges its walls and objects in a neat line from tallest to shortest across the ground. It’s reminiscent of how flat pack furniture is sold in parts to be screwed together. In this occasion, it acts as a reminder that every wall, every brick, every object placed in a room is given meaning through our perception of it. Seeing each wall panel as an individual object breaks the illusion that the virtual room has agency or personality of its own, not even when it is constructed as part of a living space—all meaning and purpose is of our own projection.

Schneider was met with controversy in 2008 upon saying that he wanted to build a space in a museum that people could die in. His reason wasn’t for gruesome display but so that people had the option to die somewhere beautiful rather than be subjected to the clinical tones of a hospital room. He wants to subvert the customs that have grown as to how we use and inhabit architecture and home spaces. Barr’s project ventures into the same territory but has us turn our attention to the virtual equivalent and the vast potential it has to exist beyond their human trappings, exemplified by four walls joined at the corners, crowned by a ceiling.

You can play v r 1 in your browser. Alternatively, you can download it for Windows, or download it for Mac.

The post It’s time to confront the uncanny potential of virtual architecture appeared first on Kill Screen.

Hurray! Keita Takahashi has made a wonderful new plaything

At the Game Developer’s Conference in 2013, I cruised through the expo floor areas on a student pass. With such a limiting pass, I wasn’t able to do much. That was, until I stumbled upon Tenya Wanya Teens (2013), a never-publicly-released experimental party game from none other than game designer Keita Takahashi, of Katamari Damacy (2004) and Noby Noby Boy (2009) fame, and composer Asuka Sakai (also, incidentally, his wife).

Tenya Wanya Teens is fun in its purest form. The game has a strange controller, a panel with 16 multicolored buttons, and a joystick for moving characters around the environment. It was never designed for widespread use. That’s the tragedy. But at the very least, I have a memory of perhaps the most joyous game I’ve ever played. A game rooted in the bizarre and even mundane—like competitively studying or swiping fish out of a river as a grizzly bear.

Woorld is another notch in the belt of Takahashi’s absurd, ever-charming imagination

Takahashi sees the beauty in everyday things. His first two games in the Katamari series, exemplified this trait, as did nearly every game following those. His endearing daily blog catalogs his life in San Francisco, and consists of him taking a photo or gif every day, and drawing one of his many adorable characters on it. Takahashi’s newest project, Woorld, in collaboration with Vu Ha, Ryan Mohler and Brandi House, is just another notch in the belt of Takahashi’s absurd, ever-charming imagination.

Woorld is an Augmented Reality (AR) project, bringing Takahashi’s adorable art into a fresh, interactive living space. Using technology from Google’s Project Tango, Woorld blends the whimsical art of Takahashi and the creative, experimental play of AR and virtual reality technologies, creating a wholly unique experience only deliverable from the Funomena crew. The game isn’t a solitary experience either, as anything the player creates and places in their real-world environment can be instantly shared via a shared screen with friends and family.

Like rolling up a lone bear to create the bear-iest star in the galaxy, GIRL completing her 2,489 day journey to unite the solar system in late 2015, exploding hand-holding, Woorld’s AR-driven antics are bound to join the leagues of other Takahashian experiences. As ever, I can’t wait to see what woorlds he’ll create next.

You can follow Woorld’s on-going development over at Funomena here . Takahashi’s other new game, Wattam , should also be out this year at some point.

The post Hurray! Keita Takahashi has made a wonderful new plaything appeared first on Kill Screen.

The future of archaeology starts with No Man’s Sky

This is a preview of an article you can read on our new website dedicated to virtual reality, Versions.

///

Destructive treasure hunters like Nathan Drake and Lara Croft tumble through decadent crypts, dismantling rare artifacts in their wake. Their scrabbling work, however incidental, is the antithesis to the careful field of archaeology. Yet, in marketing materials they’re labeled both as explorers and, yes, archaeologists. It’s for reasons like this that I’ve found myself, as a student of archaeology, increasingly disillusioned with the way videogames treat artifacts and history.

The problem is that these types of games tend to disregard preservation. Our favorite protagonists utilize priceless pieces of history as landscape to be clambered over and, inevitably, destroyed. While no one is upset enough to protest, this does seriously misrepresent the actual archaeological process, which is especially disappointing for a medium that presents a potential chasm to fill with exciting, intersectional research. This is the basis of archaeogaming.

Archaeogaming, as defined by scholar Meghan Dennis, is “the utilization and treatment of immaterial space to study created culture, specifically through videogames.” It’s a new field of study that is only now starting to dig its way into academia. Three books on the topic are scheduled to arrive in 2017 alone, the latest of these being The Interactive Past, which was successfully crowdfunded by the VALUE project on Kickstarter.

READ THE REST OF THIS ARTICLE OVER ON VERSIONS.

The post The future of archaeology starts with No Man’s Sky appeared first on Kill Screen.

Apple says politically-charged Palestinian game isn’t a “game” at all

Liyla and the Shadows of War is a game about a young girl living in Gaza during the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict. Unfortunately, I can’t tell you much more than that because Apple has declared it too political to count as a game in its App Store.

On Tuesday afternoon, developer Rasheed Abueideh said Liyla had been rejected for not being appropriate for the “Game” category and shared a message from Apple that read:

As we discussed, please revise the app category for your app and remove it from Games, since we found that your app is not appropriate in the Games category. It would be more appropriate to categorize your app in News or reference for example. In addition, please revise the marketing text for your app to remove references to the app being a game.

A version of this story comes up every few months, and the same answers generally apply. Much of the silliness of declaring that Liyla is not a game is also true of banning all games with the confederate flag, even those that use it in an appropriately historic manner. It is nevertheless worth considering this latest absurdity because the gradual accretion of silly incidents allows us to gain a limited insight into the closed world that is Apple’s App Store.

Apple’s walled garden is… designed to ensure inconsistencies

Apple’s power over the app ecosystem is attributable, in part, to both its size and imprecision. According to research by Parks Associates, Apple represents 40 percent of the US smartphone market, which makes it hard for developers to simply ignore the Apple and its app ecosystem. For all but the most technical of users, the App Store is the only way of adding apps. Apple’s guidance to developers, however, is hardly helpful. The company’s guide is peppered with vague statements such as:

We will reject Apps for any content or behavior that we believe is over the line. What line, you ask? Well, as a Supreme Court Justice once said, “I’ll know it when I see it”. And we think that you will also know it when you cross it.

Really?

Potter Stewart’s description of pornography, it should be noted, has not held up as a rigorous system for discussing explicit content. Standards vary by community, and allowing one group to judge the material produced by another usually ends badly. The community standards approach also tends to work out especially poorly for underrepresented minorities. All of the flaws of the legal model Apple cites in its developers guide can be seen in the Liyla incident: the line is not apparent to everyone, and here it has been used to reject a story about a Palestinian girl.

The squishiness of these rules puts creators at a disadvantage. All they can do is guess what Apple thinks based on past decisions, and even that may not be enough. As with content guidelines on social networks, this sort of abstract regulation allows for capriciousness with little recourse. This structure encourages an anticipatory form of compliance, or what you might call risk aversion. Apple’s walled garden is, in a sense, designed to ensure inconsistencies.

We ask too much of the oppressed

It is therefore easy to point out the various contradictions in Apple’s rulings. When I played it in February, the emphatically political Peacemaker: Israeli Palestinian Conflict, was available from the App Store. Why did it make the initial cut, but Liyla did not? (Peacemaker was unavailable as of Wednesday night. UPDATE May 19, 2:36 pm: Peacemaker‘s developers have confirmed that there is “nothing interesting or political” behind the app’s disappearance from the App Store and that it will return shortly.) You can ask these questions for ages, and they’re all fair, but it might be simpler to conclude that this is how the App Store works: a series of poorly-worded policies that are usually used to steer games away from hot-button issues and that tend to overreact when the political climate gets heated.

Are games, as Abueideh suggests Apple sees them, inherently apolitical? No. Moving on.

The more salient point regarding the Liyla debacle is that life is political, whether we like it or not. Plenty of people would love to lead largely apolitical lives, but that is luxury few can ever access. In a curious way, then, Apple, through its ham-fistedness, has upheld many of the thematic elements of Liyla that prevent it from being listed as a game. Liyla is the story of a 14-year-old girl stuck in the middle of the Israeli-Gaza war. The images released by the developer show shelled buildings, rockets, and military vehicles based on actual events. Abueideh has shown these images side-by-side with footage from the conflict and the resemblance is striking. Reality, whether Apple likes it or not, is political. If you lived in Gaza at this (or any) time—even as a 14-year-old girl—your existence, even the games you played, could not be divorced from politics. There are plenty of people who would like to escape politics and its consequences, but for those living outside Apple’s walled garden that is not a viable possibility.

We ask too much of the oppressed: We ask that they not resort to anger or violence; we ask for more and more proof; we ask for shows of patience. The demand to not be too political is just another entry in this series of asymmetrical requests: your existence is wrapped up in politics, but never say as much. These are all impossible demands, but they are made nonetheless and derogation has its consequences. To ask someone to be less political is, in many cases, to ask them to accept the status quo. Liyla, as best I can tell, is not a hugely radical work, but it is political because that is unavoidable. We ask for a lot, but we cannot ask humans who make games or the characters who figure in games, to be apolitical.

You can download Liyla and The Shadows of War on Google Play.

The post Apple says politically-charged Palestinian game isn’t a “game” at all appeared first on Kill Screen.

How VR will change the way we create

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

The advent of the internet created a whole new mode of self-expression, from digital and gif art to fan-fiction and fan art. Now, new virtual reality (VR) tools are primed to inspire yet another era of creators, both amateur and professional, by inviting them to step into their own inventions. Nowhere—so far—is the medium’s artistic possibilities more evident than in Tilt Brush, Google’s VR painting app that launched on the HTC Vive in April. “Combined with the newest generation of motion controllers and input technology, VR has the potential to be the most intuitive and natural creation platform artists have ever experienced,” said Drew Skillman, who together with his partner Patrick Hackett, created Tilt Brush in their San Francisco-based design studio Skillman & Hackett before selling it to Google last year.

The app transforms a pair of motion-tracking controllers into fluid and dynamic paintbrushes, allowing users to paint luminous 3D masterpieces like no other. Brushstrokes levitate in midair, and the Vive’s position tracking cameras allow digital artists to move through the canvas while painting with beams of light in every direction around them. Praise for Tilt Brush has been widespread and feverish. Recently, Fast Company called it “the first great VR app,” seeing it as the perfect introduction to this new world of possibilities. Skillman agrees.“The stars have aligned and VR is finally coming into its own,” he said.

Creativity Begets Creativity

Skillman’s emphasis on fate is apt given the ideation of Tilt Brush happened almost by accident. In 2012, Skillman and Hackett were both employed at Double Fine Productions, the game studio helmed by renowned point-and-click adventure designer Tim Schafer. They were fascinated by the latest gaming gadgets, so they banded together under the sarcastic title Department of Future Tech in order to spend 10 percent of their time on wild experiments. Experiments in the Department of Future Tech included duct-taping Razer Hydra motion controllers to their foreheads to enable mobile games to track their body positions. When Skillman and Hackett decided to combine an Oculus VR headset with the Kinect’s motion-sensing camera on a whim, they were amazed by the results.

VR has the potential to be the most intuitive and natural creation platform artists have ever experienced

“It was a window into what was really going to happen [in] the next five to eight years,” said Hackett. Having seen a glimpse of the future, the two resigned from Double Fine and formed their own company. Among other things, their focus was on developing technology that could give VR users a sense of having a body inside a virtual simulation. “We really stumbled into VR painting by accident through our work on different VR and augmented reality interactions,” said Skillman. “While debugging a prototype, [we] started drawing lines in space. We were mesmerized instantly.”

Skillman and his partner weren’t the only ones who were mesmerized, either. Since Tilt Brush’s inception, a flurry of leading cartoonists and animators have rallied behind the technology’s almost magical concept. Among them are Glen Keane, best known for his animation work on Disney’s The Little Mermaid (1989) and Aladdin (1992), and Chris Prynoski of Adult Swim fame. Many big-name artists have already produced a tremendous number of painterly compositions in VR, inspiring Tilt Brush’s creators and amateurs alike.“It’s amazing to work alongside these artists and watch their VR paintings grow and mature as Tilt Brush evolves,” said Skillman. “In many ways, we feed off of each other’s creative energy.”

Out with the Old…

Skillman believes this technology is the tip of the virtual iceberg. “With Tilt Brush, we’re doing our best to throw out the old ‘keyboard and mouse’ paradigms that we’ve all grown accustomed to, but we’re still in the early stages of that transition.” While it may be strange to think of standard computer equipment as old fashioned, according to leading technological innovators, VR has big implications for the type of digital creations people will be making in the future.

“Tools like Maya [the 3D computer graphics software] have been highly tuned and optimized for doing modeling and creation on the PC for many, many years,” said Ebbe Altberg, CEO of Linden Lab, creators of the virtual world Second Life (2003). “It will take a while for VR to [do similar things] effectively.” Before the artistic singularity can happen, the tools to create these wonderful worlds will need to develop more. “But VR is extremely powerful because you have a complete sense of space and scale that you do not have looking at the PC,” Altberg added. Despite the room for improvement, companies are already bringing new artist-driven technologies to market. Planned to launch in the latter half of 2016, Linden Lab’s next virtual world, codenamed Project Sansar, will put a big emphasis on creating inside VR. With a sweep of their hand, users will be able to redesign their virtual home or toss boulders around on Mars, Altberg said.

VR has big implications for the type of digital creations people will be making in the future

Elsewhere, the VR building game Fantastic Contraption allows players to pull tools out of shortcuts on their body. To assemble a simple machine in the game, for instance, a user might grab a rod from over their shoulder, two wheels off the side of their hip, then snap them all together. Similarly, the next version of the game-making tool Unreal Engine 4 allows VR creators to fashion worlds with a pair of lightsaber-esque utensils. While tools such as these will enable a vast array of artistic expression to exist within VR, the art is not necessarily confined to imaginary places. Altberg hints at a porous boundary between the real and virtual, where makers can send their creations back and forth across the digital divide. Altberg foresees fashion brands jumping on the VR bandwagon, as well as other physical and virtual world crossover projects. “Our belief is that VR will ultimately impact pretty much everything,” he said.

The post How VR will change the way we create appeared first on Kill Screen.

Go on a beautiful voyage into the unknown with Verreciel

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

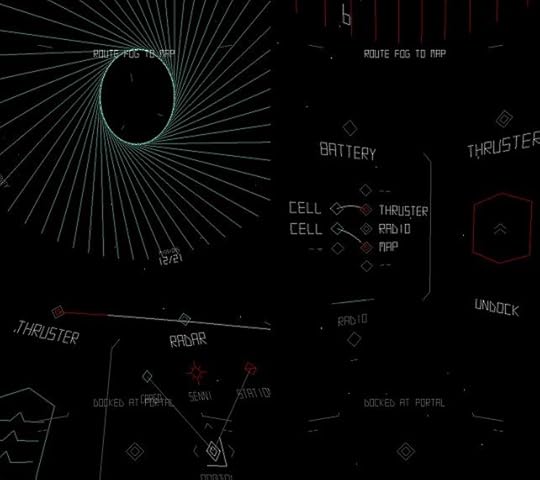

Verreciel (iOS)

BY DEVINE LU LINVEGA

Verreciel is the latest entry in Devine Lu Linvega’s “sequence of linguistically involved projects,” which includes Paradise (2011), Hiversaires (2013), and Oquonie (2014). Verreciel has you explore various star systems by connecting the consoles that surround you inside your Glass Ship. As you navigate outer space, you follow simple missions: harvesting currencies and trading them for warp keys to new locations. It’s a game about mastering the mechanical intricacies of travel, which echoes Linvega’s latest life choice to live on a boat and sail the world. Linvega’s hope is that his aquatic adventures will lead to new inspiration. This, too, is reflected in Verreciel, through the beauty of its space stations and cities you visit, all depicted in abstract geometric shapes while hypnotic music plays on your radio.

Perfect for: Space traders, cosmonauts, linguaphiles

Playtime: 2-5 hours

The post Go on a beautiful voyage into the unknown with Verreciel appeared first on Kill Screen.

The inglorious nihilism of Grand Theft Auto V

Grand Theft Auto V (2013) is a confidence trick; Rockstar is a fraud. They tell people to distrust capitalism and suspect politics—the entire world, and all its peoples, are venal. In the same breath, they promise sanctuary. “Are you young? Are you angry? Are you an iconoclast, too? Then Rockstar and Grand Theft Auto are here for you,” they seem to say. But it’s a con. Rockstar embraces cynics and outsiders, but only so it may reach a hand into their pockets.

Generally, Grand Theft Auto is nihilistic, in a manner betokening not worldliness but arrogance. The chief villain of Grand Theft Auto V is Devin Weston, a billionaire whose wealth and power are used as weapons against the protagonists. “I’m rich enough to do whatever the fuck I like,” says Weston “and you’re poor enough not to ask me any goddamn stupid questions.” Corporations are evil in Grand Theft Auto V: LifeInvader, a social networking site and parody of Facebook, even the name of which marks Rockstar’s opinion on technology firms, carries the slogan “it’s not just technology. It’s your life,” and instead of a “Like” button encourages users to “Stalk” one another. And Michael De Santa, one of the three playable characters, is leading a life surreptitiously destroyed by money—his kids are spoiled, his wife is shallow and he is unfulfilled. In Grand Theft Auto V, wealth and success are uniformly corruptive. Yet, just days after the game’s launch, Rockstar’s owner Take-Two Interactive issued a press release, boasting that Grand Theft Auto V had already made $1 billion. In 2012, Grand Theft Auto co-creator and Grand Theft Auto V lead designer Dan Houser purchased a flat in New York City for $12.5 million. And of course, Rockstar has its own Facebook page, through which Grand Theft Auto V is advertised and sold.

In Grand Theft Auto V, wealth and success are uniformly corruptive

Aside from my personal dismay that a game as miserable as Grand Theft Auto V can earn so much money, and that its creators can earn such luxury off the back of it, none of these stories are particularly assailable. But patently, Grand Theft Auto V is immensely insincere and hypocritical. I don’t for a moment believe that either Rockstar or Take-Two, both of which earn substantial profit, the latter of which enjoys great success on the NASDAQ, are seriously critical of corporate structure, nor do I concede that Dan Houser, a multimillionaire, is in a position to pen even-handed criticism of the rich and famous. The success of Grand Theft Auto and its creators is legitimate. Its political conscience and artistic aspiration are not—under the rubrics of rightful protest and uncensorable indignation, it plies its audience with counterfeit “truth.”

And even if the makers of GTA V truly believe in what their game says, they are spiteful, vapid writers. Grand Theft Auto was once being made by a plucky, young studio from Scotland called DMA Design. Back then, the games’ nihilistic shouting—its punching up, down, and across—felt justified. Punk was dead. So was Gen X. And with the launch of the first PlayStation, videogames were becoming more corporate than ever. A tiny British developer, slinging controversy for cash, wasn’t just cool, it was right on. By October 2001, almost a year into the Bush presidency, five years into Tony Blair’s Centrist government and amid a groundswell of Neo-Conservatism, following 9/11, Grand Theft Auto‘s disaffected charm was at its most powerful—when GTA III (2001) said “fuck the world,” it felt like an important message.

Grand Theft Auto‘s success shouldn’t be begrudged. A successful product earns its creator a lot of money, and in turn the creator becomes a bigger, richer company. That’s a dynamic as old as money itself, of which Grand Theft Auto is merely an affirmative example. What I deplore is Grand Theft Auto‘s lack of internal inquiry, its political and social positions which, despite the passage of almost 20 years, and the total redefining of its status within gaming culture and culture-at-large, have remained unchanged. When Grand Theft Auto was an underdog, its disregard for taste—its chew-and-spit treatment of the rich, the poor; women, gay people and people of color—felt like genuine anger, like rebelliousness, without cause. Amid other 90s iconoclasm (the early series of South Park, films by Kevin Smith and David Fincher, games like Postal, Conker, Crazy Taxi) Grand Theft Auto once fit. Even the most easily offended would have conceded it was timely.

But today, with Grand Theft Auto V, we have multi-millionaires, who from the comfort of their offices on Broadway in New York City, make jokes about poor, black Angelenos. Women are still the butt of Rockstar’s wisecracks, as are gay people, people of color, and the poor. Celebrities, white guys, and the rich and famous get thrown under the bus as well, and some might be tempted to use that in Rockstar’s defence—the studio goes after everyone, that’s just its style. But where those rich, white people, most probably men, benefit from Grand Theft Auto‘s success, inasmuch as its profits are returned to an industry dominated by people like them, other targets of the game’s so-called satire simply receive yet more discrimination. Grand Theft Auto and Rockstar have both become that which they mock—their self effacement, however, is sold at a premium.

Grand Theft Auto and Rockstar have both become that which they mock

Not that Grand Theft Auto V can truly be called self effacing. When it mocks peoples, American culture and other videogames, Grand Theft Auto V is not cautioning against the system. It is telling its players to trust in something: Grand Theft Auto itself. Like the preacher who castigates other faiths in defence of his own, Grand Theft Auto perpetuates its own sovereignty. The game is not nihilistic. It is theocratic. Any beliefs that one might hold, in politics, in media, in concomitant social responsibility, are denounced. In cynicism and misanthropy Grand Theft Auto players are encouraged to trust. And like a Virginian evangelist, hawking his lies over daytime television, Rockstar grows fat off its toxic gospel.

This, from what is supposed to be gaming’s greatest success. This, from what is often called the medium’s most biting satire. This, from a game that for many millions is the flag bearer for an entire culture. If gaming is to be the prominent art form, or even entertainment form of the 21st century, it surely has to become better than Grand Theft Auto V. Psychologists don’t listen, wives cheat on you, politicians are corrupt—these sentiments, and more, are absolutely adolescent, and yet Grand Theft Auto is talked about as if it’s on the cutting edge. Grand Theft Auto V is not just a bit of fun. It is not a game that shouldn’t be taken seriously. Regardless of how well designed or deliberately absurd its core mechanics may be, they are impossible to enjoy when surrounded by such odious and rankly hypocritical literature. When hundreds of millions of dollars, innumerable hours of labour, and barrels of ink are spent on a game so utterly bankrupt, it is not to be accepted blithely—it is the example of this fledgling art form, once again, misusing its capital at its own peril.

The post The inglorious nihilism of Grand Theft Auto V appeared first on Kill Screen.

May 18, 2016

Inside the Kubrickian spaces of Twelve Minutes

Visual artist Luis Antonio’s been around. He used to work at a couple big name game companies (Rockstar and Ubisoft). But, feeling unfulfilled, he jumped ship to work on Jonathan Blow’s The Witness, a game that incidentally inspired him to learn programming and pursue his own personal project, Twelve Minutes. Twelve Minutes has been in development for around three years, but until now, was merely a passion project, a side activity. But now, that’s all changed: as Antonio’s announced that development of Twelve Minutes has achieved funding, and has become a full-time project.

(A screenshot from the Twelve Minutes prototype)

Twelve Minutes is a top-down adventure game, experimenting with the unwieldy world of time loops. Think Groundhog Day (1993) but with more Stanley Kubrick in the mix. The entire game takes place within a minuscule apartment, as a man relives the same 12 minutes of an evening with his wife, disrupted by a cop barging in and beating them up. Using your knowledge of the situation, you seek to break the time loop and prevent that from happening. “The game doesn’t tell you what to do. It doesn’t tell you what is right or wrong,” Antonio told us at the Game Developer’s Conference this past March. “It’s a lot about discovery, and how you use your knowledge of your given situation and how to use that knowledge to achieve certain outcomes.”

“The game doesn’t tell you what is right or wrong”

The apartment environment is central to Twelve Minutes. The entire game takes place in the small rectangular shaped room, and all the actions, all the characters, everything resides within it. Antonio took inspiration from another notable location: the ominous hotel from The Shining (1980). In Stanley Kubrick’s classic horror, the environment has a life of its own, yet it’s “dream-like and comfortable.” In Twelve Minutes, the apartment is mundane, but with its time-leaping twist, grows more and more unsettling with each rewind. “The goal is to create a ‘lived in’ place, with story, personality and intimacy,” writes Antonio on his recent blog post celebrating the positive news.

In conceptualizing Twelve Minutes, Antonio sought help from sculptor Andrea Blasich (who also lent a helping hand to The Witness). “I wanted to try a different approach for character design,” writes Antonio of the unique project. “Rather than starting with concept art, why not do the exploration in 3D?” Blasich’s sculpture concept is palpably human, but not in a photo-realistic sense—which is exactly what Antonio hopes to be conveyed in the final game.

With funding now in place, Antonio’s goal is to polish the prototype into a fully-fledged game. That means focusing on further developing the animation, writing, character design, and even hiring other people to work on the project. “I want the characters to express their emotions through the ways they move and behave,” writes Antonio in the blog post. “With believable dialogue that doesn’t just read like an exposition dump, but actually expands on the game’s dramatic narrative and reveals each character’s nuanced personality.”

Follow Antonio’s devlog for more updates on Twelve Minutes, with a hopeful release in Q1 of 2017. Reporting contributed by Roy Graham.

Header image: New concept art for the full version of Twelve Minutes.

The post Inside the Kubrickian spaces of Twelve Minutes appeared first on Kill Screen.

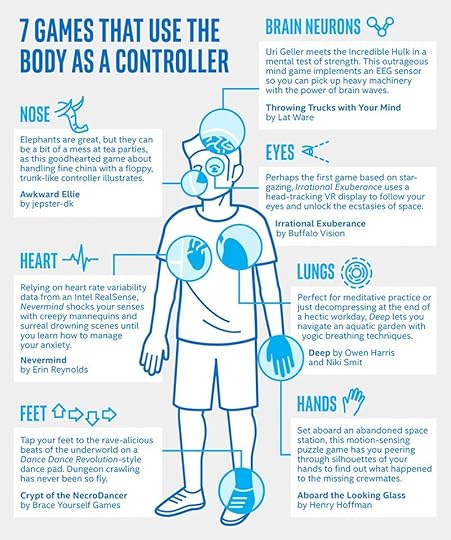

Alternative gaming controllers facilitate full-body fun

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

While videogames have inspired a staccato of button-tapping throughout their brief but effusive history, the majority of games makes use of few motions other than a twitching of hands and fingers. There are notable exceptions, such as poking tennis balls with the Wii Remote or waving at the Xbox Kinect, but the 900 other ligaments of human physiology get markedly less play. With the new generation of alternative gaming controllers, however, the days of button-mashing may not be long for this world. These recent and fascinating alternatives give traditional controls a run for their money. Now more than ever, developers and designers are forging out funky, engaging and high-tech games that explore the entire body’s untapped potential for full-bodied fun.

In Homies (My Homunculi), a feral and funny game by the installation creator and interactive design instructor Sam Sheffield, the player straps into a pop-art inspired robot mask for a disorienting round of Simon Says. The voice of an imperious butler commands players to stick their fingers in places that they probably shouldn’t, like up the robot’s nose or in its ear holes. “The eyes are on springs so you have to chase them around,” Sheffield said, explaining that all this is simply more challenging than it sounds because you can’t see what you are doing with the mask on. “The idea is to give people permission to re-explore the geography of their faces,” he said.

Homies drew plenty of chortles and strange glances when it debuted alongside other experimental control interfaces during the ALT.CTRL.GDC exhibit at Game Developers Conference 2015, and for good reason. In the second level of the game, the player dons a wolf mask. Tilting her head in the direction of the (on-screen) moon, the player is instructed to let out a big howl. A third level would have naturally incorporated a “Creature from the Black Lagoon” style mask, but Sheffield scrapped the idea when he couldn’t come up with a gesture that felt right for the gilled monster.

Sheffield isn’t the only one experimenting with full-bodied gaming experiences. There’s a growing pool of game designers who are putting their heads together to think outside the gamepad’s hard plastic casing. Of course, they couldn’t do it if the technology wasn’t there. Egged on by the maturation of alternative inputs like Intel RealSense 3D camera technology, an increasing amount of tools exist to unleash their creativity. “If you ever played with the first incarnations of [motion control cameras], it was like playing stickman,” said Eric Mantion, Developer Evangelist at Intel. “What we’re accomplishing now with RealSense technology is a much finer granularity. It’s like giving a computer human depth perception so it can read face and hand gestures.”

putting their heads together to think outside the gamepad’s hard plastic casing

This is exciting in and of itself. Rethinking something as basic and essential as controls often results in all kinds of new and innovating modes of play. This year’s ALT.CTRL.GDC exhibit, for instance, will include wondrous curiosities such as Palimpseste, an almost kaleidoscopic first-person exploration game that lets you use a pair of goggles to cycle through red, blue and green color filters and discover unseen secrets in the game-world. In Awkward Ellie, players don trunks to simulate a clumsy elephant who isn’t exactly making friends at the fine china store. Elsewhere, the IndieCade finalist Maze of Heart uses a next-gen motion-sensing camera to turn the user’s entire body into a kind of mechanical puzzle box. Players must reassemble pieces of their broken hearts, shaking them free from their upper and lower extremities so that the pieces combine in their chest area.

The game design technology is decidedly futuristic, but there’s a getting-back-to-nature element to these advancements. “What’s interesting about a lot of the newer immersive 3D technologies is how they allow us to reconnect with the kind of gestures that games have let go to the wayside,” Sheffield said. “There is an incredible vocabulary of gestures that are practical and expressive, but we use almost none of them while playing digital games. These kind of technologies are opening it up.”

In addition to creating fertile grounds for the ideation of fun, intuitive technologies are opening their arms to people who might otherwise be turned off by the complexity of the traditional gamepad and the two-fisted, claw-like grip necessary to use it. The new wave of full-body games “are about doing micro-gestures — things that your hands and fingers are designed to do,” said Sheffield. By stepping away from standard controls and button-mashing to design games for the body, the medium will be all the more approachable and human-centric.

The post Alternative gaming controllers facilitate full-body fun appeared first on Kill Screen.

Ubisoft designer captures the mystique of Tokyo at night

Liam Wong, Ubisoft’s graphic design director, takes dope photographs. Perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise. The obvious temptation with Wong’s photography, which is posted on Instagram and sold on Society 6, is to liken it to his work in videogames. Insofar as games are our main point of reference when thinking about Wong’s aesthetic choices, this temptation is understandable. Yet doing so deprives the viewer of the opportunity to think about Wong’s photography on its own terms.

A video posted by LIAM WONG ✖ リアム・ウォン (@liamwon9) on Apr 4, 2016 at 4:06pm PDT

Wong’s photographs depict the real world—Tokyo, to be precise. It doesn’t always look as such, but that’s because of specific stylistic decisions. The photographer plays up aquamarine and pink shades in signage and lighting until they appear otherworldly. Backgrounds blend into panels of overexposed lights. But this is just our world, as seen with a different emphasis.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers