Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 117

May 23, 2016

Shadwen is a stealth game trapped in adolescence

Playing a stealth game is like dancing. Or, more accurately, it’s like the evolution of how you approach dancing over the course of your life. Starting out, you’re a junior high pubescent: every move is a little awkward and the rules of appropriate conduct somehow seem both unclear and inviolate. You accidentally put your body in the wrong place and a whole goddamn army of humiliation descends upon you. Then the game progresses, and you’re in high school: you’re starting to get the hang of things, in terms of physically navigating the environment but also in appreciating that while there are indeed hard-and-fast rules, there is also room for you to express yourself and approach the task at hand in a creative, idiosyncratic fashion.

Finally you’re a grown-ass adult, drunk at a friend’s wedding: the stakes are high, you’re brimming with confidence, and you want to show off what you can do. If you pull this off, you’re the life of the party. If you make a fool of yourself, then the newlywed couple and their respective families will roll their eyes every time they think of you for the rest of their lives. This progression is essential to a genre defined by avoiding being noticed through the performance of increasingly audacious acts in the shadows. If a stealth game is excessively punitive in how it manages its hiding mechanics, it can keep you trapped in middle school; you’re eternally embarrassed by hypervigilant chaperones, shouting out things like, “How the hell did that guard see me through the wall?”, before throwing the controller down in a rage. A crime of equal measure is allowing you to become complacent in your adroitness. Feeling like a ninja master in a game that does not scale itself up to match your skills is like being Matthew McConaughey’s character in Dazed and Confused (1993): a dude who was cool in high school and keeps hanging around because it’s easier than facing the real world. This is the mistake made by Shadwen, a stealth game with some interesting ideas that never quite makes the transition into adulthood.

The titular Shadwen is an assassin en route to kill the king. She comes across Lily, an orphan girl with nowhere in particular to go, and so, improbably, they decide to travel together. Shadwen has a grappling hook that allows her to access high places and yank objects from afar, and through the art of misdirecting patrolling guards she must clear a path for Lily as the two of them traverse a medieval city on their way to complete Shadwen’s dark business. Three important rules define how you navigate the levels of Shadwen. First, whenever you are not moving or taking some action, time stops. Whether you are at rest, mid-sneak, or mid-jump, the default state of the game is one of suspended animation in which you can move the camera around to scope out what’s what. This naturally slow pace is important because of the second rule, which is that if Shadwen is spotted, it is an instant Game Over. There is no health bar, no opportunity to escape and re-hide after being seen. This is not as brutal as it sounds, however, thanks to rule three: at any point you may rewind time, going as far back as the start of the level.

By giving you the ability to undo the junior high gaffes of missing a jump or hitting the wrong button, Shadwen eliminates the learning curve of a stealth title like Metal Gear Solid V (2015), which forces you to adapt to mistakes on the fly or else face having to restart an entire section of the game. The ability to reverse any misstep however small or large lends a tremendous amount of control, especially for a genre marked by being outnumbered and outgunned. The expected compensation would be for Shadwen to demand intense precision: if you can stop and rewind time, you better do it right. Unfortunately, Shadwen is not especially precise. A similar time-stopping mechanic felt essential in SUPERHOT, in which each footstep required consideration in order to weave through speeding bullets in balletic majesty. But the goofy guards and ample hiding places of Shadwen offer lots of room for error—even as the game allows you, if you want, to eradicate all error. But there’s no real reason to bother.

if you can stop and rewind time, you better do it right

The game never deviates from its initial configuration; though you grow faster and bolder, Shadwen neglects to throw any curveballs to challenge you. The boilerplate medieval world is only populated by two guard types (normal and armored), who are as clever in level one as level 15. The game is almost aggressive in its refusal to mature alongside you, even when such arrested development starts to appear absurd. The two designated hiding places for you and Lily are haystacks and shrubs, which make sense early on when you are on the outskirts of town, but less so when they continue to appear in abundance within the king’s high castle. Guards are often overhead speaking of their belief in “dark spirits,” an apparently universal superstition that explains why they are never unduly suspicious when a crate starts moving of its own volition (rather than taking the extra moment to realize that, in fact, it is attached to your grappling hook).

Lily, for her part, cannot do much, though she does have a preternatural sense of where guards are and in what direction they are facing. Whenever she has the opportunity to progress she does so autonomously, and though you have the ability to call her to your position (through some unexplained telepathy, as this is done silently and does not require line-of-sight), it is rarely needed. Again, the game opts to empower you by providing an intelligent and self-sufficient companion, but then fails to introduce new elements from level to level that might make the proceedings more interesting. For every time I got angry with Lily for not seizing the opportunity I created to slink from point A to point B, there were 10 instances in which she seemed to play the game wholly on her own, detecting the natural blind spots in guard patrol patterns and sneaking her way forward without my help.

Lily’s most important role is that of innocent spectator. Most stealth games pose the question of whether to kill or not to kill, with the implicit understanding that killing is easier; it permanently removes an enemy from the equation, and so going for a “no kill” playthrough is typically regarded as more challenging and requiring greater skill. Shadwen adds another layer to this: if Lily sees you murder someone, or indeed comes across a body at all, she is labeled as “horrified,” and the game invites you to rewind if you so choose. While doing so only seems to affect Shadwen’s brief and emotionally tepid ending, it is nevertheless an intriguing take on the “no kill” mentality, in which shielding a child from your heinous acts is equated with not committing them at all.

Lily’s most important role is that of innocent spectator

A stealth game that gives you the tools to be perfect is an exciting proposition—but only if it demands perfection in return, which is why Shadwen left me tantalized. There are a litany of issues that keep it from realizing its potential, from the game’s odd physics (a barrel can be swung around as though made of paper, but if it makes the slightest contact with a guard, it will kill him) and wonky AI, to the fundamental strangeness of your ability to manipulate time in the first place—a mechanic which has been satisfactorily explained by magic in Prince of Persia: Sands of Time (2003), or poetical metaphor in Braid (2008), but is offered sans logic here. With more time to flesh out the world and, most importantly, a more creative progression of challenges to match your skill, this could have been a special game. Instead, just as its titular character is trapped in time by default, Shadwen is a stealth game forever trapped in a state of adolescence.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Shadwen is a stealth game trapped in adolescence appeared first on Kill Screen.

May 21, 2016

Weekend Reading: In Cyberspace Everyone Can Hear You Shred

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Virtual Reality Owes a Lot to the Air Guitar, Meghan Neal, Motherboard

Some think virtual reality was created for games. That certainly was the attitude when Oculus launched their Kickstarter campaign. Others think it’s for film, and many more imagine it as a way to enter a new dimension. Jaron Lanier, a Silicon Valley veteran who is considered to have coined the term, says virtual reality was created for a real curve ball: air guitar. As Lanier prepares a keynote for this year’s Moogfest, Neal speaks with him about music’s VR potential.

The Coming Horror of Virtual Reality, Simon Parkin, The New Yorker

Videogame fans certainly enjoy getting spooked, and the revival of shock-riddled projects seems to be on a collision course with virtual reality. But aside from the obvious guttural intimidation, what makes fear in these devices so much more intense? Simon Parkin looks at the past, present, and future of getting the willies.

Shuffleboard At McMurdo, Maciej Cegłowski, Idle Words

McMurdo Station is the southernmost American settlement; a polar outpost for scientists and passerby. But as you may be wondering, and as Maciej Ceglowski clearly wondered, what the hell do people do all day down there? A surreal and sleepy place, Ceglowski speaks with locals at living on the edge of the world, and asks why they’re obsessed with Zippo lighters.

The post Weekend Reading: In Cyberspace Everyone Can Hear You Shred appeared first on Kill Screen.

May 20, 2016

Katamari Damacy gets rolled up into a text adventure

Game designer Keita Takahashi’s Katamari Damacy (2004) is easily one of the most charming videogames of all-time. It had a silly premise, a colorful aesthetic, and a grin-inducing soundtrack. Katamari Damacy was like no other game in existence. An underrated aspect of it, though, is its whip-smart writing.

From the bizarre story of the King of All Cosmos knocking out all of the stars in the sky after a drunken binge, to the descriptions of all the mundane items the Prince’s magical ball rolls up on Earth, Katamari Damacy’s quirky writing embellished everything else that made the game so notable. For the San Francisco Stupid Hackathon, one code-savvy man decided to de-make the game into a text adventure, eliminating virtually everything else pleasant about Katamari — leaving just its writing.

Noah Swartz, creator of Katamari Adventure, is a staff technologist for the Electronic Frontier Foundation. And in his spare time, a prolific github-er. He was inspired for this zany Stupid Hackathon project by an old post buried in the most arbitrary of places: a 2005 blog post from a Katamari Damacy LiveJournal fan community. The original blog post’s text-adventure take on the game is tongue-in-cheek. Much like an old text adventure, full phrases are necessary in order for the Katamari to roll over it (such as “paper clip” instead of “clip”). And in the end, the King of All Cosmos is still unsatisfied, and you’re doomed with a low score.

Katamari Adventure eliminates virtually everything else pleasant about Katamari

Swartz’s fully-fledged text adventure adaptation is more rounded than its LiveJournal-bound predecessor. The game has two playable levels (a test level and the primary “starter_house”). Dozens of items can be rolled into your text-driven Katamari ball: erasers, screws, mahjong tiles, and frogs galore. The item descriptions lift directly from the game it was inspired by, such as a banana described as, “You don’t need to be a monkey to eat this” or an ominous red crayon’s warning, “This is not lipstick. Girls, be careful.”

The “Stupid Shit That No One Needs And Terrible Ideas” Hackathon (shortened to Stupid Hackathon) has long birthed tremendously idiotic tech projects, a text-based Katamari Damacy game is probably one of the least stupid of them all. The dumb-minded hackathon began in New York, and has since spawned in San Francisco, Toronto, and even Berlin.

You can download and play Swartz’s Katamari Adventure here, off his github .

The post Katamari Damacy gets rolled up into a text adventure appeared first on Kill Screen.

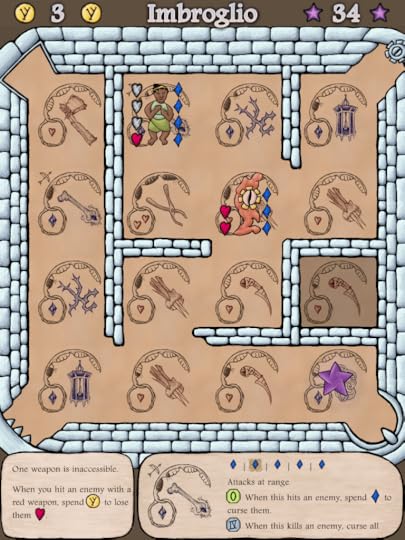

Michael Brough has another tricky labyrinth for you to survive

Michael Brough excels at designing systems that are simpler than they sound—better understood through exploration than explanation—and his grid-based games keep getting smaller and more complicated. In Imbroglio, his latest, your little dungeon-crawler has two health counters in the form of hearts and diamonds. Hearts are damaged by red monsters, diamonds by the blue ones, and you can do damage to their hearts or diamonds if you’re standing on a red or blue weapon tile respectively.

In some of Brough’s previous work—like 868-HACK (2013) or Zaga-33 (2012)—you gain abilities by collecting them during play, but in Imbroglio, they all start out right there on the board. Killing an enemy while standing on a tile feeds that tile—four kills levels it up and nets a rune you can use for your hero’s special ability. After a few games, you can unlock the ability to rearrange the tiles to your liking. Brough has described this element of the game as “deck-building,” but it feels less random than waiting for a particular card to pop up out of your Netrunner (2012) deck.

chaining together moves feels like building a soundtrack

Instead, you spend time drawing monsters into corners and taking a couple points of damage to put them right where you want them. You advance the game by collecting gems, which reset the maze and give you one of each kind of health, so instead of running around trying desperately to not get hit, you’re getting hit on just the right move, leveling up the shield so you can increase your maximum health anyway.

One tile feeds every surrounding tile when it levels up, another starts out incredibly strong and loses damage as you use it. Another lets you respawn. Like a deck-builder, you start with the perfect synergistic plan and end up flying by the seat of your pants, hoping you can level up and use a stun at a life-saving moment.

I sort of miss the garish pixels and mouthy sound effects of Brough’s glitchier-looking titles, but the sound design in Imbroglio is as generative and weird as the rest of it: each action—an attack, the appearance of a new monster—is punctuated by the scratchy and very physical sounds of an acoustic guitar. It’s not complex, but playing and chaining together moves feels like building a soundtrack suited to your own bizarre quest.

I’m still trying to unlock a few characters (the last one requires you to unlock a whopping 128 gems with four of the other heroes) but if if it’s anything like Brough’s other games, I look forward to something that completely inverts most of what I’ve learned so far. While it’s much more intricate, Imbroglio is also one of the least obtuse games Brough has released, and I’m stoked to swap strats with anyone I can convince to give it a try.

Imbroglio is available to purchase on the App Store.

The post Michael Brough has another tricky labyrinth for you to survive appeared first on Kill Screen.

New thermoforming technique offers a faster alternative to 3D printing

With the advent of 3D printing, it’s easy to imagine a future where industry is as simple as pressing a few buttons on a computer screen. Just take any computer-generated 3D model, send it to a 3D printer, and within a few minutes to a few hours, you’ll have an actual, physical object that you can hold in your hand.

The problem, then, is the wait. Whereas a three hour wait for a small statue might be bearable for individual use, large-scale production houses may not be able to afford the lost time when compared to more traditional methods. To avoid this, Zurich’s Interactive Geometry Lab has recently developed a more instant alternative: simply create a single mold and then use a process called “computational thermoforming” to bring computer-generated models to life within seconds.

Currently, thermoforming is widely used by the shipping industry to create simple plastic containers, boxes, and packaging material. It involves using a heat-resistant material such as aluminum or gypsum to create a mold for the end product’s desired shape, then heating up a flat plastic sheet to near its melting point, at which point a vacuum pulls the sheet over the mold. The plastic sheet then instantly and permanently takes on the shape of the mold, and the mold itself can then be used again to mass produce copies. With computational thermoforming, the Interactive Geometry Lab hopes to use an algorithm to print distorted 2D representations of 3D models onto these flat plastic sheets, which will then take on the appearance of the model they were based on during the process.

rising out of some primordial ooze

While creating the mold takes time, the instantaneousness shaping process resembles something out of Harry Potter. In the few seconds it takes for the mold to be punched through the plastic sheet and for the vacuum to kick in, it looks as if the end product is being conjured from nothingness, like it were rising out of some primordial ooze. Unlike regular thermoforming, the Lab’s creations are fully colored and textured, allowing them to easily create masks, food replicas, toy car parts, and props for model scenery within seconds. As opposed to 3D printing, the process can then be repeated much more quickly by using the same mold to create multiple copies.

As of now, computational thermoforming is limited to plastics as well as to hollow objects, but the Lab does note that it offers more vivid colors than 3D printing. It is also built with low-cost, off-the-shelf products, meaning that it may offer a cheaper and quicker alternative for hobbyists and entrepreneurs looking to take their production into the future.

The post New thermoforming technique offers a faster alternative to 3D printing appeared first on Kill Screen.

Artist gives brutalist architecture a singing voice

Brutalist architecture has gotten a bad rap over the years—so much so that Goldfinger, the villain of James Bond fame, was named after Ernő Goldfinger, an architect inspired by brutalism. Mo H. Zareei (aka mHz) is trying to fight back against this societal repulsion with his evocative sound sculptures. He’s an Iranian electronic musician, sound artist, and music technology researcher, who is actively finding ways to use his interests in both brutalist architecture and noise to show how nuanced and poetic these two concepts can really be.

In his series machine brut(e), Zareei makes use of three sound sculptures rasper, Mutor and rippler, to make unusual audiovisual combinations. Each piece is a marriage between sound art and sculptural composition, accompanied by a concrete block to visually highlight the ‘raw concrete’ material and its links to brutalism. Zareei breaks down the different elements of brualist aesthetics which are compelling to him, as he says, “The monolithic appearance, visibility of material, valuation of crude concrete, strict geometries, repetitive modules, lack of nonfunctional ornamentation, these were all fundamental principles by which I have constructed my sound-sculptures.”

Each piece is a marriage between sound art and sculptural composition

Zareei describes his childhood in Ekbatan, Tehran to Streaming Museum as growing up among “gray Lego-like giants,” and speaks of the town and “the poetry of its parallel lines and right angles, its strict geometries, homogeneous grayness, and the perfection of its zigzag… a gracious haven of order and coherence in an enormous city of haphazardness.” This background giving brutalist architecture an almost romantic sense undoubtedly affects Zareei’s work, and allows him to express a perspective deeply contrasted to Ian Fleming’s villainous portrayal, or the perceived mundanity and ugliness of the style.

Although the sound sculptures of this project may initially seem dull and monotonous, or even ugly and abrasive, if experienced in an open-minded and curious way, they can be incredibly and unexpectedly satisfying and poetic. Listening and watching Composition 0001 reminded me of tile floors and concrete, a turnstile moving with perfect flow. It also reminded me of oddly satisfying industrial processes (try to watch this muted, with Zareei’s work below, playing in the background to get a sense of what I mean). As highlighted by The Creators Project, “Zareei’s goal with the constant repetition is to create a “temporal monolithism” that matches brutalism’s block-like aesthetics. The repetition is also designed to produce an ‘instant audible structure’.”

Zareei, speaking about the types of works that inspire him says: “it seems clear to me that the works of sound art and music that I am influenced by… can be summed up as the sensory experience of the conventionally non-interesting on a highly ordered and sensually accessible structure.” This idea of the conventionally ‘non-interesting’ being sensually accessible, strongly comes through in his work, which will likely evoke a sensory reaction in all its viewers, in one way or another.

Mo H. Zareei is currently living in New Zealand, where he is pursuing his PhD research on noise music and mechatronics at Victoria University of Wellington. You can keep track of his work through his website and Facebook page

The post Artist gives brutalist architecture a singing voice appeared first on Kill Screen.

Teen Patti and The Rise Of Mobile Gaming in India

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

You can play Teen Patti just about anywhere these days. A half-sister to Texas Hold’em, Teen Patti games were once mostly contained to the felt tables of Indian casinos. All that’s changing. With the use of smartphones soaring in the country, mobile games are becoming accessible to millions for the first time.

In 2014, smartphone use in India more than doubled. Experts are also projecting the number of smartphone owners in India to surpass the US as soon as next year, with 219 million smartphone owners in the country. The advent of low-cost smartphone alternatives like The Freedom 251 (with a price tag of 500 rupees) is also priming India to become the next mobile market powerhouse. “Data is becoming better, more cell phones are coming in, and the technology is becoming better,” says Akshat Rathee of Indian game promoter, NODWIN Gaming. “There are more people [playing] games on cellphones.”

Although the country’s fledgling gaming community has only just begun to spread its wings, it appears new mobile titles can’t come fast enough. According to Anila Andrade, Assistant Vice President at 99Games and the lady behind hit game Star Chef, “48% of app usage time on mobile phones is [spent] on gaming.” So although the majority of Indians may not consider themselves traditional gamers, the country appears to be warming up to accessible titles quickly. As a result, India now houses a number of local mobile development studios creating distinctly Indian titles. In general, most games made in India gravitate towards “the ‘ABCD of Indians’—Astrology, Bollywood, Cricket and Dance,” according to Andrade.

Until recently, almost all of the mobile games played by Indians had originated from studios outside the country. As with the rest of the world, games like Clash of Clans, Candy Crush Saga,and Clash of Kings dominated Indian charts. But local talent is slowly changing that. According to Andrade, more and more Indian-made games are populating the top-earning mobile game lists in the country. Local game producers are tapping into Indian culture for inspiration. Teen Patti, for instance, had their players splash each other with brightly colored dyes during Holi, or the Festival of Colours, which is usually celebrated in spring. Diwali, the Festival of Lights, also received a similar treatment focusing on its iconic diyas. Bollywood, meanwhile, is also finding its way into the gaming scene.

Local game producers are tapping into Indian culture for inspiration

99Games has launched a first attempt to court the motherland by partnering with a Bollywood production house. The result was a racing game based on the motorcycle chases in Bollywood action flick Dhoom: 3. The response was beyond their loftiest expectations. “We got 20 million downloads from within India,” she said. “We realized India was a massive market and we needed to target this space.” The thriving market is already drawing the attention of some of the world’s biggest leaders in technology.

Tim Cook heaped praise on India’s smartphone surge, labeling the growth of mobile in the country one of Apple’s most important opportunities at the conclusion of a company-wide Town Hall. In February this year, Farmville co-creator Mark Skaggs jumped ship to Bangalore-based Moonfrog Labs from free-to-play mogul Zynga. There’s no doubt that India is an exciting player to watch in the mobile marketplace. As long as India’s tech-savvy population grows, so will their affinity and appetite for games, locally-produced or otherwise. By the end of this year, over 200 million Indians will own at least one smartphone. Nobody wants to ignore 200 million people. You simply can’t afford to.

The post Teen Patti and The Rise Of Mobile Gaming in India appeared first on Kill Screen.

Steno Hero might make transcription tolerable

There are many reasons a writer might resort to fabulism. None of them are sufficient justifications, but some are more understandable than others. Chief among these reasons, one imagines, is the undeniable fact that transcription is miserable, tedious work.

Steno Hero, with apologies to Donald Trump but mainly to its creators, aims to make stenography great fun again. Talk about an uphill battle. It’s like karaoke, only instead of belting out lyrics to songs, you type them in sync with the music. Good luck with that. Mechanically, Steno Hero is Guitar Hero with words instead of notes. (The name may have somewhat given the game away.) The challenge of typing while listening to music, however, is that letters are not discrete in the same way as notes; they can be silent or combined in ways that mean your keys aren’t really clacking in tune with the music.

Life is full of distractions, even when you’re just trying to type. Sound recordings for transcription are notoriously awful. People talk over one another. Everyone other than you has an accent—only not really. All of which is to say that the distractions provided by Steno Hero, while not exactly lifelike, do serve a purpose. Stenography is not simply typing; it is the art of coping with distractions as you type effectively and at speed.

But is it fun? As far as typing training goes, probably. It all depends on your taste in music, I guess. There is, however, something mildly oppressive about the most menial of tasks being turned into stylized fun. Can grunt work not be grunt work anymore? There’s something to be said for making menial tasks more pleasant (namely: yes, please, and thank you) but Steno Hero isn’t actually doing that: stenography and transcription in the real world will remain boring and tedious tasks. At least you can now crack a smile while practicing.

You can purchase Steno Hero over on Steam.

The post Steno Hero might make transcription tolerable appeared first on Kill Screen.

Why adults are drawn to teenage stories

As you walk into Gallery 625 of the European Paintings department in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you confront a rather puzzling work. Madonna and Child, by Italian painter Duccio di Buoninsegna, is much smaller than its neighbours, barely the size of a standard US letter. While its peers float in ethereal realms of shining gold, Duccio’s gilding lacks lustre, the tracery of cracks on its surface evincing the painting’s extreme age. Even the colors are not as bright. Mary’s dress, which dominates much of the scene, appears to be painted in somber azurite, rather than the brilliant ultramarine that joyously adorns her virgin frame throughout most of the museum. It is certainly a beautiful piece, just not as arresting as many of the Met’s masterworks. Why then, does it warrant a private glass case, placed in the most prominent and accessible part of the gallery? Why did the Met, according the New York Times, spend $45 million, the highest value it has ever paid for a single piece of art, on a seemingly unremarkable depiction of the Madonna?

Before Duccio, depictions of children in Western art were always symbolic of the divine

The answer lies not in how Duccio’s famous work looks, but what it represents. Take a look at how the infant Jesus and Mary interact and gaze at each other. Before Duccio, depictions of children in Western art were always symbolic of the divine. A stern baby Jesus with adult features (such as a full beard) would regard the viewers with an imperious air, sitting on a Mary whose sole purpose was often literally that of a seat, a sedes sapientiae or “Throne of Wisdom”. To Susan Douglas at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, this particular painting is a departure from the norm because it “expresses the emotions of love and tenderness between mother and child.” This is arguably the first time in Western art that a child is allowed to simply be, and not just act as a stand in for some moral or spiritual higher purpose. Duccio paved the way for other artists, writers, and thinkers to become much more interested in depicting children.

Which brings us to today, where adults regularly consume media originally meant for a younger audience, especially the young adult audience. Be they books, movies, or games, adults are unabashed about their interest—and often obsession—with YA (Young Adult) media. To explore where the appeal lies, let’s first take a look at what children’s media actually is.

Children in Art

While Duccio’s legacy allowed artistic luminaries to depict children, understanding them was another matter. Indeed, the depiction of children in western art has rarely given much agency to children themselves. In Pictures of Innocence: the History and Crisis of Ideal Childhood (1998), art historian Anne Higonnet claims that until the mid-18th century children were considered “faulty small adults, in need of correction and discipline.” At that moment in time, society shifted and, instead, as the University of Virginia’s online project ”Age of Lost Innocence” describes, “Society adopted the idea of the ‘blank slate’ and beginning life in a state of unconsciousness. Art reflected the transition: no longer vessels of psychological and sexual awareness, children became asexual, physically neutral, and psychologically unaware.”

Duccio’s Madonna and Child via the Met

Complicating matters, of course, is the fundamental question of “who is a child?” Scholar of children’s literature Mavis Reimer, in her article “Readers: Characterized, Implied, Actual,” questions our very notion of a child. “Both child and the term in opposition to which it is defined, adult,” she writes, “are understood to index positions within a system rather than to have intrinsic content in and of themselves.” Our concept of the 18-year-old as an adult is fairly arbitrary, recent, and far from universal. Biologically, a 13-year-old that can reproduce is considered an adult.

The history of what is considered “childhood” and how to depict it is complex. Regardless, as Roy Lowe contends in his 2004 article “Childhood Through the Ages,” it was only at the turn of the 19th century and the advent of universal education in Britain, that mainstream Western artistic content transitioned to being “about children, and for them.”

the fundamental question of “Who is a child?”

Where we once had little material to entice those considered too “immature,” we have a whole industry. In the last few years especially, the market for children’s media has exploded. In 2015, Publishers Weekly stated that “children’s print book sales around the world in the last couple of years have been nothing short of fantastic” and that “total print sales in the US rose 2%, but children’s was the key driver, with 13% growth.”

Notwithstanding the fuzzy definition of “childhood,” it’s undeniable that young humans do have different tastes than adults. If common sense weren’t enough, let a 1993 study by Barbara Lehman and Patricia Scharer convince you. In their experiments and subsequent paper titled “Children and Adults Reading Children’s Literature: A Comparison of Responses,” the two researchers conclude that, while “children are capable of analytical, interpretive and evaluative thinking,” “children tended to take the book more at ‘face value’” as compared to adults, and “child readers made few comments about themes”.

But, of course, it’s precisely those fuzzy boundaries—those contested realms under whose twilit skies “juvenile” and “adult” media froth and swirl in an endless maelstrom—that invite exploration.

Young Adult Literature

The world of “Young Adult” content is one such area that sits in the middle. While the term tends to mean teenagers aged 13-17, Young Adult content tends to have a far bigger reach. It’s not even surprising any more to hear that Young Adult media is consumed more by adults than by teenagers themselves. Jim Milliot at Publishers Weekly reported (along with the cold, hard numbers) that between December 2012 and November 2013, “The single largest demographic group buying young adult titles in the period was the 18- to 29-year-old age bracket” (and it might also be worth noting, in case the word “adult” was thrown around lightly, that the average age of marriage in the US is around 28).

This trend hasn’t gone on without drawing some ire. In 2014, Ruth Graham at Slate lamented the falling literary standards of grownups. “We are better than this,” she bellowed in loud pull quotes, maintaining that “adults should feel embarrassed about reading literature written for children”—the emphasis is hers. The backlash was swift and widespread, with authors, critics, and librarians coming to the defence of indignant YA fans, condemning Graham’s arguments as simplistic and short-sighted. Indeed, literary agent Sarah Burnes argues in The Paris Review’s blog that “the binary between children’s and adult fiction is a false one, based on a limited conception of the self.”

the binary between children’s and adult fiction is a false one

If Burnes’s statement seems at odds with the previously mentioned study by Lehman and Scharer, it’s worth perusing professor of Library Science Amy Pattee’s cogent article “Is it Time to Move the Books: Considering Your Library’s YA Fiction Collection,” where she proposes that “we might begin to think about young adult literature as a genre rather than an audience designation… like horror, romance, fantasy and science fiction that teens and adults enjoy reading.” To Pattee, YA literature is not lesser, merely different, and possessing tropes and common themes just like any other genre. “Young adult books, then,” she continues, “are distinguished by their attempts to capture an authentic teen voice that may, by virtue of the teen character’s lack of a teen character’s lack of time spent on earth…be ‘linguistically narrow’.”

Steven Universe , Transformation, and Fantasy

Underscoring Pattee’s thesis are media that unabashedly cater to a dual audience: children as well as their adult guardians. Cartoon Network’s Steven Universe (2013-present) is one such example. As Emily Gaudette writes for Inverse, “Steven Universe…is not quite a children’s show that appeals to adults as a secondary demographic; it satisfies both groups.”

Steven Universe is an animated TV show about a preteen boy, the titular Steven, and his three monster-fighting, alien aunts, The Crystal Gems. Created by Rebecca Sugar, Cartoon Network’s first solo female show creator, the show has garnered numerous awards and much critical praise.

The show certainly has a lot going for it. Its pastel interpretation of a (semi-) post-apocalyptic Earth dominated by pinks, purples, and aquamarines is gorgeous. Its original music, much of it composed by Sugar herself, is sublime, ranging from charming folksy numbers about Steven wanting to see his aunts’ superpowers, to hip-hop anthems about the power of mutual love.

But it’s the writing that really speaks to adults. The world of Steven Universe is a rich stew of fantasy and science-fiction, its sweet overtones masking surprisingly bitter notes of longing and sadness that waft out when you least expect it. But as any good piece of speculative fiction, the fantasy elements are a metaphor for something much more real and relatable. In this case, that something is the idea of growing up and transforming.

Much of YA fantasy deals with transformation. As YA novelist and English professor Marie Rutkoski puts it for i09, “Transformation is fantasy’s bread and butter. Magic, new creatures, new worlds—all either show transformation in its very act or transform a perception of reality. Fantasy is deeply invested in the liminal.” Steven longs to grow up and transform into a fully-fledged Crystal Gem. He’s often troubled by how his alien mother, in order to birth him, sacrificed herself and essentially transformed her essence (her gem) into the boy named Steven. His brief foray into seeing the future in the episode “Future Vision”, to quote Wired’s Eric Thurm, “makes literal the terrifying, exhilarating epiphany of childhood growth.” And he’s fascinated by how his aunts can fuse into one powerful being and even sings about it in the episode “Giant Woman,“ which Kendra Beltran of Cartoon Brew surmises is a “a symbol for a growing boy going through some changes.”

Fantasy is deeply invested in the liminal

Most notable is the episode “Alone Together,” where Steven himself gets to fuse with his crush and best friend Connie Maheswaran, and experience a real transformation. The two’s combined and transfigured self, the older, gender-ambiguous Stevonnie, serves both as a vehicle to experience the anxieties and exultations of adulthood, and as a gentle metaphor for burgeoning sexuality, a literal “coming together as one.” Sugar herself has commented on Stevonnie as “a metaphor for all the terrifying firsts in a first relationship, and what it feels like to hit puberty and suddenly find yourself with the body of an adult, how quickly that happens, how it feels to have a new power over people, or to suddenly find yourself objectified, all for seemingly no reason since you’re still just you.”

Rutkoski argues that it’s the idea of transformation in YA media that draws in so many enthusiasts of all ages. “Readers—of any kind of book—want to behold a transformation,” she writes. “First experiences draw us in because they are the crucible for change. And while of course we expect adult characters to cope with change… it is not patently the essence of the adult experience in the same way it is of youth.” Rutkoski’s final statement is probably the most significant: that change is the essence of the young adult experience, and therefore YA fiction is the best medium to depict it. In On Three Ways of Writing for Children (1946), preeminent author C.S. Lewis notes that sometimes, one writes a children’s story purely “because a children’s story is the best art-form for something you have to say.” Through Steven’s naïve eyes, the complications of life are simplified and flattened, the rose-tinted shadows a very literal depiction of his worldview. As such, acts of transformation are felt more strongly by the viewer, who shares in his gaze and naiveté.

“The medium is the message,” Marshall Macluhan’s famous quote from his 1964 book Understanding Media: the Extension of Man, is often cited by game designers as a guiding principle of good design. Steven Universe shows that the principle holds true for any medium, and that for certain themes, children’s literature and programming really is the most potent medium for conveying the message.

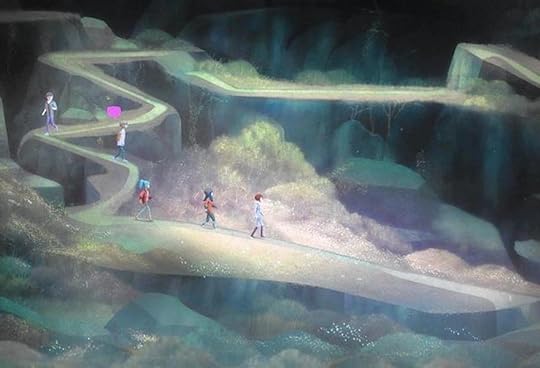

Oxenfree , Escapism, and Nostalgia

Once Macluhan has been invoked, it’s inevitable to fall down the rabbit hole: can we exploit an even better medium to convey our message? Certainly: videogames. Growing up and transforming aren’t mere abstract entities, they are processes that one undergoes. And as influential games scholar Ian Bogost makes the case for almost ad nauseum in his book Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (2007), gameplay is exceptionally well-suited to convey messages about procedural concepts. “When we recognise gameplay,” he says, “we typically recognise the similarities between the constitutive procedural representations that produce the on-screen effects and controllable dynamics we experience as player.”

Which may explain why the gaming industry seems to have been taking a keener interest in YA narratives, with well-received teenage-centric titles such as Life Is Strange (2015) and this year’s Oxenfree. It’s good to note that some of these titles might not actually be targeted at teens, which would make for a further blurring of the arbitrary divisions between “Adult” and “Young Adult”, and yet another point in favor of Amy Pattee’s “YA-as-a-genre” idea. Life is Strange, for example, whose plot follows a (albeit super-powered) teenage girl, was deemed “Mature” by the ESRB (which is one step above “Teen”).

Oxenfree is an interesting example because it performs little of the “escapist” work that is so often attributed to YA media, and to its appeal in the adult market. In an article in The Guardian titled “Why are so many adults reading YA teen fiction?” Goergina Howlett writes that “the fantastical worlds and sheer inventiveness and imagination of YA is rarely rivalled by adult literature.” This stance is debatable. Writers such as Neil Gaiman, Terry Pratchett, and China Mieville have painted us highly detailed pictures of fantasy worlds geared originally to an adult audience (their diverse readership, notwithstanding). The argument that credits the popularity of YA literature merely to escapism robs the literature in question of much of its complexity.

Unless your escapist fantasy is to return to your adolescent youth, Oxenfree’s core tenet, one could argue, is precisely the opposite of fantasy escapism. Rather, the game focuses on the real, on nostalgia, and returning to what it felt like to be a teenager. While the horror elements of the game are certainly important, they aren’t the heart or even the best-executed parts of the game. “Oxenfree is absolutely a game about teenage bullshit,” Chase Ramsey wrote in his Kill Screen review, while to ZAM’s Nate Ewert-Crocker, “Oxenfree feels very authentically a game about being an adolescent, as though someone had scrubbed all the awkward teen-isms from Life is Strange and replaced them with more realistic dialogue.”

Oxenfree’s core tenet is precisely the opposite of fantasy escapism

That’s not to say that escapism is bad, or that Oxenfree eschews all forms of escapism completely. On the contrary, the game begins with your protagonist Alex, along with her new stepbrother and her best friend, reifying the idea of escape as they head to a lonely island to indulge in what they hope to be Dionysian revelries with fellow classmates, complete with drugs, booze, and sexual tension. And it’s easy to get drawn into the striking art. Where Steven Universe engages you with soft, warm tones and quirky charm, Oxenfree intrigues you with haunting but wonderfully detailed backdrops and moody lighting, lighting that casts more shadows than it dispels, birthing patches of darkness pregnant with sinister possibilities.

While the narrative progression and the puzzle-solving in Oxenfree is fairly linear (and in the case of the puzzle mechanics, somewhat tedious), it’s your interactions with the well-rounded characters that constitute the emotional core of the story. It would have been fairly easy for Night School Studio to inject high-school stereotypes and teen angst into the game’s story, but they display admirable restraint, focusing on believable dialogue and tense shifts in relationship dynamics. Much of the game involves you choosing what to say next, and while it doesn’t always alter the plot drastically, it does affect your emotional experience of it. Will your Alex be stubborn, silly, selfish, or sullen? Or even silent? It’s entirely up to you.

And yet, much like in the Mass Effect and Dragon Age games, the dialogue options you choose aren’t exactly what Alex says. No, she expands and elaborates, sometimes not entirely in ways you intended. To Ewert-Crocker, “the dissonance between prompt and response actually works to the game’s advantage.” It forces you to think of Alex as a separate character, not completely under your control.

Which makes sense for adult players. You aren’t a teenager, and playing as one won’t change that. But that’s not the point. YA media isn’t meant to be a fountain of youth, but a way for adults to rethink what it means to be a teenager, how teenagers view the world, and what grownups can learn from that. As Meg Wolitzer at the New York Times reflects in “Look Homeward, Reader: A Not-So-Young Audience for Young Adult Books”, with YA media, “I’ve been given access to a pure form of the complications involved with being young, now filtered through the compassion, perceptions (and barnacles) of my older self… it’s broadening to spend time around the losses and transformations of young characters without having to cast myself in the role of a parent or authority figure.” The gaze of a fictional teenager is alien enough to challenge adults and force them into confronting new perspectives, yet accessible, universal, and intensely familiar.

Monsterhearts , Exaggeration, and Emotion

On the opposite end of the spectrum from grounded portrayals of teenage interactions lies Joe McDaldno’s 2012 tabletop role-playing game Monsterhearts. In Monsterhearts, players take on the role of teenage monsters (such as vampires, ghosts, werewolves, and ghouls) in a modern-day setting. Like in any tabletop RPG, and unlike in most digital games, Monsterhearts players actually inhabit their characters, trying to determine precisely how their characters would think, act, and react to certain situations, even sometimes speaking in their characters’ voices. This doesn’t mean that they lose their sense of reality and become these characters (despite what the moral police of the 80s say): as scholars Dennis Waskul and Matt Lust argue in their paper “Role-Playing and Playing Roles: The Person, Player, and Persona in Fantasy Role-Playing,” a key part of playing any RPG involves separating and negotiating boundaries between the player and the character they’re playing.

But as discussed, playing a character can be a powerful tool to understanding different points of view, and a tabletop role-playing game intensifies this by allowing players to actually get inside a character’s head. Not that these characters are necessarily realistic. In her New York Times article, Meg Wolitzer clarifies that “The point of these books [or other media, in our case] isn’t just (or even necessarily ever) ‘verisimilitude.’ (If verisimilitude were the aim, then why not only read Y.A. novels written by 13-year-olds?)” In fact, Monsterhearts revels in exaggeration. In its world, teenagers are dark and mysterious, seductive and cruel, wielding both sex and violence as mere tools.

You play to get lost, and to remember

But the exaggeration is used for a purpose. As sociologist Gary Allen Fine wrote in Shared Fantasy: Role Playing Games as Social Worlds (1983), “by simplifying and exaggerating, games tell us about what is real.” Yes, Monsterhearts is about the supernatural, but it’s more fundamentally about the complexities of human emotion and action. The game’s introduction highlights this point: “You play because the characters are sexy and broken. You play because teen sexuality is awkward and magnetic, which means it makes for brilliant stories. You play because despite themselves, despite the world they live in, despite their fangs and their bartered souls and their boiling cauldrons, these aren’t just monsters. They’re burgeoning adults, trying to meet their needs. They’re who we used to be—who we still are sometimes. You play to get lost, and to remember.” So while a player might spend one scene negotiating a price with a demon (which could act as a metaphor for addiction, perhaps), they may spend the next agonizing over a prom date.

Monsterhearts allows adults to explore difficult emotions, emotions which they may have encountered in the past but still give them pause. In an interview with the blog Giant Fire-Breathing Robot, MacDaldno himself illuminates this further: “[As adults] we hit a point in our lives when we stop giving ourselves permission to be irrational, volatile, to live life in the moment. But those impulses don’t just vanish because we want them to.” And to truly understand this and the power of the RPG, it’s important to remember that a tabletop role-playing game is a collaborative experience. No single authorial voice controls the actions and the players themselves (helped by the game master) decide where the narrative takes. RPGs, and Monsterhearts especially so, hand players authority to decide what emotions to delve, what impulses to give into, and what temptations to fight. And if young adult stories are most conducive to such exploration, then so be it.

///

It’s nice to think of Duccio as a rebel. He defied liturgical convention to depict the actual human relationship between a mother and child. True, his piece was destined for a private home or chapel, far from the prying eyes of the clergy, but he nevertheless took a risk. Through Duccio’s legacy, people began to really think about what it means to be young, how youth relates to age, and what adults can take away from paying attention to and understanding younger generations. And there’s really no reason for us to be embarrassed by that.

The post Why adults are drawn to teenage stories appeared first on Kill Screen.

May 19, 2016

Lady of the Shard questions the role faith should play in our lives

Lady of the Shard is the latest webcomic from Gigi. D.G., the creator of anthropomorphic bunny comic Cucumber Quest. It’s about faith, starcrossed lovers, and the different ways in which the devout relate to the holy. Following the story of an unnamed space acolyte who lives on a floating temple in the middle of a distant solar system, it explores how her life changes as she discovers a burgeoning attraction to the Goddess she serves. Like many classic love stories, the two are kept apart by class divides, though in this case, they are less economic and more metaphysical. As they connect, the would-be couple uncovers not only each other’s pasts, but also that of an entire universe, revealing a story that uses the dynamics of relationships to question what role deities should play in the lives of their children.

Christianity comes in many forms, some more forgiving than others. While some sects might weigh a person’s good deeds against their sins to see whether or not they are worthy of God’s love, others simply require that all a follower do is believe and repent. I was raised in the second camp. At first, it seemed a comforting prospect, the idea that I didn’t have to earn salvation. But with grace comes guilt.

I was taught that I was inherently sinful. That I, as well as anyone else who ever has or ever will live, did not and would never deserve God’s love. That we were evil and nothing, and without God’s pity, hell was our natural state of being. I was taught that if I wanted to survive, I needed to prostrate myself before him. The success of myself or my family meant little compared to the words I recited nightly to an omnipotent being who apparently still needed the comfort of a child to feel secure. In my church, praise was all we ever existed for, and to have pride in oneself was to go against our purpose. I was sold the image of a loving creator, but I found myself in debt for the crime of being born.

As Lady of the Shard begins, this is the situation our acolyte finds herself in. Her life is one of rituals and obedience, and her little quirks of individuality are punished by her peers. She is afraid to take credit for her work, and constantly plays down her importance in light of her duty and her superiors. She is devout—more so than most—but because her faith manifests itself in an unfamiliar way, she is a misfit. While others see their Goddess as more of an idea or a social custom, she truly loves her, taking the devotion she was taught to an almost romantic level. The problem is that she treats her beloved like a fellow human being, ditching traditional reverence to show her the same kindness and familiarity she would extend to anyone else she liked. In other words, if everyone else leaves the Goddess treasure for their daily offerings, she leaves her pancakes.

I was sold the image of a loving creator, but I found myself in debt

I have never met someone who doesn’t like pancakes. This goes for the Goddess, as well. After a few instances of otherworldly intervention, it becomes apparent that the acolyte, despite her oddities, is favored. The high priestesses hem and haw, before offering her a chance to clean a long-forgotten sacred chamber. In her enthusiasm, she accidentally bumps into an ancient bell, and within a few a short panels, her Goddess heeds her call and joins her in physical form.

What follows is a long-dive into the history of the universe the comic takes place in, complete with twists and turns and battles with other deities. Continuing the trend set forth in the beginning, this is largely done through the lens of relationships, as our acolyte explores different positions of powers in her flirtations with various Gods and even other mortals. Some are healthy, others are abusive. All are, for their divinity, recognizably flawed.

What stuck out to me most, however, were the conversations shared by the acolyte and her Goddess early into their meeting. As the acolyte bows to her and declares her lack of worth, the Goddess tells her to rise. In a comforting voice, she explains that the reason she became interested in the acolyte in the first place was because of how she would speak to her in her prayers like an equal. She would ask her about her concerns, and take into account feelings that others considered the Goddess to be far above. While the acolyte still considered herself lesser than her Goddess, it was her willingness to empathize with her that drew her in. The Goddess almost seems mournful over how small the church has made the acolyte feel.

The two begin to talk about the distant stars, technological metropolises that have wavered in their faith due to their prosperity.

“Is it really OK for the people you rescued to stop paying tribute to you? Isn’t it ungrateful?” asks the Acolyte.

Her Goddess responds.

“A goddess does not demand tribute, Acolyte. If the refugees no longer need me, they are likely enjoying an age of peace. Do you not consider this a good thing?”

This is unconditional love

This selfless giving is entirely different from the type of God I was taught to worship. In a brief moment of contemplation alone, the Goddess wonders about her place in the universe. It is not that she dislikes offerings—everyone enjoys a little recognition now and then—but she concludes that she is better than needing them. She applauds seeing her children independent and prosperous, happy just to see them grow. “The Distant Stars may do as they like,” she declares.

This is unconditional love. It has its risks and its sadness, and as the comic plays out, the Goddess must contend with them. However, in her power, she feels they are well worth taking. It’s the type of sacrifice a parent offers their child, as they leave home and forget to call. It hurts, but there is also pride to be found in their success.

As the comic progresses, it moves beyond the temple as the acolyte and Goddess explore both an atheist society, as well as a society ruled by a different Goddess who demands subservience from her people and constantly reminds them that they are nothing. But despite making strong claims about the dangers of faith as manipulation, Lady of the Shard doesn’t outright condemn any of these cultures. Rather, it explores the types of relationship they offer, and the happiness that follows when those involved care less about power dynamics and more about bringing out the best in each other.

You can read Lady of the Shard over on Gigi D.G.’s itch.io. To see updates on her work, follow her on Twitter.

The post Lady of the Shard questions the role faith should play in our lives appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers