Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 120

May 16, 2016

Anarcute puts a friendlier face on revolution and rioting

Punk music. Chains. Leather, drugs, mohawks, and spikes. The revolution, at least as far as it’s depicted in films like The Warriors (1979) and comics like The Dark Knight Returns, is often offputting and grotesque. These stereotypical trappings are hardly an accurate representation of real punk culture or political upheaval, of course—featuring teens tagging anarchy symbols on school playgrounds or mugging innocent strangers on their way home from work—but they do work well to create a sensationalized moral panic for a square-jawed Clint Eastwood type to come clean up.

Unfortunately, they also raise a question. If the revolution is supposed to be so fringe, then just where are these seemingly large gangs supposed to recruit new members once they’ve finished swinging by all the local leather bars?

Enter Anarcute, a revolution with a softer touch. Originally created as a school project by a group of five students from French videogame school supinfogame, the game focuses on a group of rioters fighting against the “very very mean” Brainwash Patrol. Like a more earnest Hotline Miami (2012), the game’s rioters recognize each other by wearing “cute-Kawaii” animal heads, meaning players control whole groups of bunnies, kitties, and frogs as they march through levels and increase their numbers.

a revolution with a softer touch

It’s also got a bit of a collectible element to it, with the website promising more than 70 different animals to recruit, including oddballs like horned beetles and snails. As players snag more rioters, they’ll fight back by tossing cars and other debris at the Brainwash patrol, even going so far as to take whole buildings down if need be. “Our rioters are ready to do anything,” write the game’s creators. “Even if it means destroying whole cities to rebuild later.” While the team recognizes that this “could be a rather sad and dark game” if seen in a different light, they insist that the game is meant as more of a comedy, and that we are in good hands. “Who better than a bunch of French people can make a game about riots?”

It’s a more widely appealing take on revolution than we’ve seen in other riot stories, offering a friendly entry point for people who might prefer Pokémon-style critters to the rough-edged counterculture of Akira (1982), or even the free-love antics of Burning Man. Inclusive and sharable, it reflects a time when revolution sprouts up in hashtags as often as it does in boarded-up back alleys.

Anarcute will be coming to PC and Xbox One this summer. To learn more, visit its website.

The post Anarcute puts a friendlier face on revolution and rioting appeared first on Kill Screen.

FPS has something to say about videogames and guns. But what?

Hugo Arcier’s FPS is about last year’s attacks in Paris, though it is not immediately clear in precisely what way. We know this because the artist says as much on his website: “FPS is a post November 2015 Paris attacks art piece. The artist deals with blindness hijacking video game codes, in particular of first person shooter game. The only visible elements are pyrotechnic effects, gunshots, muzzles flashes, sparks, impacts, smokes.”

In practice, what that means is that a black space is lit up by flares from something vaguely resembling a videogame gun. They linger in the air, like lasers at prog-rock show. The effect is hauntingly beautiful.

unsettling and imprecise

That, in turn, raises a troubling question: How many rounds are you willing to see fired in the name of sustained beauty? The rounds illuminate vague silhouettes; you are not simply shooting into the void. Actions have no clear consequences in this world, but it might be best not to find out. Would you rather just sit in the dark than risk whatever moral complicity Arcier is getting at?

These are good questions, though FPS does not seem sure of how to answer them. Insofar as it is an art piece about the Paris attacks, which included the killings at the Bataclan concert hall, the strange overlap between rock show and gun imagery is unsettling and imprecise. Moreover, it is not entirely clear where the videogame aesthetics really fit in to this story. Is the viewer to assume that they have some connection with terrorism? In that respect, FPS lacks the moral clarity of Pippin Barr’s A Series of Gunshots. FPS is beautiful enough to captivate a viewer and make them think about these questions—and for that it should be lauded—but it falls short once you start looking for answers.

Find out more about FPS on its website.

The post FPS has something to say about videogames and guns. But what? appeared first on Kill Screen.

Test your inventory management skills in a new puzzle game

Inventory management is a tedious part of videogames. I’ve never found myself daydreaming of the minuscule inventory in Resident Evil (1996) (though I do remember that opting for playing as Jill netted you two more slots). Nor have I ever found myself enjoying the meticulous disposal of items over-encumbering Geralt of The Witcher 3 (2015). Even with the largest saddlebags hanging onto my dear steed Roach in that game, I often had to spend minutes at a time digging through and tossing out the most unnecessary junk to make room for something new and shiny. And in Witcher 3-time those minutes eventually became hours upon hours over the length of its massive campaign. That’s hours of just managing my inventory. Inventory management sucks, except when it doesn’t have to.

Your inventory is the puzzle

Game designer Dan Harris’ latest game jam title, aptly named Inventory, is part-Twine-like text adventure and part puzzle game. In this game, your inventory is the puzzle. The player is tasked as a father in a post-apocalyptic world that an ominous “sickness” has destroyed, constantly managing all that he can carry within his ever-dwindling inventory.

The inventory’s necessities are divided into three necessary sections: attack (weapons), health (first aid kits, food), and “story” (from gas cans to keys). Managing how all the pieces fit, however, is a tad more complicated. In the game, there are meters for each of the three components, and a collection of items to squeeze into your rectangular suitcase. Stacking these items on top of one another is the simple part, but doing so in a way that fulfills the meters is where it gets tricky.

Inventory was made during a recent Ludum Dare game jam (the world’s largest online, recurring jam), within the event theme “Entire Game on One Screen.” With such broad guidance, the resulting collection of game jam titles is as absurd and diverse as one can imagine. Harris’ game is the simplest take on the theme: a puzzle game, a text adventure, all neatly laid out within a single screen.

Fulfill your post-apocalyptic suitcase-organizing needs in Inventory here in your browser, or download it for PC .

Edit: A previous version of this article noted that Inventory was the product of Ludum Dare 35 instead of 31, it has been amended to correct this mistake.

The post Test your inventory management skills in a new puzzle game appeared first on Kill Screen.

A spy thriller that you play by using your ears

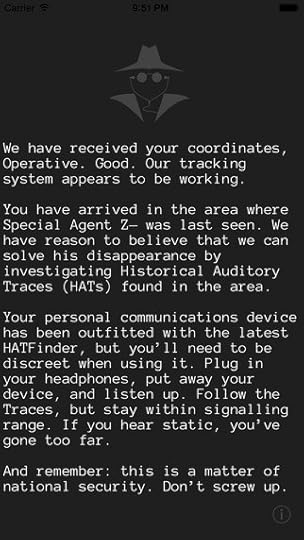

The screen blinks. Instructions arrive. “Plug in your headphones, put away your device, and listen up…if you hear static, you’ve gone too far.”

HATFinder (2015) is a mobile-based spy game that’s not played on the screen. The initial instruction screen is the one and only time you’ll see anything on your phone. The rest of the time it’s played with your ears. Under the backdrop of a missing agent, it’s your role as a spy to investigate what happened. In short, the game is a sound-based scavenger hunt. While navigating a physical space—the game is specifically designed to be played at the UCLA campus—players try to find audio clips known as “historical auditory traces” (HATs) to reveal the game’s narrative and uncover the mystery.

Originally made for last year’s Inertia Conference, a sound and media conference in Los Angeles, the game is the brainchild of Lauren Burr, David Jensenius, and Mark Prier. It’s been described as an augmented aurality game. These games are part of a larger umbrella known as locative media—works relying on players navigating physical spaces to activate game events. And for games like HATFinder, these events are delivered primarily through audio form.

I caught up with Burr after her talk on “Overcoming the Visual Interface” at the Technoculture, Art, and Games research center in Montreal. She cites Janet Cardiff, a sound artist known for her location-specific “audio walks,” as one of the inspirations for the game. However, what is different in HATFinder is the presence of two different types of sounds: sounds that play on certain geographic zones while others are “sound trails” that act as audio breadcrumbs leading players to these different zones.

bring down the technical barriers of creating augmented aurality games

“When you put on your headphones, you’re hearing all these different sounds at once and they’re pulling you in different directions,” Burr explains. “It sounds really pretty but it takes a lot of concentrated listening to actually figure out how to manipulate the thing so you can get the information and the clues that you need.”

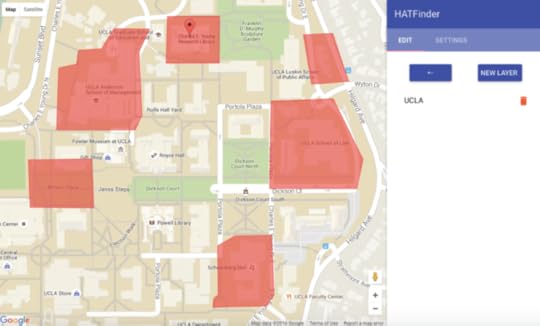

Burr and her team developed the game as a proof of concept to show the capabilities of HATengine. This engine is a Twine-like tool they developed to help bring down the technical barriers of creating augmented aurality games and sound installations. With the engine, artists and game makers can simply draw polygons on a map and upload the associated audio clips—turning any physical space into a playable and interactive environment. These works can then either become their own stand-alone apps or (by publishing and sharing the work through HATengine itself), they can immediately be played through the HATengine app.

Currently in development, the team hopes to expand the engine to include more ways to affect the listening experience—from the time of the day, the weather, to knowing whether or not you’ve played the game before. While not publicly available yet (though Burr says to contact her if you’re interested in trying the engine), her team hopes to eventually open it up so anyone can make their own HATFinder-like game.

HATFinder is available free on iOS . The engine behind the game, HATengine, is currently in development but open to anyone who wants to build similar sound/location-based works. For more information, contact Lauren Burr or visit the official website .

The post A spy thriller that you play by using your ears appeared first on Kill Screen.

An upcoming game lets you explore Mesoamerican ruins as a wolf

Mooneye Studios looked to narrative-heavy titles like Journey (2012) and The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess (2006) for its upcoming game Lost Ember. And like those titles, it began as a third-person exploration game with puzzle elements, but much of the development process has so far involved paring away its more traditional design concepts. “We felt that they [distracted] from what we are really trying to do,” says Mooneye’s CEO Tobias Graff. “We want to create an experience and trigger certain emotions, get the player to feel the story, and these mechanics always felt wrong for that. The main drive in Lost Ember comes from the story and the world itself.”

Players inhabit the role of a wolf with the power to command other forest animals, such as a parrot, for a limited time with the use of a magic bar. According to Graff, the single-player mode is all about the process of discovery. “The story is told through flashback sequences that take you back to a time where massive temples and huge cities demonstrated the power of the civilizations that lived in this world. Now, nature has claimed back what was taken from her, and there isn’t much left but overgrown ruins.”

The game’s world building is based largely on the history of the Inca and Maya civilizations, as well as other lost cultures throughout time. “Our narrative designer created a very detailed and complex history for all of these cultures,” Graff explains, “and the player will follow the path of one person who lived in this world and experienced the fall of the old empire through her eyes.” There will be flashback sequences that unveil the history this character has seen, triggered by the discovery of ruins and artifacts—the motivation for this character’s forward exploration. Graff hopes that players will be similarly motivated by this pursuit, and is banking on the different exploration possibilities that each animal character offers to encourage players to venture off the beaten path.

“it is really cool to just run through the woods or fly high above the ground in VR”

The studio’s next big challenge over the coming months will be securing funding, which it is hoped will be achieved through a crowdfunding campaign and a polished demo of the game’s first 30 minutes to show at this year’s Gamescom in August. Such additional funding would allow for time to finish the project, and—should certain stretch goals be reached—possibly reincorporate the co-op multiplayer mode from their earlier prototypes.

What should help establish prestige is the fact that Solid Audioworks—the audio team founded by Rockstar pioneers Craig Conner and Will Morton after two decades of working on the Grand Theft Auto series—is providing the game’s music and sound. And, most recently, at last month’s Gala of the German Computer Game Awards, the team behind Lost Ember was awarded the second prize for Best Junior Concept.

Presuming the crowdfunding goes well, Mooneye hopes to bring Lost Ember to PC, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One. VR is also being considered and a short VR demo was recently made that let people who attended the A MAZE. festival in Berlin to fly through the game’s world. “We’re not 100 percent sure [VR] will work, as Lost Ember is a third-person adventure and we might have to change a few things in how the camera works,” Graff said, “but it is really cool to just run through the woods or fly high above the ground in VR—so it’s definitely on our radar!”

You can find out more about Lost Ember on its website.

The post An upcoming game lets you explore Mesoamerican ruins as a wolf appeared first on Kill Screen.

The Aztec pessimism of A Machine for Pigs

“When, for instance, a man had fallen into one of the rendering tanks and had been made into pure leaf lard and peerless fertilizer, there was no use letting the fact out and making his family unhappy.”

—The Jungle, Upton Sinclair

We are familiar with Aztec myth only insofar as it is a byword for cruelty and human sacrifice. The image of the reluctant offering climbing the stone steps of the pyramids at Tenochtitlan only to have their chest cut open and their beating heart plucked out is repulsive to both the value we place in human life and our sense of decorum. This connotation is, to a certain extent, unfair: the purpose behind these sacrifices was not founded in naked cruelty, and they were, often enough, more symbolic than literal. Just as the offering was being flayed at the festival of Xipe Totec, so to did the audience peel off and offer husks of corn as a symbolic parallel. And yet the drama of grisly sacrifice finds an interesting thematic niche in 2013’s Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs.

At first blush, the videogame relies upon the dehumanization inherent to industrialization as a foundation for its horror. Its backstory reinforces this point: a well-meaning industrialist, Oswald Mandus, spends the bulk of his fortune on livable wages and safe factories, only to find that his prices are no longer competitive, his profit margins are non-existent, and he is in danger of losing everything. After discovering more unconventional ways of cutting costs (i.e., magic), Mandus becomes consumed with creating a grand machine that will cure the world of its inherent suffering. The game itself takes place on New Year’s Eve, 1899, when an amnesiac Mandus is told to enter the machine in order to rescue his children. During the descent, the player finds little models of Mesoamerican step pyramids scattered throughout the factory like an artist’s signature, and you cannot understand the precise horror A Machine for Pigs presents without knowing why they are present.

Our world turns because of the sacrifice of others

The Aztecs and other Mesoamerican civilizations ran upon the idea that sacrifice makes the world go round: by offering up the vital energy of the world, they were both following the gods’ example and giving the sun the momentum required to keep rising. At a distance, this thought is not so foreign to us moderns: we rely on the more or less figurative sacrifice of parents, teachers, friends, firefighters, police officers, doctors, and so on. It is common to say, upon meeting a soldier, “Thank you for your sacrifice.” We commemorate Remembrance Day (or Veteran’s Day) as an acknowledgement that our world was built on the sacrifice of those who came before. In a very real way, our world turns because of the sacrifice of others.

But this presentation is the idea in its most positive light. Our world also turns due to less glamorous, crueller, more exploitative sacrifices. Thanks to children mining cobalt in the Congo, I have a smartphone and a computer; slave labor in the seas off of Thailand feeds our cats. We can look further back for other examples: in the 18th century, the Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire acknowledged that the sugar he stirred into his tea was only possible because slaves were whipped in far-off Haiti; at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the poet William Blake wrote “that life liv’d upon death / The Ox in the slaughter house moans.” Both in the past and the present, our world runs on the engine of human suffering—as Blake puts it elsewhere, we all drive our carts and plow over the bones of the dead.

Aztec Human Sacrifice – Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

There is a difference, of course, between the voluntary sacrifice inherent to service and the compulsory nature of slavery and slaughter, just as there is a difference between the voluntary offering of one kind of Aztec sacrifice and those of the prisoners captured in various Flower Wars, or in the purposeful massacre of civilians and the accidental death of a factory worker. But A Machine for Pigs does not parse the characteristics of these sacrifices: in an industrial system, quantity matters over quality, and the blood is just as red no matter how it is spilled. Further, perhaps it is mistaken to view these cruelties as causal, but our world functions in no small part due to the suffering of others. This fact is not necessarily the intent of the systems we have in place, but nevertheless the world turns while men and women bleed; it is no great sin on the Aztec’s part that they mistook correlation for cause.

This Aztec theme runs through the entirety of A Machine for Pigs: the first phone-call names Mandus as “Precious Eagle Cactus Fruit,” the name given to the heart pulled from the body of a sacrifice. As noted above, there are miniature models of step pyramids scattered throughout the factory. Mandus refers to himself as various Aztec gods: “I am the jaguar-faced man,” or Tezcatlipoca, the deity associated with obsidian, the material used to craft the sacrificial knife. “I am the feathered serpent,” or Quetzecoatl, a patron deity of the Aztec priesthood. As an industrialist, he is the one who oversees the sacrifice of factory workers, which pump out the products that are bought in stores and give the modern world its momentum. It is only appropriate that he identifies himself as the one who carries out that sacrifice: “This priesthood is mine… I carry the knife of this factory, the bowl of this mill.”

A trip to Mexico is repeatedly mentioned in the flashbacks, and the player eventually learns that Mandus, standing on the stone of a Mesoamerican ruin, received a vision of his two sons dying in the Somme some 16 years hence. And so he kills them to spare them that horror. The references grow only more and more overt as the game progresses: near the end of the game, the player crosses a lake of blood to reach a sacrificial altar. Later she climbs a step pyramid while the voice of the machine gives the game’s most memorable monologue:

I have stood knee deep in mud and bone and filled my lungs with mustard gas. I have seen two brothers fall. I have lain with holy wars and copulated with the autumnal fallout. I have dug trenches for the refugees. I have murdered dissidents where the ground never thaws and starved the masses into faith.

A child’s shadow burnt into the brickwork. A house of skulls in the jungle. The innocent, the innocent, Mandus, trod and bled and gassed and starved and beaten and murdered and enslaved!

This is your coming century! They will eat them Mandus. They will make pigs of you all and they will bury their snouts into your ribs and they will eat your hearts.

This monologue points to where the Aztec theme melds with the game’s more conventional display of the inhumanity of industrialization: mustard gas requires a chemical industry, while the autumnal fallout of Hiroshima needed a total war economy. But the list of horrors extends backwards through time as well. The fall of the two brothers refers simultaneously to Cain and Abel or to Mandus’ boys, Enoch and Edwin. Starving the masses into faith is similarly ambiguous. Are we talking about Aleppo in 2016, or Toulouse in the 13th century? By going backwards and forwards, the list of horrors incorporates the scope of human history; the ease with which the results of the industrial revolution are incorporated into that pattern is then meant to be disconcerting. More troubling still, there is an uneasy interplay between sacrifice and the sacrificer in the shifting image of the pig: they will make pigs of the victims, but the victimizers all have porcine snouts. It is not merely that those who exploit and those exploited are not as far away as we might imagine; it is that the two are utterly indistinguishable. As Mandus notes in a flashback, “We are the pig, professor. We are all the pig.”

There is a reduction present in A Machine for Pig’s use of the Aztec mythos. Absent are the regenerative aspects of the repeated references to sacrifice. The promise of renewal and growth in the flaying of a man are left out in favor of the grim spectacle of the flaying itself. Instead, the game relies upon the eternal recurrence of this sacrifice and the assumption that correlation—the world turns as humanity bleeds—implies causation—the world turns because humanity bleeds—for its horror. The narrative of the game is then based on the decision of a businessman who decides that the benefit is no longer worth the cost and tries to liquidate the whole endeavor. The logic of industrial capitalism then becomes indistinguishable from driving sacrifices up the steps towards the stone altar.

But the darkest part of A Machine for Pigs is the lack of an intrinsic moral force to its horror, the disinterested quality of its presentation—like a structural engineer professionally examining the blueprints for an abattoir. It would be easy to accuse it of possessing a kind of adolescent nihilism—e.g., “life is suffering, and we’re all going to die,” a sentiment common in Final Fantasy villains—were it not for its reliance on the most reductive and basic of presentations: human lives as mere flesh. Its presentation of this first principle—that we are first and foremost animals—is both irrefutable and disconcerting in its implications. In the Aztec model, this means we are subject, like the rest of the world, to the recurrent cycle of death and rebirth; in A Machine for Pig’s model, we are merely another resource to keep the engine churning.

Our world runs on the engine of human suffering

But beyond its fusion of Mesoamerican myth and modern industrial thinking, A Machine for Pigs is a negation of the perennial optimism inherent in Western progressivism, where we perpetually assume that things are always getting better, things are always getting easier, that we are becoming better people than those who came before us. Those at the cusp of the 20th century were not so different from us, and they believed in this sense of progress too. Yet still there were the countless dead of the Somme and Verdun, the Holocaust, and the massacres of the Khmer Rouge or at My Lai. The game avoids any kind of western-centric view in noting these horrors, as we are wont to do when providing self-exculpatory explanations like a “medieval mentality” or “ideological zealotry.”

Indeed, A Machine for Pig’s placement during the aftershock of industrial revolution and the turn of the 20th century establishes firm parallels between then and now: we are only 16 years away from our own turn of the century, and still riding the waves of the digital revolution. And yet children still die in vents and factory collapses and African mines. We are not so far away from the predicated suffering of the 19th century, and earlier. A Machine for Pigs doubts we will ever be.

May 14, 2016

Weekend Reading: Phantom Limbs and Ghosts in the Shell

While we at Kill Screen love to bring you our own crop of game critique and perspective, there are many articles on games, technology, and art around the web that are worth reading and sharing. So that is why this weekly reading list exists, bringing light to some of the articles that have captured our attention, and should also capture yours.

///

Feel Me, Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker

Touch is one of the senses, but it isn’t one thing. Touch can hurt, relax, itch, feel the ground you stand on, and have the sensation of things that aren’t there. Technology, too, wants to wield touch, from virtual reality to prosthetics, technology wants to simulate it. Adam Gopnik writes just how complicated a pursuit that is.

1979 Revolution and the Politics of Choice, Cameron Kunzelman, Paste

Politics are at play in almost every game, but few drop players into key moments in history. 1979 Revolution: Black Friday uses methods similar to those in The Walking Dead games to portray one of the tensest, most influential affairs in the last century. But compared to Telltale’s work, as Cameron Kunzelman elaborates, there are takeaways from the player’s choices, and the ramifications in a setting far larger than one person.

The Computer Virus That Haunted Early AIDS Researchers, Kaveh Waddell, The Atlantic

It’s a nuisance to have your personal computer attacked by malware and viruses, but it’s a bigger crisis when some of these bugs root themselves into medical and hospital tech. Curiously, many of the viruses floating around today resemble one that sabotaged early AIDS research, created and delivered for petty reasons.

Ghost in the Shell and anime’s troubled history with representation, Emily Yoshida, The Verge

Hollywood adaptations of beloved anime series always seemed like veiled threats that never actually materialize. Recently, that threat followed with a Scarlett Johannson vehicle based on Ghost in the Shell, reigniting a public discussion about whitewashed casting. That discussion, however, as Emily Yoshida will explain, is more complicated and historically coarse in Japan, the country where Ghost in the Shell originates.

May 13, 2016

The software behind Lord of the Rings’ giant battles now has a playable demo

There’s a reason The Lord of the Rings film franchise took home the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects three years in a row. While many films fall flat in a matter of years, The Lord of the Rings trilogy and it’s approach to CGI still stand firm more than a decade letter. While there were many breathtaking moments throughout the series, the enormous battles with armies thousands strong were consistently glorious, thanks to the simulation software Massive. And now that very same software is available to anyone for a 30-day trial.

Watching a short demo video quickly illustrates how Massive was so instrumental to giving those battles their intensity and gravity. In the video above, the company reveals some of the secrets to achieving this feat. All the individuals in the crowd act as individuals. Though their goal remains the same, all of these characters take different actions to achieve it, creating a realistic and engaging battle where, no matter where you look, you are seeing a unique vignette of a fight. Or, occasionally of a soldier running away. Although the software was originally created for The Lord of the Rings films, its hand print on visual effects can easily be seen in the Academy award-winning films after it like Inception (2010), Hugo (2011), and King Kong (2005).

Hopefully this increased accessibility of the software will result in some people finding inspiration, doing new things with it. Although Massive hasn’t been used much in games yet (the website boasts it being used in games on both the Xbox 360 and Nintendo Wii) the company says it’s gaining momentum. If they’re right, more glorious chaos awaits.

The wonderful, fake game art of Japan’s annual Famicom exhibition

There’s a special brand of nostalgia for the Family Computer, colloquially called the Famicom. The game console was released by Nintendo in 1986 but never outside of Japan, and was home to many, many cult games. It jump-started a multitude of classic Nintendo franchises, like Mother (1989) (also known as Earthbound Beginnings, when it finally saw release outside of Japan in 2015) and Fire Emblem (1990). Among many other, actual gaming-related reasons, one particular way the Famicom was notable was in its unique multi-colored cartridges—an aspect the gray-plagued Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was missing.

Buried in Tokyo’s Kichijoji neighborhood is a unique shop dedicated to all things Famicom (as well as chiptune music and 8-bit-inspired fashion). The owner of METEOR, the gaming subculture establishment, is Satoshi Sakagami. METEOR, is host not only to Sakagami’s own niche interests, but also serves as a venue of sorts. His annually hosted Fami-Mode is an all-night festival celebrating the greats of chiptune’s micro-scene in Japan, held at a cafe nearby the store. But perhaps Sakagami’s most well-known endeavor is the annual My Famicase Exhibition, hosted at METEOR and curated entirely by the one-man 8-bit fan himself, through the hundreds of artist submissions from all around the world.

dreamy faux-Famicom-game cartridges

The annual My Famicase Exhibition has been occurring for 12 years, each year growing greater and greater in popularity. In the unique exhibit, artists and designers from around the world (not just Japan!) submit their own designs and art for made-up games. Of all the submissions, Sakagami selects around 100 to showcase, and prints the chosen few onto cartridge shaped stickers, and voila: the dreamy faux-Famicom-game cartridges of My Famicase are born.

Graphic designer Walter Parenton has participated in the My Famicase Exhibition for two consecutive years. Last year, his faux-game submission Magical Sleepover Friends was based on a series of original characters, contrary to this year’s original “IP” he established for the meditative Island Time. “Island Time was inspired by my very first tattoo I just got a month ago, which I designed myself,” explained Parenton of his thematic “Meditation Game.” “I called it my permanent paradise. I really love those big-headed Easter Island Moai statues, and it brings me peace—like big anchors. Humble, happy and strong.”

Parenton’s blueprint for his faux-game extends beyond the Famicase-made cover art. He envisions that players would be able to sit on the Nintendo Power Pad, set a timer, and meditate in any of the game’s seven exotic locales. If it were on display, say at Fantastic Arcade (in the year “2020,” Parenton joked), Island Time would find a home on an old CRT TV, surrounded by a cool themed installation to create a nice, ambient experience.

New York-based comic artist Cassie Freire (writer and artist for Catnip Circle) has also participated in the My Famicase Exhibition for two years. In both instances, Freire’s featured characters from her very own comics, including her entry last year, Doki Doki Delivery, and this year’s Cat Cafe Dessert Panic! (starring the main teal-haired character of Catnip Circle, Pera). On her inspiration for the game, Freire says it was simple, “For a while I would joke about making a Catnip Circle game with friends,” said Freire. “Imagining what kind of game it would be, cutscenes, what the covers would look like, that kind of thing.”

“[My Famicase is] imagination and creativity in its most innocent form”

Cat Cafe Dessert Panic!’s premise is absurd, just as the comic it’s based on is. In it, the player is a human waitress in a cafe for cats, which sounds cute and cuddly, until the cats are hellbent on ruining Pera’s day and making her drop all the desserts. The goal of Freire’s game is not to let that happen, and keep the desserts intact.

Elsewhere, in Los Angeles, multi-year My Famicase Exhibition contributor Grace Voong (also known as Thymine) enjoys the welcoming atmosphere of the annual event, given that anyone can submit a design no matter “where you’re from, or who you are.” Thymine’s dabbled in her own faux-Game Boy carts in the past, and enjoys the tangibility of making a concept come to light through an “obsolete” component. For this year’s submission, the pastel-hued Oyasumi Tomodachi, Thymine took inspiration from a long-forgotten old sketch of a witch. “I’ve also always wanted to make something with a magical girl [or a] witch, and thought [this would] make a cute game,” explained Thymine of her concept. “By the end I decided the game was about friendship, and a little bittersweet, like how some relationships are. I wasn’t thinking about this at the time, but I feel the idea that ‘people come and go all the time’ was a subconscious inspiration.”

The My Famicase Exhibition is home to a variety of artists from around the world, and all their clever, varied ideas for games. Some are humorous, some are dark, some are just plain delightful. As Parenton himself said, “[My Famicase is] imagination and creativity in its most innocent form. No budgets, no revisions, no one can tell you ‘no.’ Just your idea and art to make it come to life.” Whether it’s the meditation of Island Time, the dessert juggling of Cat Cafe Dessert Panic!, or the ever-evaporating friendships of an adorable witch in Oyasumi Tomodachi, My Famicase, year after year, breathes life into the Famicom’s legacy, artists’ creativity, and the games that could and should have been.

You can view all of this year’s My Famicase Exhibition’s faux-games on METEOR’s site . If you’re in Japan, the exhibition will be on display at METEOR until May 31st.

Tron and its lasting vision of cyberspace

This is a preview of an article you can read on our new website dedicated to virtual reality, Versions.

///

Here’s a fair question: How can a bomb from 1982 continue to impact the way we imagine cyberspace?

It’s always grids and neon—synths and geometric shapes. When Homer Simpson found himself in this virtual dimension, surrounded by cones, equations, and clip art, he asked if anyone had ever seen the movie Tron. One by one, the residents of Springfield said “No.”

Released the same year Disney opened up their futurist edutainment EPCOT park, Tron impressed critics but failed to speak to audiences. It wildly underperformed for the investment, costing $17 million and taking in only three million on its opening weekend. According to James B. Stewart’s book DisneyWar (2005), the studio largely considered the project a write-off. Of course, as we now know, the film’s audience grew as it became an 80s cult icon, and computers became more familiar to the general public. Its increasing popularity even encouraged a sequel decades later, the also financially sluggish Tron: Legacy (2010), which brought the original cyberspace vision back into the collective consciousness, or at least tried. But in 1982, Tron was a confusing journey through techno jargon for people who might have only encountered a computer six times a year.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers