Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 133

April 20, 2016

Overland’s post-apocalyptic dioramas arrive early, but only for some

Tactical survival road trip game Overland saw its paid alpha program called “First Access” launch yesterday. This game, the latest from publishing label Finji, is a procedurally generated road-movie-meets-tactical-squad game, set in a series of diorama like scenes.

“First Access” gives paying fans the ability to play the game early, with features like developer forums and constant updates available. The system is also relatively exclusive—there were only 500 keys available for First Access, which used itch.io’s Refinery toolset. More keys will be made available as the game hits internal milestones. It’s the first time Finji, whose previous games include Capsule (2012) and Canabalt (2009), has had a paid alpha program.

“dancing around the same idea of the unknown”

According to Adam Saltsman, director at Finji, it’s actually a series of firsts for the studio: “It’s our first major release since 2012, so the market is drastically different. It’s also the first major “mainstream” PC game we’ve designed. It’s also the first time we’ve tried a paid alpha. It’s the first time that we built from blind hiring instead of just recruiting friends. It’s our first turn-based game. It’s our first release where my partner Bekah’s role has been more public.” It’d also be amiss to not mention that the game’s unique visuals have been at the forefront of the buzz, including the unique website that overlays several different levels from the game.

Saltsman talks about a few esoteric influences—Roadside Picnic (1972) and its loose film adaptation Stalker (1979) among them—but it is best summed up as “kind of dancing around the same idea of the unknown and whether or not that’s scary.” A road-trip into the heart of an unnamed post-apocalyptic scenario, burdened with the management mechanics of survival—groups forced to defend themselves against a tide of creatures, trying to make the correct choices—certainly seems to fit that bill.

Overland can be found on itch.io, and more information can be found on their website. The game is set for a full launch at some point this year on Windows and Mac.

Heart attacks and doggy treats: the PS2’s most bizarre horror game

This article is part of PS2 Week, a full week celebrating the 2000 PlayStation 2 console. To see other articles, go here.

///

On the US release of Dario Argento’s 1977 film Suspiria, New York film critic John Simon panned it as “a horror of a movie, where no one or nothing makes sense: not one plot element, psychological reaction, minor character, piece of dialogue, or ambience.” I used to agree, but I’ve seen Suspiria a lot since then. It’s true that the film’s rather twisted internal logic requires a degree of good faith on the part of the audience; it’s also true that to call it incomprehensible is received wisdom at best.

The film’s protagonist, Suzy Banyon, is a smart woman who manages to unravel the coiled, foreign schemes of witches and devils to emerge victorious. At no point does she do anything stupid—even when she’s falling into a drugged stupor she’s aware of what’s happening to her and who’s doing it. She’s only missing one key piece of information throughout the film, as is so often the case in Argento’s work: once she has that, she’s home free.

I’m not saying Suspiria is spy-thriller tight; I’m saying that to throw your hands up and say it doesn’t make a lick of sense is a failure on your part, not the film’s. Its psychological landscape is exactly as complicated as it needs to be.

Its psychological landscape is exactly as complicated as it needs to be

The same could be said about 2005’s forgotten PS2 survival horror game Haunting Ground. Effectively the fifth entry in Capcom’s long-running Clock Tower series, Haunting Ground (or Demento in Japan; a name that cuts right to the chase) is a game where you play a girl, Fiona Belli, trying to escape a castle and several demented pursuers. Your sole companion in this quest is Hewie, a white German Shepherd and very good boy.

As in Clock Tower 3 (2002), a virtual blueprint for Haunting Ground, you’re largely defenseless against your foes. Fiona can kick and shove, but not much else. It’s Hewie who does the pup’s share of the fighting, so it’s essential to treat him well to ensure he listens to your commands in the heat of the moment. He likes jerky and playing fetch.

There’s a lot of weird stuff going on in Haunting Ground. This ranges from its persistent fixation on alchemy (Fiona has the “azoth,” and everyone wants it) to the underground crypt filled with impassable fire that you can immediately quench using a big golem (he sinks into the ground in front of the fire, which I guess puts it out?), who responds to commands that are stamped onto plates from a nearby plate machine. The commands, by the way, are listed on a memo right smack-dab in the center of the room.

This golem situation raises a lot of questions, like “why spend time creating this area, as a programmer, if there’s literally no challenge to passing it?” and “why create this area at all as someone who designs castles?” But if you follow this thread, how far is too far to stretch one’s credulity? There’s an Escher-meets-Hogwarts hallway of exploded staircases and horizontal suits of armor; there’s a puzzle that involves using magic jars to exorcise a reanimated corpse so you can grab a key from around its neck. Here I defer to Kill Screen’s Gareth Damian Martin on Silent Hill 2, a game whose architecture is symbolic rather than literal, a creative choice central to its psychology. The spaces of Haunting Ground—the castle, a forest, and, inevitably, a mansion—twist and inflate like a Mercator projection.

The mansion has a sensible bathroom, yes, but it also has a three-headed dragon statue that, when plates bearing the names of the three base alchemical elements are placed into its trifold mouths, freezes a nearby column of fire solid to allow Fiona to climb to another floor. These are impressions of places, coherent structures bleeding into a jumbled, half-remembered dream you might have after reading one too many Gothics.

the sheer bold grotesquerie of Haunting Ground allows it to creep under your skin

Like with Suzy in Suspiria, there’s a believable protagonist wandering through this madness. Fiona is a young woman with a possible panic disorder who isn’t cut out for the Jill Valentine role: if Fiona gets too frightened, the screen explodes into saturated monochrome and the game wrests control from the player. You can only direct Fiona’s direction and scream for help as she sprints blindly around, shrieking. She can even die of a heart attack if you’re not quick to get her to safety; a rather morbid back-of-box bullet point.

You have access to Fiona’s internal thoughts via a pause-screen journal, which is automatically filled out at certain points in the game. The entries reflect her naivete, her love for animals, and her revulsion at having to kill. “Why is it always like this?” she asks herself, mournful after defeating a foe.

There’s another line that’s stuck with me, one bit of flavor text among many. “I can lie to myself all I want, but there’s no denying those are human bones,” Fiona says when you examine a glass display case. Her defenses are weakening. The lies aren’t working any more. This is blunt-force verisimilitude. You could call it telling instead of showing, if the game didn’t do both. At no point do you find a gun, or any weapons other than alchemy powder and metal boots. You can feed Hewie a substance to make him go apeshit, but there’s a chance he’ll attack you too. There is always risk involved with an offensive effort—often it’s best to run and hide.

Certainly, as Leigh Alexander argued long ago, the sheer bold grotesquerie of Haunting Ground allows it to creep under your skin. But by removing player agency at critical moments, Haunting Ground commits to Fiona’s subjectivity. The formal elements of the game—sound, image, control—bend to her psychological state, rather than offering clarity to the player. This expressionism reflects the murkier ideas of violation, transgression, and bodily autonomy running through the narrative.

When confronting one pursuer, the castle’s maid Daniella, for the final time, she gives a growling, feverish monologue: “Blood, flesh, woman. You vile creature. You lure the man into your filthy body again and again …”

Daniella’s special hatred for Fiona seems to come from self-loathing; it’s implied that Daniella may be a homunculus, or at least a lifelong captive and alchemical subject. She’s infertile, seemingly unable to feel physical pain, and explicitly abused by another character in one cutscene. Her fingertips are bitten bloody, her palms covered in raw cuts. She can’t stand the sight of herself in mirrors.

by removing player agency at critical moments, Haunting Ground commits to Fiona’s subjectivity

“I am not complete,” she says. The flip side of the deep, lasting grief that comes with dysmorphia is a gnawing envy of other bodies: to see an unattainable self reflected everywhere you look. Daniella covets Fiona, sees in her something she will never be and at her core wants achingly, overwhelmingly more than anything else. Naturally, Haunting Ground ratchets this up to “chasing you with a shard of glass and wants to cut out your womb” levels, but there is truth at the heart of the absurdity.

Not all of the game is so brazen. The most unnerving moments are those in which your captors appear as, if not friends, then neutral parties. If you let one enemy live he begins to think of you as a saintly figure, his desire to twist and snap your limbs subsumed into cartoonish devotion. Daniella is introduced early as a deferential, if odd, servant, but it’s not until later that she snaps and starts hunting you down. Even then, there are rooms where you can walk by her without incident as she cleans. You can solve a puzzle while she kneels by a flaming hearth.

These moments stretch by with unbroken tension. Fiona doesn’t understand the full scope of their plans for her, nor why they suddenly would want to kill her. And so, dear player, neither do you.

April 19, 2016

People have figured out how to get the Steam Controller to sing

The player piano was a big deal in the early 1900s—if you could afford one, you could hear piano music in your home as performed by the machine itself, reading off rolls of punchcards pre-loaded with popular tunes. These early digital music devices fell out of fashion as the analog phonograph reproduced music more accurately and more cheaply. The modern MIDI file is its own sort of punch card, designed to be used with a wide variety of digital instruments. The files are highly compressed, but can produce a fairly accurate rendition of the original song when spit out through the right devices. There’s a relatively popular genre of video where the devices used for midi output are not traditional instruments—perhaps an example of what’s called extended technique, reminiscent of Leroy Anderson’s 1950 piece “The Typewriter.”

haptic feedback in the controller’s trackpads play music

If you can connect the device to a computer and it makes noise, there’s a good chance you can make it play MIDI files. There’s a chorus of eight floppy drives singing Pachelbel’s “Canon in D” and a dot matrix printer that sings “Eye of the Tiger“—very well, I might add, because of its ability to produce (more or less) one note for each of its 24 image-producing pins. As the “Internet of Things” expands, designers and advertisers are working quickly to get to market with a smarter version of every last thing in your house, whether it’s a water bottle or a menstrual cup, and a multitude of possibilities are opening up for repurposing these devices to better fit our needs, whether we need bootleg single-serving coffee capsules or novelty music.

The Steam Controller joins this eclectic ensemble thanks to a French Steam user called Pila, who’s figured out a way to make the haptic feedback in the controller’s trackpads play music. In the Steam Controller, the haptic feedback is produced by linear resonant actuators instead of spinning asymmetrical weights: on each side of the controller, there’s a tiny weight on a spring being fed an electromagnetic pulse that leads it to vibrate up and down. It works a lot like a speaker, but with less precision. As such, the actuators can produce one tone at a time, giving the controller two tracks to work with—a lot of MIDI songs have to be cut down pretty significantly to fit into this restriction, but it still leaves room for a melody and a bass line. Here’s Pila’s interpretation of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” which takes full advantage of the two-track allowance.

Simon Flesser of Simogo tweeted out his Steam Controller singing the theme from Super Mario Bros 2 (1988). It’s not quite as hi-fidelity as the little speaker in the WiiMote, so developers probably can’t use it to communicate secret information, but if anyone can come up with a weird and exciting way to integrate this hack into a game, it’s probably the folks behind DEVICE 6 (2013) and Year Walk (2013).

If you’ve got a Steam Controller on hand and want to give it a try, the GitHub for Pila’s project is here and a Steam guide for getting it set up is here.

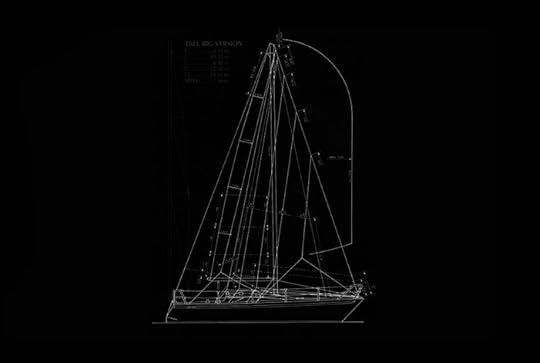

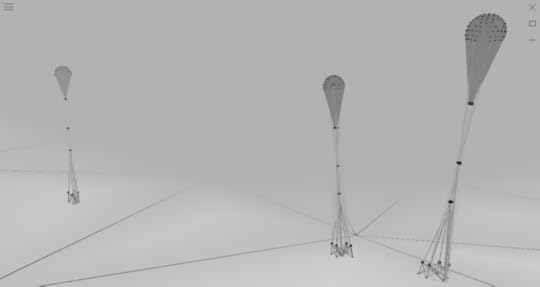

Making games on a boat to get back that feeling of being lost

Rekka Bellum and Devine Lu Linvega (otherwise known as Hundred Rabbits), the creators of Oquonie (2014), a surreal textless puzzle game, and Grimgrains, a blog about being artistically creative with food and color, are pursuing something new—and it involves sailing. Rather than another singular project, the duo’s new venture is a complete lifestyle change, which will inform all the work they do for its duration. They have decided to create a floating, travelling studio. Yes, on their boat home, they will seek to create games, experiment with food, and adapt to living at sea.

Support for the project went live on Patreon at the end of last year to help fund their journey, which started mid-January. The idea is that each month they post a video documenting their travels and experiences. Each video entry ends with a thanks for keeping them afloat “literally.” For $15 a month, you can get access to playtests and receive download codes for their projects as they are released. There’s no specified length of the journey except for the fact that they plan to keep it going up until the winter—so at least for a year. Though the idea is that they are committing themselves to a new way of life. As they say in their first video, after they had lived abroad for a while, they asked “What do we do now? Where do we go? Do we move again? And the answer was, yes, we move again, and we’re going to live on a boat”.

Each video entry ends with a thanks for keeping them afloat “literally”

My high school self can’t help but add the sound of Lonely Island any time “on a boat” is a relevant thing to say, whether I like it or not—though, the fact that Google seems to agree makes me feel a bit better about this. However, the sounds of Hundred Rabbit’s adventures are far more minimalistic, and ambient. Each episode of their journey has a different sound, especially created for that log entry. The somehow slightly creepy, and yet also comforting sounds, feel apt for the hues of blue-grey ocean, and mixed feelings of nervousness and excitement, which surround them.

Hundred Rabbits expresses the want to feel lost again. For them, the need to make sense of things from this feeling is a liberating creative experience, and as they say “Going to new places kept us creative, and we decided then that this the kind of life we want for ourselves.” Their journey and ideas of travel and the uncertainty which comes along with it, ring with a sense of J. R. R. Tolkien’s famous line, “not all those who wander are lost.” Their deliberate minimalism and wandering not only make for great watching but should also provide us with some great projects to come.

You can support Hundred Rabbits on their Patreon, and keep track of their journey through YouTube and Twitter

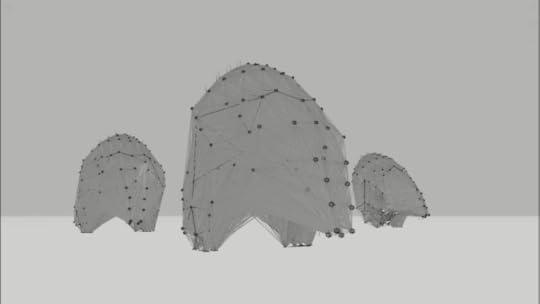

Videogame lets you command neural networks to manipulate evolution

“It took 4400 million years for the first life to appear on Earth,” is the opening line to the website for HOUND, a recently announced game project by its 18-year-old solo creator, Nikita Shesterin. And if, on reading that, you just thought, “hang on… that’s not right,” then Shesterin believes you’re the right audience for his game.

HOUND hands you a universe replete with evolving creatures and ecosystem, and then gives you the controls to fiddle. You can create a physical model, perhaps of something as simple as bacteria, and then watch it evolve into a variety of new species—billions of years of evolution in a matter of minutes. An easy comparison would be with Millennium Interactive’s artificial life videogame series, Creatures, though Liam Esler, who managed Creatures’ community and was involved in its modding scene, thinks this a false comparison. “As much as Creatures is about the science, the series was much more about empathy and relationships—creating a bond between player and artificial life, exploring the idea of what it means to be ‘alive’,” he says.

create things that no one has seen before

HOUND‘s is an eerie, minimalist world filled with Karl Sims-esque creatures scampering and flapping beautifully through the environment before something with a mouth inevitably swoops in to extract their resources. This is a world for players who like to explore the boundaries of systems, and to create things that no one has seen before. Speaking of Karl Sims, who used evolutionary algorithms to generate walking and swimming movements for arbitrary shapes, his work was “an initial inspiration” for Shesterin: “[his work showed] that what I was starting had successful analogs and was technically possible.”

Simulating a universe might sound an ambitious project, especially given that this is his first videogame, but Shesterin describes it as inevitable; “all of it started small, with a simple self-learning robot that was supposed to analyze the environment and develop new systems of walking,” he says. “At that point I knew almost nothing about artificial intelligence and had only basic programming knowledge, but I had lots of ideas. From that moment I started to add new things, to test those ideas and learn in turn.”

Those ideas extend even beyond the game. HOUND is a small chunk of a larger project, the goals of which Shesterin remains coy about. “[Not wanting to be] too vague, it is intended to develop a neural network of high organization which will be able to efficiently improve itself,” he sort-of explains. “For now, I am focused on building a foundation for future research.”

A free PC demo of HOUND is available now. It is purely a sandbox demonstration of the game’s systems, though Shesterin talks of adding game mechanics for the final release aimed for September. “If it sticks, and becomes popular, I well expand it to a full campaign mode,” he says. If everything does go to plan for Shesterin, who finished high school early and is hoping to generate money from the game’s sales to fund college, an Indiegogo campaign for HOUND will be launched in mid-May.

You can find out more about HOUND on its official website.

A landscape of memory; returning to Shadow of the Colossus

This article is part of PS2 Week, a full week celebrating the 2000 PlayStation 2 console. To see other articles, go here.

///

It’s hard to calculate the distance from the clifftop to the sea below. My body, my eyes, the trembling in my legs tells me it is far, too far. Yet I can make out the marbling of the dark water as the foam traces fractal patterns after every impact. The white spray flash-bulb frozen against grey stone. The glassy shapes traced by swirling currents. These details feel close, painfully close. Perhaps it is the rhythm, the yawning in and out that closes the distance. Or the complexity, the hypnotic pattern of wave impact and tidal draw. Either way, it is a connection that is felt, both in the sharp edges of the wind and the distant roar of the breakers. To me, it’s a familiar connection, one so atomized into the structures of my mind that if it were to disappear from the world I could rebuild it entirely, piece by piece, until it felt right.

Yet this clifftop, this sea, doesn’t feel right. There is wind, at least a fallacy of wind, and there is the sound of distant waves, but the connection is off, absent. The visceral feeling of standing both on the clifftop, and imagining yourself buffeted by the waves below is somehow missing, the mysterious ingredients of its make-up out of reach. There is a lightness to everything, an impermanence, as if all the tensions could be reconciled in a moment, like crumpled paper suddenly folded into neat squares. It is an unfair comparison, of course, this limited digital world held against the unlimited pathos of memory. But, like the waves and the clifftop, the connection is there.

In memory everything is virtual

I am speaking of my own memories and the image on the screen in front of me. The image is from Shadow of the Colossus (2005): A young man stood on a clifftop, looking down at the sea below. This image is defined by its feeling of fragmentation, incompleteness. Key pieces of information are missing, unable to be represented in this limited visual space. The temperature, the texture, the smell of the image are all absent, all fragmented. My memory of the clifftop is the same; missing pieces that have slipped away, details and complexities lost to time and perception. I have stood on many clifftops, and watched countless waves break, and so when I recall the feeling, the connection, I am recalling a tapestry. My mind is filling in gaps with variations of that same memory, ones both distant and recent. And then it is also adding fabrications, songs, films, games, paintings, poems; each one a fragment that might make up a whole. The experiences blend easily, parts of each switching places like shuffled cards. In memory everything is virtual—there is no distinction between the digital and the analog, the played and the lived. I recall something I once read from an interview with William Gibson: “On the most basic level, computers in my books are simply a metaphor for human memory: I’m interested in the hows and whys of memory, the ways it defines who and what we are, in how easily memory is subject to revision.”

///

Just off the Northernmost coast of Scotland are a group of islands. Scattered into the sea like a handful of stones, they stretch away from the mainland towards the great pole beyond. Some of them are low and flat, almost barren. Others are protected by high cliffs, where the waves crash in a powerful chorus. These islands, despite the hostility of their climate—their treeless hills and stormy seas—have been home to people for eight and a half thousand years. The remains of these people can be found all across their rich peat fields. Not in the physical form of bones and corpses, but in the heavy stone structures they left behind. Stone circles mark lands of unknown significance, villages sunk into the soil conceal themselves from ancient winds and humped burial mounds house the dead. It was on these islands that I grew up. I played in the ancient homes of long dead farmers, looped in and out of stone circles on wayward paths, and climbed down long dark passages to reach the resting places of the dead. I clearly remember the emptiness of the burial mound at Maes Howe, a place where, on the winter solstice each year, the weak yellow sun shines down the entryway to light a set of carvings on the far wall of the tomb. I ran my fingers across that wall, feeling the stone cut by the neolithic peoples of the island, crisscrossed by the runic graffiti that invading vikings had added many centuries later. There were no corpses, there was no blood, but the dead were all around me, close enough to touch.

Shadow of the Colossus is filled with fictional proof of a long passed human presence. Though the central tower of Dormin’s shrine suggests that this land is a holy place, not a home, the map is scattered with broken halls, fallen towers, lonely arches. The scale is monumental, but there is something distinctly human about this trail of ancient evidence. Perhaps there is nothing more humanizing than death. Even the Pyramids of Giza, those vast monuments to belief in human immortality, have an aura of grief hanging over them, one of the deeply personal experience of loss and losing. A tomb is a powerfully different space to a grand shrine or cathedral, though they often occupy the same land. The latter demands you look upward, to salvation, omnipotence, and the continuation of the spirit. But a tomb will only ever lead your eyes to the ground. It doesn’t matter if tombs themselves might preach reincarnation, or the paradise of heaven, they are still unable to escape the earthiness of death. Decomposition has no theology. The structures of Shadow of the Colossus are memento mori; moments of remembrance that the ground you tread might hold the bodies of those who were once in your place.

However, the game never shows its dead, never exhumes their bodies. Even in the most tomb-like parts of its architecture, simple carvings are the only detail to be found, along with a distinct sense of emptiness. Where are the bodies? Where are the skeletons? Or even the caskets and the mortsafes? Throughout the entirety of Shadow of the Colossus you will not encounter a single dead body, skeleton, or corpse. You will never follow a blood trail, or find signs of a struggle splattered across the walls of some dark corridor. Despite this, death is everywhere. It lies on open wastelands stripped bare by the wind, among the piled stones of distant shrines, and concealed in the darkest corners of long forgotten edifices. It’s one of the many design decisions that makes the game a true rarity. When games wish to tell a story, they reach straight for the bodies. They liberally scatter them in steely science-fiction corridors, line them up along brick walls. They float them in sewers and stack them in dumpsters. They leave them slumped on desks like executive toys, their blood pooling out of the shiny surface. In games, corpses are a meaningless literalization of death. They are used as symbolic assets, ready to communicate the imminent arrival of some fearsome enemy or terrifying monster. In short, they are furniture. Which is why Shadow of the Colossus doesn’t contain any. No corpses, no ancient sofas or chairs, no rusted tools or rotting barrels. No beds and no bunks, no coffins and no caskets. There is no need for such decoration: This landscape is a tomb.

In games corpses are a meaningless literalization of death

///

I pick up the controller and walk the young man down the long sloping path to the base of the cliff. There I am drawn to the waves. There is an expanse of beach all around, ominous in its scale. There will be a battle here, I know that already, but I want to preserve this moment a little longer. I make him run out across the beach, so flat and grey and dry, like no beach I have ever walked on. The light descending seems dusty with age, a strange thought in this world with no true history of its own. He reaches the breaking waves, rolling onto the beach in an unnervingly even pattern. The sound is wrong, disconnected. I can hear the lapping of a placid sea, calm and even, and yet I am faced with waves as high as a man, riding up out of the sea with a constant force. I walk the young man along the edge of the water, struggling to resolve this disconnection between sound and image. I want a sound that can drown out everything else, a crashing, roaring sea eroding this world into oblivion. A sound that breaks the cliffs down and carries the pieces off to another shore. Instead, the insipid sound of a toe-lapping tourist beach trembles through the speakers. I hit mute, preferring silence. Then, in a sudden movement, as if this is what I had planned to do all along, I run headlong into the waves.

As I do this I remember something. But it can’t be a real memory—it’s impossible. The sea was too cold, the waves too strong. It would have been idiotic, suicidal even, to dive into their depths. It was possible to swim in the summer, sure, when the island’s waves were low lapping contours, approaching the land one by one. But no, the way I remember it, these waves were breakers, walls of foam straight off the North Sea, blown by Arctic winds. They were winter waves, sharp and biting, and my brothers and I walked out into them. We were rolled over by them, drenched, dragged and then we came back up for air. We plunged into them, cartwheeling into the foam laughing, and returning to the surface gasping. I can still feel the icy cold, the weight of the water, the salt, the sand—all crystallized. Yet it never happened. It is a crude, hacked-together dream, built of the wave dodging we did as children along the North Sea coast, and the joy of throwing ourselves deep into other, warmer waters, on softer, southern beaches. That doesn’t stop me remembering it though, as a single memory, powerful and exhilarating in each recurrence.

I turn back to the screen—to Shadow of The Colossus and the young man running into the waves. The image is comical: The young man is turned on his head by an unnaturally silent, unnaturally smooth wave. He is rolled back up the beach, and deposited unceremoniously on the sand. I try again, running forward the moment he has regained his feet. He is caught earlier this time, and is pushed back, turned around and left lying on the sand again. His horse trots up the beach and rears up, as if confused by his master’s idiocy. I send the young man into the waves once more, choosing my moment this time, a gap between tides. He runs into the water until the current holds him in place, he braces against it, legs spread wide and arms out. It holds him there until the next wave slides silently in and flips him over, bouncing him on his head for good measure this time. I take this as a challenge: It’s a game now, I think, and I run at the water again.

It was a game then, too, a game of staying dry in a world of wet. As the North Sea rolled in we would run across white sand beaches, voices taken by the wind. As each wave drew the water back, rattling pebbles in the wash, we would surge forward, filling the space on the drying sand. And then, as the breaker hovered and plunged, we would stay as long as we could before jumping out of the way, jostling and pushing each other into the sea’s path. There was a dog too, sprinting back and forth behind us, barking at the excitement of three brothers. The madness of that ragged creature far outstrips the uneven programming of the young man’s horse—its digital analog—in Shadow of the Colossus, and yet perhaps these are the two elements that feel closest of all. Both are distant flickers at the edge of the memory, comical side characters that charge through on trajectories of their own—unknown and unknowable.

I hit mute, preferring silence

///

To me, the landscape of Shadow of the Colossus will always have associations with the city of Stirling. It was there I spent a summer living with a friend, wandering the expanses of its wind-scoured world in an almost aimless fashion. I had played the game before, but it was over the course of those summer evenings, worn out from menial work, that I would slump down into my seat and ride out between the stone bluffs for no other reason than to be somewhere else. We would trade secrets, discuss theories, and nights would stretch on as we hunted lizards with the playfulness of children, firing arrows just to watch how they flew. We played the game on a large flatscreen TV in the rented flat, a perk clearly designed to bring in students, of which there are many in Stirling. It was a cheap and ugly thing, sub-HD, and smeared the image at the slightest movement, turning Shadow of the Colossus’ already bleached look into an impressionistic smudge. Even if this wasn’t the case, the landscape of Shadow of the Colossus was broken, perhaps even ugly. Its simple geometry and muddy texturing was less than convincing, and the stone features that rise from it had the unnerving of habit of changing shape or jumping entirely into existence from nothing as we approached them.

It is perhaps because of this that I remember the game’s landscapes so richly. In the spaces left by the smears and the bloom I inserted detail, invented texture. However, even in their crude form, these landscapes have a particular quality. Though their fidelity is limited, the modeling and shaping of their cliffs and bluffs, scree slopes, and erratic boulders rings true. It is exaggerated, sure, with sea cliffs higher than any in existence and huge stone escarpments rising like skyscrapers, but it feels right. For someone who had spent a childhood in the often powerfully dramatic lands of Northern Scotland, there was a truth in the topography of the game, a sense of shape and form that was instantly familiar. The game’s yawning valleys and round stone hills brought to mind the slopes on either side of the saddle-backed mountain Suilven, found in the far North-East of Scotland. And the game’s Southern coastline brought back memories of exploring the Quiraing, an almost alien landslip on the Isle of Skye. These memories felt almost freely accessible to me as I rode across the game’s “Forbidden Land”, imbued, as they were, in the landscape around me. In those moments of escape in that Stirling flat, I was attempting to walk back into my memories. It’s a delicate act, identifying what it is in the game’s landscape that so profoundly triggered these associations, but perhaps it comes down to the process of erosion.

The landscape of Shadow of the Colossus was different once. Of its 100 squares of map, only 16 have Colossi to discover and defeat. However, when the game was first planned, its director Fumito Ueda wanted 24 of the beasts to find and slay. As has been obsessively cataloged by what is a tireless fanbase, the game’s landscape possess many traces of this original design. Ruins, landforms, and arenas all remain from the missing eight giants. The game’s “Save Shrines”, which barely serve a purpose, are sometimes obscurely positioned, and discovering them all becomes a task in itself. The result is a landscape of distinct purposelessness, one where seemingly meaningful or important forms lie everywhere, their context and explicit use lost to time. This genuine ambiguity mixes inseparably with the game’s own sense of history and atmosphere, its crumbling ruins and lost temples, to create a sense of emptiness comparable to that of the standing stones and burial mounds I played among during my childhood. In those days they were often unmarked, and without a guide or a placard displaying historical context, the stone symbols were left unexplained, to play across my mind, as mysterious as the missing colossi.

This is what makes Shadow of the Colossus world an eroded one. Its carefully modeled landforms are precise studies of the effect of weather and time on earth and stone. Its map is shaped by game design decisions lost but not corrected. Its broad visual strokes and bleached colors are the perfect canvas for the slow decay of memory, detail creeping silently in long after the console has been turned off. It feels like an impossibly rich realm of memory, a real place, and yet each time the disc is put in the console it reveals itself to be disappointingly fake. Its dysfunctions and glitches are all too present, its half-finished aspects so noticeable. The 2011 HD remake only compounds the problem; its jagged edges and sharpened textures blasting away any of the remaining softness the game might possess. The internet is filled with 1080p images taken from this game, or pin-sharp shots taken from PC emulators. Both feel like flash photographs of past events, all too revealing in their white acrid light. Now, after all these years, I cannot return to the way it was on that smeary screen in that unremarkable flat. It has eroded too far, and what has filled the cracks scored by time is too strong to be carved out.

Its broad visual strokes and bleached colors are the perfect canvas for the slow decay of memory

///

I let go of the thumbstick. After a moment, I draw the young man back from the edge of the sea, suddenly feeling ridiculous. In this moment the distance between the memory of dodging waves and the process of guiding this digital avatar again and again into a contrived barrier feels the most distant. The connection has been dropped somehow, the distance once again too great. There is a task to be completed, an enemy to be slain. In the context of this vast endeavor, the boyish silliness of running repeatedly into the waves suddenly loses its weight, becomes futile. I guide the young man back up the beach, toward a vast cave mouth that is set into the cliff face. I sharpen my mind, and prepare myself for combat.

Early into the battle, once I have scaled one of the giant’s vast four legs and found purchase at its shoulder, I notice what is missing. Music. Grand orchestral music, the kind befitting a battle of this scale and scope. I realize I muted the sound during my wave-dodging and never turned it back on. I reach for the remote to restore the epic score, and then stop. I suddenly notice the direction in which the colossus is headed. I swing the camera around to confirm it, yes, he’s headed straight towards the sea.

Without the music pushing me on to make the kill, to defeat the great beast, a calmness suddenly takes over. I haul the young man up onto the rocky spine of the creature, and perch there to get a better view. The colossus plods across the sand, almost reaching the waves. I look back, and see the young man’s horse patiently following behind, trotting in the footsteps of this gigantic beast. It is a bizarre procession towards the sea, this vast beast, ridden by its fragile rider, followed by a skittish horse. The colossus strides out into the waves, its huge hooves hammering into the sea. It drives forward and then suddenly stops. It paws ineffectually at the ground; held in its place by the current. Across the other side of the inlet I see a bird, skirting the clifftop effortlessly. The great beast takes a few more steps into the sea, but the futility of its movement is clear. It turns awkwardly on the spot and then stomps up the beach, still carrying the young man, his horse close behind.

When I strike the final blow, driving the young man’s sword into the beast’s head, the sound is still muted. The creature falls silently to the ground, reeling over its front legs and slamming into the beach. I drop off its back and begin running. I don’t even come close to reaching the waves before the black tentacles find me—those shadowy limbs that burst from every fallen colossus. The young man falls to the sand as the tentacles pass through his body, and the image begins to fade. I scramble for the mute button, suddenly wanting to hear the waves before I leave—but I am too late. All I am left with are a handful of whispers, hissing over the speakers like empty noise.

I return to the beach later. The beast’s corpse is barely recognizable, fused with stone and covered in sand. All over it tufts of grass grow, as if it had been lying there for decades, perhaps centuries. I stand and look at it for a while, try to climb it, and then give up. Before I leave the beach I run into the sea one last time, knowing what will happen, but hoping that somehow this time it will be different—that this time I might break through the barrier and reach something new and yet known, just beyond the waves.

Hilarious new game gives yoga the QWOP treatment

Released over the weekend as part of the Ludum Dare game jam, Jenny Jiao Hsia’s Wobble Yoga may be the most honest exercise game you’ve ever played. Well, aside from her other yoga game, that is. There’s no fireball-throwing aerobics instructors here, nor are there any claims that you’ll leave the experience healthier than when you came. Rather, all Wobble Yoga has to offer is a challenge, a keyboard, and shame.

The game has you taking on the role of a balding, out-of-shape man as he tries to recreate various totally-not-made-up yoga poses by matching up with a silhouette behind him, failing more often than he succeeds. Unlike Hsia’s last yoga game, which has a similar conceit, there is no time limit this time around, but the tradeoff is that our hero—let’s call him Wobble Man—has more points of articulation than in her previous project. There are a total of nine buttons, each of which controls one of Wobble Man’s joints, similar to running game QWOP (2008), and it’s your job to use them to try to get Wobble Man into tip-top “tired pretzel” and “salted baby” shape.

more failed chicken dance than Saturday Night Fever

The result is more failed chicken dance than Saturday Night Fever (1977), though, as it quickly becomes apparent that trying to get Wobble Man’s Jell-O-like body to match whatever pose you’re assigned is somewhat like trying to herd cats. His body parts just do not want to listen, and he moves like a dancer that’s half-forgotten his choreography and is trying to figure it out on the fly by copying his neighbors. Also, if you lift him up by his feet, he apparently has anti-gravity powers ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

All of which is to say that Hsia’s take on yoga feels more authentic than any sales pitch about health or improved memory ever could. I’m not sure I know how to balance chakra levels, but I definitely know how to flail about until I fall, sweaty and laughing, onto the floor.

The theme for this Spring’s Ludum Dare was “Shapeshift.” You can check out Wobble Yoga over on Hsia’s itch.io, and learn more about Ludum Dare over on it’s website.

PlayStation 2, the videogame console from outer space

This article is part of PS2 Week, a full week celebrating the 2000 PlayStation 2 console. To see other articles, go here.

///

What makes a videogame console successful? Forget about software libraries and units sold, I’m talking about the design of the actual box that you hook up to your TV. At first blush, the Nintendo GameCube seems pretty notable. It’s downright adorable with its purple color scheme, cute miniDVD discs, and stout, blocky profile—and let’s not forget the notorious handle on the back to be used for carrying the console around like a Playskool oil lantern. The GameCube iterates on console design aesthetics, maintaining the toy-like physicality that Nintendo had previously capitalized on with more tactile cartridge-based game formats (NES, SNES, N64)—sensibilities that they would go on to deliver exclusively through the Wii and Wii U controllers. However, while unique, the GameCube’s design symbolized Nintendo at an impasse. Like a cartoon plopped into the real world, the GameCube was endearing, but its prospects flat and impractical. On the other hand, the GameCube’s contemporary, Sony’s PlayStation 2 (PS2), not only signalled a significant market explosion in videogame console popularity, but did so by merging its technical versatility with slick, referential aesthetic conceits.

The PS2 isn’t toy-like at all, though it is the closest you’ll get to an action figure of the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The console comprises two thick, black rectangles (the smaller of the two acting as the base) stacked on top of one another, or if you prefer, side-by-side as the machine functions both horizontally or vertically. On the topside is a thin electric blue “PS2” logo composed of one single, non-overlapping line per letter, bending only at 90-degree angles, as if prisms were refracting a laser, and allowing negative space to do the heavy lifting. The console’s base is mostly surrounded in humming ventilation slots. The top form contains the automated disc tray, controller ports, and memory card slots, and is outlined by a stack of squared-off ridges and recesses that grant the console an architectural feel, as if each layer was a tiny balcony for gazing out upon your living room floor.

it is the closest you’ll get to an action figure of the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey

Functionally, the PS2 was made to be versatile. Sony used it to lead the charge for game consoles to be more than just machines that can play videogames, serving instead as all-in-one entertainment hubs. In addition to playing PS2 games, the console could play original PlayStation games, music CDs, and perhaps most importantly, DVD movies (this was the year 2000 after all). In a sense, the PS2 aspired to implement more PC-like capabilities while remaining a television-based living room device, not daring to encroach on the office desktop. As a result, the console’s appearance has more in common with a VCR, or other audiovisual boxes of the time, than it’s gray PlayStation predecessor.

While Sony master designer Teiyu Goto has had much to say about his iconic PlayStation controller design, there is far less on the record about his creative thinking behind the PS2’s aesthetic. We know that the option to situate the console vertically was partially a practical response to spatial concerns in smaller Japanese homes, but other elements had a global audience in mind. “The most difficult challenge to overcome was to give (the PS2) a design that would be popular all over the world,” Goto said in 1999. He went on to explain that the thin blue logo on the large black background was meant to symbolize our watery Earth as a small entity surrounded by the vast darkness of space. This cosmic design is meant to be literally universal in application. Perhaps the Kubrickian connotations are no mere coincidence.

It’s no secret nowadays that the shape of the PS2 is highly derived from the unreleased Atari Falcon 030 MicroBox computer. Sony even cites the Falcon in its PS2 US patent filing. Both have similar form factors and incorporate the stacked double-box design and ridged “grill” pattern, and both could be oriented vertically or horizontally. It’s ironic that Atari abandoned the Falcon line of products in 1993 to focus on the ill-fated Jaguar videogame console, only to have Sony pick up the successful design elements of the MicroBox seven years later, using it to begin steering the console industry in a more PC-like direction. Testament to this, the PS2 harbored a bunch of office desktop migrants, such as USB ports and an expansion bay for an optional hard disk drive, plus an Ethernet adapter for connecting to *gasp* the internet. These sensibilities reflect upon the console’s design itself. The possible vertical orientation of the PS2 (rotatable logo and all) isn’t mere happenstance—the PS2 was on the frontier of making people more comfortable with the physical presence of a PC tower-like structure in a leisure environment.

Another of the PS2’s steps away from toy aesthetics was toward architecture, particularly Brutalist structures referenced in cyberpunk science-fiction stories. The PS2 doesn’t just stand next to your television, it looms. The console’s ridged grill is its defining physical characteristic, and though stark and unsubtle, it’s rich with visual reference. Looking to a classic cyberpunk film like Blade Runner (1982), the PS2 would fit right in as a model for one of the dystopian Los Angeles skyscrapers. Flat, windowless, and dark; as is the perpetual night of most cyberpunk settings. The slotted ridges cut into the ground like the teeth on an excavator blade. Pivoted horizontally, they become scanlines from interlaced images projected large scale, or the slats of shadows cast through film noir windowpanes. A giant fan spins ominously on the backside, like the entrance to the anonymous Men In Black (1997) operations facility.

Flat, windowless, and dark; as is the perpetual night of most cyberpunk settings

Yet, even with this emphasis on high-minded design, the PS2’s contours are practical—the system needs to be housed in a box, and the PS2 never pretends it’s anything but a box. There’s a blunt honesty in Brutalist architecture, and the PS2 feels likewise designed around its functional necessities, much the way an office building needs its requisite elevator shafts, bathrooms, and stairwells. Despite the PS2’s harsh exterior, it’s quite user-friendly. When horizontal, its flat top allows you to stack other electronics or accessories on top of it. While the PS2 itself is a sizeable object, its shape is more akin to a modular puzzle piece than some prized totem to be gawked at or fiddled with.

And if the PS2 has a reputation for smart, practical design, the compact PS2 Slimline model is that same set of sensibilities condensed into their purest form. Maintaining most of the original PS2’s functionality, the PS2 Slim (available in silver) is like one of those solid tungsten KILO cubes, if they were cheaper and could also play videogames. Literally quarter the bulk of the fat PS2, the Slim is the size and shape of a relatively scant novel. Put as many handles on the GameCube as you want, videogame consoles don’t get more easily transportable than the PS2 Slim. On late model Slims you can even use the same power and AV output cables between PS1, 2, and 3 (PS4 went HDMI-only, but the power cord is still the same), which makes console swapping a breeze.

It’s unfortunate that the next generation of consoles (Sony’s PlayStation 3 and Microsoft’s Xbox 360) took so many design cues from the bloated Aggro Crag trophy that was the original Xbox, but they did likewise aspire to be more computer-like (or computer-lite?) entertainment hubs a la the PS2. It wasn’t until the Xbox One and particularly the PlayStation 4 debuted in 2013 that the appeal of the PS2’s design came back in vogue. The PS4 went so far as to re-adopt the blue laser color scheme and black monolith profile, tweaking the edges of the console to form a no-less-imposing parallelogram profile to match the hulking rectangle of yore. It’s worth reiterating that, though the PS2 signaled a shift for consoles away from being exclusively game machines, it did so not at the expense of its design, but as the driving focus of a universal aesthetic.

April 18, 2016

Gross digital animation brings Bosch’s painting of Hell to life

Late medieval painter Hieronymus Bosch is known for highly-detailed, nightmarish paintings so fantastical that the Surrealists, including Salvador Dali, found inspiration in them. And it so happens that Bosch’s unique brand of grossness continues to inspire future generations. As the 500th anniversary of Bosch’s death approaches, artists are using today’s technology to create their own modern interpretations of Bosch’s famous large-scale triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (1510-15).

Using the Unity game engine, Kaayk specifically recreated the left panel of the triptych as a monochromatic, 3D animated computer simulation. The right panel, if you didn’t know, depicts Hell in all its awful glory, where sinners are impaled by a horde of creatures so vast that the painting needs its own bestiary. And so, if you look carefully enough at Kaayk’s work, you may find demons calmly performing their daily duties of torture and the like. You can also hear the faint howl of wind and muffled screams far into the distance, and the camera pans to ensure you see Hell at every horrible angle.

Perhaps the best part of Bosch’s style is its sheer absurdity and it’s that comes across in Kaayk’s interpretation of it. Animating each of the creatures and their acts of depravity as one wholly inglorious diorama seems to writhe in its own debauchery. It has me fascinated as does the original painting. My personal favorite image from Bosch’s Hell is that of a large knife cradled by two giant ears; the weirdest phallic symbolism I have ever come across. It’s struck a debate between scholars that has ensued for decades, undecided on whether Bosch was depicting a world overcome by its own sins and moral chaos, or a world reveling in Bohemian eroticism denied to it by the Catholic Church of the 20th century.

a world overcome by its own sins and moral chaos

Given that there are so many tiny details in The Garden of Earthly Delights it’s worth seeing in its full-sized glory in The Prado Museum in Madrid. However, if you can’t whisk yourself to Madrid then you can undergo a virtual tour of the painting from the comfort of your home. It’s an experience deepened by the tour’s ominous, haunting music and narrator (and English author) Redmond O’Hanlon knowledgeable uncovering of the painting’s endless symbolism, history, and double entendres.

You can watch Kaayk’s video on Vimeo and go on the virtual tour in your browser.

Upcoming album will use videogame worlds instead of lyrics to tell its story

Perfect is not something its creator, Sean HTCH, would call a ‘game.’ In fact, he says it’s better described as software that has “elements of 2D exploration games, web browsers, music albums, and nonfiction interviews.” Ironically, the game’s name and its setting are almost at odds with each other. The world of Perfect is actually a city-sized building that was once a “big box warehouse store” known as “Perfect Mart;” think the natural progression from Target, to a Super Target, and so on.

In this imagined future, people live within Perfect Mart, and other buildings like it, because the outside world has been ruined by global warming. Seasons no longer progress and change the way they once did, and nature has ceased to produce food and other natural products of agriculture. That said, life inside the building is about as normal as can be, with the inevitable food shortage being solved by the combined uses of automation and science. People now work as “artists,” creating things like music and paintings, which are then used by “creators” that utilize machine learning algorithms to create machine-assisted art.

The player will explore the world of Perfect and come across Song Modules that, along with other background music, comprise the game’s album. And while listening to those songs, interviews related to them will appear in text form, not only adding more context and depth to each song, but also providing a better understanding of the game’s setting.

“to ‘ground’ the music in concrete world-building and thematic ideas”

A previous version of Perfect had the songs playing in a random order, but was ultimately removed in favor of letting the player discover the songs on their own; either by finding them in the world or triggering them when they enter a new area. For example, one song called ‘Exterior’ will play while in the exterior area of Perfect, with the accompanying interview being with the person in charge of maintaining that very space.

Ideally, players will interact with the game in the same way they do a website, i.e. clicking links to get from one page (in this case, an area) to another. Sean wants the game to be easy to experience, so those familiar with games and those not can enjoy it alike. But that then begs the question: Why even add game-elements like navigation to begin with if its implementation could be intimidating to some? “To help with the pacing of the music, and to contextualize the world,” HTCH explains. “This gives breathers between songs/interviews, and allows Perfect to provide a sort of mood context for each song.”

HTCH set out to make Perfect because he wants to offer a way to engage with music that’s different from simply playing an album, or listening to random songs on the radio. In those scenarios, it’s up to the song and its lyrics (if it has any) to convey a story or a message. Perfect’s goal, however, is to give context to music using narrative and visuals. “By being sort of controlling, overly structuring someone’s engagement with the album [through the use of the game’s interface], I think I can create a way of listening to music that has some of the interesting aspects that games have, while also being able to ‘ground’ the music in concrete world-building and thematic ideas.”

Development on Perfect began in February 2016, and about 10 songs have been worked on so far, with the full game to have between 20 and 30 tracks. You can listen to a few of the works-in-progress on HTCH’s SoundCloud page. Perfect is Sean’s fourth musical project, following the Anodyne (2013) OST, Model Minority No More, and his other in development game, Even the Ocean, which is currently set to release later this year.

You can find out more about Perfect on its website.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers