Summer Kinard's Blog, page 5

December 13, 2020

ABCs of Our Autistic Home: AAC Part 1

Autistic thriving requires household supports and arrangements that remove handicaps. I’m working on a book called Our Autistic Home (coming soon from Park End Books) that shares insights from our all-autistic household to help other families with autistic members to thrive. To support and expand upon the book, I’m releasing videos on my YouTube channel. (See the first video in the series HERE.)

Today’s video is a practical introduction to AAC, augmentative and alternative communication, with tips you can apply right away. I’ll do another video talking about how AAC can be used as a full language/communication system, but this intro shows ideas that can help almost immediately.

WATCH TODAY’S VIDEO and subscribe to my channel so you won’t miss the other videos in the series.

Resources for Today’s Introduction to AAC:

8 second recordable buttons (Amazon affiliate link)

20 second recordable button (Amazon affiliate link)

80 second recordable button (Amazon affiliate link)

Command picture hanging strips (Amazon affiliate link)

FIRST/THEN Adjustable Schedule Printable PDF

The post ABCs of Our Autistic Home: AAC Part 1 appeared first on Summer Kinard.

October 10, 2020

The Biggest Gifts the Orthodox Church Gives Autistic People Like Me

When I was a teenager, I went to a legalistic Baptist Bible Fellowship church that generously picked me up each Sunday in their van. To me, the legalism was refreshing. My family life was chaotic, and I had a hard time knowing what was expected of me. As an autistic child and teen, I was overwhelmed by the layers of emotions and choices that I experienced that other people seemed to filter out. To my extra-complex mind, legalistic expectations were a relief. Explicit teachings on how to behave that other teens might have found stifling gave me an external filter for my decision making that I had not yet developed internally at that time. They told me to read the Bible, so I did. They told me not to do ___ and to do ___, and I thrived. I would never have overcome the shame that came with the abuse I had experienced without that legalistic framework that told me that God had bound Himself to His word. He said He would have mercy and not put me to shame, so I believed Him, even though my trauma shamed me and my autism made every part of life more intense.

While I’m grateful for the kind people in that church who welcomed me and taught me and said that Jesus loved me when I felt the most unlovable, I did not stay long in that branch of the faith once I had other options. In college, I was captivated by the mercy and grace of God that I found in the United Methodist Church, which brought me through great healing and grief and through my Methodist clergy professors into the study of patristics. It was Methodist Christians who taught me about Theosis and virtues and mercy and the imago Dei. I learned about icons first from that renowned Methodist theologian Geoffrey Wainwright. After his seminar on the Theology of Icons, I started praying with icons.

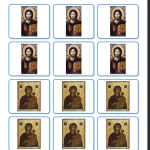

My husband and I soon felt the draw to the East, and we joined the Episcopal Church of the Holy Family, which at the time leaned heavily towards the Eastern influences on the liturgy and prayer life in the BCP. That church was the first one we had joined that had an icon in the Narthex. We lit candles before the Holy Virgin every week. (Now they have a festal icon, too. Many lovely friends are still there.) We delved into liturgical life, praying the hours, singing Compline every night in our home, doing the Stations of the Cross and silent meals with readings from the Tradition on Fridays of Lent, and even doing crochet while listening to the Screwtape Letters one year in imitation of the Desert Fathers’ habit of working while praying. I’m forever grateful for the formation in the hours and common prayer in that church, as well as many friendships. After ten years there, we kept feeling the tug to the Orthodox Church. When my husband’s study of iconography put us in touch with a local Orthodox family who invited us to church with them, we knew we had found home.

It wasn’t just that the Orthodox Church had clear expectations for behavior and an emphasis mercy and a liturgically shaped life, all of which are welcoming to autistics. It was that every good that I had experienced a little in other places was fully present, was sourced, in the Orthodox Church. But beyond those qualities, I found two gifts of the Orthodox Church most helpful as an autistic person: First, the communion of saints and the prayers teach me to ask for help. Second, the iconography and full-body patterns of prayer allow and encourage me to think outside my own head. I’ll elaborate on what this is like below.

First, asking for help does not feel natural to autistics. It’s not that we think we can do everything ourselves or that we don’t appreciate others; we’re just not used to thinking of asking for help as a matter of course. We have to learn to ask for help and practice asking for help and ask ourselves when we’re feeling really down on ourselves and ashamed or sad or frustrated, “Hey, am I doing something wrong, or do I just need help?” Because the number one thing most of us get confused about emotionally is whether we’re sorry about something (Did I do something wrong? Why do I feel like I can’t get this right? Like there’s something I need to do right but can’t?), or whether we just need help. In a relationship with God, it can get really confusing if you don’t know you have to ask for help. It can be VERY confusing if you’re in a tradition that says God’s waiting to smite you. But the Orthodox Church prayers call God “the One Who Loves Humankind,” and every prayer emphasizes God’s mercy (One of my favorites is a nighttime prayer that speaks of God’s “usual love” for us.). The threat of smiting is taken away, which gives me room to feel the contradiction in my emotions and reality. Wait. Am I scared God is going to be mad at me because I did something wrong, or do I just need help? Even if I did something wrong, guess what? The Church teaches me through the prayers to ask for help! And not only from God, but from the multitudes of saints who love me and assist me. It’s hard to fall into this pitfall of my disability when I have saints standing round the pit warning me away from it, saints reaching down to me to pull me out of it, and saints with me boosting me up out of it, and my Lord Jesus Christ alongside me, lifting me out with His ready help.

Second, like most autistics, I have too much going on in my head to think inside of it. I need the whole room in order to think my thoughts and feel my feelings. One of the hallmarks of early autistic intervention is teaching my children to communicate with me and others rather than simply moving around a room. But because I’m also autistic, I understood what the children were doing. I was able to give them the freedom of pictures and words and companionship so that they could thrive. I didn’t primarily focus on ordering their time the way that neurotypical interventionists would, but I ordered their space, giving them resources for expression. I gave them places in the house to meet God. I gave them places to retreat, to rest, to play. I put their communication aids on surfaces around the house where they were needed, incorporating their (and my) natural way of thinking with the resources they needed to learn to speak and think more easily and to communicate with the people they love and who love them. I made love something they felt in the room, something they could touch, a game with clear rules of engagement, a song with their singable parts and movements patterned so they could join in easily. The external ordering, the scaffolding of love, were vital to teaching my children and bringing the three of them who were nonverbal into fully verbal abilities. The Orthodox Church does something like this for me, both bodily and spiritually. Every time I go to church or pray with icons, I experience a scaffolded spiritual love and joy, an embracing story that tells me I’m welcome and draws me further into relationship and communication with God, beyond what I could have guessed. Icons and the patterning of prayer to draw our bodies and spirits towards God are gifts that allow me to wander like an autistic child towards the love that is waiting for me, to learn while I am living in welcome, to feel loved and valued, and to learn to love Jesus even before I know Him fully. When you pray in a church or a prayer corner filled with icons, you start to understand that they are not only windows to heaven, but mirrors reflecting the reality that surrounds you. You start to feel part of the company of saints, like someone loved by God. You start to hear your line of the music and to join in the song. You start to know that you are good, you are loved, you are welcomed like a child; you are home.

[image error]Read more in my book, Of Such Is the Kingdom: A Practical Theology of Disability

The post The Biggest Gifts the Orthodox Church Gives Autistic People Like Me appeared first on Summer Kinard.

August 14, 2020

Beginning

I’m forty-three years old, and I only started praying Morning Prayer a little over a month ago. I don’t mean I would wait till afternoon to pray for the first forty-three years. I mean that until a month ago, I wouldn’t pray formally beyond the Lord’s Prayer when I first woke up. What changed? Awareness.

I had been relying on the cues I’d seen in people around me for how I interpreted the right way to say Morning Prayer. The cues were always the same: 7am or earlier, fully dressed and presentable, wide awake and polished. In other words, I thought only “morning people” could really pray morning prayer. They seemed to think so, too, and came across as prim when they invited me to be like them. I tried to adapt my lifelong night owl ways to incorporate the morning hours, but I only got as far as praying the midnight prayers and, often, the Lauds hours at 3 or 4am. I figured that I would pray for the morning people while they slept, and they would pray for me while I slept in. But I always felt like I was missing out. I liked those morning people, and I could see the peace they carried from Morning Prayers.

I wanted to adapt some practice of Morning Prayer even if I couldn’t be like the early risers. But there was one other barrier for me as an autistic person: the rubric that said the prayers were to be prayed “immediately” upon waking. Immediately? Oh, no. What if I had to use the restroom really badly? What if I wasn’t fully dressed or had dropped my glasses off the nightstand? What if I was awakened by a child’s needs? What if I worked late the night before and needed to take an hour to be really awake with both eyes and minimal yawns? What if I was too thirsty to talk? What if I was too nauseated from pregnancy (back in those years when I was pregnant), or too exhausted from illness to sit up in bed? Should I still pray “immediately” after I had changed clothes, used the bathroom, slowly maneuvered to my feet safely, pinned my hair back, found my glasses, or comforted a child?

For most of my adult life, I found the need for immediacy so confusing that I would close the prayer book or prayer app and just pray the Lord’s Prayer and maybe the Trisagion as I venerated an icon in the late morning. Then, as often happens, I noticed my children getting hung up on rules, which made me notice that *I* was getting hung up on rules. Oh. Maybe “immediately” was flexible for me, just like “eat breakfast foods at breakfast” was flexible for my child. I tried morning prayer the next day at 9:37am, wearing my pajamas, my hair absolutely too energetic for public viewing, interrupting myself with yawns and slow blinks. I held onto the bed and the rocking chair to kneel for the kneeling part and nearly tipped over when said the Lord, have mercies.

You know what? I didn’t break Morning Prayer by not being a morning person. I was clumsy and awkward and unkempt, but I was alone in my room. My thick, slow, sleepy accent was just fine for talking to the God who calls us to rest in Him and walks with us even when we mosey.

Over the ensuing weeks, I said Morning Prayer anyway, even when I had to use the restroom urgently or got woken by a child or couldn’t find the sash to my robe (a child had swiped it to use as a streamer) or woke up very late due to post-Covid syndrome exhaustion. It turned out that I could still pray even if I was lying down due to my health or if I had to return from a brief trip to another room. A few days I said the Lord’s Prayer and Third Hour prayers instead, pushing the envelope but keeping the habit.

Now I love praying Morning Prayer. I still feel most vulnerable and open to God at night, but I’m feeling the joy of commending the day to God at whatever time I join it.

I’m sharing all of this in case you’ve maybe felt like I did, that you couldn’t follow the social cues of prayer and thought maybe that meant you couldn’t pray. I hope you will try it anyway, whichever prayer it is. God will steady the shaky hand of the one that lights her first prayer candle or whispers his first Jesus prayer. It turns out that the riches are freely given even to the newcomers.

[image error]

Where will you begin today?

Like this blog? Don’t forget to follow!

The post Beginning appeared first on Summer Kinard.

August 8, 2020

Spent

How long can I carry a broken heart through the world? How long can I imagine myself severed from all that is good?

The pain started when I was an infant. My biological father brought his new girlfriend with him to see me and leave me and my mother behind. He wasn’t proud of me. I was proof that he had seduced a teenager on her seventeenth birthday. I didn’t see him again until I was fifteen years old, when he made a lewd joke about my mother and gave me a twenty-dollar gift card for missing my birthdays. I had walked unwanted through the world for fifteen years by then, and twenty dollars was what he offered in place of his blessing.

I only met my biological father because my stepdad, who I thought was my biological dad, rejected me. He was drunk and wanted to get drunker, so he tried to pick a fight to justify leaving us for a few days. It was a pattern I had learned by heart, and I set myself against it. That night, he tried to accuse me of not cleaning my room, but I had cleaned my room. He accused me of not doing my homework, but I had done my homework. His game was to find an imperfection on my part to use an excuse for his three day drinking binges, so I tried to be perfect. I was impeccably polite as he cussed me and insulted me. Finally, instead of letting me win the standoff, he pulled out his secret weapon, one I had not suspected and could not defend against. “You’re not even my daughter!”

I broke. “How can you say that?” Tears came, as the burning in my face switched from anger and shame to grief.

He had done what he meant to do. He had provoked a negative response. He stormed out of the house to drink away his paycheck, leaving my mother and us four kids to worry about him. My mother sat on the couch and lit a cigarette. “He’s telling the truth. You have a biological father.” She arranged the meeting.

I was part of a church then that emphasized how much I was a sinner. But they also told us to read the Bible. I did. I read it as someone whom no one loved, who had managed to be rejected by not one, but two fathers. I read cryptic promises there: God would listen to people who wouldn’t stop asking for help, and God wouldn’t reject me for being brokenhearted and crushed in spirit. God would not put me to shame. That last one was hard to believe. I had been nothing but a shame to my family. No, that’s not what it looked like outside, no doubt. I had achieved highly and been as good as I knew how. But I had survived a lot of abuses, too, and I had acted in ways that made me ashamed to exist. I was afraid that all I did would be spoken of as good intentions that had led me into hell anyhow. Hell was my home. I didn’t like it, but anyone could see that I smelled too bad and was too poor and too unwanted to live anywhere else.

Except that I wanted God. I was terrified that I was too trashy to be loved by God, but He had said He wanted people like me. I started to cry myself to sleep every night, praying, “Please, please help me.” I would read and say again and again, “a broken and contrite heart, you will not despise.” I read the prophets and saw God say to the oppressed and broken ones that they would not be put to shame, and I knew I was one of the ones He was talking to.

I forced myself to call God “Father,” even though my fathers rejected me. I didn’t think “father” meant what they were. Jesus treated me so different than my fathers had. His Father must be different. I read the promises about becoming heirs with Jesus and coming to be one with Jesus, but I knew I was trash. I couldn’t imagine God being so unjust as to associate freely with someone like me. I saw myself in the story of the woman who was willing to be called a dog if only God would help her daughter. I could be a dog under God’s table. At least I could be near Him, then, even if He didn’t like me. I assumed He wouldn’t like me.

There are a lot of smug people who mock Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo (Why God Became Man), largely because they haven’t read it, and those people ought to shut their mouths. When I read in that book that God’s justice saw human nature in the mud and went and cleaned it up, I was overjoyed. I had been wrong about the way God worked. He wasn’t embarrassed to be around a trash person like me. He saw that I wasn’t trash at all and came and got me.

I had read the story of the pearl of great price that one would give everything to buy. I set about breaking the cycles of abuse and addiction in my family, seeking to please God rather than man. I was put to shame, rejected by my family, hated by my parents. I distanced myself for decades in order to not play a role in their abusive cycles. I heard people lie about me and spread vicious lies through the family. My mother took credit for all the things I did well and invented evils when she wanted sympathy. My youth group ignored me. My new youth pastor’s wife told me that I was using the need to obey God rather than man as an excuse to be disobedient and rebellious (never mind that I was using it as my anchor on virtue and bravery, without sacrificing obedience and deference). One day God showed me a vision that gave me a sense of His presence with me. When I confided in my youth group worker, she told me I was codependent and just wanted to save the world. When I tried to ask for help from extended family, my mother wove lies and suggested I was disturbed and might need to be institutionalized. I was alone. I hoped it was enough to buy that pearl, because I had nothing else. Even my material belongings weren’t really mine. My father begrudged the food I ate and told me so. My mother pawned or traded anything I owned of value and ruined the rest of it by neglect.

I don’t know how to be a good person. I don’t feel like one, and I’m not one. I don’t have the equipment. I feel like someone told to make an electric circuit who only has dirt and sticks at her disposal, no wires, not even lightning. All I hope is that God doesn’t require that I be good, that He has a way in for people like me. Look, I know how it looks from the outside. I am accomplished and smart and stable. But inside is a desert with a river in it that gushes always. And I love that water and the God I meet walking here beside it. And I also don’t know myself. Because I am comfortable seeing myself as the idiot, trash child in the dirt who can’t conduct electricity, but I act like a disciple who has the river of life in her heart. Did I give up everything, then? Or do I need to pay another installment on that pearl?

What I want to tell you is that I am the pearl of great price. I thought it was my job to give everything I had to go buy it. And I was embarrassed at how little I had to offer. But it was me all along. God gave everything He is to come get me.

How long can I walk through the world with a broken heart without seeming like ungrateful trash? But here I am again, crying and lying to myself.

I want to believe that I can be good, because God said so. I want to believe that God made me for something better than rejection. That I can cooperate with God. That synergy with the Holy Spirit is real and I am not just getting in the way. But I’m so hurt. I have a broken way of knowing.

I know that I’m saying stupid stuff and not even knowing what I’m saying.

What I think has happened is that people tried to put me to shame, and I let them. I did wrong in accepting their lies. God isn’t the one wearing the jackboots that kick me when I’m down.

I have come to the end of story. I cannot tell myself a story that propels me or feel a way forward to God. I am spent like the woman who suffered a hemorrhage for twelve years. She spent all she had and was no better but rather worse. But she like me had let a promise creep into her heart. She had heard Isaiah 6 and seen in hope the hem of the Lord’s robe filling the temple with glory. She recognized that hem when she saw Jesus in the crowd. She wasn’t good enough to speak to him. She knew her place. She was human trash, unclean, untouchable. But that hem! If she could just touch it, she knew that God would heal her.

And of all the women in the Bible, Jesus called her Daughter.

There comes a moment when I am spent. I no longer have strength to weigh seeming pieties and suss out the medicines prescribed to others that are poisons to me. I have no energy, no stories to tell myself, to protect me from the truth. The lie is that I am not good. If I keep saying that, I am worshipping the idol of my desire to be accepted by my fathers. To save face for them, I must be bad. To justify their rejection, I have to say I’m evil. To bolster their egos, I have to say I’m stupid. But the truth is that I’m mostly good. I make big mistakes. I cuss. I get my feelings hurt and have a hard time letting go of problems I can’t fix. I am kind and virtuous, mostly. I don’t do evil to others willfully. I am blazingly brilliant. I work hard and have insights. I’m prayerful and generous. I am willing to stand in the flame of God even when it burns up my delusions. I was stuck in hell, and Christ came and got me.

I am my Father’s daughter. I have touched the hem. I have felt the healing. I can no longer pretend to be what I am not.

The post Spent appeared first on Summer Kinard.

July 14, 2020

Scandalon

As soon as dawn woke the birds, before the sunrise had warmed the cicadas into song, the villagers smiled into the light. “Today is the feast,” said the old ones in their voices like old wine and autumn leaves as they patted their hair into place. In their rooms, the ones who lived alone checked their hems and faces and nodded to their own faces in the mirrors. They would go out today. “It’s the feast!” they said to the newspaper and the cat. “Today is the feast!” mothers and fathers told their children. The children needed no reminding. They were already hopping or staring, wide-eyed, at the imagined splendor of the gathering that was to come. The younger ones advised their stuffed animals about the joys that were near at hand, the older ones advised the real animals under their care. Mothers brushed lint off sleeves. Wives straightened collars and ties. Fathers tied shoes and helped with the tricky buttons near the neck. Husbands nodded and told their wives they looked beautiful. “She always does,” each said.

But I have not told you of the food. The dressing and rushing about was not done in an atmosphere of morning dew but of rich aromas, spices and roses and honey sweetness, saffron and butter and onions and wine. There was meat and potatoes, breads and scones, vegetables roasted into sweetness, baked fruits and pressed fruits and iced ones, too. There were coffee and tea enough to lift the weariness of each. Everyone could see or smell and almost taste the feast on the air. Each had cooked some of it and laid it out in offering in the night, to be revealed and reveled in now that it was morning, and there was always more than all of them had made together.

The village wasn’t magic. The food kept overnight because there were keepers who stirred it and kept it warm or cold or boiled and ready. All through the dark night, the keepers kept the food ready. They laid it out on clean plates and made ready cups that one need only turn over to fill with every good drink imaginable. The keepers would be at the feast, too, some of them, but some had already gone home to sleep until they waked to another feast.

You can imagine the singing on the way and the toasts and laughter when the people sat down together, young and old, single and coupled, loud or quiet. Everyone had a place, and when someone new arrived, the rest squashed up to make room, only to find that there was still room to spare. The people will tell you what it tasted like. The children who grew plump and strong at that table or who grew, loved, before they went off to sleep, will tell you of its sweetness and of how the adults took notice of them. They will tell you about the way their neighbor’s shawl caught the light or how the grandfather who wasn’t their grandfather told them about lemons in hot water or watermelons in aqua fresca. The adults smiled with satisfied lips, reveling in the balast of the fellowship and the food. The old ones didn’t eat as much as they used to, but they loved to use their waning strength to serve a little pie for the one next to them or help to tuck a napkin for a little one.

The feast happens every day, so you probably recognize it and see how thin my words are compared to the chewy bread, the thick pith of joy at the table you just left.

But maybe you didn’t notice after all.

Maybe you were distracted or frightened away by the wraiths that refuse to sit down at the table. They are loud, and they have so many reasonable sounding points. The saffron does stain ones fingers, and lime will turn your hands darker in the sunlight. Did you know, I heard from one of them that there was a line in a cookbook that definitely condemned altogether the practice of pickling? Yes, and if you match the patterns of Asclepius with Basil and Cyrus and Dun Scotus and Erasmus and Faust, you find an alphabets worth of things wrong with eating. Another wraith was certain that taking food together in any way was sacrilege. “Better acorns and grasses with the beasts of the field,” he said, “than to eat with men, those creatures of hypocrisy.”

Where I was sitting, a great scholar happened to be nearby, who invited the wraiths to refresh themselves. When they refused, the scholar warned them sternly that they would never grow healthy on a diet of their own righteousness. To my astonishment, the wraiths answered in song. They gathered around a little printed sheet with a screeching melody, “Better to starve and die and ruin the food than to sit as equals with humans.” The scholar was not deterred, having heard this song before. “And what are you, that you believe yourselves beyond the need of nourishment?” The wraiths passed scraps of grubby paper back and forth and gathered into loose ranks like an amateur choir, more loud than disciplined. “We are better than you!” they sang.

“But are you better than food?” the old scholar asked. “We are better than you, and anyone who will come with us can be better than you, too.” I laughed and looked from the scholar to a wizened old couple near me. “Who would leave this feast?” I said to the old woman. She shook her head, her chin down in wordless pity. I looked up. Two people, a young man who had not eaten much because he refused to ask anyone to pass the dishes his way, and a middle aged mother who would only eat a few olives and apples because she was frightened of contagion, had joined the wraiths. “See?” they screamed, loud enough to momentarily distract the festive atmosphere nearest, “These people see the truth! We are better!”

“But they are only hungry,” a little child said from his aunt’s lap where he was stickily enjoying a jar of jam with occasional bites of bread and cheese. “Yes,” said the old woman. The scholar and the old man shook their heads and prayed and placed their hands protectively on the backs of the chairs nearest them. “If they would only eat,” the child concluded, “They would know better instead of thinking they are better.”

The post Scandalon appeared first on Summer Kinard.

May 26, 2020

(C)*

*(C) is the Roman numeral for one hundred thousand

I watched the grass grow the summer I was eight years old. The Texas heat and loam met in the upside down world where I leaned back and switched my focus between high, bright clouds and the flipping, unfurling green turf where I lay. An hour in the shade on a blazing afternoon feels like a lifetime. I would rise, itching from the grass and the secret of its growing. I would see a person or a bird and want to tell them how the grass was alive, how I had seen it grow, but I wouldn’t have the words. How can you tell your grandpa that you respect the grass when he spends so much time mowing it?

That wonder resurfaced over the past few weeks as we’ve struggled against the verge of overgrown lawn and wildflowers in our backyard. I was sick for so long, and the grass had its growing to do whether or not we did our part to trim it. I went to bed at the beginning of the clover and climbed back into the sun when the yard was covered in tall, yellow Texas dandelions. I have used my scarce strength to weed and sow the herb garden -it is a prayer garden-, but we haven’t tamed those wildflowers yet.

I knew that grass would grow when I wasn’t looking because I had spent those hours watching. I knew the coronavirus would spread, almost in silence, slowly, but right before our eyes, because I have survived it. It’s disorienting, macabre, to feel the symmetry of growing things and a deadly pandemic. But they are linked in my mind, by my suffering, by my waiting, and by my hope. I could only stand upright for a few minutes at a time when I emerged into my garden after nearly two months, but I needed to tend it. I needed to plant seeds and remove weeds and make sure that my herbs had sun and water. The weeds might have grown while I slept and struggled, but so did the seedlings I had sown at the beginning of March. Our lavender blooms bright purple, and the five little lavenders that survived along with me are almost ready to join it. They are fruits of prayer, fruits of hope.

I have seen the horrifying death totals for our country, one hundred thousand people dead in three months from the monster virus that didn’t quite grab my feet while I was in bed. I bring them with me to the garden, the dead. I don’t know them, but we are so near to one another. We looked at death together, but my death decided to stop for a while, to enjoy the garden or take in the sea air, to wait its turn. I know I did not earn my life, just as they did not earn their death. The virus is impartial, a shadow echo of love, which is also impartial.

For friends and family, I sometimes light candles when I pray, sometimes tuck a memorial plant into the garden for them. I don’t have one hundred thousand candles. I putter around the herb beds. There are only a few hundred herbs here, a bed of basil waiting on September to come into its glory, a patch of sage that will flavor our July, mint snaking under everything and waiting to cool our drinks through the sweltering months ahead. I walk into the sunlight, into the untamed meadow that grew unhidden while I prostrated myself inside, healing. There is enough room there to sow one hundred thousand mustard seeds, one hundred thousand clovers.

I tell my husband I’m thinking of sowing all of my 20 pounds of mustard seeds in memory of the dead. He looks at me sidelong, kindly but not understanding. “You want to plant all of those seeds in our yard?” “I want to pray for the dead, and I don’t know how else to do it.” “Hmm.” He doesn’t disagree. He, too, knows how to wait.

I sing the Trisagion as soon as my strength returns. It carries me around the house, and I carry it through my chores and resting. Sometimes I don’t know I’m singing it until I feel my heart flip and unfurl as it fills my body. I’m still weak. I still have to stop and catch my breath too often. But I’m strong when I sing. The strength to sing again has grown when I was not watching.

I read the news and make my cross and kiss the Theotokos, who really gets it. She knows what’s going on, what it’s like. I look at Jesus and just nod. He’s acquainted with grief. I search for outdoor icons. I want them in my garden, too.

I sing, “Eonia i mnimi,” in Greek and “Everlasting be their memory,” in English. I water the garden. I light a candle and let incense sweeten the house. Outside, the basil and lavender have grown enough to keep the mosquitoes away from the back door.

It would take years to sing enough for one hundred thousand people.

Maybe I should plant one hundred thousand clovers? I could sing, “Christ is risen” over the clover, the white blossoms like so many bones, their sweetness like incense. I could sing over all of them once a day instead of trying to count out prayers for each. It would only take a pound of clover. The kids could help scatter it. We could dust the seeds off of our sweat-sticky hands onto the lawn and the patch of dandelions.

I find my bag of mustard seeds. I’ve distributed some of them in play bins and dropped a lot of them while teaching, but I still have over five pounds. I would only need a half pound for now, about one hundred thousand seeds. I could scatter them in a few minutes. It would be quick, and the yard would be all yellow when they sprouted, a paradise for birds.

But I am so tired still. Even the planning of so much sowing has worn me out. I have to rest first. A day passes, three days, ten. I go to the icons again and reach out my gardening hands to Christ and the Mother of God. They hold my heart, and it is filled with prayers, one hundred thousand prayers, one hundred thousand seeds cracking open to eternity, all wrapped up in a wrinkled brown packet, waiting. I tuck the seeds and my heart into their hands. “I’m so weak,” I whisper. “Please. Tend them.”

The post (C)* appeared first on Summer Kinard.

April 11, 2020

Listening with Lazarus in the time of the Rona

My breath catches over the steaming cup of tea. I have curled myself around the tea in my sickbed. The tea is at the center of my hoard of pillows, blankets, and the small, bright screen where I read that people think that Lazarus was sad after he rose. It was that assertion that made my breath catch. It’s absurd. It’s an affront. How could they think that?

Don’t they know that Lazarus was filled with joy at hearing the voice he had always listened for?

Lazarus was listening for Jesus long before he died. He would hear his friend’s voice on the road of an afternoon and rush to find his sisters.

“Martha, bring the good olives. Mary, set out your finest cheese. I will get the water to wash his feet.”

He listened for the voice on his sickbed, his deathbed, and in the tomb, he listened.

“Lazarus, come forth,” he heard, and he roused himself as he had many times before, under starlight and hot sun, to greet his friend and Lord.

He listened through the week of palms and the passion, too. He listened for the resurrection and heard as in an echo his sister’s words on the morning it happened. Prophecies have a way of being true in all directions. Martha said that already there would be an odor when the tomb was unsealed. When Jesus rose, Lazarus rose from his bed in Bethany and stepped outside to breathe the odor of the life wind that rushed out from the Lord’s tomb. His sisters were on their way with myrrh and spices, but this wind smelled of a garden ripe in the sun with every fruit in season and every herb at its prime. The breath of life itself flowed over him, and he knew what it meant. His own rising rhymed with it a little, the way a child’s poem almost rhymes an obstacle with the things she loves.

The wind blew him to the island where he became bishop of a flock and taught others to listen for the voice of their Shepherd. He was always listening, always expecting the joy of the Lord’s return.

He heard the voice all his second life. He greeted beggars as though they were his friend. He set out food before the hungry ones as he had for his friend. He washed their feet. He listened to them and spoke with them and shared with them the fire that kept their bodies warm and the hope that warmed their souls.

People who rise do not sorrow. They watch. They hope. They know the shape of joy to be greater than smiles. They know the shape of love is greater than death.

I am back to myself, here in my bed of convalescence. For weeks I have waited, to breathe freely, to have my strength restored, to hear my Lord calling me into life, here or there, though I tell him bluntly that I am still needed here, please. Gradually, propped up on pillows, I have arrived at Lazarus’ day. He is gentle company, because he sees what does not end. There is no fear in him.

I wonder if he craved salty cheese when he arose, and if his sisters brought him broth for weeks after his rising. Does one convalesce after death, or is that a need only for those who were pushed near death by a virus or some other threat (though for me it was the virus)? Tell me what water tasted like to you when you rose. Tell me how your attention shifted.

Where did you listen for him? Where do you hear him?

Why are you so quiet, Lazarus? What does He say?

The post Listening with Lazarus in the time of the Rona appeared first on Summer Kinard.

March 17, 2020

Nonverbal Prayer During the Pandemic Crisis

Now is a time of caution, preparedness, and grief, but that does not mean it is not also a time of prayer.

As I detail in my book, many people with disabilities need ways to pray without words at least some of the time. People without disabilities will also find these prayer practices helpful, alongside their usual practices. Here are a few resources to add to your prayers as you keep your family near.

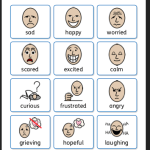

God is with us in all of our feelings

In this pandemic, the likes of which is unprecedented in our lifetimes, we will feel a full range of emotions. Every one of those feelings are welcome to God.

Use the first page of this prayer printable along with your family icon corner, or print both pages to use them together.

Download the Feelings Prayer Here: FeelingsPrayer

Plant a Hope and Memory Garden

Memory

In my family, one of the ways we pray for people who have reposed is by planting significant flowers that remind us of them. When we care for the plants and see the plants bloom every year, we remember those who have reposed and thank God for them and make our cross in prayer for them. In my family, some plantings are specific. Each year, I plant a few more daffodils in memory of our third child whom we lost to miscarriage just when the daffodils were blooming several years ago. Cannas and marigolds remind me of my dad, because he always had those in our gardens growing up. We remember my husband’s grandmother with our fig trees and my great-grandmother with any red flower we can manage to grow (Granny LOVED red). We also have some plants that remind us of the usual mercy of God, like Michaelmas daisies, which grow so vigorously that they overtake any place they’re planted, reminding us that we are all held dear.

[image error]

This season of pandemic will sadly bring with it new griefs, either of those we hold dear or those in our community for whom we would like to have a way to pray. Find a plant that grows well in your area, and remember them while you tend it over the seasons. If you don’t know which flower to choose, buy roses for the Holy Theotokos and ask her help in praying.

Hope

Spring is also a good time to plant basil herbs. They grow easily from seeds, and if you start them over the next several weeks of this social distancing period, they will be ready to harvest at the end of summer when we celebrate the Elevation of the Holy and Life-Giving Cross.

[image error]

Nest and Egg Prayers

How lovely is thy dwelling place,

O Lord of hosts!

My soul longs, yea, faints

for the courts of the Lord;

my heart and flesh sing for joy

to the living God.

Even the sparrow finds a home,

and the swallow a nest for herself,

where she may lay her young,

at thy altars, O Lord of hosts,

my King and my God.

Blessed are those who dwell in thy house,

ever singing thy praise! -Psalm 84:2-4

CRAFT

Materials: Plastic or papier mache bowl, school glue, brown paper such as packing paper, bits of yarn or string; plastic eggs; small printouts of photos of loved ones.

To set up this prayer opportunity, start with a plastic bowl (or make a papier mache bowl if you’re really crafty and have lots of time). With your children, tear small pieces of brown paper and glue them to the inside and outside of the bowl. (We gave each child a little puddle of glue for dipping the paper.) Have them untwist little sections of yarn, and glue the yarn to the bowl, concentrating the fluff on the inside.

Once the bowl is ready, print out photos of loved ones for whom you would like to pray. Have a child cut them out, or help them with this step. Work together to fold or roll the photos to fit inside the plastic eggs.

PRACTICE THE PRAYER

Place the nest under your icons, and have the children add the eggs to the nest as a way to pray for the people in the photos.

You might enjoy saying, chanting, or singing the verses from the Psalm. I recited them for my kids, then sang them. Afterwards we sang a bespoke song that went, “We are God’s chicks. Cheep! Cheep! Cheep!” This activity is a great way of talking with anxious kids about how God loves us and is a place for us even when we’re vulnerable.

Share this post, and comment below if you try these ways of praying.

Don’t forget to pick up a copy of my book, Of Such is the Kingdom: A Practical Theology of Disability , for more best practices for including everyone in prayer.

The post Nonverbal Prayer During the Pandemic Crisis appeared first on Summer Kinard.

March 14, 2020

Wands Down, Crosses Up! : Against Magical Thinking

Pandemics, like other suffering, set a pin on the map of history, showing us a little of our place compared to what has come before. In this pandemic, we live again in the days of wizards, people who tell us confidently how to tame God with a word, a thought, a sign.

They weave their spell by tapping the primeval desire to catch divinity in a net, to trick a god into serving you and thus overcome the fierce terrors of mortality and a life of suffering. Though the Judeo-Christian tradition has steadfastly resisted such thinking, it is the thinking endemic to paganism, or what we would call “spiritual but not religious” or “positive thinking.” Some mistakenly call it “faith.” It’s the shape of the thought pattern of people who talk about the Universe doing things for them or who believe they can control their fate with karma.

It’s the stuff of magicians and lords of old who tamed dragons by tricking them in the Old Tongue, the ancient speech shared by all wise beings and largely forgotten by humankind. The desire for control and justice as we see it is the ancient tongue that lashes like wildfire through every generation. Will to power is the language of dragons. It is also known by other names: Magic, after Simon Magus who tried to buy the Holy Spirit (and failed); Concupiscence, that old tendency towards sin that knocks so many good intentions off course (Love, yes, but can’t I control you, also?); It is the language of dust and tombs.

When we come face to face with mortality, the Old Tongue is the dust in our mouths when we tell people that they need not fear to catch a virus or remain disabled, if only they have faith. In the Old Tongue, “faith” means “trickery.” It means “contract” and “tit for tat”. It means “to drive a spile into the underside of a fat, distant god so that some of the lifeblood of him trickles down into our buckets”.

But we have a new Word in the Church, a Word older than creation. It means life, and it means love, and light, and we know that Word as a Person, Jesus Christ. He is our life, love, light, joy, peace, health, and we are in Him. He is with us.

“With Us” is as close as the Old Tongue gets to saying His name. In the Old Tongue, “With Us” is a threat. But the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, turning “With Us” into a gift and the best way we can talk about healing.

The good thing about sickness and disability, whatever other good things grow in the lives of the good people (called so by God who made us and is with us) that bear it, is that illness and disability fill our old tongues with dust until we seek a better Word. Bodily suffering is witness to God With Us.

“With Us” is why we say, “Glory to God in all things!”

It is a fierce and terrible love, more ancient than our sins, outlasting illness and death and any prosperity ill-gotten by tricksters. God “With Us” turns our hearts towards each other in love even when love requires us to stay apart for a time to protect the most vulnerable among us. The meter of “With Us” acts rhymes with both Lent and Pascha, withdrawal, denial, and freedom, embrace. It is joy through and through, to those who suffer and those who bear with the suffering. All of the suffering is the suffering of the Word With Us. The Word is With Us in all.

“With Us!” say the Christians, and to those who only know remnants of the Old Tongue and none of the new and ancient one, “With Us!” sounds like “Cross.”

[image error]

The post Wands Down, Crosses Up! : Against Magical Thinking appeared first on Summer Kinard.

February 25, 2020

Hangry for Righteousness

Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled. Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy. –Matthew 5: 6 & 7

[image error]

When things get hard in my life, like when several of my special needs kids hit challenging growth spurts at the same time, and I am exhausted, and literally hungry and thirsty from not being able to take care of myself in a timely manner, and I know that I need God but cannot muster the politesse that I have been shamed into believing I need, I go to God in lament.

Lament is an old word for praying when you’ve hit a wall, reached rock bottom, been done wrong, can’t even, or when you’re miserable. It’s not a bad or lesser way to pray. Sometimes it’s saltier, though.

When I get into a hard place, I find myself having to beat away illusory obstacles to prayer. I’m not good enough to pray or coherent enough or polite enough. I’m too embarrasing to pray. I’m too jacked up and flat out rude and fed up to pray. I don’t have anything nice to pray and should not say anything at all. I can’t even imagine what God could do about any of it. I don’t know if it will matter if God popped up in a glorious mandala and revealed all, because I’m too tired to do anything about it if He did.

But none of these excuses take away my need for God. So I say, “Be that as it may, I need you.” Or I holler, “I don’t know what to do!” Or I cuss outright about being done wrong or not being able to get it right. (I’m not saying you should cuss. I’m saying it’s better to cuss to God than to not pray.)

Sometimes my needs go beyond a temperate desire for mercy and right into hangriness for righteousness. I want God to put me right, to heal and mend right now, to show me the way even though I’m too sleepy or my eyes are too puffy from crying to look.

Well, I’m not the first one to pray like that. The Psalms are filled with rejoicing and reveling in God’s goodness, and they’re also filled with laments.

This Lent, for the first time, I’m part of an Orthodox women’s Psalter group. In years past, I wasn’t excited about the Psalms because I shamed myself out of feeling ok about the way I pray when things get hard. This year, though, when an Instagram friend invited me into her Psalter group, my heart was ready. I need a deep watering of the roots of my heart. I’m thirsty for God, and at last I feel brave enough to admit that God is the best food for those who are hangry for His rule.

Good Lent to y’all!

I’m reading from The Ancient Faith Psalter (Amazon Affiliate link), but I have also heard beautiful reviews of Songs of Praise: A Psalter Devotional for Orthodox Women (link to Ancient Faith store). While you’re gathering books, don’t forget to check out my book, Of Such is the Kingdom: A Practical Theology of Disability (Amazon affiliate link), available wherever books are sold or through your local library.

Are you reading more this Lent? Comment to talk about it!

The post Hangry for Righteousness appeared first on Summer Kinard.