Rebecca Copeland's Blog, page 2

May 21, 2025

The Tobacco-Colored Suit

I have a closet dedicated to all the clothes I never wear: tailored suits with calf-length skirts, jackets with peplums and padded shoulders, Diane-Von-Furstenberg-look wrap dresses (which are still nice, I just have no occasion to wear them).

Some are too snug now, or too out of fashion. Mostly, they don’t fit my current lifestyle.

These days I walk to work—parking fees having skyrocketed—and I dress for ease of movement.

I haven’t worn any of the high heels that stand expectantly at the back of the closet. Whenever I catch a glimpse of them now, I wonder how I ever did.

Most have heels that are a manageable two inches, but some are higher. Did I really wear them?

I can remember the way my feet would throb after an hour or so teetering about on my tiptoes.

For some reason, those shoes made me feel powerful and pretty.

Now I lace up sneakers or zip up ankle boots for the mile-long walk to the campus where I work.

I must stomp hard the whole way there because I have to change the heels on my boots about once a year. The cost of doing so is almost equal to the cost of the boots themselves. But a comfortable boot, a boot that can carry you to and from work, is worth holding onto.

The items in that closet, though, are not. Even so, I’ve kept them for years—there, in that closet at the back of the house—just hanging.

I’ve arranged the clothes in neat zipper garment bags, keeping them at the ready, just in case I have an occasion to wear a tailored suit with padded shoulders.

Who knows?

Among the suits is one I bought in the winter of 1990 when I was readying myself for job interviews.

Mother and I went to the Hudson Belk at Crabtree Valley Mall in Raleigh during the Christmas sales and found it.

“What about this one, Mother?” I asked as I pulled the suit jacket off the rack.

“It’s nice,” Mother noted. “The brown complements your hair.”

“That’s tobacco colored,” the saleswoman corrected.

Most of the suits on the rack were bold primary colors—royal blue or robin red—or sickly pastels with flower prints. I despaired of finding anything appropriate to wear to an interview for a job in Japanese literature.

But this suit was different.

The tobacco colored suit

It came with a slender pencil skirt and a short jacket that nipped in at the waist.

Designed by Elliott Lauren – dry clean only – the garment cost much more than we had anticipated.

Before we could move on, the saleswoman grabbed a silk blouse in a deep purple hue and pushed me into the dressing room. The jacket fit just right, but the skirt was too large, so the woman rushed back to the rack and brought me a smaller size, which she thrust over the dressing room door.

It never occurred to me that you could mix and match sizes!

Mother’s eyes lit up when I stepped out to show her.

“Oh, Becky, that’s the one.”

The suit was modest, understated, and elegant.

It was me. Or rather, it made me look like the me I wanted to be: a distinguished university professor.

I can’t remember how much it cost now. We’d found it on the sales rack, but Mother and I were used to shopping at Sears and Roebuck or J.C. Penneys. The suit was more than either of us had ever paid for a garment.

Mother bought it for me. An early Christmas present.

I wore the suit to three interviews that January.

It gave me confidence.

Of the three interviews, two resulted in job offers.

The suit became my special talisman.

After I moved to St. Louis to start my job at Washington University, I occasionally wore the suit to conferences and important lectures or anytime I needed to look particularly professional, but for the most part, it has hung in my closet, waiting.

Now the waistband is too snug and the wool fabric too scratchy.

I can’t help but think it is still stylish, even with the padded shoulders.

If I gave it away, would it bring another woman confidence? Would it walk her into a job offer? Would anyone even wear it?

Next to the suits, I have a bag with pretty dresses, at least one of which I bought in 1991 before I left Japan—before I moved away to take the job the tobacco-colored suit had gotten for me.

Maybe if I lose a little weight, I can wear the dress again.

There are two shin-length cotton shifts that my sister Beth gave me.

One is aqua green, the other purple. I remember how pretty she looked wearing them when she traveled with me in Japan during the summer of 2006—so elegant and slender.

She gave them to me when she retired.

“I’m not going to need dresses like these anymore,” she said.

She cleaned out her closets and gave away the things that were no longer needed in her new life in the mountains.

I should do the same.

Lately, I’ve been looking through that closet trying to decide what to give away and what to keep.

I’ll keep my sky-blue academic vestments from Columbia University. I may have a chance to wear them again.

I’ll keep the pretty frock I bought in Japan, too, for no reason other than it makes me happy.

The tobacco-colored suit will stay with me a little longer.

It connects me to my mother, to that shopping trip we made together, to the dreams she held for me—dreams so precious she was able to spend more on one suit than she’d likely spent all year on clothing for herself.

The post The Tobacco-Colored Suit appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

May 7, 2025

“New and Substantial Evidence”: Surviving a Negative Tenure Decision

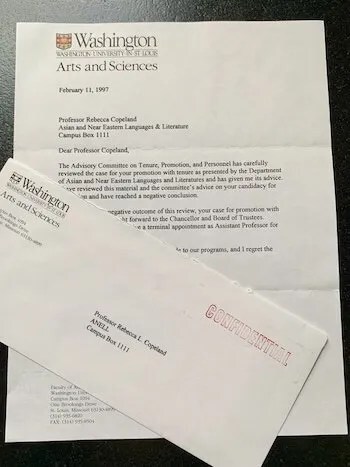

“I don’t understand,” I said, as I read the letter a second time.

It was short, barely two paragraphs.

“We don’t understand, either,” Peter, the chair of my department, said as he turned to close the door to my office.

The room was small and with all my books, dictionaries, desk, filing cabinets, and computer stand, there was hardly space for an extra chair. The one I had—for students—was covered with my coat and scarf.

It was the middle of February, and in typical St. Louis fashion, cold and grey.

Peter stood, his hand on the doorknob.

“But it doesn’t make sense.” I scanned the letter one more time. Had I read it wrong?

The letter was from the dean.

I have reviewed this material and the committee’s advice on your candidacy for promotion and have reached a negative conclusion.

“Wait. So, I didn’t get tenure?”

“No.”

Did he mean, “no, that’s not right, you got tenure.” Or, “no, you didn’t get tenure.”

Did he mean, “no, that’s not right, you got tenure.” Or, “no, you didn’t get tenure.”

My head was swimming. I could see the words on the letter, but I couldn’t really put them in order.

It was as if my ability to read English had suddenly evaporated.

“You said I had a good case,” I mumbled mystified.

“You did have a good case. I mean, you do,” Peter groped for the right words. “We don’t know what happened.”

“And what about the others?”

Two other assistant professors in the department had gone up for tenure at the same time as me.

“They got it.”

“They got it,” I echoed. “That’s good.”

“I know this is hard to process,” Peter said, returning to chairspeak. “I’ll leave now, but we can discuss it later. I’m talking with the other senior members of the department to see what options we have going forward.”

I don’t remember what I did after he left.

I don’t think I cried.

I imagine I sat in my office for a bit trying to figure out my exit strategy. I mean, my exit from my office to my car. I wanted to go home. I wanted to hide.

I didn’t want anyone to see me.

What would they think? Would they know?

In the weeks to come, it was difficult to muster the energy to continue teaching. I didn’t want to interact with anyone. I imagined myself a walking wound.

I had no choice, though, and so off I went every other morning or so, to my office, to classes, to rooms with other faculty.

I felt as if I had “loser” branded on my forehead.

Some people averted their eyes when they saw me in the hallway. Or so I thought.

I remember Van told me how he had struggled with the news of his own negative tenure case.

“I puttered in my backyard for an entire year, like Yasuoka Shōtarō’s father.”

The department had supported my promotion enthusiastically, and I’d been told my external letters were uniformly strong.

One senior colleague had also experienced a negative decision and had fought back. He gave me a plan of action.

“I would make an appointment with the dean,” he told me, “not to argue but to seek information.”

What was the rationale for the decision; and what was the vote?

Following his advice, I learned that the tenure and promotion committee had found my scholarship lacking.

I only had one book.

And that book was on a woman writer they’d never heard of. Moreover, many of my publications were made up of translations. At the time, translations were not evaluated highly—irrespective of the significant amount of research many of the translations required.

Of course, a dossier of one book and an assortment of articles was typical of successful promotion cases in my discipline.

For some reason, though, the committee believed that I was hired on the basis of the book I had in preparation when I started working at the university—The Sound of the Wind: The Life and Works of Uno Chiyo. That meant that I was expected to produce a second book, whereas my peers were not.

This reason may have made sense if I’d been hired as an advanced assistant professor, but I was not. I was given an entry-level salary when I joined the faculty, and my five years teaching at International Christian University were not taken into account.

The vote, I was to learn, was four in favor of tenure and three against. The dean made the ultimate decision.

From my discussion with the dean, I understood that I could ask to be considered for promotion the following year, if I could provide “new and substantial evidence” of additional research.

As luck would have it, I was shortly to learn that I had received a Japan Foundation Research Grant, which would allow me to spend time in Tokyo doing the archival work I needed to do to complete my work in progress. Lost Leaves: Women Writers of Meiji Japan, was already under contract with the University of Hawai’i Press, which had published my earlier monograph.

Shored up by emails, letters, and phone calls from friends and former students around the world, I forced myself to attend the tenure party the department threw for my two colleagues. I wanted to celebrate them! I just worried that my presence would be a wet blanket.

The last thing I wanted, though, was for people to look at me with pity. I wasn’t pathetic. I had been misjudged, and I was standing up for myself.

I wasn’t a walking wound.

After a few “there, theres,” and whispered regrets, most people just let me go about my business.

I spent the summer and fall in Tokyo, affiliated with Kokugakuin University, digging deep into the archives, and writing, writing, writing.

By the end of the fall, I had a complete manuscript.

I also had another contract from Hawai’i for the edited volume that would become known as The Father-Daughter Plot. Eventually, I would ask Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen to join me as co-editor.

“New and substantial evidence”? I thought I had it in spades.

On January 12, 1998 I received another letter from the dean, this one even shorter.

I am pleased to report that acting on the recommendation of your department and with the advice of the Advisory Committee on Tenure, Promotion, and Personnel, I have decided to forward to the Chancellor my recommendation that you be promoted to the rank of Associate Professor with tenure effective July 1, 1998.

Later I would learn that even with the amount of new material I had provided, two members of the promotion committee STILL decided to vote against my tenure. This time, however, the dean made the decision to put my case forward anyway.

My meeting with him, perhaps, had made the difference.

He and I would go ahead to have a good working relationship. I became the Director of the East Asian Studies Program. I wrote a grant that brought the university $1.3 million for East Asian programming, and once I was promoted to Full Professor, I took on the role of Associate Dean of University College and Director of the Summer School. Following that, I was chair of the department for two terms.

Eventually, I would spend three years on the Tenure and Promotions Committee myself.

I share the above account here—not to complain (though I may have complained just a little); not to humble brag (though I AM proud of my fortitude); and not to suggest that my scholarship in anyway deserved the disregard it received from the tenure committee (who, after all, were from entirely different disciplines with absolutely no understanding of Japan).

What I hope readers will take away from this account is that others don’t define us. Our career does not define us. If for some arbitrary reason, we don’t make the cut by whatever evaluation system we are measured, it’s not a true indicator of our worth.

Know who you are. Be true to yourself.

Postscript: The photo opening this post is by David Kilper, then a staff photographer at the university. The photo originally appeared in this article about me, written by Gerry Everding in 2003, twelve years after I joined the faculty at Washington University in St. Louis.

The post “New and Substantial Evidence”: Surviving a Negative Tenure Decision appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

April 23, 2025

A Walking Target: Dealing with Negative Book Reviews

“You must feel like you have a target on your back,” Van said to me as soon as he saw me in the hallway. I had just stepped out of an academic panel and was making my way to the next one on the schedule. The Association of Asian Studies was always hectic, with people dashing down narrow corridors, calling out to old friends, and trying to make new connections.

“What do you mean?” I asked, puzzled. Had I leaned back on wet paint or something? I twisted to try to look over my shoulder.

“Oh, you haven’t seen it yet?” Van looked uncomfortable.

“Seen what?”

I came to a halt right in front of him, my head cocked in bewilderment.

“Danly reviewed your book.”

“Really? Danly?” my heart soared.

Robert Lyons Danly was the author of In the Shade of Spring Leaves, a beautifully poignant biography of the writer Higuchi Ichiyō who died much too young. The biography was amplified by several of Ichiyō’s stories, elegantly rendered in English translation. No wonder it had won the National Book Award for translation in 1982.

Danly had been my polestar. I had set my own book, The Sound of the Wind: The Life and Works of Uno Chiyo, to follow in his wake.

“It’s not good,” Van said, avoiding my gaze.

“You mean, it’s a bad review?”

“Yes. What did you do to him?”

“What?”

“I mean, you must have done something to anger him.”

“I’ve never met him in my life!”

I began to search the furthest recesses of my memory. Had I ever had any interaction with Danly? And how would an unknown, untenured person like me even meet one of the leading lights of the Japan program at University of Michigan?

“He attacked you. Really, it’s practically ad hominem.”

I suddenly felt dizzy. My face flushed and my scalp tingled. I began to feel as if there just might be something on my back. I could feel the weight now, pressing in between my shoulders.

Van must have noticed my discomfort.

“Don’t worry about it. Look, your book is good. Who cares what Danly wrote?”

The next panels had started, and the corridors suddenly cleared. Van dashed into a meeting room, leaving me standing there alone with tunnel vision and ringing in my ears. I made my way back to my room in the hotel.

I can’t remember what happened next. It was 1994. I couldn’t just pull up a review on my smartphone or even on a hotel computer. I had to wait until I returned to my campus.

The wait was agonizing, even though Van and my other friends tried to cajole me. When I finally found the review in my university library, I was crestfallen. And once again my face flushed, scalp tingled, and I felt the target weighing on my back.

I must have written my former professor, Edward Seidensticker, about it. I have a letter from him dated December 12, 1994 in which he writes:

I hope that you do not worry hugely about the Danly review. It is the sort of thing anyone could say about anything, and of course his strictures against biographies of Japanese subjects presumably cover his own biography of Ichiyō. As to whether or not they are meant to cover mine of Kafū, I could scarcely care less. . . .

And when will the matter of your tenure be decided? I have a feeling, somehow, that your book will be adequate. Not at all dissimilar books are what got Danly…tenure…. I can think of plenty of publication records less substantial than yours that have sufficed. I wish you the best of luck, in any event.

Letters to the author from Edward Seidensticker

Hearing from Professor Seidensticker made me feel much better.

In the back of my mind, though, I couldn’t help but think that I deserved the negative review. Not that I believed my work was lacking. Rather, I thought the review was karma.

I was being paid back for a bad review I had written years ago.

In 1987 the Japan Quarterly ran my review of book that included a lively, highly readable translation of a 19th-century work along with an informative and carefully resourced introduction. It was a good book, but my review was inappropriately condescending and glib.

It was my first review.

I was a year out of graduate school and full of myself.

Besides, I was inspired by the snarky reviews I had been accustomed to reading in the Journal of Japanese Studies and elsewhere. In those journals, there were often wars of words among such luminaries as Donald Keene, Joyce Ackroyd, and others.

Of course, my mentor, Edward Seidensticker, was not one to pull punches either.

I thought a book review was supposed to be barbed.

And I went to town.

Given all the things I’ve saved over the years, all the letters and drafts of manuscripts, you would think I’d still have that review. I may. I just don’t feel like looking for it.

I’m ashamed of it. And I’m ashamed of myself for writing it.

The translator was rightfully aghast.

He wrote to the managing editor of the Japan Quarterly to complain.

I don’t have that letter, either, but I do remember he pointed out that despite all the petty criticisms I compiled, I actually seemed to like the book. And, he wasn’t wrong. I DID like it. I just didn’t allow myself to admit it. At least not effusively so.

“Who the hell is this Rebecca Copeland, anyway?” the translator asked in so many words. He wanted to know what qualifications I had to review his work.

It was a fair question.

The journal, though, stood behind me—and more so behind their decision to invite me to do the review—and refused the translator’s request for a redaction. They did not publish his grievance. And so he and I did not enter into the kind of public sparring I had witnessed between Keene, Ackroyd, and others.

That’s why when some of my peers suggested I take Danly to task for his overly critical review (he closed his comments by challenging me to “get a life”), I demurred.

It was karma.

I do not know what became of the translator. I always wished I had apologize to him.

I do know that I have made sure my graduate students know better than to follow in my footsteps. They all want to write book reviews—and editors are constantly asking graduate students and recent postdocs to do so—as they offer the opportunity to publish. (More established scholars often decline book reviews as they carry little weight when it comes to tenure decisions or promotions.)

It can be a dangerous proposition. Junior scholars can end up antagonizing a person who could conceivably head their hiring or fellowship committee or who might review their book manuscript for that coveted first book publication.

There is a silver lining here, though.

Laughing with friends over drinks at conferences, we regale each other with choice lines from our worst reviews. I mean, has anyone else been told to “get a life”?

Funny how we remember the worst, not the best.

Snark stays with you.

Bonding over our shared experiences, we venture to admit when our own reviews missed the mark. We were too green or too harried or just trying too hard to sound like a smart(ass) academic.

Seidensticker was right. Danly’s review did not end my career, and I still do admire his book, even assigning his translations in class from time to time.

I admit to enjoying a bit of schadenfreude, though, when a scholar I admire took Danly’s biography of Ichiyō to task recently for perhaps being a bit too inventive, too eager to “get a life.”

The post A Walking Target: Dealing with Negative Book Reviews appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

April 9, 2025

“To Kill Off the Market”: Puppets, Novels, and Other Curiosities

“It is just too long and it will be too expensive and it will kill off the market,” Peter wrote to me about my manuscript.

His tone was brutal, and so was his prediction. No writer wants to “kill off” their market.

At long last Peter and I had secured a contract with author Uno Chiyo and agent Akiko Kurita for the translation of The Story of a Single Woman (Aru hitori no onna no hanashi).

Now Peter was working with Bill Hamilton, the director of the University of Hawai’i Press on potentially publishing my manuscript The Sound of the Wind: The Life and Works of Uno Chiyo, in the UK and Europe.

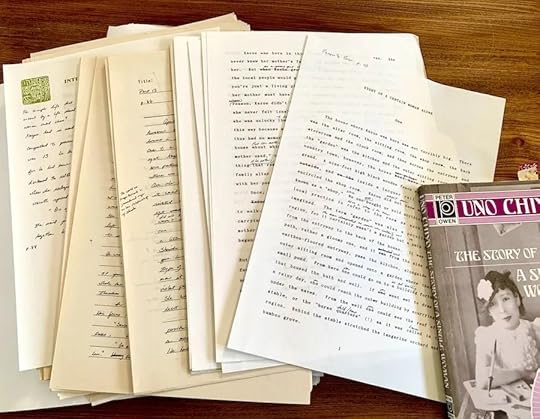

The Sound of the Wind, which I had already contracted with Hawai’i to publish, featured translations of three of Uno’s stories and a substantial biography. With an eye towards his market overseas, Peter worried that the biography was too “academic.” He was particularly unsettled by the inclusion of “The Puppet Maker: Tenguya Kyūkichi” among the three stories, as he felt it didn’t “fit.” Both the lengthy biography and the puppet maker’s discourse on art were “market killers”!

Initially, I had sent my manuscript to Tuttle, thinking only to publish the translation of the novella The Sound of the Wind (Kaze no oto). I worked with Ken Mori, who was then an editor—he’s now the President—and he was very kind to me. (I think at the time, he went by Ken Mori Wong. Or, maybe that was a different Mori.)

He marked up a few pages of my translation, pointing out where I needed to re-structure my sentences so that they were more naturally English and less obviously “translated.”

Draft of The Sound of the Wind opening pages with Ken Mori’s edits.

“Opening gives reader strong impression of voice of narrator—try to match that style and consistency in English,” he wrote by hand in the margins of the typed manuscript I sent him.

If I recall, we met in person to discuss the project, and he sent me home with one and half pages of handwritten comments.

He declined to pursue publication, but the time he spent with me and the advice he offered were invaluable.

I took his comments to heart, tried to make my translation more natural, and then turned to the University of Hawai’i Press. I knew they planned to publish Phyllis Birnbaum’s translation of Uno’s 1935 novel, Confession of Love (Irozange, 1989), and I thought they might be willing to follow it up with another Uno book.

I was right.

Stuart Kiang responded to my query letter, surprising me by suggesting I be more ambitious.

“Why don’t you include an extensive biography?” he wrote. “And add more translations.”

I was delighted by the suggestions.

Now my book would resemble Robert Danly’s study of Higuchi Ichiyō, In the Shade of Spring Leaves, which had come out in 1981. I had read that volume cover to cover and was keen to model my own book after his.

(Which is somewhat ironic, since when Danly reviewed my book several years after it was published, he trashed the format—and pretty much everything else about my work: “If Copeland’s book is a worthy successor to the life-and-works tradition, this very succession begins to make one yearn for something new.” Ouch. Even after all these years, it still stings.)

Of course, when I began preparing my book for Hawai’i, I was completely unaware that I was dragging around a tired “life-and-works tradition”! I selected the three works because I thought they represented the diversity of Uno’s writing styles and nicely amplified important moments in her career.

The first selection, “This Powder Box” (Kono oshiroi-ire, 1967), a fictionalized memoir, returns Uno to her memories of Tōgō Seiji and the tumultuous love affair they had in the 1930s. I thought the story would interest readers of Uno’s Confessions of Love, which follows Jōji, who we are meant to understand is modeled on Tōgō, through his love affairs with three women.

The Sound of the Wind (Kaze no oto, 1969), the longest in the collection, is set in an earlier era—before Japan modernized—and provides a fascinating companion piece to Uno’s Ohan (1957), which many consider her masterpiece.

Ohan (translated by Donald Keene in 1961) is the story of a hapless man who leaves his wife and child to live with a geisha. Seven years later, he unexpectedly meets his wife while out for a stroll and finds himself drawn to her again. The narrative, told in the man’s voice (as was Confessions of Love), describes his inability to settle with either his wife or his mistress. He loves them both.

The Sound of the Wind offers a wife’s story. Osen is married off to Seikichi, the ne’er-do-well second son of the Yoshino family, when she is just a girl. “Married off” isn’t the right word. He is brought into her family as the adopted husband and behaves just as he pleases, squandering the family money on racing horses and a geisha named Oyuki. Despite the humiliation he brings to her, Osen is irresistibly drawn to Seikichi. She is even attracted to Oyuki herself.

Like Ohan, the story is narrated in dialect. Ohan, Uno contended, was told via a dialect she had concocted herself, a blend of speech patterns from different regions in the Kansai. The story reverberates with the traces of the gidayū chanter, and in fact, the novella was adapted and performed in the puppet theater.

The Sound of the Wind uses the Iwakuni-dialect Uno spoke as a child. Whereas Ohan took her ten years to write—so meticulous was Uno in crafting her dialect—The Sound of the Wind was much less involved.

At least for the author.

For me as translator it took considerable effort to try to suggest the flavor of the regional tones—and also of a bygone Japan—without resorting to hackneyed phrases or my own familiar accents.

I remember showing my sister Beth one of my early drafts and she told me the characters sounded like they were straight out of Mayberry—a reference to the TV show we watched as children starring Andy Griffith as a kindly sheriff in small-town North Carolina.

It was Beth who suggested I romanize certain Japanese words—like Okaka, instead of using the English equivalent, Mama—to help break the spell of the American South while also retaining something of the Japanese accent.

Working on The Sound of the Wind that year in Tokyo was magical. Some days I would visit with a Japanese neighbor, Mrs. Higashi, who was married to a physics professor at ICU to ask her about passages I didn’t understand. I loved listening to her read the passages aloud to me.

My third selection, “The Puppet Maker” (Ningyōshi Tenguya Kyūkichi)—the one that Peter wanted to delete from the UK version of the work—was similarly narrated in dialect and was a work Uno wrote in the early 1940s, some years before she began writing Ohan.

The story is narrated in the form of an interview, with an unnamed woman from Tokyo speaking to a venerable puppet maker in Tokushima about his art.

The woman, a reflection of Uno herself, chances upon a puppet on display at her editor’s house and decides then and there she must learn more about the carver. She knows nothing of the puppet theater and although she is Japanese herself, she feels as if she were entering an entirely foreign world. She speaks to the puppet carver in standard Japanese. He responds in Tokushima dialect.

Here Uno captures for readers another male narrator. Over the span of her career, she wrote a number of stories from the perspective of a male character, which is unusual among women writers.

I thought it was important to highlight this work for that reason, but also because it so brilliantly captures the encounter between cultures—the fast-paced, urbane world of mid-20th century Japan, as represented by the woman, and the sepia-toned world of an art form slowly slipping into the past. Uno crystallizes this world, just before it disappears forever.

Peter Owen didn’t see the importance of the work, though:

I have looked at THE PUPPET MAKER story again and I have discussed it with my people here. We . . . would prefer to do the two stories without THE PUPPET MAKER, as that way there would be two stories with autobiographical themes. If we did the three it would then be a volume of stories which is a bad sales pitch and also THE PUPPET MAKER is completely different material – it’s really an interview which she did with someone and doesn’t relate to her life at all.

I found it interesting that Peter considered the novella, The Sound of the Wind, autobiographical but not “The Puppet Maker.” The former was loosely based on Uno’s memories of her father, but it was highly stylized. The latter, of course, was derived from meetings she had with the puppet carver, Tenguya Kyūkichi, in Tokushima, but it also carried deep resonances about Uno’s own regard of art—of HER art—and not just the art of carving puppet heads.

The work was deeply personal. Perhaps even more so than The Sound of the Wind.

In the same letter Peter acknowledged a potential future for the story:

If the two stories sell we might perhaps do THE PUPPET MAKER on its own as a paperback with illustrations, but our feeling at the moment is that Chiyo is not well enough known outside Japan to do that on its own at the present. It is very much a curiosity and Japanese material and would have a limited appeal in my opinion here and in Europe.

In hindsight I see that for Peter, Uno’s attractiveness was her sexuality, her many romances and her eagerness to sensationalize them in print. Sexy Uno was someone he could market as scandalous and insouciant, a rule-breaker and trail blazer, “Japan’s Colette.”

Her more sober rumination on art in “The Puppet Maker,” written during the dark days of the Pacific War, was a hard sell.

“Thank you for your letter of 30 January,” I wrote to him meekly on February 27, 1991. I was eager to get the contract for the UK book project underway.

“As concerns your decision to exclude “The Puppet Maker” from the book published in the UK, I have no objections. Of course, from a literary point of view, this is one of Uno’s finest works. But you know your readers, and since the work will be published elsewhere, I do not mind terribly.”

In the end, Peter published the Hawai’i book with all three stories and only slight changes to the introduction. The most substantial change was to the title: The Sound of the Wind: A Biography by Rebecca Copeland with Three Novellas.

In the end, Peter published the Hawai’i book with all three stories and only slight changes to the introduction. The most substantial change was to the title: The Sound of the Wind: A Biography by Rebecca Copeland with Three Novellas.

Over the years I have read “This Powder Box” in translation with students; but it is “The Puppet Maker” that is the most versatile. I require it in courses on theater, translation, war writing, and women’s writing. Students find it exceptionally moving.

When Uno wrote “The Puppet Maker” there was some fear that Kyūkichi’s art form was soon to disappear. He had no true heir and the world—rocked by war—was changing. In her narrative, she preserves the old man’s voice, his memories, his reflections on his craft and in this way ensures that they all endure as long as readers read.

Perhaps then Peter’s instincts about publishing this work in a standalone volume was right all along. I can imagine a book with a generous introduction to Tokushima and the puppet theater, Uno’s beautiful story, along with glossy photographs of Kyūkichi’s works.

It’s not too late!

The post “To Kill Off the Market”: Puppets, Novels, and Other Curiosities appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

March 26, 2025

Flurry of Letters: Translation is more than Words

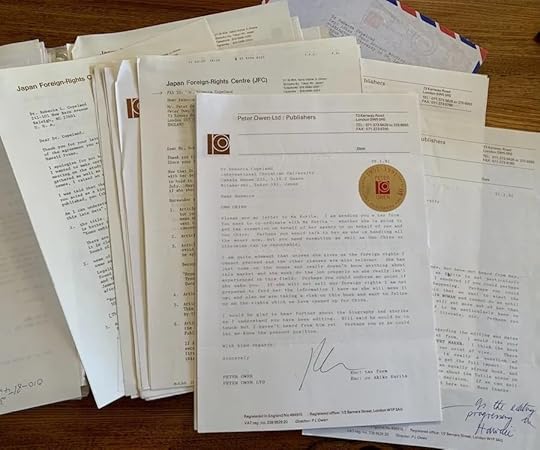

A flurry of letters followed the November 1990 meeting with Akiko Kurita, Fujie Atsuko, Peter Owen, and me. All were focused on reaching an agreement so that I could begin translating The Story of a Single Woman. Peter wanted all the rights to translations into other languages. Ms. Kurita claimed to have already sold the rights to another translator in France, and later Peter and I learned the same had happened with the rights to German, which made Peter very cross.

What did it even mean? I wasn’t sure.

And the back-and-forth was not limited to the contract I was then negotiating with Peter. Apparently, the contract I had earlier acquired with the University of Hawai’i Press was also on the table.

Not understanding why that would be, I followed up with Ms. Kurita.

November 29, 1990

Ms. Akiko Kurita

Managing Director

Japan Foreign-Rights Center

27-18-804, Naka Ochiai 2-chome

Shinjuku, Tokyo 161

Dear Ms. Kurita:

It was a pleasure to meet you the other day in Uno-Sensei’s apartment. As per our subsequent discussion on the phone, I agreed to send you a copy of my contract with the University of Hawaii Press. However, now I am wondering what the rationale for this is. (In my excitement, I apparently forgot to ask you! Or, perhaps you explained but I failed to understand. That occasionally happens, too, I’m afraid.) Since the book I am writing for the University of Hawaii Press has absolutely no connection, that I can see, with the book Mr. Peter Owen is proposing, I’m still unclear as to why my contract with them is important to our discussion.

As the letter continued, I launched into a defense of Peter and his motives. I could tell from our earlier meeting that Ms. Kurita found him distasteful. I worried that his brazenness would sour our chances of securing the contract to translate The Story of a Single Woman.

Mr. Owen is a shrewd publisher. He knows his audience very well. But more than that, he is also dedicated to presenting to English audiences the best writers of other lands, and most of the works that he publishes are translations. As Endo Shusaku has stated: “Peter Owen is an excellent discoverer of the hidden novels around the world and he encourages them to grow.”

I would like to be part of that process. And, I would like to proceed with this book (Aru hitori no onna no hanashi)…

Kurita responded (December 4, 1990). First she explained why she needed to have a copy of my contract for the Hawai’i book, which would include translations of three of Uno’s stories. I had met Uno earlier and had secured her permission. At the time, I had thought that was proper and sufficient. Ms. Kurita let me know it was not.

Dr. Rebecca L. Copeland

INTERNATIONAL CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY

Mitaka, Tokyo

Dear Dr. Copeland,

Mrs. Fujie asked us to handle all foreign rights negotiations on the works by Uno-sensei retroactively, as she has no records at her hand. Uno-sensei and herself always said ‘yes’, ‘yes’ to everybody who asked to publish or translate. She recalls she received one copy in English, but not any income from these deals. (In fact, I think she does not remember what have been done in the past, as she expressed herself ‘ōzappa’.)

What Ms. Kurita said made sense. I could just picture Uno Chiyo smiling and agreeing to translations requests right and left without creating any kind of structured agreement. Being easy going (‘ōzappa’) was ever her style.

In response to my accolades about Peter, Ms. Kurita continued:

I agree to your and Mr. Endo’s comments to Mr. Owen in some extent, but I have had bitter experiences with him too. I appreciate his enthusiasm and also your evaluation. And I have no objection of exchanging the contract between the author and Mr. Owen, respecting his desire. But, unless I know the present situation of the works of Uno-sensei, it seems difficult to draw up the contract.

[Written in hand] P.S. Here is a copy from “Practical Guide to Publishing in Japan,” just fyi.

I sent Ms. Kurita my contract.

Peter and Ms. Kurita continued to tangle over the rights for The Story of a Single Woman. Everything he sent to her, he sent to me as well via either a carbon copy, a facsimile, or a newfangled machine copy.

The amount of paper I began to accumulate ballooned with each passing month, and so did Peter’s frustration over the negotiations.

On January 21, 1991 he writes:

I chased Kurita about ten days ago, but have not heard from her, she is waiting for Chiyo, but as Kurita is not particularly efficient or unduly intelligent, I wondered if you could perhaps telephone her to see what is happening.

Finding her somewhat later, he writes directly to her on January 30, 1991:

“Thank you for your letter regarding CHIYO. The agreement is not right and it is not in parts as agreed between us.”

It was on the issue of foreign translations that they tussled.

Peter amended clause 16 in the contract: FOREIGN TRANSLATIONS: “Peter Owen shall handle the foreign and translations rights on behalf of the author and pay to the author’s agent 75% of the net proceeds received by them.”

To me, he wrote on February 25, 1991

“Could you please telephone her to chase her up. I am eager to proceed and if you would like to do it let’s give her a shove. She doesn’t really know what she is doing. I find these Japanese awfully difficult to deal with.”

Clearly, Peter overestimated my telephone negotiating skills.

At this point, I had issues of my own to deal with. My marriage was careening into divorce, and I had just returned from a job-hunting trip to the United States. As a result, I had secured a tenure-track position at Washington University in St. Louis, to start in August, and was now trying to prepare for that.

To relieve my anxieties, I translated.

I had just learned how to use a word processor, and I started typing my translations up that way. Of course, I did not have a personal computer at home. I wrote my translations in long hand on scrap paper, sitting at my dining room table, and then carried the drafts to campus later in the week to transcribe onto the word processor. We used WordStar.

The translation slowly coalesced from the Japanese book, through my hand, to lined paper. The trek to my campus office continued the process as I pictured in my mind the words on the page. Once seated before the computer, the words jumped from scribbled handwriting to a screen with a blinking cursor.

When I wanted to check sections of the translation, I consulted a neighbor, Mrs. Higashi, whose husband taught physics on campus.

I called her my “Iki-jibiki,” my “Living Dictionary.” We’d sit and have tea in her cozy living room and talk about phrases I didn’t understand.

And then, another letter would arrive from either Peter or Ms. Kurita.In a letter dated February 25, 1990 Ms. Kurita responded to Peter’s revised contract, quibbling with some of his changes, including this:

7. Your article 16. Unfortunately, your request is not realistic. As I may have told you when you were in Tokyo, the situation has been changing. It may be that when you had exchanged the contract with Mr. Shusaku Endo, there were not many translators from Japanese to other languages. However, recently, potential translators from Japanese into any other languages have been increasing drastically.

They sometimes translate before having the permission from the author and present the translated ms to the publisher directly. Then, the publisher proposes to the proprietor. Actually, this was happened to this title. We sold the German rights already. (I also explained this to Dr. Copeland.)

We have no way to stop translators from translating the works they like. These matters happen recently quite often not only for Chiyo Uno’s titles but also for other author’s titles. We will certainly inform you if and when the foreign language rights are sold before you publish the English edition.

On March 4, 1991 Peter rebutted Ms. Kurita’s characterization of Article 16:

We want translation rights […]. As far as I can see you are generally not in a position to sell these rights as we are, as we are in constant and close touch with foreign publishers and the publishers to whom we sold CONFESSIONS OF LOVE have been given an option on any of Chiyo books we publish. This seems to be the easiest solution to exclude Germany and give us the right to handle the other rights as per my contract. Please believe that on this kind of book we are taking a risk as the market here is quite appalling and has degenerated again for fiction. I suggest you now draw up a final contract on this basis but including the translation rights except Germany, which you say are sold.

There is no point in your holding on to the rights if you are not in a position to sell them, and I do know that Japanese publishers and agents don’t sell rights and find it very difficult to sell rights from Tokyo, and we do have our publishers lined up for this author.

[…]

Please let us settle this matter quickly to avoid a lot more correspondence and also so that Dr Copeland can proceed with the book otherwise it will never appear.

Ms. Kurita replied in her ever tactful way on March 15, 1991.

May I draw your attention to the fact that we were organized by the investment of various publishers to sell the foreign rights of Japanese publications? You may remember that I lived in Cologne for three years and 1.5 years in London. Thus, I tried to make good relationships with the editors who are interested in Japanese works. I visited many publishers in various cities and regularly attend the book fairs. But, knowing your enthusiasm, I said ‘I will not promote this title’ in other countries. I just worried if you misunderstood [. . .]. I respect your understanding. Thank you.

Remarkably, by mid-March, Peter Owen and Akiko Kurita came to an agreement.

On June 15, 1991, Ms. Kurita wrote to me:

“Finally, we received the signed contract in triplicate, which we are enclosing here… We are anxious to see the English edition of Uno-sensei’s book.”

With a contract safely in hand, I worked feverishly over the next month to finish the translation, wanting to have it completed before starting my new position at Washington University in St. Louis.

My five years working at International Christian University came to an end. A new chapter was to begin.

In the posts ahead, let me share more about my discussions with Peter about what to translate. Later, I will focus on the way translation fit an academic career.

The post Flurry of Letters: Translation is more than Words appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

March 12, 2025

A Gift of a “Lavish Cake”: The Adventures in International Publishing Continue

Fujie Atsuko stood on the genkan step, looking down on Peter and me as we walked into the narrow apartment entryway. The light was behind her making it difficult to read her expression. I noticed another woman just behind her, peering at us around Fujie’s shoulder. Her dark hair was pulled into a low bun. She wore glasses. This, I was to learn, was Akiko Kurita, the Managing Director of the Japan Foreign-Rights Center.

Peter thrust the neatly wrapped package of Baumkuchen cake at Fujie-san and then made to follow her into the apartment. I yanked him back in terror, reminding him to first remove his shoes.

Seeing Peter struggle to reach his laces, and nearly tripping in the process, Fujie sent one of her aides into a back room. The woman returned a few minutes later with a chair, which they set alongside the low paulownia table in the room where Uno Chiyo and I had earlier met to discuss literature, translations, and lovers.

For good measure, they placed a chair there for me, too.

Peter and I both sat, our knees now eye level with Uno Chiyo’s party, who sat on zabuton floor cushions. Uno Sensei, we had been informed earlier, was not feeling well and would not attend the meeting. She had instructed Fujie and Kurita to speak on her behalf.

Peter launched into his requests posthaste

“We want to publish more Chiyo.”

I cringed at the informality and glanced furtively at Fujie and Kurita. Neither blinked. They kept their eyes firmly on our kneecaps.

“We think there’s a market. Let’s start with The Story of a Single Woman and whatever Hamilton’s got planned and take it from there,” Peter continued, referring to William Hamilton, the director of the University of Hawai’i Press. Hamilton had contracted to publish my The Sound of the Wind: The Life and Works of Uno Chiyo, which included translations of three of the author’s stories.

Kurita turned to Fujie and began translating what Peter had just said in a voice too low for me to catch completely—there on my lofty perch.

Fujie responded to Kurita at a similarly inaudible decibel. Neither changed expressions. With faces like that, I thought, they’d make a killing at the poker tables.

“We are pleased to hear of your interest, Mr. Owen,” Ms. Kurita spoke, her English careful and crisp. “Uno Sensei would welcome the opportunity to see more of her works appear in English. We must discuss terms, of course.”

I sighed inwardly with relief. All seemed to be going well, and then Peter jumped in.

“Didn’t we already handle this in Germany?”

Apparently, Peter had met Kurita at the Frankfurt Book Fair earlier in the fall.

“Certainly, we spoke, but nothing was finalized,” Kurita replied rather tartly. “Of course, we must consider the wishes of Chiyo Uno herself.”

Peter grimaced and then pushed ahead.

“Our terms are 75/25, as you well know. I’d like to finalize this before I leave Tokyo. I can have the contract sent over this afternoon.”

The woman who had brought out the chairs returned with a tray of refreshments. She set out cups of steaming English tea before each of us along with our own individual dish of cake—a kind of strawberry glazed cheesecake neatly wrapped in cellophane.

Kurita bowed but made no move to touch what was offered. Peter plopped the sugar cubes into his tea, stirred noisily, and then brought the tea to his lap, saucer and all. He lifted the cup to his lips and slurped happily.

“What, no Baumkuchen?” he asked, turning to me in surprise.

“Um, no…” I started.

“Then why’d we have to bring it?” he looked confused.

“I’ll explain later.”

After gulping down the tea, Peter resumed his “negotiations” until it became clear nothing would be decided today.

We would leave as awkwardly as we arrived.

“What was that all about?” Peter asked as we walked back Omote Sandō. “I just wasted my afternoon and the price of a cake.”

“Not at all,” I tried to explain. “The point of our visit was just to make contact and introduce ourselves to Uno Chiyo’s people. Negotiations will follow.”

Years later, in Peter Owen: Not a Nice Jewish Boy, Memoirs of a Maverick Publisher (2021), Peter would describe the encounter this way:

When it came to bringing out a novel by Chiyo Uno, who was an eminent author and fashion designer, I had wanted to meet her in Japan, but she was in hospital and refusing visitors. She had been something of a beauty and didn’t want people to see her unwell. Perhaps it was fair enough—when we published her famed 1933 novel Confessions of Love in 1990 she was already ninety-three.

Uno was quite a daring and independent woman. Like Colette, whose books I also published, Uno’s life was tumultuous and adventurous enough to inspire vivid and occasionally racy novels and a television dramatisation. I wish I had met her, but just meeting her agent involved quite a rigmarole. Wherever you go in Japan you’re expected to bring a present of some sort. My translator and I bought the agent a lavish cake, but goodness knows what sort of gift grande dame Chiyo Uno would have expected had she agreed to receive us.

I guess that cake gift made a lasting impression on Peter, much as he made a lasting impression on me.

In the months and years to follow, I would find myself caught in negotiations between Ms. Kurita and Mr. Owen. The former was determined to protect the interests of her client at all costs, the latter to develop a market for his client’s works. Neither was ill-intentioned, I believe. But the tension that arose between them—largely catalyzed by their vastly different communicative styles, left me at a loss. I had no experience with high-octane publishers or with legal copyright issues. I just wanted to translate Uno Chiyo’s fiction.

And so I did.

Eventually, Peter and Ms. Kurita and Uno and me and a sundry list of other players would reach an agreement and as a result Peter Owen Ltd published my translation of The Story of a Single Woman.

Working with Peter, despite the uncomfortable beginning, was not only a tremendous learning experience for me, but also remarkably pleasant as time went on. I found him eccentric but also kind in his own way.

In the posts to follow, I will share more of the story behind the Story. What did Peter and Akiko think of each other? What did Peter think of Uno Chiyo’s works? What did I think of translating? What did my employer think of translation?

I’ve been inspired to take this journey through past correspondences and fading memories having learned that Penguin Random House has purchased the rights to my translation and plans to reissue it. The Story of a Single Woman is scheduled for release April 29, 2025.

The post A Gift of a “Lavish Cake”: The Adventures in International Publishing Continue appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

February 26, 2025

“You’ll Need to Bring a Gift”: Baumkuchen Cake and the Wild World of International Publishing

The good news came out of the blue.

I opened my email to learn that Penguin Random House had acquired the rights to my translation, Story of a Single Woman, and were releasing it on April 29, 2025. This was one of my early translations of Uno Chiyo’s fiction and contemplating its relaunch brought back a rush of memories.

How could I forget my first meeting with the legendary publisher Peter Owen?

“You’ll need to bring a gift,” I told him on the phone.

“Why?” he fired back.

“Why?” he fired back.

“It’s the custom,” I said. “It would be rude to show up empty handed.”

I had not yet met Peter Owen (1927-2016), the maverick British publisher renowned for his ability to uncover international writers yet unrecognized in English. He had been the one to introduce Mishima Yukio to English readers when he published Meredith Weatherby’s stunning translation of Confessions of a Mask in 1960. By the late 1970s Peter was working with Endō Shūsaku. I knew Endō’s translator, Van Gessel, who briefly taught at Columbia University and quickly became the favorite professor among my cohort of graduate students. Peter was now setting his sights on acquiring translation rights to Uno Chiyo’s works.

Imagine my delight, then, when I received a letter from the great publisher himself. Would I soon be joining the league of translators that included Van?

12.10.90

Dr. Rebecca Copeland

International Christian University

Canada House 233

3-10-2 Osawa, Mitaka-shi

Tokyo 181, Japan

Dear Dr. Copeland

Bill Hamilton of the University of Hawaii Press, has given me your address and fax.

I am going to be in Japan from November 2nd until November 13th, and would very much like to meet you to discuss your book as we are Uno Chiyo’s publishers and are handling all the foreign rights. I am terribly keen to see her and I have asked my author Shusaku Endo to make an appointment and I will need an interpreter – I believe you know her. Endo would probably give me an interpreter but if you could come along it would help enormously, also with a view to translating more Uno Chiyo books. We could then discuss the books and see which ones we want to buy – we certainly want to go on with this outstanding writer.

I am staying on the Fairmont Hotel in Tokyo and will be there late Friday, November 2nd. Could you perhaps telephone me, or I will telephone you – in the morning, quite early will do, of the 3rd November, when I will know whether Endo has made an appointment, if not, could you make one? The best time for me would be late afternoon, as my appointments at the moment are all channelled to the morning and afternoon, say around 5.00 pm or 5.30 pm, any day would be fine.

I would be very grateful for your help, which will be invaluable.

Sincerely

PETER OWEN

PETER OWEN LTD

Ever on the hunt for a new voice, Peter had stumbled upon Phyllis Birnbaum’s 1989 translation of Uno Chiyo’s Confessions of Love (Irozange, 1935). Intrigued, he followed up with William Hamilton, the director of the University of Hawai’i Press, which published the translation. Since I was then in negotiations with the Press to publish my translations of three of Uno’s stories, along with a substantial introduction (a volume that would eventually become The Sound of the Wind: The Life and Works of Uno Chiyo, 1992), Bill suggested that Peter follow up with me.

I could hardly contain my excitement:

October 22, 1990

Mr. Peter Owen

Peter Owen Ltd: Publishers

73 Kenway Road

London SW5 ORE

Dear Mr. Owen:

Thank you very much for your letter of 12 October. I should be very honored to meet you while you are visiting Tokyo and certainly hope to be of assistance if possible. I will of course be most eager to accompany you to your interview with Uno Chiyo and will gladly serve as your interpreter. However, if you wish to discuss business-related matters in fine detail, you would probably be better served by the interpreter Endo Shusaku provides. The sphere of my linguistic ability is mostly limited to vague discussions of literature, weather and health.

In fact, Peter did not take my advice about the interpreter. When I met him in early November, I was to discover that he was extremely miserly, taking any opportunity possible to cut costs—even while staying in one of Tokyo’s more posh hotels.

I can’t remember what day we met or where. I imagine we met near the subway stop at Omote Sandō, there among the fashionable stores that lined the street—Dior, Gucci, and Louis Vuitton. After a quick greeting, we began our journey to Uno Chiyo’s apartment in Minami Aoyama San-Chōme on foot. Far cheaper to walk than take a taxi.

I do remember being dismayed by Peter’s appearance. His face was grizzled—had he forgotten to pack a razor?—his jacket rumpled. I suspect his shirt would have been equally wrinkled had it not been stretched so tightly across his impressively round belly. His tie, which carried the remainder of his breakfast, was too short, exposing a missing button on his shirt below.

This was the illustrious publisher? The discoverer of unknown talent?

It wasn’t his appearance that nettled me, though, it was his attitude.

“Did you bring a gift?” I asked, noticing he carried nothing.

“No.” he answered testily.

“Then let’s stop here and buy a cake.” I pushed the door open to a small shop that sold Baumkuchen goods. Even though we selected the smallest one they had, Peter still grumbled as the shopkeeper wrapped the gift.

“She should be paying me!” he sniffed as he begrudgingly handed the clerk the money. (I had stubbornly refused to open my wallet when I translated the amount for Peter.) “I’m the one doing her a favor,” he added

I can’t remember if I recited the rules of etiquette to him again or if I took another look at his soiled tie and thought the better of it. I did begin to feel a knot of dread in the pit of my stomach, wondering what kind of trouble I may be stirring up.

My anxiety loomed larger the closer we drew to Uno’s apartment.

“So, who are we meeting?” Peter asked.

We already knew that Uno Chiyo would not be joining us. At 93 her health was occasionally precarious, and I was aware that for some time she had been suffering from gikkuri-goshi, acute lower back pain.

“As I understand it, Ms. Fujie will be responsible for the negotiations.”

“Such a pity. I was hoping the meet the grand dame herself. Then again, I imagine she’s not as beautiful as she once was. Who’s this Fujie?”

“She’s her secretary and assistant. They live together.”

I probably shouldn’t have added the last part. Peter nearly stopped in his tracks and turned to me asking, “Oh, are they dykey?”

“What?”

At first, I hadn’t quite caught what he had said. Perhaps it was his accent but more likely it was because I couldn’t associate Uno in an intimate relationship with her secretary. More than a business associate, Fujie was like a daughter to Uno. Then I understood. After Confessions of Love, Peter had pegged Uno as the “next Anais Nin” or the “Japanese Colette.” He wanted there to be salacious sex. And maybe there had been at one time in Uno’s past, but my god, the woman was 93 with chronic lower back pain.

“No, not at all.” I could hardly conceal my disgust—not with what Peter had said so much as the way he had said it. “Both Fujie and her husband, who is a photographer, live with Uno and help her. They’re her family.”

Should I turn around right now? Was this translation worth it?

Uno Chiyo was my author. I had worked hard to cultivate a relationship with her, and I felt responsible for her trust. I did not want to insult her by introducing a publisher to her who would brashly push through with business negotiations at best and insult her at worst.

I needn’t have worried, though. When we reached her apartment, I discovered that Fujie Atsuko, like the steadfast assistant and loyal guard she was, had engaged the services of Akiko Kurita, Managing Director of Japan Foreign-Rights Centre (JFC) and not one to suffer fools lightly. No one would pull the wool over the eyes of those two women. They were prepared for Mr. Peter Owen.

More so than I had been. My adventures with Peter Owen were only just beginning.

In the end we managed to have a cordial and mutually rewarding business relationship. It is thanks to Peter, after all, that I am now celebrating the re-release of my translation of Uno Chiyo’s The Story of a Single Woman.

In the posts to follow, I will share some of the stories behind the Story. Stay tuned!

The post “You’ll Need to Bring a Gift”: Baumkuchen Cake and the Wild World of International Publishing appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

February 12, 2025

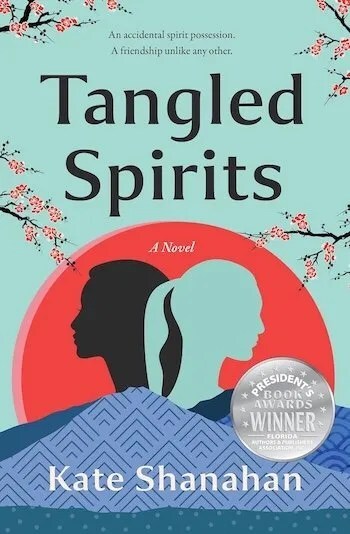

Traveling with Tangled Spirits: A Book Review

What would you do if, for absolutely no fault of your own, your spirit slipped away from you and ended up in someone else’s body? And not just any body, but a 10th-century woman from Japan?

That is just what happens to Mina Cooper, a 20-year-old American college student studying in Japan.

Reeling from her American boyfriend’s infidelity and feeling a wave of doubt about her decision to major in Asian studies, she decides, uncharacteristically, to take a solo hike on Mount Tsukuba in Ibaraki Prefecture.

Not being very outdoorsy, she soon loses her path but ends up meeting a very handsome Japanese man named, Kenji, who smells slightly of cinnamon and has a voice like smooth jazz.

Kenji leads her to a “power spot” near a shrine and instructs her in meditation.

The next thing Mina knows she is wearing long red hakama trousers and a white kosode gown—just like a miko or shrine maiden. She tries to move but cannot. She calls to Kenji but makes no sound.

Instead, she hears a woman say in somewhat of a panic that she has opened a path to the spirit world and has seen a hungry ghost.

Mina realizes to her horror that SHE is the hungry ghost and that she has entered the body of Taira no Masako, a Heian-era lady of the fifth rank, in training to become a miko.

Masako tries to dislodge Mina’s spirit but cannot. Her maid, Yumi, advises her to seek an exorcism. Mina manages to break into Masako’s consciousness and begs her not to, as she is afraid doing so will strand her spirit forever in limbo.

And so begins Kate Shanahan’s delightfully inventive novel, Tangled Spirits (2022).

Mina, Masako, and Yumi travel by oxen cart from Hitachi (present-day Ibaraki) to the Heian capital (Kyoto), in an effort to seek counsel from famous court wizard, Abe no Seimei.

15th-century image of Yin-Yang Master, Abe no Seimei. Unknown artist. Wikimedia Commons.

Once in the capital, Masako (through strings pulled by her father and his relatives), is named the Imperial Medium, and is placed in the court of Empress Sadako. Heavily pregnant with her second child, Sadako is susceptible to possession by restless spirits. Masako is responsible for keeping her safe.

As luck would have it, Mina has studied Japanese history. She is able to coach Masako, who is asked to read turtle shells and divine the future.

For example, she knows that Sadako will give birth to a son and tells Masako as much. When Masako’s “prediction” comes true, the Imperial Medium earns considerable clout at court.

Knowing the future isn’t all fun and games, of course. Mina recalls that Empress Sadako’s conniving uncle, Fujiwara no Michinaga, will eventually usurp her power by having his own daughter, Akiko, named as the Junior Empress. Sadako will die in isolation.

Should Mina warn her?

This isn’t the only dilemma Mina confronts.

She and Masako don’t always see eye-to-eye. They have heated word battles with one another—all telepathically inside Masako’s mind—with no one else the wiser. Masako is naïve and trusting. Mina is eager to ingratiate herself with the wizard, Seimei, as she believes he is the only one who can send her spirit back to the 21st century.

Occasionally, Mina hijacks Masako’s body when her host is asleep. Only then can Mina make her arms and legs move of her own accord. In the process, Mina manages to engage in all kinds of faux pas. She walks too quickly, she stares at people too directly, and once, when trying to conceal her identity, she grabs a fan to shield her face only to learn that the color of fan she selected was reserved for the highest ranks.

The two women must learn to work in tandem, and not at cross-purposes, if they will achieve their goals. They also have to take care not to become too dependent on each other.

If their spirits “bind,” they will be forever entwined.

The adventures that Mina and Masako encounter are charming. They spend an evening enjoying a poetry contest, for example, they travel to the Kamo Shrine. Of greatest interest is their encounter with Sei Shōnagon, who occasionally reads from her Pillow Book.

Mina indulges in some major fangirling when she’s alone with Sei, letting her know that she will be famous and will pioneer a new literary genre. She refrains from disclosing the fate of her empress, however.

Murasaki Shikibu even makes a cameo appearance in the tale.

Despite the (likely?) fiction of a traveling spirit, the story hews closely to a historical timeline of events.

Author Kate Shanahan earned an MA degree in Asian Studies from the University of Michigan, and her novel reveals careful research. She weaves wonderful historical information into her narrative—covering birthing rituals, religious practice, poetry compositions, and more. And she does so without coming across as pedantic or boringly erudite. She stays true to Mina’s guiding spirit—describing even the most exquisite court ritual with the vocabulary of a Gen-Zer.

In fact, the novel is rich with zingers and jokes. I had a big laugh when Mina finally realizes she has ended up in the Heian era. On the one hand, she is worried that she may never return home.

On the other hand, this could be an honors thesis goldmine, to be able to learn what happened to Sei Shonagon in a way that no scholar would ever be able to do. I could get a Ph.D. out of this. ‘Youngest-ever professor of Japanese Literature’ might change my mother’s mind about my major.

Tangled Spirits is a fun read, sending us on a fantastic adventure into an imaginary past. For me the fun is heightened by all the fabulous Heian-flavored detail: the colorful layering of silken sleeves, the poetry competitions, the momentary terror of an unleashed shikigami spirit.

Tangled Spirits is a fun read, sending us on a fantastic adventure into an imaginary past. For me the fun is heightened by all the fabulous Heian-flavored detail: the colorful layering of silken sleeves, the poetry competitions, the momentary terror of an unleashed shikigami spirit.

More than that, though, the novel delineates a young woman’s journey (both in the 10th and the 21st centuries) into self-reliance and confidence.

The post Traveling with Tangled Spirits: A Book Review appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 29, 2025

Teaching Tips: The Three Most Important Steps to Take Before Class

“I’ll let you in on a secret,” Dennis said, his eyes sparkling.

We’d been talking about teaching. I’d only been in my post at International Christian University for a year, and I lacked confidence. I’d prepare my lecture for hours on end, and then the day of my class, I felt I was barely coherent.

“You want to know the three most important steps I take before each class?” he asked.

I leaned in, ready for his words of wisdom.

I had seen Dennis teach. Here at International Christian University, he was an Assistant Professor of Economics.

He was a natural.

He walked around the room, barely glancing at his notes—if he even had any—introducing important concepts, drawing on current events, telling jokes. His students were riveted, following him with their eyes, laughing at his punch lines.

He came alive in the classroom. His voice loud with confidence.

“Supply and demand….”

“Externalities….”

“Indirect taxation….”

He broke things down in a way even I, a non-social scientist, could understand. If I were still a student, I’m sure I’d want to take his class.

“Please, tell me,” I encouraged, not quite yet catching onto Dennis’s game.

“The three most important steps I take to prepare for a class are the steps I take to reach the podium.”

Ba-dum dum!

Dennis told dad jokes before dad jokes were even a thing.

I groaned and rolled my eyes.

In fact, he hardly prepared for a class. Not like me. I’d draft out my lecture, practically word for word. I thumbed through my old class notes from graduate school. I pulled books down from my bookshelf and checked for dates or salient quotations.

Now, when did that author die?

How did that literary movement start?

What’s the setting of this story and when did the author write it? What school was he in?

There were so many facts I needed to impart, just as they had been imparted to me.

When I paged through my notebooks from graduate school, I’d see I had written down my sensei’s lectures almost word for word. I remember how the soft pad of my middle finger throbbed after a lecture, tender from where the pen had pressed against it as I madly transcribed the lectures. I barely raised my head.

Not my students.

They sat at their desks twirling their pens through their fingers in acrobatic maneuvers so intricate, I nearly lost my place as I strained to follow the mesmerizing motions.

Occasionally a student would miss a loop and the pen would clatter to the classroom floor. All eyes would shift to the distraction. Mine, too, as I paused to catch my breath.

“I guess we can skip this section,” I’d tell myself, realizing we were short on time.

“Okay, let’s turn to the story. What do you make of the setting?”

Silence.

“Do you think the setting influences the way the story is told?”

Students shifted uncomfortably in their desks, eyes downcast, hoping I would not call on them.

And so it went.

Most of my students were politely bored. But occasionally there was one or two who would sigh audibly.

Or, challenge me.

I hadn’t expected that. I would never have even dreamed of questioning any of my professors. They were like gods to me, and the words flowing from their mouths were the manna from heaven that I dutifully collected in my notebooks.

“What did you just say?” I remember one student asking—a young man with uncombed hair and poor posture who nevertheless exuded maximum confidence.

“Hirsute,” I repeated, surprised at the interruption. It wasn’t yet time for discussion.

I had been talking about the Ainu people, who were racially distinct from the majority Japanese and had more facial and body hair.

Only I didn’t pronounce the word correctly. In fact, I had never heard the word pronounced. I had only read it. When I was preparing for my lecture, I had never even thought to practice the pronunciation. I practiced other words out loud before class—mostly Japanese—but occasionally words like Nihilism.

Was it Nigh-a-lism? Or Knee-a-lism? I could never remember.

But hirsute was a word I only said to myself, and I always said it in my head this way: “Her-u-sute.” And so that’s what I said.

And then Mr. Arrogance called me out, insisting that I say the word again and then again, in my incorrect pronunciation before providing me—haughtily—with the correct pronunciation.

I could feel my face flush.

I didn’t really know what to say in response.

I imagine I stammered out some kind of halfhearted word of thanks, giggled at my own incompetence, and then resumed my lecture.

Another time a student grew visibly angry when I reminded them of the final exam.

“Why do we have an exam? Isn’t this a literature class? No other literature class here gives final exams.”

I had never thought of that. My literature professors had always given exams. There were so many facts to master, after all. Dates, terms, historical schools.

“What is Naturalism (shizenshugi)?’

“Who was Shiga Naoya and what important works did he write?”

And so on.

I knew my Japanese literary history backward and forward.

But…and this was a real moment of enlightenment for me…maybe my students didn’t need that kind of knowledge. In the end, what good did it do them?

What was I teaching them, after all?

Maybe I didn’t need all those notes. Maybe we should just talk.

It wasn’t easy at first.

Walking into a classroom without my entire lecture printed out was terrifying. I felt vulnerable, unprotected. What if I made a mistake?

I started reading passages with my students.

“Kimberly, read the first paragraph of the story.”

“How does this paragraph introduce the major themes in the story, or does it?

“How does it establish the setting for the story?”

“What surprised you?”

And so on.

Starting this way meant that I had less control over the direction the class would take. Students can say some pretty unexpected things about their readings.

And, sometimes I didn’t get to introduce all the “facts” that I thought were important. But it didn’t matter.

Class discussion proceeded organically. Each class differently. Some more successful than others.

I like the randomness now, never knowing exactly what I’ll find. It is no longer terrifying.

And most importantly, though I don’t have Dennis’s exquisite confidence, I no longer mind if I make mistakes.

I’ve learned to say: “I don’t know.”

Or, “let me check, I’ll get back to you,” when a student asks a question that I hadn’t anticipated.

I’ll never be a professor like the professors I had in graduate school. They were gods.

Rather than a god, I am a guide.

I prefer to take my students on an adventure in the texts we read. I’m not always sure where the adventure will take us, but I’m pretty sure I’ll be able to get them through the class and with a better understanding than when we began.

And, though I am the guide, I find that my students show me paths and directions I hadn’t considered earlier.

I’m still not able to walk into a classroom with only the three steps to the podium as preparation—as Dennis claimed to do—but I am able to leave my notes back in my office.

The post Teaching Tips: The Three Most Important Steps to Take Before Class appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 15, 2025

Raney-Day Woman: Finding a Home in Southern Fiction

This journey began years ago when I went on a Southern literature kick. All I ever wanted to read was novels about the South by writers from the South. I consumed the works of Eudora Welty and Flannery O’Connor, then went onto Robert Penn Warren, and Dorothy Allison. Later I refined my parameters to novels written by North Carolinians: Maya Angelou, Thomas Wolfe, Kaye Gibbons, and Doris Betts. I also made room for writers who had spent time in North Carolina, like Lee Smith and Anne Tyler. Something about Southern writing appealed to my taste and affirmed my own experiences. It also offered a pushback against the silencing of Southern attitudes and accents I had encountered so often in mainstream media and higher education.

Southern writers served up stories steeped in the deep-fried flavors I was used to. They excelled at dialogue with sassy backtalk and themes of twisted family relations and the dark wounds everyone saw but refused to speak.

I love any well-written novel, of course, but Southern fiction speaks to me.

It was during this reading jag that I encountered Clyde Edgerton and began devouring his novels one right after the other.

Edgerton grew up in a small town outside of Durham, North Carolina. The little town, Bethesda, is now mostly part of Durham, but during Edgerton’s childhood it consisted of a single flashing traffic light, a Southern Baptist church, and a wreath of woods all the way around it. The town was very similar to Wake Forest, where I grew up.

And like Wake Forest, Bethesda shared in the same clutch of rules, nosey prohibitions, and gossip whispered in church pews and over sweet iced tea.

I felt an uncanny affinity for Edgerton. He understood the double draws of race and religion on those of us who grew up in the South. He was able to poke fun at small-town Southern morality without denying his love of Southern eccentricity. In one of his novels, he even describes six generations of a family named Copeland.

It was Edgerton’s novel Raney (1985), though, that drew me in. I had the strange sense of seeing my own life reflected there.

It was Edgerton’s novel Raney (1985), though, that drew me in. I had the strange sense of seeing my own life reflected there.

Raney describes the “first two years, two months, and two days” in a marriage between small-town Raney and her more worldly husband, Charles. Raney, nurtured in a close-knit family, is fiercely loyal to her Freewill Baptist church in (fictional) Liston, North Carolina. Charles hails from the big sin-filled city of Atlanta and follows (when it suits him) the teachings of the Episcopal church. The drama in the novel—told via stinging satire—unfolds in the “culture clash” between Raney’s fundamentalist grounding in Christianity and all of its puritanical teachings and Charles’ more liberal, self-focused approach to life and its enjoyment.

I read Raney one winter when I was home in Raleigh, visiting with my parents. My husband Dennis and I were then living in Japan where he had a professorship with International Christian University.

In many ways, we resembled Raney and Charles. My family was Southern Baptist; Dennis’s was Lutheran. My parents did not drink; his family enjoyed imbibing. My parents were frugal; his were more apt to spend money on entertainment. My parents grew up in rural areas with roots as deep as the first white settlers. His parents were from New York and had closer claims to Europe, particularly Scotland, but also Jamaica.

When Dennis and I got married, we held the reception at my parents’ house in Raleigh to keep costs down. (He and I certainly had no money!) Because a few of my parents’ religious relatives would be in attendance, we were not allowed to serve alcohol. This infuriated Dennis. His family had flown down from the Northeast—the least we could do was give them a drink!

Dennis used salty language. I hadn’t yet acquired such a colorful vocabulary.

While we were in Tokyo, we took advantage of our winter breaks to travel, venturing to Burma (now Myanmar), Thailand, and China. For me, though, Christmas was a time to spend with family, and, yes, go to church. I enjoyed adventuring with Dennis, but I wanted to be in North Carolina for the holidays.

He agreed to a hometown visit on one of our returns from an adventurous European trip.

In 1989 we flew to Europe as soon as the autumn term ended. We had a rail pass and traveled from Amsterdam to Germany (where we spent Christmas in a hotel) to Switzerland to France and finally to England, where we celebrated the New Year.

Author in Paris, winter 1989