Rebecca Copeland's Blog, page 5

April 10, 2024

Celebrating a Century Home

Dreams come in all varieties. Some bring us comfort; others terrify us. Many slip away the minute we awaken and leave no trace. Occasionally, we have the same dream again and again.

My friend, Nancy, has very vivid dreams. She recounts them to me when we run together in the morning. Sometimes I can’t tell if she’s telling me a dream or if her waking world is just really wacky. Her dreams are often funny, rarely frightening, frequently embarrassing.

When I have strange dreams, I sometimes bring them to Nancy. She’s good at telling me what they mean. Or at least, she tells me what she thinks they are supposed to mean.

When you dream about a house, she says, it often symbolizes the condition of your life at the moment. A well-ordered house suggests stability; a run-down one reflects turmoil and anxiety.

Once I dreamed about finding a room in my house that I didn’t know I had.

“Oh, that’s a good dream!” Nancy announced. “It means you have untapped potential!”

Before I bought my house, I used to dream of the kind of house I wanted. Each year the house in my dreams changed, in accordance with my tastes. When I finally managed to buy a house, it looked nothing like my dreams.

I still dream of houses, though.

Earlier, I dreamed of giving my house a birthday party when it turned 100 years.

Built in 1923, I requested a plaque from the Historical Society of University City when 2023 rolled around. Once the plaque arrived, and was proudly mounted on the porch facing the street, I decided to throw my house a party.

The party was particularly poignant to me, considering I almost lost my house in the flood of 2022!

Century Home Plaque

I collected my friends together and even hired a band.

People began to arrive for the festivities, bringing bottles of wine and things to eat. I was enjoying talking to everyone—you know, a party with friends—when I began to notice that the place was getting crowded.

Where did all these people come from?

At some point, one of my friends brushed past me on her way to the kitchen and said with a knowing look, “I hate to see your credit card bill next month.”

That’s when I remembered I had given my debit card to another friend to run out and buy more wine—given how crowded the party had become.

The more crowded my old house became, the stranger the party turned. I saw two men I didn’t know walk into the kitchen, each carrying a case of bottles.

I went to search for the friend with my card.

“She gave the card to Darcy,” someone told me.

Who’s Darcy? I wondered.

That’s when I realized that I didn’t even know most of the people around me.

And then things really got weird.

We were no longer at my house. We were in a large building, the kind used for big events.

Eventually, a woman walked up to me. It was Darcy.

She was accompanied by a short, round, sweaty man with strawberry blond hair who was acting like an agent or a producer or someone official. That’s probably why he was very officious.

Someone cautioned me to be polite. “He may not look like much, but you don’t want to take the wrong step with him.”

Smiling at the Mr. Officious as politely as possible, I turned to Darcy and tried to act casual.

Can I have my card back?”Darcy just looked at me and stepped away, leaving me with the man who seemed to be sweating even more profusely than before.

“You’ll probably need to pay a fee,” he told me as he handed the card to me. It glistened slightly.

“I had to change your pin.”

“You changed my pin?”

“You know, the pins on both your cards are very similar. I couldn’t get the last two digits on the credit card. But I changed the one on the debit. You really shouldn’t have such similar pins.”

“Wait, my bank will charge me for changing the pin?”

“Just talk to your bank.”

Before I could collect myself enough to challenge him, he changed tracks.

“I mean, not to offend you or anything, but the band you hired is too small town. We’ve got guests here who have flown in from Hollywood for this event. They really expect more. I’ve already had one guest complain. He just left.”

I didn’t know who the unhappy person was but all I could think was “good riddance.”

I didn’t know any of the people standing around Mr. Officious, whose name I now knew was Philip something. I saw someone holding an invitation to my party but the invitation described it as some kind of “happening” produced by “the Darcy and Philip team.”

Philip started telling me the names of all the important people who had come to the party.

He was standing too far away from me to easily make out what he was saying. I kept repeating to him what I thought he was saying.

“Sailboat?”

“No! Sal B. Hoat.”

We went through a number of names like that. Philip mumbling something, me shouting what I thought he said, he correcting me. Like a warped game of telephone.

Finally, Philip grew frustrated repeating everything and came close enough for a conversation. He showed me the guest list, pointing out the important people.

Why were they at my party? Why was I paying for them?

I woke up before I got any of the answers.

And I woke up before my dream self had time to panic over the likelihood that my bank account had been ransacked.

I was in Tokyo when I awoke, at an airbnb. It was June 3, 2023, and I was still struggling with jetlag.

I had bought a bottle of wine the day before at a nice wine shop in Kichijōji.

But it certainly wasn’t enough to bankrupt me.

The post Celebrating a Century Home appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

March 27, 2024

A City that Starts With C.

Is there a city in New York State that starts with “C”?

Not a small place like Carlton or Clyde, but a bit city, a city the size of Buffalo or Albany?

The other night, I was on my way there.

Only, for the life of me, I could not remember what the name of the city was.

Even so, I was headed to the city that starts with “C.” All was going smoothly until I made a mistake.

I missed my stop. When I tried to recover my steps, I couldn’t because I couldn’t remember where I was going. It’s hard to get there, when you don’t know where there is.

I was traveling with an acquaintance. Her name doesn’t matter because I don’t think I even knew her name. But, I knew her.

We had just left a Japanese Studies conference and were on a train, somewhere in the Northeast—that faraway land we call “back east.” It was unfamiliar territory to me.

She was heading home. I was going to another professional event of some kind, a lecture or a symposium.

We came to a stop called “Bus Stop.”

That sounded odd to me. I sat alongside my acquaintance and watched the sign for “Bus Stop” fade as the train pulled away from the station.

We neared her stop and she began to collect her belongings.

“I wonder when mine is coming up,” I asked, mostly to myself.

She heard me and said, “Oh you should have gotten out at ‘Bus Stop’. I’m sorry I didn’t tell you.”

Now it was too late.

She got out, as I went to speak to the driver.

Apparently, the conveyance was not a train but a bus.

“No,” he said, you can’t just stay on the bus and circle back to Bus Stop. No, there is no return bus to Bus Stop now.”

There I was, in the middle of somewhere with no way back to wherever I was going.

I can’t remember if I got out of the bus or if it just morphed into an abandoned shopping mall.

The mall was a maze of corridors and hallways.

I wanted to ask the next person I saw for directions, but to where?

Realizing it was time to do so, I stepped into a restroom. It was spacious, with lots of stalls.

Seated on the toilet, I looked down and saw that my purse, which was now in a brown plastic Schnuck’s grocery store bag, was on the floor.

“That’s not wise,” I thought to myself, and just as I started to retrieve it, a hand reached under the stall and stanched it away.

“I’ll catch that thief!” I told myself. “I’m a pretty fast runner.”

When I stood to rise, I felt pressure on my shoulder, preventing me from standing up.

I tried again. Same story.

I was stuck.

I looked over my shoulder and realized the sleeve of my shirt was caught on a hook. (The hook where I should have hung my purse.)

I released myself, and left the stall.

By now, the thief was long gone. And so was my wallet, my identification, and my cell phone. I had nothing.

And, I didn’t know where I was going.

Some place that starts with C.

At what point reading the above did you realize I was recounting a dream?

So many dreams are like that, aren’t they?

At least mine are.

They start out very real and then at some point along the way, they morph into ridiculous scenarios. Eventually, as I am drifting along, I realize I’m in a dream. Sometimes, if I’m enjoying myself, I just let go and savor floating through surreal landscapes. I’ll even egg myself on, suggesting more and more bizarre twists and turns until even my dreaming mind can’t take any more and I’ll awaken.

When that happens I’ll keep my eyes pressed closed and try to dip back into the river of dreams, but I never can. Not really. I’ll know I’m the one in charge, so it’s no longer fun.

I remember the above dream because I wrote it down after I woke up on October 8, 2023.

I picked up the foster dog Kolby on October 7, 2023. Could he have been the destination that starts with “C”?

The post A City that Starts With C. appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

March 13, 2024

Having Fun with Fear and Folklore: A Webinar on Japanese Yōkai

If you like creepy, spooky things—ghosts, goblins, and shapeshifters—Japan is the place to be! For centuries the Japanese have enjoyed tales of mysterious happenings: umbrellas and tea pots with a will of their own; foxes that transform into alluring women and spiders that do, too; water imps that terrorize; and vengeful ghosts that never leave. All of these fall under the category of “yōkai,” a general term for the strange and inexplicable. All cultures have their own set of monsters and mysteries. One fun feature in Japan is the fact that the denizens of the yōkai world continue to grow. New yōkai are added, and old ones adapt to new environments.

A few years ago, Linda Ehrlich and I co-edited a book on one such yōkai, the yamamba or mountain witch. We collected original works inspired by the yamamba. In Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch, we found the venerable yōkai appearing in the Blue Ridge mountains, on the modern dance stage, and conversing with Mexican traditions.

Last week I had the pleasure of participating in the webinar “Fear and Folklore” organized and convened by Alex Rogals of Hunter College. Alex is a scholar of Japanese theater with specialty in Kyōgen, often described as a comedic mode. He is himself a playwright and actor. At Hunter College he teaches classes on Japanese myth and folklore, horror, and mystery. He created the webinar to engender a discussion on the different aspects of yōkai and the way it has become a worldwide phenomenon.

Michael Dylan Foster was another member of the webinar panel, and Alex could not have chosen a more renowned expert. Michael wrote his dissertation on modern Japanese novelist, Dazai Osamu, but in the course of conducting his research, found his interests shifting to the rich field of Japanese folklore. He has subsequently written a number of award-winning books and a multitude of articles on this fascinating topic. See for example, his 2015 volume The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore.

In addition to Michael and Alex, the panel also featured Zack Davisson, a veritable encyclopedia of all things yōkai. If “yōkai” finds its way into the English lexicon—represented by placement in Webster’s Dictionary—it’ll be thanks to Zack’s hard work. Zack has published widely on the topic. He has translated as well and has traveled the world lecturing on his favorite yokai.

Spending the evening talking to Michael, Zack, and Alex was a delight. I stared out madly scribbling notes after each panelist spoke, until I remembered that Alex was recording the event. So, don’t take my word for it. If you have the time, enjoy the webinar for yourself!

The post Having Fun with Fear and Folklore: A Webinar on Japanese Yōkai appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

February 28, 2024

Book Talk: Still Celebrating The Kimono Tattoo

My debut novel, The Kimono Tattoo, entered the market in June 2021. At the time, most book stores in St. Louis were still observing Covid-related protocols and refrained from in-person events. I didn’t have enough clout (or marketing skills, frankly) to create an online book launch at a book store.

Generous friends, however, put together a small launch, at Iva Youkilis’ house. Students came, colleagues, and neighbors. It was loads of fun and I was feted like some kind of celebrity!

Book Launch, Clayton, MO, June 11, 2021

My publisher arranged a number of online events for me, and I was fortunate to be asked to participate in the Pulpwood Queens annual conference, which was held online for the first time in 2022.

Book clubs have scheduled meetings with me—in person, on zoom, and even on the telephone.

So, I have had numerous opportunities to feel like a “celebrated author.”

Even now, three years after the release of The Kimono Tattoo, I still feel exhilarated when I’m asked to talk to people about it.

Last week was no exception!

I was invited to speak at the University City Public Library.

Well, “invited” may not be the right word.

I contacted the Head of Adult Services, Kara Krekeler, and offered to give a talk. She kindly worked me into the schedule.

The University City Library is only a few blocks from my house. I used to stop in regularly to register for the annual University City Memorial Day 10K, to vote in municipal and national elections, and to meet friends. The library moved temporarily to another location last year while the old building underwent reconstruction.

It was fun to return to the familiar meeting hall—books in hand—to speak with friends and neighbors about The Kimono Tattoo! It felt a little like a homecoming.

Kara kindly taped the entire event. If you are so inclined, you can watch the presentation on YouTube.

There’s a separate link to the Q&A. I always enjoy the back-and-forth of this aspect of a talk. Here we put the script aside and just talk.

The post Book Talk: Still Celebrating The Kimono Tattoo appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

February 14, 2024

On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 7

I remember being almost giddy when someone first gave me a handkerchief with Uno Chiyo’s signature motif. It was pale pink with small white dots, not quite cherry blossoms. But the sheerness of the fabric hinted at the delicateness of the petals.

Whenever I met with Uno Sensei in the 1980s and early 1990s, I always came away with new cherry-petal-patterned gifts: handkerchiefs, towels, and sensei’s latest books resplendently bound in cherry-petal patterns.

Once while shopping in Tokyo, I came across a bolt of dark indigo-blue cotton yukata fabric, sprinkled with white cherry petals. It was a little bit more than what I wanted to spend, but I had to have it.

I planned to cut it into curtains, but could never bring myself to put scissors to the fabric. It remains, to this day, rolled up and stored away, alongside my Uno Chiyo handkerchiefs, towels, teacups, and other items.

After Uno Chiyo died in 1998, I found that our bond only deepened.

When I taught about her in class, she returned to me.

I’d bring her fabrics and photographs to show my students. I’d tell them about meeting her.

And there she was, smiling at me, her eyes twinkling behind her thick-lensed eyeglasses.

In 2004 I had the opportunity to teach at the Kyoto Center for Japanese Studies. During my stay in Kyoto, I joined a group of American college students who were studying Japanese dance, Nihon buyō.

It had been years since I’d practiced dance and I admit I was much slower to learn than the younger students! Nishikawa Sensei, the teacher, was very patient with me. In fact, she would sometimes allow me to stay behind after class to talk.

We talked about kimonos, theater, and literature.

At some point, we discovered that we were both great fans of Uno Chiyo.

Not just fans. Nishikawa Sensei had been Uno’s friend.

And, she was still in touch with Uno’s secretary and surrogate daughter, Fujie Atsuko-san.

“Atchan has been depressed lately,” she told me one day after class, using the familiar name for Fujie-san. It’s the name Uno Chiyo had used. Hearing Nishikawa Sensei refer to Fujie-san that way reminded me of how fond she had been of Uno.

When I inquired further, I learned that Fujie-san often felt lonely now that Uno Chiyo had died.

That surprised me.

She always struck me as rather formidable! The perfect gatekeeper.

But then I remembered the way she always sat next to Uno Chiyo whenever I visited and fussed over her, straightening the collar of her kimono, pouring her tea, often finishing her sentences.

At some point, I struck upon an idea.

I’ll travel to Tokyo and pay Fujie-san a visit. I wanted to light incense for Uno Sensei. And, I wanted to perform the dance “Sakura” (Cherry Blossom) for her.

By now I had practiced three dances with Nishikawa Sensei: Sakura (Cherry Blossom—the first dance in almost any repertoire), Takasago (a dance derived from the Noh stage and very stately), and I was still learning Oborozuki (Hazy Moon, a beautifully melancholy dance miming lost love).

I had also practiced wearing kimono.

It had become my habit to dress in kimono at home and then commute to Nishikawa Sensei’s dance studio. The commute included a bus ride and then a walk of four-five blocks. At first I had been self-conscious, worried that people (whoever that means) would think I was impetuous or inappropriate or vain.

In fact, hardly anyone noticed me. The people who did, usually women my age or older, treated me kindly—either remarking on how nice I looked or just smiling warmly.

I began to look forward to my kimono commutes.

It was settled.

I called Fujie-san to let her know of my interest in visiting Tokyo to offer incense at Uno Chiyo’s Buddhist altar—housed in her Minami-Aoyama apartment. I didn’t tell her about my wish to dance, though.

Dressed in lavender hitoe. Kyoto, Japan. Author’s photograph.

On the appointed day, I carefully laid out the kimono I would wear, a light lavender hitoe (unlined kimono) appropriate for the warm July weather and a white ro silk fukuro obi.

I had purchased the hitoe kimono at a second-hand shop that I frequented on my way to and from my dance lessons. The obi I had found at the monthly Kitano Tenjin market.

Seeking out kimonos had become a hobby of mine. Finding occasions to wear them was a treat.

Properly dressed, I took the bus to Kyoto Station and from there caught the Shinkansen to Tokyo.

I don’t remember much about the commute from Tokyo to Minami Aoyama. At some point, I took a taxi. I was nervous about sitting so long and allowing my kimono to wrinkle.

I also noticed that people in Tokyo greeted me and my attire with greater curiosity than did those in Kyoto.

Fujie-san was delighted when she saw me. She had never seen me in kimono.

She had me spin and turn. She tugged a bit at my collar. (Admittedly, it is the feature of the kimono that I can never quite get right. It’s such an important feature, too.)

She invited me into the familiar sitting room. The low wooden table was still there along with the Oyumi puppet in the glass case. In fact, everything was the same as it had always been.

Meeting Fujie Atsuko-san at Minami Aoyama, Tokyo. Author’s photograph

Only, Uno Chiyo was missing.

I could understand Fujie’s loneliness. Uno Sensei’s absence was palpable.

“May I burn incense for Sensei?” I asked.

I had received careful instructions on the proper incense to buy, the way to light the stick (never blow the flame, only fan it out), and how to pray.

Fujie-san watched as I sat before the altar and offered my prayers.

When I was done, I told her I wanted to perform a dance for Uno Sensei and would she mind?

Fujie-san smiled brightly. She had not expected me to appear in kimono. And she certainly had not expected me to dance. But she was pleased to acquiesce.

I pulled the cassette tape recorder out of my bag, set it on the low wooden table, opened my pink fan—the one Nishikawa Sensei had given the students practicing Sakura with her—and nodded to Fujie-san to push the button on the recorder. When the strings of the koto sounded, I began.

I danced the best Sakura I had ever danced.

I could feel Uno Chiyo smiling down on me.

I could see her acting out the way she scattered magic ashes over the dormant cherry blossom tree—the Hanasaku Obaasan (“The Old Woman Who Made the Dead Trees Blossom”)—whoosh, whoosh.

My heart burst with scattered petals.

When the dance was done, I knelt on the tatami before the butsudan, folded my fan, brought the tips of my fingers together on the floor and bowed.

When I looked up, Fujie-san had tears in her eyes.

My eyes, too, misted over.

She offered me tea.

Suddenly, she instructed her assistants to bring out bolts of fabric.

Bolts unfurled, silk swished, colors flashed. One by one she wrapped them around my shoulders.

I was to have an original Uno Chiyo kimono!

The blue was beautiful but too bright. The pink was surprisingly drab. We decided on a dark grey fabric with multicolored petals, a few flecked with gold.

Fujie-san had the kimono sewn and a month later shipped to Nishikawa Sensei’s studio.

Nishikawa Sensei selected an obi from her collection and gave it to me to wear with the kimono, a subtle gold satin with an overlay design of opalescent mother-of-pearl.

An obi that complements but does not compete, the perfect choice for my Uno Chiyo kimono.

Wearing my Uno Chiyo kimono and Nishikawa Senrei obi. Raleigh, NC. Author’s photograph.

As I have grown older, the color of the kimono suits me more and more. And each time I wear it (admittedly not as often as before), I feel Uno Chiyo once more come to life—whoosh, whoosh—with cherry petals brightly scattering.

The post On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 7 appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 31, 2024

On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 6

Could the Old Woman who Scattered Cherry Blossoms revive a tree? The irrepressible author, kimono devotee, and designer saw no reason not to try. Reflecting on Uno Chiyo’s legacy and her take-charge approach to life, we see how she brought vitality to everything she did.

When Uno Chiyo died on June 10, 1996—at the age of 98—she left behind a legacy of feistiness, fun, and art. Her rich collection of literary works spanned three imperial reign years and featured a variety of genres from fiction, memoir, and essay. She published her last fictional work, “Ippen harukaze ga fuitekita” (Suddenly a Spring Wind), in 1987 when she was ninety.

In addition to literary works, she left behind a treasure trove of kimonos.

Uno founded the fashion magazine Style during the interwar years, which initially promoted the enjoyment of western wear. As the war wore on, the militaristic government instituted sumptuary laws and frowned on the consumption of Western clothing. Uno shifted her interests to the kimono. She began working with fabric, designing kimono patterns, many of which she used as bindings for her books.

Once the war ended and the dust settled, Uno used Style to showcase her kimono. Her designs at the time were often boldly abstract and asymmetrical, like a Paul Klee painting. While women rushed to embrace the Western fashions that had been forbidden earlier, Uno committed herself to the kimono, working with designers and manufacturers on new fabrics. She wore kimonos every day of the week.

As her brand grew in popularity, her style solidified. Her abstract patterns morphed into a delicate sprinkling of cherry blossom petals.

Gradually her business branched out into other products, such as handkerchiefs and scarves, and then into ceramics and other items that bore her signature cherry blossom petal motif. Today, long after Uno Chiyo’s death, her brand lives on.

Check online and you can find teacups, umbrellas and pajamas bearing her prized cherry blossom pattern, even incense (not that cherry blossoms actually have much scent.)

Uno Chiyo once explained her fascination with scattering cherry petals.

She always enjoyed the folktale Hanasaka Jiisan or “The Old Man Who Made the Dead Trees Blossom.” The story is a bit complex. It deals with an old man who is pure in heart vs another who is greedy. To the pure fall gifts, to the greedy only grief. In one scene, the pure-hearted old man is instructed to scatter ashes over cherry trees. When he does so, the trees burst into bloom, just as the local daimyo is passing by. Delighted by the display, he bestows lots of gifts on the old man.

She always enjoyed the folktale Hanasaka Jiisan or “The Old Man Who Made the Dead Trees Blossom.” The story is a bit complex. It deals with an old man who is pure in heart vs another who is greedy. To the pure fall gifts, to the greedy only grief. In one scene, the pure-hearted old man is instructed to scatter ashes over cherry trees. When he does so, the trees burst into bloom, just as the local daimyo is passing by. Delighted by the display, he bestows lots of gifts on the old man.

Uno Chiyo was fond of the image of flowerless trees bursting into bloom.

When she re-told the story, her face brightened with joy, as she held up her right arm and mimicked scattering ashes by the handful here and there. Whoosh, whoosh the trees burst into bloom.

In some ways, she saw herself in the old man’s role but called herself the “Old Woman Who Made the Dead Trees Blossom.”

Like the old man, she brought a dead tree back to life.

Literally.

In the early 1970s, Uno’s friend, the literary critic, Kobayashi Hideo, told her about a cherry tree in Gifu Prefecture that was planted in the sixth century by Emperor Keitai, making it over 1500 years old.

Uno rushed off to see the tree for herself.

She was dismayed to find the tree on the verge of death.

Immediately, Uno launched a campaign to save the tree, raising funds and soliciting the support of the prefectural government.

Whereas she did not sprinkle magic ashes over the branches to coerce new life from the tree, she did see that grafts were made.

Photo of the tree from April 1, 2020.

Not only was the tree saved, the attention brought new tourist revenue to the area. Uno Chiyo was dubbed the patron saint of the tree and the town.

The experience led Uno to write the hauntingly beautiful novel Usuzumi no sakura (The Ink-Grey Cherry Tree) in 1974. It also inspired her scattering-cherry-blossom-petal motif.

Perhaps Uno Chiyo’s love of cherry blossoms also inspired me.

Her art and mine have overlapped in a number of ways—one of which I will share in my next post. Stay tuned!

The post On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 6 appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 17, 2024

On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 5

I successfully defended my dissertation, Uno Chiyo: The Woman and the Writer, in December 1985. A few months later, I was on my way back to Tokyo, where I would spend the next five years at International Christian University. On a whim, I had two copies of my dissertation printed and bound at a copier shop in Mitaka, Tokyo. One, I decorated with pretty strips of origami paper. I wanted to present the finished product to Uno Chiyo. By now, following our initial meeting on June 21, 1985, we were in regular contact.

I enjoyed following Uno Chiyo’s career and would frequently spend time at the Kinokuniya bookstore in Shinjuku, thumbing through journals for her latest essay. She was nearly 90 and still very active as a writer. Twice monthly she serialized a “mini memoir” in the popular women’s magazine Croissant.

Croissant featured tasteful photographic essays on interior design, kitchen adventures, and beauty regimens, geared toward the single 30-something woman. Uno’s essays covering moments from her many romances, her later encounters with old lovers, and her favorite kimonos, offered a welcomed flash of sass.

Croissant featured tasteful photographic essays on interior design, kitchen adventures, and beauty regimens, geared toward the single 30-something woman. Uno’s essays covering moments from her many romances, her later encounters with old lovers, and her favorite kimonos, offered a welcomed flash of sass.

Uno playfully titled her mini-memoir the “Cherry-Blossom Furisode Kimono Series.” The title referred to her love of cherry blossoms (her signature kimono-design motif) and her sometimes “inappropriate” sartorial choices.

A furisode is a kimono with long-fluttering sleeves typically worn by young, unmarried women. For her 88th birthday celebration (known as Beijū in Japanese) Uno made a big splash by wearing a number of furisode kimonos (of her own design) at a star-studded party in the Tokyo Imperial Hotel.

I loved heading to the Kinokuniya whenever I could to catch the next issue of Croissant. No telling what kind of secrets Uno would spill!

I was both delighted and surprised when Uno’s secretary, Fujie Atsuko-san, called me shortly after I sent her the bound copy of my dissertation. The editors of Croissant, Fujie-san explained, thought it would be fun to capture me interviewing Uno Sensei for one of her “mini memoir” installments.

“After you give her your dissertation [again], you can ask her questions about her stories and talk about the novella you are translating.”

“After you give her your dissertation [again], you can ask her questions about her stories and talk about the novella you are translating.”

Fujie-san referred to the fact that I had just begun translating Uno Chiyo’s novella Kaze no oto (The Sound of the Wind), a fictionalized account of a ne’er do well playboy based loosely on Uno’s own father. The work was richly laced with Iwakuni dialect.

Not really certain what to expect, I returned to Uno Chiyo’s elegant apartment in Minama Aoyama. We spent a little over an hour huddled around her heated kotatsu table, conversing about this and that.

There is a photograph of us in the magazine, looking as if we are conversing by lamplight in the waning hours of a winter afternoon.

In reality, her spacious upstairs room was lit up like an operating room with portable can lights on tripods as photographers darted here and there with their cameras.

Our “intimate” conversation was punctuated by the snap, snap, snapping of camera shutters and the occasional sharp hum of the flash.

I could hardly concentrate on what Sensei was saying.

When the session was over, my back ached from sitting so rigidly at the table, constantly aware of being scrutinized. So much for my celebrity career!

I couldn’t imagine how the “conversation” would yield a suitable article.

And then, two months later, the editors of Croissant sent me two copies of the February 10th issue with my “interview.”

My translation follows:

CROISSANT クロワッサン 2.10.1987UNO CHIYO

A Mini Memoir

#42 in the Cherry-Blossom Furisode Kimono Series

Here Uno-san is enjoying her visit with Rebecca-san. She does seem a bit more serious than usual, doesn’t she? Surely her earnestness is a reflection of her character. Or does she find it amusing to be put in the position of a “representative of Japan”?

“Rebecca-san is a scholar. Her questions are really tough!”You see, Rebecca-san is a scholar of Japanese literature at Columbia University. She decided to work on “Uno Chiyo” for her doctoral dissertation. Now she is translating my novella Kaze no oto (The Sound of the Wind) into the English language.

I’m just delighted. This means people in America and England will be able to read my works in English.

Earlier, Donald Keene-san published an English translation of my novel Ohan. Following that someone translated a section of my story Sasu (To Sting) and my story “Kōfuku” (Happiness). It was after reading those translations, I suppose, that Rebecca-san developed a fascination with “Uno Chiyo.”

I think that in “Sasu” my ideas are not unlike what you’d find in an English novel. But there are aspects of Ohan and Kaze no oto that are almost too Japanese for even Japanese people to appreciate fully. I think they must be very difficult to translate.

Rebecca-san came to ask me about some of the words in the novel she didn’t understand. She said terms like “agarigamachi” [entryway step] and “seto no ma” [back room] were difficult. Even most Japanese people these days don’t know what these are!

Then Rebecca-san asked about the hairstyle “shinchō” or “new butterfly.” Back in the old days, this was a very chic Japanese-style coiffure. Mostly geisha and courtesans wore their hair this way. Young girls wore a momoware [peach-cleft style]. Proper matrons wore a marumage [round upswept style] or shimada [high upswept style. I wonder if there isn’t a picture of me with my hair in a shinchō.

When I lived with Ozaki Shirō, before I bobbed my hair, I used to wear it that way. I did it for him. Ozaki loved to see me in a shinchō. As a young woman, I led something of a scandalous life, you know, and arranging my hair like a geisha or courtesan was well in keeping with that!

Can an American truly understand something like this, though, something so subtle? And even then, can she translate it?

Rebecca-san said that the style of Kaze no oto is superb. She said, “the colors in the sentences are particularly beautiful.”

“The red hem of the under kimono, the blue scarf, the white blossom….”

Even the names of the characters in the novel carry color, she said. The male protagonist Seikichi (Blue Fortune), O-yuki (Miss Snow), and the horse, too, Seiryū (Blue Willow). All of their names include color.

I never even thought about the names having colors! Maybe deep inside I was aware of the colors, but what I wrote just bubbled up from my senses. Rebecca-san read everything so carefully, far more closely than I.

I’m very lucky.

“A woman flung her pale blue shawl at the horse, jolting it so, he tore off in a panic.” [Uma ga, aoi katakake wo nagetsukerarete, tamagete monoguruoshiu kakedashimashita.]

Rebecca-san said that if she translated the word “tamageru” simply as “startled” (odoroku) she would miss the nuance of the kanji characters in the word (which literally mean to lose one’s spirit). In Iwakuni dialect, though, we use tamageru whenever we feel surprised. Now I can see how difficult translating really is.

I consider myself very lucky to have met Rebecca-san. For an artist to have her works read abroad is thrilling. I’ve read translations of Dostoevsky’s works, I’ve read Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and lots of other foreign works in translation.

This may be going too far but I wonder if there really are separate worlds when it comes to literature and art. This one is foreign; that one is Japanese. Don’t they all belong to the same world? The world of art? I believe they do.

Japanese people are attracted by sophisticated foreign cultures. Foreigners are drawn to Japanese culture. The feelings are the same for both, aren’t they? I think they are.

Rebecca-san said that to read Arishima Takeo and Natsume Sōseki and authors like that you really need to use your head. But not so for Uno Chiyo.

“Your style is gentle [yasashii].”

Having a “gentle style” is a source of pride for me.

A translation of Kaze no oto, Rebecca-san told me, will compare well with Enchi Fumiko’s Onnazaka (The Waiting Years), which is already translated. I know just what she means. Enchi-san writes of womanly matters with an intensity that is frightful. I can’t write of frightful things. My style is “gentle,” after all. Actually, I like to write of frightful things in a gentle way.

Rebecca-san also said she likes Irozange (Confessions of Love). It’s an interesting novel, but as I grow older I realize that it lacks any “moral” import. It’s still my best seller, but that doesn’t make it a good work. What I mean by “moral” is not what the protagonist does or doesn’t do but the moral feeling that courses throughout a book—in my books it comes from way I was living at the time. There is this kind of moral feeling in Ohan and in Kaze no oto.

Earlier I devoted myself to reading works by Alain [Émile-Auguste Chartier] and that’s when I became completely engrossed in thinking about what was moral. Before that, I’d never given so much as a single thought to any of it. Now I believe the morals we practice as we live out our lives and the morals in our literary works are completely the same.

As narrated to Miyake Kikuko.

Photograph by Shibata Hiroki

The post On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 5 appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 3, 2024

On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 4

Meeting celebrated author Uno Chiyo on June 21, 1984 (which incidentally or ironically was my fourth wedding anniversary) was a thrill.

The thrills didn’t stop with that meeting, though.

Four months later, I was in Shibuya standing in the Kinokuniya book store thumbing through the latest issues of literary journals. I always scanned the table of contents to see whether there was a new work by Uno Chiyo or a new critique about her. I checked Shinchō and then Bungei Shunjū. Nothing.

Next, I picked up Fujin kōron (Women’s Review). The journal was running a special issue featuring essays by or about the noted women writers of the time: Hiraiwa Yumie, Miyao Tomiko, Ōhara Tomie, Hagiwara Yōko, Setouchi Harumi, Enchi Fumiko, and Tsumura Setsuko.

BINGO!

I saw Uno Chiyo’s name.

Uno was represented by the essay “About my Novel Ohan” (Shōsetsu Ohan ni tsuite). It was only a few pages, so I turned to it and started reading.

Ohan is considered Uno’s masterpiece, an acclaim she willingly acknowledges. In her essay she described how she worked on the novel for nearly ten years, starting it when she was fifty and ending it just before turning sixty. Since it weighs in at barely 100 pages, she wonders why it took her so long to write and suggests it was a once-in-a-lifetime work.

I got to the end of the essay, flipped the page and noticed a new subtitle:

Rebekka-san no hakase ronbun (Rebecca’s Doctoral Dissertation).

WHAT?

A bolt of electricity zapped up my spine when I saw my name, and I must have shouted aloud because the person standing next to me, also reading journals, shot me a disapproving glance.

“Looook!” I wanted to squeal. “It’s about meeeeeee.”

Instead, I snapped the journal closed, picked up two more copies, and rushed to the cashier with my purchases.

I read the essay on the train and then again as soon as I got home.

Here is what Uno Chiyo wrote, referring to me in the passage below by my husband’s last name (which I then used):

Fujin Koron article. Author’s photograph

Rebecca’s Doctoral Dissertation (Rebekka-san no hakase ronbun)I can’t remember exactly when it was. Anyway, sometime ago I met Saeki Shōichi-san and he told me about a graduate student at Columbia University, a woman, who was doing research on me. She was in Japan now and had asked to meet me.

I immediately declined.

I told Saeki-san that I wanted to avoid a meeting like that at all costs. I mean, I can’t speak a word of English, so how on earth were we supposed to communicate? Besides, I found the idea of someone “doing research on me” disconcerting.

Not long after that, I received a letter from this woman student. Her name was Rebecca McCornac. The letter was thick, over ten pages. One surprise led to another. First, I was taken aback to find the name on the front of the envelope was written very neatly in highly legible characters. So was the address on the back of the envelope.

“Haikei”—the letter began with an extremely polite salutation.

Greetings and Salutations, Uno Sensei:

I trust that you are faring well as the days grow warmer. According to what you have written, Sensei, you do not use an air conditioner in the summer months, not even an electric fan. You must tolerate the heat quite well.

I was amazed by how well she knew me, and my amazement only increased as I continued reading.

Recently I traveled to Kyoto and Nara to see the sights. From there I took a train further south to Iwakuni. At the station, I hired a taxi. ‘Please take me to the writer Uno Chiyo’s house,’ I instructed the driver. He was young and friendly. We chatted along the way and he told me of an American serviceman stationed at the base there who had killed a Japanese bargirl. Sensei, the story he told reminded me of your novel Cheri ga shinda (Cheri is Dead).

Having read this far, I found myself encountering still more surprises, and I realized that the letter writer, this Rebecca McCornac, was no mere foreigner fond of literature.

Once she reached my Iwakuni house, she says, as her letter continued:

I wonder if your father’s ‘Clock Room’ is still intact. I wonder, too, if his beloved stable still exists.

That was it, I had to meet this woman. I know that just minutes ago I had been determined to avoid her. I have to admit even I was surprised by my own vanity!

Once I sent for her, Rebecca-san came to my apartment immediately. She had a childlike face and seemed very gentle, more East Asian than Western. Her manner of speaking Japanese was even more graceful than that of a Japanese woman. She had written down all the questions she wanted to ask me on a piece of paper, which she spread out on the table in front of her. When I saw this, I knew she must be very bright.

“Sensei, of all your works, which is your favorite?” she asked.

“Ohan,”I answered.

“Mine is Kaze no oto (The Sound of the Wind),” Rebecca countered. I wonder if Ohan is just too simple, too subtle for foreigners.

Two hours went by, and then Rebecca took her leave. I couldn’t believe the time had passed so quickly, being with her had been so pleasant.

Almost as soon as she had left, I received another letter from her.

Sensei, I admire you as a writer but more than that, I respect you deeply as a person. From here on out, I will work as hard as I can to produce a dissertation that does justice to your sparkling talents. Being able to meet you, Sensei, has made a profound impression on me.

I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Now I no longer think of this letter as being written by a woman student doing research on me. I just pray that Rebecca-san is successful in her dissertation.

Fujin Kōron (Autumn Special Edition, 1984): 22-23.

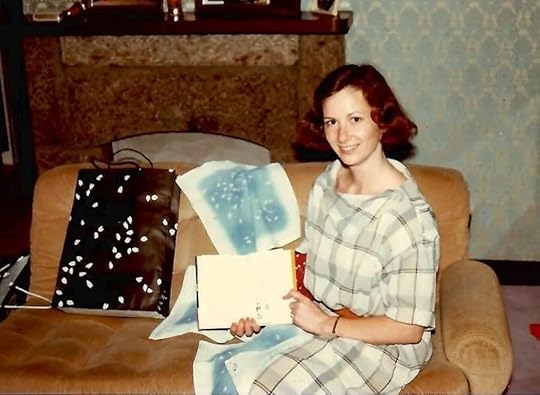

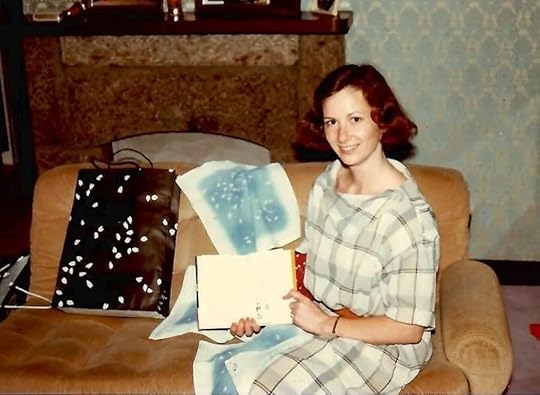

Rebecca with Uno’s Signed book

The post On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 4 appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

On Encountering Icon Uno Chiyo, Part 4

Meeting celebrated author Uno Chiyo on June 21, 1984 (which incidentally or ironically was my fourth wedding anniversary) was a thrill.

The thrills didn’t stop with that meeting, though.

Four months later, I was in Shibuya standing in the Kinokuniya book store thumbing through the latest issues of literary journals. I always scanned the table of contents to see whether there was a new work by Uno Chiyo or a new critique about her. I checked Shinchō and then Bungei Shunjū. Nothing.

Next, I picked up Fujin kōron (Women’s Review). The journal was running a special issue featuring essays by or about the noted women writers of the time: Hiraiwa Yumie, Miyao Tomiko, Ōhara Tomie, Hagiwara Yōko, Setouchi Harumi, Enchi Fumiko, and Tsumura Setsuko.

BINGO!

I saw Uno Chiyo’s name.

Uno was represented by the essay “About my Novel Ohan” (Shōsetsu Ohan ni tsuite). It was only a few pages, so I turned to it and started reading.

Ohan is considered Uno’s masterpiece, an acclaim she willingly acknowledges. In her essay she described how she worked on the novel for nearly ten years, starting it when she was fifty and ending it just before turning sixty. Since it weighs in at barely 100 pages, she wonders why it took her so long to write and suggests it was a once-in-a-lifetime work.

I got to the end of the essay, flipped the page and noticed a new subtitle:

Rebekka-san no hakase ronbun (Rebecca’s Doctoral Dissertation).

WHAT?

A bolt of electricity zapped up my spine when I saw my name, and I must have shouted aloud because the person standing next to me, also reading journals, shot me a disapproving glance.

“Looook!” I wanted to squeal. “It’s about meeeeeee.”

Instead, I snapped the journal closed, picked up two more copies, and rushed to the cashier with my purchases.

I read the essay on the train and then again as soon as I got home.

Here is what Uno Chiyo wrote, referring to me in the passage below by my husband’s last name (which I then used):

Fujin Koron article. Author’s photograph

Rebecca’s Doctoral Dissertation (Rebekka-san no hakase ronbun)I can’t remember exactly when it was. Anyway, sometime ago I met Saeki Shōichi-san and he told me about a graduate student at Columbia University, a woman, who was doing research on me. She was in Japan now and had asked to meet me.

I immediately declined.

I told Saeki-san that I wanted to avoid a meeting like that at all costs. I mean, I can’t speak a word of English, so how on earth were we supposed to communicate? Besides, I found the idea of someone “doing research on me” disconcerting.

Not long after that, I received a letter from this woman student. Her name was Rebecca McCornac. The letter was thick, over ten pages. One surprise led to another. First, I was taken aback to find the name on the front of the envelope was written very neatly in highly legible characters. So was the address on the back of the envelope.

“Haikei”—the letter began with an extremely polite salutation.

Greetings and Salutations, Uno Sensei:

I trust that you are faring well as the days grow warmer. According to what you have written, Sensei, you do not use an air conditioner in the summer months, not even an electric fan. You must tolerate the heat quite well.

I was amazed by how well she knew me, and my amazement only increased as I continued reading.

Recently I traveled to Kyoto and Nara to see the sights. From there I took a train further south to Iwakuni. At the station, I hired a taxi. ‘Please take me to the writer Uno Chiyo’s house,’ I instructed the driver. He was young and friendly. We chatted along the way and he told me of an American serviceman stationed at the base there who had killed a Japanese bargirl. Sensei, the story he told reminded me of your novel Cheri ga shinda (Cheri is Dead).

Having read this far, I found myself encountering still more surprises, and I realized that the letter writer, this Rebecca McCornac, was no mere foreigner fond of literature.

Once she reached my Iwakuni house, she says, as her letter continued:

I wonder if your father’s ‘Clock Room’ is still intact. I wonder, too, if his beloved stable still exists.

That was it, I had to meet this woman. I know that just minutes ago I had been determined to avoid her. I have to admit even I was surprised by my own vanity!

Once I sent for her, Rebecca-san came to my apartment immediately. She had a childlike face and seemed very gentle, more East Asian than Western. Her manner of speaking Japanese was even more graceful than that of a Japanese woman. She had written down all the questions she wanted to ask me on a piece of paper, which she spread out on the table in front of her. When I saw this, I knew she must be very bright.

“Sensei, of all your works, which is your favorite?” she asked.

“Ohan,”I answered.

“Mine is Kaze no oto (The Sound of the Wind),” Rebecca countered. I wonder if Ohan is just too simple, too vague for foreigners.

Two hours went by, and then Rebecca took her leave. I couldn’t believe the time had passed so quickly, being with her had been so pleasant.

Almost as soon as she had left, I received another letter from her.

Sensei, I admire you as a writer but more than that, I respect you deeply as a person. From here on out, I will work as hard as I can to produce a dissertation that does justice to your sparkling talents. Being able to meet you, Sensei, has made a profound impression on me.

I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Now I no longer think of this letter as being written by a woman student doing research on me. I just pray that Rebecca-san is successful in her dissertation.

Fujin Kōron (Autumn Special Edition, 1984): 22-23.

Becky with Uno’s Signed book

The post On Encountering Icon Uno Chiyo, Part 4 appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

December 20, 2023

On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 3

Naoko and I stood outside Uno Chiyo’s apartment door. My stomach lurched. Desperate to shore up my flagging confidence, I listed all I had done to prepare for this interview. I had read Uno works. Gone over my interview questions until I knew them by heart. And even bought a new dress. I was ready! Kind of….

The door swung open. Fujie-san ushered us into a large, tatami-matted sitting room. It was sparsely furnished and full of natural light.

In one corner, I saw the nearly life-size ningyō puppet that Uno Chiyo had described in her novella The Puppet Maker Tenguya Kyūkichi. The venerable puppet maker had sent it to her in 1943 after their interview. The puppet was standing in a glass case wearing a grey-blue kimono Uno had designed herself.

Against the wall was a large framed print of an Edo-period figure, possibly a courtesan or maybe a wakashū boy. I was too distracted to pay it much attention.

Because, in the middle of the room, leaning against a low writing table, was the famed writer herself.

When she stood to greet us, I caught my breath.

Uno Chiyo and the puppet Oyumi

She was much smaller than I had imagined. Barely five feet, I guessed.

Her hair, dyed a reddish brown, was pulled into curls atop her head. She wore a cobalt blue kimono patterned with small white dots, slightly resembling that of the puppet. Magnified behind her thickly lensed glasses, her eyes twinkled.

When she smiled, her face radiated strength and a touch of curiosity.

What did she think of this tall stranger looming over her in an ill-fitting free-style summer smock of crisply wispy material?

Fujie-san directed us sit on one side of the table. She and Uno Sensei sat on the other. Out of nowhere a woman appeared with a tray of tea and cakes. She disappeared with the bouquet I had brought, only to return a few minutes later with it brilliantly arranged in a large ceramic vessel.

I asked Sensei if I might record our conversation.

When she approved I pulled out my tape recorder and set it on the table between us. Then I unfolded my list of questions, opened my notepad and got down to business.

Sensei, when did you know you wanted to become a writer?

In your stories, you often describe your father as strict and difficult. Has your opinion of him changed over the years?

What was your relationship like with the modernist writer, Kajii Motojirō You spent a lot of time with him at the hot springs of Yugashima.

During the war, many of your friends went to the war front but you never did. Why was that?

What inspired your novel, Ohan?

Of all your husbands and lovers, who was your favorite?

My questions were bold. But having spent time reading through Uno’s collected works, I had grown accustomed to her own frankness. I went down my list and Uno Chiyo responded diligently, at times with a touch of amusement.

Naively, I had thought that she would “spill the beans” to me. Tell me all the little secrets she never admitted in any of her many, many memoirs.

Instead, her replies were nearly word for word exactly as she had written them. I began to get the impression that her scripted memories had taken the place of anything I might have considered “the truth.”

“Sensei, you write that you decided to meet the famous painter Tōgō Seiji because you were serializing a newspaper novel and you wanted to add a scene about a suicide.”

Artist Tōgō Seiji

“Oh yes,” she began immediately launching into the narrative she had told countless times before. “He had just survived a love suicide attempt and I was eager to hear his experiences.”

“And then,” I continued, “when you spent the night with him, you say you slept on his futon which was still stained with the blood from that attempt.”

“That’s right! When I saw that, I was all the more inclined to stay with him as a result. You see, I was that sort of woman.”

“But Sensei, according to the timeline, his suicide attempt was on March 30, 1929 and you didn’t start serializing your novel until December of that year. You met Tōgō in the spring of 1930. Are you saying he kept the bloody futon for over a year?”

“Rebecca-san!” Fujie-san interjected sharply. “Uno Sensei is a shōsetsu-ka, a shōsetsu-ka! She’s a novelist!”

And so ended my quest for the “truth.”

In that moment I was reminded of something the great eighteenth-century playwright, Chikamatsu Monzaemon, had said: “Art is something which lies in the slender margin between the real and the unreal.”

The “truth” was irrelevant. What I needed to appreciate was Uno Chiyo’s creative genius and the way she positioned her fiction between the real and the unreal. As long as I was doggedly picking at facts and timelines, I would never find her art.

Now I understood why she had resisted meeting me for so long. Sitting there with my questions, notebook, and tape recorder, I was performing to a T the tenacious “woman scholar” she had so hoped to avoid.

I snapped off the tape recorder and took a sip of tea. The interview ended and our conversation began.

Rebecca Copeland and Uno Chiyo with the Oyumi puppet, June 21, 1984

The post On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 3 appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.