Rebecca Copeland's Blog, page 8

March 29, 2023

Beginning at the End

This is a well-cited line from Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s 1929 novel Tade kuu mushi (translated by Edward Seidensticker, Some Prefer Nettles). The protagonist’s father-in-law utters the line midway through the novel while discoursing on the beauty of the past. Modernity, with its insistence on scientific rationality and electric illumination, has forever destroyed the mysterious beauty of what is left unsaid.

Perhaps in an effort to retrieve some of those shadows for himself, Tanizaki ends his novel with the suggestion of a new beginning. Readers are left with an ellipsis and are expected to answer the question “what happens next” by using their own understanding of all the novel has provided.

Having worked in Japanese literature for over forty years, I enjoy what is left unsaid. Poet-monk Yoshida Kenkō (1283–1350) anticipates the modern Tanizaki with his celebration of “incompleteness”:

In everything, no matter what it may be, uniformity is undesirable. Leaving something incomplete makes it interesting, and gives one the feeling that there is room for growth. Someone once told me even when building the imperial palace, they always leave one place unfinished. In both Buddhist and Confucian writings of the philosophers of former times, there are also many missing chapters.

In fact, Tanizaki’s Some Prefer Nettles is not the only novel to end enigmatically. Many of the most important works of Japanese literature do.

The Tale of Genji ends with a knock at the door. We are not told who it is. Enchi Fumiko’s Masks ends with the protagonist’s right arm lifting up and then stopping “as if suddenly paralyzed, [where it] hung frozen, immobile, in space.” Kokoro, Natsume Sōseki’s masterpiece, ends with Sensei’s Last Testament. What happens next? We are not told. But throughout these works, we’ve been given enough details to allow us to draw our own conclusions.

The conclusions that I imagine for these works may differ from yours, it may change as well upon additional readings. In this way, the endings of Japanese works make demands on readers. We are invited to enter the narrative process, to continue reading even after the last page has been turned. We participate in the afterlife of the work. One may say we even write it. My students often find the endings cryptic. They want more.

“What happened?” they ask. “I didn’t get it.”

I’ve always enjoyed that about Japanese narratives. There isn’t a standardized “it” to get.

As explored in my earlier post, I find writing beginnings and endings particularly challenging. Of the two, endings are even more difficult than beginnings. By the time I come to the end, I am depleted. And I get frustrated at the unsatisfied reader who frowns at me, sighing, “Is this really the best that you can do?” Imaginary though said reader may be, I want to shout: “Haven’t I already told you everything you need to know? After all, I conceived you as a clever reader!”

Still, readers come with all kinds of experiences and expectations. We can’t possibly satisfy them all. As a glance at my readers’ reviews will make clear, I certainly don’t. Many readers found the conclusion to The Kimono Tattoo unsuccessful, noting: “the ending left me hanging.” They wanted more.

As with the beginning of The Kimono Tattoo, I rewrote the ending any number of times. In some revisions, I made everything crystal clear: the murderer, the fate of characters, the owner of the blue eyes in the last line. But the more obvious the conclusion became, the more uncomfortable I grew.

Missing chapters, empty spaces, innuendo, and incompletion engage our imagination. They offer endings that truly become beginnings.

Featured photo: Nanzenji Gate, where The Kimono Tattoo concludes

The post Beginning at the End appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

March 15, 2023

In the Beginning There Were Pigeons

“In all things, it is the beginnings and the endings that are the most interesting.”

Or, so wrote Japan’s famed medieval poet-monk Yoshida Kenkō (1283–1350). Kenkō illustrated this bit of aesthetic wisdom with advice on how to appreciate a romantic affair.

The beginning of the affair is buoyant with anticipation, and the end, poignant with memories. The middle, according to Kenkō, is rather pedestrian. “Is the love between a man and a woman to be understood only in terms of the times they are together?”

He also applies his dictum to the enjoyment of cherry blossoms and the moon. Should we only enjoy them when they are full? Isn’t it the waiting, the hoping, far more meaningful, more potent with imagination? Once the blossoms have fallen and the moon has set, isn’t it the memory of them that tantalizes us? Kenkō would think so. It’s not that the cherry blossoms in all their glory or the full moon in a cloudless sky are not breathtaking. But when we see so clearly what is in front of us, what is left to dream about?

Perhaps Kenkō’s evaluation of “beginnings and endings” could apply to writing as well. I always struggle over the beginnings and endings in any work I write, whether academic or creative. The beginning has to capture the reader’s attention and gesture towards the unfolding of the plot or argument. The beginning must tantalize the reader about what may lie ahead, what is yet unseen. The conclusion needs to wrap it all up and send readers away with the story still playing out in their mind. They need to experience a sense of catharsis and growth. In this post and the next, I would like to reflect on the beginning and ending of The Kimono Tattoo.

Where to Start?Here’s the way The Kimono Tattoo began, before it didn’t:

I was watching the pigeons when the doorbell rang. I hadn’t noticed before the way they appeared to divide into different squadrons. As soon as one squadron of five or so pigeons set down on the electrical wire outside my second-floor window, the second squadron would take flight. I hate pigeons. But I enjoyed watching them soar up into the unbelievably blue April sky, wheel out over the Kyoto zoo, and temporarily block my view of the ritzy Miyako Hotel on the far side of Higashiyama. As they turned for home, their wings would wink iridescently. For pigeons, they were uncommonly beautiful. Once landed the earlier squadron would return to the skies. Pedestrians below, tourists mostly—marching noisily between Nanzenji Temple and the zoo—rarely thought to look up at the pigeons perched dangerously above their heads. I always had a chuckle when one noticed too late, dabbing desperately at a desecrated head and glaring upward at the delinquent bird. Usually the victims were raucous high school boys. The one singled out by the pigeon missile would be harangued by his unscathed buddies who would blot at his once perfect coif with hand towels and handkerchiefs. But a few weeks ago, when a pretty junior high school girl was globbed by a bird, I slipped down the stairs and offered her a damp towel. I am not sure what brought her more trauma: being shat upon by a pigeon or being set upon unexpectedly by a red-headed foreigner. “Thank you,” she managed to sputter in something resembling English, despite the fact that I had spoken to her from the start in Japanese. “Dou itashimashite,” I continued. “And please, keep the towel.” I closed the door.

And, so the chapter continued.

I liked the pigeon opening. I worked on it for a few years as the novel emerged, adding to it and subtracting from it. This was the beginning that led me to the discoveries I would later make in the novel, as the storyline slowly unfolded, folded, and then unfolded again, before my eyes. I thought the opening established the location, Ruth’s sense of isolation and difference, her sensitivity to the space around her, and her self-deprecating-snide humor.

In October 2019, I submitted The Kimono Tattoo to the contest Pitch Wars, for debut novelists. The successful applicants would win mentorship by seasoned writers who would help them revise their manuscript and secure representation with an agent. I “pitched” to a number of writers. Of these Kellye Garrett and Mia P. Manansala, working as a team, were kind enough to provide feedback. They encouraged me to revise the opening:

We want to jump straight into the story, especially for a mystery. Maybe also take out the non mystery related stuff about the dance teacher and Nakatas relationship with her parents here. You’re throwing a lot of info at us in these first pages and it might be easy to get lost/overwhelmed. You can always factor these details in later. It does end on the right spot.

Good advice. But, as my earlier posts on editing have revealed, it’s not easy to know what to let go. So, I spent several months trying out new beginnings. In one version, I start with the discovery of the tattooed body. That was very dynamic. But it changed the mood of the story and de-centered Ruth. Eventually, I found a way to begin with the arrival of the mysterious woman who asks Ruth to translate the novel by the long-forgotten author, Tani Shōtarō.

Goodbye pigeons.

And yet, the pigeons did not disappear entirely. They remain in the title of the chapter as a trace of my original opening. It was the image of the pigeons, after all, that carried me into the world of The Kimono Tattoo. It is the talismanic power of birds that identifies each chapter of the novel.

The post In the Beginning There Were Pigeons appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

March 1, 2023

Edited Out, Part Four: Tanizaki and the Homeless Cuckoo

Editing a manuscript can be painful. You have to be willing to cut passages that you have labored over for days, sometimes longer. Some great writer equated this process to “murdering your darlings.” You’ll hear some attribute this quotation to Ernest Hemingway. Others will say it was William Faulkner, and I suppose Faulkner would be more likely to say “darlings” than Hemingway. Then again, some writers claim the original called for “killing babies.” And others will quote the line as to “kill children.” It can get pretty gruesome.

When my publisher told me I needed to cut nearly 20K words if I wanted her to consider my book, I was willing to go on a murderous rampage. When the editor I worked with suggested cuts, I felt little hesitation. Sure, many of the cuts represented days of labor. But I did not feel any particular attachment to the edits she proposed. The cuts were just words. They were not my children, or babies, or even my darlings.

And yet, there was one particular passage that I felt some reluctance to relinquish. It occurs in “Chapter Six: Cuckoos.” In that chapter Ruth stops by Hōnen-in on her way to Yuriko Daté’s house. Hōnen-in is one of my favorite temples, quiet and sedate, it houses Tanizaki Jun’ichirō’s tombstone in a small, nondescript graveyard. I like to explore the temple grounds whenever I return to Kyoto.

Here’s what was cut:It took close to twenty minutes to get from my house to the start of the Philosopher’s Path. The hill up to the path from Shishi-ga-tani was steep. Cobblestones lined the last few feet of the slope at Nyakuoji Shrine and they were tricky to navigate. I was glad to reach the flat, graveled pathway.

The path followed a canal that was built in the late nineteenth century as a way to bolster the faltering economy in Kyoto. The city was entering a period of depression—both financially and emotionally—if cities have emotions—because the imperial court, which had been in Kyoto for eons, was moved to Tokyo. I suppose Kyoto-ites felt they’d been “de-throned” from their positions as arbiters of culture.

Lake Biwa Canal which flows along the Philosopher’s Walk, Kyoto, Japan. Image by PRST, Wikimedia Commons

And so city officials devised a number of projects to keep the city vitalized. One was the construction of the Heian Shrine—the resplendently vermillion edifice close to the Kyoto zoo—which it predates by only eight years. Another was the Biwa Canal which runs, largely through underground tunnels, from Lake Biwa in Shiga Prefecture all the way to Nanzen-ji Temple. The Philosopher’s Path was a happy consequence of that project. Cherry trees lined the path, and when they were in bloom, the one-mile stretch became a mecca for blossom seekers.

The blossoms had long fallen now but the path was still full of people in search of a quiet place to stroll. Most were tourists: Europeans with big bellies and bigger cameras; older women with sun parasols spread one alongside the other like a mobile canopy; and inevitably middle-aged men walking alongside mini-skirted young women who were clearly there for monetary gain. The men looked deliriously happy—walking with vigor and pride while the women, towering over their escorts in their high heels, just looked bored as they texted messages on their cell phones with dexterous thumbs.

Daté lived in a modest estate wedged between Honen-in, one of the most peaceful temples in Kyoto, and Ginkaku-ji, one of the most touristed. Since I was a little ahead of schedule, I decided to stop off at the Hōnen-in to enjoy the quiet and to visit the writer Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s grave, tucked along the back row of the cemetery.

Hōnen-in Temple Gate, author’s photograph.

I followed the stone path past the rustic temple gate and into the graveyard, climbing the steps to the right until I came to the Tanizaki plot nestled under the dangling branches of a large weeping cherry. Tanizaki had designed his own headstone. Unlike the other graves with their geometrical and mostly oblong shapes, Tanizaki’s grave marker was a natural stone with the character jaku, meaning “tranquility,” carved into the surface. The character was in Tanizaki’s “hand.” His calligraphy had been stenciled on the stone and then carved. The stone next to Tanizaki’s marked the grave of his wife’s younger sister and her husband. The stone was similar, but the character carved upon it was kū or “empty.” When read together kūjaku meant void or emptiness.

One of Tanizaki’s grave stones. This one reads “jaku” or “tranquility.” Author’s photograph.

I was always bemused by the heavily Buddhist flavor of Tanizaki’s last words. Known for the playfully sadomasochist twists in his stories, I had thought he’d be buried under a carving of his wife’s lovely foot—much as he had depicted in one of his last works, The Diary of a Mad Old Man. But I guess in Tanizaki’s case, fiction was stranger than truth.

The spot did put one in mind of Buddhist enlightenment, though. With trees that towered high above the stones, the plot was dark and a little damp. A stream gurgled nearby and I could hear a knot of frogs calling to one another intermittently. High above a cuckoo trilled, full throated and sweet. I loved the cuckoo! They were believed to beckon the summer months. For this and other reasons they had been a favorite with poets.

You would not have to look far for a waka or haiku verse celebrating the cuckoo. I liked the fact that the way to write the word “cuckoo” in Japanese was not fixed. You could write the name with the graph for “time” and “bird,” for example. But my favorite was the string of three graphs that meant, roughly, “homeless.”

The homeless cuckoo and I had a lot in common. Standing in front of the gravestones reminded me, that some people saw the cuckoo less as a harbinger of the summer season and more as a conduit for the dead. They heard a mournful quality in the song—the longing of the spirits of the dead to return to their loved ones. A deliciously chill wind swept across the back of my neck. I loved ghost stories! But, it was time to leave the graveyard. The thicket mosquitoes were beginning to bite.

End of cut.

Each chapter is titled after a winged creature, mostly birds. The chapter where this cut was made was titled “cuckoo” largely after the above scene. That meant, I had to work “cuckoo” in elsewhere. In the final version of The Kimono Tattoo, Ruth hears the cuckoo call as she is sitting on the veranda with her friend Yuriko Daté.

Here’s the way it reads:

Masahiro came out after us and was lighting the lamps in the stone lanterns. It was too early in the year for fireflies. Still the soft glow of the lanterns filtering between the pine needles and maple leaves seemed magically romantic. I suppose the late afternoon saké helped make the scene more intoxicating. The cry of the cuckoo rose out of the bamboo thickets behind Daté’s gate.

It was time to leave. I had taken up too much of Daté’s time.

Thank you for letting me take up your time with this edited out section.

The post Edited Out, Part Four: Tanizaki and the Homeless Cuckoo appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

February 15, 2023

Edited Out, Part Three: Detouring into the Kyoto Prefectural Library

I continue with the series of scenes that were edited out of The Kimono Tattoo. The edits always improved the narrative flow, dramatically. Narrative timing is a skill I am still learning.

In the early stages of writing The Kimono Tattoo, I understood that readers expect mystery fiction to move quickly. But I have long admired the way Kirino Natsuo, Miyabe Miyuki, and Patricia Cornwell slow the narrative down here and there with details and force the reader to pause. As a result, the authors build in anticipation. I also knew that readers could just rush over those places if they couldn’t bear to wait, and I suspected my readers would skim if the details were annoying.

I admit that I had a hard time controlling my desire to explain. I suppose all those years of lecturing, of expounding on contexts and histories for my students, made we want to do more telling than showing. And boy did I tell a lot.

More than once, I realized I was losing control of the narrative. There’s a scene where Ruth is running from men she suspects of killing her friend, Yuriko Daté, and as she rushes past a certain temple, she pauses in her mind to dredge up its illustrious history! You will notice in the excised excerpt below, I make a concession for Ruth’s prodigious knowledge!

In this scene, from “Chapter Five: Cranes,” Ruth visits the Kyoto Prefectural Library to try to find out more information about the Tani Kimono family. I’d gone past the library numerous times but had never noticed it. To this day, I’ve not ever been inside. But I must have spent the better part of an afternoon digging up the detail found below and struggling to describe the building, researching the “Vienna Secessionist Movement” and getting lost down architectural wormholes. Most of what I wrote ended up on the cutting room floor! But, I was particularly proud of this sentence: “The addition loomed up behind the original building, reflecting the sky, as if the future were pressing down on the past.”

Kyoto Prefectural Library, October 2016 Credit: Degueulasse

Here’s what was cut:

The Kyoto Prefectural Library was housed in a stately building erected in 1909 to celebrate Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War. The architect, Tadeka Goichi, had trained in Europe, and the library—with its harmonious lines offset by decadent gold flourishes and inscriptions bore the traces of the Vienna Secessionist Movement. A number of years ago, feeling the need for more space, the library added a glass box extension that looked like it was designed by a construction company. The addition loomed up behind the original building, reflecting the sky, as if the future were pressing down on the past. I was not that crazy about either building. But the library itself was surprisingly airy and open.

Kyoto trivia came naturally to me. Well, that’s not entirely accurate. I had worked hard to acquire all the tidbits of information. During the summer between college and graduate school I had returned to Kyoto, eager to reacquaint myself with my familiar haunts. My mother arranged for me to take a job as a tour guide leading groups of American tourists through the city.

I had to pass a qualification exam that had me memorizing page after page of historical facts, dates, names, and other useless bits and pieces. They were useless because the tourists I squired about were inevitably less interested in facts and figures and more inclined to ask about the everyday behaviors and manners they found curious.

Why do women cover their mouths when they laugh? Why aren’t there paper napkins in the restaurants? So accustomed to these manners and events myself, I had never even noticed them.

It was much easier to reel off facts than it was to answer what seemed obvious. Unable to off load my collection of tidbits completely that summer, I found the information I had so carefully stocked away resurfaced when I least expected it.

Yes, Ruth, I chided myself, Kyoto Prefectural Library is a resplendent building. Now will you get on with it!

End of cut

Poor Ruth. It’s hard to be such a know-it-all. In The Kimono Tattoo my eagerness to share “my Kyoto” with readers led to an often overly encyclopedic approach to scene setting. Some of my readers have said they enjoy all the detail. Others complain that the narrative plods. I take heart in David Cozy’s review of the novel, published last spring in the Kyoto Journal.

That it’s never easy to stop turning the pages of Copeland’s novel is a testament to her skill, especially when one considers the chances she has taken. In choosing, for example, to teach her readers about Japan, about Kyoto, and about kimono, she runs the risk of being pedantic in the worst as-you-know-Bob style. She manages, though, to fold what she teaches us into her narrative in such a way that, far from slowing her story to a slog, it instead makes the feverish page-turning a richer experience.

The post Edited Out, Part Three: Detouring into the Kyoto Prefectural Library appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

February 1, 2023

Edited Out, Part Two: Dance and the Dalliance in the Yoshiwara

Here’s another scene from The Kimono Tattoo draft that ended up on the cutting room floor. Again, we have reference to Hiratsuka Raichō, but also to a controversial feminist painter, an ancient Japanese legend, and the politics of protest in postwar Japan. Why did this get cut? What do the references tell us about the main characters?

In this scene, also from “Chapter Four: Crows,” Ruth is conversing with her dance teacher who is based on Nishikawa Senrei Sensei, who choreographed her own, original dances, known as sōsaku in Japanese. When I studied with her in Kyoto, from 2004-2006, I saw her perform two of her original pieces. One was drawn from the life of Camille Claudel and the other a retelling of author Mori Ōgai’s encounter with a German dancer (upon whom Ōgai based his early work “Dancing Girl” or Maihime, 1890).

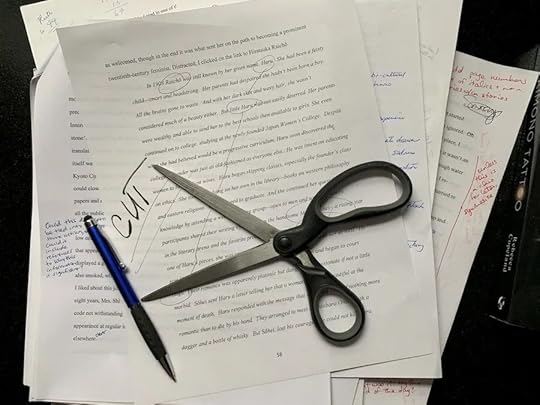

Cutting The Kimono Tattoo; author’s photograph.

Here’s what was cut:

“Of course. They make excellent kimonos. Or at least they used to. I have a few myself. They are good for performance. A Tani Kimono is always supple and the colors are deep so they show up well on stage. Years ago the family was a great patron of the school and would donate kimonos for our performances. I even collaborated once with Satoko Tani, back when she was more involved in the business. But it’s been years.”

“You worked with Satoko Tani?”

“Once, yes. I choreograph my own dances, you know. And I worked with Satoko on creating a kimono for one of my pieces.”

“I didn’t know you choreographed your own works, Sensei.”

“Oh, certainly. That’s the only way to keep the art fresh. The one you’re learning, Ruth, is only a hundred years old or so. All of the dance masters create individual works at some point, and I’ve done quite a few. The last one I did was so controversial, though, I haven’t had the energy to take on another project.”

“Controversial? Why?”

“Honestly, I don’t understand it myself. It was a fantasy piece about the dragon princess. She fell in love with the Japanese god, Hoori, and gave birth to his child. But she left him when he broke his word to her and spied on her in childbirth. That’s when he saw her true form resembled a crocodile. She was shamed, and so she left him and her newborn to return to her undersea world. Well, my dance starts at that point. What happens to her when she returns? I have her swimming the seas to unite with other Asian sea deities. You can imagine how magical the set would be for the dance. I had banners and screens set up with electric fans blowing behind them to make them waver and tremble on stage like water.”

“It sounds wonderful. How could that be controversial.”

“Oh, it’s just so annoying. The controversy erupted because the dragon princess—who is worshiped as the grandmother of Japan’s first emperor Jimmu—swims the seas with goddesses from Korea and South China and the message is that we are all born from the sea. We are all sisters. And at least for women, there are no national boundaries, no national languages, or identities. We are one in our multitude.”

“But that sounds fantastic.”

“Well, there were right-wing radicals who were offended that I had linked the grandmother of the Japanese imperial court with other Asians, particularly with Koreans. So they staged very boisterous protests in front of the theaters where we performed. At the last performance in Tokyo they even threw stones and trash at us as we went into the theater and a few of my young assistants were hurt.”

“That’s awful.”

“We were all traumatized by it. Now I will only perform that dance overseas.”

“Did Satoko Tani collaborate with you on that dance?”

“No. I got off track, didn’t I? My collaboration with Satoko was much earlier than that. I was inspired by the life of Hiratsuka Raichō and decided to plan a dance to commemorate her.”

Two encounters with Raichō in one day. I felt somewhat smug with knowledge when I asked Sensei if she had planned her dance around the failed love suicide. The incident seemed tailor made for romantic reinterpretation.

“No, that was just the silly misadventure of youth. She wasn’t even really Raichō then. No, I was interested in the interaction she had with women in the licensed quarters. She and a group of her Bluestockings went to the Yoshiwara in Tokyo and spent the night with a famous courtesan there. I wanted to capture that encounter between the New Woman and the woman of the past. Only in my interpretation, both Raichō and the courtesan come to see they are not very different. Raichō isn’t all that new. And the courtesan defies the stereotypes about her.”

“Did you play the role of Raichō or the courtesan?”

“I played them both. I used a mirror and other stage techniques. But much of the success of the production depended on the kimono Satoko designed for me. I had to be able to change costumes quickly.”

“You mean like on the Kabuki stage where the actor slips out of one costume and steps into another right before your eyes?”

“No, Ruth, this is Japanese dance. We don’t rely on tricks like that! But I had to be able to switch from one kimono to the next in the matter of seconds it took me to walk from one side of the mirror to the other. I may have a video tape of the performance downstairs if you would like to see it.”

I could tell my teacher was ready to wrap up our conversation. But I needed to know more about Satoko. I played my “gaijin card” and pretended not to pick up on her cues.

“What was it like to work with Satoko?”

“She was brilliant. She knew exactly what I wanted—even before I knew what I wanted! She came to my studio with pattern books and sketch paper, and we roughed out the designs together. She had already read up on the “Yoshiwara tōrō” incident, or the Dalliance in the Yoshiwara. It had been sensationalized in so many of the newspapers of the day, she didn’t have any trouble finding information—most of it heavily critical of Raichō. And she knew almost intuitively the angle I was pursuing with this.

I was trying to get inside Raichō and the courtesan to understand how they felt meeting each other and how their hearts communicated to one another as women. She designed one two-sided kimono. And it was perfect. See, Ruth. That’s what I mean about doing things the old way. Satoko was not herself old-fashioned, but she understood how to listen to a customer—even when the customer wasn’t saying anything. Or wasn’t able to say what she really wanted.”

End of cut.

But why cut this scene? By this time, readers have already ascertained that the dance teacher in The Kimono Tattoo is a creative artist and a feminist. We do not really need such a long digression to drive the point home. If anything, the scene (as with the one cut in my earlier post) distracts the reader. Who is the main interest in this scene? Satoko Tani or Hiratsuka Raichō?

I absolutely loved the way one historical figure after another crept into my story—Raichō, the author Mori Ōgai, and the visual artist Tomiyama Taeko. I couldn’t stop them. As I was writing they pressed forward.

“That’s right,” I thought to myself as I wrote the conversation with the dance teacher. “If she created a sōsaku or original dance based on the legend of the Dragon Princess, wouldn’t it resemble one of Tomiyama’s paintings?” One idea led to another in an absolute torrent. I thought the deluge was good because I wanted the novel to read like layered fabric, with one story giving way to another. The torrent of ideas buoyed my layered design.

At some point, I came to realize, if you add too many fabrics, the ensemble becomes too heavy to wear. Whoever is clothed in such a garment will be unable to move. I needed to pull back, trim away some of the layers so that my novel could breathe.

I still have the scraps of fabric, the ideas, the conversations folded neatly away in my writer’s drawer. If I am able to use them later, I’ll know where to find them.

The post Edited Out, Part Two: Dance and the Dalliance in the Yoshiwara appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 18, 2023

Edited Out, Part One: Hiratsuka Raichō and the Shiobara Incident

When I first sent Melissa Carrigee of Brother Mockingbird Publishers my manuscript, I had already culled ten thousand words. But it still weighed in at a hefty 117K words. I was happy to chop off more, but I just didn’t know how to take it further. So, I hired a copyeditor, something I now realize I should have done much sooner, and with her help we whittled away another 18K.

Later, at a writers’ discussion hosted by Kathy Murphy of the Pulpwood Queens, I told the ZOOM group about the edits. Fellow writer Sara Stamey suggested I share some of the excised sections here on my blog. I thought her idea was wonderful. It allows me to revive some of those “deceased darlings” and it also alleviates me from trying to think up ideas for a post. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy sharing my memories, reviews, and such. But, there are times when it is difficult to balance blogging with grading papers, preparing lectures, chasing down plumbers, and all the other real life stuff.

So, over the next few posts, allow me to share some of the scenes that ended up on the cutting room floor.

The following is from “Chapter Four: Crows.” Ruth has just learned from a TV news report that a body has been found alongside a river in Shiobara, described much the same way as in the novel she read the night before.

Here’s what was cut:

Quickly depositing my dishes in the sink and pouring myself another cup of coffee, I clomped upstairs to turn on my computer. Maybe the news outlets had picked up the story by now. I scanned the usual sites: Yomiuri, Asahi, Mainichi, Japan Times. But as of yet, none had anything to report.

I typed in “Shiobara” and “Incident/Accident/Death.” That led me to page after page on Hiratsuka Raichō and her failed suicide attempt with Morita Sōhei—the one the innkeeper had mentioned to Tani. That event had taken place in 1908! Not exactly breaking news! But I guess it was still much talked about in Shiobara—and undoubtedly brought the area the kind of notoriety that also brought customers. The notoriety it brought Raichō was not quite as welcomed, though in the end it was what sent her on the path to becoming a prominent twentieth-century feminist.

Hiratsuka Raichō (1886–1971) Credit: National Diet Library, Tokyo, Japan.

Distracted, I clicked on the link to Hiratsuka Raichō.

In 1908 Raichō was still known by her given name, Haru. She had been a feisty child—smart and headstrong. Her parents had despaired she hadn’t been born a boy. All those brains gone to waste. And with her dark skin and wavy hair, she wasn’t considered much of a beauty either. But little Haru was not easily deterred. Her parents were wealthy and able to send her to the best schools then available to girls. She even continued on to college, studying at the newly-founded Japan Women’s College.

Despite what she had believed would be a progressive curriculum, Haru soon discovered the college’s founder was just as old-fashioned as everyone else. He was intent on educating women to be excellent wives. Haru began skipping classes, especially the founder’s class on ethics. She took to studying on her own in the library—books on western philosophy and eastern religions. She managed to graduate. And she continued her quest for knowledge by attending a weekly reading group—open to men and women—where participants shared their writing efforts.

When the handsome Morita Sōhei—a rising star in the literary arena and the favorite protégé of the great writer Natsume Sōseki—praised one of Haru’s pieces, she was smitten. And it seems he was attracted to her as well. He sent his old-fashioned wife home to the country with his children and began to court Haru.

Their romance was apparently platonic but dangerously passionate if not a little morbid. Sōhei sent Haru a letter telling her that a woman was most beautiful at the moment of death. Haru responded with the message that she could think of nothing more romantic than to die by his hand. They arranged to meet at Shiobara Onsen with a dagger and a bottle of whisky.

But Sōhei, lost his courage. He could not kill Haru. Their plot was uncovered and both were dragged home to their respective families and the ensuing media circus.

Love suicides were prominent in the past—but only among the lower classes. Here two members of the elite had contemplated something so unseemly. Sōhei had Sōseki to cover for him. The distinguished writer urged his young protégé to turn his experiences into a novel, and Sōhei did, detailing for all who cared to read his work how he and Haru had misbehaved.

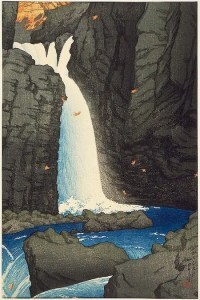

Yūhi Falls at Shiobara (Shiobara Yūhi no taki), from the series Souvenirs of Travel I (Tabi miyage dai isshū) by Kawase Hasue, Wikimedia commons

The honesty with which he revealed his inner anguish earned Sōhei positive accolades, while it earned Haru contempt. She was labeled a hussy—a prime example of why education corrupts women. Her name was stricken from the Japan Women’s College alumnae lists. And she was forced to leave town.

All expected Haru to hide away in shame. She did hide away briefly in Kamakura. Where she meditated and studied and became even more determined to work for what she believed was freedom from an unfair family system. She took the name Raichō—from the bird that lives a solitary life, high in the peaks of the Japanese Alps—and she returned to Tokyo to become the founder of an influential women’s magazine.

Towards the end of his life Morita became a member of the Japanese Communist Party. He died of liver disease. Raichō, on the other hand, became active in the Peace Movement following World War II and founded the New Japan Women’s Organization, which remains active to this day.

The page was complete with photos of the hot springs, Sōhei, and Raichō—who I found very beautiful, despite the negative press. At least her trip to Shiobara ended well. Not so for Tani Satoko. She had gone to meet her brother—not a lover intent on releasing her beauty through death! But what had happened?

AND, CUT!

Wow!! Talk about an info dump and digression all rolled into one.

This one was perhaps the kindness cut of all.

The post Edited Out, Part One: Hiratsuka Raichō and the Shiobara Incident appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 4, 2023

Home is Where the Views Are

I can’t remember when I decided I would retire to North Carolina. The idea came on gradually. Maybe it was after I spent that month in the Tennessee cabin writing the first draft of The Kimono Tattoo. It was only a month, but I felt such an affinity for the hillsides and vistas there. The late afternoons on the rough-hewn porch watching the sun set; the morning rambles over the old logging trails with my dog, Wilson. I found myself communing with my parents and with the person I wanted to be.

It was the perfect escape from the world outside. The political battles between Romney and Obama were heating up. Fundamentalists had taken over the government in Egypt and death tolls continued to rise in Afghanistan and Syria. Back at the university, there were hirings and firings to deal with, new programs, old programs, and reports to write. But none of that mattered much as I stoked the fire in the wood-burning stove, coaxing warmth into the darkening room.

During the following summers, when I wasn’t in Japan, I would visit my brother in Boone, NC. While he traveled to different music festivals, I’d stay with his dogs. Watching the sun slip behind the rim of Grandfather Mountain, I knew I belonged in the Blue Ridge.

More importantly, perhaps, I knew I didn’t belong in St. Louis.

It’s not that I was unhappy in the Show-Me State. I’ve lived here for over thirty years. Longer than I’ve lived anywhere in my life. I’m comfortable here I love my house and garden. I may bicker a bit about campus politics, but all in all, my work at Washington University has been fulfilling.

Still, St. Louis is not my home. It never has been.

And so, I decided—while I was still a decade or so from retiring—I would find my retirement home in the Blue Ridge. I would plan ahead. I would start now. Even I was surprised by my certainty.

Daily, almost hourly, I scoured the real estate listings on line, putting electronic hearts on the property I wanted to see. My own heart would break a bit when the property disappeared before I could find the time to drive back to North Carolina.

My brother helped me engage a realtor, and I began making trips to Boone as often as possible to look at property. Fall break, spring break, summer break, I drove with my realtor from house to house, never finding what I wanted.

Shortly after classes ended in May 2018 I saw a house on one of the listings. It looked like a contender. I was more partial to contemporary architectural styles than I was to the rustic. Log cabins seem to prefer the country look with quilts and pie safes and such. Contemporary vibes suited my Japanese décor better.

This house was eight-sided, with wall-to-wall windows. The interior was bright and airy with exposed beams rising high into a vaulted ceiling. I arranged to drive to NC in May and Billy, the realtor, put the house on our tour schedule. First he took me to a number of other listings. They were each okay for a short stay, but not at all what I wanted for my forever house.

And then we visited the eight-sided contemporary. I thought the exterior was kind of ugly, frankly. It had a greenish shingle siding and little to no landscaping. But once we walked inside, the exterior hardly mattered. What mattered were the views. And the house was nothing but views.

The kitchen was nice, the bath was fine. But the open living room faced east out over Jefferson, North Carolina with a clear line to Mount Jefferson, Big Phoenix, Little Phoenix, Paddy Mountain, and beyond in layer after layer of shimmering purple and blue ridges.

“What do you think?” Billy asked.

“I could stand here all day.”

I hated to turn from the window, but we had another viewing in Lansing. I told Billy I didn’t need to see more. He had made an appointment, though, and the owner was expecting us. He wanted to honor his commitment, so off we went to see a house that was chock-a-block with knick-knacks and country frills and so boxed in I felt I could hardly breathe. We left as soon as we could do so politely, promising the owner we’d be in touch if we had further questions. I knew we would not.

Billy dropped me at my brother’s house.

“Find anything?” Luke asked, rather hopefully, when he returned from work.

“I may have. I’d really like you to see it, though. Do you think you might have time tomorrow or….”

It was nearing six o’clock. I knew Luke was tired and ready to melt into the couch with a beer and the latest episode of NYBD Blue. We’d been binge watching the show for some time.

Eager to tell him about my find, I explained the location.

With a grin, he said, “Come on. Let’s go now.”

I worried about the construction on Highway 221. When Billy and I drove out to the house earlier, it had taken considerable time. If we left now, wouldn’t it be too dark by the time we got there?

“Nah,” Luke assured me. “It’ll still be fine. I know a shortcut.”

He took a dirt road that wended its way down to the New River and then followed it for a number of miles. We hardly met any other car. Luke put a Lucinda Williams CD on and we rolled the windows down enjoying the mild breeze blowing through the pines. Frogs were singing in the marshy lowlands and the setting sun tinted the surrounding hills a soft mauve. I held my hand out the window and surfed the wind—up and down, up and down—as Lucinda Williams sang about heartbreak.

My heart was full.

Something about that moment, the frogs, the pines, the rush of the river, my brother singing along, and I knew I was home.

Once Luke saw the house, he confirmed my hunch.

“This is a great house, Beck!”

And so it is.

I still feel like I can stand here all day, basking in the beauty of the views. Now, all I have to do is retire…

The post Home is Where the Views Are appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

December 21, 2022

My Tokyo House of Horrors

“Okay. Here’s a listing that might work!” The agent pushed a sheet of paper across the desk to me.

“The landlord specifically says he wants to rent to foreigners.”

That was refreshing news.

My husband, Dennis, and I had been in Tokyo for nearly a week now, trying to find an apartment. We were growing frustrated in the cramped “business hotel” near Ueno Park as one day led to another, and we still hadn’t lined up a place to stay. Landlords, who sounded encouraging on the phone, balked when the agent told them we were foreigners. Either that or the rent was beyond what my 1983 Fulbright dissertation research stipend would cover.

But this place sounded too good to be true: an entire house, fully furnished, modest rent, and no “key money,” the expensive “gift-to-the landlord” usually required when renting in Japan, sometimes the equivalent of over one month’s rent. It’s the bane of the visiting graduate student’s budget.

“What gives?”

The agent shrugged. “He says he likes Americans.”

Mr. Miyahara confirmed that when we met him later that afternoon.

“I want to help Americans because Americans helped me after the war.”

Over the year he shared dribs and drabs of his war story with us. Apparently, he had been taken prisoner by the Allied Forces as WWII was nearing its final months. “Thank god it wasn’t the Russians,” he told us. “They would have killed us all.” The American soldier he interacted with the most had treated him kindly.

“At night he would share his food with me. I might have starved if not for him.”

Mr. Miyahara’s eyes had faded with age to a soft, watery grey. He was slightly built and moved with an unhurried elegance. His salt-and-pepper hair fell evenly to his collar and was almost always capped with a knitted blue beret.

He was in his early seventies. His wife, his second wife, was in her early forties. She was gracefully tall with a cloud of dark hair and a gentle smile.

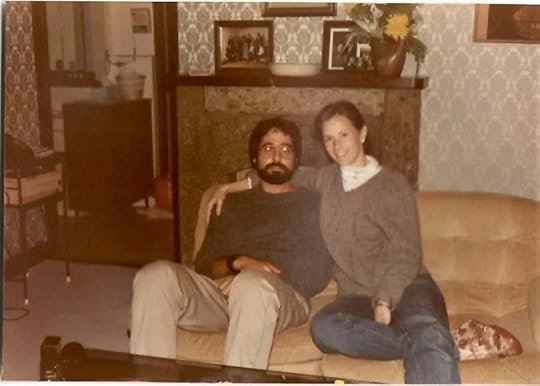

In the Sakuragaoka house with Mr. and Mrs. Miyahara, August 1983. I am on the left, my sister, Judy, in the middle. Author’s photograph.

The house had been home to Mr. Miyahara’s first wife and their family. It was nestled into the Sakuragaoka neighborhood of Setagaya Ward, a quiet residential area near Baji Park and surrounded by vegetable fields that smelled of fertilizer.

Once a tasteful property, the house was two storied with five bedrooms, a study, a family room, a well-appointed kitchen, and a sizeable bath. The encircling garden was tangled and overgrown. Bamboo crowded the entranceway, casting dark shadows over the crumbling sidewalk.

“Will you be able to live Japanese style?” Mr. Miyahara asked us as he slid open the front door.

We nodded our agreement, and after we stepped out of our shoes, he led us into a spacious ten-mat tatami room. He pulled two sets of futon bedding out of the oshi-ire closet.

“You’ll sleep here,” he said. “And you can watch TV in this room,” he pointed back into the Western-style room we’d just walked through with its soft lavender carpet and wallpaper of blue arabesque. The room was heavy with furniture, low couches and dark wood curio cases. In the corner was the television, larger than any Dennis or I had ever been able to afford.

“The kitchen is there and the bath is next to it.” He pointed to the other rooms.

“I have two conditions,” he said.

Ah, I thought. This is why he likes Americans. We are short-term residents and desperate enough to accept “conditions.”

“My first wife’s butsudan altar is here, and I’ll need to stop by to pay my respects.”

He took us back into the Japanese-style room and opened one of the smooth paulownia wood cabinets to reveal a deep alcove containing a black lacquered altar with gold leaf walls. The portrait of a woman arose from the shadows. Mr. Miyahara brought his hands together just under his nose and bowed before closing the cabinet doors.

It’s a little strange, I thought, for us to sleep in the room with Mr. Miyahara’s first wife, but if he doesn’t mind, why should we?

“And the second,” he said, “is that you share the bathroom with the upstairs tenant.”

This was the first I had heard of another tenant. No wonder the rent was so low.

“He works at the post office. He’s gone all day.”

Dennis nudged me when he saw the surprise on my face. I quickly translated what Mr. Miyahara had said.

“It’s a big house, after all,” Dennis said, unfazed. “I don’t think we can turn down a deal like this.”

He looked out at the overgrown garden, already feeling relieved to be freed from the tiny hotel room.

Dennis pets the local alley cat next to the sliding glass doors off the living room. Author’s photo.

“Watanabe-kun will use the back entrance,” Mr. Miyahara quickly added, sensing my hesitation. He led us to a small door between the kitchen and the green-tiled bathroom with its deep sunken tub. From the back door there was a direct path to the second-floor stairway.

“I’ll introduce you the next time I come by.”

And so we began our life in Sakuragaoka.

Weeks went by before we met the upstairs tenant. Occasionally I heard the squeal of bicycle brakes behind the house and then the sound of the backdoor opening. But I never saw Watanabe until Mr. Miyahara stopped by one evening and called him down from the second floor.

He was in his late twenties with a round, splotchy face. His hair hung thickly over his forehead and looked unwashed. It occurred to me that I had never noticed him use the bath. Occasionally the toilet would flush in the middle of the night, followed by footsteps heading up the stairs. But I never heard running water.

Watanabe bowed awkwardly, turned on his heels, and headed back up the stairs.

I guess Dennis was right. The house was big enough for all of us. Still, I was uneasy. When Dennis wasn’t there, I felt somehow exposed sitting at the table in the open dining room or standing in the kitchen. I never knew when the backdoor might fly open and Watanabe would burst in.

I would try to focus on my dissertation research—reading through volume after volume of Uno Chiyo’s collected works—but even as I chased down kanji in the dictionary or scribbled notes, I kept my ear trained for the screech of the bicycle and the sound of Watanabe’s key in the lock. When I heard it, I would drop whatever I was doing and rush into the altar room, sliding the door fast. Thank god for the first Mrs. Miyahara. Somehow, in the ten-mat Japanese room with her altar, I felt relatively secure. I could close the doors, as flimsy as they were, and enjoy a sense of privacy.

Striking a pose in the ten-mat room, next to the shelf with the first Mrs. Miyahara’s butsudan altar.

My nerves made it difficult for me to follow a regular routine. I couldn’t take a bath when Dennis wasn’t home. I used to enjoy long hot soaks, but now I could barely manage to settle into the tub before I started eyeing the frosted glass on the bi-fold door, looking for a dark shape on the other side. What if he came home? What if he tried to come in? Not that he would do so intentionally. It would be an accident. Still, the prospect made my stomach knot.

I could barely use the toilet when I knew he was in the house. And the only way I knew he was home was if his bicycle was parked out back. His bicycle. Even the sight of it made me nervous. It was bright pink with a ridiculously tiny basket on the handlebars. Too small for a grown man, his knees jammed into his arms when he pedaled, making him teeter precariously. It must have belonged to a girl once. His sister perhaps?

One afternoon, while I was at the library in Komaba diligently reading yet another article on Uno Chiyo, it started to snow. The return trip to Sakuragaoka took time and the walk from the station was long, so I packed up my books and headed home earlier than usual, delighting in the falling snow.

There were close to three inches on the ground by the time I reached my neighborhood. When I neared my house, I looked—as was my custom—for Watanabe’s bicycle. It wasn’t there. I was surprised, however, to see a set of footprints in the freshly fallen snow leading around the back of the house to the kitchen door. When I opened the gate on the other side of the house and walked across the garden to the front door, I saw footprints there as well, ending at the sliding doors of the living room.

Dennis must have returned early, too, I told myself. He now had a job at the Nichibei Kaiwa Translation and Interpreting School in Yotsuya.

I called to him when I entered, but he did not answer. That’s when I saw a small hole in the sliding glass door by the living room, just near the handle. Something was wrong. The snowy footprints flashed through my mind. Was someone in the house?

I called 119, the emergency number, and reported my fears. An omawari-san pulled up to the front gate on his bicycle about thirty minutes later. He greeted me politely when I slid opened the front door, slipped out of his shoes, and stepped up into the hallway as I explained my fears.

He examined the broken glass.

“The door is still locked,” he assured me. “Does anyone else live with you?”

I told him about Watanabe but suggested that he was not home, since his bicycle was missing.

The omawari-san was not convinced by my powers of deduction. Perhaps he had a flat tire or had not wanted to ride in the snow, he reasoned. He called Watanabe’s name several times, to no answer. And then he set off towards the stairs to investigate himself.

For some reason, I followed. I don’t know if it was that I was afraid to be left alone downstairs, or if I was just curious. I had lived in the house for six months now and had never gone upstairs. I had explored the other rooms, the ones we were not to inhabit, and had found each filled floor to ceiling with junk. Not recognizable things like books and suitcases but odd things like machine parts, tools, old faucets and light fixtures, dirty clothes, and cardboard boxes stuffed with plastic wrappers, used tin foil, and broken dishes. Mr. Miyahara owned a number of restaurants and apartment buildings. I guess he hoarded whatever he thought he might need for some kind of repair.

The omawari-san turned his flashlight on when he headed up the stairs. I tucked in close behind him. We stepped into a hallway at the top of the stairs. He waved his light up one side and then down the other. I could just make out two doors, each closed. The omawari-san turned to the door on the left and struggled with it briefly before sliding it open. I stood close behind him as he shone his light around. The rain shutters were closed and the room was dark and dank. He stepped inside. Peering around behind him, I saw that the space was cluttered with lumpish objects, piles of things, boxes. The omawari-san poked around each one, his light picking up a rumpled futon mattress, the top quilt wadded into a ball. The longer we stood there, the more oppressive and foul the odor became.

He stepped back into the hall and slid opened the second door. His light bounced over a wall of furniture, upturned chairs atop tables, a chest-of-drawers turned sideways, a bookcase covered in an old shower curtain.

“No one’s up here,” he said as he closed the door. “Are you sure someone lives up here?”

I nodded, somewhat bewildered. Could I be wrong?

“Whoever tried to get in is gone.”

The omawari-san was certain no one had entered the house. But he did tell me about the gang of “Pachinko-Ball Burglars” who’d been breaking into houses in the neighborhood. They used a pachinko ball and a slingshot to break a hole in a glass window or door just large enough to slip a screw driver through and jimmy the locks. Their precision with the balls was so fine, they rarely shattered the glass. Often the residents didn’t even notice the break-in for hours, even days.

They may have tried to get in, the omawari-san told me, but they had failed.

I wasn’t so sure.

As soon as the omawari-san left I fished a flashlight out from one of the kitchen drawers and climbed the stairs again. I shouldn’t be doing this, I told myself, my heart beating painfully against my chest with each step I took. But I had to see Watanabe’s room. I had to be sure.

Like the omawari-san I could barely slide the door open the floor was so littered with stuff. The smell that assailed me now without the omawari-san to serve as barricade was sickening: fetid body odor, rancid food, and hair tonic. I stepped inside and reached my hand above my head in the dark, flailing around until I touched the string of the overhead light. The illumination was immediate. A face rose up before me, and I jumped back so quickly I nearly tripped over a lumpish object until I realized the face was my own, pinched and pale. The light reflecting off the glass windows, shut tight behind the shuttered rain doors, created a mirror effect.

The lumpish objects turned out to be plastic garbage bags. Some were tied closed, others listed to the side spilling their contents onto the tatami which was spongy underfoot: empty styrofoam instant cup-o-noodle containers, used tissues, plastic spoons, disposable razors, cigarette butts, broken chopsticks, what looked like men’s underwear grey with use. There was the filthy futon, wedged between the garbage bags, random dirty dishes, and stacks and stacks of magazines, some piled up and bound with nylon string, others flung haphazardly over the floor. I inched a bit closer into the room and caught sight of a few pages: glossy photos of nude women posed provocatively, manga portraying gang rapes, men twisting women into painful positions, leering at them, laughing. A felt a tickling on my foot and looked down to see an enormous cockroach making its way to my pants leg.

I flew down the stairs and ran into the ten-mat Japanese room, slamming closed the doors and sidling close to the wall with the Buddhist altar, willing the first Mrs. Miyahara to protect me, willing Dennis to return. I listened for the sound of an opening door.

I told Dennis about my discovery when he got home, and he crept up the stairs to see for himself.

“He’s a pig alright! But I don’t think he’s dangerous.”

“Not dangerous?”

“Oh come on! Has he so much as looked at you since we’ve been here?”

That was true. Watanabe kept to himself. I let Dennis convince me to leave well enough alone. Still, I made Dennis promise not to leave me alone in the house any more than he had to. And he had to a lot, since he worked nights.

Seated in the living room with Dennis, 1984, Sakuragaoka, Tokyo.

It didn’t matter. A week later, Watanabe carried two garbage bags down the stairs and moved out. I don’t know why. He certainly gave us no reason for his departure. I wondered, though, if somehow he knew his lair had been infiltrated.

Dennis and I remained in Tokyo for a year after my Fulbright ended. Mr. Miyahara planned to raze the house so that he could build a multi-family apartment there. But he didn’t just turn us out to fend for ourselves. He found us a two-room apartment in a building he owned north of the Kitazawa train station.

The rent was higher, the space much smaller, and the rooms shook whenever the Odakyū express roared passed. But I slept more soundly there than I had slept anywhere.

The post My Tokyo House of Horrors appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

December 7, 2022

Nuns Fret Not: My Life in Manhattan

I often feel I could live anywhere. When I was seven my family spent a year in India, and I loved it. For college I relocated to the Sandhills of North Carolina. Only a two-hour drive from my home in Raleigh, still the landscape was different, with long-leaf pines, brackish ponds, and sandspurs. I loved it. And then in graduate school I spent five years in New York City, a world away from pines and ponds and everything I understood.

I loved it.

Although by then I’d spent time in Varanasi, India and Tokyo, Japan—buffeted by crowds and unfamiliar languages—New York struck me as more foreign by far. I was in the United States, so I shouldn’t have felt like an outsider, and yet I did. And I didn’t mind.

On days when I needed a break from my studies, I enjoyed strolling the sidewalks, gazing into the shop windows, vicariously sampling as I passed flavors and fragrances from around the world. I liked to tell my friends back home that New York was the cheapest place I’d ever lived. I didn’t have to pay a thing for entertainment! I just walked the streets and absorbed the sights and smells for free.

Occasionally I walked into St. John the Divine on Amsterdam and tiptoed along the massive granite columns, smooth and cool to the touch. The light streaming through the stained glass windows painted my skin, my hair, my book bag mauve and turquoise.

Occasionally I walked into St. John the Divine on Amsterdam and tiptoed along the massive granite columns, smooth and cool to the touch. The light streaming through the stained glass windows painted my skin, my hair, my book bag mauve and turquoise.

When I wanted to splurge I’d buy a knish or falafel from one of the sidewalk carts and carry it down to Riverside Park for a quick picnic before walking as far as the George Washington Bridge.

I remembered driving over that bridge on my journey up to New York from North Carolina ahead of the fall semester. Watching Manhattan sweep past the girders, I could feel my pulse quicken. The city’s energy was palpable. I was excited and terrified all at once.

I had almost no money.

The North Carolina College Fund had given me a loan but it barely covered my tuition. The bulk of the money I’d raised over the summer working three jobs—one for the state, one for a bar, and one for a pizza delivery—paid for dormitory fees. I stayed in Johnson Hall on Amsterdam and 116th Street.

My room was tiny, smaller even than the closet in my childhood home, the one where I relocated the planet Mars. When I first stepped into the space, I was crestfallen, uncertain I could survive in such cramped quarters. But it did not take long for me to adjust. The room had a window, a closet, a sink, and just enough space for a desk, single bed, and bookshelf. I spread an Indian-print fabric over the bed, hung a Japanese ukiyo-e calendar on the wall, and I was home.

There was a cafeteria on the first floor, but I only went there once. I felt so awkward trying to figure out the system—what to select, where to pay, and with whom to eat. I saw the woman who lived across the hall from me standing on line and tried to strike up conversation with her. She was from Cuba and very stylish. She just stared at me when I spoke, her immaculately painted lips curling into a sneer as she eyed my handmade cotton skirt. I heard her giggle with the woman next to her when I carried my tray to another table. Late at night she and that woman would sit in the hallway speaking animatedly in Spanish and cackling. Once, when I had an exam the following morning and was desperate to sleep, I cracked the door open and politely asked them to take their conversation to the lounge. It only made them louder.

I ended up eating most of my meals in my room. I guess you could call them meals. We were not allowed to have a hot plate or toaster oven, but an electric kettle was okay. I had a five-cup Regal Poly Hot-Pot and used it to warm coffee in the morning and soup at night. I lived on Campbell’s tomato soup. It had been my comfort food as a child.

I made foraging runs to the small supermarket a few blocks from my dorm when my stock ran low and loaded up on instant coffee, crackers, and as many cans of soup I could carry. I made do with powdered milk (for the soup and the coffee) until the weather turned cool and I could chill a small container of milk on the sill outside my window. I stored yoghurt there as well, and cream cheese. I had recently discovered the paradise of bagels. My nightly meal consisted of tomato soup, crackers, and a piece of fruit. Occasionally, I mixed things up with vegetable soup.

I made foraging runs to the small supermarket a few blocks from my dorm when my stock ran low and loaded up on instant coffee, crackers, and as many cans of soup I could carry. I made do with powdered milk (for the soup and the coffee) until the weather turned cool and I could chill a small container of milk on the sill outside my window. I stored yoghurt there as well, and cream cheese. I had recently discovered the paradise of bagels. My nightly meal consisted of tomato soup, crackers, and a piece of fruit. Occasionally, I mixed things up with vegetable soup.

My room faced Morningside Park, where we were told to never venture. It was too dangerous. From the corner of my window I could just glimpse the Columbia University faculty club with its white table clothes and dark-suited waiters. I wondered what they were eating. I could imagine the click of fork tines on the plates, the murmured conversations, and the soft chords of a piano playing somewhere in the background.

Midway through my first year, I discovered that elderly women (faculty wives, no doubt) served tea and cookies in Philosophy Hall, next to Kent Hall where I had all my classes. There was no charge. This fare became my lunch.

When I celebrated something, a successful exam perhaps, I would stop by the local deli and get a pastrami on rye with an extra pickle to go. I’d rush back to my room, curl up on my bed (where I ate all my meals—facing the window) and slowly savor the unfamiliar flavors. One sandwich was enough for two meals.

Now and then Wordsworth’s sonnet, “Nuns Fret Not at Their Convent’s Narrow Room,” would spring to mind, and I’d smile in agreement. My room was hardly the “pensive citadel” his students enjoy, but I was happy in it. I could come and go as I pleased, and with the exception of a few “mean girls,” I lived life undisturbed—scrimping mostly, splurging occasionally, studying always. My days were routine, but nearly every day was different. Some were difficult, many were bright. And at the end of each, I had my own narrow room as refuge, my familiar Indian-print bedspread and ukiyo-e calendar welcoming back.

My life in Johnson Hall unfolded long before personal computers became ubiquitous to college life. I had no television, no stereo, just my books, my portable Smith Corona electric typewriter, my soup, and my window. And from that narrow space, I had the world at my feet. An hour’s walk along Broadway would take me to Little Italy for a cannoli and a cup of cappuccino. Thirty minutes more and I was in Chinatown. If I traveled back on the IRT line, I’d slip into conversations between Haitians, Puerto Ricans, or Nigerians. I traveled the world for the cost of a subway token.

I left the dormitory when I married. The apartment in the Bronx where I lived with my husband looked out over Van Cortland Park and was spacious by comparison.

Even so, I still fondly recall my nest on the seventh floor of Johnson Hall every time I enjoy a bowl of tomato soup.

The post Nuns Fret Not: My Life in Manhattan appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

November 23, 2022

Not a Drive-By: On Falling in Love with a House

Why do you love your house?” the young woman asks me.

We are sitting on my front porch while she interviews me about the flood. She is doing a study on the River Des Peres that runs alongside the street perpendicular to mine, meandering through a concrete culvert before sliding into an underground tunnel not to emerge until it reaches Forest Park, several miles away.

Decades of chronic mismanagement of this river along with failures in the Metropolitan Sewer District led to the catastrophic floods in my St. Louis, Missouri neighborhood last July.

I pause for a minute to consider her question.

I didn’t really love the house when I first bought it in 1992.

“Not a drive-by!”

That is what was written on the for-sale sign when I pulled up to the curb with my realtor, April Schwartz. I didn’t know what that meant until she explained. The house isn’t much to look at from the outside. It’s better on the inside.

She was right. It wasn’t particularly pretty. An old cedar tree leaned toward the house, dropping brown needles and casting a dark shadow over the porch which was already dark with screens. The color of the brick was uneven but mostly a ruddy red and the trim around the windows and roofline was a deep Kelly green. The green trim and red brick reminded me of the houses of my childhood. Old fashioned.

There wasn’t a lot of inventory at the time in St. Louis, and I wanted to buy a house. It was important to me. I was proving something. After a ten-year marriage and a painful separation, I was establishing my independence.

The airiness that greeted me when we walked through the front door defied the heaviness of the façade. The living room swept into the dining room with an open flow uncommon in houses built before the “open-concept” rage. And this house was built in 1923.

Photo Post Card of my house from 1948. Author’s photograph.

As with other houses of that era, it was adorned with stained glass and honey-gold wooden floors. The fireplace was surrounded by leaded-glass bookcases.

The house embraced me with a sense of calm, a sweet belonging. And so it became mine.

I did not imagine I would live here long. This was a “starter home,” after all. But here I am thirty years later.

Why do I love this house?

“It fits me,” I answer.

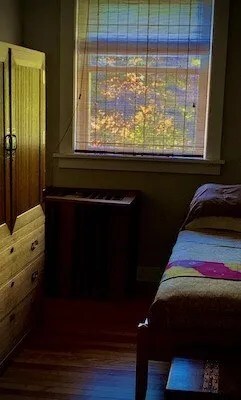

Autumn Light. Author’s photograph

I love the way the house changes with the seasons.

I know summer has left from the way the deck boards feel chill under my bare feet when I step out on the back porch with my morning coffee.

I love the way the reflection of the autumn leaves turn the walls of my rooms gold and russet making me feel I am floating in a bath of amber.

When winter comes my radiators hiss with warmth. Ribbons of light thread through the naked branches of the maple trees outside and across my desk, chasing dust motes.

At the first sign of spring I step eagerly out into the back garden, my coffee cup warming my hands against the chill drops of dew. “Have they come yet?” I ask. “Have they come?” I gently brush back the leafy loam in the flower beds, searching for the tentative crocus buds. Soon the garden will blossom with daffodils, forsythia, magnolia, and red buds. With the azaleas the hostas began to push their leaves up through the soil, curled tight at first until they unfurl in green and blue fronds, wide enough to shelter the bunnies that will inevitably eat them.

Spring. Author’s photograph.

By the time the hydrangeas bloom, summer is not far behind. At night the whir of the insects serenade my sleep and the morning birds call me back from dreams. Once the heat sets in, I close the windows and drift in silence, always searching for the cool side of the bed.

My house fits me.

I did not expect to love this house, but I do.

Living Room in 2020 with Durham Dog. Author’s photograph.

I often think of the early-thirteenth-century priest-poet Kamo no Chōmei who sought to simplify his life. In his poetic memoir Hōjōki (The account of my ten-foot-square hut, 1212), he describes the way he tries to divest himself of goods and property, moving further away from the splendor of the court until he ends up in a rustic hut. It’s tiny, hardly room for anything of any consequence. And yet, he has a shelf for his books, a corner for his lute, a place for all that he needs. In the summer he enjoys the cuckoo, in fall the cicada. In the winter the snow brightens his view, and in the spring, he and the little boy who lives in the hut at the bottom of the hill head into the woods to collect flowers and parsley and other edibles. As the years go by, Kamo no Chōmei comes to understand that though he sought to leave the trappings of the capital behind and live a life of austerity, he still finds himself attached to the beauty of this world.

His hut fits him.

My house is still “not a drive by.” The bricks are discolored, the landscaping is lopsided, and the front door is scuffed. But inside, where I spend most of my time after all, this house contains all of my happiness. I have found my ten-foot-hut.

2017 house. Author’s photograph.

The post Not a Drive-By: On Falling in Love with a House appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.