Rebecca Copeland's Blog, page 6

December 6, 2023

On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 2

“Remember, you need to bring a friend,” Fujie-san said as we prepared to end our phone call. “A Japanese friend.”

Ms. Fujie Atsuko was Uno Chiyo’s business secretary, literary agent, and tenacious gatekeeper. She set the conditions for our meeting in no uncertain terms.

“Neither Uno Sensei nor I speak a word of English. If you don’t bring a Japanese friend we’ll be uncomfortable.”

The implication, of course, was that I would be unable to conduct the interview in Japanese, even though we were speaking Japanese on the call.

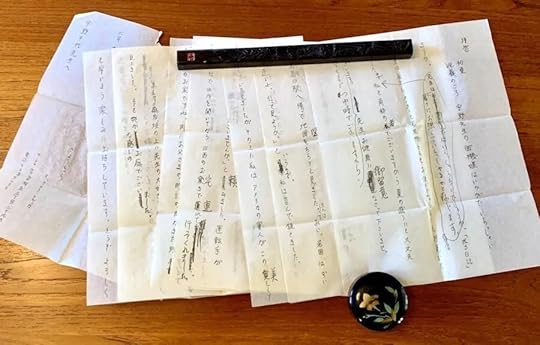

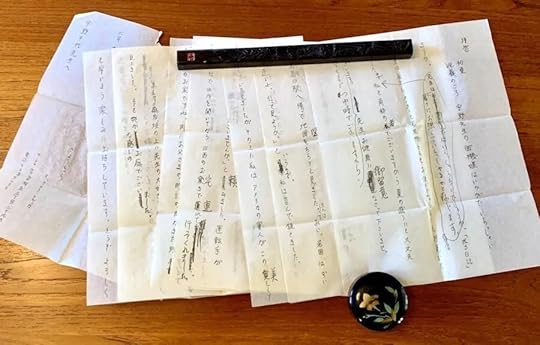

Besides, hadn’t I just sent Uno Sensei a long letter written meticulously in Japanese? Given the clumsy handwriting—sometimes blocky letters, sometimes flowing—there could have been no doubt that I had written it myself.

Didn’t that qualify me to interview the author by myself? The request stung.

Still, she had a point. My spoken Japanese was shaky. I had worked tirelessly on that letter with my Japanese language tutor. Without her efforts the letter may well have been incomprehensible!

“Of course. I will bring a friend, and I will be at your apartment by 1:00.” My hands were so sweaty with nerves that I could hardly hold the telephone receiver. Even so, I was shivering as I clutched the phone, bowing madly in the empty hallway saying goodbye.

Who on earth could I bring to the interview?

Naoko-san.

I had known Naoko since my year in Fukuoka. We had left the city together in 1977—I to return to my undergraduate studies at St. Andrews and she to enter a post-college program at Campbell College—both in North Carolina. She traveled with me to ease her parents’ worry about her making the trip alone. Other than that, we really had little in common.

And yet, we were friends.

“Sure,” she answered right away.

“I don’t know what to say, though.”

Naoko didn’t have much interest in literature and even less in my research.

“You don’t have to say anything,” I snapped, still secretly aggrieved at being “chaperoned.”

“I’ll do all the talking, Naoko. You’re just there to make Uno Sensei feel better.”

I spent the next week preparing the questions I would ask. I had them vetted by my Japanese tutor, and then I carefully transcribed them on a note pad. Again, and again, and again, until the pad on the middle finger of my right hand was red and puffy from the pressure of the pen and the words were scored in my brain.

I rushed out to purchase a small tape recorder and a set of cassette tapes. They still had those back in the 1980s.

“What on earth am I going to wear?”

I rifled through my wardrobe, such as it was. Mostly I wore jeans and sweaters to the library, along with sensible shoes to get me the mile or so up the hill from the station.

Too dowdy, too casual, too awful!

Besides, it was nearly the end of June—crazy weather time. Humid and chilly all at once.

Fashionable Uno Chiyo, 1935

I had nothing. Nothing I could wear to interview Japan’s first modern girl. Nothing that would draw the approval of the former publisher and editor of the magazine STYLE. A fashion plate if there ever was one.

It was hopeless.

I had very little extra money, but I headed to Shinjuku to search for an appropriate outfit. It would not be easy. I was taller than most women. My arms were longer, my waist lower. And my pocketbook was much smaller.

First, I went to Odakyu, the huge store right at the station. No luck. Everything was too tailored and too small. Same at the posh Isetan, a grand old store where the stylishly uniformed sales clerks eyed me cautiously.

But finally at Takashimaya I happened upon a sale on the top floor. A matronly sales clerk caught whiff of my desperation and latched on to me, guiding me to a rack of “free-size” dresses.

“Look at this fabric,” she purred. “It’s such a light weave, perfect for the season.”

She was right about that. The beige and grey plaid fabric was crisp and flimsy at the same time.

She pushed me into a dressing room.

It fit.

Of course it fit. The dress had no shape.

She cinched a belt around my waist, rolled the sleeves up high on my arms and curled the collar under.

“Oh, this is purrrfect on you,” she trilled, guiding me to a mirror.

I saw myself through her eyes.

“You’re so sumaato,” she said, meaning svelte. “I wish I were as tall as you! Then, I could wear a dress like this.”

That should have been a clue, but I was caught up in her enthusiasm. I purchased the dress and the belt and rushed home.

The next day I met Naoko at the station. She was dressed in a very chic two-piece skirt and blouse with colors and patterns that mimicked my own. We certainly looked well coordinated.

Rebecca and Naoko, June 21, 1984

Naoko had purchased a boxed cake and carried it neatly wrapped in a proper shopping bag. I had already scouted out the route to Uno Chiyo’s apartment—at least three times in advance—and knew there was a florist just down the street. It had been my plan to greet the writer with a lavish bouquet.

“What’s the occasion?” The florist inquired.

“I’m going to meet Uno Chiyo Sensei,” I practically shouted. “What kind of flowers do you recommend?”

“In that case,” the florist barely batted an eye—I think she may have been used to preparing flowers for the celebrated writer—“I’ll make a special arrangement.”

Her hands flew over the pails of fresh flowers selecting purple dendrobium orchids, white hydrangeas, and yellow lilies. The final product was breathtaking—bold and delicate all at once—and sweetly fragrant.

As we stood outside Uno Chiyo’s apartment building, I felt my stomach knot. For the first time, I was relieved that Naoko was with me.

Fujie-san called through the intercom when we rang the bell, and Naoko answered immediately, appropriately, politely, as I stared at Uno’s nameplate dumbstruck.

This was it. This was the moment I had fought so hard for over the last seven months.

What if I make a fool out of myself?

After all that preparation, what if she doesn’t like me?

What if I say the wrong thing?

What if . . . ?

To find out what happens next, please keep your eye on this space for the next installment of “On Encountering Icon, Uno Chiyo.”

The post On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 2 appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

On Encountering Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 2

“Remember, you need to bring a friend,” Fujie-san said as we prepared to end our phone call. “A Japanese friend.”

Ms. Fujie Atsuko was Uno Chiyo’s business secretary, literary agent, and tenacious gatekeeper. She set the conditions for our meeting in no uncertain terms.

“Neither Uno Sensei nor I speak a word of English. If you don’t bring a Japanese friend we’ll be uncomfortable.”

The implication, of course, was that I would be unable to conduct the interview in Japanese, even though we were speaking Japanese on the call.

Besides, hadn’t I just sent Uno Sensei a long letter written meticulously in Japanese? Given the clumsy handwriting—sometimes blocky letters, sometimes flowing—there could have been no doubt that I had written it myself.

Didn’t that qualify me to interview the author by myself? The request stung.

Still, she had a point. My spoken Japanese was shaky. I had worked tirelessly on that letter with my Japanese language tutor. Without her efforts the letter may well have been incomprehensible!

“Of course. I will bring a friend, and I will be at your apartment by 1:00.” My hands were so sweaty with nerves that I could hardly hold the telephone receiver. Even so, I was shivering as I clutched the phone, bowing madly in the empty hallway saying goodbye.

Who on earth could I bring to the interview?

Naoko-san.

I had known Naoko since my year in Fukuoka. We had left the city together in 1977—I to return to my undergraduate studies at St. Andrews and she to enter a post-college program at Campbell College—both in North Carolina. She traveled with me to ease her parents’ worry/anxiety about her making the trip alone. Other than that, we really had little in common.

And yet, we were friends.

“Sure,” she answered right away.

“I don’t know what to say, though.”

Naoko didn’t have much interest in literature and even less in my research.

“You don’t have to say anything,” I snapped, still secretly aggrieved at being “chaperoned.”

“I’ll do all the talking, Naoko. You’re just there to make Uno Sensei feel better.”

I spent the next week preparing the questions I would ask. I had them vetted by my Japanese tutor, and then I carefully transcribed them on a note pad. Again, and again, and again, until the pad on the middle finger of my right hand was red and puffy from the pressure of the pen and the words were scored in my brain.

I rushed out to purchase a small tape recorder and a set of cassette tapes. They still had those back in the 1980s.

“What on earth am I going to wear?”

I rifled through my wardrobe, such as it was. Mostly I wore jeans and sweaters to the library, along with sensible shoes to get me the mile or so up the hill from the station.

Too dowdy, too casual, too awful!

Besides, it was nearly the end of June—crazy weather time. Humid and chilly all at once.

Fashionable Uno Chiyo, 1935

I had nothing. Nothing I could wear to interview Japan’s first modern girl. Nothing that would draw the approval of the former publisher and editor of the magazine STYLE. A fashion plate if there ever was one.

It was hopeless.

I had very little extra money, but I headed to Shinjuku to search for an appropriate outfit. It would not be easy. I was taller than most women. My arms were longer, my waist lower. And my pocketbook was much smaller.

First, I went to Odakyu, the huge store right at the station. No luck. Everything was too tailored and too small. Same at the posh Isetan, a grand old store where the stylishly uniformed sales clerks eyed me cautiously.

But finally at Takashimaya I happened upon a sale on the top floor. A matronly sales clerk caught whiff of my desperation and latched on to me, guiding me to a rack of “free-size” dresses.

“Look at this fabric,” she purred. “It’s such a light weave, perfect for the season.”

She was right about that. The beige and grey plaid fabric was crisp and flimsy at the same time.

She pushed me into a dressing room.

It fit.

Of course it fit. The dress had no shape.

She cinched a belt around my waist, rolled the sleeves up high on my arms and curled the collar under.

“Oh, this is purrrfect on you,” she trilled, guiding me to a mirror.

I saw myself through her eyes.

“You’re so sumaato,” she said, meaning svelte. “I wish I were as tall as you! Then, I could wear a dress like this.”

That should have been a clue, but I was caught up in her enthusiasm. I purchased the dress and the belt and rushed home.

The next day I met Naoko at the station. She was dressed in a very chic two-piece skirt and blouse with colors and patterns that mimicked my own. We certainly looked well coordinated.

Rebecca and Naoko, June 21, 1984

Naoko had purchased a boxed cake and carried it neatly wrapped in a proper shopping bag. I had already scouted out the route to Uno Chiyo’s apartment—at least three times in advance—and knew there was a florist just down the street. It had been my plan to greet the writer with a lavish bouquet.

“What’s the occasion?” The florist inquired.

“I’m going to meet Uno Chiyo Sensei,” I practically shouted. “What kind of flowers do you recommend?”

“In that case,” the florist barely batted an eye—I think she may have been used to preparing flowers for the celebrated writer—“I’ll make a special arrangement.”

Her hands flew over the pails of fresh flowers selecting purple dendrobium orchids, white hydrangeas, and yellow lilies. The final product was breathtaking—bold and delicate all at once—and sweetly fragrant.

As we stood outside Uno Chiyo’s apartment building, I felt my stomach knot. For the first time, I was relieved that Naoko was with me.

Fujie-san called through the intercom when we rank the bell, and Naoko answered immediately, appropriately, politely, as I stared at Uno’s nameplate dumbstruck.

This was it. This was the moment I had fought so hard for over the last seven months.

What if I make a fool out of myself?

After all that preparation, what if she doesn’t like me?

What if I say the wrong thing?

What if . . . ?

To find out what happens next, please keep your eye on this space for the next installment of “On Encountering Icon, Uno Chiyo.”

The post On Encountering Icon, Uno Chiyo, Part 2 appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

November 22, 2023

On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo

“You shouldn’t work on a living writer,” some advised me as I struggled to find the subject for my dissertation.

A living writer, they argued, was still producing works, their oeuvre yet in progress. I guess they reasoned that whatever great discoveries I might make would be constantly threatened by falling out of date. What if the writer suddenly changed styles or wrote something incredibly uncharacteristic later in life?

It was 1983, and I was set on Uno Chiyo (1897-1996). A stylish writer, a unique voice, a modern adventurer—her life and work captivated me. I had come to know of Uno in a graduate class on the shi-shōsetsu in Japanese literature—a class focused on writers who wrote about themselves. Most of the texts we read featured protagonists who were riddled with angst, deeply ashamed of past behavior, and wallowing in self-pity. In contrast, Uno’s stories celebrated the missteps she had made. As her narrator looked back on past events, she seemed to say: “Oops. My bad.” And then she was off on her next adventure.

I wasn’t used to that kind of élan. I wanted to read more.

I wrote on Uno Chiyo for my MA thesis, I was counting on her to carry me through the PhD, too.

The best part about working on a living writer was the possibility of interviewing them. Something impossible with dead writers, unless you believe in the power of the séance! I couldn’t wait to meet Uno Chiyo, and I began to think of all the questions I would ask.

Luckily, I received a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship to travel to Japan for dissertation research in 1983. First on my dream agenda was interviewing Uno Chiyo. It never occurred to me that she might not be as thrilled to meet her number one fan-girl.

I caught a break when the esteemed literary critic, Saeki Shōichi, agreed to be my mentor. As soon as my husband and I settled in Tokyo, I asked Saeki Sensei to help me arrange a meeting with Uno Chiyo. He was happy to oblige. The author of several important monographs on biography, autobiography, and life writing, Saeki Sensei was the expert on life writing. He’d even made Uno the subject of a few of his studies, and he had met her on several occasions.

We were both startled, therefore, when Uno declined his request. She would not agree to meet with me.

Undeterred, I asked my Columbia University professor, Donald Keene, to intercede on my behalf. He had translated her award-winning novel Ohan (1957), one of her few works not based on her own life (though she claimed it was based on a story she heard from the owner of a secondhand shop in the city of Tokushima where she was in 1942 interviewing the puppet maker Tenguya Kyūkichi.)

A few weeks later, Professor Keene was sad to report that he, too, had failed to convince Uno Chiyo to meet with me.

I was beginning to lose hope when Professor Keene told me he was meeting the publisher of the Mainichi Newspaper, where Uno was then serializing her autobiography Ikite yuku Watashi (I Go On Living). He promised to intercede with him on my behalf.

“Finally!” I thought to myself, I will be able to interview my idol. By now Uno Chiyo was so much more to me than a subject of study. Having read many of her self-referential works, I had come to adore her spirit and spunkiness, not to mention her chic style. She sashayed through life doing what it was she wanted to do without a care for what others might think. That took courage!

“No.” Donald Keene told me. “Uno told the publisher she had no interest in meeting a scholar of Japanese literature.”

“What?” I couldn’t believe this. Was I so awful? All I wanted was to ask her a few questions.

Maybe Uno Chiyo wasn’t the hero I had made her out to be.

It was just at that time that my husband’s parents visited us from the United States. They had never been to Japan and we made an effort to take them everywhere! All the famous tourist spots. Nikko, Hakone, Nara, Kyoto, and Hiroshima. While in Hiroshima, I recall standing in the train station studying the train map. I was trying to find the line that would get us to the scenic island of Miyajima. That’s when I saw that one of the trains went to “Iwakuni,” a place name very familiar to me by now.

Uno Chiyo was born in Iwakuni. I’d never been.

I mentioned this coincidence to my husband and he told me I should make a day trip there.

Just by myself.

In all honesty, after over a week traveling with his parents, I needed my “alone time.” And they were ready to be freed from their demanding tour guide. So, off I went.

It did not take long at all to get to Iwakuni from Hiroshima. Only about 45 minutes on the JR Sanyō Line. Once there I decided to take a taxi to Uno’s birthplace.

The taxi driver and I soon began a friendly conversation. He was surprised a foreigner would request such a destination. Uno’s house was not on the regular tour route. In fact, most foreigners in Iwakuni were there for the US Marine base.

When I explained my interests, he was only too happy to take me to her birthplace. All along the way, he shared his impressions of her and recommended a few other places I might find interesting.

Uno had restored her family house in the 1970s. No one lived there now. I longed to see inside, but it wasn’t opened to tourists. I walked up and down the street, enjoying the plain wooden façade of the house and trying unsuccessfully to peer over the tall wooden fence surrounding the garden.

I recalled the way Uno had described the house during her childhood as one that was dark and threatening. She never knew when her father would fly into a rage over some petty mistake. As the oldest child, she was expected to attend him. She describes in her many memoirs waiting on the cold wooden floor outside the main sitting room, a room she named “the Clock Room” after the prominent timepiece on the wall.

“Chiyo!” he would call out, and I would answer immediately, “Yes,” just like a retainer before his lord. I always answered, “Yes!” Even when asked to do something I didn’t want to do, I jumped up, “Yes!” This was my way of overcoming the unpleasantness! (From my interview with the author in her Tokyo residence, June 21, 1984).

It was a gorgeous day and curiosity about Uno drew me to explore further. I walked to the elegantly arched Kintaikyō Bridge, spanning the Nishiki River. From there I wandered along the streets of Blacksmith Alley, where Uno wrote of her father’s dalliances in teahouses, spending money the family did not have.

When I returned to Tokyo, I was so excited by all that I had seen, I decided to write Uno Chiyo a letter describing my travel to her hometown. I noted that when I saw her birthplace, I imagined what it must have been like for her as a young girl waiting on her tyrannical father in the inner room, the room she called “the clock room,” serving him sake.

When I mentioned the Kintaikyō Bridge, I wrote that I could picture her character Ohan crossing it on her way to meet her erstwhile husband. And so on and so on until I had filled ten pages with stories describing—not just Uno’s hometown—but my love of her literature.

This time, I did not ask to meet her.

I had my letter reviewed by my Japanese language teacher. She corrected my grammar and diction. I wrote out a clean copy. More accurately, I wrote out five or six copies—each time making a silly mistake and needing to start over.

Draft letter to Uno Chiyo

When I was satisfied with what I had written—and how I had written it—I mailed the letter to Uno.

Within days, I received a postcard from her secretary, Fujie Atsuko, telling me that Uno Chiyo would see me.

Fujie-san followed up a day later by phone and made arrangements for me to meet the famed writer at her Minami Aoyama apartment.

What would I wear? What omiyage should I bring? What questions could I ask her?

Check back here for the next installment, and I will describe my meeting with Uno Chiyo!

The post On Meeting the Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

On Meeting Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo

“You shouldn’t work on a living writer,” some advised me as I struggled to find the subject for my dissertation.

A living writer, they argued, was still producing works, their oeuvre yet in progress. I guess they reasoned that whatever great discoveries I might make would be constantly threatened by falling out of date. What if the writer suddenly changed styles or wrote something incredibly uncharacteristic later in life?

It was 1983, and I was set on Uno Chiyo (1897-1996). A stylish writer, a unique voice, a modern adventurer—her life and work captivated me. I had come to know of Uno in a graduate class on the shi-shōsetsu in Japanese literature—a class focused on writers who wrote about themselves. Most of the texts we read featured protagonists who were riddled with angst, deeply ashamed of past behavior, and wallowing in self-pity. In contrast, Uno’s stories celebrated the missteps she had made. As her narrator looked back on past events, she seemed to say: “Oops. My bad.” And then she was off on her next adventure.

I wasn’t used to that kind of élan. I wanted to read more.

I wrote on Uno Chiyo for my MA thesis, I was counting on her to carry me through the PhD, too.

The best part about working on a living writer was the possibility of interviewing them. Something impossible with dead writers, unless you believe in the power of the séance! I couldn’t wait to meet Uno Chiyo, and I began to think of all the questions I would ask.

Luckily, I received a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship to travel to Japan for dissertation research in 1983. First on my dream agenda was interviewing Uno Chiyo. It never occurred to me that she might not be as thrilled to meet her number one fan-girl.

I caught a break when the esteemed literary critic, Saeki Shōichi, agreed to be my mentor. As soon as my husband and I settled in Tokyo, I asked him to help me arrange a meeting with Uno Chiyo. He was happy to oblige. The author of several important monographs on biography, autobiography, and life writing, Saeki Sensei was the expert on life writing. He’d even made Uno the subject of a few of his studies, and he had met her on several occasions.

We were both startled, therefore, when Uno declined his request. She would not agree to meet with me.

Undeterred, I asked my Columbia University professor, Donald Keene, to intercede on my behalf. He had translated her award-winning novel Ohan (1957), one of her few works not based on her own life (though she claimed it was based on a story she heard from the owner of a secondhand shop in her hometown of Iwakuni.)

A few weeks later, Professor Keene was sad to report that he, too, had failed to convince Uno Chiyo to meet with me.

I was beginning to lose hope when Professor Keene told me he was going to be meeting the publisher of the Mainichi Newspaper, where Uno was then serializing her autobiography Ikite yuku Watashi (I Go On Living). He promised to intercede with him on my behalf.

“Finally!” I thought to myself, I will be able to interview my idol. By now Uno Chiyo was so much more to me than a subject of study. Having read many of her self-referential works, I had come to adore her spirit and spunkiness, not to mention her chic style. She sashayed through life doing what it was she wanted to do without a care for what others might think. That took courage!

“No.” Donald Keene told me. “Uno told the publisher she had no interest in meeting a scholar of Japanese literature.”

“What?” I couldn’t believe this. Was I so awful? All I wanted was to ask her a few questions.

Maybe Uno Chiyo wasn’t the hero I had made her out to be.

It was just at that time that my husband’s parents visited us from the United States. They had never been to Japan and we made an effort to take them everywhere! All the famous tourist spots. Nikko, Hakone, Nara, Kyoto, and Hiroshima. While in Hiroshima, I recall standing in the train station studying the train map. I was trying to find the line that would get us to the scenic island of Miyajima. That’s when I saw that one of the trains went to “Iwakuni,” a place name very familiar to me by now.

Uno Chiyo was born in Iwakuni. I’d never been.

I mentioned this coincidence to my husband and he told me I should make a day trip there.

Just by myself.

In all honesty, after over a week traveling with his parents, I needed my “alone time.” And they were ready to be freed from their demanding tour guide. So, off I went.

It did not take long at all to get to Iwakuni from Hiroshima. Only about 45 minutes. Once there I decided to take a taxi to Uno’s birthplace.

The taxi driver and I soon began a friendly conversation. He was surprised a foreigner would request such a destination. Uno’s house was not on the regular tour route. In fact, most foreigners in Iwakuni were there for the Marine base.

When I explained my interests, he was only too happy to take me to her birthplace. All along the way, he shared his impressions of her and recommended a few other places I might find interesting.

Uno had restored her family house in the 1970s. No one lived there now. I longed to see inside, but it wasn’t opened to tourists. I walked up and down the street, enjoying the plain wooden façade of the house and trying unsuccessfully to peer over the tall wooden fence surrounding the garden.

I recalled the way Uno had described the house during her childhood as one that was dark and threatening. She never knew when her father would fly into a rage over some petty mistake. As the oldest child, she was expected to attend him. She describes in her many memoirs waiting on the cold wooden floor outside the main sitting room, a room she named “the Clock Room” after the prominent timepiece on the wall.

“Chiyo!” he would call out, and I would answer immediately, “Yes,” just like a retainer before his lord. I always answered, “Yes!” Even when asked to do something I didn’t want to do, I jumped up, “Yes!” This was my way of overcoming the unpleasantness! (From my interview with the author in her Tokyo residence, June 21, 1984).

It was a gorgeous day and curiosity about Uno drew me to explore further. I walked to the elegantly arched Kintaikyō Bridge, spanning the Nishiki River. From there I wandered along the streets of Blacksmith Alley, where Uno wrote of her father’s dalliances in teahouses, spending money the family did not have.

When I returned to Tokyo, I was so excited by all that I had seen, I decided to write Uno Chiyo a letter describing my travel to her hometown. I noted that when I saw her birthplace, I imagined what it must have been like for her as a young girl waiting on her tyrannical father in the inner room, the room she called “the clock room,” serving him sake.

When I mentioned the Kintaikyō Bridge, I wrote that I could picture her character Ohan crossing it on her way to meet her erstwhile husband. And so on and so on until I had filled ten pages with stories describing—not just Uno’s hometown—but my love of her literature.

This time, I did not ask to meet her.

I had my letter reviewed by my Japanese language teacher. She corrected my grammar and diction. I wrote out a clean copy. More accurately, I wrote out five or six copies—each time making a silly mistake and needing to start over.

Letter to Uno Chiyo

When I was satisfied with what I had written—and how I had written it—I mailed the letter to Uno.

Within days, I received a postcard from her secretary, Fujie Atsuko, telling me that Uno Chiyo would see me.

Fujie-san followed up a day later by phone and made arrangements for me to meet the famed writer at her Minami Aoyama apartment.

What would I wear? What omiyage should I bring? What questions could I ask her?

Check back here for the next installment, and I will describe my meeting with Uno Chiyo!

The post On Meeting Literary Icon, Uno Chiyo appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

November 8, 2023

A Flash of Lightning: On Reading David Joiner’s “The Heron Catchers”

Herons are lithe, elegant birds. Gliding over water, nesting in fields, or soaring through the air, the heron’s perceived ability to transcend the elements has led to fabulous fairytales, stately dances, and sublime paintings. Haiku poet Matsuo Bashō wrote verses about the heron and artist Ohara Koson immortalized the bird in woodblock prints. Now novelist David Joiner adds to our collection of heron lore and love with his hauntingly beautiful The Heron Catchers, to be published soon by Stone Bridge Press.

Set within the quiet green abundance of the Yamanaka Onsen village, some distance from the picturesque castle city of Kanazawa, The Heron Catchers promises a lovely idyll of rural life. As charming as rural life may appear from a distance, however, it too is rife with conflict and pain. Shortly after the novel opens, readers are confronted with treachery. Here, main character Sedge visits the famous Kenrokuen garden, at the heart of Kanazawa, to meet a woman:

He stood on a short wooden bridge over a stream winding away from Kasumagaike pond, admiring a newly blossoming cherry tree, and pines here and there recently freed from their protective winter yukitsuri ropes, when a snapping of branches made him spin around. To his astonishment, a wild boar burst from a bush, colliding with a heron upstream and sending a cloud of feathers in the air (10).

Sedge springs into action, covering the injured heron’s head with his jacket to both calm the bird as he attempts to rescue it while simultaneously protecting himself from its razor-sharp beak.

Treachery comes in other forms, too. Soon we learn that Sedge has been deeply wounded by his wife’s infidelity. Nozomi, has run off with the talented but volatile potter, Kōichi,—taking with her all of Sedge’s savings—and leaving Sedge the impossible task of running their Kanazawa craft store with no capital. Nozomi’s brother, mostly in an effort to protect the family name, invites Sedge to spend time at the inn he owns not far away in Yamanaka Onsen. Sedge can teach the employees English for room and board. It turns out that one of the inn’s employees, Mariko, is married to Kōichi, the man who ran off with Sedge’s wife.

When the rules at the inn become too oppressive—particularly those that prevent Sedge from seeing Mariko romantically—Sedge decides to strike out on his own. Or rather, he moves in with Mariko. The comfort their strange alliance offers is threatened by the presence of Kōichi’s teenage son, Riku, who lives with Mariko. He, more so than the adults, has been hurt by life’s cruelties. Like the injured heron, he is frightened and dangerous, lashing out at any who try to approach him.

The Heron Catchers

Will Sedge and Mariko be able to find the solace they need to heal their own damaged hearts? Will they be able to rescue Riku? What has happened to Nozomi, Kōichi, and the money? These and other questions propel the narrative forward. But more than the trace of a plot, readers are captivated by the understated beauty of the prose and its shimmery profundity. There are truths buried here, truths about the fragile persistence of sorrow and love and hope. We brush up against them as we read but hardly notice.

When they reached the shrine, Mariko waved him to a narrower path he hadn’t noticed, which wound behind the shrine and through a copse of sugi trees. In a minute they emerged on the opposite side of the mountain, lower than where they’d been. Here the view opened even more. Despite the highway near the ocean, where cars were small as ants, he sensed that no one in the world could find them here (95).

We follow the characters as they travel deeper in their journey towards healing, a journey that takes them deeper into the mysteries and beauty of nature. There are missteps along the way. We watch as the characters stumble, uncertain in their pain. And, we celebrate with them, too, when they learn to staunch their hurts as surely as they bind a heron’s broken wing.

Given my background in Japanese literature, I could not help but think of the folk-tale of the heron wife while reading the pairing of Mariko and Sedge.

In the Japanese folk-tale, a young man comes across a wounded heron, and he takes it in and nurses it back to health. When the heron has regained the use of its wings, he releases it, and the heron flies away.

Time passes and the young man meets a beautiful woman with whom he falls in love. They marry and live happily together. The young wife weaves cloth, which the man sells, and the two are able to support themselves.

But the wife places a constraint upon the man: He must never observe her while she is weaving. Of course, the young man cannot resist the temptation to look, and when he does he sees a heron at the loom.

Now that her secret has been exposed, the heron wife can no longer remain in the human world. She returns to her flock, leaving the man bereft.

In The Heron Catchers as well there is an importance placed on seeing, control, and the power of knowing. In one scene, Sedge’s desire to see Mariko’s naked body in the moonlight reads with mythic overtones.

She led him into her bedroom. Of the three curtained windows along her walls, only the one behind her futon had been left open for the sky to pour its light inside. It was enough to see her figure when she slid her yukata off, light and darkness moving over her body: her nipples, her navel, the space beneath her armpits, the barely visible bars of shadow between her ribs, the constellation of scars—the sea of skin that surrounded these things like water keeping islands afloat (172).

Unexpectedly, this romantic scene leads to tragic results that threaten to unravel the domestic happiness the two have struggled to achieve. This scene, and the one cited above, suggest the tug at work in the novel to get to the heart of some hidden meaning—to understand, to know, to read “the constellation of scars.” Much of the novel, therefore, carries readers into the characters’ inner worlds where time swirls round and round unanswered questions.

In an online interview between publisher Peter Goodman and author David Joiner, Goodman observes that David’s American characters do not walk through his narratives like the questioning outsider. The story does not draw attention to their otherness or make it the point of conflict but rather integrates them within their landscapes in a very natural way. The comment is astute. Readers know that Sedge is American, but we are never told what he looks like, what race, what religion, or any other identifiers. Rather, we identify with Sedge in a much more universal way, as a human being on a quest. “I want my characters to be on equal footing linguistically and even in some respects culturally,” Joiner noted to Goodman in response, “that allows me to go a lot deeper in their interactions with each other.”

And, deeper we go.

Part of the cultural landscape that Joiner’s characters explore is shared with haiku poet Matsuo Bashō, who traveled through Yamanaka Onsen and Kanazawa on his celebrated journey into “the deep north.” For all his barbs and hard edges, the boy Riku is drawn to Bashō and his poetry. When Sedge asks him why Bashō made the trip, Riku replies that he did it to “escape the pain and sorrow of this world” (169). For Riku, haiku is an escape. For The Heron Catchers, Bashō’s journey offers the characters a model for the momentary epiphanies life offers. In the space between these sudden realizations, Sedge, Mariko, and even Riku take their own journeys deep into the interior where they are able to bind their wounds, meditate, and return.

Matsuo Bashō wrote a few poems on the heron. This one seems most appropriate to this novel:

inazuma ya

yami no kata yuku

goi no koe

a flash of lightning

into the gloom

goes the heron’s cry

Translated by Geoffrey Anthony Thwaite

David Joiner author photo

Author David Joiner was born and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio, but now makes his home in Kanazawa. The Heron Catchers is his third novel and will be available from Stone Bridge Press and other online outlets from November 21, 2023.

Joiner’s second novel Kanazawa, also published by Stone Bridge Press (2022), was named as a Foreword Reviews Indie Finalist for multicultural novels.

The post A Flash of Lightning: On Reading David Joiner’s “The Heron Catchers” appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

October 25, 2023

Yukio and the Flying Plum Tree

It happens every time I introduce students to the ill-fated 9th-century exile, Sugawara no Michizane. In the midst of describing the wrongs he incurred, his heart-broken ox, and the flying plum tree, I nearly burst out laughing. It’s not that I relish Michizane’s misery. Rather, I can’t help but be reminded of my own!

Mind you, I did not suffer on my journey to Dazaifu, the way Michizane did on his. In fact, the trip was rather charming, if you can get past my silly self-consciousness.

I have photographic proof, too.

There I am, posing in front of the shrine with Yukio Noguchi.

He, a head shorter than I, slouches comfortably, the wrinkle in his t-shirt makes it seem the silk-screened ship across the front is sailing.

I stand stiffly, one foot edging in front of the other in proper model pose.

We do not smile.

I had been told it was inappropriate to smile for Japanese photos. But truly, I did not feel like smiling. I did not feel much of anything except awkward.

I’d been in Fukuoka for less than a month.

I met Yukio Noguchi, the man in the photograph, Sunday when I attended church services with my parents.

“What are you doing tomorrow?” he asked in a voice barely above a whisper.

I didn’t know. I looked to my mother for help and saw her brighten.

“I would like to take you to Dazaifu,” he said.

I stared at him blankly. Dazaifu meant nothing to me.

“Have you been?” he seemed surprised by my lack of response.

“No,” I mumbled.

“That’ll be fun,” my mother responded quickly, poking me in the ribs as if to say, “be nice.”

“Dazaifu is an ancient government center,” Yukio continued. He talked so softly I had to lean down to hear him.

“There’s a shrine there. It’s famous.”

And so it was decided that I would meet him the next morning, and he would guide me to this place that was once an ancient center and had a shrine. I admit I was curious. And even though being with Yukio taxed my auditory powers, I was happy to get out of the house and see more of this country that had become my new home.

My parents had dragged me across the world to join them in Fukuoka. I was to enter an international program at Seinan Gakuin where my father worked. It was still a few weeks before the start of the program. The other American students weren’t in town yet. I was bored.

I didn’t know much about Yukio Noguchi. He was a theology student at the university and seemed very serious. When he spoke, he sounded as if he were delivering a life or death pronouncement. If, that is, you could hear him.

The boys I had grown up with in North Carolina were the opposite. They were loud and flirtatious and had only one thing on their mind. It wasn’t life or death.

I didn’t know why Yukio wanted to take me to Dazaifu.

Was it a date?

Did he want to practice English? Was he trying to impress my father, who was the new chancellor of Seinan?

I couldn’t find any of the cues I was used to.

I didn’t even know what to wear.

The women I met when my parents took me to other people’s houses for dinner, the women at the church, the women I saw on the bus, all dressed more carefully than women in North Carolina. For one thing, they always wore stockings.

And so, even though it was a warm August morning, I complied. I pulled on a pair of panty hose, selected a belted “India-print” dress, the most modest dress I had, and borrowed a pair of my mother’s shoes. They were low-heeled and easy to slip on and off. I’d learned enough after my month in Japan to know, I’d likely need to take off my shoes at some point.

The train Yukio and I took to Dazaifu had booth seating. He sat across from me. The seating was so narrow that my knees grazed his from time to time. The sense of intimacy made me uncomfortable.

I don’t remember what we talked about. I just recall that the volume of his speech was so low I had to lean forward each time he spoke and strain the catch his words. It didn’t help that he held his hand over his mouth practically the whole time.

Once in Dazaifu, the approach to the shrine was lined with shops selling trinkets and cakes and ices. I wanted to sample everything. I wanted to poke through the stores. But Yukio was on a mission, and so we forged ahead.

I was acutely aware of the way people stared at us. Or, at me. I felt like a gargantuan there in my mother’s shoes walking next to soft-spoken Yukio.

“Dazaifu is famous for plum trees.”

Yukio told me some bizarre story about a plum tree flying from Kyoto to Dazaifu out of love for the unfairly accused Michizane. As if that made any sense.

It was August. None of the trees was in bloom. None was flying, either. They were just trees.

It was hot.

We stepped into a museum, which was at least cool, and then spent an eternity looking at things I didn’t understand: ancient armor, ancient scrolls, ancient everything. At some point we found a diorama with tiny dolls enacting Michizane’s journey. As I loomed over the tiny figures, I couldn’t help but imagine myself a giant interloper hovering over an unfamiliar world.

On our way back to the station, we crossed through the shrine grounds again and a photographer grabbed hold of us. He had a Polaroid camera and for a modest price, he would memorialize our visit for all time.

“God, no!” I thought.

But Yukio ponied up the money.

I still have the Polaroid.

I almost lost it in the flood of July 26, 2022.

I managed to fish my old photo albums out of the fetid waters. Some photos disintegrated even so, but this one remained, reminding me of an August day in 1976 spent with a kind man who just wanted to share something of his home with a girl who was too awkward to think of anything but herself.

It is ironic, perhaps, that I now teach Japanese literature and occasionally tell students about the ill-fated Sugawara no Michizane. Over the years, I have visited Dazaifu any number of times. Each time I carry the image of that Polaroid in my mind’s eye. I remember Yukio Noguchi, the train ride, the diorama, and the whispered stories of flying plum trees.

The post Yukio and the Flying Plum Tree appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

October 11, 2023

Watching Sumo with my Father

“Watch, he’s going to salt his hams!” my father called out to me. He had the sumo match on the TV in our Fukuoka living room.

It was November 1976. We’d been in the house on Torikai for several months now. Occasionally we’d watch reruns of “Bonanza” together. It was one of the only shows they broadcast in English. That and “Sesame Street.” Unable to understand Japanese, I’d even taken to watching “Sesame Street” in the evenings when I got home from studying at the university. It was a distraction from the frustration of trying to communicate in a language I couldn’t understand. Besides, I’d begun to like Grover, Cookie Monster, and the other characters on the show.

I couldn’t fathom what my father saw in sumo! Just a bunch of nearly-naked fat men shoving each other.

“There he goes!”

The sumo wrestler tossed a handful of salt into the round earthen ring and slapped his backside hard before clapping and squatting at the center line.

“I call that salting the hams.”

My father referred to the way the wrestler smacked his “hams” with salty hands.

“Okay, I get it.” I went back to reading a back issue of Time magazine.

“Here comes Jesse!”

I looked up again to see a tall man step into the round ring with a bright orange sash. His face was framed by fuzzy sideburns, and he looked singularly unstable on legs as long as telephone poles.

“He’s American,” my father explained.

“American?”

“From Hawaii. He won the tournament in 1972—the first foreigner ever to do so.”

Jesse “salted his hams” and squared off against his opponent in the center of the ring. Both of them stood there glaring at each other. Rather, the opponent glared up at Jesse’s chin. They turned and sauntered back to the edge of the ring to grab another handful of salt. The crowd began to react—clapping and shouting.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“It’s jikan,” my father explained. “Time for the bout.”

With an underhand flick of his wrist, Jesse tossed a smidgen of salt into the ring, almost as if he couldn’t be bothered. The other wrestler threw a huge handful that arced high over the head of the referee who stood on the edge of the ring in an elaborate silk outfit, quite the contrast to the wrestlers.

The wrestlers kneeled down and then with near lightning speed were at each other’s throats, smacking and shoving. Jesse pushed forward, seemingly invincible, and knocked the smaller man clear across the ring, forcing him to tumble down the raised platform.

“He won another one!”

I watched as Jesse stood at the top of the ring and extended his long arm in a friendly gesture, pulling his opponent back into the ring. They bowed. The loser left. Jesse squatted at the edge of the ring and waved his hand over the referee’s fan, snatching up a white envelope before he too left.

“He gets money because he won,” my father explained.

I watched the next bout and then the next, asking my father questions.

“Why do they throw salt?”

“To purify the ring.”

“Why do they do that little routine where they raise their arms out to the side like bird wings?”

“They clap to call the gods. They open their hands like that to show they have no weapons.”

I was hooked.

I rushed to the TV every afternoon to watch the bouts with my father.

I learned that Jesse’s sumo name, or shikona, was Takamiyama.

“It means High Mountain View,” my father translated. “Fitting don’t you think? He’s the tallest wrestler in the tournament.”

Takamiyama wasn’t the highest-ranked wrestler, though. That honor belonged to Wajima and Kitanoumi. I soon developed a dislike for Kitanoumi.

In the first place, he was just not very attractive with his massive girth and double chin. But more than that, it was the arrogance he exuded. I didn’t like the way he strutted around glaring at everyone. Takamiyama was big, too, but he radiated a lovable sweetness.

Wajima, Kitanoumi’s biggest competitor, was brawny but lacked the corpulence of the other wrestlers. He was tall and almost lanky. My father told me he had been a college champion. In fact, Wajima is the only sumo-tori even to this day to have reached the highest rank of yokozuna coming from a college background. He was also one of the few to wrestle under his own family name, Wajima, instead of a shikona.

I always rooted for Wajima.

My father and I had other favorites, too.

We liked Asashio. His face was round and his cheeks so big, it was sometimes hard to even see his eyes. His forehead was always furrowed. But in post tournament interviews he emanated a cheerfulness, comparable to that of his stablemate, Takamiyama.

I have to be honest, though, Takanohana was my favorite.

I didn’t like him because he was a strong wrestler—which he was—but because he was undeniably handsome.

He was almost slender with a muscular build. His face was chiseled and his prominent nose was aquiline. For the longest time I thought his shikona meant High Nose but only later learned the kanji were Noble Flower.

I lived in Fukuoka from 1976-1977 and had many wonderful experiences. But watching sumo with my father tops the list. Just before I had to return to the States, my parents took me to Nagoya where we caught the last day of the July tournament.

Wajima trounced Kitanoumi to win the Emperor’s Cup. I left Japan a few days later, still savoring the victory.

Wajima in Nagoya after winning the tournament, July 1977. Credit: Author’s badly flood-degraded photo

Watch this YouTube video to see Jesse in action.

The video begins with his last bout as a professional sumo-tori. Jesse had hoped to continue wrestling until he reached the age of forty. But, having sustained several injuries along the way, he was on the brink of being demoted to one of the lowest divisions of sumo, the makunoshita. He had to retire just short of his fortieth birthday.

In 1980 Jesse became a naturalized Japanese citizen (the only way he could continue in the sumo world following retirement from active wrestling.) In order to do so, he had to give up his American citizenship. I remember watching a documentary on TV with my father about it. The reporters interviewed Jesse’s mother who cried over his loss of US citizenship. My father grew a bit weepy, too.

The video opens with Jesse’s last bout and then charts his history in sumo.

At 3:54 you can see Jesse wrestle with Wajima.

He wrestles with Kitanoumi at 5:26.

And there are a few scenes of Jesse being silly and sweet from 13:57.

The post Watching Sumo with my Father appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

September 27, 2023

Dancing Dōjōji—Finding the Demon Within

“We practice at the Kokin-en. It’s close to the Funaoka Onsen,” my friend instructed.

Funaoka Onsen is well known in Northwest Kyoto. Many consider it the best public bath in the city. The name “onsen” means hot spring. But, as I understand it, the water isn’t naturally thermal. It’s heated. Even so, the building is iconic. I’d passed it any number of times out and about and lost in Kyoto!

I looked up the Kokin-en online and found photographs of it on a webpage but I could find neither a map nor a street address. Not wishing to bother my friend for further details, and knowing the general location, I struck out in search of the studio on the appointed day.

I walked along Senbon-dori Avenue and then turned down Kurama-guchi towards Funaoka Onsen. I walked around a few side streets where I thought the house was but failed to find it.

It was the middle of the rainy season, and the air was particularly humid—sweltering, but not raining.

Hot and growing discouraged with my search for the elusive Kokin-en, I retraced my steps to Senbon-dori Avenue and stopped by the local “police box” to ask for directions.

The policeman on duty pulled out a few maps and investigated. Even he wasn’t certain. But he said it had to be close to the bathhouse. Back I went to Funaoka Onsen and wandered along the streets fronting the iconic landmark. I tried to keep to the city’s grid pattern, believing that if I went systematically from street to street, I would eventually find the spot.

I was just on the point of giving up when I heard the strains of a nagauta shamisen drifting out over the humid streets.

I followed the sounds and there it was, the house, just as it appeared in the online photographs. Perhaps a bit smaller.

The Kokin-en; author’s photograph

I slid open the door, removed my shoes, and climbed the steep stairs to the second-floor practice space—following the twang of the shamisen. The tatami-matted room extended across the entirety of the second floor. Even so, with three dancers, two other observers, and a man with a camera on a tripod, the space was cramped.

I squeezed into a spot by the stairway and tried to quiet my breathing. My roundabout search for the house had left me sweaty and frazzled. I mopped my neck and forehead with my handkerchief and dug a folding fan out of my backpack. Gradually, the heat no longer felt as oppressive, and I begin to focus on the beauty of the dance.

Here is what I saw:

The dancers’ tabi-clad feet glide over the tatami-matted flooring with a swish, swish—as soothing as a tiny wind chime on a summer night. Swish, swish. The sound is cool, like bamboo leaves fluttering.

“Imagine Tamasaburō,” my friend tells the dancers referring to the exquisite onnagata noted for his performance of this dance.

“He takes his time with this turn, allowing his audience ample opportunity to see him, his languid form, his beauty.”

She demonstrates and in that moment I can see in her diminutive frame the tall and slender onnagata. She conjures him forward.

The two other dancers, her students, mimic her movements. They are contemporary dancers and have not studied classical Japanese dance, except for the lessons my friend has offered. Yet somehow, their hands know just how to move in delicate curves like a Buddhist mudra.

I don’t think I ever managed that quiet arch when I practiced Nihon buyō. My fingers were always too stiff, too consciously fixated on being soft. With these dancers, the thumb tucks into the hand like a sleeping puppy.

My friend, dancing alongside the students, demonstrates the steps. They watch her, imitate her. Now and again she slows the movements down to help them see the transitions from one step to another. When she does, when she tries to go slow, occasionally the steps elude her and her body forgets.

Muscle memory. She dances without thinking, following the rhythm of experience. Slowing down disrupts that memory as surely as a dream snapped in two when we awaken from sleep.

She has to stop and think about the movement, going through it in her mind’s eye and then coaxing her body to return to the dance—first in the natural tempo of the performance, and then slower so her students can follow her.

An oscillating fan stirs the hot air in the room and through the open window I can see a seven-story apartment building—a yellow square blocking the view that once was—stifling the breeze that can’t be.

The dancers lift their feet too high—ever eager—and my friend corrects them.

“No, here, like this,” she demonstrates, lifting the hem of her yukata ever so slightly so they can see the way her foot raises up just so the toe barely passes the top of her tabi socks above the round curve of her ankle bone.

Next, she shows them how to lift the sleeves of their garments. The sleeves of their practice yukatas are too short for doing this well. If they were in an actual performance they would wear a furisode kimono with long dangling sleeves.

“Like this,” she says. “Be careful not to cover your face.” The sleeves should serve as an elegant frame, showing the beauty of the face.

It’s late afternoon now and sun pours through the opened, unscreened windows catching the silver sound of the bells that the dancers shake. I can hear children playing in the street below. The dancers perform the heart of a young girl, a girl perhaps not much older than these children, a girl who nevertheless goes mad from desire.

Or is it anger, rather?

Isn’t she enraged by the way she was lied to and tricked by all the men she met—her father, the young monk, the priests?

The demonic spirit rises in the girl and with one swift glance, she fixes her gaze on the monk.

My friend demonstrates the swift direction of the glance. The dancer’s head should move first to the left, then slightly lower, and in a sharp, swift move, it juts to the right. There. There you are. There’s no escaping now.

The dancers watch my friend. And now they stand at the ready, preparing to move through the steps she has just taught them. As they wait for the music to start, they go through the steps in their minds, moving their hands and seeing the dance in the space before their eyes.

“That’s good,” my friend says. “We’ll stop here.” She pushes an app on her iPhone and the shamisen music ends.

The dancers kneel on the tatami, their dancing fans now folded and placed parallel to their knees. They smooth the wrinkles in their yukatas and bow in thanks to my friend for her lesson. My friend turns to the three of us observing and we bow as well.

I make my way down the narrow stairs, my steps a bit uncertain, my knees stiff from having sat so long on the tatami. At the door, I slip into my shoes again and step outside into the gathering dusk. It looks like rain.

The post Dancing Dōjōji—Finding the Demon Within appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

September 13, 2023

Dancing Dōjōji—Finding the Demon Within

I can’t tell you her name.

I promised to keep her Nihon buyō lessons confidential.

That sounds odd, I suppose.

It’s not as if she is stealing secrets or trying to profit off the hard work of others. The lessons she gives are free. And she offers them out of the goodness of her own heart. Even so, they challenge a long tradition of master-disciple inheritance.

Nihon buyō, the umbrella term used to describe a variety of traditional performances of Japanese dance, is governed by strict lines of hierarchy and licensure.

Practitioners study for years under the direction of a certain master and in the style of a certain school. If a dancer is talented and persistent, and if the master is receptive, the dancer can petition to receive a shihan or teaching license. Usually at that time the dancer will also receive a natori or professional stage name. The license and stage name denote that the dancer has learned the movements unique to the school and is therefore trusted to carry on the traditions through teaching. In Nihon buyō’s early years, the succession to the master’s name was usually tied to blood. Most who inherited the name were family members—by birth or by adoption. These days, the natori process can be colored by favoritism and politics.

Suffice it to say, who is and who isn’t allowed to teach is cumbersome and costly. The strict rules protect the purity of the movements. But when naming successors grows fraught, the endurance of the art is jeopardized.

My friend, my nameless friend, therefore skirts these lines by teaching without a license. In a way, what she is doing today is similar to what my first dance teacher, Ura Sensei, did over forty years ago, as I described in an earlier post.

Ura Sensei taught me and a few other foreigners informally. Since she did not have a license, technically, she could not teach. But her teacher gave her permission to share her art with us, because it was assumed we would never go very far. By teaching us, she was not dodging the licensure hierarchy.

My friend isn’t imperiling the licensure either. But since her “lessons” are a bit out-of-the-ordinary, I will withhold her name.

“Would you like to come watch one of my dance practices,” she asked after I returned to Kyoto.

“It’s part of a project I’ve been working on. I’m teaching contemporary dancers to perform classical Japanese pieces.”

My friend is a celebrated choreographer. She spent over twenty years in New York performing in the contemporary dance world. Since she was a Japanese national, people always asked about her Japanese roots, assuming that she would come automatically equipped with knowledge of traditional Japanese dance. My friend had initially trained in ballet before transitioning to contemporary.

She had never studied traditional Japanese dance. She felt her art lay in other performance styles.

Tired of the constant queries, however, she eventually returned to Japan to study Nihon buyō.

When we talked about her experiences in traditional dance, I was somewhat familiar with the practice methods since I had studied, though briefly, in the Hanayagi School and then later in the Nishikawa School. My friend’s training, however, is much more extensive and has focused on the dance of the larger, Kabuki stage.

One of the most difficult pieces she has studied, and the one that most influenced her later contemporary choreography, is Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji, “The Maiden of Dōjōji,” which I described in my earlier post.

The dance, one of the oldest Kabuki pieces to have originated in the even older Noh theater, is extremely long. From beginning to end, it lasts almost an hour, and on the Kabuki stage the dancer makes several spectacular costume changes, the kind that take place in the blink of an eye and in full view of the audience.

“The Maiden of Dōjōji” is really a tour de force for an onnagata, the male actor who performs the female roles on the Kabuki stage. The dance charts both the subtle and fierce movement of a young woman’s heart. The onnagata must channel the spirit of a young woman who has the strength of a demon.

“It is such a complicated dance,” my friend explained, “that it is rarely taught these days, and when it is, it costs a fortune in training fees.”

Traditional arts are costly to learn as well as time consuming, no matter the piece or the genre. It takes years of practice before a dance teacher will consider introducing a pupil to a dance as difficult as “The Maiden of Dōjōji.” And then once the teacher begins the training, it takes years to master the dance itself. Along the way, the pupil must cover the costs of lessons and special gifts. Should the teacher allow the pupil to perform publicly, the pupil must pay for recital fees and also the purchase of practice and stage costumes, fans, and other accessories.

“The Maiden of Dōjōji” takes a lot out of a dancer, both in terms of time and money. But to be able to perform the dance is a pinnacle of achievement.

Because my friend feels there is benefit in contemporary dancers crossing the aisle, as it were, to study traditional dance, she volunteers her time teaching them. She does this not so that they can perform on the traditional stage—which would be nearly impossible—but so that they can experience, somatically, the way the body adapts to a different mode of movement.

Learning new dance movements, teaching their bodies to conform to different styles will make them better dancers.

“We’ve been practicing this particular dance for about four years now,” my friend told me. “I’m interested in how these dancers—trained in other genres—experience and absorb the traditional movements. It’s really fascinating.”

In my next post, I will share the experience I had attending my friend’s practice session and watching her teach sections of this complex dance.

Please keep an eye on this blog for the next installment of “Dancing Dōjōji—Finding the Demon Within.”

The post Dancing Dōjōji—Finding the Demon Within appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

August 30, 2023

Dancing Dōjōji—Finding the Demon Within

I’m not a theater professional. But I love teaching about Japan’s classic theaters—Noh, Kabuki, and Bunraku. One tale among all others captures students’ imagination, “The Maiden of Dōjōji,” a story of monstrous transformation. It is performed in the Noh, Kabuki, and Bunraku theaters.

Over the summer I saw the character come alive in a dance practice in Japan, giving me fresh appreciation for the tale.

In this series of posts, I want to tell you about my unusual and up-close view of the dancing maiden demon. Let me start here by telling you about the tale itself and the androgynous figure of the shirabyōshi who dances it in Kabuki.

The Kabuki Dōjōji dance, “Kyōganoko Musume Dōjōji” (The Maiden of Dōjōji), is derived from an earlier Noh play. The Noh play has even more ancient roots, originating in a Buddhist miracle tale. Without going into lots of sources and details, here’s the gist of the central story:

A young maiden named Kiyohime falls in love with a handsome priest named Anchin. He rebuffs her, due to his celibacy vows, and slips away to the Dōjōji Temple. Naïve and goaded by her desire for Anchin, Kiyohime pursues him. When she reaches the Hidaka River, it is so swollen with recent rains, she cannot cross. Frustrated, angry, and embarrassed, her bitterness coalesces in her heart, turning her into an angry serpent. She crosses the river easily and heads after Anchin.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. Thirty-six Ghosts series

Meanwhile, the priests at Dōjōji Temple, in an effort to protect the young monk, hide him under a massive iron bell. But, as the vengeful snake, Kiyohime, coils around the bell in anger and strikes it again and again. Her tail pounds so forcefully that she gives rise to flames. Anchin is incinerated!

Dojoji engi emaki detail

In the Kabuki dance the Kiyohime-Anchin story hovers in the background but is not enacted directly on stage. Instead, the story element of the dance concerns a young shirabyōshi performer. She initiates the action of the play by traveling to the Dōjōji Temple where the priests are dedicating a new temple bell.

Shirabyōshi denotes a category of female performers who flourished during the medieval era. They were often invited to perform for emperors, daimyō, or high-level priests. Although these dancers were highly talented, they were itinerant (like most performers in the medieval era, Noh actors included) and therefore on the margins of respectability.

An interesting aspect of the shirabyōshi is her androgynous costuming. She wore a courtier’s formal cap, often carried a sword at her waist, and otherwise cross dressed as a man in her performances. To see a shirabyōshi perform on the Kabuki stage invites a wonderful entanglement of genders. The onnagata, the Kabuki actor who specializes in female roles, performs as a woman who is dressed as a man.

Painting of Shirabyoshi, Shizuka, by Katsushika Hokusai, c. 1825

In the dance-drama, “The Maiden of Dōjōji,” the shirabyōshi dancer asks the priests to allow her to perform for the dedication of the bell. Since no women are allowed on the premises during the dedication, they deny her request. She dances outside the temple gate in such a beguiling way, the priests cannot help but let her in.

Her lovely movements reveal her maiden spirit, but as she dances she becomes more and more agitated. The tempo of the dance grows intense until by the end, the “maiden” has climbed atop the bell, her hair in disarray and her kimono slipping back to reveal the triangular scales of a serpent. Now we realize she is Kiyohime, and she has returned to exact revenge.

In a final pose of defiance, the dancer casts her gaze from one shoulder to the other until with a final snap of the head, she rivets the monks below with a gaze as sharp as a bolt of lightning.

The scene is mesmerizing.

The performance then—and now—displays the power of the original shirabyōshi to express the inexpressible and to use her dance in protest for those consigned to the margins. The dance also highlights the talent and beauty of the Kabuki onnagata. It is a long, complex performance with a number of signature “quick changes” of costumes that take place in full view of the audience. Only dancers who have achieved a high-level of skill are able to complete the performance. See the links below for video clips from actual performances.

In my next post, I will described how a friend of mine, a dancer and a choreographer, invited me to see the way she introduced the Dōjōji dance to her colleagues. I made plans to visit her studio—a space she rented in an old house not far from my Kyoto airbnb.

Keep an eye my blog for the follow up story!

To see glimpses of the “Maiden of Dōjōji” performed on the Kabuki stage, check out these YouTube videos:

This recreation includes two dancers towards the end.

Note the first quick change at marker 1:13.

Note the glare from the bell at marker 4:30.

This clip shows an anime version followed by live action:

At marker 1:09 we move to a live performance of Kabuki

At. marker 2:38 you will see a “quick change.”

At 3:10 note “the glare.”

The post Dancing Dōjōji—Finding the Demon Within appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.