Rebecca Copeland's Blog, page 13

June 9, 2021

Black Bears and Inspiration

It was the second time I’d seen him since arriving at the cabin for my writer’s retreat. Earl lived at the bottom of the mountain in a small wooden structure that at one time might have been tidy but had long since begun to sprawl into clutter.

First there was the broken-down lawn mower he left alongside the dirt road, then the washing machine, and later his truck with the hood perpetually propped up. My father would shake his head when he drove by on his way up the steep windy road to the cabin. Still, he and my mother took pity on Earl. The death of his wife had started his slide into hoarding. When my parents learned Earl’s son in Texas was out of job, done with his marriage, and eager to return home, they sold Earl an acre of bottom land significantly below cost so his son could build there. They imagined the two men keeping one another company. Little did they know Earl Junior planned to put a trailer on the acre. That itself would have been fine, but he got the thing stuck on their secondary road in the process and never managed to move it. So, there it sat along with the lawn mower, washing machine, and busted truck. Eventually Junior defaulted on the loan he’d procured to buy the acre. Earl never told my parents. The next thing they knew, the bank owned the property that had once been theirs. At least the “repossession” resulted in the removal of the trailer.

The ordeal soured my parents’ feelings for Earl, but only slightly. They believed he kept watch over their place when they were away.

I knew he never climbed the road to their cabin. His knees were shot. He could barely make it down his driveway. So when he caught me at the bottom of the hill and asked about the bear, I suspected he was just trying to scare me.

“Oh yeah, there’s a big old black bear up there,” he said.

“Have you seen him?” I had my doubts.

“Seen him and seen what he done.” Earl stared right at me, trying to gauge my reaction.

“What’s he done?”

“Oh, he got into the trash cans down at the Yancy’s. Made such a racket I thought it was World War Three.”

“But, you’ve seen him?”

“Big black bear. Must weigh a ton if a day.”

I really had my doubts now.

“Good to know. I’ll keep an eye out for him and let you know when I see him.”

“Oh, you’ll let me know alright. You’ll be hollerin’ from here to that home of yours in Missouri.”

I could still hear Earl laughing as I headed back up the mountain with my groceries. At the same time, I tried to remember all the things my father told me about black bears, about how shy they are, about how I shouldn’t worry.

What must Earl think, I wondered, of a middle-aged woman from Missouri living in that cabin up there by herself. Would he understand that I was writing a novel? Did he understand that it was men like Earl who made me more uneasy than a phantom black bear?

As I returned to my Kyoto mystery, I found my attention being sidetracked by my next novel, set in the mountains of Eastern Tennessee. It would start with the shocking discovery of a man found murdered in his ramshackle house. A woman from Missouri would be the prime suspect, though in fact, she is innocent.

Top Photo by Jack Charles on Unsplash

Second image by Tiffany Bailey from New Orleans, USA, CC 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The post Black Bears and Inspiration appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

May 26, 2021

Messengers of Imagination

In Japan, many consider birds messengers of the gods. They fly between the world of the living and the heavens, carrying our prayers and dreams on their wings. The entrance to a Shinto shrine is marked by a large gate known as a torii, which literally translates “bird exists” and is more smoothly translated “bird perch.” The torii demarks the entrance to a sacred space, separating the profane from the pure. Torii are typically simple structures with two large upright pillars connected by one or two horizontal planks. They are made of rough wood, smooth wood, painted wood, and these days often concrete.

Kobayashi Eitaku, Izanagi and Izanami, c. 1885. From sv.wikipedia.org

Kobayashi Eitaku, Izanagi and Izanami, c. 1885. From sv.wikipedia.orgOther iconography, images, and architectural structures also focus on the vertical pillar or hashira extending from the foundations upon which we stand into the realm beyond our reach. In traditional (“vernacular”) Japanese houses, the central pillar is known as the Daikoku-bashira and believed to house the god Daikoku. One of the seven gods of good fortune, Daikoku is associated with the kitchen or hearth of a home. The Daikoku-bashira separates the public-facing part of the house from the private, inner regions. The pillar takes on more than a structural function and is believed to represent the heart of the family and the pride of the patriarch.

In the myths of Japanese origins there is a pillar that extends between the heavens and the lands that the god Izanagi creates when the brine from the tip of his spear coagulates and forms islands. He and the female deity, Izanagi, shimmy down this pillar to walk about the lands below. And they circle the pillar in courtship before they launch into their production of the natural world.

Pillars are also an important feature of the noh stage. Because noh was once performed outdoors on stages set up at Shinto shrines, modern day theaters recreate the look. Hovering over the noh stage, now completely contained in an elegant indoor space, is a thatched roof supported by three free-standing pillars. The pillars are structural but also serve as important markers in stage directions. The masked actor, for whom visibility is limited, depends on the pillars as critical measures of placement and space. Equally significant in demarking space.is the painting of the Yōgō Pine that invariably adorns the back of the stage. The pine, like the torii, suggests the conduit between the world of the spirits and the everyday world before the stage. In fact, a performance of noh is offered, not for the audience of mortals but for the gods.

Noh National Theatre, Tokyo

Noh National Theatre, TokyoIn an earlier post I described the way my memories of birds, and more particularly pigeons, brought me back to Kyoto. Not my favorites among birds, even so, those neighborhood pigeons opened the door that would lead me into the novel I was then writing, the novel that would become The Kimono Tattoo. I like thinking of birds as representing this passage to other worlds.

Sitting in the mountains of Eastern Tennessee, watching birds soaring overhead and butterflies flitting over my laundry, I was transported through time and space until I returned to Kyoto, to a place where I was able to visualize the entrance to my story. Not only did the birds, and the memories of earlier birds, carry me across borders, they also transported me into an imaginary realm where a translator I had yet to name began to emerge from the clouds of dream and past experiences and take charge of her story.

Featured photo (top) by Kouji Tsuru on Unsplash

The post Messengers of Imagination appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

May 15, 2021

Cover Reveal!!

You wrote the book. You found a publisher. (Finally!) And now the book is making its way to market, which means to bookshelves in book stores. To READERS! Others will read what you spent so many years writing.

Or will they?

What if they walk past the place on the shelf where your book awaits? What if they never pick it up, open the cover, and step inside the world you have created?

Whether you judge a book by its cover or not, the cover has to grab your attention. It has to provide clues to the story that awaits. It needs to suggest, to beguile, to pick up on implicit codes of recognition.

So much depends on the cover.

It was my pleasure to work with Melissa Carrigee of Brother Mockingbird Publishing, on the cover for my novel. With a title like The Kimono Tattoo there was potential for so many different kinds of images—some lascivious, some clichéd. To give into romantic fantasies of kimono-clad “geisha,” while tempting for its potential market appeal, would not have represented the book. (There must be a confederation of book designers who automatically fall back on this cliché when covering books in translation by Japanese women writers. I have stories to tell there! I will save that for later.)

Melissa held a cover contest! Many of you may have voted on the various social media sites.

So, now we can announce! We have a winner……

And here it is:

Let me know what you think! Comment below or email me.

The Kimono Tattoo will be released in June!!!

Photo by Stefan Steinbauer on Unsplash

The post Cover Reveal!! appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

May 5, 2021

Beginning at the Beginning

It starts with birds.

I wasn’t sure how to begin at first. I sat at the oilcloth-covered table in the cabin, gazing out over the porch, thinking back to Kyoto. I had already decided to set my novel in Kyoto. In order to write about Kyoto, I had to return there in my mind, picture myself there.

I remember sitting at my desk on the second floor of the house behind the Kyoto zoo translating the novel Grotesque by Kirino Natsuo. On moments when I needed to sound out a phrase or search my brain for a word I would stop, look out the window, and follow the flight of the pigeons. As I pondered their flight choices, I debated which word to use: bizarre? weird? strange? Before long I’d be lost in the different feats the pigeons performed, the different patterns, the rhythms. Two birds would fly up, three would land. Three birds would take off, one would land. How easily they caught hold of the electrical lines, never losing their grip, never even looking down. Bizarre? Weird? Strange? By the time I returned to my translation, the answer was clear. It was definitely “bizarre.”

A butterfly dancing over the laundry outside brought me back to the present. I had left an odd assortment of socks drying on the rail outside the sliding cabin door. I watched the butterfly flit delicately here and there and then I was back in Kyoto, back with Grotesque, back with the pigeons.

I would start there. My protagonist is a translator. I still don’t know her name. But I know what she is doing. She is sitting at her desk in a house behind the Kyoto zoo, surrounded by dictionaries, watching the pigeons, and yearning to step beyond her daily grind.

I was watching the pigeons when the doorbell rang. I hadn’t noticed before the way they appeared to divide into different squadrons. As soon as one squadron of five or so pigeons set down on the electrical wire outside my second-floor window, the second would take flight. I hate pigeons. But I enjoyed watching them soar up into the unbelievably blue April sky, wheel out over the Kyoto zoo, and temporarily block my view of the ritzy Miyako Hotel on the far side of Higashiyama. As they turned for home, their wings would wink iridescently. For pigeons, they were uncommonly beautiful. Once landed the earlier squadron would return to the skies. Pedestrians below, tourists mostly—marching noisily between Nanzenji Temple and the zoo—rarely thought to look up at the pigeons perched dangerously above their heads. I always had a chuckle when one noticed too late, dabbing desperately at a desecrated head and glaring upward at the delinquent bird. Usually the victims were raucous high school boys. The one singled out by the pigeon missile would be harangued by his unscathed buddies who would blot at his once perfect coif with hand towels and handkerchiefs. But a few weeks ago, when a pretty junior high school girl was globbed by a bird, I slipped down the stairs and offered her a damp towel. I am not sure what brought her more trauma: being shat upon by a pigeon or being set upon unexpectedly by a red-headed foreigner. “Thank you,” she managed to sputter in something resembling English, despite the fact that I had spoken to her from the start in Japanese. “Dou itashimashite,” I continued. “And please, keep the towel.” I closed the door.

That’s the way my novel started. I didn’t have a plot yet. I didn’t have a title. And my protagonist didn’t have a name. But I had a beginning. And that’s a good place to start.

Photo by Donna Douglas on Unsplash

The post Beginning at the Beginning appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

April 21, 2021

Ode to a De-Cluttered Mind

October 2, 2012: Second day of my writer’s retreat.

Somedays, even on a writer’s retreat, we cannot write. We have to de-clutter. And for me, returning to this cabin, as noted in my earlier post, carries with it considerable emotional freight.

“De-clutter” and “freight”—it would seem the cabin is crammed full of painful memories. But nothing is further from the truth. Being here—touching the wooden logs my father carried, standing before the faded mirror that once held my mother’s reflection—brings me great comfort. I want to savor their presence.

The cabin hasn’t been lived in for years. My parents used to come here with some regularity, spending long weekends in the tiny one-room cabin my father built. Daddy would spend the day on maintenance, patching the roof, fixing clogged pipes, cutting up the trees that had fallen into the road. Mother would clean, sweeping away mice nests and scrubbing down the linoleum floor. After lunch, she’d clear away the dishes and then walk along the ridge to her own special spot beneath a stand of hemlocks. It was lush with ferns, soft with fallen leaves, and she would sit there for a spell treasuring the quiet until dinner preparations called her to the cabin. She’d meet Daddy on the path back. He would shower while she fixed their supper. And after the dishes were done, they would play Yahtzee or Backgammon under the anemic glow of the lone electric bulb.

Yahtzee and National Geographic

Yahtzee and National GeographicThe Yahtzee box is still here on the shelf Daddy built to hold all the issues of National Geographic they had collected over the years. “One day we’ll have time to read them cover to cover,” my mother told me. But that day never came. They never found the stillness. They came from a stock of people that only ever knew work. Moments of quietude were rare, stolen beneath a stand of hemlocks.

My father began to suffer from atrial fibrillation, making it difficult to clamber over the hillsides with his chainsaw. And before any of us were even aware of it, he began to slip into the embrace of Alzheimer’s Disease. He stopped telling jokes and refrained from entering debates with my older sister over esoteric points of philosophy. We thought he was just losing his hearing. He gave up on Scrabble. He still worked the crosswords, but they took longer and longer. Before we were aware, he was gone. Still there, in his chair, but somewhere else. Somewhere even further away than his Tennessee cabin. He had gone home to the hills of West Virginia. And then, after five years of being shunted from one nursing home to another, he left for good.

I pull the curtain back in the alcove where he and Mother kept their “cabin clothes.” Two pairs of his shirts are hanging there alongside his coveralls and a pair of double-knit trousers, nubby from wear. His clothes are old but laundered and pressed. Daddy was meticulous about his appearance. And Mother obliged him, even ironing the clothes he would wear in the mountains. I touch the sleeve of his flannel shirt remembering the times I saw him in the familiar plaid. I bring the sleeve to my nose and breathe in lightly hoping to find some trace of his scent. Don’t our clothes carry a glimmer of our souls just as the kimonos do in all those old novels? My father liked to splash his face with Old English aftershave. But all I smell on his flannel sleeve is an unpleasant mustiness.

I think about giving the clothes in the cupboard away. My parents taught us never to waste. But looking closer I see they are stained with mice droppings.

I grab a black garbage bag from under the sink and stuff the clothes in, hanger and all. Mother’s as well as Daddy’s. His old cloth cap, discolored at the brim. Her straw bonnet, half chewed through by mice. Everything. And then in the utility room I collect the oil cans—long empty—scraps of tarpaper, random nuts and bolts. Anything and everything that has no place, that no longer belongs, I toss into black garbage bags.

I move into the kitchen and pull the half-used bottles of ketchup and sauce off the shelf. No telling how long they’d been there. Jars of seasoning salt now rock solid with moisture, broken tea cups. (“Well, you can still drink out of them,” I could hear my mother complain), a mismatched collection of plastic forks. And on and on. One bag, two bags. I left the macramé wall hanging I had knotted for Mother in middle school and the misshaped vase my sister had made. I left the book of birds, the terracotta candlestick holder that said “Texas!” and the oil-paper umbrella from Japan. When I had collected almost more than I could carry, I tied up the bags and carried, dragged them down the mountainside to my car. I would need to find the garbage center.

When I return to the cabin, now de-cluttered, will I be able to set my laptop up on the kitchen table? Will I find the space to write? Whereas the clutter will be gone, I know the shards and remnants of my past will find their way into the story I will tell.

The post Ode to a De-Cluttered Mind appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

April 7, 2021

Writing on the Lam

October 2, 2012

On leave from academic duties, I have traveled to the mountains of Eastern Tennessee to spend a month in the rustic log cabin my father built by hand in the 1970s. Here, in my “writer’s retreat” I have time to myself. I’m supposed to be working on an academic study of kimonos and women’s literature. My argument is that the imagery of kimono often found in modern Japanese literary works serves as a language of its own, defining characters and adding semantic layers.

But, I won’t be doing that here in this cabin. I am here to write a mystery novel, surreptitiously. Perhaps I’m overreacting, but I’ve decided to keep my activities a secret afraid that others will criticize me if they find out. It wouldn’t be “seemly” for a professor on leave to spend time writing fiction, would it? I’m not trained in fiction; I’m not paid to write fiction. My expertise lies elsewhere. I already feel out of my depth and inauthentic. Who do I think I am? Some great novelist? I have only told a few people of my plans. I write in secret.

I spend the day pushing ideas around, trying out plotlines, imagining characters. Because I’ve decided that the novel will hinge on the practice of translation and that my protagonist will be a translator, I store all my documents and scribbles in a folder on my computer that I’ve named “Translator.” I don’t even allow myself to call the folder what it is: “Mystery Novel” or “Debut Novel.” Am I that paranoid that someone will look over my shoulder, peer into my personal laptop and discover what I’m really up to?

Maybe.

Or, maybe I’m too afraid to admit to myself that I’m actually trying my hand at writing a novel. Will that jinx the process? Will that only make it worse when I fail? Perhaps the only person I’m hiding my real activities from is myself.

As I sit on the back porch watching the sun set, as I walk the ridgeline with my dog, Wilson, as I sweep the crumbs and cobwebs from the corner of the cabin, I think about my novel. I haven’t gotten far. But this is what I know.

My protagonist is an American woman who has a PhD in Japanese literature and should be rising in life but instead is flailing desperately. She has failed in her career, unable to secure tenure. She has failed at her marriage, unable to keep her husband from cheating. Forty years old with nothing to show for herself, she returns to Japan, where she spent her childhood. (Shall her parents be missionaries?) It is the only place she ever felt at home, even though she never really “fit” in.

She translates to support herself. But her job is hardly a career, most of the other translators she works with are freeters. They come and go as they please, signing on for a translating project when they need extra cash. Most are Japanese. She’s a fulltime employee. That does not mean she has the perks and privileges that come with fulltime employment in most Japanese firms—or used to. What it means is that her work is carefully measured and scrutinized. She must meet a certain quota of translations every month. She may not translate for any other company or even for another individual. All of her translating energy must be devoted to her firm.

And then, one day, a mysterious woman appears at her door, inviting her to translate the work of a famous novelist who has been missing for over twenty years. No one knows what happened to him. He just disappeared.

She wants to accept the invitation, but she knows that doing so will put her in jeopardy with her firm. If she takes on the task, she’ll be translating on the lam—much as I am writing on the lam!

So, shall we name our translator?

I have thought of Meg. Her parents (surely they are missionaries!) would have selected this name because it allowed them to call her Megumi, which in Japanese means a “blessing.” Her Japanese boyfriends, if she had any, could call her “Megami” which means “goddess.”

Rachel is another contender. The Japanese version might be Reiko. Rei for lovely.

Naomi would be interesting….

Photo by Icons8 Team on Unsplash

The post Writing on the Lam appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

April 5, 2021

Seeking Inspiration: How the Japanese Mountain Witch Encourages Artistic Creativity

Have you ever wondered how authors find the ideas for their books? Or, how they nurture those ideas to publication?

Join this live zoom-based interview to explore the way the Japanese mountain witch, or the yamamba, has encouraged artistic creativity across time and place.

Interviewed by Katie Stephens, scholar of Japanese horror literature and film, I will discuss the way a decades-long fascination with the yamamba, a day of therapeutic art creation, and an encounter on Facebook resulted in the forthcoming volume, Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch (co-edited with Linda C. Ehrlich, Stone Bridge Press, 2021).

Inspired and organized by Dr. Laura Miller and sponsored by the Ei’ichi Shibusawa-Seigo Arai Endowed Professorship in Japanese Studies and UMSL Global at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Zoom Register in advance for this meeting: https://umsystem.zoom.us/…/tJwlf–vpj8iHdYp3Y… registering you will receive email containing information about joining the meeting.

For more information click here.

Image Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images, Creative Commons

The post Seeking Inspiration: How the Japanese Mountain Witch Encourages Artistic Creativity appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

March 24, 2021

Cabin Dreams

October 4, 2012: The fourth day of my “writer retreat.”

I am staying in the log cabin my father built in the 1970s. My brother and I were in junior high when the building began. He’d bring us up with him on weekends to help him dream it. One spring, when the snow was still on the ground, he purchased almost fifty acres of timbered real estate. The mature white pine had been cut for lumber, and wide swaths of timber were felled in the process of getting the pine out. The land looked ragged. The trucks and timbering equipment had left gashes in the earth and scars on the remaining trees, too small to harvest. That’s why the property was cheap. That’s how my father could afford it.

I step out into the bright October morning with my rescue dog, Wilson, to walk along the ridge. We’ll hike a bit before I return to my writing project, my debut mystery novel.

My father bought the land almost as an act of survival. Being on the mountain brought him a sense of refreshment, an opportunity to return to roots and escape the political turmoil of academics. He had been a professor, too (like me), employed at a seminary that was then rocked by the existential crisis of fundamentalism. When I was fifteen, I didn’t understand what the purchase of the land meant to him. I just assumed he finally had some money to spend and wanted the property for his own entertainment. Now, feeling the soft pine needles underfoot, smelling the heavy dampness of the rhododendrons, I sense the stress lift from my shoulders as it must have his. My father’s retreat becomes my own.

I recall how he looked out over the slag pile where the saw mill had stood and dreamed himself a house. The site backed onto the ridge. He would have a spacious porch there where he and my mother would sit in retirement and watch the sun come and go. For the time being, though, he decided to fashion a temporary shelter, a log cabin. He would build it on his own; relying on memories of childhood, when log cabins were more than temporary whimsies. His arms and hands remembered the history of felling logs, stripping them of bark, and notching the ends. And that’s what he did.

Now, feeling the soft pine needles underfoot, smelling the heavy dampness of the rhododendrons, I sense the stress lift from my shoulders as it must have his. My father’s retreat becomes my own.

But log cabins don’t just spring up over night! Especially when you’re building on your own with the less-than-satisfactory help of two easily distracted teenage children. In the meantime, we lived in a tent. It wasn’t very big and felt all the smaller when the four of us were crammed in at night. We spent most of our evening time sitting around the fire pit my father built, roasting marshmallows, and listening to my father tell stories of his boyhood. Mountains were my father’s domain.

To allow some room to stretch, he built a crude lean-to alongside the ridge and set up a folding table for my mother. It was up to her to feed us. She had at her disposal a portable cooler and a cantankerous camp stove that blew itself out at the slightest breeze. While my father directed my brother and me through our paces, my mother labored at her makeshift kitchen alone, first cooking and then cleaning up. The kitchen was her domain. I don’t think at the time I recognized the unfairness of this distribution of labor. My father focused on his domain, my mother on hers. It never occurred to me that for my father, the labor was self-imposed and personally enjoyable, while my mother’s labor was service. I suppose I helped her now and again. I don’t remember. I was more enthusiastic about being my father’s go-fer, grabbing the tools he needed, helping to roll logs.

We used locust for the foundation posts. Black locust. “The locust is a dense wood,” my father explained as we walked one of the old lumber paths to the site where he’d seen the tree he wanted to cut. “It doesn’t easily rot and will last nearly forever.” The chainsaw whirred to life and he yelled at my brother and me to step back. In all honesty, the tree looked pretty spindly to me, not as thick and round as some of the white pines he’d pointed out earlier. Those, he explained, were too soft. We latched the trunk of the tree he felled with a chain that he then connected to the wench on his old International truck.

He bought the truck not long after buying the property. Whenever we returned home to Raleigh, he left the truck onsite and used it as soon as we arrived to rumble up and around the old logging roads, pulling trees, and hauling supplies. It was a work horse. He told me once the truck was so good on an incline it could climb a tree. In truth, it was his toy. And oddly enough, the previous owner had painted it a bright purple. We referred to it as the Purple People Eater.

After working a few days like that, we’d all head to Watauga Lake to swim and wash off the sweat and mosquito spray that had built up over the days and nights. Log by log the cabin emerged from the loamy soil just beneath the ridge. Each log notched by hand and tapped into place. The higher the walls the closer my connection grew to this place and to my father.

Foundations: The Scaffolding of Dreams

Foundations: The Scaffolding of DreamsMy father never built his retirement house. His last years were spent in a nursing home suffering the final stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Surrounded by tortured screams and the smell of piss, he was unable to walk and nearly deaf. But, his arms and hands remained strong, carrying the memories of those logs. Those memories linger here, too, in the cabin he built, a temporary structure that has stood for nearly forty years.

I sit here now, in this cabin that was only the start of a dream, dreaming my own dwelling. Mine will be a structure of words. It will be a story that arises from the rich soil of imagination and carries me across the sea to other houses and other dreams. Maybe like my father I will end with a rustic cabin, a smaller edifice that will nevertheless be sufficient enough. Or, maybe my structure will soar beyond expectation, sustaining me as I go forward into the grayness of age. Right now, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that I am here. And I am standing where my father stood when he first had the dream.

Photo by Joel & Jasmin Førestbird on Unsplash

The post Cabin Dreams appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

March 10, 2021

Chinese Takeout and Rustic Cabins

October 3, 2012: I am now on my third day of my writer’s retreat, or what I’m calling my writer’s retreat. I’ve come alone to the cabin my father built in the mountains of Eastern Tennessee. He had intended the cabin to be a temporary shelter for the permanent house he and my mother would build for retirement. They never built the house. The cabin has stood for nearly forty years, rustic, simple, and in my opinion, cozy. My plan is to spend the month here writing the first draft of my novel. It seems fitting to start it here. This is where I started my translation of Kirino Natsuo’s Grotesque. And as I noted in an earlier post Kirino started Grotesque in her friend’s mountain retreat in Gunma.

I doubt her friend’s cabin was as “rustic” as my father’s! But it made me feel a special bond with the author, knowing that we had both experienced the magic of the mountains at different ends of the creative process. Over the years I have found that my best writing comes to me in the mountains.

It took over ten hours to drive to Mountain City, TN from St. Louis. I arrived on October 1, 2012 close to 4:00 pm. I stopped for gas and water in town and then called my brother, Luke, to let him know I had arrived. He lives about forty miles away in Boone, NC, and had agreed to meet me to help me open the cabin. I headed next to the local Chinese restaurant—the Panda Kitchen—to pick up some takeout for our dinner. It was the restaurant my parents liked. They usually ate there when they’d felt like “splurging” after a week in the cabin.

Fully provisioned, I turned the car around and headed towards my parents’ land, meeting Luke a little after 5:00 at the foot of the mountain. I was still wearing the comfortable black jersey mini-skirt and tank top I had slipped into earlier that morning. It was in the 80s when I left St. Louis. The air was growing crisp here as the sun started to slip behind the mountain ridge. I dug a fleece cardigan out of my car. Luke laughed. He had stripped off his work tie and changed into a short-sleeved t-shirt. Now a mountain boy, he is accustomed to cooler temperatures.

The cabin has stood for nearly forty years, rustic, simple, and in my opinion, cozy. My plan is to spend the month here writing the first draft of my novel. It seems fitting to start it here.

We loaded his four-wheel-drive Honda with the Chinese takeout and all the things I had brought from home. The road to the top of the mountain was too rutted for my sweet city-slicker Saab to handle, we left it at the opening to the property.

The drive up was rough and the Honda bucked from side to side. Luke knew the road well and rolled with the curves. He gassed it around the right-hand turn where the road suddenly climbs. If you slow down and lose momentum, you’re likely to get stuck. And the road was muddy. He hadn’t been up it for a few months. But he ferried us safely to the top. And by “us” I’m including my rescue dog, Wilson.

When we crested the hill we saw, to our relief that the cabin was still standing. Leaving it vacant for months on end, we never knew what we’d find. (Once, years ago, after my father first built the cabin, someone broke in and stole a few items. They took my father’s rifle, which had belonged to his father. It wasn’t a pricey item. But it meant a lot. They took his tools, too, many he had since youth. When you come from nothing, those small things are precious. After that my parents added shutters and locks and left a sign out front begging anyone who might happen by not to damage the cabin. Perhaps the earlier vandalism was a fluke, or maybe the sign worked as a talisman, after that incident, no one else bothered the cabin again.)

When we entered, however, we found that the security had been breached. The intruders were of the four-legged variety. There were mice feces everywhere, the corners and crooks of the cabin now outfitted with nests of various shapes and sizes held in place by cobwebs and dust. In the late 1980s, my father had added a small utility room and adjoining bathroom The insulation he used in the ceiling and the heat baffling he wrapped around the water heater had proven attractive to the homesteading rodents. There were tiny pills of insulation strewn everywhere. I would have my work cut out for me in the morning. But tonight I was too tired to clean.

Luke turned the electricity on and tried to start the plumbing but couldn’t get it to work. Neither of us could remember the last time it had been used. Before he died our father hadn’t been able to travel to the cabin, and Mother had lost interest in it when she lost the man who built it. Luke offered to call a plumber in the morning. I was glad I’d had the presence of mind to stock up on water in town.

We had a nice dinner and mini-reunion and then he left. I found clean linens (my mother was always careful to secure the linens out of reach of the mice). I was too jagged from the long drive from Missouri to settle into sleep. But at some point I dozed, only to be awakened by a pouring rain. The sound on the tin roof was lulling. Even so, I willed myself to stay awake to enjoy it. When the first fingers of morning light slipped into the cabin, I willed the rain to end. It did not. I couldn’t control nature, not even my own. I had to slip into my rain gear and head outside to find a place to pee. Then it was time for breakfast, and a walk with Wilson.

The post Chinese Takeout and Rustic Cabins appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

February 24, 2021

From the Mists of Blue Mountains

I had a sabbatical in 2012, an entire year released from teaching and other academic duties (such as meetings, in addition to meetings, and occasionally and often more meetings.) The year release was one I negotiated as compensation for my six-year term as Associate Dean of University College and Director of the Summer School. My administrative duties meant that I had been “on” all year long, year in and year out, without the summer months typically open to individualized research projects. I was tapped out. I’d used up all of my earlier research materials on projects here and there, and I had nothing left in the tank.

The concept of a sabbatical year can be traced to an early agricultural practice arising from the Hebrew word shmita. The Torah stipulated that very seventh year a field be left fallow so that it could replenish itself. Aside from religious belief, the practice of leaving a field fallow makes good agricultural sense, otherwise the nutrients from the land are depleted. After six years of non-stop intellectual labor, I, too, felt exhausted, my store of mental energy diminished. My sabbatical could not come soon enough.

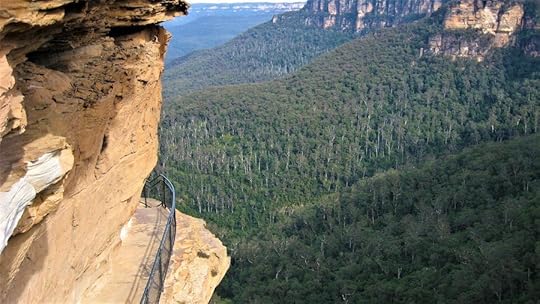

Shortly after I was released from duties, I traveled to Australia where I was scheduled to participate in a conference, following that I gave lectures at a couple of universities. I stretched my stay so I could travel in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales, where I spent two nights in Katoomba near the Three Sisters. From the top of the Three Sisters I took a long, steep, iron stairway down to the valley floor and hiked for the day through the deep, dark foliage enjoying the damp breath of the forest and the cries of invisible birds high in the canopy above me. I saw no one else on the pathway, though I noticed here and there the trash others had left behind. I crossed streams, scampered over slippery rocks, and rested alongside waterfalls. The whole time I told myself stories, imagining earlier travelers: imagining losing my way; imagining an encounter with an escaped convict. How would I survive? Of course, I didn’t get lost, and I didn’t encounter anyone—dangerous or otherwise! But during the time alone, immersed in the lush beauty of the Blue Mountains, I traveled into my own headspace and dreamed of new adventures.

That’s when I decided it was time to write my own mystery novel. I started charting the story as I walked. The novel would be set in Japan. And, it had to involve translation. The protagonist would translate a novel that would lead her to a murderer. Or maybe the novel would offer clues to an unsolved murder that had taken place in the past. The translator would decode the clues. She would be the hero!

The next day I hiked the Charles Darwin Trail to Wentworth Falls. The path crossed a muddy field before dipping into a dark forest. After only a short trek I came to a waterfall that cascaded over the edge of the world, or so it seemed.

From the waterfall there was an iron staircase that clung to a steep mountainside and led to the valley floor far below. The staircase (more like a ladder in places) offered spectacular views along with a lot of “air” or exposure. One slip under the guardrail and off the edge you’d go! In a small cave-like alcove along the cliff, the forestry service had posted laminated photographs from the early 1900s of day adventurers taking the same pathway. The women in the group wore long black skirts with hems that swept the ground. And yet there they were, on the same spine-chilling stairway as was I—in my sneakers and REI hiking gear.

What if my character interacts with someone from the past? I love the novel Possession by A.S. Byatt. Maybe I could create a story that unfolds on different temporal levels. Perhaps my character would uncover a hidden set of letters that draw her back in time. Of course, my character is a “her.”

I reached the valley floor and trekked along marshy ground, the air emanating from the lush ferns was cool and damp. As I walked I imagined the story of a writer who had once been up-and-coming but then had just disappeared. What had become of him? Lost in thought, I almost missed the return path and for a mile or so I worried that I had. I didn’t know if I should continue on or backtrack. I’d been walking for most of the day and it was growing late. I would not be able to retrace my steps before the sun set and I certainly didn’t want to be out in the bush at night. As with the day before, I had not encountered anyone else on the trail. I felt like I was completely alone in a foreign country. If I wasn’t careful, I’d become the protagonist in my own horror story. Just when I was on the edge of panic, I saw the pathway out of the valley and climbed back to the road, to civilization, and eventually to Katoomba. Back in my room at the 3 Explorers Hotel, I fired up my computer, navigated to Amazon, and ordered two books:

The Elements of Mystery Fiction: Writing the Modern Whonunit by William G. Tapply

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein

When I returned to the United States, I would begin preparing for my next journey, the one that would lead me into writing my first work of mystery fiction.

Photo by Henrique Félix on Unsplash

The post From the Mists of Blue Mountains appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.