Rebecca Copeland's Blog, page 9

November 9, 2022

Climbing My Way to Mars

“You take Jupiter, and I’ll take Saturn.”

We were studying the solar system in our fourth-grade class, and Linda thought we ought to create the different planets in our houses. We wouldn’t do all the planets. I mean, who wanted to recreate Uranus anyway? We planned to each build a secret fort in our house and name it after one of the planets.

“Why do you get to take Saturn?” I argued. Linda was my best friend. But she was bossy. Sometimes her dictatorial tendencies made me want to fight back.

“Because I claimed it first.”

In truth, the planet forts had been Linda’s idea. I couldn’t argue with her there. But I didn’t want the big old bloated Jupiter with its gassy atmosphere. I told her I’d name my fort after Mars.

Linda lived a few blocks from me in a big wooden house on North Main Street in Wake Forest, NC. She shared the house with two younger brothers, an older sister, parents (both of whom worked), and a set of grandparents. Like me, she had her own room. And like me, her room was airy and large with deep closet tucked into one of the corners. It didn’t take me long to ride my bike from my house on South Main Street to hers.

After we concocted the idea of building our secret forts, I slipped off to her house any number of times to assess her progress on Saturn. I discovered that she selected the planet for its rings. She strung up rings on ribbons in her closet fort, creating a pretty, glittery effect. But the rings tinkled every time we climbed up past them. Wouldn’t the noise give us away?

Surely our forts weren’t really “secret.” But I convinced myself they were. I put a “do not enter” sign on my bedroom door. And then I pulled all the sweaters and blankets off the shelves in my closet and stuffed them under my bed. It was easy to climb to the top closet shelf, even though it was over six feet from the floor. I papered the walls of the shelf in red construction paper—seeing as how Mars was the Red Planet—and little by little dragged pillows up there, a flash light, and my favorite Nancy Drew books.

When Linda would come to my house, we’d crawl up into the closet and hunker down among the pillows. The top shelf was far enough from the ceiling to allow two ten-year-old girls to sit comfortably. We wrote each other notes while we were up there (not wanting anyone to hear our chatter) and giggled. Before long one of us would have to go the bathroom and down we’d go, returning to planet Earth and our earthly needs.

Linda’s Saturn was bigger than my Mars. She always carried cookies and Kool-Aid along on the journey. We’d swing our legs over the edge of the top shelf and kick off into space, watching the glitter of the ribbon rings as we sipped our Kool-Aid.

And then one day her grandmother caught us mid-space and that was the end of our galaxy travel.

It wasn’t that we knocked to the floor the clothes she’d washed and folded. Nor was it that we risked life and limb clamoring like monkeys to the top shelf. It was the cookies. Her grandmother said we would attract mice and insects with our untidy ways. Something as paltry as a crumb foiled our space exploration.

Linda was forced to return her closet to its earlier humdrum existence.

My mother had not yet discovered my secret space station. I continued my travels to Mars, but it was boring without Linda. Still, I didn’t want to invite her back to my closet hideaway, since she had dismantled hers. It made her too jealous.

I started exploring my sisters’ closets. They each had even bigger closets than I had, and they were full of secrets: diaries and notebooks, broken lockets and tangled necklaces. Judy kept a box of mukhwas that she had brought back from India—over three years earlier!—candied fennel seeds, cardamom pods, and sugar crystals. I liked to open the box and pinch a taste, the flavor returning me to India. I was in second-grade when we lived there. It seemed so long ago.

Beth had an old cast in her closet, from when she broke her arm. It was white and chalky and split down the side, so I could slip it onto my arm as well when I stole into her closet. I imagined myself a wounded space explorer.

Eventually, Judy caught me filching her precious mukhwas. Beth caught me, too, parading in her cast. And Joy discovered that I would open her retainer box and stare at it every now and then. Mother scolded me for sticking my nose where it didn’t belong. I needed to respect other peoples’ privacy. I had no choice but to return to Mars, alone.

Linda and I had a falling out a year later. I said something to hurt her feelings, and she never forgave me. I might have tried harder to win her back, but my family moved about that time to a tiny box of a house in Raleigh. Even though a mere twenty miles separated me from my magical childhood home in Wake Forest, it seemed as far away as Mars itself.

Photo by Planet Volumes on Unsplash

The post Climbing My Way to Mars appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

October 26, 2022

Basement Dreams

The recent flood in my St. Louis house has put me in mind of other houses I have lived in along the way. Houses are so much more than shelters. They are more than prized possessions. They are containers of memories. The houses we have lived in and left shape the dreams we have long after we have moved away from them.

When I was little, I lived in a magical house in Wake Forest, North Carolina. It was old and wooden with tall white pillars on the outside holding up a wrap-around porch. The rooms inside were cavernous, and the light pouring in through the windows made square patches on the floors that danced and shimmered throughout the day. The house was full of secret hiding places—a broom closet under the stairs, an attic that smelled of summers past, a basement black with coal, and a child’s imagination.

On cold winter nights the furnace in the basement roared and heat seeped up through the vents on the floor. Sometimes I could hear my father down below shoveling coal into the fire box, groaning from the effort. We children were not supposed to go into the basement, but sometimes I’d slip down to watch him labor. He stripped down to his thin sleeveless undershirt and shoveled the coal into the firebox, the muscles on his long arms bulged and glistened with sweat.

When he opened the door to the firebox, the heat roared out, striking my cheeks full force, turning them a ruddy red. I stared long into the flames licking up around the coal in blue and white tongues, wondering if I’d see Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego step out unscathed, just like in the Sunday-School Bible story.

“Don’t get so close!” My father warned.

He put on a thick padded glove and closed the door to the box with a long metal tool.

In the morning he would drag the burnt-up clinkers out to the side yard where they would glitter menacingly.

“Don’t climb on those,” he warned, knowing my proclivity to do so. “They will cut you to shreds.”

He was right.

Once I fell on a stray clinker when I was playing nearby, and it cut my hand as certainly as a shard of glass.

Eventually, he would build a fence around the spent coal. And when he managed to save enough money, he installed an automatic coal feeder in the basement, limiting his trips into the dark depths.

But the basement remained a “no-go” place for children. To enter you had to go out the backdoor of the house, down a flight of outdoor stairs, through a heavy door, and down a steep open wood staircase with an iron railing. It was dark and dank and smelled of clay and sweat. It was beyond the watchful eye of my mother.

Basements and cellars often conjure primeval horrors. Dark, unimaginable things happen in the space beneath the house where earthen floors give way to hidden passageways and tunnels. Monsters lurk in the loamy blackness of the underground.

Stories about cellars are usually tinged with horror. Think Edgar Allan Poe and “The Cask of Amontillado.” As a child, I craved mystery and the tingle of fear that crept along the base of the neck. I wanted to sneak into the basement when my parents weren’t looking. I wanted to find that passageway into the inner core of the next world.

They say if you dream of descending into a cellar, of digging into the dark subterranean clay, you are “in harmony with the irrationality of the depths” (Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 1957). Basement dreams may be frightening, but they offer endless possibilities and a working through of deep psychological states.

Despite the allure of the basement, I rarely have basement dreams. I do, however, have a very real basement memory.

One cold December evening my brother and I were playing near the heat vent in the dining room and heard my father in the basement working on something. Clang, clang, the sound that rose up through the vent was brighter than the scraping sound he made when he worked on the furnace.

Thud.

“Fiddlesticks!” he shouted. “Got to keep from cussing.”

His voice rumbled up through the vents in a strangely disembodied way.

My little brother and I giggled uncontrollably, pressing our hands to our mouths with glee. It was fun to eavesdrop on our father. We were spies!

What was he doing?

We asked him when he eventually arose from the pit and washed his hands in the kitchen sink.

“Never you mind!” he barked.

On Christmas morning we discovered his secret.

He had made us a sled.

He fashioned the runners out of the legs of an old ironing board. It was the sound of him pounding the round legs into flat blades that had risen through the vents. It was the moment he caught his thumb under the hammer that occasioned his fit of near cussing.

It rarely snowed in our little Southern town. But at the first sign of a flake we dragged the sled out to the nearest hillside and gave it a push. The wood, the metal, were all too heavy to slide, despite our father’s best efforts. One of us had to drag it down the slope to make it glide.

But the sled rang with love.

“Fiddlesticks!”

We adored our father all the more.

Tunnel photo by Luis Vidal on Unsplash

The post Basement Dreams appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

October 12, 2022

The Road Taken

Lately I have been receiving emails with job announcements—not for my students but for me.

Rebecca: Washington University in St. Louis jobs and others we think you will like!!

Amazon Driver! Flex-time options.Valvoline Lube TechnicianAnheuser-Busch MachinistWith the exception of perhaps the first, I’m not even remotely qualified for the jobs they send. Plus, I’m not looking for a job. If anything, I’m looking to get out of a job, trying to find my way to retirement.

I’ve had my share of jobs in the past: bus driver, pizza delivery runner, braille typist. All of these were necessary to get me to the job I have now, the job that is my career, my way of life really, and so much more than a means to a paycheck.

Becoming a professor was never about the money. I wanted fair pay, of course (which is not always a given and even now is the source of great disparity based on discipline, gender, and clout.) The money wasn’t the point. It was the commitment that mattered, the understanding that I was in it for the long haul and that it would be a “job” that had goal posts but few boundary markers. The field was always in play, the penalties were many, and time outs were rare.

Being a professor has meant working on the weekends, working through holidays, working during the times others don’t work because that is the best time to be productive. Weekdays are cluttered with professional activities: meetings, teaching, meetings, advising, and more meetings. The weekends are usually unstructured, allowing the time to do the kind of thinking one needs to do to write.

I have often found myself facing a Monday morning feeling exhausted from a marathon weekend of rushing to meet deadlines, scrambling to concoct a last-minute letter of recommendation for a student, reassessing a grade, reviewing a dissertation chapter, and then preparing for classes. That’s when I often wonder what it might be like to work for Anheuser-Busch or Valvoline, to punch in and punch out, to leave work on Friday and not look back, to lock the door until Monday. I fantasize about the kind of job that comes with weekends.

Years ago, after my first year of graduate school at Columbia University, I spent a summer in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania where my fiancé and soon to be husband, Dennis, lived. While he taught summer school, I worked at a seafood restaurant tucked into a quiet hillside off a rural road. I don’t remember the name of the restaurant now. I think it was in Carlisle. All I remember is that the owner was an affable white-haired man named Fred.

Fred had me work the bar. I probably represented myself as having experience as a bartender. The summer before I had worked at Charlie Goodnights, a bar in Raleigh, North Carolina. That’s where I met Dennis. Only, I worked the 3:00-8:00 pm shift, which was hardly ever busy. Moreover, at the time bars in NC could only serve beer and wine. My bar skills were limited to opening bottles or drawing a draft.

In Pennsylvania bars offered liquor of all variety, and I quickly had to learn to make an assortment of drinks—whisky sours, screwdrivers, and martinis. The crowd at Fred’s restaurant did not have elaborate tastes. Most preferred beers and wine in carafes.

But there were days when we were busy. I usually worked with a bartender named Judy who seemed to have been born to pour drinks. She could mix up an assortment of cocktails without once looking at the recipe or relying on a measuring cup. Next to her, I was as slow as a snail. Judy was kind to me and always willing to remind me how to mix a Harvey Wallbanger or a rusty nail. But when we got busy, I was in her way. Her hands would fly over the bottles, grabbing, pouring, stirring, and then she’d whirl across the floor sliding drinks in front of customers. Half the time she’d have to elbow me out of the way, too busy to even articulate the word “MOVE.”

Judy was middle-aged. Her voice was raspy from cigarette smoke, her short-cropped hair complemented her small elfin frame. I admired her and her ability to sling drinks. I wondered how long it would take me to develop the skill. Certainly more than a summer. And a summer was all I had. I was on my way back to New York in August to bury myself again in the Kent Hall library.

Fred wanted me to stay.

“Why do you study Japanese?” he asked time and again, incredulous that anyone would think it worthwhile. “Stay on here. I need a manager.”

How Fred could see me as management material I could not understand. I think the fact that I had a college degree impressed him.

When Judy found out Fred had offered me the management position, her cheerful asides ended. The elbows she threw when we were busy grew sharper.

I can’t say I blamed her.

Still, I thought about Fred’s offer.

Graduate school was rough—more bruising than Judy’s elbows. I hardly had time to sleep. And since money was so scarce, I hardly ate. The other students seemed so much stronger than I was, and most were spending their summers—while I avoided Judy’s elbows—in Japan improving their Japanese.

Maybe I wasn’t cut out for academics. What if after all the studying and starvation I couldn’t find a job? Wouldn’t I be better off running a restaurant?

One evening Fred invited me to join him on an adventure.

He took me with him to the Baltimore markets to buy provisions. He made the trip once a week. I climbed into his small pickup truck. His good friend Walter piled in next to me. We left just after midnight, the two-hour trip landing us at the docks around the time the fish vendors opened. I watched Fred and Walter select the seasonal seafood. After that we headed to the produce markets, and by the time we were finished, the back of Fred’s truck was laden with food. The fish was stored in ice, allowing us to stop for breakfast before heading back along the winding rural roads to Fred’s restaurant and home.

Sitting between the two old friends was the highlight of my summer. Sleepily watching the sun rise over Pennsylvania farmland, I enjoyed the way Fred and Walter joked and cussed. When we got back to the restaurant we shared an early beer, just the three of us, at the bar. Fred poured.

This could be mine, I thought to myself. This could be my life. This could be my nine-to-five.

When the summer ended, though, I took a different road.

I never returned to that restaurant.

I never saw Fred again.

I don’t even remember his last name.

But sometimes when I come to a Monday wishing for a weekend, I think of that ride to Baltimore and the laugher we shared.

The post The Road Taken appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

September 28, 2022

Flood of Losses, Mountain of Riches

The ping of a text message drilled into my ear. I was drifting along a wave of dreams, enjoying the sounds of morning gradually overtake my mountain house—the summer insects, the birds, the drip, drip from last night’s rain. If I answered the text, I would have to open my eyes and pick up the phone on my nightstand. I would have to leave the comfortable grey space between wake and sleep.

Ping.

Insistent.

I rolled over and reached for my phone, patting the surface of the night stand until I touched it.

“Waters continue to rise. Can’t see the top of my car now.”

Dale was a friend down the street from me in St. Louis—over six hundred miles away from my perch in the mountains of North Carolina.

What kind of game was he playing? It was barely 5:00 in the morning there. He never texted that early.

Whatever joke it was, I didn’t find it funny. I put the phone back on the bedside table and tried to tuck back into my dream.

Ping.

I sat up in bed and grabbed the phone off the stand, feeling a tad annoyed.

“Really?”

This time the scene in the photo he sent was vaguely familiar. It was a shot of the street from a high vantage point facing from Dale’s house up to mine, half a block away. Only, it did not look like a street. It was a lake.

“The neighborhood is sinking! Will have more information when the sun comes up.”

“Good thing you have a canoe,” I quipped, trying to join the game.

“If it hasn’t washed away. The water looks like it’s made it to your house.”

“Send a photo, please,” I challenged, beginning to feel nervous.

“When the sun is up.”

Finally understanding that Dale wasn’t kidding, I texted my next door neighbors and they confirmed the worst, sending me photos of my backyard under water.

Flooded Backyard. Credit: Joanne Kern

I made plans to return to St. Louis the following day, allowing myself time to close down my mountain house.

The drive was excruciating. The whole way I tortured myself with visions of loss—all eleven hours through Tennessee, Kentucky, and Illinois—imagining the worst. Why didn’t I have the proper insurance?

Why hadn’t I been more careful?

I would come to understand that no one not in a flood zone had flood insurance. There was little I could have done to protect my house. Of course, I could have stored all my books and photos on the second floor. But, space in those tiny closets was limited, and how could I have imagined over six feet of water in a basement that had never had so much as a trickle. It was inconceivable.

Iva called when I was only a few minutes from St. Louis. She was awaiting my arrival. How did she know when I would get there? I hadn’t told her of my departure or ETA. But there she was with a large aluminum pan of burek—a delicious Bosnian pastry she introduced me to earlier—and a bottle of wine. How did she know I would not have access to a stove, that the gas had been disconnected? How did she know I needed her then more than ever?

She walked with me into the basement.

I don’t think I could have handled it by myself.

The carpet on the stairs squished under foot and smelled horrible. The hallway was dank. The water had receded, but we could see the water line on the walls just inches from my first floor. I had been lucky.

Dale’s first floor had been completely submerged. He had texted me from his attic.

My washing machine was turned sideways. The massive wooden work benches that had been in the house when I’d bought it thirty years ago had been tossed across the floor. One now tilted perilously.

Outdoor plants had been washed indoors. My backdoor was gone.

Books, papers, tools, blankets, the contents of my pantry, the contents of my utility chest, all were strewn about the floor of the basement and covered in muck. I learned that the flood had begun as backup through the drains—sewage—and then was met with the press of mounting water outside.

It had rained nine inches in the space of a few hours, twelve inches in some areas. The ground was hard and dry and unable to accommodate the deluge. The sewers were old and clogged and incapable of carrying away the downfall. Within hours, while most of my neighbors slept, our houses filled with water.

One family, upon waking to the sound of their basement windows crashing under the weight of the flood, waded out into the torrent—mother, father, adult children, family dog—and pressed forward in chest-high water until they reached higher ground. A relative picked them up and carried them to safety.

Dale told me of another neighbor who tried to do the same and was on the brink of being swept away when a quick-thinking man, watching the storm from his porch, threw him a rope—a literal lifeline.

Not everyone was as lucky. The flood claimed two lives in the St. Louis area.

When Iva left, I unpacked my car and ate the feast she’d brought, charting my course of attack. Although my living space had been spared from the rising waters, the smells of the basement rose to the second floor, enveloping me, invading my dreams as I tried to sleep. I felt I was trapped in a sewer. In a few days I would no longer notice the smell. It would surprise me when outsiders to my neighborhood would remark on the odor, stating they could smell it blocks away.

When day broke I pulled on the old hiking pants I wear for yard work. I grabbed the rubber gloves under the kitchen sink and began hauling away the detritus of my life. My neighbors had suggested it was important to get as much of the wet material out before mold set in.

The extra packs of toilet paper and paper towels were so waterlogged, they were too heavy for me to lift. I concentrated on the smaller things, like the old store-bought quilts I’d neatly stored in my cedar closet. I never used them. I had long planned to give them away. Now they were ruined.

There was the wedding dress I had worn once on June 21, 1980. I don’t know why I had saved it. None of my nieces would have wanted it. But there it was, soaked in mud, along with my wedding pictures.

Faded photograph. Credit: Author’s photograph.

The plastic bins in the cupboard were filled with water, their contents ruined.

I had heard, though, that if you kept the photographs wet, you could eventually dry them. Some papers could be restored by freezing them. I found a bin of my father’s sermons, some hand-written. They had miraculously escaped the waters. I rushed them to the freezer just to be sure, taking comfort in his familiar scrawl.

And so it went.

My friend Laura had told me to call a professional clean-up and mold remediation service when I first told her of the disaster, while I was still in North Carolina.

“Call them now!” she insisted. “Get on the list. They’re going to be backed up.”

I called. She was right. I was put on a waiting list.

The company sent a crew to my house on Friday. I arranged for them to also attend to my neighbor’s place. Between the two of us, we shared a dumpster along with our trauma.

As I sat on my deck peeling photographs off damp album pages, I heard my neighbor telling the cleaning crew about the items they were dragging from his basement.

“Do you know what these are?” he asked. “These are my grandfather’s engineering books from 1920. He was an engineer, my father was an engineer, and now I’m an engineer.”

I could hear the pain in his voice. There were his grandfather’s books, his father’s tools, and his high school yearbooks. He had always assumed they would be with him forever.

Our cleaning crew was from Hawai’i, though most of the members were Samoan. The crew down the street was from Oklahoma. Another crew had come from Kansas. From house to house the shouts from the crews resounded with different accents.

In a way, it was like a big block party. All my neighbors were in their yards. We called to each other as we made trips from our basements to the dumpsters. We shared, we commiserated, we even managed to laugh.

After my first day of cleaning, a professor at my university contacted me by email. We don’t know each other well, but we exchange pleasantries when we meet on campus. She had heard from Iva about my house. She wondered if I needed anything.

Within the hour she was at my house with a bag full of prepared foods—ratatouille, rice, bread, fruit, another bottle of wine!

I had told Nancy I was aggrieved to have discovered I had no coffee in the house the morning after I returned home. All that cleaning on no caffeine made me tempted to turn to the unopened bag of Kaldi’s coffee I found in the basement pantry. It had floated through the debris. Maybe it wasn’t ruined? That afternoon I found a new (clean) bag of coffee on my front porch!

Even a former boyfriend resurfaced when he learned of my plight and offered to help me clean. By then I had paid in advance for the professional crew and was instructed to stay out of the basement until they arrived. Undeterred, he ran out and purchased a large floor fan to blow the foul odor away from the house. I was touched by his sincerity.

And so, there was a flood in my basement. I lost everything. Not just the personal things, the carriers of memories. I lost mechanical things, too, the hot water heater, the boiler, the electrical panel.

The mechanics are easy to replace but expensive. The personal things are not worth much but are irreplaceable.

I also gained a new awareness of the deep way people care for each other—people I had never expected to notice me came forward with wonderful gestures of kindness. I received what I needed when I needed it most.

I am, through the trauma of loss, far richer than when I started.

The post Flood of Losses, Mountain of Riches appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

September 14, 2022

The Mistakes I Made on My First Trip to Japan!

Overheated, overdressed, and definitely over the idea of traveling with my parents, I plopped down on my suitcase right there on the platform of Ueno Station in Tokyo, Japan. My suitcase was a bright red hard vinyl rectangle. It was part of a matching set that I’d gotten when I graduated from high school in 1974. It came with a smaller version as well as a “train case.” It would have made more sense to have had the “train case” with me, since I was waiting to board a train. But my mother had told me to leave it behind in America. We’d have enough to carry as it was.

“You and your brother can only bring two suitcases each,” she had told me repeatedly. “You can’t bring any more than you can carry.”

How unreasonable it all seemed to me. I was planning to spend an entire year in Fukuoka, Japan with her and my father. How on earth was I supposed to survive on only two suitcases worth of clothing? As it was, I couldn’t even fit my shoes into the smaller red case. I cut a deal with my younger brother to let me stuff some of my things in one of his bags. After all, he’d only be in Japan for the summer.

My father, who had traveled ahead of us by several months, met us at Haneda Airport. He seemed happy to see us, until we kept pulling one suitcase after another off the baggage carousel.

“I thought I told you to travel light,” he said to my mother. She looked at him and rolled her eyes in my direction.

After we got through customs, my father told us to grab our things, we were going to take the monorail. He made it sound as thrilling as a Disneyland ride, probably to cover up the fact that we would have to carry our own stuff—just as Mother had warned.

The plan was to take us first to Lake Nojiri in Nagano Prefecture where we would spend a few weeks acclimating to Japan. Nojiri-ko was a well-known summer destination for foreign missionaries, a cheaper version of Karuizawa. My father had borrowed a cabin there from a fellow missionary. My parents were doing everything they could to make the Japan journey pleasant for my brother and me. Neither of us had really wanted to come. They figured a week with other American kids our age would do the trick.

Lake Nojiri, 2007. Credit: jenterri, Wikimedia Commons.

So, there we were on the Ueno train platform, after taking the monorail from Haneda and then the Yamanote Line in what had to have been a long-lost route on one of Dante’s circles of inferno.

I had never been so self-conscious in all my life. Everyone was staring at us.

And why wouldn’t they? We had become a portable roadblock of listless teenagers and harried parents dragging mountains of luggage on and off commuter trains.

My father, the only one in the group who knew Japanese, hustled us on to a pristinely clean train the instant the doors opened, luggage and all. Then he parked us by the doors and told us not to block the entrance. Hard to do when you’re a portable roadblock. We were all so big and so awkward and so much in the way. People shoved at us and glared as they tried to exit or enter the doors we were blocking.

“Pay attention!” He warned. “The train does not stay long in the station. You have to be ready to jump out.”

Jump out? Where was I going to jump out? What if I don’t jump out in time? I could feel my heart begin to pound.

For some odd reason, I started to practice asking for directions in French. I couldn’t speak Japanese, and French was the only foreign language I then knew. So, parlez-vous français?

It was summer and the train compartment was sweltering. Coming from North Carolina, I was used to the heat. But this was something altogether different. Plus, either there was no air conditioning or it was barely on. I was relieved when we finally did “jump out” of the train and onto the platform, only to discover the heat there was just as oppressive.

Prepping for my year in Japan, I’d splurged on a very stylish off-white trench coat. For the airplane trip, I wore it over white linen trousers and a white tee-shirt. I topped off my look with an ecru-colored straw hat festooned with a shell-studded tassel. You know, like a sexy French movie star dressed glamorously for travel.

As I sat there on my red suitcase starring glumly at the hordes of people pushing past me on the platform, I realized the error of my chic ambitions.

In the first place, who in Japan wears a trench coat in July!?

Mother had told me about the rainy season, and I thought I’d been so clever. The lining of the coat now stuck unpleasantly to my arms. I desperately wanted to take it off, but I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to carry it and all my baggage. My stiff straw hat was making my scalp itch, and my head pounded as I sat there in my self-imposed sauna, feeling the sweat trickle down my back.

“Once we get on the next train we can relax a bit,” my father promised.

I don’t remember much more about the journey to Nojiri. I just remember that a friend met us at the station in a big car and drove us luggage and all into the mountains, depositing us at a very rustic cabin. Close to the lake, the breeze was brisk and the air much cooler than it had been in Tokyo.

My father and mother left us there while they went with the friend to a small village to buy food for our dinner. It seemed like ages since we had eaten.

There was a small charcoal grill outside the cabin. Mother must have already known this because she came back with hot dogs.

What a curious way to spend my first evening in Japan. It hardly seemed appropriate for a young ingénue in a white trench coat to dine on hotdogs.

“It’ll be fun! Like a cookout at home!” My mother tried to fire up my enthusiasm.

My brother was more cooperative. I sulked a bit as I set the table but in truth, I was famished.

We sat around the charcoal grill watching Mother turn the hot dogs with long chopsticks. She wrapped each one in a slice of bread before handing it to us.

ミニホットドック, Credit: Spiegel, Wikimedia Commons.

“These don’t taste right,” my brother was the first to sound the warning.

I took a tentative bite and spit it out immediately.

This was no hot dog. It was made of fish. I hated fish.

Mother’s smile turned to dismay. She had wanted us to enjoy a bit of “comfort food” after our long journey. Unable to read the package, she had no idea the “hot dogs” she had purchased were really fish cakes in disguise.

“I’m so sorry! Let’s roast the marshmallows.”

You can’t really ruin marshmallows, I thought.

Wrong!

Those marshmallows were full of bean paste!

I went to sleep hungry that night.

But in the weeks to come everything changed.

Some of the other missionary kids who had grown up spending summers at Lake Nojiri took my brother and me to the Asunaro Trout Farm where we fished for our dinner. The staff prepared the trout according to our request.

“Sashimi,” my new friends called out.

Then and there, this silly ingénue who didn’t like fish, decided that it was time she needed to grow her taste buds up.

That night I ate freshwater sashimi and loved it. I drink beer that I had earlier thought I hated. And just like that a whole new world opened up before me.

Mother stopped trying to make “American” food. And I stopped trying to be an ingénue. I started to eat fish and bean paste treats, too. Little by little, I fell in love with Japan.

And I learned never, ever pack more than you can carry.

Top photo by Erwan Hesry on Unsplash

The post The Mistakes I Made on My First Trip to Japan! appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

August 31, 2022

Winning by Losing: Why I Enjoyed Running Races in Japan

Japan is a great place to run races. People are generally supportive of runners and racers and are eager to cheer even the slowest on the field.

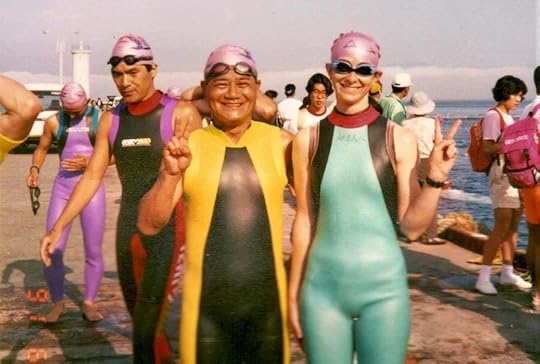

Years ago, when I lived in Mitaka, Tokyo, I ran a lot of short-distance road races. Inspired by the encouragement of the crowds, I eventually decided to try a triathlon. I ran a few sprint-length events in the Shōwa Memorial Park outside Tokyo.

And then, in 1991 I entered the longer Izu-Ōshima triathlon—with distances of 1.5km swim; 45km bike; and 10km run. It was the last triathlon I did in Japan. In fact, it was the last triathlon I ran ever. It remains my favorite.

I actually medaled. Kind of.

I took the ferry to Ōshima from Tokyo the day before the race and checked into a local inn. Almost all the race participants did the same. The triathlon start was early the next morning.

Shortly after arrival on Ōshima, the race officials had a meeting with all the participants to explain the rules and the course. I remember a young man—a boy really—from New Zealand asking me if I understood what was being said.

When I said that I did, he asked me questions about the course. I hadn’t listened with the kind of care needed to give him the answers he sought.

“Just follow the crowd,” I said. “That’s what I plan to do.”

“What if I’m leading the crowd,” he replied.

“You’re competitive?” I asked with some astonishment.

“I plan to win.”

I found one of the race officials and helped the future winner with the questions he had.

The next morning I ran into him near the start of the swim, and that’s the last I saw of him.

The 1.5km swim was intense. I’d competed in outdoor pools but never in open water. All the entrants were required to wear a wet suit. Since I didn’t have one, I borrowed one from a man in Tokyo who was about a head shorter than me and foot wider.

Awaiting the start of the swim in my ill-fitting wetsuit. 9 June 1991. Author’s photograph.

During the swim, faster athletes swam right over the slower ones. Since I was in the latter category, I spent a lot of time underwater trying to find space to come up for air.

I’d been told to expect the churning, but found the physical contact with other swimmers exhausting, even a little terrifying at times.

I was relieved to reach the end of the swim, only to discover I had to clamber up onto a dock instead of racing onto the beach.

The line to climb the ladder was so backed up, eager competitors started scrambling up onto the pier from the choppy waves below. I tried, but the crotch in my wet suit had slipped to my knees, preventing me from pulling my legs up. I was stuck clinging to the pilings while others behind me used my body as their impromptu ladder, climbing up and over me—and ON me.

Finally, two of the race officials grabbed me by the arms and hoisted me onto the dock. Off I went to my bike, as fast as I could with my knees swaddled in neoprene.

Out of the water and heading to the bike. 9 June 1991. Author’s photo.

The bike was my strong event and I sailed up the mountain roads, careening along the curves, passing many who had swum over me.

In preparing for the race I had biked every weekend along the mountain roads outside the Yokota Airbase, where I had friends and biking buddies. It didn’t take us long to leave the base and reach the countryside.

Often we’d encounter professional keirin track-bike racers training for their Tachikawa Velodrome bouts. Even though they had only one fixed gear, or so we were told, they worked their way up the same steep slopes almost as quickly as we did. The bikers had thighs as thick as tree trunks.

Keirin racers sprinting to the finish line in the last lap on the Omiya velodrome in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Credit: Paulkeller, Wikimedia Commons.

We could pass them on the incline. But once we hit the flats they outpaced us in no time—riding tight behind their pace car.

The experience of racing the keirin bikers, helped me with 40km leg of the Ōshima triathlon. Sadly, the ground I made up on the bike, I lost on the run. My calves started to cramp after 3km. I had to hobble the rest of the 7km in something akin to agony.

But the spectators were glorious—cheering me on. The runners who passed me, too, offered words of encouragement.

One reason I loved running races in Japan so much was just this kind of comradery. I was not a competitive runner. I was ippan 一般—ordinary! And the ordinary runner is beloved for their very ordinariness.

By the end of the race I had befriended a number of women who were equally ordinary. We found one another in the grassy field where the award ceremony was held and feasted on the free food while we watched the winners take their bow.

The Kiwi boy came in first.

After the competitive runners were acknowledged and rewarded, the announcers shifted to the ippan runners. They went by sex and age group.

Just when I was midway through my second onigiri, I heard them calling my name over the loudspeaker: Rebekka Kopurando

What?

I had not expected that. I hobbled to the stage amongst the cheers of my new friends and their friends and almost everyone else on the field. (The Kiwi and I were just about the only non-Japanese in the race that day.)

I’d come in sixth in my age group.

Not bad.

Pretty good for ordinary.

The ferry ride back to Tokyo was full of laughter and fun.

I wish I could say the story ended there. But it didn’t.

After reaching my apartment in Mitaka, regaling all my friends with my great honor, and assigning a space on my bookshelf for my trophy, I received a letter from the Japanese National Triathlon Association.

They had made a mistake. I was seventh, not sixth, and would I return my trophy at my earliest convenience.

My friends were furious for me. Why couldn’t they just let you keep the trophy; they could order another one for the real sixth-place ordinary woman?

“Keep it!” some encouraged me.

But no. The trophy was tainted now.

I sent it back.

Later I learned that the boy I met from New Zealand, Cameron Brown, earned his way onto the Japanese team, Epson, and raced every summer in Japan for about seven years. He won his first Ironman New Zealand in 2001. He won his twelfth in 2016 at the age of 43.

And me? I may have lost the trophy, but I won a story.

Trophies collect dust.

My story still makes me laugh each time I tell it.

Izu Oshima Finisher

The post Winning by Losing: Why I Enjoyed Running Races in Japan appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

August 17, 2022

My Father’s Other Son

When I was born my father’s colleagues sent him condolences.

I was the fourth daughter.

The year was 1956, long before parents knew about “gender reveals.” Mine had prepared for a son. Of course they’d have a son. How could they have another daughter?

But I was contrary.

And since my parents were then living in Japan, I was also excessive. Unnecessary. Grounds for condolences.

My mother told me that they were secretly furious at the outpouring of sympathy. “How dare they express regret over a perfectly healthy baby?”

Publicly my father made a pun—using his skills in the Japanese language. Otoko no ko wo shussan subeki datta ga Becky wo shussan shimashita.

We were supposed to have a boy, instead we had a Becky.

The pun is in the repetition of the sound “beki/Becky.”

Shortly afterwards my parents relocated the family of four daughters to the United States and the condolences stopped. But two and a half years later, when my younger brother was born, my parents’ friends in Japan sent them large koi nobori carp kites in celebration.

Despite himself my father could not wait to fly the kite on May 5th, in honor of Boys’ Day—in honor of his son.

He attached it to the roof of our old wooden house in Wake Forest, N.C. But it just didn’t have the same impact it would have had fluttering proudly in Japan. Passersby asked about it, wondering if perhaps my father was a prodigious fisherman. Or perhaps it was some kind of signal? A celebration yet unknown.

I was strong and fearless. I knew no boundaries. If there was a dangerous edge, I wanted to be as near to it as possible. If there was an upright ladder, I wanted to be on the top rung. If there was a wild animal, I wanted to touch it.

I’m not sure how long my father kept up the practice. He may have felt it insulting to the four daughters he already had. The fish kites were packed and stored away.

Perhaps because I was expected to be a boy, perhaps because I was born contrary, perhaps because it was simply my nature, as a child I preferred being my father’s son.

I was strong and fearless. I knew no boundaries. If there was a dangerous edge, I wanted to be as near to it as possible. If there was an upright ladder, I wanted to be on the top rung. If there was a wild animal, I wanted to touch it.

In a tree with my younger brother, Luke. Credit: Author’s photograph.

In elementary school I was the best on the field playing softball. I hit home runs almost every time at bat. When it came to dodge ball I was the most nimble, in tag football I was the quickest.

And then I turned twelve and everything changed.

Girls played different games. We wore puffy pastel shorts in gym class with matching button-up blouses, and we focused on toning and stretching. The boys wore singlets and cleats and ran on the track until their hair matted with sweat. Girls were cheerleaders, boys played sports. I stopped hitting home runs.

My father taught my brother how to mow the lawn and trim the shrubs. I helped my mother with the kitchen. I learned how to curl my hair, tweeze my eyebrows, and paint my nails.

That was so many years ago.

I don’t regret the life I lived. But sometimes I wonder what might have happened if I’d been celebrated for those home runs.

Photo at top by Benjamin Davies on Unsplash

The post My Father’s Other Son appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

August 3, 2022

Beyond the Vanishing Point: Traveling the Map of Memory

I stood on the bridge feeling perplexed. Nothing was right. There should have been a small lane here next to a beauty salon. It was gone. Not just the beauty salon, but the lane, too. Perhaps I was on the wrong bridge.

I looked up and down the river and saw bridges in either direction. Any one of them could be the bridge I thought I remembered.

I began to feel unmoored. I’d been walking through the streets of Fukuoka for several hours now trying to remember my way home.

Home? Really? I had only lived in the house on Torikai for a year. After that I would visit my parents occasionally on summer break or winter vacation. It wasn’t really my home, was it? My home was in America, or someplace.

But that year. That year had been special. It had made all the difference. That was the year I fell in love with Japan. It was the year I also truly fell in love with my parents. The fourth of five children, I’d never really had them to myself. That year, it was just me and them.

“But that year. That year had been special. It had made all the difference. That was the year I fell in love with Japan.”

Having lived in Fukuoka earlier, in the years before I was born, they knew their way around. But I didn’t. I was practically helpless, and after I arrived in the city I had to depend on my parents for almost everything—much as I had when I was a child. It was strange. There I was, nearly twenty-years-old and needing my mother to walk me to school.

For the first few days after my classes started at the university, my mother guided me through unfamiliar streets. We strolled purposely through the crowded Nishijin market, past carts laden with fruits and vegetables, past the fish mongers, past all the stalls that wafted pungent smells my way, smells I had never encountered before.

Nishijin Market 2019. Author’s photograph

In the beginning, I wrinkled my nose and urged my mother to hurry. Later, I grew so accustomed to the odors I hardly noticed them. Now, after decades have passed, I crave them.

From the fall of 1976 to the summer of 1977 I took that route any number of times, so often I no longer needed to count the traffic lights or look for the landmarks. Left at the beauty salon, right by the stall selling underwear, two carts of vegetables, three fish mongers, and then left by the Mister Donuts shop where they blared advertising jingles nonstop. “O-ha-yoo, Mister Donuts. Konnichiwa, Mister Donuts.”

I couldn’t read any of the street signs then. I felt my way through Fukuoka, relying on my senses. I was like a child lost in the wilderness, depending on sight and smell.

I couldn’t read any of the street signs then. I felt my way through Fukuoka, relying on my senses. I was like a child lost in the wilderness, depending on sight and smell.

Larger places remain in my memory: Hakata Station, where I ended up unexpectedly in an omiai (arranged marriage) meeting; Hoshiguma, where I was born on the kitchen table; Nishijin, where Mother and I would walk the busy market to grocery shop; and of course, Seinan Gakuin, where it all started—where my father taught and where I spent a year of study that would transform me forever. These places are easy to find. They are listed on the map. Just say the name and a taxi driver can get you there.

Then there are the more phantom associations: “George’s,” a small bar where I tried my first gin fizz; “Torijin,” where they served yakitori on a plate of vinegared cabbage. Both were within walking distance from my house. But which way? It would be impossible for me to remember now.

I have snapshots of memories. George behind his bar in a bowtie, his English polished by the years he catered to American servicemen, back before they closed Itazuke Air Base. The men at Torijin calling a loud welcome when my friends and I rattled open the sliding door. The sharp smell of vinegar and grease greeting us as well.

And then there’s my house itself somewhere in Torikai. A single-story bungalow surrounded by a cinderblock wall. There were sago palms in the garden and a large camphor tree. Only, I can’t remember the address. Nothing is where it is supposed to be.

My memories are strong. But I have little to pin them on. The city has grown so much in the interim. Walking along streets where I might have walked forty some years ago—I find only the phantom of the past.

I want to remember but the map that has been scored on my memory was never clear and now is only a palimpsest, a fading etch-a-sketch.

I want to remember but the map that has been scored on my memory was never clear and now is only a palimpsest, a fading etch-a-sketch.

I’m angry at myself for not paying more attention when I lived here. Why didn’t I commit the place names to memory? Why did I assume I could always retrace my steps, relying on my senses? Why did I think my parents would always be here . . . be with me?

The writer Yi Yang-ji (1955-1992), or Lee Yangji, perfectly expresses the fragility of memory in her essay “Fuji-san.” A memoir, she uses it to detail her love-hate feelings for the iconic mountain. As a young woman the mountain represented Japanese imperialism and all the cruelty visited upon Koreans in Japan, particularly those forced to labor.

Mt. Fuji, photo by Filiz Elaerts

Yi grew up in Yamanashi Prefecture, under the shadow of the mountain, where she felt constantly surveilled and confined. Later, after she left Japan for Korea, she found herself irresistibly longing for Mt. Fuji’s lovely, languid slope.

In her memoir, she travels back to the town where she was born where the closest mountain to her house was not Mt. Fuji but Mitsutōge, a range of smaller mountains facing the magnificent peak. She has a friend drive her through the winding streets searching for the little lane that will carry her to her old house.

At first they cannot find the street. The essay’s narrator describes how she sets her inner compass on the remembered distance from the mountain that she had seen daily as a child. It was her sense of distance from this mountain that allowed her to find her old street, just like a lost child trying to navigate the wilderness. Sometimes we can only see through memories.

I had a similar experience trying to find the street to my old house. After giving up my search the following day, I had lunch with an old family friend, now deep into her 80s. We dined at a small spaghetti place in Nishijin. When we parted ways, she pointed to a small lane I had overlooked before.

“Remember that? It was your mother’s favorite.”

I set off down the lane. My feet naturally found their way to familiar paths. When I came to a bridge, the memories of the past synced with the present.

Remainder of Torikai Wall, 2019. Our house was next door. Author’s photograph.

Or as Yi writes in “Mt. Fuji”:

The scene that arose from memory exactly matched the image of the mountain immediately before me, thirty years thereafter.

“No, we went too far,” I said. “It’s too close, we already passed the road that goes to the right —disconcerted by the thought, I had my friend back up as if in retreat from Mitsutōge.”

The perspectives merged.

And so they did. I found an old address sign that resembled the one I had seen so many times before but had never noticed. And then I saw the numbers that matched those in my memory: 7-34.

The house was long gone. I suspected it would be. So much of Fukuoka now is bright and new and rebuilt. Even so, it gave me comfort to know that I had found it. I had retrieved my memory from beyond the vanishing point.

Author in front of her Torikai house, 1976. Author’s photograph.

For more on Yi Yang-ji’s works, see Michael Toole’s wonderful Master’s Thesis: Towards the Borderlands: An Investigation into the Works of Yi Yang-Ji

Featured photo at top by Alexander Schimmeck on Unsplash

The post Beyond the Vanishing Point: Traveling the Map of Memory appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

July 20, 2022

Tracing a Kimono’s Story: A Transnational Journey

“I have a kimono that my Uncle brought back from Japan at the end of World War II, as a gift to my mother. I’m wondering if you might be interested in it?”

I received an email with this message shortly after my university’s online magazine ran an article on my kimono collection. A member of the Washington University community named Janice had read the article and decided her mother’s kimono would be better served in my collection than in her closet.

“I would love to give it to you, if you’re interested. I used to wear it occasionally, but for the most part, it has been in the closet for many years.”

She followed up this email with a second:

“My sister and my daughters are in agreement. We would like the kimono to have an appreciative home, and we think you would provide it an appreciative home.”

I was intrigued. And, as I’ve noted in an earlier post, I feel kimonos (and other garments that have enwrapped the body) contain glimmers of that person’s energy. I agreed to meet Janice at her house in Webster Groves, Missouri for the handoff.

Over the weeks, as I awaited a mutually convenient time to visit Janice, I wondered about her uncle. When had he been in Japan?

“I just confirmed Nov. 16, 1917 as my uncle’s birthdate. That would make him 24 in Nov. 1941, just before Pearl Harbor. I think he enlisted, rather than being drafted, so he probably entered the Army at 24, when my mom was 12 and came home after the war in late 1945 or sometime in 1946, at age 28 or so, when my mom was 16.”

What must it have been like for his little sister to watch her brother leave for war? He was her only brother. Surely, her heart swelled with pride just as it shrank with fear. She must have thought of him often while he was away. Did she send him letters?

When he returned, Janice told me, Uncle Emery brought back “two kimonos and black silk pajamas from Japan, wooden shoes with carvings in the heels from the Philippines, and two baseballs signed by the team players (we think from teams formed by the soldiers who were in the Army together). He gave them all to my mom.”

Janice had the kimono packed in a bag when I arrived. We exchanged pleasantries. I didn’t want to pull the kimono out then and there—it might seem I was evaluating the piece rather than merely accepting the gift. Janice was being generous, and I didn’t want to detain her. I thanked her. Assured her the kimono would be treasured, placed the bag gently in the back seat of my car and headed home.

Driving the seven short miles back from Webster Groves, I tried to imagine what kind of kimono a twenty-eight-year-old man would bring his sixteen-year-old sister. I expected it to be bright and soft, perhaps something he had picked up at one of the inevitable tourist shops outside the military base.

When I took the bag inside and pulled the kimono out, I was surprised. This was no made-for-tourists kimono. In fact, at one time it had been a formal garment. Black crepe, with crests on the breast, sleeves and shoulder of the “eight-petal-cherry-blossom,” and a design only at the hem, the kimono conformed to the “tomesode” category. It would have been worn by a married woman and only on a formal occasion such as a wedding.

Formal Tomesode Kimono, author’s photograph.

As kimonos go, it was rather sedate, dyed along the hem in subtle colors of pinks and greens. There were the pine boughs, plum blossoms, and bamboo fronds—the triumvirate of festive botanicals—interspersed with the elegant fabric stands and room-divider screens suggestive of the Heian court.

Where had Emery acquired this kimono? Had he purchased it at a secondhand market, as I have done so frequently in Japan? In the immediate aftermath of the war, desperate people would have bartered away their possessions in exchange for food. I wondered if this kimono had belonged to a recently-widowed woman, now no longer in need of family celebrations.

How had Emery’s little sister received the kimono? Had she wondered about the fluttering sleeves? Had she tied the garment tightly around her waist, imagining herself a little Japanese doll? Did she twirl and pose like the woman in Claude Monet’s La Japonaise?

“As far as I know,” Janice would later email me in response to my questions, “my mom would have worn the kimono as a robe over pajamas. I don’t think she wore it outside the home.”

The kimono is discolored now. The inner sleeve is torn. The lining is speckled brown with age. However she wore the kimono, Emery’s little sister had enjoyed it.

Janice’s sister inherited the other kimono. Apparently, she gave it away years ago.

“I wore the silk pajamas as a child, and so did at least one of my daughters, and I passed them on to someone else for a costume. Our daughter is a baseball fan and has the balls. I still have the Filipino shoes.”

I collected the kimono from Janice in June of 2021. Last fall, when the humidity abated, I hung it on a stand in my garden to air it out. Before the night dew fell, I took it back inside and folded it carefully, as my dance teacher had taught me, paying special attention to the collar.

I smoothed out the wrinkles as best I could and placed the kimono inside a soft washi-paper wrapping designed especially for kimono. Next, I stored it away in the Japanese kiri-tansu, or paulownia chest, that I had ordered from an antique shop in San Francisco. Paulownia, like cedar, naturally protects against insects.

From a war-ravaged Japan to a young woman’s chest of costumes in America, the kimono has journeyed from one cultural context to another. Once it marked a married woman’s place in family celebrations. With a shift in time, the kimono transitioned too, carrying with it a brother’s love for a little sister. With each move the meaning of the garment changed as well and it became a playful referent to its original context.

“You have traveled far, little kimono. I do not know your story, but I know you’ve been loved.”

The post Tracing a Kimono’s Story: A Transnational Journey appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

July 6, 2022

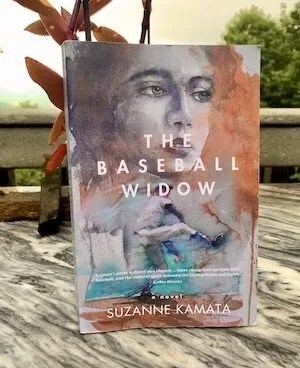

The Baseball Widow: A Book Review

One of the perks of associating with the International Pulpwood Queens and Timber Guys Book Club is that it has put me in touch with so many other writers and their amazing works. Suzanne Kamata’s The Baseball Widow is the Official 2022 Pick of the International Pulpwood Queens and Timber Guys Book Club for the month of July. Because her work is also set in Japan, I was particularly interested to read it.

Suzanne Kamata, an award winning-writer of fiction, poetry, and essays, lives in Tokushima, Japan. She was born and raised in Grand Haven, Michigan, relocated as a teenager to Lexington, South Carolina before making her way to Japan in 1988—ostensibly for one year teaching English on the JET Program. There she met and fell in love with the man who would become her husband and has since lived in Tokushima.

In addition to being an associate professor at Naruto University of Education and a writer, she has raised two children. Her daughter, who was born with cerebral palsy and is hearing impaired, is the subject or at least the inspiration of a number of Kamata’s works—introducing not only the challenges of dealing with disability in Japan but also the way different cultures accept and acknowledge the importance of independence, caretaking, and community.

The Baseball Widow, published in October 2021 with Wyatt-MacKenzie Publishing, is a poignant, at times provocative work. It’s the kind of work that lingers with you long after the last page has been turned. The power of the work comes from Kamata’s ability to deliver compelling and believable characters.

I admit when I first picked up the novel, I didn’t really know what to expect. I knew it dealt with the cultural dissonance between an American woman and her Japanese husband. And of course there would be baseball.

I like baseball. I like explorations of cultural differences. But, would I like a novel about these topics? The answer is absolutely “yes”. The answer is also that this novel is about so much more than these topics, and that’s what makes it so enthralling.

Christine Yamada is the titular “baseball widow.” Once an idealistic young woman intent on doing what she could to make the world a better place, Christine finds her way to Japan where she falls in love and marries Hideki Yamada. A high school baseball star, Hideki is a kind, sensitive man. When he lands his dream job as a high school baseball coach, he is determined to take his team to the tournaments at the Koshien Stadium. In his dedication to his goals, he strands Christine at home with two needy children—one with emotional needs, the other with physical ones—in a culture she does not fully appreciate. And so she becomes “a baseball widow.”

The narrative rotates through the perspectives of four characters: Christine and Hideki are the main players, but there’s also Daisuke, a high school baseball player with experience living in the US; and his mother, Nahoko, who, like Christine, has an absent husband. The multiple perspectives allows readers to dip into the emotions and motivations of each character.

We come to understand their needs, their dreams, and their disappointments. As the story progresses, the characters’ stories intertwine. Unintentionally, they hurt one another. Because of the delicate way Kamata presents the characters, readers are able to sympathize with each one.

There is no “bad guy” here, no one to blame. Hideki devotes too much time to his coaching, leaving poor Christine to fend for herself as she tries to navigate a different (and at times difficult) culture and more importantly protect her children. But we understand why Hideki does what he is does. We recognize the pressures that he also confronts.

58th National High School Baseball Championship. Credit: Rikujojietai Boueisho/Creative Commons

58th National High School Baseball Championship. Credit: Rikujojietai Boueisho/Creative CommonsWe sympathize with Christine, we want to help her. At times we want to shake them both. Even so, Kamata deftly depicts the sweetness at the core of their relationship and the love that now seems to have become remote and unapproachable.

The Baseball Widow is divided into two parts. The first is set mainly in Japan, on the island of Shikoku—considered to be remote and slightly backward—and the latter in South Carolina (could we make parallels on the way both locales are conceived in popular imagination?).

One of the many challenges that Christine faces as a wife and mother in Japan is tending to her children with virtually no support from her husband.

Her son, Kōji, is shy and easily bullied by the children in his school, a fact that will eventually push Christine to travel with him to South Carolina. Her daughter, Emma, has cerebral palsy and is hearing impaired.

One of the brightest points in the novel, for me, was the way Kamata depicts Emma. With all the physical challenges she faces, she is a delightful little girl, eager for adventure, and fearless.

Emma offers a counterpoint to Christine’s obsessive worrying. Perpetually conscious of what others are thinking about her and always afraid of doing something wrong (as a foreigner in Japan), Christine “handicaps” herself and bequeaths her own fretfulness to Kōji, who seems constantly on the verge of a meltdown.

I noticed the Kirkus Review felt the novel was “uneven,” finding high school ball player Daisuke’s storyline less interesting or necessary. I disagree.

What I find so riveting about Kamata’s novel is the way she explores the intersections of different cultures and the difficulties we have communicating across cultural lines. Obviously there are dissonances and disagreements between Americans and Japanese. But, Kamata’s novel also explores the tensions that exist within cultures. Daisuke—himself an outsider to “his own” Japanese culture following his extended time in the United States—falls in love with a Japanese girl who is Burakumin, or a member of a traditionally marginalized and outcaste segment of society. Their fated romance neatly parallels that of Christine and Hideki.

I began this review by describing this novel as one that explores culture clashes and baseball. It’s really much more than that. The Baseball Widow is an engrossing and affecting exploration of the capacity of the human heart to hunger, to hurt, and to hope. Suzanne Kamata is a gifted writer. Her prose is crisp and often elegant. I highly recommend The Baseball Widow.

For more on Suzanne Kamata, here’s a wonderful interview.

And here’s the link to her website where you will find information about her other works: novels, essays, and poems.

The post The Baseball Widow: A Book Review appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.