Rebecca Copeland's Blog, page 11

February 2, 2022

Recipes

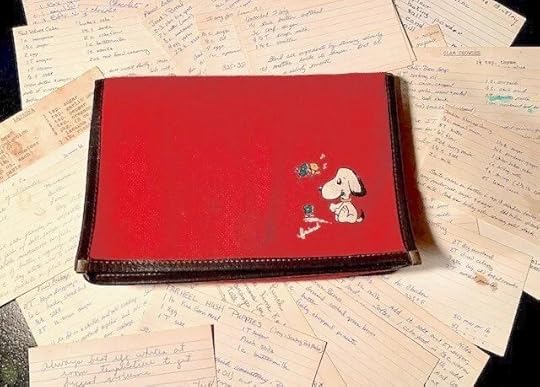

I have an index box of recipes that I almost never consult. It’s not even a box, to be honest, but rather an old red cloth clutch that a little girl in Japan gave me back in 1976. Keeping the recipes in that pouch saved space back in the day when I lived in tiny apartments. I don’t know what happened to the green metal box that originally stored the recipes. I don’t know what happened to the little girl, either. I met her on a train, back when I lived in Fukuoka. She wanted to speak English with me and shyly approached. It was not an uncommon occurrence. Americans were not as plentiful then in Kyushu as they eventually became, and children were excited for the opportunity to practice English. We spoke briefly, and then she gave me her little purse—with an embroidered image of a Snoopy dog at the clasp—because she wanted me to remember her. I do remember her whenever I see that red cloth clutch in my kitchen drawer. I don’t open that drawer very often, though. I don’t really need the things it contains, the instructions that came with the toaster, a beer cozy, old neighborhood newsletters. And recipes.

Red Recipe Pouch

Red Recipe PouchDon’t get me wrong. I cook. But mostly I prepare the same things over and over and do not consult a recipe. When I get tired of the same old dishes (which I rarely do), I ask my friend, Nancy, to give me new ideas.

The recipes in that old red cloth clutch were given to me by women who attended my bridal shower in June 1980. One of my mother’s friends held the shower for me at her house. I remember the women all sitting around the living room with index cards on their laps writing out their favorite recipes. That meant, they knew them all by heart! I have recipes for green bean casserole (which you can also find on the back of the Campbell’s mushroom soup can), easy brownies, cool, crisp slaw, and killer hush puppies. I must have made them all at least once. I can’t remember if my “Yankee” husband appreciated my efforts at Southern comfort food or not. I suspect not. His mother also gave me recipes for things like clam chowder and lasagna. She typed the cards out. The lasagna card is now brown with age and all the oil and sauce I spattered on it as I cooked, desperately measuring. Never getting it quite right.

The women at the party were also asked to write down their favorite tips for housekeeping. I have helpful hints on how to clean the bottom of pans, steps for fighting mildew, and even secrets for a happy marriage. Clearly, the secrets are safe with me.

Over the years I clipped recipes from magazines and stuffed them in the clutch. I have a few my sister sent me, many she inherited from our mother, such as her spicy bean soup. The secret is to start with dried beans. Way too much work for me, though. Besides, the soup is always better when my sister serves it.

Image by Kristine Tumanyan on Unsplash

The post Recipes appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 19, 2022

My Father’s Voice

The other day I heard my father’s voice.

My father died in 2011. Hearing his voice again was an unexpected treat.

Now, before you start envisioning séances and magical meetings, let me explain.

I was searching for my father’s birthplace online. Crazy, I know. But I can never remember where he was born. I mean, it’s not like I was there. And he and his family moved around a bit. All I knew was West Virginia. Since West Virginia’s been much in the news of late, on account of a certain senator from that great state, I wanted to double check my father’s birthplace. I found it, Drennan, an unincorporated community in Nicholas County. It’s kind of smackdab in the middle of the state. In the process of seeking this information, though, I stumbled upon a website with a recording of my father’s voice. The recording dated from April 13, 1962 and he was delivering a chapel talk at the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary where he was then an Assistant Professor of Missions. Curious, I clicked play.

And there he was.

It didn’t sound like him at first. His voice was reedier, more nasal. The longer I listened, though, the more he returned to me. The cadences, the rhythm, the dramatic pauses, that was the voice I used to thrill to hear when I was a little girl.

*****

We glide over the hills. The old station wagon sails, and the late summer colors stream past green and gold. My father is on his way to give the Sunday sermon at the country church where he is the interim pastor. He lets my little brother and me join him. It is always fun. He tells us stories as we drive to Zebulon and then beyond. He makes us laugh. “Why looky the-ah, that fella forgot his yella tractor! It’s yella!” He says the words in what he assumes is imitation of President Kennedy. It’s 1962. “Yella,” my brother repeats, and we explode in gales of laughter. By the time we reach the church, we’re near hysteria. It’s hard to calm down.

My father’s sermon is on acceptance. On making a place for Jesus.

“Foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man has nowhere to lay his head.”

Sitting quietly in the pew alongside some lady I do not know, my mind races out the stained-glass window and into the woods, the kind of woods where my father occasionally takes us for walks. The pine needles are soft and the air clean. Why can’t the Son of Man live there, I wonder. I bet the foxes wouldn’t mind.

Actually, I’ve never really seen a fox hole. It’s probably not very big. But even so, for the Son of Man, I’m sure the foxes would share.

My reveries are brought to a halt. The lady beside me is squeezing my knee. We are all standing for the benediction. My father offers a final prayer and then he strides down the aisle to the front of the church as the members of the congregation remain with heads bowed, singing.

“Blessed be the ties that bind, our hearts in Christian love.”

I peek as my father walks passed. He is tall and his gait is easy and sure.

“The fellowship of kindred minds is like to that above. Aaaaameeen.”

The lady beside me holds me briefly in her arms and exclaims what a wonderful message my father had preached. I wonder if that furry thing around her neck is a fox! It has black beads for eyes and legs that dangle. I squirm furiously to free myself from her embrace. My brother and I rush outside to stand next to our father as he shakes the hands of the church members. Some stop to chat a bit. Some pat my brother on the head.

Greeting parishioners in Connecticut, late 1940s

Greeting parishioners in Connecticut, late 1940sIf the church were far from home my father would stay with one of the members for Sunday dinner. We were sure to have a glorious feast of good home cooking. Fried chicken and mashed potatoes. Often ham. Butter beans and okra. Homemade pickles—cucumber or watermelon rind. Everything would be fresh. Garden picked and farm raised.

The conversation would be polite and cordial until one man would challenge my father on his sermon.

“Brother Copeland,” he would start.

“Why do you reckon the Good Book tells us . . . ?”

And so would begin a discussion of doctrine that couldn’t possibly conclude in anything but a draw. The man who raised the question already had the answer firmly fastened in his mind. Even so, he was no match for Brother Copeland when it came to theological debates. My father was courteous but he wouldn’t back down from his convictions.

I liked watching my father discuss Christian doctrine.

The post My Father’s Voice appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

January 5, 2022

Mountain Treasure

“Come here,” my father said as he stepped off the path. “I have something to show you.”

We ducked under branches and tore through brambles. He was always careful to hold the twigs and branches so that they wouldn’t swish back and slap me in the face.

We crept down the side of the mountain. The sunlight grew dimmer as we pushed deeper into the forest.

“Here.”

My father bent down and brushed the fallen pine needles and twigs back to reveal a stalk.

“Poison ivy?” I asked.

My father tried to teach me about the plants in the woods. He was careful to point out the poison ones. Even so, I always managed to end up brushing against something that left me doctoring my festering skin with pink calamine lotion.

Last week I had proudly showed him a cluster of pointy leaves running along the ground.

“That’s poison ivy, isn’t it?”

“No, that’s Virginia creeper,” he replied. “But it’s easy to mistake,” he continued when he saw the embarrassment on my face.

I was certain he was testing me now on my knowledge of wild plants.

“This is ginseng, Becky.”

I looked closer, trying to appreciate the importance of his announcement.

“I keep it hidden down here. If anyone else finds it, they’ll dig it up.”

My father grew up in West Virginia. He and his family depended on the land to feed and clothe them. For a time, his father worked for a mining company, taking the coal from the earth. Later he would turn to timbering, cutting down and selling the mountain trees for lumber. As a boy my father joined his brothers to hunt. The game they killed fed the family. He also trapped mink and sold the skins. But perhaps one of the tasks he enjoyed most was “senging.”

He and his brothers would roam the Appalachian countryside in search of the prized plant. They would take their catch to the local broker where it would be weighed, the boys paid, and the roots shipped off to Asia to fetch a handsome price. Apparently the market for good ginseng roots was even more lucrative (and less dangerous) than trapping mink.

Now, on his land in Tennessee, he continued his “senging.” He had a good stash, he told me. He was waiting for the plants to grow larger.

When my father died, he took his treasure trove of mountain knowledge with him. I try to remember the stories he told me, the secrets he shared, but so much is lost. I have rambled over the Tennessee property he bought and loved, looking for that hidden cache of ginseng. I’m searching still.

In memory of and who would have been 106 this year!

Photo by Mahdi Bafande on Unsplash

The post Mountain Treasure appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

December 22, 2021

Autumn is for Parting

The trees were brilliant just a few days ago, their branches a shimmer of scarlet and amber. As I set out for my morning run, I notice they have grown more subdued. The scarlet has faded to russet. I hold out my hand and catch an ocher leaf as it plummets towards me.

Autumn is beautiful in the morning light. Even so, the Japanese writer, Sei Shōnagon (c. 966 – 1017 or 1025), elegantly claimed autumn for the evening.

“In autumn, the evenings, when the glittering sun sinks close to the edge of the hills and the crows fly back to their nests in threes and fours and twos; more charming still is a file of wild geese, like specks in the distant sky. When the sun has set, one’s heart is moved by the sound of the wind and the hum of the insects.” —Morris, Ivan, trans., The Pillow Book of Sei Shônagon. London: Penguin Books, 1971.

Autumn presages the end of things.

As I run I think of an autumn ten years ago, when I returned to North Carolina to visit my father. I knew it would be for the last time. He had been dying in slow motion, ever since he took a fall in 2007, and had subsequently made the rounds of one nursing home after another. None would keep him long because he liked to escape, and no institution wanted to run the risk of a lawsuit should he come to harm while on the lam. But, now the end was nigh. His hospice caregivers had been in contact frequently to let us know his slow-motion decline had sped up.

I was ready for the inevitable.

Except, I wasn’t.

I flew from St. Louis to Raleigh on the evening of November 12, 2011, rented a car and went straight to the motel—a fleabag with paper-thin walls. It wasn’t as if I was actually going to sleep. The next morning, I visited my mother in her assisted living apartment and then drove to see my father. I planned to spend most of the day with him. It wasn’t that we would have much to say, he no longer spoke. I just wanted to sit with him. And so I did.

After I left, I drove two hours to see my sister, who lived in the Sand Hills region of North Carolina. The light was slowly fading on the lonely stretch of highway. I sped past soy bean and cotton fields, now empty but for the stover. Beyond the fields were stands of trees, loblolly pines competing with clutches of hardwoods. The oaks still clung to raspy brown leaves, here and there a reluctant sweetgum flickered red. Mistletoe peeked proudly from naked branches. The sky was a quiet swirl of grey and in the distance geese took wing in perfect formation. It was the kind of scene Sei Shōnagon would have admired. Season and time perfectly in sync.

It was the kind of scene that always reminded me of my father, of the walks we took together in the crisp November cool, usually with my brother along as well. The leaves crunched underfoot and the air was sharp with the smell of decay and sometimes smoke, someone somewhere burning leaves. Daddy would point out plants.

“This is sassafras. Smell it?”

He‘d break the twig in two and give us each an end to sniff. We held it to our noses and inhaled.

“Um, smells like chewing gum.”

“Well, I suppose.” My father detested chewing gum!

He‘d name the pines—loblolly, white—and point out the hardwoods. “Locust—they make the best posts. Over there’s an oak.” We learned all about the blighted American chestnut. And Yul Gibbons did not know what he was talking about when he claimed Grapenuts tasted like “wild hickory nuts.”

“There isn‘t any such thing!” my father would say with disgust.

The memories rushed into me as I cruised along. I heard my father’s voice. I knew he was there in the whisper of the pines, the flutter of wings.

Photo by P A on Unsplash

The post Autumn is for Parting appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

December 8, 2021

The Last Time I Saw My Father

My father’s later years were difficult. He bounced from one nursing home to another, his peripatetic life precipitated by his refusal to stay where he was put. By the time my father entered his first nursing home, he was losing his ability to walk. He had nearly lost his ability to hear. But he had not forgotten his wanderlust. He was born in a shanty car, or as he liked to call it, an early mobile home. Travel was in his blood. He left his home in West Virginia at twenty-four, his journeying took him to Africa, India, Japan and points in between. How could we expect him now to stay confined in a tiny room with the bright flicker of fluorescent lights and the constant cacophony of institutionalization? Even though he suffered from Alzheimer’s Disease, he retained a spark of willfulness and ingenuity. He would park his wheelchair by the exit doors and watch the staff come and go. He memorized the door codes. When no one was looking, out he’d go, his strong arms propelling his wheelchair at lighting speed. Once, he was found at a gas station a few blocks away. Another time, when he was being held on the fifth floor of a hospital, he managed to bounce his wheelchair down several flights of stairs before he was apprehended.

Secretly I applauded my father’s rebellion, believing it signaled he was still there. But I knew his escapes burdened my mother unduly. After each escape attempt, the nursing home administrators let her know his roaming ways had disqualified him for further residency. No one wanted to be responsible for an Alzheimer’s patient who had wheels and remembered the joy of flight. Once again Mother would have to go back to the phone in search of a new placement.

The last time I saw my father, we sat in his semi-private room in silence. Or, we would have sat in silence had the television not been on at top volume. I wanted to snap it off but his roommate, also a man of few words, was on his bed and for all I knew, he was enjoying the program, a documentary on the Red Hot Chili Peppers. As “Scar Tissue” blared from the tinny TV speaker, I told my father how much I loved him. I told him he had been a good father, he had given me more than I could ever articulate.

I struggled not to cry. I had to say what I’d come to say. My throat burned, and the effort to refuse my tears twisted my mouth into a grotesque scowl. My father stared at my face intently, his once sky-blue eyes a filmy grey.

Scar tissue that I wish you saw

Sarcastic mister know-it-all

Close your eyes and I’ll kiss you, ’cause

With the birds I’ll share

With the birds I’ll share this lonely viewin’

With the birds I’ll share this lonely viewin’

With my father on Mt. Kirishima, 1976

With my father on Mt. Kirishima, 1976He reached out to me. I took his hand in mine, touched by his gesture.

No. That was not what he wanted.

He pointed at my face. Was my grimace upsetting him? No. He pulled my glasses off.

“Daddy, no, you can’t take my glasses.”

His grip was ironclad. It took me some cajoling to get my glasses back.

“Please, please,” he mumbled, but I’m sure that’s what he said.

With the birds I’ll share this lonely viewin’

With the birds I’ll share this lonely viewin’

With the birds I’ll share this lonely view

I noticed that he wasn’t wearing his glasses. I pulled out the drawers in his nightstand and poked around. His drawers were mostly empty. I couldn’t find his glasses. I remember Mother telling me that his things always went missing. She finally gave up on replacing his hearing aids. I imagined his glasses too had disappeared.

“I’m sorry, Daddy.”

By the time I turned back to him, he had forgotten about the glasses. He had slipped into himself.

I wave goodbye to ma and pa

‘Cause with the birds I’ll share

With the birds I’ll share this lonely viewin’

With the birds I’ll share this lonely viewin’

I pushed his wheelchair out into the hallway. The aides had told me not to leave him in his room alone when I left. They would come for him when it was his turn in the dining room.

I didn’t want to leave.

I still had to stop in to see my mother before I drove two hours to my sister’s house, and it was getting late. This would be goodbye. I would never see my father again.

I kissed his cheek. I smiled at him through my tears, and then I headed down the long corridor. The heels of my cowboy boots clicked over the shiny linoleum.

That’s right, I’m my father’s daughter. I’m that third-grader in her kick-em-up cowboy boots who refused to let the schoolyard bully intimidate her. I’m that bleeding heart who joined my father hunting only to cry when I learned he killed a rabbit. I’m that girl who only ever wanted to make my father proud.

I turned to look at him one last time. He brought his hand to the brim of his baseball cap as I blew him a kiss, no longer able to hide the stream of tears.

Goodbye November 2011

Goodbye November 2011Scar Tissue

Writer/s: Michael Peter Balzary, John Anthony Frusciante, Anthony Kiedis, Chad Gaylord Smith Publisher: MoeBeToBlame, WORDS & MUSIC A DIV OF BIG DEAL MUSIC LLCLyrics licensed and provided by LyricFind.com

Photo by Mantas Hesthaven on Unsplash

The post The Last Time I Saw My Father appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

November 24, 2021

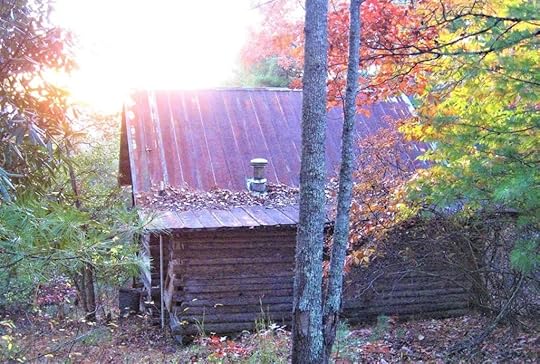

Closing the Cabin

October 28—Sunday

I’ve drained the pipes—mostly—and packed the car—mostly. All I have left are the personal things I’ll need for the evening, food, my laptop, and a few odds and ends. I decided to put Wilson’s bed in the car already. I’m glad I did because it’s raining now and it would be hard to carry it down to the car in the morning—fully loaded with all the other stuff—especially if it’s raining. Wet dog is bad enough. But driving eleven hours back to St. Louis with wet dog bed would be even worse!

The light outside is fading fast now. The rain sounds heavy, but it’s hard to tell. The way it hits the tin roof always makes it sound harder than it is.

I have a fire going in the wood stove. The cabin is nice and cozy. I’d stay longer if I could. It’s fun to be here when it’s cold outside. The wood stove really heats this cabin. But snow is in the forecast and I cannot afford to be stranded here. I have to get home in time to vote on election day, November 6, 2012!

Tonight, I’ll have a quiet evening, enjoy the rain on the roof, NPR tuned in, a little red wine (maybe more than a little, depending on whether I want to carry the bottle with me or not! I hate to waste), a warm cabin, and a happy dog asleep beside the woodstove.

I like it here.

I have liked it very much.

The programming on the radio turns from politics to the Latin Hour. Salsa anyone??? How wonderful for my last cabin night to be festive!

Wilson continues to dream by the woodstove, undisturbed by my frolicking.

Morning comes early. In fact, I’ve set the alarm for 5:00 am. I always like to get out before the sun when I have a long drive ahead of me. The rain has stopped, fortunately. I have already turned off the water, so I wash my face and brush my teeth with water from a jug. I heat the coffee, but I’m too keyed up to eat anything. I’ll snack in the car.

Wilson has a pack to wear. I fill it with the rest of his food, his bowls, and the last of the trash. Despite my planning and packing the day before, I still have two armloads of things to carry plus my own back pack.

I do one last check of the cabin with the light from my headlamp. As I pull the heavy wooden doors closed along the porch, I notice that it has begun to snow.

Snow

SnowI lock the door to the cabin, pick up my bags, and head out into the dark, the snow flurries flashing in the beam from my headlamp. I walk halfway down the hill and turn back to look for Wilson. All behind me is dark. I retrace my steps until my lamp catches the blue glow of animal eyes.

“Wilson, come!”

The eyes do not move.

I feel a flash of fear along my back, maybe that isn’t Wilson. I creep back up the steep incline. He has never done this before.

I call him again, still no response. I know that he does not see well. Perhaps he needs to be closer to my headlamp. When I draw next to him, I see to my relief that the eyes DID belong to Wilson. Of course they did! He turns and dashes back to the cabin door.

I set my bags down and coach him forward, tugging at his collar. I curse myself for putting his leash in the car. He sits when I let go of his collar and won’t budge. I have to pull him. But I can’t pull him and carry my bags at the same time. The only way down is to set one bag down, pull Wilson, leave him, go back to my bag, bring it down to Wilson, set the bag down, pull Wilson, and so on and so on until we get closer to the car.

The whole time I am wondering what has gotten into him? His fear makes me fear. Maybe he can’t SEE anything, but does he SMELL something? Is there a predator out there beyond the darkness? If so, what might it be? Has Earl’s bear materialized?

As soon as Wilson sees the car he bolts towards it. I can’t keep up with him, as I need to go back a few feet to retrieve my bag. Once he reaches the car he begins to jump at the passenger door, clawing to get inside. He is terrified. And now, so am I. But, I don’t want him to eviscerate my car, so I drop both bags and run to open the door. Once he’s safely inside, I go back for the bags, load them in the car as well, and dive into the front seat, all the while looking wildly into the darkness around me.

I start the car, half expecting to see a giant monster loom up in the headlights. All I see is dancing snow.

Top photo by alexander ehrenhöfer on Unsplash

The post Closing the Cabin appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

November 10, 2021

It’s Time to Go

I’ve come to end of my writer’s retreat. It has been a fabulous retreat. A treat of a retreat.

When I arrived on October 1, Monday, the trees were in leaf and vines and grass sprung thickly from the paths, grabbing at my ankles as I pushed my way through. During the day, the sun warmed the cabin to a summer heat and the metal roof pinged and complained. Temperatures soared into the 80s by day and dipped to the 40s in the evening.

On warm evening nights I sat on the back porch with a chilled beer and watched the sky turn from blue to pink to mauve.

End of the day

End of the dayJets passed far overhead, as if belonging to another world. They winked silver in the fading sun, leaving a streak of white cloud like a snail’s trail. The white turned pink and then evaporated. Once the sky grew dark I went back inside to start dinner.

As the days went by I watched the leaves turn from green to the brilliant hues of autumn, red, gold, ocher. I could hear them fall crisply to the forest floor. Sometimes crashing so loudly I believed an animal was afoot. Perhaps a bear, that damn imaginary bear.

I have used the time here to dream, to step into a world of imagination, to cross over borders of time and space. My mountain ridge in Eastern Tennessee merged into the Eastern Hills (Higashiyama) of Kyoto. And I became Ruth, inheriting her story, absorbing her pain and fear.

Mornings came and went and evenings followed. Gradually my fear of the bear evaporated. Before long I was rambling along the wooded lanes and laughing at the stumps and clumps that had appeared so threatening in the morning mists just weeks ago. Ruth, too, began to find her strength as she chased after those who would hurt her, had hurt her.

The weather is changing. Hurricane Sandy is lashing the coast. It will send its clouds as far west as the cabin, I suspect. The crisp blue October skies are now muted with grey November clouds. Rain is not far behind. And then, perhaps, snow.

It is time to go.

I still worry about my mystery novel.

It’s been easier to imagine a novel focused on Earl—a man who once antagonized me but who now I have come to rather enjoy—than it has been to smooth the wrinkles out in my “kimono” mystery. I keep trying to unravel the story. I have bodies to account for. But no one yet to blame. Who is the murderer? The question has hounded me even as I write. And then this morning, as I was running along the northern ridge of the property, it came to me. I met the killer. I know now how the story will end.

And so, it’s time to go.

I need to get out ahead of the storm.

Top photo by Artem Sapegin on Unsplash

The post It’s Time to Go appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

October 27, 2021

A Storm is Brewing (and so is a story)

October 15, 2012

A storm is brewing (and so is a story). The sky has grown a milky grey and the wind is quickly denuding the trees, sending leaves swirling over the tin roof, scratching its surface as they crash to the ground below. It feels like November already. My cabin puffs smoke like a dragon.

I’m midway through my writer’s retreat now. My murder mystery is slowing revealing itself to me.

I’ve been dipping here and there into The Elements of Mystery Fiction by William Tapply. The author tells us:

“Your sleuth should obviously be drawn with the greatest care. You want your readers to identify with her, root for her, agonize with her.

Readers will worry about her because she has goals that are important to her and it’s not certain that she’ll achieve them.

Define your story by your sleuth’s motivation. What does she want? Why does she care enough to take significant risks to attain it?”

What does Ruth care about? She tells herself she doesn’t care about anything. But it’s a bluff. She cares about art. She cares about Shōtarō Tani and wonders why he stopped writing. Isn’t he a bit like her? Just throwing in the towel and fleeing? For him to return to the literary arena offers her a ray of hope, doesn’t it? Perhaps return is possible.

When she begins to suspect him of foul play she tries to reason her suspicions away. He loved his sister. His earlier novel, The Prodigal Son Does Not Return uncovered the depth of respect he had for her and the pity he felt for her circumstances. Ruth cannot believe Shōtarō would harm his sister. Clearly, the culprit is her thuggish husband.

Ruth is also moved to protect Daté—whom she fears is in harm’s way. Daté’s novel, Kimono Killer, was only thinly disguised. It was easily recognized as a critique of the Tani family. Daté received threats, which she laughed aside. Soon she moved onto her next novel. Ruth admires Daté. She wants to warn her that she is in danger. Will she be too late?

Clearly it is dangerous to remain associated with Shōtarō and his “novel.” Ah, the perils of translation! For me, the danger of translation has always been the production of work that is unrecognized and unrewarded. For Ruth the stakes are much higher!

Cabin, October 15, 2012

Cabin, October 15, 2012I turn back to the window. The sun has broken through the milky clouds and for a moment turns the broad-leafed tree outside the cabin a glittering gold. The wind stops. Even the milky clouds have arrested their flight across the sky. All is silent and still. A wisp of smoke drifts lazily across the window.

Top photo by Brian Yurasits on Unsplash

The post A Storm is Brewing (and so is a story) appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

October 13, 2021

Dogs, Not Bears

From the moment I awoke the sun was working its way out, tinting the sky outside my window a wispy lavender. Wilson saw that I was awake and came over to give me a lick on the lips.

I tolerated it.

Since he is normally so undemonstrative, I don’t mind an occasional lip lick or two.

I planned to go to McDonalds this morning. Not for the coffee and certainly not for the burgers! I go for the free Wi-Fi my connection to the world beyond my writers retreat. I packed my PC in my knapsack, bade Wilson goodbye, and headed down the mountain to my car.

Just as I came to the bend, three dogs charged up the slope toward me, barking. To be honest, I find loose dogs at times much more dangerous than bears. The back of my neck flashed with fear and my shoulders tensed as I looked around for a stick or a rock in case I’d need it.

They did not seem feral. But they were aggressive.

“You can’t be barking at me!” I spoke harshly, trying to deter an attack.

And then I heard a woman’s voice down below calling the dogs. They backed away. I waited for the woman to approach. She was young with dark hair and a healthy gait.

Ah, she must be the neighbor who walks my land with her dogs. Earl had mentioned her. He spoke about her and her activities as if I should find her objectionable.

She and I shook hands and spoke briefly. I asked if she walked the land often. I told her I worried that I might run into her dogs with mine. I don’t know that she understood. Wilson is aggressive with dogs. I didn’t want a fight.

I don’t think she realized I was the property owner and she was on my property without permission. But she was sweet, and judging by her manner of speech, she didn’t seem local.

I asked her about the bear.

“Well, yes, there was a bear last year,” she said. “It started going through garbage cans because people weren’t careful.”

Was it big, I wondered?

“It was a small, bear,” she told me, a little put off by the way Earl had characterized the creature.

She did not seem pleased. Other than that bear, she told me she had not seen any others, and she walks here several times a week.

“They killed it.”

She also told me that Earl has a buddy who hunted here last season and trashed the road with junk. She told me she picked up whatever she found and complained to Earl.

I like her.

She can walk here whenever she wants.

There is no bear!

At least not one that will show itself to anyone but Earl.

I’ve decided when I write my Earl murder mystery, she will have a starring role.

The post Dogs, Not Bears appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.

September 29, 2021

Hemlock Haven

Hemlock Haven was my mother’s place. She discovered a quiet grove of hemlocks on the southern point of the Tennessee property. The hemlock branches were low and stately and ferns grew in the bed of needles beneath them. My father built my mother a little bench under the tallest hemlock—its lowest branches high enough to admit a woman even as tall as she. It was her place.

She would go there to sit and “meditate.”

Surely it was difficult for her up here in the wild woods while my father was off felling trees and chopping wood. In the beginning they had to haul water. Mother was in charge of providing meals and cleaning up—without the benefit of vacuums or other electric devices.

A few months ago—when Beth and I visited her in Raleigh for her 89th birthday—she told us she hated coming here.

“HATED IT.”

She didn’t mince words.

“It was a vacation for your father,” she continued. “But for me it was never-ending work. As soon as the breakfast dishes were done, I had to begin preparing lunch. And you couldn’t keep the place clean, what with your father coming and going in his dirty boots. But he loved it. So I came along.”

When she could find a minute to spare, she visited her Hemlock Haven. Her refuge. She could sit there quietly without worrying over cleaning rags and iron skillets.

It’s gone now.

I don’t know quite what happened. A few hemlocks still remain, but more than a few are denuded, their stately branches now skeletal. Once known as the redwoods of the East, the great trees now stand against the vibrancy of the other pines like grey ghosts. And where the ferns once grew in lush profusion I find piles of branches and upturned trees.

My mother told me the trees were damaged by a massive storm that rolled over the mountains a few years ago, uprooting everything with powerful downbursts. But later I learned a new predator, the hemlock woolly adelgid (an Asian aphid-like insect), began to make its deadly passage through the mountains of eastern Tennessee in the early 2000s, born by storm winds and migratory birds.

The wanton destruction at my feet makes we think of the capricious nature of death—particularly of murder.

I need a victim for my novel, The Kimono Tattoo. For the last few days, I’ve been introducing myself to my characters. I’ve been writing back stories.

But soon, I will need to tell the story of a murder. William G. Tapply in The Elements of Mystery Fiction: Writing the Modern Whodunit states: “Before you write this story of detection, you must first write the story of the murder itself.” Emphasis his. He’s pretty clear on this point.

No murder, no murder mystery.

Apparently, the murder mystery author needs to have substantial knowledge of the victim and the murderer. Both must have a back story—and both must interact with a number of random characters themselves with interesting stories. So far, I’ve met Ruth, her friend Maho, with the mohawk, and their boss, Mrs. Shibasaki, the president of the translation company where they both work. Of course, there’s the author Shōtarō Tani and his sister, the elegant and capable Satoko Tani. And then there’s Miyo Tokuda who sets the wheels in motion by asking Ruth to translate Tani’s novel.

Someone’s gotta die.

Gazing out over the grey ghosts of the Eastern Redwoods, I think I know who it will be.

Featured photo by Brice Cooper on Unsplash

The post Hemlock Haven appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.