“New and Substantial Evidence”: Surviving a Negative Tenure Decision

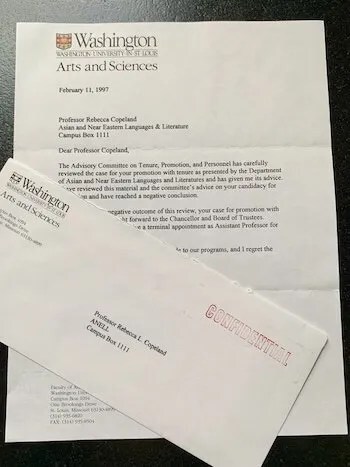

“I don’t understand,” I said, as I read the letter a second time.

It was short, barely two paragraphs.

“We don’t understand, either,” Peter, the chair of my department, said as he turned to close the door to my office.

The room was small and with all my books, dictionaries, desk, filing cabinets, and computer stand, there was hardly space for an extra chair. The one I had—for students—was covered with my coat and scarf.

It was the middle of February, and in typical St. Louis fashion, cold and grey.

Peter stood, his hand on the doorknob.

“But it doesn’t make sense.” I scanned the letter one more time. Had I read it wrong?

The letter was from the dean.

I have reviewed this material and the committee’s advice on your candidacy for promotion and have reached a negative conclusion.

“Wait. So, I didn’t get tenure?”

“No.”

Did he mean, “no, that’s not right, you got tenure.” Or, “no, you didn’t get tenure.”

Did he mean, “no, that’s not right, you got tenure.” Or, “no, you didn’t get tenure.”

My head was swimming. I could see the words on the letter, but I couldn’t really put them in order.

It was as if my ability to read English had suddenly evaporated.

“You said I had a good case,” I mumbled mystified.

“You did have a good case. I mean, you do,” Peter groped for the right words. “We don’t know what happened.”

“And what about the others?”

Two other assistant professors in the department had gone up for tenure at the same time as me.

“They got it.”

“They got it,” I echoed. “That’s good.”

“I know this is hard to process,” Peter said, returning to chairspeak. “I’ll leave now, but we can discuss it later. I’m talking with the other senior members of the department to see what options we have going forward.”

I don’t remember what I did after he left.

I don’t think I cried.

I imagine I sat in my office for a bit trying to figure out my exit strategy. I mean, my exit from my office to my car. I wanted to go home. I wanted to hide.

I didn’t want anyone to see me.

What would they think? Would they know?

In the weeks to come, it was difficult to muster the energy to continue teaching. I didn’t want to interact with anyone. I imagined myself a walking wound.

I had no choice, though, and so off I went every other morning or so, to my office, to classes, to rooms with other faculty.

I felt as if I had “loser” branded on my forehead.

Some people averted their eyes when they saw me in the hallway. Or so I thought.

I remember Van told me how he had struggled with the news of his own negative tenure case.

“I puttered in my backyard for an entire year, like Yasuoka Shōtarō’s father.”

The department had supported my promotion enthusiastically, and I’d been told my external letters were uniformly strong.

One senior colleague had also experienced a negative decision and had fought back. He gave me a plan of action.

“I would make an appointment with the dean,” he told me, “not to argue but to seek information.”

What was the rationale for the decision; and what was the vote?

Following his advice, I learned that the tenure and promotion committee had found my scholarship lacking.

I only had one book.

And that book was on a woman writer they’d never heard of. Moreover, many of my publications were made up of translations. At the time, translations were not evaluated highly—irrespective of the significant amount of research many of the translations required.

Of course, a dossier of one book and an assortment of articles was typical of successful promotion cases in my discipline.

For some reason, though, the committee believed that I was hired on the basis of the book I had in preparation when I started working at the university—The Sound of the Wind: The Life and Works of Uno Chiyo. That meant that I was expected to produce a second book, whereas my peers were not.

This reason may have made sense if I’d been hired as an advanced assistant professor, but I was not. I was given an entry-level salary when I joined the faculty, and my five years teaching at International Christian University were not taken into account.

The vote, I was to learn, was four in favor of tenure and three against. The dean made the ultimate decision.

From my discussion with the dean, I understood that I could ask to be considered for promotion the following year, if I could provide “new and substantial evidence” of additional research.

As luck would have it, I was shortly to learn that I had received a Japan Foundation Research Grant, which would allow me to spend time in Tokyo doing the archival work I needed to do to complete my work in progress. Lost Leaves: Women Writers of Meiji Japan, was already under contract with the University of Hawai’i Press, which had published my earlier monograph.

Shored up by emails, letters, and phone calls from friends and former students around the world, I forced myself to attend the tenure party the department threw for my two colleagues. I wanted to celebrate them! I just worried that my presence would be a wet blanket.

The last thing I wanted, though, was for people to look at me with pity. I wasn’t pathetic. I had been misjudged, and I was standing up for myself.

I wasn’t a walking wound.

After a few “there, theres,” and whispered regrets, most people just let me go about my business.

I spent the summer and fall in Tokyo, affiliated with Kokugakuin University, digging deep into the archives, and writing, writing, writing.

By the end of the fall, I had a complete manuscript.

I also had another contract from Hawai’i for the edited volume that would become known as The Father-Daughter Plot. Eventually, I would ask Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen to join me as co-editor.

“New and substantial evidence”? I thought I had it in spades.

On January 12, 1998 I received another letter from the dean, this one even shorter.

I am pleased to report that acting on the recommendation of your department and with the advice of the Advisory Committee on Tenure, Promotion, and Personnel, I have decided to forward to the Chancellor my recommendation that you be promoted to the rank of Associate Professor with tenure effective July 1, 1998.

Later I would learn that even with the amount of new material I had provided, two members of the promotion committee STILL decided to vote against my tenure. This time, however, the dean made the decision to put my case forward anyway.

My meeting with him, perhaps, had made the difference.

He and I would go ahead to have a good working relationship. I became the Director of the East Asian Studies Program. I wrote a grant that brought the university $1.3 million for East Asian programming, and once I was promoted to Full Professor, I took on the role of Associate Dean of University College and Director of the Summer School. Following that, I was chair of the department for two terms.

Eventually, I would spend three years on the Tenure and Promotions Committee myself.

I share the above account here—not to complain (though I may have complained just a little); not to humble brag (though I AM proud of my fortitude); and not to suggest that my scholarship in anyway deserved the disregard it received from the tenure committee (who, after all, were from entirely different disciplines with absolutely no understanding of Japan).

What I hope readers will take away from this account is that others don’t define us. Our career does not define us. If for some arbitrary reason, we don’t make the cut by whatever evaluation system we are measured, it’s not a true indicator of our worth.

Know who you are. Be true to yourself.

Postscript: The photo opening this post is by David Kilper, then a staff photographer at the university. The photo originally appeared in this article about me, written by Gerry Everding in 2003, twelve years after I joined the faculty at Washington University in St. Louis.

The post “New and Substantial Evidence”: Surviving a Negative Tenure Decision appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.