Flurry of Letters: Translation is more than Words

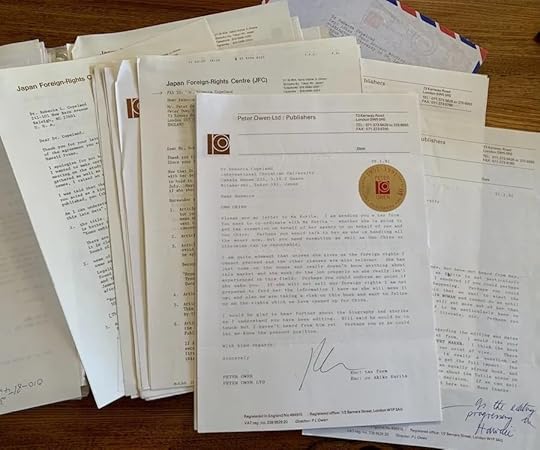

A flurry of letters followed the November 1990 meeting with Akiko Kurita, Fujie Atsuko, Peter Owen, and me. All were focused on reaching an agreement so that I could begin translating The Story of a Single Woman. Peter wanted all the rights to translations into other languages. Ms. Kurita claimed to have already sold the rights to another translator in France, and later Peter and I learned the same had happened with the rights to German, which made Peter very cross.

What did it even mean? I wasn’t sure.

And the back-and-forth was not limited to the contract I was then negotiating with Peter. Apparently, the contract I had earlier acquired with the University of Hawai’i Press was also on the table.

Not understanding why that would be, I followed up with Ms. Kurita.

November 29, 1990

Ms. Akiko Kurita

Managing Director

Japan Foreign-Rights Center

27-18-804, Naka Ochiai 2-chome

Shinjuku, Tokyo 161

Dear Ms. Kurita:

It was a pleasure to meet you the other day in Uno-Sensei’s apartment. As per our subsequent discussion on the phone, I agreed to send you a copy of my contract with the University of Hawaii Press. However, now I am wondering what the rationale for this is. (In my excitement, I apparently forgot to ask you! Or, perhaps you explained but I failed to understand. That occasionally happens, too, I’m afraid.) Since the book I am writing for the University of Hawaii Press has absolutely no connection, that I can see, with the book Mr. Peter Owen is proposing, I’m still unclear as to why my contract with them is important to our discussion.

As the letter continued, I launched into a defense of Peter and his motives. I could tell from our earlier meeting that Ms. Kurita found him distasteful. I worried that his brazenness would sour our chances of securing the contract to translate The Story of a Single Woman.

Mr. Owen is a shrewd publisher. He knows his audience very well. But more than that, he is also dedicated to presenting to English audiences the best writers of other lands, and most of the works that he publishes are translations. As Endo Shusaku has stated: “Peter Owen is an excellent discoverer of the hidden novels around the world and he encourages them to grow.”

I would like to be part of that process. And, I would like to proceed with this book (Aru hitori no onna no hanashi)…

Kurita responded (December 4, 1990). First she explained why she needed to have a copy of my contract for the Hawai’i book, which would include translations of three of Uno’s stories. I had met Uno earlier and had secured her permission. At the time, I had thought that was proper and sufficient. Ms. Kurita let me know it was not.

Dr. Rebecca L. Copeland

INTERNATIONAL CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY

Mitaka, Tokyo

Dear Dr. Copeland,

Mrs. Fujie asked us to handle all foreign rights negotiations on the works by Uno-sensei retroactively, as she has no records at her hand. Uno-sensei and herself always said ‘yes’, ‘yes’ to everybody who asked to publish or translate. She recalls she received one copy in English, but not any income from these deals. (In fact, I think she does not remember what have been done in the past, as she expressed herself ‘ōzappa’.)

What Ms. Kurita said made sense. I could just picture Uno Chiyo smiling and agreeing to translations requests right and left without creating any kind of structured agreement. Being easy going (‘ōzappa’) was ever her style.

In response to my accolades about Peter, Ms. Kurita continued:

I agree to your and Mr. Endo’s comments to Mr. Owen in some extent, but I have had bitter experiences with him too. I appreciate his enthusiasm and also your evaluation. And I have no objection of exchanging the contract between the author and Mr. Owen, respecting his desire. But, unless I know the present situation of the works of Uno-sensei, it seems difficult to draw up the contract.

[Written in hand] P.S. Here is a copy from “Practical Guide to Publishing in Japan,” just fyi.

I sent Ms. Kurita my contract.

Peter and Ms. Kurita continued to tangle over the rights for The Story of a Single Woman. Everything he sent to her, he sent to me as well via either a carbon copy, a facsimile, or a newfangled machine copy.

The amount of paper I began to accumulate ballooned with each passing month, and so did Peter’s frustration over the negotiations.

On January 21, 1991 he writes:

I chased Kurita about ten days ago, but have not heard from her, she is waiting for Chiyo, but as Kurita is not particularly efficient or unduly intelligent, I wondered if you could perhaps telephone her to see what is happening.

Finding her somewhat later, he writes directly to her on January 30, 1991:

“Thank you for your letter regarding CHIYO. The agreement is not right and it is not in parts as agreed between us.”

It was on the issue of foreign translations that they tussled.

Peter amended clause 16 in the contract: FOREIGN TRANSLATIONS: “Peter Owen shall handle the foreign and translations rights on behalf of the author and pay to the author’s agent 75% of the net proceeds received by them.”

To me, he wrote on February 25, 1991

“Could you please telephone her to chase her up. I am eager to proceed and if you would like to do it let’s give her a shove. She doesn’t really know what she is doing. I find these Japanese awfully difficult to deal with.”

Clearly, Peter overestimated my telephone negotiating skills.

At this point, I had issues of my own to deal with. My marriage was careening into divorce, and I had just returned from a job-hunting trip to the United States. As a result, I had secured a tenure-track position at Washington University in St. Louis, to start in August, and was now trying to prepare for that.

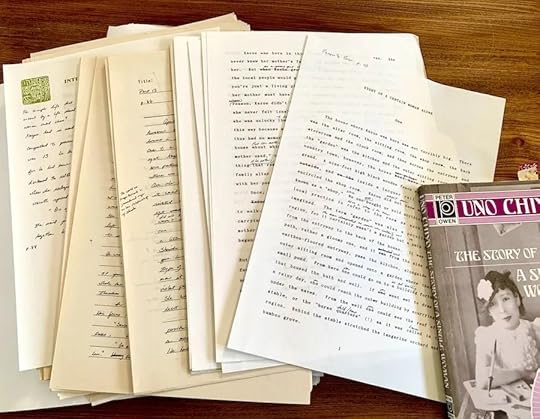

To relieve my anxieties, I translated.

I had just learned how to use a word processor, and I started typing my translations up that way. Of course, I did not have a personal computer at home. I wrote my translations in long hand on scrap paper, sitting at my dining room table, and then carried the drafts to campus later in the week to transcribe onto the word processor. We used WordStar.

The translation slowly coalesced from the Japanese book, through my hand, to lined paper. The trek to my campus office continued the process as I pictured in my mind the words on the page. Once seated before the computer, the words jumped from scribbled handwriting to a screen with a blinking cursor.

When I wanted to check sections of the translation, I consulted a neighbor, Mrs. Higashi, whose husband taught physics on campus.

I called her my “Iki-jibiki,” my “Living Dictionary.” We’d sit and have tea in her cozy living room and talk about phrases I didn’t understand.

And then, another letter would arrive from either Peter or Ms. Kurita.In a letter dated February 25, 1990 Ms. Kurita responded to Peter’s revised contract, quibbling with some of his changes, including this:

7. Your article 16. Unfortunately, your request is not realistic. As I may have told you when you were in Tokyo, the situation has been changing. It may be that when you had exchanged the contract with Mr. Shusaku Endo, there were not many translators from Japanese to other languages. However, recently, potential translators from Japanese into any other languages have been increasing drastically.

They sometimes translate before having the permission from the author and present the translated ms to the publisher directly. Then, the publisher proposes to the proprietor. Actually, this was happened to this title. We sold the German rights already. (I also explained this to Dr. Copeland.)

We have no way to stop translators from translating the works they like. These matters happen recently quite often not only for Chiyo Uno’s titles but also for other author’s titles. We will certainly inform you if and when the foreign language rights are sold before you publish the English edition.

On March 4, 1991 Peter rebutted Ms. Kurita’s characterization of Article 16:

We want translation rights […]. As far as I can see you are generally not in a position to sell these rights as we are, as we are in constant and close touch with foreign publishers and the publishers to whom we sold CONFESSIONS OF LOVE have been given an option on any of Chiyo books we publish. This seems to be the easiest solution to exclude Germany and give us the right to handle the other rights as per my contract. Please believe that on this kind of book we are taking a risk as the market here is quite appalling and has degenerated again for fiction. I suggest you now draw up a final contract on this basis but including the translation rights except Germany, which you say are sold.

There is no point in your holding on to the rights if you are not in a position to sell them, and I do know that Japanese publishers and agents don’t sell rights and find it very difficult to sell rights from Tokyo, and we do have our publishers lined up for this author.

[…]

Please let us settle this matter quickly to avoid a lot more correspondence and also so that Dr Copeland can proceed with the book otherwise it will never appear.

Ms. Kurita replied in her ever tactful way on March 15, 1991.

May I draw your attention to the fact that we were organized by the investment of various publishers to sell the foreign rights of Japanese publications? You may remember that I lived in Cologne for three years and 1.5 years in London. Thus, I tried to make good relationships with the editors who are interested in Japanese works. I visited many publishers in various cities and regularly attend the book fairs. But, knowing your enthusiasm, I said ‘I will not promote this title’ in other countries. I just worried if you misunderstood [. . .]. I respect your understanding. Thank you.

Remarkably, by mid-March, Peter Owen and Akiko Kurita came to an agreement.

On June 15, 1991, Ms. Kurita wrote to me:

“Finally, we received the signed contract in triplicate, which we are enclosing here… We are anxious to see the English edition of Uno-sensei’s book.”

With a contract safely in hand, I worked feverishly over the next month to finish the translation, wanting to have it completed before starting my new position at Washington University in St. Louis.

My five years working at International Christian University came to an end. A new chapter was to begin.

In the posts ahead, let me share more about my discussions with Peter about what to translate. Later, I will focus on the way translation fit an academic career.

The post Flurry of Letters: Translation is more than Words appeared first on Rebecca Copeland.